Dodie Limberg, Hope Bell, John T. Super, Lamerial Jacobson, Jesse Fox, M. Kristina DePue, Chris Christmas, Mark E. Young, Glenn W. Lambie

The professional identity of a counselor educator develops primarily during the individual’s doctoral preparation program. This study employed consensual qualitative research methodology to examine the phenomenon of professional identity development in counselor education doctoral students (CEDS) in a cohort model. Cross-sectional focus groups were conducted with three cohorts of doctoral students in counselor education (N = 18) to identify the experiences that contributed to their professional identity development. The findings identified that (a) programmatic goals to develop professional identity align with the experiences most influential to CEDS, (b) experiential learning opportunities enhanced CEDS professional identity development, (c) the relationships with mentors and faculty contribute to their identity as counselor educators, and (d) being perceived as a counselor educator by faculty influences professional identity development. Implications for counselor education and the counseling profession are discussed.

Keywords: consensual qualitative research, counseling, counselor education and supervision, doctoral student development, professional identity development

Professional identity development is central to counseling professionals’ ethical practice (Corey, Corey, & Callanan, 2010; Granello & Young, 2012). The process of professional identity development is defined as the “successful integration of personal attributes and professional training in the context of a professional community” (Gibson, Dollarhide, & Moss, 2010, pp. 23–24). Counselor education doctoral students (CEDS) develop their identity as counselor educators primarily during their doctoral preparation program (Calley & Hawley, 2008; Carlson, Portman, & Bartlett, 2006; Zimpfer, Cox, West, Bubenzer, & Brooks, 1997). Specifically, intentional experiences designed by faculty and/or initiated by CEDS during their doctoral preparation program promote their professional identity development as counselor educators, supporting an effective transition into academia (Carlson et al., 2006). Counselor education doctoral programs employ diverse pedagogical strategies to promote their students’ identity development (e.g., Zimpfer et al., 1997). However, the impact that the experiences and strategies developed within programs has on students and their professional identity has not been examined in previous research. Therefore, an increased understanding of CEDS’ professional identity development might offer insight into pedagogical experiences that enhance doctoral students’ transition from counseling practitioners to faculty members in higher education (Calley & Hawley, 2008; Magnuson et al., 2003).

Professional identity development within counselor education can be described as both an intrapersonal and interpersonal process (Gibson et al., 2010). The intrapersonal process is an internalization of knowledge shared by faculty members and supervisors (e.g., recognizing personal strengths; areas of growth in academic roles). The interpersonal process develops during immersion into the norms of the professional community (e.g., submitting manuscripts for publication, presenting papers at conferences, teaching courses). These two developmental processes co-occur while counselor education trainees are conceptualizing their specific roles and tasks within academia.

Within counselor educators’ professional identity development, three primary roles emerge: (a) teaching and supervision, (b) research and scholarship, and (c) service (Calley & Hawley, 2008). An exploration of the tasks and/or experiences that facilitate doctoral students’ understanding of their future roles as counselor educators is needed (Calley & Hawley, 2008; Gibson et al., 2010). Carlson and colleagues (2006) developed a conceptual model of professional identity development in counselor education consisting of eight roles or tasks: (a) program expectations, (b) teaching and supervision, (c) research, (d) publications, (e) grants and funding, (f) service and conferences, (g) networking, and (h) professional development. Doctoral preparation programs are tasked with guiding future counselor educators’ understanding of these eight roles. Within doctoral preparation programs, three programmatic structure models are employed: (a) independent, (b) part-time, or (c) cohort (Walker, Golde, Jones, Bueschel, & Hutchings, 2008). For the purposes of this manuscript, we focus on the doctoral preparation cohort model. A doctoral preparation cohort model is defined as a group of students entering their preparation program together (same semester), taking the majority of coursework together, and moving through the program concurrently (Paisley, Bailey, Hayes, McMahon, & Grimmett, 2010).

In doctoral counselor education and supervision preparation programs, professional identity development is crucial as students move from their roles as counseling practitioners to counselor educators: making the paradigm shift from thinking like a counselor to thinking like an educator, supervisor, researcher, and leader (e.g., Carlson et al., 2006; Hall & Burns, 2009). In addition, the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Education Programs (CACREP, 2009) Standards state that doctoral preparation program facilitate experiences for doctoral students to collaborate “with program faculty in teaching, supervision, research, professional writing, and service to the profession and the public” (p. 54). Furthermore, the American Counseling Association (ACA) and the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision (ACES) provide professional development opportunities (e.g., conferences, publications) for CEDS to develop their professional identity as future counselor educators. Nevertheless, limited research has investigated professional identity development of CEDS during their cohort model doctoral preparation program.

The shift of identity for CEDS may be from a counselor identity, a student identity, or other professional identity, depending on vocation before entering a counselor education doctoral program. Development of identity as a counselor educator requires a sometimes-difficult shift from previous occupational foci to that of counselor education. Regardless of previous identity, the counselor educator identity is unique in its focus on scholarship, service, and teaching. Without investing oneself in these qualities of counselor education, CEDS risk making a full transition from their previous identity to that of the counselor educator, thus shorting themselves and future students and employers the benefits of an invested counselor educator, such as being student-centered, contributing to the field through research, and giving back to the counseling community. Given the importance of professional identity development in CEDS, the purpose of the present study was to (a) gain a better understanding of the professional identity development process of CEDS during their cohort model doctoral preparation program and (b) identify the specific experiences of CEDS that influenced their professional identity development. The research question guiding the investigation was: How do CEDS develop their professional identities as counselor educators during their cohort model doctoral preparation program?

