Sachin Jain, Santiago Silva

One of the major flaws in current psychological tests is the belief that a prediction/diagnosis can be made that would tell an individual whether he is heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual. What is needed within the profession, however, is an assessment that has the sensitivity to help clients explore their sexual orientation. A pilot 100-item Sexual Orientation Scale was developed after interviewing 30 self-identified gay men who considered themselves happy/satisfied. The items summarized the thoughts and feelings of these 30 men during the discovery process and ultimate acceptance of their sexual orientation. The scale was then completed by 208 male participants. The Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient was calculated for the initial 100-item version of the Sexual Orientation Scale along with item analysis and factor analysis. These statistical manipulations were computed to help eliminate items that did not discriminate well. The final version of the Sexual Orientation contains 43 items. Implications for the use of this scale and future directions in research are further explored.

Keywords: sexual orientation, scale development, males, assessment, exploration

As children grow up in our society, they are introduced to a wide range of knowledge about sexual behavior by their parents, siblings, and peers. Part of their education addresses the ideas of sexual orientation and/or preference. The inherent messages in this education are that a person is either heterosexual (sexually attracted to members of the opposite sex), homosexual (sexually attracted to members of the same sex), or bisexual (sexually attracted to members of both sexes).

Historical Overview of Sexual Orientation

A number of theories on the origin of homosexuality have attempted to define homosexuality. A number of these theories (c.f. Drescher, 2008; Ellis, 1936; Freud, 1922/2010; Krafft-Ebing, 1887/1965; Nuttbrock et al., 2009) place sexual orientation within the context of an individual’s overall sex role identity. These individuals link sexual attraction for men toward women with a masculine sex role orientation and sexual orientation toward men with a feminine sex role orientation (Axam & Zalesne, 1999; Mata, Ghavami & Wittig, 2010; Storms, 1980). Sexual orientation refers to a particular lifestyle (behavior) that an individual displays. Storms (1980) and Moradi, Mohr, Worthington, & Fassinger (2009) found most theories about the nature of sexual orientation emphasize either the person’s sex role orientation or erotic orientation. Although these assumptions have had a major impact on the development of theories, research, clinical practice, and even popular stereotypes, neither assumption has been adequately tested in past research. A homosexual person is one defined as having preferential erotic attraction to members of the same sex and usually (but not necessarily) engaging in overt sexual relations with them (Crooks & Baur, 2008; Marmor, 1980).

Cass (1984) and Harper & Harris (2010) identified four steps in the discovery process that people experience as they begin to identify their sexual orientation:

1. Individuals come to perceive themselves as a homosexual by adopting a self-image of what it means to be homosexual.

2. Individuals take this self-image a step further and allow it, through interaction with others, to become a homosexual identity.

3. Individuals assume the necessary affective, cognitive, and behavioral strategies in order to effectively manage this identity in everyday life.

4. Individuals find a way with which to incorporate the new identity into an overall sense of self.

Assessment of Sexual Orientation

Fergusson & Horwood (2005) wrote a review of the multitude of methods that have been used to assess sexual orientation. Conceptualization of sexual orientation as dichotomous (i.e., heterosexual and homosexual) was overturned over 60 years ago by Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin (1948) and by Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin, and Gebhard (1953). These studies resulted in the development of a 7-point scale in which 0 represented exclusive heterosexuality and 6 represented exclusive homosexuality. Three on the scale indicated equal homosexual and heterosexual responsiveness. Individuals were rated on this continuum based upon their sexual behavior and physical reactions (i.e., physical attraction to desired partners) (Coleman, 1987; Fergusson & Horwood, 2005).

Although this notion that people fall in a continuum better represented the realities of the world (Bagley & Tremblay, 1997; Silenzio, Pena, Duberstein, Cerel, & Knox, 2007), the Kinsey Scale has many limitations for accurately describing an individual’s sexual orientation. The scale assumes that sexual behavior and erotic responsiveness are the same within individuals. In response to this criticism, Bell and Weinberg (1978) used two scales in their extensive study of homosexuality. They examined two scales: one for sexual behavior, and one for erotic fantasies. Bell & Weinberg (1978) found discrepancies between the two ratings. Paul (1984) and Garnets & Kimmel (2003) also reported discrepancies in approximately one-third of their homosexual samples. It was reported that most men saw their behavior as more exclusively homosexual than their erotic feelings (Coleman, 1987; Fergusson & Horwood, 2005; Schwartz, Kim, Kolundzija, Rieger & Sanders, 2008).

Coleman (1987) and Fergusson & Horwood (2005) suggested that while this dichotomous and continuous view of sexual orientation represented an improvement in assessment of sexual orientation, several clinicians and researchers have recommended additional dimensions (Fox, 2003). These dimensions are those based upon both the biological sex of the partner and the biological dichotomous sex of the individual.

