Sep 1, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 2

Brandon Hunt, Genevieve Weber Gilmore

In an effort to ensure the efficacy of preparing emerging counselors in the field, CACREP standards require that by 2013 all core faculty at accredited universities have a doctorate in Counselor Education and Supervision. However, literature suggests that a disparity may exist in the preparation of counselor educators and the actual responsibilities of faculty members. As such, the present study investigated CACREP-accredited doctoral programs’ preparation of students to teach from the perspective of both students and program coordinators. Results support a didactic course in teaching and a co-teaching internship to help doctoral students learn to develop course materials, manage classroom behavior, and develop a teaching style and philosophy. Recommendations for effective counselor education training practices are provided.

Keywords: counselor education, faculty, CACREP, doctoral students, teaching

The field of counselor education continues to grow and with the rise in counseling programs there is an increased need for doctoral level counselor educators. In support of this need, the 2009 Council on Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) standards require that by 2013 all new core faculty have a doctorate in Counselor Education and Supervision (CES), since they are trained to teach, conduct research, and contribute service to the counseling profession (Sears & Davis, 2003). The training mission of CACREP-accredited CES doctoral programs meets the growing interest in reform for graduate education and the needs of a changing academy (Austin & Wulff, 2004).

An examination of the literature raises curiosity about the consistency between graduate preparation and the roles and responsibilities of faculty members. For example, faculty members spend more than half their time on teaching (Davis, Levitt, McGlothlin, & Hill, 2006; Golde & Dore, 2001), yet research is often the dominant focus of doctoral-level training. This leaves graduates better prepared for the role of researcher and less prepared for the role of teacher (Golde & Dore, 2001; Heppner & Johnston, 1994; Orr, Hall, & Hulse-Killacky, 2008). For example, Rogers, Gill-Wigal, Harrigan, and Abbey-Hines (1998) found that counseling faculty ranked experience in the area of teaching higher than publication experience in the faculty selection process. The focus on research in doctoral preparation appears contrary to what programs want in faculty—that is, well-rounded faculty who are prepared to teach, conduct research, and provide service to their institution, profession, and community.

According to Burke (2001), doctoral programs typically prepare students for careers at research institutions, and in doing so offer graduate fellowships, assistantships, and other training opportunities in research. This traditional model emphasizes research preparation while paying little attention to other faculty responsibilities like teaching (Rogers et al., 1998; Wulff, Austin, Nyquist, & Sprague, 2004). Consequently, many new faculty members lack didactic and hands-on training in teaching. Heppner (1994) supports this notion and found few graduate programs had systematic curricular experiences designed to prepare graduate students to teach, and those that did typically involved two to three days of seminar-based instruction that emphasized topics like grading and academic dishonesty. Without formal curricular experiences designed to train teachers, doctoral students who plan to enter a career in academia are too often not receiving training in the basic aspects of how to teach. As a result, new faculty are learning to teach during their first year while simultaneously adapting to a new professional environment, and in some cases developing a research agenda (Berberet, 2008; Burke, 2001).

A few studies that examined early experiences of new assistant professors have been identified in the literature. In a qualitative study by Magnuson, Black, and Lahman (2006), new assistant professors in counselor education were interviewed about their first three years as academicians. One participant described feeling “competent clinically,” but “completely ill prepared” for the role of counselor educator (p. 176). Wulff et al. (2004) investigated how graduate students’ experiences contributed to their development as educators and the types of training that most effectively prepared them for the professoriate. Their findings underscored a lack of “systematic feedback and mentoring” (Wulff et al., p. 62) in graduate students’ development as educators. Students reported their departments did not prepare them for the role of educator or provide feedback on their teaching skills. For students who did receive feedback, it was not “thorough or carefully designed to help them grow as teachers” (Wulff et al., p. 62). Consequently, participants relied on formal and informal feedback from students as well as their students’ grades to identify their most effective teaching strategies (Wulff et al.).

Doctoral students sometimes gain experience as teaching assistants (TA), yet these experiences may not adequately prepare them for the activities necessary for successful faculty careers. Although TA opportunities can help graduate students learn how to deliver a lecture and evaluate student work, these assistantships often serve as “mechanisms for financial aid and provide a labor pool of junior instructors for the university” (Golde & Dore, 2001, p. 25). According to Fagen and Suedkamp Wells (2004), “Teaching assistants are thrown into teaching environments in a sink-or-swim manner. No advice, preparation, or supervision is given” (p. 84). Therefore, one cannot assume that teaching assistantships are the answer to preparing doctoral students for the professoriate.

Without formal curriculum designed to train teachers, students who plan to enter a career in academia lack training in important aspects of teaching such as developing a teaching philosophy, incorporating information technology into the classroom, and creating inclusive classroom environments (Golde & Dore, 2001). This lack of training prevents aspiring faculty from truly understanding the art of teaching; that is, guiding students to new levels of understanding rather than standing in front of the room and lecturing (Wulff et al., 2004).

Researchers suggest that graduate students who experience progressively challenging teaching roles with faculty supervision benefit most from their graduate teaching experiences (Wulff et al., 2004), yet less than 50% of graduate students receive appropriate training before they enter the academy and they lack appropriate supervision to help enhance their teaching skills (Fagen & Suedkamp Wells, 2004). Accordingly, recommendations to graduate programs to provide greater opportunities for students to develop teaching skills have been proposed. One such opportunity is the teaching internship, which can help broaden the program emphasis beyond that of research to better prepare students for jobs in academia (Nerad, Aanerud, & Cerny, 2004).

According to Burke (2001), requiring a teaching internship for doctoral students can lead to a powerful climate change in academe that benefits graduate students, their doctoral programs, their institutions, and higher education as a whole. Burke contends that adding an elective or a required course in teaching is not enough. Rather, doctoral programs should provide students with varied teaching opportunities that become increasingly more demanding, require more responsibility, and allow for activities including but not limited to advisement and the development of a teaching philosophy (Wulff & Austin, 2004). It is important to note that adding a teaching internship is not intended to deemphasize the importance of research; rather, doctoral training for the professoriate should be strengthened to include emphasis on the most time-consuming activity of a professor—teaching.

Rationale for the Study

CACREP-accredited doctoral programs have responded to the growing interest in reform in graduate education by increasing their emphasis on training the next generation of faculty to teach. Zimpfer et al. (1997) reported that counselor education doctoral programs rated instructional and co-teaching activities as highly important student activities, yet a description of such teaching activities and an investigation of their effectiveness was not provided. According to CACREP Doctoral Standard III.B,

Doctoral students are required to complete doctoral-level counseling internships that total a minimum of 600 clock hours. The 600 hours include supervised experiences in counselor education and supervision (e.g., clinical practice, research, teaching). The internship includes most of the activities of a regularly employed professional in the setting. The 600 hours may be allocated at the discretion of the doctoral advisor and the student on the basis of experience and training. (CACREP, 2009, p. 54; emphasis added)

This standard, however, does not specifically describe or offer suggestions on how doctoral programs should train their students to teach or how a teaching internship should be developed and implemented. CACREP Standard II.B.2 also mandates students should be provided with opportunities to “develop collaborative relationships with program faculty in teaching, supervision, research, professional writing, and service to the profession and the public” (CACREP, 2009, p. 53l; emphasis added). Finally, as stated in the “Doctoral Learning Outcomes” section of the 2009 CACREP Standards, graduates should be knowledgeable about theory and methods related to teaching and they should have developed their own philosophy of teaching.

Our interest in this topic grew out of our experiences learning to teach at the graduate level. The first author learned to teach by co-teaching with a faculty member when she was a doctoral student, even though her program did not have a formal teaching internship. The faculty member then required doctoral advisees to complete a formal teaching internship until the time her program made the decision that all counselor education doctoral students were required to complete a didactic course on teaching as well as complete a teaching internship. The second author completed a didactic course as part of her doctoral program, and did her teaching internship with the first author. Our basic assumption going into the study was that completing a teaching internship is important in helping doctoral students become competent teachers. We discussed our assumptions and thoughts about the teaching experiences of CES students before and during the current study.

