Feb 26, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 1

Diane M. Stutey, Jenny L. Cureton, Kim Severn, Matthew Fink

Recently, a mnemonic device, SHORES, was created for counselors to utilize with clients with suicidal ideation. The acronym of SHORES stands for Skills and strategies for coping (S); Hope (H); Objections (O); Reasons to live and Restricted means (R); Engaged care (E); and Support (S). In this manuscript, SHORES is introduced as a way for school counselors to address protective factors against suicide. In addition, the authors review the literature on comprehensive school suicide prevention and suicide protective factors; describe the relevance of a suicide protective factors mnemonic that school counselors can use; and illustrate the mnemonic’s application in classroom guidance, small-group, and individual settings.

Keywords: suicide prevention, protective factors, school counselors, SHORES, mnemonic

Rates of youth suicide have increased tremendously in the last decade. A report by the National Center for Health Statistics in 2019 indicated that suicide rates among American youth ages 10–24 increased 56% from 2007 to 2017, making it the second leading cause of death in this age group; during this same time period, the rate almost tripled for those ages 10–14 (Curtin & Heron, 2019). Additionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2017) reported that suicide is now the ninth leading cause of death for children ages 5–11.

The suicide rates for children as young as 5 can seem alarming and impact school counselors at all grade levels. Sheftall et al. (2016) stated that children who died by suicide in this younger age range were frequently diagnosed with a mental health disorder. In children, this diagnosis was usually attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity, and in young adolescents the diagnosis was most often depression or dysthymia. Researchers have also found that certain risk factors, such as childhood trauma, bullying, and academic pressure, can increase suicidal risk for youth (Cha et al., 2018; Jobes et al., 2019; Lanzillo et al., 2018).

Researchers agree that early prevention and intervention is essential to reduce youth suicides

(Cha et al., 2018; Lanzillo et al., 2018; Sheftall et al., 2016). Similarly, postvention efforts, or crisis response strategies following a student’s suicide, can lessen school suicide contagion and support future prevention efforts (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention [AFSP] et al., 2019). In this article, we review the literature on youth suicide and efforts to address it including leveraging protective factors, and we introduce the relevance of a suicide protective factors mnemonic that school counselors can apply in classroom guidance, small-group, and individual settings (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2019).

School Suicide Prevention

Curtin and Heron (2019) called for proactive efforts to help address the rising statistics for youth suicide, and schools are a natural place for prevention, intervention, and postvention to occur. Students spend the majority of their waking hours at school and have frequent contact with teachers, counselors, administrators, and peers. School efforts to address suicide risk must include these stakeholders, as well as parents and community members (Ward & Odegard, 2011).

A suicide prevention effort is a strategy intended to reduce the chance of suicide and/or possible harm caused by suicide (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2012). Best practice for suicide prevention in schools includes training all stakeholders, including students (Wyman et al., 2010). This training, frequently referred to as gatekeeper training, should include information about suicide warning signs and risk factors, as well as suicide protective factors, such as seeking help and having social connections. The World Health Organization’s (WHO; 2006) booklet for counselors on suicide prevention lists several suicide warning signs, including ones with relevance to school-age youth, such as decreased school achievement, changed sleeping and eating, preoccupation with death, sudden promiscuity, or reprieve from depression (pp. 5–6). Another important component of school suicide prevention is training and practice on how to help a student who exhibits these and/or other suicidal warning signs (AFSP et al., 2019). Institutional efforts, such as forming crisis teams (AFSP et al., 2019), and anti-bullying programs can also contribute to school suicide prevention efforts (HHS, 2012).

Other school prevention efforts involve small-group and whole classroom lessons on resiliency, coping skills, executive functioning skills, and help-seeking behavior (Sheftall et al., 2016). Many programs exist and are beneficial at elementary, middle, and high school levels. The Suicide Prevention Resource Center (SPRC; 2019a) listed many options: Signs of Suicide, More Than Sad, Sources of Strength, and Kognito. Of these examples, only Signs of Suicide contains training for warning signs, suicide risk factors, and suicide protective factors. Some suicide prevention programs are state and population specific, but all include the information needed to help stakeholders to know the risks and signs, and to have a plan on how to help youth with suicidal thoughts. Talking about suicide prevention with all stakeholders promotes increased help-seeking behavior in children and adolescents (Wyman et al., 2010).

School Suicide Intervention

Suicide is an ongoing issue that many school counselors handle via intervention efforts. A suicide intervention effort is a strategy to change the course of an existing circumstance or risk trajectory for suicide (HHS, 2012). School counselors are a natural choice for helping to implement suicide prevention and intervention programs, as they often have training on working with students at risk for suicidal ideation (Gallo, 2018). Additionally, school counselors are ethically responsible to help create a “safe school environment . . . free from abuse, bullying, harassment and other forms of violence” and to “advocate for and collaborate with students to ensure students remain safe at home and at school” (ASCA, 2016, pp. 1, 4). One key component of school suicide intervention is suicide risk assessment. Gallo (2018) researched 200 high school counselors representing 43 states and found that 95% agreed it was their role to assess for suicidal risk, and 50.5% were conducting one or more suicide risk assessments each month. Other aspects of intervention include potential involvement of administrators, parents, and emergency or law enforcement services; referral to outside health care providers; and safety planning, including lethal means counseling (AFSP et al., 2019). School and other counselors are also involved in ongoing check-ins with students, re-entry planning after a mental health crisis, and responses to in-school and out-of-school suicide attempts.

School Suicide Postvention

Suicide postvention involves attending to those “affected in the aftermath of a suicide attempt or suicide death” (HHS, 2012, p. 141). ASCA, in collaboration with AFSP, the Trevor Project, and the National Association of School Psychologists, released the Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention that outlines policies and practices for districts, schools, and school professionals to protect student health and safety (AFSP et al., 2019). The model policy addresses postvention by summarizing a 7-step action plan involving school counselors and other professionals: 1) get the facts, 2) assess the situation, 3) share information, 4) avoid suicide contagion, 5) initiate support services, 6) develop memorial plans, and 7) postvention as prevention (pp. 11–13). The latest edition of a suicide postvention toolkit for schools (SPRC, 2019a) highlighted counselors’ collaborative work for crisis response and suicide contagion; how they help students with coping and memorialization; and their involvement with community, media, and social media.

Addressing factors that protect against suicide is an important component of school district policies to combat suicide (AFSP et al., 2019) and of comprehensive school suicide prevention (Granello & Zyromski, 2018). Leveraging suicide protective factors is one way for school counselors to fulfill professional obligations and recommendations concerning student suicide risk. What remains unclear from the literature is how school counselors explore and enhance protective factors in their suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention efforts.

Suicide Risk and Protective Factors

The SPRC (2019b) defined suicide risk factors as “characteristics that make it more likely that individuals will consider, attempt, or die by suicide” and protective factors as those which make such events less likely (p. 1). High suicide risk involves a combination of risk factors. Examples of suicide risk factors include a prior attempt, mood disorders, alcohol abuse, and access to lethal means, whereas examples of suicide protective factors include connectedness, health care availability, and coping ability (SPRC, 2019b). Protective factors “are considered insulators against suicide,” which can “counterbalance the extreme stress of life events” (WHO, 2006, p. 3). Both risk and protective factors have varying levels of significance depending on the individual and their community (SPRC, 2019b).

Guidance from multiple sources stresses the salience of incorporating attention to suicide risk and protective factors into school counseling. The AFSP et al. (2019) Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention notes risk and protective factors as crucial content in staff development and youth suicide prevention programming. In addition to the risk factors named above, the policy names high-risk groups, such as students who are involved in juvenile or child welfare systems; those who have experienced homelessness, bullying, or suicide loss; those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning; or those who are American Indians/Alaska Natives (AFSP et al., 2019).

School counselors should know suicide protective factors that are specific to school settings and to the ages of students that they serve. The Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention (AFSP et al., 2019) also highlights the role that accepting parents and positive connections within social institutions can play in a student’s resiliency. Despite suicide prevention policy guidelines, numerous structured programs, and growing research on youth suicide protective factors, very little guidance is offered on practical methods for school counselors to address students’ suicide protective factors. The purpose of this manuscript is to introduce to school counselors a recently published, research-based mnemonic—SHORES (Cureton & Fink, 2019). The acronym of SHORES stands for Skills and strategies for coping (S); Hope (H); Objections (O); Reasons to live and Restricted means (R); Engaged care (E); and Support (S). SHORES equips school counselors with a promising tool to guide suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention via direct and indirect school counseling services.

