Publication Trends of Addiction Counseling: A Content Analysis of the Rate and Frequency of Addiction-Focused Articles in Counseling Journals

Natalie M. Ricciutti, Willough Davis

Substance use disorders (SUDs) and addictions are prevalent client issues that counselors are likely to encounter. Yet, researchers have previously found that counseling journals publish articles about addiction issues at lower rates when compared to other topics. The purpose of this study was to determine recent publication rates of addiction-focused articles in 24 counseling journals between 2016 and 2023. We determined that only 174 (4%) of 4,356 articles published in counseling journals explored addictions-related issues. We conducted a multiple regression analysis and found that the publishing journal had a significant predictive relationship with the publication of addiction-focused articles, while publication year did not. We provide implications for counselors, researchers, reviewers, and journal editors to advocate for the publication of addiction-focused literature for the benefit of the counseling profession.

Keywords: substance use disorders, addictions, counseling journals, publication rates, addiction-focused articles

Addiction treatment is an important and necessary service to both individuals and communities. The 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health published by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA; 2024) estimated that 48.7 million people have a substance use disorder (SUD). The same survey also found that approximately 21.5 million adults in the United States have co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders. These figures indicate that SUDs and addictions are prevalent issues that counseling professionals are likely to treat. Accordingly, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2024) estimated that the job outlook for substance abuse, behavioral disorder, and mental health counselors is expected to grow by 18% by 2032. This rate of growth is notably faster than the average career growth rate of 5% for those counseling fields. For this reason, it is important that counselors have access to resources that help them learn about addiction issues and treatment in order to better serve their clients. Research articles are one type of resource counselors and counselors-in-training use regularly (Golubovic et al., 2021; Lee, 2014).

Despite the value placed on published counseling literature (Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2024; Golubovic et al., 2021), counselors have reported difficulty finding articles written about evidence-based addiction treatment practices and research (Doumas et al., 2019; McCuistian et al., 2023; Ricciutti & Storlie, 2024; Sperandio et al., 2023). Previous researchers also found that addiction-focused articles make up a small percentage of the overall counseling literature (Moro et al., 2016; Wahesh et al., 2017). The potential lack of addiction literature in counseling journals may contribute to professionals being uninformed about evidence-based practices and techniques (Golubovic et al., 2021; Lee, 2014). The purpose of this study was to conduct a conceptual content analysis to determine: (a) the rate and frequency of addiction-focused articles that were published in counseling journals from 2016 to 2023, (b) the journals that published the most addiction-focused articles, (c) the most common type of articles published (quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, conceptual, etc.), and (d) if publishing journal and year of publication predicted the frequency of published addiction-focused articles.

Addiction Issues in Counseling Specialty Areas

SUDs, addictions, and addiction-related issues are prevalent across a variety of populations and age groups and can be common co-occurring disorders (SAMHSA, 2021, 2024). Addictions are also considered to be a continuously growing public health crisis (Matsuzaka & Knapp, 2020; SAMHSA, 2014; Wing Lo et al., 2020). Given the scope and magnitude of addiction prevalence, counselors are likely to work with individuals with an SUD or addiction in treatment, academic, and clinical settings (Chetty et al., 2023). It is vital that counselors across all counseling specialties are informed about addiction-related issues.

One specialty area in which knowledge about SUD and addiction treatment is of the utmost importance is college counseling. According to the American College Health Association (2023), 65.9% of students reported alcohol use and 30.4% reported cannabis use in the previous 3 months. Additionally, 12.8% of the students who reported alcohol use demonstrated moderate or high risk; 20.5% of the students who reported cannabis use demonstrated moderate or high risk. Researchers have found that use of other substances such as opiates (Schulenberg et al., 2019), unprescribed medication (Sharif et al., 2021), and vaping products (National Institutes of Health, 2020) have all recently increased among college students. College students are also susceptible to developing internet addiction (Krishnamurthy & Chetapalli, 2015; Pu et al., 2023) and sex addiction (Giordano & Cashwell, 2018; Giordano et al., 2017), which are categorized as behavioral addictions (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Counseling services have been found to have a positive impact on college student substance use (Pu et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2020). However, students enrolled in counseling programs are not required to complete addiction counseling courses (CACREP, 2024). Some college counselors have reported that they lack the addiction counseling training and competence needed to work with students with an SUD or addiction (DePue & Hagedorn, 2015; Giordano & Cashwell, 2018). The prevalence of substance use and addiction issues in university settings suggests that college counselors may benefit from evidence-based addiction counseling literature.

Career counseling is another specialty area in which professionals may work with individuals experiencing SUDs and addictions. Addiction can impact an individual’s occupational wellness as well as their ability to secure and maintain employment (Allen & Bradley, 2015; Siu et al., 2019). Sherba et al. (2018) found that individuals with addictions experienced difficulty finding and sustaining employment. Researchers also identified that employment issues increased relapse rates for individuals in recovery (Sánchez-Hervás et al., 2012). Conversely, individuals with an SUD or addiction who received career counseling services experienced an increase in career maturity and career self-efficacy (Allen & Bradley, 2015) and a decreased risk of relapse (Kim et al., 2022). Yet, similar to college counselors, future career counselors are not required to take an addiction counseling course (CACREP, 2024). Graham (2006) found that this lack of education may cause career counselors to engage in treatment with biases that may negatively impact the therapeutic alliance. Therefore, career counselors need access to addiction counseling information, as it can be a beneficial aspect of an effective and well-rounded treatment plan and potentially decrease counselors’ biases.

