Dec 5, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 3

Fei Shen, Ying Zhang, Xiafei Wang

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has consistently been shown to have deleterious effects on survivors’ interpersonal and intrapersonal relationships. Despite the negative outcomes of IPV, distress after IPV varies widely, and not all IPV survivors show a significant degree of distress. The present study examined the impact of IPV on adult attachment and self-esteem, as well as the moderating role of childhood attachment on the relationships between IPV, adult attachment, and self-esteem using path analysis. A total of 1,708 adult participants were included in this study. As hypothesized, we found that IPV survivors had significantly higher levels of anxious and avoidant adult attachment than participants without a history of IPV. Additionally, childhood attachment buffered the relationship between IPV and self-esteem. We did not find that childhood attachment moderated the relationship between IPV and adult attachment. These results provide insight on attachment-based interventions that can mitigate the negative effects of IPV on people’s perceptions of self.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, childhood attachment, adult attachment, self-esteem, moderation

More than 10 million adults experience intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization annually in the United States (Black et al., 2011); therefore, it undoubtedly remains a prominent public health concern. IPV victimization has been consistently associated with deleterious effects on survivors’ physical and mental health. It is well established that IPV survivors demonstrated increased risks for chronic pain, injury, insomnia, disabilities, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and suicidality (Burke et al., 2005; Gilbert et al., 2023; Matheson et al., 2015; McLaughlin et al., 2012). Historically, empirical studies on trauma and violence have focused on psychopathology and symptoms (McLaughlin et al., 2012; Sayed et al., 2015). However, there is limited research on exploring the link between IPV victimization and intrapersonal and interpersonal relationship outcomes. Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969) not only provides a rich theoretical framework for conceptualizing an individual’s psychopathology, but also establishes a foundation for understanding the intrapersonal and relational sequelae of IPV (Levendosky et al., 2012; Sutton, 2019). IPV survivors often experience a violation of trust and a sense of betrayal in the aftermath and develop ineffective coping mechanisms (e.g., distancing themselves emotionally), which could potentially impact their new intimate relationships (St. Vil et al., 2021).

Despite the negative outcomes of IPV victimization, the levels of distress following such incidents can vary (Scott & Babcock, 2010). Although evidence has implicated numerous risk factors related to IPV victimization (e.g., childhood trauma, gender inequity; Jewkes et al., 2017; Meeker et al., 2020), limited effort has been put forth to recognize protective factors that contribute to IPV survivors’ coping and healing processes. Childhood attachment has been proposed as a potential protective factor for IPV survivors’ coping with traumatic experiences and a moderator for buffering the negative psychological outcomes of IPV (Pang & Thomas, 2020), which provides a meaningful foundation for us to further investigate childhood attachment as a moderator buffering relational outcomes. To our knowledge, no study to date has investigated the potential moderating role of childhood attachment security on the association between IPV, interpersonal outcomes (e.g., adult attachment), and intrapersonal outcomes (e.g., self-esteem) in a non-clinical sample. Understanding the moderating role of childhood attachment can potentially provide further directions toward protecting survivors from negative outcomes and creating interventions that foster healthier interpersonal relationships. In tackling the gaps in the literature, we aim to: (a) investigate the impact of IPV on adult attachment and self-esteem; and (b) examine the moderating role of childhood attachment on the relationships between IPV, adult attachment, and self-esteem.

Theoretical Framework—Attachment Theory

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969) offers an explanation of how the relationship between children and their primary caregiver(s) develops and how it impacts children’s subsequent developmental process. According to Bowlby (1973), children develop mental representations of themselves and others, known as internal working models, through their interactions with their primary caregiver(s). Children with secure attachment are more likely to form positive self-perceptions and relationships with others (Bowlby, 1969). In contrast, children who develop insecure attachment are more likely to struggle with coping with distress and form poor relationships with others, resulting from caregivers responding to their needs insensitively.

Although evidence suggests the continuity of attachment from childhood to adulthood (Bowlby, 1969), there are distinctions between these two variables based on individuals’ attachment needs, developmental stages, and characteristics of different relationships. As children grow into adolescents and emerging adults, they often continue to maintain connections with their primary caregivers while exploring new social roles outside of the family and forming close relationships with peers and romantic partners to develop adult attachment (Moretti & Peled, 2004). Secure adult attachment is generally characterized by flexibility, the ability to work independently and cooperatively with others, the ability to seek support from intimate partners, and the capacity to manage loss in a healthy manner (Brennan et al., 1998). Adult romantic relationships are thought to be underlined by two fundamental attachment-related dimensions: anxiety and avoidance. Adults with anxious attachment tend to experience worry and fear regarding abandonment or rejection by their partner, leading them to seek constant reassurance and validation from their partner. On the other hand, avoidant-attached individuals often feel uncomfortable with being close to their partner, which can lead them to withdraw from intimacy and emotional closeness in the relationship (Brennan et al., 1998). Thus, understanding the similarities and differences of attachment categories as well as dynamics of the attachment system is warranted (Lopez & Brennan, 2000).

Childhood Attachment, IPV Victimization, and Adult Attachment

Various researchers have extensively investigated the significant association between attachment developed with romantic partners and its involvement in IPV dynamics (Bradshaw & Garbarino, 2004; Duru et al., 2019; Levendosky et al., 2012). However, most studies explored the relationship between adult attachment and IPV perpetration (Gormley & Lopez, 2010; McClure & Parmenter, 2020). Specifically, individuals with insecure attachment present intense fear of abandonment or rejection and activate their aggressive behaviors to control their partners (Gormley & Lopez, 2010). Regarding IPV victimization circumstances, few studies have examined attachment security among IPV survivors. Specifically, simultaneously exploring attachment with primary caregivers in childhood and attachment with romantic partners in adulthood could capture the complexity of the impact of IPV victimization experiences on relational and emotional outcomes. Ponti and Tani (2019) investigated both childhood attachment and adult attachment among 60 women who experienced IPV and indicated that the attachment to the mother could influence IPV victimization both directly and indirectly through the mediation effect of adult attachment with romantic partners. In other words, attachment with the mother could serve as a protector for not entering a violent romantic relationship or healthily managing the aftermath of traumatic experiences.

Childhood attachment has been identified as a potential moderator that may contribute to the variations of the healing process among IPV survivors in a small but growing number of studies (e.g., Scott & Babcock, 2010). Pang and Thomas (2020) examined the moderating role of childhood attachment on the relationship between exposure to domestic violence in adolescence and psychological outcomes and adult life satisfaction with a sample of 351 adult college students. They found that childhood attachment moderated the relationship between IPV exposure and adult life satisfaction but not psychological outcomes. This study provides empirical support for the moderating role of childhood attachment on early IPV exposure and later adult psychological and relationship outcomes. Given the context in which IPV occurs in the intimate relationships, not addressing the association between childhood attachment and adult attachment together would not fully capture the complexity of the attachment process in the adult population. It is possible that the relationship between IPV victimization and adult attachment security would be attenuated in conditions of childhood attachment. Therefore, the moderation effect of childhood attachment in the context of IPV needs to be empirically substantiated.

Childhood Attachment, IPV Victimization, and Self-Esteem

Self-esteem generally refers to a person’s overall evaluation and attitude toward themself (Rosenberg, 1965). Experiencing IPV was found to have detrimental effects on an individual’s self-esteem; IPV survivors often have lower levels of self-esteem than non-abused individuals (Childress, 2013; Karakurt et al., 2014; Tariq, 2013). Experiencing IPV (e.g., emotional and psychological abuse) can lead to feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness, making it difficult for survivors to maintain autonomy and make decisions that are in their best interest (Tariq, 2013). IPV survivors consistently reported feeling burdened with a sense of guilt, shame, and self-blame for being victimized (Lindgren & Renck, 2008). Unfortunately, this can contribute to a vicious cycle, as survivors who have low self-esteem are less likely to take steps to leave abusive relationships (Karakurt et al., 2014), which leads to further victimization (Eddleston et al., 1998). Understanding the link between IPV victimization and self-esteem is crucial, as rebuilding self-esteem can also help survivors develop stronger relationships with others, gain strength toward ending abusive relationships, reduce risks of mental health problems, and feel more empowered to seek help and support (Karakurt et al., 2022).

The development of the self can be seen to unfold in the context of attachment and the internalization of important others’ perceptions and expectations. Numerous studies have shed some light on the association between childhood attachment and self-esteem, suggesting that secure attachment with primary caregivers can serve as a key protective factor for developing higher levels of self-esteem (Shen et al., 2021; Wilkinson, 2004). In contrast, individuals who reported insecure attachment with their primary caregivers tended to demonstrate lower levels of self-esteem (Gamble & Roberts, 2005). However, interpersonal trauma such as IPV can produce long-term dysfunctions of self (Childress, 2013). Although no study has directly explored the moderating role of childhood attachment buffering the relationship between IPV and self-esteem, several studies have indicated that parental support serves as a moderator role in the relationship between interpersonal violence and self-esteem (Duru et al., 2019). Indeed, if a person had secure attachment experiences in childhood, they may have developed a positive sense of self-worth and the belief that they deserve love and respect, which could buffer the negative effects of IPV on their self-esteem. Considering the existing literature and theoretical explanations as a whole, it seems reasonable to postulate that childhood attachment might serve as a potential moderator of the association between IPV and self-esteem.

Taken together, the literature consistently supports the significance of exploring protective factors contributing to IPV survivors’ healing process, yet no study to date has investigated the potential moderating role of childhood attachment on the association between IPV, adult attachment, and self-esteem in a non-clinical diverse sample. In tackling these gaps, we pose two research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How is IPV associated with adult attachment and self-esteem?

RQ2: How does childhood attachment moderate the relationships between IPV, adult

attachment, and self-esteem?

We hypothesized that: 1) IPV victimization is significantly positively associated with adult attachment (i.e., anxious attachment, avoidant attachment) and negatively associated with self-esteem; 2) Childhood attachment moderates the relationship between IPV victimization and adult attachment (i.e., anxious attachment, avoidant attachment); and 3) Childhood attachment moderates the relationship between IPV victimization and self-esteem.