SHORES

Cureton and Fink (2019) created a mnemonic device called SHORES for counselors to utilize when working with clients. SHORES represents protective factors against suicide and the letters in the acronym were carefully selected based on support in the literature.

Figure 1

Cureton, J. L., & Fink, M. (2019). SHORES: A practical mnemonic for suicide protective factors. Journal of Counseling &

Development, 97(3), 325–335.

In the following sections, the authors define each part of the acronym and discuss how school counselors may apply SHORES with students. After discussing each of the protective factors in the mnemonic, we present a case example to demonstrate how school counselors may implement the SHORES tool with students in their school.

S: Skills and Strategies for Coping

First, school counselors can explore with students what skills and strategies for coping (S) with adversity they might already have in place, work to strengthen these, and also foster development of new coping skills and strategies. Cureton and Fink (2019) shared that some of the skills and strategies for coping that counter thoughts of suicide include emotional regulation, adaptive thinking, and engaging in one’s interests (Berk et al., 2004; Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002; Law et al., 2015). For youth, such engagement includes academic and non-academic pursuits (Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp, 2014). School counselors often meet with students to discuss coping strategies and stress management; therefore, this step can easily be incorporated into working with students demonstrating signs of stress or even suicidal ideation.

Mindfulness skills and strategies may be particularly impactful for schools to incorporate. Research findings support the importance of a student’s emotional regulation skills, as dysregulation is associated with children’s suicidal thoughts (Wyman et al., 2009) and adolescents’ suicide attempts (Pisani et al., 2013). There is substantial research evidence on the positive effect of mindfulness interventions in children and adolescents, particularly for decreasing depression and anxiety (Dunning et al., 2019). Flook et al. (2010) used a school-based mindful awareness program with elementary school children that incorporated sitting meditation; a brief visualized body scan; and games for sensory awareness, attentional regulation, awareness of others, and awareness of the space around them. They found improvements in elementary school children’s metacognition, behavioral regulation, and executive control. Broderick and Jennings (2012) posited that mindfulness practice is an effective coping strategy for adolescents because it “offers the opportunity to develop hardiness in the face of uncomfortable feelings that otherwise might provoke a behavioral response that may be harmful to self and others” (p. 120). Teaching or practicing mindfulness with students might include helping them with body awareness, understanding and working with thoughts and feelings, and reducing harmful self-judgements while increasing positive emotions.

H: Hope

Cureton and Fink (2019) suggested that hope (H) can protect against suicide because it may counterbalance negative emotions and cognitions. Studies have demonstrated that hope can help to safeguard the influence of hopelessness on suicidal ideation and that hope could, in turn, relieve a person’s feelings of being a burden and not belonging (Davidson et al., 2009; Huen et al., 2015). Researchers have found that adolescents with hope have lower suicide risk (Wai et al., 2014) and that hope moderates depression and suicidal ideation, even among adolescents who experienced childhood neglect (Kwok & Gu, 2019).

Furthermore, Tucker and colleagues (2013) discovered that establishing hope can also decrease some of the adverse impacts of rumination on suicidal ideation. Classroom guidance lessons could help school counselors to assess if there are individual students who seem to lack hope; these students might be good candidates for small-group or individual counseling. If school counselors wanted to implement a schoolwide comprehensive program, they might look at implementing Hope Squads. Over 300 schools in Utah have implemented peer-to-peer suicide prevention programs called Hope Squads, which work to instill hope and create a school culture of connectedness and belonging (Wright-Berryman et al., 2019). Hope Squads could also be utilized in the final stage of SHORES as a source of Support (S).

Another way that researchers found to decrease suicidal ideation was building hope through goal-setting (Lapierre et al., 2007). School counselors are in a prime position to help with goal-setting and could incorporate the topic of hope when helping students to set goals. One evidence-based intervention that can be utilized by school counselors to help students with goal-setting is Student Success Skills. School counselors teaching the Student Success Skills lessons not only encourage students to set wellness goals, but also teach attitudes and approaches that will help students socially and to reach their academic potential (Villares et al., 2011).

O: Objections

Cureton and Fink (2019) included another supported protective factor: moral or cultural objections (O) to suicide. Researchers have found that individuals with fewer moral objections to suicide were more likely to attempt suicide (Lizardi et al., 2008), while those with a religious objection may have fewer attempts (Lawrence et al., 2016). Ibrahim and colleagues (2019) discovered that the role of religious and existential well-being was a protective factor for suicidal ideation with adolescents.

Research shows that school counselors feel ready to address spirituality with students, and at least one suicide prevention program could help with that focus. Smith-Augustine (2011) found that 86% of the 44 school counselors and school counseling interns who participated in a descriptive study had spirituality and religious issues arise with students, and 88% reported they felt comfortable addressing these issues with students. Although the focus is not on religion, this topic may come up when discussing spirituality, and school counselors working in public schools will want to be mindful of any restrictions from their district about discussing religion and/or spirituality with students. One evidence-based suicide prevention program that addresses spirituality is Sources of Strength (2017).

Sources of Strength has been used primarily in high school settings, but guidance for its application in elementary schools is also available. While participating in Sources of Strength, youth are asked to reflect on and discuss a range of spiritual practices, ways they are thankful, and how they view themselves as “connected to something bigger” (Sources of Strength, 2017). Wyman and colleagues (2010) discovered that participating in Sources of Strength helped increase students’ perceptions of connectedness at school, in particular with adults in the building. Implementing this program would allow school counselors to seek out those students at risk and have further individual conversations and tailor any necessary interventions to that student’s cultural and religious/spiritual beliefs. School counselors could also refer students and families to therapists outside of the school setting who may be able to further explore spiritual and cultural beliefs and resources.

More research is needed about how cultural objections to suicide impact youth. For instance, there is a longstanding belief that the view in the Black community of suicide as “a White thing” (Early & Akers, 1993) acts as a suicide protective factor. But in the wake of rising suicide rates among Black youth, Walker (2020) challenged this notion, arguing that Black youth are at risk for suicide because mental health stigmas in their communities result in them keeping their distress to themselves. Other researchers (Sharma & Pumariega, 2018) have echoed the concern that guilt and/or shame about suicidal ideation may result in isolation in youth of color, including those from Black, Latinx, Asian, and other cultural groups. Another cultural objection in youth of color that may serve as a protective factor is culturally informed beliefs about death and the afterlife (Sharma & Pumariega, 2018). School counselors can focus on “normalizing suicidal ideation and acceptance of internal and external problematic events” (Murrell et al., 2014, p. 43) and on ways to include family members and other cultural representatives who are accepting of mental health issues in suicide-related conversations and programs with students of color.

R: Reasons to Live and Restricted Means

A fourth protective factor refers to two areas: reasons to live and restricted means (R). Reasons for living (RFL) are considered drives one might have for staying alive when contemplating suicide (Linehan et al., 1983). Bakhiyi et al. (2016) established in a systematic review of research literature that RFL serve as protective factors against suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adolescents and adults. In a study with over 1,000 Chinese adolescents, the correlation between entrapment and suicidal ideation was moderated by RFL; adolescents with a higher RFL score had lower suicidal ideation even when experiencing high levels of entrapment (Ren et al., 2019). School counselors might consider giving students the RFL Inventory when presenting on suicide prevention or assessing for suicidal ideation, either the adolescent version (Osman et al., 1998) or the brief adolescent version (Osman et al., 1996). School counselors can also heighten students’ awareness of their RFL by asking them what or whom they currently cherish most or would miss or worry about if they suddenly went away.

The second part of this protective factor is restriction (R) of lethal suicide means, such as firearms, poisons, and medications (Cureton & Fink, 2019). There is evidence to support that restriction of means is effective for decreasing suicide (Barber & Miller, 2014; Kolves & Leo, 2017; Yip et al., 2012). For children and adolescents ages 10–19, the most frequent suicide method was hanging, followed by poisoning by pesticides for females and firearms for males. These findings were based on 86,280 suicide cases from 101 countries from 2000–2009 (Kolves & Leo, 2017).

