Kylie P. Dotson-Blake, David Knox, Marty E. Zusman

Despite growing attention to the subject, a dearth of information exists regarding college students’ perceptions and process of meaning-making related to the act of oral sex. Such perspectives and allied social sexual scripts can have considerable consequences on the sexuality and sexual health of older teens and college-aged populations. The present research serves to elucidate such perspectives and presents a profile of college students’ degree of agreeing that oral sex is not sex. Over half (62.1%) of a sample of college students (N = 781) at a large southeastern university agreed that oral sex is not sex. Response rates across demographic groups are presented and factors that influence such perspectives are examined. Sexual script theory serves as the theoretical framework. Implications and limitations are explored.

Keywords: oral sex, social sexual scripts, college students, script theory, sexuality, sex counseling

Television talk show hosts, The Washington Post (Stepp, 2005) and Science Daily (University of California, San Francisco, 2005) have all had recent headlines related to oral sex in the older teen and college-aged populations. Because of these and other popular media sources, sex educators, parents and others have become more aware of oral sex engagement among college students and more concerned about the impacts of this engagement. Although society members are becoming concerned about this topic, limited information regarding college students’ perceptions and process of meaning-making related to the act of oral sex is available in the literature. To develop sexuality education curriculum and resources targeted at young people engaging in oral sex, professionals must first identify those most likely to engage in oral sex, their process of meaning-making around this engagement and risks young people are exposed to as a function of their engagement in oral sex.

In an effort to provide insight into this population’s process of meaning-making related to engagement in oral sex and initial information about characteristics of college students likely to engage in oral sex, this article presents the findings of a survey conducted at a large southeastern university. An initial profile of undergraduates who agreed with the statement “Oral Sex is Not Sex” is offered and findings are analyzed through the lens of social sexual script theory to explore the process of meaning-making related to the perceptions of participants regarding oral sex. We hope this information will assist sex educators, counselors, health professionals and parents in efforts to target individuals likely to engage in oral sex to minimize risks related to oral sex in the college student population. Thus, the purpose of this study was to provide a profile of undergraduates who agreed with the assertion that oral sex is not sex and to explore the links between participant responses and sexual scripts to illuminate fully how these participants perceived oral sex engagement. This profile is important because recent research suggests that young people perceive oral sex as safe, with few potential health risks (Halpern-Felsher, Cornell, Kropp, & Tschann, 2005). However, engaging in oral sex may expose individuals to the risk of viral and bacterial infections, including chlamydia, gonorrhea and herpes (Edwards & Carne, 1998a, 1998b). Consequently, it is critical that counselors fully understand the context and perceptions of college students in order to provide information to assist with healthy decision-making in developmentally-appropriate ways for these clients.

Theoretical Foundation

Sexual script theory situates perceptions of sexual interactions within the social context to explain how sexual identity and sexuality are shaped by social cultural messages (Frith & Kitzinger, 2001). Consequently, what is perceived to be “real” sex is defined by the society within which one exists, individual identity and socio-cultural normative sexual scripts. Sexual scripts vary across individuals, but often common elements exist within sexual scripts associated with particular cultural groups (Wiederman, 2005). As a social constructionist approach to exploring the development of sexuality, sexual script theory has been primarily used as a qualitative method of research (Simon & Gagnon, 2003). However, recent research has applied sexual script theory in quantitative research exploring the impact of exposure to sexually explicit material on young people (Stulhofer, Busko, & Landripet, 2010). For the study presented in this article, results were found using quantitative methods and then a qualitative exploration of themes that emerged from the quantitative data yielded links to sexual scripts postulated by sexual script theory.

Sexual Scripts and Heterocentric Standards

One sexual script prevalent in Western cultures, the traditional sexual script (Rostosky & Travis, 2000), serves to situate sexual intercourse between heterosexuals as real sex. This sexual script serves to disenfranchise sexual minorities by failing to recognize the full spectrum of sexual acts occurring between persons of any gender and the meanings attributed to these acts. Furthermore, not only is sex limited to heterosexual intercourse, but the concept fundamentally depends on male ejaculation since it is the male orgasm that denotes both the number of times a couple has sex and is the culmination (the climax) of sex (Frye, 1990). This phallocentric approach with regard to the concept of sex limits the power of women to be equal partners in a heterosexual relationship (Bhattacharyya, 2002). Consequently, these heterocentric standards for what qualifies as sex means that lesbians do not have real sex since lesbian sex does not involve penile penetration.

Within this sexual value system, vaginal-penile penetration/intercourse is at the apex of what constitutes sex, such that all other non-coital sexual practices/behaviors—such as oral sex—are considered foreplay and as a result have not been researched as fully and comprehensively as vaginal-penile penetration/intercourse. Much of sexual research has been situated within Western culture, resulting in the firm entrenchment of the traditional sexual script (Rostosky & Travis, 2000) within research methods and processes. This social entrenchment of heteronormative standards impacts the social sexual scripts college-aged individuals hold and apply in their sexual engagement (Bhattacharyya, 2002).

