Jun 7, 2019 | Volume 9 - Issue 2

Hilary Dack, Clare Merlin-Knoblich

Although the American School Counselor Association National Model reflects the importance of high-quality school counseling core curriculum, or classroom guidance, as part of a comprehensive school counseling program, school counselors are often challenged by the complexities of designing an effective classroom guidance curriculum. This conceptual paper addresses these challenges by proposing the use of Understanding by Design, a research-based approach to curriculum design used widely in K–12 classrooms across the United States and internationally, to strengthen classroom guidance planning. We offer principles for developing a classroom guidance curriculum that yields more meaningful and powerful lessons, makes instruction more cohesive, and focuses on what is critical for student success.

Keywords: school counseling, school counselor, classroom guidance, school counseling core curriculum, Understanding by Design

In comprehensive school counseling programs, school counselors use a range of approaches to support students’ academic achievement, social and emotional growth, and career development (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2012). Classroom guidance is one delivery method of such supportive approaches, advantageous in part because it allows school counselors to reach all students in their schools (ASCA, 2012; Lopez & Mason, 2018). This curriculum is ideally “a planned, written instructional program that is comprehensive in scope, preventative in nature, and developmental in design” (ASCA, 2012, p. 85). In systematically delivering classroom guidance, school counselors use planned lessons crafted to ensure students acquire the desired knowledge, skills, and attitudes suited to their developmental levels (ASCA, 2012). These lessons comprise critical time school counselors spend in direct service to students. ASCA (2012) recommends school counselors spend 15%–45% of their time (depending on school level) delivering classroom guidance; thus, development of classroom guidance curriculum warrants careful consideration and intentionality (Lopez & Mason, 2018; Vernon, 2010).

Researchers have highlighted the value of classroom guidance for student outcomes (Bardhoshi, Duncan, & Erford, 2018; Villalba & Myers, 2008). For example, Villalba and Myers (2008) found that student wellness scores were significantly higher after a three-session classroom guidance unit on wellness. Similarly, Bardhoshi et al. (2018) found that teacher ratings of student self-efficacy were significantly higher after a 12-lesson classroom guidance unit on self-efficacy. In a causal-comparative study of 150 elementary schools, Sink and Stroh (2003) found that after accounting for socioeconomic differences, schools with comprehensive school counseling programs including classroom guidance had higher academic achievement than schools without such interventions.

The ASCA National Model (2012) reflects the importance of classroom guidance in a comprehensive school counseling program. For instance, designing a curriculum action plan is a key task in the management quadrant of the model. ASCA recommends school counselors develop a curriculum for classroom guidance that aligns with both student needs and prescribed standards. (Although ASCA [2012] refers to delivering a school counseling core curriculum, we use the term classroom guidance because of its familiarity among school counselors and counselor educators.) Once school counselors identify these student needs and prescribed standards, they meaningfully design corresponding lesson plans. ASCA (2012) asserts, “The importance of lesson planning cannot be overstated. . . . It is imperative to give enough time and thought about what will be delivered, to whom it will be delivered, how it will be delivered, and how student[s] . . . will be evaluated” (p. 55).

Despite these recommendations, school counselors appear hindered in designing highly effective lessons because of their limited training in curriculum design (Desmond, West, & Bubenzer, 2007; Lopez & Mason, 2018). This may occur in part because counselor educators do not consistently teach methods of developing a classroom guidance curriculum (Lopez & Mason, 2018). Standards of the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP, 2015) reflect this lack of emphasis. Of the 33 CACREP school counseling specialty-area standards, only one standard (G.3.c.) relates to the topic of curriculum development. Indeed, after reviewing classroom guidance lesson plans on the ASCA SCENE website (ASCA, 2016), Lopez and Mason (2018) noted a need for better instruction on lesson design, concluding, “school counselors need further training in incorporating standards and developing learning objectives” (p. 9). We seek to address this need by introducing Understanding by Design (UbD; Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, 2011), a research-based approach to curriculum development used widely in K–12 classrooms across the United States, to strengthen the classroom guidance planning process. In doing so, we offer a framework for redesigning curriculum in response to three common questions from school counselors: How can I make student experiences in my classroom guidance lessons more meaningful, relevant, rigorous, and powerful? Because I see each class infrequently, how can I make my lessons more cohesive, rather than a series of disconnected activities? and How can I connect my lessons more directly to what I want my students to apply to their daily lives and accomplish after they leave my program?

Applying UbD to Classroom Guidance Curriculum Development

UbD presents a curriculum design framework for purposeful planning for teaching. The goal of this framework is teaching for understanding (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, 2011). Understanding goes beyond simply recalling facts or information. It involves a student coming to own an idea by deeply grasping how and why something works. Those who teach for understanding give students opportunities to make meaning of content through “big ideas” and transfer understanding of these ideas to new situations (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011). UbD presents a structured system for (a) distinguishing between what is essential for students to know, understand, and be able to do, and what would be nice to learn if more time were available; and (b) considering the big ideas of the curriculum at the unit level rather than the individual lesson level (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, 2011).

The UbD framework advocates the “backward design” of a unit through a three-stage sequence of clarifying desired results or goals of learning, determining needed evidence of learning, and planning learning experiences (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, 2011). Beginning the unit design process with the end—or learning result—in mind helps prevent “activity-oriented design.” This problem occurs when planning does not begin with identifying clear and rigorous goals, but instead begins with creating activities that are “‘hands-on without being minds-on’—activities [that], though fun and interesting, do not lead anywhere intellectually” (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, p. 16). Activity-oriented design is a common problem in more traditional curriculum design approaches. Other problems in traditional approaches include: (a) a pattern of teaching in which the teacher directly transmits shallow factual content to students who passively receive information, making lessons more teacher-centered than student-centered; or (b) failing to ask students to practice skills or create products that have real-world applications (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, 2011).

UbD offers a way of thinking about curriculum design, not a recipe, a prescription, or a mere series of boxes on a template to be filled in (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011). It presents guiding principles about planning for teaching that apply to teaching any topic from any field to any learner. Although these principles are commonly used by teachers, their application is not limited to general education lessons in core subjects. Because existing research has examined the effects of teaching for understanding in diverse content areas with diverse learners, its application to classroom guidance is a logical extension of an approach that is widely accepted as best practice in K–12 schools. Because classroom guidance targets big ideas of healthy student development and important skills with immediate real-world applications, its curriculum is a particularly strong fit for UbD.

Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of UbD

Although the UbD framework was developed over the last 20 years, the ideas of designing a curriculum that targets understanding and planning a curriculum backward from desired results are not new. Leading curriculum theorists have advocated these principles for the last century. Almost 90 years ago, for example, Dewey (1933) championed the importance of teaching for understanding, describing understanding as occurring when inert facts gain meaning for the learner through connection-making. Taba (1962) also maintained that specific facts and skills serve “as the means to the end of gaining an understanding of concepts and principles” (p. 177), and that the curriculum should therefore target student understanding of broader transferable ideas, rather than individual facts and discrete skills. Additionally, major theorists have promoted backward design as an effective planning process for many decades (Gagné, 1977; Mager, 1988; Spady, 1994; Tyler, 1948). UbD outlines a clear and structured process for designing curriculum that reflects these long-standing ideas. In addition to deep theoretical foundations, UbD also has strong empirical support. Specifically, its principles are supported by research from the fields of cognitive psychology and neuroscience and by research conducted in K–12 schools.

In the seminal summary, How People Learn, the National Research Council (2000) presented a comprehensive overview of psychology research on learning. This research indicates meaningful learning results from teaching that centers on broad concepts and principles that promote deep understanding of important ideas, rather than on narrow facts; emphasizes application of understanding, rather than drill or rote memorization; and prompts students to authentically perform complex skills to show they know when, how, and why to use skills in new contexts. Recent neuroscience research also indicates long-term memory storage and retrieval is more likely to be successful when students use knowledge in authentic contexts; engage in active, experiential learning; and discern relationships among conceptual ideas (Willingham, 2009; Willis, 2006).

