Aug 18, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 3

Melissa Sitton, Tina Du Rocher Schudlich, Christina Byrne, Chase M. Ochrach, Seneca E. A. Erwin

A family systems framework guided our investigation of self-injurious behavior (SIB) in adolescents. As part of a larger study, we collected data examining SIB and family functioning from 29 adolescents (Mage = 15.66) and their caregivers. These adolescents with traits of borderline personality disorder were seeking counseling from community-based practitioners specializing in dialectical behavior therapy. Our primary aim was to better understand the family environment of these adolescents. A second aim was to elucidate interrelations among family communication, roles, problem-solving, affective involvement, affective responsiveness, behavioral control, and conflict and SIB. We found a high rate of SIB among adolescent participants. There was significant congruence between adolescent and caregiver reports of the family environment, with families demonstrating unhealthy levels of functioning in several indicators of family environment. The latent variable of family functioning significantly predicted nonsuicidal and ambivalent SIB. Counselors working with adolescents should consider family functioning when assessing risk for SIB.

Keywords: self-injurious behavior, adolescents, family systems, borderline personality disorder, family functioning

Although emotion dysregulation and unstable personal relationships are common for adolescents, those with symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD) often report more extreme experiences (A. L. Miller et al., 2008). BPD is characterized by impaired or unstable emotional and social functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Individuals with BPD—especially adolescents—may experience impairments in daily functioning as well as within interpersonal relationships (Chanen et al., 2007).

Linehan’s (1993) biosocial theory proposed that BPD can result from an individual’s biological predisposition toward emotion dysregulation and a social environment that amplifies this vulnerability. Given that adolescents spend a substantial amount of time with their family, it is important to examine an adolescent’s familial environment to understand the etiology of BPD symptoms; such examination requires a framework like family systems theory, which emphasizes the relationships between family members rather than focusing on the individual members themselves (Goldenberg & Goldenberg, 2013); this includes family communication, roles, problem-solving, affective involvement, affective responsiveness, and behavioral control (I. W. Miller et al., 2000).

Self-Injurious Behavior (SIB)

Regrettably, it is common for adolescents with BPD to engage in SIB (Kaess et al., 2014). SIB is an umbrella term for all purposeful, self-inflicted acts of bodily harm, whether the intent is suicidal, nonsuicidal (i.e., nonsuicidal self-injury), or ambivalent (i.e., neither strictly suicidal nor nonsuicidal). In fact, SIB is one diagnostic criteria for BPD in adolescents and adults.

Although originally developed to explain the etiology of BPD, the biosocial theory has been applied to the development of SIB as well (Crowell et al., 2009). Countless studies have examined the role of emotion dysregulation and affective reinforcement in SIB, but it is important to also consider the influence of social variables. Indeed, in their four-function model, Nock and Prinstein (2004, 2005) suggested that both affective and social variables can positively and negatively reinforce nonsuicidal SIB. Similarly, Joiner’s (2005) interpersonal theory of suicidal SIB posited that social variables (particularly thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness) drive the desire for suicide. Thus, although there are clear links between affective variables and SIB, social variables are also relevant. For adolescents, an important social variable related to SIB is family environment. From the family systems approach, adolescent SIB is best understood when rooted in the context of family environment. As Levenkron (1998) suggested, “the ways in which all the family members relate to each other… [is] the fuel that drives [SIB]” (pp. 125–126).

Although limited in number, some previous studies have examined family environment and SIB in adolescents. For example, Halstead et al. (2014) found that SIB was related to dysfunctional family environments. Studies have also found relationships between adolescent SIB and familial communication (Halstead et al., 2014; Latina et al., 2015) and conflict (Huang et al., 2017). Additionally, Adrian et al. (2011) demonstrated a link between stress and failure to meet expectations of familial roles. To our knowledge, no studies to date have examined SIB and familial problem-solving, affective involvement, affective responsiveness, and behavioral control. However, studies have linked SIB to an individual’s lack of problem-solving skills (Walker et al., 2017), ability to regulate affective responses (Adrian et al., 2011), and behavioral control related to impulsivity and compulsivity (Hamza et al., 2015).

Current Study

Despite the clear influence of family members on SIB (Halstead et al., 2014) and the significant amount of time adolescents tend to spend with family members, more research is needed to evaluate family environment in relation to SIB. Specifically, we investigated the families of treatment-seeking adolescents with traits of BPD who engage in SIB. Our objectives were to: (a) assess family environment using multiple indicators of family functioning, (b) assess SIB in these treatment-seeking adolescents, including SIB done with suicidal intent, nonsuicidal intent, and ambivalence toward life, and (c) evaluate family functioning as a statistical predictor of lifetime SIB.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We used data from a larger ongoing, unpublished study on dialectical behavior therapy. In the larger study, participants were adolescents and young adults who sought counseling from community-based clinicians specializing in dialectical behavior therapy. Participants sought counseling for symptoms of BPD, particularly SIB. The counselors recruited participants for the research study by explaining voluntary research participation during their standard intake process for new clients at the clinic. The counselors also obtained informed consent for research from the participants. The counselors collaborated with researchers at a local university for this larger study, and the university’s IRB approved the study.

For the current study, we used the existing pretest data from the adolescents only (N = 29; Mage = 15.66, SDage = 1.34, age range = 13–18). A majority of the adolescent sample (82.8%; n = 24) reported no previous experience with counseling. This sample was predominately Caucasian (82.8%; n = 24) and most adolescents identified as female (89.7%; n = 26).

Caregiver participants (N = 29) were involved in the adolescents’ treatment and the accompanying research study. Most caregiver participants were the biological mother (81.5%; n = 22) or adoptive mother (7.4%; n = 2). However, a few adolescents were accompanied by an extended family member (7.4%; n = 2) or their biological father (3.7%; n = 1). A majority of adolescents reported that at least one of their caregivers had attended some (22.2%; n = 6) or all (29.6%; n = 8) of college, or some (3.7%; n = 1) or all (29.6%; n = 8) of graduate school.

Most adolescents reported they currently lived with both biological parents (58.6%; n = 17) or at least one biological parent (31.0%; n = 9), though some lived with non-biological parents or caregivers (10.3%; n = 3). Most adolescents (86.2%; n = 25) also reported having at least one sibling; 58.6% of adolescents (n = 17) reported having at least one biological brother, 37.9% had at least one biological sister (n = 11), and 24.1% had a half- or step-sibling (n = 7). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests demonstrated that adolescents did not differ in total SIB based on family characteristics (e.g., number of siblings, number of employed caregivers; all values of p > .05).

Measures

Family Functioning

The Family Assessment Device (FAD; Epstein et al., 1983) is a 53-item measure with a 4-point Likert scale used to rate agreement with statements about how the adolescents’ family members interact and relate to each other (e.g., “After our family tries to solve a problem, we usually discuss whether it worked or not”). Both adolescents and caregivers completed the FAD. Subscales of the FAD assess six dimensions of family functioning, including family problem-solving, roles, communication, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, and behavioral control. The scores for each subscale are averaged, with higher scores indicating worse functioning and more problems within families. The FAD has good test-retest reliability and construct validity (I. W. Miller et al., 1985). In this study, the reliability of the FAD was excellent for both samples (Cronbach’s alpha = .95 for adolescents and .96 for caregivers).

The Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Prinz et al., 1979) assesses self-reported familial interactions within the past two weeks. The CBQ has both an adolescent and a caregiver version; both versions consist of 20 true/false items. Scores can range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating more conflict between caregiver and adolescent. Studies have shown that CBQ scores delineated between distressed and non-distressed families (Robin & Foster, 1989). The CBQ has good internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Rallis et al., 2015; Robin & Foster, 1989), as well as construct validity (Prinz et al., 1979). In the current study, the reliability of the CBQ was excellent for both samples (Cronbach’s alpha = .88 for adolescents and .92 for caregivers).

Self-Injurious Behavior (SIB)

We used the Lifetime Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (LSASI; Linehan & Comtois, 1996) to assess participants’ history of SIB, including frequency, method, and intent. Using 20 items, the LSASI asks participants to report the dates of the most recent and most severe SIB, as well as their lifetime frequency of 11 different methods of SIB with suicidal intent, without suicidal intent, and with ambivalence. Participants also report the total frequency of each SIB method (combining suicidal, nonsuicidal, and ambivalent), and the number of times medical treatment was received for the SIB method. Higher scores indicate more SIB in the past. In the current study, reliability across all SIB intent types (four variables: suicidal SIB, nonsuicidal SIB, ambivalent SIB, and total SIB) was .65. Because the LSASI was designed for clinical use rather than research, to our knowledge there are no existing studies demonstrating the reliability or validity of the LSASI. Notably, this measure was already in use at the counseling clinic, and the decision to use it for this research study was counselor-driven.

Data Analysis

As part of our preliminary analyses, we first tested all variables for the assumptions of analysis. Specifically, when examining the skew and kurtosis of the composite variables, we used ± 2 as our acceptable range of values. Following advice from Tabachnick and Fidell (2019), we transformed variables that did not meet our criteria for normality.

To better understand family functioning, we conducted descriptive analyses for all seven predictive variables (problem-solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, behavioral control, and conflict) separately for adolescent and caregiver scores. We assessed the degree of healthy family functioning using I. W. Miller et al.’s (1985) suggested cut-off scores, which can be used to distinguish between healthy and unhealthy family environments. We also conducted paired sample t-tests to compare the adolescent and caregiver reports of family functioning.

