Oct 15, 2014 | Article, Volume 3 - Issue 1

Angie D. Wilson, Pennie Johnson

The addictions field continues to grow and is expanding beyond the area of substance abuse and substance dependence. Process addictions are now an integral aspect of addictions treatment, diagnosis, and assessment. There is a gap in the literature related to process addictions which impacts counselors and clients due to lack of literature and knowledge on this new area. It also is hypothesized that there is a gap in continued education for incorporating treatment and assessment measure into clinical practice. This initial study was conducted to initiate an understanding of levels of knowledge counselors have in diagnosing, assessing and treating clients suffering with process addictions, indicators of where and how they learned about process addictions, and how they integrate their level of the treatment of process addictions into clinical practice. The authors provide a brief overview of process addictions, a summary of original research, implications of this study, discussion, and recommendations for future research.

Keywords: process addictions, counseling, addiction disorders, compulsive behaviors, behavioral addictions

It is important for counselors and mental health professionals to stay current with information impacting their profession. Staying abreast of new ideas and new information can assist in providing successful and holistic treatment for clients (ACA, 2005). Specifically, the field of addictions has had many transformations over the last few decades. One of the most recent issues impacting the addictions area in counseling is process addictions (PAs) (Grant, Potenza, Weinstein, & Gorelick, 2010; Holden, 2001; Martin & Petry, 2005). For many years, mental health professionals have treated clients with systematic behaviors mimicking the disease of addiction, but many find they haven’t received adequate training in this area to be competent. The terminology of PA sweeps a wide variety of behavioral addictions or compulsive behaviors. PA is defined as any compulsive-like behavior that interferes with normal living and causes significant negative consequences in the person’s family, work and social life. Gambling, Internet addiction, sex addiction, exercise addiction and eating addictions are among those identified as PA (Sussman, Lisha, & Griffiths, 2011).

The neurological changes in the brains of people who engaged in gambling, binge eating, and compulsive sex were similar to those brains of persons who abused substances such as alcohol and marijuana. Treatment observations and prevalence data, coupled with a growing body of literature, suggest the existence of PAs (Smith & Seymour, 2004), also called compulsive behaviors (Inaba & Cohen, 2011) and behavioral addictions (Grant et al., 2010). PAs may be new to some; however, PAs represent neither a new phenomenon nor new disorders. In actuality, PAs have been an area of concern in the addictions field for many years (Grant et al., 2010; Holden, 2001; Martin & Petry, 2005).

There is little evidence that this evolving research on PAs is being translated to those providing services to clients. Due to the gap in the literature related to PAs and the knowledge of counselors, students, and counselor educators related to PA, the International Association for Addictions and Offender Counseling (IAAOC) Process Addictions Committee (a division and committee of the American Counseling Association) conducted a survey of students, post-graduate counselors, and counselor educators with the purpose of understanding the deficiencies clinicians are struggling with in understanding process addiction. The purpose of this article is to provide the results of a survey, which indicated the percentage of post-graduate counselors/clinicians in the study and their understanding of PAs. The information in this manuscript will specifically address the knowledge of counselors who are actively engaged in providing treatment services in community settings.

Review of Relevant Literature

The most recent definition of addiction was the product of research studies, which took place over four years and included over 80 experts from across the country. These research studies were spearheaded by The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). According to ASAM (2012) an addiction is not merely a behavioral problem involving the consumption or intake of substances, gambling, or sex; an addiction is a chronic brain disorder. Another definition of addiction is the behavior that occurs with continued substance use or involvement in a PA regardless of the negative impact it has on the participant’s life (Shallcross, 2011). What follows is a brief overview of several PAs that have been researched and are referenced in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (4th ed., text rev.; DSM–IV–TR; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000), and the new DSM-5 (APA, 2012a).

The diagnostic criteria of the various PAs are similar to those of substance addictions. Due to these negative consequences, PAs continue to disrupt the lives of significant proportions of the U.S. adult population (Sussman et al., 2011). Based upon a literature review of 83 studies, Sussman et al. (2011) estimated prevalence rates for gambling addiction (2%), Internet addiction (2%), sex addiction (3%), exercise addiction (2%), and eating addiction (2%) among the general American population. The growing concern regarding PAs may be due to the increased co-morbidity with mental health concerns and substance addictions (Sussman et al., 2011). Substance abuse co-morbidity rates for gambling addiction were approximated at 20-30%, Internet addiction 10%, love and sex addictions 40%, exercise addiction 15%, and eating addiction 25% (Sussman et al., 2011). According to Carnes (2009) most addicts have more than one addiction, sustained recovery is more successful when all addictions present are addressed in counseling, and addictions do not merely coexist, but actually interact with each other.

The term disorder is often used interchangeably with the term addiction. For example, one of the most widely known and recognizable PA is gambling disorder, which is also called gambling addiction and pathological gambling (Ashley & Boehlke, 2012; Jamieson, Mazmanian, Penney, Black, & Nguyen, 2011). It is believed that gambling disorder will be categorized under Addiction and Related Disorders in the DSM-5 (APA, 2012b), as the diagnosing criteria closely resemble substance use disorder. In order for one to be diagnosed with gambling disorder, the gambling behavior must disrupt the personal or work life of the affected person and cannot be related to a manic episode (APA, 2000). According to Crozier and Sligar (2010), some indicators that one’s social gambling is shifting into a PA include lifestyle changes to accommodate gambling-related activities, extreme mood fluctuations related to gambling, justifications for continued gambling, perceptible excitement when discussing gambling, as well as financial indicators such as hiding debt and frequently borrowing money.

Food addiction, eating addiction, and compulsive eating also are referenced as Binge Eating Disorder (BED) and is another of the PAs that may be revised in the DSM-5, from the category of Other Conditions (APA, 2000) to Feeding and Eating Disorders (APA, 2012c; Wonderlich, Gordon, Mitchell, Crosby, & Engel, 2009). Frequent episodes of uninhibited food consumption beyond the point of fullness, without being followed by purging behaviors (e.g., vomiting or the use of laxatives), are characteristics of BED. According to Karim and Chaudhri (2012), individuals with BED will typically eat without feeling hungry, spend excessive amounts of time thinking about and obtaining food, and may attempt to hide their eating from others. Although some people with BED may be obese or overweight, BED is distinct from other eating disorders, as individuals with this condition are mentally and emotionally different from individuals who are obese or overweight (Wonderlich et al., 2009).