As the literature on psychological testing and homosexuality unfolded, it became clear that tests were not very effective in creating special scales, signs or scoring patterns that could differentiate homosexuals from heterosexuals (Garnets & Kimmel, 2003; Paul, Weinrich, Gonsiorek, & Hotvedt, 1982). Homosexuality was no longer being studied as an illness. Contrastingly, literature has brought forth strong data that dismiss the notion that homosexuality is a disorder (Cass, 1984; Coleman, 1982; Harper & Harris, 2010; Henchen & O’Dowd, 1977; Morin & Miller, 1974; Tripp, 1975; Troiden, 1977; Weinberg, 1978).

One of the major flaws in current psychological tests is that there is a belief that a prediction/diagnosis can be made that would tell an individual whether he is heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual. It is the authors’ belief that it is inappropriate to predict what kind of lifestyle an individual will/should follow. What is more feasible is to assist an individual as he or she explores the experience of uncertainty. Therefore, an instrument is needed that has the sensitivity to help clients explore their sexual orientation, not one that identifies levels of disturbance.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study was to construct an instrument that would help counselors in assisting clients who wish to explore sexual orientation. The instrument was to:

• Identify issues that need to be addressed by the client during the discovery of sexual orientation.

• Focus on issues such as self-definition, self-acceptance, fears, sexual fantasies, and understanding of lifestyle.

• Provide an information base for counselors as they help their clients unfold significant characteristics of their personality.

• Provide counselors a tool for helping clients meet the challenges they face now and will face in the future.

Method

Participants

The volunteer population of this study consisted of males who were either a) receiving personal counseling at a university counseling service, community mental health agency, and/or private practice; b) enrolled in introductory psychology classes at universities or community colleges; or c) participating in local men’s groups (i.e., Jaycees, Lions Clubs, support groups, etc.).

Two universities in California, eight universities in Texas, and one university in Wisconsin assisted in the collection of data. Three mental health agencies and four private counseling centers also were recruited for assistance in data collection. The private counseling centers served primarily gay and lesbian clients from the Dallas/Ft. Worth area.

Directors and/or counselors at the mental health sites mentioned above were visited. The purpose of the study was explained and they were asked if they would approach their clients (straight and gay) to determine their willingness to participate in the study. If the counselors were willing to speak to their clients, they were given instructions to share with clients who agreed to participate. They were instructed to give the client the research packet and return the completed information in the enclosed addressed/stamped envelope. Seventy-five agreed and completed packets from this group of mental health agencies were obtained.

Permission from psychology professors at the universities and/or colleges to address their introductory psychology classes was obtained for recruiting more subjects. The purpose of the study was shared with the class, willing participants were moved to another classroom, and they completed the research packet. One hundred and six packets were completed through this procedure.

Men’s groups were approached to obtain additional participants. Groups such as Jaycees, Lions Clubs, and Gay Men’s Support Groups were contacted and visited. A presentation was made that addressed the purpose of the study. Willing participants were provided with information packets, which they returned in enclosed envelopes. Thirty-three completed packets from representatives of the men’s groups were received. Twenty-eight of the 33 came from gay men’s support groups.

Demographic information from the personal data form was summarized and examined across the variable of sexual orientation on the following factors: educational level, socio-economic status, age, ethnicity, self-rating on the Kinsey Sexuality Scale and whether or not the participant was currently in counseling or psychotherapy. The males in the sample identified themselves as being either homosexual (gay) or heterosexual (straight). The males self-identified as gay or straight by rating themselves on the seven-point Kinsey Sexuality Scale (0=exclusively heterosexual to 6=exclusively homosexual). Straight responses were identified as those of which the men rated themselves as zero (0) or one (1) and gay responses were identified as those in which the men rated themselves as five (5) or six (6) on the Kinsey scale. Only six subjects rated themselves as 2, 3 and 4. The scales completed by these 6 subjects were not used in this study.

The sample consisted of a total of 208 men from cities in Texas, Wisconsin, and California: 132 were between the ages of 18–25 (63.5%); 52 were between the ages of 26–33 (25.0%); and 24 were between the ages of 34–40 (11.5%). According to the Kinsey Scale Rating, 104 were straight (50%) and 104 were gay (50%). Of the men who participated in the sample, 85 (40.9%) had received counseling and 123 (59.1%) had not.

Procedure

The first procedure consisted of the development of the items for the Sexual Orientation Scale. In order to achieve this task, thirty gay men who described themselves as being happy/satisfied with the gay lifestyle were interviewed. The men were identified via personal contacts and gay organizations. Their input was used to develop items for the Sexual Orientation Scale.

Three small group meetings of approximately two hours each with about ten men were scheduled. Each meeting began with a statement of the purpose of the groups and the study. It was explained that data was being collected to formulate a scale that would help people clarify questions about their sexual orientation. It was explained that the scale was not designed to label whether someone was gay or straight, but simply to identify issues surrounding sexual orientation. Time was allotted for questions and answers.

