Aug 20, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 3

Warren N. Ponder, Elizabeth A. Prosek, Tempa Sherrill

First responders are continually exposed to trauma-related events. Resilience is evidenced as a protective factor for mental health among first responders. However, there is a lack of assessments that measure the construct of resilience from a strength-based perspective. The present study used archival data from a treatment-seeking sample of 238 first responders to validate the 22-item Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-22) and its abbreviated version, the RSES-4, with two confirmatory factor analyses. Using a subsample of 190 first responders, correlational analyses were conducted of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 with measures of depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and suicidality confirming convergent and criterion validity. The two confirmatory analyses revealed a poor model fit for the RSES-22; however, the RSES-4 demonstrated an acceptable model fit. Overall, the RSES-4 may be a reliable and valid measure of resilience for treatment-seeking first responder populations.

Keywords: first responders, resilience, assessment, mental health, confirmatory factor analysis

First responder populations (i.e., law enforcement, emergency medical technicians, and fire rescue) are often repeatedly exposed to traumatic and life-threatening conditions (Greinacher et al., 2019). Researchers have concluded that such critical incidents could have a deleterious impact on first responders’ mental health, including the development of symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, or other diagnosable mental health disorders (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014; Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2010). In a systematic review, Wild et al. (2020) suggested the promise of resilience-based interventions to relieve trauma-related psychological disorders among first responders. However, they noted the operationalization and measure of resilience as limitations to their intervention research. Indeed, researchers have conflicting viewpoints on how to define and assess resilience. For example, White et al. (2010) purported popular measures of resilience rely on a deficit-based approach. Counselors operate from a strength-based lens (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014) and may prefer measures with a similar perspective. Additionally, counselors are mandated to administer assessments with acceptable psychometric properties that are normed on populations representative of the client (ACA, 2014, E.6.a., E.7.d.). For counselors working with first responder populations, resilience may be a factor of importance; however, appropriately measuring the construct warrants exploration. Therefore, the focus of this study was to validate a measure of resilience with strength-based principles among a sample of first responders.

Risk and Resilience Among First Responders

In a systematic review of the literature, Greinacher et al. (2019) described the incidents that first responders may experience as traumatic, including first-hand life-threatening events; secondary exposure and interaction with survivors of trauma; and frequent exposure to death, dead bodies, and injury. Law enforcement officers (LEOs) reported that the most severe critical incidents they encounter are making a mistake that injures or kills a colleague; having a colleague intentionally killed; and making a mistake that injures or kills a bystander (Weiss et al., 2010). Among emergency medical technicians (EMTs), critical incidents that evoked the most self-reported stress included responding to a scene involving family, friends, or others to the crew and seeing someone dying (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014). Exposure to these critical incidents may have consequences for first responders. For example, researchers concluded first responders may experience mental health symptoms as a result of the stress-related, repeated exposure (Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2010). Moreover, considering the cumulative nature of exposure (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014), researchers concluded first responders are at increased risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and generalized anxiety symptoms (Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2010). Symptoms commonly experienced among first responders include those associated with post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression.

In a collective review of first responders, Kleim and Westphal (2011) determined a prevalence rate for PTSD of 8%–32%, which is higher than the general population lifetime rate of 6.8–7.8 % (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2017). Some researchers have explored rates of PTSD by specific first responder population. For example, Klimley et al. (2018) concluded that 7%–19% of LEOs and 17%–22% of firefighters experience PTSD. Similarly, in a sample of LEOs, Jetelina and colleagues (2020) reported 20% of their participants met criteria for PTSD.

Generalized anxiety and depression are also prevalent mental health symptoms for first responders. Among a sample of firefighters and EMTs, 28% disclosed anxiety at moderate–severe and several levels (Jones et al., 2018). Furthermore, 17% of patrol LEOs reported an overall prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder (Jetelina et al., 2020). Additionally, first responders may be at higher risk for depression (Klimley et al., 2018), with estimated prevalence rates of 16%–26% (Kleim & Westphal, 2011). Comparatively, the past 12-month rate of major depressive disorder among the general population is 7% (APA, 2013). In a recent study, 16% of LEOs met criteria for major depressive disorder (Jetelina et al., 2020). Moreover, in a sample of firefighters and EMTs, 14% reported moderate–severe and severe depressive symptoms (Jones et al., 2018). Given these higher rates of distressful mental health symptoms, including post-traumatic stress, generalized anxiety, and depression, protective factors to reduce negative impacts are warranted.

Resilience

Broadly defined, resilience is “the ability to adopt to and rebound from change (whether it is from stress or adversity) in a healthy, positive and growth-oriented manner” (Burnett, 2017, p. 2). White and colleagues (2010) promoted a positive psychology approach to researching resilience, relying on strength-based characteristics of individuals who adapt after a stressor event. Similarly, other researchers explored how individuals’ cognitive flexibility, meaning-making, and restoration offer protection that may be collectively defined as resilience (Johnson et al., 2011).

A key element among definitions of resilience is one’s exposure to stress. Given their exposure to trauma-related incidents, first responders require the ability to cope or adapt in stressful situations (Greinacher et al., 2019). Some researchers have defined resilience as a strength-based response to stressful events (Burnett, 2017), in which healthy coping behaviors and cognitions allow individuals to overcome adverse experiences (Johnson et al., 2011; White et al., 2010). When surveyed about positive coping strategies, first responders most frequently reported resilience as important to their well-being (Crowe et al., 2017).

Researchers corroborated the potential impact of resilience for the population. For example, in samples of LEOs, researchers confirmed resilience served as a protective factor for PTSD (Klimley et al., 2018) and as a mediator between social support and PTSD symptoms (McCanlies et al., 2017). In a sample of firefighters, individual resilience mediated the indirect path between traumatic events and global perceived stress of PTSD, along with the direct path between traumatic events and PTSD symptoms (Lee et al., 2014). Their model demonstrated that those with higher levels of resilience were more protected from traumatic stress. Similarly, among emergency dispatchers, resilience was positively correlated with positive affect and post-traumatic growth, and negatively correlated with job stress (Steinkopf et al., 2018). The replete associations of resilience as a protective factor led researchers to develop resilience-based interventions. For example, researchers surmised promising results from mindfulness-based resilience interventions for firefighters (Joyce et al., 2019) and LEOs (Christopher et al., 2018). Moreover, Antony and colleagues (2020) concluded that resilience training programs demonstrated potential to reduce occupational stress among first responders.

Assessment of Resilience

Recognizing the significance of resilience as a mediating factor in PTSD among first responders and as a promising basis for interventions when working with LEOs, a reliable means to measure it among first responder clients is warranted. In a methodological review of resilience assessments, Windle and colleagues (2011) identified 19 different measures of resilience. They found 15 assessments were from original development and validation studies with four subsequent validation manuscripts from their original assessment, of which none were developed with military or first responder samples.

Subsequently, Johnson et al. (2011) developed the Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-22) to assess resilience among military populations. Unlike deficit-based assessments of resilience, they proposed a multidimensional construct representing how individuals respond to stressful experiences in adaptive or healthy ways. Cognitive flexibility, meaning-making, and restoration were identified as key elements when assessing for individuals’ characteristics connected to resilience when overcoming hardships. Initially they validated a five-factor structure for the RSES-22 with military active-duty and reserve components. Later, De La Rosa et al. (2016) re-examined the RSES-22. De La Rosa and colleagues discovered a unidimensional factor structure of the RSES-22 and validated a shorter 4-item subset of the instrument, the RSES-4, again among military populations.

It is currently unknown if the performance of the RSES-4 can be generalized to first responder populations. While there are some overlapping experiences between military populations and first responders in terms of exposure to trauma and high-risk occupations, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA; 2018) suggested differences in training and types of risk. In the counseling profession, these populations are categorized together, as evidenced by the Military and Government Counseling Association ACA division. Additionally, there may also be dual identities within the populations. For example, Lewis and Pathak (2014) found that 22% of LEOs and 15% of firefighters identified as veterans. Although the similarities of the populations may be enough to theorize the use of the same resilience measure, validation of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 among first responders remains unexamined.

Purpose of the Study

First responders are repeatedly exposed to traumatic and stressful events (Greinacher et al., 2019) and this exposure may impact their mental health, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and suicidality (Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018). Though most measures of resilience are grounded in a deficit-based approach, researchers using a strength-based approach proposed resilience may be a protective factor for this population (Crowe et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020). Consequently, counselors need a means to assess resilience in their clinical practice from a strength-based conceptualization of clients.