Peer groups have a strong influence on sexual behaviors, particularly among young adults. Peer group shifts in perceptions and values, when it comes to sex and sexual activity, will in turn impact sexual trends and patterns within peer groups. For college students, peer group perceptions powerfully impact individual perceptions and behaviors (Carter & McGoldrick, 1999). Prinstein, Meade, and Cohen (2003) discerned a positive relationship between young people’s reports of oral sex engagement and peer popularity. This suggests that peer culture for college students supports oral sex practice.

Peer group perceptions are formed within the context of the larger society and events, media and social issues within the society. One such societal event relevant to this discussion is the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal. At the heart of the scandal is Clinton’s famous utterance, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky” (Clinton, 1998). Whether his perception of oral sex as not real sex is due more to his personal perception based upon the traditional sexual script (Rostosky & Travis, 2000) or Clinton’s cunning sense of self-preservation will never be known. What is known, however, is that his statement and the subsequent maelstrom of controversy that ensued solidly asserted the question: “Is oral sex really sex?” into the public domain for debate.

Prevalence of Oral Sex Engagement in Young Adult and College-Age Population

In 2002, as part of the National Survey of Family Growth, 10,208 people ages 15–19 were included in the overall sample, and, of these respondents, more than half of males (55%) and females (54%) reported engaging in oral sex (Mosher, Chandra, & Jones, 2005). Richters, de Visser, Rissel, & Smith (2006) analyzed data from the Australian Study of Health and Relationships from a representative sample of 19,307 Australians aged 16 to 59 and found that almost a third (32%) of the respondents reported that oral sex was included in their last sexual encounter. Similarly, in a study of 212 participants ranging in age from 15 to 17, Prinstein, Meade, and Cohen (2003) reported that a third of the males and half of the females had engaged in oral sex in the past year. These studies reveal that many of the college-aged population are engaging in oral sex.

Oral Sex Scripts and Pop Culture

As dialogue about oral sex entered contemporary popular culture, it also became mainstreamed into the young adult vernacular and embedded into the tapestry of social mores and norms. Sexual script theory (Gagnon & Simon, 1973) emphasizes that social norms play a significant role in governing college students’ processes of meaning-making regarding health information and subsequent health and sexual behaviors. This theory holds at its foundation the understanding that sexuality is borne from cultural norms and messages that define what is deemed sex and socially-appropriate responses in sexual situations and encounters (Frith & Kitzinger, 2001).

In considering the impact of culturally-laden sexual norms and social sexual messages, one may infer that as oral sex has entered contemporary discourse, the social norms emerging from this discourse have impacted college students’ perceptions of and participation in oral sex. Understanding this process of social norm-belief-behavior interaction and possible consequences, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs), is critically important for sex educators, counselors and therapists working with the college-aged population, as these clients have intense levels of interactions with peers attuned to contemporary popular culture.

Young Adults and Sexually Transmitted Infections

Researchers also have found that young people are increasingly experiencing high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Prinstein, Meade, & Cohen, 2003). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2006), females who are 15–19 years of age reported the highest rates of all other demographic groups for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Of the 19 million STIs reported each year in the U.S., Weinstock, Berman, and Cates (2004) estimated that almost 50% occur in individuals who are 15–24 years of age. From these high rates of STIs in the young adult population, it can be inferred that more education around protection and safe sex engagement is necessary. Recent research has shown that young people also are concerned about the need for safety in sexual engagement and as such have turned to oral sex because they feel it presents fewer health risks (Halpern-Felsher, Cornell, Kropp, & Tschann, 2005). However, oral sex also presents risks of STIs. In a summary of research over more than 35 years regarding oral sex as a possible means of transmitting STIs, Edwards and Carne (1998a, 1998b) noted that oral sex may transmit viral and bacterial infections, including gonorrhea, chlamydia and herpes. Consequently, college students need to be educated about the risks of STI transmission through oral sex to minimize the harmful consequences.

The Need to Explore Perceptions of Oral Sex

In view of the various studies reporting the frequency and consequences of oral sex among young adults and college students, we emphasize the importance of educating this population about safe practices related to oral sex. A first step in this process is to assess the perceptions of this population in regard to oral sex. In short, though the research suggests that this population is engaging in oral sex (Prinstein, Meade, & Cohen, 2003), little is known about how they perceive the act and what meaning they attribute to the behavior in terms of their sense of self and sexual identity development. How do college students perceive oral sex? Do they perceive it to be real (i.e., intercourse) sex? How does it shape a young adult’s sense of self? Do college students feel that by engaging in oral sex and other non-coital behaviors that they are practicing a form of abstinence, that they are maintaining their virginity? Finding the answers to these questions may assist sex educators, counselors and therapists in developing comprehensive sexuality education programs incorporating resource awareness, prevention and health-focused knowledge for this population (Bay-Cheng, 2003).