Participants were asked for permission to record the group session. When permission was obtained, participants were asked about their experience of the discovery process of their sexual orientation (e.g., “What struggles did you experience?” “What questions did you ask yourself during this discovery process?” “What were you feeling?” “Did you get in touch with any fears?” “What kind of sexual fantasies did you experience?”). These questions were asked in order to help the participant recall their discovery process. Participants were allowed to ask each other questions and/or identify with what was being shared in a casual and informal atmosphere. Recordings of the three small group meetings provided the source for the 100 items that represented thoughts and feelings the men experienced during their discovery process. These 100 items consisted of Phase 1 of the Sexual Orientation Scale development.

After the pilot scale was developed, packets were sent out to university counseling services, psychotherapists in private practice, and community mental health agencies. The packet consisted of: (a) a personal data form, (b) the 100-item Sexual Orientation Scale, (c) an informed consent form, and (d) an addressed and stamped envelope. Data on the 100-item Sexual Orientation Scale also was collected from different men’s groups and from the introductory psychology classes both at universities and community colleges.

Two hundred and eight packets were completed. Coincidently, 104 responses were from gay individuals, and 104 were straight responses. The responses were then transferred onto Scantrons and submitted for analysis.

Instrument Development

Item construction. Tests are composed of a number of items that are used to measure a particular subject. According to Wesman (1971), an item may be defined as a scoring unit. Creating an item should be taken seriously because each item in a test produces a unit of information regarding the person who takes the test.

Writing a test item is an involved process. Test items need to be subjected to constant evaluation in order to ensure, as much as possible, that they are measuring what they are intended to measure. The items developed for the Sexual Orientation Scale represent two variables: self-image and eroticism. These variables have been continuously identified in sexual-orientation literature (Cass, 1984; Coleman, 1982; Eliason & Schope, 2007; Grace, 1979) as variables that must be examined when attempting to answer questions regarding sexual orientation. Self-image is defined as involving self-definition, self-acceptance, fears and an understanding of lifestyle. Eroticism is defined as sexual fantasies.

Item analysis. According to Anastasi (1988), items on an instrument may be analyzed quantitatively, in regards to their statistical properties. When examining items qualitatively, content validity is considered as well as the evaluation of items in terms of effective item-writing procedures. Quantitative analysis primarily includes the measure of item difficulty and item discrimination (Anastasi, 1988).

Item difficulty answers the question: How hard or easy was a particular item for the group of participants? Item discrimination refers to the degree to which an item differentiates correctly among test takers in that behavior that the test is designed to measure (Anastasi, 1988, p. 210). Item discrimination was calculated as a correlation coefficient between the item score and the total score. Correlation coefficient indicates the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two random variables.

Results and Discussion

Item Design for the Sexual Orientation Scale

In designing the Sexual Orientation Scale, two areas of interests were salient. They were self-images and eroticism. The literature on sexual identity formation strongly supported the examination of these two interest areas during the discovery process of one’s sexual orientation. The importance of examining self-images and eroticism was further supported in the early stages of this study that resulted in the identification of the initial 100 items of the Sexual Orientation Scale.

Thirty self-identified gay men were interviewed regarding their discovery process. While reviewing interviews, items were generated that represented their thoughts and feelings. Examination of items clearly indicated that issues such as self-acceptance, understanding fears, and eroticism were being confronted during the discovery process.

Next, these 100 items were then subjected to an item analysis that resulted in identifying 45 items with item discrimination indices of 0.50 or higher. These 45 items were then further subjected to a factor analysis and an alpha coefficient.

An arbitrary decision was then made to use a 0.5 or higher factor loading in examining items. A strict convention of 0.5 or higher was used in order to identify the most discriminating items. The factor analysis identified the same items the item analysis identified. The alpha coefficients were as follows: overall= 0.924; straights= 0.723, gays= 0.653.

The factor analysis also identified four factors that were consistent with issues identified by both the literature and the initial 100 items. After reviewing the items in these factors, they were labeled as:

attraction to same sex

attraction to opposite sex

self-acceptance of gay behavior/attitudes

fears

Item Analysis

Anastasi (1988) pointed out that items on an instrument may be analyzed qualitatively, in terms of their content and form, and quantitatively, in terms of their statistical properties. The item analysis performed on the initial 100 items of the Sexual Orientation Scale focused on a quantitative analysis and more specifically on the measures of item difficulty and item discrimination.

Item difficulty refers to the percentage of subjects that endorse certain items on the scale. The closer the difficulty level approaches 0.50, the more differentiations the items can make (Anastasi, 1988).