Clinical mental health counselors (CMHCs) may often work with individuals with addictions. It is estimated that 7.7 million American adults have both a diagnosable mental health disorder and an SUD or addiction (Han et al., 2017; SAMHSA, 2024). Common comorbidities include mood and anxiety disorders (Kingston et al., 2017), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Harstad et al., 2014), personality disorders (Medeiros & Grant, 2018; Pennay et al., 2011), and schizophrenia (Menne & Chesworth, 2020). For this reason, CMHCs are likely to work with individuals with addictions who initially seek treatment for a mental health disorder. Han et al. (2017) also found that individuals with comorbid mental health disorders and SUDs may seek out different treatment providers for each diagnosable issue. For example, clients may work with a CMHC for a mood disorder and an addiction counselor for an SUD. This dual treatment approach can be problematic because the providers may be unaware of the individual’s co-occurring disorders, and they may provide contradicting information and treatment (Han et al., 2017). Further, comorbid diagnoses have been found to be more effectively treated when one counselor uses integrated therapeutic modalities for both mental health and SUDs (Chetty et al., 2023). Thus, CMHCs must have access to research and information about SUDs and addiction issues to effectively treat individuals with comorbid disorders.

Like other specialties, marriage or couples and family counseling can be impacted by addiction-related issues. Addiction can lead to decreased trust between married or coupled partners (Molla et al., 2018) and an increased risk of marital dissolution and divorce (Torvik et al., 2013). In family systems, researchers found that having a child with an addiction was associated with lower family quality of life and lower marital satisfaction (Hamza et al., 2021). Children are more likely to experience attachment issues and mental health concerns if one or both parents have an addiction (Patton et al., 2019). Marriage or couples and family counselors must be aware of the impact SUD and addiction issues can have on their clients, as well as effective, evidence-based practices in order to support the development of healthy couple and family functioning.

School counselors also face SUD and addiction-related issues among their students and can work in the areas of intervention and prevention. Substance use at an early age may increase the risk of developing an addiction later in life (Nelson et al., 2015). According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2024), 29.8% of high school students reported current alcohol use, 13.2% reported current electric vape use, and 19.8% reported current marijuana use. Some students may also be at risk of developing behavioral addictions, such as internet gaming disorder (Chibbaro et al., 2019; Sylvestro et al., 2023). Similar to marriage or couples and family counselors, school counselors may also work with students whose parents have an addiction (Bröning et al., 2012). These children are at a higher risk of experiencing mental health issues (Patton et al., 2019), experimenting with substances, and developing an addiction themselves (Järvinen, 2015; Leijdesdorff et al., 2017). School counselors play a vital role in the early intervention of substance use and the prevention of addictions because of their position as school-based helping professionals (Bröning et al., 2012). Consequently, school counselors, and all counseling professionals, must have access to accurate, peer-reviewed, evidence-based literature about general addiction issues and specific topics relevant to their specialty.

Addiction-Focused Research and Publications

Despite evidence that substance use and addiction issues are common in every area of counseling (Allen & Bradley, 2015; Han et al., 2017; Pu et al., 2023), previous researchers have found that these issues are not reflected in published research (Moro et al., 2016; Wahesh et al., 2017). In 2017, Wahesh et al. reviewed articles published in 23 counseling journals from 2005 to 2014 and found that 4.5% (210 out of 4,640) were focused on addiction-related topics. They also found that an average of 23.33 addiction-focused articles were published each year from 2005 to 2014. Wahesh et al. highlighted that many journals had the capacity to publish more addiction-focused articles but did not. For example, the Journal of Specialists in Group Work published a total of 209 articles between 2005 and 2014. Only five of those articles were focused on addictions or addiction-related issues. The researchers also analyzed changes in publication trends by year and determined that, of the 210 articles focused on addiction-related topics, most were published in 2011 (n = 30) and 2012 (n = 30), while the fewest articles were published in 2008 (n = 14) and 2009 (n = 17). Wahesh et al. concluded that their results may stem from journals rejecting addiction-focused articles and/or addiction counseling researchers submitting their work to journals in other professions (e.g., psychology, social work, public health).

Moro et al. (2016) found similar results when they explored the prevalence of addiction-related articles in four counseling journals published between 2007 and 2011. They found that the Journal of Counseling and Development (JCD) published three (5.1%) addiction-related articles, Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development (MECD) published two (12.9%) articles, Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation published four (19%) articles, and Counselor Education and Supervision (CES) did not publish any addiction-related articles. Moro et al. also analyzed the frequency of addiction counseling topics presented at the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision conferences during that time frame. Thirty-six out of 1,966 (1.8%) conference presentations discussed addictions, addiction counseling, or addiction counseling education. These results are particularly concerning because many practicing counselors obtain continuing education through reading articles and attending conferences. Counselors may not have other avenues for learning about addiction-related research and evidence-based treatment if the information is not disseminated to the profession via published literature or conference presentations (Moro et al., 2016).

This lack of published literature and conference presentations has led counselors to advocate for more information about addictions and addiction-related issues. Both Moro et al. (2016) and Wahesh et al. (2017) stressed the importance of publishing more addiction-focused articles in counseling journals. Wahesh et al. specifically advocated for research that focuses on how addictions impact diverse groups, subcommunities, and evidence-based practices. Regarding diverse groups, Chaney (2019) explored the degree to which LGBTQ+ populations were included in articles published in the Journal of Addiction and Offender Counseling (JAOC). Chaney found that five (1.78%) out of the 281 articles published since the inauguration of the journal in 1980 to 2018 were focused on LGBTQ+ individuals. Behavioral addictions are another type of addiction that counselors have reported treating (Király et al., 2020; Oka et al., 2021; Ricciutti & Storlie, 2024), yet there is a dearth of published research (Giordano, 2019; Ricciutti, 2023; Wilson & Johnson, 2013). Ricciutti & Storlie (2024) interviewed practicing counselors about their experiences working with clients with process addictions, and all of the participants indicated that they had trouble finding relevant evidence-based practices and techniques in counseling literature. Carlisle et al. (2016) called for more research about the treatment of internet gaming disorder by counselors. Chaney and Burns-Wortham (2014) advocated for more research about sex addiction among the LGBTQ+ community.

