Dec 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 5

Qi Shi, Xi Liu, Wade Leuwerke

This study sought to examine students’ perceptions of their school counselors in two high schools in Beijing, China. Independent t tests found that female students rated school counselors’ availability significantly higher than male students did. Also, students who had received prior counseling services rated counselors significantly higher in the following areas than did students who had never received counseling services: knowledge of achievement tests, friendliness and approachability, understanding students’ point of view, advocating for students, promptness in responding to requests, ability to explain things clearly, reliability to keep promises, availability, and overall effectiveness. A 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA found an interaction effect between gender and use or nonuse of counseling services. In general, students gave positive evaluations of school counselors and were satisfied with counseling services.

Keywords: school counselors; counseling services; students’ perceptions; high schools; Beijing, China

China has been experiencing dramatic economic and social changes in the past 3 decades (Guthrie, 2012). During this time there has been increased attention to both mental health problems and student development (Cyranoski, 2010; Lim, Lim, Michael, Cai, & Schock, 2010; Xin & Zhang, 2009). It has been estimated that at least 17.5% of the Chinese population has some form of mental illness, one of the highest rates in the world (Phillips et al., 2009), accounting for about 20% of hospitalizations in the country (Fei, 2006). Facing significant mental health challenges, several authors have noted the need for more counseling professionals and mental health service providers (Cook, Lei, & Chiang, 2010; Davey & Zhao, 2012). In rural areas with fewer resources, the demand for mental health care is even greater (Ji, 2000).

Given such great needs for mental health services, China has been making tremendous efforts in reforming its mental health service system (Tse, Ran, Huang, & Zhu, 2013). In 2004, China launched the 686 Project, a mental health reform initiative modeled on the World Health Organization’s recommended framework for integrating hospital-based services with a community mental health service system (Ma, 2012). By the end of 2011, 1.83 million Chinese people with severe mental illness had been treated as a result of the project.

While China has witnessed growth in the counseling profession, at the same time it has struggled to build national certification and licensing standards, and create comprehensive counselor training (Chang & Kleinman, 2002; Cook et al., 2010; Davey & Zhao, 2012; Ding, Kuo, & Van Dyke, 2008; Hou & Zhang, 2007). In 2002, China’s National Counseling Licensing Board was formed, and there is currently a three-tier national licensing program. More than 30 locations throughout China offer the qualification exams for counselors, and recently a national exam to license school counselors was instituted (Lim et al., 2010). Results from a nationwide survey of professional training of mental health practitioners in China showed that quality of training and supervision were among common concerns (Gao et al., 2010). Also, more accredited professional training programs at the university or college level must be designed and established. Beijing Normal University, in collaboration with Rowan University in the United States, was reported to be the first university in China to offer a school counseling training program (Lim et al., 2010).

Mental Health of Students in China

Increased attention to student well-being has shown high prevalence of mental health problems among Chinese students (Cook et al., 2010; Wang & Miao, 2001). Common psychological problems among students included test anxiety, academic pressure, loneliness, social discomfort, video game addiction (Thomason & Qiong, 2008), Internet addiction, child obesity, self-centeredness and reclusion (Worrell, 2008). A study from a metropolitan area in southeastern China showed that 10.8% of high school students had mental health concerns including hostility, compulsions, depression and interpersonal relationship sensitivity (Hu, 1994). A more recent survey conducted by Wu et al. (2012) among 1,891 high school students in a southern city in China showed that 25% of the adolescents reported a perceived need for mental health services, while only 5% of the sample had used school-based mental health services, and 4% had used non-school-based services.

Researchers are starting to identify factors that contribute to Chinese students’ mental health problems, including the pressure to achieve academic success (Corbin Dwyer & McNaughton, 2004; Thomason & Qiong, 2008; Worrell, 2008), being an only child (Liu, Munakata, & Onuoha, 2005; Thomason & Qiong, 2008; Worrell, 2008), prevalence of physical abuse (Wong, Chen, Goggins, Tang, & Leung, 2009), inability to cope with multiple expectations and requirements (Tang, 2006), increased attention to personal and social development (Corbin Dwyer & McNaughton, 2004), and the generation gap between children and their parents (Thomason & Qiong, 2008). Zheng, Zhang, Li, and Zhang (1997) suggested that parents and teachers who did not attend to students’ psychological problems contributed to the high rates of mental health problems among students. Because they have the most direct interaction with students, homeroom teachers and subject teachers in China are well-positioned to help students address their mental health concerns. In fact, Chinese homeroom teachers perform a wide variety of counseling tasks (Shi & Leuwerke, 2010). However, teachers do not receive sufficient training in providing counseling services.

School Counseling in China

School counselors are uniquely positioned to impact the mental health and academic success of students in China. As would be expected with developing professions, there are numerous challenges to school counseling in China: (a) a tremendous shortage of qualified school counselors (Cook et al., 2010; Shi & Leuwerke, 2010; Thomason & Qiong, 2008; Yan, 2003; Zheng et al., 1997), (b) an urgent need for more accredited training programs (Gao et al., 2010; Leuwerke & Shi, 2010; Lim et al., 2010) and (c) a lack of support and respect from teachers and other school staff (Jiang, 2005; Leuwerke & Shi, 2010). Although many schools in China, especially in urban areas, have begun to establish counseling offices and hire school counselors, this profession is still in its primitive developmental stage (Leuwerke & Shi, 2010). Moreover, school counselors themselves have expressed great need for more training and standard education to better serve their students (Leuwerke & Shi, 2010). A standardized training system is imperative to provide training, assessment, issuance of licenses and continued education (Cook et al., 2010; Davey & Zhao, 2012; Yan, 2003; Zheng et al., 1997).

Facing the serious situation of Chinese students’ mental health concerns and school counseling challenges, the Chinese government has turned greater attention to advanced mental health education in K–12 schools. Government policies on education reform have put more emphasis on students’ mental health and the availability of psychological services (Ding et al., 2008). The Ministry of Education in China has published two important government guidelines in the past 2 decades. “Several Suggestions on Improving Mental Health Education in Elementary & Secondary Schools” (Zhong guo jiao yu bu, 1999) identified moral and politics teachers, homeroom teachers, Communist Youth League cadres, and school counselors as the personnel in schools responsible for the mental health needs of students. K–12 schools with available resources and funding were required to establish counseling offices, and school counselors were identified as the leaders of this system (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 1999). In 2012, the Ministry of Education released the updated version of “Guideline of Mental Health Education in Elementary & Secondary Schools.” This guideline described the goals, content and methods of mental health education as well as the personnel responsible for delivery. The report specifically called for educating students about basic knowledge and skills regarding interpersonal relationships, career development, and living and socialization (Zhong guo jiao yu bu, 2012).

As required by the Chinese government, schools in large cities have begun to hire school counselors to provide counseling for their students (Jiang, 2005). In K–12 schools in China, school counseling is called school guidance or mental health education, which is actually a part of political and moral education (Jiang, 2005). School guidance in K–12 school settings has been taught as a subject course like math or science (Hou & Zhang, 2007). In addition to school counselors, homeroom teachers also play an important role in mental health services for students by performing a large range of counseling tasks (Shi & Leuwerke, 2010; Wang, 1997). Chinese students access psychological services in schools through a variety of channels: individual counseling, group activities, lectures on common psychological concerns, parent and teacher consultation, and classroom guidance (Leuwerke & Shi, 2010).