In an effort to begin to address these questions and process, this article presents the findings of a study exploring the perceptions and behaviors of college students regarding oral sex. The purpose of the research was to identify a profile of undergraduates who agree with the assertion oral sex is not sex. This profile can be used to identify college students who may be more likely to engage in oral sex, allowing clinicians and educators to plan and implement developmentally-appropriate measures in contexts most likely to reach this population. An exploration of the intersection of social norms, utilizing sexual script theory, with characteristics prevalent in the profile that emerged will be discussed, as well as the implications and limitations of the study.

Sexual Script Theory and Perceptions of Oral Sex

By exploring research focused on oral sex engagement, the college-aged population and prevalent social sexual scripts, one may make significant inferences regarding this population’s perceptions of oral sex and process of meaning-making related to this sexual act. Again, it is important that the authors note that sexual scripts are based upon individual experience and social engagement and as such are impacted by the intersecting identity characteristics of individuals. Sexual scripts are reflective of culture and thus some elements will be common to members of the identified cultural group to which the script refers (Geer & Broussard, 1990). However, personal identity is multi-faceted and individuals belong to many different cultural groups by the nature of their race, ethnicity, religion, social class, sexual identity, education status, etc. Consequently, there may be wide variation in sexual scripts across individuals, even within a specific cultural group or sub-group (Wiederman, 2005).

Remaining cognizant of the diversity of sexual scripts across cultural groups, the authors will lead an exploration of selected dominant sexual scripts that may impact college-aged individual’s perceptions of and engagement in oral sex in the U.S. This exploration is not intended to be exhaustive; it is simply meant to serve as a foundation for understanding the potential of sexual scripts to impact these individuals’ processes of meaning-making related to oral sex. Finally, the authors recognize that sex extends far beyond penile penetration of a vagina. Unfortunately, the majority of research findings gleaned from a comprehensive review of the professional literature promote heteronormative standards by focusing solely on sex as the act of sexual intercourse between individuals of different genders. Consequently, the discussion of current professional research is limited in scope, indicating the need for additional research exploring the full range of sexual activities and sexual scripts impacting young adults and the college student population of any gender and sexuality.

Perception One: Oral Sex is Safe

The current professional literature suggests that young adults and college students articulate diverse reasons for engagement in oral sex. A reason that emerges dominantly from multiple studies is the perception that oral sex is safe with minimal risk and consequence (Halpern-Felsher et al., 2005; Remez, 2000). In a study of ninth-graders in California, participants were unlikely to use barrier protection when engaging in oral sex (Halpern-Felsher et al., 2005), indicating that they felt the practice of oral sex carried minimal risk for STIs. Possibly contributing to adolescent and teen perceptions of oral sex as safe are the sex education programs to which this population is exposed. Data suggest that abstinence-only and faith-based sex education programs do little to educate young adults on the very real and possible dangers associated with oral sex—i.e., the spread of STIs (Lindau, Tetteh, Kasza, & Gilliam, 2008). This lack of information may lead to the perception that because risks related to oral sex are not talked about, it must be safe. Surveys find that most young adults are misinformed, in that they are taught that STI risks are only associated with vaginal-penile intercourse. In sum, we surmise that these sex education programs, shifts in societal perceptions of and sexual scripts related to oral sex, and the use of oral sex as a substitute for intercourse may have a strong effect on the perceptions of the college age population reflecting that oral sex is safe sex.

Perception Two: Oral Sex Mitigates Religiosity and Sex Guilt Tension

Studies have shown strong correlations between degree of religiosity and patterns of sexual behavior. Kinsey, Pomeroy and Martin (1948, 1953) were some of the first to show empirically that religious identification limits sexual behaviors among the unmarried. Schulz, Bohrnstedt, Borgatta, and Evans (1977) also found that religiosity had a significant inhibiting effect on sexual behavior for both men and women. A study conducted by Wulf, Prentice, Hansum, Ferrar, and Spilka (1984) examined the sexual attitudes and behaviors among evangelical Christian singles, and found overall a more conservative outlook in sexual beliefs compared to the cultural norms. Of this group, those that were intrinsically faithful—that is, the more intensely religious who had a strong identification with traditional Christian values—and were not involved in a relationship, displayed the most conservative sexual attitudes. Among the more devout and single, the strongest correlations were found with respect to premarital intercourse and oral sex, in that these individuals were least likely to have engaged in these two activities.

