May 22, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 1

Jennifer M. Cook, Melissa D. Deroche, Lee Za Ong

The phenomenon of microaggressions is well established within the counseling literature, particularly as it relates to race, ethnicity, gender, and affectual orientation. However, research related to disability or ableist microaggressions is still in its infancy, so counseling professionals have limited information about experiences of disability and ableist microaggressions. The purpose of this qualitative content analysis was to describe participants’ self-reported experiences with ableist microaggressions. Participants (N = 90) had a diagnosed disability and the majority (91.11%) identified as having two or more nondominant identities beyond their disability. We report two categories and 10 themes. While participants were part of the general population, we position our discussion and implications within the context of professional counseling to increase counseling professionals’ awareness and knowledge so counselors can avoid ableist microaggressions and provide affirmative counseling services to persons with disabilities.

Keywords: disability, ableist microaggressions, professional counseling, nondominant identities, affirmative counseling

Day by day, what you choose, what you think, and what you do is who you become.

—Heraclitus, pre-Socratic philosopher

Each person is a complex makeup of dominant and nondominant sociocultural identities. Individuals with dominant cultural identities (e.g., able-bodied, White, middle social class) experience societal privilege, have more sociocultural influence, and have unencumbered access to resources. People with nondominant identities, including people with disabilities (PWD), people of color, and people in lower social class, frequently have less influence and experience structural and interpersonal inequities, limitations, and discrimination (Sue & Spanierman, 2020). As such, people with nondominant identities often experience microaggressions. Microaggressions are unintentional or deliberate verbal, nonverbal, and/or environmental messages that convey disapproval, distaste, and condemnation of an individual based on their nondominant identity (Sue et al., 2007).

Professional counselors are aware and knowledgeable that their identity constellation and their

experiences with microaggressions, as well as those of their clients, impact their worldviews, experiences, and—importantly—the counseling relationship (Ratts et al., 2016). While microaggressions associated with several cultural identities have been well-researched within counseling (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, affectual orientation), others, like ableist microaggressions, have been examined far less frequently (Deroche et al., 2024). The purpose of this article is to describe the microaggression experiences that PWD (N = 90) encounter. Our intention is to increase counseling professionals’ awareness and knowledge about ableist microaggressions so they can examine their beliefs about disability, identify how they may have participated in ableist microaggressions and, ultimately, provide affirmative counseling services to PWD.

Literature Review

Although the term microaggressions was coined by Pierce in the 1970s, it was not until 2007 that it took hold within the allied helping professions (Sue et al., 2007). Initially, the term was used to describe experiences based on race, yet the term has been applied more broadly to the dismissive experiences people with other nondominant identities (e.g., gender, affectual/sexual orientation) encounter (Sue & Spanierman, 2020). In 2010, Keller and Galgay initiated foundational research about the microaggressions that PWD experience. Through their qualitative study, they identified eight microaggression domains experienced by PWD and described their harmful effects on the psychological and emotional well-being of PWD. Those eight domains are: (a) denial of identity, (b) denial of privacy, (c) helplessness, (d) secondary gain, (e) spread effect, (f) patronization, (g) second-class citizenship, and (h) desexualization (i.e., ignoring or avoiding the sexual needs, wants, or desires of PWD). This study marked the beginning of ableist microaggressions research that led scholars not only to naming (e.g., Dávila, 2015) and measuring (e.g., Conover et al., 2017a) specific microaggressions toward PWD, but also describing experiences with ableist microaggressions within specific disability groups (e.g., Coalson et al., 2022; Eisenman et al., 2020) and exploring the impact for specific cultural groups of PWD (e.g., Miller & Smith, 2021).

Before continuing further, it is important for us to explain our use of the term ableist microaggressions, rather than the term disability microaggressions, because it deviates from the typical convention used to name microaggressions (e.g., racial microaggressions, gender microaggressions). While some authors have used the term disability microaggressions (e.g., Dávila, 2015), we believe that this term undercuts and minimizes PWD’s microaggression experiences, as it fails to explicitly communicate that these microaggressions are forms of ableism. Therefore, to validate PWD’s experiences and to align with the disability movement’s philosophy of diversity and social justice, we use the term ableist microaggressions (Perrin, 2019).

The qualitative ableist microaggression studies we reviewed all utilized and endorsed the themes Keller and Galgay (2010) found in their qualitative study, while adding nuance and new information about ableist microaggressions. For instance, Olkin et al.’s (2019) focus group research with women who had both hidden and apparent disabilities (N = 30) supported Keller and Galgay’s eight themes while identifying two others: medical professionals not believing PWD’s symptoms and experiences of having their disability discounted based on appearing young and/or healthy. Similarly, Coalson et al. (2022), who utilized focus groups with adults who stutter (N = 7), endorsed six of Keller and Galgay’s themes and identified participants’ perceptions of microaggressive behaviors (i.e., Exonerated the Listener, Benefit of the Doubt, Focusing on Benefits, and Aggression Viewed as Microaggression) while noting that some participants had minimal or no microaggression experiences.

Although Eisenman et al. (2020) endorsed five of Keller and Galgay’s (2010) themes, they took a different approach to how they analyzed and organized their findings by using Sue et al.’s (2007) microaggression taxonomy. Of note, these researchers were the first to identify and establish microaffirmations within disability microaggressions research. According to Rolón-Dow and Davison (2018) microaffirmations are:

behaviors, verbal remarks or environmental cues experienced by individuals from minoritized racial groups in the course of their everyday lives that affirm their racial identities, acknowledge their racialized realities, resist racism or advance cultural and ideological norms of racial justice. (p. 1)

Like microaggressions, microaffirmations may be intentional or unintentional, but they have a positive rather than a negative impact on people with nondominant racial identities. Eisenman et al. (2020) found all four race-related microaffirmation types identified by Rolón-Dow and Davison (2021)—Microrecognitions, Microvalidations, Microtransformations, and Microprotections—with their sample of people with intellectual disabilities.

Finally, Miller and Smith (2021) conducted individual interviews (N = 25) with undergraduate and graduate students who identified as members of the LGBTQ community with a disability. They, too, found Keller and Galgay’s (2010) domains present in their study and identified eight additional categories. Five categories captured cultural components in addition to disability (i.e., Biphobia, Intersectionality Microaggression, Queer Passing/Disclosure, Racism, and Sexism), while the remaining three were specific to ableist microaggression–focused data: Ableism Avoidance, Faculty Accommodations, and Structural Ableism/Inaccessibility.

The purpose of our study is to add to the burgeoning disability and microaggressions discourse by analyzing participants’ responses to a qualitative prompt offered to them after they completed the Ableist Microaggression Scale (AMS; Conover et al., 2017b). We corroborate prior research findings while adding novel findings that increase professional knowledge about ableist microaggressions and their impact.

Methodology

To ensure compliance with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act, the federal law that requires PWD to have access to electronic information equivalent to that available to nondisabled individuals, we utilized digital accessibility tools on the internet platform used for this study (Qualtrics) and recruited PWD to test the accessibility of the study survey and questions. The data analyzed and reported in this article were part of a larger, IRB-approved study (N = 201) in which we investigated participants’ ableist microaggression experiences quantitatively using the AMS (Conover et al., 2017b) to uncover whether participants’ AMS scores were impacted by visibility of disability, type of disability, and their other nondominant identities (Deroche et al., 2024). After participants completed the survey, they were invited to provide a written response to the open-ended question: “What, if any, information do you think would be helpful for us to know about your personal experiences regarding ableist microaggressions?” Ninety participants (44.77% of the overall sample) responded with rich data that warranted analysis and reporting in an independent article. Because the open-ended question occurred after participants completed the AMS, we agreed that the survey likely influenced their responses, so we chose to conduct a content analysis using an a priori codebook grounded in the AMS subscales (Minimization, Denial of Personhood, Otherization, and Helplessness; Conover et al., 2017b), with additional coding categories for data that did not fit the a priori codes (i.e., Fortitude/Resilience/Coping, Contextual Factors, Impact of Microaggressions/Ableism on Mental Health/Wellness, Microaggression Experiences Are Different Depending on Visibility of Disability, Internalized Ableism, and Microaggressions Include Identities Other Than Disability).