The expansion of services in the Chinese school system has made counseling more accessible than ever to students (Thomason & Qiong, 2008). However, empirically based literature examining the role, function and scope of school counseling in China is virtually nonexistent (Jiang, 2005; Leuwerke & Shi, 2010; Shi & Leuwerke, 2010; Thomason & Qiong, 2008). Very little is known about the amount of counseling that students actually receive at school, let alone how students perceive school counselors and the school counseling services they receive (Leuwerke & Shi, 2010). The present study sought to examine some of these questions. Through surveys of students at two high schools in Beijing, the authors explored students’ use of counseling in school as well as their perceptions of the school counselors. The authors also examined possible differences among students who sought services or not, as well as any differences across gender. Correspondingly, the research questions in this study were as follows: (a) How many students seek counseling services and how often do they meet their school counselors in these two high schools in Beijing? (b) Do students’ perceptions of the school counselors differ across gender? (c) Do students’ perceptions of the school counselors differ depending on whether or not they seek counseling services? (d) Do male and female students’ perceptions differ depending on whether or not they seek counseling services?

Methods

Participants

A total of 137 (47 male, 90 female) students from two high schools in Beijing completed questionnaires; 293 surveys were distributed, resulting in a return rate of 46.76%. The sample was recruited through the first author’s contacts in Beijing. Among the students who completed the survey, 126 were from a high school affiliated with Beijing Normal University and 11 were from a high school affiliated with Beijing Renmin University. The sample consisted of 12.4% (n = 17) senior 1 students (equivalent to 10thgraders in the United States), 78.8% (n = 108) senior 2 students (equivalent to 11th graders in the United States) and 8.8% (n = 12) senior 3 students (equivalent to 12th graders in the United States). The two high schools recruited for the study are among the top ranked high schools in Beijing. The school counselors being evaluated in these two high schools had an average of 8 years of experience working as professional school counselors. Students from these schools typically perform very well in academics and gain admission to universities after high school. As for plans after high school, 97.8% (n = 134) of the students surveyed stated that the plan was a 4-year college, with only three students indicating “other plans.” No student indicated planning to attend a 2-year college or vocational training school or get a job right after graduating from high school.

Instrument

Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire as well as the Chinese High School Students’ Perceptions of School Counselors Survey. All information students provided in the survey was anonymous. The demographic questionnaire included items such as students’ grade level, gender and postsecondary plans. The Chinese High School Students’ Perceptions of School Counselors Survey used in this study was adapted from McCullough’s (1973) survey that was originally designed to determine high school students’ perceptions of school counselors’ services in the United States. Some changes were made to adapt to Chinese students’ cultural background, including adding two questions about the number of times that students had tried to see the school counselor and the actual number of times that they had met with the school counselor. After indicating the number of times they had tried and actually met with a school counselor, participants rated their counselor’s ability and effectiveness on a four-point Likert scale (4 = excellent, 3 = good, 2 = fair, 1 = poor) in the following 11 areas: knowledge of college admission, knowledge of vocational information, knowledge of achievement tests, friendliness and approachability, understanding students’ point of view, advocate for students, promptness in responding to requests, ability to explain things clearly, reliability to keep promises, availability to students, and overall effectiveness.

Translation

The authors created all materials utilized in this study in English, and the first author then translated the documents into Mandarin Chinese. To examine translation quality, a bilingual, native Chinese speaker who was not part of the research team subsequently translated all documents back into English. The authors evaluated and considered these translated documents equivalent. This approach is consistent with common practice in research requiring translation of documents (Larkin, de Casterlé, & Schotsmans, 2007; Liu et al., 2005).

Design

Data analyses were conducted based on the four research questions in this study. First, descriptive statistical analysis was conducted to learn the number of students who had sought counseling services and the frequency of their meetings with a counselor. Second, an independent t test was conducted to determine the differences between male and female students’ perceptions of their school counselors’ services. Third, another independent t test was performed to examine the differences between students’ perceptions of their school counselors’ services depending on whether or not the students had sought prior counseling services. Finally, a 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA was done to determine whether there was a statistically significant interaction effect between gender and whether or not students sought prior counseling services.

The data from students who had never had individual meetings with counselors were included in these analyses. These data were included because these students had had contact with school counselors in other circumstances (e.g., lectures, classroom guidance, school-wide gathering), even though they had not met with school counselors individually (Leuwerke & Shi, 2010).

Procedure

Five teachers at the two high schools assisted with data collection. Since research participation and the protocol were new to most of the teachers, explanation of the confidential and voluntary nature of the project was provided through teleconference. Questions from the teachers were answered via e-mail. One of the teachers in Beijing was in charge of the informed consent forms and data storage. Parents of the students in the classrooms of all five teachers received one copy of the informed consent and all granted consent for their child to participate in the research. Students then received e-mails. An online survey tool (http://www.surveymonkey.com) was used to administer the questionnaire.

Results

The first goal of this study was to examine how many students had sought services from school counselors and the number of meetings they had had with their school counselors since they entered high school. Descriptive statistics were obtained in order to achieve this goal. Nearly half of the participants (48.9%, n = 67) reported having seen counselors at least once. Among these 67 students, the majority (n = 41) had met once individually with a school counselor, 22 had seen a school counselor individually two to three times, and four students had talked with school counselors four to five times. No student reported having met with a school counselor more than five times. Information on the length of these individual counseling sessions was not obtained in the survey.

The second goal of this study was to examine the students’ perceptions of their school counselors. Fifty-three students provided a complete evaluation of their school counselors in the survey. Among these 53 students, 36 had used counseling services before, whereas 17 reported no individual meetings with a counselor. As shown in Table 1, students’ most positive ratings of their school counselors were for friendliness and approachability (M = 3.20, SD = 1.25) and ability to explain things clearly (M = 2.99, SD = 1.33). The lowest rated attributes were knowledge of college admission (M = 1.30, SD = 1.42) and knowledge of vocational information (M = 1.10, SD = 1.30).

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics on Students’ Evaluations of School Counseling Services

|

School counseling services evaluated

|

N

|

Min

|

Max

|

M

|

SD

|

| Friendliness and approachability |

137

|

0

|

4

|

3.20

|

1.25

|

| Ability to explain things clearly |

137

|

0

|

4

|

2.99

|

1.33

|

| Availability to students |

137

|

0

|

4

|

2.77

|

1.38

|

| Understanding students’ points of view |

138

|

0

|

4

|

2.73

|

1.32

|

| Promptness in responding to requests |

137

|

0

|

4

|

2.68

|

1.47

|

| Reliability to keep promises |

137

|

0

|

4

|

2.37

|

1.62

|

| Advocate for students |

137

|

0

|

4

|

2.31

|

1.51

|

| Knowledge of achievement tests |

137

|

0

|

4

|

1.82

|

1.44

|

| Knowledge of college admission |

141

|

0

|

4

|

1.30

|

1.42

|

| Knowledge of vocational information |

138

|

0

|

4

|

1.10

|

1.30

|

| Overall effectiveness |

137

|

0

|

4

|

2.51

|

1.40

|

| Valid N (listwise) |

137

|

|

|

|

|

Furthermore, independent t tests were conducted to determine whether students’ ratings of counseling services differed significantly between genders and between students who had or had not sought counseling services. A statistically significant result was found in students’ ratings of school counselors’ availability in the independent t test based on gender. Female students rated school counselors’ availability significantly higher than male students did (F = 4.196, p < .05). Statistically significant results also were found based on whether or not the students had sought counseling services. As shown in Table 2, students who had received prior counseling services rated counselors significantly higher in the following areas than did students who had never received counseling services: knowledge of achievement tests, friendliness and approachability, understanding students’ point of view, advocate for students, promptness in responding to requests, ability to explain things clearly, reliability to keep promises, availability, and overall effectiveness.

