Aug 24, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 2

Chloe Lancaster, Michelle W. Brasfield

The COVID-19 pandemic led to an unparalleled disruption of student learning, disengaged students from school and peers, increased exposure to trauma, and had a negative impact on students’ mental health and well-being. School counselors are the most accessible mental health care professionals in a school, providing support for all students’ social and emotional needs and academic success. This study used an exploratory survey design to investigate the perspectives of 207 school counselors in Tennessee regarding students’ COVID-19–related mental health, academic functioning, and interpersonal skills; interventions school counselors have deployed to support students; and barriers they have encountered. Results indicate that students’ mental health has significantly declined across all grade levels and is interconnected with academic, social, and behavioral problems; school counselors have provided support consistent with crisis counseling; and caseload and non-counseling duties have created significant barriers in the provision of care.

Keywords: COVID-19, school counselors, student mental health, interventions, barriers

The psychological cost of the COVID-19 pandemic has been profound and wide-reaching. Although the K–12 population has been less susceptible to the adverse physical effects of COVID-19, for many, the pandemic has left an indelible mark on their mental health (Karaman et al., 2021). Before the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, youth mental health had become an issue of national concern, with one in six minors struggling with mental illness (Whitney & Peterson, 2019). Research has emerged to indicate that COVID-19 has further elevated the mental health problems of K–12 students across the nation (Ellis et al., 2020; Karaman et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021). The end of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions may have alleviated immediate issues associated with social isolation and online learning; however, for those students experiencing COVID-19–related trauma and crisis, symptomatology has persisted beyond school reentry (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2022; Patterson, 2022). As frontline helping professionals with training in mental health and school systems, school counselors are often the first responders to students in crisis (Karaman et al., 2021; Lambie et al., 2019), yet researchers have not explored reentry problems from the school counselor’s perspective. We conducted this study to understand school counselors’ experience of COVID-19–related student issues, their strategies to assist students, and their encountered barriers. We theorized that persistent problems related to the organizational structures within which counselors work, such as large caseloads, assignment of non-counseling duties, and under-resourced schools and communities (Lambie et al., 2019), may have greatly impacted their ability to meaningfully help students in high need of mental health support.

Literature Review

Students and COVID-19–Related Distress

From the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, scholars predicted that disruptions to schooling, COVID-19–related stress, family conflict, and frequent media exposure to the pandemic would amplify mental health problems in children and youth (Imran et al., 2020). Empirical studies published in 2020 and 2021 have substantiated this concern, with findings indicating that COVID-19 restrictions adversely affected youth in multiple ways, including the development of unhealthy eating habits, increased screen time, reduced physical activity, sleep disturbances, academic delays, social problems, and an overall escalation in mental health concerns (Ellis et al., 2020; Karaman et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021). The preponderance of research focused on adolescents, particularly as extended time in social isolation disrupted their developmental reliance on peer interactions for social and emotional support (Imran et al., 2020). Multiple studies found that not feeling connected to friends, high social media usage, and general COVID-19–related fears were associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety (Ellis et al., 2020; Karaman et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021).

Although less is known about the impact of COVID-19 on younger children, evidence is emerging to indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has elevated adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; Bryant et al., 2020). From a developmental perspective, children are less able to communicate and process their thoughts and feelings and are greatly affected by the emotional state of their caregivers (Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, 2011). Thus, exposure to parental anxieties related to housing, food, and economic insecurity likely exerted a destabilizing effect on children during the stay-at-home mandate and beyond (Imran et al., 2020). Further, children in poverty may be particularly vulnerable to an amplification of ACEs due to their families being disproportionately impacted by economic hardships and family mortality during the pandemic (Bryant et al., 2020).

Students’ Mental Health Pre-Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic increased intra-family adversity, which has long-term implications for the well-being of children and adolescents (CDC, 2022). However, in pre–COVID-19 times, with the rise in school shootings and teen suicide, the mental health of K–12 populations had already become a public health concern. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, one in six children aged 6–17 experienced a mental health disorder (Whitney & Peterson, 2019). Since reentry following COVID-19 shutdowns, indicators suggest the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened children’s mental health (CDC, 2022; Karaman et al., 2021), with widespread reports of student learning gaps, chronic absenteeism, declines in social skills, and increased behavior problems (CDC, 2022; Patterson, 2022). Further, previous research on children’s responses to a variety of traumatic events has found that children and adolescents can develop long-term mental illness following a traumatic experience, which is unlikely to abate without intervention (Udwin et al., 2000). For youth, the experience of mental health problems increases their risk factors in other areas, such as a decline in academic performance, poor decision-making, drug use, and high-risk sexual behaviors (CDC, 2022). In this regard, the responsiveness of schools to flex their organizational resources to address the psychological changes in their student body seems instrumental in assuaging the long-term effects of COVID-related trauma and the mitigation of adverse educational outcomes (Savitz-Romer et al., 2021).

School Counselors’ Role in Provision of Mental Health Services

Schools have long been discussed as a primary access point for mental health services, given that children spend much of their day in school, and children and adolescents in need of mental health care are more likely to receive assistance in a school as opposed to a clinical setting (Lambie et al., 2019). Conversations about students’ access to mental health care in school settings segue to the role of school counselors and students’ access to school counseling services. School counselors are the most accessible mental health care professionals in schools, with 80.7% of schools employing full-time or part-time school counselors (Lambie et al., 2019). By contrast, only 66.5% employ a school psychologist, and 41.5% employ a school social worker (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2016). Further, school counselors are trained in crisis prevention and responsive services, including individual and group counseling; consultation with administrators, teachers, parents, and professionals; and coordination of services within a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS; Pincus et al., 2020).

Evidence to support school counselors’ work in times of crisis comes from multiple sources. Salloum and Overstreet (2008) found that a school counselor–led small group implemented after Hurricane Katrina improved PTSD symptoms among elementary school students. Similarly, Udwin and colleagues (2000) found that students who received psychological support at school following a national crisis experienced a reduction in PTSD symptomology. Additionally, scholars have proposed that school counselors utilize their skill set in assessment to administer universal mental health screenings to identify students at greater risk of having or developing mental health concerns (Lambie et al., 2019; Pincus et al., 2020).

Barriers School Counselors Face in the Provision of Services

Although school counselors have the training and skills necessary to assist students transitioning back to school from a disruption like COVID-19, they face multiple barriers to their work. Most notably, they struggle with unmanageable caseloads. The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) recommends that counselor-to-student ratios not exceed 1:250 (ASCA, 2019). Yet, the average ratio in the United States is 1:455, with Tennessee experiencing an average ratio of 1:450 (Patel & Clinedinst, 2021). Research indicates that large school counselor caseloads adversely affect student outcomes, insofar as attendance, graduation, and disciplinary problems are more prevalent in schools with high school counselor caseloads (Parzych et al., 2019). Unfortunately, minority students in under-resourced schools are disproportionately impacted by high counselor ratios (Whitney & Peterson, 2019) and are more likely to experience adverse educational outcomes, as well as unmet mental health needs (Kaffenberger & O’Rorke-Trigiani, 2013). These findings raise concern for students whose mental health and academics have declined since the emergence of COVID-19 who attend schools with overstretched counselors struggling to meet the needs of their student body. This study was conducted in part to explore if caseload correlates to school counselors’ perceived ability to attend to students’ COVID-related problems and if differences were more pronounced in schools with lower socioeconomic status (SES).