A review of the counseling literature uncovered no research related to how doctoral students in counselor education are being trained to teach in accordance with CACREP standards. Thus, CES students who plan to spend a significant portion of their academic careers teaching are not able to access information that describes how CES graduates are best prepared to teach, specifically what works and what does not work from the perspectives of faculty and other students. To address this gap in the literature, we conducted a preliminary study to answer the following research questions: (a) How are doctoral programs in counselor education training their CES students to teach? And, (b) What are the experiences of CES students who have completed a teaching internship?

Methodology

We used both quantitative and qualitative questions to answer the research questions. We collected descriptive data to investigate how counselor education programs are training CES students to teach and used general qualitative inquiry to learn about the teaching internship experiences of CES students. Our study was conducted in two phases. In Phase 1, we surveyed CES professors who were doctoral coordinators about the training their programs provide to doctoral students with regard to teaching. In Phase 2 we surveyed CES students who were completing or had recently completed their teaching internship. We could not find an appropriate survey for our study, so we developed questions for both phases of the study based on our review of the literature on teaching at the collegiate level.

For Phase 1 of the study, we sent email surveys to the doctoral coordinators for all CACREP-accredited CES programs. The survey, which included the language from CACREP (2009) Doctoral Standard III.B, consisted of the following questions: (a) How many doctoral students are accepted into your program each year? (b) What is the main focus of your program (i.e., train faculty, train researchers, train supervisors and practitioners)? (c) How does your program meet CACREP Doctoral Standard II.B? (d) Does your program offer or require a didactic teaching course? (e) Does your program offer or require a teaching internship? And, (f) What other opportunities does your program offer that allow doctoral students to gain teaching experience? At the time we collected data there were 44 CACREP accredited doctoral programs, and despite repeated contacts with program coordinators encouraging their participation, we received responses from only 16 doctoral coordinators (36% response rate).

For Phase 2, we sent email surveys containing open-ended questions to the ten doctoral coordinators who responded that their programs offered a teaching internship—not all programs offered a teaching internship—asking them to forward the survey to students currently completing or who had completed their teaching internship. Fourteen students responded and all questions were answered. The student survey noted we were looking specifically at the teaching internship experience, not teaching assistant experiences, and asked questions about (a) teaching experiences prior to the doctoral teaching internship, (b) what students appreciated most about the teaching internship, (c) what they found most and least helpful about the teaching internship, (d) if they had a separate didactic course related to teaching, what was most and least helpful about the course, (e) what would they have liked to have known before they started the teaching internship/co-teaching experience, and (f) how prepared they felt to teach independently after completing the teaching internship?

Results

CES program coordinators provided commentary on the status of the teaching internship at their institution (Phase 1), and doctoral students on their experiences with the teaching internship (Phase 2).

Phase 1: Program Coordinator Responses

Coordinators for the 16 programs noted they typically accepted six CES students a year. With regard to the main focus of the program (i.e., train faculty, train supervisors and practitioners, train researchers), 10 coordinators noted their program focused on training counselor education faculty, one program emphasized training of counselor education faculty as well as training of supervisors and practitioners, one program focused exclusively on training supervisors and practitioners, and four programs had an equal balance between all three areas.

With regard to how programs met the CACREP standard regarding teaching, the responses were varied with 15 of 16 participants responding to this question. Three coordinators noted their programs required no teaching experience as part of doctoral training. Of these, two noted that while their programs did not require a teaching experience most CES students co-taught a course with a faculty member. Nine coordinators said their students must complete a formal teaching internship, which typically entailed teaching a master’s level lecture course with a program faculty member. Of the programs that required a teaching internship, eight also required that students complete a didactic course on college teaching. Four coordinators noted they offered the course on teaching in their department, and four participants noted the required teaching course was offered outside of their department. When asked what other opportunities their programs offered for CES students to gain additional teaching experience, eight coordinators responded that their students had the opportunity to teach an undergraduate course independently, three programs provided opportunities for students to lead workshops, and two programs provided opportunities for CES students to teach master’s level courses independently.

Phase 2: Experiences of CES Student Respondents Who Completed the Teaching Internship

As noted, 14 doctoral students responded to Phase 2 of the study. They were asked to answer questions about their experiences prior to, during, and following their teaching internship. Eight respondents reported they had some level of teaching experience prior to their doctoral programs, which included teaching at the K–12, undergraduate, and master’s level. Following the principles of the constant comparative method of analysis (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), we reviewed and coded the responses to the remaining eight questions independently and placed them in categories. Then we met to discuss our independent categories until we came to consensus about the categories’ titles and meanings.

We took several steps to verify our findings. First, we used multiple participants as a form of data triangulation (Creswell, 2007; Patton 2002). Second, we analyzed the data independently and then together, which is a form of investigator triangulation (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Patton, 2002). We also revisited participant responses when necessary throughout the analysis process, which provided us with opportunities to remain aware of potential research biases as well as to support or refute our categories. Finally, we used “thick description” (i.e., quotes) from the participants to add detail to their experiences (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Based on our analysis, responses emerged in the following four categories: (a) most and least helpful aspects of the teaching internship, (b) most and least helpful aspects of the didactic course on teaching, (c) what students should know before starting their teaching internship, and (d) how prepared students felt to teach independently. Responses will be described in detail, including exemplary quotes from the participants.

Most and least helpful aspects of the teaching internship. According to one respondent, the teaching internship is an opportunity for doctoral students to observe, model, and collaborate with “trusted and experienced” professors in preparation for their careers as counselor educators. Of the 14 doctoral students who responded, only one person wrote that the teaching experience was not helpful. The remaining respondents appreciated the support and guidance provided by the professors with whom they taught, which according to one respondent helped guide the student through “the rough spots” and improved his/her teaching skills. One respondent wrote, “I appreciated working closely with my supervisor to ensure that I had the support necessary to do the job right.” Another respondent shared that support and guidance were received through “bouncing ideas and feelings off” professors and collaboration on curriculum development and leading class discussions.

Respondents also appreciated the autonomy fostered by co-instruction opportunities, which allowed them to “have control over what assignments were being given.” One respondent underscored the importance of co-creating course syllabi and being involved with “in-class demonstrations and mini-lectures.” The flexibility and freedom to generate course curriculum and relevant materials encouraged the development of teaching philosophies and styles, both of which are essential to effective pedagogy. Another respondent stated, “My professor allowed me to choose half of the lectures and create my own materials for the class. I felt a sense of independence and empowerment as a co-instructor.”

Weekly teaching internship meetings where doctoral students and a professor met either individually or in a group to discuss ideas and concerns related to the teaching internship were described as beneficial. Respondents appreciated sharing ideas and hearing “strengths and areas of improvement” with regard to their teaching competencies. One respondent noted “meeting with the instructor of record to co-plan for [class]… helped me to deal with different problems that arose…[as well as] having trust and confidence placed in my abilities and me.”

Having a sense of being supervised too closely by the faculty co-instructor, however, was described by a few respondents as unhelpful, as the presence of the professor “made it hard to establish rapport and authority with students.” Feelings of frustration arose for one respondent when students would bypass the doctoral student and go directly to the faculty member of record “when it came to issues of grades, or syllabus-dictated course requirements.”

Additionally, although the majority of respondents viewed professors as experienced and excellent role models, several observed faculty who “did not model successful teaching strategies” or did not have a mastery of the material. One respondent stated, “Having to meet in a tiered supervision group with a professor who did not understand the unique aspects of the school counseling setting was not helpful.”

The “hands-on” training approach of the teaching internship was described as a valuable component of the experience as it promoted doctoral students’ observation and participation in realistic roles and responsibilities of professors. One respondent indicated, “I really got to experience how much prep work goes into teaching.” Others noted the opportunity “to teach a variety of courses” and “interact with different students” helped strengthen their abilities to reach and teach “all types of thinkers.” Some participants reported, however, that they felt unprepared for the “hands-on” approach, and found a number of characteristics of the teaching internship unhelpful. For example, one respondent noted, “prior knowledge of the level of preparation needed to teach a subject would have been helpful.” Another respondent struggled with “not knowing the level of competence of the students ahead of time,” and a third respondent found it “challenging to teach some students who were very unengaged in the course.”