Table 2

Students’ Evaluations of School Counselors Depending on Whether or Not They Seek Services

|

School counseling services evaluated

|

Levene’s testa

|

|

t testb

|

|

F

|

p

|

|

t

|

df

|

p

|

M

difference

|

SE

difference

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Knowledge of college admission |

.59

|

.443

|

|

1.84

|

139

|

.068

|

.46

|

.25

|

| Knowledge of vocational information |

.55

|

.460

|

|

2.22

|

135

|

.028

|

.51

|

.23

|

| Knowledge of achievement tests |

7.61

|

.007

|

|

1.53

|

134

|

.128

|

.40

|

.26

|

| Friendliness and approachability |

7.34

|

.008

|

|

2.10

|

135

|

.038

|

.47

|

.22

|

| Understanding students’ points of view |

8.26

|

.005

|

|

2.46

|

136

|

.015

|

.57

|

.23

|

| Advocate for students’ |

2.89

|

.092

|

|

2.50

|

135

|

.014

|

.67

|

.27

|

| Promptness in responding to requests |

18.23

|

.000

|

|

2.12

|

135

|

.036

|

.55

|

.26

|

| Ability to explain things clearly |

17.92

|

.000

|

|

2.24

|

135

|

.027

|

.53

|

.24

|

| Reliability to keep promises |

9.28

|

.003

|

|

2.44

|

135

|

.016

|

.70

|

.29

|

| Availability to students |

9.59

|

.002

|

|

2.24

|

135

|

.027

|

.55

|

.25

|

| Overall effectiveness |

39.95

|

.000

|

|

3.03

|

135

|

.003

|

.74

|

.25

|

aLevene’s test for equality of variances. bt test for equality of means.

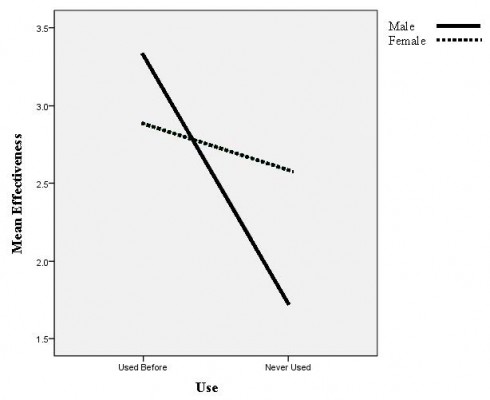

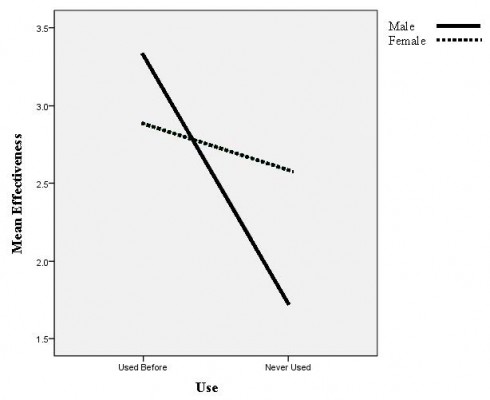

A 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the effects that gender and students’ experiences with counseling services had on students’ perceptions of counseling services. Levene’s test and Fmax indicated that the homogeneity of variances assumption was met. A statistically significant interaction effect was found between gender and whether or not the students had received counseling services, F(1, 133) = 5.923, p = .016. As shown in Figure 1, the relationship between whether or not students had received counseling services and their perceptions of school counselors differed depending on gender. Among students who had had individual meetings with their counselors, males rated the counselors higher than females did, while females rated the counselors higher than males did if they had never received counseling services.

Figure 1. Mean differences on gender and whether or not students received counseling services.

Discussion

In this study, almost half of the participants reported seeking help from a school counselor at least once. Interestingly, over 60% of the students who had met with a counselor had not returned for a subsequent meeting. Although China has seen the presence of school counselors increase in urban schools, it is still not common for students to seek counseling services (Thomason & Qiong, 2008). While the specific reasons why the students discontinued meeting with school counselors in this study are not clear, the following factors might help explain this phenomenon: (a) students have been found to be most concerned with physical health and to have failed to consider other aspects of health such as mental/psychological, behavioral and social (Wang, Zou, Gifford, & Dalal, 2014); (b) stigma toward mental illness exists among Chinese students (Thomason & Qiong, 2008; Wang, Huang, Jackson, Chen, & Laks, 2012); (3) Chinese cultural beliefs promote solving family-related issues inside one’s own family (Cook et al., 2010); and (4) students spend the majority of their time preparing for the National College Entrance Exam (NCEE), which Chinese school counselors perceived as an impediment to students’ utilization of school counseling services and future school counseling development in China (Leuwerke & Shi, 2010).

As for the modal number of counseling sessions that school counselors hold in secondary schools in China and the United States, little is presented in the current literature. More research has been conducted on college students’ attendance of counseling sessions offered by university counseling centers. For example, Draper, Jennings, Baron, Erdur, and Shankar (2002) found that, on average, college students met with counselors only three times. A number of studies have confirmed that most college students attend only a few sessions and that 50% terminate counseling prematurely (Ledsky et al., 2000; Renk, Dinger, & Bjugstad, 2000; Whipple et al., 2003). The number of counseling sessions that school counselors have with high school students could be likewise related. Students who visit school counselors by referral normally do not return for a second session, even though more sessions are indicated (E. Zhang, personal communication, June 5, 2007).

In China’s current school system, homeroom teachers have close, day-to-day interaction with students in their own homerooms; these teachers are responsible for students’ behavior, academic performance, mental health and all-around development (Lim et al., 2010; Shi & Leuwerke, 2010). Homeroom teachers may refer students to school counselors if they feel that students’ problems are beyond the teachers’ ability to solve (E. Zhang, personal communication, June 5, 2007). Future research could help explain why students tend to meet with their counselor only one time, and could explore the factors associated with students’ premature termination. It might be that Chinese counselors are giving an intentional or unintentional message that only one session is appropriate. Additional research is necessary to explore how school counselors could reach out to more students and reduce the stigma attached to mental problems, which might encourage more students to utilize individual counseling in school settings.

The descriptive results of this study provide some preliminary information about the level of students’ satisfaction with particular areas. Based on the students’ perceptions in two high schools in Beijing, it appears that school counselors are doing quite well in many different areas, such as friendliness and approachability to students, ability to explain things clearly, and availability. However, there are some areas in which school counselors must improve their knowledge and skills (e.g., college admission, vocational information and opportunities, achievement tests). When interpreting the results of this study, it is important to keep in mind that participants in this study are all from top-ranking high schools in Beijing, where students have a general college-going mindset and therefore place significant emphasis on academic achievement; in addition, these students have a higher expectation and interest in seeking counseling services related to applying for college. Also, in the current school systems in China, homeroom teachers are normally in charge of handling students’ academic testing, disseminating college-related information and helping students prepare for college (Shi & Leuwerke, 2010). Therefore, school counselors might not be as prepared as homeroom teachers to provide information regarding college admission and achievement tests.

As for the low ratings in the area of vocational information and opportunities, it is critical to consider the fact that the practice and profession of career counseling is still in the developmental stage in China (Leuwerke & Shi, 2010; Zhang, Hu, & Pope, 2002). Unfortunately, a thorough literature search revealed no information on the current conditions of school counselors’ training in China. However, a few studies have briefly mentioned the training or education that school counselors receive. For example, Gao et al. (2010) conducted a national survey on professional training experience among mental health practitioners in China, with only half of their sample working in educational settings such as high schools and universities. The researchers found that mental health practitioners reported receiving only short-term training and continuing education that focused on theories; a majority reported receiving no supervision or case consultation (Gao et al., 2010). Although there is a lack of literature on school counselors’ training in particular, several authors have indicated an urgent need for a more regulated, comprehensive and standardized training and qualification system for school counselors in China (Cook et al., 2010; Leuwerke & Shi, 2010; Lim et al., 2010; Thomason & Qiong, 2008).