Method

We utilized consensual qualitative research (CQR; Hill, Thompson, & Williams, 1997; Hill, Knox, Thompson, Williams, & Hess, 2005) for this study. By definition, CQR combines elements of phenomenological, comprehensive analysis, and grounded theory approach to focus on the subjective experiences of humans in their sociological context (Heppner, Wampold, & Kivlighan, 2008). CQR was selected for this study due to (a) the intention of analyzing the comprehensive, subjective experiences of professional identity development among CEDS; (b) its collaborative nature; and (c) data consistency through consensus (Hays & Wood, 2011). Hill and colleagues (2005) identified four main aspects of CQR: (a) the use of open-ended questions, (b) consensual judgment of meaning in the data, (c) the use of an auditor throughout data analysis, and (d) identifying domains and core ideas through cross-analysis. All four of these research aspects were utilized in our investigation. In addition, our study was initiated as an assignment for a first semester doctoral counselor education class and evolved into a genuine interest in understanding professional identity development processes. As a result, we adhered to all protocol for a research study (e.g., approval of university’s institutional review board).

Research Team

We (the research team and authors) consisted of: seven first-year CEDS within a counselor education and supervision doctorate of philosophy (Ph.D.) program at a large southeastern university, a professor within the counselor education and supervision program who assumed the role of the internal auditor and facilitated the focus group for the first-year cohort (i.e., the research team), and an associate professor, in counselor education and supervision, who fulfilled the role of the external auditor and was not involved in data collection and analysis. We ranged in age from mid 20s to late 50s and consisted of four female students, three male students and two male faculty members, and we are all Caucasian. Five members of the research team conducted focus groups, while all members contributed to analyzing the data with the exception of the external auditor. A master’s-level student, not associated with the data collection or analysis, transcribed the focus group data from an audio format.

Positionality and Trustworthiness

We attempted to separate or bracket our biases and judgments regarding the phenomenon under investigation to understand CEDS professional identity development processes with as much objectivity as possible (Creswell, 2007; Hays & Wood, 2011). Therefore, we recorded our biases and expectations in a meeting prior to data collection (Hill et al., 1997). Additionally, we discussed researcher biases and expectations throughout the duration of the study in order to promote awareness of the influence we, as researchers, may have on data analysis (Creswell, 2007). Our biases included the belief that professional identity development is an important aspect of our doctoral program design and that results from this investigation would exemplify specific experiences, in our program, that highlight the areas of teaching, supervision, research, and service in counselor education. The personal knowledge of the participants may have created bias and higher value in particular participant voices in the data analysis; however, this knowledge also added richness to the data collected through prolonged engagement (Creswell, 2007). Additionally, the power dynamic between a professor leading a focus group or a first-year cohort member leading a focus group may create bias in participant responses. Our expectations were that data would vary by cohort years based on the participants’ time in the program and their level of experience, and experiences in (a) teaching and supervision, (b) participating and publishing research, and (c) presenting at conferences would be more powerful than other experiences due to their emphasis in our doctoral program.

To reduce the effects of bias when coding data and to support trustworthiness for our investigation, we used investigator triangulation and an internal and external auditor to evaluate each step of data analysis (Glesne, 2011; Hays & Wood, 2011; Hill et al., 1997). Both auditors were part of the counselor education program in which the study was conducted; therefore, this internal knowledge of the program may have influenced their review of the data analysis. In addition, we used member checking to support trustworthiness, asking participants to review transcripts, preliminary findings and near-finished writings. Furthermore, we sought to be transparent in revealing unforeseen barriers that presented in the research process, supporting the credibility of the research findings. These barriers included various levels of participation in cohorts, the challenge of coding and analyzing data that the research team itself produced through the first-year cohort focus group, and the ability to identify certain participants through personal knowledge of doctoral students in the program. We sent the raw data and the analysis to external and internal auditors to review the consistency and integrity of the data. The external auditor, whose perspective was not influenced by the research team, may have been influenced from being in the same program. This auditor supported the identified themes and findings. The internal auditor confirmed that the raw data were accurately represented under the domains, core ideas and categories.

Participants

The participants were first-, second- and third-year CEDS enrolled in a counselor education and supervision Ph.D. program at a large research university in the southeastern United States. They were recruited and selected to participate based on purposive criteria (i.e., enrolled as a doctoral student in the counselor education program) through campus email. The doctoral program in counselor education and supervision from which the participants were recruited is a fulltime, three-year program that employs a cohort model and awards Ph.D. degrees (Paisley et al., 2010). Criterion-based selection was utilized to ensure participants had similar experiences and commonalities within their doctoral program and to capture the variety of research interests, skill levels and clinical experience among the three years (Creswell, 2007). Although CQR is a qualitative analysis focused on producing results that illustrate the participants’ life experience related to the phenomenon investigated, CQR methodology does suggest a sample size of at least three cases in order to perform the cross-analysis during the data analysis process. A total of 18 CEDS agreed to participate with fellow cohort members in a focus group designated by year, which was an appropriate sample size for CQR (Hays & Wood, 2011). The first-year cohort included seven focus group participants (100% of the first-year CEDS population at this university) consisting of four Caucasian females and three Caucasian males. The second-year cohort included eight focus group participants (78% of the second-year population) with two Caucasian females, one African-American female, one Asian male, and four Caucasian males. Finally, the third-year CEDS cohort included four focus group participants (67% of the third-year population) comprised of two African-American females, one Asian female, and one Caucasian male.