Most and least helpful aspects of the didactic teaching course. Most graduate student respondents found their didactic course on teaching helpful in preparing them to teach. In particular, the didactic course provided opportunities for doctoral students to develop syllabi, exams, and grading rubrics, as well as receive feedback from professors and classmates. One respondent wrote,

Every assignment and class meeting was valuable. Assignments included writing a syllabus from start to finish and revising it after receiving feedback, keeping a journal on relevant topics (philosophy of teaching and learning, dealing with problems from students or other situations, our own biases), writing a sample test utilizing different types of test items, sharing and critiquing a video of us teaching, and creating a teaching portfolio that includes our philosophy of teaching, the things we created, and how we would evaluate students and ourselves.

Another respondent stated that the course on teaching required that respondents read the text they would be teaching the semester prior to teaching. This assignment, as described by the respondent, was “helpful in developing and receiving feedback on a tentative syllabus and lesson plans.” Respondents also indicated they enjoyed the opportunity to interact with other doctoral students, allowing for the comparison of “experiences” and acquisition of “new ideas.” Overall, these didactic experiences increased respondents’ knowledge of the course content, and furthered the development of their basic teaching skills and overall teaching philosophies.

Although many respondents found the didactic component of the teaching internship helpful, a few respondents shared that the course overemphasized the development of lesson plans. One respondent noted, “it was least helpful to develop individual lesson plans when we would be co-teaching.” The respondent continued with this recommendation: “it would have been more useful to develop lesson plans with our co-instructor, instead of having to merge and blend them together the first day of class.” One respondent shared his dislike for the course’s lack of emphasis on actual teaching. Two other respondents described the quality of course materials and the course curriculum as not beneficial. One respondent noted, “…a lot of the course was review, and for the parts that were new, I think I could have just written a paper based on the book,” and a second respondent identified her readings for the course as unhelpful.

What students should know before starting their teaching internship. Respondents provided various suggestions to future students with regard to what they should know before beginning the teaching internship. Mentorship was described as an important area of support for graduate students in counselor education. For those students who can choose the professor with whom they will teach, one respondent underscored the importance of “choosing a professor whose style you value” rather than choosing a particular course only based on interest. Furthermore, it is beneficial to consider “which ‘profs’ were the best teachers” and to “try to incorporate the successful strategies employed by your favorite teachers.” This comment speaks to the importance of faculty modeling effective teaching strategies to teaching interns. Another respondent provided a suggestion that emphasized the value of supervision:

Use your mentor as a sounding board, especially if you have never taught before. Rarely will you be presented with an issue in your class with which your supervisor has not had prior experience. Pay attention to the way effective professors do business.

Structured supervision also was indicated as an important area of interest. For graduate students who might not have a formal teaching supervision experience in place, one respondent advised, “Find out with whom they can consult formally or informally. Do not try to teach in a vacuum, especially if they are new to teaching…form an informal peer supervision group or seek outside supervision from another knowledgeable source.”

In addition, classroom management also was identified as a practical area that graduate students should know before beginning their teaching internship. Responses included dealing with “student issues,” “classroom dynamics,” and engaging “the difficult-to-engage student.” A few respondents commented on the importance of understanding and using effective ways to interact with students. For example, one respondent stated, “make sure you pay attention to how people react to being challenged…or how people go about disagreeing…[since] not everyone responds to criticism or being challenged in the same way.” Another respondent underscored the value of having structure in the classroom, noting: “It is easier to be ruthlessly rigid and demanding at first and then loosen the reigns toward the end of the semester than it is to be lax in enforcing grading or class rules and then try to put the hammer down at the end of the semester.” This respondent also recommended that teaching interns “set the tone from the start” of the course.

Finally, a few respondents recommended doctoral students understand the time, dedication, and competence required to develop course materials and integrate technology into the curriculum. For example, one respondent suggested doctoral students should know the “most professional issues relevant to the course; how to develop a syllabus; and how to create assignments that truly measure knowledge gained by students.” One respondent proposed that doctoral students plan “to double their estimated time of preparation and to try to gain competence in the use of technology like ANGEL and WEBCT,” which are computerized course management systems.

How prepared students felt to teach independently. Overall, respondents described the teaching internship as an essential component in preparing them to teach independently. Emphasis was placed on the importance of didactic training and the co-teaching experience in addition to teaching assistantship opportunities. One respondent noted, “The teaching internship is so essential for counselor educators…and this means a structured course or practicum beyond just being a teaching assistant!” Co-teaching experiences allowed students to gain knowledge of course material as well as skills to manage the classroom, both of which were invaluable to their training. One respondent noted the value of having a didactic course and teaching internship as part of his training: “I believe that my internship alone did not 100% prepare me to teach independently. I think that internship, the class on college teaching and other co-teaching experiences TOGETHER have helped me feel prepared to teach.” After completing the teaching internship, one person indicated she was hired by her department as an instructor for a master’s level course, which helped her gain additional experience and earn extra income during her doctoral studies.

Discussion

Findings from Phase 1 of the study show the majority of faculty respondents, all from CACREP-accredited CES programs, focused on training doctoral students to become faculty with particular emphasis on teaching, research, and service. Given that the master’s degree is the professional-level degree in counselor education, it seems appropriate that doctoral programs focus on training future faculty to teach. The majority of participants noted they were providing some level of teaching opportunities to CES students even if it was not offered in a formalized and systematic way. Doctoral coordinators for three programs did not respond to this question, and three noted they did not require students to complete any kind of teaching experience despite teaching being noted as an important element of doctoral training in the CACREP standards. Nine programs required students to complete a formal teaching internship, typically co-teaching a master’s-level counseling course with a counselor education faculty member, and of those programs eight required students to complete a didactic course on teaching. Additional training experiences offered to CES students included teaching undergraduate or graduate courses independently and leading workshops.

As noted earlier, results from our analysis of the student responses (Phase 2 of the study) provided information on the most and least helpful aspects of the teaching internship and the didactic teaching course, as well as what students should know before starting their teaching internship. Mentorship, support and guidance from faculty and peers, and weekly supervision were helpful aspects of the teaching internship. Teaching supervision that was too intensive and working with weak role models of quality teaching were unhelpful aspects of the teaching internship. Although most respondents found the didactic teaching course to be helpful, a few respondents expressed concern over the heavy focus on developing lesson plans (when they were not teaching a course yet) and the lack of actual teaching experience in the course. As a result, respondents recommended that other students be selective about with whom students complete their teaching internship, focusing on the instructor rather than the course content; make full use of the supervision provided by the faculty mentor as well as peer support; learn good classroom management skills; and be aware of the amount of time and energy required to develop and teach a course. All these recommendations are made possible through a didactic teaching course coupled with hands-on teaching experience.

Students respondents also described how prepared they felt to teach independently. Overall, the teaching internship, beyond being a teaching assistant, was very important in helping them feel prepared to teach independently since respondents learned both how to present content and manage the classroom elements of teaching.

Findings from our study are contrary to Wulff et al. (2004) and Fagan and Suedkamp Wells (2004), who found that doctoral students who wanted to become faculty reported they did not receive adequate orientation, preparation, or training to enter the classroom as teachers. Although the comparative research examined experiences across many disciplines and was not primarily focused on counselors, it is the only literature that could be located relevant to the current topic. It appears that students enrolled in CES programs that include a teaching internship requirement, if not requiring both a didactic course and the internship, felt supported as they learned to teach and believed they were well prepared to teach independently. Wulff et al. also suggested that students engage in teaching experiences that are progressively more challenging, moving from some level of teaching observation or a didactic course to then co-teaching with faculty, and then teaching independently, which happened for a number of the doctoral participants in our CES study.