It was expected that students who had had individual meetings with school counselors would rate counseling services differently than the students who had never seen school counselors individually. Students who had received counseling services before rated school counselors at a significantly higher level than students who had never had counseling services in many different areas, including the school counselors’ test skills, approachability, understanding, advocacy, promptness, ability, reliability, availability and overall effectiveness in providing counseling services. This finding is not surprising, considering that students who have had personal contact with the school counselors might have a better understanding of the role of school counselors and the services they provide, and therefore are more likely to give a higher rating of school counseling services. In a study conducted in Turkey, Yüksel-Şahin (2008) also found that the factor of whether students had met with school counselors was a significant predictor of students’ evaluations of counseling guidance service.

Similarly, gender differences were expected in students’ rating of school counselors. The results show significantly higher ratings from female students than male students of school counselors’ availability. From the descriptive results of this study, one can see that female students reported more contact with school counselors than male students did; this finding might help explain female students’ higher rating of school counselors’ availability.

Finally, an interaction effect was found in students’ ratings of the effectiveness of their counselors in the 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA based on gender and whether or not students seek counseling services. In a 2009 study, Hou, Zhou, and Ma examined high school and university students’ expectations of counseling in China. Results of their study showed that female students had significantly higher scores than males in terms of their own openness and counselors’ acceptance. Meanwhile, the researchers also found that students who did not have counseling experience had significantly lower scores on their motivation compared to their counterparts. These trends continued in the current study, which further supports the idea that students’ previous counseling experiences and gender relate closely to their expectations and perceptions of counselors and counseling services in general.

As a developing profession facing a huge student population, school counselors in China are doing a more than adequate job with limited resources. In the current study, most high school students reported seeking counseling services from their school counselors more than once, and they reported having generally positive experiences in counseling. Meanwhile, these students also had positive perceptions of their school counselors’ services; however, they reported the need for more vocational guidance or more knowledge of achievement tests from their counselors. An interaction effect was found in students’ perceptions of school counseling services based on students’ gender and whether they had met with school counselors before.

Implications

This study contributes to the literature by filling a research gap in Chinese students’ utilization and perceptions of school counseling. This line of inquiry is very important for the future development of the school counseling profession in China in that it provides implications for researchers and school counseling practitioners, as well as counselor educators. Future researchers could further investigate factors that might predict students’ utilization of school counseling services and what students need the most from counseling. More efforts need to be made in both conducting empirical research in the school counseling field and in exploring ways to improve the profession that will suit China’s cultural and social situations (Jiang, 2005; Thomason & Qiong, 2008). Moreover, the findings from this research are informative for school counseling practitioners in China. Chinese school counselors may want to self-evaluate their services and seek further training and education to improve their services in the areas that students rated lower. School counselors also could explore ways to make their services more accessible for students. Finally, the results of this research can be beneficial for counselor educators, who could contribute to improving the quality of school counselors’ training and education by providing opportunities for supervision, practice and professional development courses targeting the knowledge and skills that school counselors need most.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations in this study that limit generalization and call for additional research. First, the sample in this study was a convenience sample; the majority of the participants were from one high school, also limiting the generalizability of the results. Second, the two high schools are similar to each other in that they are top-ranking high schools in Beijing, and their students have similar future plans. Therefore, the results of this study may not apply to other geographic areas in China, especially rural areas, because a difference exists in educational conditions between economically developed areas (e.g., Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou) and underdeveloped areas (e.g., rural areas in West China). Students from different geographical areas in China may encounter different mental health problems, and the development of school counseling in urban and rural China may be different (Yan, 2003). The position of school counselor may not even exist in some areas in China. Third, the sample lacks diversity in terms of gender and grade level. Most of the participants in this study were female students and senior 2 students. Gender may be a variable that influences how students perceive counseling and school counselors. Future research utilizing more diverse and larger samples from across the country will be able to provide a more detailed and general picture of school counseling in high schools across China. Lastly, the instrument used in this study was adapted from an instrument that was developed several decades ago. Although some modifications were made, the validity and reliability of the scale used for Chinese students are not clear at this time. Future studies may investigate the validity and reliability of this instrument and also develop new instruments that are specially designed to measure students’ perceptions of Chinese school counselors’ effectiveness, competence, expertise and contributions.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

Chang, D. F., & Kleinman, A. (2002). Growing pains: Mental health care in developing China. Yale-China Health Studies Journal, 1, 85–98.

Cook, A. L., Lei, A., & Chiang, D. (2010). Counseling in China: Implications for counselor education preparation and distance learning instruction. Journal for International Counselor Education, 2, 60–73.

Corbin Dwyer, S., & McNaughton, K. (2004). Perceived needs of educational administrators for student services offices in a Chinese context: School counselling programs addressing the needs of children and teachers. School Psychology International, 25, 373–382. doi:10.1177/0143034304046908

Cyranoski, D. (2010). China tackles surge in mental illness. Nature, 468, 145. doi:10.1038/468145a

Davey, G., & Zhao, X. (2012, November). Counseling in China. Therapy Today, 23(9), 12–17.

Ding, Y., Kuo, Y.-L., & Van Dyke, D. C. (2008). School psychology in China (PRC), Hong Kong, and Taiwan: A cross-regional perspective. School Psychology International, 29, 529–548. doi:10.1177/0143034308099200

Draper, M. R., Jennings, J., Baron, A., Erdur, O., & Shankar, L. (2002). Time-limited counseling outcome in a nationwide college counseling center sample. Journal of College Counseling, 5, 26–38. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1882.2002.tb00204.x

Fei, X. (2006, October 16). The cause of and solution for mental diseases in China. The Epoch Times. Retrieved from http://www.theepochtimes.com/news/6-10-16/47113.html

Gao, X., Jackson, T., Chen, H., Liu, Y., Wang, R., Qian, M., & Huang, X. (2010). There is a long way to go: A nationwide survey of professional training for mental health practitioners in China. Health Policy, 95, 74–81. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.11.004

Guthrie, D. (2012). China and globalization: The social, economic and political transformation of Chinese society (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Hou, Z.-J., & Zhang, N. (2007). Counseling psychology in China. Applied Psychology, 56, 33–50. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00274.x

Hou, Z.-J., Zhou, S.-L., & Ma, C. (2009). Preliminary research on high school and university students’ expectation about counseling. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 17, 503, 515–517.

Hu, S. (1994). Gao zhong sheng xin li jian kang shui ping ji qi ying xiang yin su de yan jiu [A study of the mental health level and its influencing factors of senior middle school students]. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 26, 153–160.

Ji, J. (2000). Suicide rates and mental health services in modern China. Crisis, 21, 118–121.

Jiang, G. (2005). Zhong guo da lu zhong xiao xue xin li fu dao fa zhan ping su [The development of school counseling in the Chinese mainland: A review]. Journal of Basic Education, 14, 65–82.

Larkin, P. J., de Casterlé, B. D., & Schotsmans, P. (2007). Multilingual translation issues in qualitative research: Reflection on a metaphorical process. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 468–476. doi:10.1177/1049732307299258

Ledsky, K. M., Reynolds, E. V., III, Weissman, M. S., Ball, J. D., Rabinowitz, M., Collins, C., . . . Mansheim, P. (2000). Practice patterns for the outpatient treatment of depression in a case-managed delivery system: A utilization study. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31, 543–546.

