Richard A. Wantz, Michael Firmin

Numerous sources of information influence how individuals perceive professional counselors. The stressors associated with entering college, developmental differences, and factors associated with service fees may further impact how college students view mental health professionals and may ultimately influence when, for what issues, and with whom they seek support. Individual perceptions of professional counselors furthermore impress upon the overall identity of the counseling profession. Two hundred and sixty-one undergraduate students were surveyed regarding their perceptions of professional counselors’ effectiveness and sources of information from which information was learned about counselors. Overall, counselors were viewed positively on the dimensions measured. The sources that most influenced perceptions were word of mouth, common knowledge, movies, school and education, friends, books, and television.

Keywords: professional counselors, perceptions, counselor effectiveness, professional identity, undergraduates

Perception is not reality, but perception is nonetheless a very cogent relative to how humans come to understand reality. Moreover, perception tends to drive behavior and decisions made by consumers. In the present context, we are interested in how college students come to perceive human service providers across a number of variables. The constructs explored are not novel, as this genre of research has been assessed in decades past (e.g., Murray, 1962; Strong, Hendel, & Bratton, 1971; Tallent & Reiss, 1959; West & Walsh, 1975). However, we believe the topic warrants refreshed attention, particularly with the professional licensure acquired among all human service professions: psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, marriage and family therapists, social workers, and psychiatric nurses.

The media tends to exert a cogent effect on students’ perceptions across multiple life domains, including human service professionals (Von Sydow, Weber, & Christian, 1998). Students also are affected by other information sources such as previous experiences with their high school (guidance) counselors, personal therapy, clergy, family doctors, parental influence, and input from peers (Tinsley, de St. Aubin, & Brown, 1982). Students’ perceptions of human service providers also may be affected by various campaigns, typically receiving information-influence from multiple sources that actively attempt to shape their perceptions of mental health services’ value and efficacy (Hanson, 1998).

Some human service professions have been more aggressive in how they advocate their service value to the public. Fall, Levitov, Jennings, and Eberts (2000) note that psychiatrists and psychologists generally have dwarfed counselors’ efforts at advocacy. Counselors, as a profession, have struggled significantly with their own identity (Garrett & Eriksen, 1999; Eriksen & McAulife, 1999), which likely affects this phenomenon. That is, if one’s identity is unclear to the respective professionals, then probably it will negatively affect its status among the laity (Gale & Austin, 2003). Psychology generally has lagged behind psychiatry in terms of the public’s professional perceptions (Webb & Speer, 1985), although Zytowski et al. (1988) reported that people frequently confused the terms psychiatrist and psychologist relative to function. Counseling psychologists also often seem to be confused with professional counselors in the public’s understanding (Hanna & Bemak, 1997; Lent, 1990).

Social work has existed as a vocation for over a hundred years. Kaufman & Raymond (1995) reported that the public’s awareness of the profession’s perception was somewhat negative in their survey sample. LeCroy and Stinson (2004) and Winston and Stinson (2004) likewise found individuals in their particular sample to be relatively knowledgeable regarding social workers’ responsibilities, although reported attitudes were more positive than those reported by Kaufman and Raymond. This partly may be due to the fact that respondents reported more favorable perceptions of social workers as helping those needing avocation than they did for social workers as therapists. Sharpley, Rogers, and Evans (1984) suggest that marriage and family therapy, as a profession, is relatively cryptic to the general public. That is, people generally deduce what such human service personnel do, as indicated by the title, but do not have as much first-hand knowledge or experience with such professionals as they do with counselors, social workers, psychologists, and other professionals.

Ingham (1985) notes that a helping profession’s overall image affects clinicians in that profession relative to their abilities in helping clients to utilize their services. This conclusion makes logical sense in that consumers’ confidence in the care provided is subjective and highly influenced by psychological variables, such as idiographic perceptions. Attempts at educating the public regarding an apt understanding of what a human service profession has to offer has shown various levels of effectiveness (Pistole & Roberts, 2002). Nonetheless, Pistole (2001) also notes that the general public finds the distinctions among the various human service providers to be bewildering. In short, without periodic reminders, the public’s image of various human service personnel may reconverge in a fog of misperception.