Procedure

Using online data collection via Qualtrics survey, we recruited participants nationally by contacting disability organizations, listservs, social media, and professional contacts who work with organizations that serve PWD. The recruitment included a description of the research; inclusion criteria; and a confidential, anonymized survey link. The survey was Section 508–compliant and optimized to be taken on a computer or mobile device. Data were collected over a 3-month period.

Inclusion Criteria and Participants

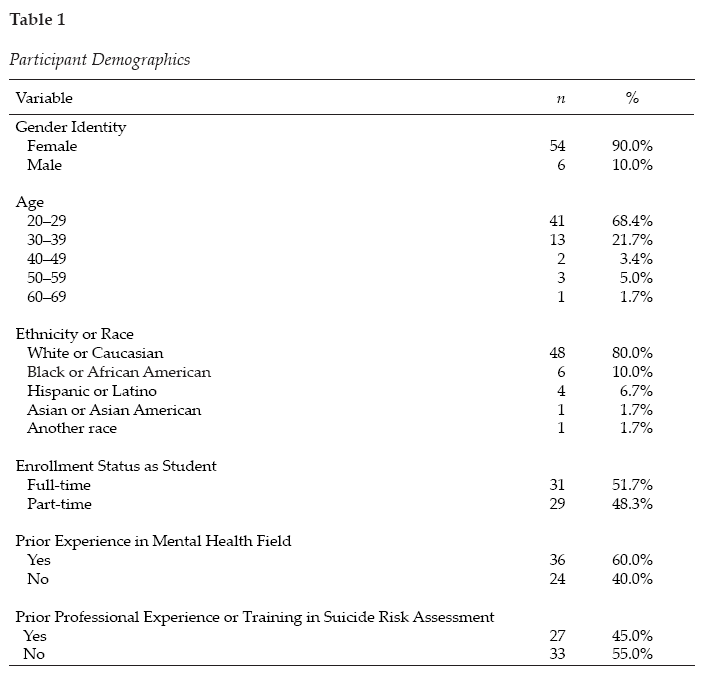

To participate in the study, individuals (a) were at least 18 years of age, (b) had earned a high school diploma or GED, and (c) had a diagnosed disability. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the term disability is defined within the context of a person’s significant limitations to engage in major life activities. Different agencies and organizations such as the World Health Organization and the U.S. Social Security Administration define disability differently (Patel & Brown, 2017). For this study, we categorized disability as (a) physical disability (i.e., mobility-related disability), (b) sensory disability (i.e., seeing- or hearing-related disability), (c) psychiatric/mental disability (e.g., bipolar disorder, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder), or (d) neurodevelopmental disability (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, learning disability, or ADHD). Participants’ disabilities were apparent/visible (i.e., recognizable by others without the person disclosing they have a disability) or hidden (i.e., others are unlikely to know the individual has a disability, so the person must disclose they have a disability for it to be known), and they could identify with one or more disability categories listed above. Ninety individuals provided usable responses. Table 1 details participant demographics. The bulk of the sample, 84.43%, identified as having two (36.66%), three (26.66%), or four (21.11%) nondominant cultural identities out of the six identities the study targeted, while the rest of the sample comprised individuals who noted six (n = 2; 2.22%), five (n = 4; 4.4%), one (n = 7; 7.77%), or no (n = 1; 1.11%) nondominant identities.

Of note, a higher percentage of participants with hidden or both apparent and hidden disabilities participated in the qualitative portion of the study compared to those who completed only the quantitative portion (45.5% compared to 41.8% and 33.3% compared to 27.4%, respectively). Similarly, there was a lower response rate from participants who earned a high school diploma or GED (5.6%), completed an associate degree or trade school (7.8%), completed some college (7.8%), or earned a doctoral degree (10%). There was an increase in responses from participants who earned a bachelor’s degree (26.7% compared to 21.9% in the quantitative portion) or a master’s degree (42.2% compared to 35.8%, respectively).

Data Analysis

We analyzed data for this study using MacQueen et al.’s (1998) framework to create a codebook to promote coder consistency. We established six codes, four of which were definitionally congruent with the AMS subscales (i.e., Helplessness, Minimization, Denial of Personhood, and Otherization; Conover et al., 2017a). While we used Conover et al.’s definitions as the foundation, we utilized Keller and Galgay’s (2010) definitions to add additional nuance. The next code, Other Data, was an a priori code reserved for data that did not fit the AMS subscale codes. After completing the pilot, we added a sixth code, Fortitude/Resilience/Coping, to capture data that demonstrated ways in which participants developed strengths, dealt with adversity and microaggressions, and persevered despite their microaggressive experiences. Identifying PWD’s fortitude/resilience/coping abilities is indicative of a strengths-based framework that promotes inclusion, equity, and higher quality of life. Research has shown that resilience in PWD such as improved well-being, higher social role satisfaction, and lower mental health symptoms are correlated with positive psychological and employment outcomes (Ordway et al., 2020; Norwood et al., 2022). Once this code was established, the Other Data code was used for any data that did not fit the five a priori codes. After the pilot, we added to the codebook definitions for clarity—though no codes were changed. All codes we established had substantial representation in the data and are reported as themes in the results section. The auditor (second author Melissa D. Deroche) gave feedback on the codebook and confirmed the codebook was sound prior to analysis.

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 90)