The term exercise addiction was first introduced by Glasser (1976), who studied long-distance runners and found out that most of them had an obsessive-compulsive disorder. Exercise addiction, or sports addiction, is a phenomenon typically found in athletes (McNamara & McCabe, 2012). Exercise addiction has been a growing concern for the counseling field for a number of years (Parastatidou, Doganis, Theodorakis, & Vlachopoulos, 2012). Exercise dependence, obligatory exercise, compulsive exercise, and excessive exercise are other names for exercise addiction or sports addiction (Parastatidou et al., 2012). Training interferes with daily life and is diagnosed with criteria similar to those of substance abuse disorders as well as other PAs.

Another widely recognized addiction is Internet addiction, also called Internet Use Disorder (APA, 2012d), which is not found in the DSM-IV, but is being considered for inclusion in the DSM-5 (APA, 2012d; Ko, Yen, Yen, Chen, & Chen, 2012). The criteria used to define this addiction closely match the criteria for substance dependence. For example, the use of the Internet becomes a preoccupation or begins to monopolize the individual’s time, there is an increased need to obtain positive feelings, social relationships are negatively affected by Internet usage, and a person returns to maladaptive Internet use after a period of abstinence (Smahel, Brown, & Blinka, 2012).

According to Karim and Chaudhri (2012), a disproportionate amount of time spent on planning for and participating in sexual activity, participating in sexual activity to alter one’s mood or as a way to handle stress, inability to control sexual compulsions and sexual fantasies, and engaging in unsafe sexual activity can be called hypersexual disorder (APA, 2012e). Hypersexual disorder (APA, 2012e) also is called sex addiction and compulsive sex. Shifts in emotions and values; compulsive masturbation; inappropriate jokes, personal boundaries, and touching; boasting about sexual conquests; and unplanned sexual encounters are indicators of compulsive sex (Crozier & Sligar, 2010).

Training of Counselors on Process Addictions

The US Department of Health and Human Services, TAP 21 (HHS, 2006) recommends that all counselors should be competent in “understanding of addiction, treatment knowledge, application to practice, and professional readiness” (p. 5). Although this is recommended, it is often difficult for counselors to locate educational training and research related to PAs due to the limited available information. Although licensed counselors graduate from master’s- and doctorate-level universities in counseling programs, researchers (Crozier & Agius, 2012) indicate many counselor educators are not adequately equipped with recent knowledge regarding PAs and, therefore, academic organizations are not properly educating future counselors in this area. Of course, some information regarding addictions is infused into the coursework in most graduate programs, but counselors with specific interest in addictions must seek additional training and education through outside sources such as continuing education and specified certification programs. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of licensed counselors to stay abreast with clinical training and new areas related to treatment, assessment and diagnosis of maladaptive disorders. However, there are concerns regarding the accessibility of training and professional growth seminars on PAs, as many counselor educators who are the primary researchers in the counseling field are not aware of this growing area of PAs (Crozier & Agius, 2012), and many counseling students are not being taught about PAs in their counselor training programs (Nelson, Wilson, & Holman, n.d.). This creates a problem for the counseling profession in that there is continued need for training and research in this area. “The development of effective practice in addiction counseling depends on the presence of attitudes reflecting openness to alternative approaches, appreciation of diversity, and willingness to change” (HHS, 2005, p.5).

Methodology

This pilot study has helped provide structure for a national study being conducted by the IAAOC. An online survey was constructed by members of the IAAOC Committee on PAs who are all active professionals in the field. They followed methodological research guidelines (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2009) to design a valid, mixed-methods design (Onwuegbuzie & Johnson, 2006) comprised of open-ended and closed-ended research questions. Upon approval from the Institutional Review Boards, counselors in NC and TX received an email requesting their participation in this initial study. The survey, statement of anonymity and confidentiality, as well as the informed consent was posted in Zip Survey and participants were prompted to review this information before proceeding with the study. The data also was collected and analyzed within the Zip Survey program. Potential participants later received two separate reminder emails prior to the survey’s closing date asking them to participate in the study.

Participants

The participants were solicited by the investigators through professional listservs, websites of professional organizations, personal communication with counseling professionals and word of mouth. Participants were asked to address the online survey, read the informed consent and begin the survey. Calculating the response rate for the survey was not possible because it was not possible to determine how many counselors actually received the survey. It also is important to note that counselors may have chosen to describe themselves as counselor educators, if they were both counselors and counselor educators. In this case, those counselors’ responses would have been included in the data for counselor educators and not counselors.

The total sample for our study included 37 counselors who were post-graduate clinicians/counselors. The counselors who participated in the study included the following: 59% with a master’s degree in community counseling/mental health counseling, 8 % with a master’s degree in a counseling-related field with a certificate in addiction, 3% with an educational specialist degree in a counseling-related field, and 22% with a doctorate in a counseling-related field. Fifty-eight percent graduated from CACREP-accredited programs with 2009 standards and 3% from CACREP-accredited programs with 2013 standards. Thirty percent graduated from a regionally accredited program that was not CACREP-accredited, and 9% graduated from an academic setting that was not regionally accredited or CACREP-accredited. It must be noted that five participants omitted the question regarding accreditation of their most recent counselor education program.

Instrument

A survey was developed to obtain counselors’ opinions and experiences with assessing, diagnosing and treating PAs. The survey questions were based on a thorough review of the literature and were relevant to the participants’ knowledge of PAs and their experiences as clinicians. The survey questions were developed in accordance to current survey methodological research guidelines (Dillman et al., 2009), and then the questions were sent to all members of the IAAOC Process Addictions Committee to asses for content validity. Finally, they were revised based on the members’ feedback. The survey included both closed- and open-ended questions and was designed to be completed in 10–15 minutes.

A grand tour question is a type of descriptive inquiry that provides information on an experience or phenomenon. According to Spradley (1979), using grand tour questions constitutes an emergent quality of the interview process that results in subsequent questions. One grand tour question was used: “What are your thoughts or feelings about working with clients who present with PA?” In addition to the grand tour question, descriptive survey questions and open-ended text boxes were provided for participants to elaborate on their responses.

Data Collection and Analysis

Zip Survey was used to post the surveys and collect responses as well as to analyze the demographic and quantitative data. Participants received an email with a link to the survey requesting their participation. Upon opening the link, participants read the informed consent and agreed that they understood the nature of the study by continuing with the survey questions. Participants were assured in the informed consent that their responses were anonymous and confidential.

