Claudette Brown-Smythe, Shirin Sultana

We examined the extent to which anxious attachment and avoidant attachment predicted loneliness and social self-efficacy among 863 college students. Further, we investigated whether social self-efficacy mediated the relationships between the two insecure attachment styles and loneliness. Pearson correlations and regression analysis showed that anxious and avoidant attachment styles were significant predictors of loneliness and social self-efficacy. Mediation analysis revealed that social self-efficacy fully mediated the relationship between avoidant attachment and loneliness and partially mediated the relationship between anxious attachment and loneliness. Implications for college counseling are discussed, and we propose recommendations for counselors to enhance social self-efficacy and attachment security to decrease loneliness.

Keywords: social self-efficacy, anxious attachment, avoidant attachment, loneliness, attachment security

Existential philosophers, as well as counseling theorists, have alluded to loneliness as a common human condition, one that can lead to mental health challenges like depression and anxiety (Sharf, 2012). Researchers began calling attention to the increase in loneliness across the life span (Cacioppo et al., 2015; Diehl et al., 2018; Mushtaq et al., 2014) prior to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), and the subsequent declaration by the World Health Organization (WHO) that the outbreak was a public health emergency of international concern (Pan American Health Organization, 2020). In 2015, Vivek Murthy (2020), then surgeon general of the United States, identified loneliness as a public health issue, endemic across all ages and socioeconomic groups. As of 2019, three out of every five people, or 61% of the U.S. population, reported feeling lonely, which was a 7% increase from 2018 (Cigna, 2020). Isolation then surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, which contributed to loneliness (Dahlberg, 2021; Holt-Lunstad, 2020).

The Cigna (2020) report noted that 49.9% of emerging adults 18–22 years old and 47.7% of adults 23–37 years old reported feeling lonely. Moreover, the American College Health Association (2017) reported that 64% of college students experienced loneliness, which aligns with the Healthy Minds Study results indicating that 66% of college students struggled with loneliness (Eisenberg et al., 2020). Again, these figures predate the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, and rates of loneliness experienced because of the lockdown and restrictions during that time are projected to increase (Dahlberg, 2021; Holt-Lunstad, 2020).

As the preceding data demonstrate, loneliness is a special concern for the college-age population. Moreover, loneliness is a human challenge that if left unattended can lead to and exacerbate mental health issues. Like Bandura (1977), we believe that individuals who possess strong social self-efficacy can motivate themselves to build connections and engage with others and reduce feelings of loneliness. This study sought to examine the extent to which social self-efficacy serves as a mediator of the two insecure attachment styles on loneliness.

Literature Review

Loneliness

Loneliness is viewed as a complex multidimensional and subjective psychological construct that is seen from an individual’s perspective. DiTommaso et al. (2015) described loneliness as a temporary psychological response to changes in one’s social environment or a stable dissatisfaction with one’s personal network, while Perlman and Peplau (1981) viewed it as a negative feeling that occurs when individuals do not perceive the quality or quantity of their social relationships as satisfying.

Early researchers like Perlman and Peplau (1981) identified three types of loneliness: (a) chronic loneliness, or a long-term experience of feelings of separation and isolation over several years; (b) situation loneliness, or a disruption of one’s social relationship patterns; and (c) transient loneliness, described as the occasional feelings of loneliness experienced at different times when one is making changes throughout the life span. Yanguas et al. (2018) highlighted a dichotomous view of loneliness, identifying social loneliness (lacking a sense of community and connection to social network) and emotional loneliness (lacking attachment figures and companionship), and noting that an individual can experience loneliness in both areas simultaneously.

Loneliness as a developmental issue can occur at different periods in people’s lives. For example, for emerging adults (i.e.,18–25 years old) this period is marked by transitions that can predispose them to experiencing loneliness (Moeller & Seehuus, 2019). Emerging adults overlap two critical stages in Erikson’s (1980) psychosocial development theory. The first stage of identity versus role confusion (12–19 age range) is marked by a sense of ego identity in which the individual seeks balance and congruence between their self-perception and how others perceive them. The second stage is intimacy versus isolation (20–25 age range), in which the goal is to establish committed relationships with friends and develop intimate romantic relationships. Erikson posited that individuals who were unsuccessful at the earlier stages, and were lacking a strong sense of identity, may struggle in building healthy relationships. This in turn can result in emotional distress and isolations, as they will be unable to establish the committed relationships that are needed to resolve this stage and experience loneliness. There are normative transitions many emerging adults make that can precipitate feelings of loneliness, like leaving home, beginning college, or starting a full-time job. Additionally, the maturation changes from adolescence to emerging adulthood (Chickering & Reisser, 1993), along with the psychosocial development crisis of intimacy versus isolation, can impact emerging adults’ self-perception of loneliness (Qualter et al., 2015).

At the beginning of college, students may not have relationships with peers at their institutions and will need to establish connections in this new social context (Thurber & Walton, 2012). This new context may be bigger or smaller than home, or it may be less diverse or more diverse from their home communities, thereby decreasing students’ feelings of connection. Colleges often give much attention to transition issues experienced at the beginning of college (Bruffaerts et al., 2018); however, these experiences can persist throughout the college years. Moeller and Seehuus (2019) noted that students are challenged to build and sustain relationships in this social context while also navigating and balancing a more demanding academic workload, new expectations around academic productivity and engagement, and developmental changes as they transition from adolescence to adulthood. This period of transition and competing priorities can be challenging for students as they attempt new things, try to integrate, and adjust to the changes to their personal and academic lives and make decisions about what is important to them. For some, this can be overwhelming, and their inability to cope with these challenges and form meaningful relationships in this social context can precipitate students’ mental health struggles and loneliness (Thomas et al., 2020). Students’ struggles during this period are linked to attrition, college withdrawal, and dropout rates (Diehl et al., 2018; Fink, 2014).