Although no large-scale studies of the effects of curriculum developed using the UbD framework on K–12 student outcomes have been published to date, a second body of research has examined the effects of understanding-focused curriculum and instruction on student achievement more broadly (McTighe & Seif, 2003). For instance, Hattie’s (2009) seminal synthesis of meta-analyses of more than 50,000 studies of more than 80 million students suggested learning outcomes across content areas are positively influenced by curriculum that achieves an effective balance between surface versus deep understanding leading to conceptual clarity. Additionally, in large-scale studies of data from the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), a cross-national comparative study of the education systems of 42 countries and their outputs, American eighth graders’ proficiency was found to be approximately average compared to other participating countries, while scores of 12th graders in advanced classes were at the bottom of the international distribution (Schmidt, Houang, & Cogan, 2004). When researchers sought to explain this relatively low performance of American students through analysis of TIMSS data, they painted a bleak picture of U.S. curriculum (e.g., Schmidt et al., 2004; Schmidt, McKnight, & Raizen, 1997), characterizing it as unfocused, lacking a coherent vision reflecting recognition of which ideas in a discipline are most important (Schmidt et al., 1997), and being “a mile wide and an inch deep” (Schmidt et al., 2004). A second series of studies on the influence of varied math curriculum on student outcomes indicated that teaching with a focus on understanding allowed students to both learn basic skills and develop more complex reasoning compared to more traditional curriculum (Senk & Thompson, 2003). The principles of UbD respond directly to the curricular problems outlined in these studies of K–12 learner outcomes.

Although research suggests students exposed to curriculum emphasizing understanding may experience improved outcomes compared to those who experience traditional curriculum, it also suggests that understanding-focused curriculum design is not widespread. For example, Weiss, Pasley, Smith, Banilower, and Heck (2003) conducted a large-scale observational study of K–12 classrooms selected to be representative of the nation. Researchers evaluated observed lesson quality using criteria that included lesson design. Almost 60% of lessons were categorized as low quality. When identifying common weaknesses of lesson design, Weiss et al. (2003) reported many lessons lacked structures to encourage understanding and intellectual rigor, while high-quality lessons were distinguished by “a commitment to . . . understanding through . . . application” (p. xi).

Research has not yet examined the effects of a classroom guidance curriculum designed in accordance with UbD principles. However, recent research (Lopez & Mason, 2018) has suggested that, as in the general education contexts studied by Weiss et al. (2003), high-quality curriculum reflecting these principles may not be common in classroom guidance either. Lopez and Mason (2018) conducted a content analysis of 139 classroom guidance lesson plans posted on the ASCA SCENE website (ASCA, 2016), using a 12-category rubric to identify each lesson plan as ineffective, developing, effective, or highly effective. Lopez and Mason’s criteria for a highly effective lesson plan included: introducing a “new concept or skill” (p. 6), not just rote information; developing clear and concise objectives for the lesson that reflected “at least one higher-order thinking skill” (p. 6); providing “an opportunity for active student participation” (p. 6) and “application of skill” (p. 8); and tightly aligning all phases of the lesson to the lesson objectives (p. 7). These criteria reflected an emphasis on teaching for understanding, not simple factual acquisition. Notably, the researchers classified no lesson plans as highly effective and only 28% as effective. Thus, the majority of the lesson plans were found to be developing or ineffective (Lopez & Mason, 2018). Although the lesson plans reviewed for this study were not representative of all classroom guidance curriculum, it is noteworthy that these plans were publicly posted by school counselors as model curriculum, suggesting they believed the plans were effective. Our paper responds directly to Lopez and Mason’s pressing call for school counselors to “strengthen” their “skill set” (p. 9) by borrowing methods of lesson design and curriculum development from K–12 general education practices and applying them to the special context of classroom guidance.

In the sections that follow, we briefly outline UbD’s three design stages as applied to the development of a classroom guidance unit. We then offer an example of a school counselor’s application of the UbD framework to the revision of his classroom guidance curriculum at the program, grade, unit, and lesson levels. In keeping with UbD principles, we advocate that school counselors should treat consecutive classroom guidance lessons as one unit when they address similar topics or themes, even if school counselors present the lessons several weeks apart. We encourage school counselors to focus on designing cohesive units of a curriculum, rather than treating each lesson as an isolated learning experience.

“Backward Design” of a Curricular Unit

Stage 1. When applied to classroom guidance curriculum development, the first stage of backward design tasks school counselors with stating the learning goals, or desired results of a unit, with clarity and specificity. Although other curricular frameworks may refer to these statements of curricular aims as learning objectives, UbD uses the term learning goals to emphasize their purpose as a destination or end-point for student learning.

