Jul 1, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 3

Let us start with two important disclaimers. First, I will be identifying the many ways that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) system has been detrimental to psychotherapy and how the fifth edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) will make the current situation even worse. However, this does not mean that I consider DSM diagnosis irrelevant to psychotherapy and counseling, nor do I believe that psychotherapists and counselors should neglect learning about diagnosis. I do not trust therapists who focus their contact with the client exclusively around the DSM diagnosis. Hippocrates believed that it is more important to know the person who has the disease than the disease the person has. Nevertheless, I also do not trust therapists who are completely free-form, impressionistic and idiosyncratic in their approach to clients. DSM diagnosis is only a small part of what goes into therapy, but it is often a crucial part. We need to know what makes each person different and unique; on the other hand, we also need to group clients with similar problems as a way of choosing interventions and predicting the treatment course.

The second disclaimer relates to the proper roles of medication, psychotherapy and counseling. The DSM has promoted a reductionistic medicalization of mental illness that, in combination with misleading drug company marketing strategies, has created a strong bias toward treatment with medication and against treatment with psychotherapy and counseling. I am greatly disturbed by the resulting enormous overuse of psychotropic drugs among both adults and children, many of whom do not need psychotropic drugs and would do much better without them. However, we must be equally alert to the fact that many people who need medication do not receive it. Psychotherapists and counselors are important gatekeepers who should recognize when medication is needed and when it is not. It makes no sense to be for or against medicating clients. It is crucial that medication not be used carelessly, but also essential to realize that it is sometimes absolutely necessary.

I will offer a brief history. Before the publication of the DSM-III (APA) in 1980, psychiatric diagnosis was a subject of little interest or importance because it was unreliable and not particularly useful for treatment planning. The DSM-III marked a sudden and dramatic change—it made diagnosis a major focus of clinical attention and the starting point of all treatment guidelines. Its provision of clearly defined criteria allowed for reasonably reliable diagnosis and for targeting specific symptoms that became the focus of treatment. The DSM-III’s influence exceeded all expectations, in some ways useful, but also with a significant defect. The prevailing mental health approach before the DSM-III was the well-rounded biopsychosocial model. At that time, clinicians conceptualized symptoms as arising from the complex interplay of brain functioning, psychological factors, and familial and social contexts. Perhaps without intention, the DSM-III downgraded the psychological and social factors and promoted undue emphasis on the biological factors. The DSM-III was advertised as “atheoretical” and neutral, usable by practitioners of all professional orientations. To some small degree, this was true; yet the DSM-III’s emphasis on purely descriptive psychiatry strongly favored biological treatments over cognitive-behavioral treatments. This bias proved to be irrelevant and eventually destructive to family and psychodynamic therapies. The descriptive DSM-III method focused attention on surface symptoms in the individual and ignored both deeper psychological understanding and the social and familial contexts. Clinicians often adopted a symptom checklist approach to evaluation and forgot that a complete evaluation must account for psychological factors, social supports and stressors.

In addition to its considerable impact on the mental health profession, the DSM-III also significantly affected the pharmaceutical industry. Drug companies benefited greatly from the DSM-III approach, particularly since 1987 when Prozac established the template for promoting blockbuster psychiatric drugs. Pharma realized that the best way to sell pills is to promote disease-mongering. Their marketing campaign offers the misleading idea that mental disorders are underdiagnosed, easy to diagnose due to chemical imbalances in the brain and best treated with a pill. The marketing targeted psychiatrists first, then primary care physicians and, since 1997, the general public. In the United States and New Zealand, drug companies have successfully bullied the government into allowing direct advertising to consumers on television, in print and on the Internet. Use of medication has skyrocketed as a result of these billion-dollar marketing budgets, turning us into a pill-popping society. This increase in drug use is great for Pharma shareholders and executives, but often inappropriate for clients and terribly costly to the economy. More than $40 billion a year are spent on psychiatric drugs. Most of these (80%) are prescribed by primary care doctors with little training or interest in psychiatric diagnosis or treatment, while under strong pressure from patients and drug company representatives, and after only seven minutes of evaluation on average. During the last decade, many drug companies have received enormous fines (e.g., one fine was $3.3 billion) for illegal marketing practices, but they continue because the rewards are so great.

For mild to moderate psychiatric problems, psychotherapy and counseling are just as effective as medication, and their effects are much more enduring. Most people taking medication would probably have been better off had they received psychotherapy or counseling. Unfortunately, psychotherapy and counseling suffer from two great disadvantages in their competition with drug treatment. Drug companies are enormously profitable industrial giants with billion-dollar budgets to push their products. In contrast, the mental health field is more of a nickel-and-dime, mom-and-pop operation with absolutely no marketing punch. Insurance companies further tilt the playing field by consistently favoring medication management over psychotherapy and counseling based on the mistaken assumption that it will be cheaper. In fact, brief treatments are often much more cost-effective because their effects are lasting, whereas medication may be necessary for years or a lifetime.

The medicalization of mental illness has had a dire impact on our clients and our society. Twenty percent of the population regularly takes a psychiatric drug, many for problems of everyday life more amenable to watchful waiting or psychotherapy and counseling than to drug treatment. It is astounding that there are now more overdoses and deaths from prescription drugs than street drugs. The tremendous societal investment in psychiatric drugs also misallocates resources much better spent on terribly underfunded social investments. Would it not be better for children to have smaller classes and more gym periods than for so many of them to be on pills for ADHD?

In preparing the DSM-IV (APA, 1994), we attempted to hold the line against diagnostic inflation and the medicalization of normality; however, we failed. During the past 20 years, the United States has experienced fad epidemics of ADHD, autism and bipolar disorder. We were conservative in writing the DSM-IV, but failed to anticipate or prevent its careless misuse under external pressure, particularly drug company marketing and the requirement of a psychiatric diagnosis for clients to qualify for school services and disability benefits. The quick fix is to give a diagnosis, but often this does more harm than good in the long run. Inaccurate diagnoses are easy to give but hard to remove. Often they haunt the client for life with stigma, unnecessary treatments and reduced expectations. Making an accurate diagnosis requires really knowing one’s client, which may take weeks or even months. In uncertain situations, it is better to underdiagnose than overdiagnose a symptom pattern, and better to be safe than sorry.

The DSM-5 will considerably increase medicalization and may turn our current diagnostic inflation into hyperinflation. Overdiagnosis transforms normal grief into major depressive disorder, normal temper tantrums into disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, normal forgetfulness of old age into minor neurocognitive disorder, poor eating habits into binge eating disorder, and expectable worry about physical symptoms into somatic symptom disorder. It also further loosens the already far too slack criteria for attention deficit disorder and contains a completely confusing definition of autism. Experience teaches that whenever the diagnostic spigot is unrestricted, drug company revenues increase, and less funding is available to support psychotherapy and counseling visits.

The DSM is only one guide to diagnosis—it is not a bible or official manual of diagnosis. The DSM codes that clinicians routinely use for reimbursement are in fact all International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification (ICD-CM) codes that are available for free on the Internet. DSM-5 is one suggested way to arrive at an ICD-CM diagnosis, but it is not the only or best way. Other more reliable guides to psychiatric diagnosis are available. Therapists do not have to buy or use the DSM-5 unless they work for an institution that requires it.

