Dec 15, 2014 | Video Reviews

Overall, the Clinical Interviewing: Intake, Assessment, and Therapeutic Alliance video is a great product and I would recommend it to my students and colleagues. The video is associated with a textbook titled Clinical Interviewing (Wiley, 2014) and written by the video presenters, Professors John and Rita Sommers-Flanagan. The professors begin with basic interview skills and end with complex interviewing skills. The basic interview skills consist of the following: nondirective listening behaviors (i.e. Ivey’s attending behaviors) and responses, directive listening and action responses, and questions. Nondirective listening behaviors include the following: eye contact, body posture, voice tone and verbal tracking; and nondirective listening responses consist of the following: silence, clarification, paraphrasing, reflection of feeling and summarization. In contrast, directive listening and action responses include feeling validation, interpretive reflection of feeling, interpretation, reframe and confrontation. And the types of questions included are open, closed, indirect, swing, projective and therapeutic. The complex interviewing skills explained are intake assessment, mental status examination and suicide assessment. The professors provide lengthy demonstrations of how to complete a mental status examination and suicide assessment, which give the audience a good idea of how these assessments should be conducted.

Overall, the Clinical Interviewing: Intake, Assessment, and Therapeutic Alliance video is a great product and I would recommend it to my students and colleagues. The video is associated with a textbook titled Clinical Interviewing (Wiley, 2014) and written by the video presenters, Professors John and Rita Sommers-Flanagan. The professors begin with basic interview skills and end with complex interviewing skills. The basic interview skills consist of the following: nondirective listening behaviors (i.e. Ivey’s attending behaviors) and responses, directive listening and action responses, and questions. Nondirective listening behaviors include the following: eye contact, body posture, voice tone and verbal tracking; and nondirective listening responses consist of the following: silence, clarification, paraphrasing, reflection of feeling and summarization. In contrast, directive listening and action responses include feeling validation, interpretive reflection of feeling, interpretation, reframe and confrontation. And the types of questions included are open, closed, indirect, swing, projective and therapeutic. The complex interviewing skills explained are intake assessment, mental status examination and suicide assessment. The professors provide lengthy demonstrations of how to complete a mental status examination and suicide assessment, which give the audience a good idea of how these assessments should be conducted.

This video has a number of strengths. The material is presented developmentally, from basic interviewing skills to complex interviewing skills. The video features an option of viewing the entire presentation or selecting specific chapters that correspond with the clinical skills covered in the video. The chapters are well organized and all use the following format: (a) an introduction to the clinical skills to be covered in that chapter, (b) a brief lecture on those skills and how they are incorporated into sessions, (c) a clip of an actual session during which the counselor demonstrates the use of the skills, and (d) a debriefing of the session by the presenters, at which time they discuss the things that were done well and things that could have been done differently. In addition, at the beginning of each chapter the professors summarize the skills covered in previous chapter(s). The video also comes with a manual that provides an overview of the video and additional activities that can be completed along with it.

During the introduction to the video, Professors John and Rita Sommers-Flanagan stress the importance of being culturally aware of and sensitive to each individual client’s needs, and using one’s best clinical judgment when utilizing clinical interviewing skills. The importance of being culturally sensitive is stressed several times throughout the video. The professors also incorporate PowerPoint slides into the video, which are very helpful because the slides highlight key points that are discussed in each chapter prior to the demonstration of the clinical skills. In addition, during the demonstration sessions, whenever the counselor uses specific skills, the skills are identified at the bottom of the screen.

As previously stated, overall this video is a great resource; however, there are a couple of limitations worth noting. The material is presented from a limited client perspective in that the professors only focus on individual adult clients. During the brief lectures and discussions about different clinical skills, the professors do not mention how the skills might look different when used with couples, families, adolescents, older adults, etc. The presenters mainly focus on how a client’s culture influences the counseling process; they do not highlight the ways that different modalities and client characteristics might affect how clinical skills are implemented during a session. Furthermore, the feature of displaying which skills the counselors are using is both a strength and limitation; the limitation is the lack of an option to manipulate this function (turn it on/off). Providing the ability for an instructor to manipulate this function would offer him or her more options for classroom activities.

The video is structured for both instructional and independent use, so it can be used by counseling professionals. Counselor educators and other mental health educators can incorporate the video into their courses by showing the video in class or making it available for students to access outside class. Furthermore, professional counselors can use the video to independently to strengthen their clinical interviewing skills.

Reviewed by: Olivia Uwamahoro, NCC, doctoral candidate in counselor education, University of Central Florida, Orlando, Florida.

Irish Luck Productions (Producer), & Sommers-Flanagan, J., & Sommers-Flanagan, R. (Directors). (2014). Clinical interviewing: Intake, assessment, and therapeutic alliance with John Sommers-Flanagan, PhD and Rita Sommers-Flanagan, PhD [DVD]. (Available in DVD and video streaming from http://www.psychotherapy.net/video/clinical-interview-intake-assessment-training)

Available in DVD and streaming format as part of video subscription at Psychotherapy.net/subscriptions.

The Professional Counselor

https://tpcwordpress.azurewebsites.net

Dec 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 5

Traci P. Collins

School counselors are a well-positioned resource to reach the significant number of children and adolescents with mental health problems. In this special school counseling issue of The Professional Counselor, some articles focus on systemic, top-down advocacy efforts as the point of intervention for addressing child and adolescent mental health. Other articles investigate improving child and adolescent mental health through a localized, ground-level approach by developing school counselors’ competency areas and specific school counseling interventions. Article topics include school counselors’ professional identity, training, self-efficacy, supervision, burnout, career competencies and cultural competencies, as well as how to measure the impact of school counselors’ interventions. The author discusses the importance of school counselors’ role within schools, and hindrances to school counselors’ ability to perform their role as counselors.

Keywords: school counselors, professional identity, role, competencies

A significant number of children and adolescents experience mental health problems in the United States. Between 13% and 20% of children experience a mental disorder in a given year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Because school counselors have access to these students with mental illness in our nation’s school systems, they are a well-positioned resource. School counselors improve the mental health of children and adolescents, thereby improving the students’ overall functioning, personal/social development, career development and educational success. Students need mental health services; however, confusion exists as to how to utilize their most easily operationalized resource—school counselors (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006).

Overview of the Special Issue

In order to improve child and adolescent mental health and the efficiency of mental health services, the function of school counselors within the school system must be examined. I am pleased to introduce this special issue of The Professional Counselor focusing on school counseling. The collection of articles combines systemic, theoretical explorations with assessments of school counselor preparation and competencies. Some articles focus on the point of intervention (i.e., place for needed improvement and change) as systemic, top-down advocacy efforts. Other articles cover school counselor training, self-efficacy, supervision, and burnout versus career sustainability. A few articles in this special issue investigate improving child and adolescent mental health through a localized, ground-level approach by developing school counselors’ competency areas and specific school counseling interventions.

School Counselor Professional Identity

Over the last 100 years, school counseling has evolved from vocational guidance to the current concept of comprehensive school counseling. The first article in this special issue provides a historical perspective, describing the progression of school counselor professional identity (Cinotti, 2014). Cinotti (2014) discusses the conflicting professional identities (educator and counselor) that school counselors have experienced for the last century and the effects of role ambiguity concerning the utilization of school counselors and the assignment of duties. School counselors receive conflicting obligations and messages from counselor educators, school administrators and other stakeholders. However, research has found that among usual school counselor duties, direct counseling services are the most unique role of school counselors (Astramovich, Hoskins, Gutierrez, & Bartlett, 2014). Counseling services are often underutilized.