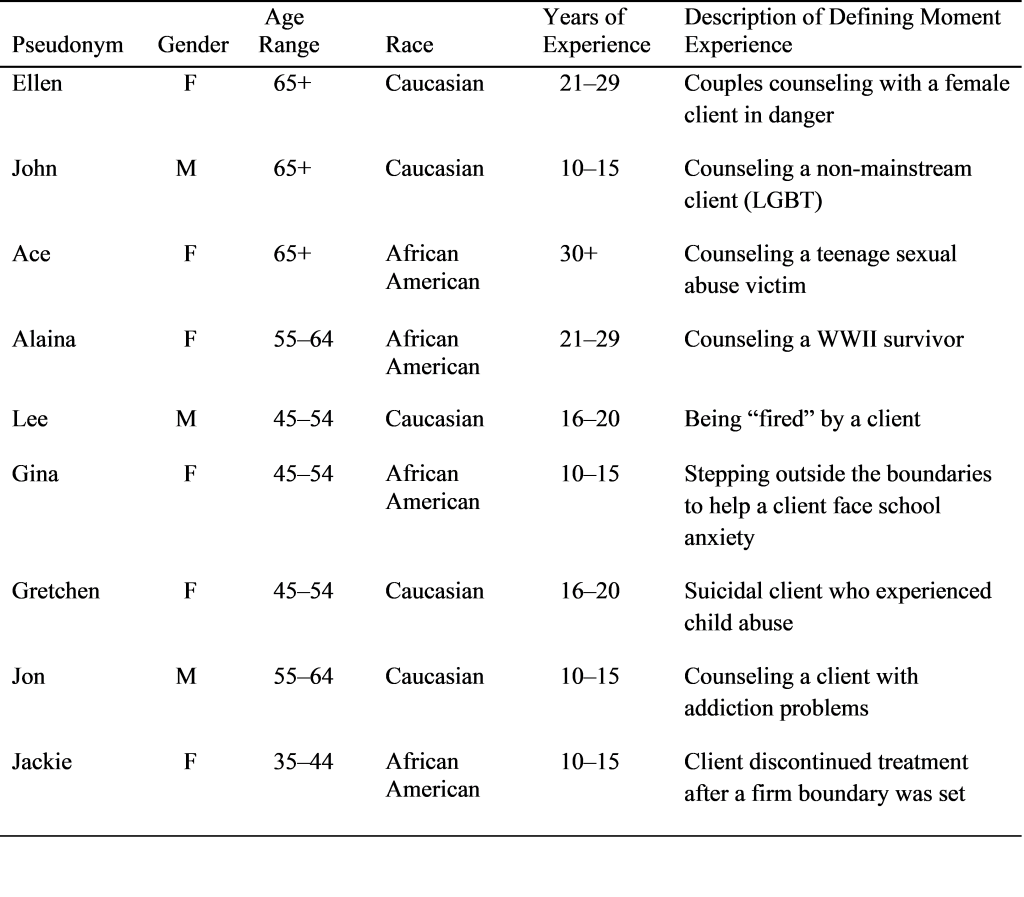

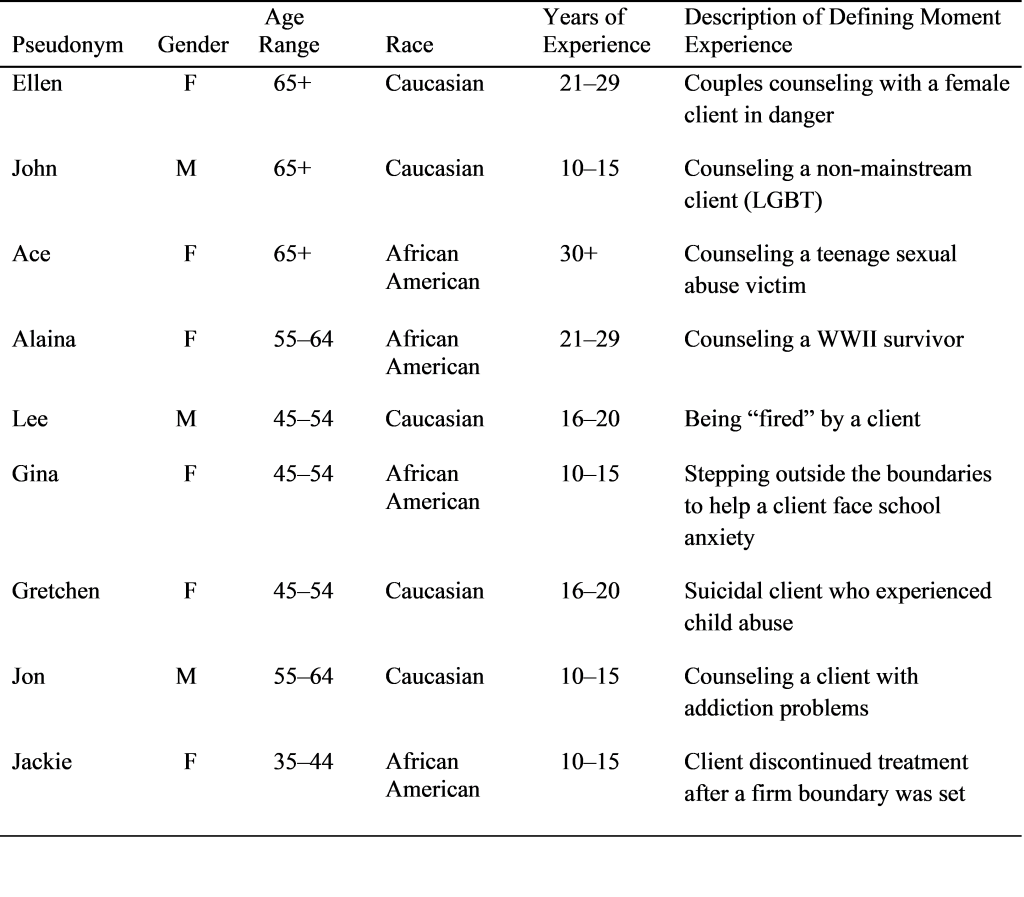

Stage 1 includes six components (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011). The first component prompts school counselors to identify pre-established goals for the program, such as national and state standards. The other five components are different types of learning goals to be written by the school counselor: transfer, understanding, essential question, knowledge, and skill goals. School counselors develop these goals through a combined process of “unpacking” standards into clearer or more specific learning outcomes, deciding which aspects of content are essential to emphasize in their context, and adding big ideas not suggested by the standards (see Table 1).

Table 1

| Type of

Learning Goal |

Definition of Learning Goal |

Stem That Begins

Learning Goal |

| Transfer |

Statements of what students should be able to accomplish independently in the long-term by using what they have learned (after completing the program/grade)

|

Students will be able to independently use their learning to…

|

| Understanding

|

Statements of big ideas reflecting an important and connective generalization that helps students see themes or patterns across different content topics

|

Students will understand that…

|

| Essential Question |

Thought-provoking big idea questions that foster inquiry, meaning-making, and application

|

Students will keep considering… |

| Knowledge |

Statements of specific facts that students should know and recall (such as vocabulary words and their definitions)

|

Students will know…

|

| Skill |

Statements of discrete skills that students should be able to do or use (starting with an active verb) |

Students will be able to… |

Note. Adapted from Wiggins and McTighe (2005, pp. 58–59) and Wiggins and McTighe (2011, p. 16). Examples of each type of learning goal from a classroom guidance curriculum are provided in Table 2 and Appendix A, and discussed in depth in the sections that follow.

Transfer, understanding, and essential question goals reflect long-term aims of education. Transfer goals describe desired long-term independent accomplishments, or what we want students to carry forward and apply in their academic, career, or personal achievements after they finish their last learning experience with their school counselor. Understanding and essential question goals reflect the “big ideas” of which we want students to actively make meaning for themselves through examination and inquiry. In contrast, knowledge and skill goals reflect short-term acquisition goals; they serve as means to the ends of exploration and application of big ideas (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, 2011).

In planning a classroom guidance curriculum, school counselors must think broadly about what students will learn in classroom guidance at the program level (everything learned throughout three years of middle school) and throughout a particular grade level (everything learned in sixth grade). They also must think more narrowly about what students will learn from classroom guidance in a particular unit (everything learned in a sequence of three sixth-grade lessons about similar topics) and in a specific lesson (everything learned on Tuesday). School counselors often write transfer goals, understanding goals, and essential question goals to apply to classroom guidance across their whole program or across a whole grade because these goals are broad and reflect long-term aims. When developing a single unit, school counselors might target one or two transfer goals out of all the transfer goals for the program or grade and one or two understandings and essential questions out of all the understandings and essential questions for the program or grade. In contrast, knowledge and skill goals are usually written to reflect new content that will be explicitly taught and assessed in just one unit (McTighe & Wiggins, 2015). Although the knowledge and skill may be used or practiced in future units, they would only be targeted as goals in one unit. After identifying a unit’s desired learning results in Stage 1, the school counselor then considers what specific evidence will be required to demonstrate whether those results have been achieved.

Stage 2. In Stage 2, the school counselor’s focus shifts to the particular products or performances that will provide evidence of proficiency with the learning goals identified in Stage 1. Tight alignment is needed between unit goals and unit assessments, meaning all key goals should be explicitly assessed through tasks or prompts thoughtfully crafted to reveal the student’s current proximity to each goal (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, 2011). Many school counselors may feel more comfortable assessing acquisition-focused goals like knowledge, because assessing through direct questioning for factual recall often seems familiar or straightforward. However, if a unit targets complex, authentic skills and big ideas, then the unit’s major assessments need to show the extent of learner understanding by asking students to (a) explain in their own words how they have drawn conclusions and inferences about understandings and essential questions and (b) apply their learning to new, real-world situations (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011). After the school counselor has identified both the desired unit results and the evidence needed to demonstrate whether results have been achieved, the focus shifts to developing learning experiences for the unit.

Stage 3. The learning plan created in Stage 3 includes the key learning activities students will complete in each lesson and the ongoing assessment embedded in those activities to monitor progress and provide students with feedback. Before planning individual lessons in detail, in Stage 3 the school counselor considers the unit’s big picture while determining the most effective learning experiences. Because tight alignment between learning activities and unit goals is needed, school counselors must purposefully select learning activities to provide direct opportunities for students to gain proficiency with targeted learning goals.

In sum, the three stages of backward design provide a sequenced structure designed to prompt deep thinking about powerful long- and short-term learning outcomes; how to elicit the best evidence of how well learners have achieved those outcomes; and which learning experiences will best lead to the desired outcomes.

ASCA Mindsets and Behaviors

Because ASCA’s (2014) Mindsets & Behaviors for Student Success: K–12 College- and Career-Readiness Standards for Every Student offers school counselors clear statements of the long-term aims of school counseling programs, they are an effective starting point for designing a classroom guidance curriculum. ASCA explains that the standards prioritize what students should be able to demonstrate as a result of their experiences in a school counseling program. The standards should be used by school counselors to “assess student growth and development” and “guide the development of strategies and activities” (p. 1). The six mindset standards are “related to the psycho-social attitudes or beliefs students have about themselves in relation to academic work” (p. 1). The 29 behavior standards “include behaviors commonly associated with being a successful student. These behaviors are visible, outward signs that a student is engaged and putting forth effort to learn” (p. 2). UbD’s approach to developing a curriculum that targets the understanding and transfer of big ideas aligns with the thrust of ASCA’s standards to deepen student understanding of key mindset ideas and transfer that understanding to new contexts through successful behaviors.