Receiving a psychiatric diagnosis can be a turning point in a client’s life. An accurate diagnosis can lead to an effective treatment plan; an inaccurate diagnosis can lead to side effects, stigma, high costs, reduced opportunities and needless suffering. Severe and classic presentations require quick diagnosis and immediate intervention, usually including medication. Milder, equivocal presentations allow for and require a more cautious approach. Therefore, watchful waiting or brief counseling is usually best.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The author published two books that critically

review the DSM-5, titled Saving Normal and

Essentials of Psychiatric Diagnosis.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Apr 7, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 2

Elizabeth A. Prosek, Jessica M. Holm

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and TRICARE have approved professional counselors to work within the military system. Counselors need to be aware of potential ethical conflicts between counselor ethical guidelines and military protocol. This article examines confidentiality, multiple relationships and cultural competency, as well as ethical models to navigate potential dilemmas with veterans. The first model describes three approaches for navigating the ethical quandaries: military manual approach, stealth approach, and best interest approach. The second model describes 10-stages to follow when navigating ethical dilemmas. A case study is used for analysis.

Keywords: military, ethics, veterans, counselors, competency, confidentiality

The American Community Survey (ACS; U.S. Census Bureau, 2011) estimated that 21.5 million veterans live in the United States. A reported 1.6 million veterans served in the Gulf War operations that began post-9/11 in 2001 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Gulf War post-9/11 veterans served mainly in Iraq and Afghanistan, in operations including but not limited to Operations Enduring Freedom (OEF), Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and New Dawn (OND) (M. E. Otey, personal communication, October 23, 2012). Holder (2007) estimated that veterans represent 10% of the total U.S. population ages 17 years and older. Pre-9/11 data suggested that 11% of military service members utilized mental health services in the year 2000 (Garvey Wilson, Messer, & Hoge, 2009). In 2003, post-9/11 comparative data reported that 19% of veterans deployed to Iraq accessed mental health services within one year of return (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006). Recognizing the increased need for mental health assessment, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) mandated the Post-Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA) for all returning service members (Hoge et al., 2006). The PDHA is a brief three-page self-report screening of symptoms to include post-traumatic stress, depression, suicidal ideation and aggression (U.S. DOD, n.d.). The assessment also indicates service member self-report interest in accessing mental health services.

Military service members access mental health services for a variety of reasons. In a qualitative study of veterans who accessed services at a Veterans Affairs (VA) mental health clinic, 48% of participants reported seeking treatment because of relational problems, and 44% sought treatment because of anger and/or irritable mood (Snell & Tusaie, 2008). Veterans may also present with mental health symptoms related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and suicidal ideation (Hoge et al., 2006). Depression is considered a common risk factor of suicide among the general population, and veterans are additionally at risk due to combat exposure (Martin, Ghahramanlou-Holloway, Lou, & Tucciarone, 2009). The DOD (2012) confirmed that 165 active-duty Army service members committed suicide in 2011. Furthermore, researchers asserted that suicide caused service member deaths more often than combat (O’Gorman, 2012). Hoge et al. (2004) reported that veterans were most likely to access mental health services 3–4 months post-deployment. Unfortunately, researchers suggested that service members were hesitant to access mental health treatment, citing the stigma of labels (Kim, Britt, Klocko, Riviere, & Adler, 2011). Studies indicated that mental health service needs are underestimated among the military population and are therefore a potential burden to an understaffed helping profession (Garvey Wilson et al., 2009; Hoge et al., 2006). In May of 2013, the DOD and VA created 1,400 new positions for mental health providers to serve military personnel (DOD, 2013). Moreover, as of March 2013, the DOD-sponsored veterans crisis line reported more than 800,000 calls (DOD, 2013). It is evident that the veteran population remains at risk for problems related to optimal mental health functioning and therefore requires assistance from trained helping professionals.

Historically, the DOD employed social workers and psychologists almost exclusively to provide mental health services in the military setting. Recently, the DOD and VA expanded services and created more positions for mental health clinicians (U.S. VA, 2012). Because licensed professional counselors (LPCs) are now employable by VA service providers (e.g., VA hospitals) and approved TRICARE providers (Barstow & Terrazas, 2012), it is imperative to develop an understanding of the military system, especially of the potential conflict that may exist between military protocol and counselor ethical guidelines. The military health system requires mental health professionals to be appropriately credentialed (e.g., licensed), and credentialing results in the mandatory adherence to a set of professional ethical standards (Johnson, Grasso, & Maslowski, 2010). However, there may be times when professional ethical standards do not align with military regulations. Thus, an analysis of the counselor ethical codes relevant to the military population is presented. At times, discrepancies between military protocol and counselor ethical codes may emerge; therefore, recommendations for navigating such ethical dilemmas are provided. A case study and analysis from the perspective of two ethical decision-making models are presented.

Ethical Considerations for Counselors

The mission of the American Counseling Association (ACA) Code of Ethics (2005) is to establish a set of standards for professional counselors, which ensure that the counseling profession continues to enhance the profession and quality of care with regard to diversity. As professional counselors become employed by various VA mental health agencies or apply for TRICARE provider status, it is important to identify specific ethical codes relevant to the military population. Therefore, three categories of ethical considerations pertinent to working with military service members are presented: confidentiality, multiple relationships, and cultural competence.

Confidentiality

The ACA Code of Ethics (2005) suggests that informed consent (A.2.a., p. 4) be a written and verbal discussion of rights and responsibilities in the counseling relationship. This document includes the client right for confidentiality (B.1.c., p. 7) with explanation of limitations (B.1.d., p. 7). The limitations, or exceptions, to confidentiality include harm to self, harm to others and illegal substance use. In the military setting, counselors may need to consider other exceptions to confidentiality including domestic violence (Reger, Etherage, Reger, & Gahm, 2008), harassment, criminal activity and areas associated with fitness for duty (Kennedy & Johnson, 2009). Also, military administrators may require mandated reporting when service members are referred for substance abuse treatment (Reger et al., 2008). When these conditions arise in counseling, the military may require reporting beyond the standard ethical protocol to which counselors are accustomed.

Counselors working in the VA mental health system or within TRICARE may need to be flexible with informed consent documents, depending on the purpose of services sought. Historically, veterans represented those who returned from deployment and stayed home. Currently, military members may serve multiple tours of combat duty; therefore, the definition of veterans now includes active-duty personnel. This modern definition of veteran speaks to issues of fitness for duty, where the goal is to return service members ready for combat. Informed consent documents may need to outline disclosures to commanding officers. For example, if a service member is in need of a Command-Directed Evaluation (CDE), then the commander is authorized to see the results of the assessment (Reger et al., 2008). Fitness for duty is also relevant when service members are mandated to the Soldier Readiness Program (SRP) to determine their readiness for deployment. In these situations, counselors need to clearly explain the exception to confidentiality before conducting the assessment. Depending on the type of agency and its connection to the DOD, active-duty veterans’ health records may be considered government property, not the property of the service provider (McCauley, Hacker Hughes, & Liebling-Kalifani, 2008). It is imperative that counselors are educated on the protocols of the setting or assessments, because “providing feedback to a commander in the wrong situation can be an ethical violation that is reviewable by a state licensing authority” (Reger et al., 2008, p. 30). Thus, in order to protect the client and the counselor, limitations to confidentiality within the military setting must be accurately observed at all times. Knowledge of appropriate communication between the counselor and military system also speaks to the issue of multiple relationships.

Multiple Relationships

Kennedy and Johnson (2009) suggested creating collaborative relationships with interdisciplinary teams in a military setting in order to create a network of consultants (e.g., lawyers, psychologists, psychiatrists), which is consistent with ACA ethical code D.1.b to develop interdisciplinary relationships (2005, p. 11). However, when interdisciplinary teams are formed, there are ACA (2005) ethical guidelines that must be considered. These guidelines state that interdisciplinary teams must focus on collaboratively helping the client by utilizing the knowledge of each professional on the team (D.1.c., p. 11). Counselors also must make the other members of the team aware of the constraints of confidentiality that may arise (D.1.d., p. 11). In addition, counselors should adhere to employer policies (D.1.g., p. 11), openly communicating with VA superiors to navigate potential discrepancies between employers’ expectations and counselors’ roles in best helping the client.

