Sep 12, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

Lynn K. Hall

Increasingly, mental health professionals are providing counseling services to military families. Military parents often struggle with child-rearing issues and experience difficulty meeting the fundamental needs for trust and safety among their children because they are consumed with stress and their own needs. Within this article, military family dynamics are discussed and parenting styles, namely coercive, pampering or permissive and respectful leadership, are explored. The authors conclude by highlighting counseling interventions that

may be effective for working with military parents and families.

Keywords: military parents, family dynamics, child-rearing, safety, counseling interventions

In 1994, Donaldson-Pressman and Pressman began tracking families in their practice who had many of the dynamics of alcoholic or abusive families, but had no history of alcohol abuse, incest, physical abuse, emotional neglect or physical absence. The one consistent characteristic of those families was similar to many military families that I worked with, which was that “the needs of the parent system took precedence over the needs of the children” (Donaldson-Pressman & Pressman, 1994, p. 4). It is because of this dynamic that I chose to use the term “parent-focused families” when writing about parenting issues in the book, Counseling Military Families: What Mental Health Professionals Need to Know (Hall, 2008). Developmentally, many military parents who are struggling with child-rearing issues have difficulty meeting the fundamental needs for trust and safety for their children because they are consumed with their own needs (Hall, 2008). One of the major challenges of military families is learning how to operate within the larger external system of the military without complaint or unreasonable expectations.

Wertsch (1991) described this dynamic as the stoicism of the military, or the need to be ready, maintain the face of a healthy family, and do what is expected without showing discontent or dissatisfaction. A second important dynamic is secrecy, or not allowing what happens in the family to impact the military parent’s career. The third dynamic, denial, also is present in most military families as they make numerous transitions and experience issues like the deployment of the service member (Wertsch, 1991). In order to survive, the non-military parent and children often deny the emotional aspect of these transitions, as well as more “normal” developmental transitions. In many parent-focused military families, particularly when there is a child who is acting out or in other ways exhibiting behavior problems, these three dynamics often lead to other characteristics (Hall, 2008) such as:

1. The belief that the child is the problem, rather than the child may have a problem.

2. The child is given a label, such as lazy or stupid, rather than understanding that the behavior may be the result of a mental health, developmental or learning problem.

3. Children sometimes learn early that, if expressed, their feelings may make things worse so that detaching emotionally becomes quite functional.

4. Once they discover that their feelings will not be validated, they may learn to distrust their own judgments and feelings.

5. The child may take on the responsibility of meeting the emotional and sometimes physical needs of the parents.

6. If either parent is inconsistently emotionally available, children may have difficulty letting down the barriers required for intimacy later in life (Hall, 2008; Donaldson-Pressman & Pressman, 1994).

These characteristics, when played out in military families, are a reflection of the secrecy, stoicism and denial often demanded of these families. Instead of providing a supportive, nurturing, and reality-based mirror, the parents may present a mirror that only reflects their needs, resulting in children who grow up feeling defective (Hall, 2008). “When one is raised unable to trust in the stability, safety, and equity of one’s world, one is raised to distrust one’s own feelings, perceptions, and worth” (Donaldson-Pressman & Pressman, 1994, p.18).

When we look at the demographics of military families, we see that most military dependent children are born to very young couples who have been removed from their extended support system or other supportive older adults on whom they can rely. For almost all military children, their physical and psychological needs are indeed met during childhood; however, when children begin to assert themselves and/or make emotional demands, which often begins in early to middle adolescence, the parental system may be unable to tend to the children’s needs. Parents who are under a great deal of stress and perhaps faced with a high level of uncertainty around issues like multiple deployments may find themselves resentful or threatened by the needs of the children. The ability to understand how some families in the military are organized, not just because of who the parents are but, more importantly, who the parents are in the midst of the demands of the “warrior fortress” in which they live, is essential in working with these families (Hall, 2008).

Parenting in a Democratic Society

One counselor explained that military couples are often not faced with the typical life decisions or choices of civilian couples, such as buying a home or relocating because of an available career opportunity (Hall, 2008). At the same time, military couples and families are required to relate to and often spend a great many years living in our mostly democratic American world. This counselor often finds it necessary to point out to parents of adolescents that, while the parents may have adjusted well to living in the authoritarian military structure, rebellious teens often see the world in a different way. A typical military parental response to a rebelling teen is to tighten the rules, becoming more vigilant and rigid. This is often the result of the fear of losing control or their place as the head of the household. “Children of the military, whether they live on base or not, live, at least part of their life, in a democratic society; they go to democratic schools and their parents are serving the mission of defending a democratic nation. It is understandable, then, how those who face strictly authoritarian parenting or home life might be confused and perhaps become rebellious” (Hall, 2008, p. 119).

McKay and Maybell (2004) write about the democratic revolution which they define as an “upheaval in all of our social institutions: government, education, the workplace, race relationships, gender relationships and families” (p. 64). As these authors point out, during the last few decades most social institutions and relationships in the United States have operated from an equality identity that values attitudes of equal values and respect. These societal changes require new attitudes toward oneself and others, as well as a new set of knowledge and skills (Hall, 2008; McKay & Maybell, 2004). The military, on the other hand, has not changed to an egalitarian institution: it never will because it could not survive. But, regardless of how the military organizes itself and its members, the military family still lives, at least to some degree, in a democratic society. This means the individual members of the family will often struggle as they go back and forth between the authoritarian world of the military and the democratic world in which they both come from and continue to be a part (Hall, 2008).

While McKay and Maybell (2004) were addressing the conflict in the greater society over the last few decades, their description of the “tension, conflict, anger, and even violence . . . as we move from the old autocratic tradition to a new democratic one” (p. 65) clearly describes the ongoing challenge for military parents. These are valuable insights when understanding the children and the families of the military, many of whom may view the world outside of the military quite appealing and then begin to rebel against the rigid structure they are forced to live within. This theoretical framework can be a useful tool for counselors in helping families understand the need to move from the external often rigid superior/inferior military structure to a more egalitarian structure in the home that encourages and respects each individual in the family but still maintains the hierarchical need for parental control that is necessary for all functioning families (Hall, 2008).

Helping parents to assess their current parenting style, and then to consider how to modify their parenting practices from patterns that are discouraging for their children to those that are encouraging, can be extremely valuable for family growth and development. Whether this is done in a parent training environment or a family counseling setting, helping parents adjust their style will directly impact their children’s behavior. McKay and Maybell (2004) describe three of the most common parenting styles: the coercive parenting style, the pampering or permissive parenting style and the respectful leadership style. Because these authors have years of Adlerian training and writing experience, the reader will recognize that these parenting styles correspond to previous parenting literature written by Adlerian writers. The first two often discourage the healthy development of children; the third is not only respectful, but can be both encouraging and empowering (Hall, 2008).

Coercive Parenting

The coercive parenting style is often the style used to control children for their own good and is often the style of parenting used in parent-focused families, as well as the families of very young parents who have little family support (McKay & Maybell, 2004). It is often the style we find in military parents with children who are rebelling or acting out. The parents maintain control by giving orders, setting rules, making demands, rewarding obedient behavior, and punishing bad deeds (Hall, 2008). McKay and Maybell call this model limits without freedom. These parents almost always have good intentions and want to make sure their children avoid many of life’s mistakes; their goal is simply to teach their children the right way before they get hurt. The need for children to accommodate a subordinate identity may work for a while, at least when the children are young. However, when children want to be acknowledged for their individuality or want to be respected as an individual, this style can result in conflict and power struggles (Hall, 2008). “Kids tend to become experts at not doing what their parents want them to do and doing exactly what their parents don’t want” (McKay & Maybell, 2004, p.71). The results of coercive parenting are often kids who either need to get even, resulting in a constant war of revenge, or kids who submit to the coercion and learn to rely only on those in power to make their decisions (Hall, 2008), either of which can be destructive to the healthy development of children.

Pampering or Permissive Parenting

The permissive parenting style (McKay & Maybell, 2004) is used by parents whose goal is to produce children who are always comfortable and happy, by either letting them do whatever they please or by doing everything for them. This parenting style is referred to as freedom without limits and is often the style that current popular literature calls helicopter parenting. These children often end up considering themselves to be the prince or princess and their parents their servants. They can develop a “strong sense of ego-esteem with little true self- or people-esteem” (McKay & Maybell, 2004, p.72). Often they have under-developed social skills and can become too dependent on others. Parents eventually, however, may resent how much they are doing for their children, leading to conflict and power struggles. With so few limits, children believe they not only can do anything they want, but believe they should be allowed to do anything they want, leading to a sense of entitlement along with a lack of internal self-discipline or self-responsibility (Hall, 2008).

