Population-Based Mental Health Facilitation (MHF): A Grassroots Strategy That Works

J. Scott Hinkle

Abstract: The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that at least 450 million people worldwide live with unmet mental health problems. Additionally, one in four people will experience psychological distress and meet criteria for a diagnosable mental health disorder at some point in their lives. This data speaks to the need for accessible, effective and equitable global mental health care. Available mental health resources are inequitably distributed, with low- to middle-income countries showing significantly fewer mental health human resources than high-income countries. The need to proactively address this care-need gap has been identified by WHO and various national organizations, including NBCC International (NBCC-I). NBCC-I’s Mental Health Facilitator (MHF) program addresses the global need for community-based mental health training that can be adapted to reflect the social, cultural, economic and political climate of any population, nation or region.

Keywords: global, mental health, international, mental health facilitator, MHF, population, community, WHO

Pages 1–18

Developing and promoting mental health services at the grassroots level while also maintaining a global perspective is, to say the least, an overwhelming task. The National Board for Certified Counselors’ International division (NBCC-I) has responded to this task in two deliberate steps. Initially, NBCC-I collaborated with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse to establish the global Mental Health Facilitator (MHF) training program. The MHF program addresses the international need for population-based mental health training that can be adapted to reflect the social, cultural, economic and political realities of any country or region. Once the program was effectively addressed by WHO and NBCC-I as a viable strategy to reduce mental health issues on a global basis, NBCC-I independently developed a curriculum and implementation method that has begun to make a promising global impact (Hinkle, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2010a, 2010b, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c, 2013; Hinkle & Henderson, 2007; Hinkle & Schweiger, 2012; Schweiger & Hinkle, 2013).

For years the global burden of mental disorders on individuals, families, communities and health services has been considerably underestimated (Chisholm et al., 2000; Murray & López, 1996a, 1996b; Ustün & Sartorius, 1995). Resources for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders have been slow in development, insufficient, constrained, fragmented, inequitably distributed, and ineffectively implemented (Becker & Kleinman, 2013; Chen et al., 2004; Gulbenkian Global Mental Health Platform [GGMHP], 2013a; Hinkle & Saxena, 2006). While mental and neurological disorders comprise only 1% of deaths worldwide, they account for 8–28% of the disease burden (GGMHP, 2013a; Murray et al., 2012; Prince et al., 2007; WHO, 2004a), with the majority of these disorders occurring in low- to middle-income countries.

Mental Health: An International Problem

Most mental disorders are highly prevalent in all societies, remain largely undetected and untreated, and result in a substantial burden to families and communities. Although many mental disorders can be mitigated or are avoidable, they continue to be overlooked by the international community and produce significant economic and social hardship. Moreover, in all countries there is an enormous gap between the prevalence of mental disorders and the number of people receiving care (Becker & Kleinman, 2013; Saraceno et al., 2007; Weissman et al., 1994; Weissman et al., 1996; Weissman et al., 1997; WHO, 2010a, 2010b). In less-developed countries, more than 75% of persons with serious mental disorders do not receive treatment (Demyttenaere et al., 2004). Unfortunately, psychiatry’s best efforts at training physicians to provide mental health care within the global context are simply too small for such a large, global problem (Furtos, 2013; Hinkle, 2009, 2010b, 2012b, 2012c; Patel, 2013). The focus has been too long on medicine and not on local communities (Patel, 2013). In fact, every person’s health care is local (Unützer, 2013). The major issue with the current provision of care is, therefore, the limited size and training of the community health care workforce (Becker & Kleinman, 2013).

Globally, one in four people will experience psychological distress and meet criteria for a diagnosable mental disorder at some point in their lives (WHO, 2005). This ominous data speaks to the need for accessible, effective and socially equitable mental health care (Hinkle & Saxena, 2006). WHO estimates that more than 450 million people worldwide live with mental health problems; these numbers are no doubt bleak. More specifically, WHO estimates that globally more than 154 million people suffer from depression, 100 million are affected by alcohol use disorders, 25 million have schizophrenia, 15 million experience drug abuse, and nearly one million people die each year by suicide (Saraceno et al., 2007). Depending on the source, unipolar depression has been estimated to be in the top four causes of loss of disability-adjusted life years across the six socially diverse continents (Murray & López, 1996a, 1996b; Vos et al., 2012).

Furthermore, it has been estimated that as many as 25% of all primary care consultations have a mental health component (Goldberg & Huxley, 1992; Warner & Ford, 1998; WHO, 2006a). Mental disorders are related to a range of problems, from poverty, marginalization, and social disadvantage, to relationship issues such as divorce, physical conditions such as heart disease, reductions in economic productivity, and interruption of child and adolescent educational processes (see Alonso, Chatterji, He, & Kessler, 2013; Breslau et al., 2013). At the developmental level, at least 10% of children are considered to have mental health problems, but pediatricians and general medical practitioners are not typically equipped to provide effective treatment (Craft, 2005). With mental disorders contributing to an average of 20% of disabilities at the societal level, the evidence is clear that these disorders pose a major challenge to global health (Alonso, Chatterji, et al., 2013; Alonso, Petukhova, et al., 2013). Moreover, the associated economic burden exceeds that of the top four non-communicable diseases (i.e., diabetes, cardiovascular, respiratory and cancer; Bloom et al., 2011).

Unfortunately, most international mental health systems are dominated by custodial psychiatric hospitals that deplete resources for treatments with little efficacy (WHO, 2005). In contrast, governments and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) should scale up services for community mental health with programs that reflect credible evidence of effectiveness (see Patel, 2013; Patel, Araya, et al., 2007). Murthy (2006) has indicated that there is no global community mental health blueprint to achieve universal mental health access, and that effective community workforce strategies need to be matched to each country’s unique situation. It is an ecological fallacy to try to understand people and mental health issues outside the environments in which they exist (Galea, 2013). Thus, a radical shift is urgently needed in the way mental disorders are managed, and this clearly includes community-based care that can be effectively implemented via non-health as well as health sectors (GGMHP, 2013a, 2013b; Hinkle, 2012b).

Global Community Mental Health

Serious mental disorders are generally associated with substantial role disability within the community. About 35–50% of mental health cases in developed countries and approximately 75–85% in less-developed countries have received no treatment in the 12 months preceding a clinical interview. Due to the high prevalence of mild and sub-threshold cases, the number of untreated cases is estimated to be even larger. These milder cases, which can be found in communities all over the world, require careful consideration because they are prone to progress to serious mental disorders (WHO, 2010a, 2010b; WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium, 2004).

It is important to note that in most low- to middle-income countries, community workers are often the people’s first line of contact with the health care system (Anand & Bärnighausen, 2004; Hongoro & McPake, 2004). However, there is a long history of issues with the sustainability of community programs (Walt, 1988), and the lack of community service providers with the necessary competencies to address needs remains the most significant barrier to the provision of mental health services. Although human resources are the crucial core of health systems, they have been a neglected developmental component (Hongoro & McPake, 2004), particularly in the field of mental health. WHO’s “Mental Health Atlas” (2005) specifies a critical global shortage of mental health professionals (e.g., psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, psychologists, social workers, neurologists). Similarly, an informal international survey of clinical mental health, school, and career and work counselors by NBCC-I indicated that the professional counselor workforce has yet to be adequately identified on a global scale (Hinkle, 2010b). Moreover, extant mental health services are inequitably distributed; lower-income countries, where behavioral risk factors tend to cluster among people of lower socioeconomic status, have significantly fewer mental health human resources than higher-income countries (Coups, Gaba, & Orleans, 2004; WHO, 2005; WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium, 2004).