Our findings support Heppner’s (1994) assertion that providing graduate students (five psychology students in this case) with the opportunity to engage in a teaching practicum or internship experience significantly increased their knowledge about teaching as well as teaching self-efficacy. Participants in Heppner’s study stated that receiving feedback from faculty co-instructors and peers as well as sharing ideas with their peers was particularly helpful, which is similar to our findings.

Limitations and Implications

As with all research, this study has limitations. Because of the preliminary nature of the study and the relatively low response rate for Phase 1, it is not possible to generalize the findings to all CACREP-accredited CES programs or to all counselor education doctoral programs. In addition, our findings reflect research institutions that train counselor education doctoral students. Therefore, caution should be used in interpreting our findings. Limitations for Phase 2 could include some degree of researcher bias since the authors initially had a student-professor relationship and worked together in a teaching internship, but we took the steps described above to ensure trustworthiness and attend to potential biases.

Despite these limitations, there are several implications that arise from our findings. First, CES programs would benefit from developing a systematic process for training doctoral students to teach. Having a required process is not only important in terms of meeting the CACREP standards, but also has an important influence on how we train future generations of master’s-level counselors. This process could include having students complete a didactic course on teaching, preferably offered within the department, and either simultaneously and sequentially completing a co-teaching internship with a faculty member.

Based on the research and our findings, it seems most effective to have doctoral students select the faculty member with whom they want to co-teach and that they receive consistent supervision. Burke (2001) takes the process even further, recommending that doctoral students complete a year long teaching internship that would include teaching two courses a semester and being involved in departmental meetings where curricular issues are discussed, as well as advising students. For specifics on a model designed to meet the CACREP standards for training counselor education doctoral students on how to teach, see Orr et al. (2008), who developed the collaborative teaching teams (CTT) model to help CES students gain experience and increase their sense of competence in teaching.

During the teaching internship students should be provided with formal opportunities to interact with other doctoral students completing their teaching internship, preferably in a weekly group setting. Again, our findings and existing research support the idea that peer support and critique is as important, if not more important, to doctoral students as they learn to become effective and confident teachers. Respondents benefitted from seeing what their colleagues did in similar teaching situations and imagining how they might handle a challenge that a doctoral peer was facing.

Lastly, counselor education programs can help doctoral students broaden their definition of teaching to include community and conference presentations, workshops, and other public speaking opportunities where CES students can use their counseling and teaching skills to educate others. Teacher training also should include specific content about how to assess and handle classroom situations where students may have committed academic misconduct or may be impaired in some way and what campus resources exist to help faculty and students navigate these challenging situations, including how codes of ethics and university policies and procedures apply in the classroom.

As Heppner and Johnston (1994) stated, “the development of excellent teaching skills involves continuous learning, a lifelong process…Given the complexity of the skills required for outstanding teaching, it is surprising that most faculty members have not had formal training in teaching” (p. 492). By providing the same level of focus and attention to teaching in CES programs that we do to research, we can help future CES faculty increase their level of competence and self-efficacy as counselor educators, thus effecting positive change in the classrooms of counselor education master’s programs across the country where our graduates are hired to teach. Our provision of quality and comprehensive doctoral-level education also responds to the call for reform for graduate education, particularly in preparing future faculty members to meet the needs of a changing academy.

References

Berberet, J. (2008). Perceptions of early career faculty: Managing the transition from graduate school to the professorial career. New York: TIAA-CREF Institute. Retrieved from http://www.tiaa-crefinstitute.org/articles/92.html

Burke, J. C. (2001, October 5). Graduate schools should require internships for teaching. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/weekly/v48/i06/06b01601.htm

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2000). CACREP accreditation manual. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2009). CACREP accreditation manual. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Davis, T. E., Levitt, D. H., McGlothlin, J. M., & Hill, N. R. (2006). Perceived expectations related to promotion and tenure: A national survey of CACREP program liaisons. Counselor Education & Supervision, 46, 146–156.

Fagen, A. P., & Suedkamp Wells, K. M. (2004). The 2000 National Doctoral Program Survey. In D. H. Wulff & A. E. Austin, Paths to the professoriate: Strategies for enriching the preparation of future faculty (pp. 74–136). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Golde, C. M., & Dore, T. M. (2001). At cross purposes: What the experiences of doctoral students reveal about doctoral education. Philadelphia: A Report for The Pew Charitable Trusts. Retrieved from http://www.phd-survey.org

Heppner, M. J. (1994). An empirical investigation of the effects of a teaching practicum on prospective faculty. Journal of Counseling & Development, 72, 500–507.

Heppner, P. P., & Johnston, J. A. (1994). Peer consultation: Faculty and students working together to improve teaching. Journal of Counseling & Development, 72, 492–499.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Magnuson, S. Black, L., & Lahman, M. (2006). The 2000 cohort of new assistant professors of counselor education: Year 3. Counselor Education and Supervision, 45, 162–179.

Nerad, M., Aanerud, R., & Cerny, J. (2004). So you want to be a professor! Lessons from the PhDs–ten years later study. In D. H. Wulff, & A. E. Austin, Paths to the professoriate: Strategies for enriching the preparation of future faculty (pp. 137–158). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Orr, J. J., Hall, S. F., & Hulse-Killacky, D. (2008). A model for collaborative teaching teams in counseling education. Counselor Education & Supervision, 47, 146–163.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rogers, J. R., Gill-Wigal, J. A., Harrigan, M., & Abbey-Hines, L. (1998). Academic hiring policies and projections: A survey of CACREP- and APA-accredited counseling programs. Counselor Education & Supervision, 37, 166–177.

Wulff, D. H., & Austin, A. E. (2004). Paths to the professoriate: Strategies for enriching the preparation of future faculty. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Wulff, D. H., Austin, A. E., Nyquist, J. D., & Sprague, J. (2004). The development of graduate students as teaching scholars: A four year longitudinal study. In D. H. Wulff, & A. E. Austin, Paths to the professoriate: Strategies for enriching the preparation of future faculty (pp. 46–73). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Zimpfer, D. G., Cox, J. A., West, J. D. Bubenzer, D. L., & Brooks, D. K. (1997). An examination of counselor preparation doctoral programs. Counselor Education and Supervision, 36, 318–331.

Brandon Hunt, NCC, is a Professor at Counselor Education, Counseling Psychology, and Rehabilitation Services at Penn State University. Genevieve Weber Gilmore is an Assistant Professor of Counseling at Hofstra University. Correspondence can be addressed to Brandon Hunt, Penn State University, University Park, PA, 16802, bbh2@psu.edu.

Sep 1, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

Joel F. Diambra, Melinda M. Gibbons, Jeff L. Cochran, Shawn Spurgeon, Whitney L. Jarnagin, Porche’ Wynn

To inform and guide their practices, counselor educators would benefit from having a clearer picture of how the research literature and professional standards of the field correspond and contrast. To elucidate this relationship, researchers analyzed 538 Journal of Counseling and Development articles published from 1997–2006 for fit with the 2001 and 2009 eight core areas of Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP). The articles fell into three tiers delineated by year and based on the number of articles assigned to each core area. Human Growth and Development and Helping Relationships are the two core areas most frequently represented across the 10 year time span examined.

Keywords: professional standards, research literature, CACREP, NBCC, ACA, Human growth and development, helping relationships

There is an inherent symbiotic relationship that exists among related professional organizations. Within the counseling profession, there are a number of organizations or entities that coexist, support one another, encourage and challenge one another, disseminate information, and act as gatekeepers. These major counseling entities include the American Counseling Association (ACA), the National Board of Certified Counselors (NBCC), the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) and the Journal of Counseling and Development (JCD). These entities mutually influence each other by acting and reacting to needs, changes and research findings within the counseling profession.

Given the new CACREP 2009 standards, it is now time for counselor educators to review and possibly revamp their training programs to better reflect the current issues faced by those in the counseling field. Counselor educators will benefit from having a clearer picture of how our research literature and professional standards correspond and contrast to inform and guide our practices.