Bardhoshi, Schweinle, and Duncan (2014) explore school counselor professional identity on a more practical level by examining the impact of school-specific factors on school counselor burnout. The authors describe a mixed-methods study that expands on previous research indicating that role conflict is related to burnout in school counselors (Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006) and examine organizational factors such as student caseload. Bardhoshi et al. include a telling statement from a study participant who shared, “When we are allowed to focus on the social and emotional needs of the whole child, we are best positioned to clear away the barriers to academic achievement” (p. 434). These authors emphasize the importance of comprehensive training in school counselor programs and counselor educator advocacy efforts.

In a third article involving school counselor professional identity, Duncan, Brown-Rice, and Bardhoshi (2014) describe the ways that inadequate supervision for school counselors contributes further to disordered professional identity development and insufficient support for school counselors. Appropriate clinical supervision provides professional identity development, proficiency in ethics and improved clinical abilities. However, school counselors often receive only administrative supervision conducted by noncounselors, and rural school counselors face additional challenges in seeking clinical supervision (Duncan, Brown-Rice, & Bardhoshi, 2014).

School Counselor Training

In 2012, the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) published the third edition of The ASCA National Model: A Framework for School Counseling Programs, which contains the following four elements for comprehensive school counseling programs: foundation, delivery system, management and accountability. In this special issue, Martin and Carey (2014) describe their examination of the National Model and subsequent development of a logic model for use in evaluating the success of the National Model. They suggest that future research could examine the outputs and outcomes outlined in their logic model before and after implementation of the National Model. Assessing school counselor preparation and student change provides insight into the effectiveness of the current guidelines for school counselor training.

After completing their graduate program, school counselors must apply knowledge associated with professional identity, ethical practice and sound counseling interventions. Schiele, Weist, Youngstrom, Stephan, and Lever (2014) present their research on counselor self-efficacy and performance when working with students in schools, focusing on the impact of counselor self-efficacy on the quality of counseling services and knowledge of evidence-based practices. Relatedly, Schiele et al. found that counselor self-efficacy plays an important role in the effective assessment and treatment of students’ mental health needs.

Career Counseling Competencies. Morgan, Greenwaldt, and Gosselin (2014) studied school counselor perceptions of competency in career counseling, also comparing Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) counselor preparation versus non-CACREP preparation. Their participants, practicing school counselors, consistently shared feelings of incompetence and inadequacy in their ability to provide sound career development programming to their students. The results of this study indicate that feelings of unpreparedness upon leaving graduate school, along with feelings of incompetency, significantly impact school counselors’ ability to address the needs of their students.

Cultural Competencies. Several articles in this special school counseling issue examine school counseling interventions or approaches for working with diverse populations. A 2010 Department of Defense report revealed that approximately 1.85 million children have at least one parent serving in the U.S. military (see Ruff & Keim, 2014). In this issue, Cole (2014) provides a guide for working with children from military culture. Culturally competent school counselors must be knowledgeable about the unique complexities of this population, along with other culturally distinctive populations. Van Velsor and Thakore-Dunlap (2014) describe working with South Asian immigrant adolescents in a group counseling format. Additionally, Shi, Liu, and Leuwerke (2014) offer insights into Chinese culture in their study examining students’ perceptions of school counselors in Beijing.

While the aforementioned articles discuss students from certain cultural groups, this special issue of The Professional Counselor also provides an article about a specific population of U.S. students—those in need of anger management. Although anger is a common emotion experienced by both females and males (Karreman & Bekker, 2012), Burt and Butler (2011) noted that most anger management groups are gender biased, focusing excessively on adolescent males. In this special issue, Burt (2014) describes his investigation of gender differences in anger expression and anger control in adolescent middle school students, providing a foundation for practical applications and future research.

Concluding Comments

School counselors are well positioned within the school system to provide short-term clinical-based interventions to improve child and adolescent mental health. Proper identification, evaluation, and treatment of child and adolescent mental illness contribute to students’ well-being, productivity and success in various areas of their lives (National Institute of Mental Health, 1999), including academic success. With student academic achievement receiving national attention, school counselors have been challenged to provide interventions that contribute to increased student achievement (ASCA, 2005). Villares et al. (2014) continue this initiative by establishing the validity of an assessment tool that can be used to measure the impact of school counselor-led interventions on student achievement. Outcome research can be useful in responding to the systemic concerns regarding school counselor professional identity and role within the schools. When counselors stay true to their roots—as counselors first and educators second—they are in the most useful position to improve student achievement by first fighting the war on student mental health.

Ninety years ago, Myers (1924) warned about interferences that would prevent the “real work of a counselor” from occurring (p. 141). This 90-year-old forecast echoes today, as contemporary school counselors need support in receiving robust training and preparation in professional identity and competencies, resolving administrative and systemic issues, and obtaining efficient supervision to guide the course of the counseling profession in the school system.

References

American School Counselor Association. (2005). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

American School Counselor Association. (2012). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

Astramovich, R. L., Hoskins, W. J., Gutierrez, A. P., & Bartlett, K. A. (2014). Identifying role diffusion in school counseling. The Professional Counselor, 3, 175–184. doi:10.15241/rla.3.3.175

Bardhoshi, G., Schweinle, A., & Duncan, K. (2014). Understanding the impact of school factors on school counselor burnout: A mixed-methods study. The Professional Counselor, 4, 426–443. doi:10.15241/gb.4.5.426

Burt, I. (2014). Identifying gender differences in male and female anger among an adolescent population. The Professional Counselor, 4, 531–540.doi:10.15241/ib.4.5.531

Burt, I., & Butler, S. K. (2011). Capoeira as a clinical intervention: Addressing adolescent aggression with Brazilian martial arts. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 39, 48–57. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2011.tb00139.x

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2005–2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(2), 1–35. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6202a1.htm?s_cid=su6202a1_w

Cinotti, D. (2014). Competing professional identity models in school counseling: A historical perspective and commentary. The Professional Counselor, 4, 417–425. doi:10.15241/dc.4.5.417

Cole, R. F. (2014). Understanding military culture: A guide for professional school counselors. The Professional Counselor, 4, 497–504. doi:10.15241/rfc.4.5.497

Duncan, K., Brown-Rice, K., & Bardhoshi, G. (2014). Perceptions of the importance and utilization of clinical supervision among certified rural school counselors. The Professional Counselor, 4, 444–454. doi:10.15241/kd.4.5.444

Gysbers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2006). Developing & managing your school guidance and counseling program (4th ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Karreman, A., & Bekker, M. H. J. (2012). Feeling angry and acting angry: Different effects of autonomy-connectedness in boys and girls. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 407–415. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.07.016

Martin, I., & Carey, J. (2014). Development of a logic model to guide evaluations of the ASCA national model for school counseling programs. The Professional Counselor, 4, 455–466. doi:10.15241/im.4.5.455

Morgan, L. W., Greenwaldt, M. E., & Gosselin, K. P. (2014). School counselors’ perceptions of competency in career counseling. The Professional Counselor, 4, 481–496. doi:10.15241/lwm.4.5.481

Myers, G. E. (1924). A critical review of present developments in vocational guidance with special reference to future prospects. The Vocational Guidance Magazine, 2, 139–142. doi:10.1002/j.2164-5884.1924.tb00721.x

National Institute of Mental Health. (1999). Facts on children’s mental health in America. Retrieved from http://www.nami.org/Template.cfm?Section=federal_and_state_policy_legislation&template=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=43804

Ruff, S. B., & Keim, M. A. (2014). Revolving doors: The impact of multiple school transitions on military children. The Professional Counselor, 4, 103–113. doi:10.15241/sbr.4.2.103

