Apr 1, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 2

Shaywanna Harris, Christopher T. Belser, Naomi J. Wheeler, Andrea Dennison

Despite the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision ending school segregation in 1954, African American children and other children of color still experience severe and adverse challenges while receiving an education. Specifically, Black and Latino male students are at higher risk of being placed in special education classes, receiving lower grades, and being suspended or expelled from school. Although adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and the negative outcomes associated with experiencing them, are not specific to one racial or ethnic group, the impact of childhood adversity exacerbates the challenges experienced by male students of color at a biological, psychological, and sociological level. This article reviews the literature on how ACEs impact the biopsychosocial development and educational outcomes of young males of color (YMOC). A strengths-based perspective, underscoring resilience among YMOC, will be highlighted in presenting strategies to promote culturally responsive intervention with YMOC, focused professional development, and advocacy in the school counseling profession.

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences, development, school counseling, young males of color, strengths-based

Racial and ethnic disproportionality in academic success, exclusionary school discipline practices, and dropout rates contribute to the disproportionate representation of racial minority and disadvantaged youth in the prison system, also known as the school-to-prison pipeline phenomenon (Belser et al., 2016). Higher expulsion and out-of-school suspension rates occur for Black and Latino students. In addition, African American students are almost four times as likely as European American students to experience a disciplinary referral (Bottiani et al., 2017; Skiba et al., 2011). Black and Latinx men are overrepresented within the U.S. prison system, with theoretical explanations for the school-to-prison pipeline including the influence of family poverty and socioeconomic status (SES) or racial disparities in school and social policy (Scott et al., 2017). Yet, resilience among young males of color (YMOC), a term that includes those from diverse backgrounds, provides a healing counternarrative for the well-documented deficit lenses often applied to YMOC (Harper, 2015). Therefore, we propose a contextualized understanding of biopsychosocial development that accounts for the influence of early exposure to adversity, as well as sources of resilience. In so doing, we highlight implications for school counselors who work with YMOC to foster equity in opportunity, achievement, persistence, and support.

School Experiences of YMOC

School climate refers to students’ sense of belonging and experience of the academic environment. Further, school climate influences student engagement and peer relationships, as well as academic and social development (Konold et al., 2017). Aspects of school climate, such as safety and school liking, contribute to positive outcomes, including greater enrollment in higher education among Black and Latino adolescents (Garcia-Reid et al., 2005; Minor & Benner, 2017). However, Black students typically report lower levels of perceived care and equity in school than their White counterparts (Bottiani et al., 2016). Further, discrimination experiences based on race degrade perceived school climate, and as a result, students also experience lower GPAs and more absences from school (Benner & Graham, 2011). In addition to the effects on attendance and grades, perceived discrimination also negatively relates to psychological well-being and physical health (Hicken et al., 2014; Hood et al., 2017). Thus, YMOC’s differential experiences of school climate and discrimination result in social, academic, and physical correlates with lifelong consequences.

Bryant et al. (2016) identified risk and protective factors experienced by YMOC that inform their recommendations for practice and policy. Risk factors included a lack of mentors and counselors to advocate for education and employment training, disproportionate exposure to community violence, and inadequate access to health care and career opportunities. Further, racially diverse and economically disadvantaged individuals reported a higher likelihood of exposure to violence, abuse, and other forms of adversity as children (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2013). Thus, Bryant et al.’s (2016) recommendations underscored the necessity for health and education professionals to seek cultural competence and make proactive efforts to mitigate the effects of exposure to violence and trauma. School counselors play an important role in the promotion of diversity and positive school climate for all students, as well as student academic success and social/emotional development (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2019).

Academically successful students from low-income families identified the importance of school counselors’ efforts to build caring, non-judgmental relationships that emphasize student strengths, goals, and a holistic view of student success (Williams et al., 2015). Similarly, L. C. Smith et al. (2017) theorized the utility of restorative practices as a way for school counselors to build caring and connected relationships, especially for students of color facing social inequities. Yet, school counselors’ unshared expectations and unclear roles with students of color can hinder the development of a trusting relationship (Holland, 2015). Some school counselors primarily address academic and college planning, yet schools with higher percentages of students of color indicate that school counselors primarily focus on behavioral concerns. Conversely, students in those schools experience greater acceptance of efforts to address issues of diversity and equity across stakeholder groups (Dye, 2014; Nassar-McMillan et al., 2009; Shi & Goings, 2017). As states work to decrease the student-to-counselor ratio, opportunities exist for school counselors to engage in meaningful ways and advocate for their students and YMOC with a holistic view of the related strengths, needs, and contextual stressors students experience.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are events experienced early in life that initiate a lifelong trajectory associated with negative consequences for development and health. Longitudinal examination of the correlates of exposure to ACEs includes deficits in physical, mental, and emotional health; educational attainment; financial stability; and social functioning, with increased risk for justice system involvement (Copeland et al., 2018). A higher prevalence of ACEs is reported by individuals who identify as having a multiracial ethnic background (Merrick et al., 2018). Similarly, racially and economically diverse samples report more ACEs and may therefore be more susceptible to the risk for poor physical and mental health outcomes (Cronholm et al., 2015; Wheeler et al., 2018).

The original ACEs screening tool includes 10 forms of adversity that respondents may have encountered prior to age 18 (e.g., abuse, neglect, household dysfunction); however, as new knowledge has emerged about additional types of adversity also associated with poor health, such as the complex and chronic stress posed by racially hostile or unwelcoming environments, ACEs screening tool development has continued to evolve (e.g., the ACE-IQ; Cronholm et al., 2015). Additionally, the need for improved understanding of protective factors that may interact with or even counteract ACEs has been identified. For example, researchers developed measures like the Health-Resiliency-Stress Questionnaire (Wiet & Trauma-Resiliency Collaborative, 2019) and Benevolent Childhood Experiences (Narayan et al., 2018) and Positive Childhood Experiences (Bethell et al., 2019) scales to identify positive childhood experiences that may also influence health and resilience amidst adversity. Such measures include factors associated with the individual student, such as self-acceptance, as well as systemic factors, including the community (e.g., culture, community traditions, fair treatment, opportunities for fun, resources for skill development and assistance), school (e.g., caring adults, sense of belonging), peers and supportive others (e.g., role models and non-parent adults), and family (e.g., home routine, safety, family cohesion, emotional expression), all of which may contribute to risk and resilience.

It must also be noted that the interaction of risk and protective factors experienced by an individual is also an important consideration in research and practice. For example, Layne et al. (2014) proposed the Double Checks Heuristic, which involves considering protective factors, vulnerability factors, and negative outcomes when conceptualizing clients. The Double Checks Heuristic helps clinicians and researchers consider risk factors as well as strengths and protective factors to find the best ways in which to intervene and support clients (Landolt et al., 2017).

Biological Development

As is clear in the ACEs literature, childhood experiences have strong and significant relationships with biological development and physical health outcomes later in life (Copeland et al., 2018; Edwards, 2018). Specifically, childhood experiences are integral to brain development and gene expression (Anda et al., 2006). During this period, the brain is highly sensitive to the experiences a child has, adapts to these new experiences, and learns from them by adapting through growth and development. Chronic stressors, adverse experiences, and traumas disrupt equilibrium in the developing brain, especially during sensitive periods of development (Glaser, 2000). Consistent disruptions to the developing brain’s homeostasis create new, less flexible patterns of operation within the brain (Perry & Pollard, 1998).