Since many individuals have never experienced the services of mental health clinicians, often their perceptions are based on reports or intuitively acquired opinions. For example, Trautt and Bloom (1982) report that fee structures affect perceptions of status and effectiveness provided by clinicians. The basic understanding, of course, is that the more expensive the treatment, the higher its perceived value and professional status. That, of course, can result in self-fulfilling prophesies—with people paying more money expecting more from therapy—and experiencing better success rates. We are unaware of any studies where clients were randomly assigned to professional therapists and (systematically) charged varying pay rates. Such a study, controlling for fee structures, might yield some valuable data to the present discussion regarding how the public perceives the value of respective human service professionals.

Beyond the public’s general perceptions on this topic, however, we are particularly focused on students’ perceptions. Hundreds of thousands of students annually utilize the services of university counseling centers, as well as private practice therapists and other human service agencies. With the added stress of academics, social pressures, being away from home for the first time, transitioning from teenage to adult responsibilities, dating, drinking alcohol, and other similar stressors, having apt utilization of psychotherapeutic services is paramount for college students. Turner and Quinn (1999) suggest that college students’ perceptions differ from the population-in-general, and research data from one group may not accurately generalize to the other.

Notwithstanding obvious developmental differences between college students and more mature adults from the general population, counseling students may not pay (directly, out of pocket) for the services available to them. Campus counseling centers, for example, typically receive funding from tuition or generic student fees, rather than students paying direct dollars for the services. Additionally, most full-time students remain on their parents’ medical insurance which also offsets financial costs involved in private practice expenses. In short, cost of services seems to be a significant variable for the general population (Farberman, 1997) that may not load with the same degree of importance vis-a-vis college students. Additionally, titles (such as “doctor”) may not have as much bearing with the general public (Myers & Sweeney, 2004) as they do with college students who routinely use such nomenclature with professors and others on a daily basis. In short, while we accommodate research findings that compare the various mental health professionals as perceived by the general public (e.g., Murstein & Fontaine, 1993), we also treat the results with some degree of prudence and believe college students represent a distinct population worthy of particular focus and exploration.

Gelso, Brooks, and Karl (1975) conducted a study that was similar in some respects to our present one. They surveyed 187 students from a large eastern university with a sample of 103 females and 84 males. Subjects were asked to rate perceived characteristics of various human service professionals, including high school counselors, college counselors, advisers, counseling psychologists, clinical psychologists, and psychiatrists. They found that overall college students did not report significant differences relative to professionals’ personal characteristics. However, they did report differences among the human service providers relative to their perceived competencies in treating various hypothetical presenting problems.

In the 30 years subsequent to this study, we are interested in how student perceptions have changed over time. Additionally, the Gelso, Brooks, and Karl (1975) study did not account for students’ perceptions of social workers, marriage and family therapists, or psychiatric nurses. Given the present milieu, we are more interested in these professionals than the categories of school counselors or advisors. Additionally, we also chose to combine the categories of counseling and clinical psychologists into the generic grouping, “psychologist.” The specific questions asked of students also differed in our present study. However, the general tenor of the two studies is similar—and we believe the updating of knowledge in this area has significant importance for those working with college students in various capacities and milieus.

Warner and Bradley (1991) also conducted a study similar to the present one. Their participants included 60 men and 60 women who were undergraduate college students enrolled in a University of Montana introductory psychology course. They assessed student perceptions of master’s-level counselors, clinical psychologists, and psychiatrists on multiple variables. Findings included students reporting their perceptions of counselors as possessing more caring-type qualities. Psychiatrists were seen as most able to address severe psychopathology and psychologists were viewed as more academics and researchers than as therapists.

Method

Participants

We surveyed 261 students from three sections of a general psychology course for this study. The course was selected, in part, because it is included in the university’s general studies core curriculum. Consequently, it represented a relatively wide range of majors from the student body and included students from freshman through senior status. The sample was taken at a selective, private, comprehensive university located in the Midwest with a study body of approximately 3,000 students. It included 167 women and 92 men with ages ranging from 17 to 55. The students were mostly Caucasian with 9% identifying themselves as ethnic minorities representing 34 states.

Procedure

The instrument was first pilot tested (Goodwin, 2005) to a group of undergraduate students at a regional state university prior to utilizing it in the present research project. Modifications were made in clarifying ambiguous terminology, instructions, and time to complete. Due to practical considerations, the instrument was designed to be completed in about one-half of a normal class period. The survey was administered during a normal class period with students having the option to participate at will without reward or penalty for doing so. Two students chose not to complete the surveys for undisclosed reasons.