In the military environment, case transfers are common because of the high incidence of client relocation, which increases the need for the interdisciplinary teams to develop time-sensitive treatment plans (Reger et al., 2008). Therefore, treatment plans not only need to follow the guidelines of A.1.c., in which counseling plans “offer reasonable promise of success and are consistent with abilities and circumstances of clients” (ACA, 2005, p. 4), but they also need to reflect brief interventions or treatment modalities that can be easily transferred to a new professional. Mental health professionals may work together to best utilize their specialized services in order to meet the needs of military service members in a minimal time allowance.

For those working with military service members, consideration of multiple relationships in terms of client caseload also is important. Service members who work together within the same unit may seek mental health services at the same agency. Members of a military unit may be considered a support network which, according to ethical code A.1.d., may be used as a resource for the client and/or counselor (ACA, 2005, p. 4). However, learning about a military unit as a network from multiple member perspectives may also create a dilemma. Service members within a unit may be tempted to probe the counselor for information about other service members, or tempt the counselor to become involved in the unit dynamic. McCauley et al. (2008) recommended that mental health professionals avoid mediating conflicts between service members in order to remain neutral in the agency setting.

However, there are times when the unit cohesion may be used to support the therapeutic relationship. Basic military training for service members emphasizes the value of teamwork and the collective mind as essential to success (Strom et al., 2012). It is important for counselors to approach military service member clients from this perspective, not from a traditional Western individualistic lens. Mental health professionals also are warned not to be discouraged if rapport is more challenging to build than expected. Hall (2011) suggested that the importance of secrecy in the military setting might make it more difficult for service members to readily share in the therapeutic relationship. Researchers noted that military service members easily built rapport with each other in a group therapy session, often leaving out the civilian group leader (Strom et al., 2012). It might behoove counselors to build upon the framework of collectivism in order to earn the trust of members of the military population. Navigating the dynamic of a unit or the population of service members accessing care at the agency may be a challenge; however, counselors are able to alleviate this challenge with increased knowledge of the military culture in general.

Cultural Competence

The military population represents a group of people with a unique “language, a code of manners, norms of behavior, belief systems, dress, and rituals” and therefore can be considered a cultural group (Reger et al., 2008, p. 22). Reger et al. (2008) suggested that many clinical psychologists learned about military culture as active service members themselves. While there may be many veterans currently working as professional counselors, civilian counselors also serve the mental health needs of the military population; and as civilians, they require further training. The ACA Code of Ethics (2005) suggests that counselors communicate with their clients in ways that are culturally appropriate to ensure understanding (A.2.c., p. 4). This can be achieved by prolonged exposure to military culture or by seeking supervision from a professional involved with the military mental health system (Reger et al., 2008). Strom et al. (2012) outlined examples of military-specific cultural components for professionals to learn: importance of rank, unique terminology and value of teamwork. It behooves counselors intending to work with the military population to learn terminology in order to understand service members. For example, R&R refers to vacation leave and MOS or rate refers to a job category (Strom et al., 2012).

Personal values may cause dilemmas for a mental health professional working within the VA system. This can be especially true during times of war. Stone (2008) suggested that treating veterans of past wars may be easier than working with military service members during current combat because politics may be intensified. A counselor who does not support the current wartime mission may be conflicted when clients are mandated to return to active-duty assignments (Stone, 2008). The ACA Code of Ethics (2005) addresses the impact of counselors’ personal values (A.4.b., pp. 4–5) on the therapeutic relationship. It is recommended that counselors be aware of their own values and beliefs and respect the diversity of their clients. Counselors need to find a way to value the contributions of their client when personal or political opinion conflicts with the DOD’s plans or efforts overseas. If one wants to be successful with this population, Johnson (2008) suggested the foundational importance of accepting the military mission. If this is in direct conflict with the counselor’s values, it may be recommended for the counselor to consider the client’s value of the mission.

The ACA ethical code stresses the importance of mental health professionals practicing within the boundaries of their competence and continuing to broaden their knowledge to work with diverse clients (ACA, 2005, C.2.a., p. 9). Counselors should only develop new specialty areas after appropriate training and supervised experience (ACA, 2005, C.2.b., p. 9). Working within the VA mental health system, mental health professionals may be asked to provide a service in which they are not competent (Kennedy & Johnson, 2009). Such a request may occur more frequently here than in other settings, due to the high demand of mental health services and low availability of trained professionals (Garvey Wilson et al., 2009; Hoge et al., 2006). Counselors must determine if their experience and training can be generalized to working with military service members (Kennedy & Johnson, 2009), and may be their own best advocate for receiving appropriate training.

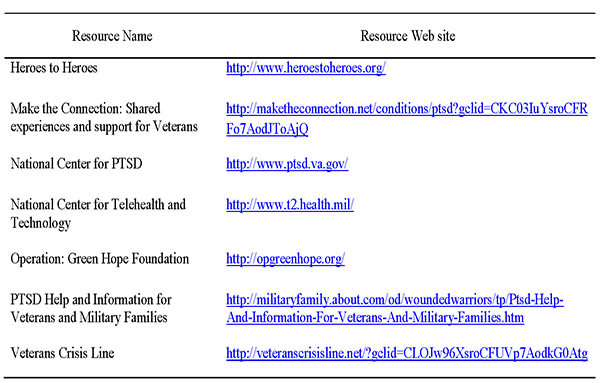

Awareness of when and how military service members access mental health services also might be important to consider. Reger et al. (2008) reported that military personnel were more likely to access services before and after a deployment. Researchers specified a higher prevalence rate of access 3–4 months after a deployment (Hoge et al., 2004). The relationship of time between deployment and help-seeking behaviors suggests that counselors should be prepared for issues related to trauma. For women, combat-related trauma is compounded with increased rates of reported military sexual trauma (Kelly et al., 2008). Counselors would benefit from additional trainings in trauma intervention strategies. The VA and related military organizations offer many resources online to educate professionals working with military members with identified trauma symptoms (U.S. VA., n.d.).

Advocating for appropriate training in areas of incompetence is the responsibility of the professional, who should pursue such training in order to best meet the needs of the military population. It is best practice for mental health professionals to be engaged in ongoing trainings to ensure utilization of the latest protocols and treatment modalities (McCauley et al., 2008). Trainings may need to extend beyond general military culture, because each branch of service (e.g., Army, Marines, Navy) could be considered a cultural subgroup with unique language and standards. For example, service members in the Army are soldiers, whereas members of the Navy are sailors (Strom et al., 2012).

This article has outlined many ACA (2005) ethical guidelines pertinent to working with the military population. However, as presented, there are times when counselor ethical codes conflict with military regulations. Counselors interested in working in the military setting or with military personnel may consider decision-making models to address ethical dilemmas.

Recommendations for Counselors

The military mental health system has almost exclusively employed psychologists and social workers. Counselors interested in employment within VA agencies or as TRICARE providers may utilize the resources created by these practitioners to better serve the military population. Two ethical decision-making models are presented, and a case study is provided to demonstrate how to implement the models.

Ethical Models

The ACA Code of Ethics (2005) advises counselors to adhere to the code of ethics whenever possible, working towards a resolution of the conflict (H.1.b., p. 19). If a favorable resolution cannot be formed, counselors have the choice to act in accordance with the law or regulation. Psychology researchers have suggested ethical models for professionals to use during times of dilemma within the military setting. The first model presented considers three overarching approaches to address ethical dilemmas; and the second model presented is a more specific stage model with which to approach dilemmas. These models may serve to assist counselors as the counseling profession gains more experience in the VA system and eventually develops counselor-specific decision-making models.