The following example demonstrates how one school counselor, Mr. Mendez, strengthened his classroom guidance curriculum by applying UbD principles. It describes the intentional work involved in making student experiences more meaningful, relevant, rigorous, powerful, and connected to the ASCA mindsets and behaviors. There is no single “right way” to develop a classroom guidance curriculum. We have worked with many school counselors and other educators in varied settings who have successfully applied UbD principles to their curriculum in different ways that match their own contexts. Mr. Mendez is a composite of these dedicated professionals, presented here as a single school counselor to offer the most illuminating example possible. We offer Mr. Mendez’s story as a model of the thought processes a school counselor uses in applying UbD to classroom guidance curriculum design, recognizing that the specific mission or structure of school counseling programs may vary in diverse contexts.

Case Study of Classroom Guidance Curriculum Development

Mr. Mendez is the only school counselor at his middle school. When he described his interest in strengthening his classroom guidance curriculum to another teacher, his colleague shared an article on UbD with him. He decided to use its principles to revise his curriculum. Mr. Mendez sees each class in his school once per month (nine times per year) for a 60-minute block. Because he only delivers classroom guidance lessons to each class nine times, he designates three lessons for each of the three domains – social and emotional, academic, and career development (ASCA, 2012). He considers each set of three lessons in the same domain to be one unit. In the past, the three lessons in each unit were not cohesive, or not tied together with common ideas and related skills. Instead, he taught lessons on topics he thought would interest the students. These lessons were usually based on exercises he learned in his counselor education program, a few lesson plans his predecessor left behind, and activities he found on the internet.

Strengthening the Curriculum Across a Whole Program and Whole Grade Level

Mr. Mendez decided to begin the revision process by looking at ASCA’s (2014) Mindsets & Behaviors for Student Success: K–12 College- and Career-Readiness Standards for Every Student and broadly considering how the mindsets and behaviors apply to his classroom guidance curriculum across all three grade levels. In the past, Mr. Mendez had always listed mindsets and behaviors from this document at the top of his lesson plans. However, he had added this information to the lesson plan after he wrote it based on what students were doing in that day’s activity, rather than using the standards as starting points and considering them to be destinations for student learning. As he read over the document, he first considered whether the standards sounded like any form of UbD learning goals (see Table 1). He noticed the mindsets reflected some “big ideas” of school counseling programs, while the behaviors sounded more like broad transfer goals.

Unpacking the mindsets. Mr. Mendez had copied and pasted the mindsets into lesson plans many times, but he decided to deconstruct or “unpack” them now in greater depth. He began by looking for the key concepts reflected in each mindset. Although he noted several concepts in every mindset, he decided to focus on the concept he felt was the most critical for middle schoolers in each one. He listed out: balance (M1), self-confidence (M2), belonging (M3), life-long learning (M4), fullest potential (M5), and attitude (M6; ASCA, 2014). Next, he noted how frequently the concept of success was reflected in these mindsets. As he thought about his school counseling program’s mission, he recognized that supporting students’ short- and long-term success, which has many different definitions, was his program’s overarching goal.

Concept mapping. After identifying these six key concepts of success, Mr. Mendez decided to draw a concept map to think more deeply about the connections among them (see Figure 1). He wrote the concept of success on one side of the map and then considered the relationships between that idea and the other key concepts he identified. After he drew arrows between them, he wrote phrases related to the language of the mindsets along each of the arrows to explain the connections between the ideas. Although Mr. Mendez had previously held a general idea of these connections, making the ideas explicit through this exercise forced him to think more clearly about how each of the mindsets led students directly toward success. Although he found this process to be a bit mentally taxing, he spurred this work on by asking himself, If I can’t articulate these connections clearly for myself, how can I expect my instruction to reflect them clearly—or my students to really understand them? This process of concept mapping led Mr. Mendez directly to writing understandings that applied to all grade levels of his classroom guidance program. He crafted an understanding for each of the six mindsets and then added a seventh understanding because he wanted one that focused specifically on the individualized meanings of success. After he had written the understandings, he wrote essential questions to go along with each one (see Table 2).

Big idea design principles. In writing understandings and essential questions for his whole program, Mr. Mendez kept three design principles in mind by asking himself a series of questions: Who are my students? Which ideas are relevant to all of my diverse students at this developmental level in the context of my school? How can these ideas be worded in student-friendly language, so that students will understand and internalize these statements? Do the understandings and essential questions work together as matching pairs? and Do they include the same key concepts and reflect similar ideas?

Mr. Mendez then shifted his focus from thinking about his classroom guidance program as a whole to thinking about what students learned at each grade level. He used the ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors: Program Planning Tool (ASCA, 2003) to clarify which mindsets (with corresponding understandings and essential questions) he would target at which grade level. For example, he confirmed that the sixth-grade classroom guidance curriculum would focus on M3/U3/EQ3 in the social and emotional development unit, M2/U2/EQ2 in the academic development unit, and M4/U4/EQ4 in the careers unit (see Table 2).

Figure 1.

Note. Adapted from template developed by McTighe and Wiggins (2004, pp. 112–113). Although the word “potential” did not appear in mindset 5 (ASCA, 2014), Mr. Mendez added this word to “fullest,” because it was a phrase he used often with students, and it seemed to be implied in M5.

Unpacking the behaviors. Mr. Mendez turned his attention next to the behaviors outlined in ASCA’s (2014) Mindsets & Behaviors for Student Success: K–12 College- and Career-Readiness Standards for Every Student. As he reviewed the learning strategies, self-management skills, and social skills and compared them to the definitions of different types of UbD learning goals, he recognized these behaviors sounded like long-term transfer goals (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011). He noted that for students to learn and ultimately enact them, the behaviors would need to be further broken down into specific, assessable skills to practice.

For example, as he considered “Demonstrate ability to overcome barriers to learning (B-SMS 6)” (ASCA, 2014, p. 2), he broke this transfer goal down into five skills. To accomplish this broader behavior, students must be able to: identify a specific barrier to learning; access resources with information on strategies for overcoming the barrier; develop a plan of action to overcome the barrier based on gathered information; use strategies from a plan of action to overcome the barrier; and evaluate progress on overcoming the barrier and adjust strategies as needed.

Mr. Mendez recognized that he often unpacked the behavior standards into more specific skills during conversations with students in individual and group counseling about how to achieve a behavior, but he had never thought through how students might practice these skills in classroom guidance. He decided he would unpack each of the behaviors into more specific skills later and would shift his focus from thinking broadly about the whole sixth-grade curriculum to redesigning individual units.

Table 2

| ASCA Mindset Standards |

Understandings |

Essential Questions |

| M1: Belief in development of whole self, including a healthy balance of mental, social/emotional, and physical well-being |

U1: Success demands that I grow every part of myself by making choices that balance my mental, social/emotional, and physical well-being.

|

EQ1: How do I make choices to balance different parts of my well-being at the same time?

|

| M2: Self-confidence in ability to succeed

|

U2: I work to maintain my self-confidence in my ability to succeed.

|

EQ2: How do I keep my self-confidence up when I fail? |

| M3: Sense of belonging in the school environment |

U3: I belong in this school, which is here to help me succeed.

|

EQ3: How do I help myself and my classmates feel like we belong here? |

| M4: Understanding that postsecondary education and life-long learning are necessary for long-term career success |

U4: I must be a life-long learner to succeed in a career. |

EQ4: Why doesn’t learning end when school ends?

|

| M5: Belief in using abilities to their fullest to achieve high-quality results and outcomes

|

U5: Success requires me to use my abilities to their fullest potential. |

EQ5: How can I stay motivated to use my abilities to their fullest potential, even when I don’t feel like it? |

| M6: Positive attitude toward work and learning |

U6: A positive attitude toward my work and my learning supports my success.

|

EQ6: How does my attitude affect my success in obvious and in hidden ways?

|

|

U7: I am capable of deciding what my own success will look like—and of achieving that success. |

EQ7: What does success mean to me—today? Throughout school? Throughout life? |

Note. Mindset standards are quoted directly from ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors for Student Success: K–12 College- and Career-Readiness Standards for Every Student, by the American School Counselor Association, p. 1. Copyright 2014 by the American School Counselor Association. Mr. Mendez bolded the key concepts in each understanding and essential question to remind himself of the focus of every statement.