Next, we tested the fit of our theoretical model of family functioning using structural equation modeling (SEM) with maximum likelihood as the method of estimation. We used multiple fit indices to assess the model fit. Specifically, the chi-square statistic assesses absolute model fit, demonstrating good fit when not statistically significant. The chi-square test can also be used to compare the relative fit of two models. Additionally, comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) are all indicators of model fit, with 0.95 or higher, 0.05 or lower, and 0.08 or lower indicating good fit, respectively (for more information on SEM fit indices, see Hooper et al., 2008). Notably, Iacobucci (2010) suggested that researchers can use SEM and establish good model fit even with small samples.

We also conducted descriptive analyses of the participants’ self-reported SIB. We left these variables raw (untransformed) to evaluate how participants viewed their own SIB. We examined the specific SIB methods that participants reported using (e.g., cutting, burning) as well as three outcome variables (suicidal SIB, nonsuicidal SIB, and ambivalent SIB; all transformed because of issues with skew and kurtosis).

Lastly, we used SEM to predict SIB with the proposed model of family functioning. Given our small sample size, we conducted this analysis separately for suicidal SIB, nonsuicidal SIB, and ambivalent SIB. We set alpha at .05 for each model; given the small sample size, we did not apply corrections to the alpha for the multiple analyses.

Results

We used SPSS 24.0 and Amos 24 to analyze our data. Because this study was primarily descriptive, we conducted multiple analyses to better understand the family environment of treatment-seeking adolescents, experiences of SIB for adolescents, and the role of family environment in adolescent engagement in SIB.

Family Characteristics and Functioning

Means, standard deviations, and range of scores for the family functioning variables are shown in Table 1. With the exception of the caregiver reports on affective responsiveness and behavioral control, both adolescent and caregiver reports on every subscale of the FAD fell above the McMaster clinical cut-off (see Table 1) described by I. W. Miller et al.’s (1985) cut-off scores, indicating on average all of the families demonstrated unhealthy functioning. It is worth noting that adolescents and their caregivers reported similar levels in five of the seven indicators of family functioning from the FAD and CBQ (e.g., there was no statistical difference between the two reports, all values of p > .05). As shown in Table 1, adolescent and caregiver reports only statistically differed for behavioral control (t[28] = 4.23, p < .001) and communication (t[28] = 2.96, p = .006). Specifically, adolescents reported higher levels of both behavioral control and communication; these high levels are considered indicative of unhealthy or distressed families (I. W. Miller et al., 1985).

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Group Comparisons of Family Functioning Variables as Reported by Adolescents and Caregivers

| Variable |

|

Adolescent |

Caregiver |

|

|

|

Cut-Off |

M |

SD |

Range |

M |

SD |

Range |

t(28) |

p |

| Problem-solving |

2.2 |

2.58 |

0.65 |

1.00–3.80 |

2.29 |

0.57 |

1.40–3.80 |

1.88 |

.071 |

| Communication |

2.2 |

2.56 |

0.37 |

1.83–3.17 |

2.30 |

0.37 |

1.50–3.00 |

2.96 |

.006 |

| Roles |

2.3 |

2.58 |

0.37 |

1.75–3.38 |

2.45 |

0.37 |

1.75–3.38 |

1.57 |

.128 |

| Affective Resp. |

2.2 |

2.34 |

0.68 |

1.00–4.00 |

2.12 |

0.62 |

1.00–3.67 |

1.48 |

.151 |

| Affective Inv. |

2.1 |

2.37 |

0.28 |

1.71–3.00 |

2.44 |

0.23 |

1.86–3.00 |

– 1.61 |

.118 |

| Behav. Control |

1.9 |

2.12 |

0.44 |

1.00–3.11 |

1.77 |

0.41 |

1.00–2.78 |

4.23 |

< .001 |

| Conflict |

— |

9.60 |

4.83 |

0.00–18.00 |

10.05 |

5.67 |

1.00–20.00 |

– 0.46 |

.649 |

Note. Cut-Off = McMaster Cut-Off score; Affective Resp. = Affective responsiveness; Affective Inv. = Affective involvement; Behav. Control = Behavioral control.

We used SEM to test the fit of our theory-driven, congeneric model of family functioning using seven subscales from each source (14 variables; seven for adolescents and seven for caregivers, with the error terms of each subscale correlated between the two sources) to predict family functioning as reported by each source (two latent variables; one for adolescents and one for caregivers). The absolute fit of the model was marginal: χ2(69) = 104.39, p = .004, CFI = 0.79, RMSEA = 0.14, SRMR = 0.14.

In order to reduce variables in our theoretical model, we averaged adolescent and caregiver reports for problem-solving, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, and conflict because these did not statistically differ (all values of p > .05). However, we kept the two reports as separate predictors for communication and behavioral control. This left us with nine predictor variables for subsequent analysis (five averaged predictors and four single-source predictors).