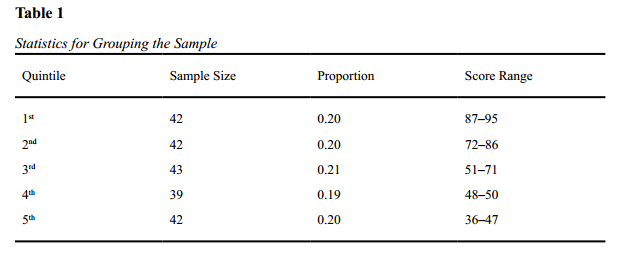

Item discrimination refers to how effective the item discriminates between the two groups. Therefore, the higher the item discrimination score, the more effectively the item will differentiate between the two groups (gays/straights). Table 1 shows how the sample was grouped in order to establish an item-to-total score correlation, which is identified as a useful exercise to select items.

Based on the total score, the respondents were divided into quintiles (groups of approximately 40 subjects). A total score was established by assigning a value of 1 to true responses and a value of 2 to false responses. A true response indicated the way a gay man would respond. An item difficulty, identified in the item analysis as proportion of subjects that responded correctly to the item (PROP) and item discrimination, identified in the item analysis as a point biserial correlation coefficient (RPBI), were calculated for each item.

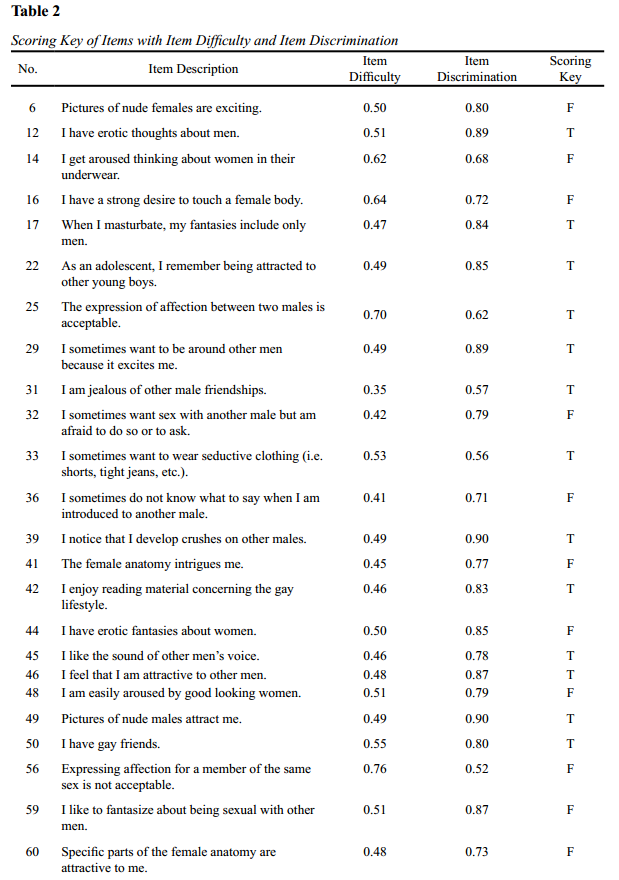

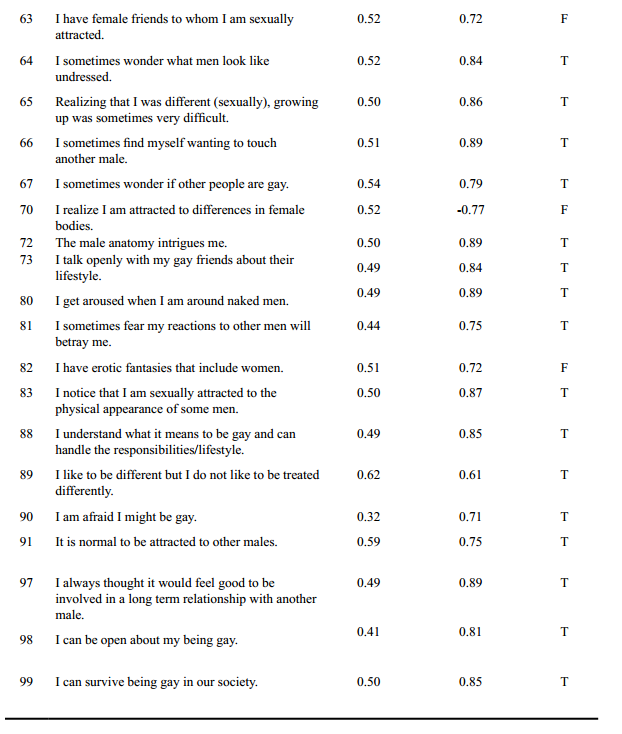

Table 2 outlines the item difficulty and item discrimination score and the scoring key of the initial 100 items. The asterisks identify the scores for the 43 items on the final version of the Sexual Orientation Scale. Of the final 43 items, approximately 76.7% of the items have a difficulty score that range from 0.40 to 0.60. Since Anastasi (1988) stated that the closer the difficulty level approaches 0.50, the more differentiations the item can make, it is safe to infer that the majority of the items on the Sexual Orientation Scale possessed good potential for differentiating between responses of the two groups. The remaining 23.3% of the items were not far behind. None of the item difficulty scores were less than 0.32 or higher than 0.76. This shows that the result of these items do not differentiate as well, but well enough to contribute to the overall reliability and validity of the Sexual Orientation Scale.