Leuwerke, W., & Shi, Q. (2010). The practice and perceptions of school counsellors: A view from urban China. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 32, 75–89. doi:10.1007/s10447-009-9091-3

Lim, S.-L., Lim, B. K. H., Michael, R., Cai, R., & Schock, C. K. (2010). The trajectory of counseling in China: Past, present and future trends. Journal of Counseling and Development, 88, 4–8.

Liu, C., Munakata, T., & Onuoha, F. N. (2005). Mental health condition of the only-child: A study of urban and rural high school students in China. Adolescence, 40, 831–845.

Ma, H. (2012). Integration of hospital and community services—the “686 Project”—is a crucial component in the reform of China’s mental health services. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 24, 172–174.

McCullough, C. W. (1973). Student perceptions of counselor services in junior and senior public high schools of Montgomery County, Maryland. Dissertation Abstracts International, 34(5A), 2308.

Phillips, M. R., Zhang, J., Shi, Q., Song, Z., Ding, Z., Pang, S., . . . Wang, Z. (2009). Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: An epidemiological survey. The Lancet, 373, 2041–2053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7

Renk, K., Dinger, T. M., & Bjugstad, K. (2000). Predicting therapy duration from therapist experience and client psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 1609–1614.

Shi, Q., & Leuwerke, W. C. (2010). Examination of Chinese homeroom teachers’ performance of professional school counselors’ activities. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11, 515–523. doi:10.1007/s12564-010-9099-8

Tang, Y. (2006, June 8). Children at risk. Beijing Review, 49(23), 25–27.

Thomason, T. C., & Qiong, X. (2008). School counseling in China today. Journal of School Counseling, 6.

Tse, S., Ran, M. S., Huang, Y., & Zhu, S. (2013). The urgency of now: Building a recovery-oriented, community mental health service in China. Psychiatric Services, 64, 613–616.

Wang, G. (1997). The homeroom teacher’s role in psychological counseling at school. Proceedings of the International Conference on Counseling in the 21st Century. China, 6, 87–92. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED439325)

Wang, S. M., Zou, J. L., Gifford, M., & Dalal, K. (2014). Young students’ knowledge and perception of health and fitness: A study in Shanghai, China. Health Education Journal, 73, 20–27. doi:10.1177/0017896912469565

Wang, W., & Miao, X. (2001). Chinese students’ concept of mental health. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 23, 255–268.

Wang, X., Huang, X., Jackson, T., Chen, R., & Laks, J. (2012). Components of implicit stigma against mental illness among Chinese students. PLoS ONE, 7, e46016.

Whipple, J. L., Lambert, M. J., Vermeersch, D. A., Smart, D. W., Nielsen, S. L., & Hawkins, E. J. (2003). Improving the effects of psychotherapy: The use of early identification of treatment and problem-solving strategies in routine practice. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 59–68. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.50.1.59

Wong, W. C., Chen, W. Q., Goggins, W. B., Tang, C. S., & Leung, P. W. (2009). Individual, familial and community determinants of child physical abuse among high-school students in China. Social Science & Medicine, 68, 1819–1825. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.001.

Worrell, B. J. (2008, February 15). Mental health master plan. China Daily. Retrieved from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2008-02/15/content_6458887.htm

Wu, P., Li, L. P., Jin, J., Yuan, X. H., Liu, X., Fan, B., . . . Hoven, C. W. (2012). Need for mental health services and service use among high school students in China. Psychiatric Services, 63, 1026–1031.

Xin, Z., & Zhang, M. (2009). Changes in Chinese middle school students’ mental health, 1992–2005: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 41, 69–78.

Yan, H. (2003). Wo guo zhong xiao xue xin li jian kan jiao yu jiao shi de xian zhuang ji qi dui ce [Current status and strategies of elementary and secondary mental health education teachers in our country]. Jianghan Da Xue Xue Bao-Ren Wen Ke Xue Ban, 22(5), 77–80.

Yüksel-Şahin, F. (2008). Evaluation of school counseling and guidance services based on views of high school students. International Journal of Human Sciences, 5(2), 1–26.

Zhang, W., Hu, X., & Pope, M. (2002). The evolution of career guidance and counseling in the People’s Republic of China. The Career Development Quarterly, 50, 226–236. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2002.tb00898.x

Zheng, R., Zhang, W., Li, T., & Zhang, S. (1997, May). The development of counseling and psychotherapy in China. In The International Conference on Counseling in the 21st Century. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED439312.pdf

Zhong guo jiao yu bu (1999). Guan yu gai shan zhong xiao xue xin li jian kang jiao yu de ji dian yi jian [Several suggestions on improving mental health education in elementary & secondary schools]. Retrieved from http://www.jylw.org/jiankangjylw/20847.html

Zhong guo jiao yu bu . (2012). Zhong xiao xue xin li jiang kang jiao yu zhi dao gang yao (2012 xiu ding) [The guideline of mental health education in elementary & secondary schools (2012 Ed)]. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s3325/201212/145679.html

Qi Shi is an assistant professor at Loyola University Maryland. Xi Liu is a doctoral student at George Washington University. Wade Leuwerke is an associate professor at Drake University. Correspondence can be addressed to Qi Shi, 2034 Greenspring Drive, Timonium, Maryland 21093, qshi@loyola.edu.

Dec 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 5

Isaac Burt

This pilot study explored differences between the levels of anger expression and anger control by adolescent males and females. Eighteen participants (9 males and 9 females) completed a strength-based anger management group promoting wellness. Anger management group counseling consisted of a 10-week continuous intervention emphasizing anger reduction, anger control and appropriate anger expression. Results indicated gender differences in that females exhibited more anger expression, as well as less anger control. However, females had higher levels of overall improvement. The article concludes with limitations and implications for mental health counseling with adolescent populations.

Keywords: mental health counseling, group counseling, anger management, adolescent, gender differences

The profession of mental health counseling serves a diverse population with a variety of needs, including substance abuse and anger management issues (Gutierrez & Hagedorn, 2013). In order to provide services to clients, mental health counselors use a number of modalities, such as individual and group counseling. Research indicates that group counseling in particular can be useful with certain populations, such as excessively angry clients (Burt, Patel, Butler, & Gonzalez, 2013; Fleckenstein & Horne, 2004). Traditionally, anger management groups have focused on dealing with anger after it occurs. Recent developments in the field of counseling, however, suggest that a number of new trends are developing with mental health and anger management groups (Burt & Butler, 2011).

One of these trends focuses on early prevention with mental health counselors either providing facilitation or training others to facilitate anger management groups in schools (Curtis, Van Horne, Robertson, & Karvonen, 2010). The targeted clients of most of the early prevention interventions are middle and high school populations (Parker & Bickmore, 2012). Burt and Butler (2011) contended, however, that many early prevention and anger management groups are gender biased and focus excessively on adolescent males. The researchers suggested that while adolescent females experience anger as well, they often do not receive counseling services (Burt & Butler, 2011). As a result, a growing population with similar needs is potentially neglected. While numerous differences do exist between genders, anger is a common emotion experienced by both (Karreman & Bekker, 2012).

