Nov 9, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 3

Melissa J. Fickling, Matthew Graden, Jodi L. Tangen

The purpose of this phenomenological study was to explore how feminist-identified counselor educators understand and experience power in counselor education. Thirteen feminist women were interviewed. We utilized a loosely structured interview protocol to elicit participant experiences with the phenomenon of power in the context of counselor education. From these data, we identified an essential theme of analysis of power. Within this theme, we identified five categories: (a) definitions and descriptions of power, (b) higher education context and culture, (c) uses and misuses of power, (d) personal development around power, and (e) considerations of potential backlash. These categories and their subcategories are illustrated through narrative synthesis and participant quotations. Findings point to a pressing need for more rigorous self-reflection among counselor educators and counseling leadership, as well as greater accountability for using power ethically.

Keywords: counselor education, power, phenomenological, feminist, women

The American Counseling Association (ACA; 2014) defined counseling, in part, as “a professional relationship that empowers” (p. 20). Empowerment is a process that begins with awareness of power dynamics (McWhirter, 1994). Power is widely recognized in counseling’s professional standards, competencies, and best practices (ACA, 2014; Association for Counselor Education and Supervision [ACES], 2011; Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2015) as something about which counselors, supervisors, counselor educators, and researchers should be aware (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). However, little is known about how power is perceived by counselor educators who, by necessity, operate in many different professional roles with their students

(e.g., teacher, supervisor, mentor).

In public discourse, power may carry different meaning when associated with men or women. According to a Pew Research Center poll (K. Walker et al., 2018) of 4,573 Americans, people are much more likely to use the word “powerful” in a positive way to describe men (67% positive) than women (8% positive). It is possible that these associations are also present among counselors-in-training, professional counselors, and counselor educators.

Dickens and colleagues (2016) found that doctoral students in counselor education are aware of power dynamics and the role of power in their relationships with faculty. Marginalized counselor educators, too, experienced a lack of power in certain academic contexts and noted the salience of their intersecting identities as relevant to the experience of power (Thacker et al., 2021). Thus, faculty members in counselor education may have a large role to play in socializing new professional counselors in awareness of power and positive uses of power, and thus could benefit from openly exploring uses of power in their academic lives.

Feminist Theory and Power in Counseling and Counselor Education

The concept of power is explored most consistently in feminist literature (Brown, 1994; Miller, 2008). Although power is understood differently in different feminist spaces and disciplinary contexts (Lloyd, 2013), it is prominent, particularly in intersectional feminist work (Davis, 2008). In addition to examining and challenging hegemonic power structures, feminist theory also centers egalitarianism in relationships, attends to privilege and oppression along multiple axes of identity and culture, and promotes engagement in activism for social justice (Evans et al., 2005).

Most research about power in the helping professions to date has been focused on its use in clinical supervision. Green and Dekkers (2010) found discrepancies between supervisors’ and supervisees’ perceptions of power and the degree to which supervisors attend to power in supervision. Similarly, Mangione and colleagues (2011) found another discrepancy in that power was discussed by all the supervisees they interviewed, but it was mentioned by only half of the supervisors. They noted that supervisors tended to minimize the significance of power or express discomfort with the existence of power in supervision.

Whereas most researchers of power and supervision have acknowledged the supervisor’s power, Murphy and Wright (2005) found that both supervisors and supervisees have power in supervision and that when it is used appropriately and positively, power contributed to clinical growth and enhanced the supervisory relationship. Later, in an examination of self-identified feminist multicultural supervisors, Arczynski and Morrow (2017) found that anticipating and managing power was the core organizing category of their participants’ practice. All other emergent categories in their study were different strategies by which supervisors anticipated and managed power, revealing the centrality of power in feminist supervision practice. Given the utility of these findings, it seems important to extend this line of research from clinical supervision to counselor education more broadly because counselor educators can serve as models to students regarding clinical and professional behavior. Thus, understanding the nuances of power could have implications for both pedagogy and clinical practice.

Purpose of the Present Study

Given the gendered nature of perceptions of power (Rudman & Glick, 2021; K. Walker et al., 2018), and the centrality of power in feminist scholarship (Brown, 1994; Lloyd, 2013; Miller, 2008), we decided to utilize a feminist framework in the design and execution of the present study. Because power appears to be a construct that is widely acknowledged in the helping professions but rarely discussed, we hope to shed light on the meaning and experience of power for counselor educators who identify as feminist. We utilized feminist self-identification as an eligibility criterion with the intention of producing a somewhat homogenous sample of counselor educators who were likely to have thought critically about the construct of power because it figures prominently in feminist theories and models of counseling and pedagogy (Brown, 1994; Lloyd, 2013; Miller, 2008).

Method

We used a descriptive phenomenological methodology to help generate an understanding of feminist faculty members’ lived experiences of power in the context of counselor education (Moustakas, 1994; Padilla-Díaz, 2015). Phenomenological analysis examines the individual experiences of participants and derives from them, via phenomenological reduction, the most meaningful shared elements to paint a portrait of the phenomenon for a group of people (Moustakas, 1994; Starks & Trinidad, 2007). Thus, we share our findings by telling a cohesive narrative derived from the data via themes and subthemes identified by the researchers.

Sample

After receiving IRB approval, we recruited counselor educators via the CESNET listserv who were full-time faculty members (e.g., visiting, clinical, instructor, tenure-track, tenured) in a graduate-level counseling program. We asked for participants of any gender who self-reported that they integrated a feminist framework into their roles as counselor educators. Thirteen full-time counselor educators who self-identified as feminist agreed to be interviewed on the topic of power. All participants were women. Two feminist-identified men expressed initial interest in participating but did not respond to multiple requests to schedule an interview. The researchers did not systematically collect demographic data, relying instead on voluntary participant self-disclosure of relevant demographics during the interviews. All participants were tenured or tenure-track faculty members. Most were at the assistant professor rank (n = 9), a few were associate professors (n = 3), and one was a full professor who also held various administrative roles during her academic career (e.g., department chair, dean). During the interviews, several participants expressed concern over the high potential for their identification by readers due to their unique identities, locations, and experiences. Thus, participants will be described only in aggregate and only with the demographic identifiers volunteered by them during the interviews. The participants who disclosed their race all shared they were White. Nearly all participants disclosed holding at least one marginalized identity along the axes of age, disability, religion, sexual orientation, or geography.

Procedure

Once participants gave informed consent, phone interviews were scheduled. After consent to record was obtained, interviewers began the interviews, which lasted between 45–75 minutes. We utilized an unstructured interview format to avoid biasing the data collection to specific domains of counselor education while also aiming to generate the most personal and nuanced understandings of power directly from the participants’ lived experiences (Englander, 2012). As experienced interviewers, we were confident in our ability to actively and meaningfully engage in discourse with participants via the following prompt: “We are interested in understanding power in counselor education. Specifically, please speak to your personal and/or professional development regarding how you think about and use power, and how you see power being used in counselor education.” After the interviews, we all shared the task of transcribing the recordings verbatim, each transcribing several interviews. All potentially identifying information (e.g., names, institutional affiliations) was excluded from the interview transcripts.

Data Analysis

Data analysis began via horizontalization of two interview transcripts by each author (Moustakas, 1994; Starks & Trinidad, 2007). Next, we began clustering meaning units into potential categories (Moustakas, 1994). This initially revealed 21 potential categories, which we discussed in the first research team meeting. We kept research notes of our meetings, in which we summarized our ongoing data analysis processes (e.g., observations, wonderings, emerging themes). These notes helped us to revisit earlier thinking around thematic clustering and how categories interrelated. The notes did not themselves become raw data from which findings emerged. Through weekly discussions over the course of one year, the primary coders (Melissa Fickling and Matthew Graden) were able to refine the categories through dialoguing until consensus was reached, evidenced by verbal expression of mutual agreement. That is, the primary coders shared power in data analysis and sometimes tabled discussions when consensus was not reached so that each could reflect and rejoin the conversation later. As concepts were refined, early transcripts needed to be re-coded. Our attention was not on the quantification of participants or categories, but on understanding the essence of the experience of power (Englander, 2012; Moustakas, 1994). The themes and subthemes in the findings section below were a fit for all transcripts by the end of data analysis.