As the respective flagship journal and primary accrediting standards of the counseling field, the JCD and the CACREP standards are predominant guiding resources that reflect, communicate, and shape the values, interests, and work of counselor educators. As JCD is the journal for ACA, and as the National Counselor Examination is based on CACREP requirements, an obvious extension to include these entities occurs as well. These entities also influence each other. JCD and CACREP can be seen as leaders of an input loop in the counseling profession. JCD, as the flagship journal for the American Counseling Association (ACA), shapes counselors’, stakeholders’ and counselor educators’ views of the counseling field. Continuing the loop, every seven years CACREP engages in a review of its standards for counseling programs. This review includes invitations for input from all counselors and stakeholders (Bobby & Kandor, 1995). As the revised standards are enacted in CACREP and CACREP-modeled programs, the standards influence the education and licensing of counselors, which then influences the work, research, writing, and submissions to JCD from the counseling field over time; JCD article topics, content, and methodology loop again to inform counseling practitioners, students, and educators.

While the 2009 CACREP standards revisions are implemented into counseling programs, it seems an important time for counselor educators to reflect on and explore the profession’s flagship journal articles in relation to future CACREP standards and to discuss future counseling literature that will shape and inform directions for counselor educators and the counseling field. Calls for a strong professional counselor identity (CACREP, 2009; Gale & Austin, 2003; Goodyear, 1984; Hansen, 2003) and professional unity from a recent ACA President (Canfield, 2007) would also seem to indicate the need to reflect on and gain perspective from the trends and foci of our professional literature. The current study provides an analysis and discussion of the fit of JCD articles from 1997–2006 with the eight core areas in both the 2001 and adopted 2009 CACREP standards. We selected this 10-year span because the research project began in late 2007 and 2006 represented the last complete year of JCD articles at that time. We hope such an analysis will help illuminate areas for potential change in counselor education programs.

Professional Organizations and Publications in Counseling

American Counseling Association

With its roots as far back as 1952, ACA is the world’s largest association focused exclusively on representing professional counselors. As reflected on their website, “The ACA is dedicated to the growth and development of the counseling profession and those who are served” (ACA, 2010). Its mission is to enhance the quality of life in society and promote the development of professional counselors, advance the counseling profession, and use the profession and practice of counseling to promote respect for human dignity and diversity (ACA). ACA has 56 chartered branches in the U.S., Latin America and Europe and currently boasts 42,594 members. To communicate to its membership and inform the profession of contemporary issues and treatment modalities, ACA publishes an online website, numerous textbooks, Counseling Today (its monthly magazine) and JCD (its official journal).

Journal of Counseling and Development

In addition to being ACA’s primary journal, JCD appears to have grown to a significant readership, and this is particularly interesting considering that at least two-thirds of ACA members receive JCD as their only ACA journal. According to ACA (personal communication, Rae Ann Sites, December 20, 2007), the JCD Winter 2008 issue had a total print run circulation of 43,500 journals. Approximately 1,000 of these subscribers are institutional subscribers (i.e., college/university libraries). Therefore, it seems logical to assume the majority of subscribers are individual ACA members.

Members also have the option to join one or more of 17 divisions within ACA and many of these divisions publish their own journals. As of December 20, 2007, the cumulative membership in these 17 divisions was 16,279. At most, division membership could represent 37% of ACA members, but it is important to note that some ACA members join multiple divisions, thus exaggerating the 37% figure. Following ACA’s 1997 decision to allow ACA membership exclusive of a division membership and the 2004 decision to permit division separation from ACA, the American Mental Health Counseling Association (AMHCA) and American School Counseling Association (ASCA) announced independence from ACA and are no longer included in these 17 divisions. ACA data available from June 30, 2007, indicate 2,182 (approximately 5%) of ACA members who also were AMHCA members and 2,648 (approximately 6%) who also were ASCA members (personal communication, Jennifer Bauk, December 3, 2007). When compared to the total membership figures of these two professional counseling organizations (AMHCA, 5,860 [personal communication, Mark Hamilton, November 27, 2007]; ASCA, 23,021 [personal communication, Jennifer Bauk, December 3, 2007]), the percentage of AMHCA members who joined ACA was 37% and ASCA members 16%. From these data, it is apparent that JCD is circulated to a wide and diverse counselor audience. Therefore, we can assume that many graduates of our training programs will read only JCD as their professional journal to inform them of current issues and important research.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs

CACREP has evolved to be a significant influence on the counseling field. A brief recap highlights CACREP’s growing influence. Bobby and Kandor (1992) reported that 44 programs housed within 16 institutions were granted approval by CACREP’s Board of Directors at the Council’s first meeting in 1981. In 1992, 195 programs had gained accreditation (Bobby & Kandor); and in 2004, that number had risen to 434 (McGlothlin & Davis, 2004). Currently, CACREP has accredited 505 programs housed within 210 institutions across 48 states, the District of Columbia, and Canada. In addition, 117 programs are currently being considered for CACREP accreditation. This is evidence of CACREP becoming more wide spread and ingrained within the counseling profession (CACREP, 2007).

National Board for Certified Counselors

Developed in 1982, NBCC conducts a national certification program for professional counselors; it is one of two leading certification organizations for the counseling profession, the other being the Commission on Rehabilitation Counselor Certification (CRCC). Although initially created by ACA, NBCC operates as an independent body without direct connection to ACA. Currently, over 46,000 counselors hold the National Certified Counselor (NCC) credential (NBCC, n. d.). In 41 states (82%), NBCC’s National Counselor Examination (NCE) is used as part of the licensure process.

The NCE contains eight content and five work behavior areas. The eight content areas mirror those in CACREP’s core curriculum and include human growth and development, social and cultural foundations, helping relationships, group work, career and lifestyle development, appraisal, research and program evaluation, and professional orientation and ethics. The five work behavior areas include fundamentals of counseling, assessment and career, group, programmatic and clinical intervention, and professional practice (NBCC, n. d.). Given this consistent overlap in core components and the growing use of the NCE for state licensure requirements, it is apparent that NBCC, ACA, JCD, and CACREP are linked in their view of what effective counselors need to know.

Support for Professional Organizations in Counseling

CACREP, JCD and NBCC have been the focus of several empirical studies. Over the past 10 years, researchers have examined issues pertaining to CACREP standards including supervision (LaFountain & Baer, 1999), spirituality and religion (Burke, Hackney, Hudson, Maranti, Watts, & Epp, 1999), community counseling (Hershenson & Berger, 1999), and school counseling (Holcomb-McCoy, Bryan, & Rahill, 2002). Haight (1992) investigated the CACREP standards, focusing on the quality of the standards. In addition, researchers have explored CACREP standards’ relevance to counselor preparation (Vacc, 1992) and their perceived benefit for practitioners (McGlothlin & Davis, 2004). Although some researchers have challenged the standards, most reviews and discussions related to CACREP have been favorable (Schmidt, 1999).

Vacc (1992) investigated counselor educator perceptions of the 1988 standards relevance to the preparation of counselors. He found that respondents judged each of the eight CACREP core areas as crucial or important to counselor preparation. Percentages of perceived importance ranged from 91% to 100%, with Social and Cultural Competence perceived as least relevant and Group Development, Dynamics, and Counseling Theories perceived as most relevant. Based on these findings, Vacc concluded that the data provided evidence to support the validity of the standards.

McGlothlin and Davis (2004) investigated perceived benefits of the CACREP standards. They surveyed counselors to determine perceptions of the benefits of the 2001 core curriculum standards. The core curriculum standards were perceived as being beneficial overall. Ranked in order of perceived benefit (highest to lowest) were: Helping Relationships, Human Growth and Development, Social and Cultural Diversity, Group Work, Professional Identity, Assessment, Career Development, and Research and Program Evaluation. Both studies established credibility for CACREP’s eight core standards.