Approach model. Johnson and Wilson (1993) identified three approaches for psychologists to consider when navigating the ethical quandaries of the military mental health system. The first, the military manual approach, occurs when professionals adhere strictly to military regulations without consideration for the specific client’s needs. The second, the stealth approach, occurs when there is strict adherence to the mental health professionals’ code of ethics, regardless of the legalities surrounding the circumstances. While the client’s best interests may be at the forefront in this approach, the counselor must also take into account the possibility of being the subject of legal action for not adhering to the standards set by the military. For example, the counselor may use ambiguous wording within the client file or leave some information out altogether, so that if the files were requested, the client’s information would be protected (Johnson & Wilson, 1993). The third, the best interest approach, occurs when the counselor maintains focus on the client’s best interest while also adhering to the standards of the military. This may require professionals to adhere to the minimum professional standards in order to accommodate the client’s best interest. Although most professionals have deemed this approach the best option, it also leads to the most ambiguity. Under certain circumstances, the counselor also must take into account what is in the best interest for society as a whole, while also navigating a responsibility to the client and the military mental health system. Researchers in psychology responded to the ambiguity of this model by developing a more specific stage model to assist professionals with ethical dilemmas.

Stage model. Barnett and Johnson (2008) proposed a 10-stage model to follow when navigating an ethical dilemma. They advise that professionals must do the following:

1. Clearly define the situation.

2. Determine what parties could be affected.

3. Reference the pertinent ethical codes.

4. Reference the pertinent laws and regulations.

5. Reflect on personal thoughts and competencies on the issue.

6. Select knowledgeable colleagues with whom to consult.

7. Develop alternate courses of action.

8. Evaluate the impact on all parties involved.

9. Consult with professional organizations, ethics committees and colleagues.

10. Decide on a course of action.

Barnett and Johnson (2008) also noted that once a decision is made, the process does not end. It is best practice to monitor the implications and, if necessary, modify the plan. Documentation throughout this entire process is necessary for the protection of the counselor, the client and other involved stakeholders. Counselors working in the military mental health system may find this 10-stage model helpful when navigating ethical dilemmas.

To better understand the implementation of the two presented ethical decision-making models, a case study was developed. The case is then conceptualized from both the approach model and stage model, and the ethical dilemmas associated with the case are discussed.

Case Study

Megan is a licensed professional counselor employed at a clinic that serves military service members. She provides individual outpatient counseling to veterans and family members, as well as facilitates veteran support groups. Megan’s client, Robert, is a Petty Officer First Class in the Navy. Robert is married with two children. In recent sessions, Megan became concerned with Robert’s increased alcohol use. Recently, Robert described a weekend of heavy drinking at the local bar. Although Robert drove after leaving the bar both nights, Megan suspected that he was not sober enough to drive. In a follow-up session, Robert reported that his binge-drinking weekend caused friction at home with his wife, and that he missed his children’s soccer games. During his most recent session, Robert was visibly distressed as he disclosed to Megan that he received orders for a deployment in 3 months. Robert is anxious about informing his wife and children of the pending 6-month deployment, as he knows it will only increase conflict at home. Robert reported that his family could use the increase in pay associated with family separation and tax-free wages during deployment. However, he also knows that deployments cause tension with his wife, which has already increased due to Robert’s recent drinking binges. While leaving the session, he mentioned with a laugh that he would rather go to the bar than go home.

Analysis from approach model. Megan may consider using Johnson and Wilson’s (1993) ethical approach model as she conceptualizes the potential ethical dilemma presented in Robert’s case. From a military manual approach, Megan may need to report Robert’s recent alcohol abuse behavior to his superior, as it may impact his fitness for duty on his next deployment. And although Robert has not been caught drinking and driving or charged with a crime, his behavior also puts him at risk of military conduct violations. However, when Robert originally came to the clinic, he did so of his own accord, not under orders, which could mean that notifying a commanding officer is an ethical violation. In consideration of the stealth approach, Megan may review the ACA (2005) ethical guidelines and conclude that there are no violations at risk if she chooses not to report Robert’s drinking habits. However, Megan contemplates whether addressing Robert’s drinking binges is in his best interest overall. She understands that the money associated with deployment is important to Robert’s family at this time; however, his drinking may put him at increased risk during deployment. Finally, Megan applies the best-interest approach to Robert’s situation. Megan may refer Robert to the center’s substance use support group. This referral will be reflected in Robert’s records, but if he begins receiving treatment for his alcohol abuse now (3 months before deployment), there may be time for Robert to demonstrate significant progress before his fitness for duty assessment.

Analysis from stage model. Megan may consider her ethical dilemma from Barnett and Johnson’s (2008) 10-stage model. In stage 1, she clearly defines the situation as Robert’s alcohol abuse and pending deployment. In stage 2, Megan considers who may be affected in this situation. She understands that Robert’s family would benefit from the extra money associated with the deployment, and therefore the family may be impacted if Robert is not deployed. Megan also notes that the family is already negatively impacted by his recent drinking binge (e.g., conflict with his wife, missed soccer games). If Robert’s problematic drinking continues, he is at risk for evaluation and promotion issues. In stage 3, Megan reflects upon the ACA (2005) ethical codes in order to better understand her dilemma from a counselor’s view. Robert has a right to confidentiality (B.1.c., p. 7) with limitations including illegal substance use (B.1.d., p. 7). However, Robert’s current substance is alcohol, which is a legal substance. Megan considers the importance of his support network (A.1.d., p. 4) including his family and unit, but she does not have the ethical right to disclose her concerns about his substance abuse. In stage 4, Megan considers the pertinent laws and regulations of the dilemma. As per the clinic regulations, she is aware that if she makes a substance use program referral, it will be reflected in Robert’s record, which is the property of the military. Megan also is aware that Robert has not committed a documented crime of driving under the influence.

In stage 5 of the 10-stage ethical decision-making model, Megan must reflect on her personal thoughts and competencies. She is very concerned about Robert’s increased use of alcohol and is worried for his safety if deployed. Megan feels less confident in her ability to accurately assess for substance use problems. She facilitates the PTSD support group for the clinic, which is her specialty area. Megan recognizes that she is fond of Robert as a client and is disappointed that he could be jeopardizing his family and career with his alcohol abuse. She considers whether she is overreacting to his binge-drinking incident because of her higher expectations of him. In stage 6, Megan consults with her colleague who leads the substance use support groups at the clinic. She describes Robert’s recent abuse of alcohol and inquires as to whether he is a good candidate for the substance use group, needs more intense treatment, or needs no treatment at all. The colleague suggests that the group would be a very appropriate fit for someone with Robert’s symptoms.

In stage 7, Megan develops her course of action to refer Robert to the substance use group. Then, in stage 8, she evaluates the plan for potential impact on parties involved. Megan conceptualizes that Robert may be at risk for losing his deployment orders if he is accessing substance use treatment. Megan believes she has reduced this potential impact by referring to the substance support group, rather than an inpatient treatment facility, which may be more appropriate for a dependence issue. Megan recognizes that attending a 90-minute group each week will take Robert away from his family, but she also realizes that the 90-minute commitment is less than his current time spent away from the family when binge drinking. Megan reflects upon how her therapeutic relationship with Robert may be strained at the time of referral, and is prepared for a potential negative response from her client. She trusts in their therapeutic relationship and moves forward. In stage 9, Megan presents her planned course of action to her supervisor at the clinic. The supervisor approves the referral for the support group, but also suggests that Megan consider a referral to couples counseling for Robert and his wife, which may assist with resolving conflicts before the deployment.