Published research is a necessity for the counseling and counselor education professions (Giordano et al., 2021; Golubovic et al., 2021; Lee, 2014). Advancement in counseling practices cannot occur without the constant publication of exemplary research. Some counseling subtopics have seen a surge in published research within the previous decade (i.e., diversity and multicultural issues). Addiction counselors, researchers, and educators have repeatedly called for more addiction counseling information to be published in counseling journals (Golubovic et al., 2021; Moro et al., 2016; Ricciutti & Storlie, 2024; Wahesh et al., 2017). At this time it is unclear if these calls have been answered and if changes have been made. If they have not, it may reflect the lack of addiction-related content being published in counseling journals.

The purpose of this research study was to update the research done by Wahesh et al. (2017) and to determine: (a) the rate and prevalence of addiction articles that have been published in counseling journals between 2016 and 2023, (b) which journals published the most addiction-focused articles, (c) the type of addiction-focused articles (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods) published, and (d) if the publishing journal and year of publication predicted the frequency of published addiction-focused articles. We hope that this research will highlight any changes that counseling journals have made to publish more information about addictions and addiction counseling since

the Wahesh et al. review was published in 2017.

Research Questions

Four research questions guided this study:

RQ1: What was the rate and percentage of addiction-focused articles that were published in counseling journals between 2016 and 2023?

RQ2: Which journals published the most addiction-focused articles?

RQ3: What type of article was most commonly published (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, content analysis, literature review)?

RQ4: Did the publishing journal and the year of publication predict the frequency of published addiction-focused articles?

Methodology

We used journal websites and the library resources at the university where the study took place to answer the research questions. We followed Delve et al. (2023) and Hsieh and Shannon’s (2005) recommended guidelines for conducting a conceptual content analysis research study. These guidelines supported our choice to: (a) focus on the concept of addiction-focused counseling research, (b) identify specific words presented in text form (e.g., “addiction,” “substance use,” “addiction counseling”), (c) follow a combined deductive and inductive coding process by categorizing segments of the text that represent the focused concept, (d) take steps to address potential coder disagreements, and (e) use appropriate subjective interpretation based on our expertise.

Our research team included one professor, Natalie M. Ricciutti, and one doctoral-level graduate student, Willough Davis. Ricciutti has a degree in counselor education and supervision, with specializations in addiction counseling and addiction education, and extensive experience conducting content analysis research. At the time of the study, Davis was enrolled in a counselor education and supervision program and has a strong clinical background in addiction counseling. Davis also assisted in the study to fulfill requirements of an independent study about content analyses. We are both White females who have previously completed multiple courses in research methods. Ricciutti determined the purpose of the study, outlined the coding process, and trained Davis to identify and include relevant data prior to and throughout the study. Davis completed the initial review and categorization of the addiction counseling literature and Ricciutti provided feedback weekly.

Journal Search and Data Collection

In an attempt to update Wahesh et al.’s (2017) study with fidelity, the data collection and review processes in the current study remained the same, with a few exceptions. First, we chose a timeline of 8 inclusive years instead of 9 because 8 years had passed since Wahesh et al. ended their data collection in 2015. Second, we selected the same 23 counseling journals for our study and added the Journal of School Counseling, bringing our journal total to 24. We organized the 24 journals into a list for data collection purposes (Table 1). This list included national journals (n = 19, 79.2%), regional journals (n = 3, 12.5%), and international journals (n = 2, 8.3%). National journals included JCD, CES, JAOC, and the Professional School Counselor; regional journals included Counselor Preparation and Supervision and Teaching & Supervision in Counseling; and international journals included the International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling and the Asia Pacific Journal of Counseling & Psychotherapy. We conducted a thorough review of all the articles published in the 24 journals, which resulted in a total of 4,356 articles.

We reviewed the title, abstract, keywords, and full narrative of each of the 4,356 articles to determine whether or not each was about addiction or substance use–related issues. We labeled articles as addiction-focused if they used addiction-related terminology in the title, abstract, keywords, and/or full narrative. Common terminology included specific types of substance or behavioral addictions, addiction recovery, addiction treatment, and addiction counseling. We also included articles if they focused on addictions or addiction-related topics. Common topics included evidence-based addiction treatment practices, issues related to specific SUDs and behavioral addictions, risk and protective factors of addictions, the impact of addiction and/or substance use among specific populations, and addiction counseling education.

We collected data by categorizing each addiction-focused article’s relevant information in an Excel spreadsheet. This included the article title, the publishing journal, year of publication, the article’s keywords, type of article (e.g., original research, conceptual, literature review), and the type of research the article included (if relevant; quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods). Similar to the inclusion process, we excluded articles if they did not have an addiction-related focus, and they did not include addiction-related terminology in the title, abstract, keywords, and full narrative. Ricciutti reviewed Davis’s categorization of articles and data coding during weekly meetings to ensure coder agreement. We both reviewed articles when it was unclear if an article was focused on addiction-related content. When necessary, we discussed an article’s focus until we resolved disagreements and reached consensus on inclusion or exclusion. Lastly, we cross-referenced our collected data with the 4,356 articles to ensure that we included all of the published addiction-focused articles. We determined that no articles needed to be added or removed. The data was transferred into SPSS (Version 28) for analysis.