Social Self-Efficacy

Bandura (1977) defined social self-efficacy as an individual’s beliefs about their skills for success in interpersonal interactions and social situations. He noted that individuals with high social self-efficacy had greater cognitive resourcefulness and flexibility to effectively manage their environment and motivate themselves to achieve a desired goal, which is the opposite for individuals with insecure attachment. Social self-efficacy, then, is about the individual’s perceived confidence in their ability to engage in social interactions and to take the initiative to maintain these interpersonal relationships. Consequently, higher social self-efficacy is important for building and maintaining interpersonal relationships and for engaging in social gatherings (Kim et al., 2020). These engagements can then help in staving off loneliness. People who are lonely are assumed to possess less interpersonal competence than individuals who are not lonely, and research often points to a positive correlation between poor social skills and loneliness (Moeller & Seehuus, 2019).

Attachment Theory

Attachment theory is an established framework that describes the impact of early bonding with caregivers as a foundation for subsequent close relationships across the life span (Ainsworth, 1985; Bowlby, 1973). These theorists posited two major attachment types: secure and insecure attachment. Available, sensitive, and supportive bonding experiences with caregivers contribute to a sense of connectedness and security resulting in the development of secure attachment and a healthy internal model of self and others (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014). That is, these experiences create a positive view of self and others.

On the other hand, individuals who experienced unsupportive, frustrated, and fractured caregiving emerge with insecure attachment styles, which lead to difficulties with relationships in later life. Insecure attachment is characterized in two dimensions—avoidant and anxious attachment styles. Individuals with high anxious attachment style tend to be fearful of being rejected or abandoned by others and have a negative working model of self; that is, they may hold a negative perception of their worthiness. Those with avoidant attachment fear intimacy and being dependent on others and hold a negative working model of others (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014; Zhu et al., 2016).

Individuals with insecure attachment styles may lack prosocial skills and engage in negative coping strategies (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014, 2019). For example, individuals with high anxious attachment may “rely on hyperactivating strategies . . . to achieve support and love,” and when the support and love are not provided, individuals may then experience anger and despair (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014, p. 36). Conversely, those with high avoidant attachment may use detachment and deactivated strategies to protect themselves; they tend to push others away, “avoiding closeness and interdependence in relationship” (p. 36). These maladaptive behaviors may result in greater feelings of loneliness, as these individuals may experience lower satisfaction in their relationships.

Loneliness, Attachment, and Social Self-Efficacy

The relationship between attachment styles established in early childhood and feelings of loneliness in early adulthood is well documented (Akdoğan, 2017; Benoit & DiTommaso, 2020; Klausli & Caudill, 2021). Higher levels of attachment security correlated with lower levels of loneliness in undergraduate students (Benoit & DiTommaso, 2020). As young adults transition to college life, their social network shifts from the family domain to peers. An individual’s ability to cope with this transition and form meaningful relationships may depend on the adaptiveness of their attachment style. Individuals with a secure attachment style report a stronger sense of self and social competence (Akdoğan, 2017; Klausli & Caudill, 2021), which may counteract feelings of loneliness.

Research on loneliness has frequently pointed to a lack of prosocial skills and social competency to initiate and maintain friendships when addressing the connection between insecure attachment and loneliness (Akdoğan, 2017). Individuals with secure attachment demonstrate strong social skills and social competency and can be said to possess social self-efficacy. “Adult attachment research revealed that attachment insecurities tended to negatively bias cognitions, emotions, and behavior during interpersonal interactions” (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014, p. 37); therefore, it could be concluded that individuals with attachment insecurities are likely to exhibit low social self-efficacy.

Earlier researchers found conflicting effects of social self-efficacy on loneliness (Mallinckrodt & Wei, 2005; Wei et al., 2005). The results of a longitudinal study of 308 freshmen examining social self-efficacy and self-disclosure as mediators for insecure attachment, loneliness, and depression revealed that a lack of social self-efficacy mediated the relationship between anxious attachment and loneliness after controlling for depression (Wei et al., 2005). However, social self-efficacy was not found to mediate avoidant attachment. In another study with 430 students investigating social self-efficacy as a mediator for insecure attachment, social support, and psychological distress, researchers found that high levels of avoidant attachment were correlated with lower levels of social self-efficacy and perceived social support (Mallinckrodt & Wei, 2005). These competing findings influenced us to further explore the extent to which social self-efficacy would affect loneliness.

The Current Study

For this study, we focused on social and emotional loneliness (Yanguas et al., 2018), holding the view that loneliness is a temporary psychological state due to circumstances (DiTommaso et al., 2015). These two dimensions are considered more salient for college students given their psychosocial developmental levels and societal expectations. Researchers (Akdoğan, 2017; Benoit & DiTommaso, 2020; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014, 2019) have indicated that primary attachment style impacts social competency, sense of self, and one’s ability to form a supportive network. All of these can affect whether college students experience loneliness and to what degree they experience it.

To date, few researchers have examined how the detrimental effects of loneliness in people with avoidant and anxious attachment styles can be mediated by social self-efficacy. In this study, we examined the triadic relationship between the dimensions of insecure attachment (i.e., anxious attachment and avoidant attachment), loneliness, and social self-efficacy. Three research questions and hypotheses guided this study:

- What is the relationship between social self-efficacy, loneliness, and the types of insecure attachment?