Numerous studies have shown strong relationships between religiosity and sex guilt (Langston, 1973; Mosher & Cross, 1971). Those with conventional religious beliefs are more likely to have sex guilt, which in turn inhibits sexual behavior (Sack, Keller & Hinkle, 1984). Individuals with sex guilt are more absolutist in their orientations to sex and are less sexually active, since transgressing these strict sexual parameters might elicit intense displeasure and an antagonistic relationship with their religious community. By perceiving oral sex as not real sex, young adults and college students may be able to mitigate the tension between religious beliefs and sex guilt. For instance, a meta-analysis of studies looking at sexual attitudes and practices among young adults found that a majority believe oral sex to be less intimate compared to intercourse and that oral sex does not spoil virgin status (Remez, 2000). Many abstinence-only and faith based sex education programs now include a new push for virginity pledges, reinforcing the notion that vaginal intercourse is what is most at stake when it comes to preserving one’s virgin status.

Perception Three: Oral Sex Requires Less Commitment

Studies examining sexual attitudes and practices have found that sexual experience seems to be associated with a more liberal orientation to sex. This more liberal orientation to sex has been linked with “hooking up,” defined as having sex with someone one has just met (Richey, Knox, & Zusman, 2009). Paul, McManus, and Hayes (2000) examined the hookup culture within a college setting. They found that students high on impulsivity had a more noncommittal orientation with regard to relationships, displayed a high level of autonomy, and were much more likely to engage in both coital and non-coital hookups.

Social scripts are shared interpretations and have three functions: to define situations, name actors, and plot behaviors. For example, the social sexual script operative between two college students who are hooking up is to define the situation (a hookup, not a relationship where they will see each other tomorrow), name the actors (male and female college students out to meet someone for an evening of fun), and plot behaviors (go back to one’s dorm room or apartment, fool around, and not see each other again.). This hookup process leads to lessened intimacy and expectations for commitment in sexual encounters. Related to oral sex, findings (Halpern-Felsher et al., 2005) show that among teens and the college-aged population, oral sex is used as a substitute for vaginal-penile intercourse and as such may take the place of vaginal-penile intercourse in heterosexual hookup events. This perception of oral sex as less intimate by the college-aged population stands in contrast to perceptions of older adults, particularly older women, who view oral sex as equally intimate (or more so) to vaginal sex (Remez, 2000).

Perception Four: Oral Sex is Not Sex

The authors posit that each of the preceding sexual scripts is subsumed by an over-arching sexual script prevalent within the college-aged population: oral sex is not sex. By positioning oral sex as a less risky, less intimate sex practice that allows one to maintain his/her virginity with minimal religion-based sex guilt, the college-aged population may not identify oral sex as real sex. According to Remez (2000), peer culture socializes young adults to perceive oral sex as abstinence, allowing one to maintain and protect one’s virginity. Many factors related to contemporary social sexual scripts for oral sex support the assertion that the college-aged population does not identify oral sex as sex, including beliefs that oral sex does not impact their virgin status, is thought to be less dangerous, is less likely to lead to deterioration in the student’s reputation, and leads to less guilt than vaginal-penile penetration (Hollander, 2005).

All of the aforementioned sexual scripts contribute to the perceptions of college-aged individuals regarding oral sex. By raising awareness of the social sexual scripts, we hope to illuminate the process of meaning-making college-aged individuals attach to the act of oral sex. Further illumination of specific characteristics aligned with the over-arching social sexual script of oral sex is not sex will allow sex educators, counselors and others to target initiatives aimed at reducing risks related to oral sex in a more intentional, focused effort on individuals within the college-aged population who are most vulnerable to those risks.

Method

Sample

The data for this study were taken from a larger nonrandom sample of 781 undergraduates at a large southeastern university who answered a 100-item questionnaire (approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university) on “Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors of College Students.” Respondents completed the questionnaire anonymously (the researcher was not in the room when the questionnaire was completed and no identifying information or codes allowed the researcher to know the identity of the respondents). Listwise deletion was used to address issues of missing data and two participants were excluded from statistical calculations due to missing data.

Measures

The measure used to collect data was a 100-item survey developed by Knox and Zussman (2007): Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors of College Students. The survey was developed based on a review of the professional literature related to sexuality among undergraduates. For the purpose of this research, demographic characteristics including gender, race, age and class level and the survey domains of sexual practices, religious identification and sexual values were included in the analysis. Within the domain of sexual practices were items asking participants to respond to whether they have given or received oral sex. Items surveying participants’ perceptions of themselves as religious and their beliefs about the importance of marrying someone of their same religion were included in the domain of religious identification. The domain of sexual values included items asking participants to choose the sexual value of absolutism, relativism, or hedonism, that best described their sexual values, and items asking participants to indicate their willingness to have sex without love.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 17.0. Pearson product moment correlations and non-parametric statistics including cross-classification and Chi Squares were calculated to assess relationships among demographic characteristics and the selected domains. Following the quantitative analysis, themes within the results were explored through the lens of sexual script theory.