These first two parenting styles can even exist in the same family, where one parent is the authoritarian (in a military family, usually the military parent) and the other is the permissive parent who lessens the rules of the authoritarian parent, particularly when that parent is absent. School behavior often worsens upon the return of the military parent from deployment. If asked, young people will say that everything was fine at home while the service member parent was gone, but now that the parent has returned and started cracking the whip, the teens often turn to rebellion or other inappropriate behaviors (Hall, 2008).

Respectful Leadership

The third parenting style is the only encouraging style for children; it is the style of respectful leadership (McKay & Maybell, 2004), or freedom within limits. The parents value the child as an individual and value themselves as leaders of the family through the guiding principle of mutual respect in all parent-child interaction. Giving choices is the main discipline approach with the goal of building on individual strengths, accentuating the positive, promoting responsibility, and instilling confidence in the children (Hall, 2008). This parenting style, in both the civilian and military worlds, can help build respectful, responsible children. Emphasizing that parents are not giving up their leadership role in order to parent their children is especially important in military families. Combining that with the concept of “respect” makes sense within the military culture.

A counselor told of an Army officer who brought his 16-year-old daughter to counseling because she was acting out. He insisted that she come home at her curfew time and she quit hanging out with the boys he disapproved. She responded with a typical angry look that caused Dad to come unglued. The counselor asked Dad what his biggest fear was for his daughter, thinking that he would be worried about her becoming pregnant, not finishing school, or any of a number of other possible responses. After thinking and, for the first time, with tears in his eyes, Dad said that she might leave him like her mother did. The spirit of counseling changed at that point. With a look of complete astonishment on the daughter’s face, she started crying and told her dad that she thought he wanted her to leave because he couldn’t face her after her mom left. The counselor was able to help Dad see that setting rigid rules that had to be tightened up every time they were broken, might not work as the two of them forged a new relationship and he allowed her to mature into a responsible young woman. Helping him find ways to include her in setting limits and in household decisions, as it was now just the two of them, went a long way in repairing their relationship, as well as in empowering her to make healthy decisions in other parts of her life.

Working with Parents

Helping parents understand how their parenting style impacts child development can often be a counselor’s most valuable teaching tool. While it sounds easy, it is not; parents need guidance and direction on how to give choices, when to give choices, and how to be creative in choosing appropriate consequences. Parents have to learn to start small, start young (when possible), and be willing to make mistakes. The Adlerian principle of the courage to be imperfect also must be a part of parent education. Parents all want the best for their children; helping them promote responsibility and confidence by making adjustments in their parenting style can help them reach these goals. As early as 1984, Rodriguez wrote that in a rank-privileged and -oriented social system like the military, this mix of caste formation and egalitarianism may create a difficult dichotomy, particularly for children and adolescents struggling for their identity. This dichotomy can be exacerbated by the parent-focused nature of the military when parents are concerned about how their child’s misbehavior might affect the parent’s status in the military. Children become sensitive to this parental anxiety and the anger that follows when they break community rules or military social norms. In some military communities, particularly those that are isolated and where rules are strongly enforced, children have little room to make mistakes or test the limits of authority in a normal, developmental manner, without impacting the family status or the military parent’s career (Hall, 2008).

It is important to point out that not all military families struggle with these issues; the great majority carry out their parenting duties extremely well and raise healthy children, often in the midst of difficult situations. Jeffreys and Leitzel’s (2000) study noted that a caring relationship and low family stress is associated with resiliency. If children have an emotionally supportive relationship with their parents, they are more likely to demonstrate high levels of self-esteem and healthy psychological development. Their study (Jeffreys & Leitzel, 2000) of military families suggests that family climate promotes the participation in family decision-making and is positive for adolescent identity development. Effective communication patterns facilitate family interaction and are associated with social competence. This finding is reflected in McKay & Maybell’s (2004) respectful leadership style of parenting and can help mental health counselors focus their work on helping military parents learn the parenting skills necessary to reach their goals of having competent, healthy and responsible children, as well as coping with the sometimes overwhelming challenges they face while serving in the military.

References

Donaldson-Pressman, S., & Pressman, R. M. (1994). The narcissistic family: Diagnosis and treatment. San Francisco,

CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hall, L. K. (2008). Counseling military families: What mental health professionals need to know. New York, NY:

Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group.

Jeffreys, D. J., & Leitzel, J. D. (2000). The strengths and vulnerabilities of adolescents in military families. In J. A. Martin, L. N. Rosen, & L. R. Sparacino, (Eds.). The military family: A practice guide for human service providers (pp. 225–240). Westport, CT: Praeger.

McKay, G. D., & Maybell, S. A. (2004). Calming the family story: Anger management for Moms, Dads, and all the kids. Atascadero, CA: Impact.

Rodriguez, A. R. (1984). Special treatment needs of children of military families. In F. W. Kaslow & R. I. Ridenour (Eds.) The military family: Dynamics and treatment (pp. 46–72). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Wertsch, M. E. (1991). Military brats: Legacies of childhood inside the fortress. New York, NY: Harmony Books.

Lynn K. Hall, NCC is Dean of the School of Social Sciences at the University of Phoenix. Correspondence can be addressed to Lynn K. Hall, College of Social Sciences, University of Phoenix, 4605 E. Elwood St., Phoenix, AZ 85040, lynn.hall@phoenix.edu.

Sep 11, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

George Davy Vera

In the worldwide community it is not well known that counseling and guidance professional practices have a long tradition in Venezuela. Therefore, this contribution’s main purpose is to inform the international audience about past and contemporary counseling in Venezuela. Geographic, demographic, and cultural facts about Venezuela are provided. How counseling began, its early development, and pioneer counselors are discussed. The evolution of counseling from an education-based activity to counseling as a technique-driven intervention is given in an historical account. How a vision of counselors as technicians moved to the notion of counseling as a profession is explained by describing turning points, events, and governmental decisions. Current trends on Venezuelan state policy regarding counselor training, services, and professional status are specified by briefly describing the National Counseling System Project and the National Flag Counseling Training Project. Finally, acknowledgement of Venezuela’s counseling pioneers and one of the oldest counseling training programs in Venezuela is described.

Keywords: Venezuela, history of counseling, clinical interventions, policy, training programs

Venezuela is located on the northern coast of South America, covering almost 566,694 square kilometers (km; 352,144 square miles). It is bordered by the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, Guyana, Brazil, and Colombia, with a total land boundary of 4,993 km (3,103 miles) and a coastline of 2,800 km (1,740 miles). Its population is approximately 29 million and mostly Catholic. Some aboriginal groups practice their own traditional magical-religious beliefs. Since its independence, emigrants from different parts of the world have helped build the country’s culture and economy. Diverse populations of Arab, Dutch, Chinese, and Japanese, among others, live in Venezuela.

Even though several ethnic groups prevail in the country today, three groups are clearly distinct from its origin: European white, African black and Native aborigines. After five hundred years of blending, three different culturally and ethnically groups have emerged: Mulato (white and black), Zambo (black and aborigine), and Mestizo (white and aborigine). Although Venezuela has ethnic compositions and mixtures, all Venezuelans have the same rights and duties under the Bolivarian Constitution of 1999. More Venezuelan differences and prejudices are related to social, educational, economic, and political status.

Economically, Venezuela has one of the largest economies in South America due to its oil production; however, a large number of its population remains in poverty. Today, the current administration has created different popular programs, called missions, to deal with most Venezuelans’ needs including lack of education, employment, health care, and public safety, among others. So far, according to the United Nations (UN) and UNESCO’s official reports, Venezuela has reached most of its millennium goals established by the UN. Politically, after several years of turmoil, Venezuelan society reached a normal democratic institutional peace in 2004.

Early Developments of Counseling in Venezuela

During the 1930s, counseling in Venezuela began as a form of educational guidance and counseling concerned with academic and vocational issues using mainly psychometric approaches. Some Venezuelan counseling pioneers were European emigrants. In fact, during the 1940s, some school counseling services were created by Dr. Jose Ortega Duran, an educator; Professor Miguel Aguirre, a counselor; Professor Vicente Constanzo, teacher and philosopher; and Professor Antonio Escalona, a career counselor and professor (Benavent, 1996; Calogne, 1988; Vera, 2009). Because of the education and training of these early pioneers, counseling in Venezuela was conceived as an educational, vocational, and career-oriented service.