Data Analysis

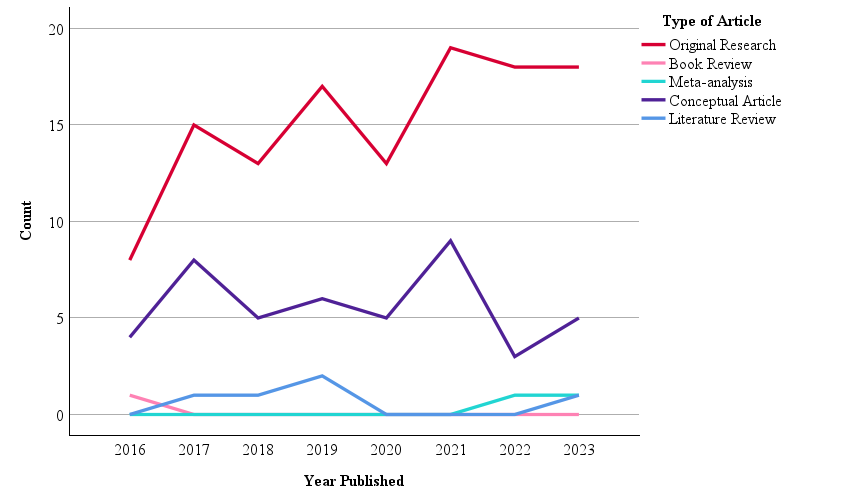

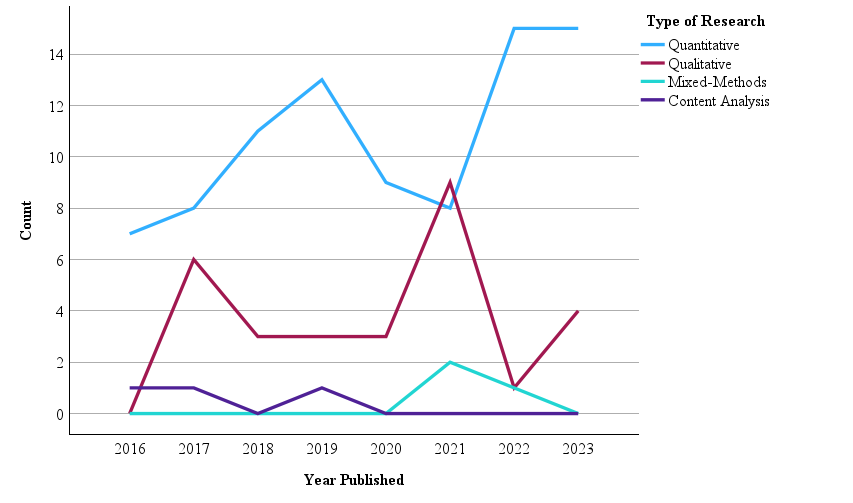

We used descriptive statistics to answer the first research question and to determine the rate and percentage of all addiction-focused articles published in counseling journals between 2016 and 2023. For the second research question, we used descriptive statistics to determine the rate and percentage of the addiction-focused articles published in each journal. For the third research question, we used descriptive statistics to determine the rate and percentage of the type of articles and the research methodology researchers used. We also used descriptive statistics to determine the number of the type of article and type of methodology published each year (Figures 1 and 2). We conducted a multiple regression analysis to answer the final research question to determine the predictive relationship between the independent variables of publishing journal and year of publication as well as the dependent variable of frequency of published addiction-focused articles.

Table 1

Addiction-Focused Article Trends per Journal

| Journal | Total Number of Articles | Number of Addiction-Focused Articles | Percentage of Addiction-Focused Articles |

| Adultspan Journal | 62 | 0 | 0% |

| Asia Pacific Journal of Counseling and Psychotherapy | 96 | 0 | 0% |

| Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation | 79 | 4 | 5.0% |

| Counseling and Values | 107 | 2 | 1.87% |

| Counselor Education and Supervision | 178 | 1 | 0.56% |

| The Family Journal | 448 | 20 | 4.46% |

| International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling | 281 | 7 | 4.49% |

| The Journal for Specialists in Group Work | 141 | 2 | 1.42% |

| Journal of Addiction & Offender Counseling | 67 | 51 | 74.63% |

| Journal of College Counseling | 118 | 15 | 13.56% |

| Journal of Counseling & Development | 324 | 14 | 4.32% |

| Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision | 305 | 4 | 1.31% |

| Journal of Creativity in Mental Health | 316 | 12 | 4.11% |

| Journal of Employment Counseling | 114 | 1 | 0.89% |

| Journal of Humanistic Counseling | 117 | 3 | 2.56% |

| Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling | 155 | 4 | 2.58% |

| Journal of Mental Health Counseling | 182 | 6 | 3.29% |

| Journal of Multicultural Counseling & Development | 148 | 2 | 1.35% |

| Journal of School Counseling | 172 | 3 | 1.74% |

| Journal of Technology in CE&S | 49 | 0 | 0% |

| Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development | 167 | 6 | 3.59% |

| The Professional Counselor | 227 | 11 | 4.85% |

| Professional School Counselor | 408 | 2 | 0.98% |

| Teaching and Supervision in Counseling | 95 | 2 | 2.11% |

Note. Total number of articles is 4,356. Number of addiction-focused articles is 174.

Figure 1

Type of Addiction-Focused Articles Published per Year

Note. N = 174.

Note. N = 174.

Figure 2

Type of Research in Published Addiction-Focused Articles per Year

Note. N = 121.

Results

Of the 4,356 articles published in 24 counseling journals from 2016 to 2023, we identified 174 (4%) as focused on addiction counseling or other addiction-related issues (Table 1). Regarding our second research question, JAOC had the highest rate and percentage of addiction-focused articles at 74.63% (n = 51). Adultspan Journal, Asia Pacific Journal of Counseling & Psychotherapy, and Technology in CES were tied with the lowest percentage of addiction-focused articles at 0%. Regarding the third research question, the most common type of article was original research (n = 121, 69.5%). Other types of articles included conceptual pieces (n = 45, 25.9%), literature reviews (n = 5, 2.9%), meta-analyses (n = 2, 1.1%), and book reviews (n = 1, 0.6%). Figure 1 provides a description of the type of addiction-focused articles published during each year. Of the 121 original research articles, 86 (71.1%) were quantitative studies, 29 (24%) were qualitative studies, three (2.5%) were content analyses, and three (2.5%) were mixed method studies. Figure 2 provides a description of the type of research conducted in each addiction-focused published article during each year.