Johnson et al. (2011) offered a non-deficit approach to measuring resilience in response to stressful events associated with military service. Thus far, researchers have conducted analyses of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 with military populations (De La Rosa et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2011; Prosek & Ponder, 2021), but not yet with first responders. While there are some overlapping characteristics between the populations, there are also unique differences that warrant research with discrete sampling (SAMHSA, 2018). In light of the importance of resilience as a protective factor for mental health among first responders, the purpose of the current study was to confirm the reliability and validity of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 when utilized with this population. In the current study, we hypothesized the measures would perform similarly among first responders and if so, the RSES-4 would offer counselors a brief assessment option in clinical practice that is both reliable and valid.

Method

Participants

Participants in the current non-probability, purposive sample study were first responders (N = 238) seeking clinical treatment at an outpatient, mental health nonprofit organization in the Southwestern United States. Participants’ mean age was 37.53 years (SD = 10.66). The majority of participants identified as men (75.2%; n = 179), with women representing 24.8% (n = 59) of the sample. In terms of race and ethnicity, participants identified as White (78.6%; n = 187), Latino/a (11.8%; n = 28), African American or Black (5.5%; n = 13), Native American (1.7%; n = 4), Asian American (1.3%; n = 3), and multiple ethnicities (1.3%; n = 3). The participants identified as first responders in three main categories: LEO (34.9%; n = 83), EMT (28.2%; n = 67), and fire rescue (25.2%; n = 60). Among the first responders, 26.9% reported previous military affiliation. As part of the secondary analysis, we utilized a subsample (n = 190) that was reflective of the larger sample (see Table 1).

Procedure

The data for this study were collected between 2015–2020 as part of the routine clinical assessment procedures at a nonprofit organization serving military service members, first responders, frontline health care workers, and their families. The agency representatives conduct clinical assessments with clients at intake, Session 6, Session 12, and Session 18 or when clinical services are concluded. We consulted with the second author’s Institutional Review Board, which determined the research as exempt, given the de-identified, archival nature of the data. For inclusion in this analysis, data needed to represent first responders, ages 18 or older, with a completed RSES-22 at intake. The RSES-4 are four questions within the RSES-22 measure; therefore, the participants did not have to complete an additional measure. For the secondary analysis, data from participants who also completed other mental health measures at intake were also included (see Measures).

Table 1

Demographics of Sample

| Characteristic |

Sample 1

(N = 238) |

Sample 2

(n = 190) |

| Age (Years) |

|

|

| Mean |

37.53 |

37.12 |

| Median |

35.50 |

35.00 |

| SD |

10.66 |

10.30 |

| Range |

46 |

45 |

| Time in Service (Years) |

|

|

| Mean |

11.62 |

11.65 |

| Median |

10.00 |

10.00 |

| SD |

9.33 |

9.37 |

| Range |

41 |

39 |

|

n (%) |

| First Responder Type |

|

|

Emergency Medical

Technicians |

67 (28.2%) |

54 (28.4%) |

| Fire Rescue |

60 (25.2%) |

45 (23.7%) |

| Law Enforcement |

83 (34.9%) |

72 (37.9%) |

| Other |

9 (3.8%) |

5 (2.6%) |

| Two or more |

10 (4.2%) |

6 (3.2%) |

| Not reported |

9 (3.8%) |

8 (4.2%) |

| Gender |

|

|

| Women |

59 (24.8%) |

47 (24.7%) |

| Men |

179 (75.2%) |

143 (75.3%) |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

| African American/Black |

13 (5.5%) |

8 (4.2%) |

| Asian American |

3 (1.3%) |

3 (1.6%) |

| Latino(a)/Hispanic |

28 (11.8%) |

24 (12.6%) |

| Multiple Ethnicities |

3 (1.3%) |

3 (1.6%) |

| Native American |

4 (1.7%) |

3 (1.6%) |

| White |

187 (78.6%) |

149 (78.4%) |

Note. Sample 2 is a subset of Sample 1. Time in service for Sample 1, n = 225;

time in service for Sample 2, n = 190.

Measures

Response to Stressful Experiences Scale

The Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-22) is a 22-item measure to assess dimensions of resilience, including meaning-making, active coping, cognitive flexibility, spirituality, and self-efficacy (Johnson et al., 2011). Participants respond to the prompt “During and after life’s most stressful events, I tend to” on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all like me) to 4 (exactly like me). Total scores range from 0 to 88 in which higher scores represent greater resilience. Example items include see it as a challenge that will make me better, pray or meditate, and find strength in the meaning, purpose, or mission of my life. Johnson et al. (2011) reported the RSES-22 demonstrates good internal consistency (α = .92) and test-retest reliability (α = .87) among samples from military populations. Further, the developers confirmed convergent, discriminant, concurrent, and incremental criterion validity (see Johnson et al., 2011). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .93.

Adapted Response to Stressful Experiences Scale

The adapted Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-4) is a 4-item measure to assess resilience as a unidimensional construct (De La Rosa et al., 2016). The prompt and Likert scale are consistent with the original RSES-22; however, it only includes four items: find a way to do what’s necessary to carry on, know I will bounce back, learn important and useful life lessons, and practice ways to handle it better next time. Total scores range from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. De La Rosa et al. (2016) reported acceptable internal consistency (α = .76–.78), test-retest reliability, and demonstrated criterion validity among multiple military samples. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .74.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a 9-item measure to assess depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks (Kroenke et al., 2001). Respondents rate the frequency of their symptoms on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Total scores range from 0 to 27, in which higher scores indicate increased severity of depressive symptoms. Example items include little interest or pleasure in doing things and feeling tired or having little energy. Kroenke et al. (2001) reported good internal consistency (α = .89) and established criterion and construct validity. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .88.

PTSD Checklist-5

The PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) is a 20-item measure for the presence of PTSD symptoms in the past month (Blevins et al., 2015). Participants respond on a 5-point Likert scale indicating frequency of PTSD-related symptoms from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Total scores range from 0 to 80, in which higher scores indicate more severity of PTSD-related symptoms. Example items include repeated, disturbing dreams of the stressful experience and trouble remembering important parts of the stressful experience. Blevins et al. (2015) reported good internal consistency (α = .94) and determined convergent and discriminant validity. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .93.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) is a 7-item measure to assess for anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks (Spitzer et al., 2006). Participants rate the frequency of the symptoms on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Total scores range from 0 to 21 with higher scores indicating greater severity of anxiety symptoms. Example items include not being able to stop or control worrying and becoming easily annoyed or irritable. Among patients from primary care settings, Spitzer et al. (2006) determined good internal consistency (α = .92) and established criterion, construct, and factorial validity. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .91.

Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised

The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R) is a 4-item measure to assess suicidality (Osman et al., 2001). Each item assesses a different dimension of suicidality: lifetime ideation and attempts, frequency of ideation in the past 12 months, threat of suicidal behaviors, and likelihood of suicidal behaviors (Gutierrez et al., 2001). Total scores range from 3 to 18, with higher scores indicating more risk of suicide. Example items include How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year? and How likely is it that you will attempt suicide someday? In a clinical sample, Osman et al. (2001) reported good internal consistency (α = .87) and established criterion validity. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .85.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 and SPSS Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) version 26.0. We examined the dataset for missing values, replacing 0.25% (32 of 12,836 values) of data with series means. We reviewed descriptive statistics of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 scales. We determined multivariate normality as evidenced by skewness less than 2.0 and kurtosis less than 7.0 (Dimitrov, 2012). We assessed reliability for the scales by interpreting Cronbach’s alphas and inter-item correlations to confirm internal consistency.

We conducted two separate confirmatory factor analyses to determine the model fit and factorial validity of the 22-item measure and adapted 4-item measure. We used several indices to conclude model fit: minimum discrepancy per degree of freedom (CMIN/DF) and p-values, root mean residual (RMR), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). According to Dimitrov (2012), values for the CMIN/DF < 2.0,p > .05, RMR < .08, GFI > .90, CFI > .90, TLI > .90, and RMSEA < .10 provide evidence of a strong model fit. To determine criterion validity, we assessed a subsample of participants (n = 190) who had completed the RSES-22, RSES-4, and four other psychological measures (i.e., PHQ-9, PCL-5, GAD-7, and SBQ-R). We determined convergent validity by conducting bivariate correlations between the RSES-22 and RSES-4.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

We computed means, standard deviations, 95% confidence interval (CI), and score ranges for the RSES-22 and RSES-4 (Table 2). Scores on the RSES-22 ranged from 19–88. Scores on the RSES-4 ranged from 3–16. Previous researchers using the RSES-22 on military samples reported mean scores of 57.64–70.74 with standard deviations between 8.15–15.42 (Johnson et al., 2011; Prosek & Ponder, 2021). In previous research of the RSES-4 with military samples, mean scores were 9.95–11.20 with standard deviations between 3.02–3.53(De La Rosa et al., 2016; Prosek & Ponder, 2021).