The survey queried students regarding their perceptions of human service professionals (HSP), taking about 20–25 minutes to complete. Anonymity was provided to all students regarding answers to all items. Questions were asked about the overall perceived effectiveness of various HSPs, for which types of problems they might recommend various HSPs, and overall perceptions about the various HSPs. Although obviously many types of HSPs exist, this particular survey focused on psychiatrists, psychologists, professional counselors, marriage & family therapists, social workers and psychiatric nurses. In order to control for order effects as potential threats to internal validity (Sarafino, 2005), the various HSPs were presented in random order each time they appeared throughout the survey. The amount of data collected from the survey was relatively substantial. However, given the practical number of journal pages that can be reasonably devoted to presenting the information, along with our desire to comprehensively address perceptions of counselors, the present article addresses only this particular segment of the data collection.

Results

We organized the survey’s results in terms of the counseling services utilized, how effective students perceived counseling to be, for what types of problems or issues counselors are thought to be apt, how students came to view their perceptions of professional counselors, and qualities thought to characterize professional counselors. All percentages are rounded for clarity of reading and presentation, except where percentages fall below 1%.

Types of Services Utilized

At the end of the questionnaire, students were asked to confidentially self-disclose whether or not they had received services from a HSP. The question was placed at the end in order to have students already somewhat acclimated to HSPs and to have them somewhat more comfortable with the world of different types of HSPs. Of those answering the question, 28% of the participants indicated having received assistance from a HSP prior to completing the survey. The specific question asked whether or not students received prior professional assistance regarding personal, social, occupational or mental health concerns. About 3% of all the participants chose not to answer this particular question. However, of the 28% only 1% indicated that they did not know the profession of their HSP, indicating that most of the respondents who previously had utilized HSP services were aware whether the professional they saw was a counselor, psychologist, social worker, etc. Relatively few (

States possess a variety of titles by which professional counselors can or should be called (Freeman 2006). Consequently, rather than asking students simply to identify whether or not they had previously utilized the services of a “counselor,” we specified some types of counselors they may have seen. These included professional counselor, pastoral counselor, addictions or chemical dependency counselor, rehabilitation counselor, clinical mental health counselor, professional clinical counselor, and school guidance counselor.

Of the 28% of students who indicated they had previously utilized HSP services, three particular types of counselors were more prominent than the others. Namely, 16% indicated having seen a school counselor, 11% saw a professional counselor, and 9% saw a pastoral counselor. Relatively few students indicated having seen a rehabilitation counselor (0.4%), an addictions counselor (0.8%), or a mental health/clinical counselor (3%).

Perceived Overall Effectiveness

Students were asked to indicate how effective they believed professional counselors are overall. The particular question was worded as follows: In general, what is your opinion about how overall effective professional counselors would be with helping a mental health consumer? The options provided, with descriptors in parenthesis, were 1 (Positive), 2 (Neutral), 3 (Negative), and 4 (Unsure or don’t know). The intent of the question was to capture the gestalt of students’ thinking regarding professional counselors, prior to probing more deeply vis-a-vis types of counselors and for which kinds of issues they might find effective interventions.

Only 3% of the participants indicated having no opinion regarding this question. Another 3% indicated viewing professional counselors negatively. A total of 28% of the participants indicated having neutral views regarding counselors’ overall effectiveness. Sixty-six percent of the participants indicated having a positive view of professional counselors.

