Melissa J. Sitton, Tina Du Rocher Schudlich, Christina Byrne

A psychosocial approach to predicting self-injurious behavior (SIB) may allow for more accurate predictions and enhance intervention for individuals who engage in SIB. We examined psychosocial predictors of SIB within and between two populations: individuals with traits of borderline personality disorder (BPD; N = 60) and college students (N = 116). All participants met the inclusion criteria of engaging in SIB at least once in the past year. All participants completed measures of psychological distress, social functioning, and SIB. Methods of SIB did not vary across samples, but SIB rates did. Psychological distress and population type (BPD or student) predicted SIB, whereas social factors did not. Additionally, we found a significant interaction wherein psychological distress was more related to SIB in individuals with traits of BPD. Accordingly, we recommend that counselors consider population and psychological distress when assessing SIB risk in clients.

Keywords: self-injurious behavior, borderline personality disorder, college students, psychological distress, social functioning

Self-injurious behavior (SIB), the deliberate act of self-inflicted bodily harm, is of growing concern to counselors and clinicians. According to Nock (2010), SIB is a broad concept encompassing self-injury completed with suicidal intent (i.e., suicide attempts), without suicidal intent (i.e., nonsuicidal self-injury), or with ambivalence toward life (i.e., ambivalent, meaning neither strictly suicidal nor nonsuicidal). In other words, an individual can engage in SIB with differing goals that vary in intent from harming themselves to dying. The American Psychiatric Association (2013) considers suicide behavior disorder and nonsuicidal self-injury to be “conditions for further study” (p. 801). Individuals who engage in SIB over time are likely to do so with greater frequency, more methods, and increasing lethality (Andrews et al., 2013). Therefore, there is a great need for counselors and clinicians to assess their clients for SIB.

Although there are differing theories of the development and maintenance of SIB based on intent, particularly regarding the development of suicidal and nonsuicidal SIB, there are similar intrapersonal and interpersonal themes across theories. For instance, in their four-function model of nonsuicidal SIB, Nock and Prinstein (2004, 2005) proposed that intrapersonal (e.g., affective) and interpersonal (e.g., help-seeking) factors act as positive and negative reinforcers of nonsuicidal SIB. Similarly, in their renowned interpersonal–psychological theory of suicide, Joiner and colleagues (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010) proposed that individuals who attempt suicide are characterized both by a desire to die (i.e., interpersonal factors of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness) and the acquired capability to attempt (i.e., intrapersonal factors such as past SIB).

Notably, there is no specific theory to date regarding ambivalent SIB. Researchers and clinicians often differentiate SIB into two categories (Nock, 2010). In the first category, there is no explicit intent to die, and therefore it is considered nonsuicidal SIB. In the second category, there is no clear lack of suicidal intent, and therefore it is considered suicidal SIB. Thus, ambivalent SIB is often categorized as suicidal SIB, rather than as a unique experience. Regardless of how ambivalent SIB is classified, it is likely that both intrapersonal and interpersonal factors relate to ambivalent SIB given that both are relevant to suicidal and nonsuicidal SIB. Furthermore, individuals who engage in SIB often report multiple intents behind their past SIB (Andover et al., 2012; Klonsky & Olino, 2008). Because of these similarities and the clinical significance of each, we examined intrapersonal (i.e., psychological distress) and interpersonal (i.e., social functioning) predictors of SIB in the current study.

Predicting SIB With Psychosocial Functioning

The relations between psychological distress and SIB are well established in the literature. Researchers have found positive associations between SIB and depression (Andover et al., 2005; Kirkcaldy et al., 2007), anxiety (Andover et al., 2005; Klonsky & Olino, 2008), obsessive-compulsion (Kirkcaldy et al., 2007), and interpersonal sensitivity (Kim et al., 2015; Kirkcaldy et al., 2007). These studies and others examined specific experiences of psychological distress as it relates to SIB in adults and adolescents and in community and inpatient samples.

Previous studies have also demonstrated relations between social functioning and SIB. For instance, SIB is associated with less social support from family and friends (Rotolone & Martin, 2012; Tuisku et al., 2014). Similarly, SIB is related to more negative interactions or negative relational dynamics with family (Halstead et al., 2014; Van Orden et al., 2010) and friends (Adrian et al., 2011).

Predicting SIB in Different Populations

Some individuals may be at greater risk for developing SIB. In particular, SIB is especially prevalent in individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD). According to the American Psychiatric Association (2013), BPD is characterized by “marked impulsivity” along with “a pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects” (p. 663). Notably, one diagnostic criterion of BPD is “recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, threats, or self-mutilating behavior” (p. 663). Additionally, some risk factors for developing BPD (e.g., high emotion dysregulation, trauma exposure, etc.; Crowell et al., 2009) are also risk factors for engaging in SIB (Nock, 2009, 2010). Although lifetime rates of SIB in individuals with BPD vary, one study found that 92.2% of individuals who sought outpatient treatment for symptoms of BPD had engaged in nonsuicidal SIB within the past 2 months (Andión et al., 2012). Additionally, up to 75% of individuals with BPD reported at least one instance of suicidal SIB (Black et al., 2004). Furthermore, there appear to be differences in SIB engagement when comparing individuals with BPD to a community sample. For example, adults with BPD reported engaging in nonsuicidal SIB more recently and frequently, using more varied methods, and causing more physically severe injuries that require medical attention, compared to individuals without BPD who engaged in nonsuicidal SIB (Turner et al., 2015).