Method

Sampling Procedures

With approval from the university IRB, research recruitment information was posted on various social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Craigslist, university announcement boards). Individuals who were 18 years of age or older and able to fill out the questionnaire in English were eligible for the study. Participants were directed to an online Qualtrics survey to voluntarily complete the informed consent and the measures listed in the following section. At the end of the survey, participants were prompted to enter their email addresses to win one of 10 $15 e-gift cards. Their email addresses were not included for data analysis.

Participants

Of the 2,373 voluntary adult participants who took the survey, 1,708 (71.76%) individuals were retained for the final analysis, including 507 (29.68%) participants who experienced IPV in adulthood and 1,191 (69.73%) participants without a history of IPV in adulthood. We eliminated participants who either did not consent to the study (n = 36, 1.51%), were younger than 18 years old (n = 33, 1.39%), or did not complete 95% of the survey questions (n = 596, 25.11%). We examined whether those who were excluded from the sample because of missing or invalid data differed from those who were retained. There was a significant difference in age between the included sample (M = 28.89, SD = 12.38) and excluded sample (M = 32.10, SD = 13.51); t (2,255) = −3.48, p = 0.001. Therefore, excluding participants with missing data was less likely to significantly impact our results. Table 1 shows that 76.23% of the participants were female. The age range of the sample was broad, from 18 to 89 years old, with an average age of 30.

Table 1

Demographic and Key Variables Information (N = 1,708)

| Variables |

N |

Percent |

Range |

M(SD) |

| Childhood attachment |

1,708 |

100% |

1–5 |

3.34(0.92) |

| IPV status

IPV

Non-IPV |

1,698

507

1,191 |

99.41%

29.68%

69.73% |

0–1 |

|

| Self-Esteem |

1,704 |

99.77% |

3–40 |

26.98(7.46) |

| Anxious Attachment |

1,708 |

100% |

1–7 |

4.11(1.26) |

| Avoidant Attachment |

1,708 |

100% |

1–7 |

3.71(1.16) |

| Control Variables |

|

|

|

|

| Gender

Male

Female |

1,683

381

1,302 |

98.54%

22.31%

76.23% |

|

|

| Household Income

Less than $5,000

$5,000–$9,999

$10,000–$14,999

$15,000–$19,999

$20,000–$24,999

$25,000–$29,999

$30,000–$39,999

$40,000–$49,999

$50,000–$74,999

$75,000–$99,999

$100,000–$149,999

$150,000 or more |

1,514

183

96

119

83

98

78

128

141

239

143

139

67 |

88.64%

10.70%

5.60%

7.00%

4.90%

5.70%

4.60%

7.50%

8.30%

14.00%

8.40%

8.10%

3.90% |

|

|

Measures

Childhood Attachment

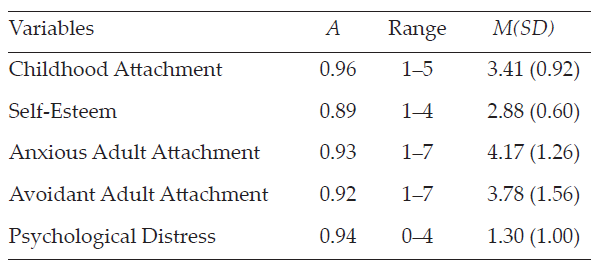

The parental attachment subscale of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) was used to measure childhood attachment. Participants rated their attachment to their parent(s) or caregiver(s) who had the most influence on them during their childhood. The subscale consists of 25 items divided into three dimensions, including 10 items on Trust (e.g., “My mother/father trusts my judgment”), nine items on Communication (e.g., “I can count on my mother/father when I need to get something off my chest”), and six items on Alienation (e.g., “I don’t get much attention from my mother/father”). Participants rated the items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never or never true) to 5 (almost always or always true). Responses were averaged, with a higher score reflecting more secure childhood attachment. This subscale has demonstrated relatively high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .93 (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987), and construct validity (Cherrier et al., 2023; Gomez & McLaren, 2007). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this subscale was .96.

Intimate Partner Violence

Participants’ experiences of IPV were assessed through the question “Have you ever experienced intimate partner violence (physical, sexual, or psychological harm) by a current or former partner or spouse since the age of 18?” Responses were coded as 1 = Yes, 0 = No.

Adult Attachment

Adult attachment was measured using the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR; Brennan et al., 1998). The ECR consists of 36 items with 18 items assessing each of the two dimensions: anxious attachment (e.g., “I worry about being abandoned”) and avoidant attachment (e.g., “I try to avoid getting too close to my partner/friends”). To reduce confounding factors with childhood attachment with their parent(s) or primary caregiver(s), we only assessed adult attachment with close friends and/or romantic partners. Responses were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Two scores were computed by averaging items on each subscale, with a higher score reflecting a higher level of anxious or avoidant attachment. Two subscales demonstrated high construct validity in various studies (Gormley & Lopez, 2010; Ponti & Tani, 2019) and a relatively high consistency for anxiety (α = .91) and avoidance (α = .94; Brennan et al., 1998). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the present study were .93 for anxiety and .92 for avoidance.

Self-Esteem

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965) is a 10-item self-report measure of overall feelings of self-worth or self-acceptance (e.g., “I am satisfied with myself”). All items were coded using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Items were summed, with a higher score indicating a higher level of self-esteem. RSES has been frequently used in various studies, demonstrating high reliability and validity (Brennan & Morris, 1997; Rosenberg, 1979). The Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was .89.

Control Variables

To make more accurate estimates, we included control variables that are potentially associated with IPV exposures, such as gender and household income. Gender was dummy coded as 1 = Male, 2 = Female.