Regarding the fourth research question, we first calculated yearly analyses to determine the number of addiction-focused articles published in counseling journals each year (Table 2). The year 2016 had the lowest number of published addiction-focused articles (n = 13, 7.5%), while 2021 had the highest (n = 28, 16.1%). On average, 21.75 addiction-focused articles were published each year from 2016 to 2023. Next, we conducted a multiple linear regression analysis to determine if journal and year of publication had a predictive relationship with the frequency of published addiction-focused articles. This analysis resulted in a statistically significant regression model, F(2, 187) = 4.134, p = .018, R2 = 0.42. Finally, we examined the individual predictors (i.e., independent variables). We found that publishing journal had a significant predictive relationship with the frequency of published addiction-focused articles, (Beta = −.192, t(189) = −3.682, p = .008). In other words, some journals were significant predictors of being more likely to publish addiction-focused articles than others. We also found that publication year did not have a significant predictive relationship with the frequency of published addiction-focused articles (Beta = .07, t(189) = .973, p = .332).

Table 2

Addictions-Focused Articles Published Per Year

| Year | n | % |

| 2016 | 13 | 7.5 |

| 2017 | 24 | 13.8 |

| 2018 | 19 | 10.9 |

| 2019 | 25 | 14.4 |

| 2020 | 18 | 10.3 |

| 2021 | 28 | 16.1 |

| 2022 | 22 | 12.6 |

| 2023 | 25 | 14.4 |

Note. Total N = 174.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the frequency of addiction-focused articles published in counseling journals in recent years. We reviewed 4,356 articles published in 24 counseling journals from 2016 to 2023 to determine the frequency and percentage of addiction-focused literature in the counseling profession. The results indicate only 174 (4%) of those articles were focused on addiction counseling or other addiction-related issues. This percentage is less than previously identified by Wahesh et al. (2017), who found that 210 (4.5%) out of 4,640 articles published from 2005 to 2014 were about addiction issues. Publication year also did not have a significant, predictive relationship with publication rates. This result suggests that national and global events occurring between 2016 and 2023 (e.g., the opioid epidemic, the COVID-19 pandemic) did not statistically impact the publication of addiction-focused articles in counseling journals.

We also determined that the majority of addiction-focused articles were original research, many of which used quantitative analytic techniques. This result reflects a long-standing trend toward quantitative methodologies in the counseling and other helping professions (Berríos & Lucca, 2006; Marshall et al., 2025; Oh et al., 2017). We also found that only three of the 174 addiction-focused articles used mixed methods techniques. This number is lower than Wahesh et al.’s (2017) finding of six mixed methods studies. Researchers and professionals in counseling have called for more mixed methods research to achieve well-rounded study findings (Ponterotto et al., 2013; Wester & McKibben, 2019). Our results indicate that this change has yet to occur with addiction-focused research published in counseling journals.

It is worth noting the differences we found in publication rates by journal when considering potential reasons for the lack of addiction-focused counseling literature. The specific journal and the publication of addiction-focused articles had a significant, predictive relationship. Unsurprisingly, JAOC published the most addiction-related literature in both number and percentage. Yet, it had one of the lowest numbers of total published articles (67 from 2016 to 2023; Table 1). As discussed, counselors have reported experiencing difficulty finding relevant, evidence-based addiction counseling literature to support their practice (Chaney, 2019; Ricciutti & Storlie, 2024; Wilson & Johnson, 2013). This struggle may be because the only addiction counseling journal has one of the lowest publication rates out of the 24 journals included in this study.

Another reason for the publication rate may be a lack of addiction-focused articles being submitted to counseling journals. Instead, counseling researchers with expertise in addiction issues may be submitting their manuscripts to journals in other professions (e.g., psychology, social work, public health, etc.). We did not find a study exploring the rates of addiction-focused articles in the psychology, social work, or public health professions to compare with our findings. Yet, these professions each have many addiction and substance use–focused journals where researchers can choose to submit their work. A Google Scholar (2024) search of all addiction journals’ h5-indices (i.e., the number of articles published in the last 5 years) and h5-medians (i.e., the median number of citations for articles in the h5-index) shows that the top 20 publications at the time of this writing are the psychology journals the International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, and Addictive Behaviors. JAOC was not included in that list.

The results may also be due to the small number of counseling researchers and educators with expertise in addiction issues compared to the overall profession. A number of studies have found that many counseling students leave their programs without the necessary academic experience to competently practice addiction counseling (Golubovic et al., 2021; Lee, 2014; Ricciutti & Storlie, 2024). As discussed, CACREP (2024) standards do not include addiction counseling content requirements for many of the specialty practice areas. Ricciutti & Storlie (2024) found that the lack of education caused some counselors to report that addiction counseling was not part of their professional identity. For this reason, we join Moro et al. (2016) in advocating for the inclusion of an addictions course into the counseling core curriculum. Requiring a course for all students may help future counselors incorporate addiction counseling into their professional identity. Doing so could instill future counselors with a passion for addiction issues and eventually lead to an increase in addiction-focused manuscripts submitted for publication in counseling journals.

Recommendations for Counselors, Counselor Educators, and Researchers

Addiction-focused literature published in counseling journals is highly relevant for practicing counselors, counseling researchers, and the overall profession. Substantial value is placed on published research to advance the counseling profession (CACREP, 2024; Golubovic et al., 2021). SUD and addictions are common primary and co-occurring disorders (SAMHSA, 2021, 2024) and the job outlook for addiction and substance use counselors is expected to grow rapidly (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2024). Counselors in every specialty area need relevant, evidence-based research about SUD and addiction issues to inform their practice. Yet, we found the publication of addiction-focused articles to be low, with some journals failing to publish anything about addiction issues from 2016 to 2023. Journals may want to consider how to solicit addiction-focused content for publication to fill this research gap.