Researchers have linked ACEs to impairment in brain development and neurological functions. Both structural and functional impairments occur in the brain as a result of traumatic experiences in childhood (Edwards, 2018). Specifically, sexual abuse, neglect, and other ACEs are believed to impede brain development because of insecure attachment and continued stress response in the body. Attachment in infants is linked to heartrate variability and the exposure to neurotransmitters like oxytocin and dopamine in the brain (Glaser, 2000). Chronic stress is also linked to the death of hippocampal cells that contribute to memory, learning, and emotion. Further, Roth et al. (2018) examined the impact of severe neglect on brain development in the amygdala—the location in the brain responsible for emotion regulation. The authors found a relationship between right hemisphere amygdala volume, anxiety, and neglect in adolescents aged 9–15. Boys who experienced severe neglect showed increased amygdala volume, which contributed to higher instances of anxiety and fear response within the brain (Roth et al., 2018).

Psychological Development

Childhood emotional and psychological development is paramount to success in children. Children who are not at economic risk and who exhibit higher levels of self-regulation are more likely to experience success in school (Denham et al., 2012). Parenting style also appears to be a major contributing factor to positive psychological development (Le et al., 2008).

Researchers have linked authoritative parenting styles to positive mental health and psychological development in children (Steinberg et al., 1989). However, much of the literature approaches parenting style from a perspective that pathologizes parenting in families of color, not considering contextual and cultural factors that impact parenting (Le et al., 2008). Specifically, parents from lower SES families may demonstrate more permissive or authoritarian parenting styles (Hoff et al., 2002). Yet, parents in low SES families in South Africa showed high knowledge of child development norms and milestones, which is linked to more confidence in parenting and to successful outcomes in children (Bornstein & Putnick, 2007; September et al., 2016). Therefore, researchers must consider contextual and cultural factors when examining YMOC’s psychological development.

Mental health outcomes for individuals with higher numbers of ACEs include greater instances of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Exposure to ACEs increases the odds of experiencing depressive symptoms by approximately three times (Von Cheong et al., 2017). Moreover, children who have experienced exposure to violence, poor parental mental/behavioral health, or racial/ethnic discrimination are at increased risk of depression and anxiety (Zare et al., 2018). Specifically, YMOC disproportionately experience community violence, which increases the likelihood of also experiencing depressive symptoms (Graham et al., 2017). Moreover, African American men have substantially reported PTSD symptoms, including hyperawareness, irritability, and avoidance, at an alarming rate (91%; Bowleg et al., 2014).

Social Development

As psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD, is prevalent among YMOC who have experienced adversity, ACEs lead to differences in social development as well. Social development is highly dependent upon attachment to caregivers (Gross et al., 2017). That is, children who experience secure attachment with caregivers are more likely to exhibit prosocial behaviors. As children who experience neglect are more likely to have disorganized attachment styles, children with more ACEs may be less likely to fully develop prosocial and executive functioning skills (Matte-Gagné et al., 2018).

Relatedly, childhood adversity is correlated with lower levels of relationship support and higher levels of relationship strain in adulthood. This association was particularly pronounced among Black men, who reported the strongest influence of childhood adversity as a contributor to increased relationship strain and decreased relationship support over time (Umberson et al., 2016). Further, ACEs that include family violence contribute to higher risk of dating aggression and intimate partner violence in future relationships (Laporte et al., 2011; Whitfield et al., 2003).

Educational Outcomes

YMOC are at higher risk for the negative outcomes associated with ACEs at a biological, psychological, and social level. The impact of adverse experiences in YMOC specifically affects their abilities to engage in school. ACEs have been shown to adversely impact school success, learning and behavior, school engagement, and cognitive performance (Denham et al., 2012). Specifically, children who experience three or more ACEs have been shown to have adversely impacted language, literacy, and math skills, as well as increased attention problems (Jimenez et al., 2016).

YMOC are also disproportionately represented in the population of students being referred for out-of-school suspension or expulsion because of behavioral problems (Anyon et al., 2018). In a sample of predominantly ethnic minority children, children who experienced more ACEs were at higher risk of exhibiting behavioral problems (Burke et al., 2011). Moreover, children of color may experience behavioral problems that are exacerbated by peer rejection (Dodge et al., 2003). Education-specific outcomes of ACEs include academic, social, and emotional factors—direct areas of importance for school counselors. Thus, educational outcomes may play an important role in supporting success among YMOC.

Implications for School Counselors

School counselors are uniquely positioned to address this issue specifically because they work at the intersection of mental health and education. That is, school counselors are trained to provide preventive and responsive services in formats ranging from individual interventions to whole-school programming, making them well suited to address the issues of YMOC in various capacities (ASCA, 2019). The following sections highlight interventions and strategies that school counselors can utilize to both directly and indirectly help YMOC and increase equity. Whereas the literature review was structured to highlight prior research on biological, psychological, and social development and educational outcomes separately, these areas are inextricably linked. As such, the following sections will additionally highlight strategies and opportunities that school counselors can embrace and the biopsychosocial and educational implications of each area.

Fostering Nurturing Environments

Fostering nurturing environments can hold promise for the biopsychosocial development of all students, with particular benefits to YMOC. Graham et al. (2017) reviewed literature on existing initiatives and programs and recommended trauma-informed school practices, school-based clubs and sports teams, and mentoring programs involving adult men of color as strategies that schools can utilize to promote connectedness and positive experiences in schools. Additionally, Graham et al. noted the importance of linking students to out-of-school sports, community activities, and mentoring programs, which could be a great opportunity for school counselors to bridge gaps between school activities and community programming, thus improving social and psychological development. Importantly, Shi and Goings (2017) found that African American students from low socioeconomic backgrounds were more likely to talk to their school counselor about personal problems if they felt a stronger sense of belonging within the school. Similarly, Carney et al. (2017) demonstrated that increased levels of school connectedness elevated the impact that improving social skills could have on relieving students’ emotional concerns. These studies suggest that school counselors should ensure that school counseling programming includes efforts targeted at YMOC, with the goals of interrupting or mediating the potential biopsychosocial effects of exposure to adversity and trauma, increasing help-seeking behaviors, and increasing social support networks.

Williams et al. (2015) interviewed a sample of academically successful low-income students, who reported that school counselors can foster resilience through tapping into students’ aspirational and social capital. The students further noted that school counselors can make an impact by showing they care and by challenging their personal biases about marginalized students. In schools dealing with the effects of gentrification, Bell and Van Velsor (2017) encouraged school counselors to engage the school community in conversations and interventions geared toward bridging the gaps between cultural groups. Similarly, Pica-Smith and Poynton (2014) suggested that school counselors can be instrumental in promoting interethnic friendships in students as a strategy to combat prejudice and racism.

Culturally Relevant Assessment and Screening

Because of the complex nature of issues that can stem from exposure to trauma and adversity, school counselors should also use related screenings and assessments with caution and intention. Eklund and Rossen (2016) provided guidance for schools that wish to screen for trauma, noting specifically that schools should only proceed with trauma screening when they are adequately prepared to address the student concerns revealed in the data. They further posited that screening students with trauma exposure can further stigmatize these students and can, in some cases, re-traumatize the students (Eklund & Rossen, 2016). Moreover, Anda et al. (2020), some of the original ACEs researchers, caution practitioners from misapplication of global ACEs research for individual screening and decision-making for services or intervention. One person’s experience with ACEs may differ from another’s, even if they have the same score on an ACEs assessment. Therefore, the unique experience of ACEs, resilience, and the context of the individual are important considerations. ACEs may not always equate to trauma for the individual. Accordingly, rather than using the ACEs questionnaire to determine the presence and magnitude of students’ exposure to specific adversities, schools may be better off screening for specific psychosocial stress and trauma concerns, such as internalizing and/or externalizing behaviors, the presence of specific trauma symptoms, and help-seeking or coping behaviors. Schools that are equipped with school nurses or additional medical professionals may be better equipped to factor in more biological and medical screenings to provide a more holistic screening and intervention process. Whether using a simple or complex approach, school counselors are in a position to take a leadership role in these efforts, drawing from their training with developing a multi-tiered system of supports, utilizing data, and universal screening.