In the final stage, Megan proposes the treatment plan of action to Robert in their next session. Megan explains that she feels ethically obligated to refer Robert to the substance use support group, and that as of now, Robert may make this choice for himself. Megan and Robert discuss the potential that substance use treatment may no longer be a choice in the future if his current drinking behavior continues. There is more discussion of fitness for duty and how participation in the support group will positively reflect upon the assessment in the future. Megan also presents Robert with the recommendation of couples counseling to help mediate relationship conflicts before deployment. She reports that if Robert and his wife decide to receive couples counseling, she can provide a referral for them at that time.

With the ethical decision-making models presented, the counselor is able to successfully navigate the military mental health system, while still maintaining the professional standards of the counseling profession. In each model, the situation is resolved with considerable attention to the client’s best interest, while maintaining the expectations of the military clinic. Psychologists developed the two ethical models presented, and counselors may choose to utilize these approaches until more counselor-specific ethical processes are created. As counselors become more permanent fixtures in the VA mental health system and as TRICARE providers, opportunities to develop an ethical decision-making model will likely arise.

Conclusion

The recent inclusion of counselors as mental health professionals within the VA system and as TRICARE providers allows for new employment opportunities with the military population. However, these new opportunities are not without potential dilemmas. Counselors interested in working with service members need to be educated on the potential conflict between counselor professional ethical guidelines and military protocols. Future research in the counseling field may develop a counselor-specific ethical decision-making model. In the meantime, counselors may utilize or adapt the ethical decision-making models created by other mental health professionals, who have a longer history working with the military population.

References

American Counseling Association. (2005). ACA code of ethics. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/Resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Barnett, J. E., & Johnson, W. B. (2008). The ethics desk reference for psychologists. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Barstow, S., & Terrazas, A. (2012, February). DoD releases TRICARE rule on independent practice for counselors. Counseling Today, 54(8), 10. Retrieved from

http://ct.counseling.org/2012/02/dod-releases-tricare-rule-on-independent-practice-for-counselors/

Garvey Wilson, A. L., Messer, S. C., & Hoge, C. W. (2009). U.S. military mental health care utilization and attrition prior to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44, 473–481. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0461-7

Hall, L. (2011). The importance of understanding military culture. Social Work in Health Care, 50, 4–18. doi:10.1080/00981389.2010.513914

Hoge, C. W., Auchterlonie, J. L., & Milliken, C. S. (2006). Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 295(9), 1023–1032. doi:10.1001/jama.295.9.1023

Hoge, C. W., Castro, C. A., Messer, S. C., McGurk, D., Cotting, D. I., & Koffman, R. L. (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. The New England Journal of Medicine, 351(1), 13–22. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040603

Holder, K. A. (2007). Comparison of ACS and ASEC data on veteran status and period of military service: 2007. U.S. Census Bureau: Housing and Household Economics Statistics Division. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/veterans/files/comparison_report.pdf

Johnson, W. B. (2008). Top ethical challenges for military clinical psychologists. Military Psychology, 20, 49–62. doi:10.1080/08995600701753185

Johnson, W. B., Grasso, I., & Maslowski, K. (2010). Conflicts between ethics and law for military mental health providers. Military Medicine, 175, 548–553.

Johnson, W., & Wilson, K. (1993). The military internship: A retrospective analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 24(3), 312–318. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.24.3.312

Kelly, M. M., Vogt, D. S., Scheiderer, E. M., Ouimette, P., Daley, J., & Wolfe, J. (2008). Effects of military trauma exposure on women veterans’ use and perceptions of Veterans Health Administration care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23, 741–747. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0589-x

Kennedy, C. H., & Johnson, W. B. (2009). Mixed agency in military psychology: Applying the American Psychological Association ethics code. Psychological Services, 6(1), 22–31. doi:10.1037/a0014602

Kim, P. Y., Britt, T. W., Klocko, R. P., Riviere, L. A., & Adler, A. B. (2011). Stigma, negative attitudes about treatment, and utilization of mental health care among soldiers. Military Psychology, 23, 65–81. doi:10.1080/08995605.2011.534415

Martin, J., Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M., Lou, K., & Tucciarone, P. (2009). A comparative review of U.S. military and civilian suicide behavior: Implications for OEF/OIF suicide prevention efforts. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 31(2), 101–118.

McCauley, M., Hacker Hughes, J., & Liebling-Kalifani, H. (2008). Ethical considerations for military clinical psychologists: A review of selected literature. Military Psychology, 20, 7–20. doi:10.1080/08995600701753128

O’Gorman, K. (2012, August 16). Army reports record suicides in July [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://iava.org/blog/army-reports-record-high-suicides-july

Reger, M. A., Etherage, J. R., Reger, G. M., & Gahm, G. A. (2008). Civilian psychologists in an army culture: The ethical challenge of cultural competence. Military Psychology, 20, 21–35. doi:10.1080/08995600701753144

Snell, F., & Tusaie, K. R. (2008). Veterans reported reasons for seeking mental health treatment. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 22(5), 313–314. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2008.06.003

Stone, A. M. (2008). Dual agency for VA clinicians: Defining an evolving ethical question. Military Psychology, 20, 37–48. doi:10.1080/08995600701753177

Strom, T. Q., Gavian, M. E., Possis, E., Loughlin, J., Bui, T., Linardatos, E.,…Siegel, W. (2012). Cultural and ethical considerations when working with military personnel and veterans: A primer for VA training programs. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 6(2), 67–75. doi:10.1037/a0028275

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey. (2011). B21002: Period of military service for civilian veterans 18 years and over (2011 American Community Survey 1-year estimates). Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_11_1YR_B21002&prodType=table

U.S. Department of Defense. (n.d.). Enhanced post-deployment health assessment (PDHA) process (DD Form 2796). Retrieved from http://www.pdhealth.mil/dcs/dd_form_2796.asp

U.S. Department of Defense. (2012). Army releases July suicide data, No. 683-12. Retrieved from http://www.defense.gov/releases/release.aspx?releaseid=15517

U.S. Department of Defense. (2013). DOD, VA and HHS partner to expand access to mental health services for veterans, service members, and families, No. 353-13. Retrieved from http://www.defense.gov/releases/release.aspx?releaseid=16024

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). PTSD: National center for PTSD. Retrieved from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/index.asp

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2012, April). VA adding family therapists and mental health counselors to workforce. Retrieved from http://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=2303

Elizabeth A. Prosek, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at the University of North Texas. Jessica M. Holm is a doctoral student at the University of North Texas. Correspondence can be addressed to Elizabeth A. Prosek, University of North Texas, 1155 Union Circle #310829, Denton, TX 76203-5017, elizabeth.prosek@unt.edu.

Apr 6, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 2

S. Beth Ruff, Michael A. Keim

There are 1.2 million school-age children with military parents in the United States, and approximately 90% attend public schools. On average, military children move three times more often than their civilian peers. Tensions at home, enrollment issues, adapting to new schools, and a lack of familiarity with military culture by public school professionals may adversely impact the academic, social and emotional growth of these students. Public school faculty and staff need to understand the challenges that multiple school transitions impose on military children in order to effectively meet the needs of this student population. In this article, the authors review the literature concerning obstacles and challenges mobile military children face, and discuss positive interventions that professional school counselors can employ to ease these transitions.

Keywords: school counselors, school transitions, military children, military culture

The Department of Defense (DOD) Demographics Report (2010) revealed that approximately 1.85 million children have one or both parents serving in the U.S. military. The report further explained that 1.2 million of these children have active-duty parents, and approximately 660,000 children have parents that serve in reserve positions in the military. Out of the 1.85 million military children, 1.2 million of them fall into the K–12 education range of 6–18 years of age (DOD, 2010). The Department of Defense Dependents Education (DODDE, 2012) budget for fiscal year 2013 estimated that 90% of these school-age military children attend public schools that are not sponsored by the DOD.