Schiele, B. E., Weist, M. D., Youngstrom, E. A., Stephan, S. H., & Lever, N. A. (2014). Counseling self-efficacy, quality of services and knowledge of evidence-based practices in school mental health. The Professional Counselor, 4, 467–480. doi:10.15241/bes.4.5.467

Shi, Q., Liu, X., & Leuwerke, W. (2014). Students’ perceptions of school counselors: An investigation of two high schools in Beijing, China. The Professional Counselor, 4, 519–530. doi:10.15241/qs.4.5.519

Van Velsor, P., & Thakore-Dunlap, U. (2014). Group counseling with South Asian immigrant high school girls: Reflections and commentary of a group facilitator. The Professional Counselor, 4, 505–518. doi:10.15241/pvv.4.5.505

Villares, E., Colvin, K., Carey, J., Webb, L., Brigman, G., & Harrington, K. (2014). The convergent and divergent validity of the Student Engagement in School Success Skills Survey. The Professional Counselor, 4, 541–553. doi:10.15241/ev.4.5.541

Wilkerson, K., & Bellini, J. (2006). Intrapersonal and organizational factors associated with burnout among school counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84, 440–450. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb00428.x

Traci P. Collins, NCC, is the Managing Editor of The Professional Counselor and a doctoral student at North Carolina State University. Correspondence can be addressed to: Traci P. Collins, The Professional Counselor, National Board for Certified Counselors, 3 Terrace Way, Greensboro, NC 27403-3660, tcollins@nbcc.org.

Dec 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 5

Daniel Cinotti

Recent research has focused on the discrepancy between school counselors’ preferred roles and their actual functions. Reasons for this discrepancy range from administrators’ misperceptions of the role of the school counselor to the slow adoption of comprehensive school counseling approaches such as the American School Counselor Association’s National Model. A look at counseling history reveals that competing professional identity models within the profession have inhibited the standardization of school counseling practice and supervision. School counselors are counseling professionals working within an educational setting, and therefore they receive messages about their role as both counselor and educator. The present article includes a discussion of the consequences of these competing and often conflicting messages, as well as a description of three strategies to combat the role stress associated with this ongoing debate.

Keywords: school counseling, counseling history, professional identity, supervision, educational setting

The profession of school counseling has existed for more than 100 years, and throughout that time, competing professional identity constructs have impacted the roles, responsibilities and supervision of school counselors. Since the inception of school counseling, when it was known as vocational guidance, confusion has existed on how best to use and manage the resource that is the school counselor (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006; Pope, 2009). Although the focus of the profession has changed from vocational guidance to the current concept of comprehensive school counseling, problems surrounding the use and supervision of school counselors persist. Today, although the profession has identified a National Model (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2012) that provides an example of a comprehensive programmatic approach, many practicing school counselors and administrators continue to work with outdated service models and reactive approaches (Hatch & Chen-Hayes, 2008; Lambie & Williamson, 2004). A look at the historical roots of school counseling provides insight into the lasting problems for school counselor utilization and supervision.

Historical Context of School Counselor Practice

At the outset of the school counseling profession, the role of vocational guidance slowly became recognized as an integral ingredient in effective vocational placement and training. With the creation of the National Vocational Guidance Association in 1913, and the proliferation of vocational guidance programs in cities such as Boston and New York, the profession rapidly expanded (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). Concerns over the lack of standardized duties, centralized supervision and evaluation of services soon followed. As Myers (1924) pointed out in a historic article titled “A Critical Review of Present Developments in Vocational Guidance with Special Reference to Future Prospects,” vocational guidance was quickly being recognized as “a specialized educational function requiring special natural qualifications and special training” (p. 139, emphasis in original). However, vocational guidance was mostly being performed by teachers in addition to their other duties, with very few schools hiring specialized personnel. Although Myers (1924) and others expressed concerns over the lack of training and supervision, educators and administrators were slow to recognize the consequences of asking teachers to perform such vital duties in addition to their teaching responsibilities without proper training and extra compensation. Additionally, districts in which specific individuals were hired as vocational guidance professionals soon overloaded these professionals with administrative and clerical duties, which inhibited their effectiveness. Myers (1924) highlighted the situation as follows:

Another tendency dangerous to the cause of vocational guidance is the tendency to load the vocational counselor with so many duties foreign to the office that little real counseling can be done. . . . If well chosen he [or she] has administrative ability. It is perfectly natural, therefore, for the principal to assign one administrative duty after another to the counselor until he [or she] becomes practically assistant principal, with little time for the real work of a counselor. In order to prevent this tendency from crippling seriously the vocational guidance program it is important that the counselor shall be well trained, that the principal shall understand more clearly what counseling involves, and that there shall be efficient supervision from a central office. (p. 141)

In 1913, Jesse B. Davis introduced a vocational guidance curriculum to be infused into English classes in middle and high schools, an idea which he presented at the first national conference on vocational guidance in Grand Rapids, Michigan (Pope, 2009). It was summarily rejected by his colleagues, who would not embrace the idea of a guidance curriculum within the classroom. Slowly, however, as the profession grew and Davis and others gained respect and notoriety throughout the country, his “Grand Rapids Plan” gained support. Though Davis did not expect it, his model sparked debate between those who envisioned the expansion of counselor responsibilities and those who wished to maintain counselors’ primary duty as vocational guidance professionals (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). Ultimately, the heart of this debate was the role of vocational guidance as a supplemental service to the learning in the classroom or a distinctive set of services with a different goal than simply educating students. Although no definitive answer was agreed upon at the time, the realization that academic factors influence career choice and vice versa has helped to move the profession from a systemic approach of strictly vocational guidance to a comprehensive approach in which career, academic and personal/social development are all addressed (ASCA, 2003). The disagreement over Davis’s Grand Rapids Plan launched a debate between competing professional identity models that continues in the profession to this day.

Competing Professional Identity Models: Educator or Counselor?

Even during the time of vocational guidance in which the counseling profession’s singular purpose was to prepare students for the world of work, disagreement over the best way to perform this duty existed. As the profession began to define itself during the 1930s and ’40s, school administrators heavily determined the professional responsibilities of the school counselor (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). When the profession expanded to include personal adjustment counseling as a reaction to the growing popularity of psychology, administrators reacted by expanding vocational guidance to include a more educational focus. During the 1950s, school counselors were placed under the umbrella term pupil personnel services along with the school psychologist, social worker, nurse or health officer, and attendance officer. Although the primary role of the school counselor throughout the ’60s and ’70s was to provide counseling services, concerns over the perception of the profession existed. As a result of the lack of defined school counselor roles and responsibilities, the position was still seen as an ancillary support service to teachers and administrators. It was therefore extremely easy for administrators to continue to add to the counselor’s responsibilities as they saw fit (Lambie & Williamson, 2004), aligning school counselor duties with their own identity as educators.

The 1970s brought about the beginning of school counseling as a comprehensive, developmental program. Some within the profession attempted to create comprehensive approaches, which included goals and objectives, activities or interventions to address them, planning and implementation strategies, and evaluative measures. It was the first time that school counseling was defined in terms of developmentally appropriate, measurable student outcomes (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). However, environmental and economic factors slowed the adoption of this new concept. The 1970s were a decade of decreasing student enrollment and budgetary reductions, which led to cutbacks in counselor positions (Lambie & Williamson, 2004). As a result, counselors began to take on more administrative duties either out of necessity or a desire to become more visible and increase the perception of the school counselor position as necessary. During this time, many of the counseling duties of the position were lost among other responsibilities more aligned with those of an educator.