- Do anxious attachment and avoidant attachment predict the levels of social self-efficacy?

- How does social self-efficacy mediate the relationship between loneliness and anxious attachment and avoidant attachment styles?

We hypothesized that a) social self-efficacy, loneliness, and anxiety are correlated; b) anxious attachment and avoidant attachment will predict the levels of social self-efficacy; and c) social self-efficacy will mediate the relationship between loneliness and anxious attachment and avoidant attachment styles.

Methods

Procedure

Upon receiving IRB approval, we collected data during the last 2 months of the fall 2020 semester. At this mid-size comprehensive college in the Northeast, students were on campus until the week before Thanksgiving. After the Thanksgiving break, students were not permitted to return, and all classes transitioned to virtual platforms because of the uptick in the number of cases and deaths as a result of COVID-19. Data collection spanned both class formats. All students 18 years and older who were enrolled in classes for the fall 2020 semester were eligible to participate in this study. Data were collected through the Qualtrics online survey platform. The university enrollment management office distributed the recruitment email inviting students to volunteer to participate in the research. The students who volunteered completed the informed consent with the screening statement, “I am 18 years or older, currently enrolled in classes for the fall 2020 semester.”

Participants

Participants were drawn from 5,838 full-time students attending a medium-sized public college in the northeastern United States. After eliminating participants with more than 10% of missing values throughout the questionnaire (n = 28; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007) the final sample was N = 863 students. The participants’ ages ranged between 18 and over 40 years, with the majority (n = 79.9%) being between 18 and 25 years old. Of these 863 participants, 153 (17.7%) participants were first-year students, 105 (12.2%) participants were second-year students, 205 (23.8%) were in their third year, 182 (21.1%) were fourth-year students, 43 (4.9%) were fifth-year students (those who added one more year to complete the degree), 163 (18.9%) were graduate students, and 12 (1.4%) were non–degree-seeking students.

Regarding their cultural background, most participants (n = 689; 79.8%) were White European, whereas 51 (5.9%) were African American, 44 (5.1%) were Hispanic/Latinx, 20 (2.3%) were Asian, 17 (2.0%) were Caribbean/West Indian, 11 (1.3%) were Native American or Alaska Native, and two (0.2%) were Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Regarding gender, 647 (75%) identified as women, 197 (22.8%) as men, 6 (0.7%) as transgender, and 13 (1.5%) as other gender. Most of the participants identified as heterosexual (n = 611, 70.8%), whereas 117 (13.6%) identified as bisexual, 37 (4.3%) identified as asexual, 29 (3.4%) identified as lesbian, 12 (1.4%) identified as queer, and 11 (1.3%) identified as homosexual. The relationship status of the participants varied. Most of the participants were single (n = 375, 43.5%), whereas 361 (41.9%) were dating, 80 (9.3%) were married, 37 (4.3%) were engaged, and seven (0.8%) were divorced.

In terms of living arrangements, many participants (n = 204, 23.7%) lived on campus with suitemates, 201 (23.3%) lived with their parents/guardians, 190 (22.0%) lived with their partners or spouses, 102 (11.8%) lived alone, and 36 (4.2%) lived with a non-student roommate. Regarding religious affiliation, 336 (39.3%) of the participants identified as Christian, 250 (29.2%) identified as spiritual/not religious, 129 (15.1%) identified as agnostic, 103 (11.9%) identified as atheist, 11 (1.3%) identified as Buddhist, 11 (1.3%) identified as Jewish, 8 (0.9%) identified as Muslim, and 1 (0.1%) identified as Mormon.

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire consisted of 13 questions. These questions addressed age, gender, sexual orientation, class standing, enrollment status, race/ethnicity, and living arrangements. Additional questions asked about marital status, income, religion/spiritual practice, and employment.

UCLA Loneliness Scale

The UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3) is a 20-item scale measure of subjective feelings of loneliness and feelings of social isolation (Russell, 1996). Participants are asked to rate how often each of the positively and negatively worded statements describes them on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Sample items included, “How often do you feel that there are people that you can talk to?” and “How often do you feel that people are around you but not with you?” Scoring is done by reversing the positively worded items and then summing the scores on each item for a composite score ranging from 20 to 80, with higher scores (> 40) indicating greater degrees of loneliness. Version 3 has been widely used and validated with the college population as well as other adults in the United States and has yielded high reliability with alpha coefficient values ranging from .89 to .94 and test-retest reliability of .73 (Russell, 1996). In the current study, we followed Kalkbrenner’s (2023) recommendation and computed both Cronbach’s alpha value and coefficient omega, as the latter is a robust measure to alpha’s statistical assumptions. For the UCLA Loneliness Scale, both were the same value of .94, indicating strong reliability.

Social Self-Efficacy Scale

The Social Self-Efficacy Scale (SSES) is a 6-item measure subscale from the Self-Efficacy Scale (Sherer et al., 1982) that assesses students’ beliefs in their social competence. Items ask participants to respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to statements like “It is difficult for me to make new friends” and “I do not handle myself well in social gatherings.” Reverse scoring is done for the negatively worded items followed by summing the scores of all the items. A higher score indicates higher social self-efficacy. Researchers have indicated coefficient alpha values of .76 and .71 (Sherer et al., 1982; Wei et al., 2005). Construct validity for this measure has demonstrated correlations with measures of ego strength, interpersonal competency, and self-esteem (Sherer et al., 1982). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha value for the SSES was .60, while the coefficient omega value was .57. Because we used a subscale of the Self-Efficacy Scale, the poor internal consistency reliability estimates of the SSES might, in part, be due to the low number of questions (Tavakoli & Dennick, 2011). Nonetheless, this instrument was chosen because it is a widely used instrument for assessing social self-efficacy and has reported construct validity (Sherer et al., 1982).