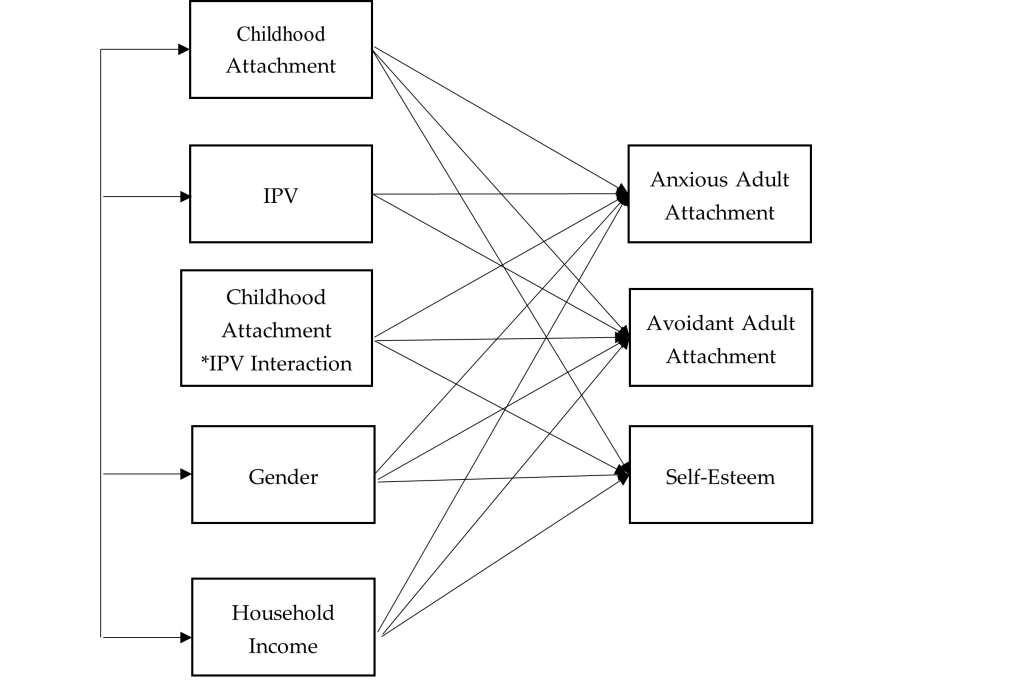

Data Analysis

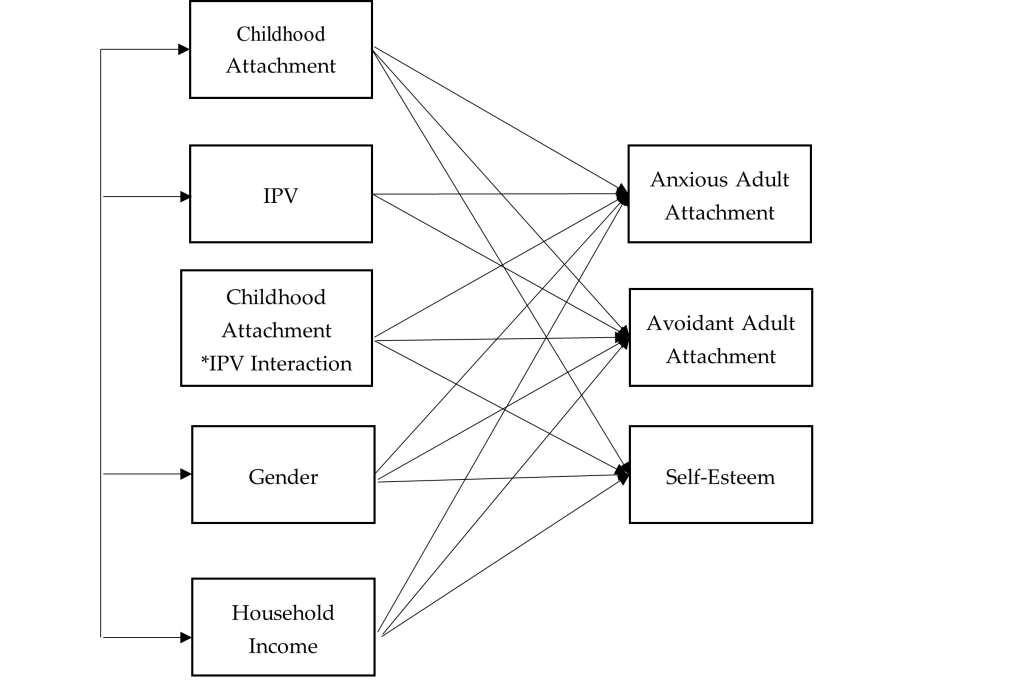

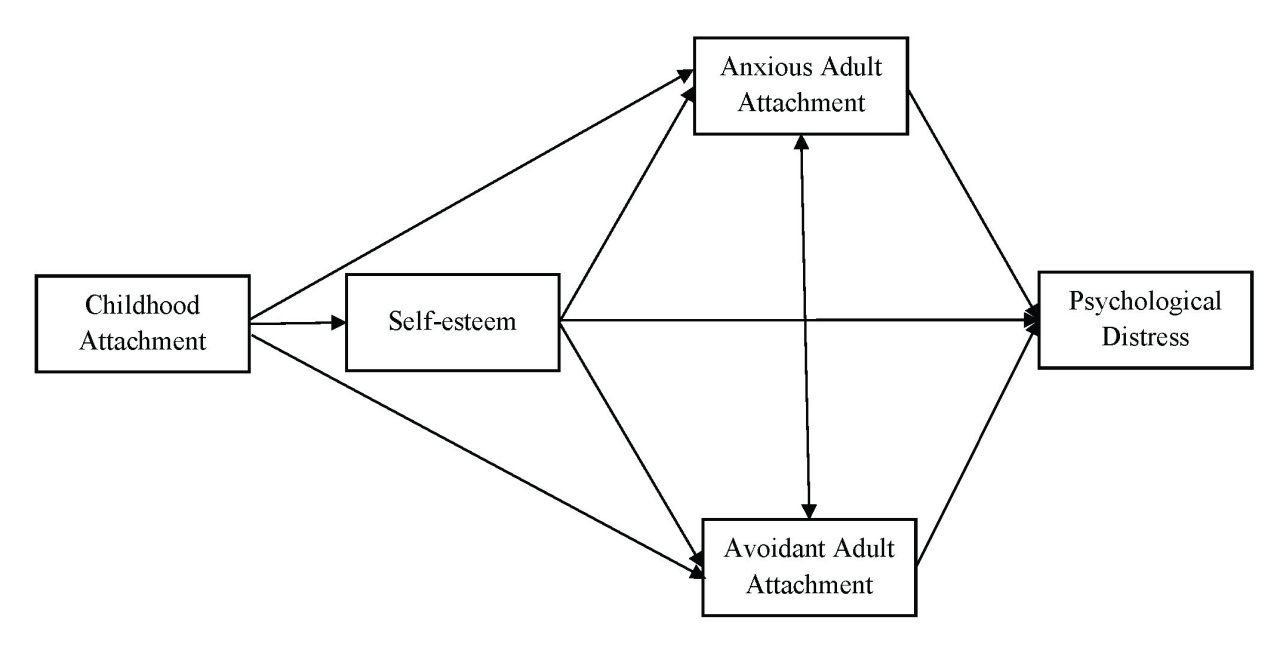

We used SPSS 27 for data preparation and Mplus 8 for data analysis. Missing data were treated with the full information maximum likelihood in Mplus as recommended (Acock, 2005). We examined all the bivariate relationships between all the variables within our study including IPV, childhood attachment, adult attachment (anxious and avoidant attachment), self-esteem, and control variables (i.e., gender and household income). We conducted path analysis to examine the moderating role of childhood attachment between IPV, self-esteem, and adult attachment (see Figure 1). We computed an interaction term by multiplying the predictor (IPV) and the moderator (childhood attachment). A moderation relationship is identified if the interaction item significantly predicts the dependent variables (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The goodness of model fit was evaluated by recommended indices with a non-significant chi-square value, RMSEA < .08, CFI > .90, TLI > .90, and SRMR < .05 (Hooper et al., 2008).

Figure 1

Path Analysis: Moderating Effect of Childhood Attachment on the Relationship Between IPV, Self-Esteem, and Adult Attachment

Results

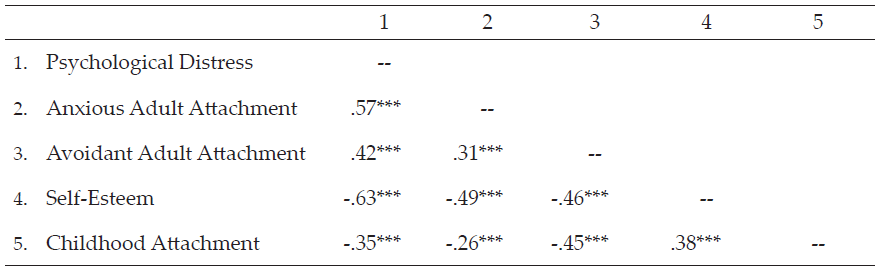

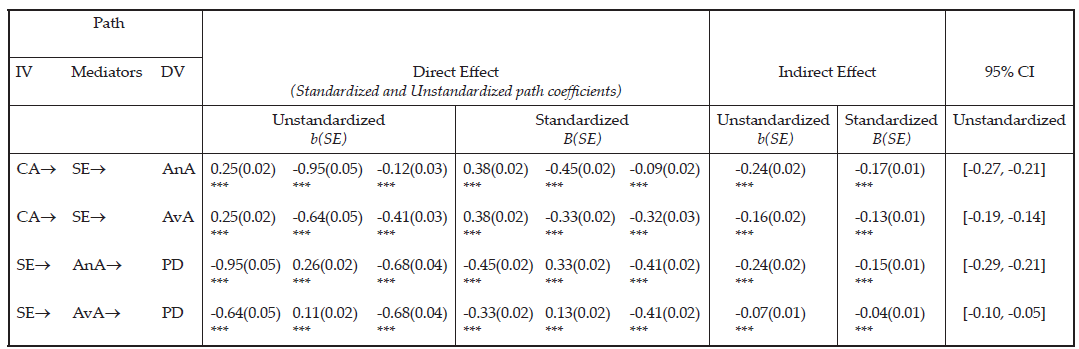

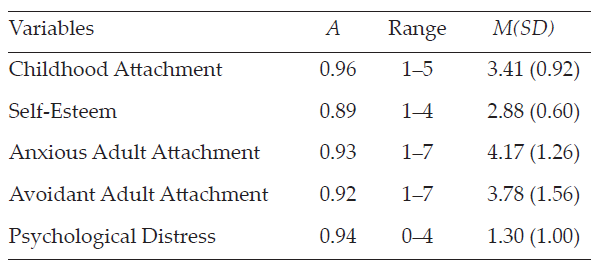

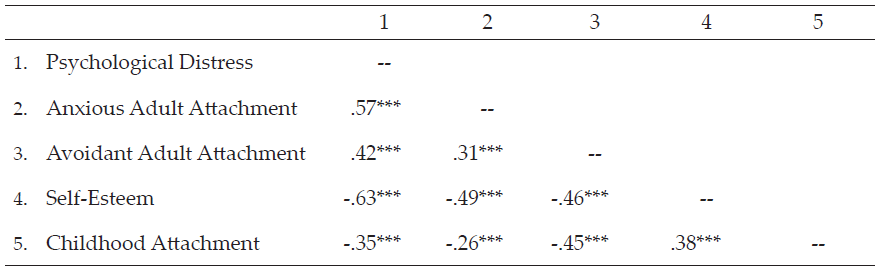

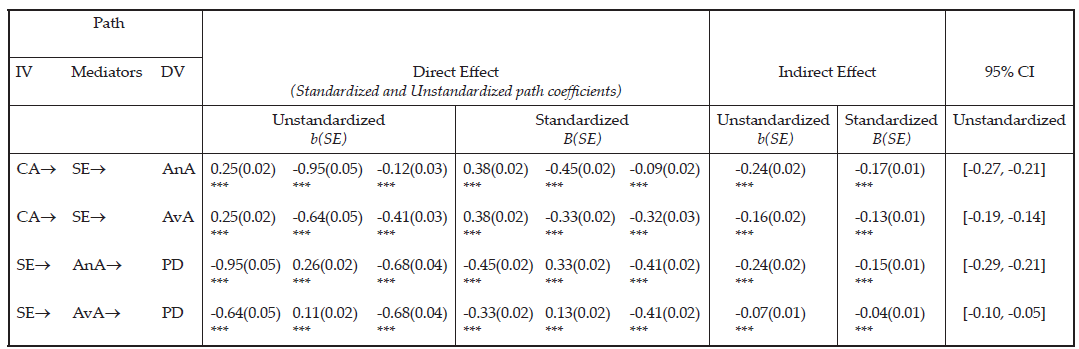

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of the study variables are demonstrated in Tables 1 and 2. Our model demonstrated good fit to the data, with χ2(4) = 41.90, p = .001, RMSEA = .07, 90% CI [.05, .08], CFI = .99, TLI = .99, SRMR = .02.

The standardized coefficients of the path model revealed that IPV survivors tended to have higher levels of anxious adult attachment (b = .67, p < .001) and avoidant adult attachment (b = .62, p < .001), and lower levels of self-esteem (b = −.29, p < .001) compared with participants without a history of IPV (see Table 3). Individuals with more secure childhood attachment tended to have lower levels of anxious adult attachment (b = −.38, p < .001) and avoidant adult attachment (b = −.31, p < .001), and higher levels of self-esteem (b = .22, p < .001). We found that childhood attachment buffered the relationship between IPV and self-esteem (b = .12, p < .001). Specifically, IPV survivors with more secure childhood attachment demonstrated higher levels of self-esteem. Although the moderation effect was statistically significant, the magnitude of the effect was small. Moreover, IPV survivors with more secure childhood attachment did not demonstrate significant differences on anxious or avoidant adult attachment compared to participants without a history of IPV.