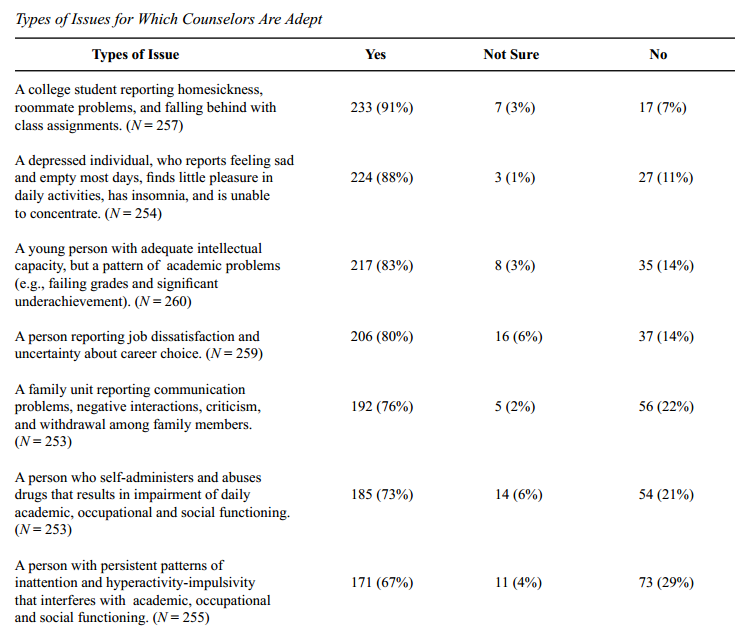

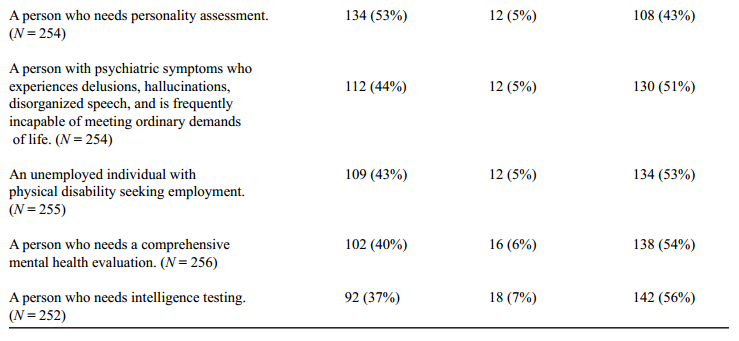

Types of Issues for Which Counselors Are Adept

Students were asked to identify for what types of issues they believed professional counselors would be particularly adept. They were provided with 12 different issues and asked to rate them as Yes (I would recommend a professional counselor for this situation), No (I would not recommend a professional counselor for this situation), or NS (Not sure, not familiar). Relatively few students skipped these questions or chose not to respond (range=0.8% to 3.4%). In other words, response rates were consistently high for these questions, obviously adding to the interpretation process. The same is true with students indicating that they were unsure or unfamiliar. Namely, on average 4% or so of students indicated being unsure for the situations presented (range=1.9 to 6.9). Results showed three clusters of participants’ responses.

The first cluster had four prominent responses, exhibited by 80% or more of the respondents—they involved college issues, academic problems, depression, and career counseling. A total of 91% of the participants indicated believing a professional counselor would be effective for helping college students who report homesickness, roommate problems, and falling behind with class assignments. A similar number (88%) believed that a professional counselor would be effective with a depressed individual who reports feeling sad and empty most days, finds little pleasure in daily activities, has insomnia, and is unable to concentrate. Comparable responses (83%) were seen for professional counselors addressing a young person with adequate intellectual capacity, but a pattern of academic problems (e.g., failing grades and significant underachievement). Finally, 80% of participants indicated that a professional counselor would be effective for a person reporting job dissatisfaction and uncertainty about career choices.

The next cluster of responses involved issues of family dysfunction, substance abuse, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Seventy-six percent of participants indicated feeling that professional counselors were effective for a family unit reporting communication problems, negative interactions, criticism, and withdrawal among family members. For cases when a person self-administers and abuses drugs that results in impairment of daily academic, occupational and social functioning, 73% of the respondents in our survey believed a professional counselor would be effective. Sixty-seven percent of participants indicated that a professional counselor would be effective when a person with persistent patterns of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with academic, occupational, and social function.

The final cluster of participants’ responses involved issues of personality assessment, intelligence testing, psychotic symptoms, physical disabilities, and mental health evaluations. Just over half (53%) of the participants indicated that professional counselors were apt for working with a person who needs personality assessment. Forty-four percent said that a professional counselor would be effective for a person with psychiatric symptoms who experiences delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and is frequently incapable of meeting ordinary demands of life. When asked if an unemployed individual with a physical disability seeking employment would be a target source for a professional counselor, 43% answered affirmatively. Only 40% of participants indicated that a professional counselor would be effective in helping a client who needs a comprehensive mental health evaluation. Fewer (37%) indicated that intelligence testing was germane for a professional counselor.

Table 1

Sources of Perceptions about Counselors

Another line of inquiry addressed the identified sources by which students indicated they developed their perceptions about counselors. In other words, they told us about the factors that influenced them the most regarding how they came to think about professional counselors. The options from which to choose included books, common knowledge, friends or associates, HSPs, insurance company or carrier, Internet, magazines, physician or nurse, movies, newspapers, personal experience, school and education, and television. Only 2% of the participants declined to participate in this section of the survey or marked “none.”