The Experiences in Close Relationships—Relationship Structures Questionnaire

The Experiences in Close Relationships—Relationship Structures Questionnaire (ECR-RS; Fraley et al., 2011) is a 9-item measure used to assess attachment patterns with a variety of familiar relationships. For the current study, participants were asked to respond on the basis of close relationships in general as opposed to thinking about a specific person/relationship. The ECR-RS has two fundamental dimensions of underlying attachment patterns: anxious attachment and avoidant attachment. Sample items include “I usually discuss my concerns and problems with this person,” “I find it easy to depend on this person,” and “I worry this person may abandon me.” Participants rate the extent to which they believe each of the nine statements describes their feelings about their close relationships on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items 1, 2, 3, and 4 are reverse scored. Items 1 to 6 make up the Avoidance Attachment scale, and items 7 to 9 comprise the Anxiety Attachment scale (Fraley et al., 2011). Scores for each scale are derived from finding the average of the items.

Researchers noted Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities ranging between .83 and .87 for the Anxiety Attachment scale and .81 to .92 for the Avoidance Attachment scale across multiple domains (Fraley et al., 2011; Klausli & Caudill, 2021). Our study yielded a Cronbach’s alpha score of .88 and a coefficient omega score of .87 on the Avoidance Attachment scale and alpha .76 and omega .82 for the Anxiety Attachment scale. The ECR-RS has been normed on the college-age population, and Varghese and Pistole (2017) demonstrated the usefulness of this instrument with college students.

Data Analyses

SPSS (Version 27) was used to analyze the data. We first examined the data for missing values that are common in survey research and utilized D. A. Bennett’s (2001) recommendation for deleting cases that had 10% of the data missing. For data that were missing at random, these data were replaced using group means for any item that had 15% or less of the cases missing as a way of maintaining the sample size without threatening the validity of the results (George & Mallery, 2010). Descriptive statistics and reliability estimates for all the scales of the sample were calculated to check for errors, statistical assumptions, and violations, and to describe the data distribution. We utilized the guide that a distribution could be approximated to normal if the skewness value was less than or equal to plus or minus two [≤ ±2] (Garson, 2012).

The skewness and kurtosis values for all but the UCLA Loneliness Scale were less than plus or minus two (< ±2), indicating approximately normal distribution (George & Mallery, 2010). It should be noted that the mean, median, and mode for the loneliness measure were similar (47.46), suggesting a fairly normal distribution. Scores were, however, negatively skewed. The data revealed that 15.8% of students scored in the high range for loneliness levels (40–60) and 53.8% were in the very high range (≥ 61). Collinearity statistics were in the acceptable range and met the assumptions for multicollinearity. The means and standard deviation, as well as correlations for the main variables from the SSES, UCLA Loneliness Scale, and Anxiety Attachment and Avoidance Attachment subscales, are presented in Table 1. We used Pearson’s correlation to answer the first research question and regression analyses were used for the other research questions and hypothesis.

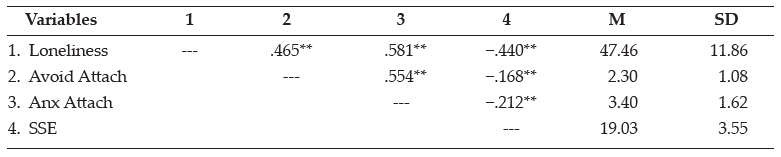

Table 1

Pearson Correlations of Study Variables With Means and Standard Deviation

Note. Avoid Attach = Avoidant Attachment, Anx Attach = Anxious Attachment, SSE = Social Self-Efficacy.

**p < .01.

Results

Correlational Analysis

Pearson correlations were computed to answer the first research question: What is the relationship between social self-efficacy, loneliness, and the types of insecure attachment? The results of the Pearson correlation showed a statistically significant positive correlation between loneliness and avoidant attachment (r = .47, p < .001) and loneliness and anxious attachment (r = .58, p < .001), indicating that participants who had higher levels of avoidant attachment and anxious attachment experienced higher levels of loneliness. The results of Pearson correlation analysis showed a statistically significant negative correlation between loneliness and social self-efficacy (r = −.44, p < .001). The findings indicated that participants who experienced higher levels of social self-efficacy experienced lower levels of loneliness. Additionally, the results of Pearson correlation analysis showed a statistically significant, albeit weak, negative correlation between social self-efficacy and anxious attachment (r = −.21, p < .001), as well as avoidant attachment (r = −.17, p < .001).

Both anxious attachment and avoidant attachment explained 34% and 22% of the variances in loneliness, respectively. Additionally, we found that anxious attachment accounted for 4% of the variance, and avoidant attachment explained 3% of the variance in social self-efficacy. When we analyzed the relationship between loneliness, social self-efficacy, avoidant attachment, and anxious attachment, we found that avoidant attachment was significantly negatively associated with loneliness, while all the other variables showed a significant positive (p < .001) association.