Results

Analysis of the data revealed several relationships that may be related to the dominant social sexual scripts affecting teen and college-aged individual’s engagement in oral sex. The majority of participants (62%) indicated their agreement with the statement that oral sex is not sex. In comparing the characteristics of those who agreed and disagreed, five statistically significant relationships emerged. Through statistical analysis of the responses, a profile of participants who asserted that oral sex is not sex emerged. Of the respondents, 76.4% were females and 25.4% were males. Racial background included 79.5% European American, 15.7% Blacks (respondent self-identified as African-American Black, African Black, or Caribbean Black), 1.9% Biracial, 1.7% Asian, and 1.3% Hispanic. The majority, (95%) of the sample identified as heterosexual, 2.9% identified as bisexual and 2% identified as homosexual. The mean age of the sample was 19 years-old.

Underclassmen-Freshmen & Sophomores

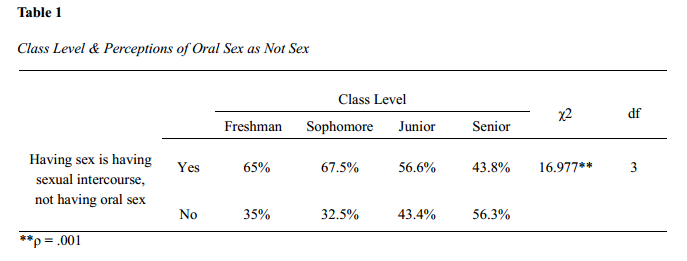

Freshmen and sophomores were the most likely to agree that oral sex does not take away one’s virginity, with the majority of freshmen and sophomores indicating their agreement that engaging in oral sex does not constitute having sex (see Table 1). Juniors and seniors were less likely than underclassmen to agree that oral sex is not having sex. Hence, there was a general pattern that the lower the class rank of the student, the more likely the student to hold the belief that he or she could have oral sex and remain a virgin.

European American

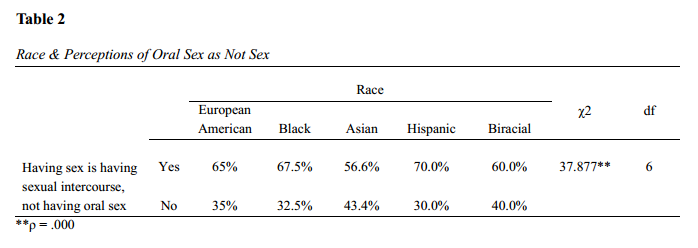

Race was significantly related to perceptions of oral sex as not being sex (see Table 2). European American undergraduates were more likely than Blacks (respondent self-identified as African-American Black, African Black, or Caribbean Black) to agree that oral sex is not sex. In this study, the limited number of Asian and Latino participants renders the data of minimal use, however 61.5% of Asian participants (N=13) and 70% of Hispanic participants (N=10) indicated that they agreed that oral sex is not sex.

Self-Identified as Religious

Students who noted that they considered themselves to be religious by indicating that they agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “I am a religious person,” were more likely to agree that oral sex is not sex than students who reported that they were not religious at all (61.3% vs. 14.3%). Participant responses revealed an inverse relationship between self-identification as “a religious person” and having never “given oral sex to a partner,” r(4) = -.121, p = .001, and having “never received oral sex,” r(4) = -.099, p = .006. An inverse relationship between perceptions of the importance of marrying someone with the same religious identification as oneself and giving and receiving oral sex respectively also was noted, r(4) = -.114, p = .001 and r(4) = -.129, p = .000. Participants who identified as religious were thus more likely to agree that oral sex is not sex and also indicated that they have engaged in oral sex.

Sexual Value

Given the alternative sexual values of relativism (“the appropriateness of intercourse depends on the nature of the relationship”), absolutism (“no intercourse before marriage”) and hedonism (“if it feels good, do it”), students who self-identified as hedonistic were more likely than those who viewed themselves as relativists and absolutists to agree that oral sex is not sex (65.8% vs. 62.9%, and 48.0%) (p < .05). Expressed another way, over 50% of absolutists compared to 34% of hedonists say the idea that one is still a virgin after having oral sex is not true. This 16% difference is striking. Participants who reported having engaged in sex without love also indicated they had engaged in both giving and receiving oral sex r(2) = -.229, p = .000, and r(2) = -.206, p =.000. These findings reflect that students who express more hedonistic perspectives are more likely to agree that oral sex is not sex and does not impact one’s status as a virgin.

Safe Sex Practices

A significant inverse relationship existed between participants who reported requiring the use of a condom before intercourse and never having given oral sex (r(4) = -.120, p = .001), and never having received oral sex (r(4) = -.092, p = .010). These findings indicate that the participants from this study who engaged in oral sex also used protective methods when engaging in intercourse outside of oral sex.

Gender

Gender was not significantly related to participant perceptions of oral sex as not being real sex and sex only referring to sexual intercourse. Gender was, however, significantly related to having never given oral sex χ2 (1, N = 781) = 3.843, ρ = .05) and having never received oral sex χ2 (1, N = 781) = 4.016, =.045), with males indicating in greater levels than females that they have received oral sex, and also that they have never given oral sex. These findings indicate that the gendered experiences of giving and/or receiving oral sex are important to explore, because it appears from the participant responses in this study that there may be gender differences in the likelihood of an individual giving or receiving oral sex.