Reinbergs and Fefer (2018) discussed the importance of universal screening in recognizing trauma in schools, but they did not include specific implications related to students of color. Because universal screening relies more on objective measures rather than observation alone, it may reduce the influence of bias and oversight when assessing students of color (Belser et al., 2016). Another key consideration when developing a universal screening plan is to try to involve information provided by students, which can help ensure that their voices are heard and catch students who would otherwise have fallen through the cracks if teachers were unaware of circumstances happening in the students’ homes and communities (Eklund & Rossen, 2016). For YMOC whose voices are often marginalized or minimized, this step can be important in gaining buy-in and increasing their sense of belonging (Ngo et al., 2008). When selecting a screening tool, school counselors and school leaders must ensure that the tool has been adequately researched with minority populations and in varied settings (i.e., urban, suburban, and rural). Eklund et al. (2018) conducted a systematic review of screening measures focused on trauma in children and adolescents, as well as implications for their use in schools. Proper screening for traumatic experiences, as well as support systems and sources of strength, is a valuable step in the process of developing interventions.

Interventions for School Counselors

Neuroscience and psychology research has linked chronic stress, often associated with trauma exposure and a higher number of ACEs, to negative impacts on self-regulation and emotional coping responses (Denham et al., 2012; Roth et al., 2018). Existing literature suggests programming that promotes adaptive coping and self-expression may show promise for YMOC, although many existing interventions have not been adequately researched with this population (Graham et al., 2017). The Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools program, a systematic approach involving students, teachers, and parents, was developed to help with a variety of types of trauma and has shown efficacy with African American students and other students of color (Jaycox et al., 2010; Ngo et al., 2008). Play therapy may provide a solution for younger students, as individual and group child-centered play therapy interventions yielded decreases in worrying, reductions in intrusive negative thoughts, and decreases in problematic behaviors that had been leading to classroom exclusion (Patterson et al., 2018).

Interventions that focus on fostering new and safe interethnic social bonds and repairing fractured bonds can promote interpersonal and intrapersonal growth, perspective taking, and self-concept (Baskin et al., 2015; Pica-Smith & Poynton, 2014). School counselors can model for students how to openly discuss issues of race, which can lead to greater bidirectional understanding of issues faced by students of color. Open, healthy communication about issues involving race/ethnicity can decrease the potential for students of color to suffer from perceived racism or discrimination in school; this can lead to fewer school absences, improved GPA, and improved psychological and physical well-being (Hicken et al., 2014; Hood et al., 2017). Pica-Smith and Poynton (2014) argued that modeling such conversations, as well as providing opportunities for intergroup dialogue in formal and informal school counseling interventions, can lead to increased personal and other-focused awareness, knowledge of privilege and racism, and empathy and perspective taking. Forgiveness interventions may have promise for African American students who have experienced emotional injury (Baskin et al., 2015). The model described by Baskin et al. (2015) involves getting in touch with feelings of anger and resentment, exploring how holding on to these feelings has been working in the past, examining how role models and others in the student’s life have navigated victimization, and finally “discovering the freedom of forgiveness” (p. 9). The focus of this intervention on reducing internal and external manifestations of anger has implications for benefitting students’ physical, emotional, and social health.

Interventions that focus on self-expression and storytelling provide YMOC with opportunities to verbalize thoughts, feelings, and experiences, as well as learn from the stories of others. Students of color can find socially relevant and empowering messages in hip-hop lyrics, and school counselors can utilize hip-hop and spoken-word interventions to promote positive outcomes for students of color (Levy et al., 2018; Washington, 2018). Integrating hip-hop and spoken-word interventions into counseling has the potential to bolster the counselor–client relationship (Elligan, 2004; Kobin & Tyson, 2006; Levy & Adjapong, 2020), reveal students’ existing coping and defense mechanisms (Levy, 2012), and identify ways to verbalize emotions that are socially and culturally relevant to students of color (Levy & Keum, 2014). Culturally affirming bibliotherapy is another trauma-related intervention that has shown efficacy with elementary-aged African American students (Stewart & Ames, 2014). Organizations like We Need Diverse Books have helped promote books written for children and teens that highlight the experiences, stressors, and traumas of YMOC. Incorporating these books into counseling interventions can provide a conduit for social and vicarious learning and developing a feeling of universality with characters who have experienced similar traumatic experiences, thereby opening doors for emotional release and expression, identifying adaptive and maladaptive coping mechanisms, and learning from the growth of others.

Building Knowledge of Unique Stressors and Traumas

School counselors should also expand their knowledge of unique stressors and traumas facing YMOC and the potential associated outcomes. Henfield (2011) found that Black male middle school students felt that their primarily White environments stereotyped them, exposed them to microaggressions, and viewed them with an “assumption of deviance” (p. 147). Jernigan and Daniel (2011) noted that schools operate as microcosms of the larger society, implying that this setting may be a key place to help young Black males develop a positive racial/ethnic identity and agency to recognize and navigate discriminatory experiences. This same research should serve as an impetus for school leaders, especially counselors, to recognize and intervene in cases of microaggressions, microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations, which can lead to a harmful school climate for people of color (Sue et al., 2019).

J. R. Smith and Patton (2016) interviewed young Black males who had been exposed to community violence and found that diagnostic criteria for PTSD emerged from their narratives. Such findings provide context on the magnitude of the impact that exposure to community traumas can have on YMOC. Diagnosis and treatment of PTSD would be outside the ethical scope of practice for school counselors, which increases the necessity for school counselors to aid students and families in accessing mental and behavioral health services, as well as other community resources, outside of the school. Whereas therapeutic treatment of trauma symptoms and PTSD may go beyond the role of school counselors, school counseling programs should include efforts to bolster nurturing school environments that augment students’ adaptive coping skills.

Changing Demographics in the School Counseling Profession

Whereas the ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors (2016a) do not specifically address ACEs or trauma-informed care as an ethical imperative, several standards do apply for school counselors working with male students of color who have experienced childhood adversity or trauma. The code’s Preamble notes that school counselors are called to support the optimal development of underserved groups and provide equitable service delivery, a charge that is bolstered by ASCA’s position statements on cultural diversity (ASCA, 2015). Other ethical standards highlight the need for school counselors to stay abreast of best practices and research in providing services and programming for students. In 2016, ASCA adopted a position statement on trauma-informed practice delineating the roles of school counselors in providing trauma-sensitive initiatives and services in schools; these roles include delivering direct student services, ensuring that teachers and staff are trained and aware, and building relationships with community partners who can also help serve students who have experienced trauma and adversity (ASCA, 2016b).

Despite these calls for school counselors to provide equitable and culturally responsive interventions for students coping with traumatic experiences, the school counseling literature has not adequately addressed school counselors’ roles in working with the unique stressors and experiences faced by YMOC. Moreover, ASCA most recently reported their membership as being 85% female and 76% White (ASCA, 2021). With these demographic statistics in mind, it is vitally important for practicing school counselors to critically examine knowledge gaps and blind spots with regard to providing adequate services for male students of color. School counselors must maintain an up-to-date working knowledge of the impacts of chronic stress and trauma on the developing brain in order to advocate for students. Additionally, school counselors must incorporate trauma-sensitive interventions in their work with male students of color. The section that follows, as well as the Appendix, provides an overview of professional development, intervention, and assessment strategies for school counselors.