Research indicates that differences exist between adolescent males and females with regard to behavioral decision-making processes and expression of emotions (Brandts & Garofalo, 2012). Although research depicts females as more emotionally expressive, males have a reputation of being more predisposed to anger. According to Sadeh, Javdani, Finy, and Verona (2011), females experience anger, but may express it differently than males. For example, instead of expressing anger by striking objects, adolescent females may talk to friends or peers (Fischer & Evers, 2011). Conversely, other studies purport that females express anger similarly to males, but experience difficulty recognizing and admitting the emotion due to social expectations and constraints (Karreman & Bekker, 2012). Males, on the other hand, tend to display anger more commonly and comfortably (Fischer & Evers, 2011). One of the many reasons that adolescent males may feel comfortable expressing anger is because it is socially acceptable (Burt et al., 2013).

An extensive number of studies have investigated anger; however, there appears to be a lack of studies exploring anger differences between genders. Karreman and Bekker (2012) conducted a study on gender differences, investigating autonomy-connectedness between genders. Their study indicated differences related to anger and sensitivity between genders. However, the study did not attempt to determine whether males and females were equal in anger at the beginning or end of the study. Similarly, Burt, Patel, and Lewis (2012) reported that incorporating social and relational competencies into anger management groups reduced anger, but there was no discussion of anger differences between genders. Sadeh et al. (2011) indicated that women expressed more self-anger (i.e., anger directed internally toward themselves) than males, but did not investigate whether differences existed between genders before the study.

Although limited, a small number of studies have attempted to examine anger differences between genders. Similar to Sadeh et al. (2011), Fischer & Evers (2011) found that females expressed subjective anger, or self-anger, more often than males. Buntaine and Costenbader (1997) found that both genders’ self-reports (assessments) indicated no significant differences. Upon further examination of their data, however, they concluded that although self-reports specified no differences, males verbally reported higher responses of anger. In contrast, Zimprich and Mascherek (2012) determined that no anger differences existed between males and females. They declared that although genders may express anger and respond to situations differently, they generally experience similar levels of anger. As can be seen from the preceding studies, inconsistences exist in the literature. Contradicting studies indicate that researchers are unclear as to whether differences in anger exist between genders. As such, a research gap has emerged that needs to be filled (Zimprich & Mascherek, 2012). In order to understand how this research gap developed, it is necessary to examine cultural influences.

Cultural Influences and Misconceptions in Society

According to Carney, Buttell, and Dutton (2007), a misconception exists in Western society that women are less aggressive than men and do not express excessive anger. This fallacy persisted in Western culture until a report from the U.S. National Family Violence Survey of 1975 (as cited in Carney et al., 2007) found a disturbing trend: Females were just as angry as males and expressed excessive anger the same amount that men did. At the time, feminist theory and the feminist movement were developing and stood in stark contrast to these findings. Carney et al. (2007) stated that as such, the National Family Violence Survey findings were largely unreported, and in extreme situations, people reinterpreted or repudiated the survey’s findings. In either case, more misconceptions began to develop in Western culture (Carney et al., 2007), such as the idea that when females experience anger, it is always appropriate to the situation (i.e., anger is permissible). A second mistaken belief is that anger from females is less serious and not as negative. For example, the expression “you look so cute when you’re angry” portrays this biased and potentially chauvinistic thought. A third misconception is that females are more credible in reporting their emotions and, as such, females are more reliable when they state that they are not angry.

Western society has acted upon these cultural misconceptions. For example, certain myths in society (and mental health counseling) persist, declaring the following: (a) only males have angry feelings, (b) all male-comprised counseling groups are anger management groups, (c) males have a limited repertoire of emotions to express, (d) males are too angry and competitive to support one another in groups, and (e) males are not interested in meeting with other males (Andronico & Horne, 2004). Myths about female groups are that they are high functioning, conflicts are resolved faster, and a fair amount of reflection and processing exists (Gladding, 2012). According to researchers, these misconceptions can bias the truth regarding people’s beliefs. For example, Winstok (2011) stated that rates of excessive anger and intimate partner physical abuse among females equal or surpass those of males.

Clearly, cultural misconceptions of gender differences in excessive anger can lead mental health counselors to do a disservice to males and females alike. For example, culture can influence mental health and group counseling by causing a type to develop. This type is defined as best suited to be in anger management groups. As a result, mental health counselors may unconsciously choose more males than females to be members of anger management groups. Thus, a population that desperately needs services can go without an intervention (Carney et al., 2007). Mental health counselors need to reevaluate their thinking in order to avoid overlooking a population needing services due to implicit social misconceptions.

Bandura (2008a) believed that excessive anger was not sudden, but gradually manifested over time. His studies with youth corroborated this idea, as he observed modeling and negative behavioral patterns leads to excessive anger (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1963). Supporting Bandura’s work, Burt and Butler (2011) asserted that excessive anger begins in childhood and adolescence. They reinforced the notion that mental health counselors must be aware that both genders have common needs and issues. For females, not receiving services or having services denied, and being told that the emotion they feel is inappropriate, could cause personal damage (Gottfredson, 2002). For instance, society and mental health counselors often depict males as more in need of anger management (Burt & Butler, 2011). Conversely, mental health counselors sometimes neglect and ignore what females need (West-Olatunji et al., 2010). Stated succinctly, a gap exists between what clients need and the options mental health counseling interventions offer to both genders. It is the author’s contention that this gap is an unfair practice, as both genders have similar needs. Research has shown that males and females experience anger equally; as a result, both need anger management groups.

To determine whether both genders expressed anger similarly, the author implemented a pilot study with adolescents to explore the topic before proceeding with a full investigation. As Bandura (2008b) pointed out, anger begins early in life and timely prevention is critical. Provision of early services for children and adolescents can help to prevent issues later in life.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were male and female middle school students in the sixth, seventh and eighth grades. Thirty potential participants (15 males and 15 females) received invitations for participation, and 20 returned signed parental informed consent forms (10 males and 10 females). Ages of participants ranged from 11–14 years and consisted of 75% Latino/Hispanic (15), 15% Black (3), and 10% White (2). Two participants did not complete the study.

Instrumentation

This pilot study used the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 Child and Adolescent (STAXI-2 C/A). A well-known and highly used instrument, the STAXI-2 C/A is a self-report assessment that indicates youths’ (ages 9–18) control and expression of their anger (Spielberger, 1999). The STAXI-2 C/A has provided reliable and consistent results across diverse cultures and settings (Chirichella-Besemer & Motta, 2008). The STAXI-2 C/A contains four scales assessing excessive anger in youths. The four scales are as follows: Anger State (S-Ang), Anger Trait (T-Ang), Anger Control (AC) and Anger Expression (AX). Each of the four scales measures a different indicator of anger, in order to provide counselors with a multifaceted perspective of the client’s anger behavior.

Past studies that utilized the STAXI-2 C/A focused on AC and AX because of the strong validity these scales have with other anger assessments (Freeman, 2004); thus, the AC and AX scales were used in this pilot study. Cronbach’s alphas were .92 and .67 for AC and AX respectively (Freeman, 2004). Barrio, Aluja, and Spielberger (2004) stated that Cronbach’s alphas demonstrated by the STAXI-2 C/A indicated a high degree of reliability. Additionally, Barrio et al. (2004) also exhibited high construct validity by correlating the STAXI-2 C/A with the Verbal and Physical Aggressiveness Scale (AFV; Caprara & Pastorelli, 1993). A significant correlation of .43 existed between the two assessments. According to Gladding (2012), numerous counselors fail to measure the successfulness of their groups accurately because of errors in measurement and evaluation. In groups, a large number of therapeutic factors are occurring, which affect members in varying ways (Corey, 2011). Focusing on too many factors can overwhelm counselors and undermine evaluation, which is critically important (Gladding, 2012). In order to avoid this potential problem, this pilot study focused on a limited number of factors.