A formal definition of the counseling and training of professional counselors has slowly evolved from the 1960s to today. Because of the oil industry development, Venezuela moved from an agricultural to an industrial economic base. Because of this, the Venezuelan population grew rapidly and rural farmers moved to the major cities, which were demanding more workers, specialized employees, and technicians. Therefore the demand for better education to satisfy new jobs related to industrial demands and pressured the government to create new policies concerning education. One of the new policies regarded counseling and guidance services. Therefore, in the early 1960s the government created the first counselor education training program (Calogne, 1988; Moreno, 2009; Vera, 2009).

By an agreement between the Ministry of Education and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), counseling professors from the U.S. were hired to train school teachers in counseling and guidance. The training focused on personal counseling techniques and strategies, counseling theory and methods, and educational counseling. Because the training emphasized basic counseling knowledge and techniques for school teachers, a vision of counseling and guidance as educational activities within the scope of the school teacher role emerged. Accordingly, counseling and guidance was understood as a technique-based activity oriented to help students with academic, vocational, career, and personal issues. Later, the Ministry of Education requested that the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas create a formal, three-semester educational training program in counseling and guidance.

As a result, in 1962 the Ministry of Education requested that the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas house the first formal counselor education program in Venezuela. Counseling and guidance was conceived as knowledge and intervention techniques to help with students’ personal growth and academic performance. The term Orientación was chosen to better signify counseling and guidance in Venezuela’s Spanish language. Graduates from this program received a college diploma as orientador. Both terms, orientación and orientador, were thus used in the country for the first time.

Another consequence of the counselor education program at the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas was its contributions to a new vision of counseling as a technique-oriented educational program. Therefore, counseling was conceived as a technical occupation that emerged within the scope of education. By this time, counseling had achieved official and public recognition as a social occupation that required proper education and a set of formal conditions for practice. The Ministry of Education used this new vision of counseling to create the first jobs defined as counselor positions within Venezuela’s educational system (Vera, 2009).

From Counselors as Technicians to the Counseling Profession

Shortly after the first graduates in counseling started their practice, the Ministry of Education understood that the practice of counseling and guidance was more complex than originally perceived and realized that the high demand for counseling services was calling for rapid institutional answers to counseling-related questions. As a result, the National Counseling System, known as the Counseling Division of the Ministry of Education, was developed. This organizational structure was responsible for all counseling matters countrywide, including hiring conditions, developing counseling services, supervising, and training requirements. From this Division, counseling as a profession was envisioned as a human development model (Aquacviva, 1985; Calogne, 1988).

Because counselor employment was now available within the Ministry of Education, several universities established guidance and counseling training options as a five-year bachelor’s degree. Consequently, the first bachelors’ degrees in education majoring in guidance and counseling (mención orientación) were granted in the early 1970s. Master’s level degrees in guidance and counseling granted by the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas were also awarded during this time.

Some of the early graduates from these programs went abroad, mainly to the U.S., to obtain advanced counseling and guidance education and training at the master’s and doctoral levels. Upon returning to Venezuela, they engaged in teaching and training in counseling and guidance at different colleges and some were hired by the Ministry of Education. Other graduates concentrated their energy on organizing counseling professional associations. As a result, American theories, models, and views of the counseling profession in the 1970s and 1980s were fused with Venezuela’s view of counseling and guidance (Vera, 2009).

Because most Venezuelan counselors had been educated abroad, a number of trends in counselor education were adopted. For instance, some bachelors’ level counseling education programs were based on a vision of guidance and vocational education (e.g., Venezuela Central University and the University of Carabobo), while other programs assumed a vocational and academic perspective (e.g., Liberator Pedagogical University), and yet others implemented individual, lifelong approaches (e.g., The University of Zulia and the University Simon Rodriguez). Finally, the Center for Psychological, Psychiatric, and Sexual Studies of Venezuela clearly embraced an educational and mental health counseling standpoint in masters’ level training. (However, for political and governmental reasons, some of these early programs no longer exist.)

Between the 1970s and 1980s professionalism in counseling was embraced because counseling- and guidance-related organizational movements emerged. Counseling associations were organized and began to promote a vision of counseling as an independent profession from education, psychology, and social work. One of these associations was the Zulia College of Professional Counselors (ZCPC), which was responsible for raising the visibility of professional counseling in Venezuela by creating the first Counseling Code of Ethics, advocating for counseling jobs, and becoming a valid interlocutor between professional counselors and the government.

The ZCPC was established by a group of counseling professors and early graduates from the bachelors’ degree of education in counseling and guidance. During the 1970s and 1980s, counselors in this organization started developing a cultural base for counseling knowledge. In particular, ZCPC established professional meetings for discussing counseling profession matters such as advanced education, professional identity, and social responsibility.

By this time, counseling master’s programs were available in several parts of Venezuela. Hence, professionalism came to light and important matters for counseling’s future development were assumed by counselor educators, practitioners, and associations.

Current Trends: Contemporary Concerns for Professional Practice and Education

Currently, several professional matters regarding counseling are taking place in Venezuela, one being the status of counseling as an independent profession. The Venezuela Counseling Associations Federation (FAVO) will soon introduce a legislative proposal concerning professional counseling practice. If it is passed, Venezuelan counselors will have their first counseling practice law granting counselors’ independent professional practice based on research, knowledge, specified training, and educational requirements.

Another important matter is the creation of the Venezuela Counseling System. This system will organize and provide counseling to the population by a diverse delivery of services and programs based on a vision of counseling for personal, social, cultural, and economical enhancement within the context of a humanistic, democratic, participatory, and collective society. The system is designed and based on the Venezuela Bolivarian Constitution, which guarantees human rights related to social inclusion and justice, freedom, education, mental health, vocational needs, employment, lifelong support, and opportunities for individual development and family prosperity. The system is organized into four areas: education, higher education, community, and the workplace or economic sector. The system is already approved by the Ministry of Higher Education and the formal government resolution and implementation process is pending.

The system embraces advanced concepts and new trends related to professionalism, practice, and the social responsibility of counseling professionals. This includes certification for counseling practitioners, supervision, and credentialing via continuing education for professionals in order to ensure quality. Structurally, the system will be connected to all Venezuelan Ministries for functions and planning purposes, but will be independently managed by a national committee appointed by the Ministry of Higher Education, holding advanced degrees in counseling and appropriate counseling credentials.