Developing Multicultural Competence in School Counselors

School counselors have an ethical imperative to examine their own multicultural competence and practice if they are to adequately conceptualize and meet the needs of YMOC. This process is critical and must be approached from multiple avenues of activity as outlined in the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (Ratts et al., 2016), including counselor self-awareness; understanding for the client’s worldview; approaches utilized to form counseling relationships; and more broadly, the delivery of counseling and advocacy interventions.To begin, counselor self-awareness may be developed informally through reading, self-reflection, or journaling for racial understanding and healing and can be part of supervision or consultation practices (Singh, 2019). School counselors can also use more formalized instruments to assess their multicultural competence and practice. Such instruments include the School Counseling Multicultural Self-Efficacy Scale (SCMES; Holcomb-McCoy et al., 2008), the Multicultural School Counseling Behavior Scale (MSCBS; Greene, 2018), and the Multicultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills Survey-Counselor Edition (MAKSS-CE; Kim et al., 2003). By tying self-evaluative practices to one’s own multicultural professional development, school counselors can evaluate and reevaluate their growth. Such practices can be helpful as school counselors adopt new techniques or participate in structured training experiences.

Ratts and Greenleaf (2017) developed the Multicultural and Social Justice Leadership Form (MSJLF) as a tool to help school counselors evaluate specific issues that arise in a school, examine counselor- and client-level information pertaining to the issue, and develop both counseling and advocacy interventions. This model can serve as a way for school counselors to better understand and act on issues pertaining to YMOC in their schools. Moreover, the MSJLF may be particularly helpful in recognizing biases and blind spots in light of the demographic makeup of the school counseling profession discussed above.

Swan et al. (2015) evaluated outcomes of a multicultural skills–based curriculum for counselors working with children and adolescents. The participants saw increases in their ability to empathize, demonstrate genuineness, and impart unconditional positive regard to their young clients. Moreover, the clients’ perceptions of the counselors’ cultural competence increased. This study supports the need for school counselors, particularly White school counselors working with marginalized and minoritized populations, to participate in professional development opportunities centered on fostering multicultural competence.

Conclusion

ACEs and trauma are undeniably taking a toll on children and adolescents in the United States, and YMOC are particularly at risk. The negative impacts can be seen in academic, social, biological, and psychological development. School counselors are uniquely positioned in educational environments to recognize and intervene with trauma-related issues through assessment of both risk and resiliency, direct programming, mental health referrals, community engagement, and school culture building. As such, it is imperative for school counselors to advocate for adequate training for themselves and school staff in the areas of cultural competence and trauma-informed practices, as well as advocate for best practices in directly treating the impacts of trauma, including that caused by structural and systematic racism. Additionally, as a profession that is primarily White and female, school counselors and school counselor educators must take steps to diversify the profession in ways that match the demographics of students and society and must continue to explore the efficacy of culturally informed trauma interventions in schools.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Accomazzo, S., Israel, N., & Romney, S. (2015). Resources, exposure to trauma, and the behavioral health of youth receiving public system services. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(11), 3180–3191. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10826-015-0121-y

American School Counselor Association. (2015). The school counselor and cultural diversity. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-Cultural-Diversity

American School Counselor Association. (2016a). Ethical standards for school counselors. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/f041cbd0-7004-47a5-ba01-3a5d657c6743/Ethical-Standards.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2016b). The school counselor and trauma-informed practice. https://schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-Trauma-Informed-Practice

American School Counselor Association. (2019). ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (4th ed.).

American School Counselor Association. (2021). ASCA research report: State of the profession 2020. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/bb23299b678d-4bce-8863-cfcb55f7df87/2020-State-of-theProfession.pdf

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C. H., Perry, B. D., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology to epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

Anda, R. F., Porter, L. E., & Brown, D. W. (2020). Inside the adverse childhood experience score: Strengths, limitations, and misapplications. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(2), 293–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.01.009

Anyon, Y., Lechuga, C., Ortega, D., Downing, B., Greer, E., & Simmons, J. (2018). An exploration of the relationships between student racial background and the school sub-contexts of office discipline referrals: A critical race theory analysis. Race, Ethnicity, and Education, 21(3), 390–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2017.1328594

Baskin, T. W., Russell, J. L., Sorenson, C. L., & Ward, E. C. (2015). A model for school counselors supporting African American youth with forgiveness. Journal of School Counseling, 13(7). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1062931

Bell, L. E., & Van Velsor, P. (2017). Counseling in the gentrified neighborhood: What school counselors should know. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-21.1.161

Belser, C. T., Shillingford, M. A., & Joe, J. R. (2016). The ASCA model and a multi-tiered system of supports: A framework to support students of color with problem behavior. The Professional Counselor, 6(3), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.15241/cb.6.3.251

Benner, A. D., & Graham, S. (2011). Latino adolescents’ experiences of discrimination across the first 2 years of high school: Correlates and influences on educational outcomes. Child Development, 82(2), 508–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01524.x

Bethell, C., Jones, J., Gombojav, N., Linkenbach, J., & Sege, R. (2019). Positive childhood experiences and adult mental and relational health in a statewide sample: Associations across adverse childhood experiences levels. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(11). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3007

Bornstein, M. H., & Putnick, D. L. (2007). Chronological age, cognitions, and practices in European American mothers: A multivariate study of parenting. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 850–864. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.850

Bottiani, J. H., Bradshaw, C. P., & Mendelson, T. (2016). Inequality in Black and White high school students’ perceptions of school support: An examination of race in context. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(6), 1176–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0411-0

Bottiani, J. H., Bradshaw, C. P., & Mendelson, T. (2017). A multilevel examination of racial disparities in high school discipline: Black and White adolescents’ perceived equity, school belonging, and adjustment problems. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(4), 532–545. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000155

Bowleg, L., Fitz, C. C., Burkholder, G. J., Massie, J. S., Wahome, R., Teti, M., Malebranche, D. J., & Tschann, J. M. (2014). Racial discrimination and posttraumatic stress symptoms as pathways to sexual HIV risk behaviors among urban Black heterosexual men. AIDS Care, 26(8), 1050–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2014.906548

Bryant, R., Harris, L., & Bird, K. (2016). Investing in boys and young men of color. National Civic Review, 105(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncr.21257

Burke, N. J., Hellman, J. L., Scott, B. G., Weems, C. F., & Carrion, V. G. (2011). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(6), 408–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.02.006

Carney, J. V., Kim, H., Hazler, R. J., & Guo, X. (2017). Protective factors for mental health concerns in urban middle school students: The moderating effect of school connectedness. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18780952

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (2013). Overview of adverse child and family experiences among US children. Data Resource Center for Child & Adolescent Health. https://www.childhealthdata.org/docs/drc/aces-data-brief_version-1-0.pdf?Status=Master

Copeland, W. E., Shanahan, L., Hinesley, J., Chan, R. F., Aberg, K. A., Fairbank, J. A., van den Oord, E. J. C. G., & Costello, E. J. (2018). Association of childhood trauma exposure with adult psychiatric disorders and functional outcomes. JAMA Network, 1(7). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4493

Cronholm, P. F., Forke, C. M., Wade, R., Bair-Merritt, M. H., Davis, M., Harkins-Schwarz, M., Pachter, L. M., & Fein, J. A. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(3), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.001

Denham, S. A., Bassett, H. H., Way, E., Mincic, M., Zinsser, K., & Graling, K. (2012). Preschoolers’ emotion knowledge: Self-regulatory foundations, and predictions of early school success. Cognition and Emotion, 26(4), 667–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.602049

Dodge, K. A., Lansford, J. E., Burks, V. S., Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., Fontaine, R., & Price, J. M. (2003). Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Development, 74(2), 374–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.7402004

Dyce, C. M., Albold, C., & Long, D. (2013). Moving from college aspiration to attainment: Learning from one college access program. The High School Journal, 96(2), 152–165.