Although the rates and severity of SIB are higher in individuals with BPD than in the general population (Bentley et al., 2015), SIB is considered relatively common in other populations, including nonsuicidal SIB among college students (e.g., Whitlock et al., 2006, 2013). College students are thought to engage in SIB more than the general population (as suggested by Wilcox et al., 2012) with approximately 17%–41% of college students participating in nonsuicidal SIB (Whitlock et al., 2006) compared to 5.9% of adults in the general population (Klonsky, 2011). Most college students are also in the highest risk age group for nonsuicidal SIB (Rodham & Hawton, 2009), and suicide is the second leading cause of death during this period (18–25 years old; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Notably, college students and non–college students of the same age (i.e., 16–24 years old) do not appear to differ in rates of SIB (McManus & Gunnell, 2020).

Current Study

A wealth of research has identified important psychological and social factors that may be associated with the occurrence of SIB. However, it remains unclear how these factors intersect to predict SIB. Additionally, as Turner et al. (2015) suggested, most research on SIB has considered either individuals with BPD or nonclinical samples (e.g., college students) without considering potential differences in predictors between these populations.

The current study used a comprehensive psychosocial approach to examine psychological distress and social functioning in two samples: a high-risk, treatment-seeking sample of individuals with traits of BPD and a sample of college students. This allowed us to characterize how key factors may intersect in predicting SIB. Our objectives were to (a) examine SIB within and between the two populations, (b) evaluate which psychosocial factors predicted total lifetime SIB for both populations, and (c) determine whether the predictors of total lifetime SIB varied by population (i.e., test for an interaction between psychosocial predictors and sample).

Method

Participants and Procedure

This study included a sample of individuals with BPD traits and a college student sample. For both samples, our inclusion criteria required that participants have a history of SIB with at least one self-reported episode of SIB (i.e., SIB of any intent) in the past year. We required recent SIB so that the measures of current psychological and social functioning would be appropriate predictors, rather than examining current functioning with a retrospective report of SIB after several years.

Sample 1: Individuals With Traits of BPD

The first sample consisted of data from a larger study on dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) in teens and adults (Sitton et al., 2020). Participants sought treatment for BPD symptoms from community-based counselors, although not all participants had formal diagnoses of BPD. The counselors obtained informed consent from participants and collaborated with a local university for this larger IRB-approved study. Of the 62 participants in this larger study, 96.8% (n = 60) reported engaging in SIB in the past year and constituted the BPD-Tx sample.

BPD-Tx participants (n = 60) were mostly young adults (M = 23.53 years, SD = 6.85 years, range = 18–48 years old). Based on self-reports, there were 49 females (81.7%), eight males (13.3%), and three participants who identified as non-binary or androgynous (5%). This sample was mostly White/European American (83.1%), followed by multiracial (10.2%), Asian American (1.7%), and Hispanic/Latinx (1.7%), with an additional 3.4% identifying as “other” or not reporting. Most (80%) reported no counseling experience prior to receiving DBT from the community counselors (i.e., at the time of recruitment). Data on sexual orientation was not available for this sample.

Sample 2: Undergraduate College Students

The second sample consisted of undergraduate students in introductory psychology courses at a university in the Pacific Northwest. We recruited students to participate in a study called “Emotional and Behavioral Responses to Stress” and informed all participants that they might experience distress as part of the study. After giving their informed consent, participants completed the measures online in a campus computer lab so any questions or concerns could be immediately addressed by a research assistant trained in suicide prevention. Debriefing included an extensive form that included on- and off-campus mental health resources.

Of the 536 students who completed the survey, 43.8% reported engaging in SIB during their lifetime, and 116 students (21.6%) met the inclusion criteria of engaging in SIB in the past year. This proportion of students is high compared to some student samples (e.g., Whitlock et al., 2006; Wilcox et al., 2012), but it is comparable to the lifetime rate from at least one other university sample (Gratz et al., 2002).

Student participants included in this study (n = 116) were mostly young adults (M = 19.62 years, SD = 1.58 years, range = 18–27 years old). Based on self-reports, there were 89 females (78.4%), 23 males (19.8%), and four participants who identified as non-binary or androgynous (4%). This sample was mostly White/European American (69%), followed by multiracial (19.8%), Asian American (6%), and Hispanic/Latinx (4.3%). Participants’ sexual orientations were as follows: 60.3% heterosexual, 18.1% bisexual, 7.8% pansexual, 6.9% homosexual, 1.7% asexual, and 1.8% who identified as “other.” Most (77.6%) reported previous counseling experiences, with about one-fifth currently seeing a counselor (22.4%). Other studies have found rates of prior experience with counseling services to be closer to 55% in college students (e.g., Niegocki & Ægisdóttir, 2019). Most student participants reported seeking counseling services for stress- and mood-related symptoms, and none reported seeking treatment specifically for BPD.

Measures

Self-Injurious Behavior (SIB)

We used the Lifetime Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (LSASI; Linehan & Comtois, 1996) to assess participants’ history of SIB, including frequency, method, and intent. This 20-item measure asks about the dates of the most recent and most severe SIB act (e.g., “When was the most recent time that you intentionally injured yourself?”) and assesses the total lifetime frequency for 11 methods of SIB, as well as the separate intent(s) of each SIB act (suicidal, nonsuicidal, or ambivalent). Higher scores indicate more SIB acts.

Internal consistency was adequate for both samples (BPD-Tx sample, Cronbach’s α = .75; student sample, Cronbach’s α = .73). Notably, the LSASI was created for clinical use rather than research use; therefore, there are no known studies of its reliability or validity. However, the LSASI was already in use by the counselors in the larger study of DBT described, and they chose to use it to assess SIB in the BPD-Tx sample. We used it for the student sample to be consistent with the existing sample data. Following Linehan and Comtois’s (1996) scoring instructions, we calculated a total lifetime frequency for each participant by summing all SIB of any intent.