In low- to middle-income countries, human resources are clearly limited, and the quality and productivity of the existing workforce is often challenged. Investment in human resources for community mental health care is insufficient in absolute terms as well as in distribution (Hongoro & McPake, 2004). For instance, the global average for physicians is 170 per 100,000 people, but in Nepal and Papua New Guinea there have been as few as five doctors for this ratio (WHO, 2004a). In 2003, approximately 36% of doctors’ posts and 18% of nurses’ posts were unfilled around the world (Bach, 2004). Moreover, general practitioners are not typically adept at providing mental health care, including detection, referral and management of mental disorders (Chisholm et al., 2000). Therefore, partnerships between formal primary and informal community health care systems need to be more prevalent, effective and integrated.

Two facets for integrating mental health into primary care are (a) financial and human resources and (b) collaboration with non-health sectors. NGOs, community workers and volunteers can play a significant role in supporting formal primary care systems for mental health. For example, village health workers in Argentina, India and the Islamic Republic of Iran have been trained to identify and refer people for medical assistance. Even countries that have adequate services, like Australia, use local informal services to support mental health patients (see WHO, 2006b). Because psychiatric hospital beds are extremely limited, the demand for mental health services within communities becomes even more critical (Forchuk, Martin, Chan, & Jensen, 2005). Furthermore, early detection and treatment of mental disorders and co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems not only decreases the chance of lower physical health later in life, but also associated costly hospitalizations (Alonso, Chatterji, et al., 2013; Alonso, Petukhova, et al., 2013; Scott et al., 2013).

An urgent, radical change in the way mental disorders are managed and monitored—one that moves away from lengthy institutional hospitalizations and toward population-based mental health care in the community—is needed (GGMHP, 2013a, 2013b; Hinkle, 2009). The need to proactively address this care-need gap from a praxis, or practical, rather than a theoretical approach has been repeatedly identified by WHO and various national and international organizations, including NBCC-I (Hinkle & Schweiger, 2012). Communities in developing countries have historically lacked opportunities for mental health training, skill development, and capacity building (Abarquez & Murshed, 2004); however, long years of training are not necessary for learning how to provide fundamental help for people who are emotionally distressed.

Volunteer community workers are a large untapped community resource of potential service providers for people suffering from problems associated with mental health (Hoff, Hallisey, & Hoff, 2009). Chan (2010) has reported that “there is a widely shared but mistaken idea that improvements in mental health require sophisticated and expensive technologies and highly specialized staff. The reality is that most of the mental, neurological and substance use conditions that result in high morbidity and mortality can be managed by non-specialist health-care providers” (p. iii). The research has substantiated that it is feasible to deliver psychosocial-type interventions in non-specialized health care settings (WHO, 2010a, 2010b). Enhancing basic community mental health services, both informally and formally, is a viable way to assist the never-served. The MHF program is part of a grassroots implementation trend that has already begun in communities around the globe (e.g., Canada, Europe, Africa, Asia, United States; see Hinkle, 2007, 2013; Hoff, 1993; Hoff et al., 2009; Marks & Scott, 1990; McKee, Ferlie, & Hyde, 2008; Mosher & Burti, 1994; Patel, 2013; Rachlis & Kushner, 1994).

A Brief Review of Grassroots Community Mental Health Approaches

Unfortunately, governmental psychiatric hospitals have a long history of human rights violations and poor clinical outcomes (Hinkle, 2010b). They also are costly and consume a disproportionate amount of mental health care monies. In contrast, informal community caregivers are not generally part of the formal health care system; examples include traditional healers, professionals such as teachers, police and various community workers, NGOs, consumer and family associations, as well as laypeople. Informal care is typically accessible because it is an integral part of the community. However informal, this care should not replace the core of formal mental health service provision (Saraceno et al., 2007; WHO, 2010a, 2010b), but serve as a grassroots, adjunctive care system.

For example, beginning as early as 1963, the work of Rioch et al. portrayed community paraprofessionals serving as in- and out-patient “therapists.” Similarly, as far back as 50 years, Albee (1967) reported that the dearth of manpower in mental health services could be lessened by the use of paraprofessionals who could arrange for neighborhood outreach and basic psychiatric evaluations (Hines, 1970).

Likewise, in 1969 Vidaver suggested the development of mental health technicians with generalist skills for lateral and vertical mental health employment mobility. Vidaver (1969) further commented that community colleges were able to train local community helpers for a variety of informal roles in mental health services without years of higher education. Interviewing (i.e., communication), consultation, and community liaison techniques (i.e., referral) were depicted by Vidaver as important general skills for community helpers. One year later, Lynch and Gardner (1970) developed a training program with the goal of training laypeople to be “helpers in a psychiatric setting” (p. 1476), emphasizing communication skills training with a focus on the “front line of operation” (p. 1475) provided by paraprofessionals and professionals providing backup services.

Also in 1970, the U.S. military addressed mental health manpower shortages by increasing the use of paraprofessional specialists who were taught entry-level skills to help soldiers in need (Nolan & Cooke, 1970). Training included conducting interviews, collecting historical, situational and observational data, and developing referral skills to connect the soldier with professional mental health resources. Identifying common mental health problems and relating to problems in a realistic way were included in the training. Program evaluations indicated that trainees “quickly and confidently transpose their course-acquired skills to the job situation” (Nolan & Cooke, 1970, p. 79).

More recently, basic psychological first aid programs have been effective in Bangladesh, where psychosocial support is used in emergency situations (Kabir, 2011). As well, nurses and health care staff have been trained as mental health facilitators in the United Kingdom to recognize depression, anxiety, stress, drug and alcohol problems, grief reactions, and domestic violence; make referrals; and provide support and aftercare. These nurses also assist people with co-occurring disorders and provid mental health promotion in the schools. Furthermore, the nursing profession in the United Kingdom has noted that community mental health care is a particular problem area, resulting in the development of the mental health assistant practitioner as a creative practice strategy to reduce the costs of services as well as improve multi-professional communication based on local needs (Warner & Ford, 1998; Warne & McAndrew, 2004).

Although implementing such grassroots community mental health programs is not easy, global health care organizations have demonstrated greater need to develop innovative uses of informal mental health assistants and facilitators to establish community mental health services (Warne & McAndrew, 2004). In the long run, if the gap in mental health services is sufficiently closed, it must include the use of non-specialists to deliver care (Eaton, 2013; Eaton et al., 2011; Hinkle, 2006, 2009). Such non-specialized workers will have received novel training in identifying mental stress, distress and disorders; providing fundamental care; monitoring strategies; and making appropriate referrals (see Becker & Kleinman, 2013; Hinkle & Schweiger, 2012; Hinkle, Kutcher, & Chehil, 2006; Jorm, 2012; Saraceno et al., 2007).