| Variable |

n |

% |

| Disability Type |

|

|

|

Single Type: Physical |

21 |

23.33 |

|

Single Type: Sensory |

17 |

18.88 |

|

Single Type: Neurodevelopmental |

6 |

6.66 |

|

Single Type: Psychiatric/Mental Health |

6 |

6.66 |

|

Combination (2): Physical and Psychiatric/Mental Health |

8 |

8.88 |

|

Combination (2): Neurodevelopmental and Psychiatric/Mental Health |

6 |

6.66 |

|

Combination (2): Sensory and Psychiatric/Mental Health |

5 |

5.55 |

|

Combination (2): Sensory and Physical |

4 |

4.44 |

|

Combination (2): Neurodevelopmental and Physical |

2 |

2.22 |

|

Combination (2): Sensory and Neurodevelopmental |

2 |

2.22 |

|

Combination (3): Physical, Psychiatric/Mental Health, Neurodevelopmental |

4 |

4.44 |

|

Combination (3): Physical, Sensory, Neurodevelopmental |

4 |

4.44 |

|

Combination (3): Sensory, Psychiatric/Mental Health, Neurodevelopmental |

2 |

2.22 |

|

Combination (3): Physical, Sensory, Psychiatric/Mental Health |

1 |

1.11 |

|

Combination (4): Physical, Sensory, Psychiatric/Mental Health,

Neurodevelopmental |

2 |

2.22 |

| Visibility of Disability |

|

|

|

Visible/Apparent |

19 |

21.11 |

|

Hidden/Concealed |

41 |

45.55 |

|

Both |

30 |

33.33 |

| Biological Sex/Sex Assigned at Birth |

|

|

|

Female |

74 |

82.22 |

|

Male |

16 |

17.77 |

| Gender Identity |

|

|

|

Gender Fluid/Gender Queer |

6 |

6.66 |

|

Man |

16 |

17.77 |

|

Woman |

68 |

75.55 |

| Affectual/Sexual Orientation |

|

|

|

Asexual |

2 |

2.22 |

|

Bisexual |

9 |

10.00 |

|

Gay |

2 |

2.22 |

|

Heterosexual |

68 |

75.55 |

|

Lesbian |

3 |

3.33 |

|

Pansexual |

4 |

4.44 |

|

Queer |

1 |

1.11 |

|

Questioning |

1 |

1.11 |

| Racial/Ethnic Identity |

|

|

|

African American/Black |

4 |

4.44 |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

3 |

3.33 |

|

Biracial |

2 |

2.22 |

|

Euro-American/White |

69 |

76.66 |

|

Indigenous |

1 |

1.11 |

|

Jewish |

5 |

5.55 |

|

Latino/a or Hispanic |

3 |

3.33 |

|

Middle Eastern |

1 |

1.11 |

|

Multiracial |

2 |

2.22 |

| Religious/Spiritual Identity |

|

|

|

Atheist |

8 |

8.88 |

|

Catholic |

12 |

13.3 |

|

Jewish |

4 |

4.44 |

|

Not Religious |

1 |

1.11 |

|

Pagan |

1 |

1.11 |

|

Protestant |

36 |

40.00 |

|

Questioning |

2 |

2.22 |

|

Spiritual Not Religious |

5 |

5.55 |

|

Unitarian Universalist |

2 |

2.22 |

|

Self-Identify in Another Way |

19 |

21.11 |

| Highest Level of Education |

|

|

|

High School Diploma or GED |

5 |

5.55 |

|

Associate or Trade School Degree |

7 |

7.77 |

|

Some College, No Degree |

7 |

7.77 |

|

Bachelor’s Degree |

24 |

26.66 |

|

Master’s Degree |

38 |

42.22 |

|

PhD, EdD, JD, MD, etc. |

9 |

10.00 |

|

No Response |

1 |

1.11 |

| Employment Status |

|

|

|

Full-Time |

40 |

44.44 |

|

Part-Time |

16 |

17.77 |

|

Retired |

9 |

10.00 |

|

Student |

11 |

12.22 |

|

Unemployed |

14 |

15.55 |

| Employment Compared to Training and Skills |

|

|

|

Training/Education/Skills are lower than job responsibilities/position |

2 |

2.22 |

|

Training/Education/Skills are on par with job responsibilities/position |

42 |

46.66 |

|

Training/Education/Skills exceed job responsibilities/position |

24 |

26.66 |

|

Not applicable |

22 |

24.44 |

|

|

|

|

|

We began analysis by piloting 10% of the data (n = 9) using the initial codebook (Boyatzis, 1998). Two researchers (first and third authors Jennifer M. Cook and Lee Za Ong) coded data independently and then worked together to reach consensus. Once the pilot analysis was complete, we coded the remaining data and recoded pilot data to ensure they fit the revised coding frame. After all data were coded, we further coded the data that were assigned to Other Data using in vivo codes to establish codes that best captured the data. We identified five codes within Other Data: Contextual Factors, Impact of Microaggressions/Ableism on Mental Health/Wellness, Microaggression Experiences Are Different Depending on Visibility of Disability, Internalized Ableism, and Microaggressions Include Identities Other Than Disability.

Trustworthiness

Cook and Ong coded all data independently and then met to reach consensus. Prior to coding commencement, we identified our beliefs and potential biases about the data and discussed how they might impact coding; we continued these conversations throughout analysis. For the pilot coding phase, independent coder agreement prior to consensus was 40%. Independent coder agreement prior to consensus during regular coding was 56%, and 69% for Other Data independent coding. We reached consensus for all coded data through a team meetings consensus process (Boyatzis, 1998). Finally, we utilized an auditor (Deroche). Deroche reviewed all consensus findings during all analysis stages. The coding team met with the auditor to resolve questions and discrepancies, such as a few instances in which data were misassigned to a code.

Research Team

The research team comprised three cisgender women between the ages of 45 and 55 who are all licensed professional counselors and work as counselor educators. Cook and Deroche identify as White and hold PhDs in counselor education, while Ong holds a PhD in rehabilitation psychology and is Asian American of Chinese descent and an immigrant from Malaysia. Deroche identifies as a person with a disability, Deroche and Ong have worked extensively with PWD, and all three authors have conducted research about PWD. Cook has abundant publications in qualitative research designs related to multicultural counseling. Finally, all three authors have extensive research training and experience in qualitative and quantitative research designs.

Findings

The findings described below are organized into two categories: findings that align with the AMS subscales and unique findings that are independent of the AMS subscales. Themes are listed in their appropriate category with participants’ quotes to illustrate and substantiate each theme (see Table 2). When we provide participant quotes, we refer to them by their randomly assigned participant numbers (e.g., P105, P109).

Table 2

Categories and Themes

| Category/Theme |

n |

% of Sample |

| Category 1: Findings That Align With the AMS Subscales |

|

|

|

Minimization |

35 |

38.88 |

|

Denial of Personhood |

26 |

28.88 |

|

Otherization |

17 |

18.88 |

|

Helplessness |

16 |

17.77 |

| Category 2: Unique Findings Independent of the AMS Subscales |

|

|

|

Fortitude/Resilience/Coping |

27 |

30.00 |

|

Contextual Factors |

17 |

18.88 |

|

Impact of Microaggressions/Ableism on Mental Health/Wellness |

10 |

9.00 |

|

Microaggression Experiences Are Different Depending on Visibility of Disability |

6 |

6.66 |

|

Internalized Ableism |

4 |

4.44 |

|

Microaggressions Include Identities Other Than Disability |

4 |

4.44 |

Note. N = 90.

Category 1: Findings That Align With the AMS Subscales

Our analysis revealed that the AMS a priori codes fit the study data. As such, the codes were transitioned to themes: Minimization (n = 35), Denial of Personhood (n = 26), Otherization (n = 17), and Helplessness (n = 16). The quotes selected for each theme illustrate the lived experiences of the theme definitions and add context and nuance about the impact of ableist microaggressions.

Minimization

Conover et al. (2017a) defined Minimization as microaggression experiences demonstrating the belief that PWD are “overstating their impairment or needs” and that “individuals with a disability could be able-bodied if they wanted to be or that they are actually able-bodied” (p. 581). Thirty-five of the 90 participants’ responses (33.33%) indicated instances of Minimization.

For example, P105 described incidents from their formative years that highlight the belief that PWD are, in fact, able-bodied and overstating their impairment:

As a child, children and adults alike would test the limits of my blindness. My piers [sic] would ask me how many fingers they were holding up. And in one instance, teachers lined a hallway with chairs to see if I’d run into them. Spoiler alert, I did.

P109 spoke to their interactions with family that highlight how disbelief about a person’s disability can result in Minimization:

Family is really bad. They still don’t believe me. I was asked (when I couldn’t climb stairs into a restaurant) are you trying to make a point? My visible disability has gotten worse over 40 years. I think because they saw me before I started using a cane, they just won’t believe me.

P158 illuminated a fallacy that can result in Minimization: “Because my disability is invisible people assume I need no help, [and] when I do, they discount my disability. I hear, ‘you don’t look like you have a disability‚’ ‘don’t sell yourself short.’”

Finally, P137 spoke to the blame that underlies Minimization:

On[e] of the most frequent microaggressions encountered living with my particular invisible disability (type 1 diabetes) is the ableist idea that health is entirely a personal responsibility. There is this assumption that whatever problems we face with our health are a direct result of poor choices (dietary, financial) completely ignoring the systematic problems with for-profit health care in this country.

Denial of Personhood

Denial of Personhood is characterized by PWD being “treated with the assumption that a physical disability indicates decreased mental capacity and therefore, being reduced to one’s physicality” (Conover et al., 2017a, p. 581); such microaggressions can occur “when any aspect of a person’s identity other than disability is ignored or denied” (Keller & Galgay, 2010, p. 249). Twenty-six participants (28.88%) endorsed this theme. For example, P142 described their experiences in the workplace that illustrate the erroneous belief that PWD have diminished mental capacity: “All my life I was pushed out of jobs for not hearing. People would actually tell me, ‘if you can’t hear—how can you do anything’ even though all my performance reviews exceeded expectations.” P123 spoke to a similar sentiment: “[I] am often asked ‘what’s wrong with you?’ ‘how did you get through college?’” Finally, P173 summarized the belief that seemingly underlies Denial of Personhood microaggressions and issued a corrective action:

Disabled doesn’t mean stupid. We can figure out most things for ourselves and if we can’t we know to ask for help. Don’t tell us how to live our lives or say we don’t deserve love, happiness and children. If you don’t know the level of someone’s disability you shouldn’t have the right to judge them about such things.