Psychological Distress

The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 1975) is a broad-spectrum psychiatric symptom checklist. Participants rate their distress level in the past week on a Likert-type scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) for each of 90 items (e.g., “How much were you distressed by feeling critical of others?”). This measure assesses nine factors of psychological distress. For this study, we were interested in the factors of Depression, Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsion, and Interpersonal Sensitivity. The internal consistency of this measure was very high in the BPD-Tx sample (α = .97).

To reduce participant burden, we used the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Spencer, 1982), a 53-item version of the SCL-90-R, for student participants. The internal consistency was very high in the student sample (α = .96).

To assess the comparability of the SCL-90-R and the BSI for subsequent analysis, we separately averaged all items for the factors of Anxiety, Depression, Obsessive-Compulsion, and Interpersonal Sensitivity to determine BPD-Tx participants’ scores of psychological distress using these two measures. We found strong correlations between the SCL-90-R factors and the BSI factors (Depression: r = .92, p < .001; Anxiety: r = .97, p < .001; Obsessive-Compulsion: r = .95, p < .001; Interpersonal Sensitivity: r = .90, p < .001; and Average Psychological Distress: r = .98, p < .001). Following Derogatis (1993), who found no significant difference in validity between the SCL-90-R and the BSI, we used only the BSI items to create symptom factors for both samples. The internal consistency of the BSI items for the

BPD-Tx sample was very high (α = .95).

Social Functioning

The Network of Relationships Inventory-Behavioral Systems Version (NRI; Furman & Buhrmester, 2009) is a 33-item self-report measure of social support and negative interactions in various relationships (i.e., one’s mother, father, friends, and romantic partner). Participants rate the frequency of positive support or negative interactions on a Likert-scale from 1 (little or none) to 5 (the most). The Positive Support scale includes five subscales: Seeks Secure Base, Provides Secure Base, Seeks Safe Haven, Provides Safe Haven, and Companionship. The Negative Interactions scale includes three subscales: Conflict, Antagonism, and Criticism. Higher scores indicate more of each factor. The internal consistency was high for both samples (BPD-Tx, α = .93; student sample, α = .94).

We calculated the mean score of the Positive Support subscales, including Seeks Secure Base, Seeks Safe Haven, and Companionship. We did not include Provides Secure Base or Provides Safe Haven because Furman and Buhrmester (2009) described these as “caretaking” factors rather than “attachment” or “affiliation” factors. We also calculated the mean score of all three Negative Interactions subscales.

Data Analysis Plan

To begin, we tested for the assumptions of analysis, following guidelines proposed by Tabachnick and Fidell (2019). We defined outliers as data points beyond three standard deviations from the mean. We evaluated outliers within each group and replaced them with the value that was three standard deviations above the group mean. We chose this more liberal approach to outliers to maximize variability in the data. It was especially important to maintain variability in the outcome variable of total SIB given that higher levels of SIB have great clinical significance. For skewness and kurtosis of the composite variables, we used ±2 as our acceptable range of values. We transformed variables that did not meet our criteria for normality. We also utilized the missing completely at random test and found no systematic patterns to missing data, and thus used the group means to replace missing values for analysis.

To assess SIB in the two samples, we examined the intent of SIB acts separately for each sample and analyzed if SIB rates differed based on demographic information. To examine psychosocial predictors of SIB, we conducted a multiple linear regression. We used total SIB (including suicidal, nonsuicidal, and ambivalent SIB) as the outcome variable. We also examined differences in predictors of total SIB between the BPD-Tx and student samples by including interaction terms (e.g., psychological distress x sample). Statistically significant interactions were graphed to aid interpretation (Howell, 2013).

For the multiple linear regression analysis, we used effect coding for sample type (Daly et al., 2016), which allows comparison of a sample mean to the overall mean instead of using one sample as a reference group. Additionally, we centered the predictor variables around the grand mean for the whole sample to reduce the risk of multicollinearity. We inspected the tolerance and variance inflation factors, and used multiple sources (e.g., correlations between variables, p-values, and the standard error of the regression coefficients) to determine if multicollinearity was an issue.

Results

We used SPSS 24.0 to analyze the data. Using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), we found no differences between the samples based on gender or ethnicity (all p values > .05). However, using an independent samples t-test, we found that the BPD-Tx sample (M = 23.53, SD = 6.85) was older on average than the student sample: M = 19.62, SD = 1.58, t(173) = 5.85, p < .001. Additionally, the BPD-Tx sample (13.3%) reported prior experience with counseling (dichotomous variable) less often than the student sample (77.6%) on average: χ2(1) = 59.39, p < .001.

Sample Differences in SIB

We conducted descriptive analyses for all SIB variables. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics of the different intents of SIB (nonsuicidal, ambivalent, and suicidal), total SIB (including the untransformed total score), and the reported number of SIB methods. Table 1 also includes difference scores of SIB acts based on independent sample t-tests in consideration of the two samples. Individuals in the BPD-Tx sample engaged in more nonsuicidal, ambivalent, and total SIB in their lifetime compared to the student sample. Although there appeared to be no difference between samples in suicidal SIB, it is worth noting that this variable did not meet our criteria for normality in either sample even after transformation.

