George Davy Vera

In the worldwide community it is not well known that counseling and guidance professional practices have a long tradition in Venezuela. Therefore, this contribution’s main purpose is to inform the international audience about past and contemporary counseling in Venezuela. Geographic, demographic, and cultural facts about Venezuela are provided. How counseling began, its early development, and pioneer counselors are discussed. The evolution of counseling from an education-based activity to counseling as a technique-driven intervention is given in an historical account. How a vision of counselors as technicians moved to the notion of counseling as a profession is explained by describing turning points, events, and governmental decisions. Current trends on Venezuelan state policy regarding counselor training, services, and professional status are specified by briefly describing the National Counseling System Project and the National Flag Counseling Training Project. Finally, acknowledgement of Venezuela’s counseling pioneers and one of the oldest counseling training programs in Venezuela is described.

Keywords: Venezuela, history of counseling, clinical interventions, policy, training programs

Venezuela is located on the northern coast of South America, covering almost 566,694 square kilometers (km; 352,144 square miles). It is bordered by the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, Guyana, Brazil, and Colombia, with a total land boundary of 4,993 km (3,103 miles) and a coastline of 2,800 km (1,740 miles). Its population is approximately 29 million and mostly Catholic. Some aboriginal groups practice their own traditional magical-religious beliefs. Since its independence, emigrants from different parts of the world have helped build the country’s culture and economy. Diverse populations of Arab, Dutch, Chinese, and Japanese, among others, live in Venezuela.

Even though several ethnic groups prevail in the country today, three groups are clearly distinct from its origin: European white, African black and Native aborigines. After five hundred years of blending, three different culturally and ethnically groups have emerged: Mulato (white and black), Zambo (black and aborigine), and Mestizo (white and aborigine). Although Venezuela has ethnic compositions and mixtures, all Venezuelans have the same rights and duties under the Bolivarian Constitution of 1999. More Venezuelan differences and prejudices are related to social, educational, economic, and political status.

Economically, Venezuela has one of the largest economies in South America due to its oil production; however, a large number of its population remains in poverty. Today, the current administration has created different popular programs, called missions, to deal with most Venezuelans’ needs including lack of education, employment, health care, and public safety, among others. So far, according to the United Nations (UN) and UNESCO’s official reports, Venezuela has reached most of its millennium goals established by the UN. Politically, after several years of turmoil, Venezuelan society reached a normal democratic institutional peace in 2004.

Early Developments of Counseling in Venezuela

During the 1930s, counseling in Venezuela began as a form of educational guidance and counseling concerned with academic and vocational issues using mainly psychometric approaches. Some Venezuelan counseling pioneers were European emigrants. In fact, during the 1940s, some school counseling services were created by Dr. Jose Ortega Duran, an educator; Professor Miguel Aguirre, a counselor; Professor Vicente Constanzo, teacher and philosopher; and Professor Antonio Escalona, a career counselor and professor (Benavent, 1996; Calogne, 1988; Vera, 2009). Because of the education and training of these early pioneers, counseling in Venezuela was conceived as an educational, vocational, and career-oriented service.

A formal definition of the counseling and training of professional counselors has slowly evolved from the 1960s to today. Because of the oil industry development, Venezuela moved from an agricultural to an industrial economic base. Because of this, the Venezuelan population grew rapidly and rural farmers moved to the major cities, which were demanding more workers, specialized employees, and technicians. Therefore the demand for better education to satisfy new jobs related to industrial demands and pressured the government to create new policies concerning education. One of the new policies regarded counseling and guidance services. Therefore, in the early 1960s the government created the first counselor education training program (Calogne, 1988; Moreno, 2009; Vera, 2009).

By an agreement between the Ministry of Education and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), counseling professors from the U.S. were hired to train school teachers in counseling and guidance. The training focused on personal counseling techniques and strategies, counseling theory and methods, and educational counseling. Because the training emphasized basic counseling knowledge and techniques for school teachers, a vision of counseling and guidance as educational activities within the scope of the school teacher role emerged. Accordingly, counseling and guidance was understood as a technique-based activity oriented to help students with academic, vocational, career, and personal issues. Later, the Ministry of Education requested that the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas create a formal, three-semester educational training program in counseling and guidance.

As a result, in 1962 the Ministry of Education requested that the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas house the first formal counselor education program in Venezuela. Counseling and guidance was conceived as knowledge and intervention techniques to help with students’ personal growth and academic performance. The term Orientación was chosen to better signify counseling and guidance in Venezuela’s Spanish language. Graduates from this program received a college diploma as orientador. Both terms, orientación and orientador, were thus used in the country for the first time.

Another consequence of the counselor education program at the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas was its contributions to a new vision of counseling as a technique-oriented educational program. Therefore, counseling was conceived as a technical occupation that emerged within the scope of education. By this time, counseling had achieved official and public recognition as a social occupation that required proper education and a set of formal conditions for practice. The Ministry of Education used this new vision of counseling to create the first jobs defined as counselor positions within Venezuela’s educational system (Vera, 2009).