Otherization

Seventeen participants (18.88%) described Otherization as part of their narrative responses. Otherization microaggressions are those in which PWD are “treated as abnormal, an oddity, or nonhuman, and imply people with disabilities are or should be outside the natural order” (Conover et al., 2017a, p. 581) and that their “rights to equality are denied” (Keller & Galgay, 2010, p. 249). Participants shared several examples of these types of microaggressions. For instance, P140 shared:

When we (PWD) ask for simple things (e.g., can you turn on the captioning) and people grumble, say they can’t, etc. it just reinforces that we’re not on equal footing and at least for me it eats away a little bit every time.

P185 indicated another manifestation of Otherization: “As a deaf person, I get frustrated when whoever I’m talking to stops listening when someone else (non-deaf person) speaks verbally, leaving me mid-sentence.” P108 shared that they have been “prayed for in public without asking,” while P106 expressed, “I hate when people compliment me on how well I push my chair or say I must have super strong arms. I just have normal arms not athletic looking or anything.”

Helplessness

Helplessness microaggressions are those in which PWD are “treated as if they are incapable, useless, dependent, or broken, and imply they are unable to perform any activity without assistance” (Conover et al., 2017a, p. 581). Sixteen participants (17.77%) described Helplessness microaggressions. For P174, the most common Helplessness microaggression they experience is when “people speak to the person I am with instead of to me. Drives me crazy! Worse is when the person I’m with answers for me.” P126 corroborated the “devastating” nature of when “people make decisions for you.” P129 shared that, “As a person with an invisible disability, I most often encounter microaggressions in the form of unsolicited advice when I disclose my disability.” Similarly, P134 noted:

Although my disability is not apparent, if people know about it, they often just act on my behalf without asking me for input or feedback. That is very frustrating and often does not change even if I bring it up to the individual who does it.

This final quote from P134 is powerful because it, like P174’s experience, demonstrates how people without disabilities participate in perpetuating ableism even when they were not the ones who initiated it.

Category 2: Unique Findings Independent of the AMS Subscales

As we indicated earlier, we separated data that did not fit into AMS codes and coded them using in vivo codes. This analysis resulted in six novel themes (i.e., Fortitude/Resilience/Coping, Contextual Factors, Impact of Microaggressions/Ableism on Mental Health/Wellness, Microaggression Experiences Are Different Depending on Visibility of Disability, Internalized Ableism, and Microaggressions Include Identities Other Than Disability) that are independent from the AMS-driven themes discussed in the prior section, yet are interrelated because they add unique insights and helpful context for understanding ableist microaggressions within the lived experiences of PWD.

Fortitude/Resilience/Coping

We defined Fortitude/Resilience/Coping as ways in which participants have developed strength, dealt with adversity/microaggressions, and persevered despite their microaggressive experiences. Thirty percent (n = 27) of participants disclosed a wide range of attitudinal and experiential tactics related to this theme. P103 shared, “I maintain what I call a healthy sense of humor about my own body and being disabled,” while P145 demonstrated a sense of humor as they shared how they cope:

I just have to remind them and myself that my brain works differently and that I am just as competent as anyone else. I have learned not to beat myself up when I forget something or can’t get my paperwork done correctly for the tenth time. (I really hate paperwork.)

Participants 138 and 127 both spoke directly to the role knowledge plays. P138 shared:

I want to put out there that knowledge & understanding are power. Knowing & understanding your rights as a person with a disability as well as knowing & understanding your unique experience with your own disability (to the best of your ability) is key to making forward strides in environments that can often times feel ableist.

P127 spoke to knowledge, too, with their belief that “most microaggressions stem from a lack of education. I am often the first person they have met with a disability and the experience makes them uncomfortable.”

Finally, P187 spoke to the power of their resilience and its impact on their life, experiences which they draw from to help others:

I’ve been physically and emotionally abused my entire life, until I took control and stopped it. I’m middle aged and it took me 40 years to forgive everything that I’ve . . . had to endure. Never from my family, or close friends, but it’s been a difficult life, and now I’m all ok with it and try to help others with disabilities that are having a hard time.

Contextual Factors

Seventeen participants (18.88%) described Contextual Factors, which are data that depict relational, situational, or environmental elements that impact participants’ experiences of ableist microaggressions.

P110 shared that “microaggressions can be hard to label because they can vary based on the relationship you have with the person.” P175 added: “Most times the microaggression I receive are by people when they don’t know me, or first meet me, as opposed to get to know me better.” P162 spoke to additional situational/relational nuances: “I have very different experiences depending on what assistive technology I’m using in a given space (basically to what degree I pass as able-bodied) and how people know me.”

P163 spoke to relational roles as well as environmental context: “The attitudes about me are distinctly divided between the power structures. A case manager, medical doctor, neighbor or family member will certainly show their attitude differently. The same goes for academic settings [versus] job placement.” For P152, “The worst comments have come from mental health therapists [who] are medical professionals who should be the most compassionate towards their patients.”

P117 and P131 both identified situational differences they have noticed. P117 shared, “I find that people have treated me differently at different ages and stages in my life, particularly when I was raising three children as a divorced mom.” P131 identified their work environment as positive: “I work in the field of vocational rehabilitation so [I] interact with more people who have a more nuanced understanding of disability than the general population.” However, P165 offered an alternate view, noting that “many microaggressions are more insidious or come from within the disabled community.”

Impact of Microaggressions/Ableism on Mental Health/Wellness

Ten participants (9%) expressed how microaggressions and ableism experiences have impacted their mental health and wellness. P172 stated, “I struggle with my mental wellness and I have been hospitalized for severe depression that manifests from a combination of my disability and situations that are overwhelming.” P157 expressed a similar combination effect of having a disability and being “ostracized” by others: “The combination is very heavy on my heart and leaves me feeling incredibly alone.”

P159 expressed feeling “pathetic and weak. Sometimes I feel useless and disgraced. Most of the time I feel dumb and stupid.” P103 added additional impacts while acknowledging the differences between their experiences and those of their colleagues of color: “None of these [microaggressions] were overt, but all contributed to stress and frustration and generalized anxiety. I have seen much worse with coworkers of color and disabled Black and Brown folks in my community.”

P126 admitted that completing the study survey “evoked difficult memories.” Additionally, this participant described the turmoil and cognitive dissonance they experience:

I’m reminded taking this survey of the inner conflict with identifying as disabled. Is my disability qualifying enough, will I be rejected? I felt hints of defensiveness emerge, like imposter syndrome. I also recognize that I desire to be abled and that keeps the conflict churning.

Microaggression Experiences Are Different Depending on Visibility of Disability

Six participants (6.6%) spoke to how individuals with hidden disabilities experience microaggressions differently than individuals with visible/apparent disabilities. P141 asserted that “because my disabilities are hidden, I don’t hear many microaggressions regarding me,” and P183 corroborated that microaggressions are “different the more severe and obvious the disabilities are.”

P146 suggested that “invisible disabilities offer up a whole different category of microaggressions than those with visible disabilities,” and P151 added that “hidden disabilities is [sic] a double edged sword,” highlighting both the privilege and the dismissiveness hidden disabilities can bring. P150 emphasized the privilege of others not knowing about their disability: “In some ways, this benefits me because I’m not associated with the stigma of a disability.”

Internalized Ableism

A small number of participants (n = 4) expressed comments that were consistent with Internalized Ableism. Internalized Ableism includes believing the stereotypes, myths, and misconceptions about PWD, such as the notion that all disabilities are visible and that PWD cannot live independently, and it can manifest as beliefs about their own disability or others’ disabilities. One manifestation of Internalized Ableism is when a PWD expresses that another’s disability is not real or true compared to their own disability. For example, P112 stated: “Every time I go out I have great difficulty finding available accessible parking. I watch & people using the spots are walking/functioning just fine. Sick of hearing about ‘hidden disability.’ I think the majority are inconsiderate lazy people.”

