Seth Hayden, Kathy Ledwith, Shengli Dong, Mary Buzzetta

Student veterans often encounter unique challenges related to career development. The significant number of student veterans entering postsecondary environments requires career-development professionals addressing the needs of this population to decide upon appropriate career intervention topics. This study utilized a career-needs assessment survey to determine the appropriate needs of student veterans in a university setting. Student veterans indicated a desire to focus on the following topics within career intervention: transitioning military experience to civilian work, developing skills in résumé-building and networking, and negotiating job offers. Results of the needs survey can be used in the development of a career-related assessment.

Keywords: student veterans, career development, needs assessment, military, career-related assessment

In 2013, there were 21.4 million male and female veterans aged 18 and older in the civilian noninstitutional population (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014a). The post-9/11 GI Bill, authorized by Congress in 2008, has contributed to a large number of veterans seeking postsecondary degrees (Sander, 2012). Since 2008, more than 817,000 military veterans have used the bill to attend U.S. colleges (Sander, 2013). Student veterans face many challenges on college campuses, including transition issues, relational challenges, feelings of isolation, and lingering effects of combat-related injuries (Green & Hayden, 2013).

One of the most significant concerns is that veterans typically experience unemployment at a higher rate than their civilian counterparts (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014b). In 2013, the unemployment rate for Gulf War II-era veterans was 10.1 %; Gulf War I-era veterans 5.5%; and World War II, Korean War, and Vietnam War veterans 5.5% (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014b). Younger veterans in particular struggled with unemployment. As of 2013, about 2.8 million of the nation’s veterans had served during the Gulf War II era (September 2001–present; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014a). The unemployment rate for the Gulf War II-era veterans (10.1%) is significantly higher than their civilian counterparts (6.8%; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014b). As young military personnel continue to return to college campuses, it is important to address the career-readiness needs of this population utilizing evidence-based practices.

Cognitive Information Processing

The Cognitive Information Processing (CIP) approach to career decision making (Sampson, Reardon, Peterson, & Lenz, 2004) has been suggested as a way to aid veterans as they transition into the civilian workforce (Bullock, Braud, Andrews, & Phillips, 2009; Buzzetta & Rowe, 2012; Clemens & Milsom, 2008; Hayden, Green, & Dorsett, in press; Phillips, Braud, Andrews, & Bullock, 2007; Stein-McCormick, Osborn, Hayden, & Van Hoose, 2013). The CIP approach is designed to assist individuals in making both current and future career choices (Sampson et al., 2004; Buzzetta & Rowe, 2012). This theoretical approach states that career problem solving and decision making are skills that can be learned and practiced (Sampson et al., 2004). Once clients have improved their problem-solving and decision-making skills, then they can apply these same skills to choices they make in the future. According to the CIP approach, the key aspects of career problem solving and decision making are self-knowledge, occupational knowledge, decision-making skills, and metacognitions (Sampson et al., 2004). Engels and Harris (2002) suggest that military individuals would benefit from understanding their self-knowledge, occupational information and decision-making skills.

Pyramid of Information Processing

The CIP approach consists of two key components: the pyramid of information processing, or the knowing, and the CASVE cycle, or the doing. The interactive elements are analogous to a recipe used in cooking. The pyramid is like the ingredients for the dish, while the CASVE cycle reflects the necessary steps to make the dish. Both are critical for effective career decision making and problem solving (Sampson et al., 2004). The pyramid of information processing includes three domains involved in career decision making: knowledge, decision-making skills, and executive processing (Sampson et al., 2004). Sampson et al. (2004) theorized that all components of the pyramid are affected by dysfunctional thinking and negative self-talk. The knowledge domain consists of two main areas: self-knowledge and occupational knowledge. Self-knowledge is the cornerstone of a client’s career-planning process, and is comprised of an individual’s knowledge of his or her values, interests, skills, and employment preferences (Reardon, Lenz, Peterson, & Sampson, 2012; Sampson et al., 2004). Occupational knowledge is the second cornerstone of a client’s career-planning process; it encompasses knowledge of options, including educational, leisure, and occupational alternatives, as well as how occupations can be organized.

The decision-making skills domain consists of a systematic process to help clients improve their problem-solving and decision-making skills, and includes the CASVE cycle, which is a multi-phase decision-making process, intended to increase client awareness and improve a client’s decision-making skills. The executive processing domain includes metacognitions, which include an individual’s thoughts about the decision-making process. There are three cognitive strategies included in the executive processing domain: self-talk, self-awareness, and monitoring and controlling an individual’s progress in the problem-solving process. Metacognitions can include dysfunctional career thinking, which can present problems in career decision making, influence other domains in the pyramid, and impact individuals’ perceptions of their capabilities to perform well (Sampson et al., 2004).

