A Pilot Study Examining Xinachtli: A Gender-Based Culturally Responsive Group Curriculum for Chicana, Latina, and Indigenous Secondary Students

Vanessa Placeres, Caroline Lopez-Perry, Hiromi Masunaga, Nicholas Pantoja

This pilot study explores the feasibility, scale reliability, preliminary outcomes, and implementation effects of Xinachtli, a healing-informed, gender-responsive, culturally based group curriculum, on Chicana, Latina, or Indigenous (CLI) youth. Specifically, we examined the perceived impact of culturally responsive group counseling services on middle and high school students’ perception of positive identity, development of life skills, and sense of belonging. Additionally, we examined the feasibility of implementation in a K–12 setting and the reliability of the measures used with CLI youth. Findings from this study provide preliminary support for the Xinachtli intervention in a school setting. Implications for future research are also discussed.

Keywords: group counseling, Chicana, Latina, Indigenous, Xinachtli

The under-18 Latinx youth population grew by 22% between 2006 and 2016 (Lopez et al., 2018), and the number of Latinx youth in U.S. schools continues to rise. By 2016, Latinx students accounted for 25% of the nation’s 54 million kindergarten through 12th grade (K–12) students, up from 16% in 2000 (Pew Research Center, 2018). In New Mexico (61%), California (52%), and Texas (49%), Latinx students account for about half or more of all K–12 students. Latina students represent one in four female students nationwide, and it is projected that by 2060, Latinas will make up nearly a third of the nation’s female population (Gándara, 2015). In this study, we use the term Chicana, Latina, or Indigenous youth (CLI) to refer to young people who identify as Chicana, Latina, and/or Indigenous and those with intersecting, overlapping, or fluid identities across these categories. This inclusive term is used to recognize the cultural, historical, and political complexities of youth whose identities are rooted in Latin America and Indigenous nations across the Americas. When appropriate, we chose to use the specific terms (e.g., Latinx, Latina, Hispanic) employed by the authors cited in this article.

Despite their growing presence, Latina students face persistent systemic barriers, reflected in the opportunity gap between Latinx students and their White peers (Jang, 2019). According to Cooper and Sánchez (2016), academic disparities resulting from educational inequities can present themselves as early as kindergarten and persist through age 17. Gándara (2015) found that Latina students experience disproportionately high secondary education dropout rates and comparatively low graduation and college completion rates relative to other groups of girls/women across racial and ethnic categories. Rodríguez and Cervantes-Soon (2019) identified sources of oppression that shape the educational trajectories of Latina youth. The authors shared, “The silencing of Latina knowledge is rooted in a White hetero-patriarchal ideology that underpins how schooling, education, and knowledge have been conceived in our current educational system” (p. 2112). This “silencing” is achieved through subtractive schooling, in which the cultural, linguistic, and social capital of Latina youth are seen as deficits and intentionally removed from educational systems to force assimilation into White heteropatriarchy. Marginalization of Latinas is upheld by the surveillance of bodies, language ideologies, and gendered societal expectations, in which Latina youth are subjected to more family care responsibilities, thus contributing to their academic struggles and disconnection in school (Rodríguez & Cervantes-Soon, 2019).

Understanding protective factors and developing culturally responsive interventions for this population is essential to addressing these inequities. Their experiences are further shaped by the intersections of ethnicity and gender that provide unique opportunities for resilience and empowerment. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the impact of Xinachtli, a gender-responsive, culturally based group intervention, for secondary CLI students. We focused on secondary students because the curriculum is a rite of passage intervention, created to support teens in their journey toward character development. Specifically, we examined the feasibility of implementation of Xinachtli in a secondary setting; the reliability of the measures used with CLI youth; and the program’s potential to enhance protective factors such as positive identity, life skills, and sense of belonging.

Literature Review

Group Counseling

CLI youth often face exclusion from school curricula that centers White/Westernized histories and ideologies, leading them to navigate challenges without structured supports (e.g., group counseling, classroom lessons, clubs; Iweuno et al., 2024; Taggart, 2018). Group counseling has been identified as an effective service to improve students’ academic, social-emotional, and career development (Steen et al., 2021). Small-group services provide a collectivist platform for culturally responsive practices to increase cultural sensitivity, compassion, and consciousness-raising (Guth, 2019; Shillingford et al., 2018; Steen et al., 2021). However, despite calls for programs that address the unique needs of Latinx youth (Constante et al., 2020), culturally responsive and sustaining small-group interventions for this population are limited. Existing programs that focus on gender identity often narrowly focus on gender exclusively, which overlooks the intersectional experiences of CLI girls and gender-expansive youth (Day et al., 2014). Group counseling centers race and ethnicity while validating and challenging racial conflict and internalized oppression (Steen et al., 2022). This study responds to the urgent need for examining intersectional and culturally sustaining group interventions by centering the experiences of CLI girls and gender-expansive youth.

La Cultura Cura and the Xinachtli Curriculum

Many school counseling supports lack culturally grounded and race-conscious frameworks, often utilizing deficit-based approaches that overlook the strengths of marginalized students (Lopez-Perry, 2023). This is especially concerning, considering the American Counseling Association’s adoption of the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (Ratts et al., 2016), which highlight the complexity of the counselor and client relationship, emphasis on social justice, and centering of intersectionality in counseling (Sharma et al., 2021). Intersectionality provides a framework to examine how multiple aspects of one’s identity (e.g., race, gender, class, sexuality) overlap and interact to shape their experiences of social inequities (Crenshaw, 1989). Applying intersectionality is essential to reflect students’ lived experiences, highlight strengths, and recognize oppressive systems (Sharma et al., 2021). Culturally responsive counseling considers intersecting identities and ecological factors that shape their lived experiences (Sharma et al., 2021).