The Mental Health Facilitator Training Program

Existing data speaks loudly to the need for accessible, effective and equitable global mental health care. However, a common barrier to mental health care is a lack of providers who have the necessary competencies to address basic community psychosocial needs. This barrier has been clearly identified by WHO and various national and international organizations, including NBCC-I (Eaton, 2013; Hinkle, 2006, 2009, 2012c; Hinkle & Saxena, 2006; Patel, 2013; WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium, 2004; WHO, 2005, 2010a, 2010b).

General MHF Background Information and Rationale

In 2005, officers from NBCC-I met with the director of the WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse to discuss the challenges of international mental health care. As a result of these meetings, WHO selected 32 international mental health professionals to evaluate NBCC-I’s proposed MHF program, with almost 100% supporting its development. Subsequently, the curriculum and master training guide were completed by NBCC-I in 2007. Drafts of the curriculum and proposed teaching methods were piloted on two occasions in Mexico City with mental health professionals from Europe, the Caribbean, Africa and the United States. Additional subject matter experts facilitating pilot development included mental health professionals from Malaysia, Canada, Trinidad, St. Lucia, Turkey, India, Mexico, Botswana, Romania and Venezuela.

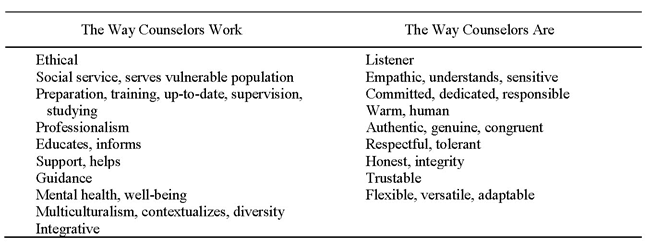

The resulting MHF training program draws on a variety of competencies derived from related disciplines, including but not limited to psychiatry, psychology, social work, psychiatric nursing, and counseling. Its eclectic programming and international composition allowed for a flexible training model with expertise drawn from global practices. Because MHF training is transdisciplinary, traditional professional helping silos are not reinforced; skills and competencies are linked instead to population-based mental health needs rather than professional ideologies. Thus, individuals with MHF training (MHFs) can effectively identify and meet community mental health needs in a standardized manner, regardless of where these needs are manifested and how they are interpreted. Mental health and the process of facilitating it is based on developing community relationships that promote a state of well-being, enabling individuals to realize their abilities, cope with the normal and less-than-normal stresses of life, work productively, and make a contribution to their communities.

The MHF training program was first taught in Lilongwe, Malawi in 2008 and has since been taught approximately 108 times by 435 trainers, including 181 master trainers in 20 countries. The MHF program recently expanded to provide mental health assistance in more established countries, as manifested in the program’s current popularity in the United States (Schweiger & Hinkle, 2013). This expansion also marks the completion of an educators’ edition of the MHF curriculum for use in schools with a focus on students, teachers and schooling.

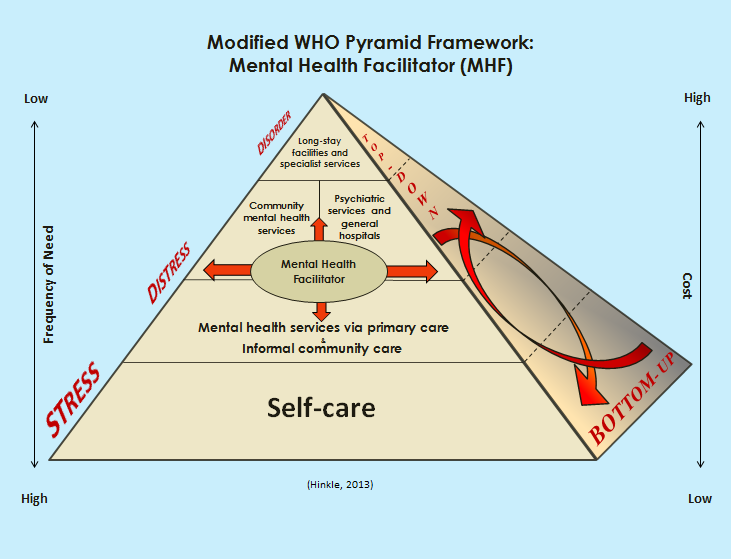

To date, the MHF training program has been implemented globally to enhance mental health care at various levels. At the formal, primary health care level, general medical practitioners provide acute and long-term treatment to individuals with a variety of mental disorders, supplemented by the efforts of individuals with MHF training. MHFs also augment specialized services by functioning within a mental health care team to provide support, targeted assistance, referral and follow-up monitoring (Paredes, Schweiger, Hinkle, Kutcher, & Chehil, 2008). Likewise, informal community care is characterized by community members without formal mental health education or training providing much-needed services. At this level, nonclinical forms of mental health care such as psychological support or strategic problem solving by community leaders, family groups, and local elders (including indigenous healers) are emphasized. MHF training has been used to bridge the gap between formal and informal mental health care where MHFs work within both systems and do so simultaneously (Hinkle, Kutcher, & Chehil, 2006). With due respect to horizontal and vertical considerations, MHFs have augmented traditional, formal inpatient services by working with mental health teams to provide family support and education, monitor follow-ups, and provide practical “in the trenches” assistance (see Figure 1). This is where informal care, including self-care, becomes critical (Murthy, 2006).

Contextualizing the MHF Program

Most importantly, it is ill-advised to attempt to understand people outside their environments; people must be considered within the characteristics of their respective populations (Galea, 2013). The MHF program is designed to be flexible so local experts can modify components of the training to reflect the realities of their situation. Local stakeholders then identify and include specific competencies in their MHF trainings. As a consequence, consumers and policymakers ensure that MHF trainings provide culturally relevant services to the local population. Furthermore, the MHF training curriculum was conceived as a dynamic document and is revised once each year based on input from local institutions and individuals who provide MHF training. This contextual, organic approach grounds the MHF program in the principle that mental health care is a combination of both universally applicable and context-specific knowledge and skills (Furtos, 2013; Hinkle, 2012a; Paredes et al., 2008). The program consists of integrated knowledge ranging from basic mental health information and promotion to specific, local, culturally relevant helping strategies. The global MHF program

Figure 1. Modified WHO Pyramid Framework: MHF (Hinkle, 2013b)

provides equitable access to quality first-contact interventions, including but not limited to mental health advocacy, helping skills, and monitoring and referral, all of which respect human dignity and rights, and meet local population needs.

Individuals receiving MHF training represent a broad cross section of the community. Diverse trainee backgrounds increase the possibility of addressing the various gaps in local mental health care, which helps local policy makers, service providers, NGOs and communities meet mental health needs without costly infrastructural investments. Moreover, contextualized MHF training facilitates further development and delivery of community-based care consistent with WHO recommendations for addressing the gap in global mental health services.

Bottom-Up vs. Top-Down Community Strategies

It is commonly known that top-down approaches across public services generally have limited success. Conversely, long-term strategies that enhance the successful implementation of public mental health services are best when they are centrally facilitated from a locally directed, bottom-up approach (Rock, Combrinck, & Groves, 2001). From both a service delivery and administrative perspective, a bottom-up strategy has its advantages. One obvious benefit is that it requires local stakeholders to articulate objective and verifiable goals that use a “common currency” (p. 44) or terminology (Rock et al., 2001).