According to Anastasi (1988), the items that have low correlations with total score should be deleted and the items with the highest average inter-correlations will be retained. These items were retained because they are the ones that discriminate well and increase the validity of the test.

Analysis showed that 43 items on the initial 100-item Sexual Orientation Scale scored 0.50 or higher on the item discrimination index. Since the item discrimination refers to the degree to which an item differentiates correctly among test takers in the behavior that the test is designed to measure, one could assume the majority of the items on the Sexual Orientation Scale effectively differentiates between the two groups (gay/straight) that were tested.

Results of Item Analysis

The 45-item version of the Sexual Orientation Scale was a result of an item analysis done on the initial 100-item scale. The original data analysis identified 17 factors. An item discrimination index of 0.50 or higher was used to identify the items for the final version of the scale. Items that exhibited a higher level of commonality were selected. The 55 items that were deleted did not discriminate as well.

The 45 items were then submitted to the following statistical procedures: (a) Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for the overall sample, for the straight sample, and for the gay sample; and (b) a factor analysis was conducted via the running of five, four, three and two factor solutions on the overall sample (N=208). The factor analysis was done for the purpose of further validating the Sexual Orientation Scale.

Naming of the Factors

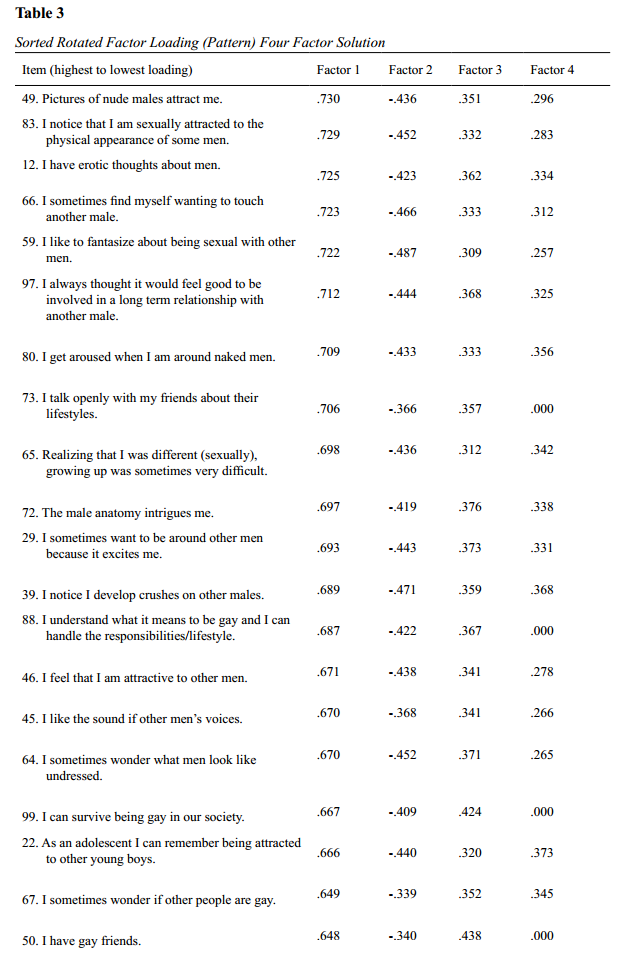

After creating and reviewing a SCREE Plot with the Eigen values of the 45 items, the researchers identified a bend that began to occur around the three, four and five factors. All factor solutions were investigated, and a decision was made to use the four-factors solution because (a) the items fit the four factors very well, and (b) the addition of a fifth factor accounted for negligent increase in the total variance. Every item in each factor carried a common theme.

The items in the four-factor solution were reviewed. Finally, two of the 45 items did not have a factor loading of 0.5 or higher. In keeping with the arbitrary decision of only using those items with a 0.5 factor loading or higher (for the purpose of implementing a stricter convention), items 36 and 15 were deleted. The final version of Sexual Orientation Scale resulted in having 43 items.

