Dec 16, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 4

Dodie Limberg, Therese Newton, Kimberly Nelson, Casey A. Barrio Minton, John T. Super, Jonathan Ohrt

We present a grounded theory based on interviews with 11 counselor education doctoral students (CEDS) regarding their research identity development. Findings reflect the process-oriented nature of research identity development and the influence of program design, research content knowledge, experiential learning, and self-efficacy on this process. Based on our findings, we emphasize the importance of mentorship and faculty conducting their own research as a way to model the research process. Additionally, our theory points to the need for increased funding for CEDS in order for them to be immersed in the experiential learning process and research courses being tailored to include topics specific to counselor education.

Keywords: grounded theory, research identity development, counselor education doctoral students, mentoring, experiential

Counselor educators’ professional identity consists of five primary roles: counseling, teaching, supervision, research, and leadership and advocacy (Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2015). Counselor education doctoral programs are tasked with fostering an understanding of these roles in future counselor educators (CACREP, 2015). Transitions into the counselor educator role have been described as life-altering and associated with increased levels of stress, self-doubt, and uncertainty (Carlson et al., 2006; Dollarhide et al., 2013; Hughes & Kleist, 2005; Protivnak & Foss, 2009); however, little is known about specific processes and activities that assist programs to intentionally cultivate transitions into these identities.

Although distribution of faculty roles varies depending on the type of position and institution, most academic positions require some level of research or scholarly engagement. Still, only 20% of counselor educators are responsible for producing the majority of publications within counseling journals, and 19% of counselor educators have not published in the last 6 years (Lambie et al., 2014). Borders and colleagues (2014) found that the majority of application-based research courses in counselor education doctoral programs (e.g., qualitative methodology, quantitative methodology, sampling procedures) were taught by non-counseling faculty members, while counseling faculty members were more likely to teach conceptual or theoretical research courses. Further, participants reported that non-counseling faculty led application-based courses because there were no counseling faculty members who were well qualified to instruct such courses (Borders et al., 2014).

To assist counselor education doctoral students’ (CEDS) transition into the role of emerging scholar, Carlson et al. (2006) recommended that CEDS become active in scholarship as a supplement to required research coursework. Additionally, departmental culture, mentorship, and advisement have been shown to reduce rates of attrition and increase feelings of competency and confidence in CEDS (Carlson et al., 2006; Dollarhide et al., 2013; Protivnak & Foss, 2009). However, Borders et al. (2014) found that faculty from 38 different CACREP-accredited programs reported that just over half of the CEDS from these programs became engaged in research during their first year, with nearly 8% not becoming involved in research activity until their third year. Although these experiences assist CEDS to develop as doctoral students, it is unclear which of these activities are instrumental in cultivating a sound research identity (RI) of CEDS. Understanding how RI is cultivated throughout doctoral programs may provide ways to enhance research within the counseling profession. Understanding this developmental process will inform methods for improving how counselor educators prepare CEDS for their professional roles.

Research Identity

Research identity is an ambiguous term within the counseling literature, with definitions that broadly conceptualize the construct in terms of beliefs, attitudes, and efficacy related to scholarly research, along with a conceptualization of one’s own overall professional identity (Jorgensen & Duncan, 2015; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Ponterotto & Grieger, 1999; Reisetter et al., 2011). Ponterotto and Grieger (1999) described RI as how one views oneself as a scholar or researcher, noting that research worldview (i.e., the lens through which they view, approach, and manage the process of research) impacts how individuals conceptualize, conduct, and interpret results. This perception and interpretation of research as important to RI is critical to consider, as it is common practice for CEDS to enter doctoral studies with limited research experience. Additionally, many CEDS enter into training with a strong clinical identity (Dollarhide et al., 2013), but coupled with the void of research experience or exposure, CEDS may perceive research as disconnected and separate from counseling practice (Murray, 2009). Furthermore, universities vary in the support (e.g., graduate assistant, start-up funds, course release, internal grants) they provide faculty to conduct research.

The process of cultivating a strong RI may be assisted through wedding science and practice (Gelso et al., 2013) and aligning research instruction with values and theories often used in counseling practice (Reisetter et al., 2011). More specifically, Reisetter and colleagues (2011) found that cultivation of a strong RI was aided when CEDS were able to use traditional counseling skills such as openness, reflexive thinking, and attention to cognitive and affective features while working alongside research “participants” rather than conducting studies on research “subjects.” Counseling research is sometimes considered a practice limited to doctoral training and faculty roles, perhaps perpetuating the perception that counseling research and practice are separate and distinct phenomena (Murray, 2009). Mobley and Wester (2007) found that only 30% of practicing clinicians reported reading and integrating research into their work; therefore, early introduction to research may also aid in diminishing the research–practice gap within the counseling profession. The cultivation of a strong RI may begin through exposure to research and scholarly activity at the master’s level (Gibson et al., 2010). More recently, early introduction to research activity and counseling literature at the master’s level is supported within the 2016 CACREP Standards (2015), specifically the infusion of current literature into counseling courses (Standard 2.E.) and training in research and program evaluation (Standard 2.F.8.). Therefore, we may see a shift in the research–practice gap based on these included standards in years to come.

Jorgensen and Duncan (2015) used grounded theory to better understand how RI develops within master’s-level counseling students (n = 12) and clinicians (n = 5). The manner in which participants viewed research, whether as separate from their counselor identity or as fluidly woven throughout, influenced the development of a strong RI. Further, participants’ views and beliefs about research were directly influenced by external factors such as training program expectations, messages received from faculty and supervisors, and academic course requirements. Beginning the process of RI development during master’s-level training may support more advanced RI development for those who pursue doctoral training.

Through photo elicitation and individual interviews, Lamar and Helm (2017) sought to gain a deeper understanding of CEDS’ RI experiences. Their findings highlighted several facets of the internal processes associated with RI development, including inconsistency in research self-efficacy, integration of RI into existing identities, and finding methods of contributing to the greater good through research. The role of external support during the doctoral program was also a contributing factor to RI development, with multiple participants noting the importance of family and friend support in addition to faculty support. Although this study highlighted many facets of RI development, much of the discussion focused on CEDS’ internal processes, rather than the role of specific experiences within their doctoral programs.

Research Training Environment

Literature is emerging related to specific elements of counselor education doctoral programs that most effectively influence RI. Further, there is limited research examining individual characteristics of CEDS that may support the cultivation of a strong RI. One of the more extensively reviewed theories related to RI cultivation is the belief that the research training environment, specifically the program faculty, holds the most influence and power over the strength of a doctoral student’s RI (Gelso et al., 2013). Gelso et al. (2013) also hypothesized that the research training environment directly affects students’ research attitudes, self-efficacy, and eventual productivity. Additionally, Gelso et al. outlined factors in the research training environment that influence a strong RI, including (a) appropriate and positive faculty modeling of research behaviors and attitudes, (b) positive reinforcement of student scholarly activities, (c) the emphasis of research as a social and interpersonal activity, and (d) emphasizing all studies as imperfect and flawed. Emphasis on research as a social and interpersonal activity consistently received the most powerful support in cultivating RI. This element of the research training environment may speak to the positive influence of working on research teams or in mentor and advising relationships (Gelso et al., 2013).