As noted earlier, NBCC provides the examination used for professional licensure in the U.S. (NBCC, n. d.). Support exists for NBCC due to its oversight of the NCE. Adams (2006) compared NBCC National Counselor Exam scores across CACREP and non-accredited programs. She found that graduates of CACREP-accredited programs scored significantly higher than those from non-accredited programs. Pistole and Roberts (2002) encourage licensure as a primary way to secure professional identity. Similarly, Calley and Hawley (2008) identified professional certification and licensure, along with membership in professional organizations such as ACA, as ways counselor educators help promote a professional counseling identity. Support for both NBCC and the NCE is evident and furthers counselor professional identity.

JCD publications can be seen as shaped by a number of forces and as evolving over time. For example, Weinrach (1987) argued that JCD had been fashioned by contributors’ articles and editors’ aims. Twelve years later Williams and Buboltz (1999) asserted that JCD publications were influenced by changes within society, evolving counselor and student needs, the teaching aims of professors, and most importantly by the research and practical topics that are popular during a historical period.

The content analysis by Williams and Buboltz (1999) of volumes 67–74 most closely resembles the aims of the current study. Their article analysis covered a nine-year span and cross-classified articles into 11 categories (e.g., Counselor Selection, Training and Evaluation, Personal Development and Adjustment, Technology and Media, and Special Groups) and sub-grouped articles by editorship. The purpose of their study was to identify possible topic changes and trends over time and JCD editors. Overall ranking of topics pertinent to the 8 core areas identified by CACREP included Individual, Group Counseling, and Consultation ranked first, Special Groups third, Vocational Development and Adjustment/ Career Counseling seventh, and Technology and Media tenth.

In this study, ACA is assumed to be represented by its flagship journal, JCD, while NBCC is represented by CACREP, as the NCE is based on CACREP accreditation standards. To date, no study has analyzed JCD article content by CACREP core areas. In addition, no study could be found that focused on the similarities and differences between what is required for appropriate training and licensure of counselors and what is represented in the flagship journal of the counseling profession. Therefore, the purpose of the current study is to provide that analysis and discussion for the consideration of counselor educators and the counseling field.

Method

Procedure

Using first the 2001 standards and later the 2009 revisions, two researchers used a qualitative content analysis method to sort articles into the eight CACREP core areas. The eight CACREP core areas included Professional Orientation and Ethical Practice; Social and Cultural Diversity; Human Growth and Development; Career Development; Helping Relationships; Group Work; Assessment; and Research and Program Evaluation. Researchers independently analyzed content by sorting articles by CACREP core area. As per classic content analysis procedures described by Ryan and Bernard (2000), researchers assumed that the eight 2001 CACREP core curricular experience areas were the pre-defined codes of interest. Because of the time span from which articles were analyzed (i.e., 1997–2006), the researchers determined that both an analysis of the 2001 and 2009 standards was appropriate given that the 2001 standards were adopted during this time period and analysis of the 2009 standards would provide insight as to how previous articles would fit into the future standards.

First, researchers independently analyzed the JCD articles using the 2001 standards. After independent analysis, the two researchers compared findings, identified matching results and noted findings on which they differed. A list was established identifying the articles on which the two researchers disagreed. The same two researchers independently reanalyzed these articles and then met to compare findings again. No comparisons were made between the first and second attempts in order to maintain the independence of the second analysis. After this second attempt, the researchers obtained a cross-rater reliability of .93 for the 2001 data. Of the remaining articles for which coding differed, 20 differed in coding for CACREP core area. These articles were equally distributed throughout the 10 years of JCD being analyzed and were not representative of a single time period or editor. These remaining articles were coded by a third researcher, once again independent of the first two analyses. The three coders then reviewed each article together and, through consensus, determined the best placement for each.

After completing analysis using the 2001 CACREP standards, the two researchers addressed the data using the 2009 CACREP standards. The researchers noted that the eight core CACREP area titles remained constant between 2001 and 2009. However, differences between the 2001 and 2009 standards included changes within the eight core areas. Changes typically included additions of specific counseling related practices into core areas. Within the Professional Orientation and Ethical Practice core, additions were made related to crisis management and counselor self-care. Under Social Cultural Diversity, counselor self-awareness, social justice, and cultural skill development were added. In the Human Growth and Development core, additions included the effects of crises on individuals and theories of resiliency. The Career Development core remained relatively unchanged. Helping Relationships added crisis response and wellness orientation. Group Work and Assessment core areas remained substantively unchanged while Research and Program Evaluation incorporated evaluative measures and ethics related to research (CACREP, 2009). One overall change appeared to be that culturally inclusive language was more represented across most of the core areas. With these changes in mind, the two researchers independently re-reviewed titles and abstracts of all articles for 2009 CACREP core area best fit.

Analysis

The total number of articles in the JCD 1997–2006 issues was 538, excluding minutes from ethics committees and calls for editorial board members. Researchers examined 479 out of the 538 possible articles. Fifty-nine articles (11%) were eliminated from coding including interviews of well-known counselors and reviews of other articles (typically found in the Trends section). These articles did not fit into the predetermined coding categories. In all cases, an attempt was made to select only one option per area. Coding was based on the core area which was most representative of describing the article. For the 2001 Standards, approximately 7% of the cases (35 of 479 articles), were impossible to fit into only one area, so two areas were selected for coding. Three additional articles needed two areas after being reanalyzed with the 2009 Standards. For example, some articles were equally about a client issue and how counselors could effectively address the issue. These articles were coded as representative of both the Human Growth and Development and Helping Relationships core areas. In the two cases that no CACREP core area was found to match the article, an ‘Other’ category was selected. This category was used only when both researchers found it impossible to connect the article to a CACREP area.

When analyzing JCD articles using the 2009 CACREP core areas, researchers identified 97 articles that required reanalysis. These 97 articles were fully analyzed again. Fifty-nine of the 97 articles remained unchanged from the original assigned coding. Three articles were changed from representing two core areas to just one core area. Six articles were changed from representing one core area to two core areas (included originally coded CACREP core area plus one additional CACREP core area). Twenty-nine articles were recoded to a new core area.

Results

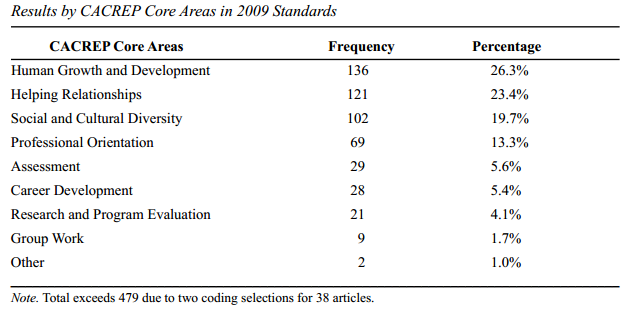

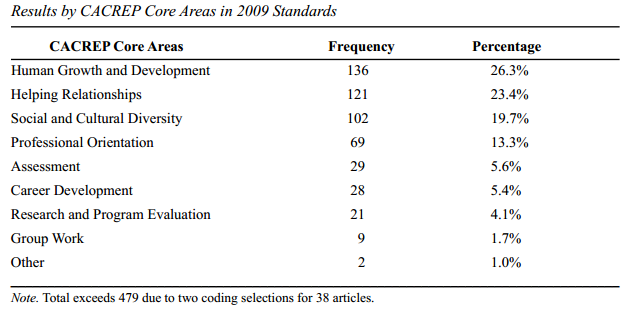

Due to the fact that only 29 (6%) of the 479 articles differed across core areas coding from the 2001 to 2009 CACREP standards, and because the proportional ranks remain the same, researchers are providing the 2009 CACREP Standards results, as 2009 is the current standard. CACREP core area results are presented in Table 1. The core area with the most articles was Human Growth and Development, followed by Helping Relationships and Social and Cultural Diversity. Group Work, Research and Program Evaluation, and Career Development were the least represented core areas. Thirty-eight of the articles were coded in two core areas, and all of the core areas were represented at least twice in a two-coded article. Seventeen of the two-coded articles involved Social and Cultural Diversity, 15 involved Helping Relationships, and 14 involved Human Growth and Development.