On average, military children move and change schools 6–9 times from the start of kindergarten to high school graduation (Astor, 2011; Berg, 2008; Kitmitto et al., 2011; Sherman & Glenn, 2011). Additionally, these military children move three times more often than their civilian peers, relocating every 1–4 years (Berg, 2008; Bradshaw, Sudhinaraset, Mmari, & Blum, 2010; Hipps, 2011). With military children comprising nearly 4% of the nation’s entire school-age population, public school administrators, teachers and school counselors should expect military students to transition in and out of their school populations (Rossen & Carter, 2011). Public school faculty and staff need to understand the challenges that multiple school transitions impose on military children in order to effectively meet the needs of this student population. In this article, the authors review the literature concerning the obstacles and challenges mobile military children face, and discuss positive interventions that professional school counselors can employ to ease transition.

Stressors for Military Families and Children

Military families face a unique set of life stressors specific to their culture. Hall (2008) describes the challenges faced by military families by stating that “the defining word for the military family is change; change is what their lives are about” (p. 193). As such, military families experience change and transition so frequently they often do not have time to grieve over the last transition before planning and preparing for the next. Relocation becomes a consistent stressor in the lives of military families, as the average military move occurs every 3 years, and some families, particularly families of high-ranking officers, move more frequently (Hall, 2008).

As noted in Weber and Weber (2005), previous studies (Pribesh & Downey, 1999; Simpson & Fowler, 1994; Wood, Halfon, Scarlatta, Newacheck, & Nessim, 1993) found relocation stress to have a detrimental effect on civilian child populations. School-age military children are especially vulnerable to the stress related to frequent transitions, as they must simultaneously cope with normal developmental stressors such as establishing peer relationships (Kelley, Finkel, & Ashby, 2003), conflict in parent/child relationships (Gibbs, Martin, Kupper, & Johnson, 2007; Lowe, Adams, Browne, & Hinkel, 2012), and increased academic demands (Engel, Gallagher, & Lyle, 2010). These additional stressors in conjunction with multiple school transitions could negatively affect the children’s adaption to new school environments. In addition to normative developmental stressors and frequent relocations, military children’s parents are often deployed, which can exacerbate stress in the children and may result in more barriers and maladjustment (Mmari, Bradshaw, Sudhinaraset, & Blum, 2010).

Transitional Barriers for Military Adolescent Students

Recognizing that these significant stressors for military children may be further complicated by multiple school transitions, the U.S. Army began to explore the lives of these children in order to identify ways to minimize the negative impacts of frequent relocation (Berg, 2008). In conjunction with the Military Child Education Coalition (MCEC), the Secondary Education Transition Study (SETS) was completed, which revealed specific educational challenges associated with multiple transitions (MCEC, 2001). The SETS study exposed several obstacles to transition between schools that impacted military children socially, emotionally and academically. Specific transition challenges identified by SETS for military adolescents include the following: slow transfer of school records and differences in curricula between schools, adapting to new school environments and making friends, limited access to extracurricular activities, a lack of understanding of military culture by public school teachers and staff, and tension at home and parental deployment (MCEC, 2001). The authors reviewed the literature for relevant information on each stressor.

Slow transfer of records and differences in curricula between schools. With each move to another state and school, military children encounter the challenges of slow transfer of records and differences in school curricula, which increase frustration with the transition process for parents and students (Sherman & Glenn, 2011). Kitmitto et al. (2011) found that enrollment into a new school could take up to 3 weeks, as the new school awaits the arrival of official records from the previous school. The lack of communication between the previous and receiving schools regarding history of schools attended, curricula, achievements, and stresses and traumas can lead to academic weaknesses (Berg, 2008). As military parents fulfill their duties to serve and protect the United States, the nation’s schools may hinder student progress by requiring them to take classes over again or denying them placement into gifted or special needs education due to slow school record exchange (Astor, 2011).

Military children face several academic challenges as a result of frequent school transition. The differences in curricula and school requirements result in educational gaps for military children, which might entail repeating classes and lessons, and missing crucial topics such as multiplication and fractions (Bradshaw et al., 2010). Mmari et al. (2010) noted that parents expressed their concern for their children’s education quality; because of the differences in grade levels between schools, children had to learn the same material or read the same books repeatedly. A recent study by the MCEC reported that the differences in curricula continue to vary from school to school; and parents’ most commonly discussed concerns were the differences in scope and sequence in mathematics, specifically as it leads up to algebra and higher-level coursework (MCEC, 2012). Military parents work hard to fill the gaps in their child’s education due to transition, but many feel that if they do not advocate for their children, they will fall significantly behind their peers academically (Mmari et al., 2010).

Adapting to new school environments and making friends. With each move, military children must cope with the stress of making new friends and leaving others behind, adapting to a new school environment at awkward times, and figuring out how to fit in (Kitmitto et al., 2011). In a study conducted by Bradshaw et al. (2010), military students reported that some significant stressors in school transition were adjusting to the physical campus and to the culture of the school, including being aware of the school’s procedures and policies. Military students often transition at random times throughout the school year and experience added stressors such as learning the layout of the school and assimilating into already-established social groups (Bradshaw et al., 2010). Lack of information from the new school, such as not providing a campus map or an explanation of the course schedule, may lead the child to believe that the school is not supportive, which in turn can negatively impact the child’s adjustment to transition to the new school environment (Bradshaw et al., 2010).

Military children are frequently forced to end relationships with friends at a previous school and begin new peer relationships at the new school. In a qualitative study of military children, the most commonly mentioned stressor related to school transitions was the challenge of making and maintaining close friendships (Bradshaw et al., 2010). Many students described that the inevitable ending of close relationships led them to avoid making close connections with peers at new schools. With each move, letting go and saying goodbye to friendships becomes harder for the military students; and to avoid the inevitable grief, many students will choose to have superficial relationships instead of close friendships. It is more difficult with such relationships to gain acceptance from established cliques and social networks. This leads to military students often lacking a feeling of connectedness with others in their new schools, which in turn may lead to maladjustment in the transition (Bradshaw et al., 2010).

Limited access to extracurricular activities. With each school transition, military students encounter further challenges to retaining or gaining eligibility to participate in athletics and extracurricular activities at their new school (Sherman & Glenn, 2011). Students involved in sports who move late into the school year may miss tryouts for teams. Additionally, transferring to another state may mean that the new school does not offer the same athletic programs (Bradshaw et al., 2010). Even when students are eligible to participate in sports, military students can have difficulty breaking into established athletic programs and teams. Mmari and colleagues (2010) found that military children often experience discrimination when they participate in athletics at the new school. Athletic coaches were reluctant to put military students on teams or in starting positions, as doing so could disrupt the team dynamics. Military students also struggled to bond with their new teammates, especially if a military student’s new position on the team resulted in an established teammate losing a starting position (Mmari et al., 2010).

Students taking part in other extracurricular activities, like student government, face similar challenges that limit their involvement. New military students may find that student government elections either happened before they entered the school or rely heavily on established popularity and previous school involvement, which would be difficult or impossible for a new student to demonstrate (Bradshaw et al., 2010). These challenges can negatively affect the military student’s adjustment to a new school, as they may hinder connectedness to the new school environment or create a sense of loss if the student was involved in high-status positions at a former school (Bradshaw et al, 2010). Limited access to these activities can lead to additional mental health concerns for the military student, as a decline in participation in such activities can cause further withdrawal and depressive symptoms (Rossen & Carter, 2011). The transition to a new school includes challenges both in the classroom and beyond.