Another manifestation of Internalized Ableism can be when PWD deny the existence of ableist microaggressions. P183 shared:

I don’t think that most people have microaggressions toward PWD. Maybe that’s different the more severe and obvious the disabilities are. It tends to be older people like 60s or 70s that treat me differently period it seems like the younger generation just sees most of us as people not disabled people. And I also think the term ableist separates PWD and people without. If we don’t want to be labeled, we shouldn’t label them.

Microaggressions Include Identities Other Than Disability

For this final theme, four participants (4.44%) spoke to the complexity related to microaggressions when a PWD has additional nondominant cultural identities. P167 expressed the compounding effect: “I have multiple minoritized identities—the intersection leads to more biases.” P161 articulated the inherent confusion when one has multiple nondominant identities: “I do not know whether I am treated in the ways I indicated because of my disabilities or because I am a person of color.” These quotes highlight the inherent increase and subsequent impact on PWD who have more than one nondominant cultural identity.

Discussion

The purpose of our analysis was to illuminate participants’ lived experiences with ableist microaggressions that were important to them. We revealed contextual information about participants’ experiences that aligned with the AMS subscales (i.e., Minimization, Denial of Personhood, Otherization, and Helplessness). Although prior qualitative ableist microaggression studies (e.g., Coalson et al., 2022; Eisenman et al., 2020; Olkin et al., 2019) grounded their research in Keller and Galgay’s (2010) eight categories rather than in Conover et al.’s (2017a) four subscales, it is fair to say that our findings substantiate other researchers’ findings because Conover et al.’s four subscales were devised based on Keller and Galgay’s findings.

While the corroboration of prior research findings based on the AMS subscales is illustrative and essential, the crucial findings from this study lie in the unique themes that arose from the in vivo coding process (i.e., Fortitude/Resilience/Coping, Contextual Factors, Impact of Microaggressions/Ableism on Mental Health/Wellness, Microaggression Experiences Are Different Depending on Visibility of Disability, Internalized Ableism, and Microaggressions Include Identities Other Than Disability). These themes introduce both novel and less-explored aspects of disability and of ableist microaggressions.

Fortitude/Resilience/Coping is a unique theme. Participants described how they became stronger and persevered despite microaggressive experiences. Eisenman et al. (2020) were the first to identify microaffirmations within ableist microaggressions research and Coalson et al. (2022) found that their participants perceived benefits that came from microaggressive experiences; both are important contributions. However, both instances of seeming positives related to ableist microaggressions in these studies are framed within the context of how others acted toward PWD rather than the autonomous choices and personal development of the person with the disability in the face of adversity. Our findings demonstrate PWD’s abilities—both innate qualities and learned skills—that rendered life-giving fortitude, resilience, and coping in which they are personally empowered and persevere despite external stimuli; they are not dependent upon whether others act appropriately. This is a key finding for counselors because they have the ability to create a therapeutic environment in which PWD can process, develop, and refine their fortitude, resilience, and coping further, acknowledging that PWD have these skills already.

Unsurprisingly, some participants spoke to the impact of ableist microaggressions and ableism on their mental health and wellness; these impacts included depression, loneliness, stress, frustration, and feeling “pathetic and weak.” What was surprising is that only 9% of the sample spoke to this impact directly, given how well-documented the harmful mental health effects of microaggressions are (Sue & Spanierman, 2020). This seeming underrepresentation of mental health ramifications amongst participants led us to wonder, based on the high percentage of participants (30%) who endorsed Fortitude/Resilience/Coping, whether this specific sample had a uniquely high ability to cope with adversity as compared to the overall disability population or if it is possible that ableist microaggression experiences have begun to decrease. While we are unable to answer these questions directly as part of this study, we posit three considerations: (a) microaggressions continue to have a negative effect on some PWD and need to be screened for and attended to within the counseling process; (b) screening for and helping clients with disabilities name, develop, or refine coping, fortitude, and resilience can prove beneficial; and (c) it is worthwhile to continue to work to reduce microaggressive behaviors in every way possible.

Although we had an independent theme in which participants indicated the differences between apparent and hidden disabilities, the participant quotes within every theme illustrate these differences as well. For instance, within the Minimization theme, P137 highlighted that those with hidden disabilities may be told that “personal responsibility” is the cause of their disability, while P105 and P109 spoke to having to “prove” their apparent disability to others, including family. Having to prove one’s disability or not being believed tracks with several other researchers’ findings including Olkin et al. (2019), who found that medical professionals did not believe PWD’s symptoms and experiences. The Helplessness theme revealed differences such as P129 receiving unsolicited advice once people learn of their hidden disability; however, this theme revealed similarities, too. Participants with both apparent and hidden disabilities experienced others acting on their behalf without their consent.

The Microaggression Experiences Are Different Depending on Visibility of Disability theme may explain why a higher percentage of participants with hidden disabilities or those who have both hidden and apparent disabilities participated in the qualitative portion of the study than those with apparent disabilities, which was the higher percentage in the quantitative part of the study. By definition, microaggressions can leave those who experience them questioning whether what they experienced was real, and this could be compounded when PWD have hidden disabilities; these participants may have needed to express their experiences more than those with apparent disabilities. While our data demonstrate that having a hidden disability may be a protective factor from experiencing ableist microaggressions, their disability experience often can be overlooked or ignored, resulting in a form of minimization that is both congruent with and distinct from the Minimization subscale definition.

Participants made a case for how Contextual Factors, defined as relational, situational, and/or environmental components, impact microaggression experiences. Implicitly, several authors spoke to what we have named as Contextual Factors (e.g., Coalson et al., 2022; Eisenman et al., 2020; Miller & Smith, 2021), yet the specificity and nuance participants provided in this study warranted a distinct theme. Relationally, participants noted that whether the perpetrator knew them and if there was a relational power differential between them and the perpetrator (e.g., doctors or counselors vs. family member or neighbor) makes a difference. Damningly, P152 stated that “the worst comments” they have received “have come from mental health therapists.” Participants noted, too, that work environments, life stage, the type of assistive technology they are using at the time, and being part of the disability community can all be impactful in both affirming and deleterious ways. It is imperative that counselors assess and understand thoroughly each client’s specific contextual factors so they can identify ways in which clients have internal and external resources and support, as well as areas in which they may want strategies, support, resources, and, potentially, advocacy intervention.

A small number of participants (n = 4) spoke to Internalized Ableism. Although this was a less robust theme, it was important to report because it adds to professional knowledge about what some clients with disabilities might believe and express during counseling sessions. We defined Internalized Ableism as participants expressing stereotypes, myths, and misconceptions about PWD that can manifest as beliefs about their own disability or the disabilities of others. One participant expressed disdain for hidden disabilities and expressed disbelief about others’ needs to use parking for disabled persons, while another participant questioned whether most PWD experience ableist microaggressions. While our study findings are not congruent with these statements, counselors must take clients’ expressions seriously, work to understand how clients have developed these beliefs, and seek to understand their impact on the client who is stating them.

Finally, four participants indicated that Microaggressions Include Identities Other Than Disability. Given the high percentage of the sample that had multiple nondominant identities, it is curious that so few participants spoke to this phenomenon. However, we theorize that this may have to do with identity salience (Hunt et al., 2006) and the fact that this was a study about ableist microaggressions. For the participants who spoke to this theme, the important features they reported were the compounding effect of microaggressions when one has multiple nondominant identities and the inherent confusion that results from microaggressive experiences, particularly when one has multiple nondominant identities. Again, counselors must screen for and be prepared to address the complexity and the impact of ableist microaggressions based on each client’s unique identities and experiences.