Table 2

Bivariate Correlation Matrix of Variables

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| 1. Anxious Adult Attachment |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Avoidant Adult Attachment |

.40*** |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Self-Esteem |

−.18*** |

−.15*** |

– |

|

|

|

|

| 4. Childhood Attachment |

−.45*** |

−.47*** |

.18*** |

– |

|

|

|

| 5. IPV |

.26*** |

.54*** |

−.17*** |

−.31*** |

– |

|

|

| 6. Gender |

−.10*** |

−.06** |

.14*** |

−.01 |

−.08*** |

– |

|

| 7. Household Income |

.03 |

.08*** |

−.05* |

−.08** |

−.06* |

−.01 |

– |

*p < .05 (two-tailed). **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 3

Unstandardized and Standardized Path Coefficients (Standard Errors) for Path Analysis

| Parameter Estimates |

|

Anxious Adult

Attachment |

Avoidant Adult

Attachment |

Self-esteem |

| Childhood Attachment |

Unstandardized |

−.37(.01)*** |

−.33(.02)*** |

.26(.04)*** |

| |

Standardized |

−.38(.01)*** |

−.31(.02)*** |

.22(.03)*** |

| IPV |

Unstandardized |

.61(.01)*** |

.62(.02)*** |

−.33(.04)*** |

| |

Standardized |

.67(.01)*** |

.62(.02)*** |

−.29(.03)*** |

| IPV*Childhood Attachment

Interaction |

Unstandardized |

.00(.00) |

.01(.01) |

.10(.02)*** |

| Standardized |

.01(.01) |

.01(.01) |

.12(.02)*** |

| Control Variables |

| Gender |

Unstandardized |

−.03(.01)** |

−.08(.03)** |

.18(.06)** |

| |

Standardized |

−.02(.01)** |

−.04(.01)** |

.07(.02)** |

| Household Income |

Unstandardized |

.01(.00)*** |

.01(.00)*** |

−.02(.01)** |

| |

Standardized |

.02(.01)*** |

.04(.01)*** |

−.06(.02)** |

*p < .05 (two-tailed). **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Female participants tended to have lower levels of anxious (b = −.02, p < .01) or avoidant adult attachment (b = −.04, p < .01), and higher levels of self-esteem (b = .07, p < .01). Individuals with higher household income reported higher levels of anxious adult attachment (b = .02, p < .001), avoidant adult attachment (b = .04, p < .001), and lower levels of self-esteem (b = −.06, p < .01).

Discussion

Although most existing literature predominantly focuses on revealing how the attachment style of the IPV perpetrators may influence their behavior (Velotti et al., 2018), our study contributes to the field by exploring the potential association between IPV victimization and adult attachment. Using a non-clinical sample, this study identified a positive association between IPV victimization and adult insecure attachment, including both anxious and avoidant dimensions. Meanwhile, a negative association was observed between IPV victimization and self-esteem. These findings concur with the tenets of attachment theory, which posits that individuals who experienced IPV would have a sense of betrayal of trust within intimate relationships. Rather than serving a secure attachment base in intimate adult relationships, IPV experience altered internal models of self as a victim and the other as perpetrator if the individuals stay in the abusive relationships for long enough (Levendosky et al., 2012). IPV survivors may adopt maladaptive coping strategies to mitigate the distress stemming from such intimate relationships. Consequently, these individuals might manifest anxious or avoidant attachment (Levendosky et al., 2012). At the same time, our results indicating reduced self-esteem among IPV victims resonates with previous studies, underscoring the detrimental effects of IPV on self-esteem (Childress, 2013; Karakurt et al., 2014). Enduring undeserved maltreatment from partners can persistently undermine an individual’s sense of self-efficacy and competency (Tariq, 2013).

Our findings do not identify childhood attachment as a significant moderating factor between IPV victimization and insecure attachment in adulthood. There is currently no study to compare with this finding, as the present study is the first to investigate the moderating role of childhood attachment on the relationship between adult IPV victimization and adult attachment.

Although previous research implied that childhood attachment can mitigate the adverse effects of IPV on psychological health and adult life satisfaction (Pang & Thomas, 2020), those studies assessed IPV experiences during an individual’s childhood. Nevertheless, we speculate that IPV targets an individual’s sense of security, which is predominantly influenced by adult romantic relationships (Dutton & White, 2012). This IPV-related sense of security distinguishes itself from childhood attachment, which primarily arises from interactions between parents and children. For instance, the fear associated with intimate relationships and feelings of betrayal, as a result of sustained physical and emotional abuse from an intimate partner, may not be readily alleviated by the sense of security instilled by one’s primary caregivers during childhood. Survivors who were abused by their partner may attempt to manage their distress by deactivating their attachment system, which would reflect more insecure working models of self and others, less self-confidence, and lack of trust in others (Kobayashi et al., 2021).

Conversely, our research determined that childhood attachment acts as a moderator between IPV victimization and self-esteem, aligning with previous studies showing parental support as a vital protective mechanism for the self-esteem of individuals subjected to interpersonal violence (Duru et al., 2019). As posited by attachment theory, secure childhood attachment fosters a robust self-concept, equipping individuals with the belief that they are valuable and deserving of love (Bowlby, 1969). This foundational belief may serve as an effective counterbalance, attenuating the damage to self-esteem precipitated by IPV. We acknowledge that although the moderating effect of childhood attachment on the relationship between IPV victimization and self-esteem was statistically significant, the magnitude standardized coefficients were fairly low. One possible explanation could be that when transitioning to adulthood, individuals expand their social relationships with their peers, romantic partners, and offspring, which may increasingly take on their attachment organizations (Allen et al., 2018; Guarnieri et al., 2015). Future studies could further explore the level of effectiveness of childhood attachment mitigating the negative impact of IPV experience on interpersonal and intrapersonal outcomes in adulthood.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the present study adds important contributions to the literature on IPV victimization and attachment, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the dichotomous question of IPV could not fully capture all of the complexity of IPV victimization experiences. Future research should consider other factors related to IPV, including severity of the violence, types of IPV, age of onset, frequency, and duration. Second, retrospective reporting of childhood attachment with the primary caregiver(s) may lead to bias, or distortion in the recall of traumatic events from family of origin. However, previous studies have shown that retrospective reports only have a small amount of bias and that it is not strong enough to invalidate the results for adverse childhood experiences (Hardt & Rutter, 2004).

A growing body of literature has identified adult attachment as a risk factor of IPV (Doumas et al., 2008); here, we were not able to determine the causal relationship between adult attachment and IPV. We did conduct a path analysis using childhood attachment and adult attachment to predict IPV and self-esteem, but the model did not demonstrate a good fit. It is possible that attachment and IPV do not have a simple causal relationship; other childhood trauma experiences may contribute to the complexity of the IPV (Li et al., 2019).

Finally, not knowing the types of attachment in childhood limited our exploration regarding the changes of attachment styles from childhood to adulthood. The cross-sectional design of assessing childhood attachment and adult attachment concurrently did not provide sufficient evidence to determine the cause and effect. Bowlby (1969) believed that there is a continuity between childhood attachment and adult attachment over the life course. An individual’s security in adult relationships may be a partial reflection of their experiences with primary caregivers in early childhood (Ammaniti et al., 2000). However, one of the common misconceptions about attachment theory is that attachment is always stable from infancy to adulthood (Hazan & Shaver, 1994). It is possible that adults’ attachment patterns would change if their relational experiences were disturbed by relational trauma such as IPV (West & George, 1999) or childhood trauma (Shen & Soloski, 2024), which partially explains that childhood attachment is not a significant moderator between IPV and adult attachment from our findings. Future research could conduct longitudinal studies to examine the changes of attachment and how childhood trauma and IPV influences attachment over time.

Implications

The findings of the present study provide insights that may inform clinical interventions for adult survivors who have experienced IPV to rebuild trusting interpersonal relationships and relationships with self. First, IPV experiences were significantly associated with anxious and avoidant adult attachment. During a traumatic experience, such as IPV, the attachment security system is activated, and survivors are in a surviving mode and tend to seek protection. Unfortunately, IPV involves power, control, and betrayal within an intimate relationship, which may damage internal working models of self and others if they stay for long enough (Levendosky et al., 2012). Thus, clinical interventions could focus on altering survivors’ negative internal working models to increase security within non-abusive close relationships. Close friends and family members could remain as a secure base for IPV survivors while they rebuild their personal and social lives that IPV have damaged. Additionally, therapeutic relationships could potentially serve as a secure base for survivors to explore their attachment behaviors. Survivors with avoidant attachment demonstrate deactivation attachment behaviors (Brenner et al., 2021), such as minimizing the impact of their trauma experiences, having a tendency to perceive and present themselves as strong, or avoiding discussing their trauma experiences to avoid the possible pain (Muller, 2009). Therefore, clinicians need to hold a safe space to challenge survivors with avoidant attachment to reactivate their attachment systems, such as by validating their avoidance and ambivalence or facilitating conversations to turn toward trauma-related experiences and emotions instead of turning away. Survivors with anxious attachment, on the other hand, demonstrate hyperactivation attachment behaviors, including fear of rejection and abandonment, hypersensitivity to and preoccupation with relationships and intimacy, utilization of negative emotional regulation strategies, as well as difficulties with leaving abusive relationships (Kural & Kovacs, 2022; Velotti et al., 2018). Clinicians could teach anxious-attached survivors some effective coping strategies, including self-regulation skills, creating boundaries, establishing safety plans, maintaining relationships with others, and increasing self-compassion (Rizo et al., 2017), which may help them to perceive themselves as worthy, lovable, and less dependent on others.

Furthermore, group counseling is a powerful way to learn about trusting oneself and others and to improve interpersonal relationship skills. Clients’ attachment patterns will be activated through interactions with the group members and the facilitators. Clients with anxious attachment tend to react to group members’ rejections, while clients with avoidant attachment tend to demonstrate withdrawal behaviors (e.g., disengagement; Zorzella et al., 2014). Therefore, when working with these clients, clinicians should stimulate the change of internal working models by using the group as a secure base to foster corrective emotional exchanges that challenge group members’ maladaptive beliefs about themselves and others (Marmarosh et al., 2013).