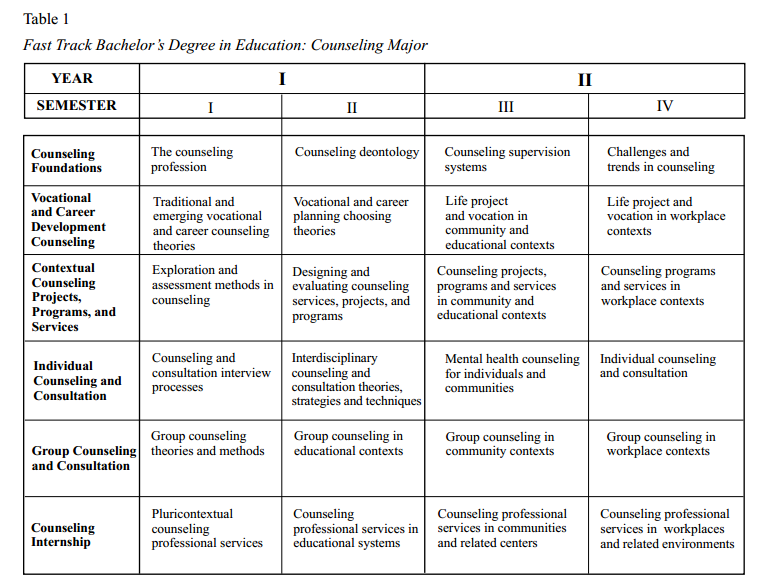

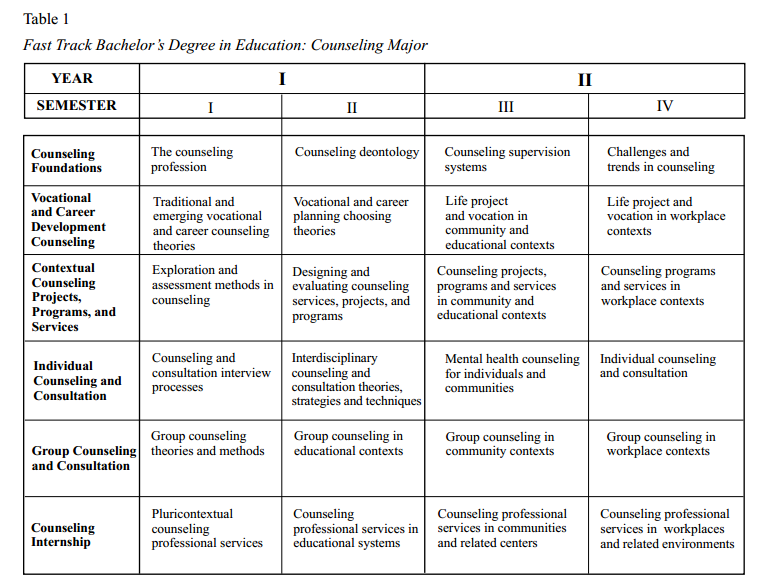

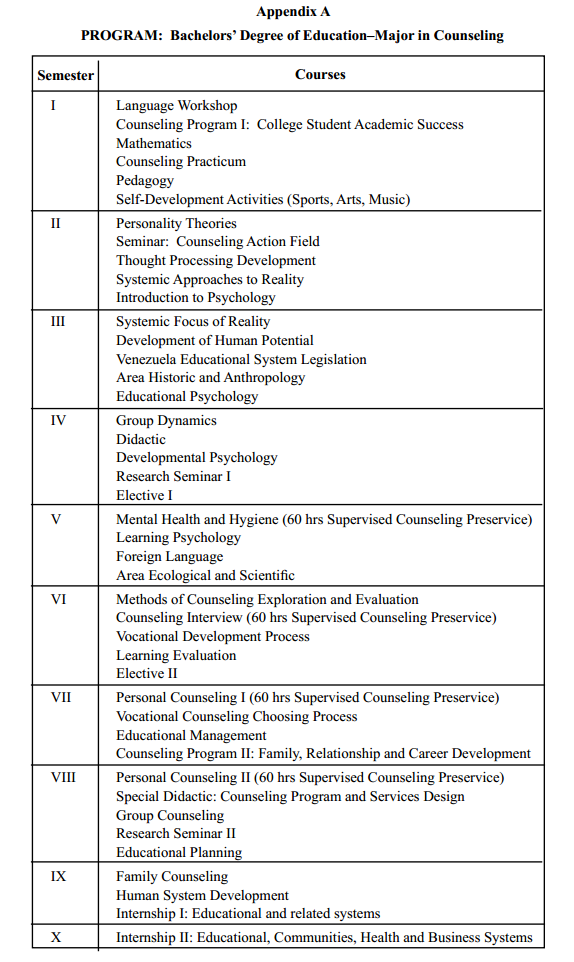

A third matter is related to counseling training programs. Because the Counseling National System will require a large number of trained counselors in the next ten years, new counseling training programs will be created by public and private universities to ensure the quality of counselor training and to satisfy system requirements. Consequently, the government has requested that counseling experts propose a unique counseling training program based on core counseling knowledge, techniques, supervision, and other key features. For details on the proposed counseling program coursework, see Table 1.

The proposed National Counseling Professional Program (NCPP) will be at the bachelor’s level and four semesters long. A unique prerequisite of this program is that applicants must already hold one of these bachelors’ degrees: education, psychology, social work, sociology, industrial engineering, philosophy, pedagogy, or physician.

The proposed NCPP will be organized into core areas and will educate counseling professionals according to the following general objectives:

1. Educate professional counselors to satisfy the needs of the Counseling National System, its subsystems, and any other professional counseling contexts.

2. Develop critical, reflective, dialectical and dialogical counseling professionals. Understand theoretical and conceptual information related to the counseling field and its interdisciplinary sources.

3. Acquire the theory based and applied competencies of the counseling profession in diverse contexts.

4. Understand Venezuelan counseling’s historical roots and its international origins.

5. Understand the ethical dimensions of the counseling profession and the legal characteristics of counseling practice.

6. Actively participate in the development of solidarity, participatory and responsible collectivist citizenship.

7. Articulate counseling professional actions with Venezuela’s social, cultural, and economic development.

8. Use the cultural and social bases of the counseling profession in creating lifelong counseling services.

9. Bond the training and practices of professional counselors with plans and guidelines for Venezuela’s cultural, social, and economic development.

10. Train professional counselors needed for the Venezuelan police.

Other counseling training programs will be developed according to the official training program. Institutions may develop their own specific program, but must include the official requirements.

A last concern is professional counselor certification, supervision, and continuing education. FAVO has worked on these matters since 2004 in collaboration with the NBCC International. FAVO is developing Venezuela’s first National Counselor Certification System as well as conceptualizing a national supervision model and continuing education. FAVO granted the first group of national certified counselors in 2010 and is planning for the first group of trained and certified counselor supervisors in 2011.

Final Thoughts

After years of counselor education evolution and counseling services growth, the professionalization of counseling in Venezuela is now happening, but it depends on Venezuelan counseling leaders to develop a strong advocacy movement. Accordingly, Venezuela’s current political climate has the extraordinary opportunity to pass the Venezuela Counseling Law Proposal in the National Assembly. This may be possible if FAVO has successes in the implementation of the Venezuela National Counseling Certification System because this can help in the task of alerting Venezuela’s professional counselors. Accordingly, counselors’ sense of professionalism might spark the enthusiasm needed for involvement in a strong advocacy movement.

Finally, according to experiences in different parts of the world, it can be concluded that not only in Venezuela, but worldwide, the profession of counseling is an emerging phenomenon; therefore, international counseling institutions and organizations need to begin acting on how to face the worldwide challenges for professional counselors.

References

Benavent, J. (1996). La orientación psicopedagógica en España. Desde sus orígenes hasta 1939. Valencia, VZ: Promolibro.

Calogne, S. (1988). Tendencias de la Orientación en Venezuela. Cuadernos de Educación 135. Caracas, VZ: Cooperativa Laboratorio Educativo.

Moreno, A. (2009). La orientación como problema. Centro de investigaciones populares. Caracas, Venezuela: Colección Convevium.

Vera, G. D. (2009). La profesión de orientación en Venezuela. Evolución y desafíos contemporáneos. Revista de Pedagogia, Universidad Central de Venezuela.

George Davy Vera teaches in the Counselor Education Program, Universidad de Zulia, Maracaibo, Venezuela. Dr. Vera expresses appreciation to Dr. J. Scott Hinkle for editorial comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Correspondence should be directed to George Davy Vera, avenida 16 (Guajira). Ciudad Universitaria, Núcleo Humanístico, Facultad de Humanidades y Educación. Edificio de Investigación y Postgrado. Maracaibo, Venezuela, gdavyvera@gmail.com.

Sep 10, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

George Davy Vera

A personal description of the international counselor education program at the University of Zulia in Venezuela is presented including educational objectives of the counseling degree, various services counselors are trained to provide, and a sample curriculum. This description serves as an example of one international counselor education program that can be used as a model for burgeoning programs in other countries.

Keywords: Venezuela, University of Zulia, international counseling, counselor education, counseling services, curriculum

Venezuela’s early counseling pioneers at the University of Zulia, some of whom were trained in the United States (e.g., Dr. E. Acquaviva, Dr. C. Guanipa, A. Busot, M. Ed.; A. Quintero, M.Ed., M. Socorro, M.Ed., D. Campo, M.Ed.), were pioneers responsible for influencing and crafting the counseling and guidance culture at the University of Zulia. Accordingly, I would like to describe one of the oldest and most well known counseling training programs in Venezuela. This program is chosen because many past and present counseling leaders in Venezuela were educated at the University of Zulia.