Researchers and Trustworthiness

Fickling and Jodi Tangen are White, cis-hetero women, and at the time of data analysis were pre-tenured counselor educators in their thirties who claimed a feminist approach in their work. Graden was a master’s student and research assistant with scholarly interests in student experiences related to gender in counseling and education. We each possess privileged and marginalized identities, which facilitate certain perspectives and blind spots when it comes to recognizing power. Thus, regular meetings before, during, and after data collection and analysis were crucial to the epoche and phenomenological reduction processes (Moustakas, 1994) in which we shared our assumptions and potential biases. Fickling and Graden met weekly throughout data collection, transcription, and analysis. After the initial research design and data collection, Tangen served primarily as auditor to the coding process by comparing raw data to emergent themes at multiple time points, reviewing the research notes written by Fickling and Graden and contributing to consensus-building dialogues when needed.

Besides remaining cognizant of the strengths and limitations of our individual positionalities with the topic and data, we shared questions and concerns with each other as they arose during data analysis. Relevant to the topic of this study, Fickling served as an administrative supervisor to Graden. This required acknowledgement of power dynamics inherent in that relationship. Graden had been a doctoral student in another discipline prior to this study and thus had firsthand context for much of what was learned about power and its presence in academia. Fickling and Graden’s relationship had not extended into the classroom or clinical supervision, providing a sort of boundary around potential complexities related to any dual relationships. To add additional trustworthiness to the findings below, we utilized thick descriptions to describe the phenomenon of interest while staying close to the data via quotations from participants. Finally, we discuss the impact and importance of the findings by highlighting implications for counselor educators.

Findings

Through the analysis process, we concluded that the essence (Moustakas, 1994)—or core theme—of the experience of power for the participants in this study is engagement in a near constant analysis of power—that of their colleagues, peers, students, as well as of their own power. Participants analyzed interactions of power within and between various contexts and roles. They shared many examples of uses of power—both observed and personally enacted—which influenced their development, as well as their teaching and supervision styles. Through the interviews, participants shared the following:

(a) definitions and descriptions of power, (b) higher education context and culture, (c) uses and misuses of power, (d) personal development around power, and (e) considerations of potential backlash. These five categories comprised the overarching theme of analysis of power and are described below with corresponding subcategories where applicable, identified in italics.

Definitions and Descriptions of Power

Participants spent much of their time defining and describing just what they meant when they discussed power. For the feminist counselor educators in this study, power is about helping. One participant, when describing power, captured this sentiment well when she said, “I think of the ability to affect change and the ability to have a meaningful impact.” Several participants shared this same idea by talking about power as the ability to have influence. Participants expressed a desire to use power to do good for others rather than to advance their personal aspirations or improve their positions. Use of power for self-promotion was referenced to a far lesser extent than using power to promote justice and equity, and any self-promotional use was generally in response to perceived personal injustice or exploitation. At times, participants described power by what it is not. One participant said, “I don’t see power as a negative. I think it can be used negatively.” Several others shared this sentiment and described power as a responsibility.

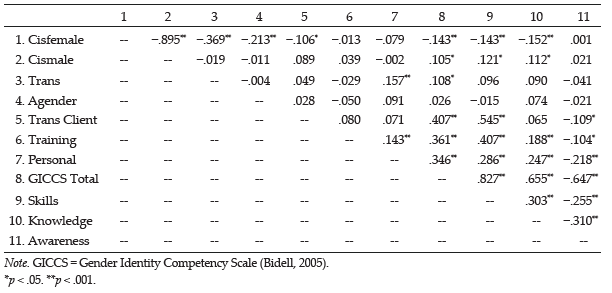

In describing power, participants identified feelings of empowerment/disempowerment (Table 1). Disempowerment was described with feeling words that captured a sense of separation and helplessness. Empowerment, on the other hand, was described as feeling energetic and connected. Not only was the language markedly different, but the shifts in vocal expression were also notable (nonverbals were not visible) when participants discussed empowerment versus disempowerment. Disempowerment sounded like defeat (e.g., breathy, monotone, low energy) whereas empowerment sounded like liveliness (e.g., resonant, full intonation, energetic).

Table 1

Empowered and Disempowered Descriptors

| Descriptors |

| Empowered |

Disempowered |

| Authentic

Free

Good

Heard

Congruent

Genuine

Selfless

Hopeful

Confident

Serene

Connected

Grounded

Energized |

Isolated

Disenfranchised

Anxious

Separated Identity

Not Accepted

Disheartened

Helpless

Small

Weak

Invisible

Wasting Energy

Tired

Powered Down |

Participants identified various types of power, including personal, positional, and institutional power. Personal power was seen as the source of the aspirational kinds of power these participants desired for themselves and others. It can exist regardless of positional or institutional power. Positional power provides the ability to influence decisions, and it is earned over time. The last type of power, institutional, is explored more through the next theme labeled higher education context and culture.

Higher Education Context and Culture

Because the focus of the study was power within counselor educators’ roles, it was impossible for participants not to discuss the context of their work environments. Thus, higher education context and culture became a salient subtheme in our findings. Higher education culture was described as “the way things are done in institutions of higher learning.” Participants referred to written/spoken and unwritten/silent rules, traditions, expectations, norms, and practices of the academic context as barriers to empowerment, though not insurmountable ones. Power was seen as intimately intertwined with difficult departmental relationships as well as the roles of rank and seniority for nearly all participants. Most also acknowledged the influence of broader sociocultural norms (i.e., local, state, national) on higher education in general, noting that institutions themselves are impacted by power dynamics.

One participant who said that untenured professors have much more power than they realize also said that “power in academia comes with rank.” This contradiction highlights the tension inherent in power, at least among those who wish to use it for the “greater good” (as stated by multiple participants) rather than for personal gain, as these participants expressed.

More than one participant described power as a form of currency in higher education. This shared experience of power as currency, either through having it or not having it, demonstrated that to gain power to do good, as described above, one must be willing or able to be seen as acceptable within the system that assigns power. Boldness was seen by participants as something that can happen once power is gained. Among non-tenured participants, this quote captures the common sentiment: “Now, once I get tenure, that can be a different conversation. I think I would feel more emboldened, more safe, if you will, to confront a colleague in that way.” The discussion of context and boldness led to the emergence of a third theme, which we titled uses and misuses of power.

Uses and Misuses of Power

Participants provided many examples of their perceptions of uses and misuses of power and linked these behaviors to their sense of ethics. Because many of the examples of uses of power were personal, unique, and potentially identifiable, participants asked that they not be shared individually in this manuscript. Ethical uses of power were described as specific ways in which participants remembered power being used for good such as intervention in unfair policies on behalf of students. Ethical uses of power shared the characteristics of being collaborative and aligned with the descriptors of “feeling empowered” (Table 1).

In contrast, misuses of power were described in terms of being unethical. These behaviors existed on a spectrum that ranged from a simple lack of awareness to a full-blown abuse of power on the most harmful end of the continuum. Lack of awareness of power, for these participants, was observed quite frequently among their counselor education colleagues and they noted that people can negatively affect others without realizing it. In some cases, they reported seeing colleagues lack cultural awareness, competence, or an awareness of privilege. Although many colleagues cognitively know about privilege and speak about it, the lack of awareness referred to here is in terms of the behavioral use of privilege to the detriment of those with less privilege. One example would be to call oneself an LGBTQ+ ally without actively demonstrating ally behavior like confronting homophobic or cis-sexist language in class. Moving along the spectrum, misuses of power were described as unfairly advantaging oneself, possibly at the expense or disadvantage of another. Misuses of power may or may not be directly or immediately harmful but still function to concentrate power rather than share it. An example shared was when faculty members insist that students behave in ways that are culturally inconsistent for that student. At the other end of the spectrum, abuses of power are those behaviors that directly cause harm. Even though abuses of power can be unintentional, participants emphasized that intentions matter less than effects. One participant described abuses of power she had observed as “people using power to make others feel small.” For example, a professor or instructor minimizing students’ knowledge or experiences serves to silence students and leads to a decreased likelihood the student shares, causing classmates to lose out on that connection and knowledge.