One of the important findings of the current study is that childhood attachment with the primary caregiver(s) buffered the relationship between IPV and self-esteem. From a clinical point of view, the result may bring hope for adult survivors of interpersonal violence regarding their healing process; primary caregivers could still serve as a secure base to offer a crucial opportunity to strengthen the internal working models that would positively affect later adjustment. Counselors could assess survivors’ attachment with their primary caregivers and give them autonomy to determine if it is beneficial to get their non-abusive primary caregivers involved in the treatment to provide support. Although the moderation result from the present study was statistically significant, the magnitude of moderating effect was small. During adulthood, individuals expand their relationship networks with their peers (e.g., friends) and romantic partners, as these relationships become more central in their daily life (Guarnieri et al., 2015). Therefore, the effectiveness of childhood attachment mitigating the adverse effect of IPV in adulthood clinically needs to be further investigated.

Conclusion

The present study empirically examines the moderation role of childhood attachment on the association between IPV, adult attachment, and self-esteem. Specifically, we found that childhood attachment was a significant moderator buffering the relationship between the experience of IPV and self-esteem. A theoretical and empirical understanding of the role of attachment in the context of IPV has implications for researchers and clinicians working with survivors and their families.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Acock, A. C. (2005). Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 1012–1028.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00191.x

Allen, J. P., Grande, L., Tan, J., & Leob, E. (2018). Parent and peer predictors of change in attachment security from adolescence to adulthood. Child Development, 89(4), 1120–1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12840

Ammaniti, M., Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Speranza, A. M., & Tambelli, R. (2000). Internal working models of attachment during late childhood and early adolescence: An exploration of stability and change. Attachment & Human Development, 2(3), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730010001587

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16(5), 427–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02202939

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Black, M. C., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Walters, M. L., Merrick, M. T., Chen, J., & Stevens, M. R. (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 summary report. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss, Vol. 2: Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books.

Bradshaw, C. P., & Garbarino, J. (2004). Social cognition as a mediator of the influence of family and community violence on adolescent development: Implications for intervention. In J. Devine, J. Gilligan, K. A. Miczek, R. Shaikh, & D. Pfaff (Eds.), Youth violence: Scientific approaches to prevention (pp. 85–105). New York Academy of Sciences.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford.

Brennan, K. A., & Morris, K. A. (1997). Attachment styles, self-esteem, and patterns of seeking feedback from romantic partners. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297231003

Brenner, I., Bachner-Melman, R., Lev-Ari, L., Levi-Ogolnic, M., Tolmacz, R., & Ben-Amitay, G. (2021). Attachment, sense of entitlement in romantic relationships, and sexual revictimization among adult CSA survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(19–20), NP10720–NP10743. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519875558

Burke, J. G., Thieman, L. K., Gielen, A. C., O’Campo, P., & McDonnell, K. A. (2005). Intimate partner violence, substance use, and HIV among low-income women: Taking a closer look. Violence Against Women, 11(9), 1140–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801205276943

Cherrier, C., Courtois, R., Rusch, E., & Potard, C. (2023). Parental attachment, self-esteem, social problem-solving, intimate partner violence victimization in emerging adulthood. The Journal of Psychology, 157(7), 451–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2023.2242561

Childress, S. (2013). A meta-summary of qualitative findings on the lived experience among culturally diverse domestic violence survivors. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34(9), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2013.791735

Doumas, D. M., Pearson, C. L., Elgin, J. E., & McKinley, L. L. (2008). Adult attachment as a risk factor for intimate partner violence: The “mispairing” of partners’ attachment styles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(5), 616–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260507313526

Duru, E., Balkis, M., & Turkdoğan, T. (2019). Relational violence, social support, self-esteem, depression and anxiety: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2404–2414.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01509-2

Dutton, D. G., & White, K. R. (2012). Attachment insecurity and intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(5), 475–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.07.003

Gamble, S. A., & Roberts, J. E. (2005). Adolescents’ perceptions of primary caregivers and cognitive style: The roles of attachment security and gender. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29, 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-005-3160-7

Gilbert, L. K., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M., & Kresnow, M. (2023). Intimate partner violence and health conditions among U. S. adults—National Intimate Partner Violence Survey, 2010–2012. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(1–2), 237–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221080147

Gomez, R., & McLaren, S. (2007). The inter-relations of mother and father attachment, self-esteem and aggression during late adolescence. Aggressive Behavior, 33(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20181

Gormley, B., & Lopez, F. G. (2010). Psychological abuse perpetration in college dating relationships: Contributions of gender, stress, and adult attachment orientations. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(2), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509334404

Guarnieri, S., Smorti, M., & Tani, F. (2015). Attachment relationships and life satisfaction during emerging adulthood. Social Indicators Research, 121(3), 833–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0655-1

Hardt, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1994). Deeper into attachment theory. Psychological Inquiry, 5(1), 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0501_15

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

Jewkes, R., Fulu, E., Tabassam Naved, R., Chirwa, E., Dunkle, K., Haardörfer, R., Garcia-Moreno, C., & the UN Multi-country Study on Men and Violence Study Team. (2017). Women’s and men’s reports of past-year prevalence of intimate partner violence and rape and women’s risk factors for intimate partner violence: A multicountry cross-sectional study in Asia and the Pacific. PloS Medicine, 14(9), e1002381. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002381

Karakurt, G., Koç, E., Katta, P., Jones, N., & Bolen, S. D. (2022). Treatments for female victims of intimate partner violence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 793021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.793021

Karakurt, G., Smith, D., & Whiting, J. (2014). Impact of intimate partner violence on women’s mental health. Journal of Family Violence, 29(7), 693–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9633-2

Kobayashi, J. E., Levendosky, A. A., Bogat, G. A., & Weatherill, R. P. (2021). Romantic attachment as a mediator of the relationships between interpersonal trauma and prenatal representations. Psychology of Violence, 11(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000361

Kural, A. I., & Kovacs, M. (2022). The role of anxious attachment in the continuation of abusive relationships: The potential for strengthening a secure attachment schema as a tool of empowerment. Acta Psychologica, 225, 103537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103537

Levendosky, A. A., Lannert, B., & Yalch, M. (2012). The effects of intimate partner violence on women and child survivors: An attachment perspective. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 40(3), 397–433.

https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2012.40.3.397

Li, S., Zhao, F., & Yu, G. (2019). Childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence victimization: A meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.012

Lindgren, M. S., & Renck, B. (2008). “It is still so deep-seated, the fear”: Psychological stress reactions as consequences of intimate partner violence. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15(3), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01215.x

Lopez, F. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). Dynamic processes underlying adult attachment organization: Toward an attachment theoretical perspective on the healthy and effective self. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.47.3.283

Marmarosh, C. L., Markin, R. D., & Spiegel, E. B. (2013). Attachment in group psychotherapy. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14186-000

Matheson, F. I., Daoud, N., Hamilton-Wright, S., Borenstein, H., Pedersen, C., & O’Campo, P. (2015). Where did she go? The transformation of self-esteem, self-identity, and mental well-being among women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Women’s Health Issues, 25(5), 561–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.04.006

McClure, M. M., & Parmenter, M. (2020). Childhood trauma, trait anxiety, and anxious attachment as predictors of intimate partner violence in college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(23–24), 6067–6082. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517721894

McLaughlin, J., O’Carroll, R. E., & O’Connor, R. C. (2012). Intimate partner abuse and suicidality: A systemic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(8), 677–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.08.002

Meeker, K. A., Hayes, B. E., Randa, R., & Saunders, J. (2020). Examining risk factors of intimate partner violence victimization in Central America: A snapshot of Guatemala and Honduras. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 68(5), 468–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X20981049

Moretti, M. M., & Peled, M. (2004). Adolescent-parent attachment: Bonds that support healthy development. Paediatrics & Child Health, 9(8), 551–555. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/9.8.551

Muller, R. T. (2009). Trauma and dismissing (avoidant) attachment: Intervention strategies in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015135

Pang, L. H. G., & Thomas, S. J. (2020). Exposure to domestic violence during adolescence: Coping strategies and attachment styles as early moderators and their relationship to functioning during adulthood. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 13(2), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-019-00279-9

Ponti, L., & Tani, F. (2019). Attachment bonds as risk factors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 1425–1432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01361-4

Rizo, C. F., Givens, A., & Lombardi, B. (2017). A systematic review of coping among heterosexual female IPV survivors in the United States with a focus on the conceptualization and measurement of coping. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.03.006

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. Basic Books.

Sayed, S., Iacoviello, B. M., & Charney, D. S. (2015). Risk factors for the development of psychopathology following trauma. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17, 70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0612-y

Scott, S., & Babcock, J. C. (2010). Attachment as a moderator between intimate partner violence and PTSD symptoms. Journal of Family Violence, 25(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-009-9264-1