La Cultura Cura, or Cultural-Based Healing, is an example of a culturally responsive intervention defined as a transformative health and healing philosophy that maintains that within an individual’s authentic cultural values, traditions, and Indigenous practices lies the path to healthy development, restoration, and well-being (The National Latino Fatherhood and Family Institute, 2012; Smith-Yliniemi et al., 2024). Cultural-Based Healing is rooted in Indigenous perspectives and principles, prioritizing culturally grounded physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual practices. Scholars have noted that CLI youth draw on cultural practices such as consejos (advice), conviviendo (community engagement), and chisme (gossip), which they learn from their families and communities to cope with and respond to challenges in institutions like schools (González Ybarra & Saavedra, 2021; Grosso Richins et al., 2021; Kasun, 2015; Rusoja, 2022). Trujillo (2020) explained that chisme, or “spilling the tea,” is not just gossip but a practice and a pedagogy of the home, where ideas, issues, and histories are discussed, deconstructed, and challenged. By embedding opportunities for CLI youth to engage in cultural practices such as consejos, conviviendo, and chisme in group work, school counselors can create an authentic space where CLI youth can discuss their educational experiences.

Aligned with these principles, Xinachtli (Nahuatl for “germinating seed”) is a healing-informed, gender-responsive, culturally based curriculum that promotes CLI youth’s healing, resilience, and leadership capacity. It is an Indigenous, culturally based rites of passage program that provides support for CLI youth to develop a positive identity, life skills, and sense of belonging. The curriculum was developed by the National Compadres Network and is grounded in transformational healing and advocacy rooted in a gender, racial justice, and anti-oppression framework (Haskie-Mendoza et al., 2021). Although the curriculum has been used in various spaces (e.g., probation, mental health county agencies, schools, detention centers, community-based organizations, tribal consortiums), its effects on CLI youth’s sense of belonging and ethnic identity development has yet to be explored (Xinachtli, n.d.).

Sense of Belonging

School belonging is defined as students’ perception that people in the school community are supportive of them and that their presence matters. This concept is especially salient to Hispanic student success because of the deeply rooted collectivistic orientation in Hispanic culture, which emphasizes the idea of mattering within one’s community (Goodenow & Grady, 1993). However, assessing this construct can be difficult because it relies on students’ assessment of their school community, particularly relationships with peers and staff (Murphy & Zirkel, 2015). A large body of literature demonstrates positive associations between Latinx students’ sense of belonging in school and outcomes such as engagement, motivation, and academic success (Neel & Fuligni, 2013). Conversely, low perceptions of a sense of belonging are associated with higher dropout rates (Cupito et al., 2015), lack of engagement, and lower academic achievement (Murphy & Zirkel, 2015). A few scholars have indicated that familial cultural values (familismo) and ethnic identity could serve as protective factors for increasing a sense of belonging at school (Cupito et al., 2015; Harris & Kiyama, 2015). Harris and Kiyama (2015) found that having a caring adult who provided confianza (trust) and social support, especially cultural and linguistic freedom, promoted school engagement. However, much of the existing literature on school belonging is focused on systemic factors (e.g., school safety, peer support, engagement with faculty and staff), which makes the examination of ethnic identity especially important (Hernández et al., 2017).

Ethnic Identity

Ethnic identity is defined as an individual’s social identity rooted in membership to their ethnic group and the importance of this membership (Phinney, 1992). Examining CLI students’ ethnic identity is especially relevant in our study because of the Xinachtli intervention and its focus on cultural membership and belonging. Additionally, previous literature has demonstrated a positive association between ethnic identity and school belonging among elementary-aged students who identify as immigrants from Mexico (C. S. Brown & Chu, 2012; Santos & Collins, 2016). Ethnic identity has been positively associated with self-worth, psychosocial adjustment, confidence, and academic achievement (Fisher et al., 2020; Hernández et al., 2017). Conversely, less developed ethnic identity has been associated with anxiety, depression, and lower self-esteem (Huq et al., 2016; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2002). Chan (2007) explored the impact that culturally responsive school programming (e.g., curriculum, events, group activities) may have on student ethnic identity. Results from their study found that balancing students’ cultural lives at home and school expectations can be difficult. Many studies have highlighted the need for culturally responsive practices in K–12; however, most literature is from the teacher’s perspective, providing little of the student’s voice. Therefore, this study aims to address these gaps in the literature from a student perspective.

Problem Statement and Purpose of the Study

Culturally responsive curricula that meet the needs of CLI girls and gender-expansive youth at the secondary level remains scarce (Kwak et al., 2025). Further, little is known about how culturally responsive small groups impact CLI youth’s ethnic identity and sense of belonging in school. Thus, this pilot study aims to address this critical gap in the literature by examining the feasibility and preliminary effects of Xinachtli. The following research questions guided our study:

RQ1: To what extent is the Xinachtli program feasible to implement in school settings serving CLI youth?

RQ2: How reliable are the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure–Revised (MEIM–R) and Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale (PSSM) in measuring identity and belonging among CLI youth?

RQ3: How does participation in Xinachtli affect participants’ perceptions of positive identity, life skills, and sense of belonging?

Methodology

Participants

Participants were recruited from two middle schools and one high school in a Southern California school district. Participants consisted of members of various Xinachtli counseling groups during spring 2023. Twenty-two respondents took the pre-survey, ranging from 12 to 17 years of age, and were seventh (n = 9), eighth (n = 5), ninth (n = 4), 10th (n = 3), and 11th (n = 1) graders. Regarding primary language spoken in the home, two respondents selected English, 11 selected Spanish, and nine indicated that they used both English and Spanish. Namely, 20 of 22 respondents, or 90.9% of pre-survey respondents, regularly used Spanish at home to communicate with their family members. Additionally, 18 pre-survey respondents (81.8%) planned to attend college after finishing high school. Although the study acknowledged cisgender girls and gender-expansive youth in its framing, the final analytic sample did not include representation from gender-expansive youth. One student who identified outside the gender binary participated but was removed due to incomplete data. As such, findings represent the experiences of cisgender girls.