Similarly, MHFs have the advantage of serving as community leaders developing “upstream” versus “downstream” care, as well as providing important links to professional mental health care (Hinkle, Kutcher, & Chehil, 2006; Hoff et al., 2009; McKinlay, 1990). MHFs working in communities apply primary prevention principles by anticipating mental health services for people who may be vulnerable. For instance, MHFs in Bhutan provide drop-in peer assistance for young people challenged by rapid changes in their society. When MHF services are available at the secondary prevention level, people with mental health issues can often avoid disruptive and costly hospitalization. MHFs can assist with reducing long-term disabling effects among people recovering from a mental disorder by applying tertiary prevention measures from the bottom up (Hinkle & Saxena, 2006; Hoff et al., 2009). Furthermore, governmental direction from the top needs to intersect with community efforts from the bottom (Isaac, 2013; see Figure 1); and once programs are vetted from the top, they need to be diverted to bottom-up management (Eaton, 2013).

Although community mental health programs may achieve local success, few have been systematically scaled up to serve the needs of national populations. Despite the array of treatments for mental health, little evidence exists regarding their feasibility and effectiveness when integrated into routine care settings among low- and middle-income countries. Even though bottom-up approaches offer advantages, they also require outcome measurements, something that mental health workers have found traditionally burdensome (Rock et al., 2001). For example, evidence-based mental health interventions for people exposed to conflict and other disasters are weak, especially for strategies implemented in the midst of emergencies (Patel, Araya, et al., 2007). Only a small fraction of the clinical research trials regarding mental health treatment have been administered in low-income countries, resulting in a dearth of knowledge about treatment effectiveness in poor, culturally diverse settings (Becker & Kleinmen, 2013). Consequently, the MHF process is currently undergoing an evaluation in two diverse countries on two separate continents to seek evidence for the effectiveness of this training program. This is a critical step in the program’s continued development, because empirical evaluation of lay health workers’ implementation of community mental health services in low- and middle-income countries has been historically insufficient (Lewin et al., 2005). However, if the global strategy is only to collect more information and add to data resources, there will continue to be a gap in human resources.

As planned, individuals seeking MHF training have represented a broad cross section of local society, ranging from school teachers and principals to business owners, clergy and neighborhood workers. MHF volunteers are also police officers, neighborhood workers, community leaders, NGO employees, elders and indigenous healers. In fact, such healers in Malawi, Africa have learned to apply their first-contact mental health skills to identify, assess, support and refer people in need of acute mental health care through the MHF program. This diversity of trainee backgrounds at the grassroots level increases possibilities for addressing as many gaps as possible in community mental health care. Indeed, grassroots efforts emanate from the ground level (Eaton, 2013; Hinkle, 2010b, 2012a; Hinkle & Schweiger, 2012; Schweiger & Hinkle, 2013).

The Global MHF Partnership

Partnerships among NGOs, governments, agencies and academia can make a difference in the mental health workforce capacity by integrating global expertise with local knowledge (Fricchione, Borba, Alem, Shibre, Carney, & Henderson, 2012; WHO, 2009). As countries recognize the dearth of community health services and attempt to develop fundamental services with a mental health focus, the MHF training program is appealing because of its emphasis at the “street” or “trenches” level (Hinkle, 2012a). This is a critical component of the MHF training program since local stakeholders always have more at stake in risk reduction and capacity building than agencies outside the local neighborhood, village or barrio (Abarquez & Murshed, 2004). For example, MHF training has benefited the people of Mexico City, who have had historically limited access to mental health services (Suck, Kleinberg, & Hinkle, 2013a).

The initial stage of the MHF training process identifies local partners who have the willingness and ability to increase local mental health care capacity. NBCC-I negotiates MHF training with partners such as educational institutions, government agencies, NGOs, private companies or other entities capable of managing a training. An ideal global partner has the capacity and ability to maintain the MHF program and promote continuing mental health education. NBCC-I and respective training partners identify master trainers who can train more trainers, ensuring a multiplier effect (NBCC-I, 2013). In countries where English is not a primary or spoken language, it is necessary to translate and adapt the MHF curriculum and materials. Thus far, MHF partnerships have resulted in the curriculum being translated into 10 languages:Arabic, Bahasa Malaysian, Bhutanese [Dzongka], Chinese, German, Greek, Japanese, Portuguese, Spanish and Swahili.

The MHF Curriculum: General Features

NBCC-I has responded to the care-need gap challenge, and developed and standardized the MHF curriculum drawing on a variety of competencies derived from related mental health disciplines within a cultural context. General, nonclinical, first-responder forms of community mental health care such as basic assessment, social support and referral are included in the MHF curriculum. Similar models that include assessment, advising, agreement on goals, interventions, support and follow-up have been used successfully in mental health care (Fiore et al., 2000; Hinkle, 2012b, 2012c; Whitlock, Orleans, Pender, & Allan, 2002). Currently there are MHFs on five continents, with new trainings being coordinated almost weekly. In developing the curriculum, an eclectic group of professional contributors allowed for a flexible training model with expertise drawn from various international practices. The training consists of 30 hours that can be taught on consecutive days, or divided into its 20 modules and taught over several weeks, depending on the needs of the local community (Hinkle & Henderson, 2007). As local stakeholders are identified and trained using the MHF curriculum, they become the foundation on which to build community mental health care.

The MHF training includes a certificate of completion for anyone successfully completing the program, and additional certificates of completion for trainers and master trainers. Trainers are required to hold a bachelor’s degree or its equivalent, and master trainers must have a master’s degree or its equivalent in a mental health–related discipline. One affirming by-product of the training is the identification of individuals who desire more training and education in mental health services. For example, the MHF program in Bhutan has led to specified substance abuse training in several communities, as well as two students seeking graduate studies in counseling in the United States.

Specific Features of the MHF Curriculum

The MHF curriculum is based on the universality of mental stress, distress and disorders (Desjarlais, Eisenberg, Good, & Kleinman, 1995; Hinkle & Henderson, 2007). MHF training includes numerous topics such as basic helping skills, coping with stress, and community mental health services. The program consists of fundamental, integrated mental health knowledge and skills ranging from community advocacy and commitment, to specified interventions such as suicide mitigation. Also included in the curriculum are segments on working with integrity and not providing services outside the limits of training and experience (Hinkle, 2010a; Reyes & Elhai, 2004). In general, MHFs are taught that negative and unhealthy assumptions about life and living contribute to additional mental and emotional stress (Browne & Winkelman, 2007; Feiring, Taska, & Chen, 2002; Sonne, 2012).

More specifically, the curriculum begins with a section on the benefits of investing in mental health, cost-effective interventions, impacts of mental disorders on families, barriers to mental health care, confidentiality and privacy, and the goals of the MHF program. Understanding perspectives regarding human feelings, effective nonverbal and verbal communication, and using questions effectively in the helping process also are covered in the curriculum, as well as how to assess problems, identify mental health issues, and provide support (Hinkle & Henderson, 2007). Making effective referrals is a crucial segment of the curriculum because this skill also serves the purpose of steering people to physicians for co-occurring physical disorders such as diabetes, heart disease and chronic pain (Gureje, 2013).