The survey program collected the responses and aggregated them into charts and Excel files. The quantitative results are descriptive data and are reported as such in the results section. Participants also had the opportunity to utilize text boxes within the survey in order to give a rich description of their experiences. The qualitative data obtained from participants who shared their ideas and experiences through the text boxes embedded in the survey also were utilized as data in this study. According to Moustakas (1994), data must be in written form in order to organize qualitative research; the qualitative data was in written form for this study as the Zip Survey collected the written words of participants via typed text. Organizing the text responses and following Moustakas’s (1994) seven steps adapted from Van Kaam’s (1959, 1966) interview analysis process were key steps during the data organization phase of the study. Additionally, both quantitative and qualitative data were compared with one another to achieve triangulation (Onwuegbuzie & Johnson, 2006).

Results

The total sample for this study included 37 counselors. They provided information on their training and clinical experiences related directly to the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of clients with PAs. Specifically, the participants responded to questions regarding their comfort levels working with PAs and assessing, diagnosing, and treating nine different forms of PAs. Approximately 89% of the respondents indicated that learning about PA was very important for clinicians, while 6% noted that it was important and 6% indicated learning about PA was a neutral issue. Less than 13% of the participants understood that PA included compulsive behaviors such as eating disorders, exercise, Internet, gaming, gambling, relationships, sex, work addiction and compulsive spending. Sixty-four percent of the counselors surveyed acknowledged they treated clients with PAs, but where lacking the training to assess and screen for addictions.

Regarding comfort level in assessing, diagnosing and treating PAs, 25% of respondents reported feeling very comfortable, 42% reported feeling comfortable, 22% reported feeling ambivalent, 6% reported not feeling comfortable, and 6% selected not applicable. Counselors reported being trained to assess, diagnose and treat eating disorders more than the other PAs listed on the survey. Eating disorders, relationships and sex were the three PAs that counselors reported having the most learning experiences. Approximately 24% of the respondents had been trained to assess and screen for eating disorders. However, 36% of the participants were trained to diagnose eating disorders and only 19% had been trained to treat eating disorders. From the responses of the participants in this pilot study, it can be gathered that counselors are treating PAs without adequate training and continued education.

On average, a third of the participants had been trained to diagnose eating disorders, but most had little to no training in diagnosing the various other forms of PA. Yet, they knowingly are treating clients with addictions. With this admittance, the 89% of counselors who participated in the survey identified the importance of training counselors to assess, screen, diagnose and treat PAs, and 94% expressed interest in taking a process addictions seminar or course. Regarding theoretical orientation, 69% of the participants identified as cognitive behavioral, 8 % as humanistic, and 6% as psychodynamic.

Participants also were given the opportunity to provide qualitative responses to some questions. Overall, participants shared that they believed learning about PAs was important. Many were not prepared to provide treatment for clients with PAs, and many were not trained to adequately provide therapeutic services for clients with PAs. One participant stated, “I have never considered the term process addiction, and I could easily see myself changing that answer upon further thought and education. I find the ignorance in the counseling world regarding process addictions terrifying.” Another wrote, “I think graduate programs are very deficient in chemical and behavioral education/training. I was never taught anything in graduate school about addictions.” Overall, the majority of participants expressed their opinions about the importance of continued education and knowledge of PAs, shared that they had not been educated on PAs, or shared that their education on addictions was mainly focused on substance abuse treatment.

Discussion

“Counselors practice only within the boundaries of their competence, based on their education, training, supervised experience, state and national professional credentials, and appropriate professional experience” (ACA, 2005, p. 9) is an integral aspect of the counseling profession. By adhering to this section of the ACA Code of Ethics (ACA, 2005), all licensed professionals vow to accept responsibility to ‘do no harm’ to the physical, mental and emotional well-being of self, clients, and associates. Although most counselors intend to do no harm and strictly follow ethical guidelines, it is important to understand that by not providing comprehensive treatment for all addictive or problematic behaviors, some counselors may be unintentionally harming clients. Moreover, when the counselors’ only focus for treatment is the first behavior presented by the client, there is a danger of overlooking co-addictions. “Once the initial neural pathway is laid down, other addictions become overlays using some of the same circuitry” (Carnes, 2009, p.13). These co-addictions are often referred to as addiction interactions. Unfortunately, many factors of co-addictions can be found in PAs, which are often compounded by nature such as eating, sex and exercise, making the need or craving acceptable in society.

PA can be defined as any compulsive-like behavior that interferes with normal living and causes significant negative consequences, and the physiological responses in the brain are similar to chemical dependency (Grant, 2008). As aforementioned, the difficulties in recognizing PAs lie within the realm of society. For example, many of the associated behaviors are socially accepted, such as sex, spending, eating and work, all of which are an intricate part of our hierarchy of basic human needs. When assessing and diagnosing addictions, the focus is typically drug and alcohol dependency behaviors; however, PAs may mimic some of the same characteristics. Such characteristics include loss of control, compulsive behaviors, efforts to stop the compulsive behavior, loss of time, preoccupation, inability to fulfill obligations, continuation of the behavior despite the consequences, withdrawal, escalation and losses (Carnes, 2010). Other potential problems are often experienced by clients who have not been treated for all addictions and problem behaviors. Some of these include personal neglect, compulsive Internet use, isolation and avoidance of people, lost productivity, depression, dissociative states, marital and relationships problems, increased sexual risk behaviors, gambling, and academic failure.

Recommendations and Future Research

The addictions field is emerging with various types of disorders, and counselors are finding themselves to be overwhelmed and incompetent in handling the increasing demands for diagnosis, assessment and treatment of addictions in general and specifically PAs. Although counselors are expected to obtain continuing education to keep abreast of the evolution of counseling in the field, clinicians who participated in this study indicated that they were overall ill-prepared to work with clients who are living with PAs. First, it is recommended that counselor education programs implement courses that include properly assessing, diagnosing and treating PAs.

Second, it is important to reiterate that counselors make a professional vow to practice within their scope and to make referrals for services they are not capable of providing. Based on the information provided by participants in this pilot study, counselors who have no training with treating PAs are not making referrals for their clients, and are making the conscious efforts to continue working with clients who are living with PAs. It is recommended that workshops and continuing education programs specifically focused on PAs be provided for counselors who are active in the field. Staying current with the profession is of utmost importance when working in a field that changes based on available information. Moreover, it is an ethical violation to provide treatment services in an area that is beyond one’s scope of competency (ACA, 2005).

Finally, this pilot study will be replicated on a national level, obtaining further information about counselors’ knowledge and comfort level with assessing, diagnosing and treating PAs. The IAAOC is interested in further researching the knowledge of counselor educators and graduate students in counselor education programs regarding their knowledge of PAs in order to meet the needs of this population and strengthen the knowledge base of PAs within the counseling profession.