In addition to ratios, ASCA recommends that school counselors spend 80% of their time providing direct and indirect services to students. Program elements within direct service include curriculum delivery, individual student planning, and responsive services. Indirect services include referrals to other agencies and programs within and outside the school system and consultation and collaboration with stakeholders, particularly for crisis response (ASCA, 2019). Researchers have documented the favorable effects on student academics and behaviors when school counselors follow these national guidelines for time and role allocations (Cholewa et al., 2015). Nonetheless, school counselors are often assigned non-counseling duties by their campus and district administrators (Gysbers & Henderson, 2012), preventing them from fulfilling their appropriate roles. These duties include test coordination, record keeping, attendance monitoring, substitute teaching, and student discipline (ASCA, 2019). Data indicate that non-counseling duties may be more problematic at the secondary level, with high school counselors over-reporting non-counseling duties, when compared to elementary school counselors (Chandler et al., 2018). Geographic differences have also been documented, with rural school counselors reporting higher levels of non-counseling duties in comparison to urban school counselors (Chandler et al., 2018). In the current study, we were curious to understand the impact of non-counseling duties on school counselors’ response to students’ COVID-19 concerns and to explore the intersection of counselor responsiveness to COVID-19 by non-counseling duties, grade level, and geographic region (e.g., urban, suburban, rural), respectively.

School Responses to COVID-19 in Tennessee

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Tennessee’s governor ordered all Tennessee public schools closed from March 20 until March 31, 2020, and extended this closure through the end of the 2019–2020 school year. To complete the school year outside of the physical educational space, districts created their own plans to address student learning, often dependent on available technology and resources (Tennessee Office of the Governor, 2020). Districts made decisions for returning in the fall 2020 semester based on guidelines from the Tennessee Department of Education (DOE), which included social distancing, smaller class size, assigned seats, and alternating in-person days with distance learning (Tennessee DOE, 2020). To provide further context to our survey responses, in 2019, the state DOE (Tennessee State Board of Education, 2017) updated its school counseling policy and standards to require school counselors to spend 80% of their time in direct service to students, a specification consistent with the ASCA National Model for allocation of school counselor time. Although the policy stated counselor ratios should not exceed 1:500 in elementary and 1:350 in secondary schools, this specification falls short of the ASCA 1:250 recommendation. Further, because of the state funding formula that permits school districts to hire administrators in lieu of school counselors, depending on school needs, we expected many of the school counselors would have caseloads that exceeded DOE policy.

Purpose of Study

School counselors are uniquely positioned to assist students with their mental health, including COVID-19–related concerns, in a school context (Pincus et al., 2020). Yet, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, school counseling programs were frequently under-equipped to meet the magnitude of students’ mental health needs (DeKruyf et al., 2013). This study was conducted to understand, from the perspective of school counselors in Tennessee, the ongoing impact of COVID-19 upon students’ mental health, examine strategies they have deployed to assist students, and discover barriers encountered in providing care to meet their students’ needs. Because poor mental health manifests in a plethora of academic, behavior, and social skill adjustment issues for children and adolescents (CDC, 2022), we also examined school counselors’ perceptions of changes in those domains from pre-pandemic to current times. Given documented patterns of variability in school counselor programs, we also investigated school counselors’ perceived barriers to assisting students by location, SES, and assigned non-counseling duties. To address the aim of the study, we posited three related research questions (RQs):

| RQ1: |

How has COVID-19 affected students’ mental health, academics, and social skills in Tennessee? What issues presented the greatest concern, and how did interventions differ by grade level (elementary, middle, or high school)? |

| RQ2: |

What interventions do school counselors in Tennessee use to assist students with their COVID-19–related concerns, and how do interventions differ by grade level (elementary, middle, or high school)? |

| RQ3: |

What barriers do school counselors in Tennessee report as interfering with their ability to address students’ COVID-19 concerns? Do reported barriers differ by grade level (elementary, middle, or high), location (urban, suburban, or rural), socioeconomic status, non-counseling duties, size of caseload (small, medium, or large), or following the state guideline for spending 80% of the time in student services? |

Method

Study Design and Instrumentation

Given the absence of research examining school counselors’ perspectives of how the pandemic has affected student mental health, their response to students’ COVID-19 issues, and barriers encountered in their efforts, we employed an exploratory research design. Exploratory designs are used when there is limited prior research to warrant the examination of a directional hypothesis (Swedberg, 2020). Within the framework of an exploratory design, we developed a non-standardized instrument to answer the three research questions. Although this constitutes a limitation of the study, we endeavored to address validity concerns by following the principles of the tailored design method of survey research (Dillman, 2007). Prior to constructing the survey, we reviewed the extant literature on students’ COVID-19–related issues, school counselors’ roles, and professional issues, in addition to conducting a focus group (N = 7) with school counselors and school counseling supervisors from across the state in which the study was conducted to explore their perceptions in changes to student functioning, strategies they have deployed to assist students, and obstacles they have encountered. Focus group data were used to inform the development of survey items and ensure the instrument covered relevant content. For example, the focus group provided expert insight into the non-counseling duties that are frequently assigned to counselors in the state, as well as the nature of students’ psychological, academic, and behavioral problems witnessed since the onset of COVID-19. Before launching the survey, we piloted the survey with 19 school counselors in Tennessee to elicit feedback about the flow and coverage of the survey. Based on their responses, we added an item addressing universal intervention and edited language on multiple items to align with state-specific terminology (e.g., “MTSS coordination” was expanded to “RTI2B/MTSS/PBIS coordinator” to reflect more state-recognized school counselor titles when operating in these capacities).

The final survey consisted of 64 items in predominantly binary, checkbox, and Likert scale formats. Demographic items were informed by categories outlined by the U.S. Census, the Tennessee DOE, and inclusive practices for data collection (Fernandez et al., 2016). Twenty-one items gathered demographic data related to school counselor characteristics (e.g., age, race, gender), counseling program variables (e.g., caseload, division of time, non-counseling duties, fair-share responsibilities), and school variables (e.g., school level, Title I status, location, staffing patterns). SES was measured using a school’s designated Title I status, with response categories of “yes,” “no,” and “unsure.” Likewise, to determine if school counselors dedicated 80% of their time to direct service, we created a multiple-choice item with the options of “yes,” “no,” and “unsure.” A concise description of the state guidelines was embedded into the survey to promote accurate responses to this item. We gathered data on counselors’ perspectives of their students’ current functioning in areas of mental health, academics, social skills, and behaviors through multiple-choice items with a 5-point range of “much better” to “much worse.” For each area of functioning, school counselors were required to indicate the areas of concern via a checkbox item. Additionally, checkbox items were used to identify school counselors’ strategies to assist students, barriers encountered, and needed resources. As noted, these response categories were based on extant literature and expert input.

Cronbach’s alphas were computed to determine the reliability of the survey items in indicating overall post–COVID-19 functioning of students according to school counselors. These values indicate that these four areas were moderately related with acceptable consistency (α = .653). When making additional comparisons among the four constructs, two areas—behavior and social skills—were found to be more consistent (α = .705; Sheperis et al., 2020). Further, reliability scores likely reflect the exploratory design, which requested participants respond to conceptually related but not converging constructs (e.g., academics, mental health, social skills, and behavior). For example, a change in student academics would not necessarily signify a change in student mental health and vice versa. Thus, participant responses would not necessarily be uniform across items measuring students’ mental health, academics, and social skills, and overall instrument consistency would not be affected in turn.