MHF trainees also learn how to effectively end a helping relationship—an essential skill taught to mental health workers for the past 40 years (Hines, 1970; Hinkle & Henderson, 2007). MHFs learn that the helping process involves joining with the person seeking assistance, identifying specific concerns, assessing the level of difficulty, surveying the possibilities, solving problems and making choices, and referring to more formal care where appropriate. This is accomplished within a simple framework emphasizing personal strengths and mitigation of significant stress.

Following the basic helping skills section of the curriculum, which emphasizes the age-old but important phenomena of human development and diversity, trainees concentrate on the abilities, needs and preferences that all people possess and how these are integrated in various cultures (Elder & Shanahan, 2007; Huston & Bentley, 2010; Lerner, 2007). A section on understanding various types of encountered problems introduces trainees to the concept of a balanced, less balanced, little balanced, or off balance mental health continuum, alongside how to solve problems and set goals with people experiencing difficulty coping with life (Hinkle & Henderson, 2007). Similarly, trainees learn about stress, distress and basic mental disorders including anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and mania, psychosis and schizophrenia, substance abuse and dependence, delirium and dementia, mental retardation (intellectual disability), chronic pain, and epilepsy. Child reactions to trauma (van Wesel, Boeije, Alisic, & Drost, 2012) and child maltreatment (Wekerle, 2011) also are covered in the MHF curriculum, which emphasizes helping children and adolescents in the least restrictive environment and as close to their communities as possible (Hinkle & Henderson, 2007).

Preventing suicide and effectively dealing with an actual suicide are two topics of relevance covered in MHF training. Suicide is a leading cause of death in low- and middle-income countries, especially among young people (WHO, 2006a). Self-poisoning using pesticides is common, with estimates of 300,000 of these deaths a year in the Asia-Pacific region alone (Patel, Araya, et al., 2007), validating the need for suicide’s inclusion in the curriculum.

In the 1990s, humanitarian organizations began to recognize the increased need for psychosocial support after various types of disasters (Barron, 2004; Wells, 2006). Disasters result in tremendous loss of property, resources and life. In addition, political, economic and social disruptions are common consequences that have mental health–related implications. Therefore, information about assisting individuals and families in the aftermath of disasters is included in the MHF curriculum (Hinkle & Henderson, 2007; Wells, 2006). The MHF training also emphasizes ways to assist with situations involving domestic violence, refugees, migrants and victims of human trafficking and war, as well as other unfortunate forms of crisis.

Stress-related disorders, as depicted in the MHF curriculum, go largely untreated in many areas of the world, especially when crises and disasters strike. It is all too often the scenario that an earthquake, typhoon, hurricane or human-made crisis has occurred, and limited or no mental health care services are available following the event. Attempts to provide assistance in the aftermath of these disasters have come from governmental responses, NGOs, and community and religious organizations, but it is important to note that even professional mental health workers receive cursory instruction in disaster interventions (Hinkle, 2010a). The need for greater mental health response services is apparent; MHFs from Lebanon to Liberia have assisted communities following civil war and refugee crises, and MHFs in China have assisted in the aftermath of a major earthquake using the basic mental health training they received from the MHF curriculum.

Regardless of their genesis, many mental health–related concerns are largely dependent on problem-solving abilities, a focus on cultural values regarding mental health functioning, and social and economic support (Hinkle et al., 2006; Hoff et al., 2009), all of which are addressed in the MHF curriculum. Studies from stress-related literature suggest that a fundamental problem-solving coping approach is generally associated with positive outcomes (Benight, 2012; Taylor & Stanton, 2007), whereas avoidant-related coping is associated with negative outcomes (Littleton, Horsley, John, & Nelson, 2007); thus the emphasis on problem-solving skills in the MHF curriculum.

Lastly, consulting with helping professionals during mental health emergencies and recognizing the importance of self-care when working in crisis situations also are part of the MHF curriculum. The curriculum culminates with the all-important local contextualizing of what trainees have learned during their MHF training (Hinkle & Henderson, 2007; Sonne, 2012).

Potential Limitations

Unfortunately, organizational, cultural, and professional concerns coinciding with the often ambiguous role and purpose of mental health care can beset the expanding use of community helpers and may have an unintended impact on role identities among the general health workforce (see Warne & McAndrew, 2004). Possibly complicating matters further, the MHF program is a set of concepts and skills, not a professional designation. One concern associated with the MHF program is therefore its potential for propagating invisibly and resulting in new worker roles that cause confusion within standardized health care. Although “the potential of the fully visible and verbal paraprofessional to effect changes in the delivery of psychiatric care is vast” (Lynch & Gardner, 1970, p. 1478), it could become problematic in some locations if MHFs are not strategically blended into community health services. It has long been known that without a viable, transparent strategy, the utilization of MHFs could make for strained relationships in places where the program is not fully vetted. Furthermore, organizational structures that are not flexible or willing to pursue institutional change and innovation may have more difficulty accepting the MHF program (Hinkle, 2012b). Therefore, local and global political and networking skills are critical to the MHF program’s sustainability.

Working conditions and available remuneration for community programs and workers raises several questions that will need to be addressed at some point (Hongoro & McPake, 2004). For instance, could municipalities and governments make MHF a job classification with an upwardly mobile career ladder within existing mental health services? Where financial incentives are not possible, could ad hoc benefits such as access to more training be feasible? How will MHF trainings be sustained in communities over time? Will volunteers be able to conduct the MHF program with limited resources? Additionally, for the program to be sustainable, trainers must have incentives to train more MHFs as community service providers. Without trainers teaching more programs, it is likely that a multiplier strategy will have limited success.

Another potential criticism of the MHF program is that the quality and safety of care could be compromised using community workers. However, the more critical point remains that providing basic assistance is much safer and salubrious than providing no care at all (see Hongoro & McPake, 2004). As in mental health nursing, supervision and mentoring of MHFs will at some point become an issue (Eaton, 2013; Warne & McAndrew, 2004). Furthermore, supportive supervisory relationships are important because supervisors are perceived as role models (Thigpen, 1979) in addition to providing needed guidance for informal community mental health workers.

Future MHF training strategies will need to incorporate continuing community educational development in mental health. Twinning or pairing universities in developing countries with those in less-developed countries is one method for increasing continuing education efforts. Distance learning can be an effective delivery method as well. However, twinning and distance education are all too often not core interests in developing nations, which tend to lack expertise in managing such partnerships (see Fricchione et al., 2012; Hongoro & McPake, 2004).

Conclusion

For the MHF program to proliferate, it will take not only training, education and implementation in often less than optimal working conditions, but also savvy negotiation of often poorly managed political systems that experience some level of corruption and inability to impact the universal stigma that plagues mental illness. To manage the program effectively, the global MHF strategy will need to continue to be accessible from the bottom up and maintain an uncomplicated implementation process. Patel (2013) has advocated that community mental health must be simplified, available where people live, locally contextualized, affordable and sustainable. The MHF program has met all of these criteria with the exception of sustainability, and only more time will tell the level of program longevity.