One participant shared a culture of ongoing misuses of power by a colleague: “And then they’re [students] all coming to me crying, you know, surreptitiously coming to me in my office, like, ‘Can I talk to you?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah, shut the door. What’d he do now?’ I’m happy to be a safe person for them, it’s an honor, but this is ridiculous.” The irony of feeling powerless to stop another’s misuses of power was not lost on the participants. One participant expressed that she wished to see more colleagues ask questions about their use of power:

We have to ask the question, “What is the impact? What is happening, what are the patterns?” We have to ask questions about access and participation and equity. . . .

And from my perspective, we have to assume that things are jacked up because we know that any system is a microcosm of the outer world, and the outer world is jacked up. So, we have to ask these questions and understand if there’s an adverse impact. And a lot of time there is on marginalized or minoritized populations. So, what are we going to do about it? It’s all well and good to see it, but what are we doing about it, you know? . . . How are you using your power for good?

Personal Development Around Power

Participants reflected deeply on their own development of their thinking about and use of power. All participants spoke early in the interviews about their training as counselors and counselor educators. Their early training was often where they first fully realized their feminist orientation and recognized a need for greater feminist multicultural dialogue and action in counseling. Participants were all cognizant of their inherent personal power but still not immune to real and perceived attempts to limit their expression of it. In general, participants felt that over time they became more able and willing to use their power in ethical ways. One participant shared the following about her change in understanding power over time:

I’ve never really been a power-focused person, and so I just don’t know that I saw it around me much before that. Which now I realize is a total construct of my privilege—that I’ve never had to see it. Then I started realizing that “Oh, there’s power all around me.” And people obsessed with power all around me. And then once I saw it, I kind of couldn’t un-see it. I think for a long time I went through a process of disillusionment, and I think I still lapse back into that sometimes where I’ll realize like, a lot of the people in positions of power around me are power-hungry or power-obsessed, and they’re using power in all the wrong ways. And maybe they don’t even have an awareness of it. You know, I don’t think everybody who’s obsessed with power knows that about themselves. It almost seems like a compulsion more than anything. And I think that’s super dangerous.

Nearly all participants reflected on their experiences of powerlessness as students and how they now attempt to empower students as a result of their experiences. Working to build a sense of safety in the classroom was a major behavior that they endorsed, often because of their own feelings of a lack of safety in learning contexts at both master’s and doctoral levels. Vulnerability and risk-taking on the part of the counselor educator were seen as evidence that efforts to create safety in the classroom were successful. Speaking about this, one participant said:

I think it’s actually very unethical and irresponsible as a counselor educator to throw students in a situation where you expect them to take all these risks and not have worked to create community and environments that are conducive to that.

Participant feelings toward power varied considerably. One said, “I think overall I feel fairly powerful. But I don’t want a lot of power. I don’t like it.” One participant shared, “I am not shy, I am not afraid to speak and so sometimes maybe I do take up too much space, and there are probably times for whatever reason I don’t take up as much space as I should,” showing both humility and a comfort with her own power. These quotes show the care with which the participants came to think about their own power as they gained it through education, position, and rank. No participants claimed to feel total ease in their relationship with their own power, though most acknowledged that with time, they had become more comfortable with acknowledging and using their power when necessary.

One participant said of her ideal expression of power: “Part of feeling powerful is being able to do what I do reasonably well, not perfect, just reasonably well. But also helping to foster the empowerment of other people is just excellent. That’s where it’s at.” This developmental place with her own power aligns with the aspirational definitions and descriptions of power shared above.

Along with their personal development around power, participants shared how their awareness of privileged and marginalized statuses raised their understanding of power. Gender and age were cited by nearly all participants as being relevant to their personal experiences with power. Namely, participants identified the intersection of their gender and young age as being used as grounds for having their contributions or critiques dismissed by their male colleagues. Older age seemed to afford some participants the confidence and power needed to speak up. One participant said:

We are talking about a profession that is three-quarters women, and we are not socialized to grab power, to take power. And so, I think all of that sometimes is something we need to be mindful of and kind of keep stretching ourselves to address.

Yet when younger participants recalled finding the courage to address power imbalances with their colleagues, the outcome was almost always denial and continued disempowerment. To this point, one participant asked, “How do we get power to matter to people who are already in the positions where they hold power and aren’t interested in doing any self-examination or critical thinking about the subject?”

Finally, power was described as permeating every part of being an educator. To practice her use of power responsibly, one participant said, “I mean every decision I make has to, at some point, consider what my power is with them [the students].” Related to the educator role, in general, participants shared their personal development with gatekeeping, such as:

I think one of the areas that I often feel in my power is around gatekeeping. And I think that is also an area where power can be grossly abused. But I think it’s just such an important part of what we do. And I think one of the ways that I feel in my power around gatekeeping is because it’s something I don’t do alone. I make a point to consult a lot because I don’t want to misuse power, and I think gatekeeping—and, really, like any use of power I think—is stronger when it’s done with others.

Again, this quote reflects the definition of power that emerged in this study as ideally being “done with others.” Gatekeeping is where participants seemed to be most aware of power and to initially have had the most anxiety around power, but also the area in which they held the most conviction about the intentional use of power. The potential cost of not responsibly using their power in gatekeeping was to future clients, so participants pushed through their discomfort to ensure competent and ethical client care. However, in many cases, participants had to seriously weigh the pros and cons of asserting their personal or positional power, as described in the next and final category.

Considerations of Potential Backlash

Participants shared about the energy they spent in weighing the potential backlash to their expressions of power, or their calling out of unethical uses of power. Anticipated backlash often resulted in participants not doing or saying something for fear of “making waves” or being labeled a “troublemaker.” Participants described feeling a need to balance confrontations of perceived misuses of power with their desire not to be seen as combative. Those participants who felt most comfortable confronting problematic behaviors cited an open and respectful workplace and self-efficacy in their ability to influence change effectively. For those who did not describe their workplaces as safe and respectful, fear was a common emotion cited when considering whether to take action to challenge a student or colleague. Many described a lack of support from colleagues when they did speak up. Some described support behind the scenes but an unwillingness of peers to be more vocal and public in their opposition to a perceived wrong. Of this, one participant said, “And so getting those voices . . . to the table seems like an uphill battle. I feel like I’m stuck in middle management, in a way.”

Discussion

For the participants in this study, analysis of power is a process of productive tension and fluidity. Participants acknowledged that power exists and a power differential in student–teacher and supervisee–supervisor relationships will almost certainly always be present. Power seemed to be described as an organizing principle in nearly all contexts—professionally, institutionally, departmentally, in the classroom, in supervision, and in personal relationships. Participants found power to be ever present but rarely named (Miller, 2008). Engaging with these data from these participants, it seems that noticing and naming power and its effects is key to facilitating personal and professional development in ways that are truly grounded in equity, multiculturalism, and social justice. Participants affirmed what is stated in guiding frameworks of counseling (ACA, 2014) and counselor education (ACES, 2011; CACREP, 2015) and went beyond a surface acknowledgement of power to a deeper and ongoing process of analysis, like Bernard and Goodyear’s (2014) treatment of power in the supervisory context.

Contemplating, reflecting on, and working with power are worthwhile efforts according to the participants in this study, which is supported by scholarly literature on the topic (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). Participants’ personal and professional growth seemed to be catalyzed by their awareness of gender and power dynamics. Participants expressed a desire for a greater recognition of the role of power and the ways in which it is distributed in our professional contexts. For example, although mentioned by only two participants, dissatisfaction in professional associations—national, regional, and state—was shared. Specifically, there was a desire to see counselor educators with positional power make deliberate and visible efforts to bring greater diversity into professional-level decisions and discussions in permanent, rather than tokenizing, ways.

The ongoing process of self-analysis that counselors and educators purport to practice seemed not to be enough to ensure that faculty will not misuse power. Though gender and age were highly salient aspects of perceptions of power for these women, neither were clear predictors of their colleagues’ ethical or unethical use of power. Women and/or self-identified feminist counselor educators can and do use power in problematic ways at times. In fact, most participants expressed disappointment in women colleagues and leaders who were unwilling to question power or critically examine their role in status quo power relations. This is consistent with research that indicates that as individual power and status are gained, awareness of power can diminish (Keltner, 2016).