Participants

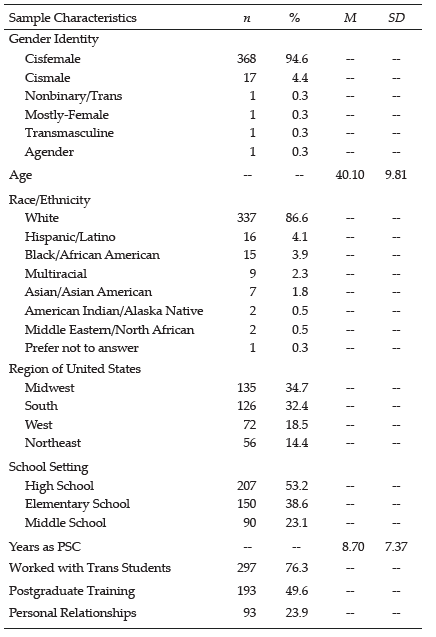

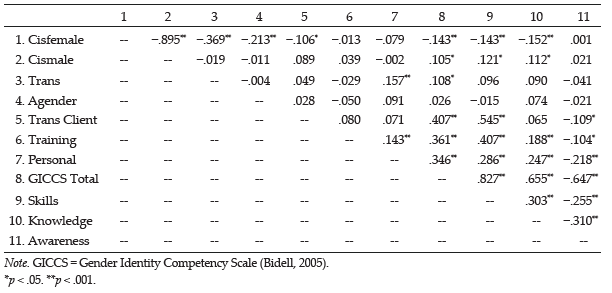

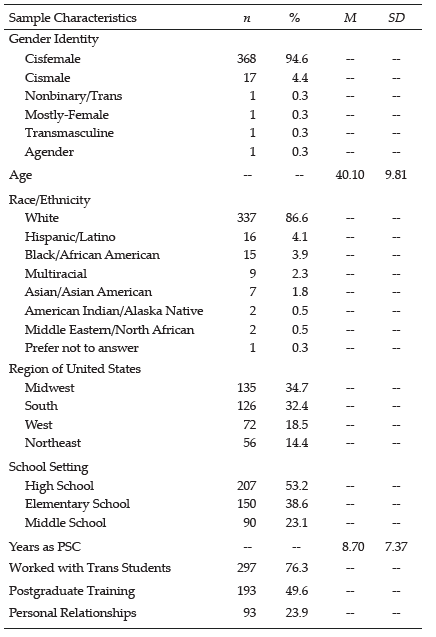

We recruited a state-level sample of professional school counselors employed in K–12 public schools in Tennessee. Following the pilot study, in December 2021, we recruited participants through an anonymous Qualtrics link utilizing multiple platforms: the state school counselor association’s listserv, social media, respondent referrals, and dissemination via school counseling supervisors. Participants were eligible to complete the survey if they were currently employed in a K–12 public school in Tennessee. Upon examination of our survey data, we found 276 total responses with 220 complete for a completion rate of 79.7%. Because the survey was distributed through the above-mentioned methods, we were unable to calculate the response rate without knowing how many of the approximately 2,000 public school counselors in Tennessee received the survey. Upon further examination of the survey respondents, we removed one school counseling supervisor; four school counselors whose students were remote/hybrid; and eight school counselors in private, charter, or alternative schools to maintain focus on the experiences of traditional public school counselors working with students in person during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic for a final sample of 207 participants. An examination of the respondents’ demographics revealed a sample that was predominantly female and White/Caucasian and worked in Title I, suburban, or rural elementary schools. The sample’s mean years serving as a school counselor was 11.7 (SD = 7.5), with mean years at current school of 6.8 (SD = 6.4). See Table 1 for more demographic information. For analysis purposes, we divided the school counselors into three groups by the size of their reported caseload. These categories were informed by a national study of school counselor ratios (National Association of College Admission Counselors, 2019) and consisted of ratios in the range of small (1:100–1:300; 14.0%, n = 29), medium (1:301–1:550; 69.6%, n = 144), and large (1:551 and higher; 15.0%, n = 31).

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

| Characteristic |

n |

% |

| Age |

|

|

| 18–24 years |

3 |

1.4 |

| 25–44 years |

99 |

47.8 |

| 45–64 years |

102 |

49.3 |

| 65 years plus |

3 |

1.4 |

| Race/Ethnicity |

|

|

| Black/African American |

17 |

8.2 |

| Latinx/Hispanic |

1 |

0.5 |

| White/Caucasian |

183 |

88.4 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native |

1 |

0.5 |

| Other |

5 |

2.4 |

| Gender |

|

|

| Female |

192 |

92.8 |

| Male |

15 |

7.2 |

Note. N = 207.

Data Analysis

We ran a post hoc power analysis using the G*Power 3.1.9.7 statistical software to determine if our sample size was sufficient at the .80 power level with α = .05 and found that a minimum sample size of 100 was required for our analyses. Given our sample size of 207 participants, the power analysis indicated that our sample size was sufficient (Faul et al., 2007). We utilized SPSS version 26 to calculate the following analyses for this study: (a) descriptive statistics; (b) Fisher’s exact test for two dichotomous nominal variables; (c) an extension of Fisher’s exact test, the Freeman-Halton exact test, for one dichotomous nominal variable and one nominal variable with three levels; and (d) point-biserial correlation analysis for one nominal variable and one interval variable (Frey, 2018). We also examined effect size to determine practical importance using the following levels for examining nominal data (Rea & Parker, 1992), precedence for which has been established by complementary studies in educational research (K. Erickson & Quick, 2017; Kotrlik et al., 2011): negligible [0, .1), weak [.1, .2), moderate [.2, .4), relatively strong [.4, .6), strong [.6, .8), and very strong [.8, 1.0). Phi (ϕ) indicates the effect size for the exact tests, and the correlation is the effect size for the point-biserial correlation. We only included statistical analyses that resulted in moderate associations or higher. Three school counselors (1.4%) who reported caseloads that were unusually small (< 100) and outside our specified caseload parameters were removed from the analysis. Additionally, we excluded school counselors who indicated “unsure” in the categories of location (rural, suburban, urban), Title I status, and adherence to state policy for direct service to students. See Table 2 for school characteristics.

Results

Research Question 1

RQ1 examined school counselors’ perspectives of the impact of COVID-19 on students’ mental health, academics, and social skills as well as variation by grade level (elementary, middle, or high school). When asked about the mental health changes they have witnessed in their students post–COVID-19 pandemic, 93.7% (n = 194) of school counselors reported negative changes with 42.5% (n = 88) reporting “much worse” and 51.2% (n = 106) reporting “somewhat worse” changes. Specifically, school counselors reported issues regarding anxiety (92.8%, n = 192), depression (77.3%, n = 160), family dysfunction (71.0%, n = 147), COVID-19–related grief and loss (63.8%, n = 132), technology addiction (52.7%, n = 109), suicidality (50.7%, n = 105), fear of COVID-19 (49.8%, n = 103), substance use issues (21.7%, n = 45), and other issues (12.6%, n = 26) such as separation anxiety, self-harm, and anger. The Freeman-Halton exact test revealed a significant relationship between grade level (n = 183) and depression (p < .001, ϕ = .301) with a moderate positive association, suicidality (p < .001, ϕ = .499) with a relatively strong positive association, and substance use (p < .001, ϕ = .583) with a relatively strong positive association. For depression, 90.0% (n = 54) of high school counselors and 85.7% (n = 36) of middle school counselors reported this issue as compared to 63.0% (n = 51) of elementary school counselors. For suicidality, 76.2% (n = 32) of middle school counselors and 71.7% (n = 43) of high school counselors reported this concern as compared to 23.5% (n = 19) of elementary school counselors. For substance use, 58.3% (n = 35) of high school counselors and 20.0% (n = 8) of middle school counselors reported this concern as compared to 1.2% (n = 1) of elementary school counselors. All other mental health concerns were not significant with grade level.

When queried regarding academic changes post–COVID-19, 90.3% (n = 187) of school counselors reported negative changes to students’ academics with 35.3% (n = 73) reporting “much worse” and 55.1% (n = 114) reporting “somewhat worse” changes. School counselors reported an overall decline across all subjects (80.7%, n = 167). Additionally, school counselors reported non-cognitive factors regarding lack of motivation (84.1%, n = 174), lack of parental support during the school day (75.4%, n = 156), attention issues (71.0%, n = 147), poor mental health (64.7%, n = 134), sleep deprivation (41.1%, n = 85), limited technology during virtual learning (33.3%, n = 69), lack of space to work at home during virtual learning (30.4%, n = 63), poor physical health (17.9%, n = 37), and other (3.9%, n = 8). The Freeman-Halton exact test revealed a significant relationship between grade level (n = 183) and lack of motivation (p = .001, ϕ = .265), poor mental health (p = .001, ϕ = .269), and attention issues (p = .009, ϕ = .232), all with positive moderate associations. For lack of motivation, 96.7% (n = 58) of high school counselors and 88.1% (n = 37) of middle school counselors reported this issue as compared to 75.3% (n = 61) of elementary school counselors. For poor mental health, 78.3% (n = 47) of high school counselors and 69.0% (n = 29) of middle school counselors reported this outcome as compared with 49.4% (n = 40) of elementary school counselors. For attention issues, 79.0% (n = 64) of elementary school counselors and 73.8% (n = 31) of middle school counselors reported concerns as compared to 55.0% (n =33) of high school counselors.