Instructions asked students to complete this section in two steps. First, they were to indicate (by checking a corresponding box) whether or not they learned about a professional counselor from the identified source. Students were told they could select multiple sources. In the second step, they were asked to rate whether the information about the HSP was 1 (positive), 2 (neutral) or 3 (negative). Only 2% of the students marked a box described as “other,” indicating that the categories provided were relatively comprehensive. Results from this portion of the survey showed the data falling into three clusters. The two clusters representing extreme scores were of relatively equal size, while the third or middle was small (only two sources in the category).

The first cluster showed the following items as being relatively influential in how students came to understand the roles of professional counselors: common knowledge (84%), movies (63%), school and education (60%), friends (55%), books (49%) and television (44%). The middle cluster included personal experience (27%) and Internet (24%). The finding that 27% indicated personal experience to be influential is consistent with the demographic portion of the questionnaire where 28% of students said they had personal contact with a HSP prior to completing the survey. The third cluster comprised those sources that participants said were relatively non-influential in generating their perceptions of professional counselors. They included magazines (20%), physician or nurse (18%), newspaper (13%), HSPs (10%) and insurance companies (5%).

Results from the second step in the survey are more difficult to summarize. The data was more dispersed than the first step, although three clusters inductively emerged. Some items received few responses, as they were not selected very frequently in step one. The percentages listed do not add up to 100% for each item because the remaining percentage for each item is accounted by students who did not provide answers for that item. For example, if an item had 1% positive, 1% neutral, and 1% negative, then 97% of the participants simply left the question blank.

The first were items where students indicated that professional counselors were as viewed mostly positive. These included school and education (43% positive, 13% neutral and 3% negative), friends (38% positive, 10% neutral and 6% negative), books (30% positive, 17% neutral and 2% negative), personal experience (17% positive, 7% neutral and 3% negative), physicians (10% positive, 6% neutral and 2% negative), and HSPs (8% positive, 0.8% neutral and 0.8% negative).The second cluster comprised items that were rated as being mostly neutral and with relatively few positive indicators. These included: movies (14% positive, 28% neutral and 19% negative) and television (13% positive, 25% neutral and 6% negative). The third cluster showed a relative spread of responses, although there were few negatives in each category. They included: common knowledge (38% positive, 42% neutral and 3% negative), magazines (10% positive, 8% neutral 3% negative), Internet (10% positive, 12% neutral and 1% negative), newspapers (5% positive, 6% neutral and 3% negative), and insurance companies (0.8% positive, 2% neutral and 2% negative).

Perceived Counselor Qualities

The final portion of the questionnaire addressed how participants viewed various professional counselors’ characteristics. Students were asked to identify statements that they believed to be true about professional counselors, based on their overall knowledge of them. Options included competent, can be in independent private practice, diagnose and treat mental and emotional disorders, doctoral degree required to practice, intelligent/smart, overpaid, prescribe medication and trustworthy. Consistently, only 1% of the participants chose not to respond to this portion of the survey, making interpretation for this section relatively straightforward. The findings fell neatly into two categories: characteristics counselors presumably possess and those they do not.

Characteristics that students believed professional counselors possess include being competent (81%), independent private practice (81%), trustworthy, (79%), and intelligent/smart (77%). Contrariwise, participants identified the following as not characterizing professional counselors, as indicated by the relatively low percentages of marked responses: doctorate required (30%), diagnose and treat mental disorders (22%), overpaid (16%) and prescribe medications (5%).

Discussion

Given the formation and advancement of the American Mental Health Counseling Association (AMCHA), the introduction of state licensure laws that specifically use mental health counselors as formal nomenclature (Freeman, 2006), and particular certifications that have been offered in clinical mental health counseling, we were somewhat surprised that only 3% of the students who had previously used HSP services identified doing so with clinical mental health counselors. Of course, they may have been confused with names, but to the degree that accurate reporting occurred, the numbers were relatively low compared to other types of counselors.

Obviously, school counselors are very important relative to how students perceive professional counselors. They accounted for the largest portion of users (16%). First impressions are not always necessarily lasting impressions. However, they are cogent and school counselors may set the tone for how these students, for the rest of their lives, perceive others using the word “counselor” in their professional titles. This sentiment was illustrated in qualitative research findings by Wantz, Firmin, Johnson, and Firmin (2006).