To date, there are limited studies that have addressed the specific doctoral program experiences and personal characteristics of CEDS that may lead to a strong and enduring RI. The purpose of this study was to: (a) gain a better understanding of CEDS’ RI development process during their doctoral program, and (b) identify specific experiences that influenced CEDS’ development as researchers. The research questions guiding the investigation were: 1) How do CEDS understand RI? and 2) How do CEDS develop as researchers during their doctoral program?

Method

We used grounded theory design for our study because of the limited empirical data about how CEDS develop an RI. Grounded theory provides researchers with a framework to generate a theory from the context of a phenomenon and offers a process to develop a model to be used as a theoretical foundation (Charmaz, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Prior to starting our investigation, we received IRB approval for this study.

Research Team and Positionality

The core research team consisted of one Black female in the second year of her doctoral program, one White female in the first year of her doctoral program, and one White female in her third year as an assistant professor. A White male in his sixth year as an assistant professor participated as the internal auditor, and a White male in his third year as a clinical assistant professor participated as the external auditor. Both doctoral students had completed two courses that covered qualitative research design, and all three faculty members had experience utilizing grounded theory. Prior to beginning our work together, we discussed our beliefs and experiences related to RI development. All members of the research team were in training to be or were counselor educators and researchers, and we acknowledged this as part of our positionality. We all agreed that we value research as part of our roles as counselor educators, and we discussed our beliefs that the primary purpose of pursuing a doctoral degree is to gain skills as a researcher rather than an advanced counselor. We acknowledged the strengths that our varying levels of professional experiences provided to our work on this project, and we also recognized the power differential within the research team; thus, we added auditors to help ensure trustworthiness. All members of the core research team addressed their biases and judgments regarding participants’ experiences through bracketing and memoing to ensure that participants’ voices were heard with as much objectivity as possible (Hays & Wood, 2011). We recorded our biases and expectations in a meeting prior to data collection. Furthermore, we continued to discuss assumptions and biases in order to maintain awareness of the influence we may have on data analysis (Charmaz, 2014). Our assumptions included (a) the influence of length of time in a program, (b) the impact of mentoring, (c) how participants’ research interests would mirror their mentors’, (d) that beginning students may not be able to articulate or identify the difference between professional identity and RI, (e) that CEDS who want to pursue academia may identify more as researchers than in other roles (i.e., teaching, supervision), and (f) that coursework and previous experience would influence RI. Each step of the data analysis process provided us the opportunity to revisit our biases.

Participants and Procedure

Individuals who were currently enrolled in CACREP-accredited counselor education and supervision doctoral programs were eligible for participation in the study. We used purposive sampling (Glesne, 2011) to strategically contact eight doctoral program liaisons at CACREP-accredited doctoral programs via email to identify potential participants. The programs were selected to represent all regions and all levels of Carnegie classification. The liaisons all agreed to forward an email that included the purpose of the study and criteria for participation. A total of 11 CEDS responded to the email, met selection criteria, and participated in the study. We determined that 11 participants was an adequate sample size considering data saturation was reached during the data analysis process (Creswell, 2007). Participants represented eight different CACREP-accredited doctoral programs across six states. At the time of the interviews, three participants were in the first year of their program, five were in their second year, and three were in their third year. To prevent identification of participants, we report demographic data in aggregate form. The sample included eight women and three men who ranged in age from 26–36 years (M = 30.2). Six participants self-identified as White (non-Hispanic), three as multiracial, one as Latinx, and one as another identity not specified. All participants held a master’s degree in counseling; they entered their doctoral programs with 0–5 years of post-master’s clinical experience (M = 1.9). Eight participants indicated a desire to pursue a faculty position, two indicated a desire to pursue academia while also continuing clinical work, and one did not indicate a planned career path. Of those who indicated post-doctoral plans, seven participants expected to pursue a faculty role within a research-focused institution and three indicated a preference for a teaching-focused institution. All participants had attended and presented at a state or national conference within the past 3 years, with the number of presentations ranging from three to 44 (M = 11.7). Nine participants had submitted manuscripts to peer-reviewed journals and had at least one manuscript published or in press. Finally, four participants had received grant funding.

Data Collection

We collected data through a demographic questionnaire and semi-structured individual interviews. The demographic questionnaire consisted of nine questions focused on general demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age, race, and education). Additionally, we asked questions focused on participants’ experiences as researchers (i.e., professional organization affiliations, service, conference presentations, publications, and grant experience). These questions were used to triangulate the data. The semi-structured interviews consisted of eight open-ended questions asked in sequential order to promote consistency across participants (Heppner et al., 2016) and we developed them from existing literature. Examples of questions included: 1) How would you describe your research identity? 2) Identify or talk about things that happened during your doctoral program that helped you think of yourself as a researcher, and 3) Can you talk about any experiences that have created doubts about adopting the identity of a researcher? The two doctoral students on the research team conducted the interviews via phone. Interviews lasted approximately 45–60 minutes and were audio recorded. After all interviews were conducted, a member of the research team transcribed the interviews.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

We followed grounded theory data analysis procedures outlined by Corbin and Strauss (2008). Prior to data analysis, we recorded biases, read through all of the data, and discussed the coding process to ensure consistency. We followed three steps of coding: 1) open coding, 2) axial coding, and 3) selective coding. Our first step of data analysis was open coding. We read through the data several times and then started to create tentative labels for chunks of data that summarized what we were reading. We recorded examples of participants’ words and established properties of each code. We then coded line-by-line together using the first participant transcript in order to have opportunities to check in and share and compare our open codes. Then we individually coded the remainder of the participants and came back together as a group to discuss and memo. We developed a master list of 184 open codes.

Next, we moved from inductive to deductive analysis using axial coding to identify relationships among the open codes. We identified relationships among the open codes and grouped them into categories. Initially we created a list of 55 axial codes, but after examining the codes further, we made a team decision to collapse them to 19 axial codes that were represented as action-oriented tasks within our theory (see Table 1).

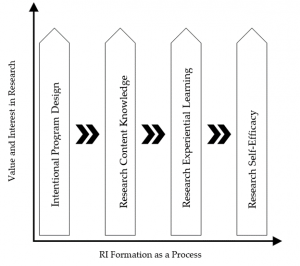

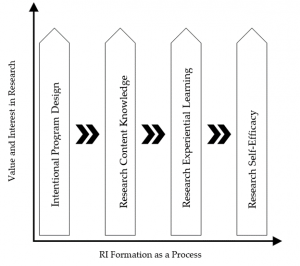

Last, we used selective coding to identify core variables that include all of the data. We found that two factors and four subfactors most accurately represent the data (see Figure 1). The auditor was involved in each step of coding and provided feedback throughout. To enhance trustworthiness and manage bias when collecting and analyzing the data, we applied several strategies: (a) we recorded memos about our ideas about the codes and their relationships (i.e., reflexivity; Morrow, 2005); (b) we used investigator triangulation (i.e., involving multiple investigators to analyze the data independently, then meeting together to discuss; Archibald, 2015); (c) we included an internal and external auditor to evaluate the data (Glesne, 2011; Hays & Wood, 2011); (d) we conducted member checking by sending participants their complete transcript and summary of the findings, including the visual (Creswell & Miller, 2000); and (e) we used multiple sources of data (i.e., survey questions on the demographic form; Creswell, 2007) to triangulate the data.