Table 2

School/Program Characteristics

| Characteristic |

n |

% |

| Location |

|

|

| Urban |

31 |

15.0 |

| Suburban |

95 |

45.9 |

| Rural |

72 |

34.8 |

| Unsure |

9 |

4.3 |

| Title I Status |

|

|

| Yes |

121 |

58.5 |

| No |

57 |

27.5 |

| Unsure |

29 |

14.0 |

| Grade Level |

|

|

| Elementary |

81 |

39.1 |

| Middle |

42 |

20.3 |

| High |

60 |

29.0 |

| Other |

24 |

11.6 |

| Follows 80% Direct Service Guideline |

|

|

| Yes |

112 |

54.1 |

| No |

65 |

31.4 |

| Unsure |

30 |

14.5 |

| School Counselor-to-Student Ratio (caseload) |

|

|

| 1:1–1:300 |

29 |

14.0 |

| 1:301–1:550 |

144 |

69.6 |

| 1:551 and higher |

31 |

15.0 |

| Other |

3 |

1.4 |

Note. N = 207

When asked about behavioral changes, 87.4% (n = 181) of school counselors reported negative changes to behaviors with 30.4% (n = 63) reporting “much worse” and 57.0% (n = 118) reporting “moderately worse” changes. Comparably, when asked about social skills changes, 87.0% (n = 180) of school counselors reported negative changes to students’ social skills with 36.2% (n = 75) reporting “much worse” and 50.7% (n = 105) reporting “moderately worse” changes. Specifically, school counselors reported trouble socializing with peers (84.1%, n = 174), absence of social flexibility (58.0 %, n = 120), increase of physical aggression (55.1%, n = 114), increase in relational aggression (50.7%, n = 105), increase in cyberbullying (23.7%, n = 49), increase in bullying (19.3%, n = 40), and other (8.2%, n = 17) such as issues with conflict resolution and preference for technology. The Freeman-Halton exact test revealed a significant relationship between grade level (n = 183) and cyberbullying (p = .003, ϕ = .255), with a moderate positive association with 42.9% (n = 18) of middle school counselors, 23.3% (n = 14) of high school counselors, and 14.8% (n = 12) of elementary school counselors reporting an increase in this area. All other social skills changes were not significant with grade level.

Research Question 2

RQ2 examined the interventions that school counselors used in assisting students with their COVID-19–related concerns and if this differed by grade level. School counselors reported the various supports that they provided to their students who struggled with COVID-19–related issues, including individual counseling (95.7%, n = 198), consultation with parents/teachers (85.5%, n = 177), referrals (80.7%, n = 167), collaboration with other school-based helpers (77.3%, n = 160), coping skills instruction (71.5%, n = 148), group counseling (44.0%, n = 91), universal health screenings (17.9%, n = 37), and other interventions (4.3%, n = 9) such as food programs, holiday donation programs, peer support, and academic support meetings. We used the Freeman-Halton exact test to examine the relationship between grade level (n = 183) and these supports and found that small group counseling (p < .001, ϕ = .405) and coping skills instruction (p = .028, ϕ = .200) were significant, both with moderate positive association. For small group counseling, 63.0% (n = 51) of elementary school counselors and 45.2% (n = 19) of middle school counselors provided this support as compared to 16.7% (n = 10) of high school counselors. For coping skills instruction, 77.8% (n = 63) of elementary school counselors and 71.4% (n = 30) of middle school counselors reported this intervention as compared to 56.7% (n = 34) of high school counselors.

Research Question 3

RQ3 examined the barriers school counselors encountered in their ability to provide services and if this differed by grade level, SES, location, number of non-counseling duties, caseload size, and following the state guideline to spend 80% of time providing student services. When asked if they had encountered barriers to assisting their students with their COVID-19–related needs, 54.6% (n = 113) of school counselors reported that they had experienced barriers, and 45.4% (n = 94) reported that they had not. For those counselors who answered “yes,” barriers included: high caseload (44.4%, n = 92), number of non-counseling duties (20.3%, n = 42), lack of administrator support (12.1%, n = 25), being included on master schedule for guidance classes (10.1%, n = 21), lack of training to address COVID-19 needs (8.2%, n = 17), too much time coordinating the MTSS program (7.7%, n = 16), and other reasons (9.7%, n = 20). Examples of other reasons include students’ attendance, lack of resources (both space and personnel), and focus on academics over mental health. Of note, 47.3% (n = 98) of school counselors reported an increase in non-counseling duties since COVID-19, ranging from a substantial to a slight increase.

We used the Freeman-Halton exact test to examine the aforementioned barriers by grade level (n = 183) and found that being on the master schedule (p < .001, ϕ = .297) was significant with moderate positive association with 19.8% (n = 16) of elementary school counselors reporting this task as compared to 2.4 % (n = 1) of middle school counselors and 1.7% (n = 1) of high school counselors. We used point-biserial correlation analysis to examine how the number of new post–COVID-19 non-counseling duties related to the perceived barriers to providing services to students and found this to be significant (rpb = .211, p = .002) with a positive moderate association. School counselors who reported barriers to providing services had been allocated more non-counseling duties since the pandemic (n = 113, M = 1.22, SD = 1.49) than those who did not report barriers (n = 94, M = .66, SD = 1.04). We used a Freeman-Halton exact test to examine the specific barriers by caseload (n = 204) and found school counselors with a high caseload reported significantly more difficulty in addressing students’ COVID-19–related needs (p < .001, ϕ = .284), with a moderate positive association for large (58.1%, n =18) and medium (47.2%, n = 68) caseloads, as compared to those with a small (10.4%, n = 3) caseload. Investigating the state DOE guideline for 80% of time in service to students (n = 177), excluding those who were unsure, revealed that 63.3% (n = 112) followed the guideline and 36.7% did not (n = 65). We used a Fisher’s exact test to examine the relationship between following the 80% guideline and specific barriers and found that reporting too many non-counseling duties (p < .001, ϕ = -.358) was significant, with a moderate negative association for those who did not follow the guideline (41.5%, n = 27) in comparison to those who did follow the 80% guideline (10.7%, n = 12). All other barriers were not significant with grade level, SES, location, number of non-counseling duties, caseload size, and following the 80% state guideline. We used a Fisher’s exact test to examine SES by Title I (n = 178) classification and found that it was not significant with any of the barriers.

Discussion

Our results render a disturbing picture of students’ post–COVID-19 mental health functioning and school counselors’ perceived ability to effectively meet their students’ needs since a return to in-person learning, as reported by this sample of 207 school counselors in Tennessee. For RQ1, over 93% of our respondents indicated that their students’ mental health had worsened, with anxiety and depression identified as the most pronounced psychological concern, followed by family dysfunction, grief, technology addiction, and suicidality. These results confirm our predictions that the COVID-19 pandemic would exert a harmful impact on the mental health of children and adolescents (Bryant et al., 2020; Cénat & Dalexis, 2020). Depression and suicidality were significant concerns for middle and high school counselors, and substance abuse was significant at the high school level. The reported spike in diagnosable mental health problems by secondary school counselors aligns with research indicating that half of all mental health and substance use disorders begin at 14 (Quinn et al., 2016). The CDC recently reported that depression, substance abuse, and suicide have increased among adult populations since COVID-19, with young adults presenting the most significant risk (Czeisler et al., 2020). Our results provide preliminary evidence indicating that COVID-19–related trends have similarly impacted adolescents. Further, given the relationship between ACEs and substance misuse (CDC, 2022; Quinn et al., 2016), it may be reasonable to conjecture that an increase in family dysfunction, grief, fear of COVID-19, and severance of social relationships underscored a rise in substance use problems, particularly among high school students.