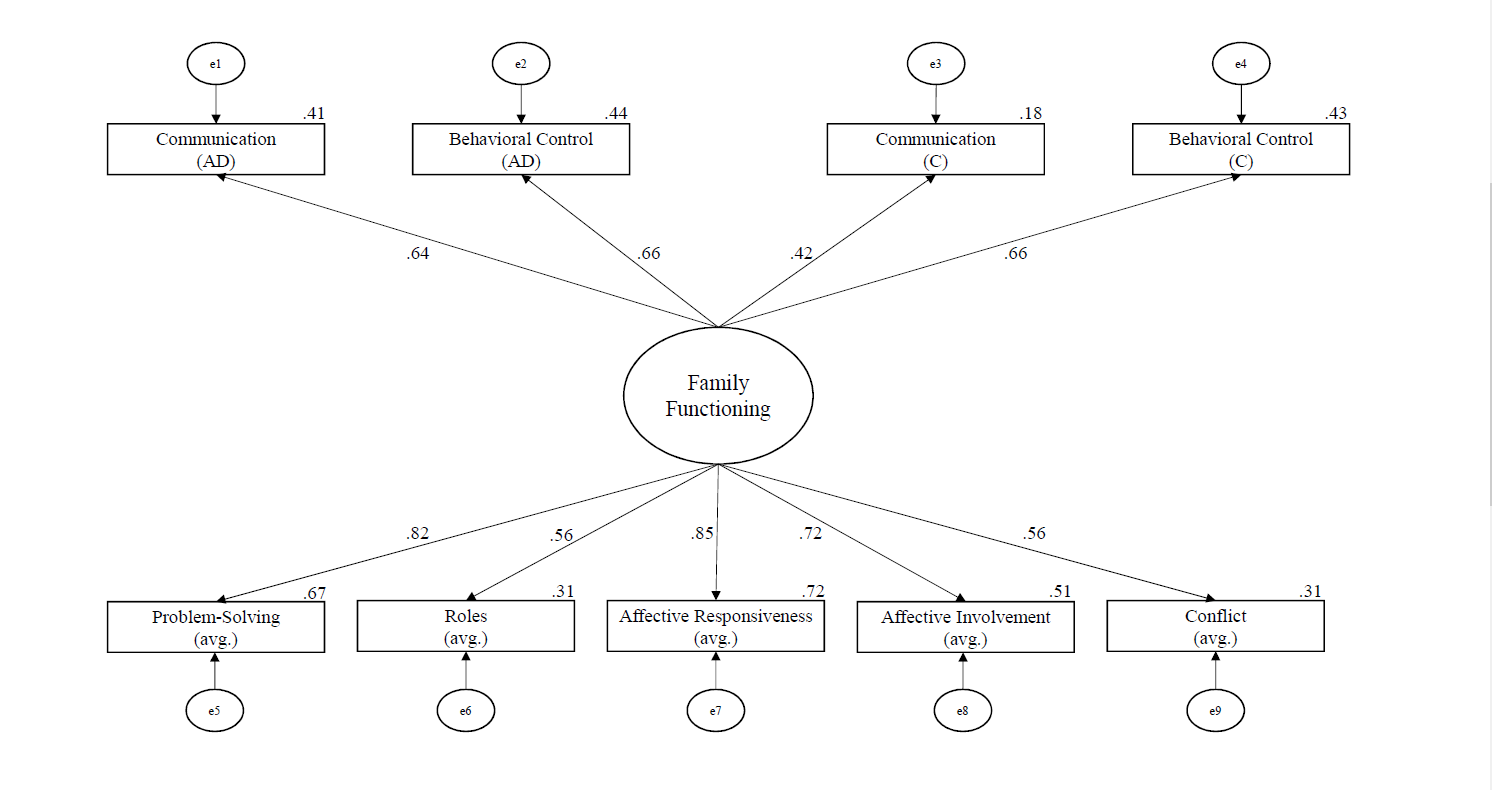

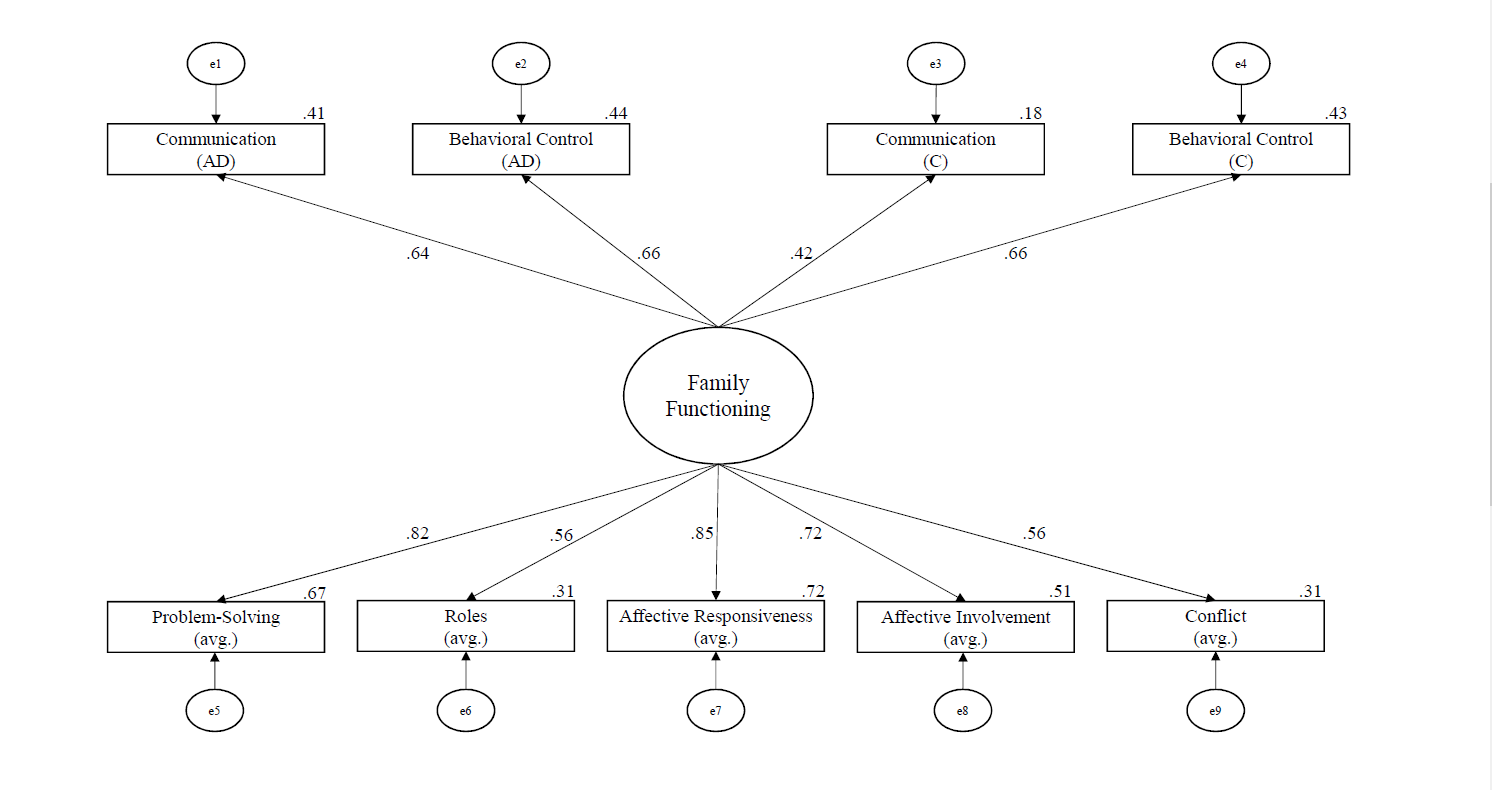

Next, we used SEM to test the fit of the simplified model with the nine observed variables and one latent variable of family functioning. We found that the absolute model fit of this simplified model was acceptable overall. Specifically, the fit indices mostly indicated good fit (χ2[27] = 33.11, p = .194, CFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.08), though one fit index suggested poor fit (RMSEA = 0.09). Differences in the chi-squares of our two models showed the simplified model was statistically better than the initial model: χ2(42) = 71.28, p = .003. Thus, we selected the simplified model as the final model of family functioning (see Figure 1). See Table 2 for descriptive analyses of the nine predictors in the final model. All variables were positively related to family functioning. The strongest predictors of family functioning in this model were affective responsiveness (average of adolescent and caregiver report; β = .85, B = 1.04, SE B = 0.21, p < .001, R2 = .72), affective involvement (averaged; β = .72, B = 0.88, SE B = 0.22, p < .001, R2 = .51), and problem-solving (averaged; β = .82, R2 = .67; this was the constrained parameter used to identify the regression model).

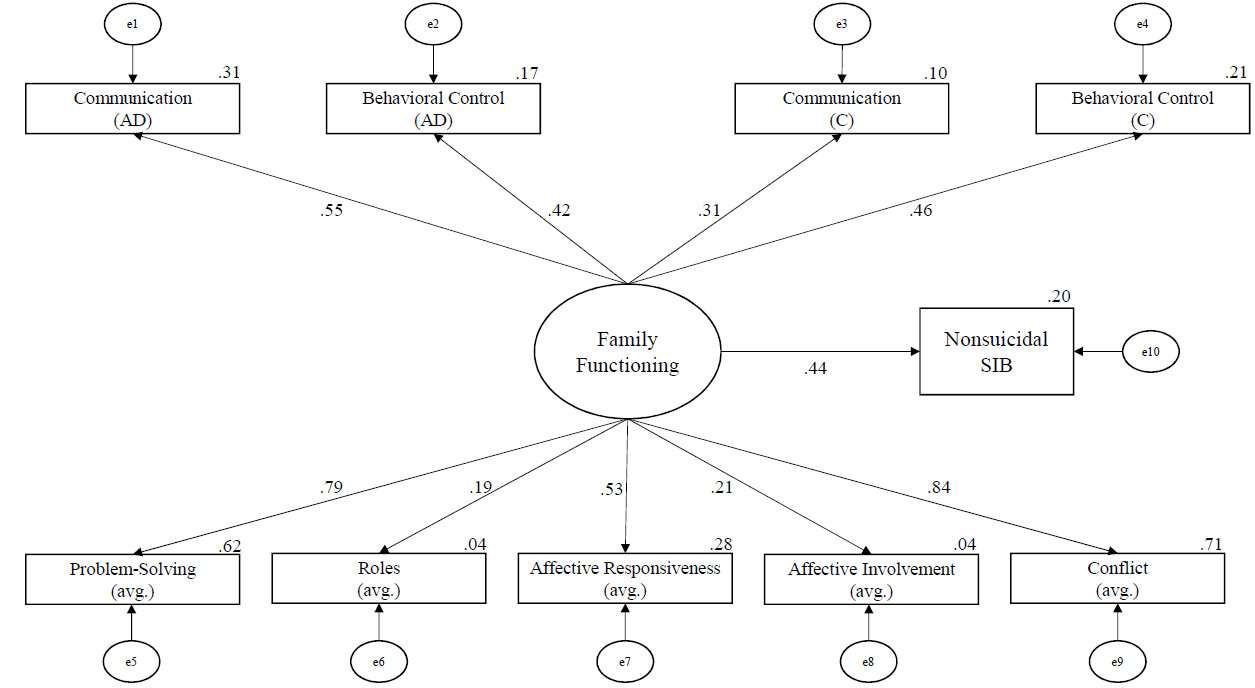

Figure 1

The Output Structural Regression Model of Family Functioning Developed Using SEM

Note. The large circle represents a latent variable, boxes are measured variables, small circles (with “e”) are error terms, and solid lines show regression paths. The numbers on paths are the standardized path coefficients, and the offset values on endogenous variables are the R² effect sizes. (AD) = adolescent report; (C) = caregiver report; (avg.) = averaged score of adolescent and caregiver report.

Table 2

Descriptive Analyses of Predictors of Family Functioning

| Variable |

M |

SD |

| Problem-Solving |

2.43 |

0.44 |

| Roles |

2.51 |

0.29 |

| Affective Responsiveness |

2.23 |

0.51 |

| Affective Involvement |

2.40 |

0.23 |

| Conflict |

9.82 |

4.56 |

| Communication (AD) |

2.56 |

0.37 |

| Communication (C) |

2.30 |

0.37 |

| Behavioral Control (AD) |

2.12 |

0.44 |

| Behavioral Control (C) |

1.77 |

0.41 |

Note. (AD) = adolescent report; (C) = caregiver report.

Adolescent Engagement in SIB

All adolescents reported engaging in SIB in their lifetime, and the average lifetime frequency of SIB was 438.72 (SD = 1,216.65, range = 1–6,079; transformed to address normality: M = 4.41, SD = 1.80). Specifically, most participants reported engaging in nonsuicidal SIB (n = 26) and using it with higher frequency than SIB with other intent (i.e., suicidal or ambivalent SIB), with a lifetime average of 340.16 (SD = 975.22, range = 0–4,565; transformed: M = 3.49, SD = 2.25). Many adolescents also reported engaging in ambivalent SIB (n = 18), with moderate average frequency rates (M = 22.28, SD = 52.02, range = 0–248; transformed: M = 1.62, SD = 1.69). Lastly, fewer adolescents reported engaging in suicidal SIB (n = 18), with the lowest average lifetime frequency (M = 7.34, SD = 25.03, range = 0–136; transformed: M = 0.97, SD = 0.95). See Table 3 for descriptive information on SIB methods (e.g., cutting) used by adolescents in our sample. On average, participants used 3.78 (SD = 2.15) methods of SIB in their lifetime.

Table 3

Descriptive Statistics for All Self-Injurious Behavior Completed in One’s Lifetime (N = 29)

| Variable |

n |

Ma |

SDa |

Rangea |

n of Severe Cases |

| Cutting |

27 |

179.55 |

330.42 |

0–1,500 |

7 |

| Hitting head/body |

16 |

240.90 |

730.59 |

0–3,000 |

0 |

| Overdosing |

13 |

1.88 |

3.59 |

0–15 |

7 |

| Burning |

13 |

6.12 |

14.99 |

0–60 |

1 |

| Strangling/hanging |

8 |

2.18 |

6.42 |

0–30 |

0 |

| Stabbing/puncturing |

8 |

0.80 |

1.64 |

0–7 |

2 |

| Asphyxiating |

7 |

1.66 |

3.90 |

0–15.62 |

0 |

| Other |

6 |

272.92 |

602.33 |

0–1,500 |

2 |

| Jumping |

4 |

1.27 |

5.31 |

0–25 |

1 |

| Drowning |

4 |

0.40 |

.99 |

0–4 |

0 |

| Poisoning |

3 |

0.14 |

.36 |

0–1 |

1 |

Note. The descriptive statistics are based on the total self-injurious behavior, combining acts completed with suicidal intent, nonsuicidal intent, and ambivalence. Other = adolescent-reported participating in a type of self-injury that was not listed; Jumping = jumping from a high place to cause injury; Severe Cases = requiring medical treatment.

a The frequency that adolescents reported engaging in the various methods of self-injury.