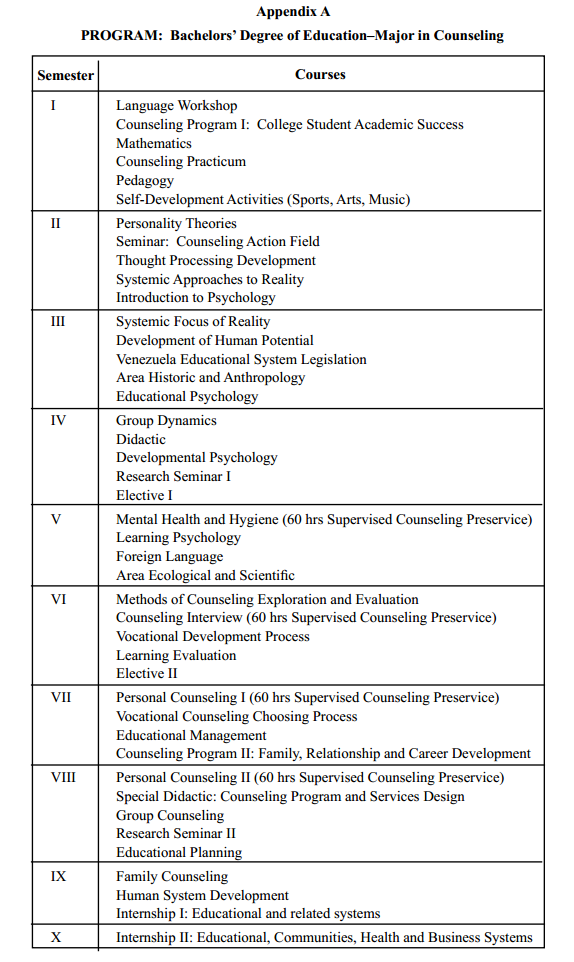

Initially in the early 1970s, this bachelor’s level counseling program was conceived as educational counseling (asesoramiento) and vocational guidance (orientación vocacional) as a specialization track within the major of Pedagogical Science. Graduates from this program received a Licentiate in Education, Major in Pedagogical Sciences in the area of counseling (Licenciatura en Educación, Mención Ciencias Pedagógicas, Area de Orientación). According to the University of Zulia’s official archive (1970-2010) on counseling academic and curriculum development, professional services related to individual, vocational or educational counseling and guidance were understood as orientación. Therefore, the Spanish word was implemented to better communicate the meaning of professional counseling and guidance. Historically, the academic choice of using this term at the time was congruent with the Ministry of Education’s decision in 1962, when the terms orientación and orientador were officially adopted to describe guidance professionals and counseling practitioners, respectively. The current bachelors’ degree is five years long (10 academic semesters, for details see Appendix A).

According to the Academic Updated Curriculum Design (Curriculum Commission of Psychology Department, 1995), the education of professional counselors is conceived upon several key concepts:

• Professional identity reflects that graduates are trained to perform counseling and guidance tasks within the educational system and other professional and organizational agencies.

• Counseling professionals help people develop within the social environment, assist with the processes of psychosocial functioning, and effectively deal with developmental changes and stressful life events.

• Professional counselors trained at the University of Zulia are competent in performing counseling tasks such as:

o designing, implementing, and evaluating counseling services.

o developing prevention or remediation programs emphasizing personal, social, academic, vocational, work, recreational, and community needs at any developmental phase using individual or group strategies.

The main educational objectives of the counseling major are:

1. Diagnosing human system characteristics within the educational, organizational, assistance, judicial, and community contexts.

2. Performing counseling and consultation.

3. Designing, implementing, and evaluating services.

4. Generating research in counseling.

Graduates provide counseling services in different areas of human services:

A. Personal-social counselors help clients deal with issues related to social roles and gain more understanding of themselves within their sociocultural context. The main purpose of the personal-social intervention area is to help clients deal with mental health and personal growth issues and to reach psychological stability. In this area, some helping processes are related to:

• psychological development: self-esteem, decision-making, emotional stability, psychosexual maturity, and intellectual potential.

• social development: interpersonal relationships, work and academic motivation, social adjustment, and ethical values.

• family development: prevention, couples relationships, parents and children, family crisis intervention including divorce, terminal and lifelong sickness, bereavement, and human sexuality.

B. Academic counselors help clients deal with issues related to learning and the role of the learner. Helping processes are related to educational adjustment, academic attitudes, cognitive development, academic performance, and consultation with school teachers, families, and communities.

C. Vocational counselors focus on individual talents, vocational potential and tendencies, as well as roles within the workplace. Vocational counselors’ tasks are mainly focused on several facets, including assessment, decision-making, work development, academic needs, workplace readiness, and positive work attitudes.

D. Work counselors provide counseling services to help individuals and organizations with shared objectives to reach mutual satisfaction and development. This area includes process management, career planning and development, work motivation and communication, work-related decision-making, evaluation, conflict resolution, work-service quality, leadership, performance, and teamwork.

E. Community and recreational counselors provide counseling services for community life enhancement. Counseling processes in this area include community resources and needs, civic practices, positive utilization of recreation and free time, community creativity, organization and planning, cultural and artistic manifestations, and social transformation.

Graduates are trained in three core counseling professional competencies:

• Human system diagnostics: use of diverse tools for diagnosing human systems and individual psychological, educational, social and developmental characteristics.

• Program and service design: conceptualize and evaluate human processes in order to design and administer counseling services for individuals, groups, communities, and organizations.

• Counseling and consultation: provide professional services concerning human potential development and to meet psychological, emotional, behavioral, educational, social, organizational, and community needs.

References

Curriculum Commission of Psychology Department. (1995). Counseling education program. Maracaibo, VZ: University of Zulia.

George Davy Vera teaches in the Counselor Education Program, Universidad de Zulia, Maracaibo, Venezuela. Dr. Vera expresses appreciation to Dr. J. Scott Hinkle for editorial comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Correspondence should be directed to George Davy Vera, avenida 16 (Guajira). Ciudad Universitaria, Núcleo Humanístico, Facultad de Humanidades y Educación. Edificio de Investigación y Postgrado. Maracaibo, Venezuela, gdavyvera@gmail.com.

Sep 10, 2014 | Article, Volume 2 - Issue 1

Kylie P. Dotson-Blake, David Knox, Marty E. Zusman

Despite growing attention to the subject, a dearth of information exists regarding college students’ perceptions and process of meaning-making related to the act of oral sex. Such perspectives and allied social sexual scripts can have considerable consequences on the sexuality and sexual health of older teens and college-aged populations. The present research serves to elucidate such perspectives and presents a profile of college students’ degree of agreeing that oral sex is not sex. Over half (62.1%) of a sample of college students (N = 781) at a large southeastern university agreed that oral sex is not sex. Response rates across demographic groups are presented and factors that influence such perspectives are examined. Sexual script theory serves as the theoretical framework. Implications and limitations are explored.

Keywords: oral sex, social sexual scripts, college students, script theory, sexuality, sex counseling

Television talk show hosts, The Washington Post (Stepp, 2005) and Science Daily (University of California, San Francisco, 2005) have all had recent headlines related to oral sex in the older teen and college-aged populations. Because of these and other popular media sources, sex educators, parents and others have become more aware of oral sex engagement among college students and more concerned about the impacts of this engagement. Although society members are becoming concerned about this topic, limited information regarding college students’ perceptions and process of meaning-making related to the act of oral sex is available in the literature. To develop sexuality education curriculum and resources targeted at young people engaging in oral sex, professionals must first identify those most likely to engage in oral sex, their process of meaning-making around this engagement and risks young people are exposed to as a function of their engagement in oral sex.

In an effort to provide insight into this population’s process of meaning-making related to engagement in oral sex and initial information about characteristics of college students likely to engage in oral sex, this article presents the findings of a survey conducted at a large southeastern university. An initial profile of undergraduates who agreed with the statement “Oral Sex is Not Sex” is offered and findings are analyzed through the lens of social sexual script theory to explore the process of meaning-making related to the perceptions of participants regarding oral sex. We hope this information will assist sex educators, counselors, health professionals and parents in efforts to target individuals likely to engage in oral sex to minimize risks related to oral sex in the college student population. Thus, the purpose of this study was to provide a profile of undergraduates who agreed with the assertion that oral sex is not sex and to explore the links between participant responses and sexual scripts to illuminate fully how these participants perceived oral sex engagement. This profile is important because recent research suggests that young people perceive oral sex as safe, with few potential health risks (Halpern-Felsher, Cornell, Kropp, & Tschann, 2005). However, engaging in oral sex may expose individuals to the risk of viral and bacterial infections, including chlamydia, gonorrhea and herpes (Edwards & Carne, 1998a, 1998b). Consequently, it is critical that counselors fully understand the context and perceptions of college students in order to provide information to assist with healthy decision-making in developmentally-appropriate ways for these clients.