In addition to mental health, student academics notably declined according to school counselors in Tennessee, with 90.3% of participants reporting negative changes to students’ academics. Previous research attributed students’ COVID-19 pandemic–related academic issues to the vagaries of online instruction, a lack of parental supervision, inadequate technology, and limited workspace, among other factors (Ellis et al., 2020; Karaman et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021). Our results aligned with these findings by explicitly connecting delays in students’ academic progress to psychological factors. Of note, we found a significant relationship between grade level, lack of motivation, poor mental health, and attention issues, with middle and high school counselors reporting greater concerns in the areas of motivation and mental health, and elementary and middle school counselors identifying attention problems as the greatest concern. The developmental onset of mental health disorders (Lambie et al., 2019) likely accounts for increased student mental health problems reported by middle and high school counselors. However, motivation and attentional issues across the grades were problematic, and because both are symptomatic of depression and anxiety, they raise a red flag for the mental health of all K–12 students in Tennessee.

Alongside academics, 87.0% of school counselors reported negative changes in students’ social skills and 87.4% reported worsened behaviors among students, with trouble socializing with peers, absence of social flexibility, and an increase in physical and relational aggression being the most pronounced problems. Declines in students’ ability to get along with peers may be uniquely linked to social isolation during lockdown (Ellis et al., 2020; Karaman et al., 2021); however, of great concern is the increase in all forms of bullying, with cyberbullying being particularly problematic in middle school. Youth aggression is a long-term consequence of ACEs and has implications for overall school safety, with victimization and perpetration both positively associated with school violence (Forster et al., 2020).

RQ2 investigated what interventions school counselors used to assist students with their COVID-19–related concerns and examined interventions by grade level. The preponderance of school counselors relied on individual counseling (95.7%), consultation (85.5%), referrals (80.7%), collaboration with other school-based helpers (77.3%), and coping skills instruction (71.5%), all of which are consistent with crisis-level supports. Nonetheless, only 44% of the sample, primarily elementary school counselors, had used small group counseling, despite its proven efficacy with children exposed to trauma (Salloum & Overstreet, 2008). The underutilization of group work at the high school level presents a concern, given that group work provides context for peer support and social learning, both considered critical therapeutic factors for adolescents (Gysbers & Henderson, 2012). Nonetheless, this finding resonates with previous results that high school counselors are more apt to assume administrative roles in place of the provision of direct student services (Chandler et al., 2018). Universal assessment has been proffered as an efficient and empirically grounded method for the early identification of at-risk students in need of COVID-19–related interventions (A. Erickson & Abel, 2013; Karaman et al., 2021; Pincus et al., 2020). Unfortunately, only 17.9% of the sample reported administering universal mental health screeners, a finding aligned with other studies that indicate schools have resisted adopting mental health screeners because of inadequate resources and related concerns about following up with students identified as being at risk (Burns & Rapee, 2022).

For RQ3, we explored the school counselors’ perspectives of the barriers they have encountered in assisting their students with their COVID-19 concerns. The proliferation of barriers reported by school counselors (high caseload, non-counseling duties, lack of administrator support, being on the master schedule for guidance classes, and a lack of training) verifies our concern that school counselors in Tennessee did not receive the support instrumental to their ability to provide effective student services at this critical time. Our state-level findings resonate with studies conducted in other states that indicate school counselors’ non-counseling duties increased during the pandemic while administrator support declined (Savitz-Romer et al., 2021). Other studies have also drawn attention to widespread staffing shortages associated with COVID-related absences and a reduced pool of substitute teachers (Patterson, 2022). Although we did not examine staff resources explicitly, with almost 50% of our Tennessee sample witnessing an increase in their non-counseling duties, it would be reasonable to infer that campus administrators are deploying school counselors to triage critical gaps in staffing patterns. Interestingly, despite a widespread increase in non-counseling duties post–COVID-19, only 20.3% of counselors reported non-counseling duties as a barrier to providing care. The discrepancy between these two results may be indicative of the phenomenon of role diffusion in school counseling, a problem that emerges when school counselors begin to integrate non-counseling duties as part of their accepted role and thus do not perceive them as antithetical to their professional identity (Astramovich et al., 2013). Furthermore, neither SES (Title I) nor location (rural, suburban, urban) were significant with barriers, and although this could reflect our relatively small sample, it could also be indicative of staff shortages adversely affecting the role of school counselors across all settings, regardless of the school’s demographic status.

The most notable barrier reported by respondents was a large caseload. School counselors with large and medium-sized caseloads reported more barriers and were less likely to follow the 80% guideline. Thus, those students who were negatively impacted by large counselor caseloads before COVID-19 faced further obstacles in accessing their school counseling services despite an overall increase in their mental health and academic needs. Further, elementary school counselors listed on the master schedule for guidance classes faced additional barriers to addressing their students’ needs outside of their prevention-focused (Tier 1) activities. Classroom guidance is considered helpful in elementary school for building social skills and study habits; however, when counselors are placed on the master schedule, it can impact their ability to provide responsive student services (Gysbers & Henderson, 2012) which seemed to be the case with our respondents.

Implications for Professional Advocacy

The results of this study illustrate a decline in student functioning, pronounced in the area of mental health, and have implications for school counselor advocacy in the areas of policy and practice. Advocating for policy change takes time and is beyond the individual efforts of school counselors, who are often beholden to their principal’s limited understanding of school counselors’ appropriate role and function (Lancaster & Reiner, 2022) and subsumed by untenable caseloads in under-resourced schools (Lambie et al., 2019). We, therefore, assert that advocacy is the professional imperative for all vested school counseling professionals (state counseling associations, school counselor educators, school counseling supervisors, and school counselors), all of whom could be working in tandem to advance the profession.

At the policy level, state and national counseling associations should reconsider the important role school counselors play in supporting students’ mental well-being and re-examine policies that delineate the appropriate use of school counselors’ time. Currently, the state school counseling model (Tennessee Policy 5.103) mirrors the national model (ASCA, 2019), perennially focusing on school counselors’ role in supporting student academics and delimiting their counseling role to prevention services, crisis counseling, and referrals to other mental health professionals. For state and national counseling associations, positioning school counselors as primarily focused on student academics demonstrated their value during the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB; 2001) era, which prioritized unidimensional outcome measures of student success, particularly in math and reading (Savitz-Romer, 2019). However, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) replaced NCLB in 2015 and emphasizes more holistic aspects of student development and school climate. Many scholars argue that the ESSA (2015) combined with the rise in mental health issues has created a policy window for school counselors, led by their state and national professional associations (Savitz-Romer, 2019), to focus on the non-cognitive aspects that undergird healthy student development and to reclaim mental health as a domain central to school counselor practice (Lambie et al., 2019).

Redefining school counselors’ role in terms of mental health would require them to receive more clinical supervision (Lambie et al., 2019). In comparison to counselors in clinical settings, school counselors receive little to no supervision for their clinical efforts, which affects their clinical identity and weakens their counseling skills over time (Lancaster & Reiner, 2022). To address this gap, symbiotic partnerships could be formed with counselor education programs, particularly those that offer doctoral degrees in counselor education and supervision, to provide clinical supervision to local school counselors. Progress in this area may be forthcoming in the state, as institutions of higher education that operate school counseling, school psychology, and school social work programs have been invited to apply for grants funded through COVID-19 relief funding to support student internships in high-need schools. In addition, funds are available to support clinical supervision experiences that extend beyond students’ graduate training programs (Tennessee DOE, 2023).