Given this information, it is important for school counselors to not only assess for lethal weapons access but also to inquire about students’ access to and awareness of how everyday items might be used to attempt suicide. Although it may be impossible to restrict all means that could be utilized for hanging or poisoning, school counselors can discuss with guardians various ways to reduce access to these means and provide more supervision for any youth exhibiting thoughts of suicide. Kolves and Leo (2017) also discussed the high number of youth who learn about ways to attempt suicide from media and the internet; therefore, restriction, reduction, and supervision of media and internet usage could also be something school counselors suggest to guardians.

E: Engaged Care

Another protective factor across populations is engagement (E) with caring professionals (Cureton & Fink, 2019; SPRC & Rodgers, 2011). School counselors often have hundreds of students on their caseloads, and this can become overwhelming, especially when dealing with crises such as suicide. At the same time, it is imperative that school counselors actively engage with students in a caring and supportive way. Often the school counselor might be the first person to intervene with a suicidal youth; Cureton and Fink (2019) emphasized the importance of the client being able to feel empathy and care from the counselor.

School counselors can view engaged care as an effective and collaborative approach for suicide prevention by working with students and families to leverage a variety of services. According to Ungar et al. (2019), “Students who reported high levels of connectedness to school also reported significantly lower rates of binge drinking, suicide attempts, and poor physical health compared to youth with low scores on school engagement” (p. 620). However, school counselors cannot be solely responsible for the ongoing engaged care of suicidal youth and will need to make referrals to outside counselors and/or physicians. Comprehensive engaged care might include mental health treatment and ongoing support and management from health care providers (Brown et al., 2005; Fleischmann et al., 2008; Linehan et al., 2006). Researchers found that comprehensive services that connect parents, schools, and communities result in decreased suicide attempts when compared to hospitalization for youth (Ougrin et al., 2013).

S: Support

The final element of the SHORES mnemonic emphasizes the importance of students having supportive (S) environments and relationships (Cureton & Fink, 2019). As mentioned above, the school counselor is only one source of support. The support and involvement of family can also serve as a protective factor (Jordan et al., 2012). Diamond et al. (2019) noted that “when adolescents view parents as sensitive, safe, and available, they are more likely to turn to parents for support that can buffer against common triggers for depressive feelings and suicide ideation” (p. 722).

In a study with 176 Malaysian adolescents, support from family and friends was found to be a protective factor against suicidal ideation (Ibrahim et al., 2019). Youth seek support for suicidal thoughts from peers more than from adults (Gould et al., 2009; Michelmore & Hindley, 2012; Wyman et al., 2010). Many suicide prevention programs, such as Hope Squads and Sources of Strength, are addressing the need for positive peer support by incorporating a peer-to-peer component into their interventions (Wright-Berryman et al., 2019; Wyman et al., 2010). Working to increase peer support along with support from school personnel, family, and community could be lifesaving for students contemplating suicide.

Case Example Applying SHORES

The SHORES tool is meant to be comprehensive and can be used in classroom guidance, small-group, and individual counseling. A case example is provided for how SHORES might be employed in a middle school setting; however, this example could be adapted to work with elementary or high school students.

A middle school counselor attended a training on SHORES and incorporates this into her comprehensive school counseling program. Each year when she delivers her lessons on suicide prevention, she brings the SHORES poster to each classroom and shares with her students about protective factors and ways to reach out and seek help if they have a concern about suicide.

During her second lesson on suicide prevention, the school counselor notices that one of her new seventh-grade students, Jesse, seems unusually withdrawn and disengaged. The counselor is reviewing skills and strategies for coping (S) and asks each of the students to write down three to four ways that they have learned to cope with stress. In addition, she asks them to report how well each of these strategies and coping skills are working for them on a scale of 1–10. When she collects the papers, she notices that Jesse has written only one coping skill: “Locking myself in my room away from all of the noise and the pain.” He then stated his coping skill “is a 10 and works great because people will just forget about me and I can disappear.”

The school counselor is concerned about these remarks and decides to bring Jesse in for an individual counseling session. As she is asking Jesse about whether he has hope (H) that things will get better, she learns that his father has been deployed for the past year, his mother recently went to prison, and his grandmother, who is his primary guardian, had a recent health scare. Jesse shares that he is afraid he is going to lose the people closest to him and he feels angry and alone. He states that being a “military brat” who is new to the school makes him feel even more isolated, and he worries what others will think if they find out his mom is a felon.

When the school counselor expresses her concern for his safety and asks if he has ever thought about killing himself, Jesse is adamant that suicide is against his religion and he would never do it. He adds, “My mom would break out of jail and whoop me if she even knew I had thoughts like that.” Although Jesse voices his objections (O) and denies any current suicidal ideation, the school counselor is concerned about his social–emotional well-being and suggests he join a small counseling group she has for students experiencing changes in their families. Jesse agrees to check it out and gets his grandmother to sign a permission form for him to attend.

During his first small counseling group, Jesse is quiet but does confide in the group what is happening in his family and that he has been feeling “depressed.” Two of the other group members share that they also feel depressed. The school counselor asks them to define what they mean by feeling depressed. As they answer, she creates a list on the board of their definitions: “I feel hopeless and alone,” “I sometimes don’t know why I’m even here,” and “Sometimes I want to just fall asleep and never wake up.”

After they explore these definitions and the underlying feelings, the school counselor writes “Reasons to Live” (R) on the whiteboard. She shares that sometimes when kids are feeling depressed or hopeless, it can be helpful to think about the different reasons that they want to live and things they enjoy about their lives. She gives the students time to come up with lists and keeps track of what each of the students came up with during the brainstorming session. Although all of the other students in the group are able to come up with four to five reasons to live, the school counselor notes that Jesse only came up with one: “I get to visit my mom each Sunday.”

The school counselor decides to keep Jesse a few minutes after group to check in on his safety again. First, she asks him if he had other reasons to live before he moved to his new school. Jesse said that he used to play soccer and that he loved it and it made him feel excited each day to be part of the team. The school counselor encourages Jesse to look into joining the school soccer team and offers to talk to the coach to see if this is a possibility.

When asked about suicidal ideation, he is again adamant that he would never do it, but he admits that a couple of years ago it did occur to him that he could take his grandfather’s gun and “end it all.” The school counselor discovers that Jesse’s grandmother kept her late husband’s gun at her house. After discussing this with Jesse and getting his consent to contact his grandmother, she decides to err on the side of caution and follow up. Jesse’s grandmother shares that she does not believe the gun even works anymore and that there are no bullets in the home. However, after speaking with the school counselor about restricting means (R) she decides to donate the gun to a local hunting club.

During this conversation, the grandmother also shares that she is concerned about Jesse, especially his lack of a male role model. She shares that Jesse’s biological father is active military and might only see Jesse once or twice a year, and his grandfather died when he was 2. The school counselor lets the grandmother know that she plans to contact the soccer coach (who is male) about getting Jesse to join the team. After some further conversation, the school counselor and grandmother agree that it would also be helpful for Jesse to have some ongoing engaged care (E) with a counselor outside of school. She also inquires about the family’s religious affiliation because Jesse has mentioned to her that this is important to him. The school counselor compiles a list of Christian male counselors and sends the list home at the end of the day.

Over the next few weeks, Jesse continues to attend the small group. He joined the soccer team and has also been working with an outside counselor. He reports he is feeling more hopeful, even though he still worries about his mom and misses her. The school counselor delivered a classroom lesson on sources of support (S) earlier that week and follows up with each of the students during group. Each member creates a list of current sources of support in their lives and shares it. The school counselor notes that Jesse’s paper is filled with names of people both in and outside of school; he has listed friends at school, on his soccer team, and in his neighborhood; his soccer coach; his mother and grandmother; a neighbor; two teachers; and both of his counselors.

As the small group begins to wrap up toward the end of the school year, the school counselor checks in with Jesse for an individual counseling session. She reminds him about their classroom lesson on skills and strategies for coping (S). Jesse shares that he and his other counselor have been working a lot on mindfulness and that he really enjoys this. With his counselor’s encouragement, Jesse has also pursued a few new interests such as joining a club for military kids and joining an after-school program. When the school counselor revisits the question about reasons to live (R), Jesse shares that he needs more than one sheet of paper to write down all the good things in his life. The school counselor follows up with Jesse’s grandmother to share these updates and promises to continue engaged care (E) with Jesse when he returns for eighth grade.