Dye, L. (2014). School counselors’ activities in predominantly African American urban schools: An exploratory study. Michigan Journal of Counseling, 41(1), 18–37. https://doi.org/10.22237/mijoc/1393632120

Edwards, D. (2018). Childhood sexual abuse and brain development: A discussion of associated structural changes and negative psychological outcomes. Child Abuse Review, 27(3), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2514

Eklund, K., & Rossen, E. (2016). Guidance for trauma screening in schools. ACES Connection. https://bit.ly/3xZsoaO

Eklund, K., Rossen, E., Koriakin, T., Chafouleas, S. M., & Resnick, C. (2018). A systematic review of trauma screening measures for children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000244

Elligan, D. (2004). Rap therapy: A practical guide for communicating with youth and young adults through rap music. Kensington Books.

Garcia-Reid, P., Reid, R. J., & Peterson, N. A. (2005). School engagement among Latino youth in an urban middle school context: Valuing the role of social support. Education and Urban Society, 37(3), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124505275534

Glaser, D. (2000). Child abuse and neglect and the brain—A review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00551

Graham, P. W., Yaros, A., Lowe, A., & McDaniel, M. S. (2017). Nurturing environments for boys and men of color with trauma exposure. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20(2), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-017-0241-6

Greene, J. H. (2018). The Multicultural School Counseling Behavior Scale: Development, psychometrics, and use. Professional School Counseling, 22(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18816687

Gross, J. T., Stern, J. A., Brett, B. E., & Cassidy, J. (2017). The multifaceted nature of prosocial behavior in children: Links with attachment theory and research. Social Development, 26(4), 661–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12242

Harper, S. R. (2015). Success in these schools? Visual counternarratives of young men of color and urban high schools they attend. Urban Education, 50(2), 139–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085915569738

Henfield, M. S. (2011). Black male adolescents navigating microaggressions in a traditionally White middle school: A qualitative study. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 39(3), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2011.tb00147.x

Hicken, M. T., Lee, H., Morenoff, J., House, J. S., & Williams, D. R. (2014). Racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension prevalence: Reconsidering the role of chronic stress. American Journal of Public Health, 104(1), 117–123. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301395

Hoff, E., Laursen, B., & Tardif, T. (2002). Socioeconomic status and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Biology and ecology of parenting (2nd ed., pp. 231–252). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Holcomb-McCoy, C., Harris, P., Hines, E. M., & Johnston, G. (2008). School counselors’ multicultural self-efficacy: A preliminary investigation. Professional School Counseling, 11(3), 166–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0801100303

Holland, M. M. (2015). Trusting each other: Student-counselor relationships in diverse high schools. Sociology of Education, 88(3), 244–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040715591347

Hood, W., Bradley, G. L., & Ferguson, S. (2017). Mediated effects of perceived discrimination on adolescent academic achievement: A test of four models. Journal of Adolescence, 54, 82–93.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.11.011

Jaycox, L. H., Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Walker, D. W., Langley, A. K., Gegenheimer, K. L., Scott, M., & Schonlau, M. (2010). Children’s mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: A field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(2), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20518

Jernigan, M. M., & Daniel, J. H. (2011). Racial trauma in the lives of Black children and adolescents: Challenges and clinical implications. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 4(2), 123–141.

https://doi.org/10.1080/19361521.2011.574678

Jimenez, M. E., Wade, R., Jr., Lin, Y., Morrow, L. M., & Reichman, N. E. (2016). Adverse experiences in early childhood and kindergarten outcomes. Pediatrics, 137(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1839

Kim, B. S. K., Cartwright, B. Y., Asay, P. A., & D’Andrea, M. J. (2003). A revision of the Multicultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills Survey-Counselor Edition. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 36(3), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2003.11909740

Kobin, C., & Tyson, E. (2006). Thematic analysis of hip-hop music: Can hip-hop in therapy facilitate empathic connections when working with clients in urban settings? The Arts in Psychotherapy, 33(4), 343–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2006.05.001

Konold, T., Cornell, D., Shukla, K., & Huang, F. (2017). Racial/ethnic differences in perceptions of school climate and its association with student engagement and peer aggression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(6), 1289–1303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0576-1

Landolt, M. A., Cloitre, M., & Schnyder, U. (2017). Evidence-based treatments for trauma related disorders in children and adolescents. Springer.

Laporte, L., Jiang, D., Pepler, D. J., & Chamberland, C. (2011). The relationship between adolescents’ experience of family violence and dating violence. Youth & Society, 43(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X09336631

Layne, C. M., Steinberg, J. R., & Steinberg, A. M. (2014). Causal reasoning skills training for mental health practitioners: Promoting sound clinical judgment in evidence-based practice. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 8(4), 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000037

Le, H.-N., Ceballo, R., Chao, R., Hill, N. E., Murry, V. M., & Pinderhughes, E. E. (2008). Excavating culture: Disentangling ethnic differences from contextual influences in parenting. Applied Developmental Science, 12(4), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888690802387880

Levy, I. (2012). Hip hop and spoken word therapy with urban youth. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 25(4), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2012.736182

Levy, I. P., & Adjapong, E. S. (2020). Toward culturally competent school counseling environments: Hip-hop studio construction. The Professional Counselor, 10(2), 266–284. https://doi.org/10.15241/ipl.10.2.266

Levy, I. P., Cook, A. L., & Emdin, C. (2018). Remixing the school counselor’s tool kit: Hip-hop spoken word therapy and YPAR. Professional School Counseling, 22(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18800285

Levy, I., & Keum, B. T. (2014). Hip-hop emotional exploration in men. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 27(4), 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2014.949528

Matte-Gagné, C., Bernier, A., Sirois, M.-S., Lalonde, G., & Hertz, S. (2018). Attachment security and developmental patterns of growth in executive functioning during early elementary school. Child Development, 89(3), e167–e182. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12807

Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. (2018). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011-2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 23 states. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(11), 1038–1044. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537

Minor, K. A., & Benner, A. D. (2017). School climate and college attendance for Black adolescents: Moving beyond college-going culture. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(1), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12361

Narayan, A. J., Rivera, L. M., Bernstein, R. E., Harris, W. W., & Lieberman, A. F. (2018). Positive childhood experiences predict less psychopathology and stress in pregnant women with childhood adversity: A pilot study of the Benevolent Childhood Experiences (BCEs) scale. Child Abuse & Neglect, 78, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.022

Nassar-McMillan, S. C., Karvonen, M., Perez, T. R., & Abrams, L. P. (2009). Identity development and school climate: The role of the school counselor. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education, and Development, 48(2), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2009.tb00078.x

Ngo, V., Langley, A., Kataoka, S. H., Nadeem, E., Escudero, P., & Stein, B. D. (2008). Providing evidence-based practice to ethnically diverse youths: Examples from the Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) program. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 858–862. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799f19

Patterson, L., Stutey, D. M., & Dorsey, B. (2018). Play therapy with African American children exposed to adverse childhood experiences. International Journal of Play Therapy, 27(4), 215–226.

https://doi.org/10.1037/pla0000080

Perry, B. D., & Pollard, R. (1998). Homeostasis, stress, trauma, and adaptation: A neurodevelopmental view of childhood trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 7(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1056-4993(18)30258-X

Pica-Smith, C., & Poynton, T. A. (2014). Supporting interethnic and interracial friendships among youth to reduce prejudice and racism in schools: The role of the school counselor. Professional School Counseling, 18(1), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001800115