Multiple Regression Analysis

Multiple regression was used to answer the second research question: Do anxious attachment and avoidant attachment predict the levels of social self-efficacy? The results indicated that anxious attachment was a statistically significant predictor of social self-efficacy (F = 40.68, p < .001) with a β of .04 (p < .001), accounting for 5% of the variance in social self-efficacy (see Table 2). These results indicate that among students who participated in this study, higher levels of social self-efficacy were a result of lower levels of both anxious attachment and avoidant attachment styles. Overall, the model explains 5% of the variance of anxious attachment in social self-efficacy (r = .39).

Table 2

Multiple Regression Analysis Predictor of Social Self-Efficacy

Factor R R2* β t p F P

Anxious attachment .21 .05 .04 −6.38 < .001 40.68 < .001

*Adjusted R2 = .04

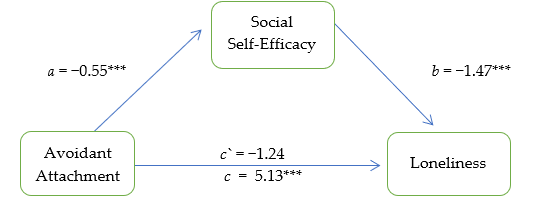

Finally, we examined the third research question and the corresponding hypothesis: How does social self-efficacy mediate the relationship between loneliness and anxious attachment and avoidant attachment styles? In support of our hypothesis that social self-efficacy would mediate the relationship between avoidant attachment and anxious attachment and loneliness, we conducted two regression analyses using Baron and Kenny’s model (1986) for each. In the first model (Figure 1a), in Step 1 the predictor avoidant attachment was regressed on the outcome loneliness. This path provided the coefficient for path c = 5.13 as identified in Figure 1a and was statistically significant {t (861) = 15.42, p = < .001}. In Step 2, the mediator social self-efficacy was regressed against the outcome and provided the path coefficient, denoted a = −.55, with t (862) = −.55, p = < .001. In Step 3, social self-efficacy was regressed on loneliness and the mediator. The significance of the mediation was determined using the Sobel test and was found to be statistically significant at z = −13.54, p = < .001.

Figure 1a

Mediation Path Model for Social Self-Efficacy on Avoidant Attachment on Loneliness

Note. Mediation model testing social self-efficacy as mediator for avoidant attachment and loneliness.

***p < .001

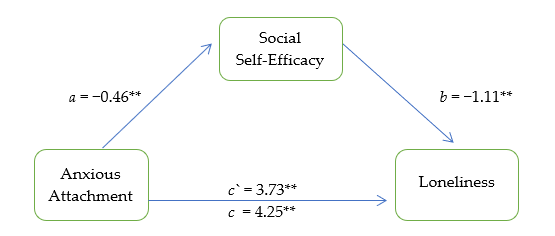

The second path model (Figure 1b) was conducted to ascertain the extent to which social self-efficacy mediated the relationship between anxious attachment and loneliness. Step 1 of the mediation provided the coefficient for path c = 4.25. This was statistically significant {t (861) = 20.945, p = .001}. The mediation path was also statistically significant, signaling partial mediation: c` = 3.73 {t (860) = 19.59, p < .001} with R2 = .442 and adjusted R2 = .441.

Figure 1b

Mediation Path Model for Social Self-Efficacy on Anxious Attachment on Loneliness

Note. Mediation model testing social self-efficacy as mediator for anxious attachment and loneliness.

**p < .001

Discussion

In the current study, we found statistically significant relationships among anxious attachment, avoidant attachment, social self-efficacy, and loneliness. Higher levels of anxious attachment and avoidant attachment were correlated to higher levels of loneliness, which is consistent with prior studies (Benoit & DiTommaso, 2020; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014). Individuals with insecure attachment styles are predisposed to feeling lonely and may not be motivated to seek out others and engage in social activities. Conversely, those with secure attachment styles are more likely to engage with others because of their healthy view of themselves and their interpersonal ability to build and maintain relationships (Akdoğan, 2017; DiTommaso et al., 2015; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). Additionally, the results indicate that social self-efficacy was negatively associated with both anxious attachment and avoidant attachment, as well as loneliness. Students with higher levels of social self-efficacy did not score as having anxious or avoidant attachment styles. Although the weak correlations mean that the findings should be considered with caution, the negative relationship between insecure attachment styles and social self-efficacy reflects the expectations outlined by attachment theory. Specifically, individuals who demonstrate anxious and avoidant attachments will theoretically experience more social interaction challenges, as they may likely possess less social efficacy.

In college, many young adults struggle to adjust to their new social networks and make meaningful relationships. This can be especially challenging for students with an insecure attachment style and can result in them experiencing both emotional and social loneliness as described by DiTommaso et al. (2015) and Yanguas et al. (2018). The current study findings of a negative association between social self-efficacy and insecure attachment support the notion that students with insecure attachment styles may have deficits in their prosocial skills and their ability to initiate and maintain interactions with others, in part explaining their loneliness (Akdoğan, 2017). Negative social self-efficacy stems from internalized negative views about self-worth and competence, as well as a fear of rejection and distrust of others, which can contribute to feelings of loneliness (Akdoğan, 2017; DiTommaso et al., 2015).