The study experienced an attrition rate of 68.2%, indicating that most participants who completed the pre-survey did not complete the post-survey. Of the seven participants who completed the post-survey, ages varied from 12 to 17 years old, in grade levels seventh (n = 1), eighth (n = 2), ninth (n = 3), and 11th (n = 1). As for the primary language spoken at home, four of the seven participants selected Spanish, and three chose both English and Spanish. This demonstrated that 100% of post-survey respondents regularly used Spanish at home. Additionally, four of seven post-survey respondents (57.1%) disclosed that they plan to attend college after graduating from high school.

Procedures

Second author Caroline Lopez-Perry and four school counseling group facilitators attended a 2-day training on the Xinachtli curriculum facilitated by its developers. Facilitation of the groups varied between one and two counselors depending on staffing constraints and availability. The counselors were responsible for leading the groups as well as administering and collecting all data to ensure continuity between implementation and evaluation. Prior to data collection, researchers gained IRB and district approval to conduct the study. Parental consent and youth assent were also obtained.

Recruitment and Inclusion Criteria

Across the middle and high school, participants were recruited through self-referral and staff/teacher recommendations. The groups were originally designed for CLI youth; however, there was no formal exclusion criteria, and participation was open to any student who expressed interest or was recommended. The school counselor obtained parental consent through direct communication with families. This included phone calls and personal outreach to explain the purpose of the group, session structure, and benefits for student growth. Participation was not mandatory. Students and their families retained the choice to accept or decline.

At the middle school level, the Xinachtli group was open to CLI students recommended to further develop their leadership skills. A flyer describing the group was created and shared via each school’s social media platforms and email. Although no standardized instrument was used, staff drew upon observations and professional judgement to identify students who might benefit from additional opportunities to refine their leadership skills. Students were required to attend after-school sessions and obtain parental consent to participate.

At the high school, two groups were implemented. The first cohort, conducted in Spanish, included female English Language Learners identified by teachers as having low self-esteem but a strong work ethic. The second English-speaking group included students referred through the school’s Coordination of Services Team for a range of concerns, including unhealthy relationships, low academic performance, and self-esteem challenges. Participation was open to students of any racial background; however, the school population is approximately 90% Latinx. Both cohorts’ recruitment targeted female students.

Setting and Duration

Sessions were held on campus for approximately 1 hour a week. Middle school groups met after school for 6 weeks, and the high school groups met during instructional time for 7 weeks. Sessions were conducted in English, other than the one high school cohort held in Spanish. The after-school time presented some attendance challenges because of scheduling conflicts and transportation but allowed for extended and uninterrupted sessions.

Curriculum

Lesson topics engaged students in setting goals, sharing personal life stories, exploring self-image and building self-esteem, recognizing dating violence, identifying and managing triggers, expanding knowledge of college access, and celebrating accomplishments. High school students also explored reproductive health and participated in a community action plan.

Measures

Data collection included a demographic questionnaire and pre-/post-surveys. The CLI student demographic questionnaire collected information regarding race/ethnicity, gender identity, age, grade, and primary language. CLI youth received pre-/post-surveys to measure perceived changes to ethnic identity using the MEIM–R (S. D. Brown et al., 2014) and sense of belonging at school using the PSSM (Gaete et al., 2016). For the high school group conducted in Spanish, the Escala de Identidad Étnica Multigrupo–Revisada (EIEM-R), adapted and validated in Spanish by Lara and Martínez-Molina (2016), was used in its validated form. No additional translation was required. The PSSM was translated into Spanish using forward translation followed by a review by bilingual experts to ensure conceptual and linguistic equivalence with the original English version. The post-survey also included qualitative questions assessing the students’ experience in the group. In addition to pre-and post-survey measures, feasibility was assessed through multiple methods. School counselors recorded reflections about what worked and challenges faced, and student post-surveys included questions about the program and perceived usefulness.

Ethnic Identity

The MEIM–R is a revised version of the initial scale developed by Phinney (1992), created to assess ethnic identity based on common elements across ethnic groups. This 6-item scale was developed to compare ethnic identity among youth from different ethnic groups (S. D. Brown et al., 2014). MEIM–R uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). A sample question is “I have attachment toward my own ethnic group” (S. D. Brown et al., 2014). The scale is composed of two subscales: Exploration (items 1, 4, and 5) and Commitment (items 2, 3, and 6; S. D. Brown et al., 2014). Responses are scored by reversing negatively worded items and finding the mean for the subscales and total score. The scale has strong reliability with a Cronbach alpha of .82 for the Exploration subscale, .90 for the Commitment subscale, and .88 for the total score (S. D. Brown et al., 2014).

Sense of Belonging

The PSSM measures sense of school belonging in K–12 youth (Goodenow & Grady, 1993). Originally created as an 18-item scale, the PSSM was revised by Gaete et al. (2016) to address potential methodological issues with the negatively worded items. As a result, a 13-item scale including only positively worded items was used to measure students’ overall sense of school membership. Questions include themes of perceived acceptance, inclusion, and encouragement to participate from other students and school staff. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not true at all, 5 = completely true). A sample item is “People at this school are friendly to me” (Gaete et al., 2016). The scale has been translated into several languages; reliability ranged from .73 to .95 across samples and countries with a Cronbach alpha of .92 in the revised version of the scale (Gaete et al., 2016).