Predicting SIB With Family Functioning

To understand the relationships between family functioning and SIB, we conducted correlational analyses of the three outcome variables and nine predictors. As shown in Table 4, problem-solving was moderately associated with ambivalent SIB (r = .44 , p = .018), conflict was moderately associated with nonsuicidal SIB (r = .38 , p = .049), and adolescent-reported communication was moderately to strongly associated with all three SIB variables (suicidal r = .61, p < .001; nonsuicidal r = .47, p = .011; ambivalent r = .56, p = .002). All associations were positive (see Table 4), meaning that worse family functioning scores were associated with more SIB.

Table 4

Bivariate Correlations Between Predictor Variables

|

1. |

2. |

3. |

4. |

5. |

6. |

7. |

8. |

9. |

10. |

11. |

| 1. Nonsuicidal SIB |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Ambivalent SIB |

.35 |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Suicidal SIB |

.16 |

.46* |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. Problem-Solving |

.35 |

.44* |

.19 |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. Roles |

.21 |

-.01 |

.27 |

.39* |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. Affect. Resp. |

.25 |

.36 |

.28 |

.68*** |

.42* |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

| 7. Affect. Involv. |

.22 |

.13 |

.27 |

.52** |

.43* |

.72*** |

– |

|

|

|

|

| 8. Conflict |

.38* |

.35 |

.26 |

.66*** |

.14 |

.45* |

.15 |

– |

|

|

|

| 9. Comm. (AD) |

.47* |

.56** |

.61*** |

.57** |

.44* |

.51** |

.50** |

.43* |

– |

|

|

| 10. Comm. (C) |

.09 |

.11 |

.04 |

.42* |

.28 |

.29 |

.29 |

.27 |

.17 |

– |

|

| 11. Beh. Cont. (AD) |

.27 |

.06 |

-.21 |

.54** |

.48** |

.51** |

.56** |

.34 |

.41* |

.25 |

– |

| 12. Beh. Cont. (C) |

.27 |

.26 |

.13 |

.49** |

.53** |

.61*** |

.36 |

.38* |

.33 |

.40* |

.47* |

Note. SIB = self-injurious behavior; Affect. Resp. = Affective Responsiveness; Affect. Involv. = Affective Involvement; Comm. = Communication; (AD) = adolescent report; (C) = caregiver report; Beh. Cont. = Behavioral Control.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Next, we used SEM to predict SIB with our simplified model of family functioning. We tested three SIB outcomes separately because of concerns with sample size. For all models predicting SIB, we freed all FAD factors (problem-solving, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, adolescent-reported communication and behavioral control, and caregiver-reported communication and behavioral control) to correlate because variables from the same measure are likely to be related.

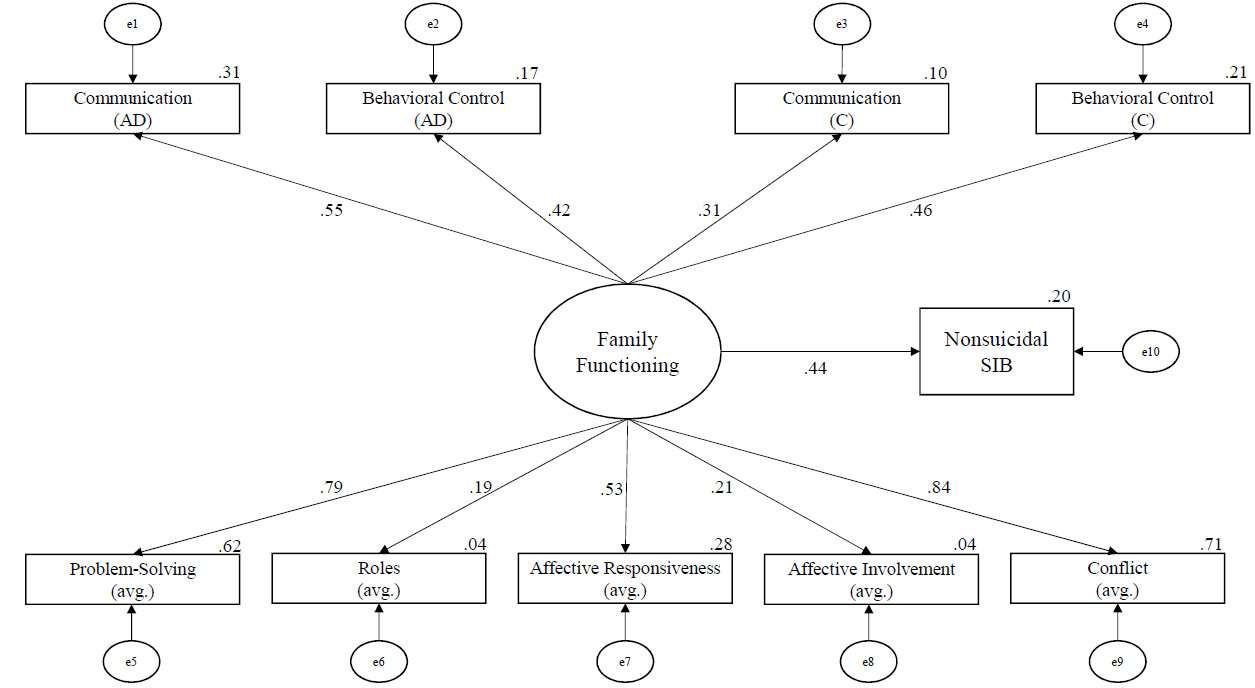

The model predicting nonsuicidal SIB had good absolute fit: χ2(7) = 4.28, p = .747, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.04. In all, family functioning explains 20% of the variance in nonsuicidal SIB. See Figure 2 for the standardized path coefficients between family functioning variables, the latent variable of family functioning, and nonsuicidal SIB. Notably, family functioning predicted nonsuicidal SIB:

β = .44, B = 1.27, SE B = 0.62, p = .039. Based on effect sizes (see Figure 2), the strongest predictors were problem-solving (averaged; β = .79, B = 0.90, SE B = 0.03, p = .008, R² = .62), communication (adolescent-reported; β = .55, B = 0.05, SE B = 0.03, p = .034, R² = .31), and conflict (averaged; β = .84, R² = .71; this was the constrained parameter used to identify the regression model).