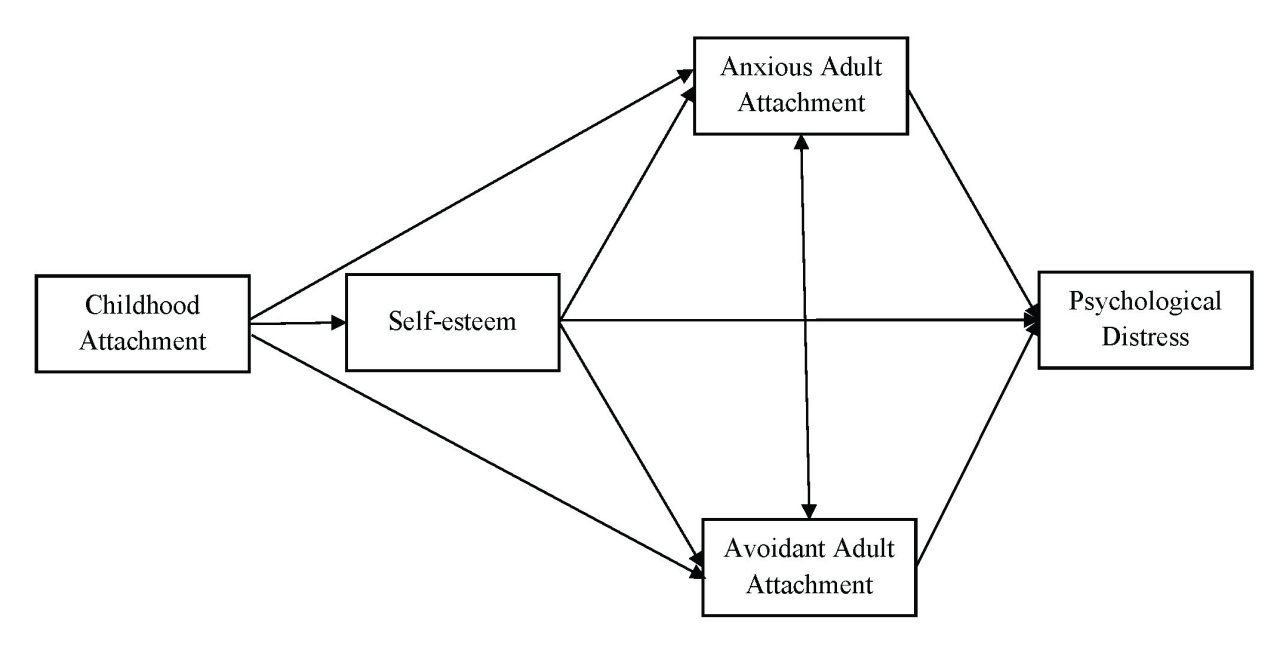

Shen, F., Liu, Y, & Brat, M. (2021). Attachment, self-esteem, and psychological distress: A multiple-mediator model. The Professional Counselor, 11(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.15241/fs.11.2.129

Shen, F., & Soloski, K. L. (2024). Examining the moderating role of childhood attachment for the relationship between child sexual abuse and adult attachment. Journal of Family Violence, 39, 347–357.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00456-9

St. Vil, N. M., Carter, T., & Johnson, S. (2021). Betrayal trauma and barriers to forming new intimate relationships among survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7–8), NP3495–NP3509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518779596

Sutton, T. E. (2019). Review of attachment theory: Familial predictors, continuity and change, and intrapersonal and relational outcomes. Marriage & Family Review, 55(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2018.1458001

Tariq, Q. (2013). Impact of intimate partner violence on self esteem of women in Pakistan. American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 1(1), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.11634/232907811604271

Velotti, P., Beomonte Zobel, S., Rogier, G., & Tambelli, R. (2018). Exploring relationships: A systematic review on intimate partner violence and attachment. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01166

West, M., & George, C. (1999). Abuse and violence in intimate adult relationships: New perspectives from attachment theory. Attachment & Human Development, 1(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616739900134201

Wilkinson, R. B. (2004). The role of parental and peer attachment in the psychological health and self-esteem of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000048063.59425.20

Zorzella, K. P. M., Muller, R. T., & Classen, C. C. (2014). Trauma group therapy: The role of attachment and therapeutic alliance. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 64(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijgp.2014.64.1.24

Fei Shen, PhD, LMFT, is an assistant professor at Kean University. Ying Zhang, PhD, is an assistant professor at Clarkson University. Xiafei Wang, PhD, is an assistant professor at Syracuse University. Correspondence may be addressed to Fei Shen, 1000 Morris Ave., Union, NJ 07083, fshen@kean.edu.

May 22, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 1

Emily Horton

Body neutrality is a concept wherein individuals embody a neutral attitude toward the body that is realistic and flexible, appreciate and care for the function of the body, and acknowledge that self-worth is not defined by one’s outward appearance. Family behavior regarding body image has been related to higher levels of body dissatisfaction and unhealthy eating behavior among children and adolescents. Caregivers need knowledge and support on how to cultivate healthy body image for their children and adolescents. Limited studies explore how to parent in a way that promotes healthy relationships with one’s body, food, and exercise. I conducted a grounded theory study to explore the experiences of caregivers who integrate tenets of body neutrality. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 caregivers of children and adolescents who self-identified as approaching parenting from a place of body neutrality. Through constructivist grounded theory, I discerned insights regarding how caregivers can support their children and adolescents in developing healthy relationships with their bodies and how this corresponds with self-esteem. Considerations for counselors using body neutrality to support children, adolescents, and caregivers are provided.

Keywords: body neutrality, body image, parenting, children and adolescents, self-esteem

Body image and related low self-esteem are frequently under-addressed or unaddressed in counseling children, adolescents, and their caregivers (Damiano et al., 2020). Too often, counselors may take a reactive approach to addressing unhealthy relationships with food, bodies, and exercise in the family system, such as counseling after an adolescent is diagnosed with an eating disorder (Liechty et al., 2016). Thus, counselors may benefit from considering how to take a preventative, proactive approach to supporting children’s mental health specific to their relationship with food, bodies, and movement (Siegel et al., 2021). Because the family system has tremendous impact on children’s body image and relationship with food, counselors need to consider how to provide appropriate psychoeducation and support to caregivers on how to manage food and body talk (Gutin, 2021). Positive caregiver influence on body image can prevent disordered eating, negative body image, and low self-worth, and many families need a licensed mental health professional to cultivate said positive influence (Veldhuis et al., 2020).

Researchers have found that children as young as 3 to 5 years old experience body image issues (Damiano et al., 2015; Dittmar et al., 2006). Caregivers often communicate body dissatisfaction, engage in dieting, and demonstrate a drive for thinness, messages that children can internalize (National Eating Disorders Association, 2022). Families can inadvertently pass down unhealthy ideals regarding body image to their children (Kluck, 2010). Kluck (2010) emphasized that a family’s focus on appearance was related to their child’s body image dissatisfaction, and the dissatisfaction predicted increased disordered eating. Counselors with appropriate training can play an important role in mitigating the harmful cycle before disordered thinking turns into disordered eating (Klassen, 2017). Counselors have the unique opportunity to support families in encouraging a healthy relationship with their bodies (Horton, 2023; Horton & Powers, 2024).

In this study, I sought to explore the experiences of caregivers who integrate tenets of body neutrality. Body neutrality is a concept wherein individuals embody a neutral attitude toward the body that is realistic and flexible, appreciate and care for the function of the body, and acknowledge that self-worth is not defined by one’s outward appearance (Pellizzer & Wade, 2023). Examples of body neutrality can include not describing food as healthy or unhealthy, talking about what our bodies do for us rather than what they look like, and moving for enjoyment rather than to burn calories. Because the tripartite model emphasizes that parental influence, in addition to peer and media influence, is significant for children’s body image development, I explored existing research on parental influence on body image and self-esteem (Thompson et al., 1999).

Parental Influence on Body Image and Self-Esteem

Some family members negatively impact children’s and adolescents’ body image (Pursey et al., 2021). Neumark-Sztainer et al. (2010) found that over half of the adolescents in their study experienced weight-based and appearance-based teasing from family, and these experiences correlated to higher levels of body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, and related mental health difficulties, such as depression. Parental influence on body image includes both direct (e.g., criticism about their child’s weight) and indirect (e.g., parents’ attitudes about their own bodies, food, and exercise) behaviors (Rodgers & Chabrol, 2009). Abraczinskas and colleagues (2012) conducted a study exploring parent direct influence, including weight- and eating-related comments, and modeling, including parental modeling of dieting and related behavior. In the study of over 360 participants, Abraczinskas and colleagues found that parental influence is a risk factor in the development of a drive for thinness, body shape dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptomology.

Moreover, Wymer and colleagues (2022) emphasized the importance of parent engagement in body image and self-esteem development. Often, families recognize the importance of discussing body image with their children but do not feel confident or competent in doing so (Siegel et al., 2021). The lack of confidence and competence leads to messages about health being conflated with messages about thinness (Siegel et al., 2021). In addition, researchers highlighted that although parental influence has a significant impact on body image and self-esteem, siblings, friends, and the media are also perceived to have influence over youth’s feelings about their bodies (Ricciardelli et al., 2000). The exiguous literature on parental influence on body image repeatedly emphasizes the negative impact of parents on body image yet seldom explores preventative and therapeutic ways of promoting healthy body image (Phares et al., 2004). Thus, I sought to explore how counselors might integrate body neutrality when supporting families and provide early intervention and prevention for adverse relationships with food, body, and movement.

Body Neutrality

Body neutrality is a concept wherein individuals accept their bodies as a vessel that carries them through life, and as such, do not attach positive or negative feelings to their physicality. For example, body neutrality can entail nurturing and respecting the body, being mindful of body talk, engaging in body gratitude and functionality appreciation, and recognizing self-worth that is not focused on appearance (Pellizzer & Wade, 2023). Body neutrality is an approach taken to help with the healing of body image, particularly in the field of eating disorders (Perry et al., 2019). Body neutrality tenets appear to be integral in the prevention of body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating (Herle et al., 2020). Practicing body neutrality positively impacts body satisfaction, self-esteem, and negative affect with adults, though continued empirical research is needed on its impact with youth (Walker et al., 2021). Although counselors and other allied professionals integrate body neutrality into their clinical practice, there is minimal research on its efficacy outside of eating disorder treatment. Existing research has emphasized the need for counseling approaches with youth that highlight body neutrality tenets, such as mindful eating and awareness-building conversations about societal messaging (Klassen, 2017). However, researchers have yet to explore how body neutrality could be integrated into a parenting approach. The bulk of the limited understanding of body neutrality is treatment based, rather than prevention oriented.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to cultivate a grounded theory or an abstract theoretical understanding of body neutral parenting (Charmaz, 2014). Further insight into the experiences, challenges, and potential barriers in parenting with body neutrality can enable a deeper understanding of how parents seek to promote healthy body image and self-esteem for children and adolescents. In this study, I aimed to offer a newfound understanding to mental health professionals supporting children, adolescents, and caregivers in the areas of body, food, movement, and related mental health implications.