Discussion

This research sought to gain information about college-aged individuals most likely to agree that oral sex is not sex and to share information about individuals within this population’s perceptions about engagement in oral sex. The results allowed for the development of a demographic profile of participants who agreed that oral sex is not sex. In considering the results and demographic profile of participants who agreed that oral sex is not sex, relationships between sexual scripts and participant responses emerged.

The demographic profile which emerged indicated that participants most likely to agree that oral sex is not sex were underclassmen (freshmen and sophomores), European American and self-identified as religious. Inferences from the results were made through a parallel exploration of sexual scripts and the quantitative data from the studied domains and the demographic profile.

Oral Sex is Safe

The negative relationship that emerged between requiring the use of contraception before intercourse and engagement in oral sex may have many meanings. From the limited information provided through this analysis concerning safe sex practices and perceptions of oral sex, few inferences regarding the relationship between these issues can be made. Although the literature would suggest that college-aged students believe oral sex to be safe, this study did not provide enough information to definitively make this inference. However, the negative relationship between participants who required the use of contraception and previous experience with oral sex indicated that participants with previous experience giving and receiving oral sex were more likely to require the use of a condom before intercourse than were participants with no prior experience giving and receiving oral sex. From this finding, it could be inferred that participants who engage in oral sex are more likely to engage in safe sex practices, aligning congruently with the social sexual script posited in the professional literature of the perceptions that oral sex is safe. However, there could be many contributing factors to this relationship and further study is necessary to make clear inferences.

Oral Sex Potentially Mitigates Religiosity and Sex Guilt Tension

Supporting the sexual script that oral sex mitigates sex guilt because it is not real sex, the findings of this study discerned a strong relationship between religious identification and engagement in oral sex. Participants who reported strong self-identification as religious also reported having engaged in giving and receiving oral sex. Additionally, a significant relationship existed between participant responses to “I am a religious person” and “oral sex is not sex” χ2 (4, N = 781) = 10.310, p = .036). Other studies have shown that teens and young adults engage in oral sex because they view it as something that they do before they are ready to have sex (Remez, 2000). This of course implies that the only thing that counts as sex is vaginal-penile intercourse, and that this type of sexual activity breaks the threshold of virgin status.

These findings are not enough to conclude fully that oral sex is used to mitigate sex guilt-religiosity tension. However, the findings do suggest that college students who view themselves as religious also engage in oral sex, indicating that oral sex may be viewed as less likely to violate religious mores related to sexual engagement, since it is not viewed as real sex.

Oral Sex Requires Less Commitment

Perceptions of oral sex as less intimate and requiring less commitment may be better understood by exploring the class level, racial and sexual value components of the profile that emerged. Students at the beginning of their college careers, freshman and sophomores, were more likely to agree that oral sex is not sex. Developmentally, individuals at more advanced stages of one’s college career, such as juniors and seniors, may be more likely to be searching for a life-partner for a more committed, intimate relationship than students at the beginning of the college experience. By engaging in sexual acts perceived by this population as not real sex, these participants are able to avoid more deeply committed relationships.

In terms of racial background and the perception of oral sex as requiring less commitment, previous researchers have revealed that European Americans are more likely to engage in oral sex. In a national sample, 81% of European American men, 66% of African American men, and 65% of Latino men reported ever having received fellatio (Mahay, Laumann, & Michaels, 2001). Of European American, Latino and African Americans receiving fellatio, 82%, 68%, and 55%, respectively, reported the experience as “appealing” (Mahay et al., 2001). In the same study, 75% of European American women, 56% of Latina women, and 34% of African American women reported ever having provided fellatio for a male partner. Of European American, Latina and African American women providing fellatio, 55%, 46% and 25%, respectively, regarded the experience as “appealing” (Mahay et al., 2001). Mahay’s findings suggest that European Americans are more willing to engage in oral sex because they view it as less intimate, involved, or serious (Mahay et al., 2001). Like deep kissing or manual stimulation, they may perceive it as not sex. In contrast, African Americans may view oral sex as more “intimate, involved, and serious” and hence would be more likely to agree that oral sex is sex. The findings of this study support Mahay’s findings with European Americans being statistically more likely than African Americans to agree that oral sex is not sex.

Indicated sexual values also were related to the sexual script of oral sex as requiring less commitment. Participants who self-identified as hedonists (65.8%), with an if it feels good do it approach to sex, also agreed with the assertion that oral sex is not sex and will allow one to maintain virgin status. Since persons who “hookup” and had sex without love are more likely to be hedonists, it also is not surprising that students who reported that they had experienced having sex without love were more likely to report having engaged in giving and receiving oral sex. These findings support Young’s (1980) analysis of college students’ behaviors and attitudes relative to oral-genital sexuality, which revealed that college students who engaged in oral sex, had experienced sexual intercourse and were sexually active, possessed more favorable attitudes toward oral-genital sexual engagement.