Lack of understanding of military culture by public school teachers and staff. The way in which school teachers and staff interact with military students who transfer to their school can either increase or reduce the students’ stress. Unfortunately, administrators, educators and counselors in public schools tend to be unfamiliar with the specific issues and stressors that mobile military students encounter (Harrison & Vannest, 2008). Horton (2005) noted that because of their limited experience with the military, civilian school staff have a knowledge gap that affects their competence and effectiveness in working with military students and families. The school staff’s lack of understanding about the military students’ culture results in varying degrees of interactions ranging from overly sensitive to completely insensitive to their needs. Bradshaw et al. (2010) found that teachers’ expectations differ because they struggle with the right thing to do. Some teachers have high expectations for new military students and expect them to assimilate rather than acknowledging their unique issues. Other teachers recognize some of the issues military students face because of deployment, but choose to avoid the topic of war in the classroom or discourage the students from talking about their experiences as to not upset the students (Bradshaw et al., 2010).

In addition to the issue of sensitivity, teachers who are not familiar with military culture may maintain negative stereotypes or political ideologies that influence the way they interact with military students (Fenell, 2008). Horton (2005) explained that it is also possible for public school staff members to harbor strong negative feelings about the military, which may impact their treatment of the military students. Fear of discrimination may also be a factor that impedes school staff from identifying military students in their schools, as parents and students may not reveal their military connection (Bradshaw et al. 2010; Mmari et al., 2010). Additionally, Mmari and colleagues (2010) found that many teachers and counselors had not received information that would help them identify students connected to the military. While part of the school staff felt that properly identifying military students could aid in assisting and connecting with these students, others felt that labeling this population could result in prejudice toward the students by anti-military staff. A majority of the parents in the study reported that school staff did not know how to deal with and support military children and issues such as deployment, and that more training is needed (Mmari et al., 2010).

Tension at home and parental deployment. Relocation increases stress for all military family members. In preparing to move, parents are swamped with concerns and to-do lists, and may not have the patience or time to consider a child who is resistant to the transition (Hall, 2008). The numerous moves can leave parents feeling physically and emotionally exhausted, and less emotionally able to help their children cope with stress related to relocation (Bradshaw et al., 2010). Several studies reported that parental stress directly impacts the child’s ability to cope during stressful situations (Hall, 2008; Mmari et al., 2010; Waliski, Bokony, Edlund, & Kirchner, 2012). Further, parental stress increases the likelihood of conflicts between the parent and child and could lead to child maltreatment (Rentz et al., 2007; Waliski et al., 2012). Parents’ stress can exacerbate the emotional stress and frustration already felt by the military child due to transition.

In a qualitative research study by Bradshaw et al. (2010), the majority of military students reported that moving increased tension in the home. Some students reported feeling anger and resentment toward their parents and the military because of the constant uprooting and disruption due to change of duty stations. Many students reported telling parents that they refused to move or would run away to avoid moving again (Bradshaw et al., 2010). This negative and resistant behavior from a child can be an additional source of stress for the family. Parents may in turn view the behavior as a problem and punish or avoid the child instead of acknowledging the emotional strain the student is facing with transition (Harrison & Vannest, 2008).

The emotional stress of relocation can be further complicated if the military parent is deployed or at risk of being deployed. The constant fear for a parent’s safety can negatively affect a child academically, emotionally and behaviorally (Chawla & Solinas-Saunders, 2011; Harrison & Vannest, 2008; Mmari et al., 2010). Having a parent deployed in conjunction with a transition can lead to increased feelings of depression and anxiety. In a qualitative study of military students, many participants reported increased fear and anxiety for deployed parent’s safety. These military students also reported difficulty coping with the absence of the deployed parent at special occasions such as birthdays, school programs and sporting events (Mmari et al., 2010). Absence of the deployed parent from these significant life events can cause stress, depression, feelings of loss, and anxiety for the military child. These feelings are often externalized in the form of declining grades and behavior problems at home and school (Harrison & Vannest, 2008). Adolescents also may experience increased stress with role ambiguity during a parent’s deployment—as the family instantly becomes a single-parent home, the adolescent may take on additional responsibilities to support the remaining parent (Chawla & Solinas-Saunders, 2011; Harrison & Vannest, 2008).

Research following Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm during the Gulf War in 1991 confirmed that stresses do occur within families during and after deployment (Jensen & Shaw, 1996; Kelley, 1994; Norwood, Fullerton, & Hagen, 1996; Pierce, Vinokur, & Buck, 1998; Rosen, Teitelbaum, & Westhuis, 1993). In their study of absent Navy mothers due to deployment during the Gulf War, Kelley, Herzog-Simmer, and Harris (1994) found that maternal depression, decreased self-esteem, and dysphoria were significantly correlated with children’s internalizing behavior (e.g., anxiety, depression).

Likewise, nondeployed parents also experience stress during times of deployment (Mmari et al., 2010), which in turn may be felt by children in the home (Chawla & Solinas-Saunders, 2011). Harrison and Vannest (2008) report that in addition to feelings of worry and fear for their spouse’s safety, the remaining parent also grapples with the stress of increased role expectation and responsibilities as a single parent. Without support, the remaining parent may cope with role strain and anxiety by withdrawing emotionally from their children or responding with severe punishment to misbehavior (Harrison & Vannest, 2008). These children may face an increased risk of maltreatment or neglect as the remaining parent may become abusive to the children when a spouse is deployed (Chawla & Solinas-Saunders, 2011; Gibbs et al., 2007; Rentz et al., 2007). Deployment can have significant detrimental effects on an entire military family’s well-being and coping skills.

Support Systems and Military Children

While researchers have found many negative outcomes associated with school transitions for military children, supportive relationships appear to have a positive influence on outcomes for this group. Although the majority of the literature discusses the damaging consequences that multiple school transitions have on children from military families, some studies found that multiple school transitions fostered strength and resiliency. Lyle (2006) reported that there are mixed results in the literature regarding the effects of multiple school transitions. Multiple transitions have been shown to equip military children with more adaptability, accelerated maturity, deeper appreciation for cultural differences, and strong social skills in comparison to their civilian peers (Bradshaw et al., 2010; Mmari et al., 2010; Sherman & Glenn, 2011; Strobino & Salvaterra, 2000). Weber and Weber (2005) actually reported a lower rate of problems experienced by military adolescents exposed to increased frequency and number of relocations. Strobino and Salvaterra (2000) stated that whether transition affects military children positively or negatively depends largely upon their support systems. Students’ preoccupation with feelings of isolation and loneliness during school transition could result in poor grades and a decline in academic achievement. In contrast, military students who welcome change and find a new sense of responsibility during school transition may experience improved academic performance and achievement. It also was found that despite five or more school transitions, military children reported average to above-average grades, active involvement in extracurricular activities, and support of teachers and parents. This study attributed the positive adjustment of military students during multiple school transitions to supportive school cultures and strong parental involvement. The positive and negative results reveal that the level of school and parent support may be indicators of how well military students adjust during multiple school transitions (Strobino & Salvaterra, 2000).

Implications for School Counselors

Given the extensive influence that the school environment has on military students’ adjustment during school transitions, the importance of developing a supportive and understanding relationship with this student population is paramount. Rush and Akos (2007) note that school counselors are uniquely qualified to assist students with social, emotional and academic concerns. School counselors are specifically trained in child development, and they work closely with numerous sources of student support including parents, teachers and peers. Waliski et al. (2012) confirm that counselors possess the education and skills needed to help military students and are readily accessible within their community. Professional school counselors also have access to academic data that can be used to identify the specific needs of an enrolling military student, such as standardized test scores, attendance records, discipline referrals and report cards. Moreover, school counselors serve students directly by developing and implementing preventive programs and interventions that facilitate support and social belonging such as classroom guidance, intentional guidance groups and peer mentoring (Rush & Akos, 2007). The role of school counselors within the school environment places them in a unique position to serve and advocate for enrolling military students and consequently transform school transition into a positive experience. The following sections will provide an overview of ways that school counselors can support military students in their own schools.