These feminist counselor educators described feelings of empowerment as those that enhance connection and collaboration rather than positionality. In fact, participants’ reports of frustration with some uses of power seemed to be linked to people in leadership positions engaging in power-over moves (Miller, 2008). Participants reported spending a significant amount of energy in deciding whether and when to challenge perceived misuses of power. Confronting leaders seemed to be the riskiest possibility, but confronting peers was also a challenge for many participants. The acknowledgement of context emerged in these data, including a recognition that power works within and between multiple socioecological levels (e.g., microsystems, mesosystems, macrosystems; Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The culture of academia and higher education also contributed to unique considerations of power in the present study, which aligns with the findings of Thacker and colleagues (2021), who noted counselor educator experiences of entrenched power norms are resistant to change.

Contextualizing these findings in current literature is difficult given the lack of work on this topic in counselor education. However, our themes are similar to those found in the supervision literature (Arczynski & Morrow, 2017; Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). The participants in our study were acutely aware of power in their relationships; however, they appeared to feel it even more when in a power-down position. This finding is similar to research in the supervision context in which supervisees felt as though power was not being addressed by their supervisors (Green & Dekkers, 2010). Further, just as the supervisors researched in Mangione et al.’s (2011) study attended to power analysis, our participants strived to examine their power with students. The distinction between positive and negative uses of power was consistent with Murphy and Wright (2005). Participants conceptualized power on a continuum, attended to the power inherent in gatekeeping decisions, managed the tension between collaboration and direction, engaged in reflection around use and misuse of power, and sought transparency in discussions around power. More than anything, though, our participants seemed to continually wrestle with the inherent complexity of power, similarly to what Arczynski and Morrow (2017) found, and how to address, manage, and work with it in a respectful, ethical manner. As opposed to these studies, though, our research addresses a gap between the profession’s acknowledgement of power as a phenomenon and actual lived experiences of power by counselor educators who claim a feminist lens in their work.

Implications

The implications of our findings are relevant across multiple roles (e.g., faculty, administration, supervision) and levels (e.g., institution, department, program) in counselor education. Power analysis at each level and each role in which counselor educators find themselves could help to uncover issues of power and its uses, both ethical and problematic. The considerable effort that participants described in weighing whether to challenge perceived misuses of power indicates the level of work needed to make power something emotionally and professionally safe to address. Thus, those who find themselves in positions of power or having earned power through tenure and seniority are potentially better situated to invite discussions of power in relatively safe settings such as program meetings or in one-on-one conversations with colleagues. Further, at each hierarchical level, individuals can engage in critical self-reflection while groups can elicit external, independent feedback from people trained to observe and name unjust power structures. Counselor educators should not assume that because they identify as feminist, social justice–oriented, or egalitarian that their professional behavior is always reflective of their aspirations. It is not enough to claim an identity; one must work to let one’s actions and words demonstrate one’s commitment to inclusion through sensitivity to and awareness of power.

Additionally, we encourage counselor educators to ask for feedback from people who will challenge them because self-identification of uses or misuses of power is likely not sufficient to create systemic or even individual change. It is important to acknowledge that power is differentially assigned but can be used well in a culture of collaboration and support. Just as we ask our students to be honest and compassionately critical of their own development, as individuals and as a profession, it seems we could be doing more to foster empowerment through support, collaboration, and honest feedback.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although not all participants disclosed all their demographic identifiers, one limitation to the current study is the relative homogeneity of the sample across racial and gender lines. The predominance of White women in the present study is of concern, and there are a few possible reasons for this. One is that White women are generally overrepresented in the counseling profession. Baggerly and colleagues (2017) found that women comprised 85% of the student body in CACREP-accredited programs but only 60% of the faculty. These numbers indicate both the high representation of women seeking counseling degrees, but also the degree to which men approach, but do not reach, parity with women in holding faculty positions. Further, in Baggerly et al.’s study, about 88% of faculty members in CACREP-accredited programs were White.

Another potential reason for the apparent racial homogeneity in the present sample is that people of color may not identify with a feminist orientation because of the racist history of feminist movements and so would not have volunteered to participate. Thus, findings must be considered in this context. Future researchers should be vocally inclusive of Black feminist thought (Collins, 1990) and Womanism (A. Walker, 1983) in their research design and recruitment processes to communicate to potential participants an awareness of the intersections of race and gender. Further, future research should explicitly invite those underrepresented here—namely, women of color and men faculty members—to share their experiences with and conceptualizations of power. This will be extremely important as counselor educators work to continue to diversify the profession of counseling in ways that are affirming and supportive for all.

Another limitation is that participants may have utilized socially desirable responses when discussing power and their own behavior. Indeed, the participants identified a lack of self-awareness as common among those who misused power. At the same time, however, the participants in this study readily shared their own missteps, lending credibility to their self-assessments. Future research that asks participants to track their interactions with power in real time via journals or repeated quantitative measures could be useful in eliciting more embodied experiences of power as they arise in vivo. Likewise, students’ experiences of power in their interactions with counselor educators would be useful, particularly as they relate to teaching or gatekeeping, because some research already exists examining power in the context of clinical supervision (Arczynski & Morrow, 2017; Green & Dekkers, 2010; Mangione et al., 2011; Murphy & Wright, 2005).

We initially embarked upon this study with a simple inquiry, wondering about others’ invisible experiences around what felt like a formidable topic. More than anything, our discussions with our participants seemed to indicate a critical need for further exploration of power across hierarchical levels and institutions. We are grateful for our participants’ willingness to share their stories, and we hope that this is just the beginning of a greater dialogue.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics.

Arczynski, A. V., & Morrow, S. L. (2017). The complexities of power in feminist multicultural psychotherapy supervision. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000179

Association for Counselor Education and Supervision Taskforce on Best Practices in Clinical Supervision. (2011, April). Best practices in clinical supervision. https://acesonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ACES-Best-Practices-in-Clinical-Supervision-2011.pdf

Baggerly, J., Tan, T. X., Pichotta, D., & Warner, A. (2017). Race, ethnicity, and gender of faculty members in APA- and CACREP-accredited programs: Changes over five decades. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 45(4), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12079

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2014). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (5th ed.). Pearson.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Brown, L. S. (1994). Subversive dialogues: Theory in feminist therapy. Basic Books.

Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Davis, K. (2008). Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful. Feminist Theory, 9(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700108086364

Dickens, K. N., Ebrahim, C. H., & Herlihy, B. (2016). Counselor education doctoral students’ experiences with multiple roles and relationships. Counselor Education and Supervision, 55(4), 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12051

Englander, M. (2012). The interview: Data collection in descriptive phenomenological human scientific research. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 43(1), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916212X632943

Evans, K. M., Kincade, E. A., Marbley, A. F., & Seem, S. R. (2005). Feminism and feminist therapy: Lessons from the past and hopes for the future. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83(3), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00342.x

Green, M. S., & Dekkers, T. D. (2010). Attending to power and diversity in supervision: An exploration of supervisee learning outcomes and satisfaction with supervision. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 22(4), 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2010.528703

Keltner, D. (2016). The power paradox: How we gain and lose influence. Penguin.

Lloyd, M. (2013). Power, politics, domination, and oppression. In G. Waylen, K. Celis, J. Kantola, & S. Laurel Weldon (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of gender and politics (pp. 111–134). Oxford University Press.

Mangione, L., Mears, G., Vincent, W., & Hawes, S. (2011). The supervisory relationship when women supervise women: An exploratory study of power, reflexivity, collaboration, and authenticity. The Clinical Supervisor, 30(2), 141–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2011.604272

McWhirter, E. H. (1994). Counseling for empowerment. American Counseling Association.

Miller, J. B. (2008). Telling the truth about power. Women & Therapy, 31(2–4), 145–161.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02703140802146282

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. SAGE.