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics for RSES-22 and RSES-4

| Variable |

M |

SD |

95% CI |

Score Range |

| RSES-22 scores |

60.12 |

13.76 |

58.52, 61.86 |

19–88 |

| RSES-4 scores |

11.66 |

2.62 |

11.33, 11.99 |

3–16 |

Note. N = 238. RSES-22 = Response to Stressful Experiences Scale 22-item; RSES-4 = Response

to Stressful Experiences Scale 4-item adaptation.

Reliability Analyses

To determine the internal consistency of the resiliency measures, we computed Cronbach’s alphas. For the RSES-22, we found strong evidence of inter-item reliability (α = .93), which was consistent with the developers’ estimates (α = .93; Johnson et al., 2011). For the RSES-4, we assessed acceptable inter-item reliability (α = .74), which was slightly lower than previous estimates (α = .76–.78; De La Rosa et al., 2016). We calculated the correlation between items and computed the average of all the coefficients. The average inter-item correlation for the RSES-22 was .38, which falls within the acceptable range (.15–.50). The average inter-item correlation for the RSES-4 was .51, slightly above the acceptable range. Overall, evidence of internal consistency was confirmed for each scale.

Factorial Validity Analyses

We conducted two confirmatory factor analyses to assess the factor structure of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 for our sample of first responders receiving mental health services at a community clinic (Table 3). For the RSES-22, a proper solution converged in 10 iterations. Item loadings ranged between .31–.79, with 15 of 22 items loading significantly ( > .6) on the latent variable. It did not meet statistical criteria for good model fit: χ2 (209) = 825.17, p = .000, 90% CI [0.104, 0.120]. For the RSES-4, a proper solution converged in eight iterations. Item loadings ranged between .47–.80, with three of four items loading significantly ( > .6) on the latent variable. It met statistical criteria for good model fit: χ2 (2) = 5.89, p = .053, 90% CI [0.000, 0.179]. The CMIN/DF was above the suggested < 2.0 benchmark; however, the other fit indices indicated a model fit.

Table 3

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Fit Indices for RSES-22 and RSES-4

| Variable |

df |

χ2 |

CMIN/DF |

RMR |

GFI |

CFI |

TLI |

RMSEA |

90% CI |

| RSES-22 |

209 |

825.17/.000 |

3.95 |

.093 |

.749 |

.771 |

0.747 |

.112 |

0.104, 0.120 |

| RSES-4 |

2 |

5.89/.053 |

2.94 |

.020 |

.988 |

.981 |

0.944 |

.091 |

0.000, 0.179 |

Note. N = 238. RSES-22 = Response to Stressful Experiences Scale 22-item; RSES-4 = Response to Stressful Experiences Scale 4-item adaptation; CMIN/DF = Minimum Discrepancy per Degree of Freedom; RMR = Root Mean Square Residual;

GFI = Goodness-of-Fit Index; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA = Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation.

Criterion and Convergent Validity Analyses

To assess for criterion validity of the RSES-22 and RSES-4, we conducted correlational analyses with four established psychological measures (Table 4). We utilized a subsample of participants (n = 190) who completed the PHQ-9, PCL-5, GAD-7, and SBQ-R at intake. Normality of the data was not a concern because analyses established appropriate ranges for skewness and kurtosis (± 1.0). The internal consistency of the RSES-22 (α = .93) and RSES-4 (α = .77) of the subsample was comparable to the larger sample and previous studies. The RSES-22 and RSES-4 related to the psychological measures of distress in the expected direction, meaning measures were significantly and negatively related, indicating that higher resiliency scores were associated with lower scores of symptoms associated with diagnosable mental health disorders (i.e., post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and suicidal behavior). We verified convergent validity with a correlational analysis of the RSES-22 and RSES-4, which demonstrated a significant and positive relationship.

Table 4

Criterion and Convergent Validity of RSES-22 and RSES-4

|

M (SD) |

Cronbach’s α |

RSES-22 |

PHQ-9 |

PCL-5 |

GAD-7 |

SBQ-R |

| RSES-22 |

60.16 (14.17) |

.93 |

— |

−.287* |

−.331* |

−.215* |

−.346* |

| RSES-4 |

11.65 (2.68) |

.77 |

.918 |

−.290* |

−.345* |

−.220* |

−.327* |

Note. n = 190. RSES-22 = Response to Stressful Experiences Scale 22-item; RSES-4 = Response to Stressful Experiences Scale 4-item adaptation; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9;

PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist-5; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; SBQ-R = Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised.

*p < .01.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to validate the factor structure of the RSES-22 and the abbreviated RSES-4 with a first responder sample. Aggregated means were similar to those in the articles that validated and normed the measures in military samples (De La Rosa et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2011; Prosek & Ponder, 2021). Additionally, the internal consistency was similar to previous studies. In the original article, Johnson et al. (2011) proposed a five-factor structure for the RSES-22, which was later established as a unidimensional assessment after further exploratory factor analysis (De La Rosa et al., 2016). Subsequently, confirmatory factor analyses with a treatment-seeking veteran population revealed that the RSES-22 demonstrated unacceptable model fit, whereas the RSES-4 demonstrated a good model fit (Prosek & Ponder, 2021). In both samples, the RSES-4 GFI, CFI, and TLI were all .944 or higher, whereas the RSES-22 GFI, CFI, and TLI were all .771 or lower. Additionally, criterion and convergent validity as measured by the PHQ-9, PCL-5, and GAD-7 in both samples were extremely close. Similarly, in this sample of treatment-seeking first responders, confirmatory factor analyses indicated an inadequate model fit for the RSES-22 and a good model fit for the RSES-4. Lastly, convergent and criterion validity were established with correlation analyses of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 with four other standardized assessment instruments (i.e., PHQ-9, PCL-5, GAD-7, SBQ-R). We concluded that among the first responder sample, the RSES-4 demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties, as well as criterion and convergent validity with other mental health variables (i.e., post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and suicidal behavior).

Implications for Clinical Practice

First responders are a unique population and are regularly exposed to trauma (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014; Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2010). Although first responders could potentially benefit from espousing resilience, they are often hesitant to seek mental health services (Crowe et al., 2017; Jones, 2017). The RSES-22 and RSES-4 were originally normed with military populations. The results of the current study indicated initial validity and reliability among a first responder population, revealing that the RSES-4 could be useful for counselors in assessing resilience.

It is important to recognize that first responders have perceived coping with traumatic stress as an individual process (Crowe et al., 2017) and may believe that seeking mental health services is counter to the emotional and physical training expectations of the profession (Crowe et al., 2015). Therefore, when first responders seek mental health care, counselors need to be prepared to provide culturally responsive services, including population-specific assessment practices and resilience-oriented care.

Jones (2017) encouraged a comprehensive intake interview and battery of appropriate assessments be conducted with first responder clients. Counselors need to balance the number of intake questions while responsibly assessing for mental health comorbidities such as post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and suicidality. The RSES-4 provides counselors a brief, yet targeted assessment of resilience.

Part of what cultural competency entails is assessing constructs (e.g., resilience) that have been shown to be a protective factor against PTSD among first responders (Klimley et al., 2018). Since the items forming the RSES-4 were developed to highlight the positive characteristics of coping (Johnson et al., 2011), rather than a deficit approach, this aligns with the grounding of the counseling profession. It is also congruent with first responders’ perceptions of resilience. Indeed, in a content analysis of focus group interviews with first responders, participants defined resilience as a positive coping strategy that involves emotional regulation, perseverance, personal competence, and physical fitness (Crowe et al., 2017).