CASVE Cycle

The CASVE cycle is used as a means of approaching a career problem or decision, and consists of five sequential stages (communication, analysis, synthesis, valuing, and execution), with repeated circuits when the problem still exists or new problems arise (Sampson et al., 2004). An individual enters the CASVE cycle after receiving either internal or external cues that he or she must make a career decision. In the communication stage, individuals are required to examine these prompts, and identify a gap that exists between where they are currently and where they would like to be. In the analysis phase, individuals clarify their existing self-knowledge by determining their occupational preferences, abilities, interests and values. The process of clarifying existing knowledge and gaining new information about potential options also is included. In the synthesis phase, individuals narrow down and further develop the options they are considering.

In the valuing phase, individuals assess the costs and benefits of each remaining alternative. This task involves prioritizing the alternatives, as well as selecting a tentative primary and secondary choice. In the execution phase, individuals create and commit to a plan of action for accomplishing their first choice. Upon completion of the execution phase, individuals return to the communication phase to determine whether the gap has been filled. The CASVE cycle is recursive in nature. Therefore, if the gap has not been removed and problems still exist, an individual will progress through the CASVE cycle again (Sampson et al., 2004).

Negative Thinking

Several studies have found that negative thoughts are related to career decision-making difficulties (Kleiman et al., 2004; Sampson, Peterson, Lenz, Reardon, & Saunders, 1996; Sampson et al., 2004). Kleiman et al. (2004) examined the relationship between dysfunctional thoughts and an individual’s degree of career decidedness in a sample of 192 college students enrolled in an undergraduate career-planning course. The researchers found that dysfunctional thinking during the decision-making process can negatively influence rational decisions. Assessing for dysfunctional career thoughts and working with individuals to reduce negative career thinking can have a positive impact on the knowledge and decision-making skills domains of the pyramid of information processing. More importantly, utilizing a theoretical approach can provide a structure in which to address the needs of student veterans.

Needs Assessment Survey

In order to address the needs of student veterans, counselors must first assess what these needs are. Student veterans offer a unique subset of our veteran population in that they operate within an educational environment while possessing diverse life experiences, and are therefore often unique in relation to their peers (Cook & Kim, 2009). Given the aforementioned employment difficulties for younger veterans (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014b), a need for career-focused interventions designed to assist this population is apparent.

While various supportive services for veterans are available, determining an appropriate allocation of resources and time to address the needs of this population can enhance the quality of services. To match intervention with need, the authors created a needs survey designed to inform the development of a theoretically based career intervention, the purpose of which is assisting student veterans in developing skills in career decision making and problem solving.

Sample

The sample for this needs assessment was collected from a sample of student veterans attending a large southeastern university (n = 92). Currently, this university has approximately 317 student veterans enrolled and receiving educational benefits through either the Montgomery GI Bill or post-9/11 GI Bill. This means of identifying veterans is imperfect, as there may be student veterans attending the university who do not utilize educational benefits. However, this is a common method of identifying veterans within university settings (University of Arizona, 2007). The participants were asked to complete the needs survey by both the university veterans association and the veterans benefit officer. Both social media and e-mail were used to elicit participation.

All 317 identified members of the population receiving education benefits were provided the opportunity to respond to the survey, via both an e-mail request with the electronic survey attached and a post on the student veteran organization’s social media Web page. A total of 92 (29%) completed surveys were collected. Of the 92 respondents, a majority identified as graduate students (47; 51%). The remaining respondents indicated their classifications as undergraduate students with the classifications of junior (25; 23%), senior (18; 20%), and sophomore (2; 2%). No students classified as freshmen responded to the survey.

Instrument

The research team constructed the Veterans Needs Survey after examining the common career-development needs of both veterans and nonveterans encountered in the university’s career center. The instrument was created via a Qualtrics survey management system and attached to an electronic communication addressed to the potential respondents, as well as embedded in a social media thread of the university’s student veteran organization. The measure inquired about whether respondents had heard of the university career center; whether they had previously visited the university career center; what they would like to learn more about related to the career-development process; what modalities of treatment they were most interested in attending (e.g., group counseling, workshop series); how likely they were to attend the option indicated; education status; major/field of study; additional comments related to their career development; and an opportunity to participate in an intervention (an e-mail address was requested). The authors did not collect significant demographic information, instead focusing on variables like utilization of services (e.g., contact with the career center) and students’ academic classification, as these factors appear directly connected with career-development concerns.