Murphy, M. J., & Wright, D. W. (2005). Supervisees’ perspectives of power use in supervision. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 31(3), 283–295.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2005.tb01569.x

Padilla-Díaz, M. (2015). Phenomenology in educational qualitative research: Philosophy as science or philosophical science? International Journal of Educational Excellence, 1(2), 101–110. https://documento.uagm.edu/cupey/ijee/ijee_padilla_diaz_1_2_101-110.pdf

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2021). The social psychology of gender: How power and intimacy shape gender relations (2nd ed.). Guilford.

Starks, H., & Trinidad, S. B. (2007). Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1372–1380.

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1049732307307031

Thacker, N. E., Barrio Minton, C. A., & Riley, K. B. (2021). Marginalized counselor educators’ experiences negotiating identity: A narrative inquiry. Counselor Education and Supervision, 60(2), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12198

Walker, A. (1983). In search of our mothers’ gardens: Womanist prose. Harcourt Brace.

Walker, K., Bialik, K., & van Kessel, P. (2018). Strong men, caring women: How Americans describe what society values (and doesn’t) in each gender. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/interactives/strong-men-caring-women

Melissa J. Fickling, PhD, ACS, BC-TMH, LCPC, is an associate professor at Northern Illinois University. Matthew Graden, MSEd, is a professional school counselor. Jodi L. Tangen is an associate professor at North Dakota State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Melissa J. Fickling, 1425 W. Lincoln Hwy, Gabel 200, DeKalb, IL 60115, mfickling@niu.edu.

Nov 9, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 3

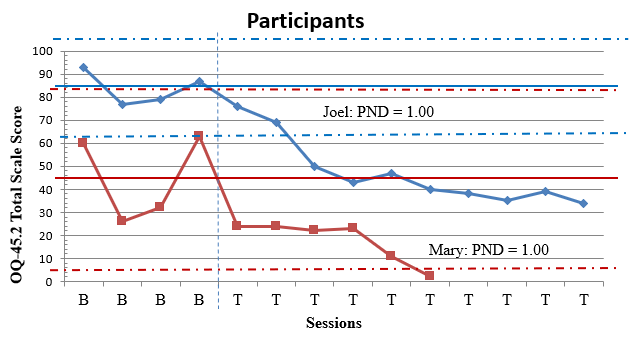

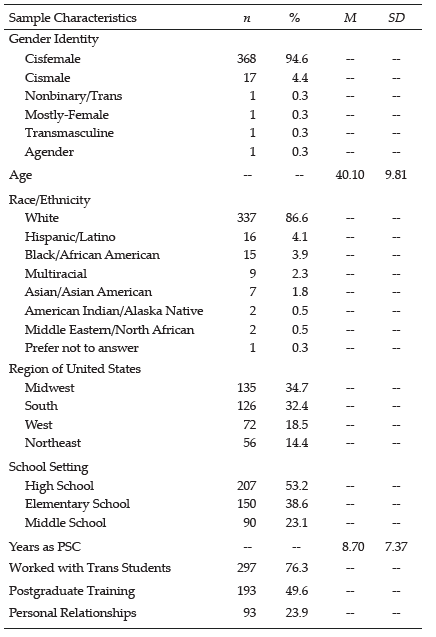

Krystle Himmelberger, James Ikonomopoulos, Javier Cavazos Vela

We implemented a single-case research design (SCRD) with a small sample (N = 2) to assess the effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) for Latine clients experiencing mental health concerns. Analysis of participants’ scores on the Dispositional Hope Scale (DHS) and Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2) using split-middle line of progress visual trend analysis, statistical process control charting, percentage of non-overlapping data points procedure, percent improvement, and Tau-U yielded treatment effects indicating that SFBT may be effective for improving hope and mental health symptoms for Latine clients. Based on these findings, we discuss implications for counselor educators, counselors-in-training, and practitioners, which include integrating SFBT principles into the counselor education curriculum, teaching counselors-in-training how to use SCRDs to evaluate counseling effectiveness, and using the DHS and OQ-45.2 to measure hope and clinical symptoms.

Keywords: solution-focused brief therapy, single-case research design, hope, counselor education, clinical symptoms

Solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) is a strength-based and evidence-based intervention that helps clients focus on personal strengths, identify exceptions to problems, and highlight small successes (Berg, 1994; Gonzalez Suitt et al., 2016; Schmit et al., 2016). Schmit et al. (2016) conducted a meta-analysis of SFBT for treating symptoms of internalizing disorders and identified that SFBT might be effective in creating short-term changes in clients’ functioning. Other researchers (e.g., Gonzalez Suitt et al., 2016; Novella et al., 2020) also found that SFBT can be helpful with clients from various cultural backgrounds and with different presenting symptoms such as anxiety. Yet, there is scant research evaluating the efficacy of SFBT on subjective well-being with Latine (a gender-neutral term that is more consistent with Spanish language and grammar than Latinx) populations. Additionally, there is not a lot of research that investigates the effectiveness of counseling practices among counselors-in-training (CITs) at community counseling clinics with culturally diverse clients. Although the costs are relatively low, the type of supervision, training, and feedback given to CITs provides community clients with the potential for effective counseling services. However, only a few researchers (e.g., Schuermann et al., 2018) have explored the efficacy of counseling services within a community counseling training clinic. Therefore, empirical research is needed regarding the efficacy of SFBT with Latine populations in a counseling training clinic at a Hispanic Serving Institution.

The Latine population is a fast-growing group in the United States and makes up approximately 19% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Despite this growth, members of this culturally diverse population continue to face individual, interpersonal, and institutional challenges (Ponciano et al., 2020; Vela, Lu, et al., 2014). Because Latine individuals experience discrimination and negative environments (Cheng & Mallinckrodt, 2015; Ponciano et al., 2020; Ramos et al., 2021), perceive lack of support from counselors and teachers in K–12 school environments (A. G. Cavazos, 2009; Vela-Gude et al., 2009), and experience microaggressions (Sanchez, 2019), they are likely to experience greater mental health challenges. Researchers have identified numerous internalizing and externalizing symptoms that represent Latine individuals’ mental health experiences, likely putting them at greater risk for mental health impairment and poor psychological functioning (Cheng et al., 2016). Researchers also detected that Latine youth had similar or higher prevalence rates of internalizing disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression) when compared with their White counterparts (Merikangas et al., 2010; Ramos et al., 2021). Given that Latine individuals might be at greater risk for psychopathology and their mental health needs are often unaddressed because they do not seek mental health services (Mendoza et al., 2015; Sáenz et al., 2013), further evaluation of the effectiveness of counseling practices for this population is necessary.

Fundamental Principles of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy

Developed from the clinical practice of Steven de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg, SFBT is a future-focused and goal-directed approach that focuses on searching for solutions and is created on the belief that clients have knowledge and resources to resolve their problems (Kim, 2008). Counselors’ therapeutic task is to help clients imagine how they would like things to be different and what it will take to facilitate small changes. Counselors take active roles by asking questions to help clients look at the situation from different perspectives and use techniques to identify where the solution occurs (de Shazer, 1991; Proudlock & Wellman, 2011).

In SFBT, counselors amplify positive constructs and solutions by using specific strategies and techniques to build on positive factors (Tambling, 2012). Common techniques include the miracle question, scaling questions, exceptions, experiments, and compliments, which are designed to help clients identify personal strengths and cultivate what works (de Shazer, 1991; Proudlock & Wellman, 2011). We agree with Vela, Lerma, et al. (2014) that counselors can use postmodern and strength-based theories (e.g., SFBT) to develop positive psychology constructs such as hope, positive emotions, and subjective well-being. SFBT might be useful to help Latine clients identify strengths, build on what works, and reconstruct a positive future outcome.

Several researchers have indicated the efficacy of SFBT for treating various issues with different populations (Bavelas et al., 2013; Kim, 2008). Schmit et al. (2016) conducted a meta-analysis with 26 studies examining the effectiveness of SFBT for treating symptoms of depression and anxiety. They found that SFBT resulted in moderately successful treatment; however, adults’ treatment effects were 5 times larger when compared to those of youth and adolescents. One possible explanation was that SFBT may require clients’ maturity to integrate and understand SFBT concepts and techniques. Researchers also concluded that the impact of SFBT may be effective in producing short-term changes that will lead to further gains in symptom relief as well as psychological functioning (Schmit et al., 2016).