Implications for School Counseling Practice, Training, and Research

There are implications for the use of and research on this promising tool across counseling specialties, and we focus on school settings in alignment with the scope of this manuscript. Guidelines and recommendations for school counseling practice concerning suicide include attending to both risk factors and protective factors in work with students via comprehensive suicide prevention (ASCA, 2019; Granello & Zyromski, 2018). The SHORES tool has utility as a standard and recognizable component for a comprehensive school suicide prevention program; an adjunct to current interventions such as risk screening and safety planning measures; and a strengths-based framework for prevention, intervention, and postvention. Future research is necessary to explore these applications and their impact.

Although some school suicide prevention programs address suicide protective factors, SHORES offers school counselors a simple and practical tool that they can apply across behavioral elements of a comprehensive school counseling program (ASCA, 2019). This consistent integration may support deeper understanding and broader use among school counselors and other faculty/staff, as well as students. The case example illustrated how SHORES may be applied and useful in classroom, small-group, and individual settings.

School counselors may use interventions such as risk screening and safety planning, and SHORES can fill the gap for suicide protective factors in both. Most suicide risk screening focuses solely on risk factors or does not fully explore suicide protective factors (McGlothlin et al., 2016). The most well-known safety plan template (Stanley & Brown, 2012) does not include all elements of the SHORES mnemonic (Cureton & Fink, 2019). School counselors who add SHORES to their risk screens and safety plans will be engaging in more comprehensive and protective interventions for students who may be at risk for suicide.

SHORES derives from a positive, strengths-based mindset regarding suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention. School counselors can use the tool to guide wellness programming before a suicide by considering how current and future efforts serve to enhance each element of the acronym. School counselors are also key to suicide postvention or response following a suicide (AFSP & SPRC, 2018). A school’s suicide postvention plan has three aims (Fineran, 2012), and embedding SHORES into the plan may help minimize distress, reduce contagion, and ease the return to school routines in place before the crisis. Additionally, the SHORES tool addresses several of the assets and barriers for successful school reintegration after a student’s psychiatric hospitalization (Clemens et al., 2011), so potential applications also include postvention after suicide attempts.

There are also training implications for SHORES in counselor education and supervision and practitioner professional development. Although school counselors’ training on suicide appears to have improved over the last 25 years, Gallo (2018) found that only 50% of high school counselors felt adequately prepared to identify suicidal students and assess their risk. Counselors-in-training have described the specific need for more training on child and adolescent suicide assessment (Cureton &

Sheesley, 2017). Counselors-in-training (Cureton & Sheesley, 2017) and educators (Cureton et al., 2018)

have also acknowledged the benefit of practicing suicide response in supervised counseling (i.e., internship), as well as the potential to miss opportunities simply because no clients present with suicide risk during such experiences. However, a recent assessment (Cureton et al., 2018) demonstrated that the counselor education and supervision field has only modest readiness to address the issue of suicide in its master’s-level training programs, in part because of negative views about suicide as a topic that is too scary, serious, advanced, and taxing to cover in class (Cureton et al., in press).

The strengths-based, preventative nature of SHORES positions it as a tool that can be easily introduced in classroom role-plays as well as during conversations with students being served during practicum and internship. Reframing these conversations, and more broadly all suicide-related efforts in counseling, as both challenging and potentially positive and life-affirming may partially address the negative stigma within and beyond the counselor education and supervision field (Cureton et al., 2018, in press). Finally, adding SHORES to existing school personnel training offerings like those listed by the SPRC (2019a) would deepen professional development for school counselors and other staff, faculty, and administration.

Future Research

Despite the numerous possibilities to apply the SHORES tool in K–12 and other educational settings (Cureton & Fink, 2019), research is needed to establish its utility and effectiveness. Primary investigations include studies with school counselors who are considering adopting and implementing SHORES in their schools to understand perceptions of its apparent value and barriers to use. Evaluative studies about training offerings and investigations into memory recall of acronym components among school counselors would also aid in conceptualization of true functionality of the SHORES tool.

Research on students’ perceptions and outcomes studies are also needed. Students’ reactions to and generalized use of the SHORES tool would be beneficial in order to examine its appeal, as would those of families, teachers, and stakeholders. It is also important to explore how to be developmentally appropriate across grade levels. Finally, outcomes studies on SHORES for prevention, intervention, and postvention are necessary to determine its practical worth. For instance, a comparison between a school counseling department’s existing safety planning procedure and a SHORES-enhanced procedure would be valuable. Studies about SHORES and counselor self-efficacy to address suicide would also add to the literature.

Conclusion

As rates of youth suicide have increased in recent years, the need for school counselors to adopt tools to better assess suicide risk in their students has taken on more urgency. SHORES provides a strengths-based assessment tool that can be used by school counselors to quickly examine the protective factors that potentially mitigate against suicide in their students. Offering a comprehensive overview of existential, behavioral, and interpersonal factors that have been identified as bolstering defenses against suicidality, each letter of the SHORES acronym is rigorously supported by research and provides clear implications for the tool’s utility in K–12 settings. Given that only roughly half of school counselors feel sufficiently prepared to assess suicide risk in their students, the SHORES tool provides a practical resource for screening and safety planning. Even so, more research is needed to illustrate and verify the SHORES tool’s ease of use and adoption into other existing school-based approaches to addressing suicide in student populations.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, American School Counselor Association, National Association of School Psychologists, & The Trevor Project. (2019). Model school district policy on suicide prevention: Model language, commentary, and resources (2nd ed). https://afsp.org/model-school-policy-on-suicide-prevention

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, & Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2018). After a suicide: A toolkit for schools (2nd ed.). Education Development Center, Inc. https://sprc.org/resources-programs/after-suicide-toolkit-schools

American School Counselor Association. (2016). Ethical standards for school counselors. https://www.school

counselor.org/getmedia/f041cbd0-7004-47a5-ba01-3a5d657c6743/Ethical-Standards.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2019). ASCA school counselor professional standards & competencies.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/a8d59c2c-51de-4ec3-a565-a3235f3b93c3/SC-Competencies.pdf

Bakhiyi, C. L., Calati, R., Guillaume, S., & Courtet, P. (2016). Do reasons for living protect against suicidal thoughts and behaviors? A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77, 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.019

Barber, C. W., & Miller, M. J. (2014). Reducing a suicidal person’s access to lethal means of suicide: A research agenda. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3S2), S264–S272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.028

Berk, M. S., Henriques, G. R., Warman, D. M., Brown, G. K., & Beck, A. T. (2004). A cognitive therapy intervention for suicide attempters: An overview of the treatment and case examples. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 11(3), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1077-7229(04)80041-5

Broderick, P. C., & Jennings. P. A. (2012). Mindfulness for adolescents: A promising approach to supporting emotion regulation and preventing risky behavior. New Directions for Youth Development, 2012(136), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20042

Brown, G. K., Have, T. T, Henriques, G. R., Xie, S. X., Hollander, J. E., & Beck, A. T. (2005). Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts. JAMA, 294(5), 563–570. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.5.563

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). WISQARS. Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

Cha, C. B., Franz, P. J., Guzmán, E. M., Glenn, C. R., Kleiman, E. M., & Nock, M. K. (2018). Annual research review: Suicide among youth – Epidemiology, (potential) etiology, and treatment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(4), 460–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12831

Clemens, E. V., Welfare, L. E., & Williams, A. M. (2011). Elements of successful school reentry after psychiatric hospitalization. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 55(4), 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2010.532521

Cureton, J. L., Clemens, E. V., Henninger, J., & Couch, C. (2018). Pre-professional suicide training for counselors: Results of a readiness assessment. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9898-4

Cureton, J. L., Clemens, E. V., Henninger, J., & Couch, C. (in press). Readiness of counselor education and supervision for suicide training: A CQR study. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 14(3).

Cureton, J. L., & Fink, M. (2019). SHORES: A practical mnemonic for suicide protective factors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 97(3), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12272

Cureton, J. L., & Sheesley, A. P. (2017). Suicide competencies: Stories from counseling interns. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research, 44(2), 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15566382.2017.12069188

Curtin, S. C., & Heron, M. (2019). Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10–24: United States, 2000–2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 352. National Center for Health Statistics.