Procedures

A large, urban public middle school in a metropolitan area provided the setting and participants for this pilot study. Serving 2,000 students in grades 6–8, the school has a standardized documentation system that keeps track of behavioral disruptions. The documentation system records in-school suspensions (ISS), out-of-school suspensions (OSS) and behavioral infractions for students (Burt, 2010). Each student has a personal identification number; the administration connects student infractions to these numbers in order to identify any student. The documentation system also contains a small description of what caused the issue. For instance, some students have behavioral outbursts of anger, while others have infractions for tardiness. Since the focus of this pilot was to determine anger differences between genders, it was imperative for the study to have participants who displayed excessive anger. To increase validity and correctly identify participants, the author used school administration recommendations.

The author conducted interviews with school staff to gather information as suggested by Bryan, Day-Vines, Griffin, and Moore-Thomas (2012). For example, the author asked school deans, teachers and professional school counselors (PSC) for recommendations about students. Many students had a high overall number of OSS and ISS, including a large number of behavioral infractions. However, some infractions were due to nonexcessive anger problems (e.g., tardiness). School staff could provide a safeguard against the author inappropriately recruiting a student who did not truly require services. The author asked school staff if a student’s number of OSS, ISS and infractions corresponded with actual behavior (i.e., excessive anger). Thus, the goal was to eliminate as much bias as possible to ensure the most appropriate candidates.

After interviewing school staff, a pool of candidates emerged, consisting of individuals with documentation of excessive anger, fights and legal procedures in the court system (Burt, 2010). School staff considered these candidates to be at high risk for excessive anger, and candidates’ records of OSS, ISS and behavioral infractions corroborated this belief. According to Burt et al. (2013), more than eight occurrences in a 12-week period constitute a high number of anger issues; thus, this study held the same parameters advocated by Burt et al. (2013). Once a list of eligible candidates emerged, the author interviewed school staff a second time. This second short interview was a safeguard measure before actually contacting candidates. The author wanted to meet with school staff again to reduce potential staff bias and ensure that candidates were still having anger issues. After the last interview, school staff explained the study to candidates in detail.

In order to increase client buy-in, school staff introduced the author of this article (who was also the group facilitator) to candidates. The author met with candidates and explained the study in more detail, in addition to answering any questions. If the candidates were interested in participating, the author gave them informed consent forms to have their parents sign. To increase the likelihood of the candidates returning the informed consent forms, candidates received tokens from the school, which allowed them to buy goods in the school store. If candidates returned signed informed consent forms, they received five tokens, comparable to five U.S. dollars. Out of 30 candidates, 20 returned signed informed consent forms. Although this is a small number, this quantity is permissible for pilot studies (Heppner, Wampold, & Kivlighan, 2008). The author split the participants in half based on gender (10 males and 10 females). One participant dropped out of each group, leaving 18 who completed the study. Each group met at a different time and was not aware of the existence of the other group (Burt, 2010). This pilot study assessed participants’ behavior via the STAXI-2 C/A, given pre- and post-intervention.

Structure of the intervention/anger management group used in the pilot study. The anger management group consisted of eight counseling sessions and two assessment sessions (pretest and posttest assessment; Burt, 2010). Program duration was 10 weeks, and the author of this article conducted each session weekly. Corresponding with Blanton, Christensen, and Shakir (2006), each counseling session contained the following four essential components: an opening question (such as an icebreaker or introductory segment), a behavioral lesson (information gathering and learning), a behavioral activity (an experiential segment in which learned information is applied), and an appreciations and closings segment ending the group (a bonding piece for group members). Counseling sessions concluded after 60 minutes, with opening questions lasting approximately 5–10 minutes. Behavioral lessons took between 10 and 25 minutes and behavioral activities lasted 15–30 minutes. Appreciations and closing concluded after 5–10 minutes. Pre- and post-group paperwork sessions took approximately 15–30 minutes (Burt, 2010). As Burt et al. (2012) suggested, groups must be strength-based (i.e., accentuating members’ strong points), and incorporate collaboration and teamwork. The group was prosocial in nature, emphasized clients’ strengths and developed social bonding. Topics for the eight sessions included the following: improving communication skills, recognizing personal emotions, identifying emotions within others, improving observational skills, advanced detection of emotions in others, noticing anger cues in others, understanding personal anger cues, strategies for calming down, and problem-solving.

Mental health counselor for the intervention. The mental health counselor for both groups was this author, who has experience as a group facilitator and counselor educator. Additionally, the author worked as a training liaison for anger management groups in the school system, teaching conflict resolution and peer mediation. He also has experience working with groups for adults and children with oppositional defiance disorder and anger management issues. The group facilitator used an integrative orientation, utilizing social cognitive theory (SCT) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT; Burt, 2010).

Results

The focus of the study was to determine whether differences existed between male and female levels of excessive aggression. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics and indicates results from the one-way repeated measures ANOVA for AC and AX. Results for youths’ overall AC levels pre- and post-intervention indicated the following, F1, 8 = 6.36, p = .003, ES = .44. Thus, the pilot study showed preliminary findings that a significant difference existed between genders on AC. For the scale of AX, results indicated a statistically significant difference between genders pre- and post-intervention (F1, 8 = 4.06, p = .018, ES = .34). Although repeated measures indicated a statistically significant difference between genders, pair-wise comparisons allowed examination of exactly where differences lay between genders on AC and AX. Thus, a significant difference existed between gender on AC (p = .04), and on AX (.03; Table 1). At the beginning of the pilot study, males had less AC, but females had more AX. However, females had the larger increase in AC post-intervention, as well as the greatest reduction in AX between genders. Hence, females had the greater overall gains and improvement pre- and post-intervention as opposed to males.

Table 1

Outcome results for Anger Control and Anger Expression

|

Pretest

|

|

Posttest

|

|

Males

|

|

Females

|

|

|

|

|

|

Males

|

|

Females

|

|

|

|

M (SD)

|

|

M (SD)

|

df

|

P

|

F

|

ES

|

|

M (SD)

|

|

M (SD)

|

df

|

P

|

| Repeated Measures ANOVA a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Anger Control |

44.22

(12.76)

|

|

51.56

(4.33)

|

8

|

.003

|

6.36

|

.44

|

|

50.00

(14.00)

|

|

63.33 (7.85)

|

8

|

|

| Anger Expression |

18.78

(5.58)

|

|

24.67

(3.87)

|

8

|

.018

|

4.06

|

.34

|

|

17.44

(5.50)

|

|

20.67

(2.74)

|

8

|

|

| Pair-Wise Comparisons b |

|

|

|

|

.04

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.03

|

Note. a N = 9 b N = 18

Discussion

Females had more AX than males, a finding which corresponds with Cross and Campbell (2011). Males appeared to have less AC and were somewhat less angry than females. A number of studies support the preceding findings, most notably Winstok (2011) and Carney et al. (2007). Further, this pilot’s findings corroborate the idea that both genders have equal problems with excessive anger (Carney et al., 2007). The results from this study also suggest that both genders can improve with interventions designed to address anger. According to Winstok (2011), a common misconception is that males have greater need for excessive anger interventions than females. However, in this pilot study, females responded better to the treatment than males did. This responsiveness to treatment is interesting in that few studies have directly compared sensitivity to interventions by gender. While sensitivity to treatment was not a focal point of this pilot, it is interesting to note and direct attention to this unexpected outcome.