Ratts, M. J., & Greenleaf, A. T. (2017). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: A leadership framework for professional school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18773582

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Reinbergs, E. J., & Fefer, S. A. (2018). Addressing trauma in schools: Multitiered service delivery options for practitioners. Psychology in the Schools, 55(3), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22105

Roth, M. C., Humphreys, K. L., King, L. S., & Gotlib, I. H. (2018). Self-reported neglect, amygdala volume, and symptoms of anxiety in adolescent boys. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 80–89.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.016

Scott, J., Moses, M. S., Finnigan, K. S., Trujillo, T., & Jackson, D. D. (2017). Law and order in school and society: How discipline and policing policies harm students of color, and what we can do about it. National Education Policy Center. http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/law-and-order

September, S. J., Rich, E. G., & Roman, N. V. (2016). The role of parenting styles and socio-economic status in parents’ knowledge of child development. Early Child Development and Care, 186(7), 1060–1078. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2015.1076399

Shi, Q., & Goings, R. (2017). What do African American ninth graders discuss during individual school counseling sessions? A national study. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18778803

Singh, A. A. (2019). The racial healing handbook: Practical activities to help you challenge privilege, confront systemic racism, and engage in collective healing. New Harbinger.

Skiba, R. J., Horner, R. H., Chung, C.-G., Rausch, M. K., May, S. L., & Tobin, T. (2011). Race is not neutral: A national investigation of African American and Latino disproportionality in school discipline. School Psychology Review, 40(1), 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2011.12087730

Smith, J. R., & Patton, D. U. (2016). Posttraumatic stress symptoms in context: Examining trauma responses to violent exposures and homicide death among Black males in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(2), 212–223. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000101

Smith, L. C., Garnett, B. R., Herbert, A., Grudev, N., Vogel, J., Keefner, W., Barnett, A., & Baker, T. (2017). The hand of professional school counseling meets the glove of restorative practices: A call to the profession. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18761899

Steinberg, L., Elmen, J. D., & Mounts, N. S. (1989). Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic success among adolescents. Child Development, 60(6), 1424–1436. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130932

Stewart, P. E., & Ames, G. P. (2014). Using culturally affirming, thematically appropriate bibliotherapy to cope with trauma. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 7(4), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-014-0028-6

Sue, D. W., Alsaidi, S., Awad, M. N., Glaeser, E., Calle, C. Z., & Mendez, N. (2019). Disarming racial microaggressions: Microintervention strategies for targets, White allies, and bystanders. American Psychologist, 74(1), 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000296

Swan, K. L., Schottelkorb, A. A., & Lancaster, S. (2015). Relationship conditions and multicultural competence for counselors of children and adolescents. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(4), 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12046

Umberson, D., Thomeer, M. B., Williams, K., Thomas, P. A., & Liu, H. (2016). Childhood adversity and men’s relationships in adulthood: Life course processes and racial disadvantage. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 71(5), 902–913. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv091

Von Cheong, E., Sinnott, C., Dahly, D., & Kearney, P. M. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and later-life depression: Perceived social support as a potential protective factor. BMJ Open, 7(9). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013228

Washington, A. R. (2018). Integrating hip-hop culture and rap music into social justice counseling with Black males. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(1), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12181

Wheeler, N. J., Daire, A. P., Barden, S. M., & Carlson, R. G. (2018). Relationship distress as a mediator of adverse childhood experiences and health: Implications for clinical practice with economically vulnerable racial and ethnic minorities. Family Process, 58(4), 1003–1021. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12392

Whitfield, C. L., Anda, R. F., Dube, S. R., & Felitti, V. J. (2003). Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults: Assessment in a large health maintenance organization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(2), 166–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260502238733

Wiet, S., & Trauma-Resiliency Collaborative. (2019). Health-Resiliency-Stress Questionnaire. https://trcutah.org/hrsq

Williams, J., Steen, S., Albert, T., Dely, B., Jacobs, B., Nagel, C., & Irick, A. (2015). Academically resilient, low-income students’ perspectives of how school counselors can meet their academic needs. Professional School Counseling, 19(1), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-19.1.155

Zare, M., Narayan, M., Lasway, A., Kitsantas, P., Wojtusiak, J., & Oetjen, C. A. (2018). Influence of adverse childhood experiences on anxiety and depression in children aged 6 to 11 years. Pediatric Nursing, 44(6), 267–274, 287.

Appendix

Resources and Ideas for School Counselors Developing Multicultural Awareness

| Self-examination and self-assessment |

| Self-reflection, journaling (Singh, 2019), seeking supervision, or consultation with peers

Formal assessment tools

School Counseling Multicultural Self-Efficacy Scale (SCMES; Holcomb-McCoy et al., 2008)

Multicultural School Counseling Behavior Scale (MSCBS; Greene, 2018)

Multicultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills Survey-Counselor Edition (MAKSS-CE; Kim et al., 2003) |

| Building knowledge of traumatic stressors and their impact |

| Impact of primarily White environments on Black youth, such as stereotypes, microaggressions, and assumptions of deviance aimed at Black boys (Henfield, 2011)

Importance of helping young Black males to develop a positive racial identity and agency to recognize and navigate discriminatory experiences (Jernigan & Daniel, 2011)

Impact of exposure to community violence on reported PTSD symptoms (J. R. Smith & Patton, 2016)

Access to resources (e.g., community, school, and intrapersonal resources) leading to decreases in behavioral health needs (Accomazzo et al., 2015) |

| Fostering a nurturing school environment |

| Link students to out-of-school sports, community, and mentoring programs (Graham et al., 2017)

Increase sense of belonging within the school (Shi & Goings, 2017)

Increase levels of school connectedness (Carney et al., 2017)

Foster resilience through tapping into students’ aspirational and social capital (Williams et al., 2015)

Bridge gaps between cultural groups through interventions with all stakeholders (Bell & Van Velsor, 2017)

Promote interethnic friendships in students to combat prejudice and racism (Pica-Smith & Poynton, 2014) |

| Assessment and intervention tools for use with students |

| Universal screening of trauma and behavioral health in schools (Belser et al., 2016; Reinbergs & Fefer, 2018)

Programming that promotes adaptive coping and self-expression (Graham et al., 2017)

Forgiveness interventions (Baskin et al., 2015)

Socially relevant and empowering messages in hip-hop lyrics (Levy et al., 2018; Washington, 2018)

Culturally affirming bibliotherapy (Stewart & Ames, 2014)

Play therapy (Patterson et al., 2018) |

Shaywanna Harris, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at Texas State University. Christopher T. Belser, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at the University of New Orleans. Naomi J. Wheeler, PhD, NCC, LMHC, is an assistant professor at Virginia Commonwealth University. Andrea Dennison, PhD, is an assistant professor at Texas State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Shaywanna Harris, Texas State University, CLAS Dept., 601 University Dr., San Marcos, TX 78666, s_h454@txstate.edu.

Nov 27, 2019 | Volume 9 - Issue 4

Margaret R. Lamar, Elysia Clemens, Adria Shipp Dunbar

Conceptualizing doctoral training programs as research training environments (RTEs) allows for the exploration of theory to help counselor educators facilitate doctoral students’ development from practitioners toward counseling researchers. Researchers have proposed self-concept theory as a way to understand identity development. In this article, the authors applied self-concept theory to understand how researcher identity may develop in a counseling RTE. Organizational theory also is described, as it provides insight for how doctoral students are socialized to the profession. Suggestions are made for how counselor education programs can utilize self-concept theory and organizational theory to create positive RTEs designed to facilitate researcher development.