In this study, we acted as both participants and researchers (i.e., the first-year cohort). In qualitative research, the observers can range from complete observers to complete participants (Creswell, 2013), and while traditional research design encourages impartiality, qualitative research varies. Researchers participating in a study offers greater depth of what the participants are experiencing, helps establish greater rapport with the participants and provides an understanding of the context better than would be understood by nonparticipant observers (Creswell, 2013; Heppner et al., 2008). There were several drawbacks that emerged from engaging in the dual roles of researcher and participant. The primary challenge occurred in analyzing the data for the first-year cohort (our cohort). In the dual roles, a level of familiarity was added, as we knew the underlying meanings of statements that might have appeared unclear to outside researchers. While this dual role also was a strength in that the true meaning of the data was able to be analyzed, the same level and depth of understanding could not be given to coding the second-year and third-year cohort data, as they were not part of the research team.

Data Collection

Data collection consisted of facilitators(s), who were members of the research team, conducting focus groups for each CEDS cohort. The focus groups were semi-structured with five open-ended questions asked in sequential order to promote consistency across groups and allow for rich data collection and in-depth responses (Bell et al., 2012; Heppner et al., 2008). Focus groups were conducted, as opposed to individual interviews, to maximize group dynamics that contribute to richer data collection, with the responses of each cohort being observed and recorded. The questions used to facilitate the focus group were created by the research team based on the literature of doctoral student identity.

The open-ended questions were: (a) Describe your experience of transitioning from counselor to counselor-educator-in-training? (b) I am going to name several different experiences you have had so far during your doctoral program (i.e., clinical work with clients, conducting research, teaching, supervising students, service to the profession, attending or presenting at conferences, interviews with faculty members in your initial doctoral class, cohort membership). Please identify or talk about things that happened in any of these arenas that helped you think of yourself as a counselor educator. (c) What other experiences have you had that resonated with you that affected your development as a counselor educator? (d) What pivotal moments (or critical incidents such as important conversations or successes) have you experienced that have helped to form your identity as a counselor educator? and, (e) Can you talk about any experiences that have created doubts about adopting the identity of a counselor educator?

Focus groups lasted one to two hours, varying by the discussion duration. All participants were assured that answers would be kept confidential to protect relationships within the program and promote honest answers. Although confidentiality was explained as part of the consent process, participants were also reminded that researchers could not guarantee confidentiality of other participants within the focus group. While the focus group design offered an environment rich for discussion, it is possible that participants may have held back on full disclosure due to the close nature of the program and personal knowledge of other participants. A faculty member of the research team facilitated the first-year CEDS focus group in order to preserve group facilitator impartiality and allow the first-year cohort, serving dual roles of research members and participants, to fully participate in the focus group process. The second-year and third-year CEDS focus groups were facilitated by first-year CEDS from the research team. Following each focus group, facilitators were asked to debrief by reflecting on three structured open-ended questions: (1) What experiences did participants mention most frequently and with the most emotional intensity? (2) Were there questions that seemed to elicit more or less response? and (3) Anything else that was relevant or noticeable (to you) during this focus group? The purpose of the debriefing was to acknowledge bias from the focus group leaders and to ensure that each leader could express the experience and understanding of the focus group. All the focus groups and debriefing sessions were audiotaped and subsequently transcribed.

Data Analysis

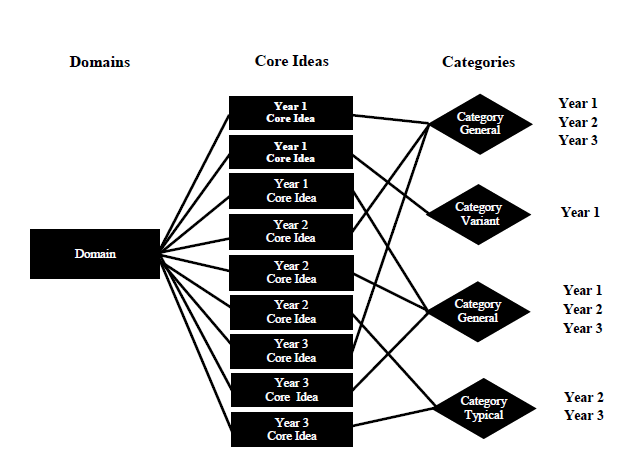

When using CQR, data analysis is a three-step process of (a) clustering data and identifying domains, (b) summarizing core ideas from the domains with shorter descriptions, and (c) developing categories that classify the common themes in the core ideas that exist across cases (Hill et al., 2005). Figure 1 visually explains the data analysis process. We analyzed the data by focus group, and each focus group participant’s contribution was analyzed independently. The data were analyzed to identify domains that were common themes from members of the cohorts. From the domains we recognized core ideas developing within the domain and from the core ideas we recognized categories that developed that crossed the focus groups. Of the eight final domains identified, five domains have more than one category. The process for coding used several methods, using names from the social sciences and in vivo coding where exact words or phrases were used to identify the code.

Figure 1. Data analysis flow chart of the process of analyzing each domain.