The existing prevalence rates of addiction-focused articles may, in part, stem from researchers not submitting articles about addiction issues to counseling journals. Researchers may believe that their manuscript is likely to be rejected if it is sent to a journal that has not published an addiction-related article in recent years. We encourage authors and researchers to push against this potential belief and consider submitting their addiction-focused manuscripts to journals that have not recently published articles about the topic. This practice could inform editors and reviewers about addiction-related issues in the counseling profession, as well as help authors reach new audiences who may not normally read addiction-focused articles. Counselors and researchers also can attempt to advocate for the inclusion of addiction-focused articles in the journals they frequently read. This advocacy can come in the form of writing letters to journal editors to request more addiction content. Practicing counselors can also work to conduct addiction-focused research studies through their agencies, practices, schools, or universities. The information gleaned from studies that are conducted in novel settings with diverse populations would be highly relevant to the profession and help grow the existing body of literature.

An increase in addiction-focused research studies and submitted manuscripts is only the first step toward a higher prevalence of published articles. Journal review boards and editors must be willing to expand the aims, scope, and acceptable topics to include addiction-related issues. For example, addiction issues are highly relevant in every counseling specialty area, including school counseling (Bröning et al., 2012). Yet, the Professional School Counselor published two addiction-focused articles and the Journal of School Counseling only published three (Table 1). This is despite recent evidence that substance use and addiction issues continue to be a common issue among children and adolescents in the last decade (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2023). Editors and reviewers expanding journals’ scope and acceptable topics for consideration may allow researchers with an expertise in addiction counseling to feel more confident sending their manuscripts to counseling journals other than JAOC.

Journals can sponsor special issues that are dedicated to addiction-related topics. We urge researchers, writers, journal editors, and reviewers to consider the long-term implications and benefits of providing more addiction-focused articles to the entire counseling profession. These journal practices will help grow the existing literature over time; expand addiction-related topics to a variety of co-occurring disorders and populations; and provide new opportunities for continuing education, much of which can be obtained through reading and contributing to journal articles. For example, Chaney (2019) called for more literature about substance use and addiction among the LGBTQ+ community. The Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling could combine both topics in a special issue. Finally, we encourage CACREP to consider adding new addiction counseling standards to their next edition at both the master’s and doctoral levels. As discussed, counselors in every specialty area are likely to work with individuals with addictions and SUDs (Bröning et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2022; Patton et al., 2019). Yet, many have reported their training and skills in this area have fallen short of competence (DePue & Hagedorn, 2015; Giordano & Cashwell, 2018; Han et al., 2017). It is necessary that all counselors receive education in addiction counseling in order to better serve their clients or students.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, as with any conceptual content analysis, researcher error and subjective interpretation of the data is a potential limitation. Although we fully reviewed each of the 4,640 articles, we identified addiction-focused articles, in part, through the inclusion of addiction terminology in the title, abstract, keywords, and narrative. It is possible we unintentionally excluded relevant articles or included articles that were irrelevant because we did not use statistical measures of interrater reliability. Similarly, it is possible there was addiction-related language and terminology that we were unfamiliar with, causing us to exclude articles that should have been included. We also may have allowed our unconscious biases to impact our data inclusion process throughout the study. We worked to mitigate this potential limitation by reviewing each article in full and by following recommended guidelines for conducting a conceptual content analysis (Delve et al., 2023; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Second, this study focuses on addiction articles published in 24 counseling journals from 2016 to 2023. For this reason, it is possible that our study may not accurately reflect published addiction-focused articles over a broader period of time or with different journals. We encourage future researchers to review additional counseling journals not included in this study, such as state counseling journals or local university counseling journals. Third, we only collected and analyzed data that was publicly available—published articles in counseling journals. We did not gather data on the number of addiction-focused manuscripts that were submitted to journals but not published. Future researchers may consider contacting counseling journal editors to ascertain the rate of submitted manuscripts that were not published for any reason (e.g., rejected, author pulled their manuscript). Researchers can then compare the number of submitted addiction manuscripts with the number of published articles. Doing so may incorporate data excluded from this study and determine if the small number of addiction-focused articles is due to lack of quality submissions or potential reviewer and editor bias. Researchers could also conduct a similar study with journals in other helping professions (e.g., psychology, social work, public health) to determine if our results reflect a common trend in the publication of addiction-focused articles.

Conclusion

We explored the prevalence of addiction-focused articles published in 24 counseling journals from 2016 to 2023 and found recent publication rates to be low. We reported the journals that have published addiction-focused articles during that time frame, the type of articles published, and the potential impact of journal and year of publication. We compared our findings with Wahesh et al. (2017) and determined that the prevalence and rate of addiction articles has not increased since 2005. The lack of information may make it difficult for counselors in every specialty area to learn about addiction issues relevant to their clients or students. Finally, we provided information about the importance of addiction literature in the counseling profession and the implications of journals expanding their aims and scopes to include addiction issues.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Allen, K. R., & Bradley, L. (2015). Career counseling with juvenile offenders: Effects on self-efficacy and career maturity. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 36(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1874.2015.00033.x

American College Health Association. (2023). National College Health Assessment: Spring 2022 reference group executive summary. https://www.acha.org/ncha/data-results

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Berríos, R., & Lucca, N. (2006). Qualitative methodology in counseling research: Recent contributions and challenges for a new century. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84(2), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb00393.x

Bröning, S., Kumpfer, K., Kruse, K., Sack, P.-M., Schaunig-Busch, I., Ruths, S., Moesgen, D., Pflug, E., Klein, M., & Thomasius, R. (2012). Selective prevention programs for children from substance-affected families: A comprehensive systematic review. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 7(23), 1–17. http://www.substanceabusepolicy.com/content/7/1/23

Carlisle, K. L., Carlisle, R. M., Polychronopoulos, G. B., Goodman-Scott, E., & Kirk-Jenkins, A. (2016). Exploring internet addiction as a process addiction. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 38(2), 170–182. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.38.2.07

Chaney, M. P. (2019). LGBTQ+ addiction research: An analysis of the Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 40(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaoc.12053

Chaney, M. P., & Burns-Wortham, C. M. (2014). The relationship between online sexual compulsivity, dissociation, and past child abuse among men who have sex with men. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 8(2), 146–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2014.895663