Theoretical Foundation

Sexual script theory situates perceptions of sexual interactions within the social context to explain how sexual identity and sexuality are shaped by social cultural messages (Frith & Kitzinger, 2001). Consequently, what is perceived to be “real” sex is defined by the society within which one exists, individual identity and socio-cultural normative sexual scripts. Sexual scripts vary across individuals, but often common elements exist within sexual scripts associated with particular cultural groups (Wiederman, 2005). As a social constructionist approach to exploring the development of sexuality, sexual script theory has been primarily used as a qualitative method of research (Simon & Gagnon, 2003). However, recent research has applied sexual script theory in quantitative research exploring the impact of exposure to sexually explicit material on young people (Stulhofer, Busko, & Landripet, 2010). For the study presented in this article, results were found using quantitative methods and then a qualitative exploration of themes that emerged from the quantitative data yielded links to sexual scripts postulated by sexual script theory.

Sexual Scripts and Heterocentric Standards

One sexual script prevalent in Western cultures, the traditional sexual script (Rostosky & Travis, 2000), serves to situate sexual intercourse between heterosexuals as real sex. This sexual script serves to disenfranchise sexual minorities by failing to recognize the full spectrum of sexual acts occurring between persons of any gender and the meanings attributed to these acts. Furthermore, not only is sex limited to heterosexual intercourse, but the concept fundamentally depends on male ejaculation since it is the male orgasm that denotes both the number of times a couple has sex and is the culmination (the climax) of sex (Frye, 1990). This phallocentric approach with regard to the concept of sex limits the power of women to be equal partners in a heterosexual relationship (Bhattacharyya, 2002). Consequently, these heterocentric standards for what qualifies as sex means that lesbians do not have real sex since lesbian sex does not involve penile penetration.

Within this sexual value system, vaginal-penile penetration/intercourse is at the apex of what constitutes sex, such that all other non-coital sexual practices/behaviors—such as oral sex—are considered foreplay and as a result have not been researched as fully and comprehensively as vaginal-penile penetration/intercourse. Much of sexual research has been situated within Western culture, resulting in the firm entrenchment of the traditional sexual script (Rostosky & Travis, 2000) within research methods and processes. This social entrenchment of heteronormative standards impacts the social sexual scripts college-aged individuals hold and apply in their sexual engagement (Bhattacharyya, 2002).

Peer groups have a strong influence on sexual behaviors, particularly among young adults. Peer group shifts in perceptions and values, when it comes to sex and sexual activity, will in turn impact sexual trends and patterns within peer groups. For college students, peer group perceptions powerfully impact individual perceptions and behaviors (Carter & McGoldrick, 1999). Prinstein, Meade, and Cohen (2003) discerned a positive relationship between young people’s reports of oral sex engagement and peer popularity. This suggests that peer culture for college students supports oral sex practice.

Peer group perceptions are formed within the context of the larger society and events, media and social issues within the society. One such societal event relevant to this discussion is the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal. At the heart of the scandal is Clinton’s famous utterance, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky” (Clinton, 1998). Whether his perception of oral sex as not real sex is due more to his personal perception based upon the traditional sexual script (Rostosky & Travis, 2000) or Clinton’s cunning sense of self-preservation will never be known. What is known, however, is that his statement and the subsequent maelstrom of controversy that ensued solidly asserted the question: “Is oral sex really sex?” into the public domain for debate.

Prevalence of Oral Sex Engagement in Young Adult and College-Age Population

In 2002, as part of the National Survey of Family Growth, 10,208 people ages 15–19 were included in the overall sample, and, of these respondents, more than half of males (55%) and females (54%) reported engaging in oral sex (Mosher, Chandra, & Jones, 2005). Richters, de Visser, Rissel, & Smith (2006) analyzed data from the Australian Study of Health and Relationships from a representative sample of 19,307 Australians aged 16 to 59 and found that almost a third (32%) of the respondents reported that oral sex was included in their last sexual encounter. Similarly, in a study of 212 participants ranging in age from 15 to 17, Prinstein, Meade, and Cohen (2003) reported that a third of the males and half of the females had engaged in oral sex in the past year. These studies reveal that many of the college-aged population are engaging in oral sex.

Oral Sex Scripts and Pop Culture

As dialogue about oral sex entered contemporary popular culture, it also became mainstreamed into the young adult vernacular and embedded into the tapestry of social mores and norms. Sexual script theory (Gagnon & Simon, 1973) emphasizes that social norms play a significant role in governing college students’ processes of meaning-making regarding health information and subsequent health and sexual behaviors. This theory holds at its foundation the understanding that sexuality is borne from cultural norms and messages that define what is deemed sex and socially-appropriate responses in sexual situations and encounters (Frith & Kitzinger, 2001).

In considering the impact of culturally-laden sexual norms and social sexual messages, one may infer that as oral sex has entered contemporary discourse, the social norms emerging from this discourse have impacted college students’ perceptions of and participation in oral sex. Understanding this process of social norm-belief-behavior interaction and possible consequences, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs), is critically important for sex educators, counselors and therapists working with the college-aged population, as these clients have intense levels of interactions with peers attuned to contemporary popular culture.

Young Adults and Sexually Transmitted Infections

Researchers also have found that young people are increasingly experiencing high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Prinstein, Meade, & Cohen, 2003). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2006), females who are 15–19 years of age reported the highest rates of all other demographic groups for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Of the 19 million STIs reported each year in the U.S., Weinstock, Berman, and Cates (2004) estimated that almost 50% occur in individuals who are 15–24 years of age. From these high rates of STIs in the young adult population, it can be inferred that more education around protection and safe sex engagement is necessary. Recent research has shown that young people also are concerned about the need for safety in sexual engagement and as such have turned to oral sex because they feel it presents fewer health risks (Halpern-Felsher, Cornell, Kropp, & Tschann, 2005). However, oral sex also presents risks of STIs. In a summary of research over more than 35 years regarding oral sex as a possible means of transmitting STIs, Edwards and Carne (1998a, 1998b) noted that oral sex may transmit viral and bacterial infections, including gonorrhea, chlamydia and herpes. Consequently, college students need to be educated about the risks of STI transmission through oral sex to minimize the harmful consequences.

The Need to Explore Perceptions of Oral Sex

In view of the various studies reporting the frequency and consequences of oral sex among young adults and college students, we emphasize the importance of educating this population about safe practices related to oral sex. A first step in this process is to assess the perceptions of this population in regard to oral sex. In short, though the research suggests that this population is engaging in oral sex (Prinstein, Meade, & Cohen, 2003), little is known about how they perceive the act and what meaning they attribute to the behavior in terms of their sense of self and sexual identity development. How do college students perceive oral sex? Do they perceive it to be real (i.e., intercourse) sex? How does it shape a young adult’s sense of self? Do college students feel that by engaging in oral sex and other non-coital behaviors that they are practicing a form of abstinence, that they are maintaining their virginity? Finding the answers to these questions may assist sex educators, counselors and therapists in developing comprehensive sexuality education programs incorporating resource awareness, prevention and health-focused knowledge for this population (Bay-Cheng, 2003).

In an effort to begin to address these questions and process, this article presents the findings of a study exploring the perceptions and behaviors of college students regarding oral sex. The purpose of the research was to identify a profile of undergraduates who agree with the assertion oral sex is not sex. This profile can be used to identify college students who may be more likely to engage in oral sex, allowing clinicians and educators to plan and implement developmentally-appropriate measures in contexts most likely to reach this population. An exploration of the intersection of social norms, utilizing sexual script theory, with characteristics prevalent in the profile that emerged will be discussed, as well as the implications and limitations of the study.

Sexual Script Theory and Perceptions of Oral Sex

By exploring research focused on oral sex engagement, the college-aged population and prevalent social sexual scripts, one may make significant inferences regarding this population’s perceptions of oral sex and process of meaning-making related to this sexual act. Again, it is important that the authors note that sexual scripts are based upon individual experience and social engagement and as such are impacted by the intersecting identity characteristics of individuals. Sexual scripts are reflective of culture and thus some elements will be common to members of the identified cultural group to which the script refers (Geer & Broussard, 1990). However, personal identity is multi-faceted and individuals belong to many different cultural groups by the nature of their race, ethnicity, religion, social class, sexual identity, education status, etc. Consequently, there may be wide variation in sexual scripts across individuals, even within a specific cultural group or sub-group (Wiederman, 2005).