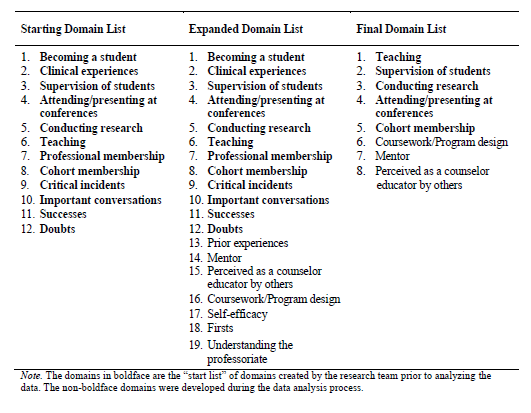

Domains. Before collecting and analyzing the data, we collectively created a 12-item start list of domains to guide our data investigation, which is a suggested step of CQR (Hill et al., 2005; Miles & Huberman, 1994). Table 1 presents the start list of domains (bolded), in addition to domains that emerged during data analysis. The start list domains were based on our expectations, as well as the three areas of (a) teaching and supervision, (b) research, and (c) service within counselor education (CACREP, 2009; Calley & Hawley, 2008). A domain start list created by the research team through consensus and in accordance with previous literature related to the phenomenon studied serves several purposes. The start list familiarized the research team with previous findings and allowed for comparison of new emergent themes, and themes found in previous research that was not identified in the current study. Additionally, the start list acquainted the research team with the process of reaching consensus in data analysis. While domain start lists may serve to skew data analysis if not properly and carefully analyzed, all domains required support from the data to be kept or added. Thus, in viewing Table 1, one can see that the original start list did have domains that were dropped due to lack of support from within the data. In accordance with CQR, we analyzed the first-year CEDS data independently, then met as a consortium and evaluated the same data together until consensus was met and domains adjusted. The second-year and third-year CEDS focus groups’ data were then analyzed through us breaking into dyads and triads. Domains were added to the master list as they appeared in the data and were agreed upon by the entire research team. In addition, we collapsed or deleted any domains that were found to be redundant, insignificant, or not present.

Table 1

Domain List Used to Analyze Data

When analyzing the second-year and third-year focus group data, if a difference of opinion arose concerning the meaning of a response, we added subjective insight from the perspective of the group facilitator and how they interpreted the participants’ response in the greater context of the focus group. Additionally, if consensus was not met, we reviewed the original transcript to clarify and meet consensus of the meaning of the data (Hill et al., 2005).

Core ideas and categories. After categorizing the data by cohort year under domains, we continued to work in dyads and triads to formulate core ideas from the raw data (grouped by domain and not by cohort year). We then determined categories that each core idea fell under. Each core idea was assigned a category, and similar core ideas were collapsed under a category to best represent the data. The categories served an overall purpose to classify and determine frequency in the responses from participants within each domain. Categories were clarified through a cross-analysis (Hill et al., 2005) of the participants’ year in the program, and if more than one member of the cohorts identified a domain as an important task or experience. Figure 1 shows the process of categorizing the data from domains to core ideas and then to categories. In CQR, the number of cases in each category determines the frequency label (Hill et al., 2005). General frequency constitutes all, or almost all, cases; typical constitutes more than half of the cases; and variant for less than half of the cases. For this investigation, each focus group represented one case, so frequency labels were defined as general if the category was present in all three cohort groups, typical if the category was present in two groups and variant if the category only emerged in one cohort’s focus group. We reevaluated the domains based on the frequency of the categories within the domain and the relevance to the research question, resulting in the final domain list (see Table 1) that was agreed on through consensus with the entire research team. Finally, we asked the participants to review the preliminary findings (member check), supporting trustworthiness. Participants supported the findings and did not dispute them.

Results

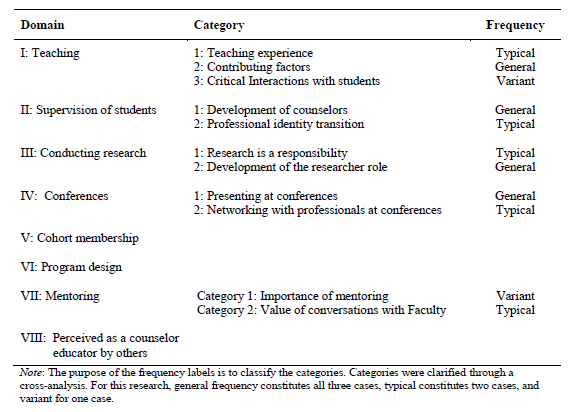

The findings of the investigation are described using domains (i.e., topics used to group data; Hill et al., 2005) and categories used to conduct a cross-analysis to support the findings and connect the findings to the research question. Originally, we developed a start list (Miles & Huberman, 1994) of 12 domains based on previous literature and personal experiences (bolded in Table 1). The start list was expanded to 19 domains through the data analysis (not bolded in column 2 of Table 1). Through further examination, a cross-analysis of the core ideas and categories within each domain was conducted (as presented in Figure 1). After the cross-analysis, the auditors reviewed the data and provided feedback. We revisited the 19 domains, identifying eight domains as strong due to their relevance to the research question and the domain being supported through the clarification of categories (as described in the methods section). The eight domains identified as strong were: (a) teaching, (b) supervision of students, (c) conducting research, (d) attending or presenting at a conference, (e) cohort membership, (f) program design, (g) mentoring, and (h) perceived as a counselor educator by faculty (Column 3 of Table 1; Bell et al., 2012). The eight domains and cross-analysis results are presented in Table 2, which exemplifies the frequency of categories created to increase the level of abstraction in the data analysis (Hill et al., 2005). Not all domains had categories (e.g., cohort membership, program design, and being perceived as a counselor educator by others) because the data within these domains was not diverse enough to create separate categories.