Advances in alleviating the costs of mental disorders have been limited and slow in coming (Becker & Kleinman, 2013). It is abundantly obvious that the challenges of unmet mental health needs negatively impact societies and economies around the globe. Becker and Kleinman (2013) have recently reported that “according to virtually any metric, grave concern is warranted with regard to the high global burden of mental disorders, the associated intransigent, unmet needs, and the unacceptable toll of human suffering” (p. 71). The burden of mental disorders at the social and individual level is comparable to that of physical disorders and substantially impacts the capital of all countries. Social factors are critical to the promotion and prevention of mental health (GGMHP, 2013b). Furthermore, children exposed to adult mental health disorders among their caregivers, as well as emotional psychological trauma, are predicted to have higher risks of mental disorders in adulthood, further compounding the problem (Chatterji, He, & Alonso, 2013; Patel, Araya, et al., 2007; Patel, Flisher, Hetrick, & McGorry, 2007). WHO (2010a, 2010b) has recommended bridging the care-need gap; however, this will not occur while services are embedded in professional silos rather than being population-centered (Chatterji & Alonso, 2013; Hinkle, 2012c).

The need to address workforce issues affects the quality and quantity of international mental health services (Warne & McAndrew, 2004); there is a clear link between human resources and population health. Community and family caregiving for mental disorders, often uncompensated, has a “tremendous value from a public health perspective by way of offsetting the costs and services of expensive and critically shorthanded healthcare professionals” (Viana et al., 2013, p. 134). At the American Psychiatric Association’s annual convention in 2013, Galea reported that the social aspects of mental health are not a sideshow, but at the very core and not being paid attention to. Unfortunately, not even the laudable efforts of the WHO or United Nations have been able to bring countries that are in desperate need of basic mental health care together effectively. Sadly, psychiatry alone cannot do enough in the global context; world mental health is a social issue (Galea, 2013) and much larger than any one profession (Furtos, 2013). This reality underscores the need for urgent development of grassroots community mental health programs.

For over 40 years, community mental health workers have known that a key component of any program’s design is its ability to be flexible (see Lynch & Gardner, 1970). Flexibility allows for the modification and contextualization of programs by local leaders to reflect realities of current social contexts and circumstances (Furtos, 2013; Rock et al., 2001). As aforementioned, this approach grounds the MHF program on the principle that mental health care is a combination of basic, universally applicable and context-specific knowledge and skills. Supportive social networks in the community result in less need for expensive professional treatments and hospitalizations (Forchuk et al., 2005). Moreover, grassroots approaches will aid global attempts at deinstitutionalization.

Governments of low-income countries are constrained by a lack of resources. In fact, in 85% of low-income countries, essential psychotropic medications are not available (Becker & Kleinman, 2013); monies for mental health care are disproportionately lacking even though their associated burden is tremendous (WHO, 2004a). Wider horizontal approaches to global community health care have been successful in the management of childhood illness (Gwatkin, 2004) and can likewise be successful in general mental health care. Furthermore, the benefits of essential psychotropic medications can be greatly enhanced by adjunctive psychosocial treatments including population-based models of mental health care (Patel, Araya, et al., 2007; Patel, Flisher, et al., 2007).

In summary, the MHF program is making an impact from Bhutan to Berlin and from Botswana to Bulgaria. Its training process provides equitable access to first-responder interventions including mental health promotion, advocacy, monitoring and referral, and the implementation of community MHF training furthers the development and delivery of community-based care consistent with WHO’s recommendations for addressing global mental health needs. The population-based, transdisciplinary MHF training model provides countries with a workable human resource development strategy to effectively and equitably bridge the mental health need-care service gap, one country at a time.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The author reported no conflict of interest or funding contributions for the development of this manuscript.

References

Abarquez, I., & Murshed, Z. (2004). Field practitioner’s handbook. Bangkok, Thailand: Asian Disaster Preparedness Center.

Albee, G. W. (1967). The relationship of conceptual models to manpower needs. In E. L. Cowen, E. Gardner, & M. Zax (Eds.), Emergent approaches to mental health problems (pp. 63–73). New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Alonso, J., Chatterji, S., He, Y., & Kessler, R. C. (2013). Burdens of mental disorders: The approach of the World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. In J. Alonso, S. Chatterji, & Y. He (Eds.), The burdens of mental disorders: Global perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health surveys (pp. 1–6). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Alonso, J., Petukhova, M. V., Vilagut, G., Bromet, E. J., Hinkov, H., Karam, E. G.,…Stein, D. J. (2013). Days totally out of role associated with common mental and physical disorders. In J. Alonso, S. Chatterji, & Y. He (Eds.), The burdens of mental disorders: Global perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health surveys (pp. 137–148). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Anand, S., & Bärnighausen, T. (2004). Human resources and health outcomes: Cross-country econometric study. The Lancet, 364, 1603–1609.

Bach, S. (2004). Migration patterns of physicians and nurses: Still the same story? Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82, 624–625.

Barron, R. A. (2004). International disaster mental health. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 27, 505–519.

Becker, A. E., & Kleinman, A. (2013). Mental health and the global agenda. New England Journal of Medicine, 369, 66–73.

Benight, C. C. (2012). Understanding human adaptation to traumatic stress exposure: Beyond the medical model. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4, 1–8.

Bloom, D. E., Cafiero, E. T., Jané-Llopis, E., Abrahams-Gesse, S., Bloom, L. R., Fathima, S., … Weiss, A. (2011). The Global Economic Burden of Non-communicable Diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

Breslau, J., Lee, S., Tsang, A., Lane, M. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso., J.,…Williams, D. R. (2013). Associations between mental disorders and early termination of education. In J. Alonso, S. Chatterji, & Y. He (Eds.), The burdens of mental disorders: Global perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health surveys (pp. 56–65). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Browne, C., & Winkleman, C. (2007). The effect of childhood trauma on later psychological adjustment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 684–697.

Chan, M. (2010). Foreword. In mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings (p. iii). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Chatterji, S., He, Y., & Alonso, J. (2013). Conclusions and future directions. In J. Alonso, S. Chatterji, & Y. He (Eds.), The burdens of mental disorders: Global perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health surveys (pp. 244–247). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, L., Evans, T., Anand, S., Boufford, J. I., Brown, H., Chowdhury, M.,…Wibulpolprasert, S. (2004). Human resources for health: Overcoming the crisis. The Lancet, 364, 1984–1990.

Chisholm, D., James, S., Sekar, K., Kumar, K. K., Murthy, S., Saeed, K., & Mubbashar, M. (2000). Integration of mental health care into primary care. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 581–588.

Coups, E. J., Gaba, A., & Orleans, T. (2004). Physician screening for multiple behavioral health risk factors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27, 34–41.

Craft, A. (2005). What are the priorities for child health in 2004? Child: Care, Health and Development, 31, 1–2.

Demyttenaere, K., Brufferts, R., Posada-Villa, J., Gasquet, I., Kovess, V., Lepine, J. P.,… Chatterji, S. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization Mental Health Surveys. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 2581–2590.

Desjarlais, R., Eisenberg, L., Good, B., & Kleinman, A. (1995). World mental health. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Eaton, J. (2013, October). Document two. In J. de Almeida (Chair), Innovation in deinstitutionalization: A WHO expert survey. Symposium conducted at the International Forum on Innovation in Mental Health, Gulbenkian Global Mental Health Platform, Lisbon, Portugal.

Eaton, J., McCay, L., Semrau, M., Chatterjee, S., Baingana, F., Araya, R.,… & Saxena, S. (2011). Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries, The Lancet, 378, 1592–1603.