Implications for Practice

The study findings illustrate the ubiquitous, troubling, and impactful nature of ableist microaggressions. These findings expose many counselors, supervisors, and educators to a world they may not know well or at all, while for others, these findings validate experiences they know all too well personally and professionally. We began this article with a quote from the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus: “Day by day, what you choose, what you think, and what you do is who you become.” This quote captures the charge we are issuing to counseling professionals: It is time to take action to become counseling professionals who think as, act as, and are disability-affirming professionals. The task at hand is for each counseling professional to decide what steps to take next to strengthen their disability-affirming identity based on their current awareness, knowledge, and skill level, as well as how they can enact their disability-affirming identity based on their professional roles.

Fundamentally, disability-affirming professionals validate, support, encourage, and advocate for and with PWD consistently throughout their professional activities. For many, this begins with developing their awareness and knowledge, followed later by their skills. Based on the findings presented in this article, we suggest counseling professionals engage in self-reflexivity by examining the ways in which they have unwittingly adopted the dominant discourses about disability, what they believe about the abilities and lives of PWD, how they understand disability within the context of other nondominant identities, and the ways in which they have participated in perpetuating ableist microaggressions. Without engaging in disability self-awareness development, professionals risk conveying ableist microaggressions to clients that can result in early termination, impede the therapeutic relationship, and/or inflict additional psychological harm (Sue & Spanierman, 2020). For example, counselors may assume that clients with disabilities have diminished social–emotional learning skills compared to clients without disabilities and initiate formalized assessment based on this assumption. While counselors should be attuned to all clients’ social–emotional skills, it can be damaging to PWD’s sense of self and the counseling relationship to assume their social–emotional learning skills are deficient rather than assessing how environments are not conducive to PWD’s social–emotional needs (Lindsay et al., 2023).

Counselors’ self-reflexive process is meant to foster self-awareness; to better equip counselors to recognize ableist microaggressions in clients’ stories when they occur in personal, training, and professional environments; and for them to avoid unintentionally communicating ableist microaggressions in their practice. To start this process, we encourage counselors to question whether any of the study findings rang true, whether as someone who has experienced ableist microaggressions or as one who has perpetrated them, and to ascertain whether their attitudes and beliefs about PWD differ based on the visibility of disability. Additionally, we proffer that counselors who engage in self-reflective activities, such as the ones mentioned above, and those who learn more about PWD’s lives and experiences are more apt to create a plan to work through any negative attitudes or biases they have and, in turn, refine their skills so they are more disability-affirming in their practice. Counselors who engage in these processes will benefit those they serve, whether clients, students, or supervisees.

This study represents only a slice of the microaggression experiences of PWD. We concur with Rivas and Hill (2023) that counselors must adopt an evolving commitment to develop disability counseling effectiveness. Ways that counselors can take steps toward developing their disability-affirmative counselor identity and effectiveness include familiarizing themselves with and applying the American Rehabilitation Counseling Association (ARCA) disability competencies (Chapin et al., 2018); reading additional studies (e.g., Olkin et al., 2019; Peters et al., 2017); listening to podcasts (e.g., Swenor & Reed, n.d.); reading blogs and books (e.g., Heumann & Joiner, 2020); and watching shows and movies that highlight PWD’s experiences, microaggressive and otherwise—PWD are telling their stories and want others to learn from them.

Within the relational context, no matter one’s professional roles, it is important to be prepared to attend to the interaction of identity constellations within professional relationships and the power dynamics that are present (Ratts et al., 2016). Broaching these topics initially, including ability status and similarities and differences with our experiences, is a helpful start; however, this is the beginning of the process, not the entire process. Accordingly, clinicians must continually assess PWD’s contextual factors and their impact, lived experiences of their multiple identities, resilience, fortitude, and coping skills. To do so, clinicians must first create space for clients to process their microaggression experiences through actively listening to their stories; allowing PWD to openly express their frustrations, anger, or other emotions; and validating their experiences using advanced empathy. In other words, it is critical not to dismiss such topics nor unilaterally make them the presenting problem—balance is needed to attend to microaggression experiences appropriately. Essentially, counselors need to guide clients to discern the impact and to identify what they need rather than doing it for them, and to be ready, willing, and able to advocate with and on behalf of clients. All advocacy actions must be discussed with clients so as to center their autonomy.

Clients’ resiliencies and strengths must be fostered unceasingly. It is not uncommon for clients who have experienced ableist microaggressions to feel diminished and worthless and to question their purpose. Counselors must prioritize assisting clients in naming their strengths and telling stories about how they have developed resiliencies, and they must encourage clients to draw on both when facing adversity—particularly ableist microaggressions. While the goal is to eradicate ableist microaggressions, we must reinforce with clients that they are armed with tools to safeguard against ableist microaggressions’ impact and that they can seek trusted support when they need it.

As we move forward into the future as disability-affirming counseling professionals, counselor educators and supervisors have a specific charge to include disability status and disability/ableist microaggressions as part of their professional endeavors when working with students and supervisees. For many, the aforementioned recommendations likely apply because they, too, did not receive education about disability and disability microaggressions (Deroche et al., 2020). This is a setback, but not a limitation. Counselor educators and supervisors are continual learners who seek additional awareness, knowledge, skills, and advocacy actions to positively impact their work with counselors-in-training. Webinars, disability-specific conference sessions, and engaging with community disability organizations are helpful ways to start, and we recommend counselor educators and supervisors engage in the same self-examination strategies mentioned above to begin combating any biases they may hold about PWD. More specifically, counselor educators and supervisors can introduce and teach the ARCA disability competencies to trainees and supervisees, deliberately integrate self-exploration activities regarding disability into coursework, direct trainees and supervisees to inquire about ability status in intake and assessment procedures, and use cultural broaching behaviors to model appropriate use with clients (Deroche et al., 2020).

Limitations and Future Research

There are important limitations to consider to contextualize the study findings. The data used in this analysis were the result of one open-ended prompt as part of a larger quantitative study. Although participants offered robust and illustrative responses, it is a significant limitation that no follow-up questions were asked. Additionally, because the study utilized the AMS (Conover et al., 2017b), we analyzed data using the AMS subscales. While this was an appropriate choice given the context, it limited our ability to compare our findings with other qualitative studies that used Keller and Galgay (2010) to explain their findings.

We recommend that future research investigates the unique themes from this study in more detail to ascertain whether they are applicable to the larger PWD population. We suggest that focus groups combined with individual interviews may help to tease out nuances and could potentially lead to developing theory related to ableist microaggressions and best practices that will support PWD. Finally, we propose that more in-depth intersectionality research would benefit PWD and the professionals who serve them. The confounding nature of microaggressions combined with individuals’ unique identity compositions that often include both nondominant and dominant identities can make this type of research challenging, yet both are the reality for many PWD and this research is therefore needed.

Conclusion

Ableist microaggressions are ubiquitous and damaging to PWD. Through our analysis, we found that participants’ experiences corroborated prior researchers’ findings related to established ableist microaggression categories and added new knowledge by introducing six novel themes. We envision a disability-affirmative counseling profession and offered concrete recommendations for clinicians, supervisors, and counselor educators. Together, we can create a reality in which all PWD who seek counseling services will experience relief, validation, and empowerment as we work to create a society that provides access to all.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information. SAGE.