Results

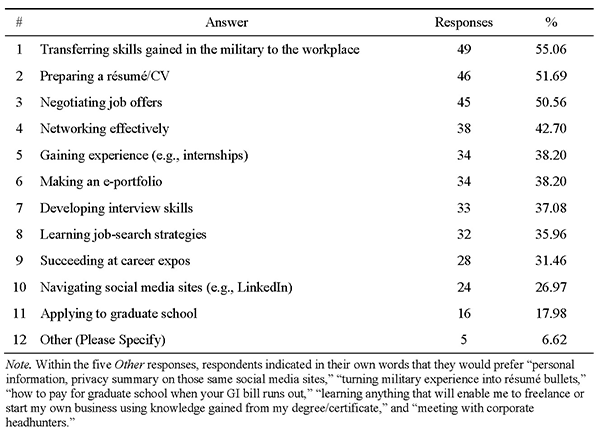

The survey examined utilization and perceptions of career-development needs. The majority of respondents (80; 87%) indicated that they had heard of the career center, but a smaller number indicated actually visiting the career center (66; 73%). The question pertaining to perceived career-development needs provided a multiple-option response set in which one could indicate several options. The most frequently indicated response was transferring skills gained in the military to the workplace (49; 55.06%). The second most frequently indicated response was preparing a résumé/CV (46; 51.69%), followed by negotiating a job offer (45; 50.56%). Table 1 provides a detailed description of additional responses regarding the career-development process.

A significant majority (54; 61%) indicated that they would be most interested in attending a group format, and fewer respondents selected the workshop series as their first choice (24; 27%). Respondents indicating the other category specified that they would attend career fairs, take advantage of individual counseling, and utilize online workshops. Following up on the previous question, one item inquired how likely a respondent would be to attend the option indicated. The most frequently indicated response was somewhat likely (42; 47%) followed by very likely (34; 38%) with unlikely (14; 16%) being the least frequently indicated response. The majors/fields of study with a significant number of responses were law (9), business-related (undergraduate and graduate; 9), social work (7), and criminology (8).

Participants provided diverse general comments related to their career development. One student veteran stated, “I have an associates [sic] degree in Laboratory Technology from the military and would also like assistance building a résumé trying to find employment now.” Another shared, “As a distance learner, it is possible to feel out of reach when it comes to on-campus resources. But, I know we can overcome that. I may be a combat disabled veteran. But, I won’t let disabilities stop my self-actualization quest.”

The information obtained from the needs survey can be utilized to inform an intervention designed to assist student veterans in their career development, which will provide a grounded approach in addressing these issues. The following section offers a proposal for meeting student veteran needs with a career-development intervention.

Table 1

Perceived Career-Development Needs

A Proposed Theoretically Based Career Intervention

Based upon the CIP theoretical framework (Sampson et al., 2004) and the feedback received from the needs assessment, psychoeducational groups will be conducted in order to achieve the following goals: expanding student veteran self-knowledge and career options through the CIP approach, exploring transferable skills gained through military experiences, gaining knowledge of resources that can assist student veterans in the job search and application processes, and identifying and decreasing negative metacognitions and dysfunctional career thoughts.

The psychoeducational group will meet once a week for 4 weeks. The group is open to all student veteran members attending the university through a campus-wide recruitment effort. Considering the tight connections between each CIP component, the group will be conducted in a closed-group format. The group facilitators will be graduate students pursuing doctoral degrees in counseling psychology or school psychology, and/or master’s students studying career counseling.

The group activities will center on the student veterans’ needs obtained through the needs assessment survey and the CIP components that have been proposed to serve the needs of veterans (Bullock et al., 2009; Clemens & Milsom, 2008). The structure of the psychoeducational group is based on the CIP model and five stages of the CASVE cycle diagram: communication, analysis, synthesis, valuing, and execution.

During the first session (communication), the group leader(s) will help to identify gaps between where group members are currently and where they aspire to be. Group members’ baseline information will be obtained by completing the Career Thoughts Inventory (CTI; Sampson, Peterson, Lenz, Reardon, & Saunders, 1996/1998) and My Vocational Situation (MVS; Holland, Daiger, & Power, 1991). The group leader(s) will explain the CIP Pyramid, CASVE Cycle Diagram, Self-Directed Search (SDS; Holland 1985) and assessment procedures. Group members will have an opportunity to interact with each other and complete one section of the Guide to Good Decision Making (Sampson, Peterson, Lenz, & Reardon, 1992). As a part of the homework assignment listed on the Individual Learning Plan (ILP), a document designed to identify career-related goals and associated action steps, group members will complete the SDS, and bring a copy of their current résumé to the next session.