Domain I: Teaching

The teaching domain generated a significant amount of data from the CEDS groups in creating and strengthening their identities as counselor educators. Additionally, the teaching domain produced three contributing categories. Teaching is a core component of a doctoral counselor education program (CACREP, 2009). For this particular university’s program, teaching begins in the first year and peaks in the second year. Teaching was defined as didactic instruction of master’s-level students by doctoral students and occurred in the form of teaching classes, facilitating psycho-educational groups and clinical instruction. The teaching domain was present throughout the first-year, second-year and third-year focus groups with varying emphasis in the categories of (a) teaching experience, (b) contributing factors, and (c) critical interactions with students (see Table 2 for the breakdown and frequencies of the categories within the teaching domain). Therefore, teaching experience during the doctoral program assisted the CEDS in developing their professional identity, specifically their role as counselor educators.

Table 2

Cross-Analysis Findings: Final Domain and Category List

Category 1: Teaching experience. Data generated on the teaching experience category originated from the second-year and third-year CEDS cohorts, designating it as a typical category. Some participants discussed previous teaching experience as vital, while others identified the learning of teaching theories as important. The data revealed the second year as the period in which teaching becomes relevant in this particular counselor education doctoral program. Additionally, first-hand teaching experiences were identified by the third-year cohort as important in counselor educator identity formation. The teaching experience provided doctoral students a way to practice and apply their teaching and learning theory, and an opportunity to build their confidence as teachers. One third-year CEDS stated, “I recognized myself as a counselor educator when I had to assign grades, especially those below a B.”

Category 2: Contributing factors. The category of contributing factors was a general category, present in all three CEDS cohorts. The first-year CEDS felt mandatory programmatic activities such as facilitating psycho-educational groups contributed to their counselor educator identity development in teaching. The second-year students noted the interrelation of teaching and supervision, in that using these skills in a classroom improved their efficacy and contributed to adopting a counselor educator persona. The interrelation is indicated in one student stating, “The second year allows you the opportunity to do everything, including teaching, that you will be doing as a counselor educator.” In addition, evaluating students’ knowledge and skills acquisition helped in developing teaching as a core component of the counselor educator identity. A second-year CEDS supported the importance of student evaluation by stating that teaching and grading were not skills used as a counselor, but differentiated the CEDS as a counselor educator.

Category 3: Critical interactions with students. Though a variant category, third-year cohort members found interactions with students to be influential in adopting the identity of a counselor educator. The third-year group discussed important moments with students that created an impact on them such as: (a) receiving teacher evaluations, (b) grading students, (c) managing student concerns, and (d) feeling pride at student accomplishments. One student stated:

In terms specifically of my teaching I remember grading and being, okay this is where I have to be a big boy, this is where I have to be the counselor educator. It falls to me to decide to pass evaluation and not just a verbal feedback, but a grade… it was a moment, a specific moment where I was like okay now I’m a counselor educator.

Domain II: Supervision of Students

Supervision was the second largest domain present in the CEDS focus groups that was relevant in the participants’ development of a counselor educator identity, which was not surprising due to the emphasis on supervision within counselor education. Data within the supervision domain yielded two categories: (a) supervision teaches future counselor educators about the development of counselors and (b) supervision profoundly affects CEDS’ professional identity transition from counselor to counselor educator (see Table 2 for frequency breakdown). One participant stated, “Supervision brings teaching and counseling skills together to see what students are grasping.”

Category 1: Development of counselors. Supervision as a critical part of counselor development was a general category within the supervision domain and included theoretical aspects of supervision (e.g., applying theories of supervision and adjusting those theories to the development of students), as well as the practical aspects within supervision (e.g., focusing on what students need to know in order to proceed in the field of counseling and in their own growth and development). One CEDS summarized the importance of observing and enhancing development of counselors-in-training as follows:

I would say…supervising students for me has been counselor education in its purest form. Because when you’re in front of a class you’re teaching counselor concepts to people you are wondering are they grasping it, how are they understanding it and when you’re sitting down one-on-one and really supervising a student while they’re counseling someone else over a year or a semester, it gives us an opportunity to be intimately aware of what they’re learning and for me it’s been one of the most energizing and rewarding elements of a counselor educator.

Category 2: Professional identity transition. The doctoral students represented in these focus groups begin their education and practice of supervision during the second year of their doctoral program. Aligning with program sequencing, the majority of responses in the professional identity transition category came from the second-year cohort with support from the third-year CEDS, designating it as a typical category. Second-year students noted that the introduction of supervising students during the second year of the program facilitated their role transition from counselor to counselor educator. A second-year CEDS stated, “I think really what solidified it for me was the supervision class… having two of those before teaching even. That’s when I remember making that shift into thinking as an educator and supervisor rather than a counselor.” Another second-year CEDS stated, “Supervising students has been helpful to be me, sitting on the other side of the table instead of me counseling the client; I’m supervising the counselor (who is) counseling the client.” The third-year CEDS also identified supervision as one of the most significant experiences in solidifying their counselor educator identity.

Domain III: Conducting Research

The domain of conducting research as an important identity-forming experience was present across all the CEDS cohorts. Although the importance of conducting research was present in first through third years, it appears to peak in the second year of the program where research is emphasized through coursework. CEDS in the second-year cohort reported an increased interest in research and awareness of the relevance of research in counselor education and identifying as a counselor educator. A second-year CEDS stated:

One thing that really clicked for me this year was speaking in terms of research and that was a new way of thinking for me. It was a struggle between wearing my counselor hat versus my counselor educator hat and was sort of manifested in my research ideas. I was doing a lot of counselor practitioner kind of thinking in terms of research and I switched that into thinking of counselor educator research and that helped my identity transition.