References

American Counseling Association. (2005). ACA code of ethics. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/resources/codeofethics/TP/ home/ct2.aspx.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). doi:10.1176/appi. books.9780890423349.

American Psychiatric Association. (2012a). DSM-5 development. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/Pages/Default.aspx.

American Psychiatric Association. (2012b). R 37 gambling disorder. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/proposedrevision/pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=210.

American Psychiatric Association. (2012c). DSM-5 development: K 05 binge eating disorder. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/proposedrevision/pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=372#.

American Psychiatric Association. (2012d). DSM-5 development: Internet use disorder. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/proposedrevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=573.

American Psychiatric Association. (2012e). Hypersexual disorder. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/proposedrevision/pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=415

American Society of Addiction Medicine. (2012). Addiction defined. Retrieved from http://www.asam.org/for-the-public/definition-of-addiction.

Ashley, L. L., & Boehlke, K. K. (2012). Pathological gambling: A general overview. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 44(1), 2737. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.662078.

Carnes, P. (2010). Facing the shadow (2nd ed.). Carefree, AZ: Gentle Path Press.

Carnes, P. (2009). Recovery zone, volume 1: Making changes that last: The internal tasks. Carefree, AZ: Gentle Path Press.

Crozier, M., & Agius, M. (2012). Counselor educators & process addictions: How we know what we know. NC Perspectives, 7, 32–40.

Crozier, M., & Sligar, S. (2010). Behavioral addictions screening during the vocational evaluation process. Vocational Evaluation & Work Adjustment Association Journal, 37, 45–57.

Dillman, D., Smyth, J., & Christian, L. (2009). Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Glasser, W. (1976). Positive addiction. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Grant, J. (2008). Impulse control disorders: A clinician’s guide to understanding and treating behavioral addictions. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Grant, J. E., Potenza, M. N., Weinstein, A., & Gorelick, D. A. (2010). Introduction to behavioral addictions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 233–241. doi:10.3109/00952990.2010.491884

Holden C. (2001). ‘Behavioral’ addictions: Do they exist? Science, 294, 980–982.

Inaba, D., & Cohen, W. (2011). Uppers, downers, all arounders: Physical and mental effects of psychoactive drugs (7th ed.). Medford, OR: CNS Productions.

Jamieson, J., Mazmanian, D., Penney, A., Black, N., & Nguyen, A. (2011). When problem gambling is the primary reason for seeking addiction treatment. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 9(2), 180–192. doi:10.1007/s11469-009-9268-3

Karim, R., & Chaudhri, P. (2012). Behavioral addictions: An overview. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 44(1), 5–17. doi:10.1080/027910722012.662859

Ko, C., Yen, J., Yen, C., Chen, C., & Chen, C. (2012). The association between Internet addiction and psychiatric disorder: A review of the literature. European Psychiatry, 27(1), 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.04.011

Martin, P. R., & Petry, N. M. (2005). Are non-substance-related addictions really addictions? The American Journal on Addictions, 14(1), 1–7. doi: 10.1080/10550490590899808

McNamara, J., & McCabe, M. P. (2012). Striving for success or addiction? Exercise dependence among elite Australian athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30, 755–766. doi:10.1080/02640414.2012.667879

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nelson, J., Wilson, A., & Holman, L. (n.d.). Training students in counselor education programs on process addictions. Unpublished manuscript.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Johnson, B. (2006). The validity issue in mixed research. Research in Schools, 13, 48–63.

Parastatidou, I. S., Doganis, G., Theodorakis, Y., & Vlachopoulos, S. P. (2012). Addicted to exercise: Psychometric properties of the Exercise Dependence Scale-Revised in a sample of Greek exercise participants. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(1), 3–10. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000084

Shallcross, L. (June, 2011). Don’t turn away. Counseling Today, 53(12), 30–38.

Smahel, D., Brown, B., & Blinka, L. (2012). Associations between online friendship and Internet addiction among adolescents and emerging adults. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 381–388. doi:10.1037/a0027025

Smith, D., & Seymour, R. (2004). The nature of addiction. In R. Coombs (Ed.), Handbook of addictive disorders: A practical guide to diagnosis and treatment (pp. 3–30). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Spradley, J. P. (1979). The Ethnographic Interview. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Sussman, S., Lisha, N., & Griffiths, M. (2011). Prevalence of the addictions: A problem of the majority or the minority? Evaluation & the Health Professions, 34(1), 3–56. doi: 10.1177/0163278710380124

US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2006). Addiction counseling competencies: The knowledge, skills, and attitudes of professional practice, TAP 21, Technical Assistance Publication Series [DHHS Publication No. SMA 06-4171]. Retrieved from http://www.kap.samhsa.gov/ products/manuals/pdfs/tap21_08r.pdf.

Van Kaam, A. (1959). Phenomenal analysis. Exemplified by a study of the experience of “really feeling understood.” Journal of Individual Psychology, 15, 66-72.

Van Kaam, A. (1966). Existential foundations of psychology. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Wonderlich, S. A., Gordon, K. H., Mitchell, J. E., Crosby, R. D., & Engel, S. G. (2009). The validity and clinical utility of binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42(8), 687–705. doi:10.1002/eat.20719

Angie D. Wilson is an Assistant Professor at Texas A&M University-Commerce. Pennie Johnson is the Vice President for Project Management at the International Institute for Trauma and Addiction Professionals (IITAP) and a doctoral student at Walden University in the Department of Counselor Education and Supervision. Correspondence can be addressed to Angie D. Wilson, 1700 Hwy 24, Department of Psychology, Counseling, and Special Education (Binnion Hall), Texas A&M University-Commerce, Commerce, TX 75429, angie.wilson@tamuc.edu.

Oct 15, 2014 | Article, Volume 3 - Issue 1

Ryan F. Reese, J. Scott Young, Gerald A. Hutchinson

To date, few scholars in counselor education have attended to the processes and impacts of introducing business-related concepts within counseling curricula. The authors describe the development, implementation and evaluation of a graduate-level course titled Entrepreneurship in Clinical Settings wherein students were tasked with producing a business plan for their ideal clinical practice. Implications and recommendations are explored.