During the second session (analysis/synthesis), the group leader(s) will help the student veterans examine and identify their interests, values, and skills (including transferable skills). The group leader(s) will assist group members in interpreting their SDS results, and examine any potential dysfunctional career thoughts that may be impacting group members’ career choices and decision-making abilities. To expand their career options, group members will be exposed to career-related resources such as the Occupational Outlook Handbook (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014c) and the Military Crosswalk Search via O*Net Online (National Center for O*NET Development, n.d.). In addition to gaining self-knowledge and occupational information in the analysis process, group members will have opportunities to practice synthesis skills. Group members will improve their résumé-writing skills through practice and feedback from peers and the group leader(s). Exploring and highlighting transferable skills is another important component. As part of their assignment listed on the ILP, group members will enhance their career networking skills by accessing supportive professionals via an alumni network and the Student Veterans Association, among other resources. Group members will also conduct an informational interview to gain firsthand experiences for their chosen career options. They will bring updated versions of their résumés and cover letters for the next session to obtain feedback from the group.

During the third session (valuing and execution), group members will present reflections on their informational interviews and provide feedback on their peers’ résumés and cover letters. In addition, group members will be exposed to various career resources such as VetJobs (VetJobs, Inc., 2014), Feds Hire Vets (U.S. Office of Personnel Management, n.d.), Job-hunt.org (NETability, Inc., 2014), the Riley Guide (Riley Guide, 2014), and the National Resource Directory (U.S. Departments of Defense, Labor and Veterans Affairs, n.d.). The group leader(s) will explain the “elevator speech” exercise and ask group members to practice this exercise in order to maximize their interview skill development. The group will also enhance members’ ability to use social networking to optimize their job search and applications. All activities aim to help members weigh their career options and execute their career decision making through careful planning. The group leader(s) will encourage members to initiate career networking and start exploring job and career opportunities.

During the last session (communication), group members will share what they originally included in their ILPs and what they have achieved, and offer suggestions and feedback to one another. They will retake the CTI and MVS and compare their new and initial results. Group leaders will help group members examine whether the gaps identified at the communication stage have successfully been closed, and suggest further measures to close gaps if necessary.

Discussion

The information gathered from the needs survey provides a thorough description of student veterans’ career-development needs. Interventions designed to support this population by determining appropriate interventions are often constructed using anecdotal information rather than objective needs. Student veteran responses to the survey indicate that veterans are concerned about transitioning their military experiences to civilian employment opportunities. In addition, student veterans appear to desire assistance with practical elements of the career-development process such as creating a résumé, negotiating a job offer, and networking. The purpose of this study is to develop a theoretically based intervention, and the study offers a framework in which to create effective career-development interventions for student veteran population.

Student veterans appear to engage in a wide array of academic programs, with a significant portion of veterans selecting majors within the realm of business, law, sociology, social work and criminology. These survey results provide a snapshot of the majors/fields of study that student veterans seem to gravitate toward. These preferences could be attributed to the hierarchical and meritocratic nature of some of these fields, which are somewhat analogous to the culture of the military.

Responses to the survey also provided a glimpse into the preferred modality of receiving career-related assistance. Oftentimes, military transition programs are designed to serve a large number of people, using seminar or workshop modalities in which to provide information. Student veterans indicated a strong preference for a smaller group counseling format that would provide more individual career-development support.

An additional important consideration for future interventions is the high number of respondents who identified themselves as distance learners in the needs assessment (some of them may have been on active service, whereas others were simply enrolled in the university from a remote location). Given the technological capabilities that allow online learning environments, it is reasonable that student veterans could utilize e-learning opportunities. Designing online interventions could be helpful in determining appropriate modalities by which to deliver services.

The student veterans’ comments and responses regarding their desired areas of focus for career development indicate a preference for a balanced approach of skill development. Ensuring that interventions focus on practical elements such as résumés and networking skill development, while also addressing broader topics such as transitioning from the military to the civilian workforce, appears to be a desired method for addressing the career-development needs of student veterans.