Remaining cognizant of the diversity of sexual scripts across cultural groups, the authors will lead an exploration of selected dominant sexual scripts that may impact college-aged individual’s perceptions of and engagement in oral sex in the U.S. This exploration is not intended to be exhaustive; it is simply meant to serve as a foundation for understanding the potential of sexual scripts to impact these individuals’ processes of meaning-making related to oral sex. Finally, the authors recognize that sex extends far beyond penile penetration of a vagina. Unfortunately, the majority of research findings gleaned from a comprehensive review of the professional literature promote heteronormative standards by focusing solely on sex as the act of sexual intercourse between individuals of different genders. Consequently, the discussion of current professional research is limited in scope, indicating the need for additional research exploring the full range of sexual activities and sexual scripts impacting young adults and the college student population of any gender and sexuality.

Perception One: Oral Sex is Safe

The current professional literature suggests that young adults and college students articulate diverse reasons for engagement in oral sex. A reason that emerges dominantly from multiple studies is the perception that oral sex is safe with minimal risk and consequence (Halpern-Felsher et al., 2005; Remez, 2000). In a study of ninth-graders in California, participants were unlikely to use barrier protection when engaging in oral sex (Halpern-Felsher et al., 2005), indicating that they felt the practice of oral sex carried minimal risk for STIs. Possibly contributing to adolescent and teen perceptions of oral sex as safe are the sex education programs to which this population is exposed. Data suggest that abstinence-only and faith-based sex education programs do little to educate young adults on the very real and possible dangers associated with oral sex—i.e., the spread of STIs (Lindau, Tetteh, Kasza, & Gilliam, 2008). This lack of information may lead to the perception that because risks related to oral sex are not talked about, it must be safe. Surveys find that most young adults are misinformed, in that they are taught that STI risks are only associated with vaginal-penile intercourse. In sum, we surmise that these sex education programs, shifts in societal perceptions of and sexual scripts related to oral sex, and the use of oral sex as a substitute for intercourse may have a strong effect on the perceptions of the college age population reflecting that oral sex is safe sex.

Perception Two: Oral Sex Mitigates Religiosity and Sex Guilt Tension

Studies have shown strong correlations between degree of religiosity and patterns of sexual behavior. Kinsey, Pomeroy and Martin (1948, 1953) were some of the first to show empirically that religious identification limits sexual behaviors among the unmarried. Schulz, Bohrnstedt, Borgatta, and Evans (1977) also found that religiosity had a significant inhibiting effect on sexual behavior for both men and women. A study conducted by Wulf, Prentice, Hansum, Ferrar, and Spilka (1984) examined the sexual attitudes and behaviors among evangelical Christian singles, and found overall a more conservative outlook in sexual beliefs compared to the cultural norms. Of this group, those that were intrinsically faithful—that is, the more intensely religious who had a strong identification with traditional Christian values—and were not involved in a relationship, displayed the most conservative sexual attitudes. Among the more devout and single, the strongest correlations were found with respect to premarital intercourse and oral sex, in that these individuals were least likely to have engaged in these two activities.

Numerous studies have shown strong relationships between religiosity and sex guilt (Langston, 1973; Mosher & Cross, 1971). Those with conventional religious beliefs are more likely to have sex guilt, which in turn inhibits sexual behavior (Sack, Keller & Hinkle, 1984). Individuals with sex guilt are more absolutist in their orientations to sex and are less sexually active, since transgressing these strict sexual parameters might elicit intense displeasure and an antagonistic relationship with their religious community. By perceiving oral sex as not real sex, young adults and college students may be able to mitigate the tension between religious beliefs and sex guilt. For instance, a meta-analysis of studies looking at sexual attitudes and practices among young adults found that a majority believe oral sex to be less intimate compared to intercourse and that oral sex does not spoil virgin status (Remez, 2000). Many abstinence-only and faith based sex education programs now include a new push for virginity pledges, reinforcing the notion that vaginal intercourse is what is most at stake when it comes to preserving one’s virgin status.

Perception Three: Oral Sex Requires Less Commitment

Studies examining sexual attitudes and practices have found that sexual experience seems to be associated with a more liberal orientation to sex. This more liberal orientation to sex has been linked with “hooking up,” defined as having sex with someone one has just met (Richey, Knox, & Zusman, 2009). Paul, McManus, and Hayes (2000) examined the hookup culture within a college setting. They found that students high on impulsivity had a more noncommittal orientation with regard to relationships, displayed a high level of autonomy, and were much more likely to engage in both coital and non-coital hookups.

Social scripts are shared interpretations and have three functions: to define situations, name actors, and plot behaviors. For example, the social sexual script operative between two college students who are hooking up is to define the situation (a hookup, not a relationship where they will see each other tomorrow), name the actors (male and female college students out to meet someone for an evening of fun), and plot behaviors (go back to one’s dorm room or apartment, fool around, and not see each other again.). This hookup process leads to lessened intimacy and expectations for commitment in sexual encounters. Related to oral sex, findings (Halpern-Felsher et al., 2005) show that among teens and the college-aged population, oral sex is used as a substitute for vaginal-penile intercourse and as such may take the place of vaginal-penile intercourse in heterosexual hookup events. This perception of oral sex as less intimate by the college-aged population stands in contrast to perceptions of older adults, particularly older women, who view oral sex as equally intimate (or more so) to vaginal sex (Remez, 2000).

Perception Four: Oral Sex is Not Sex

The authors posit that each of the preceding sexual scripts is subsumed by an over-arching sexual script prevalent within the college-aged population: oral sex is not sex. By positioning oral sex as a less risky, less intimate sex practice that allows one to maintain his/her virginity with minimal religion-based sex guilt, the college-aged population may not identify oral sex as real sex. According to Remez (2000), peer culture socializes young adults to perceive oral sex as abstinence, allowing one to maintain and protect one’s virginity. Many factors related to contemporary social sexual scripts for oral sex support the assertion that the college-aged population does not identify oral sex as sex, including beliefs that oral sex does not impact their virgin status, is thought to be less dangerous, is less likely to lead to deterioration in the student’s reputation, and leads to less guilt than vaginal-penile penetration (Hollander, 2005).

All of the aforementioned sexual scripts contribute to the perceptions of college-aged individuals regarding oral sex. By raising awareness of the social sexual scripts, we hope to illuminate the process of meaning-making college-aged individuals attach to the act of oral sex. Further illumination of specific characteristics aligned with the over-arching social sexual script of oral sex is not sex will allow sex educators, counselors and others to target initiatives aimed at reducing risks related to oral sex in a more intentional, focused effort on individuals within the college-aged population who are most vulnerable to those risks.

Method

Sample

The data for this study were taken from a larger nonrandom sample of 781 undergraduates at a large southeastern university who answered a 100-item questionnaire (approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university) on “Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors of College Students.” Respondents completed the questionnaire anonymously (the researcher was not in the room when the questionnaire was completed and no identifying information or codes allowed the researcher to know the identity of the respondents). Listwise deletion was used to address issues of missing data and two participants were excluded from statistical calculations due to missing data.

Measures

The measure used to collect data was a 100-item survey developed by Knox and Zussman (2007): Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors of College Students. The survey was developed based on a review of the professional literature related to sexuality among undergraduates. For the purpose of this research, demographic characteristics including gender, race, age and class level and the survey domains of sexual practices, religious identification and sexual values were included in the analysis. Within the domain of sexual practices were items asking participants to respond to whether they have given or received oral sex. Items surveying participants’ perceptions of themselves as religious and their beliefs about the importance of marrying someone of their same religion were included in the domain of religious identification. The domain of sexual values included items asking participants to choose the sexual value of absolutism, relativism, or hedonism, that best described their sexual values, and items asking participants to indicate their willingness to have sex without love.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 17.0. Pearson product moment correlations and non-parametric statistics including cross-classification and Chi Squares were calculated to assess relationships among demographic characteristics and the selected domains. Following the quantitative analysis, themes within the results were explored through the lens of sexual script theory.

Results

Analysis of the data revealed several relationships that may be related to the dominant social sexual scripts affecting teen and college-aged individual’s engagement in oral sex. The majority of participants (62%) indicated their agreement with the statement that oral sex is not sex. In comparing the characteristics of those who agreed and disagreed, five statistically significant relationships emerged. Through statistical analysis of the responses, a profile of participants who asserted that oral sex is not sex emerged. Of the respondents, 76.4% were females and 25.4% were males. Racial background included 79.5% European American, 15.7% Blacks (respondent self-identified as African-American Black, African Black, or Caribbean Black), 1.9% Biracial, 1.7% Asian, and 1.3% Hispanic. The majority, (95%) of the sample identified as heterosexual, 2.9% identified as bisexual and 2% identified as homosexual. The mean age of the sample was 19 years-old.