Davidson, C. L., Wingate, L. R., Rasmussen, K. A., & Slish, M. L. (2009). Hope as a predictor of interpersonal suicide risk. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39(5), 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2009.39.5.499

Diamond, G. S., Kobak, R. R., Krauthamer Ewing, E. S., Levy, S. A., Herres, J. L., Russon, J. M., & Gallop, R. J. (2019). A randomized controlled trial: Attachment-based family and nondirective supportive treatments for youth who are suicidal. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(7), 721–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.10.006

Dunning, D. L., Griffiths, K., Kuyken, W., Crane, C., Foulkes, L., Parker, J., & Dalgleish, T. (2019). Research review: The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents – A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(3), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12980

Early, K. E., & Akers, R. L. (1993). “It’s a white thing”: An exploration of beliefs about suicide in the African-American community. Deviant Behavior, 14(4), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.1993.9967947

Fineran, K. R. (2012). Suicide postvention in schools: The role of the school counselor. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research, 39(2), 14–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15566382.2012.12033884

Fleischmann, A., Bertolote, J. M., Wasserman, D., De Leo, D., Bolhari, J., Botega, N. J., De Silva, D., Phillips, M., Vijayakumar, L., Värnik, A., Schlebusch, L., & Thanh, H. T. T. (2008). Effectiveness of brief intervention and contact for suicide attempters: A randomized controlled trial in five countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86(9), 703–709. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.07.046995

Flook, L., Smalley, S. L., Kitil, M. J., Galla, B. M., Kaiser-Greenland, S., Locke, J., Ishijima, E., & Kasari, C. (2010). Effects of mindful awareness practices on executive functions in elementary school children. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26, 70–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377900903379125

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Sciences, 13(2), 172–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00431

Gallo, L. L. (2018). The relationship between high school counselors’ self-efficacy and conducting suicide risk assessments. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 4(3), 209–225.

https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2017.1422646

Gould, M. S., Klomek, A. B., & Batejan, K. (2009). The role of schools, colleges and universities in suicide prevention. In D. W. Wasserman & C. Wasserman (Eds.), Oxford textbook of suicidiology and suicide prevention: A global perspective (pp. 551–560). Oxford University Press.

Granello, P. F., & Zyromski, B. (2018). Developing a comprehensive school suicide prevention program. Professional School Counseling, 22(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18808128

Huen, J. M. Y., Ip, B. Y. T., Ho, S. M. Y., & Yip, P. S. F. (2015). Hope and hopelessness: The role of hope in buffering the impact of hopelessness on suicidal ideation. PLoS ONE, 10(6), 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130073

Ibrahim, N., Che Din, N., Ahmad, M., Amit, N., Ghazali, S. E., Wahab, S., Kadir, N., Halim, F. W., & Halim, M. (2019). The role of social support and spiritual wellbeing in predicting suicidal ideation among marginalized adolescents in Malaysia. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6861-7

Jobes, D. A., Vergara, G. A., Lanzillo, E. C., & Ridge-Anderson, A. (2019). The potential use of CAMS for suicidal youth: Building on epidemiology and clinical interventions. Children’s Health Care, 48(4), 444–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/02739615.2019.1630279

Jordan, J., McKenna, H., Keeney, S., Cutcliffe, J., Stevenson, C., Slater, P., & McGowan, I. (2012). Providing meaningful care: Learning from the experiences of suicidal young men. Qualitative Health Research, 22(9), 1207–1219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312450367

Kolves, K., & Leo, D. (2017). Suicide methods in children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 26(2), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0865-y

Kwok, S. Y. C. L., & Gu, M. (2019). Childhood neglect and adolescent suicidal ideation: A moderated mediation model of hope and depression. Prevention Science, 20(5), 632–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0962-x

Lanzillo, E. C., Horowitz, L. M., & Pao, M. (2018). Suicide in children. In T. Falcone & J. Timmons-Mitchell (Eds.), Suicide prevention: A practical guide for the practitioner (pp. 73–107). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74391-2

Lapierre, S., Dubé, M., Bouffard, L., & Alain, M. (2007). Addressing suicidal ideations through the realization of meaningful personal goals. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 28(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.28.1.16

Law, K. C., Khazem, L. R., & Anestis, M. D. (2015). The role of emotion dysregulation in suicide as considered through the ideation to action framework. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 30–35.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.014

Lawrence, R. E., Oquendo, M. A., & Stanley, B. (2016). Religion and suicide risk: A systematic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 20(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2015.1004494

Linehan, M. M., Comtois, K. A., Murray, A. M., Brown, M. Z., Gallop, R. J., Heard, H. L., Korslund, K. E., Tutek, D. A., Reynolds, S. K., & Lindenboim, N. (2006). Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs. therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(7), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757

Linehan, M. M., Goodstein, J. L., Nielsen, S. L., & Chiles, J. A. (1983). Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: The Reasons for Living Inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(2), 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.51.2.276

Lizardi, D., Dervic, K., Grunebaum, M. F., Burke, A. K., Mann, J. J., & Oquendo, M. A. (2008). The role of moral objections to suicide in the assessment of suicidal patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42(10), 815–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.09.007

McGlothlin, J., Page, B., & Jager, K. (2016). Validation of the SIMPLE STEPS model of suicide assessment. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 38(4), 298–307. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.38.4.02

Michelmore, L., & Hindley, P. (2012). Help-seeking for suicidal thoughts and self-harm in young people: A systematic review. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(5), 507–524.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00108.x

Murrell, A. R., Al-Jabari, R., Moyer, D., Novamo, E., & Connally, M. L. (2014). An acceptance and commitment therapy approach to adolescent suicide. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 9(3), 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0101639

Osman, A., Downs, W. R., Kopper, B. A., Barrios, F. X., Baker, M. T., Osman, J. R., Besett, T. M., & Linehan, M. M. (1998). The Reasons for Living Inventory for Adolescents (RFL-A): Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54(8), 1063–1078.

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199812)54:8<1063::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-Z

Osman, A., Kopper, B. A., Barrios, F. X., Osman, J. R., Besett, T., & Linehan, M. M. (1996). The Brief Reasons for Living Inventory for Adolescents (BRFL-A). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24(4), 433–443.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01441566

Ougrin, D., Zundel, T., Ng, A. V., Habel, B., & Latif, S. (2013). Teaching therapeutic assessment for self-harm in adolescents: Training outcomes. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 86(1), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.2011.02047.x

Pisani, A. R., Wyman, P. A., Petrova, M., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Goldston, D. B., Xia, Y., & Gould, M. S. (2013). Emotion regulation difficulties, youth–adult relationships, and suicide attempts among high school students in underserved communities. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(6), 807–820.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9884-2

Ren, Y., You, J., Lin, M.-P., & Xu, S. (2019). Low self-esteem, entrapment, and reason for living: A moderated mediation model of suicidal ideation. International Journal of Psychology, 54(6), 807–815.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12532

Sharma, N., & Pumariega, A. J. (2018). Culturally informed treatment of suicidality with diverse youth: General principles. In A. Pumariega & N. Sharma (Eds.), Suicide among diverse youth: A case-based guidebook (pp. 21–30). Springer.

Sheftall, A. H., Asti, L., Horowitz, L. M., Felts, A., Fontanella, C. A., Campo, J. V., & Bridge, J. A. (2016). Suicide in elementary school-aged children and early adolescents. Pediatrics, 138(4).