Method

Methodology

To address the paucity of literature, a grounded theory study was conducted to examine the following research question: How do caregivers conceptualize and actualize body neutral parenting with their children? The study derived from constructivist grounded theory (CGT; Charmaz, 2014). CGT is an interpretative, qualitative methodology that acknowledges that researchers and participants co-create the theory (Charmaz, 2014). Given a desire to understand how caregivers conceptualize and utilize body neutral parenting, CGT was deemed appropriate. The purpose of the study was to generate a new theory through inductive analysis of data gleaned from caregivers who self-identify as using body neutral parenting.

Role of the Researcher

Congruent with CGT, I maintained a position of distant expert (Charmaz, 2014). The theoretical meaning was constructed by turning participants’ experiences into digestible theoretical interpretations. While staying as true to the experiences of the participants as possible, I reconstructed the participants’ stories in the development of the grounded theory via balancing conceptual analysis of participants’ stories and creating a sense of their presence in the narrative (Mills et al., 2006). I sought to examine the impact of my privilege and preconceptions as a White, cisgender woman and professional in the field of mental health counseling, with experience supporting families navigating eating disorders and disordered eating (Charmaz, 2014). Also, as a parent who integrates body neutrality into my approach with my child, I practiced reflexive journaling and other trustworthiness strategies to bracket my biases throughout the study.

Participant Recruitment

I obtained IRB approval prior to data collection. Per the IRB, all participants verbally consented before partaking in the research study. I used purposive sampling (Patton, 2014) for participant selection. Selection criteria included: (a) being a caregiver to at least one child under the age of 18, (b) identifying as integrating body neutrality into their parenting approach, and (c) willingness to participate in an interview lasting roughly 1 hour. I circulated electronic flyers detailing the focus of the study to social media pages for caregivers and professional networks. The recruitment flyers provided examples of body neutral parenting, including not describing food as healthy or unhealthy, talking about what our bodies do for us rather than what they look like, and moving for enjoyment rather than to burn calories.

Ten participants were interviewed. Of the 10 participants, nine identified as cisgender women and one identified as nonbinary. All 10 participants described themselves as being middle class. Nine participants were married and one was single. All of the participants had graduate-level or doctorate-level educations; four had master’s degrees and six had doctoral degrees. Participants lived in seven different states and two different countries. Participants had at least one child, with the number of children ranging from 1 to 5. Table 1 provides detailed demographic data.

Table 1

Participants’ Demographic Data

| Pseudonym |

Age |

Race |

Number

of Children |

Age of Children |

Race of Children |

| Logan |

27 |

White |

1 |

20 months |

White |

| Esmeralda |

38 |

Hispanic |

2 |

8 and 5 years |

White |

| Imani |

29 |

Black, White |

2 |

6 and 3 years |

White |

| Kimberly |

33 |

White |

2 |

5 and 2 years |

White |

| Heather |

42 |

White |

2 |

3 years, 8 months |

White |

| Cassie |

45 |

White |

5 |

16, 13, 11, 9, and 7 years |

White |

| Shanice |

36 |

African American |

4 |

15, 9, and 2 years; 4 months |

African American |

| Scarlett |

36 |

White |

3 |

17, 5, and 4 years |

White |

| Leilani |

43 |

White |

1 |

9 years |

Polynesian, White |

| Jennifer |

36 |

White |

1 |

2 years |

Middle Eastern, White |

Data Collection and Analysis

As guided by Charmaz’s (2014) CGT protocol, data collection and data analysis proceeded simultaneously, and the inclusion criteria evolved to include caregivers with children of all ages. The semi-structured interviews occurred via confidential videoconferencing software and lasted between 60 and 75 minutes. Interviews were an open-ended, detailed exploration of an aspect of life in which the participants had substantial experience and considerable insight: parenting with body neutrality principles (Charmaz & Liska Belgrave, 2012). During the interviews, I inquired about caregivers’ experiences, challenges, and insights of body neutral parenting. With the emergent categories, the guide evolved to emphasize the nuances of the parenting approach in alignment with three-cycle coding or focused coding (Charmaz, 2014).

Grounded theorists try to elicit their participants’ stories and attend to whether the participants’ interpretations are theoretically plausible (Charmaz & Liska Belgrave, 2012). As such, the interview protocol began with an initial open-ended question: “Tell me about a time in which you used body neutral parenting.” Then, I asked intermediate questions, such as “How, if at all, have your thoughts and feelings about body neutral parenting changed since your child was born?” I also asked ending questions, including: “How has taking the approach with your children impacted you as a parent? As a person?” The interview questions were informed by the literature and were reviewed by another content matter expert.

In addition to the in-depth interview, I used information from other data sources to support the depth of the data and theory construction. Other triangulated data sources included field notes of observations during the interviews, a reflexive journal, literature and previous research on body neutrality, and a demographic survey. In this way, the constant comparative analysis unique to CGT increases rigor through complex coding procedures more so than other methods of qualitative data analysis (Hays & McKibben, 2021). The constant comparative analysis examines nuanced relationships between participants through negative case analysis to strengthen findings (Hays & McKibben, 2021).

Three-cycle coding and constant comparative analysis drove the data analysis process (Charmaz, 2014). Through the data analysis process, I constantly compared data (Mills et al., 2006). Inductive in nature, the constant comparison through the data analysis grounded my theories from the participants’ experiences (Mills et al., 2006). In alignment with CGT, I coded the interviews through a fluid process of initial coding, focused coding, and theoretical coding. During initial coding, I focused on “fragments of data,” such as words, lines, segments, and incidents (Charmaz, 2014, p. 109). The initial coding process not only included the transcripts, but also continued the interaction and data collection to facilitate the continuous analytical process. I also engaged with focus coding, wherein I used the most significant and frequent codes that made the most analytic sense (Charmaz, 2014). The focused codes were more theoretical than line-by-line coding practices. I engaged in theoretical coding of the data; theoretical coding is a way of “weaving the fractured story back together” (Charmaz, 2014, p. 63). In accordance with Charmaz (2014), theoretical coding involved clarifying the “general context and specific conditions” and discovering “participants’ strategies for dealing with them” (p. 63). As I moved throughout the three-cycle coding process, the number of codes, categories, and emerging core categories decreased and refined, leaving me with the final core categories described below (Khanal, 2018).

Rigor and Trustworthiness

Throughout the totality of the research process, I engaged with five strategies to ensure trustworthiness. In the data analysis process, significant care was taken to ground analytic claims in the data obtained and remain true to the raw material provided by participants (Charmaz, 2014). I fostered trustworthiness through member checking and memo-writing (Creswell & Poth, 2017). I sent the transcript and the themes to participants and had six of 10 participants verify the themes as being congruent with their experiences. The other participants did not respond to the email with the transcript. Memo-writing was critical in constructing theoretical categories (Charmaz, 2014). I stopped and analyzed my ideas about the codes and emerging categories via memo-writing. Successive memos kept me immersed in the analysis and increased the abstraction of my ideas (Charmaz, 2014). In the theory construction, I also triangulated data sources, including semi-structured interviews, field notes of observations during the interviews, memo-writing, literature and previous research on body neutrality, and a demographic survey. Charmaz (2014) emphasized the importance of “thick descriptions” (p. 14), which I captured via writing extensive field notes of observations during the interviews and compiling detailed narratives from transcribed tapes of interviews.

I also shared my memos and data analysis process with an external auditor (Hays & McKibben, 2021). The external auditor was a researcher with experience in qualitative research and content familiarity. After the external auditor reviewed the data analysis trail, including the three stages of coding, I reviewed her written feedback and we met to process the feedback. The external auditor offered several pieces of feedback regarding the analytic process, including leaning more into the theory rather than the stories and removing quotes that captured pieces outside of the theory (i.e., removing content rooted in diet culture and body positivity). Feedback was integrated to strengthen the study’s development and explication of the theory based on data.

Results

This study involved the caregivers and researcher co-constructing the parenting theory while integrating body neutrality concepts. The theory stemmed from the perspectives shared by caregivers who parent in such a way as to promote body acceptance, such as focusing on what our bodies can do for us, avoiding body talk, eating the foods we want to eat, listening to our bodies, not focusing compliments on appearance, etc. As such, the grounded theory below explains caregivers interacting and experiencing body neutral parenting (Charmaz, 2014).