Next, Mr. Mendez returned to the ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors: Program Planning Tool (ASCA, 2003) to clarify which behaviors, or transfer goals, he would target in different domains at which grade level. During this process, he kept in mind which mindsets (with corresponding understandings and essential questions) he had already decided to target at each grade level, and he selected behaviors for that grade level to go along with those mindsets. For example, because he had selected M3/U3/EQ3 (see Table 2) to target in his sixth-grade social/emotional unit, he selected related behaviors such as “B-SS 2: Create positive and supportive relationships with other students” and “B-SS 4: Demonstrate empathy” (ASCA, 2014, p. 2) to teach in sixth grade as well.

Strengthening the Curriculum at the Unit Level

At this stage, Mr. Mendez turned his attention to redesigning one unit. He picked his first unit in sixth grade—the social and emotional unit—for this work. He called the unit “Belonging in Middle School.” This was the first classroom guidance unit students would experience in middle school, and he wanted it to offer support for their transition from elementary school. Mr. Mendez felt that, in the past, the three lessons he had taught for this unit did not reflect a cohesive big idea, and he had picked activities because students might enjoy them, not because they were aligned to strong learning goals. He decided to use the three-stage backward design process to strengthen the unit by writing a one-page “unit plan.” He also decided to mentally put aside the activities he had used in this unit in the past as he did this redesign work. He thought this might help him avoid the problem of activity-oriented design and not be constrained by what he had done previously.

Stage 1. Mr. Mendez began by documenting the six components of Stage 1 in his unit plan (see Appendix A). He had already identified most of the learning goals when thinking through his whole sixth-grade curriculum. He knew this unit would focus on ASCA standards M3, B-SS 2, and B-SS 4. He considered the behavior standards to be transfer goals, and he had already written an understanding and essential question corresponding to M3. This meant he only needed to identify the specific knowledge and skill goals for this unit that would help students explore the big ideas developed from the mindset standard and achieve the transfer goals from the behavior standards.

Skills. To begin this process, Mr. Mendez decided to write his skill goals. He looked again at the transfer goal presented in B-SS 2: “Create positive and supportive relationships with other students” (ASCA, 2014, p. 2) and asked himself: Which specific skills must students be able to do to accomplish this? He decided the first skill underlying this transfer goal was classifying relationships with others as positive and supportive or negative and unsupportive (D1 in Appendix A). He reasoned that, before working on creating positive relationships, students needed to distinguish between such relationships and those that would not be supportive of success in middle school. Mr. Mendez then identified additional skills related to creating such relationships with peers: listening actively, interpreting others’ verbal and non-verbal cues about their feelings, and communicating one’s own feelings verbally and non-verbally (D2, D3, D4).

Next, Mr. Mendez considered the meaning of B-SS 4: “Demonstrate empathy” (ASCA, 2014, p. 2). He decided a key related skill was being able to analyze others’ perspectives to understand their feelings and actions (D5). Additionally, he noted that three skills he wrote with B-SS 2 in mind—D2, D3, and D4—also applied to this transfer goal about demonstrating empathy.

At the end of this process, Mr. Mendez had described five clear and specific skills students would need to practice in this unit to ultimately achieve the transfer goals, and these skills also connected to the unit’s understanding and essential question about belonging in middle school. He recognized that when he taught this unit in the past, students had not practiced these specific skills as ways to increase a sense of belonging in themselves and their peers through creating positive relationships. Similarly, he had not assessed these skills to determine whether his lessons were actually moving students closer to the goals of the ASCA standards.

Knowledge. Last, Mr. Mendez identified several pieces of factual knowledge students would need to know in the unit. To decide this, he asked himself: What knowledge must students have to do the skills and to meaningfully explore the understanding and essential question? For example, he recognized that students would not be able to classify a given relationship as supportive or unsupportive (D1) if they did not already know the characteristics of supportive and unsupportive relationships (K1, K2 in Appendix A). Likewise, students could not meaningfully analyze others’ perspectives (D5) if they did not know the meaning of the word perspective (K3).

One challenge Mr. Mendez faced in developing knowledge and skill goals was that he could think of a long list of facts or skills students might encounter or use at some point during the unit. Rather than capturing all of these as unit goals, he used two questions to keep his thinking focused: Does this knowledge or skill reflect new learning that I will explicitly teach and assess in this unit (McTighe & Wiggins, 2015)? and Does this knowledge or skill reflect what is essential for students to learn to support my program’s transfer goals and big ideas, not just what would be nice to learn if we had no time constraints (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005)? If the answer to either question was no, he did not include that knowledge or skill as a unit goal.

Stage 2. To develop Stage 2, Mr. Mendez reflected on the most illuminating evidence he could collect from students to determine their proficiency with the unit goals after they completed the key learning experiences (see Appendix A). He decided the best way for students to demonstrate their proficiency with skills like active listening (D2), interpreting others’ verbal and non-verbal cues about their feelings (D3), and communicating feelings to others verbally and non-verbally (D4) was to enact conversations through role plays in which they practiced the skills. He decided students would do this as the key learning activity in Lesson 3, and they would then complete a written reflection as his main unit assessment. Specific reflection questions would prompt students to reveal their understanding of the unit’s big ideas, recall of the unit’s knowledge, and proficiency with the unit’s skills. Mr. Mendez would have students answer similar questions on a pre-assessment so he could evaluate student growth over time.

Stage 3. For the last stage of the unit plan (see Appendix A), Mr. Mendez thought broadly about how students could (a) gain proficiency with the unit goals in Stage 1 and (b) prepare to participate meaningfully in the role play and respond comprehensively to the written reflection prompts in Stage 2. He was particularly keen to ensure each of the Stage 1 unit goals would be taught and practiced in depth in at least one lesson’s learning activities. To avoid the problem of activity-oriented design, Mr. Mendez asked himself, What experiences do my students need to have in this unit to achieve my goals? rather than What activities would be fun?

As he reviewed his unit goals again, he decided that the most effective learning plan would include a sequence of experiences involving student self-analysis, case study analysis, and role play. To ensure every unit goal would be targeted in at least one lesson, he identified in Stage 3 the goals to which each lesson aligned (see Appendix A). He also considered the methods of assessment he would use to gather data about student learning during or after each learning experience, such as collecting completed handouts, listening to student comments, and giving short exit cards.

Mr. Mendez found it useful to think about the learning experiences of all three lessons in this unit at the same time when he designed the unit plan. He knew he would develop these ideas further in individual lesson plans, but it was beneficial to consider at the unit level how key learning experiences across the three lessons all aligned to his learning goals and comprised a cohesive, purposeful learning sequence.

Strengthening the Curriculum at the Lesson Level

After he had completed the unit plan for Belonging in Middle School and understood how his lessons would work together to achieve the unit goals, Mr. Mendez revised his three individual lesson plans. He liked using the ASCA (n.d.) Lesson Plan Template and decided that from now on, when he listed learning goals on lesson plans, he would simply copy and paste the goals from his unit plan that he was targeting in that lesson as the learning objectives. He would also copy goal labels (e.g., U1, EQ1, K2, D3) to remind himself which type of UbD goal each one reflected. As Mr. Mendez considered the learning activities he had previously used in this unit, he realized he would still be able to use many of those activities with minor revisions.

Lesson 1. In Lesson 1, Mr. Mendez could still have students complete an activity from past years in which they worked in small groups to generate lists of characteristics of positive and supportive versus negative and unsupportive relationships with peers. However, in the past, he had not connected that activity to any big ideas about the concept of belonging.

This year, Mr. Mendez would begin the lesson by posing the essential question to students as a critical question they would be answering for themselves during the first three months of school. As a warm-up, he would ask them to independently consider answers to the essential question, reflect on the challenges of building feelings of belonging in a new school, and identify a few strategies for helping themselves feel that they belong in middle school. Next, students would complete a brief activity to identify characteristics of supportive or unsupportive peer relationships in small groups. Mr. Mendez would then lead a short whole-class discussion in which he described typical sixth-grade peer relationships and asked students to classify them as supportive or unsupportive based on the characteristics their group listed. He also would discuss how building positive and supportive relationships with peers can be a key strategy for encouraging your own feelings of belonging. At the end of the lesson, students would work in small groups to develop a one-page handout for next year’s incoming sixth graders with strategies for helping them feel like they belong in the middle school, including building supportive peer relationships.