Two categories were identified within the conducting research domain: (a) research is a responsibility and (b) development of the researcher role (see Table 2 for category and frequency breakdown).

Category 1: Research is a responsibility. The theme that research inquiry is not just a duty of a counselor educator, but also a responsibility to the profession presented as a typical category. The third-year cohort focused on the feeling of responsibility toward conducting research. The second-year CEDS contributed the majority of data in the research is a responsibility category and focused on the responsibility of research, writing and contributing to the professional knowledge base. During the second-year CEDS focus group, a conversation thread emerged focused on intentionality of contributing to the field of literature with quality research. All second-year cohort members agreed that the responsibility of conducting research was an area that substantially helped in their transition from thinking like a counseling practitioner to thinking like a counselor educator.

Category 2: Development of the researcher role. Data assigned to the research category was fairly distributed between all three cohorts, designating it as a general category. The first-year CEDS focused on their initial experiences, including the process of writing the first manuscript and the first Institutional Review Board (IRB) submission and approval. A major theme of second-year CEDS was identifying and developing research interests. Third-year CEDS focused more on the products of conducting research, such as presenting research results at conferences and conducting follow-up research. These research themes appeared to be developmentally appropriate as they matched the educational structure of this particular doctoral counselor education program.

Domain IV: Conferences

Although the domain of conferences produced broad responses from participants, it was clear that conference attendance contributed to identity development. Data centered around two categories contributing to CEDS’ identity development as counselor educators: (a) attending and presenting papers at conferences and (b) networking with other professionals in counselor education.

Category 1: Presenting papers at conferences. Conference presentation was a general category, present across all three years of CEDS. First-year students discussed the importance of presenting papers in developing professional identity. One reason identified for the importance of presenting papers was that other professionals at conferences expressed interest in their work and this professional attention was affirming. Second-year CEDS felt conference presentations solidified their role as a counselor educator, making it “more real.” Third-year CEDS stated that presenting papers at conferences gave a feeling of “professional weightiness,” in that they felt respected when other professionals valued their contributions and recruited them for potential faculty positions.

Category 2: Networking with professionals at conferences. The category of networking with professionals at conferences was a typical category, present in the first and second-year cohort responses. First-year students felt conversations with counselor educators outside of their program that occurred during conferences were helpful in the formation of their counselor educator identity. A second-year CEDS emphasized:

Attending the conferences is really good… I’m able to see other professionals that have been successful going through what I’m in now. And to get advice from them, to hear some tips that they have about research or teaching…umm and just getting inspired and motivated and saying that “you know I can see myself in their positioning in another year and a half or so.”

Domain V: Cohort Membership

The university at which our research was conducted employs a cohort model for the doctoral program in counselor education. As noted, a cohort model is defined by a group of students entering the program together, taking the majority of coursework together and moving through the program concurrently (Paisley et al., 2010). In participants’ responses, we found cohort membership was valuable in both first-year and second-year students. First-year CEDS expressed that being a part of the cohort helped create a vision of the future as a counselor educator. The students also recognized cohort members as future colleagues. Second-year CEDS focused on learning from cohort members, such as relying on cohort members’ expertise in understanding new situations and how sharing experiences with cohort members helps support them through the doctoral preparation process. It was not surprising that cohort membership did not emerge in the third-year students, as course work ends in the second year so third-year students can focus on dissertations. The lack of coursework contributes to less time the CEDS are together, and thus less of an emphasis on cohort membership and dynamics.

Domain VI: Program Design

The program design domain appeared often, but only in the second-year cohort data. The data reflected the second-year CEDS’ beliefs that the program was intentionally designed to develop skills and knowledge incrementally bringing all the roles of a counselor educator together in the second year of the doctoral program. For example, evaluation by faculty and classroom assignments helped students understand their roles as counselor educators. A second-year student stated, “In the second year, the program is set up to do everything we will be doing in the profession.” While program design domain does not contain categories, it was one of three domains added to the final list that was not associated with the original start list of domains (see Table 1). As the focus groups were conducted in the beginning of the academic year, first-year students may not have recognized the program design as an asset in their identity development as counselor educators due to their newness to the program. We were somewhat surprised that the program design domain did not come up in the third-year focus group; however, as previously mentioned, the third year is centered on dissertation. Therefore, program design may seem less clear during the third year in the program, as the CEDS are working independently.

Domain VII: Mentoring

The data in the mentoring domain crossed all three CEDS cohorts emphasizing the importance of mentoring across the doctoral program. From the mentoring domain, two categories emerged: (a) the importance of mentoring on the student’s professional identity development and (b) the value of conversations with faculty members on their development. A mentoring relationship was beneficial in the CEDS’ professional identify development, which was identified in the data, but was not part of the original start list of domains (see Table 1).

Category 1: Importance of mentoring. The importance of mentoring was present in both first-year and second-year cohort CEDS focus groups, designating it a typical category. First-year CEDS recognized the mentor relationship as an integral part of doctoral education. Second-year CEDS focused on the modeling of teaching by faculty members and faculty assisting in the development of research interests and writing. One student stated, “just being taken under some faculty member’s wing and having them take an invested interest in me and having me connect what my interests are in the community…has been mentally helpful for me.”