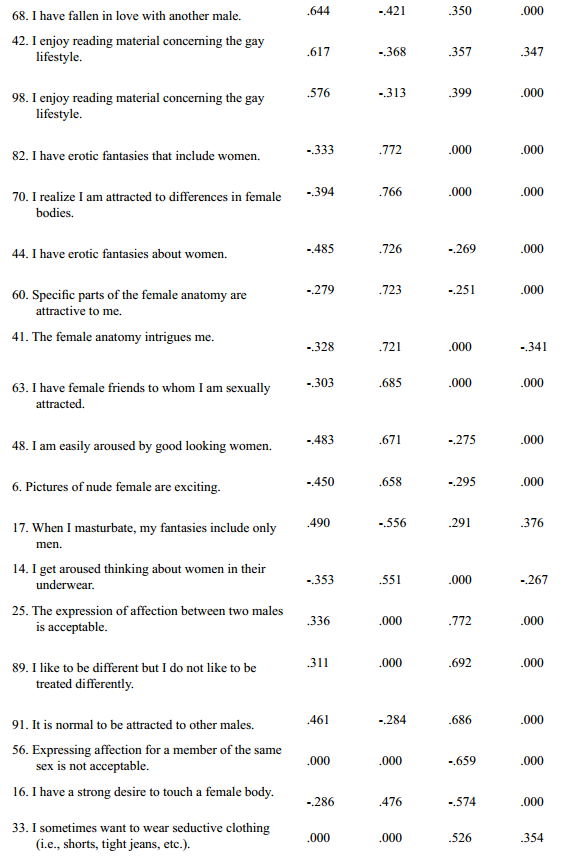

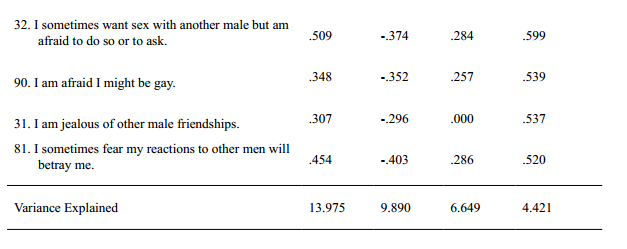

Table 3 summarizes the four factors solution by identifying the sorted rotated factor loadings of each item in each factor. Items 12, 22, 29, 39, 42, 45, 46, 49, 50, 59, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 72, 73, 80, 83, 88, 97, 98, and 99 loaded on Factor One with factor loadings ranging from 0.58 to 0.73. The common theme was sexual attraction to members of the same sex. The items in Factor One identified issues such as being attracted to nude males, erotic thoughts about men, masturbatory fantasies involving men only, relationships with males, etc. Therefore, Factor One was named “Attraction to Same Sex.”

Items 6, 14, 17, 41, 44, 48, 60, 63, 70, and 82 of Factor Two in Table 3 also had sexuality as their common theme. However, the sexual attraction addressed in the above items was towards members of the opposite sex. Their factor loadings ranged from 0.55 to 0.78. The items in Factor Two brought to surface issues dealing with erotic fantasies about women only, thoughts about women that led to sexual arousal, etc. Due to a common theme in these items, Factor Two was named “Attraction to Opposite Sex.”

Factor Three in Table 3 was comprised of items 16, 25, 33, 56, 89, and 91. These items had factor loadings ranging from 0.53 to 0.78. In examining these items, it was evident that the common theme surrounding the items was that of self-image and self-concept. The items in Factor Three addressed issues such as self-expression, expression of affection to another male, the acknowledgement of individual differences and the normalcy of being attracted to other men. Factor Three was named “Self-Acceptance of Gay Behaviors/Attitudes.”

Items 31, 32, 81, and 90 in Table 3 loaded onto Factor Four with loadings that ranged from 0.52 to 0.60. The common theme among these items was fear, which pertained to issues faced more often than not by gay men. The items addressed concerns in areas such as wanting to be sexually active with other men, jealousy, noticeable reactions to other men and fear of being gay. Because of the obvious common theme, Factor Four was named “Fears.”

It is vital to note that the four factors identified via the factor analysis represented those themes continually found in sexual orientation literature. Cass (1979 & 1984), Grace (1979) and Coleman (1982) consistently addressed the importance of examining the variables of self-images and eroticism during the discovery process of one’s sexual orientation. All these factors are clearly identified in the 43 items in the four-factor solution done on the final version of the Sexual Orientation Scale.

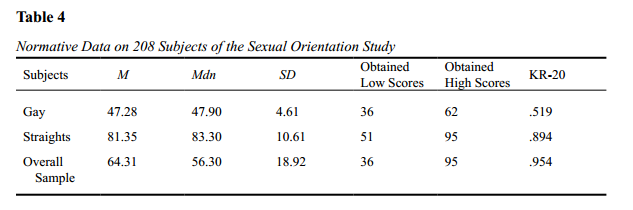

Reliability

A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was performed in order to establish the reliability of the final 43-item version of the Sexual Orientation Scale. An alpha coefficient was done on the overall sample (N=205), the straight sample (N=103), and the gay sample (N=102). The overall sample has an N of 208. Three completed scales (1 straight respondent and 2 gay respondents) were eliminated because they did not complete the initial 100 items. The alphas for the 43-item version were 0.93 for the overall sample, 0.72 for the straight sample and 0.65 for the gay sample.