The RSES-4 is a brief, reliable, and valid measure of resilience with initial empirical support among a treatment-seeking first responder sample. In accordance with the ACA (2014) Code of Ethics, counselors are to administer assessments normed with the client population (E.8.). Thus, the results of the current study support counselors’ use of the measure in practice. First responder communities are facing unprecedented work tasks in response to COVID-19. Subsequently, their mental health might suffer (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020) and experts have recommended promoting resilience as a protective factor for combating the negative mental health consequences of COVID-19 (Chen & Bonanno, 2020). Therefore, the relevance of assessing resilience among first responder clients in the current context is evident.

Limitations and Future Research

This study is not without limitations. The sample of first responders was homogeneous in terms of race, ethnicity, and gender. Subsamples of first responders (i.e., LEO, EMT, fire rescue) were too small to conduct within-group analyses to determine if the factor structure of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 would perform similarly. Also, our sample of first responders included two emergency dispatchers. Researchers reported that emergency dispatchers should not be overlooked, given an estimated 13% to 15% of emergency dispatchers experience post-traumatic symptomatology (Steinkopf et al., 2018). Future researchers may develop studies that further explore how, if at all, emergency dispatchers are represented in first responder research.

Furthermore, future researchers could account for first responders who have prior military service. In a study of LEOs, Jetelina et al. (2020) found that participants with military experience were 3.76 times more likely to report mental health concerns compared to LEOs without prior military affiliation. Although we reported the prevalence rate of prior military experience in our sample, the within-group sample size was not sufficient for additional analyses. Finally, our sample represented treatment-seeking first responders. Future researchers may replicate this study with non–treatment-seeking first responder populations.

Conclusion

First responders are at risk for sustaining injuries, experiencing life-threatening events, and witnessing harm to others (Lanza et al., 2018). The nature of their exposure can be repeated and cumulative over time (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014), indicating an increased risk for post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, as well as suicidal behavior (Jones et al., 2018). Resilience is a promising protective factor that promotes wellness and healthy coping among first responders (Wild et al., 2020), and counselors may choose to routinely measure for resilience among first responder clients. The current investigation concluded that among a sample of treatment-seeking first responders, the original factor structure of the RSES-22 was unstable, although it demonstrated good reliability and validity. The adapted version, RSES-4, demonstrated good factor structure while also maintaining acceptable reliability and validity, consistent with studies of military populations (De La Rosa et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2011; Prosek & Ponder, 2021). The RSES-4 provides counselors with a brief and strength-oriented option for measuring resilience with first responder clients.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Antony, J., Brar, R., Khan, P. A., Ghassemi, M., Nincic, V., Sharpe, J. P., Straus, S. E., & Tricco, A. C. (2020). Interventions for the prevention and management of occupational stress injury in first responders: A rapid overview of reviews. Systematic Reviews, 9(121), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01367-w

Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

Burnett, H. J., Jr. (2017). Revisiting the compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction, and resilience connection among CISM responders. Journal of Police Emergency Response, 7(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017730857

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, June 30). Coping with stress. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/managing-stress-anxiety.html

Chen, S., & Bonanno, G. A. (2020). Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: A resilience perspective. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S51–S54. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000685

Christopher, M. S., Hunsinger, M., Goerling, R. J., Bowen, S., Rogers, B. S., Gross, C. R., Dapolonia, E., & Pruessner, J. C. (2018). Mindfulness-based resilience training to reduce health risk, stress reactivity, and aggression among law enforcement officers: A feasibility and preliminary efficacy trial. Psychiatry Research, 264, 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.059

Crowe, A., Glass, J. S., Lancaster, M. F., Raines, J. M., & Waggy, M. R. (2015). Mental illness stigma among first responders and the general population. Journal of Military and Government Counseling, 3(3), 132–149. http://mgcaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/JMGC-Vol-3-Is-3.pdf

Crowe, A., Glass, J. S., Lancaster, M. F., Raines, J. M., & Waggy, M. R. (2017). A content analysis of psychological resilience among first responders. SAGE Open, 7(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017698530

De La Rosa, G. M., Webb-Murphy, J. A., & Johnston, S. L. (2016). Development and validation of a brief measure of psychological resilience: An adaptation of the Response to Stressful Experiences Scale. Military Medicine, 181(3), 202–208. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00037

Dimitrov, D. M. (2012). Statistical methods for validation of assessment scale data in counseling and related fields. American Counseling Association.

Donnelly, E. A., & Bennett, M. (2014). Development of a critical incident stress inventory for the emergency medical services. Traumatology, 20(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765613496646

Greinacher, A., Derezza-Greeven, C., Herzog, W., & Nikendei, C. (2019). Secondary traumatization in first responders: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1562840. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1562840

Gutierrez, P. M., Osman, A., Barrios, F. X., & Kopper, B. A. (2001). Development and initial validation of the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 77(3), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA7703_08

Jetelina, K. K., Mosberry, R. J., Gonzalez, J. R., Beauchamp, A. M., & Hall, T. (2020). Prevalence of mental illnesses and mental health care use among police officers. JAMA Network Open, 3(10), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19658

Johnson, D. C., Polusny, M. A., Erbes, C. R., King, D., King, L., Litz, B. T., Schnurr, P. P., Friedman, M., Pietrzak, R. H., & Southwick, S. M. (2011). Development and initial validation of the Response to Stressful Experiences Scale. Military Medicine, 176(2), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-10-00258

Jones, S. (2017). Describing the mental health profile of first responders: A systematic review. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 23(3), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390317695266

Jones, S., Nagel, C., McSweeney, J., & Curran, G. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of psychiatric symptoms among first responders in a Southern state. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32(6), 828–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2018.06.007

Joyce, S., Tan, L., Shand, F., Bryant, R. A., & Harvey, S. B. (2019). Can resilience be measured and used to predict mental health symptomology among first responders exposed to repeated trauma? Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61(4), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001526

Kleim, B., & Westphal, M. (2011). Mental health in first responders: A review and recommendation for prevention and intervention strategies. Traumatology, 17(4), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765611429079

Klimley, K. E., Van Hasselt, V. B., & Stripling, A. M. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder in police, firefighters, and emergency dispatchers. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 43, 33–44.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.08.005

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Lanza, A., Roysircar, G., & Rodgers, S. (2018). First responder mental healthcare: Evidence-based prevention, postvention, and treatment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(3), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000192

Lee, J.-S., Ahn, Y.-S., Jeong, K.-S. Chae, J.-H., & Choi, K.-S. (2014). Resilience buffers the impact of traumatic events on the development of PTSD symptoms in firefighters. Journal of Affective Disorders, 162, 128–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.031

Lewis, G. B., & Pathak, R. (2014). The employment of veterans in state and local government service. State and Local Government Review, 46(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X14537835

McCanlies, E. C., Gu, J. K., Andrew, M. E., Burchfiel, C. M., & Violanti, J. M. (2017). Resilience mediates the relationship between social support and post-traumatic stress symptoms in police officers. Journal of Emergency Management, 15(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2017.0319

National Institute of Mental Health. (2017). Post-traumatic stress disorder. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd.shtml

Osman, A., Bagge, C. L., Gutierrez, P. M., Konick, L. C., Kopper, B. A., & Barrios, F. X. (2001). The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire–revised (SBQ-R): Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment, 8(4), 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/107319110100800409

Prosek, E. A., & Ponder, W. N. (2021). Validation of the Adapted Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-4) among veterans [Manuscript submitted for publication].

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder (The GAD-7). Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Steinkopf, B., Reddin, R. A., Black, R. A., Van Hasselt, V. B., & Couwels, J. (2018). Assessment of stress and resiliency in emergency dispatchers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 33(4), 398–411.

https://doi.org /10.1007/s11896-018-9255-3

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018, May). First responders: Behavioral health concerns, emergency response, and trauma. Disaster Technical Assistance Center Supplemental Research Bulletin. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/dtac/supplementalresearchbulletin-firstresponders-may2018.pdf

Weiss, D. S., Brunet, A., Best, S. R., Metzler, T. J., Liberman, A., Pole, N., Fagan, J. A., & Marmar, C. R. (2010). Frequency and severity approaches to indexing exposure to trauma: The Critical Incident History Questionnaire for police officers. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(6), 734–743.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20576

White, B., Driver, S., & Warren, A. M. (2010). Resilience and indicators of adjustment during rehabilitation from a spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018451

Wild, J., El-Salahi, S., Degli Esposti, M., & Thew, G. R. (2020). Evaluating the effectiveness of a group-based resilience intervention versus psychoeducation for emergency responders in England: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 15(11), e0241704. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241704

Windle, G., Bennett, K. M., & Noyes, J. (2011). A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9, Article 8, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-8

Warren N. Ponder, PhD, is Director of Outcomes and Evaluation at One Tribe Foundation. Elizabeth A. Prosek, PhD, NCC, LPC, is an associate professor at Penn State University. Tempa Sherrill, MS, LPC-S, is the founder of Stay the Course and a volunteer at One Tribe Foundation. Correspondence may be addressed to Warren N. Ponder, 855 Texas St., Suite 105, Fort Worth, TX 76102, warren@1tribefoundation.org.