In 1983, the National Commission of Excellence in Education published “A Nation at Risk,” a report examining the quality of education in the United States (Lambie & Williamson, 2004). Among its initiatives, the report jump-started the testing and accountability movement in education. Standardized testing coordination duties were almost immediately assigned to the counselor. In fact, over the course of the past century in the profession of school counseling, the list of counselor duties and responsibilities has steadily grown to include administrative duties such as scheduling, record keeping and test coordination. With the ever-growing and expanding role of the counselor, and in an attempt to articulate the appropriate responsibilities of the counselor, the concept of comprehensive school counseling programming, which was established in the late 1970s, grew in popularity during the ’80s and ’90s (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006; Mitchell & Gysbers, 1978). As time passed, programs became increasingly articulated and workable, and an emphasis on accountability and evaluation of practice emerged (Gysbers & Henderson, 2001).

Comprehensive School Counseling Programs

What separates comprehensive school counseling from traditional guidance models is a focus on the program and not the position (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). The pupil personnel services models of the ’60s and ’70s listed the types of services offered but lacked an articulated, systemic approach, and therefore allowed for the constant assignment of other duties to school counselors. The concept of comprehensive programming was created in response to this problem (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006).

As early as 1990, Gysbers offered five foundational premises on which comprehensive school counseling is based. First, school counseling is a program and includes characteristics of other programs in education, including standards, activities and interventions that help students reach these standards; professionally certificated personnel; management of materials and resources; and accountability measures. Second, school counseling programs are developmental and comprehensive. They are developmental in that the activities and interventions are designed to facilitate student growth in the three areas of student development: academic, personal/social and career development (ASCA, 2003). They are comprehensive in that they provide a wide range of services to meet the needs of all students, not just those with the most need. The third premise is that school counseling programs utilize a team approach. Although professional school counselors are the heart of a comprehensive program, Mitchell and Gysbers (1978) established that the entire school staff must be committed and involved in order for the program to successfully take root. The fourth premise is that school counseling programs are developed through a process of systematic planning, designing, implementing and evaluating (Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). This process has been described in different ways but often using the same or similar terminology (Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008). Lastly, the fifth premise offered by Gysbers and Henderson (2006) is that comprehensive school counseling programs have established leadership. A growing message in the school counseling literature is the need for school counselors to provide leadership and advocacy for systemic change (Curry & DeVoss, 2009; McMahon, Mason, & Paisley, 2009; Sink, 2009). Without the knowledge and expertise of school counseling leaders, comprehensive programs will not take hold.

The ASCA National Model

Only within the past decade has the school counseling profession as a whole embraced the concept of comprehensive programs (Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008), a movement which was spurred by ASCA’s creation of a National Model (ASCA, 2003). In 2001, ASCA created the first iteration of its National Model; intended as a change agent, it is a framework for states, districts and counseling departments toward the creation of comprehensive developmental school counseling programs. The ASCA National Model contains four elements, or quadrants, for creating and maintaining effective comprehensive programs (ASCA, 2012). The quadrants are the tools school counselors utilize to address the academic, personal/social and career needs of their students. The first, Foundation, is the philosophy and mission upon which the program is built. The second, Delivery System, consists of the proactive and responsive services included in the program. These services can be focused individually, in small groups or school-wide, and are delivered from—or are at least influenced by—the program’s Foundation and mission statement. The third quadrant, Management, is organization and utilization of resources. Because a comprehensive program uses data to drive its Delivery System, the fourth quadrant is Accountability, which incorporates results-based data and intervention outcomes to create short- and long-term goals for the program (ASCA, 2012; Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008).

The National Model is the most widely accepted conceptualization of a comprehensive school counseling program (Burnham, Dahir, Stone, & Hooper, 2008). It resulted from a movement toward comprehensive programs born out of school counselors’ need to clarify their roles and responsibilities. Beginning with the Education Trust’s (2009) Transforming School Counseling Initiative and continuing with the creation of National Standards for Student Academic, Career and Personal/Social Development, the National Model has been built upon the concepts of social advocacy, leadership, collaboration and systemic change, which are slowly but profoundly shaping the profession (Burnham et al., 2008; Campbell & Dahir, 1997; Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008). Since the release of the National Model, however, the movement toward comprehensive school counseling programs has remained slow (Hatch & Chen-Hayes, 2008). Such slow growth inhibits school counselors from standardizing or professionalizing their roles and responsibilities (Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008).

Consequences of Competing Professional Identity Models

Lambie and Williamson (2004) stated that “based on this historical narrative, school counseling roles have been vast and ever-changing, making it understandable that many school counselors struggle with role ambiguity and incongruence while feeling overwhelmed” (p. 127). While the addition of many responsibilities has been a result of the natural expansion of the profession from vocational guidance to guidance and counseling to comprehensive school counseling, the influence of administrators has directly led to the assignment of inappropriate duties. From the outset of the profession, an essential question has involved these two competing identity models: Should school counselors be acting as educators or counselors?

The historically relevant and often opposing sets of expectations for school counselors come from both counselor educators during training and school administrators (such as principals) upon entering the profession. There is evidence to suggest that school counselors are not practicing as the profession indicates, both in terms of the ASCA National Model and the Education Trust’s Transforming School Counseling Initiative (Clemens, Milsom, & Cashwell, 2009; Hatch & Chen-Hayes, 2008; Scarborough & Culbreth, 2008). Therefore, a common source of role conflict and role ambiguity is the school administrators’ perceptions of the school counselor function, a concern that Myers (1924) established and Lambie and Williamson (2004) reiterated. The concern that school counselors are being used as quasi-administrators instead of counseling professionals continues to persist.

According to ASCA (2012), school counselors are responsible for activities that foster the academic, career and personal/social development of students. The primary role of the school counselor, therefore, is direct service and contact with students. Among the activities ASCA (2012) listed as appropriate for school counselors are individual student academic planning, direct counseling for students with personal/social issues impacting success, interpreting data and student records, collaborating with teachers and administrators, and advocating for students when necessary. Among the activities listed as inappropriate are the following: registration and scheduling; coordinating and administering standardized tests; performing disciplinary actions; covering classes, hallways, and cafeterias; clerical record keeping; and data entry. In terms of role conflict, when faced with a task, school counselors often wish to respond in a manner that is congruent with their counselor identity, but are told to apply another professional identity—namely that of educator. For example, when a school counselor is asked to provide services to a student who has bullied, while also informing the student that he or she has been suspended from school for that behavior, the counselor may experience role conflict. Role ambiguity occurs when some of the duties listed as inappropriate are included as part of the counselor’s responsibilities. For example, if a school counselor is asked to coordinate and proctor state standardized aptitude tests, the counselor experiences role ambiguity, as this duty is noncounseling-related, yet requires a significant time commitment (Culbreth, Scarborough, Banks-Johnson, & Solomon, 2005; Olk & Friedlander, 1992). These examples are but two of many possible scenarios in which the conflicting messages from competing professional identity orientations contribute to role stress for practicing school counselors.

Strategies for Addressing Competing Models

Within the recent literature on school counseling, many articles highlight the differences between school counselors’ preferred practice models and actual functioning (Burnham & Jackson, 2000; Culbreth et al., 2005; Lieberman, 2004; Scarborough & Culbreth, 2008), as well as between administrators’ view of the role of the school counselor and models of best practice within the profession (Clemens et al., 2009; Kirchner & Setchfield, 2005; Zalaquett & Chatters, 2012). However, these discrepancies were identified virtually from the outset of the profession (Ginn, 1924; Myers, 1924) and can be attributed in large part to the different orientations encountered by counseling professionals working in educational settings. Despite the concept of comprehensive school counseling and the creation of a National Model delineating appropriate roles and responsibilities, the reality is that school counselors utilize different service models depending on the region, state, district and even school in which they work. From a historical perspective, it is clear that administrators often impose their identity as educators on school counselors through the assignment of noncounseling duties. However, it is also clear that school counselors themselves have been unsuccessful in advocating for the use of current best practices. Ironically, strategies to prevent counselors from becoming quasi-administrators were identified as early as 1924.