Limitations

The needs survey is limited in generalizability, as the results were collected from one educational institution, confining interpretations to the student veterans in this institution. Despite this limitation, the career-development concerns of student veterans provide a snapshot of the needs of this unique subset of the veteran population. Given the paucity of research in this area, it seemed necessary to facilitate an in-depth examination of this population’s career-development concerns, allowing the development of an informed intervention and establishing replicable protocol for future needs surveys.

The low response rate to the online survey also limits the application of findings. Though the response rate of 29% may be considered reasonable for an online assessment, having a large portion of the sample disregard the assessment presents a gap in fully substantiated information on this topic. Developing methods for collecting more information would enhance the validity of the data.

Finally, the high rate of graduate students who responded to the survey presents a challenge in applying the results to a primarily undergraduate institution. While there may be analogous experiences between graduate and undergraduate students, specific aspects of undergraduate student veterans’ career development may need additional evaluation.

Implications for Practice and Research

In this needs assessment, collaborative efforts between career services professionals at the institution and the university veterans’ center resulted in informative data on the career concerns of student veterans. Co-sponsored initiatives targeting these expressed needs could increase the number of student veterans impacted by career services. Survey respondents, along with group or workshop participants, could be recruited to provide feedback as part of a career-development focus group, further informing research and application for student veterans’ career concerns. Survey results could also be useful for marketing career services to student veterans. In addition, career centers or university libraries could acquire career resources such as books and print materials on topics that survey respondents considered desirable, especially those specifically tailored for veterans.

At the larger university level, major data on their students’ career-development concerns would be valuable information for college and department academic advisors and other university stakeholders. Career center staff members focus on various academic units as part of their career outreach, but further research regarding the unique career concerns of student veterans in specific majors could allow career center liaisons to impact veterans more effectively in their designated areas. As previously stated, since the survey was conducted at one higher education institution, duplicating the needs survey across a larger sample of colleges and universities would provide additional data sets for analysis, as well as broader application possibilities. Survey data could also be applied outside the institution to identify the most optimal partnerships in order to meet the comprehensive needs of student veterans. For example, career counselors might collaborate with mental health professionals, school counselors, and rehabilitation professionals to identify challenges and provide resources in order to maximize development for student veterans.

The results of this survey also support future research on the efficacy and suitability of online career-development options. There are many online programs designed to provide veterans the opportunity to pursue their education while in active duty. While the convenience of remote educational options for a mobile population is understood, ensuring that universities also provide career-development resources to distance learners is an important consideration in addressing the needs of veterans. Career-development opportunities such as webinars and online workshops offer the flexibility of distance learning. For example, online formats could provide veterans an opportunity to participate in such workshops collaboratively. Possible areas of research would include effective use of distance learning for veterans and comparative benefits and costs of in-person versus distance formats.

Based on the information collected, in future needs surveys, adjusting the survey items to detail reasons for certain item selections could allow greater understanding of both the responses and student veterans’ career thinking in general. Resulting career interventions would provide additional opportunities for further research to investigate aspects of career decision making and CIP theory, including relationships between student veterans’ self-knowledge, options knowledge, decision-making skills and metacognitions.

Conclusion

While veterans’ needs receive significant attention, programs are often created based on anecdotal and intuitive information. Developing needs assessments to solicit veterans’ perceptions of career development can inform interventions. Specifically regarding career development, utilizing a theoretically based, researched approach offers a framework to guide practice and research. Ongoing assessment of needs and services that utilizes established approaches will ensure quality services for those who have sacrificed greatly in service of their country.

References

Bullock, E. E., Braud, J., Andrews, L., & Phillips, J. (2009). Career concerns of unemployed U.S. war veterans: Suggestions from a Cognitive Information Processing approach. Journal of Employment Counseling, 46, 171–181. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.2009.tb00080.x

Buzzetta, M., & Rowe, S. (2012, November 1). Today’s veterans: Using Cognitive Information Processing (CIP) approach to build upon their career dreams. Career Convergence Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.ncda.org/aws/NCDA/pt/sd/news_article/66290/_self/layout_details/false

Clemens, E. V., & Milsom, A. S. (2008). Enlisted service members’ transition into the civilian world of work: A cognitive information processing approach. The Career Development Quarterly, 56, 246–256. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2008.tb00039.x

Cook, B. J., & Kim, Y. (2009). From soldier to student: Easing the transition of service members on campus. Retrieved from http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Documents/From-Soldier-to-Student-Easing-the-Transition-of-Service-Members-on-Campus.pdf

Engels, D. W., & Harris, H. L. (2002). Career counseling with military personnel and their dependents. In S. G. Niles (Ed.), Adult career development: Concepts, issues, and practices (3rd ed., pp. 253–266). Tulsa, OK: National Career Development Association.