Results

Data Analyzed

As described in the Methods section, 22 students participated in this pilot program. However, not all students were able to complete the post-surveys as originally planned, and the study experienced an attrition rate of 68.2%, indicating most participants who completed the pre-survey did not complete the post-survey. To ensure the accuracy of the data obtained, we carefully reviewed the recorded data. During the review process, we removed respondents who had missing data and respondents who mistakenly completed a post-survey in place of a pre-survey. Additionally, for the purposes of this study, analyses were conducted only on data from participants who self-identified as CLI. Upon completion of the review, we recorded 22 pre-survey responses and seven post-survey responses that we used in the analysis.

Overview of Analyses

The survey data were analyzed following three steps. In the first step, participants’ responses to two of the three open-ended questions (OQs) from the post-survey were analyzed, in addition to facilitator reflections, to assess the feasibility of implementing the Xinachtli program in a K–12 setting. Namely, this step of analysis addressed RQ1: To what extent is the Xinachtli program feasible to implement in school settings serving CLI youth? The two open-ended questions analyzed were: OQ1: What did you like most about participating in Xinachtli? and OQ2: What did you like least about participating in Xinachtli? Feasibility data, including facilitator reflections and open-ended post-survey questions, were reviewed thematically to identify patterns related to program acceptability, implementation challenges, and fit. These data were used to evaluate the practicality, acceptability, and cultural responsiveness of the Xinachtli program in the school-based setting.

The second step of analysis addressed RQ2 in relation to reliability of the two instruments used in this study: How reliable are the MEIM–R and the PSSM in measuring identity and belonging among CLI youth? As the pre-survey included more respondents than the post-survey, reliability coefficients were computed for the two instruments using data from the pre-survey.

The third step tested RQ3 about students’ perceptions of the Xinachtli program: How does participation in Xinachtli affect participants’ perception of positive identity, life skills, and sense of belonging? Participants’ identity and sense of belonging at school were assessed using the MEIM–R and PSSM surveys, while qualitative responses were used to explore life skills. As described earlier, the Xinachtli program was developed to cultivate the three attributes of positive identity, life skills, and sense of belonging among CLI youth, by utilizing an Indigenous, culturally based rites of passage curriculum. It is important to note that only four respondents completed both pre- and post-surveys; as a result, we were unable to conduct any repeated-measure analyses to test if participants’ perceptions at the end of the program significantly differed from their perceptions before the program started. Thus, this was an exploratory analysis involving limited numbers of participants, and the interpretation of the results should be viewed from this perspective. During the third step of analysis, item means were reviewed for the two instruments to see if any trends could be observed in participants’ perceptions about the three attributes, (i.e., positive identity, life skills, and sense of belonging) in addition to qualitative data from the third open-ended question (OQ3): How did participation in Xinachtli affect your life (think about your relationships, attitudes, and behaviors)?

Results from Analyses

Step 1: Feasibility of Xinachtli in a School Setting

Participant responses from OQ1 and OQ2 strongly demonstrate the feasibility of the program to be offered in a school setting. Student qualitative data highlight participants’ appreciation for the group, connection to one another, and desire for the group to be longer and held during a different time of the school day. Examples of participants responses include: “I loved the way they would hear me out and let me express myself” (OQ1), “I liked the bond” (OQ1), “I didn’t like that fact that it was so short” (OQ2), “I wanted it to be more longer ”(OQ2), and “The thing I least liked was that it was after school” (OQ2). Additionally, facilitators reflected on the question “What was your experience leading a gender-responsive, culturally based group intervention?” Data highlighted the constraints of leading an ethnicity-specific curriculum in a K–12 setting. Despite this challenge, facilitators reported the experience to be rewarding and meaningful for the students. Lastly, the middle school facilitator noted that holding the sessions after school presented challenges for consistent student attendance.

Step 2: Reliability Analyses

The Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale (PSSM). Scores from the pre-survey involving 22 respondents were analyzed using a listwise deletion of missing data. Consequently, 18 pre-survey responses were used to determine the reliability of PSSM. Using the 13-item PSSM, the computed Cronbach’s alpha was .91, indicating excellent reliability. This strong alpha coefficient indicated that 13 items on the PSSM measured the same construct of sense of belonging within the sample of our pilot study.

The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure–Revised (MEIM–R). After a listwise deletion of missing data, 20 respondents were analyzed to determine the MEIM–R’s reliability within the group of CLI students who participated in the Xinachtli pilot program. MEIM–R yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .81, indicating good reliability. The strong alpha coefficient indicated that six items on the MEIM–R were able to measure the same construct related to ethnic identity.

Step 3: Perceptions About Positive Identity, Life Skills, and Sense of Belonging

Item Means of PSSM. All 13 items of the PSSM were scored from the lowest of 1, associated with the response option not true at all, to the highest of 5, associated with the response option completely true. All available scores were analyzed that were obtained from 20 to 22 respondents. As shown in Table 1, for the pre-test with possible range of 1 to 5 for each of the 13 survey items in this instrument, item means ranged from the lowest of 1.50 for the item “The teachers here respect me” to the highest of 3.05 for the item “I am included in lots of activities at school.” The item that had the second highest mean of 2.23 was “Most teachers at school are interested in me.” For the post-survey, mean scores had a range between 1.57 for “The teachers here respect me” and 2.57 for the item “I can really be myself at this school.” The item that had the second highest mean of 2.29 was “Most teachers at school are interested in me.” As noted earlier, no repeated-measure analyses were carried out to test significant differences between pre- and post-scores because of the limited number of participants who completed both the pre- and post-surveys. However, when we reviewed means from two surveys to see if any post-survey scores were higher than pre-survey scores, the mean differences were the widest for “I can really be myself at this school,” and “People here know I can do good work.”