Table 1

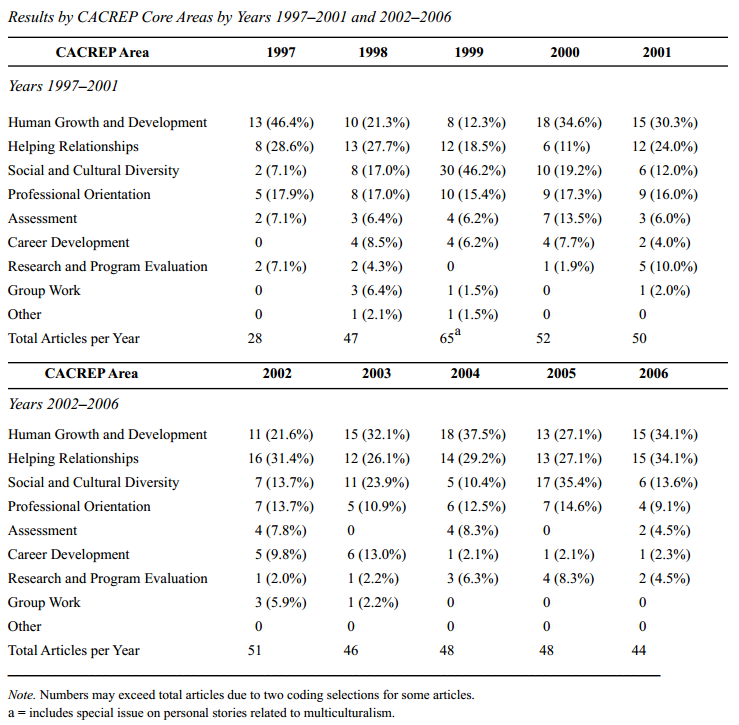

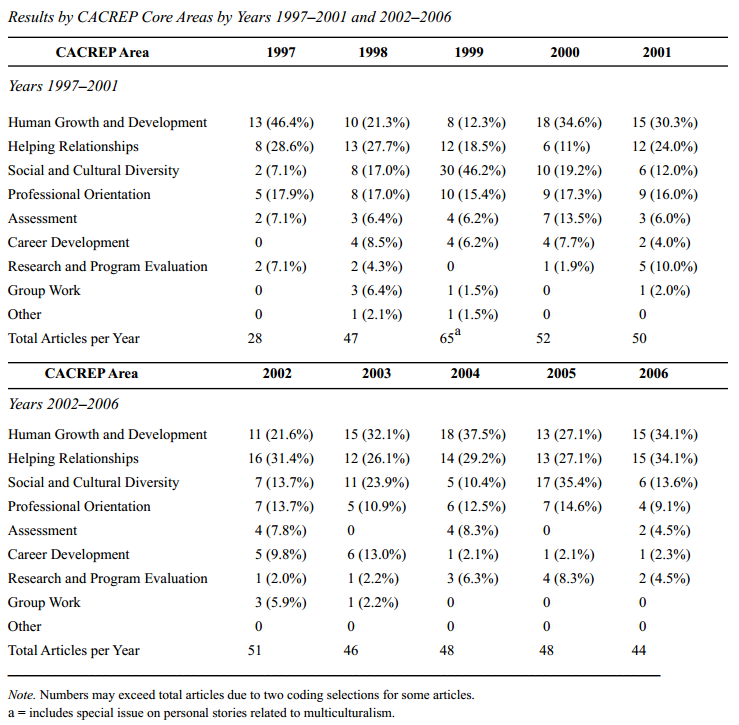

Rankings of core areas by percentage of articles tended to be stable throughout the 10-year focus period of this study. Human Growth and Development and Helping Relationships had the top two highest percentages of articles in the 10-year average and maintained consistently high percentages across the years, having been the first or second largest article category each year, except one. Within our analysis, these core areas formed the highest tier. Social and Cultural Diversity and Professional Orientation had the third and fourth highest percentages of articles and were ranked third or fourth each year (except one year for Professional Orientation and two years for Social and Cultural Diversity, affected by a special issue focused on that topic in 1999). Within our analysis, these core areas formed the middle tier. Assessment, Career Development, Research and Program Evaluation, and Group Work consistently varied from fourth to eighth in article percentages and formed the lowest tier of the rankings. These core areas not only occupied the lowest tier, but the percentages of articles representing them were noticeably lower than those representing the four leading core areas.

Table 2

Results by CACREP Core Areas across the ten year span are presented in Table 2. Over the 10-year period, most CACREP core areas are equivalently represented with minor fluctuations between years. Human Growth and Development and Helping Relationships are the two core areas most frequently represented and are reasonably consistent in percentage of articles representation from year to year across the 10 years. Human Growth and Development core area articles ranged in frequency from 8 to 19 across the years with a mean of 13.6 articles per year. Helping Relationships articles ranged from 6 to 16 with a mean of 12.1 articles published per year. Professional Orientation is the most consistent core area from year to year (range of 4 to 9 articles) with a moderate number (mean = 6.7) of articles published per year. Social and Cultural Diversity fluctuates substantially from year to year with a low of 2 articles published in 1997, a high of 30 articles in 1999 and a mean of 10.2 for all ten years. Assessment articles are relatively steady from year to year, yet low in number with a range from 0 to 7 articles each year and a mean of 2.9 articles per year. Research and Program Evaluation is similar to Assessment in low but steady frequency across the years with a range from 0 to 5 articles and a mean of 2.1 per year. Notably, Research and Program Evaluation articles increased slightly in the latter five years. Career Development is low in frequency, but less steady across the years with a range from 0 to 6 and mean of 2.8 articles per year. Notably, only 3 articles were published in this core area in the last three years of this study (i.e., 2004–2006), one article each year. Lastly, Group Work article frequency ranged from 0 to 3 and the lowest average frequency at .9 per year. In the last three years no articles were published in the Group Work core area.

Discussion

Having established the symbiotic relationship between four central counselor entities (i.e., CACREP, ACA, NBCC and JCD), the researchers focused their review on the overlap between the required CACREP training core and the topics represented in the counseling profession’s flagship journal, JCD. We were primarily interested in relating the content of articles from 1997–2006 to the eight CACREP core areas. When we began our study, we made the assumption that JCD and CACREP served as informative tools for its members and that CACREP standards were an appropriate measure of adequate counselor training. JCD purports “to publish articles that inform practicing professional counselors with diverse populations in a variety of settings and that address issues related to counselor education and supervision, as represented by the membership of the American Counseling Association” (JCD, n.d.). Whereas many specialty journals highlight one specific aspect or one core area, JCD attempts to provide relevant information that cuts across all CACREP core areas. Additionally, CACREP reports being “dedicated to (1) encouraging and promoting the continuing development and improvement of preparation programs, and (2) preparing counseling and related professionals to provide service consistent with the ideal of optimal human development” (CACREP, n.d.). In the counseling flagship journal and accrediting body, a goal exists to prepare, train, and provide counselors with information necessary to good clinical practice. As stated earlier, JCD is the journal representing ACA, and NBCC bases the NCE on current CACREP standards.

The results highlight an overlap between the missions and goals of JCD and CACREP with a weighted emphasis in key CACREP core areas. Results in Table 1 indicate that almost 70% of the articles published during this time period fall under three CACREP areas: Human Growth and Development, Helping Relationships, and Social and Cultural Diversity. It seems sensible and fitting to us that JCD articles would emphasize these areas. Remley and Herlihy (2007) stated that one of the essential beliefs in the counseling profession is that problems individuals face in life are developmental in nature. JCD’s emphasis on Human Growth and Development aligns with CACREP’s view that counseling helps clients work toward optimal human development. Additionally, the focus on Helping Relationships in JCD seems appropriate given the preponderance of research and literature across time that support relationship variables as most important in predicting outcome in counseling (e.g., Bergin & Lambert, 1978; Cochran & Cochran, 2006, Krumboltz, Becker-Haver, & Burnett, 1979; Lambert & Okiishi; 1997; Lubersky et al.,1986; Norcross, 2002; & Wampold, 2001). Finally, the 2009 CACREP standards support both a broad definition of Social and Cultural Diversity as a core area and the more specific recommendation of incorporating this concept into every course. This change relates to the current belief that cultural issues are not separate from other aspects of counseling, but rather integrated into all counseling activities.