Table 1

Means (With Standard Deviations) and Difference Scores for Self-Injurious Behavior (SIB) by Sample

| Variable | BPD-Tx

(N = 60) |

Student

(N = 116) |

t(df) | p |

| Nonsuicidal SIB | 3.13 (1.81) | 2.34 (1.55) | t(174) = 3.01 | .003 |

| Ambivalent SIB | 1.92 (2.02) | 1.07 (1.33) | t(86.25) = 2.94 | .004 |

| Suicidal SIB | 0.66 (0.90) | 0.45 (0.81) | t(174) = 1.61 | .110 |

| Total SIB | 3.87 (1.84) | 2.86 (1.43) | t(96.56) = 3.73 | < .001 |

| Total SIB (untransformed) | 166.31 (268.69) | 44.10 (75.60) | t(63.88) = 3.45 | .001 |

| Number of SIB methods | 3.28 (1.53) | 3.28 (2.11) | t(174) = -0.004 | .997 |

Note. BPD-Tx = participants with traits of borderline personality disorder; Total SIB (untransformed) =

untransformed values after adjusting the outliers in the raw reported values. Significant p values are in bold.

Although the normality of suicidal SIB was improved using a transformation, we were unable to meet our

acceptable range of ±2 for kurtosis (BPD-Tx kurtosis = 4.22; student kurtosis = 2.71).

In the BPD-Tx sample, we found no differences in SIB frequency based on gender, age, ethnicity, or counseling experience using one-way ANOVA. In the student sample, we found no differences in SIB frequency based on age, ethnicity, living situation, or counseling experience using one-way ANOVA. However, SIB frequency differed by gender such that those who identified as non-binary (M = 4.64, SD = 1.35) reported significantly higher rates of SIB than both males (M = 2.80, SD = 1.31) and females (M = 2.95, SD = 1.20). There were no differences in SIB frequency or severity based on sexual orientation in the student sample.

Psychosocial Predictors of SIB

We compared the two samples on the predictor variables first by using independent sample t-tests. We found that BPD-Tx participants reported less psychological distress (M = 2.21, SD = 0.78) than student participants: M = 2.78, SD = 0.89, t(174) = −4.16, p < .001. The BPD-Tx participants (M = 3.25, SD = 0.49) also reported less positive social support than student participants: M = 3.44, SD = 0.54, t(174) = −2.26, p = .025. Lastly, BPD-Tx participants (M = 1.22, SD = 0.43) reported more negative interactions than student participants: M = 1.07, SD = 0.43, t(174) = 2.15, p = .033.

We conducted bivariate correlations between all predictor variables and the outcome variable for each sample. In the BPD-Tx sample, total SIB was positively correlated with average psychological distress (r = .37, p = .004). In the student sample, total SIB was negatively correlated with positive social support (r = −.18, p = .049). In both samples, average psychological distress was positively associated with negative interactions (BPD-Tx: r = .36, p = .005; student: r = .24, p = .008). No other variables were significantly correlated in either sample.

Next, we conducted a multiple linear regression using total SIB as the outcome variable for both samples together. We entered seven predictors simultaneously: psychological distress, positive social support, negative interactions, sample type, and the interactions between sample type and the three other predictors. Together, these seven variables significantly predicted total SIB: F(7,168) = 5.01, p < .001, MSE = 2.33, r2 = .17. As shown in Table 2, psychological distress (sr2 = .06), sample type (sr2 = .12), and the interaction between psychological distress and sample type (sr2 = .03) were each significant unique predictors of total SIB. Specifically, based on the positive β weights, more psychological distress and being in the BPD-Tx sample were both associated with higher lifetime rates of SIB. Notably, multicollinearity did not appear to be an issue in this regression given the moderate to low correlations between factors, sufficiently high tolerance values, acceptable variance inflation factor values (ranging from 1.25–1.55), and the low standard error of regression coefficients relative to their scale.

Table 2

Multiple Regression Analysis Predicting Total Self-Injurious Behavior for the Whole Sample (N = 176)

| CI | |||||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t | p | sr2 | Lower | Upper | |

| Psych. distress | 0.57 | 0.16 | .31 | 3.55 | .001 | .06 | 0.25 | 0.89 | |

| Pos. social support | −0.48 | 0.25 | −.16 | −1.96 | .052 | .02 | −0.97 | 0.00 | |

| Neg. interactions | −0.26 | 0.30 | −.07 | −0.85 | .399 | .003 | −0.85 | 0.34 | |

| Sample type | 0.68 | 0.14 | .39 | 4.87 | < .001 | .12 | 0.40 | 0.95 | |

| Psych. distress x sample | 0.40 | 0.16 | .21 | 2.46 | .015 | .03 | 0.08 | 0.71 | |

| Pos. social support x sample | 0.00 | 0.25 | .00 | 0.00 | .997 | .001 | −0.49 | 0.49 | |

| Neg. interactions x sample | −0.08 | 0.30 | −.02 | −0.25 | .801 | .001 | −0.67 | 0.52 | |

Note. Psych. = psychological; Pos. = positive; Neg. = negative; sr2 = squared semipartial correlation. Sample type was

coded so that BPD-Tx sample = 1, student sample = -1. Significant p values are in bold.