Elder, G. H., & Shanahan, M. J. (2007). The life course and human development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology. (Vol. 1, pp. 665–715). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Feiring, C., Taska, L., & Chen, K. (2002). Trying to understand why horrible things happen: Attribution, shame, and symptom development following sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment, 7, 25–39.

Fiore, M. C., Bailey, W. C., Cohen, S. J., Dorfman, S. F., Goldstein, M. G., Gritz, E. R., …Wewers, M. E. (2000). Treating tobacco dependence and use: Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

Forchuk, C., Martin, M. L., Chan, Y. L., & Jensen, E. (2005). Therapeutic relationships: From psychiatric hospital to community. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 12, 556–564.

Fricchione, G. L., Borba, C. P. C., Alem, A., Shibre, T., Carney, J. R., & Henderson, D. C. (2012). Capacity building in global mental health: Professional training. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 20, 47–57.

Furtos, J. (2013, May). Globalization and mental health: The weight of the world, the size of the sky. Presidential symposium conducted at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA.

Galea, S. (2013, May). Re-emerging research around the social and economic production of mental health: Toward a comprehensive model of mental health. Presidential symposium conducted at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA.

Goldberg, D., & Huxley, P. (1992). Common mental disorders: A bio-social model. London, England: Routledge.

Gulbenkian Global Mental Health Platform. (2013a). Integrating mental and physical health, promoting social inclusion, humanizing mental health care. Retrieved from http://www.gulbenkianmhplatform.com/

Gulbenkian Global Mental Health Platform. (2013b). International forum on innovation in mental health. Lisbon, Portugal: Author.

Gureje, O. (2013, October). Document one. In B. Saraceno (Chair), Integrating the response to mental disorders and other chronic diseases in health care systems. Symposium conducted at the International Forum on Innovation in Mental Health, Gulbenkian Global Mental Health Platform, Lisbon, Portugal.

Gwatkin, D. R. (2004). Integrating the management of childhood illness. The Lancet, 364, 1557–1558.

Hines, L. (1970). A nonprofessional discusses her role in mental health. American Journal of Psychiatry, 126, 1467–1472.

Hinkle, J. S. (2006, October). MHF town meeting: Ideas/questions. Presentation at the NBCC Global Mental Health Conference: Focus on the Never Served, New Delhi, India.

Hinkle, J. S. (2007, June). The mental health facilitator training: Ongoing developments. Presentation at the 12th International Counseling Conference, Shanghai, China.

Hinkle, J. S. (2009, July). Mental health facilitation: The challenge and a strategy. Keynote address at the Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development/Association for Counselor Education and Supervision 2nd Annual Conference on Culturally Competent Disaster Response, Gabarone, Botswana.

Hinkle, J. S. (2010a). International disaster counseling: Today’s reflections, tomorrow’s needs. In J. Webber & J. B. Mascari (Eds.), Terrorism, trauma, and tragedies: A counselor’s guide to preparing and responding (3rd ed., pp. 179–184). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Hinkle, J. S. (2010b, August). Mental health facilitation: A global challenge and workable strategy. Manuscript presented at the 18th Asian Pacific Education Counseling Association Biennial Conference-Workshop, Penang, Malaysia.

Hinkle, J. S. (2012a, September). The Mental Health Facilitator program: Optimizing global emotional health one country at a time. Retrieved from http://www.revistaenfoquehumanistico.com/#!Scott Hinkle/c1lbz

Hinkle, J. S. (2012b, May). Mental health facilitation: A global strategy. Manuscript presented at the Asian Pacific Educational Counseling Association Conference, Tokyo, Japan.

Hinkle, J. S. (2012c, October). Population-based mental health facilitation (MHF): A strategy that works. Manuscript presented at the Seventh World Conference on the Promotion of Mental Health and the Prevention of Mental and Behavioural Disorders, Perth, Australia.

Hinkle, J. S. (2013a, February). Population-based mental health facilitation (MHF): Community empowerment and a vision that works. Manuscript presented at the North Carolina Counseling Association 2013 Conference, Greensboro, NC.

Hinkle, J. S. (2013b, November). La salud mental en e mundo. Presentation at the Old Dominion University Counseling Institute, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Hinkle, J. S., & Henderson, D. (2007). Mental health facilitation. Greensboro, NC: NBCC-I.

Hinkle, J. S., Kutcher, S. P., & Chehil, S. (2006, October). Mental health facilitator: Curriculum development. Presentation at the NBCC International Global Mental Health Congress, New Delhi, India.

Hinkle, J. S., & Saxena, S. (2006, October). ATLAS: Mapping international mental health care. Presentation at the NBCC International Global Mental Health Congress, New Delhi, India.

Hinkle, J. S., & Schweiger, W. (2012, September). Mental health facilitation around the world. Manuscript presented at HOLAS Second Counseling Conference of the Americas, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Hoff, L. A. (1993). Review essay: Health policy and the plight of the mentally ill. Psychiatry, 56, 400–419.

Hoff, L. A., Hallisey B. J., & Hoff, M. (2009). People in crisis: Clinical and diversity perspectives (6th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Hongoro, C., & McPake, B. (2004). How to bridge the gap in human resources for health. The Lancet, 364, 1451–1456.

Huston, A. C., & Bentley, A. C. (2010). Human development in societal context. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 411–437.

Isaac, M. (2013, October). Document two. In J. de Almeida (Chair), Innovation in deinstitutionalization: A WHO expert survey. Symposium conducted at the International Forum on Innovation in Mental Health, Gulbenkian Global Mental Health Platform, Lisbon, Portugal.

Jorm, A. F. (2012). Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist, 67, 231–243.

Kabir, B. (2011, January–May). Compassionate and dignified emergency health service delivery in Bangladesh. Asian Disaster Management News, 17(1), 4–6.

Lerner, R. M. (2007). Developmental science, developmental systems, and contemporary theories of human development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 1–17). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Lewin, S. A., Dick, J., Pond, P., Zwarenstein, M., Aja, G., Van Wyk, B.,…Patrick, M. (2005). Lay health workers in primary and community health care. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2005(1), CD004015.

Littleton, H. L., Horsley, S., John, S., & Nelson, D. V. (2007). Trauma coping strategies and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20, 977–988.

Lynch, M., & Gardner, E. A. (1970). Some issues raised in the training of paraprofessional personnel as clinic therapists. American Journal of Psychiatry, 126, 1473–1479.

Marks, I., & Scott, R. (Eds.). (1990). Mental health care delivery, impediments and implementation. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

McKee, L., Ferlie, E., & Hyde, P. (2008). Organizing and reorganizing: Power and change in health care organizations. Houndmills, Bastingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom: Palgrave MacMillan.

McKinlay, J. B. (1990). A case for refocusing upstream: The political economy of illness. In P. Conrad & R. Kern (Eds.), The sociology of health and illness: Critical perspectives (3rd ed., pp. 502–516). New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Mosher, L. R., & Burti, L. (1994). Community mental health: A practical guide. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Murray, C. J. L., & López, A. D. (1996a). Evidence-based health policy: Lessons from the Global Burden of Disease study, Science, 274, 740–743.

Murray, C. J. L., & López, A. D. (1996b). The global burden of diseases: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Boston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health, WHO and World Bank.

Murray, C. J. L., Vos, T., Lozano, R., Naghavi, M., Flaxman, A. D., Michaud, M.,…Andrews, K. G. (2012). Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 380, 2197–2223.