Green, L., & Hayden, S. (2013). Supporting student veterans: Current landscape and future directions. Journal of Military and Government Counseling, 1, 89–100.

Hayden, S., Green, L., & Dorsett, K. (in press). Perseverance and progress: Career counseling for military personnel with traumatic brain injury. VISTAS. Retrieved from http://www.counselingoutfitters.com/vistas/vistas_2013_TOC-QR3-section_01.htm

Holland, J. L. (1985). Making Vocational Choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Holland, J. L., Daiger, D. C., & Power, P. G. (1991). My Vocational Situation. Mountain View, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Kleiman, T., Gati, I., Peterson, G., Sampson, J., Reardon, R., & Lenz, J. (2004). Dysfunctional

thinking and difficulties in career decision making. Journal of Career Assessment, 12,

312–331. doi:10.1177/1069072704266673

National Center for O*NET Development. (n.d.). Military crosswalk search [Database]. O*NET Online. Retrieved from http://www.onetonline.org/crosswalk/MOC/

NETability, Inc. (2014). How to succeed in your job search today. Job-hunt.org. Retrieved from http://www.job-hunt.org

Phillips, J., Braud, J., Andrews, L., & Bullock, E. E. (2007, November 1). Bridging the gap from job to career for U.S. veterans. Career Convergence Magazine. Retrieved from

http://associationdatabase.com/aws/NCDA/pt/sd/news_article/5412/_PARENT/layout_details_cc/false

Reardon, R. C., Lenz, J. G., Peterson, G. W., & Sampson, J. P., Jr. (2012). Career development and planning: A comprehensive approach (4th ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing.

Riley Guide. (2014). The Riley Guide. Retrieved from http://www.rileyguide.com/

Sampson, J. P., Jr., Peterson, G. W., Lenz, J. G., & Reardon, R. C. (1992). A cognitive approach

to career services: Translating concepts into practice. The Career Development Quarterly, 41, 67–74.

Sampson, J. P., Jr., Peterson, G. W., Lenz, J. G., Reardon, R. C., & Saunders, D. E. (1996). Career Thoughts Inventory: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Sampson, J. P., Jr., Peterson, G. W., Lenz, J. G., Reardon, R. C., & Saunders, D. E. (1998). The design and use of a measure of dysfunctional career thoughts among adults, college students, and high school, students: The Career Thoughts Inventory. Journal of Career Assessment, 6, 115–134. doi:10.1177/106907279800600201

Sampson, J. P., Jr., Reardon, R. C., Peterson, G. W., & Lenz, J. G. (2004). Career counseling & services: A cognitive information processing approach. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Sander, L. (2012, July). Colleges expand services for veterans, but lag in educating faculty on veterans’ needs. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://chronicle.com/

Sander, L. (2013, January). Veterans tell elite colleges: ‘We Belong’. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://chronicle.com/

Stein-McCormick, C., Osborn, D. S., Hayden, S. C. W., & Van Hoose, D. (2013). Career development for transitioning veterans. Broken Arrow, OK: National Career Development Association.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2014a). Employment situation of veterans – 2012 [News release]. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/vet.pdf

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2014b). Table A-5. Employment status of the civilian population 18 years and over by veteran status, period of service, and sex, not seasonally adjusted [Economic news release]. Retrieved from http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/print.pl/news.release/empsit.t05.htm

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2014c). 2014–2015 Occupational outlook handbook. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/ooh/

U.S. Departments of Defense, Labor and Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). National resource directory. Retrieved from https://www.nrd.gov/

U.S. Office of Personnel Management. (n.d.). Feds hire vets. Retrieved from http://www.fedshirevets.gov/Index.aspx

University of Arizona. (2007). Student veteran needs assessment survey. Retrieved from https://studentaffairs.arizona.edu/assessment/documents/VETS_Needs7-2012FINAL.pdf

VetJobs, Inc. (2014). VetJobs: Veterans make the best employees. Retrieved from https://www.vetjobs.com/

Seth Hayden, NCC, is the Program Director of Career Advising, Counseling and Programming at Florida State University. Kathy Ledwith, NCC, is the Assistant Director for Career Counseling, Advising and Programming at Florida State University. Shengli Dong is an Assistant Professor at Florida State University. Mary Buzzetta, NCC, is a doctoral student at Florida State University. Correspondence can be addressed to Seth Hayden, 100 S. Woodward Avenue, Tallahassee, FL 32308, scwhayden@fsu.edu.