Construct-Related Validity

Internal consistency is a procedure used to establish construct validity. A statistical procedure used in this study to establish internal consistency was Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient; this statistic also was used to establish instrument reliability (Miller, 1987). Table 4 shows the alphas which clearly exhibit the homogeneity for the items on the Sexual Orientation Scale.

A factor analysis was performed on the 45 items to identify the prevalent factors. After the factor analysis was done, four factors were identified as the most important factors that need to be examined when struggling with the uncovering discovery process of an individual’s sexual orientation. They are Attraction to Same Sex, Attraction to Opposite Sex, Self-Acceptance of Gay Behavior/Attitudes, and Fears. The items and other data on each factor are summarized in the following table. Normative data also was generated on the overall sample, the gay sample, and the straight sample. This was done for interpretation purposes. Table 4 summarizes the established normative data.

Limitations

This study contained methodological features which resulted in limitations. The major areas of limitations were (a) the sampling procedures and (b) generalizability.

Sampling Procedures

The initial 100-item Sexual Orientation Scale resulted from interviews with self-identified gay men who stated they were happy/satisfied as gay men. Only 30 men were interviewed. Although this number was an acceptable number, a larger number of men interviewed may have provided additional insights.

Of this group of 30 men (participating in the development of the items for the Sexual Orientation Scale) from cities in the Rio Grande Valley (RGV) in South Texas, 90% were Hispanic college graduates. Being a Hispanic gay man in the RGV in South Texas is difficult. The machismo attitude is somewhat prevalent in this area. This, coupled with a strong Catholic belief about homosexuality makes life as a gay man very secretive in this area. Thus, it is important to note that the initial 30 subjects were men who are openly gay, educated, motivated, and obvious risk takers. The sample group, therefore, may not have represented the “typical” gay man in the United States. Moreover, a different or more thorough perspective about what is involved in the discovery process with respect to sexual orientation might have risen if there had been a more diverse group of gay men in terms of ethnicity and geographical area.

The sample size (N = 208) utilized for the statistical item analysis was small. Although acceptable for this study, a much larger sample would likely improve the scale’s reliability and validity. The sample in this study did not include women. Women were excluded because it was suspected that gay men and lesbian women experience a different discovery process and that a parallel, yet different study is necessary for females.

Lastly, the two samples (gay/straight) are not actually directly comparable because, in essence, they were not selected in the same way. For example, a large percentage (65.4%) of the gay sample compared to 16.3% of the straight sample was enrolled in counseling. One can ascertain that most of the gay samples were selected from university counseling centers, mental health agencies, and the private sector. Contrastingly, the straight sample was selected from introductory psychology classes and from the membership of men’s groups (civic and/or support).

Generalizability

The generalizability of the results of this study is limited to men who are between the ages of 18 and 40 and who are either receiving counseling services from university counseling centers, mental health agencies, or the private sector, or who are in introductory psychology classes or members of men’s groups. The generalizability of this study is further limited to Hispanic and Caucasian men who met the research criteria.

Recommendations

The following are recommendations to either improve the present study’s design or identify areas for future research:

• Obtain a more culturally diverse sample by including representatives of other ethnic groups along with representatives from the Hispanic and Caucasian groups. This would increase the potential of gathering different perspectives and insights as well as increase the generalizability of the results.

• Utilize a larger more diverse sample in order to compare the reliability and validity data obtained in this study with other studies. A test re-test might be considered so as to verify the reliability of the Sexual Orientation Scale.

• In order to minimize a client’s tendency to answer the way they think their therapist or counselor wants them to, a lie/consistency scale may need to be established for the Sexual Orientation Scale. This may be done by including items that emphasize the same information, but written in a different manner.

Once the Sexual Orientation Scale has undergone further empirical investigation and eventual modifications, the use of the scale in counselor training programs should be considered. This would be done in hopes of (a) educating future counselors in how to assist clients who are confused about their sexual orientation, (b) increasing one’s sensitivity to and knowledge about gay/lesbian issues, and (c) requiring to some extent that future counselors accept and understand their own biases in regards to individual differences and more specifically to gays and lesbian.

References

Anastasi, A. (1988). Psychological testing. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Axam, H. S., & Zalesne, D (1999). Simulated sodomy and other forms of heterosexual horseplay: Same sex sexual harassment, workplace gender hierarchies, and the myth of the gender monolith before and after oncale. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism, 11, 155–253.

Bagley, C., & Tremblay, P. (1997). Suicidal behaviors in homosexual and bisexual males. Crisis, 18(1), 24–34.