Nov 29, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 4

Michael T. Kalkbrenner, Edward S. Neukrug

The primary aim of this study was to cross-validate the Revised Fit, Stigma, & Value (FSV) Scale, a questionnaire for measuring barriers to counseling, using a stratified random sample of adults in the United States. Researchers also investigated the percentage of adults living in the United States that had previously attended counseling and examined demographic differences in participants’ sensitivity to barriers to counseling. The results of a confirmatory factor analysis supported the factorial validity of the three-dimensional FSV model. Results also revealed that close to one-third of adults in the United States have attended counseling, with women attending counseling at higher rates (35%) than men (28%). Implications for practice, including how professional counselors, counseling agencies, and counseling professional organizations can use the FSV Scale to appraise and reduce barriers to counseling among prospective clients are discussed.

Keywords: barriers to counseling, FSV Scale, confirmatory factor analysis, attendance in counseling, factorial validity

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental health disorders are widespread, with over 300 million people struggling with depressive disorders, 260 million living with anxiety disorders, and hundreds of millions having any of a number of other mental health disorders (WHO, 2017, 2018). The symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders can be dire and include hopelessness, sadness, sleep disturbances, motivational impairment, relationship difficulties, and suicide in the most severe cases (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Worldwide, one in four individuals will be impacted by a mental health disorder in their lifetime, which leads to over a trillion dollars in lost job productivity each year (WHO, 2018). In the United States, approximately one in five adults has a diagnosable mental illness each year, and about 20% of children and teens will develop a mental disorder that is disabling (Centers for Disease Control, 2018).

Substantial increases in mental health distress among the U.S. and global populations have impacted the clinical practice of counseling practitioners who work in a wide range of settings, including schools, social service agencies, and colleges (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017; Twenge, Joiner, Rogers, & Martin, 2017). Identifying the percentage of adults in the United States who attend counseling, as well as the reasons why many do not, can help counselors develop strategies that can make counseling more inviting and, ultimately, relieve struggles that people face. Although perceived stigma and not having health insurance have been associated with reticence to seek counseling (Han, Hedden, Lipari, Copello, & Kroutil, 2014; Norcross, 2010; University of Phoenix, 2013), the literature on barriers to counseling among people in the United States is sparse. Appraising barriers to counseling using a psychometrically sound instrument is the first step toward counteracting such barriers and making counseling more inviting for prospective clients. Evaluating barriers to counseling, with special attention to cultural differences, has the potential to help understand differences in attendance to counseling and can help develop mechanisms that promote counseling for all individuals. This is particularly important as research has shown that there are differences in help-seeking behavior as a function of gender identity and ethnicity (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, Narrow, Grant, & Hasin, 2008).

Attendance in Counseling by Gender and Ethnicity

Previous investigations on attendance in counseling indicated that 15–38% of adults in the United States had sought counseling at some point in their lives (Han et al., 2014; University of Phoenix, 2013), with discrepancies in counselor-seeking behavior found as a function of gender and ethnicity (Han et al., 2014; Lindinger-Sternart, 2015). For instance, women are more likely to seek counseling compared to men (Abrams, 2014; J. Kim, 2017). In addition, individuals who identify as White tend to seek personal counseling at higher rates compared to those who identify with other ethnic backgrounds (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Seidler, Rice, River, Oliffe, & Dhillon, 2017). Parent, Hammer, Bradstreet, Schwartz, and Jobe (2018) examined the intersection of gender, race, ethnicity, and poverty with help-seeking behavior and found the income-to-poverty ratio to be positively related to help-seeking for White males and negatively associated for African American males. In other words, as White males gained in income, they were more likely to seek counseling, whereas the opposite was true for males who identified as African American (Parent et al., 2018).

Barriers to Mental Health Treatment and Attendance in Counseling

Despite the fact that large numbers of individuals in the United States and worldwide will develop a mental disorder in their lifetime, two-thirds of them will avoid or do not have access to mental health treatment (WHO, 2018). In wealthier countries, there is one mental health worker per 2,000 people (WHO, 2015); however, in poorer countries, this drops to 1 in 100,000, and such disparities need to be addressed (Hinkle, 2014; WHO, 2015). Although the lack of attendance in counseling and related services in poorer countries is explained by lack of services, in the United States and other wealthy countries, the availability of mental health services is relatively high, and the lack of attendance is usually explained by other reasons (Neukrug, Kalkbrenner, & Griffith, 2017; WHO, 2015). Research on the lack of attendance in counseling by the general public shows adults in the United States might be reticent to seek counseling because of perceived stigma, financial burden, lack of health insurance, uncertainty about how to find a counselor, and suspicion that counseling will not be helpful (Han et al., 2014; Norcross, 2010; University of Phoenix, 2013).

Appraising Barriers to Counseling

The quantification and appraisal of barriers to counseling is a nuanced and complex construct to measure and has been previously assessed with populations of mental health professionals and with counseling students (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018; Kalkbrenner, Neukrug, & Griffith, in press; Neukrug et al., 2017). Knowing that personal counseling is a valuable self-care strategy for mental health professionals (Whitfield & Kanter, 2014), Neukrug et al. (2017) developed the original version of the Fit, Stigma, & Value (FSV) Scale, which is comprised of three latent variables, or subscales, of barriers to counseling for human service professionals: fit (the degree to which one trusts the process of counseling), stigma (hesitation to seek counseling because of feelings of embarrassment), and value (the extent to which a respondent thinks that attending personal counseling will be beneficial). Kalkbrenner et al. (in press) extended and validated a revised version of the FSV Scale with a sample of professional counselors, and Kalkbrenner and Neukrug (2018) validated the Revised FSV Scale with a sample of counselor trainees. Although the FSV Scale appears to have utility for appraising barriers to counseling among mental health professionals (Neukrug et al., 2017; Kalkbrenner et al., in press) the factorial validity of the measure has only been tested with helping professionals and counseling students. The appraisal of barriers to seeking counseling among adults in the United States is an essential first step in understanding why prospective clients do, or do not, seek counseling. If validated, researchers and practitioners can potentially use the results of the Revised FSV Scale to aid in the early identification of specific barriers and to inform the development of interventions geared toward reducing barriers to counseling among adults in the United States. Thus, we sought to answer the following research questions (RQs): RQ 1: Is the three-dimensional hypothesized model of the Revised FSV scale confirmed with a stratified random sample of adults in the United States? RQ 2: To what extent do adults in the United States attend counseling? RQ 3: Are there demographic differences to the FSV barriers among adults in the United States?

Method

The psychometric properties of the Revised FSV Scale were tested with a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) based on structural equation modeling (RQ 1). Descriptive statistics were used to compute participants’ frequency of attendance in counseling (RQ 2). A factorial multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was computed to investigate demographic differences in respondents’ sensitivity to the FSV barriers (RQ 3). A minimum sample size of 320 (10 participants for each estimated parameter) was determined to be sufficient for computing a CFA (Mvududu & Sink, 2013). An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power to determine the sample size for the factorial MANOVA (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). Results revealed that a minimum sample size of 269 would provide an 80% power estimate (α = .05), with a moderate effect size, f 2 = 0.25 (Cohen, 1988).

Participants and Procedures

After obtaining IRB approval, an online sampling service (Qualtrics, 2018) was contracted to survey a stratified random sample (stratified by age, gender, and ethnicity) of the general U.S. population based on the 2016–2017 census data. A Qualtrics project management team generated a list of parameters and sample quota constraints for data collection. Once the researchers reviewed and confirmed these parameters, a project manager initiated the stratified random sampling procedure and data collection by sending an electronic link to the questionnaire to prospective participants. A pilot study was conducted using 41 participants and no formatting or imputation errors were found. Data collection for the main study was initiated and was completed in less than one week.