Lesson 2. For Lesson 2, Mr. Mendez decided he would continue to use activities he had used in the past. He would begin the lesson by teaching students the definition of the term empathy and asking students to share with a partner an example of a time they felt empathy for a peer. He would then explain they were going to watch Life Vest Inside’s (2011) “Kindness Boomerang” video in which a series of people are kind to others out of empathy. Next students would work in small groups to identify their three favorite examples of empathy in the video, the feelings of each receiver of empathy, and possible reasons the receiver felt that way.

Mr. Mendez would segue into the main activity by reminding students of the unit’s essential question and explaining that demonstrating empathy is a key way to help classmates feel like they belong. He would explain that at the core of empathy is the ability to see others’ perspectives to understand their feelings and actions, and that students would practice this skill through two case studies of fictional incoming sixth graders. After defining the term perspective, he would then show two brief videos to introduce the case studies: Daniel, a boy with a prosthetic arm (Siemens, 2012), and Amira, a Muslim girl who planned to join the girls’ basketball team and wear a different uniform that accommodated her religious beliefs (Associated Press, 2015).

Students would then work in small groups to identify Daniel’s and Amira’s perspectives as students who might appear different from their peers, including how they might feel about coming to a new school and act in response to those feelings. Next, Mr. Mendez would lead a group discussion about how feelings of empathy might arise in ourselves from understanding Daniel’s and Amira’s perspectives, and how empathy is different from pity. Last, each small group would create a list of verbal and non-verbal ways a supportive peer could communicate their empathy and a list of verbal and non-verbal ways an unsupportive peer might communicate a lack of empathy.

Lesson 3. Mr. Mendez did not plan to incorporate any activities he had used before into Lesson 3. This was because, after developing four specific skill goals based on B-SS 4: “Demonstrate empathy,” he realized he had not actually provided opportunities in the past for students to practice the skills that underlie demonstrating empathy. Now that he had these skill goals (D2, D3, D4, D5) clearly in mind, he wanted this unit to prompt students to use them authentically. Because students practiced D5 directly in Lesson 2, he focused on D2, D3, and D4 in Lesson 3—listening actively, interpreting others’ verbal and non-verbal cues about their feelings, and communicating one’s own feelings verbally and non-verbally. It seemed the best way to do this was through role play (see Appendix B for lesson plan).

Because Mr. Mendez only sees each class once a month, he planned to begin this lesson by showing the videos of Daniel and Amira again. However, this time, he would prompt the students to look for four “cues” about how their new classmates were feeling: (a) the words they used, (b) their tone of voice, (c) their body language, and (d) their facial expressions. He would pause the videos when Daniel describes “stuff I can’t do” and Amira says “I don’t want to look weird” so students could examine cues and jot down notes about what they see. Mr. Mendez would encourage students to hunt for more subtle cues and to focus on recording what they actually observed without judgment or criticism. He would then have students share what they observed in their same small groups from Lesson 2 and have each group share their common conclusions with the class.

Next, Mr. Mendez would ask each small group to review the lists they made in Lesson 2 of the ways a supportive peer would communicate empathy appropriately and the ways an unsupportive peer might communicate a lack of empathy. He would explain that they would be doing a role play with a partner in which one person would be Daniel (or Daniela) and the second would be himself or herself. Then, the partners would switch; the second person would be Amira (or Amir) and the first would be himself or herself. During the role play, the person playing Daniel or Amira would repeat what was said in the videos. The person playing themselves would listen actively, interpret verbal and non-verbal cues, and communicate empathy verbally and non-verbally.

After explaining these instructions, in preparation for the role play, Mr. Mendez would have students brainstorm ideas about what it means to listen actively. Then students would watch the videos of Daniel and Amira again—imagining these new classmates were present in the room—and practice active listening. Last, Mr. Mendez would lead a brief discussion about how, just as others give cues about their feelings through their words, tone of voice, body language, and facial expressions, we also communicate our own feelings like empathy in those four ways.

Students would then break into pairs and role play. After completing the role play, students would give each other feedback. In the round in which they played themselves, students would tell their partner how they interpreted the cues they saw in their partner’s word choice, tone of voice, body language, or facial expressions that let them know how their partner was feeling. In the round in which they played Daniel or Amira, students would tell their partner how they saw them actively listening and communicating empathy. Mr. Mendez would then lead a short whole-class discussion about how communicating empathy to Daniel and Amira could help these students feel they belonged at school. He would re-pose the essential question of the unit and ask students to reflect individually on how their answers to the question had changed from Lesson 1.

Overall, Mr. Mendez was pleased with his curriculum redesign process guided by UbD. He felt he now had strong clarity, not only about the purpose of individual lessons he taught, but also about the larger purpose of his classroom guidance program.

Conclusion

Although this article presented extensive detail about one school counselor’s curriculum development process, we must repeat that Mr. Mendez’s process—and UbD in general—should not be considered a recipe or prescription. A key strength of this model is that it provides a clear, step-by-step structure for curriculum design, while still offering flexibility in how it is applied. UbD should feel like a helpful set of guiding principles, not a straightjacket. We acknowledge that reading about Mr. Mendez’s work may raise concerns for school counselors who feel they do not have adequate time to redesign their classroom guidance curriculum at the “big picture” level in light of the competing demands of their schedules, or who feel overwhelmed by the decision-making involved in this process if they are the only school counselor for their school or grade level. We offer three suggestions in response to these challenges.

First, we suggest setting manageable goals for curriculum design work if fully redesigning a classroom guidance program at one time is not feasible. For example, one elementary school counselor we know developed a 3-year plan for redesigning her curriculum using UbD. She spent one summer unpacking the ASCA mindsets and behaviors, identifying the big ideas for her program, and identifying which big ideas, mindsets, and behaviors would be addressed at each grade level. For the following three school years, she then worked on revising the classroom guidance curriculum for two grade levels each year. In doing so, she kept most of the lessons she already used in each grade, but added new elements to those lessons so that learning activities would better align with the larger goals of her program, such as revisiting essential questions during lesson introductions and conclusions.

Our second and third suggestions come from the work of Lopez and Mason (2018), whose recent study identified the elements of highly effective classroom guidance lessons and suggested such lessons may not be common. The authors recommended that school counselors attend their school’s or district’s professional development trainings for teachers on best practices in lesson design and curriculum development. They also noted that school counselors who have previous experience as teachers may be “ideal resources” (Lopez & Mason, 2018, p. 9) for school counselors without this experience; identifying such colleagues who can answer questions and provide guidance on curriculum redesign work may provide constructive support during this process.

We suggest that future research should qualitatively examine the experiences of school counselors who work to strengthen their classroom guidance curriculum. In addition, quasi-experimental research might compare outcomes for students who have experienced a classroom guidance curriculum designed with UbD versus more traditional approaches. Such research could inform those who offer professional development on these topics, as well as counselor educators who seek to prepare school counselors effectively for this component of their future work.

We conclude with several parting thoughts about how this article’s contents might apply to different contexts. Mr. Mendez’s redesign work should not be interpreted as a call for school counselors to scrap curriculum that is working and start over. Rather, we encourage school counselors to further strengthen what is already effective in their classroom guidance curriculum by applying UbD principles and redesigning components that are not aligned to clear, robust goals. School counselors should also recognize that they do not need to follow the curriculum development steps in the same order as Mr. Mendez. If they prefer retaining an existing activity with the potential to build mindsets and behaviors, school counselors can unpack the big ideas underlying the activity or the knowledge and skills the activity teaches. However, school counselors should not be so tied to existing activities that they are unwilling to discard activities that are not aligned to powerful learning goals or will not lead to meaningful long-term transfer.