Sample Differences in SIB Predictors

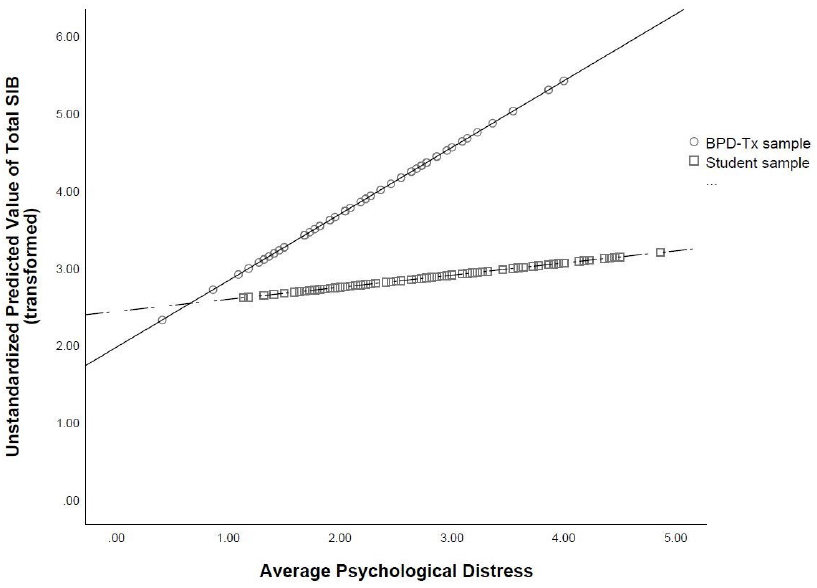

To further probe the statistically significant interaction, we plotted the regression paths for psychological distress predicting total SIB by sample type. As shown in Figure 1, more psychological distress was related to higher lifetime rates of total SIB in both samples, which supports the main effect of psychological distress found in the multiple regression analysis. However, the relation between psychological distress and total SIB was stronger in the BPD-Tx sample than in the student sample (as evidenced by the steeper slope of the regression line representing the BPD-Tx sample compared to that of the student sample).

Figure 1

Regression Lines of Average Psychological Distress Predicting Total Self-Injurious Behavior (SIB) by Sample Type

Discussion

The primary goals of the current study were to establish a more comprehensive set of predictors of SIB and to better understand how the experience of SIB varied by population (BPD-Tx vs. college students). This study was unique in its psychosocial approach to predictors. Additionally, we tested for interactions between sample type and the psychosocial predictors of SIB. This singular examination of interacting predictors has seldom been conducted in the literature, and thus is an important strength of this study.

SIB Engagement and Psychosocial Functioning

The results demonstrate a very high lifetime frequency of SIB in both samples. Although most studies do not report the lifetime frequency rates of SIB of their participants, the frequency of SIB in our student sample was comparable to that found in another study of students using the same SIB methods with nonsuicidal intent (Croyle & Waltz, 2007). The frequency rate of SIB in the BPD-Tx sample appeared to be lower than found in some other studies with individuals with BPD (e.g., Turner et al., 2015).

Additionally, we found that the lifetime frequency rates of SIB were higher in the BPD-Tx sample than in the student sample, which aligns with previous studies (e.g., Klonsky & Olino, 2008; Turner et al., 2015). This makes sense given the maladaptive behaviors often seen in individuals with BPD. Additionally, given that the BPD-Tx sample was older than student participants on average, it is also possible that their increased lifetime rates of SIB reflected a greater number of years to engage in it. Alternatively, the higher SIB frequency reported by the BPD-Tx participants may serve an interpersonal function. According to Linehan (1993), nonsuicidal SIB is commonly used by individuals with BPD to communicate with and gain attention from others.

Interestingly, despite higher rates of total SIB, BPD-Tx participants reported less psychological distress than did student participants. This was contrary to many other studies showing a strong association between psychological distress and engagement in nonsuicidal SIB for individuals with BPD (e.g., Sadeh et al., 2014; Turner et al., 2015). One possible explanation for the lower rates of psychological distress reported by BPD-Tx participants is that their baseline level of psychological distress was higher, leading these negative emotions to be considered normal and therefore not “distressing.” Additionally, given that fewer BPD-Tx participants reported prior experience with counseling than student participants, it could be that BPD-Tx participants reported less psychological distress because of a lack of emotional self-awareness. This aligns with Turner et al.’s (2015) finding that participants with BPD who engage in nonsuicidal SIB reported less awareness of their emotional states. Another explanation is that the BPD-Tx participants were recruited from a community-based clinic wherein they were preparing to start DBT. Although the data used in the current study represents pretest data gathered prior to treatment, it is possible that the BPD-Tx participants were experiencing lowered distress at the time of data collection because of the hope and positive expectations that are often associated with starting a new treatment (Dew & Bickman, 2005).

Socially, the BPD-Tx participants reported less positive support than student participants. This finding aligns with the biosocial theory of BPD (Linehan, 1993), which suggests that individuals with BPD may experience or perceive an invalidating environment. Alternatively, BPD-Tx participants may be more likely to interpret interactions with others as negative, which aligns with Peters et al.’s (2015) finding that individuals with traits of BPD often demonstrated maladaptive responses to emotional experiences, leading them to interact negatively with others.

Psychosocial Predictors of SIB

An important finding of the current study is that psychological distress predicted total SIB with a small to moderate effect size. This suggests that psychological distress (including experiences of anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsion, and interpersonal sensitivity) is an important component of SIB of various intents. Specifically, psychological distress may act as a catalyst for SIB, wherein individuals engage in SIB to decrease their psychological distress. This explanation aligns with Nock and Prinstein’s (2004, 2005) theory of the intrapersonal negative reinforcement function of nonsuicidal SIB. Namely, that one might engage in SIB in order to reduce tension or psychological distress, particularly anxiety.

Contrary to the majority of extant literature (e.g., Wilcox et al., 2012), neither positive social support nor negative interactions predicted total SIB in the current study. We also did not find an interaction between either social variable and sample type, suggesting that social functioning might not be a direct, distinct predictor of total SIB for either population. However, it is possible that social functioning is indirectly related to total SIB. For example, we found a significant positive correlation between negative interactions and psychological distress in both samples. Given these correlations, negative interactions may contribute to experiences of psychological distress, which then predict total SIB. This proposed indirect relation is supported by Adrian et al.’s (2011) study, which found that emotion dysregulation partially mediated the relation between interpersonal problems (i.e., problems with one’s family and peers) and nonsuicidal SIB.