Table 1

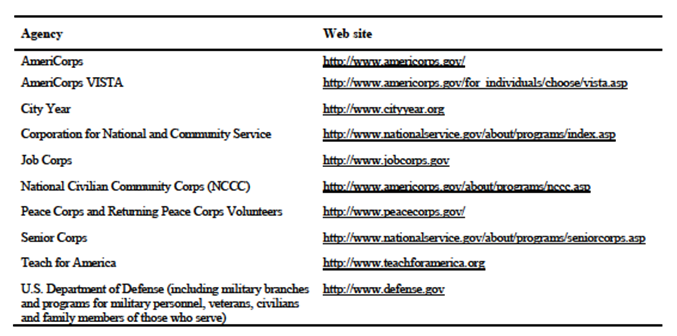

PSSM Survey Item Means and Standard Deviations

| Pre-Survey | Post-Survey | |||||

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |

| 1. I feel like a real part of this school. | 20 | 2.10 | 0.91 | 7 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| 2. People here notice when I’m good at something. | 21 | 2.05 | 1.02 | 7 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| 3. Other students in this school take my opinions seriously. |

21 | 2.14 | 0.91 | 7 | 2.00 | 0.82 |

| 4. Most teachers at school are interested in me. | 22 | 2.23 | 0.97 | 7 | 2.29 | 0.49 |

| 5. There’s at least one teacher or other adult in this school I can talk to if I have a problem. |

22 | 1.77 | 0.87 | 7 | 2.00 | 0.82 |

| 6. People at this school are friendly to me. | 21 | 1.76 | 0.94 | 7 | 1.71 | 0.76 |

| 7. I am included in lots of activities at school. | 21 | 3.05 | 1.36 | 7 | 2.14 | 0.90 |

| 8. I am treated with as much respect as other students. |

20 | 1.80 | 0.77 | 7 | 2.00 | 0.58 |

| 9. I can really be myself at this school. | 20 | 2.10 | 1.07 | 7 | 2.57 | 0.54 |

| 10. The teachers here respect me. | 20 | 1.50 | 0.61 | 7 | 1.57 | 0.79 |

| 11. People here know I can do good work. | 21 | 1.71 | 0.64 | 7 | 2.14 | 0.69 |

| 12. I feel proud of belonging to this school. | 20 | 1.85 | 0.88 | 7 | 2.14 | 0.69 |

| 13. Other students here like me the way I am. | 20 | 1.80 | 0.70 | 7 | 2.00 | 0.82 |

All six items of the MEIM–R had the score range from the lowest of 1 for the response option strongly disagree to the highest of 5 for the response option strongly agree. Table 2 denotes item means and standard deviations of items of the MEIM–R for both pre- and post-surveys. As seen in Table 2, for pre-test, with a range of 1 to 5 for each item, item means ranged from the lowest of 2.10 for the item “I feel a strong attachment toward my own ethnic group” to the highest of 2.71 for the item “I have often talked to other people in order to learn more about my ethnic group.” The item that had the second highest mean of 2.57 was “I have a strong sense of belonging to my own ethnic group.” For the post-survey, mean scores had a range between 1.57 for “I understand pretty well what my ethnic group membership means to me” and 2.29 for the item “I have spent time trying to find out more about my ethnic group, such as its history, traditions, and customs.” The item that had the second highest means of 2.14 was “I have a strong sense of belonging to my own ethnic group.” As presented in Table 2, no items in MEIM–R had saliently higher post-survey means as compared to their corresponding pre-survey means.

Table 2

MEIM–R Survey Item Means and Standard Deviations

| Pre-Survey | Post-Survey | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1. I have spent time trying to find out more about my ethnic group, such as its history, traditions, and customs. |

21 | 2.38 | 0.97 | 7 | 2.29 | 0.95 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. I have a strong sense of belonging to my own ethnic group. | 21 | 2.57 | 0.93 | 7 | 2.14 | 0.69 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. I understand pretty well what my ethnic group membership means to me. | 22 | 2.18 | 0.91 | 7 | 1.57 | 0.98 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. I have often done things that will help me understand my ethnic background better. | 21 | 2.43 | 0.81 | 7 | 1.71 | 0.76 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. I have often talked to other people in order to learn more about my ethnic group. | 21 | 2.71 | 0.78 | 7 | 1.71 | 0.76 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. I feel a strong attachment toward my own ethnic group. | 21 | 2.10 | 0.91 | 7 | 2.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Additional survey questions (i.e., OQ3: How did participation in Xinachtli affect your life [think about your relationships, attitudes, and behaviors]? and OQ1: What did you like most about participating in Xinachtli?) were also used to assess the program’s impact on participants’ identity, life skills, and sense of belonging. Participants’ open-ended responses were coded into three categories (i.e., positive identity, life skills, and sense of belonging). Table 3 highlights participants’ responses.

Table 3

Open-Ended Responses Classified Into Categories of Positive Identity

| Categories | Open-Ended Responses |

| Positive Identity | I feel that Xinachtli helped me be confident and proud in who I am. (OQ3)

It helped me with being more talkative and having more positive self thoughts. (OQ3) Participating in Xinachtli has taught me how to let things go and accept myself and what I enjoy doing. (OQ3) |

| Life Skills | I believe that Xinachtli helped me have a better understanding about lots of stuff like behaviors and acting such a way. (OQ3)

I believe that Xinachtli really affected my life because now it helps me understand things that I didn’t understand before. (OQ3) It helps me talk more to people. (OQ3) It made me bc [sic] more mindful about my relationships with people and my surroundings. (OQ3) I liked how we’d express ourselves and things we did such as the mirror. (OQ1) What I liked most about participating in Xinachtli is that I found myself to be more understanding. (OQ1) |

| Sense of

Belonging |

Being able to be listened to. (OQ1)