A total of 431 individuals responded to the survey. Of these, 21 responses were omitted because of missing data, yielding a useable sample of 410. Participants ranged in ages from 18 to 84 (M = 45,

SD = 15). The demographic profile included the following: 52% (n = 213) identified as female, 44%

(n = 181) as male, 0.5% (n = 2) as transgender, and 3.4% (n = 14) did not specify their gender. For ethnicity, 63% (n = 258) identified as White, 17% (n = 69) as Hispanic/Latinx, 12% (n = 49) as African American, 5% (n = 21) as Asian, 1% (n = 5) as American Indian or Alaska Native, 0.5% (n = 2) as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 1.5% (n = 6) did not specify their ethnicity. For highest degree completed, 1% (n = 5) held a doctoral degree, 7% (n = 29) held a master’s degree, 24% (n = 98) held a bachelor’s degree, 16% (n = 65) had completed an associate degree, 49% (n = 199) had a high school diploma, and 3% (n = 14) did not specify their highest level of education. Eighty-four percent (n = 343) of participants had health insurance at the time of data collection. The demographic profile of our sample is consistent with those found in recent surveys of the general U.S. population (Lumina Foundation, 2017; U.S. Census Bureau, 2017).

Instrumentation

Using the Qualtrics e-survey platform (Qualtrics, 2018), participants were asked to respond to a series of demographic questions as well as the Revised FSV Scale.

Demographic questionnaire. Participants responded to a series of demographic items about their age, ethnicity, gender, highest level of education completed, and if they had health insurance. They also were asked to indicate if they had ever recommended counseling to another person and if they had ever participated in at least one session of counseling as defined by the American Counseling Association (ACA) in the 20/20: Consensus Definition of Counseling: “counseling is a professional relationship that empowers diverse individuals, families, and groups to accomplish mental health, wellness, education, and career goals” (2010, para. 2).

The FSV Scale. The original version of the FSV Scale contained 32 items that comprise three subscales (Fit, Stigma, and Value) for appraising barriers to counselor seeking behavior (Neukrug et al., 2017). Kalkbrenner et al. (in press) developed and validated the Revised FSV Scale by reducing the number of items to 14 (of the original 32) and confirmed the same 3-factor structure of the scale. The Revised FSV Scale (see Table 1) was used in the present study for temporal validity, as it is more current and because it is likely to reduce respondent fatigue, because it is shorter than the original. The Fit subscale appraises the degree to which one trusts the process of counseling (e.g., item 11: “I couldn’t find a counselor who would understand me.”). The Stigma subscale measures respondents’ hesitation to seek counseling because of feelings of embarrassment (e.g., item 1: “My friends would think negatively of me.”). The Value scale reflects the extent to which a respondent thinks that attending personal counseling will be beneficial (e.g., item 8: “It is not an effective use of my time.”). For each item, respondents were prompted with the stem, “I am less likely to attend counseling because . . . ” and asked to rate each item on a Likert-type scale: 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neither agree or disagree), 4 (agree), or 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores designate a greater sensitivity to each barrier. Previous investigators demonstrated adequate to strong internal consistency reliability coefficients for the Revised FSV Scale: α = .82, α = .91, and α = .78, respectively (Kalkbrenner et al., in press) and α = .81, α = .87, and α = .77 (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018). Past investigators found validity evidence for the 3-dimensional factor structure of the original and revised versions of the FSV Scale through rigorous psychometric testing (factor analysis) with populations of human services professionals (Neukrug et al., 2017), professional counselors (Kalkbrenner et al., in press), and counseling students (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018).

Results

CFA

A review of skewness and kurtosis values (see Table 1) indicated that the 14 items on the revised FSV scale were largely within the acceptable range of a normal distribution (absolute value < 1; Field, 2013). Mahalanobis d2 indices showed no extreme multivariate outliers. An inter-item correlation matrix (see Table 2) was computed to investigate the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Inter-item correlations were favorable and ranged from r = 0.42 to r = 0.82 (see Table 2).

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics: The Revised Version of the FSV Scale (N = 410)

| Items |

M |

SD |

Skew |

Kurtosis |

| My friends would think negatively of me. (Stigma) |

2.27 |

1.18 |

0.63 |

-0.50 |

| It would suggest I am unstable. (Stigma) |

2.55 |

1.25 |

0.29 |

-0.97 |

| I would feel embarrassed. (Stigma) |

2.72 |

1.20 |

-0.02 |

-1.00 |

| It would damage my reputation. (Stigma) |

2.43 |

1.20 |

0.41 |

-0.78 |

| It would be of no benefit. (Value) |

2.46 |

1.20 |

0.39 |

-0.71 |

| I would feel badly about myself if I saw a counselor. (Stigma) |

2.35 |

1.13 |

0.45 |

-0.61 |

| The financial cost of participating is not worth the personal benefits. (Value) |

2.61 |

1.18 |

0.25 |

-0.68 |

| It is not an effective use of my time. (Value) |

2.40 |

1.16 |

0.45 |

-0.57 |

I couldn’t find a counselor with my theoretical orientation

(personal style of counseling). (Fit) |

2.42 |

1.12 |

0.62 |

-0.68 |

| I couldn’t find a counselor competent enough to work with me. (Fit) |

2.31 |

1.12 |

0.50 |

-0.47 |

| I couldn’t find a counselor who would understand me. (Fit) |

2.41 |

1.20 |

0.48 |

-0.66 |

| I don’t trust a counselor to keep my matters just between us. (Fit) |

2.50 |

1.21 |

0.33 |

-0.82 |

| Counseling is unnecessary because my problems will resolve naturally. (Value) |

2.56 |

1.31 |

0.22 |

-0.61 |

| I have had a bad experience with a previous counselor in the past. (Fit) |

2.34 |

1.17 |

0.44 |

-0.71 |

Table 2

Inter-Item Correlation Matrix

|

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q5 |

Q6 |

Q7 |

Q8 |

Q9 |

Q10 |

Q11 |

Q12 |

Q13 |

Q14 |

| Q1 |

1 |

0.70 |

0.64 |

0.72 |

0.54 |

0.63 |

0.53 |

0.57 |

0.57 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

0.53 |

0.47 |

0.53 |

| Q2 |

|

1 |

0.76 |

0.72 |

0.51 |

0.61 |

0.52 |

0.54 |

0.55 |

0.58 |

0.60 |

0.57 |

0.42 |

0.46 |

| Q3 |

|

|

1 |

0.68 |

0.51 |

0.64 |

0.54 |

0.53 |

0.53 |

0.55 |

0.58 |

0.57 |

0.50 |

0.43 |

| Q4 |

|

|

|

1 |

0.62 |

0.68 |

0.55 |

0.59 |

0.58 |

0.61 |

0.63 |

0.61 |

0.51 |

0.53 |

| Q5 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.67 |

0.58 |

0.69 |

0.52 |

0.59 |

0.59 |

0.48 |

0.57 |

0.49 |

| Q6 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.58 |

0.68 |

0.59 |

0.68 |

0.69 |

0.60 |

0.56 |

0.48 |

| Q7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.72 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