Brogan et al. (2020) commented that “there are limited studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of this method with the Latine . . . population” (p. 3). However, we postulate that SFBT principles are compatible with Latine cultural and family characteristics (Lerma et al., 2015; Oliver et al., 2011). There are several reasons that make SFBT an appropriate fit for working with the Latine population. For instance, researchers suggest that understanding family dynamics or familismo when evaluating mental health and overall well-being with the Latine population is important (Ayón et al., 2010). Familismo is strong family ties to immediate and extended families in the Latine culture.

In a study investigating Latine families, Priest and Denton (2012) found that family cohesion and family discord were associated with anxiety. Calzada et al. (2013) also highlighted that although family support can positively impact mental health, family can also become a source of conflict and stress, which might result in poor mental health. By using SFBT principles, counselors can help Latine clients identify how familismo is a source of strength through sense of loyalty and cooperation among family members (Oliver et al., 2011).

Another emphasis with SFBT that aligns with the Latine culture is the focus on personal and family resiliency. Because Latine individuals must navigate individual, interpersonal, and institutional challenges (Vela et al., 2015), they have natural resilience and coping skills that align with an SFBT approach. Counselors can use exceptions, scaling questions, and compliments to help Latine individuals discover their inherent resilience and continue to persevere through personal adversity.

Constructs: Hope and Clinical Symptoms

Consistent with a dual-factor model of mental health (Suldo & Shaffer, 2008), we focused on two outcomes: hope and clinical symptoms. First, hope, which has been associated with subjective well-being among Latine populations (Vela, Lu, et al., 2014), refers to a pattern of thinking regarding goals (Snyder et al., 2002). Snyder et al. (1991) proposed Hope Theory with pathways thinking and agency thinking. Pathways thinking refers to individuals’ plans to pursue desired objectives (Feldman & Dreher, 2012), while agency thinking refers to perceptions of ability to make progress toward goals (Snyder et al., 1999). Researchers found that hope was positively related to meaning in life, grit, and subjective happiness among Latine populations (e.g., Vela, Lerma, et al., 2014; Vela et al., 2015). Other researchers (e.g., Vela, Ikonomopoulos, et al., 2016) have explored the impact of counseling interventions on hope among Latine adolescents and survivors of intimate partner violence. Given the association between hope and other positive developmental outcomes among Latine populations, examining this construct as an outcome in clinical mental health counseling services is important.

In addition to hope as an indicator of subjective well-being, we used the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2; Lambert et al., 1996) to measure clinical symptoms in the current study for several reasons, including its strong psychometric properties, its use in the counseling training clinic where this study took place, and its use in other studies that evaluate the efficacy of counseling or psychotherapy and show evidence based on relation to other variables such as depression and clinical symptoms (Ekroll & Rønnestad, 2017; Ikonomopoulos et al., 2017; Soares et al., 2018). The OQ-45.2 measures three areas that are central to individual psychological functioning: Symptom Distress, Interpersonal Relations, and Social Role Performance.

Purpose of Study and Rationale

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of SFBT for increasing hope and decreasing clinical symptoms among Latine clients. We implemented an SCRD (Lenz et al., 2012) to identify and explore changes in hope and clinical symptoms as a result of participation in SFBT. We evaluated the following research question: To what extent is SFBT effective for increasing hope and decreasing clinical symptoms among Latine clients who receive services at a community counseling clinic?

Methodology

We implemented a small-series (N = 2) AB SCRD with Latine clients admitted into treatment at an outpatient community counseling clinic to evaluate the treatment effect associated with SFBT for increasing hope and reducing clinical symptoms. The rationale for using an SCRD was to explore the impact of an intervention that might help Latine clients at a community counseling training clinic. We used criterion sampling to recruit participants who (a) sought counseling services at a community counseling clinic, (b) had internalizing symptoms related to anxiety and depression, and (c) worked with a CIT who was supervised by faculty in a clinical mental health counseling program.

Participants

Participants in this study were two adults admitted into treatment at an outpatient community counseling clinic in the Southern region of the United States. Both participants identified as Hispanic; one identified as a female and the other identified as a male. During informed consent, we explained to participants that they would be assigned pseudonyms to protect their identity. The participants consented to both treatment and inclusion in the research study.

The two participants for this study were selected to participate in this study because of their presenting internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety) and fit for SFBT principles. Because we wanted to increase hope among these Latine clients, we felt that SFBT was an appropriate approach. The fundamental principles of SFBT align with attempting to facilitate hope among clients with various symptoms because it helps clients view mental health challenges as opportunities to cultivate strengths, explore solutions, and identify new skills (Bannik, 2008; Joubert & Guse, 2021). SFBT practitioners also posit that clients can recreate their future, cultivate resilience, and construct solutions, which aligns well with tenets of the Latine culture (J. Cavazos et al., 2010). In the first session prior to treatment, both clients indicated that they believed they were in control of their future mental health and that they could construct solutions. We also informed them that SFBT focuses on future solutions as opposed to focusing on problems and the past. Because these clients indicated a willingness to explore their future through co-constructing solutions, they were a good fit for SFBT principles in counseling.

Participant 1

“Mary” was a 31-year-old Latine female with a history of receiving student mental health services at a university counseling clinic. Mary sought individual counseling services because of a recent separation with the father of her three children who was emotionally abusive. Anxiety associated with this separation was compounded by traumatic experiences from 5 years prior. Mary stated that her Latine culture generated greater symptoms of anxiety while recognizing her new role as a single mother. Mary’s therapeutic goals and focus of treatment were to reduce clinical symptoms of anxiety as well as improve self-identity and self-esteem.

Participant 2

“Joel” was a 20-year-old Latine male with a history of receiving mental health services for symptoms of depression. Joel’s therapeutic goals and focus of treatment were to reduce clinical symptoms of anxiety and associated anger as well as improve self-esteem. Joel reported being a victim of domestic violence and child abuse. Additionally, Joel expressed distress with revealing his sexual identity because of patriarchal roles in the Latine culture that may result in rejection.

Measurements

Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2)

The OQ-45.2 is a 45-item self-report outcome questionnaire (Lambert et al., 1996) for adults 18 years of age and older. Each item is associated with a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from never (1) to almost always (5). We used the total score for the OQ-45, which was calculated by summing the three subscale scores with a possible total score ranging from 0–180. Higher scores are reflective of more severe distress and impairment. Sample response items include “I feel worthless” and “I have trouble getting along with friends and close acquaintances.” This assessment was designed to include items relevant to three domains central to mental health: Symptom Distress, Interpersonal Relations, and Social Role Performance (Lambert et al., 1996).

Researchers have examined structural validity and reliability. Coco et al. (2008) used a confirmatory factor analysis to test various models of the factorial structure. They found support for the four-factor, bi-level model, which means that each survey item relates to a subscale as well as an overall maladjustment score. Amble et al. (2014) also examined psychometric properties using confirmatory factor analysis, concluding that “the total score of the OQ-45 is a reliable and valid measure for assessing therapy progress” (p. 511). Their findings are like Boswell et al.’s (2013) findings that found support for the validity of the total OQ-45 score. There is also evidence based on relation to other clinical outcomes measured by the General Severity Index from the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised, the Beck Depression Inventory, and Social Adjustment Scale (Lambert et al., 1996). Additionally, previous psychometric evaluations have revealed evidence of reliability through reliability indices such as Cronbach’s alpha (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2017; Kadera et al., 1996; Umphress et al., 1997). Internal consistency estimates through Cronbach’s alpha range from .71 to .92 (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2017; Lambert et al., 1996).

Hope

The Dispositional Hope Scale (DHS; Snyder et al., 1991) is a self-report inventory to measure participants’ attitudes toward goals and objectives. Participants responded to eight statements evaluated on an 8-point Likert scale ranging from definitely false (1) to definitely true (8). We used the total Hope score, which was obtained by summing scores for both Agency and Pathways subscales. Total scores range from 8–64, with higher scores indicating greater levels of hope. Sample response items include “I can think of many ways to get the things in life that are important to me” and “I can think of many ways to get out of a jam.”