Three times as many students indicated having seen a pastoral counselor than a mental health counselor (9% and 3%, respectively). Obviously, we do not know if some students actually meant that they saw an ordained clergy person for personal issues, considering this person to be a pastoral counselor, since they received counseling from him/her and the person was clergy. However, assuming accurate reporting, it suggests that graduate training programs should consider giving additional attention to this domain of counseling. Although courses in pastoral counseling sometimes are seen in religiously-oriented universities (e.g., seminaries, Catholic or Christian colleges), the apparent popularity of their use by students, suggested by the present research, provides evidence that more widespread attention to pastoral counseling is warranted.

Students’ overall perception of professional counselors as being effective is heartening. Particularly welcoming is that only 3% viewed counselors negatively. Social psychology research (Myers, 1994) has shown that a few negative, public incidences can have overshadowing effects on a group’s overall positive characteristics. Fortunately for professional counselors, whatever data might feed negative overall impressions seems to be relatively dormant for students in the present sample.

A general continuum emerged vis-a-vis students’ perceptions of what types of issues are most germane for professional counselors to address. Namely, high responses were provided for general, developmental life issues such as academic problems, depression and career counseling. Moderate responses were provided for problems where direct brain-behavior connections are involved such as ADHD or drug counseling. The lowest responses were provided for types of situations where assessment is warranted, such as personality or intellectual assessment and mental health evaluations. These findings are consistent with overall perceptions that students do not think of counselors in terms of being clinical mental health professionals, but rather as more generic, trained counselors. If the field wishes to advance itself toward the direction of diagnosis, assessment, and treating psychopathology, then data from the present survey would suggest that efforts should be redoubled.

Not all media sources appear to be equal in influencing students’ perceptions of professional counselors. For example, newspapers (13%), magazines (20%), and the Internet (24%) were relatively inconsequential when compared to movies (63%), books (49%) and television (44%). Unfortunately for professional counseling organizations, the most potentially influential sources also happen to be the most expensive ones to target. Nonetheless, if organizations such as the American Counseling Association (ACA), American Mental Health Counselors Association (AMCHA), and the National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC) are going to impact students’ thinking, then they should target the most efficacious sources. It could be, of course, that the reason newspapers, magazines and the Internet were so relatively non-influential is that few inroads have been attempted in these domains. Advertising in university newspapers, posting and promoting user-friendly web sites, and generating informative articles in popular magazines simply may be an important need for professional counseling advocacy at this time.

In a separate study under development, using qualitative methodology, we are attempting to better flesh-out some of the details relating to these sources of impact on students’ perceptions of professional counselors, particularly the concept of “common knowledge.” Although not surveyed in this study, an influential source proved to be word-of-mouth in perception formations regarding counseling. That is, influences of school, friends, personal experience, physicians, and HSPs most likely have some type of personal connections tied to the medium. Evidently, there is some truth to the adage that word-of-mouth is the best means of advertising—assuming, of course, that the messages being relayed are positive.

In the perceived counselor qualities portion of the survey, it was somewhat disheartening that comparatively few (22%) students indicated they saw professional counselors as competent to diagnose and treat mental disorders. This finding was consistent with other data throughout the survey. Namely, students generally view counselors as professionals who address relatively normal, human development issues rather than psychopathology or more severe disorders requiring assessment, diagnosis and treatment. Again, if the counseling profession wishes to move in the latter direction, then findings from the present research suggest that there is some distance to go. Early acquired school counselor perceptions tended to initiate students’ mindsets regarding what counselors do and they seem not to have moved far from those early perceptions.

In summary, we believe that the present study is a strong first step in a line of needed research regarding just how people come to understand counselors. The findings here do not dictate any action on behalf of professional counseling organizations. However, we believe that the findings indicate in which directions the winds of student perceptions are blowing—and that is data which should be considered when making policy decisions. If counselors are going to move to new, future levels of excellence in terms of public perception, then paying attention to this type of data and giving it due consideration is an important initial component.