0.57 |

0.58 |

0.59 |

0.53 |

| Q8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.64 |

0.66 |

0.68 |

0.61 |

0.64 |

0.54 |

| Q9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.71 |

0.71 |

0.61 |

0.56 |

0.57 |

| Q10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.82 |

0.65 |

0.56 |

0.56 |

| Q11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.65 |

0.52 |

0.58 |

| Q12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.57 |

0.52 |

| Q13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

0.44 |

| Q14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

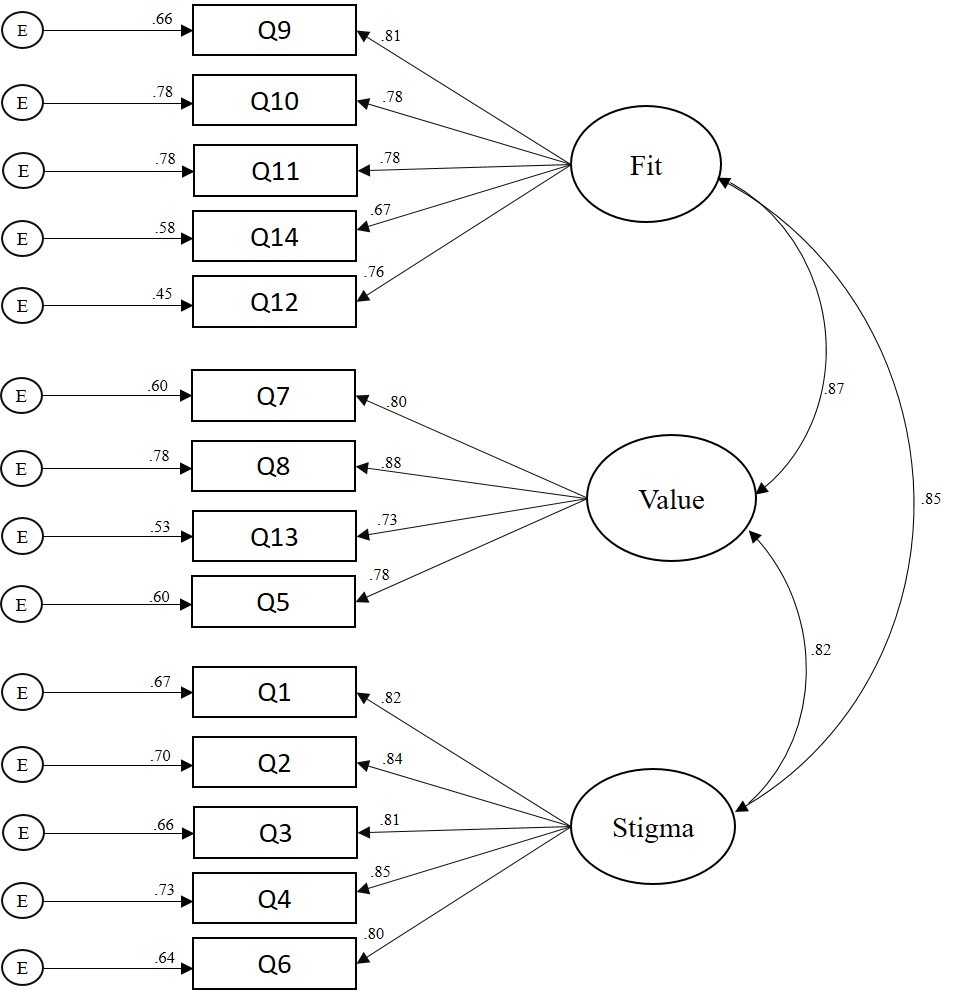

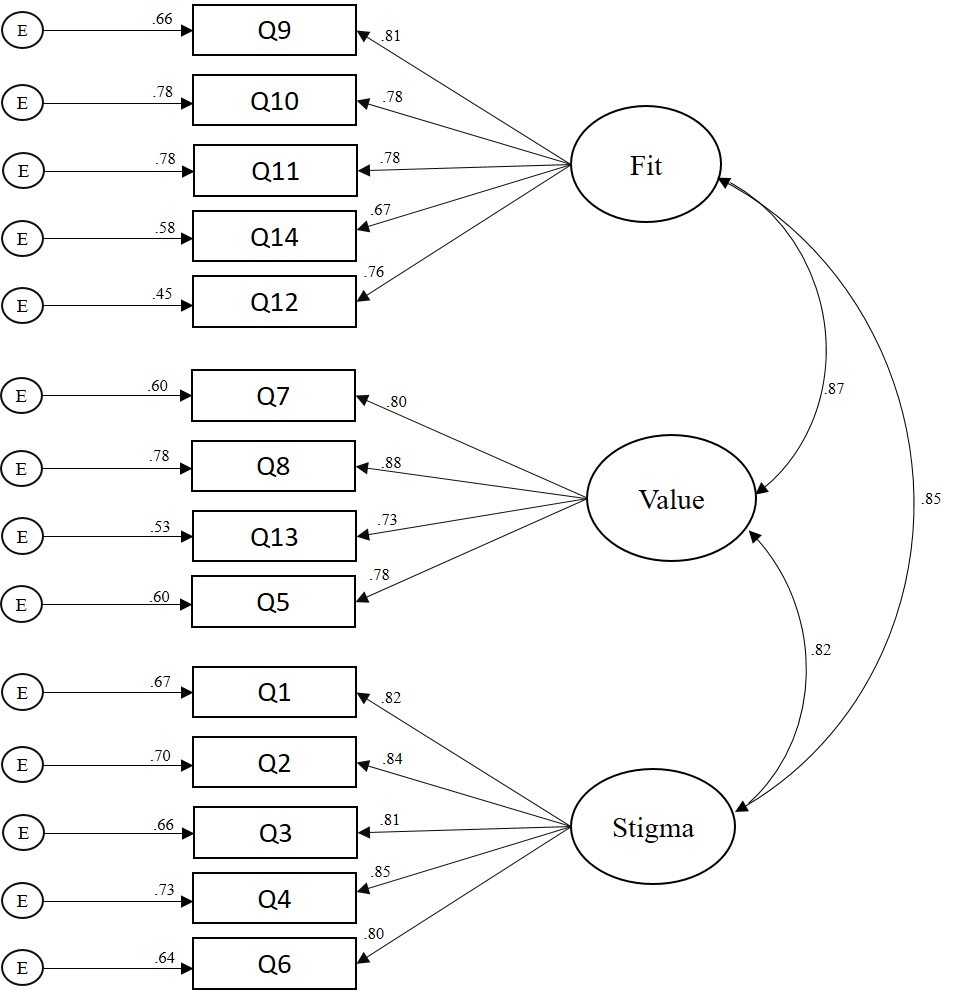

A CFA based on structural equation modeling was computed using IBM SPSS Amos version 25 to test the psychometric properties of the revised 14-item scale with adults in the United States (RQ1). A number of goodness-of-fit (GOF) indices recommended by Byrne (2016) were investigated to determine model fit. The Chi Square CMIN absolute fit index was statistically significant: χ2 (74) = 3.54, p < 0.001. More suitable GOF indices for large sample sizes (N > 200) were examined and revealed adequate model fit: comparative fit index (CFI = .96); root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = .07); 90% confidence interval [.06, .08]; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR = .038); incremental fit index (IFI = .96); and normed fit index (NFI = .94). Collectively, the GOF indices above demonstrated adequate model fit based on the guidelines provided by Byrne. The path model with standardized coefficients is displayed in Figure 1. Tests of internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) revealed strong reliability coefficients for all three FSV subscales: α = .90, α = .91, and α = .87, respectively. An investigation of the path model coefficients (see Figure 1) revealed a moderate to strong association between the FSV barriers. Consequently, researchers computed a follow-up CFA to test if a single-factor model solution for the FSV Scale was a better fit with the data. Results revealed a poor model fit for the single-factor solution, suggesting that retaining the 3-factor model was appropriate for the data.

Figure 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Path Model (N = 410)

Figure 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Path Model (N = 410)

Frequency and Multivariate Analyses

Of the 374 participants who responded to the item regarding whether they had previously attended counseling, 32% (n = 121) indicated they had. A total of 362 participants specified both their gender and past attendance in counseling. Females’ (n = 199) rate of attendance in counseling was 35% (n = 70) and males’ (n = 163) rate of attendance in counseling was 28% (n = 45). Eleven percent

(n = 45) of participants were attending counseling at the time of data collection.

A factorial 2 (gender) X 2 (attendance in counseling) X 2 (ethnicity) MANOVA was computed to examine demographic differences in participants’ sensitivity to barriers to counseling. All three independent variables had two levels: gender (male or female), attendance in counseling (no previous attendance in counseling or previous attendance in counseling), and ethnicity (White or non-White). Based on the recommendations of Kaneshiro, Geling, Gellert, and Millar (2011), the second level of the ethnicity independent variable, non-White, was aggregated by merging all participants who did not identify as White; this ensured comparable groups for statistical analyses. The dependent variables consisted of respondents’ composite scores on each of the three FSV barriers. Because we were interested in investigating all significant main effects and interaction effects across the univariate and multivariate nature of the data, both MANOVA and follow-up univariate ANOVAs were computed (Field, 2013). Bonferroni corrections were applied to control for the familywise error rate.

A significant main effect emerged for gender: F = (7, 354) = 4.73, p = 0.003, Wilks’ Λ = 0.96, η2p = 0.04. The univariate ANOVAs (see Table 3) revealed significant main effects for all three FSV barriers:

Fit: [F = (7, 354) = 6.26, p = 0.013, η2p = 0.02]; Stigma: [F = (7, 354) = 13.71, p < 0.001, η2p = .04]; and

Value: [F = (7, 354) = 5.52, p = 0.02, η2p = .02]. Males (M = 2.56, M = 2.73, M = 2.60) scored higher than females (M = 2.25, M = 2.24, M = 2.23) on Fit, Stigma, and Value, respectively. A significant multivariate main effect also emerged for attendance in counseling: F = (7, 354) = 3.80, p = 0.01, Wilks’ Λ = 0.97, η2p = 0.031. The univariate ANOVA revealed that participants who had not attended counseling (M = 2.60) scored higher than participants who had attended counseling (M = 2.30) on the Value barrier: F = (7, 354) = 4.65, p = 0.03, η2p = 0.01. There were no other statistically significant main effects or any interaction effects (see Table 3). That is, there were no other significant group differences in respondents’ sensitivity to the FSV barriers by gender, attendance in counseling, or ethnicity.