Researchers have examined structural validity and reliability. Galiana et al. (2015) used confirmatory factor analysis to identify that a one-factor structure was the best fit. There is also evidence of validity with other theoretically relevant constructs such as meaning in life (Vela et al., 2017) as well as evidence of concurrent and discriminant validity with other measures related to self-esteem, state hope, and state positive and negative affect (Snyder et al., 1996). There is also evidence of factorial invariance (Nel & Boshoff, 2014), suggesting that factor structure is similar across gender and racial ethnic groups. Additionally, there is evidence of reliability (e.g., internal consistency) as indicated through Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .85 to .86 (Snyder et al., 2002; Vela et al., 2015).

Study Setting

During the present study, each participant was involved in individual counseling at a community counseling clinic. The facility, located in the Southern region of the United States, provides free counseling services to community members. Individual and group sessions are free and last approximately 45 to 50 minutes. The community counseling clinic offers preventive and early treatment for developmental, emotional, and interpersonal difficulties for community members. CITs at the community counseling clinic are graduate counseling students enrolled in practicum or internship.

Interventionists

Krystle Himmelberger, who was the CIT in the current study, adapted strength-based interventions designed to facilitate positive feelings by helping clients set goals, focus on the future, and find solutions rather than problems. She was a CIT in a clinical mental health counseling program. Prior to the study, she selected and designed interventions and activities according to specific guidelines from SFBT manuals and sources (Buchholz Holland, 2013; de Shazer et al., 2007; Trepper et al., 2010).

James Ikonomopoulos and Javier Cavazos Vela were faculty counseling supervisors who monitored sessions and provided weekly supervision to maintain fidelity of SFBT interventions. Bavelas et al. (2013) suggested that live supervision may provide a second set of clinical eyes to help CITs. Himmelberger received weekly supervision to ensure procedural and treatment adherence (Liu et al., 2020). Furthermore, videotaped supervision and transcriptions provided her with the ability to communicate between sessions. These measures were used to enhance treatment fidelity by focusing on quality and competency.

SFBT Principles and Intervention

Participants received six to nine sessions of individual SFBT using the description of techniques and activities in the following resources: More Than Miracles: The State of the Art of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (de Shazer et al., 2007), Solution-Focused Therapy Treatment Manual for Working With Individuals (Trepper et al., 2010), and “The Lifeline Activity With a ‘Solution-Focused Twist’” (Buchholz Holland, 2013). We used the following SFBT principles to guide the intervention: focus on specific topics, a positive and co-constructed therapeutic relationship, and questioning techniques (Trepper et al., 2010). First, Himmelberger focused on specific topics such as preferred future, strengths, confidence in finding solutions, and exceptions. She used future-specific and solution-focused language in each session to help clients focus on their preferred futures. Second, she developed a positive therapeutic relationship with clients through shared trust and co-construction of counseling experiences. She was positive and helpful, and she helped instill optimism and hope in her clients. A positive therapeutic relationship was evidenced based on her report as well as live supervision and reviews of session recordings. Finally, Himmelberger used questioning techniques that focused on clients’ strengths, exceptions, and coping skills. She used questioning techniques that helped clients focus on progress toward their preferred future and future-oriented solutions.

The techniques she used included looking for previous solutions, exceptions, the miracle question, scaling questions, compliments, future-oriented questions, and “so what is better” questions. Himmelberger used looking for previous solutions to help clients identify their previous coping strategies to cope with the problem. Based on Himmelberger’s report in supervision sessions, both clients commented that they were surprised that they had been successful in the past when the problem did not exist. She also used exceptions to help clients identify what was different when the problem did not exist. Additionally, she used present- and future-oriented questions to help clients focus on future solutions. This was an important technique as clients were not used to ignoring the problem. When clients provided updates on their progress toward their goals, Himmelberger used compliments to validate what clients were doing well. Using compliments helped cultivate a positive therapeutic relationship with these clients.

Finally, with the miracle question, she asked clients to provide details about their preferred future and what that would look like. She followed up with a question about constructing solutions regarding what work it would take to make that preferred future happen. Then in each session, she conducted progress checks toward that preferred future by asking scaling questions (On a scale from 1–10, where are you now with progress toward your preferred future?) and questions about “what is better” (What is better now when compared to last week?). She complimented clients’ progress toward that preferred future.

Procedures

We used AB SCRD to determine the effectiveness of an SFBT treatment program (Lundervold & Belwood, 2000; Sharpley, 2007) using scores on the DHS and OQ-45.2 total scale as outcome measures (Lambert et al., 1996). The two participants who were assigned to Himmelberger did not begin counseling until they consented to treatment and the research study. In other words, they did not receive counseling services prior to participation in this study. After 4 weeks of data collection, the baseline phase of data collection was completed. Participants did not receive counseling services during the baseline period.

The treatment phase began after the fourth baseline measure. At the conclusion of each individual session, participants completed the DHS and OQ-45.2. Himmelberger collected and stored the measures in each participant’s folder in a locked cabinet in the clinic. After the 12th week of data collection, the treatment phase of data collection was completed, at which point the SFBT intervention was withdrawn.

A percentage of non-overlapping data (PND) procedure was used to analyze quantitative data (Scruggs et al., 1987). A visual representation of change over time is graphically represented with a split-middle line of progress visual trend analysis showing data points from each phase (Lenz, 2015). Statistical process control charting was used to determine whether the characteristics of treatment phase data were beyond the realm of random occurrence with 99% confidence (Lenz, 2015). An interpretation of effect size was estimated using Tau-U to complement PND analysis (Lenz, 2015; Sharpley, 2007).

Data Collection and Analysis

We implemented the PND (Scruggs et al., 1987) to analyze scores on the Hope and OQ-45.2 scales across phases of treatment. The PND procedure yields a proportion of data in the treatment phase that overlaps with the most conservative data point in the baseline phase. PND calculations are expressed in a decimal format that ranges between 0 and 1, with higher scores representing greater treatment effects (Lenz, 2013).

Upon considering the percentage of data exceeding the median procedure (Ma, 2006), we selected the PND because it is considered a robust method of calculating treatment effectiveness (Lenz, 2013). This metric is conceptualized as the percentage of treatment phase data that exceeds a single noteworthy point within the baseline phase. Because we aimed for an increase in DHS scores, the highest data point in the baseline phase was used. Finally, given that we aimed for a decrease in OQ-45.2 total scale scores, the lowest data point in the baseline was used (Lenz, 2013). To calculate the PND statistic, data points in the treatment phase on the therapeutic side of the baseline are counted and then divided by the total number of points in the treatment phase (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2016).

Estimates of Effect Size and Clinical Significance

PND values are typically interpreted using the estimation of treatment effect provided by Scruggs and Mastropieri (1998) wherein values of .90 and greater are indicative of very effective treatments, those ranging from .70 to .89 represent moderate effectiveness, those between .50 to .69 are debatably effective, and scores less than .50 are regarded as not effective (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2015, 2016). Tau-U values are typically interpreted using the estimation of treatment effect provided by Vannest and Ninci (2015) wherein Tau-U magnitudes can be interpreted as small (≤ .20), moderate (.20–.60), large (.60–.80), and very large (≥ .80). These procedures were completed for each participant’s scores on the Hope and OQ-45.2 scales.

Clinical significance was determined in accordance with Lenz’s (2020a, 2020b) calculations of percent improvement (PI) values. Percent improvement values greater than 50% were interpreted as representing clinically significant improvement with large effect sizes, 25% to 49% were interpreted as slightly improved without clinical significance, and less than 25% represented no clinical significance. Lenz (2021) also recommended for researchers to provide sufficient context and visual representation when interpreting and reporting clinical significance. As one example, without context and visual representation, researchers could interpret a PI value of 49% as not having clinical significance.