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0436

Smith-Augustine, S. (2011). School counselors’ comfort and competence with spirituality issues. Counseling & Values, 55(2), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.2011.tb00028.x

Sources of Strength. (2017). Strength specific campaigns. https://sourcesofstrength.org/strength-specific-campaigns

Stanley, B., & Brown, G. K. (2012). Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.01.001

Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2019a). Preventing suicide: A community engagement toolkit. https://www.sprc.org/resources-programs/preventing-suicide-community-engagement-toolkit

Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2019b). Understanding risk and protective factors for suicide: A primer for preventing suicide. https://www.sprc.org/resources-programs/understanding-risk-protective-factors-suicide-primer-preventing-suicide

Suicide Prevention Resource Center, & Rodgers, P. (2011). Understanding risk and protective factors for suicide: A primer for preventing suicide. http://www.sprc.org/sites/default/files/migrate/library/RiskProtectiveFactorsPrimer.pdf

Taliaferro, L. A., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2014). Risk and protective factors that distinguish adolescents who attempt suicide from those who only consider suicide in the past year. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12046

Tucker, R. P., Wingate, L. R., O’Keefe, V. M., Mills, A. C., Rasmussen, K., Davidson, C. L., & Grant, D. M. (2013). Rumination and suicidal ideation: The moderating roles of hope and optimism. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 606–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.013

Ungar, M., Connelly, G., Liebenberg, L., & Theron, L. (2019). How schools enhance the development of young people’s resilience. Social Indicators Research, 145(2), 615–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1728-8

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. (2012). 2012 national strategy for suicide prevention: Goals and objectives for action. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK109917

Villares, E., Lemberger, M., Brigman, G., & Webb, L. (2011). Student Success Skills: An evidence-based school counseling program grounded in humanistic theory. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 50(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2011.tb00105.x

Wai, C. M., Talib, M. A., Yaacob, S. N., Tan, J.-P., Awang, H., Hassan, S., & Ismail, Z. (2014). Hope and its relation to suicidal risk behaviors among Malaysian adolescents. Asian Social Science, 10(12), 67–71. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n12p67

Walker, R. (2020, January 17). Black kids and suicide: Why are rates so high, and so ignored? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/black-kids-and-suicide-why-are-rates-so-high-and-so-ignored-127066

Ward, J. E., & Odegard, M. A. (2011). A proposal for increasing student safety through suicide prevention in schools. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 84(4), 144–149.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2011.564981

World Health Organization. (2006). Preventing suicide: A resource for counsellors. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43487/9241594314_eng.pdf;jsessionid=791EEAFBE71ECDD1039FCBF04E3C8711?sequence=1

Wright-Berryman, J. L., Hudnall, G., Bledsoe, C. J., & Lloyd, M. (2019). Suicide concern reporting among Utah youths served by a school-based peer-to-peer prevention program. Children & Schools, 41(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/CS/CDY026

Wyman, P. A., Brown, C. H., LoMurray, M., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Petrova, M., Yu, Q., Walsh, E., Tu, X., & Wang, W. (2010). An outcome evaluation of the Sources of Strength suicide prevention program delivered by adolescent peer leaders in high schools. American Journal of Public Health, 100(9), 1653–1661.

https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.190025

Wyman, P. A., Gaudieri, P. A., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Cross, W., Brown, C. H., Sworts, L., West, J., Burke, K. C., & Nathan, J. (2009). Emotional triggers and psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation in urban children with elevated aggressive-disruptive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(7), 917–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9330-4

Yip, P. S. F., Caine, E., Yousuf, S., Chang, S.-S., Wu, K. C.-C., & Chen, Y.-Y. (2012). Means restriction for suicide prevention. The Lancet, 379(9834), 2393–2399. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2

Diane M. Stutey, PhD, NCC, LPC, RPT-S, is a licensed school counselor and an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs. Jenny L. Cureton, PhD, LPC (TX, CO), is an assistant professor at Kent State University. Kim Severn, MA, LPC, is a licensed school counselor and instructor at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs. Matthew Fink, MA, is a doctoral student at Kent State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Diane Stutey, 1420 Austin Bluffs Parkway, Colorado Springs, CO 80918, dstutey@uccs.edu.

Feb 26, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 1

Ryan M. Cook, Heather J. Fye, Janelle L. Jones, Eric R. Baltrinic

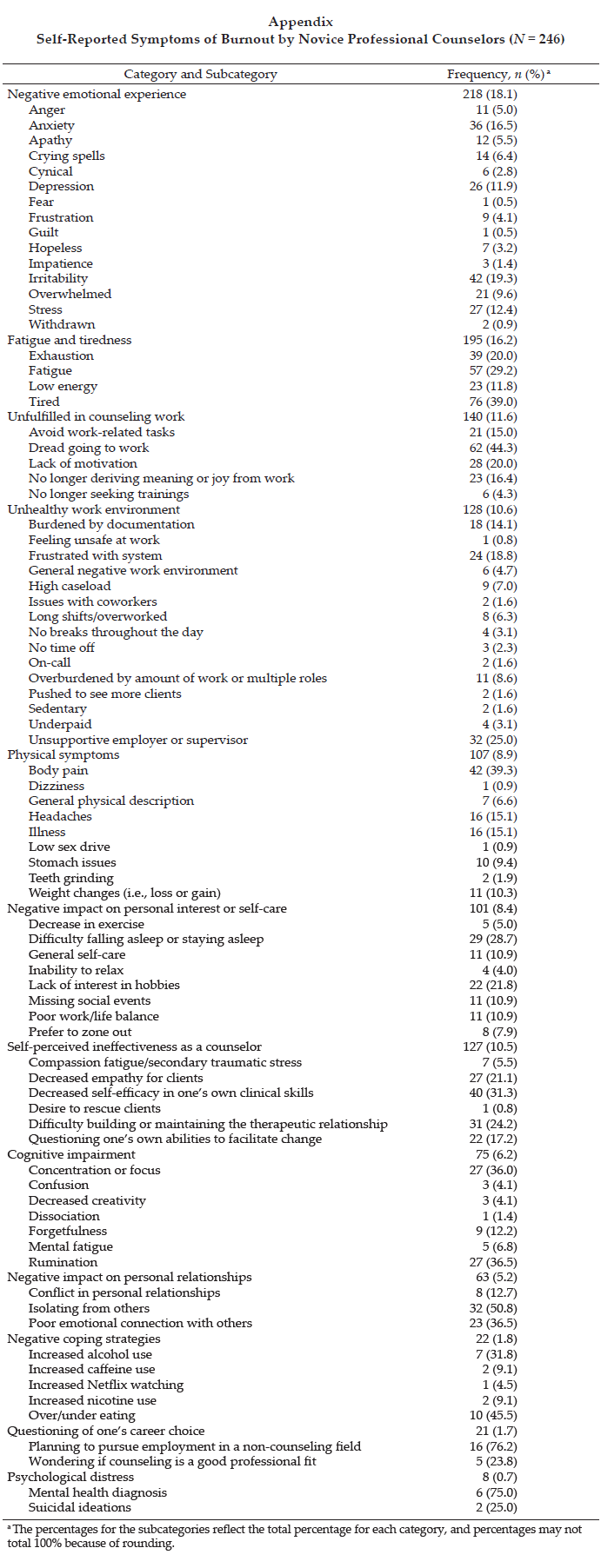

This study explored the self-reported symptoms of burnout in a sample of 246 novice professional counselors. The authors inductively analyzed 1,205 discrete units using content analysis, yielding 12 categories and related subcategories. Many emergent categories aligned with existing conceptualizations of burnout, while other categories offered new insights into how burnout manifested for novice professional counselors. Informed by these findings, the authors implore counseling scholars to consider, in their conceptualization of counselor burnout, a wide range of burnout symptoms, including those that were frequently endorsed symptoms (e.g., negative emotional experience, fatigue and tiredness, unfulfilled in counseling work) as well as less commonly endorsed symptoms (e.g., negative coping strategies, questions of one’s career choice, psychological distress). Implications for novice professional counselors and supervisors are offered, including a discussion about counselors’ experiences of burnout to ensure they are providing ethical services to their clients.

Keywords: novice professional counselors, burnout, content analysis, conceptualization, symptoms

The term high-touch professions refers to the fields that require professionals to provide ongoing and intense emotional services to clients (Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Although such work can be highly rewarding, these professionals are also at risk for burnout (Bardhoshi et al., 2019). In counseling, professionals are called to provide ongoing and intensive mental health services to clients with trauma histories (Foreman, 2018) and complicated needs (Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014). The risk of burnout is exacerbated by the fact that counselors often work in professional environments that are highly demanding and lack resources to serve their clients (Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014; Maslach & Leiter, 2016).

The consequences of burnout for counselors and clients can be considerable (Bardhoshi et al., 2019). Potential impacts include a decline in counselors’ self-care, strain of personal relationships, and damage to their overall emotional health (Bardhoshi et al., 2019; Cook et al., 2020; Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Unaddressed burnout might also lead to more serious professional issues like impairment (e.g., substance use, mental illness, personal crisis, or illness; Lawson et al., 2007). Thus, self-monitoring symptoms of burnout is of the utmost importance for counselors to ensure they are providing ethical services to their clients (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014).