Table 1

List of Factors and Subfactors

Factor 1: Research Identity Formation as a Process

unable to articulate what research identity is

linking research identity to their research interests or connecting it to their professional experiences

associating research identity with various methodologies

identifying as a researcher

understanding what a research faculty member does

Factor 2: Value and Interest in Research

desiring to conduct research

aspiring to maintain a degree of research in their future role

making a connection between research and practice and contributing to the counseling field

Subfactor 1: Intentional Program Design

implementing an intentional curriculum

developing a research culture (present and limited)

active faculty mentoring and modeling of research

Subfactor 2: Research Content Knowledge

understanding research design

building awareness of the logistics of a research study

learning statistics

Subfactor 3: Research Experiential Learning

engaging in scholarly activities

conducting independent research

having a graduate research assistantship

Subfactor 4: Research Self-Efficacy

receiving external validation

receiving growth-oriented feedback (both negative and positive)

Figure 1

Model of CEDS’ Research Identity Development

Results

Data analysis resulted in a grounded theory composed of two main factors that support the overall process of RI development among CEDS: (a) RI formation as a process and (b) value and interest in research. The first factor is the foundation of our theory because it describes RI development as an ongoing, formative process. The second main factor, value and interest in research, provides an interpersonal approach to RI development in which CEDS begin to embrace “researcher” as a part of who they are.

Our theory of CEDS’ RI development is represented visually in Figure 1. At each axis of the figure, the process of RI is represented longitudinally, and the value and interest in research increases during the process. The four subfactors (i.e., program design, content knowledge, experiential learning, and self-efficacy) contribute to each other but are also independent components that influence the process and the value and interest. Each subfactor is represented as an upward arrow, which supports the idea within our theory that each subfactor increases through the formation process. Each of these subfactors includes components that are specific action-oriented tasks (see Table 1). In order to make our findings relevant and clear, we have organized them by the two research questions that guided our study. To bring our findings to life, we describe the two major factors, four subfactors, and action-oriented tasks using direct quotes from the participants.

Research Question 1: How Do CEDS Describe RI?

Two factors supported this research question: RI formation as a process and value and interest in research.

Factor 1: Research Identity Formation as a Process

Within this factor we identified five action-oriented tasks: (a) being unable to articulate what research identity is, (b) linking research identity to their research interests or connecting it to their professional experiences, (c) associating research identity with various methodologies, (d) identifying as a researcher, and (e) understanding what a research faculty member does. Participants described RI as a formational process. Participant 10 explained, “I still see myself as a student. . . . I still feel like I have a lot to learn and I am in the process of learning, but I have a really good foundation from the practical experiences I have had [in my doctoral program].” When asked how they would describe RI, many were unable to articulate what RI is, asking for clarification or remarking on how they had not been asked to consider this before. Participants often linked RI to their research interests or professional experiences. For example, Participant 11 said, “in clinical practice, I centered around women and women issues. Feminism has come up as a product of other things being in my PhD program, so with my dissertation, my topic is focused on feminism.” Several participants associated RI with various methodologies, including Participant 7: “I would say you know in terms of research methodology and what not, I strongly align with quantitative research. I am a very quantitative-minded person.” Some described this formational process as the transition to identifying as a researcher:

I actually started a research program in my university, inviting or matching master’s students who were interested in certain research with different research projects that were available. So that was another way of me kind of taking on some of that mentorship role in terms of research. (Participant 9)

As their RI emerged, participants understood what research-oriented faculty members do:

Having faculty talk about their research and their process of research in my doc program has been extremely helpful. They talk about not only what they are working on but also the struggles of their process and so they don’t make it look glamorous all the time. (Participant 5)

Factor 2: Value and Interest in Research

All participants talked about the value and increased interest in research as they went through their doctoral program. We identified three action-oriented tasks within this factor: (a) desiring to conduct research, (b) aspiring to maintain a degree of research in their future role, and (c) making a connection between research and practice and contributing to the counseling field. Participant 6 described, “Since I have been in the doctoral program, I have a bigger appreciation for the infinite nature of it (research).” Participants spoke about an increased desire to conduct research; for example, “research is one of the most exciting parts of being a doc student, being able to think of a new project and carrying out the steps and being able to almost discover new knowledge” (Participant 1). All participants aspired to maintain a degree of research in future professional roles after completion of their doctoral programs regardless of whether they obtained a faculty role at a teaching-focused or research-focused university. For example, Participant 4 stated: “Even if I go into a teaching university, I have intentions in continuing very strongly my research and keeping that up. I think it is very important and it is something that I like doing.” Additionally, participants started to make the connection between research and practice and contributing to the counseling profession:

I think research is extremely important because that is what clinicians refer to whenever they have questions about how to treat their clients, and so I definitely rely upon research to understand views in the field and I value it myself so that I am more well-rounded as an educator. (Participant 6)

Research Question 2: How Do CEDS Develop Their RI During Their Doctoral Program?

The following four subfactors provided a description of how CEDS develop RI during their training: intentional program design, research content knowledge, research experiential learning, and research self-efficacy. Each subfactor contains action-oriented tasks.

Subfactor 1: Intentional Program Design

Participants discussed the impact the design of their doctoral program had on their development as researchers. They talked about three action-oriented tasks: (a) implementing an intentional curriculum, (b) developing a research culture (present and limited), and (c) active faculty mentoring and modeling of research. Participants appreciated the intentional design of the curriculum. For example, Participant 5 described how research was highlighted across courses: “In everything that I have had to do in class, there is some form of needing to produce either a proposal or being a good consumer of research . . . it [the value of research] is very apparent in every course.” Additionally, participants talked about the presence or lack of a research culture. For example, Participant 2 described how “at any given time, I was working on two or three projects,” whereas Participant 7 noted that “gaining research experience is not equally or adequately provided to our doctoral students.” Some participants discussed being assigned a mentor, and others talked about cultivating an organic mentoring relationship through graduate assistantships or collaboration with faculty on topics of interest. However, all participants emphasized the importance of faculty mentoring:

I think definitely doing research with the faculty member has helped quite a bit, especially doing the analysis that I am doing right now with the chair of our program has really helped me see research in a new light, in a new way, and I have been grateful for that. (Participant 1)

The importance of modeling of research was described in terms of faculty actually conducting their own research. For example, Participant 11 described how her professor “was conducting a research study and I was helping her input data and write and analyze the data . . . that really helped me grapple with what research looks like and is it something that I can do.” Participant 10 noted how peers conducting research provided a model:

Having that peer experience (a cohort) of getting involved in research and knowing again that we don’t have to have all of the answers and we will figure it out and this is where we all are, that was also really helpful for me and developing more confidence in my ability to do this [research].

Subfactor 2: Research Content Knowledge

All participants discussed the importance of building their research content knowledge. Research content knowledge consisted of three action-oriented tasks: (a) understanding research design, (b) building awareness of the logistics of a research study, and (c) learning statistics. Participant 1 described their experience of understanding research design: “I think one of the most important pieces of my research identity is to be well-rounded and [know] all of the techniques in research designs.” Participants also described developing an awareness of the logistics of research study, ranging from getting IRB approval to the challenges of data collection. For example, Participant 9 stated:

Seeing what goes into it and seeing the building blocks of the process and also really getting that chance to really think about the study beforehand and making sure you’re getting all of the stuff to protect your clients, to protecting confidentiality, those kind of things. So I think it is kind of understanding more about the research process and also again what goes into it and what makes the research better.