School counselors can use Mr. Mendez’s process with any state standards in addition to the national ASCA standards explored here; they would use the same process of identifying the key concepts in state standards and writing specific statements about the big ideas that underlie them. The ASCA standards also can be unpacked into understandings and essential questions other than the ones Mr. Mendez wrote. They may vary depending on the concepts the school counselor focuses on, whether the big ideas must capture ideas presented in other standards or a school’s mission statement, and who the students are, including their developmental levels.

Last, we emphasize that developing a classroom guidance curriculum is about the long-term outcomes school counselors want for their students. Mr. Mendez identified the concept of success as the unifying concept for his long-term goals. He therefore used that concept as a lens through which he made all curricular decisions, and he connected all of his transfer goals and big ideas to his program’s broader goal of making his students successful in school and careers. But other school counselors might see their programs’ long-term goals through different lenses. What matters is that a school counselor has clarity about those long-term outcomes and develops goals that match them. As counselor and teacher educators guiding our own students through this work, we often ask: If you don’t know where you’re going, how can you know if you’ve arrived? The key to high-quality classroom guidance is knowing the desired destination for students and making strategic curricular decisions to move students forward to that clear destination.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American School Counselor Association. (n.d.). Lesson plan template. Retrieved from www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/ASCA%20National%20Model%20Templates/LessonPlanTemplate.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2003). ASCA mindsets & behaviors: Program planning tool. Retrieved from www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/ASCA%20National%20Model%20Templates/M-BProgramPlanningTool.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2012). ASCA National Model: A framework for school counseling programs (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

American School Counselor Association. (2014). Mindsets & behaviors for student success: K–12 college- and career-readiness standards for every student. Retrieved from https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/home/MindsetsBehaviors.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2016). ASCA SCENE. Retrieved from https://scene.schoolcounselor.org/home

Associated Press. (2015, June 30). Muslim girls design modest sportswear. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=63&v=pA7JQonL-TE

Bardhoshi, G., Duncan, K., & Erford, B. T. (2018). Effect of a specialized classroom counseling intervention on increasing self-efficacy among first-grade rural students. Professional School Counseling, 21, 12–25. doi:10.5330/1096-2409-21.1.12

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards/

Desmond, K. J., West, J. D., & Bubenzer, D. L. (2007). Enriching the profession of school counselling by mentoring novice school counsellors without teaching experience. Guidance & Counseling, 21, 174–183.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston, MA: D.C. Heath and Co.

Gagné, R. (1977). Conditions of learning (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London, UK: Routledge.

Life Vest Inside (Producer). (2011). Kindness boomerang. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nwAYpLVyeFU

Lopez, C. J., & Mason, E. C. M. (2018). School counselors as curricular leaders: A content analysis of ASCA lesson plans. Professional School Counseling, 21, 1–12. doi:10.1177/2156759X18773277

Mager, R. (1988). Making instruction work: Or skillbloomers (2nd ed.). Atlanta, GA: CEP Press.

McTighe, J., & Seif, E. (2003). Teaching for meaning and understanding: A summary of underlying theory and research. Pennsylvania Educational Leadership, 24, 6–14.

McTighe, J., & Wiggins, G. (2004). Understanding by design: Professional development workbook. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

McTighe, J., & Wiggins, G. (2013). Essential questions: Opening doors to student understanding. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

McTighe, J., & Wiggins, G. (2015). Solving 25 problems in unit design: How do I refine my units to enhance student learning? (ASCD Arias). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

National Research Council. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school (Expanded ed.). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Schmidt, W., Houang, R., & Cogan, L. (2004). A coherent curriculum: The case of mathematics. Journal of Direct Instruction, 4, 13–28.

Schmidt, W. H., McKnight, C. C., & Raizen, S. A. (1997). A splintered vision: An investigation of U.S. science and mathematics education. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Senk, S. L., & Thompson, D. R. (2003). Standards-based school mathematics curricula: What are they? What do students learn? Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Siemens (Producer). (2012, September 10). The helping hand. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.

youtube.com/watch?v=9X-_EEIhurg

Sink, C. A., & Stroh, H. R. (2003). Raising achievement test scores of early elementary school students through comprehensive school counseling programs. Professional School Counseling, 6, 350–364.

Spady, W. G. (1994). Outcome-based education: Critical issues and answers. Arlington, VA: American Association of School Administrators.

Taba, H. (1962). Curriculum development: Theory and practice. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Tyler, R. W. (1948). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Vernon, A. (2010). Counseling children and adolescents (4th ed.). Denver, CO: Love.

Villalba, J. A., & Myers, J. E. (2008). Effectiveness of wellness-based classroom guidance in elementary school settings: A pilot study. Journal of School Counseling, 6(9), 1–31.

Weiss, I. R., Pasley, J. D., Smith, P. S., Banilower, E. R., & Heck, D. J. (2003). Looking inside the classroom: A study of K–12 mathematics and science education in the United States. Chapel Hill, NC: Horizon Research.

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2011). The understanding by design guide to creating high-quality units. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why don’t students like school? A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Willis, J. (2006). Research-based strategies to ignite student learning. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Hilary Dack is an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Clare Merlin-Knoblich, NCC, is an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Correspondence can be addressed to Hilary Dack, Department of MDSK, Cato College of Education, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 9201 University City Blvd., Charlotte, NC 28223, hdack@uncc.edu.

Appendix A

Unit Plan for “Belonging in Middle School”

(Template adapted from McTighe & Wiggins, 2004, p. 13; Wiggins & McTighe, 2011 pp. 16–17)

| Stage 1—Unit Learning Goals (Desired Results of Unit) |

| PRE-ESTABLISHED GOALS (ASCA, 2014)

M3: Sense of belonging in the school environment

B-SS 2: Create positive and supportive relationships with other students

B-SS 4: Demonstrate empathy |

| TRANSFER

In the long-term, students will be able to independently use their learning to…

create positive and supportive relationships with other students. (B-SS2)

demonstrate empathy. (B-SS4) |

| UNDERSTANDINGS (Us)

Students will understand that…

U3: I belong in this school, which is here to help me succeed. (M3) |

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS (EQs)

Students will keep considering…

EQ3: how do I help myself and my classmates feel like we belong here? |

| KNOWLEDGE (Ks)

Students will know…

K1: characteristics of positive/supportive relationships

K2: characteristics of negative/unsupportive relationships

K3: definitions of vocabulary terms: perspective and empathy |

SKILLS (Ds—what students must be able to Do)

Students will be able to…

D1: classify relationships with others as positive/supportive or negative/unsupportive based on their characteristics (B-SS 2)

D2: listen actively to show respect and gain information about others (B-SS 2, B-SS 4)

D3: interpret cues such as word choice, tone of voice, body language, and facial expressions to identify feelings of others (B-SS 2, B-SS 4)

D4: communicate feelings to others using word choice, tone of voice, body language, and facial expressions (B-SS 2, B-SS 4)

D5: analyze others’ perspectives to understand their feelings and actions (B-SS 4) |

| Stage 2—Unit Assessment Evidence |

| Role play in Lesson 3 followed by written reflection with questions prompting students to explain:

New strategies learned in unit for helping themselves feel like they belong (U1, EQ1)

New strategies learned in unit for helping others feel like they belong (U1, EQ1)

Examples of positive/supportive and negative/unsupportive peer relationships based on the relationships’ characteristics (K1, K2, D1)

Examples of how they listened actively, interpreted cues, communicated feelings, and analyzed another’s perspective in role play—and possible effects of those approaches on their partner’s sense of belonging (K3, D2, D3, D4, D5) |

| Stage 3—Unit Learning Plan |

| Lesson 1: Self-analysis—past examples of: belonging and not belonging; positive and negative relationships; building feelings of belonging in new context through positive peer relationships (U1, EQ1, K1, K2, D1)

Lesson 2: Case studies—analyze two new classmates’ perspectives, reflect on strategies for building and expressing empathy for classmates (U1, EQ1, K3, D4, D5)

Lesson 3: Role play—take turns portraying fictional classmate from one case study and building positive relationship with classmate to support sense of belonging (U1, EQ1, D2, D3, D4) |

Appendix B

Lesson Plan for Lesson 3 in “Belonging in Middle School” Unit

(Template from ASCA, 2018)

Lesson Plan Template

Activity: Belonging Role Play

Grade(s): 6

ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors:

M3: Sense of belonging in the school environment

B-SS 2: Create positive and supportive relationships with other students

Learning Goal(s):

U3: I belong in this school, which is here to help me succeed.