Murthy, R. S. (Ed.). (2006). Mental health by the “people.” Peoples Action for Mental Health, Bangalore, India.

National Board for Certified Counselors-International. (2013). Mental health facilitator (MHF). Retrieved from http://www.nbccinternational.org/What_we_do/MHF

Nolan, K. J., & Cooke, E. T. (1970). The training and utilization of the mental health paraprofessional within the military: The social work/psychology specialist. American Journal of Psychiatry, 127, 74–79.

Paredes, D., Schweiger, W., Hinkle, S., Kutcher, S., & Chehil, S. (2008). The mental health facilitator program: An approach to meet global mental health care needs, Orientacion Psychologica, 3, 73–80.

Patel, V. (2013, October). Integrating mental health care in priority health programs: Addressing a grand challenge in global mental health. Manuscript presented at the International Forum on Innovation in Mental Health, Gulbenkian Global Mental Health Platform, Lisbon, Portugal.

Patel, V., Araya, R., Chatterjee, S., Chisholom, D., Cohen, A., DeSilva, M.,…Van Ommeren, M. (2007). Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 370, 991–1005.

Patel, V., Flisher, A. J., Hetrick, S., & McGorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. The Lancet, 369, 1302–1313.

Prince, M., Patel, V., Saxena, S., Maj, M., Maselko, J., Phillips, M. R., & Rahman, A. (2007). No health without mental health. The Lancet, 370, 859–877.

Rachlis, M., & Kushner, C. (1994). Strong medicine: How to save Canada’s health care system. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Reyes, G., & Elhai, J. D. (2004). Psychosocial interventions in the early phases of disasters. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 41, 399–411.

Rioch, M. J., Elkes, C., Flint, A. A., Usdansky, B. S., Newman, R. G., & Silber, E. (1963). National institute of mental health pilot study in training mental health counselors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 33, 678–689.

Rock, D., Combrinck, J., & Groves, A. (2001). Issues associated with the implementation of routine outcome measures in public mental health services. Australasian Psychiatry, 9, 43–46.

Saraceno, B., van Ommeren, M., Batniji, R., Cohen, A., Gureje, O., Mahoney, J.,…Underhill, C. (2007). Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 370, 1164–1174.

Schweiger, W. K., & Hinkle, J. S. (2013, October). The Mental Health Facilitator (MHF): A program to meet diverse international and domestic needs. Presentation at the 2013 Association for Counselor Educators and Supervisors Conference, Denver, CO.

Scott, K. M., Wu, B., Saunders, K., Benjet, C., He, Y., Lépine, J.-P.,…Von Korff, M. (2013). Early-onset mental disorders and their links to chronic physical conditions in adulthood. In J. Alonso, S. Chatterji, & Y. He (Eds.), The burdens of mental disorders: Global perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health surveys (pp. 87–96). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Sonne, J. L. (2012). PsychEssentials: A pocket resource for mental health practitioners. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Suck, A. T., Kleinberg, E., & Hinkle, J. S. (2013). Counseling in Mexico. In T. H. Hohenshil, N. E. Amundson, & S. G. Niles (Eds.), Counseling around the world: An international handbook (pp. 315–322). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Taylor, S., & Stanton, A. L. (2007). Coping resource, coping processes, and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 377–401. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091.520

Thigpen, J. D. (1979). Perceptional differences in the supervision of paraprofessional mental health workers. Community Mental Health Journal, 15, 139–148.

Unützer, J. (2013, October). Document one. In B. Saraceno (Chair), Integrating the response to mental disorders and other chronic diseases in health care systems. Symposium conducted at the International Forum on Innovation in Mental Health, Gulbenkian Global Mental Health Platform, Lisbon, Portugal.

Ustün, T. B., & Sartorius, N. (Eds.). (1995). Mental illness in general health care: An international study. Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons.

van Wesel, F., Boeije, H., Alisic, E., & Drost, S. (2012). I’ll be working my way back: A qualitative synthesis on the trauma experience of children. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4, 516–526.

Viana, M. C., Gruber, M. J., Shahly, V., de Jonge, P., He, Y., Hinkov, H., & Kessler, R. C. (2013). Family burden associated with mental and physical disorders. In J. Alonso, S. Chatterji, & Y. He (Eds.), The burdens of mental disorders: Global perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health surveys (pp. 122–135). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Vidaver, R. M. (1969). The mental health technician: Maryland’s design for a new health career. American Journal of Psychiatry, 125, 1013–1023.

Vos, T., Flaxman, A. D., Naghavi, M., Lozano, R., Michaud, C., Ezzati, M.,…Murray, C. J. L. (2012). Years lied with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systemic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 380, 2163–2196.

Walt, G. (1988). Community health workers: Policy and practice in national programmes. London, England: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, EPC publication number 16.

Warne, T., & McAndrew, S. (2004). The mental health assistant practitioner: An oxymoron. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 11, 179–184.

Warner, L., & Ford, R. (1998, October). Mental health facilitators in primary care. Nursing Standard, 13, 36–40.

Weissman, M. M., Bland, R. C., Canino, G. J., Faravelli, C., Greenwald, S., Hwu, H. G.,…Yeh, E. K. (1994). The cross national epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 55, 5–10.

Weissman, M. M., Bland, R. C., Canino, G. J., Faravelli, C., Greenwald, S., Hwu, H. G.,…Yeh, E. K. (1997). The cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 305.

Weissman, M. M., Bland, R., Canino, G., Greenwald, S., Lee, C., Newman, S.,…Wickramaratne, P. J. (1996). The cross-national epidemiology of social phobia: A preliminary report. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 11, Suppl: 3, 9–14.

Wekerle, C. (2011). Emotionally maltreated: The under-current of impairment? Child Abuse & Neglect, 35, 899–903. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.09.002

Wells, M. E. (2006). Psychotherapy for families in the aftermath of a disaster. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session, 62, 1017–1027.

Whitlock, E. P., Orleans, C. T., Pender, N., & Allan, J. (2002). Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: An evidenced-based approach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22, 267–284.

WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 2581–2590.

World Health Organization (2004a). Atlas: Country resources for neurological disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

World Health Organization. (2005). Mental health atlas. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

World Health Organization. (2006a). Integrating mental health into primary care: A global perspective. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

World Health Organization. (2006b). Preventing suicide: A resource for counsellors. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

World Health Organization. (2009). Scaling up nursing & medical education: Report on the WHO/PEPFAR planning meeting on scaling up nursing and medical education. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

World Health Organization. (2010a). Mental health and development: Targeting people with mental health conditions as a vulnerable group. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

World Health Organization. (2010b). mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

Dr. J. Scott Hinkle is the Director of Professional Development at NBCC-I. For further information on the MHF program, please contact Adriana Petrini at petrini@nbcc.org. The author appreciates editorial contributions from Laura Jones, Katherine Clark, Ryan Vale, Traci Collins, Allison Jones, and Keith Jones. A version of this article was originally presented at the World Mental Health Congress, August 28, 2013, Buenos Aires, Argentina (Spanish: “Facilitación de Salud Mental (MHF): Una Estrategia Comunal”). Correspondence can be addressed to J. Scott Hinkle, NBCC, 3 Terrace Way, Greensboro, NC 27403, hinkle@nbcc.org.