Keywords: entrepreneurship, private practice, problem-based learning, clinical settings, counselor education

Recent attention in mainstream professional counseling has brought to light the complexities of establishing and maintaining a successful clinical practice (Shallcross, 2011). Developing and sustaining a caseload through a referral base, deciding whether to buy or rent office space, and identifying a marketable niche are just a few of the many challenges practitioners face in establishing a counseling practice. Despite the complex nature of counseling practice that requires a competent understanding of foundational business concepts, limited literature exists within counselor education to address the importance of preparing counselors to succeed in private practice (Reynolds, 2010). A search for business failure rates for 2012 revealed that only 47.6% of services business, of which a counseling practice is one type, survive for five years (Shane, 2012), meaning that less that one of two counselors who begins a clinical practice will be in business five years hence. Relatedly, researchers within the field have noted that mental health practitioners have been economically naive and must expand conceptualizations of potential applications of psychological treatment, stressing the need for counselors to become more entrepreneurial (Cummings, Cummings, & O’Donohue, 2009). The development of scholarly writing around business-related concepts in counselor education might help counselor educators better prepare counselors to develop competencies related to successfully developing and running a clinical practice. Although there is a dearth of such writing at present in counselor education literature, scholars within related professions (e.g., social work; Green, Baskind, Mustian, Reed, & Taylor, 2007) have highlighted the lack of preparation that students in their fields receive in developing and managing a clinical practice and are taking steps to increase training in business-related practices. In a survey study (N=261) conducted by Green and colleagues with social work graduate stakeholders (e.g., graduate students, graduate-level deans, private and agency-level social workers), nearly 66% of graduate students intended to enter private practice, yet none of the graduate schools surveyed taught content associated with the establishment and management of a clinical practice. A similar lack of literature regarding entrepreneurship in counselor education settings would suggest that a quandary exists in programs preparing counselors for professional private practice enterprises.

Current educational standards within programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) do not require that students complete coursework in the business-related aspects of professional counseling. However, counselor educators who would like to provide students with practice management training cite the CACREP (2009) standards to support the infusion of business-related concepts into current courses or even in the development of a new graduate course. For example, the standards state that upon graduation from a CACREP-accredited program, a student pursuing a clinical mental health counseling track “understands the roles and functions of clinical mental health counselors in various practice settings” (CACREP, 2009, Code A.3; p. 30). That is, students will understand how to function in clinical settings, which includes private practice. In addition, the standards state that a student “understands the management of mental health services and programs, including areas such as administration, finance, and accountability” for their roles in counseling settings (CACREP, 2009, Code A.8; p. 30). Thus, the standards encourage students to gain an understanding of the technical aspects of professional counseling that can include an understanding of developing and maintaining a successful counseling practice. Offering students opportunities to gain practice management skills and competencies within counselor education programs might better prepare them to one day develop their own counseling practices.

Without an exhaustive survey, it is not known how many counselor education programs cover any of the business-related skills of clinical practice. What is certain is that in the United States nearly 20% of all small businesses do not survive past their first year and only 44% of small businesses survive to see their four-year anniversary (Knaup & Piazza, 2007). As of August 1, 2011, of the 42,926 American Counseling Association (ACA) members reporting their work settings, 10.45% described their full-time work setting as private practice and 4.1% described their part-time work setting as private practice. In sum, 14.5% of current ACA members who reported their work setting described themselves as working in private practice (C. Neiman, personal communication, August 15, 2011). Given the high failure rates for small businesses in the service sector and the fact that nearly one in seven counselors describe themselves as conducting private practice, counselor education programs should consider placing a higher emphasis on facilitating the development of knowledge and skills associated with the successful creation and management of a clinical practice.

To address this lack of training, the authors developed and implemented a graduate-level elective course titled Entrepreneurship in Clinical Settings open to both masters and doctoral-level students enrolled in graduate-level helping profession programs (e.g., counselor education, clinical psychology, social work, nursing, kinesiology, etc.) at a university located in the southeast United States. Those actually enrolled in the course included masters and doctoral-level students from counselor education. The course was advertised as an opportunity to obtain the knowledge needed to develop and run a successful private practice. The purpose of developing the course was to advance students’ knowledge and related skills in formulating an individualized business plan for establishing a clinical practice and thereby preparing them to successfully manage a small business.

The purpose of this article is to provide counselor educators and other interested readers with the information needed to adapt or develop a similar course or workshop that fits the needs of their counselor preparation programs. Subsequently, the development, implementation, evaluation and implications of a clinical entrepreneurship course specifically designed to assist students in the acquisition of the knowledge and skills necessary to develop a counseling practice in their desired setting are described.

Entrepreneurial Pedagogy

The semester-long course was co-taught by a counselor educator (second author) and a leadership consultant working in private practice (third author). The course was developed from a pedagogical structure grounded in problem-based learning (PBL) (Albanese & Mitchell, 1993). PBL typically involves the presentation of a set of carefully constructed problems to a small group of students consisting of observable phenomena or events that need explanation. The task of students is to discuss these problems and produce explanations for the phenomena (Norman & Schmidt, 1992). PBL has been implemented in a variety of educational contexts including medical training (Albanese & Mitchell, 1993), teacher preparation (Brocato, 2009) and counselor education (Stewart, 1998). With PBL, the instructor places the ownership of learning directly into the hands of students by posing a problem they must solve prior to the learning of concepts that will assist them in solving the problem (Bouhuijs & Gijselaers, 1993). Subsequently, PBL relies not on didactic instruction but on the provision of resources to aid students in developing practical knowledge needed to solve the problem at hand (Savery, 2006). Within a PBL teaching framework, the instructor is viewed as an expert resource that facilitates critical thinking by asking guided questions and providing feedback as students attempt to solve the problem at hand rather than lecturing about predetermined material (Stewart, 1998). For this course, the instructor (second author) who was a counselor educator also had over 15 years of experience as a part-time private practitioner providing counseling to children, adolescents and adults as well as couple and family counseling. He had successfully established counseling practices in two states treating a wide array of clinical issues, was knowledgeable about billing, insurance panels, marketing, accounting and related issues, had completed training in PBL pedagogy, and had extensive training in business (e.g., a B.A. in business administration). The co-instructor (third author) had obtained a Ph.D. in counselor education and supervision and spent over 15 years as a leadership development consultant to persons in positions of leadership in private industry. He had owned his own successful consulting firm for 12 years, possessing extensive training in executive coaching, consulting and leadership enhancement.

For the Entrepreneurship in Clinical Settings course, students were charged with formulating the specific components of a business plan (see Table 1), which required them to creatively align their own interests with the plan elements while accounting for practical factors that would facilitate or hinder the success of their plan. To meet this goal, each student developed a series of proposals to address the assigned problem, and then worked in small groups to challenge one another through a cyclical feedback process enhanced through the progressive acquisition of relevant knowledge. The PBL cyclical feedback process is hallmarked by the development of multiple iterations of proposals in response to the problem presented by the course instructor (Brocato, 2009). The proposals are presented for peer, self and instructor feedback in a repeating cycle until an end or desired product is developed.