Myers (1924) not only identified the risk for counselors to be overloaded with administrative duties, but also listed three strategies that could be used to combat this possibility. First, he suggested that “counselor[s] shall be well trained” (p. 141). This suggestion is especially important for counselor educators, who are responsible for training future counselors and acting as gatekeepers to the profession. In addition to relevant theories, techniques and practices in individual and group counseling and assessment, it is clear that school counselors-in-training also need enhanced knowledge and skill in advocacy. In order to achieve these goals, critical thought is necessary regarding school counselors’ handling of the role stress created by competing professional identity models. Emphasizing the importance of maintaining a strong relationship with administrators also is critical, as history has suggested. Furthermore, comfort and enthusiasm in gathering and using data to provide evidence of effectiveness are essential skills. In short, in addition to preparing knowledgeable and skilled counselors, counselor educators are charged with preparing leaders and advocates; they should approach their work with school counselors-in-training with this intention.

Myers’ (1924) next suggestion was that “principal[s] shall understand more clearly what counseling involves” (p. 141). As the literature suggests, school counselors and administrators share responsibility because of the inherent difference in their orientations. For administrators and others who supervise school counselors, it is important to understand that the training and professional identity of a school counselor is different from that of an educator, and that counselors are trained to address not only academic issues, but career and personal/social issues as well. Without this understanding, it is easy to impose inappropriate models of supervision and noncounseling-related activities on the counselor. It is necessary for practicing counselors to develop a strong sense of professional identity beginning in their training program. For some counselors, it is difficult to differentiate appropriate from inappropriate roles and responsibilities. This process is complicated for the many counselors who are former teachers and have been trained as both educators and counselors. However, it is essential to be able to articulate to administrators and other stakeholders the role of the counselor in maximizing student success. Practicing school counselors should portray themselves as counseling experts with the ability to create and maintain a developmentally appropriate and comprehensive program of services as defined by Gysbers and Henderson (2006). Knowledge of the ASCA National Model and other relevant state models aids in the practicing counselors’ ability to position themselves as counseling professionals and to articulate their appropriate roles as such.

Myers’ (1924) final suggestion was that “there shall be efficient supervision from a central office” (p. 141). Supervision can be provided by building administrators, district directors of school counseling or even experienced colleagues. Practicing school counselors can receive three distinct types of supervision: administrative, program and clinical. Administrative supervision is likely to occur, as it is provided by an assigned individual—usually a principal, vice principal or other administrator (Lambie & Sias, 2009). Program supervision, because it is related to comprehensive school counseling, is often present only if the district, school or counseling department adopts a comprehensive, programmatic approach (Dollarhide & Saginak, 2008). Clinical supervision is perhaps the rarest of the three (Somody, Henderson, Cook, & Zambrano, 2008), and the most necessary, because it impacts counseling knowledge and skills, and decreases the risk of unethical practice (Bernard & Goodyear, 2009; Lambie & Sias, 2009).

As Dollarhide and Saginak (2008) described, school counselors are likely encountering evaluation of practice, but rarely participating in what could be considered clinical supervision. Evidence as to why school counselors do not receive as much clinical supervision as they do administrative supervision mostly surrounds the perceptions of principals, vice principals and district-level administrators that school counselors’ roles are primarily focused on academic advising, scheduling and other noncounseling activities (Herlihy, Gray, & McCollum, 2002; Kirchner & Setchfield, 2005). However, research indicates that a significant number of practicing counselors feel as though they have no need for clinical supervision. In a national survey, Page, Pietrzak, and Sutton (2001) found that 57% of school counselors wanted to receive supervision in the future and 10% wanted to continue receiving clinical supervision; however, 33% of school counselors believed that they had “no need for supervision” (p. 146).

One reason that school counselors may not desire or see a need for supervision is the memory of previously dissatisfying experiences. Most school counselors receive a majority of their supervision from noncounseling staff such as principals (Lambie & Sias, 2009), and yet the majority of school counselors consistently point to a desire for more clinical supervision to enhance their skills and assist them with taking appropriate action with students (Page et al., 2001; Roberts & Borders, 1994; Sutton & Page, 1994). Additionally, the majority of school counselors in Page et al.’s (2001) study preferred counselor-trained supervisors, a fact that corroborated the findings of earlier studies (Roberts & Borders, 1994). When one couples this information with the idea that many principals are attempting to use existing models of teacher supervision to supervise school counselors (Lambie & Williamson, 2004), it is clear that many school counselors may be receiving inappropriate and generally dissatisfying supervision from administrators.

Conclusion

Practicing school counselors are faced with the challenge of identifying and maintaining a professional identity while receiving conflicting messages from counselor educators, administrators and other stakeholders. Counselor educators are not only responsible for addressing future counselors’ knowledge, skills and personal awareness; they are also responsible for developing counselor trainees’ professional identities. School counselors-in-training should be aware of the possible ambiguous messages and responsibilities that await them upon entering the profession. An important skill often forgotten is advocacy; counselor educators can assist future professionals in developing skills that will assist them in educating their colleagues and administrative supervisors. One example of an important change for which current and future professionals should advocate is more clinical supervision addressing counseling skills and ethical practice. A counselor-trained supervisor, such as a director of school counseling services or an experienced colleague, can provide more appropriate and satisfying supervision because of his or her knowledge of the unique demands of the work counselors do.

A look back at the history of the counseling profession reveals that the struggle over a clear professional identity has inhibited the profession almost since its inception. Perhaps a solution to this problem can be gleaned from the words of those researchers present at the beginning of the debate. Myers (1924) provided three suggestions for combating the role stress brought on by competing professional identities within the profession. Counseling professionals should begin there when considering the essential question at the heart of this debate: Are school counselors acting as counselors or educators?

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The author reported no conflict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

American School Counselor Association. (2003). The American School Counseling Association National Model: A framework for school counseling programs. Alexandria, VA: Author.

American School Counselor Association. (2012). The American School Counseling Association National Model: A framework for school counseling programs. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2009). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (4th ed.). Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Burnham, J. J., Dahir, C. A., Stone, C. B., & Hooper, L. M. (2008). The development and exploration of the psychometric properties of the assessment of school counselor needs for professional development survey. Research in the Schools, 15, 51–63.

Burnham, J. J., & Jackson, C. M. (2000). School counselor roles: Discrepancies between actual practice and existing models. Professional School Counseling, 4, 41–49.

Campbell, C. A., & Dahir, C. A. (1997). Sharing the vision: The national standards for school counseling programs. Alexandria, VA: American School Counselor Association.

Clemens, E. V., Milsom, A., & Cashwell, C. S. (2009). Using leader-member exchange theory to examine principal-school counselor relationships, school counselors’ roles, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. Professional School Counseling, 13, 75–85.

Culbreth, J. R., Scarborough, J. L., Banks-Johnson, A., & Solomon, S. (2005). Role stress among practicing school counselors. Counselor Education & Supervision, 45, 58–71. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb00130.x

Curry, J. R., & DeVoss, J. A. (2009). Introduction to special issue: The school counselor as leader. Professional School Counseling, 13, 64–67.

Dollarhide, C. T., & Saginak, K. A. (2008). Comprehensive school counseling programs: K–12 delivery systems in action. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Education Trust. (2009). The new vision for school counseling. Retrieved from http://www.edtrust.org/dc/tsc/vision

Ginn, S. J. (1924). Vocational guidance in Boston public schools. The Vocational Guidance Magazine, 3, 3–7. doi:10.1002/j.2164-5884.1924.tb00202.x

Gysbers, N. C. (1990). Comprehensive guidance programs that work. Ann Arbor, MI: ERIC Counseling and Personnel Services Clearinghouse.