Limitations and Future Research

All good research studies report limitations (Murnan & Price, 2004) and we indicate four of them here. First, while our sample had several strengths, including adequate size (Patten, 1998), high response rate (Stoop, 2004), and lack of incentives/bribes for participation (Storms & Loosveldt, 2004), it was taken from a single locale. Some compensation exists, such as students coming from 34 states and the relatively broad cross-section of college majors represented. However, future research in this domain should assess students from a wider variety of institutions such as research universities, state universities, and liberal arts colleges—as well as from diverse locales in the country in order to enhance the study’s external validity (Cohen & Wenner, 2006).

Second, our study had relatively low representation from minority students. This simply was an artifact of the university where the data was collected. Specifically, minorities comprised only 6% of the student body population. Further research should contain samples with larger representations of minority individuals. Additionally, replicating this present study with all minority students would provide an interesting comparison among many points of investigation.

Third, some of the items queried were selected a priori. While we believe them to be of interest and germane to our purposes, future research should broaden questionnaires to include questions that are derived empirically from the research literature. Also, organizations such as the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs should provide input vis-a-vis questions that directly would enhance their efforts in counselor education preparation. The same is true with potential input from NBCC and ACA as they market professional counselors to the general population as well as college students.

Fourth, in retrospect there are two particular changes we would have made to the survey instrument. One is that we would have added a Likert-scale to the first question, querying the perceived overall effectiveness of counselors. While we believe that rating professional counselors with three choices was useful—and we would keep the question—we also would recommend future researchers add a Likert-scale question that is anchored with descriptions, but to which numeric interval-scale values could be assessed. Second, looking back on our questionnaire, we would have asked how many students saw more than one HSP. That is, did they use more than one type of human service professional’s services (e.g., they saw both a rehabilitation counselor and a school counselor). Accounting for multiple uses within the same clientele could provide potentially useful data.

Future research should take the present study and apply it to the population in general. That is, we produced what we believe to be fairly apt representations of perceptions among students—but they do not represent the population at large. Obviously, college students have unique features of adult development that are not necessarily shared by older adults (Foos & Clark, 2003). The very low reported influence that health insurance companies have on college students’ perceptions is one of many examples of where student ideations and those of more middle-aged adults might differ.

And finally, qualitative research is needed in this area. A prime value of questionnaires, such as the present one, is that more voluminous amounts of data can be collected—providing breadth of understanding (Gall & Borg, 2003). Such research also tends to answer “how many” or “what” types of questions (Hittleman & Simon, 2003). Thicker descriptions are needed to help flesh-out some of the details on which survey research was only able to skim. Answers to some of the “why” and “how” questions that the present findings raise can best be answered with follow-up qualitative research methodology (Flick, 2002).

References

Cohen, J., & Wenner, C. J. (2006, May). Convenience at a cost: College student samples. Poster presented at the annual convention of the Association for Psychological Science, New York, NY.

Eriksen, K. P., & McAuliffe, G. J. (1999). Toward a constructivist and developmental identity of the counseling profession: The context-phase-state-style model. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77, 267–280.

Fall, K. A., Levitov, J. E., & Eberts, S. (2000). The public perception of mental health professions: An empirical examination. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 22, 122–134.

Farberman, R. K. (1997). Public attitudes about psychologists and mental health care: Research to guide the American Psychological Association public education campaign. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 28, 128–136.

Foos, P. W., & Clark, M. C. (2003). Human aging. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Flick, U. (2002). An introduction to qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Freeman, L. (2006). Licensure requirements for professional counselors. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Gale, A. U., & Austin, B. D. (2003). Professionalism’s challenges to professional counselors’ collective identity. Journal of Counseling & Development, 81, 3–10.

Gall, M. D., & Borg, W. R. (2003). Educational research (7th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Garrett, J. M., & Eriksen, K.P. (1999). Toward a constructivist and developmental identity for the counseling profession: The context-phase-stage-style model. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77, 267–280.

Gelso, C. J., Brooks, L., & Karl, N. J. (1975). Perceptions of “counselors” and other help givers: A consumer analysis. Journal of College Student Personnel, 16, 287–292.

Goodwin, C. J. 92005). Research in psychology: Methods and design (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Hann, F. J., & Bemak, F. (1997). The quest for identity in the counseling profession. Counselor Education and Supervision, 36, 194–206.

Hanson, K. W. (1998). Public opinion and the mental health parity debate: Lessons from the survey literature. Psychiatric Services, 49, 1059–1066.