Participants also explained how learning statistics was important; however, a fear of statistics was a barrier to their learning and development. Participant 2 said, “I thought before I had to be a stats wiz to figure anything out, and I realize now that I just have to understand how to use my resources . . . I don’t have to be some stat wiz to actually do [quantitative research].”

Subfactor 3: Research Experiential Learning

Research experiential learning describes actual hands-on experiences participants had related to research. Within our theory, three action-oriented tasks emerged from this subfactor: (a) engaging in scholarly activities, (b) conducting independent research, and (c) having a graduate research assistantship. Engaging in scholarly activities included conducting studies, writing for publication, presenting at conferences, and contributing to or writing a grant proposal. Participant 5 described the importance of being engaged in scholarly activities through their graduate assistantship:

I did have a research graduate assistantship where I worked under some faculty and that definitely exposed me to a higher level of research, and being exposed to that higher level of research allowed me to fine tune how I do research. So that was reassuring in some ways and educational.

Participants also described the importance of leading and conducting their own research via dissertation or other experiences during their doctoral program. For example, Participant 9 said:

Starting research projects that were not involving a faculty member I think has also impacted my work a lot, I learned a lot from that process, you know, having to submit [to] an IRB, having to structure the study and figure out what to do, and so again learning from mistakes, learning from experience, and building self-efficacy.

Subfactor 4: Research Self-Efficacy

The subfactor of research self-efficacy related to the process of participants being confident in identifying themselves and their skills as researchers. We found two action-oriented tasks related to research self-efficacy: (a) receiving external validation and (b) receiving growth-oriented feedback (both negative and positive). Participant 3 described their experience of receiving external validation through sources outside of their doctoral program as helpful in building confidence as a researcher:

I have submitted and have been approved to present at conferences. That has boosted my confidence level to know that they know I am interested in something and I can talk about it . . . that has encouraged me to further pursue research.

Participant 8 explained how receiving growth-oriented feedback on their research supported their own RI development: “People stopped by [my conference presentation] and were interested in what research I was doing. It was cool to talk about it and get some feedback and hear what people think about the research I am doing.”

Discussion

Previous researchers have found RI within counselor education to be an unclear term (Jorgensen & Duncan, 2015; Lamar & Helm, 2017). Although our participants struggled to define RI, our participants described RI as the process of identifying as a researcher, the experiences related to conducting research, and finding value and interest in research. Consistent with previous findings (e.g., Ponterotto & Grieger, 1999), we found that interest in and value of research is an important part of RI. Therefore, our qualitative approach provided us a way to operationally define CEDS’ RI as a formative process of identifying as a researcher that is influenced by the program design, level of research content knowledge, experiential learning of research, and research self-efficacy.

Our findings emphasize the importance of counselor education and supervision doctoral program design. Similar to previous researchers (e.g., Borders et al., 2019; Carlson et al., 2006; Dollarhide et al., 2013; Protivnak & Foss, 2009), we found that developing a culture of research that includes mentoring and modeling of research is vital to CEDS’ RI development. Lamar and Helm (2017) also noted the valuable role faculty mentorship and engagement in research activities, in addition to research content knowledge, has on CEDS’ RI development. Although Lamar and Helm noted that RI development may be enhanced through programmatic intentionality toward mentorship and curriculum design, they continually emphasized the importance of CEDS initiating mentoring relationships and taking accountability for their own RI development. We agree that individual initiative and accountability are valuable and important characteristics for CEDS to possess; however, we also acknowledge that student-driven initiation of such relationships may be challenging in program cultures that do not support RI or do not provide equitable access to mentoring and research opportunities.

Consistent with recommendations by Gelso et al. (2013) and Borders et al. (2014), building a strong foundation of research content knowledge (e.g., statistics, design) is an important component of CEDS’ RI development. Unlike Borders and colleagues, our participants did not discuss how who taught their statistics courses made a difference. Rather, participants discussed the value of experiential learning (i.e., participating on a research team), and conducting research on their own influenced how they built their content knowledge. This finding is similar to Carlson et al.’s (2006) and supports Borders et al.’s findings regarding the critical importance of early research involvement for CEDS.

Implications for Practice

Our grounded theory provides a clear, action-oriented model that consists of multiple tasks that can be applied in counselor education doctoral programs. Given our findings regarding the importance of experiential learning, we acknowledge the importance for increased funding to ensure CEDS are able to focus on their studies and immerse themselves in research experiences. Additionally, design of doctoral programs is crucial to how CEDS develop as researchers. Findings highlight the importance of faculty members at all levels being actively involved in their own scholarship and providing students with opportunities to be a part of it. In addition, we recommend intentional attention to mentorship as an explicit program strategy for promoting a culture of research. Findings also support the importance of coursework for providing students with relevant research content knowledge they can use in research and scholarly activities (e.g., study proposal, conceptual manuscript, conference presentation). Additionally, we recommend offering a core of research courses that build upon one another to increase research content knowledge and experiential application. More specifically, this may include a research design course taught by counselor education faculty at the beginning of the program to orient students to the importance of research for practice; such a foundation may help ensure students are primed to apply skills learned in more technical courses. Finally, we suggest that RI development is a process that is never complete; therefore, counselor educators are encouraged to continue to participate in professional development opportunities that are research-focused (e.g., AARC, ACES Inform, Evidence-Based School Counseling Conference, AERA). More importantly, it should be the charge of these organizations to continue to offer high quality trainings on a variety of research designs and advanced statistics.

Implications for Future Research

Replication or expansion of our study is warranted across settings and developmental levels. Specifically, it would be interesting to examine RI development of pre-tenured faculty and tenured faculty members to see if our model holds or what variations exist between these populations. Or it may be beneficial to assess the variance of RI based on the year a student is in the program (e.g., first year vs. third year). Additionally, further quantitative examination of relationships between each component of our theory would be valuable to understand the relationship between the constructs more thoroughly. Furthermore, pedagogical interventions, such as conducting a scholarship of teaching and learning focused on counselor education doctoral-level research courses, may be valuable in order to support their merit.

Limitations

Although we engaged in intentional practices to ensure trustworthiness throughout our study, there are limitations that should be considered. Specifically, all of the authors value and find research to be an important aspect of counselor education and participants self-selected to participate in the research study, which is common practice in most qualitative studies. However, self-selection may present bias in the findings because of the participants’ levels of interest in the topic of research. Additionally, participant selection was based on those who responded to the email and met the criteria; therefore, there was limited selection bias of the participants from the research team. Furthermore, participants were from a variety of programs and their year in their program (e.g., first year) varied; all the intricacies within each program cannot be accounted for and they may contribute to how the participants view research. Finally, the perceived hierarchy (i.e., faculty and students) on the research team may have contributed to the data analysis process by students adjusting their analysis based on faculty input.