Although burnout is an occupational risk to all counselors (e.g., Bardhoshi et al., 2019; J. Lee et al., 2011; S. M. Lee et al., 2007), novice professional counselors may be especially vulnerable to burnout (Thompson et al., 2014; Westwood et al., 2017; Yang & Hayes, 2020). In the current study, we define novice professional counselors as those who are currently engaged in supervision for licensure in their respective states. Novice professional counselors face a multitude of challenges, such as managing large caseloads, working long hours for low wages, and receiving limited financial support for client care (Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014). Even though their professional competencies are still developing (Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014; Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2013), these counselors receive minimal direct oversight from a supervisor (Cook & Sackett, 2018). However, to date, no study has exclusively examined novice professional counselors’ descriptions of their experiences of burnout. Input from these counselors is important to understand their specific issues of counselor burnout. Other helping professionals have studied a rich context of practitioners’ burnout experiences. For example, Warren et al. (2012) examined open-ended text responses of people who treated clients with eating disorders and found nuanced contributors to burnout among these providers, including patient descriptors (e.g., personality, engagement in treatment), work-related descriptors (e.g., excessive work hours, inadequate resources), and therapist descriptors (e.g., negative emotional response, self-care). Accordingly, we employed a similar approach to examine the open-ended qualitative responses of 246 novice professional counselors’ self-reported symptoms of burnout.

Conceptual Framework of Burnout

Burnout is defined as “a psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” (Maslach & Leiter, 2016, p. 103). Although there are multiple conceptual frameworks of burnout (e.g., Kristensen et al., 2005; S. M. Lee et al., 2007; Maslach & Jackson, 1981; Shirom & Melamed, 2006; Stamm, 2010), the predominant model used to study burnout is the one developed by Maslach and Jackson (1981), which is measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). Informed by qualitative research, Maslach and Jackson (1981) developed the MBI and conceptualized burnout for all human service professionals as a three-dimensional model consisting of Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Decreased Personal Accomplishment. Exhaustion is signaled by emotional fatigue, loss of energy, or feeling drained. Depersonalization is characterized by cynicism or negative attitudes toward clients, while Decreased Personal Accomplishment is indicated by a lack of fulfillment in one’s work or feeling ineffective. This conceptualization of burnout has been used to develop several versions of the MBI that are targeted for different professions (e.g., human services, education) and for professionals in general.

Despite the prominence of the MBI model in the burnout literature (Koutsimani et al., 2019), other scholars (e.g., Kristensen et al., 2005; Shirom & Melamed, 2006) have argued for a different conceptualization of burnout, noting several shortcomings of Maslach and Jackson’s (1981) three-dimensional model. Shirom and Melamed (2006) criticized the lack of theoretical framework of the MBI and noted that the factors were derived via factor analysis. They developed the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure (Shirom & Melamed, 2006), a measure informed by the Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989), which measures burnout as a depletion of physical, emotional, and cognitive resources using two subscales: Physical Fatigue and Cognitive Weariness.

Kristensen et al. (2005) also criticized the utility of the MBI for numerous reasons, including the lack of theoretical underpinnings of the instrument. Therefore, they developed the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory to capture burnout in professionals across disciplines, most notably human service professionals. From Kristensen et al.’s perspective, the underlying cause of burnout is physical and psychological exhaustion, which occurs across three domains: Personal Burnout (i.e., burnout that is attributable to the person themselves), Work-Related Burnout (i.e., burnout that is attributable to the workplace), and Client-Related Burnout (i.e., burnout that is attributable to their work with clients; Kristensen et al., 2005).

Stamm (2010) conceptualized the construct of professional quality of life for helping professionals, which included three dimensions: Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress. Burnout, as theorized by Stamm, is marked by feelings of hopelessness, frustration, and anger, as well as a belief that one’s own work is unhelpful to others, which results in a decline in professional performance. The experience of burnout may also be caused by an overburdening workload or working in an unsupportive environment (Stamm, 2010). Stamm’s model is reflected in the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL), and this instrument has been used by counseling scholars (e.g., Lambert & Lawson, 2013; Thompson et al., 2014).

A reason for variations in the conceptualization of burnout is that it manifests differently across professions (Maslach & Leiter, 2016). The only counseling-specific model of burnout is conceptualized by S. M. Lee et al. (2007), who developed the Counselor Burnout Inventory (CBI). The CBI was informed by the three dimensions of the MBI and additionally captured the unique work environment of professional counselors and its impact on their personal lives. As such, the CBI poses a five-dimensional model consisting of Exhaustion, Incompetence, Negative Work Environment, Devaluing Client, and Deterioration in Personal Life. In recent years, the CBI has been the instrument predominantly used by researchers to study counselor burnout (e.g., Bardhoshi et al., 2019; Fye et al., 2020; J. Lee et al., 2011).

The Current Study

J. Lee et al. (2011) noted the challenges of studying counselor burnout across diverse samples. They encouraged scholars to examine burnout within homogenous samples of counselors in order to offer more nuanced implications for each group. Prior scholarship (e.g., Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014; Thompson et al., 2014) suggested that novice professional counselors may be at risk of burnout, and despite the aforesaid vulnerabilities (e.g., low wages, work with high need clients, professional competency limitations), their self-reported manifestation of burnout symptoms have yet to be studied.

We acknowledge the critical importance of studying burnout in the profession of counseling. However, repeatedly relying on data from similar instruments to measure burnout may fail to capture new or relevant information about the phenomenon (Kristensen et al., 2005) for human service professionals (e.g., Maslach & Jackson, 1981) or professional counselors (e.g., S. M. Lee et al., 2007). Alternatively, content analysis, which focuses on the analysis of open-ended qualitative text (Krippendorff, 2013), may better capture the intricacies of burnout that could not be measured using quantitative instruments (e.g., Warren et al., 2012). Thus, we aimed to address the following research question: What are novice professional counselors’ self-reported symptoms of burnout?

Methodology

Participants

Participants in the current study were 246 postgraduate counselors who were currently receiving supervision for licensure. The age of participants ranged from 23 to 69, averaging 36.91 (SD = 10.15) years. The majority of participants identified as female (n = 195, 79.3%), while 22 participants identified as male (8.9%), four identified as non-binary (1.6%), nine indicated that they did not want to disclose their gender (3.7%), and 16 participants did not respond to the item (6.5%). The participants’ race/ethnicity was reported as follows: White (n = 186; 75.6%), Multiracial (n = 15, 6.1%), Latino/Hispanic (n = 7, 3.3%), Black (n = 6, 2.4%), Asian (n = 6, 2.4%), American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 3, 0.8%), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (n = 1, 0.4%), and Other (n = 7, 3.3%), while 15 participants declined to respond to the item (6.1%). The self-reported race/ethnicity demographic information is comparable to all counselors in the profession, based on DataUSA (2018). The participants’ client caseload ranged from 1 to 650 (M = 41.88; Mdn = 30.0; SD = 53.74). On average, participants had worked as counselors for 5 years (Mdn = 3.3; SD = 4.87). The provided percentages may not total to 100 percent because of rounding and because participants were afforded the option to select more than one response.

Procedure

To answer our research question, we used data from a larger study of novice professional counselor burnout, which included both quantitative and qualitative data. After receiving IRB approval, we obtained lists of names and email addresses of counselors engaged in supervision for licensure from the licensing boards in seven states: Florida, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin. We aimed to recruit a nationally representative sample by purposefully choosing at least one state from each of the ACA regions. In addition, states were selected based upon our ability to obtain a list of counselors who were engaged in supervision for licensure from the respective licensure boards. We were able to survey at least one state from each ACA region except the North Atlantic Region. After removing invalid email addresses, we invited 6,874 potential participants by email to complete an online survey in Qualtrics. This survey was completed by 560 counselors, yielding a response rate of 8.15%. This response rate is consistent with other studies that employed a similar design (Gonzalez et al., 2020). All participants were asked, Do you believe you are currently experiencing symptoms of burnout?, to which participants responded (a) yes or (b) no. Participants who responded yes were then prompted with the direction, Describe your symptoms of burnout, using an open-ended text box, which did not have a character limit. A total of 246 participants (43.9%) responded yes and qualitatively described their symptoms of burnout. On average, participants provided 30.31 words (SD = 36.30). We answered our research question for the current study using only the qualitative data, which aligns with the American Psychological Association’s Journal Article Reporting Standards for Qualitative Research (JARS-Qual; Levitt et al., 2018).