MTSS programs also offer a promising prevention and intervention framework for meeting students’ comprehensive needs, including mental health, and align to both state and national school counseling models (Goodman-Scott et al., 2019). Further, the Tennessee DOE (2018) has developed a resource guide based on a tiered model for supporting students’ differential mental health needs, which school counselors could efficiently implement within their existing MTSS programs. Of note, within the Tennessee model, Tier 1 mental health practices build a foundation for mental wellness for all students. Advanced supports at Tiers 2 and 3 provide students who are at risk because of behavioral and/or mental health concerns with access to small groups and mental health interventions. One dimension of the state’s tiered mental health model is universal screening to identify students with internalizing behavioral disorders. Although few counselors in this study utilized universal screening, we recommend school counselors and their supervisors leverage the preexisting Tennessee DOE guidelines to petition their districts to adopt universal mental health screening.

Although the state mandated reduced counselor ratios in 2017 (Policy 5.103.), the funding formula allowed for uneven adoption of this policy (Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury, n.d.), and target ratios fell short of national recommendations (ASCA, 2019). Thus, a function of this research was to utilize results in policy contexts to advocate for ratio realignments. In partnership with the state school counselor association, we produced a one-page results summary, written in simple language, to disseminate to state politicians to illuminate the acuity of mental health issues faced by K–12 students and proposed a solution through increased school counselor access. An advocacy effort led by the state association resulted in proposed legislation TN HB0364/SB0348, which would require one licensed full-time professional school counselor position for every 250 students and is currently advancing through the state Senate and House committees. A significant takeaway from this study is the importance and potency of coordinated partnerships between researchers, state counseling associations, and school counselors—an alliance that could be replicated in other states by school counselor stakeholders to advocate for the profession.

Limitations

The generalizability of these findings is limited because of the use of a state-level sample and a non-standardized, self-report survey. First, self-report surveys are sensitive to respondents’ tendency to rate themselves more favorably. Thus, it would be reasonable to conjecture that school counselors overestimated their adherence to the state guideline to spend 80% of their time in service to students and underreported their non-counseling duties. Second, although the items were informed by previous research on the psychological issues faced by children and adolescents during COVID-19 (Ellis et al., 2020; Karaman et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021) and those factors that affect school counselors’ ability to provide direct services (Kaffenberger & O’Rorke-Trigiani, 2013; Parzych et al., 2019; Whitney & Peterson, 2019), the use of an ad hoc survey precluded us from performing more robust analyses (e.g., regression analysis). Third, because we only gathered data on students’ mental health issues and academic functioning post–COVID-19 pandemic, we have no benchmark data of students’ pre–COVID-19 functioning with which to make objective comparisons.

Fourth, although the sample was large enough to find some significant results, it was a small percentage of the state’s total population of public school counselors, which is estimated to be over 2,000. A larger sample would have increased the generalizability of findings and impacted the significance levels and practical importance of the results. Fifth, our sample lacks racial and gender diversity; however, it does align with the state’s overall population of educators (Tennessee DOE, 2021). Finally, regarding data analysis, interpreting correlations on a small population sample needs to be performed cautiously because of the possibility of sampling error. Additionally, point-biserial correlation can be impacted by the dichotomous nature of one of the variables, which constrains the variability of the results (Hinkle et al., 2002). Nonetheless, correlational analyses of ordinal and nominal variables in small-scale research are consistent with our exploratory design, and the results provide evidence that the variables examined share some type of relationship and provide direction for future research.

Future Research

Given that we conducted this study in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and have utilized data and policy to advocate for expanded student access to school counseling services in Tennessee, this study design could be replicated by future researchers in the event that another pandemic or crisis of similar scale affects K–12 populations. Nonetheless, our exploratory design is an inherent limitation with the preponderance of our findings based on correlational analysis of largely non-parametric data. Future studies could explore dimensions of students’ mental health utilizing student data from empirical inventories. Rather than relying on school counselor perception data, researchers could use results from universal screenings, such as the Behavior Assessment System for Children-3rd edition (BASC-3), to better understand the nature of student issues and examine differential risk by demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity), which could be used to inform evidence-based interventions with at-risk and high-risk populations. Further, researchers could employ quasi-experimental designs to assess outcomes of school counselor-led interventions, such as small groups, with students who have scored as being at risk based on universal screening. Studies of this nature can help build a case for the efficacy of school counselors and, in turn, protect them from role misallocation. Qualitative research could also be conducted in those schools in which school counselors implement a universal screening, intervention, and referral system to glean an implementation blueprint practical to other school counselors within and outside the state.

Conclusion

With elevated rates of depression, anxiety, substance use, and bullying, it is reasonable to conjecture that students in Tennessee have experienced COVID-19–related trauma, which according to research is unlikely to abate without intervention (CDC, 2022; Savitz-Romer et al., 2021). Although our state-level respondents indicated that they provided services consistent with crisis counseling (e.g., individual counseling, group counseling, consultation, and referrals), almost 50% of the counselors had been burdened with additional non-counseling duties, which could reduce their capacity to work with students at different levels of risk. Large caseload was a significant barrier, leaving counselors struggling to provide an appropriate level of care. This finding raises considerable concern about the risk faced by students who have experienced deterioration in their mental health and academics since the onset of COVID-19, yet attend schools in Tennessee with elevated school counselor-to-student caseloads. Nationally and at the state level, school counselors are the most prevalent mental health professionals in schools and are trained in crisis response (National Center for Education Statistics, 2016). Unfortunately, Tennessee school counselors appear to be facing barriers in the provision of student services related to high caseload and non-counseling duties, which presents cause for professional advocacy within the state and beyond.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American School Counselor Association. (2019). ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (4th ed.).

Astramovich, R. L., Hoskins, W. J., Gutierrez, A. P., & Bartlett, K. A. (2013). Identifying role diffusion in school counseling. The Professional Counselor, 3(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.15241/rla.3.3.175

Bryant, D. J., Oo, M., & Damian, A. J. (2020). The rise of adverse childhood experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S193–S194.

https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000711

Burns, J. R., & Rapee, R. M. (2022). Barriers to universal mental health screening in schools: The perspective of school psychologists. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 38(3), 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2021.1941470

Cénat, J. M., & Dalexis, R. D. (2020). The complex trauma spectrum during the COVID-19 pandemic: A threat for children and adolescents’ physical and mental health. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113473.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113473

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, March 31). New CDC data illuminate youth mental health threats during the COVID-19 pandemic [Press release]. https://tinyurl.com/yckv6v9d

Chandler, J. W., Burnham, J. J., Riechel, M. E. K., Dahir, C. A., Stone, C. B., Oliver, D. F., Davis, A. P., & Bledsoe, K. G. (2018). Assessing the counseling and non-counseling roles of school counselors. Journal of School Counseling, 16(7), 1–33. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1182095.pdf

Cholewa, B., Burkhardt, C. K., & Hull, M. F. (2015). Are school counselors impacting underrepresented students’ thinking about postsecondary education? A nationally representative study. Professional School Counseling, 19(1), 144–154. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-19.1.144

Czeisler, M. É., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E. R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. M. W. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report, 69(32), 1049–1057. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6932a1.htm

DeKruyf, L., Auger, R. W., & Trice-Black, S. (2013). The role of school counselors in meeting students’ mental health needs: Examining issues of professional identity. Professional School Counseling, 16(5), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001600502

Dillman, D. A. (2007). Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Ellis, W. E., Dumas, T. M., & Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 52(3), 177–187.

https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000215

Erickson, A., & Abel, N. R. (2013). A high school counselor’s leadership in providing school-wide screenings for depression and enhancing suicide awareness. Professional School Counseling, 16(5), 283–289.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X1201600501

Erickson, K., & Quick, N. (2017). The profiles of students with significant cognitive disabilities and known hearing loss. The Journal of Deaf Studies & Deaf Education, 22(1), 35–48.

https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enw052

Every Student Succeeds Act, Pub. L. No. 114–95 § 114 Stat. 1177 (2015, Dec. 10). https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ95/PLAW-114publ95.pdf

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

Fernandez, T., Godwin, A., Doyle, J., Verdin, D., Boone, H., Kirn, A., Benson, L., & Potvin, G. (2016). More comprehensive and inclusive approaches to demographic data collection. School of Engineering Education Graduate Student Series. Paper 60. https://tinyurl.com/2p9p2ct7

Forster, M., Gower, A. L., McMorris, B. J., & Borowsky, I. W. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences and school-based victimization and perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(3–4), 662–681.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517689885

Frey, B. B. (2018). The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation. SAGE.