Discussion

The primary aim of the present study was to validate the revised version of the FSV Scale with adults in the United States. Researchers also investigated the percentage of adults that have attended counseling and examined demographic differences in participants’ sensitivity to barriers to counseling. Frequency analyses revealed that 32% of our sample had attended at least one session of personal counseling, and among those who did, females reported a higher rate of attendance (35%) than males (28%). At the time of data collection, 11% of participants were seeing a counselor. Our findings are largely consistent with previous investigations that suggested 15–38% of adults in the United States had sought counseling at some point in their lives (Hann et al., 2014; University of Phoenix, 2013).

Table 3

Demographic Differences in Sensitivity to Barriers to Counseling

2 (gender) X 2 (attendance in counseling) X 2 (ethnicity) Analysis of Variance

| Independent Variable Barrier |

F |

Sig. |

Partial Eta Squared |

| Gender |

*Fit |

6.26 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

|

|

| **Stigma |

13.71 |

0.00 |

0.04 |

|

|

| *Value |

5.52 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

|

|

| Ethnicity |

Fit |

0.34 |

0.56 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Stigma |

0.00 |

0.96 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Value |

0.11 |

0.74 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Attendance in Counseling |

Fit |

0.69 |

0.41 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Stigma |

0.01 |

0.93 |

0.00 |

|

|

| *Value |

4.65 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

|

|

| Gender X Ethnicity |

Fit |

0.00 |

0.96 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Stigma |

0.12 |

0.73 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Value |

0.14 |

0.71 |

0.01 |

|

|

| Gender X Counseling |

Fit |

1.38 |

0.24 |

0.01 |

|

|

| Stigma |

3.00 |

0.08 |

0.01 |

|

|

| Value |

1.32 |

0.25 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Ethnicity X Counseling |

Fit |

0.07 |

0.79 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Stigma |

0.00 |

0.98 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Value |

0.21 |

0.65 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Gender X Ethnicity X Counseling |

Fit |

0.81 |

0.37 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Stigma |

1.19 |

0.28 |

0.00 |

|

|

| Value |

0.24 |

0.62 |

0.00 |

|

|

df = (1, 354) Note: 0.00 denotes values < 0.01. *Indicates statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level (2-tailed). ** Indicates statistical significance at the p < 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Similar to previous literature on attendance in counseling and congruent with gender theory (Levant, Wimer, & Williams, 2011; Seidler et al., 2017; Vogel, Heimerdinger-Edwards, Hammer, & Hubbard, 2011), we found that males were less likely to seek counseling and were particularly susceptible to the Stigma, Fit, and Value barriers when compared to females. Susceptibility to the Stigma barrier suggests that men might be less likely to attend counseling because of feelings of shame or embarrassment (Cheng, Kwan, & Sevig, 2013; Cheng, Wang, McDermott, Kridel, & Rislin, 2018; J. E. Kim, Saw, & Zane, 2015). Males also reported a higher sensitivity to the Fit and Value barriers as compared to women, suggesting they might place less worth on the anticipated benefits of counseling, and if they were to enter counseling, they may be particularly concerned about finding a counselor with whom they are compatible. It is possible that men’s sensitivity to all FSV barriers may simply be related to their underutilization of counseling services when compared to women, although other explanations also might be plausible.

Consistent with Kalkbrenner et al. (in press), we found that independent of gender, participants who had not attended at least one session of personal counseling placed less value on its potential benefits as compared to those who had attended counseling. This finding suggests that to some extent, attendance in personal counseling might moderate the aforementioned gender differences in participants’ sensitivity to the Value barrier. It is possible that attendance in counseling accounts for a more meaningful amount of the variance in sensitivity to the Value barrier to counseling than gender. Also, consistent with the findings of Kalkbrenner et al. (in press) and Kalkbrenner and Neukrug (2018), we found psychometric support for the factorial validity of the revised version of the FSV scale. Similar to these previous investigations (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018; Kalkbrenner et al., in press), tests of internal consistency revealed strong reliability coefficients for all three FSV scales. The findings of the present investigators add to the growing body of literature on Fit, Stigma, and Value as three primary barriers to seeking counseling among a variety of populations, including human services professionals (Neukrug et al., 2017), professional counselors (Kalkbrenner et al., in press), counselor trainees (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018), and now with members of the general U.S. population.

An investigation of the path model coefficients (see Figure 1) revealed moderate to strong associations between the FSV barriers, higher compared to past investigations (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018; Kalkbrenner et al., in press). A follow-up CFA was computed to test if a single-factor model (aggregated FSV barriers into a single scale) was a better factor solution for the data. However, the follow-up CFA revealed poor model fit for the single factor solution, suggesting that Fit, Stigma, and Value comprise three separate dimensions of a related construct. The differences in the strength of association between the FSV scales in the present study and in the studies by Kalkbrenner et al. (in press) and Kalkbrenner and Neukrug (2018) might be explained by differences between the samples. These investigators validated the FSV barriers with populations of professional counselors and counseling students. It is possible that professional counselors and counseling students were better able to discriminate between different types of barriers to counseling compared to members of the general U.S. population because of the clinical nature of their training. In addition, minor discrepancies are expected in any psychometric study in which authors are attempting to confirm the dimensionality of an attitudinal measure with a new sample (Hendrick, Fischer, Tobi, & Frewer, 2013).

To summarize, the results of internal consistency reliability and CFA indicated that the Revised FSV Scale and its dimensions were estimated adequately with a stratified random sample of adults in the United States. We found close to one-third of our sample had attended counseling, 11% were in counseling at the time of data collection, and there were demographic differences in participants’ sensitivity to barriers to counseling by gender and past attendance in counseling. A number of implications for enhancing counseling practice have emerged from these findings.

Implications for Counseling Practice

With 20% of individuals in the general U.S. population living with a mental disorder, 11% in counseling, 32% having attended counseling, and others wanting counseling but wary of attending, counselors, counseling programs, and counseling organizations can all play a part in reducing the barriers that the public faces when deciding whether or not they should attend counseling. Professional counselors can become leaders in reducing barriers to attending counseling among the general U.S. population through outreach and advocacy. The implications of the following strategies for outreach and advocacy are discussed in the subsequent sub-sections: connecting prospective clients with counselors, interprofessional communication, mobile health, and reducing stigma toward seeking counseling.

Connecting Prospective Clients With Counselors

Nationally, counseling organizations can operate campaigns aimed at reducing the stigma associated with counseling and speaking to its value. The National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC) advocates for the development and implementation of grassroots community mental health approaches for supporting the accessibility of mental health services on both national and international levels (Hinkle, 2014). Like NBCC, other professional organizations (e.g., ACA and the American Mental Health Counselors Association) might include a directory of professional counselors on their website, along with their specialty areas, who work in a variety of geographic locations to help connect prospective clients with services. On a local level, it is recommended that professional counselors engage in outreach with members of their community to identify the potential unique mental health needs of people in their community and learn about potential barriers to counseling in their local area. Specifically, professional counselors can attend town board meetings and other public events to briefly introduce themselves and use their active listening skills to better understand the needs of the local community. The Revised FSV Scale is one potential tool that professional counselors might use when engaging in outreach with members of their community to gain a better understanding about local barriers to counseling.

We found that participants who had previously attended at least one session of personal counseling reported a higher perceived value of the benefits of counseling compared to those who did not attend counseling. It is possible that individuals’ attendance in counseling is related to their attributing a higher value to the anticipated benefits of counseling. Thus, we suggest community mental health counselors consider offering one free counseling session to promote prospective clients’ attendance in counseling. Just one free session might have the benefit of adding value to a client’s perceived worth of the counseling relationship and increase the likelihood of continued attendance in counseling. Offering one free session may be particularly important for men and minorities, who have traditionally attended counseling at lower rates (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Seidler et al., 2017).

Interprofessional Communication