Conclusion

In summary, our study examined CEDS’ experiences that helped build RI during their doctoral program. We interviewed 11 CEDS who were from eight CACREP-accredited doctoral programs from six different states and varied in the year of their program. Our grounded theory reflects the process-oriented nature of RI development and the influence of program design, research content knowledge, experiential learning, and self-efficacy on this process. Based on our findings, we emphasize the importance of mentorship and faculty conducting their own research as ways to model the research process. Additionally, our theory points to the need for increased funding for CEDS in order for them to be immersed in the experiential learning process and research courses being tailored to include topics specific to counselor education and supervision.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Archibald, M. (2015). Investigator triangulation: A collaborative strategy with potential for mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 10(3), 228–250.

Association for Assessment and Research in Counseling. (2019). About us. http://aarc-counseling.org/abo

ut-us

Borders, L. D., Gonzalez, L. M., Umstead, L. K., & Wester, K. L. (2019). New counselor educators’ scholarly productivity: Supportive and discouraging environments. Counselor Education and Supervision, 58(4), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12158

Borders, L. D., Wester, K. L., Fickling, M. J., & Adamson, N. A. (2014). Research training in CACREP-accredited doctoral programs. Counselor Education and Supervision, 53, 145–160.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2014.00054.x

Carlson, L. A., Portman, T. A. A., & Bartlett, J. R. (2006). Self-management of career development: Intentionality for counselor educators in training. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 45(2), 126–137.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2006.tb00012.x

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2016-Standards-with-citations.pdf

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Dollarhide, C. T., Gibson, D. M., & Moss, J. M. (2013). Professional identity development of counselor education doctoral students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 52(2), 137–150.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2013.00034.x

Gelso, C. J., Baumann, E. C., Chui, H. T., & Savela, A. E. (2013). The making of a scientist-psychotherapist: The research training environment and the psychotherapist. Psychotherapy, 50(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028257

Gibson, D. M., Dollarhide, C. T., & Moss, J. M. (2010). Professional identity development: A grounded theory of transformational tasks of new counselors. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2010.tb00106.x

Glesne, C. (2011). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction (4th ed.). Pearson.

Hays, D. G., & Wood, C. (2011). Infusing qualitative traditions in counseling research designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(3), 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00091.x

Heppner, P. P., Wampold, B. E., Owen, J., Thompson, M. N., & Wang, K. T. (2016). Research design in counseling (4th ed.). Cengage.

Hughes, F. R., & Kleist, D. M. (2005). First-semester experiences of counselor education doctoral students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 45(2), 97–108.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb00133.x

Jorgensen, M. F., & Duncan, K. (2015). A grounded theory of master’s-level counselor research identity. Counselor Education and Development, 54(1), 17–31.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2015.00067.x

Lamar, M. R., & Helm, H. M. (2017). Understanding the researcher identity development of counselor education and supervision doctoral students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 56(1), 2–18.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12056

Lambie, G. W., Ascher, D. L., Sivo, S. A., & Hayes, B. G. (2014). Counselor education doctoral program faculty members’ refereed article publications. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(3), 338–346. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00161.x

Mobley, K., & Wester, K. L. (2007). Evidence-based practices: Building a bridge between researchers and practitioners. Association for Counselor Education and Supervision.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250

Murray, C. E. (2009). Diffusion of innovation theory: A bridge for the research-practice gap in

counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87(1), 108–116.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00556.x

Ponterotto, J. G., & Grieger, I. (1999). Merging qualitative and quantitative perspectives in a research identity. In M. Kopala & L. A. Suzuki (Eds.), Using qualitative methods in psychology (pp. 49–62). SAGE.

Protivnak, J. J., & Foss, L. L. (2009). An exploration of themes that influence the counselor education doctoral student experience. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48(4), 239–256.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00078.x

Reisetter, M., Korcuska, J. S., Yexley, M., Bonds, D., Nikels, H., & McHenry, W. (2011). Counselor educators and qualitative research: Affirming a research identity. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2004.tb01856.x

Dodie Limberg, PhD, is an associate professor at the University of South Carolina. Therese Newton, NCC, is an assistant professor at Augusta University. Kimberly Nelson is an assistant professor at Fort Valley State University. Casey A. Barrio Minton, NCC, is a professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. John T. Super, NCC, LMFT, is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Central Florida. Jonathan Ohrt is an associate professor at the University of South Carolina. Correspondence may be addressed to Dodie Limberg, 265 Wardlaw College Main St., Columbia, SC 29201, dlimberg@sc.edu.

Dec 16, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 4

Cian L. Brown, Anthony J. Vajda, David D. Christian

We examined the publication trends of faculty in 396 CACREP-accredited counselor education and supervision (CES) programs based on Carnegie classification by exploring 5,250 publications over the last decade in 21 American Counseling Association and American Counseling Association division journals. Using Bayesian statistics, this study expounded upon existing literature and differences that exist between institution classifications and total publications. The results of this study can be used to inform the training and preparation of doctoral students in CES programs through a Happenstance Learning Theory framework, specifically regarding their role as scholars and researchers. We present implications and argue for the importance of programs and faculty providing research experience for doctoral students in order to promote career success and satisfaction.

Keywords: doctoral counselor education and supervision, Carnegie classification, Happenstance Learning Theory, publication trends, Bayesian statistics

Pursuing a doctoral degree in counselor education and supervision (CES) can be a daunting task. Although there are some levels of certainty, there is also a great degree of uncertainty, especially with regard to recognizing the valuable experiences that will inevitably lead to career opportunities, satisfaction, and success (Baker & Moore, 2015; Del Rio & Mieling, 2012; Dollarhide et al., 2013; Dunn & Kniess, 2019; Hinkle et al., 2014; Zeligman et al., 2015). CES doctoral students enrolled in programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) can expect to develop core areas of practice such as counseling, supervision, teaching, leadership and advocacy, and research and scholarship. Happenstance Learning Theory (HLT) provides a framework through which those planned and unplanned experiences—and the degrees of certainty and uncertainty—of doctoral students can be understood. For example, mentorship and career development throughout the course of the doctoral program impact students’ experiences (Kuo et al., 2017; Perera-Diltz & Duba Sauerheber, 2017; Protivnak & Foss, 2009; Purgason et al., 2016; Sackett et al., 2015). Previous research indicates that research and scholarship are highly emphasized factors for impacting career opportunities and success for potential and current CES faculty (Barrio Minton et al., 2008; Newhart et al., 2020). However, the exact requirements for publications and scholarship in CES remain unclear and often vary by institution and program (Davis et al., 2006; Lambie et al., 2014; Ramsey et al., 2002; Shropshire et al., 2015; Wester et al., 2013). In order to better understand potential implications for faculty, programs, and doctoral students looking to enter academia, researchers must continue exploring CES publication and scholarship trends.

Research and Scholarship in CES

Research and scholarly activity are a responsibility and priority among faculty in higher education in order to further inform the profession and promote productivity. Thus, “developing doctoral counselor education students’ research and scholarship competencies needs to be supported and nurtured in preparation programs where the faculty and systemic climate may promote these professional skills, dispositions, and behaviors” (Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011, p. 254). Although additional research is warranted, researchers have conducted several studies to better understand the landscape of publication trends among counselor educators and CES programs. To date, all prior studies have primarily relied on self-report surveys and have not examined longitudinal trends (Lambie et al., 2014; Newhart et al., 2020; Ramsey et al., 2002).