In support of the mediation hypothesis, the relationship between avoidant attachment and loneliness was mediated by social self-efficacy, with high social self-efficacy explaining decreased loneliness in those with avoidant attachment. Interestingly, the relationship between anxious attachment and loneliness was only partially mediated by social self-efficacy. Through the lens of attachment theory, this partial mediation makes sense in that individuals with high anxious attachment tend to be fearful of rejection and abandonment. They tend to be overly self-focused and critical; therefore, they may be more likely to perceive themselves as lonely because these worries undermine the quality of their interpersonal relationships (Akdoğan, 2017; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014). These individuals may hold a negative working model of self and may be more likely to perceive themselves as low in social self-efficacy, which could account for the partial mediation.

Conversely, individuals with an avoidant attachment style typically have low expectations of others and tend to push people away. However, the findings indicate that when individuals also have strong social self-efficacy, this seems to mediate the desire for detachment and help them in building relationships with others. Social self-efficacy strengthens one’s interpersonal competency and social skills, thereby enhancing coping strategies and self-regulation during relationship challenges. Thus, our findings support the existing literature that social self-efficacy mediates the relationship between anxious attachment and avoidant attachment on loneliness.

Although this study supports the established relationship of insecure attachment styles and high levels of loneliness, as well as the mediation effect of social self-efficacy on insecure attachment and loneliness, we recognize that existing research has examined the mediating effect after controlling for some psychological distress like depression (Wei et al., 2005). As a result, we reviewed the mediating effects of other constructs that are comparable to social self-efficacy. Our study provides support for mediating effects of feelings of inferiority on insecure attachment and loneliness (Akdoğan, 2017), as well as for mediating effects of social support (Benoit & DiTommaso, 2020). We posit that feelings of inferiority and lack of social support are very similar to lack of social self-efficacy and have significant clinical implications.

Implications for Counseling

Our findings suggest that attachment style greatly influences loneliness and the propensity for how one makes and maintains relationships (Akdoğan, 2017; Helm et al., 2020). For emerging adults who are at Erikson’s stage of intimacy versus isolation, loneliness can be understood as a developmental struggle that some students may need help resolving, particularly if they have avoidant or anxious attachment styles (Erikson, 1980). Counselors should therefore broach the subject of loneliness and assess for loneliness and low self-efficacy with clients as well as examine interpersonal difficulties on campus.

College counselors could utilize the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) Level 1 and Level 2 cross-cutting symptom measures for adults or the widely used Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS; Locke et al., 2011), as well as readily available assessments for depression and anxiety, to collect data on students’ levels of psychological stress. Psychological stress, depression, and anxiety are identified as contributors to and symptoms of loneliness (Cacioppo et al., 2015; Fink, 2014; Moeller & Seehuus, 2019) and can further provide information on social self-efficacy. Additionally, during the normal intake session and risk assessments, counselors should assess for social support, thereby gathering qualitative data on students’ social networks and the quality of their interpersonal relationships.

Because social self-efficacy mediated the relationship between attachment and loneliness, it could prove helpful for counselors to help clients bolster their prosocial skills and interpersonal confidence. This could be done through individual and group counseling interventions based on clients’ assessed needs related to psychological stress and interpersonal difficulties. Furthermore, because counseling promotes a strength-based and wellness philosophy, counselors can work with all students to enhance prosocial skills and interpersonal confidence and resiliency. Bandura (2000) noted that high social self-efficacy requires greater cognitive resourcefulness and flexibility to not only manage the environment but as motivation to achieve a desired goal. For college students, bolstering social self-efficacy might help to build interpersonal confidence, enhance motivation, and give them social capital (Thomas et al., 2020). Our hope is that through these processes, students’ intra- and interpersonal development regarding increased social self-efficacy will translate to academic success, personal success, and a decrease in perceived loneliness.

Because of the interactive nature of group counseling, it may be useful as a therapeutic approach to reducing loneliness in college students. Group counseling may also reveal how those with loneliness approach developing relationships with others in the group. Group work is known to be highly effective and superior to individual therapy, as it provides opportunities for social learning, developing social supports, and improving social networks (Yalom & Leszcz, 2020). For example, personal growth groups (e.g., social support groups or interpersonal process groups) are focused on both the personal and social development of members and can be used as interventions to address insecure attachment and loneliness. Additionally, these groups help members to develop self-awareness and insight while also learning new skills to enhance their interpersonal attractiveness. In short, groups like these have the potential to address members’ interpersonal challenges and disrupt behaviors that impede the building and maintaining of healthy relationships while also enhancing group members’ social self-efficacy. Ultimately, the focus is on relationship building and helping members to feel more connected with each other (Reese, 2011).

Additional ways in which counselors could support students experiencing loneliness is through collaboration with residence life, other social clubs, and groups to help students find connections and learn how to foster and maintain healthy relationships. These approaches support the work of Moeller and Seehuus (2019), reiterating the need to build and enhance college students’ social skills (thereby enhancing social self-efficacy) and facilitating opportunities for greater engagement to reduce loneliness and increase retention (Thomas et al., 2020).

It is noteworthy, but not surprising, that higher anxious and avoidant attachments correlated to higher levels of loneliness in our study. Given this knowledge that students may have negative working models of self and/or others, counselors may need to expand the ways in which they develop rapport and provide supportive spaces for risk-taking where clients may be more willing to explore issues surrounding their insecure attachment. Exploring the impact of the insecure attachment on their sense of self and how it presents as a barrier to initiating and/or maintaining quality social connections could be helpful, in addition to teaching strategies and skills to increase their sense of safety and self-efficacy.