Gysbers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2001). Comprehensive guidance and counseling programs: A rich history and a bright future. Professional School Counseling, 4, 246–256.

Gysbers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2006). Developing & managing your school guidance and counseling program (4th ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Hatch, T., & Chen-Hayes, S. F. (2008). School counselor beliefs about ASCA National Model school counseling program components using the SCPCS. Professional School Counseling, 12, 34–42.

Herlihy, B., Gray, N., & McCollum, V. (2002). Legal and ethical issues in school counselor supervision. Professional School Counseling, 6, 55–60.

Kirchner, G. L., & Setchfield, M. S. (2005). School counselors’ and school principals’ perceptions of the school counselor’s role. Education, 126, 10–16.

Lambie, G. W., & Sias, S. M. (2009). An integrative psychological developmental model of supervision for professional school counselors-in-training. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87, 349–356. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00116.x

Lambie, G. W., & Williamson, L. L. (2004). The challenge to change from guidance counseling to professional school counseling: A historical proposition. Professional School Counseling, 8, 124–131.

Lieberman, A. (2004). Confusion regarding school counselor functions: School leadership impacts role clarity. Education, 124, 552–558.

McMahon, H. G., Mason, E. C. M., & Paisley, P. O. (2009). School counselor educators as educational leaders promoting systemic change. Professional School Counseling, 13, 116–124. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2010-13.116

Mitchell, A. M., & Gysbers, N. C. (1978). Comprehensive school counseling programs. In The status of guidance and counseling in the nation’s schools (pp. 23–39). Washington, DC: American Personnel and Guidance Association.

Myers, G. E. (1924). A critical review of present developments in vocational guidance with special reference to future prospects. The Vocational Guidance Magazine, 2, 139–142. doi:10.1002/j.2164-5884.1924.tb00721.x

Olk, M. E., & Friedlander, M. L. (1992). Trainees’ experiences of role conflict and role ambiguity in supervisory relationships. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 39, 389–397. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.39.3.389

Page, B. J., Pietrzak, D. R., & Sutton, J. M., Jr. (2001). National survey of school counselor supervision. Counselor Education & Supervision, 41, 142–150. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2001.tb01278.x

Pope, M. (2009). Jesse Buttrick Davis (1871–1955): Pioneer of vocational guidance in the schools. The Career Development Quarterly, 57, 248–258. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2009.tb00110.x

Roberts, E. B., & Borders, L. D. (1994). Supervision of school counselors: Administrative, program, and counseling. School Counselor, 41, 149–157.

Scarborough, J. L., & Culbreth, J. R. (2008). Examining discrepancies between actual and preferred practice of school counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86, 446–459. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00533.x

Sink, C. A. (2009). School counselors as accountability leaders: Another call for action. Professional School Counseling, 13, 68–74.

Somody, C., Henderson, P., Cook, K., & Zambrano, E. (2008). A working system of school counselor supervision. Professional School Counseling, 12, 22–33.

Sutton, J. M., Jr., & Page, B. J. (1994). Post-degree clinical supervision of school counselors. School Counselor, 42, 32–40.

Zalaquett, C. P., & Chatters, S. J. (2012). Middle school principals’ perceptions of middle school counselors’ roles and functions. American Secondary Education, 40, 89–103.

Daniel Cinotti is an assistant professor at the New York Institute of Technology. Correspondence can be addressed to Daniel Cinotti, Department of School Counseling, NYIT, 1855 Broadway, New York, NY 10023-7692, dcinotti@nyit.edu.

Dec 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 5

Gerta Bardhoshi, Amy Schweinle, Kelly Duncan

This mixed-methods study investigated the relationship between burnout and performing noncounseling duties among a national sample of professional school counselors, while identifying school factors that could attenuate this relationship. Results of regression analyses indicate that performing noncounseling duties significantly predicted burnout (e.g., exhaustion, negative work environment and deterioration in personal life), and that school factors such as caseload, Adequate Yearly Progress status and level of principal support significantly added to the prediction of burnout over and above noncounseling duties. Moderation tests revealed that Adequate Yearly Progress and caseload moderated the effect of noncounseling duties as related to several burnout dimensions. Participants related their burnout experience to emotional exhaustion, reduced effectiveness, performing noncounseling duties, job dissatisfaction and other school factors. Participants conceptualized noncounseling duties in terms of adverse effects and as a reality of the job, while also reframing them within the context of being a school counselor.

Keywords: burnout, noncounseling duties, professional school counselors, mixed methods, job dissatisfaction

Although the term burnout was first coined by Freudenberger (1974) to describe a clinical syndrome encompassing symptoms of job-related stress, it is generally accepted that the work of Maslach and colleagues has served as the foundation of the empirical study of burnout as a psychological phenomenon. Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leiter (2001) defined burnout as a prolonged exposure to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job. The primary focus of burnout studies remains within the occupational sector of human services and education, where empathy demands are high and the emotional challenges of working intensively with other people in either a caregiving or teaching role are considerable (Maslach et al., 2001). Burnout is defined by three core dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1981).

Emotional exhaustion is a key aspect of the burnout syndrome. It is the most obvious manifestation of the syndrome (Maslach et al., 2001) and a reaction to increasing job demands that produce a sense of overload and exhaust one’s capacity to maintain involvement with clients (Lee & Ashforth, 1996). Feeling unable to respond to the needs of the client, one experiences purposeful emotional and cognitive distancing from one’s work. This effort to establish distance between oneself and the client is defined as depersonalization. Reduced personal accomplishment describes the eroded sense of effectiveness that burned-out individuals experience (Maslach et al., 2001).

According to the job demands–resources model, one of the most cited models in burnout literature, burnout occurs in two phases: first, extreme job demands lead to sustained effort and eventually exhaustion; second, a lack of resources to deal with those demands further leads to withdrawal and eventual disengagement from work (Demerouti, Nachreiner, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2001). Professional school counseling is a profession in which emotional empathy is a requirement, and the qualitative and quantitative job demands are high. Stressors linked to burnout (e.g., high workload, negative work environment) have effects that may persist even after exposure to the stressor has ended, leading to negative impact on daily well-being (Repetti, 1993). In those jobs in which high demands exist simultaneously with limited job resources, both exhaustion and disengagement are evident (Bakker, Demerouti, & Euwema, 2005; Demerouti et al., 2001). With organizational factors accounting for the greatest degree of variance in burnout studies (Lee & Ashforth, 1996), robustly exploring factors unique to the profession of school counseling is a key to understanding the phenomenon of burnout in school counselors.

Variables Related to Burnout in School Counselors

School counseling literature has repeatedly drawn attention to organizational variables that are problematic for the profession and might provide insight into the burnout phenomenon. School counselors face rising job demands (Cunningham & Sandhu, 2000; Gysbers, Lapan, & Blair, 1999; Herr, 2001) that are often difficult to balance (Bryant & Constantine, 2006), leading them to feel overwhelmed in their work environment (Kendrick, Chandler, & Hatcher, 1994; Kolodinsky, Draves, Schroder, Lindsey, and Zlatev, 2009; Lambie & Williamson, 2004), and to lack the time to provide direct services to students (Gysbers & Henderson, 2000). In addition to job overload, school counselors also are expected to perform a high number of conflicting job responsibilities, leading to role conflict (Coll & Freeman, 1997).