In conclusion, Chambers (2007) studied college students and found agreement with oral sex is not sex, that oral sex is less intimate than sexual intercourse, and that the interpersonal context for being most comfortable about engaging in oral sex is a committed relationship, not a married relationship. Similarly, in the current study, we found that more than 60 percent of the respondents (62.1%) agreed that oral sex is not sex. Specifically, 62.1% responded “yes” to the statement “Having sex is having sexual intercourse, not having oral sex.” In contrast, 37.9% responded “no” to the statement.

Implications

Recognizing undergraduates who are more likely to agree with the assertion that oral sex is not sex will enable counselors and sex educators to provide targeted, specific education experiences to this population. This study revealed that undergraduates who were European American, religious, and underclassmen were more likely to agree that oral sex is not sex. However, although certain statistical differences existed among participants who believed that oral sex is not sex, over 60% of the total participant group in this study agreed that oral sex allows one to maintain one’s virgin status because it is not sex. This indicates that we do need specific targeted sex education opportunities for those most likely to agree that oral sex is not sex, but we also need broad, far-reaching education opportunities for the rest of the college-age population. Furthermore, this study explored the impact of dominant social sexual scripts on college-aged students’ perceptions of oral sex. By understanding the potential of social sexual scripts to ascribe meaning to an act of sexual engagement, sex educators and counselors will be better prepared to engage in discourse with young adults and college-aged individuals in a timely, developmentally-appropriate manner.

Limitations

The data for this study should be interpreted with caution. The data used in this study were pulled from a convenience sample of 781 undergraduates at one southeastern university. This sample cannot be considered representative of the total college-aged population in the U.S. However, it may provide some information from which larger, more representative studies can be developed.

A major limitation of this study is the lack of diversity within the sample. With small numbers of gay, lesbian and bisexual participants, it was impossible to discern the perceptions and likelihood for engagement in oral sex by this demographic segment of the college-aged population. The literature would suggest that college students identifying as gay, lesbian or bisexual may have unique perceptions of oral sex and processes for making meaning of this experience (Feldmann & Middleman, 2002). Unfortunately, this study had limited participants identifying as gay, lesbian or bisexual and did not fully explore this population’s experiences and perceptions. This is a major limitation of this research and should be addressed by additional research specifically exploring the perceptions and engagement of college-aged individuals who identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual in giving and receiving oral sex. Additionally, there were few individuals of Latino or Asian descent included in the sample, limiting the utility of the findings with these individuals.

Another significant limitation of the study was the lack of in-depth exploration about the gendered experience of giving and receiving oral sex. From the initial results, it was determined that a significant relationship existed between gender and giving and/or receiving oral sex. This is an important consideration to explore, particularly when considering the impact of social sexual scripts on the sexual engagement of young people. It is quite possible that males and females in the young adult and college-aged population have very different experiences with and perceptions of the process of engaging in oral sex. This is an area that needs further research and not including a thorough investigation of the impact of gender on the responses of participants was a limitation of this study.

References

Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2003). The trouble of teen sex: The construction of adolescent sexuality through school-based sexuality education. Sex Education, 3, 61–74. doi:10.1080/1468181032000052162

Bhattacharyya, G. (2002). Sexuality and society. New York, NY: Routledge.

Carter, B., & McGoldrick, M. (Eds.). (1999). The expanded family life cycle: Individual, family, and social perspectives (3rd ed). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. (2006). Trends in reportable sexually transmitted diseases in the United States, 2005. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/STD/STATS/trends2006.htm.

Chambers, W. C. (2007). Oral sex: Varied behaviors and perceptions in a college population. Journal of Sex Research, 44, 28–42. doi:10.1207/s15598519jsr4401_4

Clinton, W. J. (1998). Response to the Lewinsky allegations. Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved March 9, 2009 from http://millercenter.org/scripps/archive/speeches/detail/3930.

Edwards, S., & Carne, C. (1998a). Oral sex and the transmission of non-viral STIs. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 74, 95–100. doi:10.1136/sti.74.2.95

Edwards, S., & Carne, C. (1998b). Oral sex and the transmission of viral STIs. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 74, 6–10. doi:10.1136/sti.74.1.6

Feldmann, J., & Middleman, A. B. (2002, October). Adolescent sexuality and sexual behavior. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 14(5), 489–493.

Frith, H., & Kitzinger, C. (2001). Reformulating sexual script theory: Developing a discursive psychology of sexual negotiation. Theory and Psychology, 11, 209–232. doi:10.1177/0959354301112004

Frye, M. (1990). Lesbian sex. In J. Allen (Ed.), Lesbian philosophies and cultures (pp. 305–315). New York, NY: State University of New York Press.