Another possible explanation for the lack of significant social predictors of SIB in the current study is the variability in the data that stems from inconsistent timing of social support. Specifically, it is unclear if positive support preceded SIB engagement, followed the SIB act, or both. Turner et al. (2016) found that perceived social support increased after participants disclosed their nonsuicidal SIB acts to others. However, they also found that this increased support was associated with increased nonsuicidal SIB urges and acts the following day, presumably because the SIB had achieved the desired interpersonal function. Thus, similar to Turner et al.’s (2016) study, the lack of a clear, linear relation between SIB and social support may have contributed to nonsignificant findings of social predictors in the current study.

Notably, the strongest single predictor of total SIB was sample type, with BPD-Tx participants showing greater frequency of total lifetime SIB than student participants. This aligns with Turner et al. (2015), who found that individuals with BPD traits engage in nonsuicidal SIB more often than do those without BPD traits.

Sample Differences in SIB Predictors

The relation between psychological distress and total SIB was stronger for the BPD-Tx sample than for the student sample. This finding is somewhat supported by previous literature; for example, Klonsky and Olino’s (2008) latent class analysis revealed that the group with the most nonsuicidal SIB also reported more symptoms of BPD and psychological distress and reported regularly engaging in nonsuicidal SIB to help regulate their emotions. In comparison, individuals with BPD traits in the current study reported engaging in more total SIB (as well as nonsuicidal SIB) but did not report greater levels of psychological distress than did the student participants. However, if our BPD-Tx participants used SIB for emotion regulation, too, then perhaps this strategy allowed them to experience lower levels of psychological distress day-to-day than student participants. This aligns with Sadeh et al.’s (2014) finding that BPD symptoms related to the affect-regulating function of SIB, especially nonsuicidal SIB.

Additionally, the significant interaction we found between psychological distress and sample type resembles Andover et al.’s (2005) finding that BPD symptoms accounted for the relation between anxiety and nonsuicidal SIB. However, in our study, psychological distress was a significant unique predictor of total SIB (in addition to the significant interaction between psychological distress and sample type). In other words, sample type seems to be a moderator between psychological distress and SIB in our study, as opposed to a mediator.

Counseling Implications

Our findings have several treatment implications. Many counselors will not be surprised by the high rates of SIB found in our BPD-Tx sample. However, we also found a clinically important high rate of SIB in college students. Given that past engagement in SIB is one of the strongest predictors of future SIB (including nonsuicidal and suicidal SIB; Tuisku et al., 2014), the high lifetime rates of SIB found in both samples in the current study are noteworthy for service providers. Specifically, our results suggest that universities and other institutions concerned with mental health in college students should consider utilizing SIB screening tools. Additionally, the high prevalence of students with a lifetime history of any SIB suggests the need for widespread intervention programs for student populations. For example, some research (e.g., Kannan et al., 2021) has examined the implementation of DBT skills groups in college counseling centers for students with a variety of presenting issues, including SIB. Such intervention programs could benefit a wider range of students and help improve quality of life for many, especially those struggling with SIB.

Given that psychological distress predicted total SIB, it may be beneficial for counselors to regularly assess the level of psychological distress in all clients, including those with BPD and college students. Clients with high psychological distress, including anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsion, and interpersonal sensitivity, will likely engage in more SIB than those with low psychological distress, and thus the counselor may be able to intervene before the client escalates to a high frequency of SIB. Assessing and tracking affective distress levels may be common with suicide assessment and safety planning, but there may be less awareness about the need for this with SIB. Treatment protocols could also focus on lowering psychological distress to see if that will decrease SIB. For example, DBT, which emphasizes psychological distress tolerance, has been increasingly implemented in college campus counseling centers (see Chugani, 2015). However, given that the current study’s findings are not causal, we cannot definitively conclude that lowering psychological distress will affect SIB.

Importantly, the interaction between psychological distress and sample type is noteworthy given that it contributes to the small extant evidence of divergence between populations of individuals with symptoms of BPD and other, more community-based populations like college students. Specifically, we found differences in SIB prevalence, in lifetime frequency, and in one predictor (i.e., psychological distress) in our two samples. This aligns with Turner et al.’s (2015) findings that individuals who engaged in SIB with and without BPD differed in SIB frequency, severity, and comorbid affective symptomology.

It is also worth noting that the correlational analysis revealed a difference between these two samples in social functioning. In particular, there was a statistically significant negative correlation between total SIB and positive social support in the student sample, but not in the BPD-Tx sample. Because of this, although we only found one statistically significant interaction between psychosocial predictors and sample type, it is plausible that there are other notable differences in SIB risk factors between these two populations. Thus, when treating SIB, it may be worth assessing for other symptoms of BPD to form a more accurate representation of a client’s experience and to help form a specific treatment plan.

Limitations and Future Studies

One potential limitation of the current study is that we included only individuals who reported engaging in SIB in the past year because we wanted to examine current predictors of current SIB. However, it is possible that psychological distress and social support are more effective predictors of future SIB acts. In other words, the current study examined predictors of the frequency of SIB using current psychosocial functioning, yet the psychosocial variables might have been better at predicting whether or not an individual will engage in SIB in the future. This theory aligns with Heath et al.’s (2009) interpretation of their lack of results linking social support to lifetime rates of nonsuicidal SIB. Specifically, that social support may better relate to differences between those who will engage in SIB compared to those who will not, as opposed to the degree (i.e., frequency) of SIB. It is unclear how the results may have differed if we included a comparison group of individuals who do not engage in SIB or have never engaged in SIB.