Role conflict is indeed related to burnout in school counselors (Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006). Paperwork and other noncounseling duties interfere with the roles of school counselors and are a source of job stress and dissatisfaction (Burnham & Jackson, 2000; Kolodinsky et al., 2009). Authors have pointed out that school counselors who perform noncounseling duties labeled as inappropriate rate them as highly demanding (McCarthy et al., 2010), experience less satisfaction with and commitment to their jobs (Baggerly & Osborn, 2006), and cite these duties as a source of stress and role conflict (Kendrick et al., 1994).

Another factor implicated in school counselor overload is a large caseload (Sears & Navin, 1983). The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) recommends a 250:1 ratio of students to counselors; however, the national average of students per counselor is closer to 471 (ASCA, 2014). High counselor-to-student ratios further decrease the already limited time school counselors have available for providing direct counseling services to students (Astramovich & Holden, 2002). Feldstein (2000) reported that larger caseloads correlate with higher burnout in school counselors, a finding also echoed in Gunduz’s (2012) study of school counselors in Turkey.

School counseling today continues to be affected by initiatives and educational reforms (Herr, 2001), with school counselors facing the expectation of involvement in both educational and mental health initiatives (Paisley & McMahon, 2001). A current example includes the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) mandate, passed in 2002, which emphasizes required testing for all students, as well as increased accountability for school staff, including school counselors, to track student progress (Erford, 2011). Despite school counselors being an essential part of the school achievement team, they were not included in the NCLB reform movement (Thompson, 2012). The consequences of not meeting annual NCLB progress targets, termed Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP), have been implicated in increased stress for school staff and have negatively impacted school climates (Paisley & McMahon, 2001; Thompson & Crank, 2010), potentially important factors to explore in relation to school counselor burnout.

A few studies also have drawn attention to the organizational support received from colleagues and supervisors in the work environment and the potential moderating effects of this variable on burnout. Perceived organizational support refers to employees’ perception of their value to the organization, as well as the support available to help them perform their work and deal effectively with stressful situations (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). Bakker et al. (2005) found that, among other factors, a high-quality relationship with one’s supervisor provided a buffering effect on the impact of work overload on emotional exhaustion. Similarly, school counselors who perceive their own value to the organization as high seem to experience lower levels of job-related stress and greater levels of job satisfaction (Rayle, 2006). Lambie (2002) identified organizational support as the greatest influence on school counselor burnout levels in all three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment. Yildrim (2008) reported significant negative relationships between principal support and burnout in school counselors, while Wilkerson and Bellini (2006) further asserted that working relationships with school principals make a difference in school counselor burnout.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between burnout among professional school counselors, as measured by the Counselor Burnout Inventory (CBI; Lee et al., 2007), and the assignment of noncounseling duties, as measured by the School Counselor Activity Rating Scale (SCARS; Scarborough, 2005), while also identifying other organizational factors in schools that could attenuate this relationship. We aimed to obtain different but complementary data on the same topics and included open-ended qualitative questions in the online survey in order to expand on quantitative results with qualitative data and gain a more nuanced understanding of burnout (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). Connides (1983) concluded that this combined qualitative and quantitative analysis approach is efficient for gathering baseline data from large numbers of respondents, resulting in a broader understanding of participants and phenomena. Research questions included the following:

What is the relationship between noncounseling duties, as measured by all three subscales of the SCARS (Fair Share, Clerical and Administrative), and burnout, as measured by each of the five subscales of the CBI (Exhaustion, Incompetence, Negative Work Environment, Devaluing Client and Deterioration in Personal Life) among professional school counselors surveyed?

Do other school factors—specifically caseload, principal support and meeting AYP—also affect burnout, above and beyond noncounselor duties?

Can other school factors attenuate the effect of assignment of noncounselor duties on burnout?

What is the individual, unique and subjective meaning that participants ascribe to their experience of burnout and performing noncounseling duties in a school setting?

Method

Participants and Procedure

After obtaining institutional board approval, we created a randomized list of 1,000 school counselors who belonged to ASCA. The survey method followed a multiple-contact procedure suggested by Dillman (2007) regarding Internet surveys; a criterion sampling procedure embedded in the first page of the online survey ensured that all participants who progressed to the survey met the following criteria: (a) certified as a school counselor in their practicing state, and (b) working in elementary, middle and/or high school. Of the 286 counselors who responded to an e-mail survey invitation, 252 provided complete responses on the CBI, resulting in a 26% response rate (sample sizes for the specific tests may vary as a function of missing data for individual variables).

Some states offer a K–12 certification for school counselors. School counselors with this certification typically work in small schools and their assignment is the whole K–12 population; or, in the case in which counselors work in a school with multiple school counselors, their assignment might be a mix of grades from K–12. Participants in this study included school counselors with a wide range of grade-level assignment: 36.5% were K–12 school counselors, 32.9% were high school counselors, 19% were elementary school counselors and 11.5% were middle school counselors. The majority of the school counselors (41.7%) reported a rural work location, with the remaining 31% being suburban and 27.8% urban. Public school counselors made up the majority of the sample (75% public vs. 18.3% private). The sample also included charter schools (6%) and a tribal school (.4%). Although 36.5% of the participants reported caseloads of up to 250, the majority of the participants reported caseloads over the recommended ASCA numbers of 250 (32.9% had caseloads of 251–400; 30.6% had caseloads of 400+). The majority of school counselors (56%) indicated that their school had made AYP for the most recent school year, with 24.6 % indicating that their school had not made AYP, and 19.4% identifying AYP as not applicable for their particular school. School counselors’ responses also ranged in how supported they felt by their school principal—from very much so (42.9%), to quite a bit (23%), moderately (18.7%), a little bit (12.3%) and not at all (3.2%).

Women made up the majority of the sample (82.1% vs. 17.9% men). In terms of race and ethnicity, the majority identified as White (78.6%), with the next largest groups being Black and Hispanic (both 7.9%). The majority of school counselors (49.2%) selected the 0–5 range for their years of experience, with the following categories (6–10 and 11+) almost equally distributed (25% and 25.8%, respectively).

Instruments

Counselor Burnout Inventory. The CBI is a 20-item instrument designed to measure burnout in professional counselors (Lee et al., 2007). It is divided into five subscales: Exhaustion (e.g., “I feel exhausted due to my job as a counselor”), Incompetence (e.g., “I feel frustrated by my effectiveness as a counselor”), Negative Work Environment (e.g., “I feel negative energy from my supervisor”), Devaluing Client (e.g., “I am not interested in my clients and their problems”) and Deterioration in Personal Life (e.g., “I feel I have poor boundaries between work and my personal life”). Participants rate items on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = never true, to 5 = always true. Scores for each of the individual subscales may range from 4–20, with total scores ranging from 20–100.

Lee et al. (2007; 2010) examined the initial validity and reliability of the CBI with two samples of counselors from a variety of specialties, including professional school counselors. Construct validity for the CBI was assessed by utilizing an exploratory factor analysis, which resulted in a five-factor solution that accounted for 66.97% of the total variance, with all goodness of fit indices also supporting an adequate fit to the data. Reported internal consistency for all five subscales by Lee et al. (2007) included alpha coefficient scores of .94 for the overall scale and .80 for Exhaustion, .81 for Incompetence, .83 for Negative Work Environment, .83 for Devaluing Client and .84 for Deterioration in Personal Life subscales. Test-retest reliability of the CBI across all five subscales was .81, indicating good reliability of this instrument over time. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of scores for the CBI were .92, well within the reported range of .88–.94.