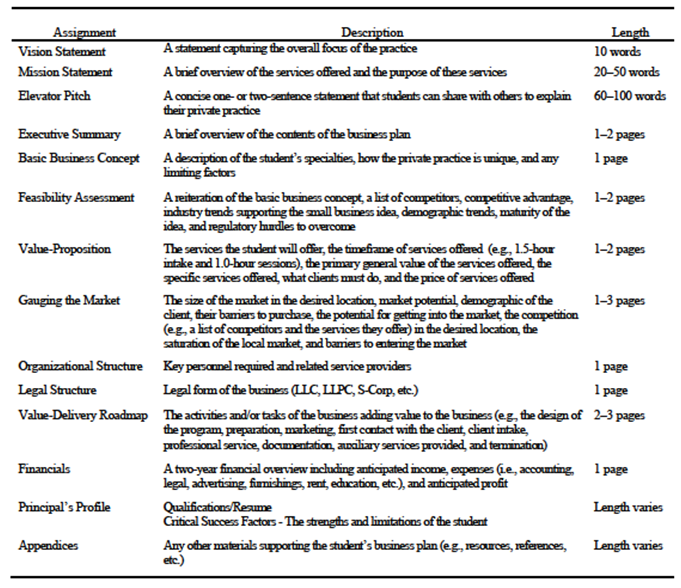

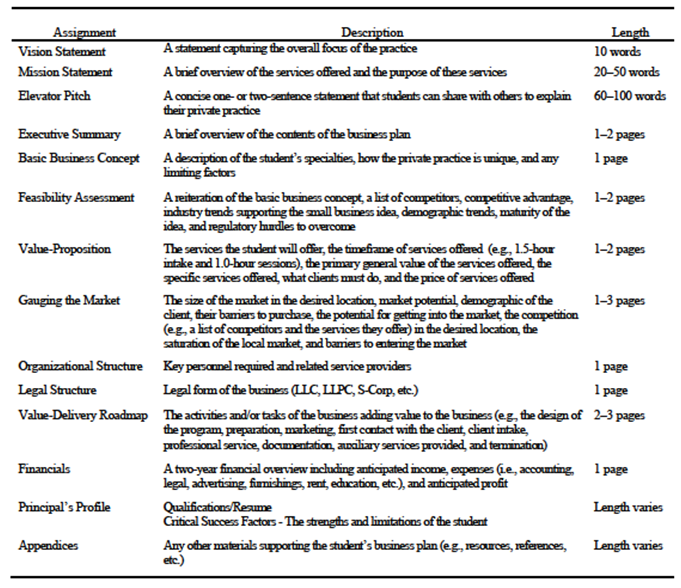

Table 1

Business Plan Outline

The PBL approach was utilized for this particular course because the goal of the course was for students to develop, maintain and enhance a sense of ownership over their visions for a counseling practice they hoped to pursue. Students were challenged to develop their business plan through multiple iterations of their proposal informed by course readings, in-class discussion, guest lectures, and peer and instructor feedback. The course and its structure are described below.

Learning Goals and Objectives

The primary learning goal of the course was to support students as they labored through the PBL approach to develop a detailed business plan relevant to their identified area of focus for a counseling practice (e.g., men in transition, couples and family, children, women’s issues). This goal was addressed by meeting the following objectives taken from the course syllabus, all of which provided students with practical knowledge about the development of a counseling practice:

1. Students will articulate the benefits and problems associated with starting a counseling practice and/or provide self-employed private services as an adjunct to other employment.

2. Students will think critically about entrepreneurship and the role of business in society.

3. Students will establish a coherent counseling practice value-proposition and a profitable value-delivery model.

4. Students will analyze the options for financing a counseling practice (e.g., grants, public monies, private funds).

5. Students will analyze the importance of marketing and its role in a successful business.

6. Students will understand the basics of business budgeting, bookkeeping and third-party payments.

Course Structure

The course utilized two textbooks that served as foundation for class discussion and weekly reading assignments. Grodzki’s (2000) Building Your Ideal Private Practice is a self-help book directed toward practitioners in the helping professions who wish to improve upon or develop their own counseling practices. Readings also were assigned from the textbook Entrepreneurial Small Business (Katz & Green II, 2011), which was written for students taking a course in entrepreneurship. These texts served as key resources to students in developing their business plans.

The instructors approached class time from the PBL framework, affording students the opportunity to critically think alone and within group settings about the feasibility of their individual counseling business-related ideas. Prior to each class students worked on one aspect of their business plan (e.g., vision statements, feasibility assessment, value proposition); these assignments served as the focus of class activities. Class time was structured to include substantial peer and instructor feedback, occasional guest speakers, mini-lectures by instructors on topics related to an aspect of the business plan, and student presentations. The instructors approached the class from a Socratic rather than a didactic style in order to provide students with the opportunity to take full ownership over their business ideas and plans. Because the course content could be covered efficiently and because the PBL design allowed for students to work independently, the class met two to three times each month for two hours each session; there were a total of ten sessions across the semester for the two–semester hour course.

Elements of class included brief, interactive PowerPoint presentations with handouts as a way for the instructors to bridge the gap between students’ lack of knowledge of business-related concepts and their developing business plans. In order to add an out-of-class component to student interaction, students used a classroom online forum (Blackboard Learning Technologies) where they posted 500- to 800-word reflections about assigned readings. In addition, students were required to provide feedback regarding the postings of two peers in order to provoke additional intellectual challenge to the reading-learning assignments. Beginning in the second class session, students provided one another in-class feedback about each assignment leading up to the final business plan; this feedback was transmitted in the form of peer reviews in pairs or in triads. Near the end of the course, students provided written feedback to a peer on a draft of their partner’s business plan, which was composed of all of the assignments up to that point. In the final class meeting each student presented his or her completed business plan and responded to comments and questions by fellow course participants from the perspective of “would you invest start-up money in this practice/ business concept?” The idea was that a well-developed and clearly articulated business plan could be used to seek startup investment if needed (Grodzki, 2000). Such an environment was facilitated to help students present clear and concise descriptions of their hypothetical counseling practices. Finally, guest speakers joined class discussions on two different occasions. One speaker was a counselor who had founded and ran a successful counseling practice that provided an array of clinical services including individual, group, and family counseling; in-home counseling; trauma-focused CBT; child-parent psychotherapy; grant-funded parent skills and development; mental health consultation to Head Start; safe touch programs; school-based counseling; as well as traditional insurance-based fee-for-service outpatient counseling. This practice employed multiple counselors, and the speaker provided students a rich sense of entrepreneurial possibilities that exist with a clinical practice. The other speaker ran a successful coaching and business development practice designed to assist mental health practitioners in developing or expanding their own clinical practice.