Category 2: Value of conversations with faculty. The value of conversations with faculty was a general category. First-year CEDS discussed conversations such as professors checking in on their progress and expressing pride in their work. One student stated, “Talking with a professor who has been successful and is similar to me has validated me in many ways.” Second-year and third-year CEDS focused on encouragement from faculty in terms of honing research interests and consulting with faculty about students, as exhibited in this statement:

A professor told me that my paper could be a manuscript and I didn’t view it like that. I didn’t understand what that meant (to write a manuscript) until the professor said that and I’m like, really? And I didn’t really have the self-efficacy to believe that until he started working with me and I realized the accuracy of his statement. Because I didn’t believe that of all the people out there making contributions (to the scholarly body of research) that I could actually be one of those people making contributions. It is due to the mentorship and support and somebody highlighting the opportunity.

Domain VIII: Perceived as Counselor Educator by Faculty

The domain of being perceived as counselor educator by faculty crossed all three CEDS cohorts and reflected the professors’ belief and vision of students as future counselor educators. The perceived belief of the faculty members was then reflected in the self-confidence of the CEDS. Students across cohorts gave examples of professors believing in their research, asking for recommendations, and being addressed by professors as counselor educators. One student said, “The professors seeing me as an educator helps me see myself that way.” In addition, one CEDS identified a defining moment while networking at a conference when a professor from an outside university asked for an opinion regarding which textbook to use. The professor’s request validated the student’s identity as a counselor educator and gave the perception of being accepted in the field. Being perceived as a counselor educator by faculty emerged as a domin through data analysis and was not part of the original domain start list (see Table 1).

Discussion

Previous research supports three primary counselor educator roles (teaching and supervision, research, and service; Calley & Hawley, 2008; Carlson et al., 2006). The teaching domain (subcategories: teaching experience, contributing factors, and critical interactions with students) and the supervision domain (subcategories: development of counselors and how it impacted counselor identity) generated the most data from our CEDS participants. Thus, teaching and supervision may serve as distinguishing factors of the transition from counseling practitioner to counselor educator. The perspective that the counselor educators’ researcher role develops during the beginning of this preparation program, and conducting and developing research interests are established through participation on research teams and presenting research results was consistent with previous findings (e.g., Calley & Hawley, 2008; Carlson et al., 2006). However, the responsibility and application of conducting research is important to emphasize throughout a doctoral program to enhance professional identity development. The role of service in counselor education (e.g., Calley & Hawley, 2008) was not supported in our data. The CEDS in our investigation may not have been aware of the opportunities to provide service to the counseling profession, or they may not view service as a priority. Therefore, the counselor educator role of service may be an area of growth for some doctoral programs to expand opportunities for CEDS to provide service in the field.

In addition, our findings support the premise that the development of CEDS professional identity as counselor educators is intimately linked to the students’ doctoral preparation program which was consistent with previous findings (e.g., Carlson, et al.,1997). Built within the participants’ program were opportunities for CEDS to take on the roles of counselor educator, including teaching, research, supervision, and participation in the greater community of counselor educators through conference participation. What is noticeably absent from our results is the lack of influence that the curriculum (e.g., attending class meetings, reading, writing papers, listening to lectures) played in the professional identity development of the CEDS. Although each participant was enrolled as a fulltime CEDS through the duration of their education, the influence of “learning by doing” seemed to develop the identity of each participant more than traditional didactic learning methods. Thus, it is important for counselor education doctoral programs to consider practical experiences for their students (e.g., opportunities’ for teaching, research and supervision).

The influence of faculty and networking (e.g., mentoring, being perceived by faculty as counselor educators, and attending and presenting at conferences) is crucial to CEDS’ professional identity development, and was a unique finding. However, it was noted that counselor education faculty members influenced their students primarily outside of the classroom setting. Faculty (including those outside of one’s program) helped their students grow into the identity of counselor educator through (a) consultation, (b) developing research interests, (c) believing in and treating the students as counselor educators, (d) encouraging students to present at conferences, and (e) mentorship. Our findings affirm the importance of counselor education faculty members’ influence on the development of future counselor educators and professional counselors.

Lessons Learned

As this investigation was our first time conducting qualitative research, specifically CQR, we reflected on lessons learned through this process. Three overarching lessons emerged: (a) coding qualitative data using CQR methodology is a lengthy process that requires significant and honest discussion, (b) the consensual aspect of CQR seemed to balance personal bias, and (c) applying a new research methodology while concurrently learning the process of the methodology presents many challenges. While the focus groups were an expedient method of collecting the data, we found coding the data required a significant amount of time to ensure the data were represented in the codes. Correct categorization of the data was somewhat remedied by dividing up the second-year and third-year CEDS data; however, each smaller team continued spending significant time with their respective data. Additionally, balancing the thoughts and opinions of seven of us was challenging; however, the guidelines for CQR methodology delineated that consensus must be reached in coding the data (Hill et al., 2005). Although a lengthy process, it appeared to balance bias allowing the data to speak for itself in producing new domains. Finally, we served as both researchers and participants, which we recognize as a limitation. However, the active learning process of conceptualizing and applying CQR simultaneously while serving as participants provided us an opportunity to develop our own professional identity as counselor educators, specifically in the area of research.

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

As in all research, limitations were apparent in our investigation. At the time the focus groups were facilitated, we were in the first year of the program, and all of us were from the same university. Our study involved only students in a single doctoral program, which is a cohort design; therefore, the results emphasize the specific goals and curriculum design of one cohort model in counselor education. In addition, we served as participants in representing the first-year doctoral student perspective. Though facilitated by a faculty member, we did have previous knowledge of the research questions and analyzed the data resulting from the focus group.