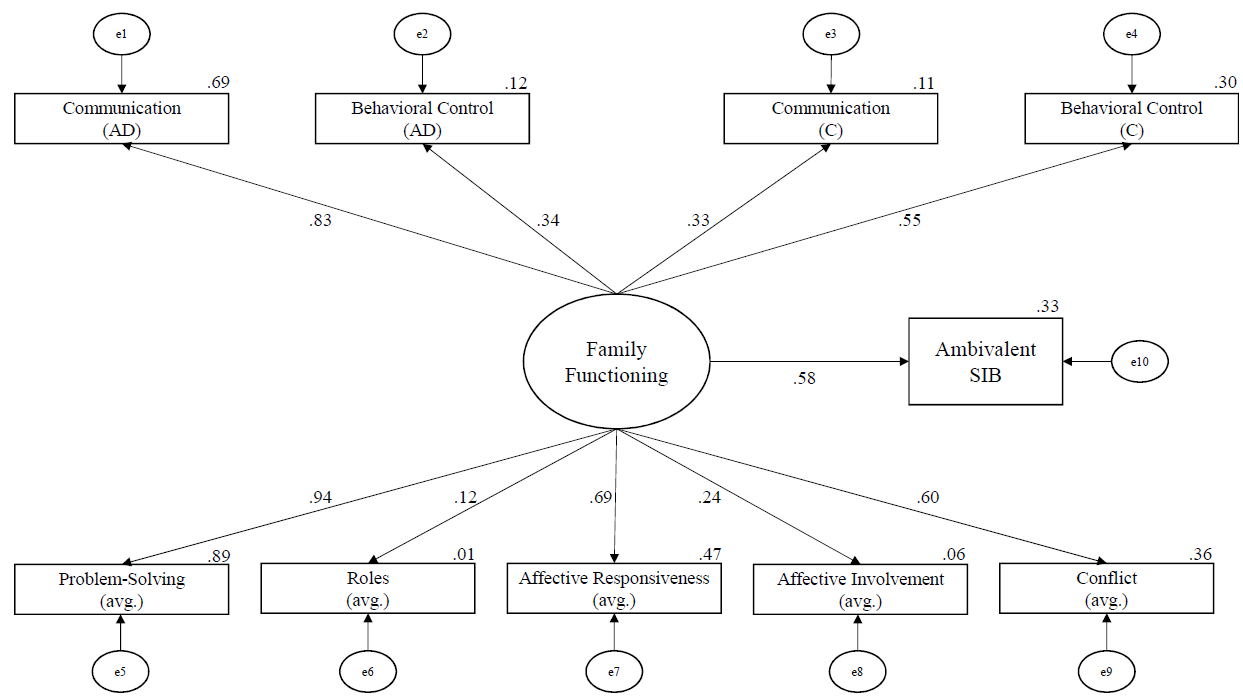

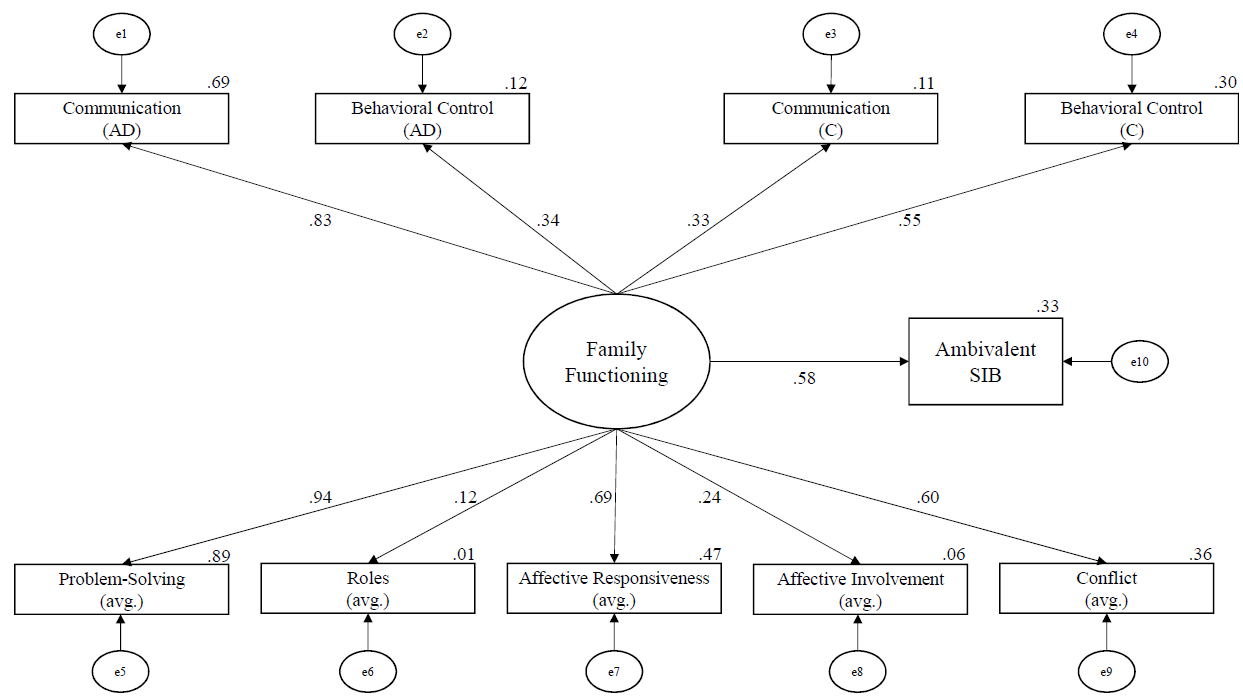

The model predicting ambivalent SIB had good absolute fit: χ²(7) = 5.69, p = .577, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.04. In all, family functioning explains 33% of the variance in ambivalent SIB. See Figure 3 for the standardized path coefficients between family functioning variables, the latent variable of family functioning, and ambivalent SIB. Notably, family functioning predicted ambivalent SIB: β = .58, B = 1.04, SE B = 0.46, p = .025. Based on effect sizes (see Figure 3), the strongest predictors were problem-solving (averaged; β = .94, B = 0.15, SE B = 0.07, p = .022, R² = .89), communication (adolescent-reported; β = .83, B = 0.11, SE B = 0.05, p = .030, R² = .69), and affective responsiveness (averaged; β = .69, B = 0.13, SE B = 0.07, p = .049, R² = .47).

Figure 2

The Output Structural Regression Model of Nonsuicidal SIB Developed Using SEM

Note. The numbers on paths are the standardized path coefficients, and the offset values on endogenous variables are the R2 effect sizes. (AD) = adolescent report; (C) = caregiver report; (avg.) = averaged score of adolescent and caregiver report.

Figure 3

The Output Structural Regression Model of Ambivalent SIB Developed Using SEM

Note. The numbers on paths are the standardized path coefficients, and the offset values on endogenous variables are the R² effect sizes. (AD) = adolescent report; (C) = caregiver report; (avg.) = averaged score of adolescent and caregiver report.

Lastly, the model using family functioning to predict suicidal SIB was not able to successfully converge because of reaching the iteration limit, possibly because of the small sample size. After examining the suggested modification indices, the model was still not able to converge. Thus, we concluded that the suicidal SIB model was a poor model, meaning that family functioning alone was not predictive of suicidal SIB in our sample.

Discussion

The goals of the current study were to examine the family environment of adolescents seeking treatment for symptoms of BPD, as well as their experiences of SIB, and to better understand what aspects of family functioning relate to SIB. Unique strengths of this study include the emphasis on assessing models of family functioning as it relates to SIB and exploring differences between SIB intent types (suicidal SIB, nonsuicidal SIB, and SIB with ambivalence toward life). Further, because participants were clients seeking counseling from community-based master’s-level clinicians and no clients were excluded from participating in this study, results may generalize to other community samples.

We found that adolescents and caregivers often reported family functioning scores that met criteria for distressed families. Interestingly, adolescents and caregivers agreed on a majority of the subscales of family functioning, suggesting that the distress is mutually experienced. Adolescents and their caregivers only differed on reports of behavioral control (e.g., “[my family does not] hold any rules or standards”) and communication (e.g., “when someone [in my family] is upset the others know why”). This self-reported familial distress supports the social component of the biosocial theory (Linehan, 1993) in that the adolescents with traits of BPD engaged in SIB and experienced unhealthy family environments. Additionally, we found high lifetime rates of SIB in our sample of adolescents. As in previous studies (e.g., Anestis et al., 2015), adolescents in the current study engaged in nonsuicidal SIB more frequently than suicidal or ambivalent SIB, and cutting was the most common method.

Notably, our model of family functioning successfully predicted higher levels of both nonsuicidal SIB and ambivalent SIB. In particular, problem-solving, conflict, and adolescent-reported communication had consistently large effect sizes, suggesting that these subscales contributed more to SIB than other subscales. Although no previous studies have examined adolescent SIB and familial problem-solving to our knowledge, the findings that SIB was related to familial conflict (Huang et al., 2017) and communication (Halstead et al., 2014) corroborate the results of previous studies.

The success of the family functioning model in predicting SIB aligns with family systems theory. Specifically, adolescents in our sample may engage in SIB as a coping skill because their family lacks healthy problem-solving skills and thus models poor coping (which aligns with a description by Halstead et al., 2014). Additionally, adolescent SIB may function to temporarily end conflict in the family because it diverts the family’s attention away from the immediate problems. For example, Oldershaw et al. (2008) found that parents avoided conflict and felt like they were “walking on eggshells” (p. 142) after learning of their adolescents’ SIB. Another possible explanation is that the adolescents in our sample may serve as scapegoats within their family, acting as a focal point of a disturbed family system. From a structural family systems perspective, when there are problems within family subsystem relationships, oftentimes the child—typically the most vulnerable one—becomes the focus of the family’s problems (Wetchler, 2003); this trend is consistent with our findings.

It is worth noting that family functioning alone did not sufficiently predict suicidal SIB. One possible explanation is that our family functioning variables did not encompass the factors of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, both of which Joiner (2005) suggested may lead to suicide.

Limitations and Future Directions

A strength of this study is that the results may generalize to other real-world settings in which adolescent clients seek counseling services from community-based master’s-level clinicians who specialize in dialectical behavior therapy. However, this ecological validity comes with some relative limitations.

One notable limitation of this study is that we examined family functioning at one point in time, when the adolescent was beginning treatment. Given this single timepoint, we are unable to fully describe the relationship between family functioning and SIB. Considering the biosocial theory, it seems likely that the distressed family environment preceded the SIB; however, it is possible that the SIB caused greater familial distress. Therefore, it would be useful to assess changes in family functioning and SIB across time.

Another limitation is our SIB measure; as Crowell et al. (2013) explained, the LSASI is commonly used in clinical practice but not often in research. In addition to issues with reliability, the LSASI is a lifetime measure as opposed to one focusing on recent behavior. Although all participants reported engaging in SIB in the past year, it is unclear how recently they engaged in SIB relative to the time of the study. Despite the benefit of creating more variability in the data by allowing participants to report their specific frequency of SIB, the alternative of a dichotomous variable of current SIB might be more compatible with our measures of current family functioning.

Additionally, the small sample size limits the power of our analyses as well as the generalizability of our results. A small sample increases the likelihood of a Type II error, meaning an increased likelihood of not finding significant results. However, it is notable that we found statistically significant results (e.g., good model fit of family functioning) despite our low power. Nevertheless, replication studies with much larger samples are needed.

Implications for Practice

Our findings suggest that family functioning is related to SIB in adolescents, particularly nonsuicidal and ambivalent SIB. Although counselors often include families when working with young children, it is common for counselors to work with adolescents individually. This practice is consistent with state laws allowing adolescents to consent to their own mental health treatment, and there are many presenting concerns and situations in which individual counseling may be the most effective modality. However, the connection between family functioning and SIB in adolescents in our sample indicates that it may be important to include family members in treating adolescent SIB; in fact, dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents (originally adapted by A. L. Miller et al., 1997) encourages family involvement in treatment. Counselors therefore need to educate parents and caregivers who may be reluctant to engage in the counseling process with their teen that SIB is an issue for which their participation in counseling could make a positive difference in treatment outcome. Further, from a family systems perspective, it can be challenging for teens to successfully use the coping skills and strategies they learn in counseling if the rest of the family system remains unchanged. Including at least some family members may therefore help adolescents maintain changes gained through the counseling process.

When including family members in counseling with adolescents who have engaged in nonsuicidal and ambivalent SIB, findings from our study suggest that three important targets for assessment and intervention include the domains of familial problem-solving, familial conflict, and adolescent-reported communication. Two of these, conflict and communication, were previously identified in the literature, and our study supports those findings. Our study newly identified familial problem-solving as an additional important predictor of SIB in adolescents. Counselors must keep in mind, however, that these variables were not sufficient in predicting suicidal SIB in adolescents. For these teens, we encourage the use of a broader assessment that includes elements of Joiner et al.’s (2009) interpersonal theory of suicide, especially the crucial interpersonal constructs of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.