Results

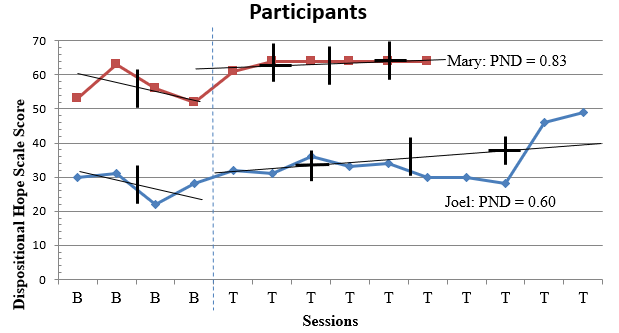

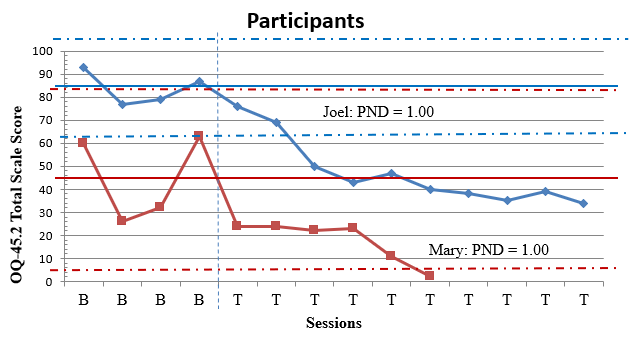

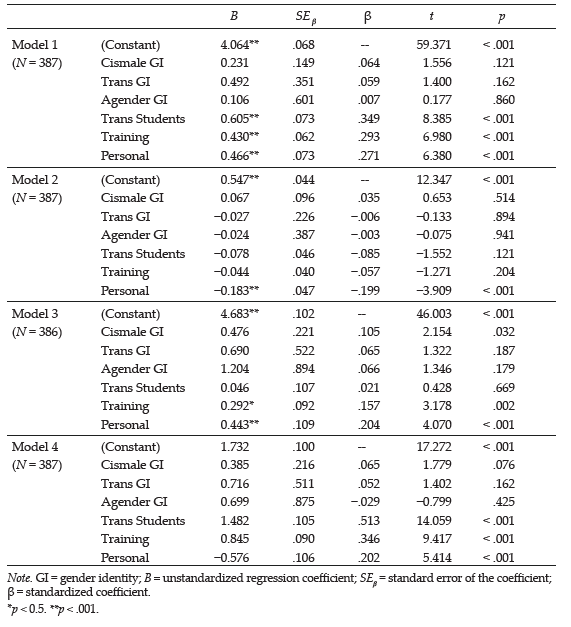

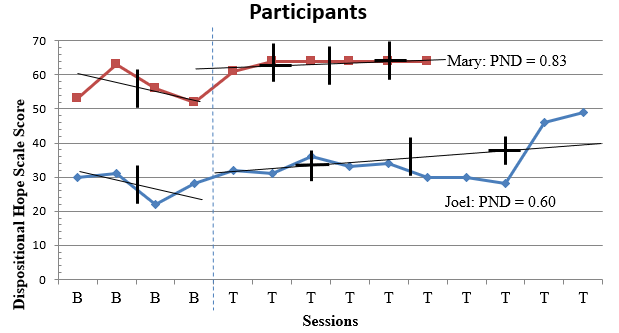

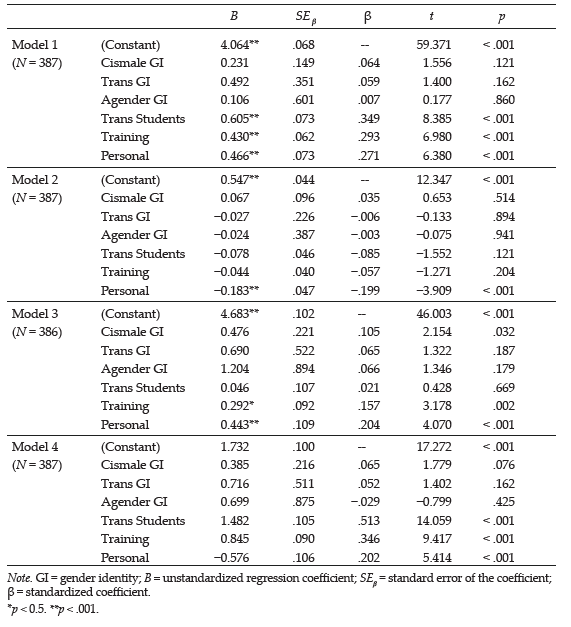

A detailed description of participants’ experiences is provided below. Figure 1 depicts estimates of treatment effect on the DHS; Figure 2 depicts estimates of treatment effect on the OQ-45.2 total scale.

Figure 1

Ratings for Hope by Participants With Split-Middle Line of Progress

Note. PND = Percentage of Non-overlapping Data.

Figure 2

Ratings for Mental Health Symptoms on OQ-45.2 by Participants with Statistical Process Control Charting

Note. PND = Percentage of Non-overlapping Data.

Participant 1

Data for Mary is represented in Figures 1 and 2 as well as Tables 1 and 2. A comparison of level of Hope across baseline (M = 56.00) and intervention phases (M = 63.50) indicated notable changes in participant scores evidenced by an increase in mean DHS scores over time. Variation between scores in baseline (SD = 3.50) and intervention (SD = 0.83) indicated differential range in scores before and after the intervention. Data in the baseline phase trended downward toward a contra-therapeutic effect over time. Dissimilarly, data in the intervention phase trended upward toward a therapeutic effect over time. Comparison of baseline level and trend data with the first three observations in the intervention phase did suggest immediacy of treatment response for the participant. Data in the intervention phase moved into the desired range of effect for scores representing Hope. Overall, visual inspection of Mary’s ratings on the DHS (see Figure 1) indicates that most of her scores in the treatment phase were higher than her scores in the baseline phase.

Mary’s ratings on the DHS illustrate that the treatment effect of SFBT was moderately effective for improving her DHS score. Evaluation of the PND statistic for the DHS score measure (0.83) indicated that five out of six scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (DHS score of 63). Mary successfully improved Hope during treatment as evidenced by improved scores on items such as “I can think of many ways to get out of a jam,” “I can think of ways to get the things in life that are important to me,” and “I meet the goals that I set for myself.” Scores above the PND line were within a 1-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. This finding is corroborated by the associated Tau-U value (τU = 0.92), which suggested a very large degree of change in which the null hypothesis about intervention efficacy for Mary could be rejected (p = .02). Also, interpretation of the clinical significance estimate of PI is that 13.39% improvement is not clinically significant (Lenz, 2020a, 2020b). See Table 1 for information regarding PND, Tau-U, and PI. Although the PI value is considered not clinically significant, it is important to contextualize this finding within visual inspection of Mary’s Hope scores in Figure 1. Because Mary had moderately high levels of Hope in the baseline phase, her room for improvement based on the ceiling effect as related to Hope was not high. In other words, in the context of Mary’s treatment and visual inspection of her scores, the SFBT intervention helped Mary move from good to better. In the context of Mary’s treatment and a visual representation of her scores on the DHS (see Figure 1), the SFBT intervention had some level of convincingness, which means that some amount of change in Hope occurred for Mary (Kendall et al., 1999; Lenz, 2021).

Table 1

Ratings for Hope by Participants

|

Age |

Ethnicity |

Gender |

Baseline Data |

Intervention Data |

PND |

τU (p) |

PI |

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

| Mary |

31 |

Latina |

Female |

56.00 |

3.50 |

63.50 |

0.83 |

83% |

0.92 (.02) |

13.39% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Joel |

20 |

Latino |

Male |

27.75 |

2.87 |

34.90 |

5.26 |

60% |

0.70 (.05) |

25.75% |

Note. PND = Percentage of Non-overlapping Data.

Table 2

Ratings for OQ-45.2 Total Scale Score by Participants

|

Age |

Ethnicity |

Gender |

Baseline Data |

Intervention Data |

PND |

τU (p) |

PI |

|

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

|

| Mary |

31 |

Latina |

Female |

45.25 |

16.25 |

17.67 |

7.44 |

100% |

−1.00 (.01) |

60.95% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Joel |

20 |

Latino |

Male |

84.00 |

6.00 |

47.10 |

10.74 |

100% |

−1.00 (.004) |

43.93% |

|

Note. PND = Percentage of Non-overlapping Data.