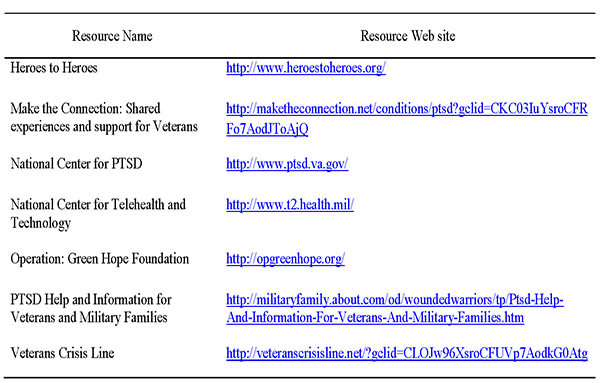

Becoming Informed About Military Life

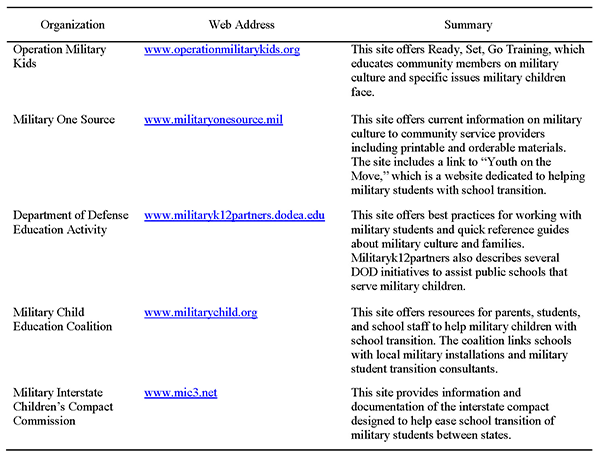

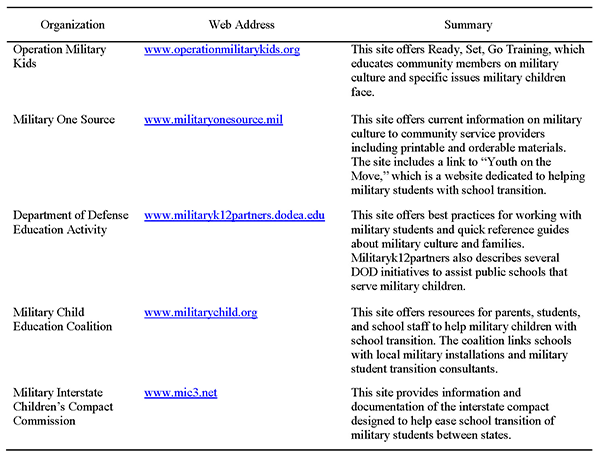

To initiate change, school counselors must first be informed about military life and become knowledgeable about resources and culturally sensitive interventions suited for military students (Waliski et al., 2012). Understanding the challenges and the unique needs of military students will help school counselors support military students and families during times of crisis (Harrison & Vannest, 2008). Several resources are available to assist school counselors in becoming advocates for and providing resources and interventions to military students. Organizations such as Operation Military Kids (OMK) and Military One Source provide specific tools and trainings on assisting military children and parents for school staff and community stakeholders (Eason, 2012). These resources could be used in staff development, classroom guidance, parent/teacher conferences, and small group and individual counseling (see Table 1).

Student-to-Student Interactions

With regard to strategies and programs that acclimatize new students to schools and ease the transition process, student-to-student programs were noted repeatedly in the literature (Berg, 2008; Bradshaw et al., 2010; Harrison & Vannest, 2008; Mmari et al., 2010; Strobino & Salvaterra, 2000). These programs connect new students with current students, who act as guides to the school grounds and reduce anxiety by initiating the friend-making process. One such program is noted by Rush and Akos (2007) in working with middle school students. The authors developed a 10-session, combination psychoeducational-counseling group created by school counselors to increase student knowledge concerning the deployment process. In addition to information sharing by the group leaders and group members early in the process and at the beginning of each session, the “later sessions, and the latter part of each session, are purposefully structured to be less directive and more process oriented to allow group members to pursue individual goals and provide more intrapersonal focus to help with particular issues that emerge” (Rush & Akos, p. 116). Students are further supported through the development of coping skills in a safe, encouraging environment.

Table 1

Web Resources to Support Military Students with Transition

Community Resources

Another avenue to help students adjust and adapt is connecting parents and caregivers to community resources. Mmari et al. (2010) found that some military parents did not utilize resources simply because they did not know they were available. Waliski et al. (2012) explained that counselors can serve as gatekeepers through whom military families can gain access to appropriate programs and services. Additionally, school counselors are in an advantageous position to develop partnerships between families and communities, to identify challenges such as transitions, to address these issues, and to advance student progress (Epstein & Van Voorhis, 2010). As military families transition, they may be unfamiliar with their new community and struggle to locate health care providers, childcare, tutoring, and mental health and counseling resources. School counselors are often equipped with lists for local providers and resources that could ease the transition for mobile military families. In addition to local resources, school counselors can proactively assist military children and their families by maintaining a record of resources specific to military families. For example, Tutor.com provides free tutoring and resources for military students (“Tutor.com for U.S. military families,” 2014). Also, a new Web site sponsored by the Department of Veterans Affairs, “Parenting for Service Members and Veterans,” has been launched just for military families (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2013). This resource addresses the unique challenges of parenting in military families through an online anonymous parenting course, interactive activities, and stories of real military and veteran families that provide valuable skills for the everyday challenges of raising military children. The course and content were developed by experts from the DOD. By connecting parents to resources, the school counselor can assist in reducing tension at home and increasing parental support and school involvement.

Staff Trainings

An important strategy for school counselors to implement in their schools is facilitating school staff trainings specific to military culture and needs of military students. Harrison and Vannest (2008) suggest that teachers receive professional development focused on military culture and the skills necessary to assist their military students. Strobino and Salvaterra (2000) explain that it is important for all stakeholders to be aware of the relationship between the student’s experiences and school success. School counselors and other school professionals are encouraged to focus on identifying the strengths of military students. Staff training can facilitate cultural sensitivity and supportive student/teacher relationships that contribute to positive school experiences.

A number of organizations—from the community to the national level—can provide training to assist educational professionals in working with the military community. Veterans’ organizations, such as Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) or the American Legion, have posts in local communities with representatives appointed to serve schools and other civic institutions. National Guard or reserve posts and active-duty military installations have a public affairs officer (PAO) who is available to discuss military-related issues such as deployment with the educational community as well. Additionally, the MCEC (2012), a federally recognized nonprofit organization, is specifically “focused on ensuring quality educational opportunities for all military children affected by mobility, family separation, and transition.” They provide ongoing training for school counselors and other education professionals both online and in face-to-face settings. Two MCEC programs in particular relate directly to school transitions. The Supporting Military Children through School Transitions: Foundations focuses on the military-connected child’s experience with transitions by addressing “military lifestyle and culture, school transition perspectives, and identifying local transition challenges.” The second program—Supporting Military Children through School Transitions: Social/Emotional Institute—focuses on the social and emotional effects of student transitions, including “deployment and separation, building confidence and resiliency, and supporting children through trauma and loss” (MCEC, 2012).

Advocating for Military Students