Goodman-Scott, E., Betters-Bubon, J., & Donohue, P. (Eds.). (2019). The school counselor’s guide to multi-tiered systems of support. Routledge.

Gysbers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2012). Developing and managing your school guidance and counseling program (5th ed.). American Counseling Association.

Hinkle, D. E., Wiersma, W., & Jurs, S. G. (2002). Applied statistics for the behavioral sciences (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company.

Imran, N., Zeshan, M., & Pervaiz, Z. (2020). Mental health considerations for children & adolescents in COVID-19 pandemic. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(COVID19-S4), S67–S72.

https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2759

Kaffenberger, C. J., & O’Rorke-Trigiani, J. (2013). Addressing student mental health needs by providing direct and indirect services and building alliances in the community. Professional School Counseling, 16(5), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X1201600505

Karaman, M. A., Eşici, H., Tomar, İ. H., & Aliyev, R. (2021). COVID-19: Are school counseling services ready? Students’ psychological symptoms, school counselors’ views, and solutions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647740

Kotrlik, J. W., Williams, H. A., & Jabor, M. K. (2011). Reporting and interpreting effect size in quantitative agricultural education research. Journal of Agricultural Education, 52(1), 132–142.

https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2011.01132

Lambie, G. W., Stickl Haugen, J., Borland, J. R., & Campbell, L. O. (2019). Who took “counseling” out of the role of professional school counselors in the United States? Journal of School-Based Counseling Policy and Evaluation, 1(3), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.25774/7kjb-bt85

Lancaster, C., & Reiner, S. (2022). Supervision in K–12 school settings. In A. S. Lenz & B. Flamez (Eds.), Practical approaches to clinical supervision across settings: Theory, practice, and research (pp. 223–241). Pearson.

Magson, N. R., Freeman, J. Y. A., Rapee, R. M., Richardson, C. E., Oar, E. L., & Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9

National Association for College Admission Counseling. (2019). State-by-state student-to-counselor ratio maps by school district: Data visualizations. https://public.tableau.com/profile/nacac.research#!

National Center for Education Statistics. (2016). National teacher and principal survey. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/ntps

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107–110, 115 Stat. 1425 (2002). https://www.congress.gov/107/plaws/publ110/PLAW-107publ110.htm

Parzych, J. L., Donohue, P., Gaesser, A., & Chiu, M. M. (2019). Measuring the impact of school counselor ratios on student outcomes. ASCA Research Report. https://tinyurl.com/3sbuk5dd

Patel, P., & Clinedinst, M. (2021). State-by-state student-to-counselor ratio maps by school district. National Association for College Admission Counseling. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED615227.pdf

Patterson, J. (2022, March 4). School counselors and social workers struggle to meet student needs. National Education Association Today. https://tinyurl.com/yckwhhc4

Pincus, R., Hannor-Walker, T., Wright, L., & Justice, J. (2020). COVID-19’s effect on students: How school counselors rise to the rescue. NASSP Bulletin, 104(4), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636520975866

Quinn, K., Boone, L., Scheidell, J. D., Mateu-Gelabert, P., McGorray, S. P., Beharie, N., Cottler, L. B., & Khan, M. R. (2016). The relationships of childhood trauma and adulthood prescription pain reliever misuse and injection drug use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 169, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.09.021

Rea, L. M., & Parker, R. A. (1992). Designing and conducting survey research: A comprehensive guide. Jossey-Bass.

Salloum, A., & Overstreet, S. (2008). Evaluation of individual and group grief and trauma interventions for children post disaster. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(3), 495–507.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802148194

Savitz-Romer, M. (2019). Fulfilling the promise: Reimagining school counseling to advance student success. Harvard Education Press.

Savitz-Romer, M., Rowan-Kenyon, H. T., Nicola, T. P., Alexander, E., & Carroll, S. (2021). When the kids are not alright: School counseling in the time of COVID-19. AERA Open, 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211033600

Sheperis, C., Drummond, R. J., & Jones, K. D. (2020). Assessment procedures for counselors and helping professionals (9th ed.). Pearson.

Swedberg, R. (2020). Exploratory research. In C. Elman, J. Gerring, & J. Mahoney (Eds.), The production of knowledge: Enhancing progress in social science (pp. 17–37). Cambridge University Press.

Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury. (n.d.). Tennessee basic education program: Handbook for computation. https://tinyurl.com/twazjrut

Tennessee Department of Education. (2018). Tennessee comprehensive school-based mental health resource guide. https://tinyurl.com/2bfetw3t

Tennessee Department of Education. (2020). Reopening schools: Overview guide for LEAs. https://tinyurl.com/2hry8hs6

Tennessee Department of Education. (2021). TDOE, TERA releases 2021 Tennessee Educator Survey results. https://tinyurl.com/523b5hmn

Tennessee Department of Education. (2023). Project RAISE internship opportunities. https://web.cvent.com/event/c34c10c7-31e5-48ec-aaa2-7d343e00af77/websitePage:fa84d4fc-c565-4872-98eb-86552d79a670

Tennessee Office of the Governor. (n.d.). COVID-19 timeline. https://www.tn.gov/governor/covid-19/covid19timeline.html

Tennessee State Board of Education. (2017). School counseling model & standards policy 5.103. https://tinyurl.com/39a7jhyx

Udwin, O., Boyle, S., Yule, W., Bolton, D., & O’Ryan, D. (2000). Risk factors for long-term psychological effects of a disaster experienced in adolescence: Predictors of post traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 41(8), 969–979. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00685

Whitney, D. G., & Peterson, M. D. (2019, February 11). US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(4), 389–391.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Skinner, E. A. (2011). Review: The development of coping across childhood and adolescence: An integrative review and critique of research. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025410384923

Chloe Lancaster, PhD, is an associate professor at the University of South Florida. Michelle W. Brasfield, EdD, LPSC, is an assistant professor at the University of Memphis. Correspondence may be addressed to Chloe Lancaster, 422 E. Fowler Ave, EDU 105, Tampa, FL 33620, clancaster2@usf.edu.

Nov 9, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 3

Derron Hilts, Yanhong Liu, Melissa Luke

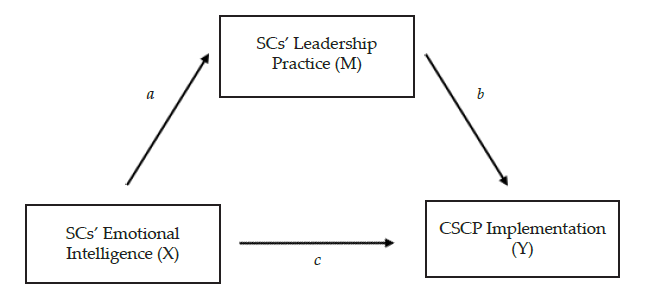

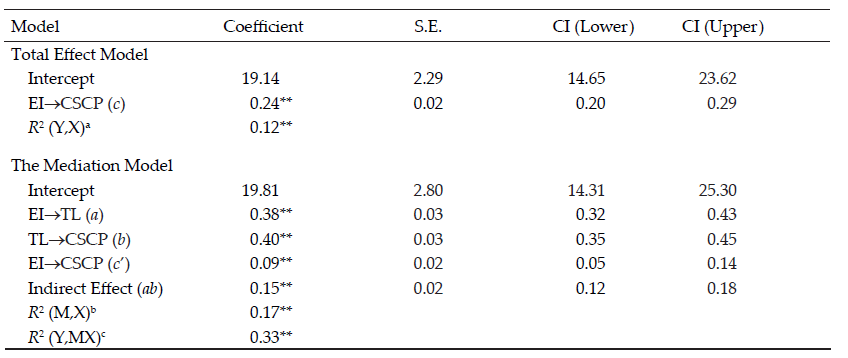

The authors examined whether school counselors’ emotional intelligence predicted their comprehensive school counseling program (CSCP) implementation and whether engagement in transformational leadership practices mediated the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation. The sample for the study consisted of 792 school counselors nationwide. The findings demonstrated the significant mediating role of transformational leadership on the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation. Implications for the counseling profession are discussed.