Ramsey et al. (2002) conducted survey research regarding the scholarly productivity of counselor educators at CACREP-accredited programs at the various levels of Carnegie classification from 1992 to 1995. Of the 104 programs they contacted, only 113 faculty at 47 institutions responded. According to their research, faculty at research and doctorate-granting institutions (the Carnegie classifications at the time) reported spending more time publishing journal articles than faculty at comprehensive institutions, while all CES faculty, regardless of their institution’s Carnegie classification, perceived journal articles as the most important form of scholarship for tenure/promotion decisions. Although Ramsey et al.’s research provides insight into the perceived role publications play for tenure/promotion, relying on self-reported publication patterns means it is impossible to know if their results are consistent with the actual publication trends for faculty of CES programs of various Carnegie classifications.

Lambie et al. (2014) accounted for this limitation by using online research platforms to identify publication trends of faculty at CACREP-accredited doctoral programs. Their research provided important information related to the publication process for counselor educators at doctoral-granting institutions but is limited in that their sample only consisted of 55 programs, whereas as of 2020, there were 85 CACREP-accredited doctoral programs. Lambie et al. (2014) emphasized the role of doctoral students and the necessity of mentorship in scholarly writing and publishing as outlined by CACREP standards. Through modeling and mentorship, counselor educators prepare doctoral students to transition into academic positions. The purpose of their study was to identify potential implications for supporting CES faculty and the career development of doctoral students (i.e., future counselor educators) by looking at the effects of faculty members’ academic rank, gender, Carnegie classification of current institution, and year doctoral degree was conferred on their rate of scholarly productivity over a 6-year time period. Between 2004 and 2009, counselor educators published a mean of 4.43 articles (Mdn = 3.0, SD = 4.77, range = 0–29 published articles) across 321 identified peer-reviewed journals. Lambie et al. (2014) further pointed out the variance in publication among CES faculty. Specifically, 20% of CES faculty published an average of 11.6 articles over the 6-year period, while 62% published an average of 3.02, and 16.1% did not publish any articles during this span of time. Their results also revealed a significant difference between the publication rates based on an institution’s Carnegie classification, where faculty at very high (R1) and high (R2) research activity institutions published significantly more than those at doctoral/professional universities. In addition, Lambie et al.’s (2014) finding that CES faculty who had more recently completed their doctoral degrees had the highest publication rates indicated programs are better preparing doctoral students to produce scholarly work. Their findings also implied that doctoral preparation programs can promote career readiness by implementing research competencies, such as scholarly writing and research mentorship, early in doctoral programs.

Newhart et al. (2020) similarly assessed publication rates among 257 counselor educators using a self-report survey across CACREP-accredited programs at various Carnegie classifications and academic ranks. Their stated purpose was to expand the current literature on CES publication rates using self-reported data to include non-tenured faculty and master’s-level–only programs. Their survey yielded a 17% response rate after randomly selecting 1,500 faculty members to participate. Respondents reported an average of 14.24 articles published or in press at the time of the survey, with an average of 1.69 publications per year. Carnegie classification appeared to be a significant predictor of publication rates across institutions, with faculty at more research-focused institutions publishing more often than faculty with lower research expectations. Similar to previous studies, results related to Carnegie classification appeared to underscore the emphasis certain programs place on publication standards, which can inform doctoral students’ decisions regarding which environments might be more suitable and conducive to their aspirations upon entering into academia. Although timely, Newhart et al.’s study has several limitations. There was no apparent time frame, leaving one to assume the reported information reflected participants’ total career publications, which could potentially skew the data. The 17% response rate for this study was another potential limitation, as it yielded responses from only 257 counselor educators with varying levels of experience. And as they highlighted, the use of self-report data may influence response bias and risk inflation of reported results based on desirability and bias.

Although previous researchers have asserted that doctoral-granting institutions are more likely to emphasize publishing (Barrio Minton et al., 2008; Lambie et al., 2014; Ramsey et al., 2002), research has yet to establish this as fact by comparing actual publication trends across a variety of institution types. Barrio Minton et al. (2008) began to address the differences when they called for future research to “examine publication trends and histories of counselor educators who are employed in programs in universities that are likely to place a high emphasis on publication” (p. 135) but failed to define, with certainty, the type of universities that emphasize publications. Despite the call for a revised definition of scholarship 17 years ago (Ramsey et al., 2002), scholarship is still heavily defined based on number of publications (Whitaker, 2018). These prior studies highlight the increased need for the use of observational data over a longitudinal period to verify self-reports and increase understanding of publication writing for the career development and mentorship of CES doctoral students.

Preparing CES Doctoral Students

Although the exact extent is unknown, research and scholarship are clearly important factors for employability as CES faculty as well as career satisfaction and success (Lambie et al., 2014; Sackett et al., 2015). Preparing CES doctoral students to be employable, happy, and successful in academia requires (a) understanding the extent to which research is required at various institutions and (b) ensuring they are exposed to the necessary curricula related to research (Lambie et al., 2008, 2014; Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011; Sackett et al., 2015). Although we aim to clarify research expectations, it is important to first establish a framework to guide CES programs and faculty. HLT is one such framework that emphasizes planned and unplanned experiences that influence career direction (Krumboltz, 2009). Using HLT, CES faculty and programs can provide better learning environments and mentorship experiences through leveraging planned and unplanned activities. From this lens, faculty encourage students to engage in planned experiences aligned with their career aspirations while also being open to potentially formative unplanned experiences, especially related to research and scholarship.

Happenstance Learning Theory (HLT)

According to HLT, career development is the result of numerous planned and unplanned experiences over the course of life in which people develop skills, interests, knowledge, beliefs, preferences, sensitivities, emotions, and behaviors guiding them toward a career (Krumboltz, 2009). The process of career development from an HLT perspective involves individuals “engaging in a variety of interesting and beneficial activities, ascertaining their reactions, remaining alert to alternative opportunities, and learning skills for succeeding in each new activity” (Krumboltz, 2009, p. 135). From an HLT stance, individuals must take five specific actions toward career development (Krumboltz, 2009). Initially, they must acknowledge anxiety toward career choice as normal and understand that the career development process as a long-term endeavor influenced by both planned and unplanned experiences. Next, it is important to allow identified concerns to be a starting point for further exploration. Third, they need to explore how past experiences with unplanned events have influenced current career interests and behaviors. Fourth, they should reframe unplanned experiences as opportunities for growth and learn to recognize these opportunities in their everyday lives. Finally, it is important that individuals remove or overcome any and all blocks to career-related action.

In an endeavor to explain career development and choice, HLT points to various planned and unplanned experiences throughout the life span (Krumboltz, 2009). Planned experiences include events individuals initiate such as pursuing a doctoral degree, choosing a particular CES program, identifying a focus of study, selecting courses as part of a program of study, and approaching specific faculty for advising and mentorship in an effort to achieve career aspirations. Unplanned experiences include events that individuals have no control over that often lead to revised career aspirations such as influential course instructors; type and quality of advising and mentoring; and various opportunities to teach, present, and publish with program faculty. Even though “the interaction of planned and unplanned actions in response to self-initiated and circumstantial situations is so complex that the consequences are virtually unpredictable and can best be labeled as happenstance” (Krumboltz, 2009, p. 136), unplanned experiences are particularly important to HLT. In fact, it is important that individuals take advantage of these unplanned experiences as opportunities to grow—something they are less likely to do if their predetermined career aspirations are too rigid (Gysbers et al., 2014).