Bell A. P., & Weinberg, M. S. (1978). Homosexualities: A study of diversity among men & women. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Cass, V. C. (1979). Homosexuality identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality, 4, 219–234.

Cass, V. C. (1984). Homosexuality identity formation: Testing a theoretical model. The Journal of Sex Research, 20, 143–167.

Coleman, E. (1982). Homosexuality & psychotherapy: Developmental stages of the coming-out crocess. Journal of Homosexuality, 7, 36–48.

Coleman, E. (1987). Assessment of sexual orientation. Boca Raton, FL: Haworth.

Crooks, R., & Baur, K. (2008). Our sexuality. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Drescher, J. (2008). A history of homosexuality and organized psychoanalysis. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, 36(3), 443–460.

Ellis, H. (1936). Studies in the psychology of sex. New York, NY: Random House.

Eliason, M. J., & Schope, R. (2007). The health of sexual minorities: Shifting sands or solid foundation? Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity formation. New York, NY: Springer.

Fergusson, D. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2005). Sexual orientation and mental health in a birth cohort of young adults. Psychological Medicine, 35(7), 971–981.

Fox, R. C. (2003). Bisexual Identities. In L. Garnets & D. Kimmel (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual experiences (pp. 86–129). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Freud, S. (1922/2010). Group psychology and the analysis of the ego. (J. Strachey, trans.). Charleston, S.C: Nabu Press.

Garnets, L., & Kimmel, D. C. (2003). Psychological perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual experiences. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Grace, J. (1979, November). Coming out alive. Paper presented at the Sixth Biennial Professional Symposium of the National Association of Social Workers. San Antonio, Tx.

Harper, S. R, & Harris, F. (2010). College men and masculinities: Theory, research, and implications for practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Henchen, J. D., & O’Dowd, W. T. (1977). Coming out as an aspect of identity formation. Gay Academic Union Journal: Gai Saber, 1, 18–22.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., Martin, C. E., & Gebhard, P. H. (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders.

Krafft-Ebing, R. V. (1887/1965). Psychopathia sexualis. (H. E. Wedick, Trans.). New York, NY: Putnam.

Marmor, J. (1980). Homosexual behavior. New York, NY: Basic.

Mata, J., Ghavami, N., & Wittig, M. A. (2010). Understanding gender differences in early adolescents’ sexual prejudice. The Journal of Early Adolescence 30(1), 50–75.

Miller, D. (1987). Strategy making and structure: Analysis and implications for performance. Academy of Management Journal, 30, 7–32.

Moradi, B., Mohr, J. J., Worthington, R. L., & Fassinger, R. E. (2009). Counseling psychology research on sexual (orientation) minority issues:Conceptual and methodological challenges and opportunities. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 5–22.

Morin, S. F., & Miller, J. S. (1974, March). On fostering positive identity in gay men: Some developmental issues. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Orthropsychiatric Association, San Francisco, CA.

Nichols, P., & Fulkerson, D. (2010). Informing design patterns using research on item writing expertise. Menlo Park, CA: SRI International.

Nuttbrock, L., Bockting, W., Mason, M., Hwahng, S., Rosenblum, A., Macri, M., & Becker, J. (2009). A further assessment of Blanchard’s typology of homosexual versus non-homosexual or autogynephilic gender dysphoria. Archives of Sexual Behavior,40(2), 247–257.

Paul, W., Weinrich, J. D., Gonsiorek, J. C., & Hotvedt, M. E. (1982). Homosexuality: Social, psychological and biological issues. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Paul, J. P. (1984). The bisexual identity: An idea without social recognition. Journal of Homosexuality, 9(2/3), 65–77.

Silenzio, V. M., Pena, J. B., Duberstein, P. R., Cerel, J., & Knox, K. L. (2007). Sexual orientation and risk factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults.American Journal of Public Health 97(11), 2017–2019.

Storms, M. D. (1980). Theories of sexual orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 783–792.

Tripp, C. A. (1975). Homosexual matrix. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Troiden, R. R. (1977). Becoming a homosexual: Research on acquiring a homosexual identity. Unpublished manuscript, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, New York.

Weinberg, T. (1978). On “doing” and “being” gay: Sexual behavior and homosexual male self-identity. Journal of Homosexuality, 4, 143–156.

Wesman, A. G. (1971). Writing the test item. In R.L. Thorndike (Ed.), Educational measurement. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Sachin Jain, NCC, is an Assistant Professor, Department of Counseling, Oakland University, Rochester, MI. Santiago Silva, is a Clinical Professor & Director of the Counseling Assessment Preparation Clinic (CAP) at the University of Texas-Pan American. Correspondence can be addressed to Sachin Jain, Oakland University, Department of Counseling, 2200 N Squirrel Road, Rochester, MI, 48309, sacedu@yahoo.com.