Keywords: emotional intelligence, school counselors, transformational leadership, comprehensive school counseling program, implementation

School counselors have been called upon to design and implement culturally responsive comprehensive school counseling programs (CSCPs) that have a deliberate and systemic focus on facilitating optimal student outcomes and development (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2017, 2019b). To this end, school counselors are expected to align their activities with the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2019b) with an aim toward facilitating students’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviors to be academically and socially/emotionally successful and preparing students for college and career (ASCA, 2021). Relatedly, ASCA (2019a) urges school counselors to apply and enact a model of leadership in the process of program implementation. Several studies (e.g., Mason, 2010; Mullen et al., 2019; Shillingford & Lambie, 2010) have provided empirical evidence that supports the predictive role of school counselors’ leadership on their program implementation outcomes. Still, little is known about the relationship between school counselors’ program implementation and their leadership practices grounded in a specific model such as transformational leadership (Bolman & Deal, 1997; Kouzes & Posner, 1995). Understanding this relationship may allow school counselors to better align their practices within a specific leadership framework consistent with best practice (ASCA, 2019a).

Although leadership has been broadly established as a macro-level capability, emotional intelligence has started to gain interest in recent literature, as intra- and interpersonal competencies are central to school counselors’ practice (Hilts et al., 2019; Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Mullen et al., 2018). For instance, school counselors must be emotionally attuned to themselves and others to more effectively navigate the complexities of systems in which they operate (Mullen et al., 2018). One way to achieve such emotional attunement may be by respecting and validating others’ perspectives and providing emotional support to enact interpersonal influence aimed at facilitating educational partners’ keenness toward programmatic efforts (Hilts et al., 2019; Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Jordan & Lawrence, 2009). The purpose of the current study is to examine the mechanisms between school counselors’ emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, and CSCP implementation.

Comprehensive School Counseling Programs

Although school counseling programs will vary in structure based on the unique needs of school and community partners (Mason, 2010), programs should be comprehensive in scope, preventative by design, and developmental in nature (ASCA, 2017). CSCP implementation, which comprises a core component of school counseling practice, involves multilevel services (e.g., instruction, consultation, collaboration) and assessments (e.g., program assessments, annual results reports). The functioning of these services and assessments is further defined and managed within the broader school community by the CSCP (Duquette, 2021). Moreover, CSCPs are generally aligned with the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2019b) to create a shared vision among school counselors to have a more deliberate and systemic focus on facilitating optimal student outcomes and development.

Over the past 20 years, researchers have consistently found positive relationships between CSCP implementation and student achievement reflected through course grades and graduation/retention rates (Sink et al., 2008) and achievement-related outcomes such as behavioral issues and attendance (Akos et al., 2019). Students who attend schools with more well established and fully implemented CSCPs are more likely to perform well academically and behaviorally (Akos et al., 2019). Additionally, researchers have found that school counselors who engage in multilevel services associated with a CSCP are more likely to have higher levels of wellness functioning compared to those who are less engaged in delivering these services (Randick et al., 2018). As such, CSCP implementation seems to not only be positively related to student development and achievement but also the overall well-being of school counselors.

Designing and implementing a culturally responsive CSCP demands a collaborative effort between both school counselors and educational partners to create and sustain an environment that is responsive to students’ diverse needs (ASCA, 2017). This ongoing and iterative process requires school counselors to be emotionally attuned with school, family, and community partners to co-construct, facilitate, and lead initiatives to more efficaciously implement equitable services within their programs (ASCA, 2019b; Bryan et al., 2017). School counselors must engage in leadership and be attentive toward their self- and other-awareness and management to traverse diverse contexts involving differences in personalities, values and goals, and ideologies (Mullen et al., 2018). Although researchers have reported that school counselors’ CSCP implementation is positively related to their leadership (e.g., Mason, 2010), no studies have investigated the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence generally refers to the ability to recognize, comprehend, and manage the emotions of oneself and others to accomplish individual and shared goals (Kim & Kim, 2017). Scholars have purported that emotional intelligence can be subsumed into two overarching forms: trait emotional intelligence and ability emotional intelligence (Petrides & Furnham, 2000a, 2000b, 2001). Trait emotional intelligence, also known as trait emotional self-efficacy, involves “a constellation of behavioral dispositions and self-perceptions concerning one’s ability to recognize, process, and utilize emotional-laden information” (Petrides et al., 2004, p. 278). Ability emotional intelligence, also referred to as cognitive-emotional ability, concerns an individual’s emotion-related cognitive abilities (Petrides & Furnham, 2000b). Said differently, trait emotional intelligence is in the realm of an individual’s personality (e.g., social awareness), whereas ability emotional intelligence denotes an individual’s actual capabilities to perceive, understand, and respond to emotionally charged situations.

Over the past two decades, scholars have expanded the scope of emotional intelligence to have a deliberate focus on how emotional intelligence occurs within teams or groups in the workforce context (Jordan et al., 2002; Jordan & Lawrence, 2009). Given the salience of emotions in various professional and work contexts (e.g., Jordan & Troth, 2004), Jordan and colleagues’ (2002) Workgroup Emotional Intelligence Profile (WEIP) facilitates a better understanding of how emotional intelligence manifests in teams. The WEIP centralizes emotional intelligence around the “understanding of emotional processes” (Jordan et al., 2002, p. 197). Using the WEIP, researchers revealed that higher emotional intelligence scores are positively related to job satisfaction, organizational citizenship (e.g., performing competently under pressure), organizational commitment, and school and work performance (Miao et al., 2017a, 2017b; Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, 2004). Conversely, higher scores of emotional intelligence were negatively associated with turnover intentions and counterproductive behavior (Miao et al., 2017a, 2017b).

Emotional intelligence has also gained increased attention in the counseling literature. For example, Easton et al. (2008) found emotional intelligence as a significant predictor of counseling self-efficacy in the areas of attending to the counseling process and dealing with difficult client behavior. Following a two-phase investigation, Easton and colleagues demonstrated the stability of emotional intelligence during a 9-month timeframe in both groups of professional counselors and counselors-in-training; thus, the researchers argued that emotional intelligence may be an inherent characteristic associated with the career choice of counseling. In an earlier study with a sample with 108 school counselors, emotional intelligence was found to be significantly and uniquely related to school counselors’ multicultural counseling competence (Constantine & Gainor, 2001). More recently, school counselors’ emotional intelligence was found to be positively related to leadership self-efficacy and experience (Mullen et al., 2018).

School Counseling Leadership Practice

Leadership practice is a dynamic, interpersonal phenomenon within which school counselors engage in behaviors that mobilize support from educational partners to achieve programmatic and organizational objectives aimed at promoting student achievement and development (Hilts, Peters, et al., 2022). The focus on leadership practice entails an emphasis on the actual behavior of the individual, which scholars have contended is a byproduct of both individual and contextual factors in which these behaviors occur (Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Mischel & Shoda, 1998; Scarborough & Luke, 2008). For instance, school counselors’ support from other school partners (Dollarhide et al., 2008; Robinson et al., 2019) and previous leadership experience (Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Lowe et al., 2017) have been found to influence school counselors’ engagement in leadership. Hilts, Liu, and colleagues (2022) found that intra- and interpersonal factors significantly predicted school counselors’ engagement in leadership such as multicultural competence, leadership self-efficacy, and psychological empowerment. Across several models of leadership (e.g., Bolman & Deal, 1997; Kouzes & Posner, 1995), transformational leadership has been situated in the context of school counseling (Gibson et al., 2018).

Transformational School Counseling Leadership