From Counselors as Technicians to the Counseling Profession

Shortly after the first graduates in counseling started their practice, the Ministry of Education understood that the practice of counseling and guidance was more complex than originally perceived and realized that the high demand for counseling services was calling for rapid institutional answers to counseling-related questions. As a result, the National Counseling System, known as the Counseling Division of the Ministry of Education, was developed. This organizational structure was responsible for all counseling matters countrywide, including hiring conditions, developing counseling services, supervising, and training requirements. From this Division, counseling as a profession was envisioned as a human development model (Aquacviva, 1985; Calogne, 1988).

Because counselor employment was now available within the Ministry of Education, several universities established guidance and counseling training options as a five-year bachelor’s degree. Consequently, the first bachelors’ degrees in education majoring in guidance and counseling (mención orientación) were granted in the early 1970s. Master’s level degrees in guidance and counseling granted by the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas were also awarded during this time.

Some of the early graduates from these programs went abroad, mainly to the U.S., to obtain advanced counseling and guidance education and training at the master’s and doctoral levels. Upon returning to Venezuela, they engaged in teaching and training in counseling and guidance at different colleges and some were hired by the Ministry of Education. Other graduates concentrated their energy on organizing counseling professional associations. As a result, American theories, models, and views of the counseling profession in the 1970s and 1980s were fused with Venezuela’s view of counseling and guidance (Vera, 2009).

Because most Venezuelan counselors had been educated abroad, a number of trends in counselor education were adopted. For instance, some bachelors’ level counseling education programs were based on a vision of guidance and vocational education (e.g., Venezuela Central University and the University of Carabobo), while other programs assumed a vocational and academic perspective (e.g., Liberator Pedagogical University), and yet others implemented individual, lifelong approaches (e.g., The University of Zulia and the University Simon Rodriguez). Finally, the Center for Psychological, Psychiatric, and Sexual Studies of Venezuela clearly embraced an educational and mental health counseling standpoint in masters’ level training. (However, for political and governmental reasons, some of these early programs no longer exist.)

Between the 1970s and 1980s professionalism in counseling was embraced because counseling- and guidance-related organizational movements emerged. Counseling associations were organized and began to promote a vision of counseling as an independent profession from education, psychology, and social work. One of these associations was the Zulia College of Professional Counselors (ZCPC), which was responsible for raising the visibility of professional counseling in Venezuela by creating the first Counseling Code of Ethics, advocating for counseling jobs, and becoming a valid interlocutor between professional counselors and the government.

The ZCPC was established by a group of counseling professors and early graduates from the bachelors’ degree of education in counseling and guidance. During the 1970s and 1980s, counselors in this organization started developing a cultural base for counseling knowledge. In particular, ZCPC established professional meetings for discussing counseling profession matters such as advanced education, professional identity, and social responsibility.

By this time, counseling master’s programs were available in several parts of Venezuela. Hence, professionalism came to light and important matters for counseling’s future development were assumed by counselor educators, practitioners, and associations.

Current Trends: Contemporary Concerns for Professional Practice and Education

Currently, several professional matters regarding counseling are taking place in Venezuela, one being the status of counseling as an independent profession. The Venezuela Counseling Associations Federation (FAVO) will soon introduce a legislative proposal concerning professional counseling practice. If it is passed, Venezuelan counselors will have their first counseling practice law granting counselors’ independent professional practice based on research, knowledge, specified training, and educational requirements.

Another important matter is the creation of the Venezuela Counseling System. This system will organize and provide counseling to the population by a diverse delivery of services and programs based on a vision of counseling for personal, social, cultural, and economical enhancement within the context of a humanistic, democratic, participatory, and collective society. The system is designed and based on the Venezuela Bolivarian Constitution, which guarantees human rights related to social inclusion and justice, freedom, education, mental health, vocational needs, employment, lifelong support, and opportunities for individual development and family prosperity. The system is organized into four areas: education, higher education, community, and the workplace or economic sector. The system is already approved by the Ministry of Higher Education and the formal government resolution and implementation process is pending.

The system embraces advanced concepts and new trends related to professionalism, practice, and the social responsibility of counseling professionals. This includes certification for counseling practitioners, supervision, and credentialing via continuing education for professionals in order to ensure quality. Structurally, the system will be connected to all Venezuelan Ministries for functions and planning purposes, but will be independently managed by a national committee appointed by the Ministry of Higher Education, holding advanced degrees in counseling and appropriate counseling credentials.