I liked the bond. (OQ1) I loved the way they would hear me out and let me express myself. (OQ1) Maybe the fact that they would feed me and they were there with activities when I was feeling down. (OQ1) Meeting new people and doing relaxing activities. (OQ1) What I liked most about participating in Xinachtli is that I also have a great relationship with the people. (OQ1) |

Note. OQ1 = Open-Ended Question 1; OQ2 = Open-Ended Question 2; OQ3 = Open-Ended Question 3.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to extend the literature on the implementation of Xinachtli with CLI youth in a K–12 setting. In this pilot study, we examined the feasibility, reliability, and impact of the culturally responsive group counseling curriculum from a student perspective as it relates to positive identity of self, life skills, and sense of belonging. The study was guided by the following questions: To what extent is the Xinachtli program feasible to implement in school settings serving CLI youth? How reliable are the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure–Revised (MEIM–R) and Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale (PSSM) in measuring identity and belonging among CLI youth? How does participation in the Xinachtli curriculum affect participants’ perceptions of their positive identity, life skills, and sense of belonging? Overall, although some of the findings show mixed results, there was still a small increase in students’ sense of belonging at school. Additionally, students’ qualitative data highlights ways that the group improved their perspective of their identity, life skills, and sense of belonging.

Using both the facilitators’ and students’ qualitative responses, we found that the feasibility of implementing Xinachtli in a school setting serving CLI youth was both challenging and rewarding. From a facilitator’s perspective, the constraints of the gender-based curriculum made it difficult to implement in a K–12 setting because of the inclusion criteria. Additionally, implementing the group meetings after school may have created a barrier to attendance and scheduling. Despite these challenges, facilitators reported the experience being rewarding and meaningful for the students. Student data supports these findings, as participants shared general appreciation for the group and the space but wanted the program to be longer. We also found the PSSM and MEIM–R to have strong reliability and that they were appropriate to use with CLI youth in a K–12 setting. This finding is supported by prior research that found both scales to be reliable in a school setting (Gaete et al., 2016; Hussain et al., 2018; Musso et al., 2018).

The Xinachtli program was developed to address positive self-identity, life skills, and sense of belonging through a culturally responsive lens. Results from the current study preliminarily support that the curriculum did have a positive impact on participants’ perceptions of positive identity, life skills, and sense of belonging. More specifically, related to positive identity, student qualitative data highlights an improvement in participants’ confidence levels, acceptance of self, and joy in life. Further, although we did not find a significant increase in ethnic identity between the pre- and post-survey data, qualitative data underscores that participants experienced feelings of pride related to their identities. Findings also accentuated an improvement in life skills, related to participants’ level of understanding of life and others after completion of the group. Results among participants are consistent with previous research demonstrating that students who participated in Xinachtli reported an increase in self-empowerment skills, identity development, and an overall improvement in self-efficacy (Haskie-Mendoza et al., 2018; Hernandez, 2023).

Descriptive trends also reveal shifts in participants’ sense of belonging between the pre- and post-survey data. The preliminary results highlight an increased mean on most items in the PSSM with the largest difference on items 3, 5, and 13: “Other students in this school take my opinions seriously,” “There’s at least one teacher or other adult in this school I can talk to if I have a problem,” and “Other students here like me the way I am.” Additionally, participants’ qualitative data reinforces these findings, as many shared an appreciation for the relationships formed and support received during the group. Findings from this study are consistent with research demonstrating that participation in Xinachtli increases sense of community, interpersonal skills, and understanding of others (Haskie-Mendoza et al., 2018; Hernandez, 2023).

Although preliminary results are promising, we did not find significant mean differences in participants’ ethnic identity scores. A possible explanation for this could be related to the constraints of conducting a group curriculum across three different school settings and the variability in lessons provided, delivery, and scheduling. Additionally, although Xinachtli is a culturally responsive curriculum, little research has been done on the curriculum as it relates to ethnic identity in a K–12 setting. Previous research focused on the implementation with participants in specific disciplines (e.g., science, technology, engineering, mathematics) and youth involved in the juvenile justice system (Haskie-Mendoza et al., 2018; Hernandez, 2023). This is the first known study to implement the intervention in a K–12 setting and assess for ethnic identity and sense of belonging. Although we did not see significant changes from the pre- and post-survey data related to ethnic identity, exploratory findings are promising, especially as they relate to student qualitative data and changes in sense of belonging after completion of the group.

Implications and Limitations

These results highlight the potential for the Xinachtli curriculum to support the development of positive identity, life skills, and a sense of belonging among CLI youth in the school setting. The culturally responsive nature of the Xinachtli suggests that similar identity-affirming programs could serve as valuable tools for school counselors to create inclusive and affirming learning environments for marginalized populations. Olsen et al. (2024) similarly argued that moving away from deficit-based interventions toward culturally sustaining practices allows counselors to center students’ strengths and lived experiences, thereby fostering belonging and affirmation. Implementation of Xinachtli on a larger scale could further validate these findings and help inform culturally responsive practices in school counseling.

Although the findings were promising, the current study has limitations. First, the curriculum was designed to be implemented with two facilitators, but the middle school groups were facilitated by a single school counselor who conducted all group sessions because of staffing constraints and scheduling limitations. In the future, it would be best to standardize implementation to ensure fidelity of the study. Second, the sample size was limited to CLI youth from three schools within the same district. Future research should consider expanding the participant pool to include a broader range of schools. While Xinachtli is designed to be inclusive of gender-expansive youth, the pilot sample included only cisgender girls. Future implementation should include more deliberate strategies to ensure participation from gender-expansive youth to allow for a more complete understanding of the program’s inclusivity. Additionally, not all lessons from the Xinachtli curriculum were implemented in the pilot study; as such, it is unclear if full implementation would have resulted in stronger outcomes. Future studies might consider measuring the impact of the entire curriculum. Lastly, the short duration of the pilot study limited the ability to measure long-term effects; ongoing research should consider follow-up assessments to evaluate the lasting influence of participation in Xinachtli.