The author believes that the primary underlying reason females responded better to the treatment is that they are an underserved population (West-Olatunji et al., 2010). This is not to say that other explanations are not contributing factors, but because the females in this study possibly represent an underserved population, the aforementioned factor likely has more influence. According to West-Olatunji (2010), an underserved population is one that needs services, but does not have access to help. In addition, a number of the females in this pilot qualify as an underserved population as defined by Burt and Butler (2011). For instance, background information provided by the school indicated that approximately 85% of males in this pilot study received prior services (e.g., counseling) before participating. Conversely, 40% of females in this pilot study received prior services. Although the purpose of this study was not to detail what causes an underserved population to develop, research indicates that it can be due to institutional, social or cultural constraints (West-Olatunji et al., 2010).

While this study did not use qualitative measures as advocated by McCarthy (2012), females verbally disclosed that the school rarely offers them anger management services. Female participants further stated that if those services were more readily available, they would use them. Conversely, males indicated being overwhelmed with staff attempting to persuade them to participate in anger management services. This dichotomy in access to treatment clearly marks the identification of an underserved population. Thus, the females’ higher responsiveness to the intervention is potentially due to the following: Perhaps this study was a first intervention for many of the female participants. For females who did receive prior services, it may have been the first intervention directly dealing with anger.

Day (2008) indicated three characteristics that clients need to increase the likelihood of a successful outcome: the client must be in distress, must actively seek help and must have high expectations for counseling. The female participants (as opposed to the majority of the males) in this study met the preceding three criteria. Members of both genders were in a state of distress (as evidenced by the school’s documentation system). However, females verbally admitted to wanting help and had higher expectations. Consequently, females in the pilot had larger, more consistent gains. As evidenced by West-Olatunji et al. (2010), when underserved populations receive desired treatments, the change is normally larger than average. Thus, the findings in this pilot study connect to previous research and provide a plausible reason for the differences between genders.

Limitations

This pilot study had limitations stemming from research methods. First, the groups were limited to one school, as well as to selection from a standardized school documentation system (Burt, 2010). The documentation system compiled an objective list of behavior issues in school, but did not differentiate between excessively angry and nonexcessively angry behaviors. For example, documented behaviors could range from threatening school staff to not returning school forms promptly. To account for this issue, this study included school staff and administration’s professional suggestions for possible candidates. However, school staff may have had subtle biases for or against certain students. There are limitations to each method of selection, including both the standardized documentation system and the school staff. An additional limitation is that the same mental health counselor (the author of this article) conducted the groups. Due to this limitation, some participants’ changes may be due to the facilitator’s style or personality. More importantly, this study lacked a control group and had a small number of participants. The lack of a control group makes generalizations difficult in that it is uncertain whether other extraneous variables influenced the results. Having a small number of participants decreases the power of the pilot study and makes it difficult to generalize results. However, the fact that a significant finding occurred with a small sample size indicates the strong influence of the intervention (Gay & Airasian, 2003). In schools, it is difficult to conduct full-scale studies due to a number of preexisting conditions, such as high-stakes testing (Burt et al., 2013). Therefore, having a study without a control group and with a small number of participants may be the most appropriate method if investigators are to conduct research in schools (Heppner et al., 2008).

Implications and Future Directions for Research

Implications for mental health counselors stemming from this pilot study are numerous. First, mental health counselors must be aware that both genders need services for excessive anger. Mental health counselors should not allow personal biases and media influences to sway professional opinion (Gladding, 2012). In addition, mental health counselors must advocate for fairness and oppose stereotyped biases and ideologies pushed by society (Burt et al., 2012). According to Gray and Rose (2012), discrimination and internalized oppression begin by ignoring discriminatory societal practices. Only by remaining reflective and cognizant of personal biases can mental health counselors reduce problematic issues and model appropriate behaviors (Young, 2012).

A second implication for mental health counselors is to understand that a strength-based model promoting wellness is critically important for clients (Hagedorn & Hirshhorn, 2009). Specific populations, such as youth, respond better to models incorporating empowerment, which can lead to increased behavioral self-efficacy (Bandura, 2008a). Furthermore, positive modeling by mental health counselors also increases growth and behavioral self-efficacy (Bandura, 2008a). A combination of strength-based approaches, empowerment and modeling improve groups’ interpersonal, intrapersonal and extrapersonal functioning (Gladding, 2012). Third, mental health counselors should seek to improve delivery of services and outcomes by evaluating the group process (Steen, 2011). For instance, Gladding (2012) and McCarthy (2012) reinforced the notion of improving counseling services through research and evaluation. This study provided a formal assessment of a group that could have otherwise gone unreported.

Future researchers may want to improve the overall research design. For example, researchers could include a larger number of participants, groups and multiple facilitators. Moreover, future studies must have a true experimental design, such as a control group with random assignment. Including participants’ personal perspectives and phenomenological views not only increases the validity of research, it improves mental health counselors’ skill levels as well (Gladding, 2012). Qualitative measures improve skill level by giving mental health counselors a clear idea of what actually worked and what did not (Burt & Butler, 2011). Lastly, future researchers may want to pay more attention to gender responsiveness (sensitivity) to treatments, to determine if males or females respond better to specific treatments.

Conclusion

The purpose of this pilot study was to determine whether gender differences existed among adolescents for excessive anger. Preliminary results indicate that differences existed, but that there also were distinctions between genders regarding the intervention itself. Females had better AC, but also had more AX compared to their male counterparts. However, females seemed to respond better to the intervention, as shown by their larger gains and improvement. Males improved as well, but did not have the substantial progress observed in females. While past research may not have lent strong support for gender differences, this author hoped to reinvigorate interest in gender discrepancies. Females are an underserved population with regard to anger management; research has indicated that they experience anger sometimes at a rate paralleling or surpassing males (Cross & Campbell, 2011). However, due to societal stigma and cultural biases, many females do not receive anger management services. Therefore, only rigorous research can determine whether these problems truly exist by improving group research and outcomes (McCarthy, 2012).

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The author reported no conflict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

Andronico, M. P., & Horne, A. M. (2004). Counseling men in groups: The role of myths, therapeutic factors, leadership, and rituals. In J. L. Delucia-Waack, D. A. Gerrity, C. R. Kalodner, & M. T. Riva (Eds.), Handbook of group counseling and psychotherapy (pp. 456–468). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bandura, A. (2008a). Reconstrual of “free will” from the agentic perspective of social cognitive theory. In J. Baer, J. C. Kaufman, & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Are we free? Psychology and free will (pp. 86–127). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bandura, A. (2008b). Toward an agentic theory of the self. In H. W. Marsh, R. G. Craven, & D. M. McInerney (Eds.), Self-processes, learning, and enabling human potential: Dynamic new approaches (pp. 15–49). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66, 3–11.

Barrio, V. D., Aluja, A., & Spielberger, C. (2004). Anger assessment with the STAXI-CA: Psychometric properties of a new instrument for children and adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 227–244. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2003.08.014

Blanton, E., Christensen, C., & Shakir, J. (2006). Empowering the angry child for positive leadership. Louisville, KY: Peace Education Program.

Brandts, J., & Garofalo, O. (2012). Gender pairings and accountability effects. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 83, 31–41. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2011.06.023

Bryan, J., Day-Vines, N. L., Griffin, D., & Moore-Thomas, C. (2012). The disproportionality dilemma: Patterns of teacher referrals to school counselors for disruptive behavior. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90, 177–190. doi:10.1111/j.1556-6676.2012.00023.x

Buntaine, R. L., & Costenbader, V. K. (1997). Self-reported differences in the experience and expression of anger between girls and boys. Sex Roles, 36, 625–637. doi:10.1023/A:1025670008765

Burt, I. (2010). Addressing anger management in a middle school setting: Initiating a leadership driven anger management group (Doctoral dissertation, University of Central Florida). Retrieved from http://etd.fcla.edu/CF/CFE0003375/Burt_Isaac_201008_PhD.pdf