For CES doctoral students, HLT is particularly pertinent in that although many enter programs with clear career aspirations, these career goals often remain fluid, changing and developing through planned and unplanned experiences throughout the training process. Although this drive to reach predetermined goals can serve as motivation, individuals who have made firm career decisions tend to focus on experiences that affirm their choices and overlook or fail to engage in unplanned experiences not related to their career goals (Gysbers et al., 2014). Thus, it is important that CES faculty not only encourage doctoral students to be open minded about potential career outcomes, but also provide opportunities for doctoral students to engage in formative unplanned experiences.

Although CACREP provides specific mandatory standards that must be accounted for, they allow programs to exercise flexibility and creativity in how they address them (CACREP, 2015; Goodrich et al., 2011). Students can expect a specific knowledge base but also have opportunities for paving their own career path because of the uniqueness of each CES program and other factors such as pre-enrollment career aspirations, unplanned life events, challenges or successes in courses, program emphasis, and mentorship. Both planned and unplanned experiences involve facing challenges, leading to developmental and transformational tasks that influence the integration of multiple identities, self-efficacy, and acceptance of responsibility as a leader in the counseling profession (Dollarhide et al., 2013). From an HLT framework, these transformational tasks are particularly significant, as they can be the catalyst for revised career aspirations or the reinforcement of previously determined career goals. This highlights the importance of advising and mentoring, and the need for ample opportunities for students to engage in diverse experiences so that these transformations can occur.

Planned Experiences

Doctoral students in CACREP-accredited CES programs can expect planned experiences relating to coursework that integrates theories relevant to counseling, the skills and modalities of clinical supervision, pedagogy and teaching methods related to educating counselors, research designs and professional writing, and leadership skills. Although CES programs are designed to provide planned experiences related to all of the roles of a counselor educator (CACREP, 2015), the emphasis placed on each varies depending on the program and institution. CES faculty prepare doctoral students for a future in teaching, research, and service, often through experiences co-instructing counselors-in-training, scholarly work, and leadership roles advocating for the profession (Protivnak & Foss, 2009; Sears & Davis, 2003).

CACREP (2015) standards require that doctoral students learn research design, data analysis, program evaluation, and instrument design; however, there are not strict requirements or guidelines indicating what scholarly activities must be experienced before students graduate. Research experience is considered important because future CES faculty will likely be expected to engage in scholarship of some form, including writing journal articles, presenting at conferences, conducting program evaluations, and preparing other scholarly works such as grants and training manuals. However, after finding that less than a third of CES doctoral students had published a scholarly article, Lambie and Vaccaro (2011) concluded that CES programs must provide more planned experiences for student research engagement. Finally, because doctoral students inevitably learn valuable lessons in research and scholarship through the planned experience of completing a dissertation, CES programs must provide adequate training for students to successfully complete this milestone (Lambie et al., 2008).

Unplanned Experiences

CES doctoral students also have various opportunities for unplanned learning experiences with research and scholarship through coursework and collaboration with peers and faculty. Unplanned experiences that appear to be particularly important for CES doctoral students often occur through mentoring (Kuo et al., 2017; Perera-Diltz & Duba Sauerheber, 2017; Protivnak & Foss, 2009; Purgason et al., 2016; Sackett et al., 2015). Mentorship experiences include relationships with advisors and dissertation chairs, work beyond the classroom setting with faculty mentors, and relationships with counselor educators from other universities or institutions. Kahn (2001) posited that research-specific mentoring and collaborative research projects can create an environment conducive for CES doctoral students to develop research skills by observing faculty.

Several studies have highlighted the importance of mentorship in the career development of CES students (Casto et al., 2005; Cusworth, 2001; Hoskins & Goldberg, 2005; Nelson et al., 2006; Protivnak & Foss, 2009). Protivnak and Foss (2009) interviewed 141 current CES doctoral students who stressed the helpfulness of mentorship while navigating their doctoral program but also discussed the consequences of a lack of mentorship and support. Participants who received mentorship stated that it helped with balance and guidance in the program, while participants without adequate mentorship shared feelings of frustration and being on their own. Further, Love et al. (2007) found that research mentoring was a predictor of whether or not CES doctoral students became involved in research projects.

CES Program Characteristics Influencing Engagement in Research Experiences

All of these research experiences, both planned and unplanned, will vary across programs and depend on a multitude of factors, one of which might be the Carnegie classification of the institution where the program is housed. Carnegie classification divides colleges and universities that house CES programs into several categories, including the following: doctoral universities, master’s colleges and universities, baccalaureate colleges, and special focus institutions. Doctoral universities are further classified based on a measure of research activity into one of three levels: R1, for very high research activity; R2, for high research activity; and D/PU (doctoral/professional universities), for moderate research activity. If previous literature indicating that doctoral-granting institutions are more likely to emphasize publishing and produce more publications (Barrio Minton et al., 2008; Lambie et al., 2014; Ramsey et al., 2002) is accurate, then this might impact doctoral students’ career aspirations as well as exposure to and engagement in research-related experiences.

According to HLT, CES doctoral students’ career aspirations can influence how they engage in certain planned experiences and if they choose to engage in certain unplanned experiences (Krumboltz, 2009). For example, a student focused on a career at an institution with less emphasis on research (e.g., master’s university) may put forth minimal effort in research courses and opt out of any unplanned experiences related to scholarly activity, such as accepting an invitation to join a research team. Also, it is possible that CES doctoral students at R1, R2, and D/PU institutions might have varying exposure to opportunities to engage in unplanned experiences related to research and scholarship if faculty at those institutions are spending less time in the role of researcher. For instance, Goodrich et al. (2011) found that in a survey of 16 CACREP-accredited counseling programs, only six programs had established research teams and only four programs required students to submit scholarly work to a professional journal before they could graduate.

Purpose

This study was designed to explore the current trends in publication rates of faculty in CES programs over a 10-year time period. Using a Bayesian analysis, we examined the following questions:

- Research Question 1: What are the differences among CES programs’ faculty publication rates based on all Carnegie classifications?

o Research Question 1.a: Are there differences among master’s-level programs based on Carnegie classifications in terms of faculty publication rates?

- Research Question 2: Does observable data support prior literature findings regarding publication trends among CES programs at institutions with different levels of Carnegie classification?

Bayesian analysis is appropriate when “one can incorporate (un)certainty about a parameter and update his knowledge through the prior distribution” of probabilities (Depaoli & van de Schoot, 2017, p. 4). The inferences made by Newhart et al. (2020) were used as prior information to inform the collected observational data for this study. Newhart et al. used self-reported survey data to run a Poisson regression with the same variables proposed for this study. However, their data focused primarily on the differences among research institutions and combined non–research-designated institutions (i.e., master’s universities) into a single category. Newhart et al.’s output helped inform the limitations of the observational data collection procedures, such as error in using database search engines. Additionally, this is the first known study to examine observational data of publication trends for CES programs, which might provide an under- or overestimation when compared to self-reported data. Alternatively, the use of self-reported data has often been stated as a limitation because of participant bias, which might inflate the outcomes. Therefore, it would be helpful to compare inferences from both sets of data. An initial comparison of parameter estimates between both studies will inform the trends of publications between Carnegie classifications.