EQ3: How do I help myself and my classmates feel like they belong here?

D2: Listen actively to show respect and gain information

D3: Interpret cues such as word choice, tone of voice, body language, and facial expressions to identify feelings of others

D4: Communicate feelings to others using word choice, tone of voice, body language, and facial expressions

Materials:

Small white board and marker for each small group

Helping Hand video (Daniel) at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9X-_EEIhurg (play 0:00–3:10)

Muslim Girls Design Modest Sportswear video (Amira) at https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_

continue=63&v=pA7JQonL-TE (play 0:00–1:00)

Procedure:

Show videos of Daniel and Amira. Students jot down notes on “cues” about how each is feeling: words, tone, body language, facial expressions. Students share what they found in same small groups from Lesson 2. Each group shares common conclusions with class.

Each group reviews lists made in Lesson 2 of verbal and non-verbal ways in which supportive or unsupportive peers communicate empathy or lack of empathy.

Explain instructions for Daniel and Amira role plays. (Student playing themselves must listen actively, interpret verbal and non-verbal cues, communicate empathy verbally and non-verbally.)

To prepare for role play, each group brainstorms ideas on white board about what it means to listen actively, and students watch videos of Daniel and Amira again to practice active listening.

Students break into pairs and role play a discussion as Daniel/a or Amir/a.

Partners give each other feedback on three key skills they practiced.

Lead whole-class discussion about how communicating empathy to Daniel and Amira as new students could help them feel they belong in the school.

Re-pose essential question. Ask students to reflect individually on how their answers changed from beginning of Lesson 1.

(Students complete written reflection as end-of-unit assessment.)

Plan for Evaluation: How will each of the following be collected?

Process Data: Document the number of times this lesson is delivered to sixth-grade classes and how many students receive the lesson in each class.

Perception Data: At the end of Lesson 3, distribute written reflection prompts assessing what students learned in the “Belonging in Middle School” unit:

Identify all the new strategies you learned in this unit for helping yourself feel like you belong at our school. (U1, EQ1)

Identify all the new strategies you learned in this unit for helping others feel like they belong at our school. (U1, EQ1)

In this unit, you learned that positive peer relationships can be supportive and negative peer relationships can be unsupportive for different reasons. (K1, K2, D1)

Give three examples of positive peer relationships that are supportive for different reasons. Explain why each one is supportive.

Give three examples of negative peer relationships that are unsupportive for different reasons. Explain why each one is unsupportive.

Think about your work in today’s role play when you played yourself (not Daniel or Amira). Give 4 specific examples of how you showed empathy by 1) actively listening, 2) interpreting your partner’s “cues”, 3) communicating your feelings, 4) analyzing your partner’s perspective. Next to each example, explain how that part of showing empathy helped Daniel or Amira feel like they belong at our school. (K3, D2, D3, D4, D5)

(At the beginning of Lesson 1, ask students similar questions to gather pre-assessment data. Compare pre-assessment responses to responses on end-of-unit written reflection.)

Outcome Data: Track student attendance, grades, and the number of behavioral referrals one month before this lesson, the month of the lesson, and in the three subsequent months to determine if the lesson’s impact on students’ sense of self-belonging is reflected in attendance, grades, and behavior.

Follow-Up: Check in with teachers to see if they observe any changes in student behaviors surrounding creating positive and supportive relationships with other students (B-SS 2) and demonstrating empathy (B-SS 4). Examine all assessment data from end-of-unit written reflections and determine if any concepts remained unclear to students. Schedule any necessary follow-up “mini-lessons” if some students lacked clarity about any concepts.

Jun 7, 2019 | Volume 9 - Issue 2

Jennifer Katz

Abortion is common, yet stigmatized. In some cases, abortion patients may experience feelings of sadness, guilt, anger, and other signs of emotional distress after their pregnancy is terminated. This article offers guidance for counselors seeking to provide nonjudgmental support to promote adaptation and recovery among abortion patients experiencing emotional distress. A brief summary of different ways to conceptualize emotional distress after abortion is provided. Next, a general cognitive behavioral framework is introduced, and common thought and behavioral patterns that may contribute to unresolved distress are explored. The article concludes with general recommendations to promote a respectful, collaborative alliance.

Keywords: abortion, abortion counseling, stigma, emotional distress, pregnancy

Abortion is a common medical procedure. An estimated one in four women in the United States will have an abortion by age 45 (Jones & Jerman, 2017). Although prevalent, abortion is highly stigmatized and politicized. Many people understand abortion in terms of the competing rights of the fetus (to live) and the person who is pregnant (to retain autonomy over one’s body and life). As such, legal abortion challenges conceptions of the nonviable embryo or fetus as having independent rights (Solinger, 2013). In the United States, abortion is more strictly regulated than any other medical procedure (Sanger, 2017), and these regulations contribute to a misperception that legal abortion is more medically dangerous than childbirth. Depending on state-specific regulations, abortion patients may be required to wait a certain amount of time after their initial clinic visit, to receive information about fetal development, or to observe fetal imagery before they are permitted to make final abortion care decisions (Sanger, 2017). Requirements like these imply that potential abortion patients are unlikely to make sound decisions without outside assistance (Norris et al., 2011), and also create different types of potential stressors depending on where a patient seeks abortion care.

Because abortion is so stigmatized, counselors and community members across many different settings (e.g., clinic volunteers, talk-line counselors) may encounter abortion patients experiencing distress after their procedures. This article offers guidance for both professional and paraprofessional counselors who are approached by a woman seeking support. The focus here is specifically on supporting a patient who has had a legal abortion procedure by a licensed health professional. Women seeking illegal abortions from unlicensed providers face additional physical and psychological risks that are beyond the scope of the current article.

Although different abortion patients will have different concerns, there are at least five general recommended aspects of after-abortion counseling (Needle & Walker, 2008). First, patients tend to disclose what happened, under what circumstances, and their broader social, medical, and family history. Second, a patient’s decision-making process and knowledge about the abortion procedure before and after it occurred warrant full exploration. Third, counselors can support emotional stability by accepting and exploring a patient’s feelings, including ambivalence as experienced both in the past and in the present. Fourth, spiritual and cultural issues can be addressed; these may include religious and familial values about abortion, parenting, and the concept of forgiveness. Finally, counselors can promote client self-care, potentially by identifying “safe” people to whom patients can disclose. When working within this broader framework, and while drawing upon best practices for pregnancy loss (e.g., Wenzel, 2017), a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) framework may help foster recovery. This article discusses (a) different ways to understand abortion-related distress, (b) concepts and methods from CBT that may help counselors support abortion patients, and (c) general recommendations for the respectful use of questions and language.

Understanding Emotional Distress After Abortion

Counselors may draw upon vastly different ways of understanding how and why abortion patients experience emotional distress after abortion. In the early 1990s, Vincent Rue proposed the existence of post-abortion syndrome (PAS), a variant of post-traumatic stress disorder. According to Speckhard and Rue (1993), “the trauma involved in being both attached to and responsible for the death of one’s fetal child can be emotionally overwhelming, and cause a range of symptoms” (p. 5). Symptoms of distress may manifest as guilt, self-directed blame and anger, sadness, intrusive thoughts about fetal death, and problematic family relationships, among others. Speckhard and Rue suggested that in some cases, distress may fluctuate with the menstrual cycle. In other cases, distress may remain dormant until patients experience subsequent reproductive events such as childbirth or menopause. Although some find PAS to be useful in conceptualizing cases, there have been longstanding debates about its validity (e.g., Dadlez & Andrews, 2010; Edwards, 2009). PAS has not been recognized as a formal medical or psychiatric diagnosis. Furthermore, PAS is often used in political contexts to argue against abortion rights and access (Dadlez & Andrews, 2010; Kelly, 2014). That is, “pro-life” activists use PAS to argue that potential abortion patients are likely to be emotionally harmed by abortion and therefore should be protected from making the decision to seek abortion.