Class Assignments

Students developed their full business plans by completing a series of related subcomponent assignments outside of class that were discussed and critiqued in class. A brief overview of assignments regarding the development of the business plan is described in Table 1. The first two weeks of the course were dedicated to students thinking about and sharing their broad counseling practice ideas and narrowing these ideas into vision and mission statements that required the development of clarity as to the nature and scope of their proposed practice, including constituents served and market niche. Students were encouraged to contact and interview clinicians in private practice in their community of interest to provide greater clarity into their potential market niche and ask different questions related to the practitioners’ business structures. Students completed several iterations of their vision and mission statements and shared these in pairs and with the class. Students were then assigned a task from the Grodzki text to develop an “elevator pitch” for the practice, which was a brief, one- to two-sentence statement regarding the nature of the practice that an uninformed person could understand. The intention of developing such a statement was, according to Grodzki, to help students describe their practices in plain, nontechnical language that the potential consumer could easily grasp (i.e., “I work with couples and families who are tired of being tired and looking for a new way of doing their relationships”). Students shared, critiqued and modified these statements several times following the PBL model. Another assignment asked students to identify their perceived level of business-related competencies through completion of a business and technical skills self-assessment (e.g., sales, accounting, industry expertise, market knowledge) (Katz & Green, 2011, p. 61). This self-assessment served as an important foundation for a discussion that allowed students to share and normalize comforts and discomforts associated with their own self-efficacy in regard to business- and counseling-related competencies.

The feasibility assessment assignment challenged students to think critically about the viability of their proposed vision and mission statements by identifying their market niche, conducting an industry profile (i.e., identifying competitors), forecasting their one- and two-year expected revenues and examining market conditions in the location of their intended practice. Students found this assignment challenging because it forced them to achieve specific clarity about their mission and vision statements. The instructors responded to student needs in the development of the fundamental vision for their business by allowing students to progress on their assignments at a somewhat different pacing. Given the high-stakes nature of business feasibility, it was important not to arbitrarily rush this step to completion.

After students had developed clear mission statements and conducted feasibility assessments, the assignments flowed more cohesively. The subsequent assignment directed students to ascertain risk management strategies by identifying appropriate professional credentials, professional liability insurance, legal structure for their practice and a financial strategy for the business (e.g., self-pay, private insurance, grants, Medicaid). Students then were challenged to articulate a value proposition for their business by indicating how aspects of their practice would add value for their clients (i.e., what a client could expect to receive for the time and resources invested). Next, students developed marketing strategies, modeled how they would deliver value, and identified the time, logistical, regulatory, economic and expertise constraints that their practices would operate under. They also specified particular support that would be necessary to make their businesses thrive, including accounting, legal and any other relevant services to position their practice for success.

In week eight students developed a budget and financial plan to determine how much capital they would need to sustain the business to profitability over a two-year span. During the final two weeks of the course, students completed their business plans and provided one another detailed feedback about those plans. In the final iteration of their business plan, students identified critical success factors, including their strengths and areas for growth to help them succeed in implementing their plans.

Use of Class Time

Typically, the first 10–15 minutes of class were utilized to discuss students’ questions about business plan components that were the topic during that class. All students presented to the class a progress update on their business plans. This allowed students to provide one another with rich feedback and suggestions in tackling components of the plan. The instructors often placed students into dyads or triads for 20–30 minutes and asked students to provide thoughtful, yet honest feedback on their partners’ work. As this occurred, the instructors would listen in and provide strategic feedback in attempts to promote group interaction and group problem-solving. The class would reconvene and present overlying concerns that ran across business plans and consider how these concerns might be addressed in the next iteration of the plan. In the latter weeks of the course, the instructors invited several guest speakers to talk about their experiences in private practice. Class generally ended with a discussion of the upcoming aspect of the business plan, how students might approach this exercise, and brainstorming of resources that might assist students in answering questions.

Course Effectiveness: A Qualitative Exploration

Because the material in the course as well as the PBL pedagogy is likely unfamiliar to many counselor educators, below we provide readers what we consider to be key learnings for instructors as well as important feedback from students. Following the conclusion of the course, 12 qualitative interview questions were developed to collect feedback associated with the beneficial and/or challenging aspects of the course, fulfillment of course purposes, the utility of course activities, the evaluation of readings, the impact of the course on students ability to develop a business plan, and recommendations for improvements. A counselor educator with experience in developing qualitative interview questions provided feedback on the questions prior to data collection. The primary author completed semi-structured interviews with all students lasting from 15–30 minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded and later reviewed to capture general themes.

Collectively, students articulated that they benefited from the conversational and practical tone of the class, profited from developing a business plan in their interest area regardless of whether the student was a second-year master’s student or a seasoned counselor and desired a more robust bridge to connect business-related information to their plans. If one is considering teaching such a course, the points below may provide clarity and guidance for making decisions as to the structure of the course and how to facilitate student learning in this rather nontraditional approach to education.

It’s simple, but it isn’t easy. The challenge in teaching this course was not assisting students in gaining mastery over the content; rather, the difficulty lies in helping students apply the content to their unique situation. Much like providing clinical supervision or leading groups, this graduate course was as much about the process as about skill mastery. Although students expressed anxiety about the business-related terminology and concepts, terms introduced in the course were kept basic and easy to understand. However, students did struggle with gaining personal clarity about the type of clinical practice they hoped to create and then matching that clarity to a method of providing services. Overall, students felt confident in their abilities to implement their business plans by the end of the course. One student stated, “I have developed a clearer understanding on what my practice will look like and confidence in what it will look like to get there.”

Students further commented on how learning and applying business concepts were less familiar to them compared to counseling concepts. Students found the Grodzki (2000) text to be written in accessible language and characterized as inspirational in the way business concepts were clearly translated. Students further described Grodzki’s writing as inspiring, provoking them to “dream big,” and a text that one “would have picked up in the bookstore.” Conversely, students (and instructors) described the Katz and Green II (2011) reading as more challenging as it was written as a textbook for business school majors. One student indicated her preference for an “entrepreneurship for dummies kind of book” that would allow her to access and understand business concepts more readily. Such feedback suggested to the instructors that in future offerings of the course reader-friendly texts that are related to counseling and fostering students’ confidence are important. Less technical information may be a better fit for counseling students who are often at an early stage of business knowledge. For example, a very accessible text targeted toward an owner-operated entrepreneurial startup such as The Big Book of Small Business (Gegax, 2007) appears ideal.