Gagnon, J. H., & Simon, W. (1973). Sexual conduct: The social sources of human sexuality. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Geer, J. H., & Broussard, D. B. (1990). Scaling heterosexual behavior and arousal: Consistency and sex differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 664–671. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.664

Halpern-Felsher, B. L., Cornell, J. L, Kropp, R. Y., & Tschann, J. M. (2005). Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: Perceptions, attitudes and behavior. Pediatrics, 115, 845–851. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2108

Hollander, D. (2005). Many young teenagers consider oral sex more acceptable and less risky than vaginal intercourse. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 37(3), 155–157. doi:10.1111/j.1931-2393.2005.tb00051.x

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders.

Langston, R. D. (1973). Sex guilt and sex behavior in college students. Journal of Personality Assessment, 37, 467–472.

Lindau, S. T., Tetteh, A. S., Kasza, K., & Gilliam, M. (2008). What schools teach our patients about sex: Content, quality and influences on sex education. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 111(2) Part 1, 256–266.

Mahay, J., Laumann, E. O., & Michaels, S. (2001). Race, gender, and class in sexual scripts. In E. O. Laumann & R. T. Michael (Eds.), Sex, love, and health in America: Private choices and public policies (pp. 197–238). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mosher W. D., Chandra A., & Jones J. (2005). Sexual behavior and selected health measures: Men and women 15–44 years of age, United States, 2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 362. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Mosher, D. L., & Cross, H. J. (1971). Sex guilt and premarital sexual experiences of college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 36, 22–32. doi:10.1037/h0030454

Paul, E., McManus, B., & Hayes, A. (2000). “Hookups”: Characteristics and correlates of college students’ spontaneous and anonymous sexual experiences. The Journal of Sex Research, 37, 76–88. doi:10.1080/00224490009552023

Prinstein, M. J., Meade, C. S., & Cohen, G. L. (2003). Adolescent oral sex, peer popularity, and perceptions of best friends’ sexual behavior. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 28, 243–249. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsg012

Remez, L. (2000). Oral sex among adolescents: Is it sex or is it abstinence? Family Planning Perspectives, 32, 298–304. doi:10.2307/2648199

Richey, E., Knox, D., & Zusman, M. (2009). Sexual values of 783 undergraduates. College Student Journal, 43, 175–180.

Richters, J., de Visser, R., Rissel, C., & Smith, A. (2006). Sexual practices at last heterosexual encounter and occurrence of orgasm in a national survey. Journal of Sex Research, 43, 217–226. doi:10.1080/00224490609552320

Rostosky, S. S., & Travis, C. B. (2000). Menopause and sexuality: Ageism and sexism unite. In C. B. Travis & J. W. White (Eds.), Sexuality, society, and feminism (pp. 181–209). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10345-008

Sack, A., Keller, J., & Hinkle, D. E. (1984). Premarital sexual intercourse: A test of the effects of peer group, religiosity, and sexual guilt. The Journal of Sex Research, 20, 168–185. doi:10.1080/00224498409551215

Schulz, B., Bohrnstedt, G. W., Borgatta, E. R., & Evans, R. R. (1977). Explaining premarital sexual intercourse among college students: A causal model. Social Forces, 56, 148–165. doi:10.2307/2577418

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (2003). Sexual scripts: Origins, influences and changes. Qualitative Sociology, 26, 491–497. doi:10.1023/B:QUAS.0000005053.99846.e5

Stepp, L. S. (2005, September 16). Study: Half of all teens have had oral sex. The Washington Post, p. A07.

Stulhofer, A., Busko, V., & Landripet, I. (2010). Pornography, sexual socialization, and satisfaction among young men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 168–178. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9387-0

University Of California, San Francisco (2005, April). Teens believe oral sex is safer, more acceptable to peers. ScienceDaily. Retrieved May 10, 2009, from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2005/04/050411135016.htm.

Weinstock H., Berman S., & Cates W. (2004). Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 36, 6–10. doi:10.1363/3600604

Wiederman, M. W. (2005). The gendered nature of sexual scripts. The Family Journal, 13, 496–502. doi: 10.1177/1066480705278729

Wulf, J., D., Prentice, D., Hansum, D., Ferrar, A., & Spilka. B. (1984). Religiosity and sexual attitudes and behaviors among evangelical Christian singles. Review of Religious Research, 26(2), 119–131. doi:10.2307/3511697

Young, M. (1980). Attitudes and behavior of college students relative to oral-genital sexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 9, 61–67. doi:10.1007/BF01541401

Kylie P. Dotson-Blake, NCC, is an Assistant Professor and David Knox is a Professor at East Carolina University. Marty E. Zusman is Professor Emeritus at Indiana University Northwest. Correspondence can be addressed to Kylie P. Dotson-Blake, East Carolina University, 706 River Hill Drive, Greenville, NC 27858, blakek@ecu.edu.