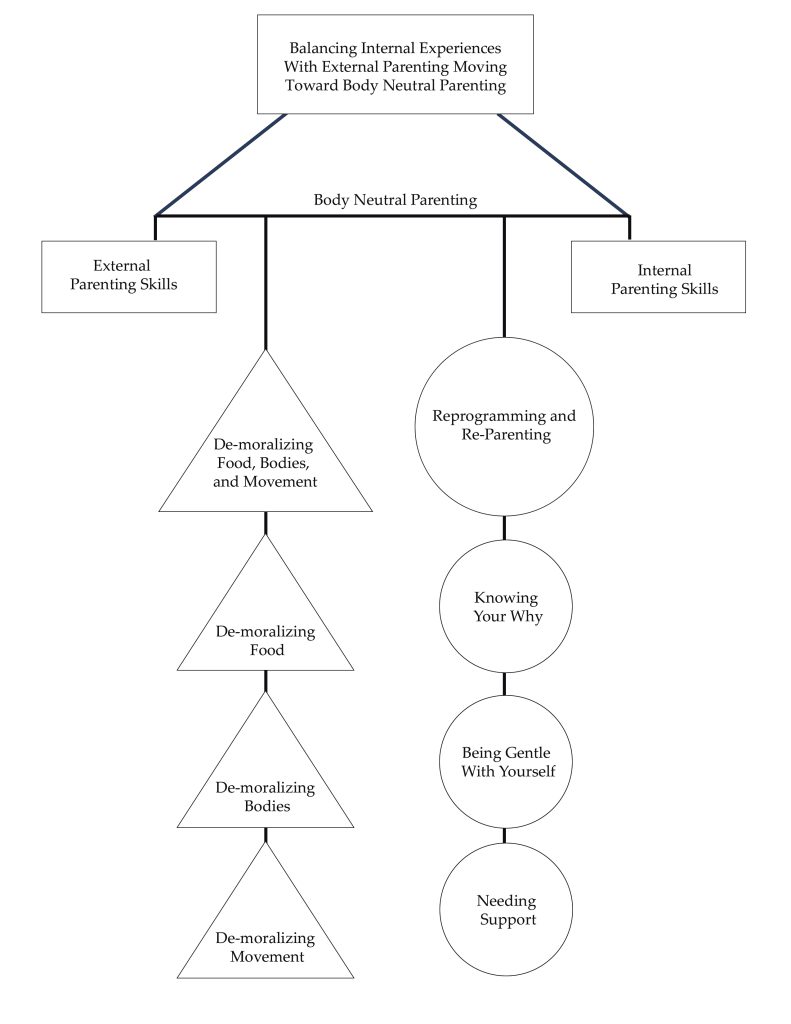

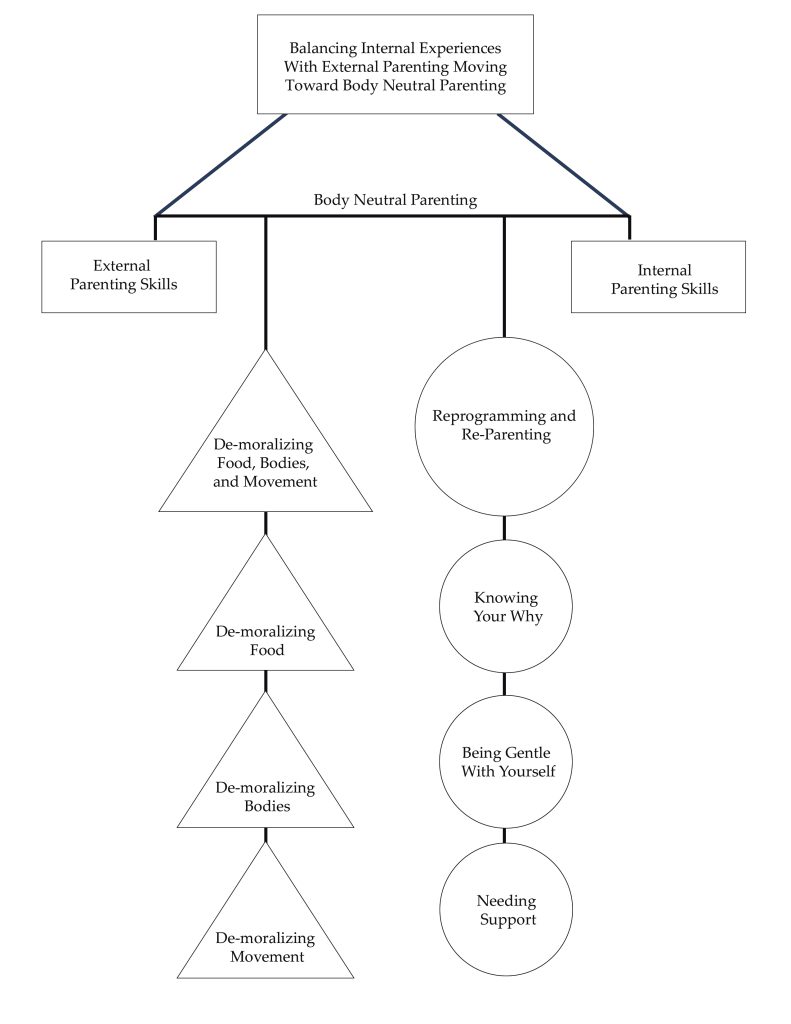

The emergent core category was the balancing of internal experiences with external parenting, moving toward body neutral parenting. The emergent core category captured the essence of the theory—parents integrating body neutrality balance internal experiences (e.g., their own relationship with their bodies and food) with external parenting (e.g., their parenting skills of how to handle food in the household). Figure 1 depicts a conceptual diagram of the body neutral parenting grounded theory. The “mobile” emphasizes the movement and interconnectedness within the body neutral parenting process. At the top of the diagram, there is a seesaw balance between the external parenting skills and internal experiences, processing, and regulating. The internal and external experiences teeter and totter and inform one another as a parent integrates body neutrality. The mobile diagram showcases that if one piece moves, the other pieces move as well. To illustrate, if a parent’s external parenting skills move (e.g., a parent no longer says negative things about their body in front of their children), their internal experiences are impacted (e.g., their own unmet childhood mental health needs related to body image are addressed). The core category of balancing internal experiences with external parenting moving toward body neutral parenting included two categories: (a) De-moralizing Food, Bodies, and Movement, and (b) Reprogramming and Re-Parenting. Each of the two emergent categories has associated subcategories.

De-moralizing Food, Bodies, and Movement

The first category is De-moralizing Food, Bodies, and Movement (n = 10). Within this category, there were three subcategories: De-moralizing Food, De-moralizing Bodies, and De-moralizing Movement. The category embodied acknowledging and countering the large cultural narrative of “good” foods and “bad” foods as well as “good” bodies and “bad” bodies. Participants emphasized the impact of removing the reward and punishment that accompanies the moralization of food, bodies, and movement. As captured by Kimberly, body neutral parenting is about “giving children more of a voice”and trusting them: “When they say that they’re hurt, believing them; when they say that they’re hungry, believing them. Letting them speak for themselves and not speaking for them or for their body. Trusting that they know their body the best.”

Figure 1

Note. This figure showcases the diagram of the body neutral parenting theory. The diagram shows a visual representation of the emergent core category, two categories, and six subcategories and their relationships (Charmaz, 2014).

De-moralizing Food

The first subcategory (n = 10) was De-moralizing Food. Participants consistently noted that food was “one of the biggest” parts of body neutral parenting—specifically, approaching food not as “good” or “bad,” not as “healthy” or “unhealthy,” but simply, neutrally, as “fuel” for the body. Cassie articulated that “A big piece is trying to take the moral piece out of it too. That it’s somehow good to have a certain body or foods are good or bad. Just trying to get away from that.”

The demoralization of food, moving toward neutrality with food, presented in numerous ways across participants’ approaches to caregiving. A primary way in which participants showcased their beliefs about food with regard to body neutrality was to present different foods in a neutral way. For example, the neutral presentation of different foods could look like desserts on the child’s plate from the beginning of the meal, rather than something to be “earned” after eating the “good” foods first. Esmeralda articulated a way in which she demoralized foods and presented them neutrally through what she coined as “Tasting Tuesdays.” She shared:

Instead of making a meal that you serve up in bowls or on plates, you basically charcuterie board the whole meal. . . . I noticed the effect it had on my kids to present a bunch of options, including desserts or traditional treats—it was all presented together. I was laying out all the foods on equal ground, lots of options. And many traditionally unhealthy foods and many traditionally healthy foods just all on the table together. There was no instruction. They just got an empty plate, and they could fill it with whatever they wanted, and I think for them there was some autonomy built into that. They could decide exactly what and how much they wanted to eat off the table. But it also, I think, inspired some adventurousness in them.

Presenting foods neutrally mitigated food judgment, created variety and exposures to food, and met the developmental needs of her children by making mealtime fun.

Another pivotal element of de-moralizing food and moving toward neutrality with food was to create space for children to practice noticing their hunger and fullness cues. Jennifer shared about her experience helping her child learn to trust their body and its cues. She explained:

Trying to trust him and listening to his body, even though he’s 2, and knowing where to intervene and where I shouldn’t intervene. If I make dinner and I put it in front of him and he touches nothing and wants to get down, the way that I was raised was you finish your plate no matter what. Reading everything that I’m reading and trying to move to this neutral space. What I want to say is “At least taste it. At least take a bite. Take one bite. Take three bites.” And what I’m choosing to do is, “Okay, you don’t have to eat right now. We’ll have a bedtime snack later.” I was conditioned to think that first thought.

While not explicitly using the language, participants spoke to helping their children with their hunger, fullness, and satiety cues. Practicing satiety looked like the children being able to say, as Scarlett’s son said, “My body is hungry for ice cream.” Also, Kimberly shared trying to instill autonomy within her children as they learn their hunger, fullness, and satiety cues:

We do defer to them a lot in terms of what they eat or when they’re eating. My daughter wanted canned cooked carrots for breakfast. It was like, well, okay, that’s not maybe socially typical, eating cooked carrots for breakfast. But if that’s what your body wants, go for it. . . . They asked her a question at school when she was graduating from preschool. What would you spend $1,000,000 on? A doughnut. So, it’s like, okay, we’re not going to demonize your doughnuts. You can have your doughnuts when you want your doughnuts.

Here, Kimberly also captured body neutral parenting’s emphasis on avoiding “healthy” vs. “unhealthy” food and other dichotomous language, stemming from diet culture.

Neutral beliefs and behaviors regarding food also manifest via portion sizes for children. Scarlett highlighted differences she noticed in how her family members wanted to portion food for her two sons: one in a larger body and one in a smaller body. She explained that her family members will “offer to my one son and not to the other” while also saying “Oh, do you need that?” to the son in a larger body. Thus, integrating body neutral parenting entails presenting food neutrally, rather than being driven by internalized societal messages about food and thin privilege (e.g., suggesting to a child in a larger body that they may not need the amount of food they are being served perhaps because of anti-fat bias). Body neutral parenting applies for children of all body types.

Moreover, caregivers practicing body neutrality with their children talked about food in a way that emphasizes how it “fuels the body” rather than being about “reward or punishment.” Esmeralda explained:

It’s like you have to basically find a whole new system of rewards. Sweet things are good motivators. They’re reward systems. And they’re also seen as the desirable food after you choke down the “healthy” food . . . these are the “good” foods you have to eat in order to get the “bad” foods that you get rewarded with after dinner. That just is such an insidious concept.

Counter to food being a “reward” or “punishment,” children get to choose rather than falling into the power struggle with food. Cassie described

taking the power out of the food situation. With little kids, everyone thinks like, “Oh, you have to control it and you have to make sure they get vegetables in and all that stuff.” Then it becomes about this power dynamic and just trying to take power out of it and then it is about letting them listen to their body and learn about their body.

Avoiding using food as a reward or as a punishment was integral to the body neutral parenting approach.

De-moralizing Bodies