Chapin, M., McCarthy, H., Shaw, L., Bradham-Cousar, M., Chapman, R., Nosek, M., Peterson, S., Yilmaz, Z., & Ysasi, N. (2018). Disability-related counseling competencies. American Rehabilitation Counseling Association (ARCA) Task Force on Competencies for Counseling Persons with Disabilities. https://arcaweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/ARCA-Disability-Related-Counseling-Competencies.pdf

Coalson, G. A., Crawford, A., Treleaven, S. B., Byrd, C. T., Davis, L., Dang, L., Edgerly, J., & Turk, A. (2022). Microaggression and the adult stuttering experience. Journal of Communication Disorders, 95, 106180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2021.106180

Conover, K. J., Israel, T., & Nylund-Gibson, K. (2017a). Development and validation of the Ableist Microaggressions Scale. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(4), 570–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017715317

Conover, K. J., Israel, T., & Nylund-Gibson, K. (2017b). Ableist Microaggressions Scale (AMS) [Database record]. APA PsycTESTS. https://doi.org/10.1037/t64519-000

Dávila, B. (2015). Critical race theory, disability microaggressions, and Latina/o student experiences in special education. Race, Ethnicity, and Education, 18(4), 443–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2014.885422

Deroche, M. D., Herlihy, B., & Lyons, M. L. (2020). Counselor trainee self-perceived disability competence: Implications for training. Counselor Education and Supervision, 59(3), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12183

Deroche, M. D., Ong, L. Z., & Cook, J. M. (2024). Ableist microaggressions, disability characteristics, and nondominant identities. The Professional Counselor, 13(4), 404–417. https://doi.org/10.15241/mdd.13.4.404

Eisenman, L. T., Rolón-Dow, R., Freedman, B., Davison, A., & Yates, N. (2020). “Disabled or not, people just want to feel welcome”: Stories of microaggressions and microaffirmations from college students with intellectual disability. Critical Education, 11(17), 1–21.

Heumann, J., & Joiner, K. (2020). Being Heumann: An unrepentant memoir of a disability rights activist. Beacon Press.

Hunt, B., Matthews, C., Milsom, A., & Lammel, J. A. (2006). Lesbians with physical disabilities: A qualitative study of their experiences with counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb00392.x

Keller, R. M., & Galgay, C. E. (2010). Microaggressive experiences of people with disabilities. In D. W. Sue (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact (pp. 241–268). Wiley.

Lindsay, S., Fuentes, K., Ragunathan, S., Lamaj, L., & Dyson, J. (2023). Ableism within health care professions: A systematic review of the experiences and impact of discrimination against health care providers with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 45(17), 2715–2731. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2107086

MacQueen, K. M., McLellan, E., Kay, K., & Milstein, B. (1998). Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods, 10(2), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X980100020301

Miller, R. A., & Smith, A. C. (2021). Microaggressions experienced by LGBTQ students with disabilities. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 58(5), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2020.1835669

Norwood, M. F., Lakhani, A., Hedderman, B., & Kendall, E. (2022). Does being psychologically resilient assist in optimising physical outcomes from a spinal cord injury? Findings from a systematic scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(20), 6082–6093. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1952320

Olkin, R., Hayward, H., Abbene, M. S., & VanHeel, G. (2019). The experiences of microaggressions against women with visible and invisible disabilities. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3), 757–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12342

Ordway, A. R., Johnson, K. L., Amtmann, D., Bocell, F. D., Jensen, M. P., & Molton, I. R. (2020). The relationship between resilience, self-efficacy, and employment in people with physical disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 63(4), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355219886660

Patel, D. R., & Brown, K. A. (2017). An overview of the conceptual framework and definitions of disability. International Journal of Child Health and Human Development, 10(3), 247–252.

Perrin, P. B. (2019). Diversity and social justice in disability: The heart and soul of rehabilitation psychology. Rehabilitation Psychology, 64(2), 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000278

Peters, H. J., Schwenk, H. N., Ahlstrom, Z. R., & Mclalwain, L. N. (2017). Microaggressions: The experience of individuals with mental illness. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 30(1), 86–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2016.1164666

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Rivas, M., & Hill, N. R. (2023). A grounded theory of counselors’ post-graduation development of disability counseling effectiveness. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 17(1). https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol17/iss1/7

Rolón-Dow, R., & Davison, A. (2018). Racial microaffirmations: Learning from student stories of moments that matter. Diversity Discourse, 1(4), 1–9. https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/4230ddcd-b196-4ee2-a5bf-18120b2b1f24/content

Rolón-Dow, R., & Davison, A. (2021). Theorizing racial microaffirmations: A critical race/LatCrit approach. Race Ethnicity and Education, 24(2), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1798381

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271

Sue, D. W., & Spanierman, L. (2020). Microaggressions in everyday life (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Swenor, B., & Reed, N. (Hosts). (n.d.). Included: The disability equity podcast [Audio podcast]. Johns Hopkins University Disability Health Research Center. https://disabilityhealth.jhu.edu/included

Jennifer M. Cook, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC, is an associate professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Melissa D. Deroche, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC-S, is an assistant professor at Tarleton State University. Lee Za Ong, PhD, LPC, CRC, is an assistant professor at Marquette University. Correspondence may be addressed to Jennifer M. Cook, University of Texas at San Antonio, Department of Counseling, 501 W. Cesar E. Chavez Blvd, San Antonio, TX 78207, jennifer.cook@utsa.edu.

May 22, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 1

Rebekah Cole, Christine Ward, Taqueena Quintana, Elizabeth Burgin

Military spouses face many challenges as a result of the military lifestyle. Much focus has been placed on enhancing the resilience of military spouses by both the military and civilian communities. However, no research currently exists regarding spouses’ perceptions of their resilience or how they define resilience for themselves and their community. This qualitative study explored the perceptions of eight military spouses regarding their resilience through individual semi-structured interviews. The following themes emerged: 1) shaped by service member and mission priority; 2) challenges within the military lifestyle; 3) outside expectations of spouse resilience; 4) sense of responsibility for family’s resilience; 5) individual resilience; and 6) collective resilience. We discuss ways military leadership and the counseling profession can best understand and enhance the resilience of military spouses.

Keywords: military spouses, resilience, military lifestyle, perceptions, counseling

Because of the unique stressors associated with the military lifestyle, military spouses are at an increased risk for poor mental health (Donoho et al., 2018; Mailey et al., 2018; Numbers & Bruneau, 2017). They may experience mental health concerns, such as anxiety and depression, due to a number of reasons, including separation from their deployed service member, loss of support networks after a relocation, or issues with adjusting to the uncertain and frequent changes of the military (Cole et al., 2021). Additional concerns that arise, such as employment, marital, and financial issues, can also negatively affect the military spouse’s mental health (Cole et al., 2021; Mailey et al., 2018). Dorvil (2017) reported that 51% of active-duty spouses experience more stress than normal. Furthermore, 25% of military spouses meet the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (Blue Star Families [BSF], 2021). Depression in military spouses is also higher than the rate found within the general population (Verdeli et al., 2011). As a military spouse casts aside their own personal needs to support their service member, stressors may continue to increase, which can contribute to the rise of mental health needs of military spouses (Moustafa et al., 2020).

Resilience and Military Spouses

Nature of Resilience

Given the challenges inherent in the military lifestyle and the associated mental health risks, military spouse resilience is essential. Resilience is a complex and multifaceted construct, significant to researchers, practitioners, and policymakers across numerous disciplines, including mental health and military science. The American Psychological Association (2020) defined resilience as “the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or even significant sources of stress” (para. 4). Within the military community, resilience has been defined as the ability to withstand, recover, and grow in the face of stressors and changing demands (Meadows et al., 2015). Importantly, determinants of resilience include the interaction of biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors in response to stressors (Southwick et al., 2014). In addition to these salient variables embedded in resilience science, resilience may be operationalized as a trait (e.g., optimism), process (e.g., adaptability in changing conditions), or outcome (e.g., mental health diagnosis, post-traumatic growth; Southwick et al., 2014).

Resilience may also vary on a continuum across domains of functioning (Pietrzak & Southwick, 2011) and change as a function of development and the interaction of systems (Masten, 2014). Accordingly, a definition and operationalization of resilience may vary by population and context (Panter-Brick, 2014). During the post-9/11 era, the resilience of service members and their families received significant attention from stakeholders, including the Department of Defense (DoD) and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), both of which expressed a commitment to conducting research and establishing programming to enhance service member and military family resilience, resulting in increased awareness of the importance of service member and family resilience throughout the military community (NASEM, 2019).