A second limitation was the need to use specific measures to compare the student sample to the existing BPD-Tx sample data. Although the LSASI measure has the advantage of thoroughly examining SIB methods and intent, it was intended for clinical use rather than research. Additionally, the LSASI is a lifetime measure of SIB as opposed to assessing recent SIB; although our inclusion criteria required participants to have engaged in SIB at least once in the past year, it is unknown how recent or severe the SIB was in the past year relative to one’s lifetime. Because of this, a dichotomous measure of past-year engagement in SIB may have better suited our need for recent SIB assessment. Nonetheless, the LSASI provided a great depth and variability in the data that was not only valuable in the current research study, but also clinically important to the counselors with whom we collaborated in the larger DBT study.

A third limitation is that there may be other variables involved in predicting SIB that were not assessed, such as emotion regulation skills or trauma exposure. For example, SIB frequency might be more strongly related to one’s ability to regulate distress rather than the presence of distress itself. Given that emotional reactivity and trauma exposure are both risk factors for SIB (Nock, 2009, 2010) and for the development of BPD (Crowell et al., 2009), future studies may want to further explicate these relations.

It is also worth noting that the samples in the current study may include theoretically overlapping populations. Specifically, we did not screen the BPD-Tx group for current academic status, and therefore it is possible that some participants in the BPD-Tx group were also college students. We decided not to exclude BPD-Tx participants based on academic status in order to reduce barriers to study participation and so that the BPD-Tx sample would represent people who seek treatment for BPD in the community, not just those who are not college students. Additionally, although we screened the student sample for the explicit endorsement of BPD diagnosis, it is possible that some participants in the student sample had subthreshold symptoms of BPD (especially considering that SIB itself is a symptom of BPD) or simply had not received a diagnosis of BPD at the time of this study.

Future studies should continue to examine psychosocial predictors of SIB with larger and more diverse samples in order to explore the relations between psychological and social predictors. Additionally, future studies should explore other relevant factors with the psychosocial predictors (e.g., emotion regulation, trauma exposure) to determine if other factors may better explain (or mediate the relations with) SIB. Moreover, longitudinal and experience-sampling designs would allow researchers to gain better understanding of how changes in psychosocial functioning relate to decisions to engage in SIB as well as the exact sequence of events for SIB acts. Although some studies have recently begun using these techniques, a more psychosocial approach to predictors and consequences of SIB (also considering various intents) may provide more prudent information for intervention and treatment of individuals who engage in SIB.

Conclusion

The current study sought to identify psychosocial predictors of SIB in two clinically different populations and to compare predictors between these populations. We found high lifetime frequency rates of SIB in both samples, suggesting a need for more widespread assessment of SIB in young adults from different populations. We also found that population type itself was the strongest predictor of SIB—individuals with traits of BPD engaged in more SIB in their lifetimes than did college students. Additionally, psychological distress predicted SIB; however, we also found a significant interaction between population and psychological distress, which suggests that psychological distress may be more related to SIB in individuals with traits of BPD than in more community-based populations like college students. Consequently, counselors should consider population and psychological distress when assessing SIB risk in clients.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

Data from the existing BPD sample was partially

funded by an internal grant awarded to coauthor

Christina Byrne. The authors reported no conflict

of interest or other funding for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Adrian, M., Zeman, J., Erdley, C., Lisa, L., & Sim, L. (2011). Emotional dysregulation and interpersonal difficulties as risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(3), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9465-3

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Andión, Ó., Ferrer, M., Matali, J., Gancedo, B., Calvo, N., Barral, C., Valero, S., Di Genova, A., Diener, M. J., Torrubia, R., & Casas, M. (2012). Effectiveness of combined individual and group dialectical behavior therapy compared to only individual dialectical behavior therapy: A preliminary study. Psychotherapy, 49(2), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027401

Andover, M. S., Morris, B. W., Wren, A., & Bruzzese, M. E. (2012). The co-occurrence of non-suicidal self-injury and attempted suicide among adolescents: Distinguishing risk factors and psychosocial correlates. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-6-11

Andover, M. S., Pepper, C. M., Ryabchenko, K. A., Orrico, E. G., & Gibb, B. E. (2005). Self-mutilation and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and borderline personality disorder. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35(5), 581–591. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2005.35.5.581

Andrews, T., Martin, G., Hasking, P., & Page, A. (2013). Predictors of continuation and cessation of nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.009

Bentley, K. H., Cassiello-Robbins, C. F., Vittorio, L., Sauer-Zavala, S., & Barlow, D. H. (2015). The association between nonsuicidal self-injury and the emotional disorders: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.006

Black, D. W., Blum, N., Pfohl, B., & Hale, N. (2004). Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: Prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18(3), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.18.3.226.35445

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Leading causes of death reports. https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcause.html

Chugani, C. D. (2015). Dialectical behavior therapy in college counseling centers: Current literature and implications for practice. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 29(2), 120–131.

https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2015.1008368

Crowell, S. E., Beauchaine, T. P., & Linehan, M. M. (2009). A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending Linehan’s theory. Psychological Bulletin, 135(3), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015616

Croyle, K. L., & Waltz, J. (2007). Subclinical self-harm: Range of behaviors, extent, and associated characteristics. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(2), 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.332

Daly, A., Dekker, T., & Hess, S. (2016). Dummy coding vs effects coding for categorical variables: Clarifications and extensions. Journal of Choice Modelling, 21, 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocm.2016.09.005

Derogatis, L. R. (1975). The SCL-90-R. Clinical Psychometric Research.

Derogatis, L. R. (1993). BSI Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring, and Procedure Manual (4th ed.). National Computer Systems.

Derogatis, L. R., & Spencer, P. (1982). The Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring and procedures manual—1. Clinical Psychometric Research.