Chetty, A., Guse, T., & Malema, M. (2023). Integrated vs non-integrated treatment outcomes in dual diagnosis disorders: A systematic review. Health SA Gesondheid, 28(1), a2094. https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v28i0.2094

Chibbaro, J. S., Ricks, L., & Lanier, B. (2019). Digital awareness: A model for school counselors. Journal of School Counseling, 17(22). https://jsc.montana.edu/articles/v17n22.pdf

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2024). 2024 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2024-Standards-Combined-Version-4.11.2024.pdf

Delve, Ho, L., & Limpaecher, A. (2023, January 25). What is conceptual content analysis in qualitative research? Step-by-step guide. https://delvetool.com/blog/what-is-conceptual-qualitative-content-analysis-step-by-step-guide

DePue, M. K., & Hagedorn, W. B. (2015). Facilitating college students’ recovery through the use of collegiate recovery programs. Journal of College Counseling, 18(1), 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2015.00069.x

Doumas, D. M., Miller, R. M., & Esp, S. (2019). Continuing education in motivational interviewing for addiction counselors: Reducing the research-to-practice gap. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 40(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaoc.12055

Giordano, A. L., & Cashwell, C. S. (2018). An examination of college counselors’ work with student sex addiction: Training, screening, and referrals. Journal of College Counseling, 21(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocc.12086

Giordano, A. L., Cashwell, C. S., Lankford, C., King, K., & Henson, R. K. (2017). Collegiate sexual addiction: Exploring religious coping and attachment. Journal of Counseling & Development, 95(2), 135–144. http://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12126

Giordano, A. L., Malacara, A., & Agarwal, S. (2019). A process addictions course for counselor training programs. Teaching and Supervision in Counseling, 1(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.7290/tcs010105

Giordano, A. L., Schmit, M. K., & Schmit, E. L. (2021). Best practice guidelines for publishing rigorous research in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(2), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12360

Golubovic, N., Dew, B., Rumsey, A., Murphy, T., Dispenza, F., Tabet, S., & Lebensohn-Chialvo, F. (2021). Pedagogical practices for teaching addiction counseling courses in CACREP-accredited programs. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 42(1), 3–18. http://doi.org/10.1002/jaoc.12086

Google Scholar. (2024). Addiction – Google Scholar Metrics. https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=top_venues&hl=en&vq=med_addiction

Graham, M. D. (2006). Addiction, the addict, and career: Considerations for the employment counselor. Journal of Employment Counseling, 43(4), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2006.tb00016.x

Hamza, E. G. A., Gladding, S., & Moustafa, A. A. (2021). The impact of adolescent substance abuse on family quality of life, marital satisfaction, and mental health in Qatar. The Family Journal, 30(1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807211000720

Han, B., Compton, W. M., Blanco, C., & Colpe, L. J. (2017). Prevalence, treatment, and unmet treatment needs of US adults with mental health and substance use disorders. Health Affairs, 36(10), 1739–1747. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0584

Harstad, E., Levy, S., & Committee on Substance Abuse. (2014). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse. Pediatrics, 134(1), e293–e301. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0992

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Järvinen, M. (2015). Understanding addiction: Adult children of alcoholics describing their parents’ drinking problems. Journal of Family Issues, 36(6), 805–825. http://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13513027

Kim, M., Byrne, A. M., & Jeon, J. (2022). The effect of vocational counseling interventions for adults with substance use disorders: A narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084674

Kingston, R. E. F., Marel, C., & Mills, K. L. (2017). A systematic review of the prevalence of comorbid mental health disorders in people presenting for substance use treatment in Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review, 36(4), 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12448

Király, O., Potenza, M. N., Stein, D. J., King, D. L., Hodgins, D. C., Saunders, J. B., Griffiths, M. D., Gjoneska, B., Billieux, J., Brand, M., Abbott, M. W., Chamberlain, S. R., Corazza, O., Burkauskas, J., Sales, C. M. D., Montag, C., Lochner, C., Grünblatt, E., Wegmann, E., . . . Demetrovics, Z. (2020). Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus guidance. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 100.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152180

Krishnamurthy, S., & Chetapalli, S. K. (2015). Internet addiction: Prevalence and risk factors, A cross-sectional study among college students in Bengaluru, the Silicon Valley of India. Indian Journal of Public Health, 59(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-557X.157531

Lee, T. K. (2014). Addiction education and training for counselors: A qualitative study of five experts. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 35(2), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1874.2014.00027.x

Leijdesdorff, S., van Doesum, K., Popma, A., Klaassen, R., & van Amelsvoort, T. (2017). Prevalence of psychopathology in children of parents with mental illness and/or addiction: An up to date narrative review. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(4), 312–317. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000341

Marshall, D. T., Elmer, J. W., Hebert, C. C., & Barringer, K. E. (2025). Counseling research trends: A content analysis 2016–2020. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research, 52(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15566382.2024.2368647

Matsuzaka, S., & Knapp, M. (2020). Anti-racism and substance use treatment: Addiction does not discriminate, but do we? Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 19(4), 567–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2018.1548323

McCuistian, C., Fokuo, J. K., Dumoit Smith, J., Sorensen, J. L., & Arnold, E. A. (2023). Ethical dilemmas facing substance use counselors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Substance Use: Research and Treatment, 17, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/11782218231158338

Medeiros, G. C., & Grant, J. E. (2018). Gambling disorder and obsessive–compulsive personality disorder: A frequent but understudied comorbidity. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.50

Menne, V., & Chesworth, R. (2020). Schizophrenia and drug addiction comorbidity: Recent advances in our understanding of behavioural susceptibility and neural mechanisms. Neuroanatomy and Behaviour, 2(1), e10. https://doi.org/10.35430/nab.2020.e10

Molla, E., Tadros, E., & Cappetto, M. (2018). The effects of alcohol and substance use on a couple system: A clinical case study. The Family Journal, 26(3), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480718795500

Moro, R. R., Wahesh, E., Likis-Werle, S. E., & Smith, J. E. (2016). Addiction topics in counselor educator professional development: A content analysis. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 37(1), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaoc.12012