Data Analysis

To answer our research question, we analyzed participants’ open-ended responses using content analysis, which allows for systematic and contextualized review of text data (Krippendorff, 2013). As recommended by Krippendorff (2013), we followed the steps of conducting content analysis: unitizing, sampling, recording, and reducing. We first separated the responses of the 246 participants into discrete units. For example, “feeling exhausted and back pain” was coded as two units: (a) feeling exhausted and (b) back pain. This process resulted in a total of 1,205 discrete units. We reduced our data into categories using an inductive approach, which allowed for new categories to emerge from the data without an a priori theory (Krippendorff, 2013). Although there are multiple conceptualizations of burnout (Maslach & Jackson, 1981; S. M. Lee et al., 2007) that could have informed our analysis (i.e., deductive approach; Krippendorff, 2013), we chose an inductive approach to capture the conceptualization of burnout for novice professional counselors—generating categories based on participants’ explanations of their own symptoms of burnout (Kondracki et al., 2002).

To that end, we developed a codebook by randomly selecting roughly 10% of the discrete units to code as a pretest. Our first and third authors, Ryan M. Cook and Janelle L. Jones, independently reviewed the discrete units, met to discuss and develop categories and corresponding definitions, and coded the pretest data together to enhance reliability. This process yielded a codebook that consisted of 12 categories. Cook and Jones then used the codebook (categories and definitions) to independently code the remaining 90% of the data across three rounds (i.e., 30% increments). After each round, Cook and Jones met to discuss discrepancies and to reach consensus on the final codes. The overall agreement between Cook and Jones was 97% and the interrater reliability was acceptable (Krippendorff α = .80; Krippendorff, 2013), which was calculated using ReCal2 (Freelon, 2013). At the end of the coding process, Cook and Jones reviewed their notes for each code and further organized them into subcategories based on commonalities. The second author, Heather J. Fye, served as the auditor (see Researcher Trustworthiness section) and reviewed the entire coding process.

Researcher Trustworthiness

The research team consisted of four members, three counselor educators and one counselor education and supervision doctoral student. The first and third authors, Cook and Jones, served as coders, while the second author, Fye, served as the auditor and the fourth author, Eric R. Baltrinic, served as a qualitative consultant. The counseling experience of the four authors ranged from 4 to 18 years, and the supervision experience of the authors ranged from 3 to 9 years. Cook, Fye, and Baltrinic are licensed professional counselors and three of the authors are credentialed as either a National Certified Counselor or Approved Clinical Supervisor.

We all acknowledged our personal experiences of burnout to some degree as practicing counselors as well as observing the consequences of burnout to our students and supervisees. All members of the research team had prior experience studying counselor burnout. Although these collective experiences enriched our understanding of the subject matter, we also attempted to bracket our assumptions and biases throughout the research process. To increase the trustworthiness of the coding process, the auditor, Fye, reviewed the codebook, categories and subcategories, discreteness, and two coders’ notes coding process after the pretest and rounds of coding. Fye provided feedback on the category definitions, coding process, and coding decisions during the analysis process.

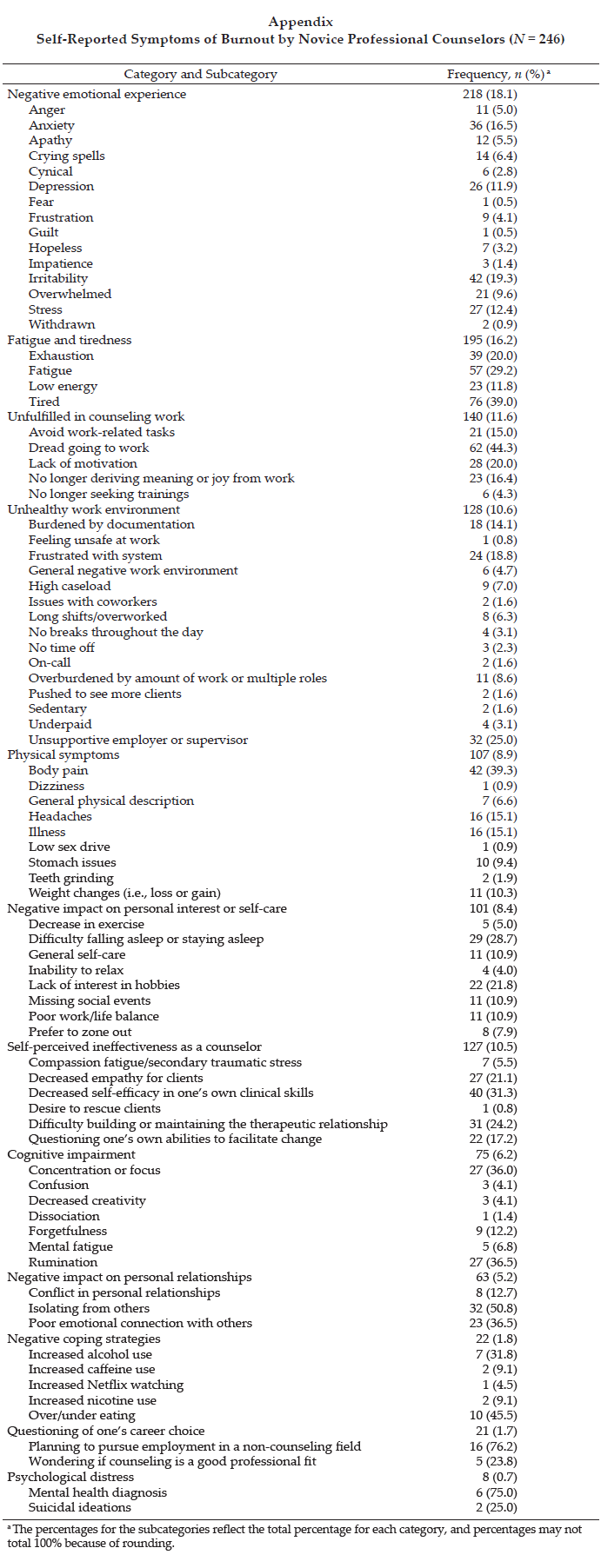

Results

Using an inductive approach, 12 categories and related subcategories emerged from the 1,205 discrete self-reported symptoms of burnout. Full results, including the 12 categories and subcategories, as well as the frequencies of the categories and subcategories, are presented in the Appendix. We discuss each category in detail and provide illustrative examples of each category using direct participant quotes (Levitt et al., 2018).

Negative Emotional Experience

Of the 1,205 coded units, 218 units (18.1%) were coded into the category negative emotional experience. This category reflected participants’ descriptions of experiencing negative feelings related to their work as counselors (e.g., anxiety, depression, irritability) or unwanted negative emotions (e.g., crying spells). This category included 15 subcategories, and the units coded into these subcategories reflected the participants’ descriptions of a wide range of negative feelings. For example, one participant reported she was “struggling to feel happy,” while another participant shared that she “is carrying a heavy burden [that] no one understands or is aware of.” Some participants also reported crying spells. One participant shared she “has fits of crying,” while another reported she “[cries] in the bathroom at work.”

Fatigue and Tiredness

The category fatigue and tiredness was coded 195 times (16.2%) and included four subcategories. This category captured participants’ descriptions of feeling exhausted, fatigued, or tired. Units coded into this category included the participants’ indications that they feel exhausted, despite sleeping well. For example, one participant described feeling perpetually exhausted—“nothing recharges my batteries”— while another participant stated that her fatigue worsened as the week progressed: “[I feel] more and more exhausted throughout the week.”

Unfulfilled in Counseling Work

The category unfulfilled in counseling work captured the participants’ descriptions of no longer deriving joy at work, dread in going to work or completing work-related responsibilities, or lacking motivation to do work. This category was coded 140 times (11.6%) and subcategories included five subcategories. Avoidance of burdensome administrative responsibilities (e.g., paperwork) were commonly reported units that were captured in this category. For example, a participant noted “putting off doing notes.” Units also captured in this category reflected participants’ self-report of no longer feeling motivated or deriving joy from their work, which ultimately led some participants to stop seeking training. For instance, a participant described herself as “going through the motions at work,” and another added that she was no longer “motivated to improve [her] skills.”

Unhealthy Work Environment