Hittleman, D., & Simon, A. (2006). Interpreting educational research (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ingham, J. (1985). The public image of psychiatry. Social Psychiatry, 20, 107–108.

Murstein, B. I., & Fonatine, P.A. (1993). The public’s knowledge about psychologists and other mental health professionals. Psychology in Action, 48, 839–845.

Kaufman, A. V., & Raymond, G. T. (1995). Public perception of social workers: A survey of knowledge and attitudes. Arete, 20, 24–35.

Lecroy, C. W., & Stinson, E. L. (2004). The public’s perception of social work: Is it what we think it is? Social Work, 49, 164–175.

Lent, R. W. (1990). Further reflections on the public image of counseling psychology. Counseling Psychologist, 18, 324–332.

Murnan, J., & Price, J. H. (2004). Research limitations and the necessity of reporting them. American Journal of Health Education, 35, 66–67.

Murray, C. M. (1962). College students’ concepts of psychologists and psychiatrists: A problem of differentiation. The Journal of Social Psychology, 57, 161–168.

Myers, D. G. (1994). Exploring social psychology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2004). Advocacy for the counseling profession: Results of a national survey. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82, 466–471.

Patten, M. L. (1998). Questionnaire research. Los Angeles: Pyrczak.

Pistole, M. C. (2001). Mental health counseling: Identity and distinctiveness. ERIC reproduction services. EDO-CG-01-09. 1–4.

Pistole, M. C., & Roberts, A. (2002). Mental health counseling: Toward resolving identity confusions. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 24, 1–19.

Sarafino, W. P. (2005). Research methods. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Sharpley, C. F., Rogers, H. J., & Evans, N. (1984). ‘Me! Go to a marriage counselor! You’re joking!’: A survey of public attitudes to and knowledge of marriage counseling. Australian Journal of Sex, Marriage, and Family, 5, 129–137.

Stoop, I. (2004). Surveying nonrespondents. Field Methods, 16, 23–54.

Strong, S. R., Hendel, D. D., & Bratton, J. C. (1971). College students’ views of campus help-givers: Counselors, advisers, and psychiatrists. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 18, 234–238.

Storms, V., & Loosveldt (2004). Who responds to incentives? Field Methods, 16, 414–421.

Tallent, N., & Reiss, W. J. (1959). The public’s concepts of psychologists and psychiatrists: A problem of differentiation. The Journal of General Psychology, 61, 281–285.

Tinsley, H. E., de St. Aubin, T. M., & Brown, M. T. (1982). College students’ help-seeking preferences. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 5, 523–533.

Trautt, G. M., & Bloom, L. J. (1982). Therapeugenic factors in psychotherapy: The effects of fee and title on credibility and attraction. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38, 274–279.

Turner, A. L., & Quinn, K. F. (1999). College students’ perceptions of the value of psychological services: A comparison with APA’s public education research. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 30, 368–371.

Von Sydow, K., Weber, A., & Reimer, C. (1998). Psychotherapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists in the media: A content analysis of cover pictures in eight German magazines, published 1947–1995. Psychotherapeut, 43, 80–92.

Wantz, R., Firmin, M., Johnson, C., & Firmin, R. (2006, June). University student perceptions of high school counselors. Poster presented at the 18th Annual Enthnographic and Qualitative Research in Education conference, Cedarville, OH.

Warner, D. L., & Bradley, J. R. (1991). Undergraduate psychology students’ views of counselors, psychiatrists, and psychologists: A challenge to academic psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 2, 138–140.

Webb, A. R., & Speer, J. R. (1985). The public image of psychologists. American Psychologist, 40, 1064–1065.

West, N. D., & Walsh, M. A. (1975). Psychiatry’s image today: Results of an attitudinal survey. American Journal of Psychiatry, 132, 1318–1319.

Winston, L., & Stinson, E. L. (2004). The public’s perception of social work: Is it what we think it is? National Association of Social Workers, 49, 164–174.

Zytowski, D. G., Casas, J. M., Gilbert, L. A., Lent, R. W., & Simon, N. P. (1988). Counseling psychology’s public image. Counseling Psychologist, 16, 332–346.

Richard A. Wantz, NCC, is a Professor at Wright State University, and Michael Firmin, NCC, teaches at Cedarville University, both in Ohio. Correspondence can be addressed to Richard A. Wantz, Wright State University, Department of Human Services, 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway, Dayton, OH, 45435, richard.wantz@wright.edu.