Conclusion

Based on our findings, it appears there is a relationship between engagement in SIB (especially nonsuicidal and ambivalent SIB) and familial environment for community-based treatment-seeking adolescents with traits of BPD. Additionally, both adolescents and their caregivers in our sample reported distressed levels of multiple indicators of family functioning, suggesting the need for family-based intervention. Counselors and service providers should consider multiple markers of family environment (particularly problem-solving, conflict, and adolescent-reported communication) when assessing risk for and treatment of adolescent SIB.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

This study was partially funded by a grant from

Western Washington University awarded to

Dr. Christina Byrne. The authors reported no

conflict of interest for the development of this manuscript.

References

Adrian, M., Zeman, J., Erdley, C., Lisa, L., & Sim, L. (2011). Emotional dysregulation and interpersonal

difficulties as risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Child

Psychology, 39(3), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9465-3

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Anestis, M. D., Khazem, L. R., & Law, K. C. (2015). How many times and how many ways: The impact of number of nonsuicidal self-injury methods on the relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury frequency and suicidal behavior. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 45(2), 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12120

Chanen, A. M., Jovev, M., & Jackson, H. J. (2007). Adaptive functioning and psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68(2), 297–306.

http://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v68n0217

Crowell, S. E., Baucom, B. R., McCauley, E., Potapova, N. V., Fitelson, M., Barth, H., Smith, C. J., & Beauchaine, T. P. (2013). Mechanisms of contextual risk for adolescent self-injury: Invalidation and conflict escalation in mother–child interactions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(4), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.785360

Crowell, S. E., Beauchaine, T. P., & Linehan, M. M. (2009). A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending Linehan’s theory. Psychological Bulletin, 135(3), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015616

Epstein, N. B., Baldwin, L. M., & Bishop, D. S. (1983). The McMaster Family Assessment Device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 9(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1983.tb01497.x

Goldenberg, H., & Goldenberg, I. (2013). Family therapy: An overview (8th ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Halstead, R. O., Pavkov, T. W., Hecker, L. L., & Seliner, M. M. (2014). Family dynamics and self-injury behaviors: A correlation analysis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 40(2), 246–259.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00336.x

Hamza, C. A., Willoughby, T., & Heffer, T. (2015). Impulsivity and nonsuicidal self-injury: A review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.010

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

Huang, Y.-H., Liu, H.-C., Sun, F.-J., Tsai, F.-J., Huang, K.-Y., Chen, T.-C., Huang, Y.-P., & Liu, S.-I. (2017). Relationship between predictors of incident deliberate self-harm and suicide attempts among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(5), 612–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.005

Iacobucci, D. (2010). Structural equations modeling: Fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(1), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2009.09.003

Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press.

Joiner, T. E., Jr., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., & Rudd, M. D. (2009). The interpersonal theory of suicide: Guidance for working with suicidal clients. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11869-000

Kaess, M., Brunner, R., & Chanen, A. (2014). Borderline personality disorder in adolescence. Pediatrics, 134(4), 782–793. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3677

Latina, D., Giannotta, F., & Rabaglietti, E. (2015). Do friends’ co-rumination and communication with parents prevent depressed adolescents from self-harm? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 41, 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2015.10.001

Levenkron, S. (1998). Cutting: Understanding and overcoming self-mutilation. W. W. Norton.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford.

Linehan, M. M., & Comtois, K. A. (1996). Lifetime parasuicide count. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Miller, A. L., Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Jacobson, C. M. (2008). Fact or fiction: Diagnosing borderline personality disorder in adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 969–981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.004

Miller, A. L., Rathus, J. H., Linehan, M. M., Wetzler, S., & Leigh, E. (1997). Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, 3(2), 78–86.

Miller, I. W., Epstein, N. B., Bishop, D. S., & Keitner, G. I. (1985). The McMaster Family Assessment Device: Reliability and validity. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 11(4), 345–356.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1985.tb00028.x

Miller, I. W., Ryan, C. E., Keitner, G. I., Bishop, D. S., & Epstein, N. B. (2000). The McMaster approach to families: Theory, assessment, treatment and research. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 168–189.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00145

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 885–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2005). Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1), 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.140

Oldershaw, A., Richards, C., Simic, M., & Schmidt, U. (2008). Parents’ perspectives on adolescent self-harm: Qualitative study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 193(2), 140–144. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045930

Prinz, R. J., Foster, S. L., Kent, R. N., & O’Leary, K. D. (1979). Multivariate assessment of conflict in distressed and nondistressed mother–adolescent dyads. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 12(4), 691–700.

https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1979.12-691

Rallis, B. A., Esposito-Smythers, C., & Mehlenbeck, R. (2015). Family environment as a moderator of the association between conduct disorder and suicidality. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 24(2), 150–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2015.997909

Robin, A. L., & Foster, S. L. (1989). Negotiating parent–adolescent conflict: A behavioral–family systems approach. Guilford.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Walker, K. L., Hirsch, J. K., Chang, E. C., & Jeglic, E. L. (2017). Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior in a diverse sample: The moderating role of social problem-solving ability. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(3), 471–484. https://doi.org./10.1007/s11469-017-9755-x

Wetchler, J. L. (2003). Structural family therapy. In L. L. Hecker & J. L. Wetchler (Eds.), An introduction to marriage

and family therapy (pp. 63–93). Haworth Clinical Practice Press.

Melissa Sitton, MS, is a doctoral student at Southern Methodist University. Tina Du Rocher Schudlich, PhD, MHP, is a professor at Western Washington University. Christina Byrne, PhD, is an associate professor at Western Washington University. Chase M. Ochrach, MS, is a doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Seneca E. A. Erwin, BS, is a doctoral student at the University of Northern Colorado. Correspondence may be addressed to Tina Du Rocher Schudlich, 516 High St., MS 9172, Bellingham, WA 98225, tina.schudlich@wwu.edu.

Aug 18, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 3

S Anandavalli, John J. S. Harrichand, Stacey Diane Arañez Litam

Amidst the global health crisis of COVID-19, international students’ safety and well-being is threatened by community- and policy-level animus. In addition to adjusting to a foreign culture, a series of draconian policies and communal hate crimes during the pandemic have placed international students in an especially vulnerable position. In this context, professional counselors must be well prepared to support this community. The authors describe the current sociopolitical events that have adversely impacted international students in the United States. Next, challenges to international students’ mental health are identified to aid counselors’ understanding of this community’s needs. Finally, recommendations grounded in critical feminist and bioecological approaches are offered to facilitate counselors’ clinical and advocacy work with international students.

Keywords: COVID-19, international students, critical feminist, bioecological, advocacy

COVID-19–related fears have resulted in social and political responses characterized by racial discrimination and xenophobia toward marginalized groups (Devakumar et al., 2020; Litam, 2020; Litam & Hipolito-Delgado, in press), including international students (Anandavalli, 2020; Zhai & Du, 2020). Rates of misleading media portrayals and xenophobic rhetoric substantially increased after President Trump referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus” on March 16, 2020, and have steadily risen across social media platforms (Lyu et al., 2020). Exposure to COVID-19–related racial discrimination has deleterious effects on the mental health and life satisfaction of racial minorities (Litam, 2020; Litam & Oh, in press; Wen et al., 2020), including international students residing in the United States (Zhai & Du, 2020). The extant body of literature has clearly established lower levels of help seeking, barriers to counseling, and increased rates of mental health distress among international students compared to their domestic counterparts (Auerbach et al., 2018; Clough et al., 2018; Sawir et al., 2008; Zhai & Du, 2020). These existing challenges and psychosocial stressors may uniquely combine with current sociopolitical messages and policies to further exacerbate the unique developmental and cultural stressors encountered by international students. Thus, counselors working in various roles (e.g., college counselors, private practitioners) are called to develop a deeper understanding of the ways in which international students are negatively affected by xenophobic policies following COVID-19 and to employ culturally sensitive strategies grounded in systems approaches.

Although all counselors working with international students must consider the impact of larger systemic issues on international students’ mental health, college counselors might be in a unique position to support this population because of their close proximity. Counselors must consider how the combined effects of sociopolitical influences, systemic inequity, intersectionality, and COVID-19–related experiences of xenophobia uniquely contribute to the mental health disparities of international students in a post-pandemic reality. It is vital that counselors consider the impact of social and political structures, as Anandavalli (2020) found that contextual and systemic influences (e.g., elections, travel bans, anti-immigrant sentiment) have a profound impact on international students’ mental health. Unfortunately, despite repeated calls to action, counselors may be unprepared to support international students in the United States (e.g., Kim et al., 2019). Even years after Yoon and Portman’s (2004) critique, accredited counseling programs continue to offer little to no training to students to work effectively with international students. Perhaps as a result of years of limited training and research on international students’ mental health experiences, counselors continue to have inadequate cultural competence when working with international students. In a recent study, Liu et al. (2020) noted that although Korean and Chinese international students in their study had a cautiously optimistic attitude toward their college counselors, a third of them felt hurt and disappointed by their college counselors’ cultural incompetence and reported incidents of counselors’ cultural ignorance and stereotyping. With limited attention to social justice and equity issues, counselors can further traumatize and alienate some international students (Jones et al., 2017).

Within the counseling literature, even the few studies that explored the mental health of international students from a relational and systemic perspective (e.g., Lértora & Croffie, 2020; Page et al., 2019) have failed to adopt a critical lens and examine the impact and accountability of larger social institutions on the community’s well-being. At present, a review on PsycINFO, Google Scholar, and SocINDEX using the search terms international student mental health, international students counseling bioecological model, and international students multicultural critical race theory yielded no counseling literature that addressed strategies to support the mental health of international students in the United States from a critical perspective. Thus, the following article contributes to the extant body of literature on the topic by (a) describing the ways in which current sociopolitical events and policies send denigrating messages that devalue international students, (b) outlining the mental health challenges of international students, and (c) offering specific suggestions for counselors working with this vulnerable population through a critical feminist and bioecological lens.