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2024). Underage drinking in the United States (ages 12 to 20). https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-topics/alcohol-facts-and-statistics/underage-drinking-united-states-ages-12-20

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2023, December 13). Reported drug use among adolescents continued to hold below pre-pandemic levels in 2023. https://nida.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/2023/12/reported-drug-use-among-adolescents-continued-to-hold-below-pre-pandemic-levels-in-2023

National Institutes of Health. (2020, September 15). Vaping, marijuana use in 2019 rose in college-age adults.

https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/vaping-marijuana-use-2019-rose-college-age-adults

Nelson, S. E., Van Ryzin, M. J., & Dishion, T. J. (2015). Alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use trajectories from age 12 to 24 years: Demographic correlates and young adult substance use problems. Development and Psychopathology, 27(1), 253–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000650

Oh, J., Stewart, A. E., & Phelps, R. E. (2017). Topics in the Journal of Counseling Psychology, 1963–2015. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(6), 604–615. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000218

Oka, T., Hamamura, T., Miyake, Y., Kobayashi, N., Honjo, M., Kawato, M., Kubo, T., & Chiba, T. (2021). Prevalence and risk factors of internet gaming disorder and problematic internet use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A large online survey of Japanese adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 142, 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.07.054

Patton, R., Goerke, J., Fye, J., & Katafiasz, H. (2019). Does hazardous alcohol use impact individual and relational functioning among couples seeking couples therapy? The Family Journal, 27(3), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480719844033

Pennay, A., Cameron, J., Reichert, T., Strickland, H., Lee, N. K., Hall, K., & Lubman, D. I. (2011). A systematic review of interventions for co-occurring substance use disorder and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 41(4), 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2011.05.004

Ponterotto, J. G., Mathew, J. T., & Raughley, B. (2013). The value of mixed methods designs to social justice research in counseling and psychology. Journal for Social Action in Counseling & Psychology, 5(2), 42–68. https://doi.org/10.33043/JSACP.5.2.42-68

Pu, Y., Liu, Y., Qi, Y., Yan, Z., Zhang, X., & He, Q. (2023). Five-week of solution-focused group counseling successfully reduces internet addiction among college students: A pilot study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 12(4), 964–971. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2023.00064

Ricciutti, N. M. (2023). Counselors’ stigma toward addictions: Increasing awareness and decreasing stigma. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 17(3). https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol17/iss3/6

Ricciutti, N. M. & Storlie, C. A. (2024). The experiences of clinical mental health counselors treating clients for process/behavioral addictions. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 42(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2023.2267004

Sánchez-Hervás, E., Gómez, F. J., Villa, R. S., García-Fernández, G., García-Rodríguez, O., & Romaguera, F. Z. (2012). Psychosocial predictors of relapse in cocaine-dependent patients in treatment. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 748–755. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n2.38886

Schulenberg, J. E., Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Miech, R. A., & Patrick, M. E. (2019). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2018: Volume 2, College students & adults ages 19–60. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/mtf-vol2_2018.pdf

Sharif, S., Guirguis, A., Fergus, S., & Schifano, F. (2021). The use and impact of cognitive enhancers among university students: A systematic review. Brain Sciences, 11(3), 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11030355

Sherba, R. T., Coxe, K. A., Gersper, B. E., & Vinley, J. V. (2018). Employment services and substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 87, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.01.015

Siu, A. M. H., Fung, M. S. M., Cheung, P. P. P., Shea, C. K., & Lau, B. W. M. (2019). Vocational evaluation and vocational guidance for young people with a history of drug abuse. WORK: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation, 62(2), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-192867

Sperandio, K. R., Goshorn, J. R., Moh, Y. S., Gonzalez, E., & Johnson, N. G. (2023). Never ready: Addictions counselors dealing with client death. Journal of Counseling & Development, 101(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12440

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863.

https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024). 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/dataset/national-survey-drug-use-and-health-2022-nsduh-2022-ds0001

Sylvestro, H. M., Glance, D. E., Ripley, D., & Stephenson, R. (2023). Elementary school counselors’ experiences working with children affected by parental substance use. Professional School Counseling, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X231182142

Torvik, F. A., Røysamb, E., Gustavson, K., Idstad, M., & Tambs, K. (2013). Discordant and concordant alcohol use in spouses as predictors of marital dissolution in the general population: Results from the Hunt Study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(5), 877–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12029

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). Substance abuse, behavioral disorder, and mental health counselors.

http://www.bls.gov/ooh/community-and-social-service/substance-abuse-behavioral-disorder-and-mental-health-counselors.htm

Wahesh, E., Likis-Werle, S. E., & Moro, R. R. (2017). Addictions content published in counseling journals: A 10-year content analysis to inform research and practice. The Professional Counselor, 7(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.15241/ew.7.1.89

Wester, K., & McKibben, B. (2019). Integrating mixed methods approaches in counseling outcome research. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 10(1), 1–11. http://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2018.1531239

Wilson, A. D., & Johnson, P. (2013). Counselors’ understanding of process addiction: A blind spot in the counseling field. The Professional Counselor, 3(1), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.15241/adw.3.1.16

Wing Lo, T., Yeung, J. W. K., & Tam, C. H. L. (2020). Substance abuse and public health: A multilevel perspective and multiple responses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072610

Zhang, X., Shi, X., Xu, S., Qiu, J., Turel, O., & He, Q. (2020). The effect of solution-focused group counseling intervention on college students’ internet addiction: A pilot study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072519

Natalie M. Ricciutti, PhD, NCC, LPCC, LCASA, is an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina Charlotte. Willough Davis, MEd, NCC, LCMHC, LCASA, is a doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina Charlotte. Correspondence may be addressed to Natalie M. Ricciutti, University of North Carolina Charlotte, 9201 University City Blvd., Charlotte, NC 28223, nricciut@charlotte.edu.