Dew, S. E., & Bickman, L. (2005). Client expectancies about therapy. Mental Health Services Research, 7(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11020-005-1963-5

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (2009). Methods and measures: The Network of Relationships Inventory: Behavioral Systems Version. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(5), 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025409342634

Gratz, K. L., Conrad, S. D., & Roemer, L. (2002). Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 72(1), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.72.1.128

Halstead, R. O., Pavkov, T. W., Hecker, L. L., & Seliner, M. M. (2014). Family dynamics and self-injury behaviors: A correlation analysis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 40(2), 246–259.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00336.x

Heath, N. L., Ross, S., Toste, J. R., Charlebois, A., & Nedecheva, T. (2009). Retrospective analysis of social factors and nonsuicidal self-injury among young adults. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des sciences du comportement, 41(3), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015732

Howell, D. C. (2013). Statistical methods for psychology (8th ed.). Cengage.

Joiner, T. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press.

Kannan, D., Chugani, C. D., Muhomba, M., & Koon, K. (2021). A qualitative analysis of college counseling center staff experiences of the utility of dialectical behavior therapy programs on campus. Journal of College Student Pychotherapy, 35(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2019.1620662

Kim, K. L., Cushman, G. K., Weissman, A. B., Puzia, M. E., Wegbreit, E., Tone, E. B., Spirito, A., & Dickstein, D. P. (2015). Behavioral and emotional responses to interpersonal stress: A comparison of adolescents engaged in non-suicidal self-injury to adolescent suicide attempters. Psychiatry Research, 228(3), 899–906.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.001

Kirkcaldy, B. D., Brown, J. M., & Siefen, G. R. (2007). Profiling adolescents attempting suicide and self-injurious behavior. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 6(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJDHD.2007.6.1.75

Klonsky, E. D. (2011). Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: Prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychological Medicine, 41(9), 1981–1986. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710002497

Klonsky, E. D., & Olino, T. M. (2008). Identifying clinically distinct subgroups of self-injurers among young adults: A latent class analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.22

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford.

Linehan, M. M., & Comtois, K. A. (1996). Lifetime parasuicide count. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle.

McManus, S., & Gunnell, D. (2020). Trends in mental health, non-suicidal self-harm and suicide attempts in 16–24-year-old students and non-students in England, 2000–2014. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(1), 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01797-5

Niegocki, K. L., & Ægisdóttir, S. (2019). College students’ coping and psychological help-seeking attitudes and intentions. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 41(2), 144–157. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.41.2.04

Nock, M. K. (2009). Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x

Nock, M. K. (2010). Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 339–363.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 885–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2005). Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1), 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.140

Peters, J. R., Smart, L. M., & Baer, R. A. (2015). Dysfunctional responses to emotion mediate the cross-sectional relationship between rejection sensitivity and borderline personality features. Journal of Personality Disorders, 29(2), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2014_28_151

Rodham, K., & Hawton, K. (2009). Epidemiology and phenomenology of nonsuicidal self-injury. In M. K. Nock (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp. 37–62). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11875-003

Rotolone, C., & Martin, G. (2012). Giving up self-injury: A comparison of everyday social and personal resources in past versus current self-injurers. Archives of Suicide Research, 16(2), 147–158.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2012.667333

Sadeh, N., Londahl-Shaller, E. A., Piatigorsky, A., Fordwood, S., Stuart, B. K., McNiel, D. E., Klonsky, E. D., Ozer, E. M., & Yaeger, A. M. (2014). Functions of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents and young adults with borderline personality disorder symptoms. Psychiatry Research, 216(2), 217–222.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.018

Sitton, M., Du Rocher Schudlich, T., Byrne, C., Ochrach, C. M., & Erwin, S. E. A. (2020). Family functioning and self-injury in treatment-seeking adolescents: Implications for counselors. The Professional Counselor, 10(3), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.15241/ms.10.3.351

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson.

Tuisku, V., Kiviruusu, O., Pelkonen, M., Karlsson, L., Strandholm, T., & Marttunen, M. (2014). Depressed adolescents as young adults: Predictors of suicide attempt and non-suicidal self-injury during an 8-year follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152, 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.031

Turner, B. J., Cobb, R. J., Gratz, K. L., & Chapman, A. L. (2016). The role of interpersonal conflict and perceived social support in nonsuicidal self-injury in daily life. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(4), 588–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000141

Turner, B. J., Dixon-Gordon, K. L., Austin, S. B., Rodriguez, M. A., Rosenthal, M. Z., & Chapman, A. L. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury with and without borderline personality disorder: Differences in self-injury and diagnostic comorbidity. Psychiatry Research, 230(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.058

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E., Jr. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697

Whitlock, J., Eckenrode, J., & Silverman, D. (2006). Self-injurious behaviors in a college population. Pediatrics, 117(6), 1939–1948. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2543

Whitlock, J., Muehlenkamp, J., Eckenrode, J., Purington, A., Baral Abrams, G., Barreira, P., & Kress, V. (2013). Nonsuicidal self-injury as a gateway to suicide in young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(4), 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.010

Wilcox, H. C., Arria, A. M., Caldeira, K. M., Vincent, K. B., Pinchevsky, G. M., & O’Grady, K. E. (2012). Longitudinal predictors of past-year non-suicidal self-injury and motives among college students. Psychological Medicine, 42(4), 717–726. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711001814

Melissa J. Sitton, MS, is a doctoral student at Southern Methodist University. Tina Du Rocher Schudlich, PhD, MHP, is a professor at Western Washington University. Christina Byrne, PhD, is an associate professor at Western Washington University. Correspondence may be addressed to Melissa J. Sitton, Department of Psychology, Southern Methodist University, P.O. Box 750442, Dallas, TX 75275-0442, msitton@smu.edu.