School Counselor Activity Rating Scale. The SCARS was designed to assess the frequency with which school counselors actually perform certain activities, as well as the frequency with which they would prefer to perform those activities (Scarborough, 2005; Scarborough & Culbreth, 2008). Utilizing a verbal frequency scale (ranging from 1 = rarely do this activity, to 5 = routinely do this activity), school counselors rate their actual and preferred performance of a wide range of intervention activities (e.g., counsel students regarding personal problems, coordinate and maintain a comprehensive school counseling program) as well as other noncounseling activities. Only the Other Duties scale of the SCARS was used for this study. Participants rated their actual performance of 10 activities that fall into three subscales: Clerical (e.g., “schedule students for classes”), with scores ranging from 3–15; Fair Share (e.g., “coordinate the standardized testing program”), with scores ranging from 5–15; and Administrative (e.g., “substitute teach and/or cover for teachers at your school”), with scores ranging from 2–10.

Scarborough (2005) examined the initial validity and reliability of the SCARS with a random sample of 300 school counselors, demonstrating content and construct validity for the SCARS subscales. A separate analysis on the 10 items reflecting Other School Counseling Activities supported three factors in which noncounseling activities can be categorized: Clerical, Fair Share and Administrative. Scarborough (2005) also demonstrated convergent and discriminant construct validity. Reported Cronbach’s alphas were .84 for the Clerical subscale, .53 for the Fair Share subscale, and .43 for the Administrative subscale. Despite some subscale low reliability scores, the researchers were unable to locate any other instrument measuring noncounseling duties with published psychometric data. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the Other Duties Subscale scale was an adequate .69 and within the reported range of .43–.84.

Demographic Information. Demographic information collected included gender, ethnicity, highest degree earned, number of years as a practicing school counselor, grade-level assignment, location of school, type of school, total numbers of students in school, caseload number, total number of school counselors in school, percentage of minority students, percentage of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch, whether the school made AYP, and perceived level of support from school principals.

Qualitative Questions. Three open-ended questions were included in the online survey to allow participants latitude in their responses (Marshall & Rossman, 1999). These questions included the following: What does burnout mean to you as a school counselor?, What does performing noncounseling duties in a school setting mean to you? and What other information would you like to add that has not been addressed in this survey?

Data Entry and Analysis

Data were imported from SurveyMonkey to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18 and examined prior to analysis. A concurrent triangulation mixed-methods design was utilized with the qualitative and quantitative data analyzed separately but integrated in the interpretation of the findings; quantitative and qualitative findings were combined into a “coherent whole” (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011, p. 214). It was hypothesized that among professional school counselors surveyed, a model containing all three of the SCARS subscales measuring noncounseling duties (Fair Share, Clerical and Administrative) would significantly predict three subscales of the CBI (Exhaustion, Negative Work Environment and Deterioration in Personal Life). In order to test this hypothesis, we conducted five separate linear, multiple-regression analyses of assignment of noncounselor duties (Clerical, Fair Share and Administrative, as measured by the SCARS) on each of the measures of burnout (Exhaustion, Incompetence, Negative Work Environment, Devaluing Clients and Deterioration in Personal Life, as measured by the CBI). We predicted that noncounselor duties would significantly predict exhaustion, negative work environment and deterioration in personal life. (Those participants who said AYP was not applicable to them were removed from this and future analyses.)

We also questioned whether school factors that could tap into job demands and resources (e.g., caseload, meeting AYP and lack of principal support) were predictive of burnout, over and above noncounselor duties. Caseload was coded as 0–250, 251–400, and over 400. Therefore, we dummy-coded this variable with the ASCA-recommended load of 0–250 as the reference group. We conducted hierarchical regressions, assessing the increase in prediction of burnout by other factors from the models with only noncounselor duties. To test the possibility that other school factors (e.g., meeting AYP, caseload, principal support) may increase or lessen (i.e., moderate) the effects of noncounseling duties on burnout, we ran a series of moderation tests (see Baron & Kenny, 1986) to arrive at a model for each measure of burnout including only the meaningful moderators. To create moderation terms, we centered the measures of noncounselor duties and other school factors about their means, and then multiplied (other school factors × noncounselor duties). For each measure of burnout, we used hierarchical regression to determine if the moderators significantly added to the prediction, over and above the main effects. We tested the addition of each moderator to the main effects model. Because this resulted in 60 tests, only the significant tests are reported in the results.

Analysis of the qualitative data was guided by a grounded theory approach, which allows the researcher to inductively move from a simple to a more nuanced understanding of a phenomenon through the identification and formulation of words, concepts and categories within the text (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Although not used to build a theory, this methodology allows for the utilization of frequency, meanings and relationships of words, concepts or categories to make meaningful inferences regarding the participants’ words (Silverman, 1999).

The first author coded qualitative responses line-by-line using etic or substantive codes, which were informed by school counseling and burnout literature. The first author then used a second level of coding: emic codes that emerged from the data, which are open codes using the participant’s own words to identify any emergent codes that departed from or supplemented burnout and school counseling literature. A constant comparative method, which compares coded segments of text with similar and different segments, was utilized to further refine the analysis. Axial codes were then used to conceptually categorize codes in order to capture larger emergent themes (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

When using qualitative methodology, researchers must be transparent as they become instruments of investigation. The first author is in her second year as a counselor educator, and was prompted to study the topic after working closely with school counselors who displayed many of the symptoms of burnout. The third author is in her 11th year as a counselor educator and has been involved in the field of school counseling for over 25 years. In addition to utilizing a subjectivity memo to guard against bias (Marshall & Rossman, 1999), we enhanced trustworthiness by having the third author audit the first author’s entire process and documents. A review of verbatim responses to determine adequate categorization of codes and themes derived by the first author provided a reliability check, and led to appropriate adjustments made by consensus. Response frequencies are included to present particularly influential codes (Driscoll, Appiah-Yeboah, Salib, & Rupert, 2007).

Results

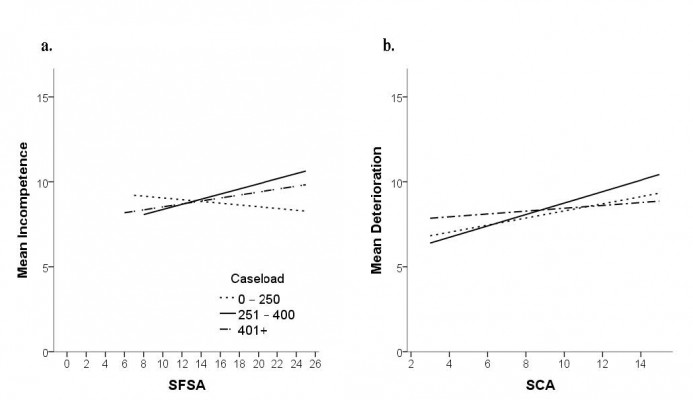

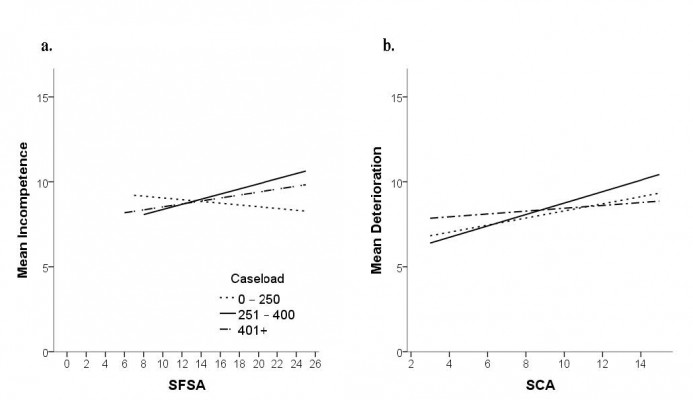

Assignment of Noncounselor Duties and Burnout