Although CQR is an emerging methodology that has not been used extensively in counselor education, we followed Hill et al.’s (1997; 2005) CQR guidelines and other scholarly writing guidelines (e.g., Hays & Wood, 2011; Lambie, Sias, Davis, Lawson, & Akos, 2008). After reviewing several CQR methodologies in various studies, Hill et al. (2005) found many advantages and disadvantages to the consensual process of qualitative data collection; one of the advantages may be the rigorous cross-analysis embedded within the CQR method. Our qualitative investigation used a meticulous cross-sectional approach to identify key components of professional identity development among CEDS. A limitation to CQR is researcher bias, which should be safeguarded by considering and reporting all biases (Hill et al., 2005). We spent a significant amount of time considering and discussing potential biases. Finally, we listed all potential biases and through consensus identified actual biases as reported earlier.

A recommendation for future research, based on our investigation, is to expand the sample to include other doctoral counselor education programs, specifically different models (e.g., part-time, independent), allowing domain consistency to be explored, as well as identifying similarities and differences across counselor education doctoral programs. In addition, future research may benefit from the exploration of pre-tenured faculty members’ experiences of professional identify development in comparison to CEDS. Furthermore, a quantitative design may be employed to examine significant relationships of specific domains and productivity of doctoral counselor education students.

In summary, our study examined CEDS’ experiences that helped build their professional identity as counselor educators. The data were collected from three cohorts representing different stages in their doctoral preparation program and analyzed using CQR methodology. The findings suggested that: (a) programmatic goals align with the experiences critical to CEDS professional identity development, (b) experiential learning opportunities (e.g., teaching courses under supervision, participating on a research team, and supervising students) appeared more influential than traditional content learning, and (c) the relationships with mentors and faculty members contribute to both the CEDS efficacy and development of their identity as counselor educators. Therefore, counselor education doctoral programs may want to evaluate current curricula to ensure their students have experiential learning opportunities, if they wish to promote the professional identity of counselor educators.

References

Bell, H., Limberg, D., Young, M. E., Robinson, E.H., Robinson, S., Hayes, G., . . . Christmas, C. (2012). Professional identity development of counselor education doctoral students. Paper presented at the British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy, Scotland.

Calley, N. G., & Hawley, L. D. (2008). The professional identity of counselor educators. The Clinical Supervisor, 27, 3–16.

Carlson, L. A., Portman, T. A., & Bartlett, J. R. (2006). Self-management of career development: Intentionally for counselor educators in training. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 45, 126–137.

Corey, G., Corey, M. S., & Callanan, P. (2010). Issues and ethics in the helping professions (8th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2009). CACREP accreditation manual. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Gibson, D. M., Dollarhide, C. T., & Moss, J. M. (2010). Professional identity development: A grounded theory of transformational tasks of new counselors. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50, 21–38.

Glesne, C. (2011). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Granello, D. H., & Young, M. E (2012). Counseling today: Foundations of professional identity. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hall, L. A., & Burns, L. D. (2009). Identity development and mentoring in doctoral education. Harvard Educational Review, 79, 49–70.

Hays, D. G., & Wood, C. (2011). Infusing qualitative traditions in counseling research designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 288–295.

Heppner, P. P., Wampold, B. E., & Kivlighan, D. M. (2008). Research design in counseling. (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson.

Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, B. J., Williams, E., Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005).Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 196–205.

Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Nutt Williams, E. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25, 517–572.

Knox, S., Burkard, A. W., Janecek, J., Pruitt, N. T., Fuller, S. L., & Hill, C. E. (2012). Positive and problematic dissertation experiences: The faculty perspective. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 24, 55–69.

Lambie, G. W., Sias, S. M., Davis, K. M., Lawson, G., & Akos, P. (2008). A scholarly writing resource for counselor educators and their students. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86, 18–25.

Magnuson, S., Davis, K. M., Christensen, T. M., Duys, D. Y., Glass, J. S., Portman, T., . . . Veach, L.J. (2003). How entry-level assistant professors master the art and science of successful scholarship. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 42, 209–222.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Paisley, P. O., Bailey, D. F., Hayes, R. L., McMahon, H., & Grimmett, M. A. (2010). Using a cohort model for school counselor preparation to enhance commitment to social justice. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 35, 262–270.

Walker, G. E., Golde, C. M., Jones, L., Bueschel, A. C., & Hutchings, P. (2008). The formation of scholars: Rethinking doctoral education for the twenty-first century. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Zimpfer, D. G., Cox, J. A., West, J. D., Bubenzer, D. L., & Brooks, D. K. (1997). An examination of counselor preparation doctoral program goals. Counselor Education and Supervision, 36, 318–331.

Dodie Limberg is an Assistant Professor at Texas A&M-Commerce. Hope Bell is a doctoral candidate at the University of Central Florida. John T. Super, NCC, and Lamerial Jacobson are doctoral graduates of the University of Central Florida. Jesse Fox, NCC, is a doctoral candidate at the University of Central Florida. M. Kristina DePue, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at the University of Florida. Chris Christmas is a doctoral candidate at the University of Central Florida. Mark E. Young is a Professor and Glenn W. Lambie, NCC, is an Associate Professor at the University of Central Florida. Correspondence regarding this article can be addressed to Dodie Limberg, University of Central Florida, College of Education, Department of Education and Human Services, P. O. Box 161250, Orlando, FL 32816-1250, dlimberg@knights.ucf.edu.