Having conversations about initiating and maintaining meaningful relationships can also allow the counselor to address the risk of rejection and vulnerability inherent in relationships and help the clients develop coping skills to deal with these experiences rather than internalizing negative results. The counseling relationship can serve as a model and as evidence to the students that they have the ability to connect with others. Wei et al. (2005) noted that counselors could help students with high avoidant attachment understand how their reluctance to self-disclose prevents them from developing deeper or emotionally fulfilling relationships. Counselors can help clients with high anxious attachment examine how self-doubts may contribute to their perceptions of loneliness and other mental health challenges and learn strategies to increase self-confidence.

Moreover, the counseling relationship can serve as a model to evaluate the impact of self-doubt and lack of self-disclosure on the relationship and help with insight and self-awareness. As counseling progresses and students begin to address the self-doubt or begin to self-disclose, they will also be able to see how these changes shift the dynamics of the relationship and can lead to a more satisfying relationship. Counselors can incorporate strategies from different modalities, including using cognitive behavioral therapy and narrative therapy to address maladaptive thinking, and can help students explore unique outcomes congruent with their goals. E. D. Bennett et al. (2017) recommended some creative strategies that could be employed (e.g., talk meter, the paper bag story, using music, or modeling interventions using social media models). It is hoped that as students increase their self-awareness and social self-efficacy, they will transfer and integrate these new behaviors in establishing and maintaining relationships outside of the counseling room, thereby strengthening their social networks and decreasing loneliness.

Limitations and Future Research

Though a robust study in terms of the number of participants, this study has several limitations that should be considered. Some of the data collection took place when the college pivoted to online learning and students had to stay home as a result of COVID-19. This time of forced social isolation could have impacted students’ responses. The cross-sectional design of this study is a limitation. Social self-efficacy and perception of loneliness were assessed at one point in time. Social self-efficacy and loneliness are complex constructs that can vary at different time points, so a longitudinal research design is an important next step. Furthermore, a longitudinal design would allow researchers to track changes over time and throughout students’ college experiences, noting changes as a student progresses developmentally.

The self-report nature of the measurements and response bias are limitations that weaken the construct validity of the study. Self-report measures, though used extensively in research, are subject to respondent biases and social desirability (Crowne & Marlowe, 1964), which can limit self-awareness, self-knowledge, and self-report. The poor internal consistency reliability estimates of the SSES in this study is another limitation that might indicate that the SSES failed to capture stability of test scores within our sample. Future researchers may consider using other measures of social self-efficacy.

Although the mediation model provides explanatory effect of social self-efficacy on attachment and loneliness, future studies should examine other related factors such as self-esteem, empathy, or personality traits like Myers-Briggs or the Big Five personality traits. Additionally, the attachment measure was retrospective in nature, and participants were instructed to consider their feelings about close relationships in general rather than on a specific relationship on the Experiences in Close Relationships—Relationship Structures Questionnaire. In retrospect, it might have been more beneficial to have them consider specific relationships at college.

Conclusion

This study further expanded the research on the impact of insecure attachment as a contributor to feelings of loneliness. Further, our study pointed to social self-efficacy as a possible mediator for this relationship. Although attachment styles may be difficult to change, enhancing mediators like social self-efficacy might help individuals with insecure attachment styles to reduce loneliness (Thomas et al., 2020). Helping individuals with insecure attachment styles learn new skills to enhance their interpersonal and intrapersonal skills might enhance their beliefs in others and possibly bolster their self-confidence and competence. In the college setting, enhancing insecure attachment styles may have long-term consequences on reducing feelings of loneliness and may contribute to a sense of belonging and increase retention rates and academic success.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. (1985). Patterns of infant-mother attachments: Antecedents and effects on development. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 61(9), 771–791. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1911899/pdf/bullnyacadmed00065-0005.pdf

Akdoğan, R. (2017). A model proposal on the relationships between loneliness, insecure attachment, and inferiority feelings. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.048

American College Health Association. (2017). American College Health Association – National College Health Assessment II: Fall 2017 Reference Group Executive Summary. https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_FALL_2017_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org./10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (2000). Self-efficacy. In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychology (Vol. 7, pp. 212–213). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/10522-094

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bennett, D. A. (2001). How can I deal with missing data in my study? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(5), 464–469.

Bennett, E. D., Le, K., Lindahl, K., Spencer, W., & Mak, T. W. (2017). Five out of the box techniques for encouraging teenagers to engage in counseling. In Ideas and Research You Can Use: VISTAS 2017, Article 3, 1–17. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/vistas/encouraging-teenagers.pdf

Benoit, A., & DiTommaso, E. (2020). Attachment, loneliness, and online perceived social support. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, 110230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110230

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Separation anxiety and anger. Basic Books.

Bruffaerts, R., Mortier, P., Kiekens, G., Auerbach, R. P., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Green, J. G., Nock, M. K., & Kessler, R. C. (2018). Mental health problems in college freshmen: Prevalence and academic functioning. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.044

Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615570616

Chickering, A. W., & Reisser, L. (1993). Education and identity (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Cigna. (2020). Loneliness and the workplace: 2020 U.S. Report. https://www.cigna.com/static/www-cigna-com/docs/about-us/newsroom/studies-and-reports/combatting-loneliness/cigna-2020-loneliness-report.pdf

Crowne, D. P. and Marlowe, D. (1964). The approval motive: Studies in evaluation dependence. Wiley.

Dahlberg, L. (2021). Loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging & Mental Health, 25(7), 1161–1164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1875195

Diehl, K., Jansen, C., Ishchanova, K., & Hilger-Kolb, J. (2018). Loneliness at universities: Determinants of emotional and social loneliness among students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 1865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091865

DiTommaso, E., Fizell, S. R., & Robinson, B. A. (2015). Chronic loneliness within an attachment framework: Processes and interventions. In A. Sha´ked & A. Rokach (Eds.), Addressing loneliness: Coping prevention and clinical interventions (pp. 241–253). Routledge.