Conclusion

A growing population of CLI youth and their associated educational disparities underscores the need for gender-based culturally responsive counseling services in K–12 settings to meet the educational needs of this student population. Our study is the first to examine the feasibility and effectiveness of Xinachtli, a gender-informed culturally sustaining counseling curriculum, on ethnic identity development and sense of belonging in CLI youth in K–12 schools. Although the quantitative results reveal insignificant differences in participants’ ethnic identity scores, the participants reported an increase in self-confidence, feelings of pride in their ethnic identity, and understanding of life and others as indicated by the qualitative data. Hence, these preliminary findings indicate a potential for the Xinachtli program to positively impact CLI youth’s identity development, acquisition of life skills, and sense of belonging in schools. As scholars and school counselors continue to challenge multiculturally insensitive educational environments, utilizing programs like Xinachtli may be one way to promote culturally responsive services to meet the changing demographics of the students they serve.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Brown, C. S., & Chu, H. (2012). Discrimination, ethnic identity, and academic outcomes of Mexican immigrant children: The importance of school context. Child Development, 83(5), 1477–1485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01786.x

Brown, S. D., Unger Hu, K. A., Mevi, A. A., Hedderson, M. M., Shan, J., Quesenberry, C. P., & Ferrara, A. (2014). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure—Revised: Measurement invariance across racial and ethnic groups. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(1), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034749

Chan, E. (2007). Student experiences of a culturally-sensitive curriculum: Ethnic identity development amid conflicting stories to live by. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 39(2), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270600968658

Constante, K., Cross, F. L., Medina, M., & Rivas-Drake, D. (2020). Ethnic socialization, family cohesion, and ethnic identity development over time among Latinx adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(4), 895–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01139-3

Cooper, A. C., & Sánchez, B. (2016). The roles of racial discrimination, cultural mistrust, and gender in Latina/o youth’s school attitudes and academic achievement. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(4), 1036–1047. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12263

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf

Cupito, A. M., Stein, G. L., & Gonzalez, L. M. (2015). Familial cultural values, depressive symptoms, school belonging and grades in Latino adolescents: Does gender matter? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1638–1649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9967-7

Day, J. C., Zahn, M. A., & Tichavsky, L. P. (2014). What works for whom? The effects of gender responsive programming on girls and boys in secure detention. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 52(1), 93–129. https://doi.org/f6t7hp

Fisher, A. E., Fisher, S., Arsenault, C., Jacob, R., & Barnes-Najor, J. (2020). The moderating role of ethnic identity on the relationship between school climate and self-esteem for African American adolescents. School Psychology Review, 49(3), 291–305. https://doi.org/p796

Gaete, J., Montero-Marin, J., Rojas-Barahona, C. A., Olivares, E., & Araya, R. (2016). Validation of the Spanish version of the Psychological Sense of School Membership (PSSM) scale in Chilean adolescents and its association with school-related outcomes and substance use. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1901. https://doi.org/f9f3rx

Gándara, P. (2015). With the future on the line: Why studying Latino education is so urgent. American Journal of Education, 121(3), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1086/680411

González Ybarra, M., & Saavedra, C. M. (2021). Excavating embodied literacies through a Chicana/Latina feminist framework. Journal of Literacy Research, 53(1), 100–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X20986594

Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

Grosso Richins, L., Hansen-Thomas, H., Lozada, V., South, S., & Stewart, M. A. (2021). Understanding the power of Latinx families to support the academic and personal development of their children. Bilingual Research Journal, 44(3), 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2021.1998806

Guth, L. J., Pollard, B. L., Nitza, A., Puig, A., Chan, C. D., Singh, A. A., & Bailey, H. (2019). Ten strategies to intentionally use group work to transform hate, facilitate courageous conversations, and enhance community building. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 44(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2018.1561778

Harris, D. M., & Kiyama, J. M. (2013). The role of school and community-based programs in aiding Latina/o high school persistence. Education and Urban Society, 47(2), 182–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124513495274

Haskie-Mendoza, S., Serrata, J. V., Escamilla, H., & Jaimes, C. (2021). Xinachtli: A healing-informed, gendered, and culturally responsive approach with system-involved Latinas. In S. Haskie-Mendoza, J. V. Serrata, H. Escamilla, & C. Jaimes (Eds.), Latinas in the criminal justice system (pp. 315–332). NYU Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479804634.003.0015

Haskie-Mendoza, S., Tinajero, L., Cervantes, A., Rodriguez, J., & Serrata, J. V. (2018). Conducting youth participatory action research (YPAR) through a healing-informed approach with system-involved Latinas. Journal of Family Violence, 33(8), 605–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-9996-x

Hernandez, D. (2023). Xinachtli: Exploring the experiences of young resilient Latinas in a rural and under-resourced community [Doctoral Dissertation, California State University, San Bernardino]. Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1729

Hernández, M. M., Robins, R. W., Widaman, K. F., & Conger, R. D. (2017). Ethnic pride, self-esteem, and school belonging: A reciprocal analysis over time. Developmental Psychology, 53(12), 2384–2396. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000434

Huq, N., Stein, G. L., & Gonzalez, L. M. (2016). Acculturation conflict among Latino youth: Discrimination, ethnic identity, and depressive symptoms. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(3), 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000070

Hussain, S. F., Domingue, B. W., LaFromboise, T., & Ruedas-Garcia, N. (2018). Conceptualizing school belongingness in Native youth: Factor analysis of the Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 25(3), 26–51. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.2503.2018.26

Iweuno, B. N., Tochi, N. S., Egwim, O. E., Omorotionmwan, A., & Makinde, P. (2024). Impact of racial representation in curriculum content on student identity and performance. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 23(1), 2913–2933. https://doi.org/pzkn