Keywords: doctoral students, development, researcher identity, research training environments, self-concept theory

Conceptualizing doctoral training programs as research training environments (RTEs) allows for the exploration of theories to help counselor educators facilitate doctoral students’ development from having an identity primarily focused on being a helper toward a research identity (Gelso, 2006). Gelso (2006) defined RTEs as all “forces in graduate training programs . . . that reflect attitudes toward research and science” (p. 6). The RTE includes formal coursework; interactions with faculty, other students, and staff; informal mentoring experiences; and institutional culture that promotes or devalues research. However, there is little information about how counselor educators can practically develop a systematic approach to creating positive RTEs that facilitate the development of counselor education and supervision (CES) doctoral student researchers.

It is important to attend to the RTE because it has an impact on the researcher’s identity, researcher self-efficacy, research interest, and scholarly productivity of CES doctoral students (Borders, Wester, Fickling, & Adamson, 2014; Gelso, 2006; Gelso, Baumann, Chui, & Savela, 2013; Kuo, Woo, & Bang, 2017; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Lambie, Hayes, Griffith, Limberg, & Mullen, 2014; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011). Researchers have found that CES doctoral student research self-efficacy and research interest were related to productivity (Kuo et al., 2017; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011). Research self-efficacy is defined as the belief one has in their ability to engage in research tasks (Bishop & Bieschke, 1998). A related but separate construct, research interest is the desire to learn more about research. Lambie and Vaccaro (2011) found that doctoral students with scholarly publications had higher research self-efficacy and research interest, while Kuo et al. (2017) found that scholarly productivity can be predicted by research self-efficacy and intrinsic research motivation. Given that most CES doctoral students enter their programs with little research experience (Borders et al., 2014), the RTE likely contributes to a doctoral student’s ability to gain research and publication experience. However, much of the early exposure to research in counselor education rests primarily on research coursework, not extracurricular experiences, such as working on a manuscript with a faculty member (Borders et al., 2014). Though some programs provide systematic extracurricular non-dissertation research experiences, about half of the CES programs surveyed by Borders et al. (2014) offered no structured research experiences early in the program sequence or relied on doctoral students to create their own opportunities. Lamar and Helm (2017) found that the RTE, including faculty mentoring and research experiences, was an essential part of CES doctoral student researcher identity development. Given prior findings (Borders et al., 2014; Kuo et al., 2017; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011), it seems crucial for CES doctoral faculty to systematically create an RTE that is conducive to CES doctoral student researcher identity, research self-efficacy, and research interest development.

Leadership in the counseling field has stressed the importance of research in furthering the profession by stating that “expanding and promoting our research base is essential to the efficacy of professional counselors and to the public perception of the profession” (Kaplan & Gladding, 2011, p. 372). Therefore, it is essential to strengthen the training of future researchers so they are successful at achieving this vision. Thus, there are two primary purposes of this manuscript: 1) propose that the state of research in the field of counselor education is a reflection, in part, of an RTE issue; and 2) provide practical ways for programs to facilitate researcher development among doctoral students. The authors provide insight on how self-concept theory and organizational development theory may be a useful means for conceptualizing researcher development and facilitating change in RTEs.

Self-Concept Theory

Self-concept theory provides a framework for conceptualizing the way a person organizes beliefs about themselves. Purkey and Schmidt (1996) defined self-concept theory as “the totality of a complex and dynamic system of learned beliefs that an individual holds to be true about their personal experience” (p. 31). Learned beliefs are subjective and not necessarily based on reality but instead are reflections of individuals’ perceptions of themselves. These perceptions are related to past experiences and expectations about future goals. Purkey and Schmidt (1996) suggested conceptualizing the self-concept using the following categories: (a) organized, (b) learned, (c) dynamic, and (d) consistent. Discussions of each of these categories are presented in the context of applying self-concept theory to researcher development.

Current counselor training literature has discussed the development of student professional counselor identity (e.g., Prosek & Hurt, 2014); however, until recently (e.g., Jorgensen & Duncan, 2015; Lamar & Helm, 2017), counseling professional identity literature has not included a focus on how research is integrated into a student’s identity. Self-concept theory can be used to conceptualize the inclusion of researcher identity into the professional identity of CES doctoral students.

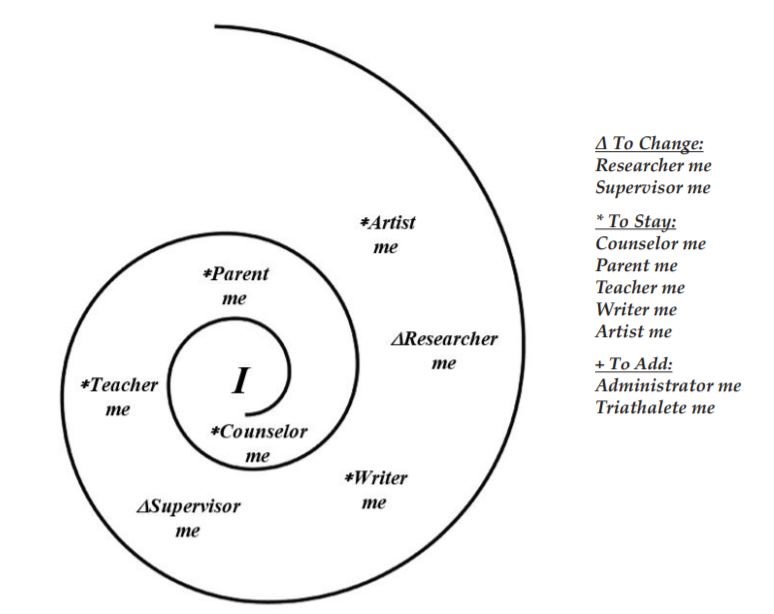

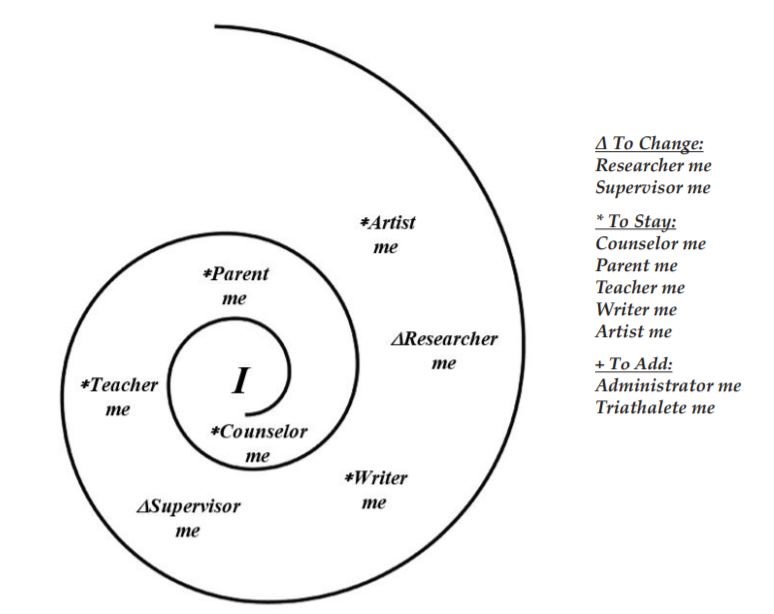

Organization of the Self-Concept

Purkey and Schmidt (1996) used a spiral as a visual representation of how the self is organized (Figure 1). They referred to the sense of self, or overarching view of who you are, as the central I, and placed it at the very center of the spiral. In addition, people also have other specific identities, or what Purkey and Schmidt termed me’s, that inform their global identity. These multiple identities can be considered hierarchical, meaning that one of the me identities might be more important to a person than another aspect of their identity and is placed more proximal to the central I on the spiral than more distal me’s. Developmentally, it makes sense that a beginning CES doctoral student, for example, may have a stronger counselor me (located closer to their central I), whereas their researcher me might be located closer to the periphery of the spiral. This is confirmed through previous research findings suggesting that CES students enter doctoral programs with stronger helper identities and integrate research into their self-concept throughout their academic experience (Gelso, 2006; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011). It would be expected that these me’s would be more likely to shift throughout the course of a doctoral program with greater exposure to a positive RTE. The relative importance of these identities to a doctoral student’s professional identity is illustrated for exemplary purposes in Figure 1. Faculty have a significant role in creating positive RTEs so that a doctoral student’s researcher me can be strengthened and become more fully integrated into their self-concept.