Eisenberg, D., Lipson, S. K., & Heinze, J. (2020). The healthy minds study: Fall 2020 data report. https://healthymindsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/HMS-Fall-2020-National-Data-Report.pdf

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. W. W. Norton.

Fink, J. E. (2014). Flourishing: Exploring predictors of mental health within the college environment. Journal of American College Health, 62(6), 380–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2014.917647

Fraley, R. C., Heffernan, M. E., Vicary, A. M., & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2011). Experiences in Close Relationships—Relationship Structures Questionnaire. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t08412-000

Garson, G. (2012). Testing statistical assumptions. Statistical Associates Publishing.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple study guide and reference, 17.0 update (10th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Helm, P. J., Jimenez, T., Bultmann, M., Lifshin, U., Greenberg, J., & Arndt, J. (2020). Existential isolation, loneliness, and attachment in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 159, 109890.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109890

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2020, June 22). The double pandemic of social isolation and COVID-19: Cross-sector policy must address both. Health Affairs Forefront. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20200609.53823

Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2023). Alpha, omega, and H internal consistency reliability estimates: Reviewing these options and when to use them. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 14(1), 77–88.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2021.1940118

Kim, Y., Kim, B., Hwang, H.-S., & Lee, D. (2020). Social media and life satisfaction among college students: A moderated mediation model of SNS communication network heterogeneity and social self-efficacy on satisfaction with campus life. The Social Science Journal, 57(1), 85–100.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2018.12.001

Klausli, J. F., & Caudill, C. (2021). Discerning student depression: Religious coping and social support mediating attachment. Counseling and Values, 66(2), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/cvj.12156

Locke, B. D., Buzolitz, J. S., Lei, P.-W., Boswell, J. F., McAleavey, A. A., Sevig, T. D., Dowis, J. D., & Hayes, J. A. (2011). Development of the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021282

Mallinckrodt, B., & Wei, M. (2005). Attachment, social competencies, social support, and psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(3), 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.358

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2014). An attachment perspective on loneliness. In R. J. Coplan & J. C. Bowker (Eds), The handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (pp. 34–50). Wiley.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2019). Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.006

Moeller, R. W., & Seehuus, M. (2019). Loneliness as a mediator for college students’ social skills and experiences of depression and anxiety. Journal of Adolescence, 73(1), 1–13.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.03.006

Murthy, V. (2020, March 23). Former surgeon general Vivek Murthy: Loneliness is a public health crisis [Interview]. WBUR On Point. https://www.wbur.org/onpoint/2020/03/23/vivek-murthy-loneliness

Mushtaq, R., Shoib, S., Shah, T., & Mushtaq, S. (2014). Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 8(9), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828

Pan American Health Organization. (2020, January 30). WHO declares public health emergency on novel coronavirus [Press release]. https://www.paho.org/en/news/30-1-2020-who-declares-public-health-emergency-novel-coronavirus

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In R. Gilmour & S. Duck (Eds.), Personal Relationships: 3. Relationships in Disorder (pp. 31–56). Academic Press.

Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., Maes, M., & Verhagen, M. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 250–264.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615568999

Reese, M. K. (2011). Interpersonal process groups in college and university settings. In T. Fitch & J. L. Marshall (Eds.), Group work and outreach plans for college counselors (pp. 87–92). American Counseling Association.

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

Sharf, R. S. (2012). Theories of psychotherapy and counseling: Concepts and cases (5th ed.). Cengage.

Sherer, M., Maddux, J. E., Mercandante, B., Prentice-Dunn, S., Jacobs, B., & Rogers, R. W. (1982). The Self-Efficacy Scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports, 51(2), 663–671.

https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.663

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Pearson.

Tavakoli, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

Thomas, L., Orme, E., & Kerrigan, F. (2020). Student loneliness: The role of social media through life transitions. Computers & Education, 146, 103754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103754

Thurber, C. A., & Walton, E. A. (2012). Homesickness and adjustment in university students. Journal of American College Health, 60(5), 415–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2012.673520

Varghese, M. E., & Pistole, M. C. (2017). College student cyberbullying: Self-esteem, depression, loneliness, and attachment. Journal of College Counseling, 20(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocc.12055

Wei, M., Russell, D. W., & Zakalik, R. A. (2005). Adult attachment, social self-efficacy, self-disclosure, loneliness, and subsequent depression for freshman college students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), 602–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.602

Yalom, I. D., & Leszcz, M. (2020). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (6th ed.). Basic Books.

Yanguas, J., Pinazo-Henandis, S., & Tarazona-Santabalbina, F. J. (2018). The complexity of loneliness. Acta Biomedica, 89(2), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v89i2.7404

Zhu, W., Wang, C. D., & Chong, C. C. (2016). Adult attachment, perceived social support, cultural orientation, and depressive symptoms: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(6),

645–655. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000161

Claudette Brown-Smythe, PhD, NCC, ACS, LMHC, CRC, is an assistant professor at SUNY Brockport. Shirin Sultana, PhD, MSS, MSSW, is an assistant professor at SUNY Brockport. Correspondence may be addressed to Claudette Brown-Smythe, 350 New Campus Drive, Brockport, NY 14420, cbrownsm@brockport.edu.