Jang, S. T. (2019). Schooling experiences and educational outcomes of Latinx secondary school students living at the intersections of multiple social constructs. Urban Education, 58(4), 708–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085919857793

Kasun, G. S. (2015). “The only Mexican in the room”: Sobrevivencia as a way of knowing for Mexican transnational students and families. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 46(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/aeq.12107

Kwak, D., Bell, M. C., Blair, K.-S. C., & Bloom, S. E. (2025). Cultural responsiveness in assessment, implementer training, and intervention in school, home, and community settings: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Education, 34(3), 526–573. https://doi.org/p798

Lara, L., & Martínez-Molina, A. (2016). Validación de la Escala de Identidad Étnica Multigrupo-Revisada en adolescentes inmigrantes y autóctonos residentes en España. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 14(1), 591–601. https://doi.org/10.11600/1692715x.14140110515

Lopez, M. H., Krogstad, J. M., & Flores, A. (2018). Key facts about young Latinos, one of the nation’s fastest-growing populations. Pew Research Center. http://bit.ly/45u3pPv

Lopez-Perry, C. (2023). Disrupting white hegemony: A critical shift toward empowering Black male youth through group work. Journal of School-Based Counseling Policy and Evaluation, 5(1), 21–25. https://doi.org/10.25774/2pd3-a231

Murphy, M. C., & Zirkel, S. (2015). Race and belonging in school: How anticipated and experienced belonging affect choice, persistence, and performance. Teachers College Record, 117(12), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811511701204

Musso, P., Moscardino, U., & Inguglia, C. (2018). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure–Revised (MEIM-R): Psychometric evaluation with adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups in Italy. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(4), 395–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1278363

The National Latino Fatherhood and Family Institute. (2012). Lifting Latinos up by their “rootstraps”: Moving beyond trauma through a healing-informed model to engage Latino boys and men. National Compadres Network. http://bit.ly/45dt9yb

Neel, C. G. O., & Fuligni, A. (2013). A longitudinal study of school belonging and academic motivation across high school. Child Development, 84(2), 678–692. https://doi.org/f4s753

Olsen, J., Betters-Bubon, J., & Edirmanasinghe, N. (2024). Is it students or the system? Infusing a culturally sustaining approach to Tier 2 groups within multi-tiered systems of support. Professional School Counseling, 28(1a). https://doi.org/p799

Phinney, J. S. (1992). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7(2), 156–176. https://doi.org/ffjx9b

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Rodríguez, E., & Cervantes-Soon, C. G. (2019). The schooling of young empowered Latinas/Mexicanas navigating unequal spaces. In R. Papa (Ed.), Handbook on Promoting Social Justice in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74078-2_104-1

Rusoja, A. (2022). “Our community is filled with experts”: The critical intergenerational literacies of Latinx immigrants that facilitate a communal pedagogy of resistance. Research in the Teaching of English, 56(3), 301–327. https://doi.org/10.58680/rte202231639

Santos, C. E., & Collins, M. A. (2016). Ethnic identity, school connectedness, and achievement in standardized tests among Mexican-origin youth. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(3), 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000065

Sharma, J., McDonald, C. P., Bledsoe, K. G., Grad, R. I., Jenkins, K. D., Moran, D., O’Hara, C., & Pester, D. (2021). Intersectionality in research: Call for inclusive, decolonized, and culturally sensitive research designs in counselor education. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 12(2), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2021.1922075

Shillingford, M. A., Oh, S., & DiLorenzo, A. (2018). Using the multiphase model of psychotherapy, school counseling, human rights, and social justice to support Haitian immigrant students. The Professional Counselor, 8(3), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.15241/mas.8.3.240

Smith-Yliniemi, J., Malott, K. M., Riegert, J., & Branco, S. F. (2024). Utilizing collective wisdom: Ceremony-assisted treatment for Native and non-Native clients. The Professional Counselor, 13(4), 448–461. https://doi.org/10.15241/jsy.13.4.448

Steen, S., Melfie, J., Carro, A., & Shi, Q. (2022). A systematic literature review exploring achievement outcomes and therapeutic factors for group counseling interventions in schools. Professional School Counseling, 26(1a). https://doi.org/pzkp

Steen, S., Shi, Q., & Melfie, J. (2021). A systematic literature review of school-counsellor-led group counselling interventions targeting academic achievement: Implications for research and practice. Journal of School-Based Counseling Policy and Evaluation, 3(1), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.25774/sgvv-ta47

Taggart, A. (2018). Latina/o students in K-12 schools: A synthesis of empirical research on factors influencing academic achievement. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 40(4), 448–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986318793810

Trujillo, T. (2020). Spilling the tea on chisme: Storytelling as resistance, survival, and therapy. Grassroots Writing Research Journal, 10(2), 47–57. http://bit.ly/44WFBnf

Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Diversi, M., & Fine, M. A. (2002). Ethnic identity and self-esteem of Latino adolescents: Distinctions among the Latino populations. Journal of Adolescent Research, 17(3), 303–327. https://doi.org/fpcddk

Xinachtli. (n.d.). Curriculum summary. Xinachtligirls. https://rb.gy/mlhevp

Vanessa Placeres, PhD, NCC, LPC, RPT, is an associate professor at San Diego State University and was a 2017 Doctoral Fellow in Mental Health Counseling with the NBCCF Minority Fellowship Program. Caroline Lopez-Perry, PhD, is an associate professor at California State University Long Beach. Hiromi Masunaga, PhD, is a professor at California State University Long Beach. Nicholas Pantoja, MS, PSS, is an alumnus of San Diego State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Vanessa Placeres, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182, vplaceres@sdsu.edu.