Figure 1. Self-Concept Spiral

Learning for a Lifetime

Developing the self-concept is a task that takes a lifetime of learning (Purkey & Schmidt, 1996). Self-

concept learning occurs in three ways: (a) exciting or devastating events, (b) professional helping relationships, and (c) everyday experiences. Individually, and in combination, these experiences can reorganize and shape a person’s self-concept. For example, receiving a first decision letter from an editor can be an exciting or devastating event that influences a doctoral student’s self-concept. Faculty members can process and contextualize the experience so a doctoral student’s researcher self-concept is positively promoted (e.g., a lengthy revise and resubmit letter can feel overwhelming but is a fantastic outcome; Gelso, 2006; Lamar & Helm, 2017). Similarly, the counseling RTE can promote positive research attitudes for doctoral students on a daily basis (e.g., displaying examples of student and faculty research).

Dynamic and Consistent Self-Concept Processes

Self-concept is dynamic; it is constantly changing and has the potential to propel doctoral student researchers forward (Purkey & Schmidt, 1996). Change occurs when a doctoral student incorporates new beliefs into existing ones. When new information is presented to the doctoral student, contrary to what they currently believe about themselves (e.g., ability to understand the methods section of an article), they are challenged to merge the new information with their current beliefs (e.g., “I’m a clinician,” and skip to the implications section). As they revise their belief system, they may be able to behave in new ways (e.g., making connections between the methods section and clinical application or engaging in critical discussions of research). However, reconciling new beliefs about their self-concept and demonstrating new research skills can be challenging. Consistency is highly valued by doctoral students faced with a need to adopt new ideas into their self-concept (Purkey & Schmidt, 1996). A doctoral student may experience what is commonly known as imposter syndrome, which occurs when a student is unable to internalize their accomplishments and attributes their success to good luck (Parkman, 2016). As CES doctoral students become proficient in research pursuits, they may still have difficulty seeing themselves as researchers (e.g., articulating hesitancy to share findings with peers or at professional conferences). They might tell others they are a counselor, a teacher, or a supervisor and they also conduct research, thus distancing that identity from the core of their self-concept (Lamar & Helm, 2017). They may need to repeatedly have their new researcher identity confirmed by faculty and their own personal experiences before they can communicate a fully integrated self-concept to others.

As learning occurs, the self-concept reorganizes toward a more stable professional identity. Incorporation of a researcher identity into their self-concept is likely to be dynamic, with consistency increasing throughout the doctoral students’ academic program. As CES doctoral students move into new stages of their career, their researcher identity is likely to become a more fixed aspect of their self-concept.

Development of the self-concept occurs in a CES doctoral program, which exists within the larger academic culture. Doctoral students are initially presented with the challenge of navigating a new culture. The culture of academe has its own processes, language, and roles. In addition to development of their researcher self-concept, doctoral students also must integrate their roles within higher education into their self-concept.

Organizational Development

A primary goal of doctoral education is to prepare and acculturate doctoral students to their future professional life as counselor educators (Austin, 2002; Johnson, Ward, & Gardner, 2017; Weidman & Stein, 2003). Many doctoral students in CES programs will pursue a CES faculty position within higher education organizations. Higher education organizations demonstrate various forms of culture and socialization processes (Tierney, 1997). University cultural norms include expectations for how to act, what to strive for, and how to define success and failure. Graduate education literature has included discussions on helping doctoral students transition into faculty life and university organizational culture (e.g., Austin, 2002; Austin & McDaniels, 2006). This socialization process has not been extensively discussed in the counselor training literature, yet there is potential for it to be useful in creating positive RTEs.

Socialization Into the Academy

Socialization is the process by which doctoral students learn the culture of an institution, including both the spoken and unspoken rules (Johnson et al., 2017). The process of socializing doctoral students to graduate school is a part of a greater socialization to higher education (Gardner & Barnes, 2007). Weidman, Twale, and Stein (2001) described four stages and characterized three elements of socialization—knowledge acquisition, investment, and involvement—that are experienced over the four stages. These stages provide insight for doctoral programs looking to provide intentional support for their students acclimating to the RTE within higher education.

Anticipatory stage. Doctoral students begin developing an understanding of the organizational culture even before they start a program of study (Clarke, Hyde, & Drennan, 2013; Weidman et al., 2001). During recruitment and introduction to the program, doctoral students gather information about the program (knowledge acquisition), decide to enroll (investment), and begin to make sense of organizational norms, expectations, and roles (involvement). CES doctoral students are, therefore, entering counseling programs with preconceived ideas about their roles as students, including their function as student researchers.

Formal and informal stages. The formal and informal stages co-occur but are differentiated in that the formal stage is more faculty or program driven, whereas the informal stage is peer socialization (Gardner, 2008; Weidman et al., 2001). Some of the formal stage methods of socialization can include classroom instruction, faculty direction, and focused observation. Courses grounded in the 2016 Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) standards related to doctoral professional identity or research are part of the formal socialization process. Out-of-classroom conversations with faculty and other university staff orient doctoral students to the value of research in the program and university. Doctoral students learn through faculty direction and observation about networking at conferences, publishing, and what types of research are considered valuable in the field. Students also observe faculty working around obstacles to keep their own research active. These examples are all consistent with knowledge acquisition.

Informal socialization happens as new doctoral students observe and learn how more advanced students and incoming cohorts define norms (Gardner, 2008). This stage has many parallels to existing research about how faculty acculturate to new organizations. Tierney and Rhoads (1994) proposed new faculty members learn the culture of the organization in mostly informal ways. As they observe the established tenured faculty, new faculty learn what is important to the department and develop understanding about the institution’s priorities. This acculturation process is important because it is likely to impact the RTE faculty create for doctoral students.

Similarly, doctoral students learning about culture, investment, and involvement in research are likely guided by the knowledge they acquire through observing and engaging with more advanced doctoral students in their programs of study (Gardner, 2008; Gelso, 2006). Acquisition of knowledge, occurring “through exposure to the opinions and practices of others also working in the same context” (Mathews & Candy, 1999, p. 49), creates norms among doctoral students. Norms regarding participation in research, such as whether it is done only to meet degree requirements or with more intrinsic motivation, may be conveyed across cohorts. Lamar and Helm (2017) found CES doctoral students were intrinsically motivated by their research when it was connected to their counselor identity and they could see how their research would help their clients. Jorgensen and Duncan (2015) identified external facilitators, such as faculty, coursework, and program expectations, that shaped the researcher identity development of master’s counseling students. Faculty communicated the culture of the institution and indirectly communicated their own intrinsic motivation, or lack of it, through their research activity. New students also gain insight from advanced doctoral students about the degree to which research should be aligned with faculty members and the more subtle messages about departmental expectations. For example, is qualitative research supported and valued as much as quantitative? Are certain research methodologies prioritized by faculty or the institution? The combination of formal and informal socialization leads to an understanding of the academic organization and counselor education profession.