Results indicated subtle yet notable shifts in the literature focus from those in previous research studies. For example, when Vacc (1992) investigated counselor educator perceptions of the CACREP standards relevance to the preparation of counselors, he found Social and Cultural Competence perceived as least relevant while results of the current study indicate Social and Cultural Diversity as in the middle tier of topic occurrence in JCD from 1996–2007. This seems to reflect the increased emphasis given to Social and Cultural Diversity within the counseling field in the last 20 years. Additionally, Vacc found Group Development and Dynamics was perceived as one of the core areas considered most relevant by counselor educators. The current study indicates that JCD articles focused on Group Work ranked in the lowest tier of frequency of occurrence. This could indicate a shift in importance over time or incongruence between counselor educator perceived importance and the number of JCD articles published in core areas. Finally, whereas group counseling and vocational development were covered extensively in JCD in the mid-1980s and early 1990s (William & Buboltz, 1999), our findings demonstrated considerably less focus on these areas over the last 10 years. Clearly, some important shifts in the literature have occurred over the past 25 years.

We find it important to also note the match between the ranked frequencies of JCD articles within the CACREP core areas and the results of McGlothlin and Davis’ (2004) study of the core areas perceived benefits. McGlothlin and Davis’ survey results ranked counselors’ perceptions of the importance of the core areas in nearly the exact rank of article frequency in JCD by core area. This suggests an overall match between publication patterns of JCD and the valuing of CACREP core areas among counselors.

Implications for Counselor Educators and Practitioners

It is clear that the articles published in JCD follow many of the trends suggested by CACREP as training requirements for counselors. If, however, as the earlier statistics suggest, JCD is the only professional journal received by the majority of ACA members, it is important for practitioners to recognize that they may not regularly be receiving as much ongoing information in these core areas compared to others, especially if they are only receiving JCD. Career development is viewed as a central factor in the lives of most people (Betz & Corning, 1993). For counselors working with children and adolescents, career development is influenced by a multitude of factors, including perceived barriers and supports (Kenny, Blustein, Chaves, Grossman, & Gallagher, 2003), family background (Eccles, Vida, & Barber, 2004), and self-efficacy beliefs (Pinquart, Juang, & Silbereisan, 2003). In adults, career-related concerns are linked with traumatic experiences (Strauser, Lustig, Cogdal, & Uruk, 2006), relationship problems (Risch, Riley, & Lawler, 2003), and overall stress (Pinquart et al.). Clearly, most counselors will encounter a need to discuss career-related issues with their clients, yet findings suggest that counselors may not receive a robust and ongoing supply of contemporary theoretical or research-based treatment approaches on this topic in JCD.

In addition, many counselors have the opportunity to facilitate groups as a part of their work. Vacc’s (1992) finding that counselor educators perceived Group Development and Dynamics as one of the most relevant core areas to the preparation of counselors and McGlothlin and Davis’ (2004) finding that Group Work ranked fourth in perceived benefit of the CACREP standards suggests that Group Work may be of importance to current working counselors, even though it is not well represented in JCD. Continuing education through professional journals can be a way to keep counselors-in-training, practicing counselors, supervisors and counselor educators abreast of new research and ideas regarding career and groups. Counselor educators, as well as clinical supervisors and counseling practitioners, would benefit by realizing that supplemental journals are needed to ensure adequate information on group dynamics is reaching their students and supervisee’s or informing their counseling practice.

Research and Program Evaluation and Assessment also received less representation in JCD. Counselors-in-training often struggle with these subjects or report disliking the bland content of these courses (Stockton & Toth, 1997). In fact, Bauman (2004) surveyed school counselors and found only 49% agreed or strongly agreed that they felt prepared to critique research, and only 43% agreed or strongly agreed that they had the skills needed to complete a research project on their own. Currently, a call in the profession exists promoting practitioners to conduct research in the field (Kaffenberger, 2009; Niles, 2003; Whiston, 1996), but with these feelings about research and assessment, it is unlikely that many will do so. Practitioners need to look beyond JCD for professional development on becoming competent and self-assured researchers. Knowing that a single journal is not the best option for gaining research self-efficacy might push practitioners to seek help elsewhere, rather than simply continuing on without furthering their knowledge.

Counselor educators and students can benefit in general from the findings of this study. For example, when conducting literature reviews or submitting research manuscripts for review, results provide guidance as to which counseling-related topics are more frequently or less frequently addressed in JCD. Results help to inform counselor educators when to best use and recommend JCD as an initial resource or different journal when they or their students are investigating specific topics within CACREP core areas. Additionally, one could argue that results suggest a reason to join multiple professional counseling organizations such as ASCA or AMHCA, or join the smaller sub-interest groups (e.g., National Career Development Association and Association of Specialists in Group Work) when first joining ACA or renewing their ACA membership. Overall, having more information available on major sources of training and continuing education can only assist practitioners and educators in their roles.

Implications for Future Research

Although this study provides an analysis of JCD articles over a 10-year period, with CACREP guidelines, additional research in this area is needed. Several ideas for future research foci are provided as preliminary courses of action. Researchers could help to identify students’, counselor educators’ and working counselors’ perceptions as to the importance of some of the lesser represented areas, such as Career and Group. Additionally, perceptions from these same constituents on how JCD, ACA, NBCC, and/or CACREP shape their views of the counseling field seems to be worthy of investigation. More research focused on specific CACREP areas and articles from other journals (e.g., the types of articles that represent each CACREP area and the impact on continuing education and training of future counselors) would further illuminate the relationship between the accrediting body and the counseling journals in general. Regardless of the exact focus of future research, it is clear that there is a link between the counseling accrediting body and the flagship journal. Further research is needed into how JCD and other counseling journals, along with CACREP and NBCC, may have or will influence each other over time.

Conclusion

It is our hope that the findings of the present study will be included in the perpetual input loop linking ACA, NBCC, JCD, CACREP and the counseling profession. With CACREP’s 2009 accreditation standards being implemented, we believe now is a good time for the counseling profession to re-examine the roles of the major counseling entities’ relationships to each other. Continuing this discussion, especially focusing on CACREP and ACA, may help strengthen the unity of our profession and further cement our identity as professional counselors.

References

Adams, S. (2006). Does CACREP accreditation make a difference? A look at NCE results and answers. Journal of Professional Counseling, Practice, Theory, & Research, 33, 60–76.

Bauman, S. (2004). School counselors and research revisited. Professional School Counseling, 7, 141–151.

Bergin, A. E., & Lambert, M. J. (1978).The evaluation of therapeutic outcomes. In S.L. Garfield and A.E. Bergin (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (2nd ed.; pp. 139–189). New York, NY: John Wiley.

Betz, N. E., & Corning, A. F. (1993). The inseparability of ‘career’ and ‘personal’ counseling. Career Development Quarterly, 42, 137–142.

Bobby, C. L., & Kandor, J. R. (1992). Assessment of selected CACREP standards by accredited and non accredited programs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 70, 677–684.

Bobby, C. L., & Kandor, J. R. (1995). CACREP accreditation: Assessment and evaluation in the standards and process. ERIC digest. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED388884).

Burke, M. T., Hackney, H., Hudson, P., Maranti, J., Watts, G. A., & Epp, L. (1999). Spirituality, religion, and CACREP curriculum standards. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77, 251–257.

Calley, N. G., & Hawley, L. D. (2008). Professional identity of counselor educators. Clinical Supervisor, 27, 3–16. doi: 10.1080/07325220802221454

Canfield, B. S. (2007, October). Many uniting into one [President’s message]. Counseling Today, 6.

Cochran, J. L., & Cochran, N. H. (2006). The heart of counseling: A guide to developing therapeutic relationships. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.