Military Family Resilience

Though military families share the characteristics and challenges of their civilian counterparts, they additionally experience the demanding, high-risk nature of military duties; frequent separation and relocation; and caregiving for injured, ill, and wounded service members and veterans (Joining Forces Interagency Policy Committee, 2021). In recognition of the constellation of military-connected experiences military families face, the Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (DCoE) commissioned a review of family resilience research and relevant DoD policies to inform a definition of resilience for appropriate application to military spouses and children (Meadows et al., 2015). Meadows and colleagues (2015) proposed family resilience may be best defined as “the ability of a family to respond positively to an adverse situation and emerge from that situation feeling strengthened, more resourceful, and more confident than its prior state” (see Simon et al., 2005, for a further exploration of family resilience). Further, Meadows and colleagues identified two groups of policies delineated at the Joint Chiefs of Staff or DoD levels, or within individual branches of the military: 1) existing programs modified to augment resilience or family readiness, and 2) new programs developed to target family resilience. Programs established by these policies support access to mental health services (e.g., DoD Instruction [DoDI] 6490.06); parenting education (e.g., New Parent Support Program, DoDI 6400.05); child welfare (e.g., Family Advocacy Program, DoD Directive 6400.1); and myriad physical, psychological, social, and spiritual resources. The well-being of military families represents a critical mission for the DoD, extending beyond provision and access for families to meet their basic needs to individual service member and unit readiness, and the performance, recruitment, and retention of military personnel (NASEM, 2019).

Military Spouse Resilience

Though service member and family resilience are critical for accomplishing the DoD’s mission, focusing on the unique nature of military spouse resilience is key for understanding and supporting this population’s resilience. Counseling, psychology, sociology, and military medical professional research related to military spouse resilience has focused primarily on characteristics associated with resilience. In a study by Sinclair et al. (2019), 333 spouse participants completed a survey regarding their resilience, mental health, and well-being. The results revealed that spouses who had children, were a non-minority, had social support, had less work–family conflict, and had a partner with better mental health were more resilient. Another survey study examined the characteristics associated with resilience in Special Operations Forces military spouses, determining that community support and support from the service member was essential for spouse resilience (Richer et al., 2022). A study conducted within the communication field also explored spouses’ communicative construction of resilience during deployments. Qualitative data analysis of interviews with 24 spouses indicated how spouses use communication to reconcile their contradictory realities, which increases their resilience (Villagran et al., 2013). This resilience has also been found to be a protective factor against depression and substance abuse during military deployments (Erbes et al., 2017). Finally, a survey study of Army spouses (N = 3,036) determined that spouses who were less resilient were at higher risk for mental health diagnoses (Sullivan et al., 2021). While these studies explored the nature of resilience demonstrated by military spouses, our searches in JSTOR, PubMed, ERIC, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar did not reveal any studies regarding spouses’ perceptions of their own resilience or how they define this resilience for themselves and their community. Our study fills that research gap by exploring active-duty spouses’ perceptions and definitions of resilience.

Methods

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore the perceptions of active-duty spouses regarding their resilience. This study was guided by the following research questions: 1) What are military spouses’ perceptions of their own resilience? and 2) How do military spouses define “resilience?” Phenomenology seeks to present a certain phenomenon in its most authentic form (Moustakas, 1994). In order to most authentically and openly describe our participants’ experiences, we chose a qualitative transcendental phenomenological approach to frame our study. This tradition of qualitative research focuses on portraying a genuine representation of the participants’ perceptions and experiences. However, the distinct feature of transcendental phenomenology is its first step, which involves the researchers recognizing and bracketing their biases so they can analyze the data without any interference (Moerer-Urdahl & Creswell, 2004). We selected this design because each of our research team members were military spouses. We therefore recognized the need to mitigate our biases in order to give a true representation of the participants’ perceptions, free from our own preconceived notions.

Participants

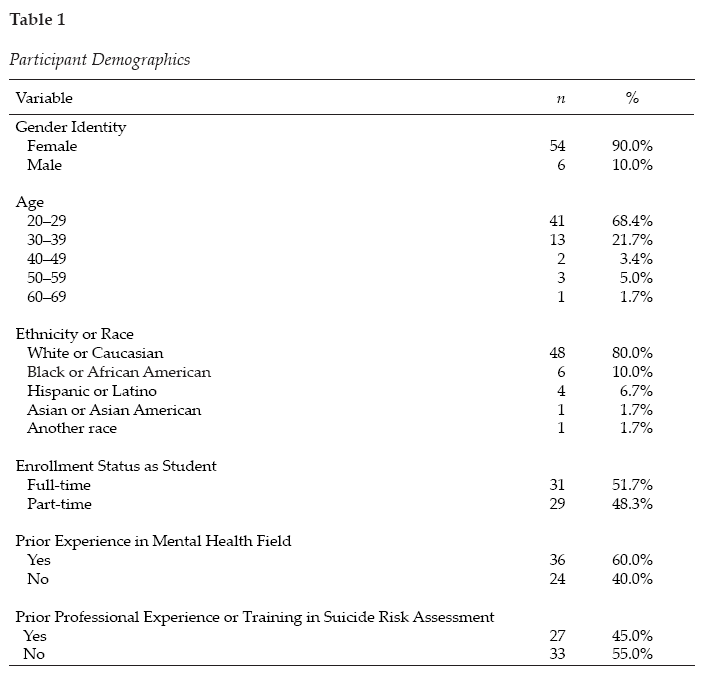

The participants in this study were selected based on their status as active-duty military spouses and their willingness to participate in the study. There were no other inclusion or exclusion criteria for the participants in this study. After gaining IRB approval, we used convenience sampling to recruit eight participants. In qualitative research, convenience sampling is used to recruit participants who are closely accessible to the researchers (Andrade, 2021). Our research team emailed participants that we knew through living, working, and volunteering on military bases throughout the United States and at overseas duty stations who fit the active-duty military spouse criteria for this study and asked them if they were willing to participate in the study. Once the participants expressed interest, they were provided with an information sheet regarding the study’s purpose and the nature of their involvement in the study. Participant demographics are included in Table 1. All of the participants were female and all were between the ages of 30–40. Four branches of the U.S. military, including Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps, were represented in the sample. No reservist, Coast Guard, or Space Force military spouses participated in our study. Five of our participants were White and three were Black. Their tenure as military spouses ranged from 4 years to 17 years. Five of the spouses were married to a military officer, while three of the participants were married to an enlisted service member. After interviewing these eight participants, our research team met and determined that because of the distinct common patterns we found across each of the participants’ transcripts, we had reached saturation and did not need to recruit any additional participants for our study (Saunders et al., 2018).

Table 1

Participant Demographics

| Participant |

Age |

Ethnicity |

Gender |

Branch |

Spouse’s Rank |

Years as a Spouse |

| 1 |

33 |

Black |

Female |

Air Force |

Enlisted |

4 |

| 2 |

36 |

Black |

Female |

Navy |

Enlisted |

17 |

| 3 |

31 |

White |

Female |

Army |

Officer |

7 |

| 4 |

34 |

Black |

Female |

Navy |

Enlisted |

14 |

| 5 |

36 |

White |

Female |

Marine Corps |

Officer |

12 |

| 6 |

35 |

White |

Female |

Marine Corps |

Officer |

14 |

| 7 |

40 |

White |

Female |

Navy |

Officer |

16 |

| 8 |

34 |

White |

Female |

Navy |

Officer |

10 |

Data Collection

Our research team first developed the interview protocol for the study based on a thorough review of the literature regarding resiliency within military culture as well as the challenges of the military lifestyle for military spouses. Our research team members interviewed each of the participants for 1–2 hours. These semi-structured interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by an automated transcription service. The interview questions were open-ended and focused on the spouses’ definitions of resilience and their perceptions of their resilience within the military lifestyle and culture (see Appendix for interview protocol). In addition, probing questions such as “Can you explain that a bit more?” or “Can you give any examples of what you mean by that?” were used to gather more in-depth data throughout the interviews.

Data Analysis