Underclassmen-Freshmen & Sophomores

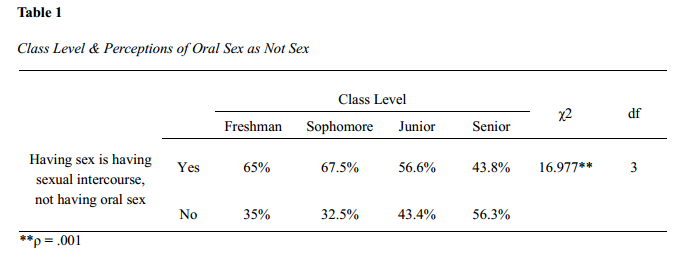

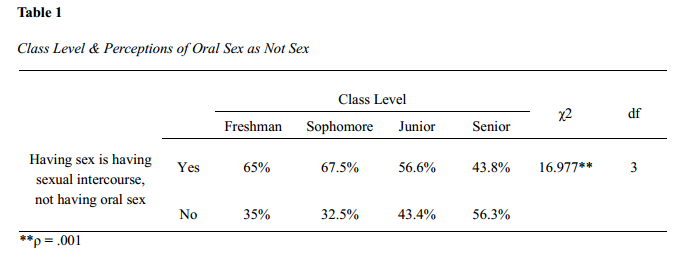

Freshmen and sophomores were the most likely to agree that oral sex does not take away one’s virginity, with the majority of freshmen and sophomores indicating their agreement that engaging in oral sex does not constitute having sex (see Table 1). Juniors and seniors were less likely than underclassmen to agree that oral sex is not having sex. Hence, there was a general pattern that the lower the class rank of the student, the more likely the student to hold the belief that he or she could have oral sex and remain a virgin.

European American

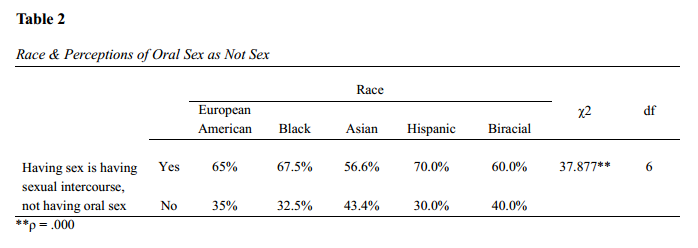

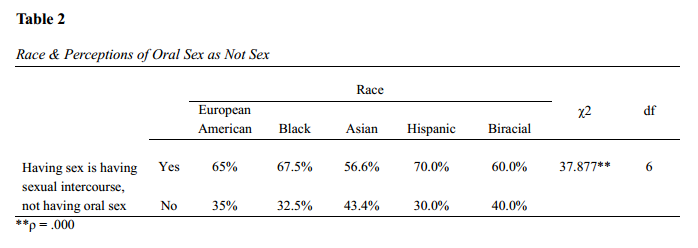

Race was significantly related to perceptions of oral sex as not being sex (see Table 2). European American undergraduates were more likely than Blacks (respondent self-identified as African-American Black, African Black, or Caribbean Black) to agree that oral sex is not sex. In this study, the limited number of Asian and Latino participants renders the data of minimal use, however 61.5% of Asian participants (N=13) and 70% of Hispanic participants (N=10) indicated that they agreed that oral sex is not sex.

Self-Identified as Religious

Students who noted that they considered themselves to be religious by indicating that they agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “I am a religious person,” were more likely to agree that oral sex is not sex than students who reported that they were not religious at all (61.3% vs. 14.3%). Participant responses revealed an inverse relationship between self-identification as “a religious person” and having never “given oral sex to a partner,” r(4) = -.121, p = .001, and having “never received oral sex,” r(4) = -.099, p = .006. An inverse relationship between perceptions of the importance of marrying someone with the same religious identification as oneself and giving and receiving oral sex respectively also was noted, r(4) = -.114, p = .001 and r(4) = -.129, p = .000. Participants who identified as religious were thus more likely to agree that oral sex is not sex and also indicated that they have engaged in oral sex.

Sexual Value

Given the alternative sexual values of relativism (“the appropriateness of intercourse depends on the nature of the relationship”), absolutism (“no intercourse before marriage”) and hedonism (“if it feels good, do it”), students who self-identified as hedonistic were more likely than those who viewed themselves as relativists and absolutists to agree that oral sex is not sex (65.8% vs. 62.9%, and 48.0%) (p < .05). Expressed another way, over 50% of absolutists compared to 34% of hedonists say the idea that one is still a virgin after having oral sex is not true. This 16% difference is striking. Participants who reported having engaged in sex without love also indicated they had engaged in both giving and receiving oral sex r(2) = -.229, p = .000, and r(2) = -.206, p =.000. These findings reflect that students who express more hedonistic perspectives are more likely to agree that oral sex is not sex and does not impact one’s status as a virgin.

Safe Sex Practices

A significant inverse relationship existed between participants who reported requiring the use of a condom before intercourse and never having given oral sex (r(4) = -.120, p = .001), and never having received oral sex (r(4) = -.092, p = .010). These findings indicate that the participants from this study who engaged in oral sex also used protective methods when engaging in intercourse outside of oral sex.

Gender

Gender was not significantly related to participant perceptions of oral sex as not being real sex and sex only referring to sexual intercourse. Gender was, however, significantly related to having never given oral sex χ2 (1, N = 781) = 3.843, ρ = .05) and having never received oral sex χ2 (1, N = 781) = 4.016, =.045), with males indicating in greater levels than females that they have received oral sex, and also that they have never given oral sex. These findings indicate that the gendered experiences of giving and/or receiving oral sex are important to explore, because it appears from the participant responses in this study that there may be gender differences in the likelihood of an individual giving or receiving oral sex.

Discussion

This research sought to gain information about college-aged individuals most likely to agree that oral sex is not sex and to share information about individuals within this population’s perceptions about engagement in oral sex. The results allowed for the development of a demographic profile of participants who agreed that oral sex is not sex. In considering the results and demographic profile of participants who agreed that oral sex is not sex, relationships between sexual scripts and participant responses emerged.

The demographic profile which emerged indicated that participants most likely to agree that oral sex is not sex were underclassmen (freshmen and sophomores), European American and self-identified as religious. Inferences from the results were made through a parallel exploration of sexual scripts and the quantitative data from the studied domains and the demographic profile.

Oral Sex is Safe

The negative relationship that emerged between requiring the use of contraception before intercourse and engagement in oral sex may have many meanings. From the limited information provided through this analysis concerning safe sex practices and perceptions of oral sex, few inferences regarding the relationship between these issues can be made. Although the literature would suggest that college-aged students believe oral sex to be safe, this study did not provide enough information to definitively make this inference. However, the negative relationship between participants who required the use of contraception and previous experience with oral sex indicated that participants with previous experience giving and receiving oral sex were more likely to require the use of a condom before intercourse than were participants with no prior experience giving and receiving oral sex. From this finding, it could be inferred that participants who engage in oral sex are more likely to engage in safe sex practices, aligning congruently with the social sexual script posited in the professional literature of the perceptions that oral sex is safe. However, there could be many contributing factors to this relationship and further study is necessary to make clear inferences.

Oral Sex Potentially Mitigates Religiosity and Sex Guilt Tension

Supporting the sexual script that oral sex mitigates sex guilt because it is not real sex, the findings of this study discerned a strong relationship between religious identification and engagement in oral sex. Participants who reported strong self-identification as religious also reported having engaged in giving and receiving oral sex. Additionally, a significant relationship existed between participant responses to “I am a religious person” and “oral sex is not sex” χ2 (4, N = 781) = 10.310, p = .036). Other studies have shown that teens and young adults engage in oral sex because they view it as something that they do before they are ready to have sex (Remez, 2000). This of course implies that the only thing that counts as sex is vaginal-penile intercourse, and that this type of sexual activity breaks the threshold of virgin status.

These findings are not enough to conclude fully that oral sex is used to mitigate sex guilt-religiosity tension. However, the findings do suggest that college students who view themselves as religious also engage in oral sex, indicating that oral sex may be viewed as less likely to violate religious mores related to sexual engagement, since it is not viewed as real sex.

Oral Sex Requires Less Commitment