For this study, and similar to Newhart et al. (2020), Carnegie classification operated as the predictor variable and number of publications as the outcome variable. The results of the comparison and Bayesian hypothesis testing of data will provide a means to verify self-reported data trends between Carnegie classification using parameter estimates and further information regarding the scholarly productivity over a 10-year period and insight toward publication trends among non–PhD-level institutions using the posterior distributions.

Method

In order to answer the research questions, a list of all CACREP-accredited counseling programs in the United States was compiled by the principal investigator using the CACREP website directory. Next, a list of peer-reviewed journals affiliated with the American Counseling Association (ACA) was created. All journals were included, regardless of whether they published during the entire 10-year time period. Database search engines (e.g., EBSCO Academic Search Complete) and publisher websites were used as the primary tools to locate all articles published in every identified journal during the specific time period. After articles were secured, a database was created where authors’ associated institutions at the time of publication were indexed. At least one author for each publication was associated with a CACREP-accredited counseling program, an inclusion criterion for this study. Thus, if an article was authored by two faculty at two different CACREP-accredited programs, both institutions received credit for that publication. Finally, each institution’s most recent Carnegie classification was identified. A total of 5,250 publications authored by faculty at 396 institutions with CACREP-accredited programs were included in the analysis. The total number of publications accounts for articles with multiple authors from different institutions, with potentially different Carnegie classifications, being counted more than once. For example, an article authored by two faculty, one from an R1 institution and one from an M1, was counted as two publications. The rationale for this was that each institution listed on any given article would receive credit for this publication. R1 programs accounted for 37.68% (M = 33.53) and R2 accounted for 31.37% (M = 25.34) of publications in ACA-affiliated journals (see Table 1 for a detailed breakdown of institution and publications in ACA-affiliated journals).

Table 1

Breakdown of Observed Data of Total Publications by Carnegie Classification

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total Publications |

| Carnegie Classification |

|

# of Programs |

|

% |

|

# of Pubs |

|

% |

|

Mean |

|

SD |

|

Var |

| R1—Very High Research Activity |

|

59 |

|

14.86 |

|

1,978 |

|

37.68 |

|

33.53 |

|

30.53 |

|

932.05 |

| R2—High Research Activity |

|

65 |

|

16.37 |

|

1,647 |

|

31.37 |

|

25.34 |

|

28.29 |

|

800.45 |

| D/PU—Doctoral/Professional Universities |

71 |

|

17.88 |

|

652 |

|

12.42 |

|

9.18 |

|

13.36 |

|

178.52 |

| M1—Larger Master’s Program |

|

116 |

|

29.47 |

|

802 |

|

15.28 |

|

6.91 |

|

9.71 |

|

93.90 |

| M2—Medium Master’s Program |

|

43 |

|

10.83 |

|

105 |

|

2.00 |

|

2.44 |

|

3.14 |

|

9.87 |

| M3—Smaller Master’s Program |

|

13 |

|

3.27 |

|

20 |

|

0.38 |

|

1.54 |

|

2.30 |

|

5.27 |

| Bacc.—Baccalaureate Colleges |

|

9 |

|

2.27 |

|

9 |

|

0.17 |

|

1.00 |

|

1.32 |

|

1.75 |

| SF—Special Focus Institutions |

|

20 |

|

5.04 |

|

37 |

|

0.70 |

|

1.85 |

|

2.56 |

|

6.56 |

| Total |

|

|

|

|

396 |

|

|

|

5250 |

|

|

|

13.26 |

|

21.32 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. This table provides the descriptive statistics for programs and publications by Carnegie classification. Only CACREP-accredited programs were included.

Data Analysis

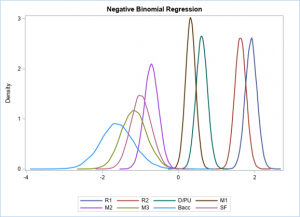

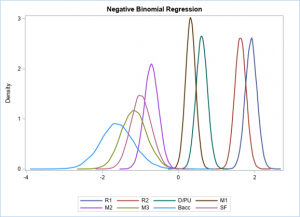

Following the data collection, the observed data was entered into and analyzed using SAS statistical software system to run the Markov chain Monte Carlo procedure with the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm to generate the estimated models. A Bayesian theoretical approach was taken to use prior information elicited from Newhart et al.’s (2020) publication, “Factors Influencing Publication Rates Among Counselor Educators.” It was determined that a Poisson regression analysis was appropriate for determining the relationship between a predictor variable and an outcome variable characterized in the form of a frequency count. One assumption of Poisson models is that the mean and the variance are equal (homogeneity of conditional means). If this assumption is violated, a negative binomial model can account for a large difference between the variance and mean by estimating a dispersion parameter (Agresti, 2007). The test for the assumption of equal conditional mean and variance was violated, indicating overdispersion. Overdispersion occurs when the data has greater variability. The following negative binomial model was used to run a negative binomial regression (where D is the dispersion parameter): E(Y) = μ, Var(Y) = μ+Dμ2.

Next, the self-reported data collected from Newhart et al. (2020) was used to determine prior information to distinguish the differences between Carnegie classification and publication rates using R1 institutions as a baseline (see Table 2). The logarithm of the ratio was used for the prior mean of the distribution.

Table 2

Newhart et al. (2020) Self-Reported Total Publications by Carnegie Classification

|

|

|

|

Total Publications |

| Carnegie Classification |

|

M |

|

SD |

|

Ratio |

| R1: Doctoral Universities – Very High |

|

25.78 |

|

26.15 |

|

– |

| R2: Doctoral Universities – High |

|

19.74 |

|

18.53 |

|

0.766 |

| D/PU: Doctoral/Professional Universities – Moderate |

|

13.31 |

|

14.78 |

|

0.516 |

| Master’s Universities |

|

7.98 |

|

7.46 |

|

0.309 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. Ratio reflects multiplicative factor in relation to baseline R1.

Results

A negative binomial regression was used to (a) determine what the posterior probability publishing rates of non-R1 programs were compared to programs at R1 institutions and (b) examine if Newhart et al.’s (2020) self-reported data was plausible given the observed data. An initial model contained 10,000 burn-ins with a total of 100,000 iterations; however, this model lacked efficient information as determined by the effective sample size and efficiency. Next, Gibbs sampling with the Jeffreys prior was used and produced similar posterior parameter estimates and increased efficiency, indicating robustness; however, the effective sample size did not increase. Therefore, a sum-to-zero constraint was used to re-parametrize the model by centering the parameters. This resulted in coefficients representing group deviations from the grand mean, where in prior models the coefficients represented group deviations from the reference group. The following results are reported using the WAMBS checklist procedure for reporting Bayesian statistical results (Depaoli & van de Schoot, 2017). The WAMBS checklist consists of four stages and 10 points to appropriately understand, interpret, and provide results of Bayesian statistics. The following paragraph outlines these 10 steps as applied to the current data.