Sociopolitical Policies Affecting International Students

According to the Institute of International Education (IIE; 2019), as the most popular study abroad destination, the United States hosts more than 1 million international (foreign-born) students. However, in the context of the racialized COVID-19 pandemic, Chirikov and Soria (2020) found that as many as 17% of the surveyed international students have experienced xenophobic actions that threaten their safety and presence. Further, they found these rates were higher among students from East Asian and Southeast Asian countries such as Japan, China, and Vietnam (22%–30%), given increasing Sinophobia (anti-Chinese sentiment) in the country. In addition to pursuing higher education, each year thousands of international students seek post-education professional experiences to receive practical training through an H-1B visa. An H-1B visa authorizes international students and professionals to work in the United States because of their experience in specialty occupations of distinguished merit and ability (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.). On June 22, 2020, H-1B visa holders were notified that effective June 24, 2020, the U.S. embassy would not be issuing new H-1B visa stamps; additionally, the ruling dictated that without a valid H-1B visa stamp, individuals could not enter the United States until December 31, 2020 (The White House, 2020). This xenophobic proclamation left thousands of international professionals stranded and placed them at risk of losing their employment. The announcement to ban H-1B visa holders devalued international students and professionals in the United States and reminded international students of their fragile futures and conditional status.

The most recent incident in the upsurge of xenophobic sociopolitical messages negatively affecting international students was introduced by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on July 6, 2020. A few weeks prior to the fall 2020 semester, international students were informed that they would be deported to their home countries if they were enrolled in fully online programs (ICE, 2020). International students became tasked with an impossible decision to either prioritize their health or their education. Unlike domestic students, who could safely attend programs online, the proclamation required international students to attend in-person classes to remain in the country (ICE, 2020). Although the proclamation was later amended to allow international students to attend online courses without deportation (ICE, 2020), the disparaging messages toward international students could not be overlooked. The presence of a discriminatory order that forced international students to choose between their safety and educational training is reflective of larger anti-immigration sentiments that push many students toward an emotional breakdown (Garcini et al., 2020).

Mental Health Challenges for International Students

Although international students contributed about $45 billion to the U.S. economy and to the development of 450,000 new jobs in the United States in 2018–19 (National Association of Foreign Student Advisers [NAFSA], 2020), worldviews that position international students as harbingers of innovation, intellectual diversity, economic success, and a necessity for sustaining higher education institutions are uncommon within American society (Williams & Johnson, 2011). Sadly, experiences of hate crimes are so frequent that many international students perceive them as normal consequences of being an international person in the United States (Lee & Rice, 2007; Pottie-Sherman, 2018). According to George Mwangi et al. (2019), for many international students, universities are far from being spaces of inclusivity and openness. Often, they were described as sites of oppression and “Americanization.” Interviews with international students from Africa indicated that due to their intersecting identities as racial and cultural minorities, participants in the study endured constant messages and actions undermining their culture and knowledge. In fact, persistent incidents of prejudice and discrimination made the participants feel “crazy” (George Mwangi et al., 2019). Chronic exposure to xenophobia, discrimination, and anti-immigrant sentiments has been documented to have profound impacts on international students’ psychological well-being (Houshmand et al., 2014; Ong et al., 2013). As a result of multiple factors, including xenophobia, international students suffer from severe psychological symptoms. One example is a recent study by Dovchin (2020), who found that parochial attitudes toward non-native English speakers and embedded linguistic racism had “serious ‘psychological damages’” (p. 815) on the international students’ mental health. Notably, the impact of “ethnic accent bullying” (p. 815) on her international student participants included development of social anxiety symptoms and suicidal ideation. Given that many of the instances of linguistic racism were found within classrooms, it is imperative that college counselors consider the pervasive influence of systemic inequities on international students’ mental health.

Critical Feminist Perspectives

Critical feminist paradigms acknowledge the powerful role of systemic influences and focus on change at structural levels. These paradigms challenge larger social structures (e.g., national and institutional policies) and promote the pursuit of social justice through clinical practice and inquiry (Moradi & Grzanka, 2017; Mosley et al., 2020). Thus, critical feminist paradigms are grounded in the philosophy that current social landscapes are inequitable and therefore unjust (Bonilla-Silva, 2013). Specifically, the critical feminist theory of intersectionality describes how systems of oppression and the social constructions of race, socioeconomic class, gender, and other identities interact in ways that influence one’s social positioning (Crenshaw, 1989). Given many international students’ intersecting identities as linguistic, racial, and ethnic minorities, counselors must consider how their unique combination of marginalized and privileged identities contribute to their social position and worldview as outlined in the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC; Ratts et al., 2015). Consistent with the focus on addressing the pervasive role of sociopolitical systemic influences, the analysis and recommendations offered in this article are grounded in the critical feminist paradigm.

Bioecological Systems Theory

Oppression and change occur across multiple levels of human interactions, and each level may require varied strategies for advocacy on the part of the counselor (Ratts et al., 2015). These interactions range from everyday occurrences in one’s immediate surroundings (e.g., classrooms) to international policies (e.g., travel bans). To address the powerful influence of multiple systems on the mental health of international students, a critical feminist paradigm was applied to Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) bioecological systems theory. The bioecological systems theory outlines how systems and environment interact with an individual in ways that impact their overall well-being. According to the model (Bronfenbrenner, 1994), individuals experience a bidirectional relationship (directly and indirectly) as a result of interacting with environmental systems where the impact of the relationship is dependent on the amount of interaction taking place. The bioecological theory is represented by five concentric circles that expand to represent multiple levels of permeable systems that affect one’s development (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). The systems within Bronfenbrenner’s model include: (a) microsystem, the immediate environment (e.g., family, school, peer group, neighborhood); (b), mesosytem, connections within the immediate environment, such as college campus and roommates; (c) exosystem, external environmental settings that only indirectly affect development, such as religious institutions outside of one’s faith; (d) macrosystem, which refers to one’s larger cultural context; and (e) chronosystem, encompassing patterns and transitions over the course of time and development (Bronfenbrenner, 1994).

Although the bioecological model represents a relatively robust theory, the model is not without its limitations. Christensen (2016) noted that the theory fails to account for the effects of globalization and technological developments that affect various parts of the world differently. These disparities can be addressed by combining the bioecological model with the critical feminist paradigm, which challenges institutions and structures that cut across national boundaries. Both models combine to create a unique framework that may guide concrete recommendations for counselors actively seeking to support and advocate for international students.

Implications for Counseling International Students

As the extant counseling literature on international students suffers from a limited emphasis on a critical feminist and bioecological lens, the current manuscript offers a systemic framework for counseling international students. We invite college counselors to adopt a critical feminist and systems perspective to hold larger systems accountable for their harmful role in international students’ mental health concerns (e.g., a university’s unwillingness to engage in culturally responsive and linguistically inclusive teaching strategies; Archer, 2007). The following counseling recommendations were developed from the authors’ direct experiences through counseling international students, and through a review of relevant literature. Although these recommendations may apply to all counselors irrespective of their settings, some may be specific to a particular role (e.g., college counselor).

Microsystem

The microsystem level includes the bidirectional relationships between the international student and the people with whom they regularly interact (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). College counselors and community counselors working with this population can support international students at the microsystem level by asking them to identify and deeply explore “safe” and “unsafe” relationships that exist within their college/university campus, neighborhood, and relevant religious group. Next, counselors can empower international students by framing their concerns as part of a larger systemic issue to minimize self-blame (i.e., seeing themselves as the cause of their challenges; Sue & Sue, 1990). Here, the focus is placed on empowering international students to engage in self-advocacy within the systems they occupy (Haskins & Singh, 2015). The reframe may also aid in enhancing the international student’s critical consciousness (Ratts, 2017; Ratts & Greenleaf, 2017) and help them shift their perspectives from self-blame to acknowledging the role(s) of external oppressive forces (e.g., racism, xenophobia, Sinophobia; Manzano et al., 2017). Indeed, engaging in the internalization of problems in response to stressors is prevalent among many international cultures (Wong et al., 2013).

Interventions at this level might involve the use of microinterventions (Sue et al., 2019) to empower international students. Sue et al. (2019) defined microinterventions as deeds and interactions that communicate affirmation and validation to targets of microaggressions. These interventions have the potential to enhance the psychological well-being and self-efficacy of the target and disarm the effects of microaggressions by challenging the perpetrator. Counselors can provide psychoeducation on microinterventions, using caution and clinical judgment to avoid further harm to the student. It is imperative that counselors recognize and educate the international student that it could be dangerous to employ microinterventions without understanding the specificities of the context. Sue et al. noted that the minoritized individual (target) employing microinterventions must be intentional about picking their battles, as endless responses to each encountered incident of microaggression can be damaging to the target’s well-being. The target should be aware of the context of the microaggression and modify their response as the situation requires. Given that racism and oppression permeate classroom spaces, college counselors can also provide opportunities for practicing microinterventions through role plays (Litam, 2020). One microintervention is making the “invisible” visible by responding to instances of racial discrimination on campus, making the offending party (e.g., domestic students, staff) aware of their offensive actions or words, and/or compelling them to consider their impact (Sue et al., 2019). Counselors may further guide international students in educating the offender (Sue et al., 2019). Litam (2020) noted that although it is of critical importance to avoid placing the onus of responsibility on minoritized individuals (e.g., international students) to educate and/or confront their offenders, when they do engage in thoughtful responses the opportunity to educate can result in positive changes and healthier relationships.