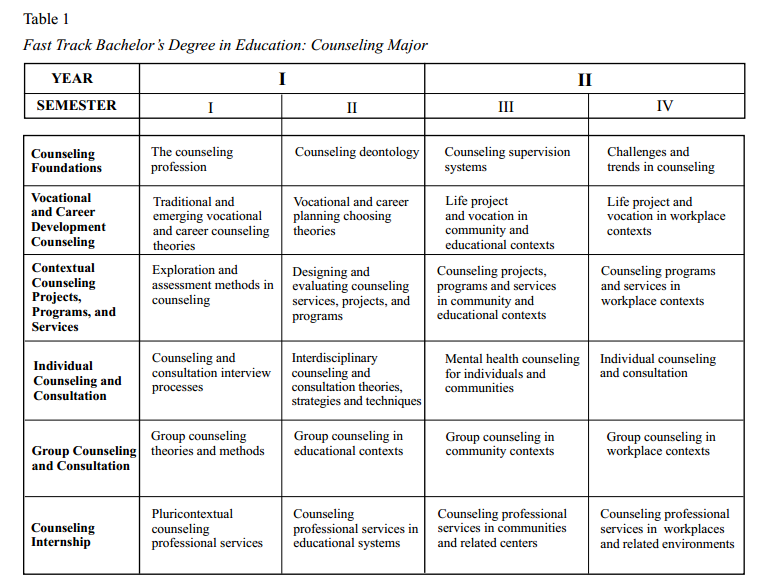

A third matter is related to counseling training programs. Because the Counseling National System will require a large number of trained counselors in the next ten years, new counseling training programs will be created by public and private universities to ensure the quality of counselor training and to satisfy system requirements. Consequently, the government has requested that counseling experts propose a unique counseling training program based on core counseling knowledge, techniques, supervision, and other key features. For details on the proposed counseling program coursework, see Table 1.

The proposed National Counseling Professional Program (NCPP) will be at the bachelor’s level and four semesters long. A unique prerequisite of this program is that applicants must already hold one of these bachelors’ degrees: education, psychology, social work, sociology, industrial engineering, philosophy, pedagogy, or physician.

The proposed NCPP will be organized into core areas and will educate counseling professionals according to the following general objectives:

1. Educate professional counselors to satisfy the needs of the Counseling National System, its subsystems, and any other professional counseling contexts.

2. Develop critical, reflective, dialectical and dialogical counseling professionals. Understand theoretical and conceptual information related to the counseling field and its interdisciplinary sources.

3. Acquire the theory based and applied competencies of the counseling profession in diverse contexts.

4. Understand Venezuelan counseling’s historical roots and its international origins.

5. Understand the ethical dimensions of the counseling profession and the legal characteristics of counseling practice.

6. Actively participate in the development of solidarity, participatory and responsible collectivist citizenship.

7. Articulate counseling professional actions with Venezuela’s social, cultural, and economic development.

8. Use the cultural and social bases of the counseling profession in creating lifelong counseling services.

9. Bond the training and practices of professional counselors with plans and guidelines for Venezuela’s cultural, social, and economic development.

10. Train professional counselors needed for the Venezuelan police.

Other counseling training programs will be developed according to the official training program. Institutions may develop their own specific program, but must include the official requirements.

A last concern is professional counselor certification, supervision, and continuing education. FAVO has worked on these matters since 2004 in collaboration with the NBCC International. FAVO is developing Venezuela’s first National Counselor Certification System as well as conceptualizing a national supervision model and continuing education. FAVO granted the first group of national certified counselors in 2010 and is planning for the first group of trained and certified counselor supervisors in 2011.

Final Thoughts

After years of counselor education evolution and counseling services growth, the professionalization of counseling in Venezuela is now happening, but it depends on Venezuelan counseling leaders to develop a strong advocacy movement. Accordingly, Venezuela’s current political climate has the extraordinary opportunity to pass the Venezuela Counseling Law Proposal in the National Assembly. This may be possible if FAVO has successes in the implementation of the Venezuela National Counseling Certification System because this can help in the task of alerting Venezuela’s professional counselors. Accordingly, counselors’ sense of professionalism might spark the enthusiasm needed for involvement in a strong advocacy movement.

Finally, according to experiences in different parts of the world, it can be concluded that not only in Venezuela, but worldwide, the profession of counseling is an emerging phenomenon; therefore, international counseling institutions and organizations need to begin acting on how to face the worldwide challenges for professional counselors.

References

Benavent, J. (1996). La orientación psicopedagógica en España. Desde sus orígenes hasta 1939. Valencia, VZ: Promolibro.

Calogne, S. (1988). Tendencias de la Orientación en Venezuela. Cuadernos de Educación 135. Caracas, VZ: Cooperativa Laboratorio Educativo.

Moreno, A. (2009). La orientación como problema. Centro de investigaciones populares. Caracas, Venezuela: Colección Convevium.

Vera, G. D. (2009). La profesión de orientación en Venezuela. Evolución y desafíos contemporáneos. Revista de Pedagogia, Universidad Central de Venezuela.

George Davy Vera teaches in the Counselor Education Program, Universidad de Zulia, Maracaibo, Venezuela. Dr. Vera expresses appreciation to Dr. J. Scott Hinkle for editorial comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Correspondence should be directed to George Davy Vera, avenida 16 (Guajira). Ciudad Universitaria, Núcleo Humanístico, Facultad de Humanidades y Educación. Edificio de Investigación y Postgrado. Maracaibo, Venezuela, gdavyvera@gmail.com.