Finally, counselors can support international students to incorporate mindfulness and self-compassion as culturally sensitive tools to address the xenophobic experiences of COVID-19–related racial discrimination (Litam, 2020). Compassion meditation may help international students release their feelings of anger and intentionally cultivate experiences of self-compassion and positive regard toward self and others. Self-compassion may be cultivated by encouraging international students to attend to their immediate needs by remaining present and non-judgmental (Germer & Neff, 2015). Grounded in the Buddhist concept of loving-kindness, international students may be trained to pay attention to their somatic experiences with a non-judgmental curiosity. For instance, as these students confront chronic racism, they may benefit from opportunities to be kind to themselves. Counselors may also guide them to engage in mindful breathing to ground themselves in the face of chronic stress (Germer & Neff, 2015).

Additionally, empowering international students to cultivate a strong sense of ethnic identity may also represent an important strategy at this level. Extant research continues to identify the role of ethnic identity as a protective factor for experiences of racial discrimination (Carter et al., 2019; Chae & Foley, 2010; Choi et al., 2016; Tran & Sangalang, 2016), including experiences of COVID-19–related racial discrimination (Litam & Oh, in press).

Mesosystem

Counselors working with international students at the mesosystem level may continue to strengthen the interventions at the microsystem level while exploring mental health stressors that may arise through interactions between the student and their peers and/or members of the college/university campus community. Counselors who interact with various social groups uniquely position themselves in ways that establish new relationships, building support with spiritual and religious leaders (Sue et al., 2019) and mid- and senior-level administrators who are then able to directly or indirectly support international students on and off campus (Mac et al., 2019).

Leveraging their network within the university system, college counselors can explore how faculty members, administrators, and staff may improve their cultural humility and competence by collaborating with them in efforts to support international students within the campus (Hook et al., 2013). For instance, faculty members and staff could be invited to on-campus ethnic interest groups, cultural festivals, or language clubs on a regular basis to immerse themselves in their students’ cultural practices. Additionally, many international students on campus occupy shared housing. College counselors can teach international students’ roommates, peers, and resident advisors to detect signs of distress and isolation. This can potentially help student leaders and other residents better support international students and promote wellness in the student body more broadly. Engaging the community in culturally relevant strategies for promoting the mental health of international students and recognizing their distress may help college counselors in early detection of distress for this community.

Exosystem

The exosystem level examines social settings that indirectly impact the student but in which the student has no direct impacts (e.g., local politics, medical and social services; Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Interventions at the exosystem level might examine how educational training grounded in Eurocentrism may further marginalize international students and negatively impact their academic standing and their overall mental health and well-being (George Mwangi et al., 2019; Ploner & Nada, 2020). Counselors working with international students at the exosystem level must shift their perspectives from interpersonal interventions toward a greater examination of systemic influences. Counselors may utilize the MSJCC (Ratts et al., 2015) to consider the intersecting ways in which the privileged and oppressed identities of international students uniquely influence their mental health experiences. A detailed description of how counselors can apply the MSJCC to counseling international students can be found in Kim et al. (2019).

College counselors working at the exosystem level must play an active role in advocating on behalf of international students by working to dismantle White supremacy in college/university counseling settings (Ratts, 2017) and academic settings (Haskins & Singh, 2015). Furthermore, counselors working at the exosystem level are called to advocate for inclusive spaces and educational curricula that incorporate diversity of thought and pedagogical practices that cater to all student groups. Other examples of exosystem-level advocacy include involvement with academic units, institutions, organizations such as NAFSA and the American College Personnel Association, and communities that indirectly impact international students (Manzano et al., 2017). Trainings for educators and staff at colleges/universities about the importance of dismantling systemic racism and facilitating anti-oppressive pedagogy may also be provided (Berlak, 2004).

Furthermore, community counselors working with this population may collaborate with various social groups (e.g., host families) to develop antiracist approaches that address internalized racism and White supremacy (Kendi, 2019; Singh, 2019). These collaborations may also aid in facilitating the help-seeking behavior of international students and countering the embedded stigma against seeking mental health support (Liu et al., 2020).

Macrosystem

The macrosystem-level focus is on cultural norms, values, and laws that influence the international student without being directly influenced by the student (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). At this level, college counselors may collaborate with other health specialists (e.g., community mental health counselors, social workers, medical doctors) and explore how current U.S. political structures impact the mental health and well-being of international students. These alliances can help students as counselors engage in advocacy initiatives and tackle public policy on behalf of the student (Chan et al., 2019). For example, college counselors can engage in advocacy efforts similar to those that encouraged college and university administrators to oppose the ICE policy by President Trump that targeted international students.

In addition to seeking change to public policies that discriminate against international students, college counselors working at the macrosystem level can also advocate for equitable practices within college and university systems and promote an educational climate that celebrates international students on campuses. Forming alliances with stakeholders (e.g., administrators, legislators, legislative staff) who directly and indirectly impact cultural norms and values in society could also be a helpful strategy for counselors supporting international students at the macrosystem level (Mac et al., 2019). Similarly, community counselors can offer cultural sensitivity training programs to members of local government agencies (e.g., credit unions, DMV). Knowledge of how visa regulations and cultural norms operate can help state and national organizations better serve this population. Finally, platforms such as the National Association for College Admission Counseling and The Chronicle of Higher Education may offer unique spaces for collaboration among counselors, educators, and allies to advocate for this community.

Chronosystem

The chronosystem encompasses all other societal systems that directly and indirectly impact the international student over time (e.g., federal employment policies; Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Interventions at the chronosystem level could address how the transition from an international student to worker in the United States (e.g., H-1B visa–holding professional) impacts how they are perceived by American society. For example, counselors can design programs that identify and address the needs of international students based on past and current sociopolitical events (e.g., 9/11 attacks, COVID-19 pandemic). Furthermore, college counselors may consider how these sociopolitical events might lead to disparaging attitudes toward international students and actively work to facilitate workshops, webinars, or trainings that identify and dispel harmful notions. Both college and community counselors must critically consider how systems continue to evolve over time (Chan et al., 2019). Therefore, they need to be actively attuned to the needs of international students, stay abreast of the current events that affect them, and actively participate in professional advocacy efforts across various systemic levels (e.g., institutional, state, national) to continue supporting this vulnerable community.

Future Directions

Using the search terms listed earlier, we completed an extensive review of the counseling literature. A paucity of empirical research exists in the counseling profession on international students’ mental health needs and experiences from a critical and systemic perspective. Empirical data can help counselors discern which types of interventions are most effective for international students within the counseling setting across various systems. In this article, we highlight that because of racial, linguistic, gender, and other differences within the international student community, an intersectional approach to inquiry is necessary. For instance, the experiences of a White, German, male international student will be vastly different from the experiences of a Black, Ghanaian, female student. Thus, inquiry on the experiences of this community must be positioned in the intersectionality framework (Crenshaw, 1989). Limited access to critical scholarship on the mental health experiences of international students within the counseling setting puts counselors at risk for retraumatizing their minoritized clients (Jones et al., 2017) through potential use of microaggressions and stereotypes, as shared by participants in the study by Liu et al. (2020). Thus, a tutorial stance grounded in cultural humility (Hook et al., 2013) and openness may be needed to build a safe and meaningful therapeutic relationship (Gonzalez et al., 2020). Future inquiries may help practitioners develop training modules and culturally responsive resources to improve their counseling skills and advocacy work with international students.

Conclusion

This article outlines a critical feminist and bioecological systems approach to supporting international students who are at higher risk for mental health distress because of xenophobic policies, racial discrimination, and systemic barriers. Discriminatory attitudes and behaviors toward international students have heightened during the current COVID-19 pandemic. Amidst this burgeoning crisis, counselors practicing in all settings are called to consider how each of these factors uniquely contribute to the mental health and overall well-being of this vulnerable population. Future research is needed to establish specific interventions that are most effective in mitigating the effects of pandemic-related stressors on the mental health of international students. Counselors are called to engage in advocacy efforts that dismantle systems of oppression at various levels, including within the community, in university/college settings, and in state and federal policies.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Archer, L. (2007). Diversity, equality and higher education: A critical reflection on the ab/uses of equity

discourse within widening participation. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(5–6), 635–653.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510701595325

Anandavalli, S. (2020). Lived experiences of international graduate students of color and their cultural capital: A critical

perspective [Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro]. Dissertation

Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/

Anandavalli_uncg_0154D_12696.pdf

Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., Lee, S., Lochner, C., McLafferty, M., Nock, M. K., Petukhova, M. V., Pinder-Amaker, S., Rosellini, A. J., Sampson, N. A., Vilagut, G., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2018). Mental disorder comorbidity and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 28(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1752

Berlak, A. C. (2004). Confrontation and pedagogy: Cultural secrets, trauma, and emotion in antioppressive pedagogies. Counterpoints, 240, 123–144. www.jstor.org/stable/42978384

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2013). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America (4th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In International Encyclopedia of Education (Vol. 3, 2nd ed., pp. 37–43). Elsevier.

Carter, R. T., Johnson, V. E., Kirkinis, K., Roberson, K., Muchow, C., & Galgay, C. (2019). A meta-analytic review of racial discrimination: Relationships to health and culture. Race and Social Problems, 11, 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-018-9256-y

Chae, M. H., & Foley, P. F. (2010). Relationship of ethnic identity, acculturation, and psychological well-being among Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88(4), 466–476. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00047.x

Chan, C. D., DeDiego, A. C., & Band, M. P. (2019). Moving counselor educators to influential roles as advocates: An ecological systems approach to student-focused advocacy. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 6(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2018.1545614

Chirikov, I., & Soria, K. M. (2020). International students’ experiences and concerns during the pandemic. SERU Consortium, University of California – Berkeley and University of Minnesota. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1lZdc4dWiX9C_8o1vH-4H7XokIHoJ4yjjVNRv0vS3tBE/edit#headin

g=h.ivkygr983tef