Group counseling skills are useful. The class began with many of the issues that are present in a newly formed counseling group, including heightened anxiety and uncertainty about performance and expectations. For counseling students, thinking about the business aspects of their career was like learning a foreign language and subsequently there was self-doubt about articulating their fledgling ideas to their peers and the instructors for scrutiny.

Nevertheless, students reported that verbalizing their thoughts and anxieties assisted them in clarifying their future business intentions. By sharing their ideas, they gained clarity and could evaluate the feasibility of their business plan. Students suggested that although they initially felt uncomfortable sharing their ideas to the group because they took the feedback personally, it was an important aspect of developing a well-crafted plan.

Over the course of the semester, students reported feeling more comfortable in sharing their work. Initially, one student recalled that she felt like she and her peers were “just being kind of nice to each other.” By the class’s final session, however, students reported feeling relaxed while delivering their business plan and receiving feedback. In fact, several students reported the final presentation as the highlight of the class experience. As one student stated, “people were comfortable enough to throw out honest feedback.” As a result of sharing their business plans throughout the semester in an informal atmosphere, students reported gaining more perspective and clearer visions in developing a high quality business proposal.

Expect anxiety. As is often reported in the PBL literature, students reported that they wanted more concrete answers and structure than could be provided with a PBL approach and this ambiguity caused anxiety. They often wanted to know whether something was “right” or “wrong.” Feelings of frustration and uncertainty escalated as they confronted roadblocks in their planning, but these would subside as clarity was achieved. It became clear to students that the task of the instructors was to provide appropriate support as anxiety was encountered, with the full awareness that fears could not be completely alleviated; that was the students’ work. Providing the opportunity to struggle with the implications of their business plans allowed students to overcome self-doubts as they owned their decisions; this appeared to increase self-efficacy and optimism in the development of the business plan. Students overcame challenges they previously thought were implausible. As one student recalled, “I didn’t think I would have a final business plan at the end of the class, and I did.”

You can’t teach someone to have a good idea. Students had to labor with their ideas to reach their own conviction about the feasibility of the clinical practice they hoped to create. Therefore, the instructors’ evaluation of student ideas as solid or weak proved less important than the students’ exertion through the steps of developing the business plan. Students had to reach clarity for themselves and this did not appear to come from the instructors. One student said:

When a person is developing a plan, it’s their baby and they get really invested in it and you better not criticize the baby…but you need that [criticism], you need a fresh set of eyes to look at it and say, “Did you think about that? You know, that won’t work.” And they might be wrong. It’s okay. If they’re bringing it to your attention, then that’s really good.

Students in a course such as this will be excited about and protective of their ideas, yet need assistance in challenging their ideas so that more mature thinking can emerge.

It is best to hear about “the real world” from an expert. It was important to bring in outsiders (e.g., counselors in private practice, a business coach) to discuss the process of developing a counseling practice. Even though the instructors had similar insights to share, the reality of starting and managing a clinical practice gained credibility when students heard it from “the horse’s mouth.” The instructors invited guests who ran successful clinical practices who spoke with students about their experiences in establishing and managing their business. Hearing from someone actively engaged in the day-to-day struggles of running a clinical practice was extremely valuable both in terms of offering encouragement and in modeling success.

As mentioned earlier, one speaker ran a coaching and business development practice designed to assist mental health practitioners in establishing and/or maximizing the effectiveness of their clinical practice. This speaker has worked with hundreds of counselors and therapists across the U.S. and was able to address many of the anxieties (e.g., Will I make enough money? How long will it take to get established? What sort of overhead might I expect?) Students found this practical yet highly motivating speaker to be particularly beneficial.

Course Improvements

The more experts the better. The instructors invited several guest speakers who were successful helping professionals and students consistently found these talks to be helpful. The opportunity to hear from a person who had expertise in running a clinical practice gave the students confidence that they too could learn the skills needed to run their own practice. Experts from areas outside of the helping professions were not included (e.g., business management, accounting, law) although several students commented that the opportunity to hear from experts in such specialties may have been helpful in shaping their business plans. Such experts may have made some assignments “less nebulous” as one student put it. Having guests that represent support services such as attorneys or insurance agents might have helped students better understand how to address such issues in business plans. For example, “Do I need to call law firms or call insurance companies or do I just need to be thinking what are my expenses going to be? More clarity would have been helpful,” stated one student. From the post-course perspective, the instructors concluded that the more multidisciplinary the experts the better in order to add specialist insights to the course.

Struggle is the way forward. Unlike a course in which students are asked to read, digest, and repeat material on papers or tests, this material was much more personally connected to their deeper hopes and dreams; while the building of an actual plan to manifest those dreams was the principal outcome. Subsequently, the material held significant salience for the students; thus, being patient with their struggle was crucial. Instructor gentleness was particularly salient as students were forced to struggle to match their vision with the practical reality of developing and running a small business. In the words of one student:

In other [counseling] courses we start out with a broad topic and then you narrow it down and we didn’t have that natural progression (in this class). Instead, we immediately began talking about our ideas, our vision for our careers and the uncertainty as to whether this was something we could make a reality. So from the very beginning this material was more challenging because it was personal.

Indeed, it was clear that the personal nature of the material added to the challenge of course assignments, yet it was equally apparent that the material facilitated student creativity, drive and determination to develop a plan that captured their truest vision for their clinical practice.

Sometimes the instructor needs to get out of the way of the students. The challenge for the instructors was to provide feedback that helped students move deeper into the practical reality of their ideas without discouraging vision and aspirations or taking the idea in a direction that lacked interest. For example, questions like, “Have you considered who else in the area is providing services similar to the ones you hope to offer?” is much more facilitative than, “I doubt there is a market for that.” All students commented on the importance of both instructor and student feedback. For example, one student stated, “I didn’t always feel comfortable with the feedback, but it was necessary to help with the planning process.” Another student commented on how she would have preferred more peer feedback as opposed to relying on the instructors for the expansion of her ideas. She stated:

Sometimes when we presented ideas the instructors would run with ideas of their own. This helped to create a lot of energy, which was nice, but a balance between staying true to the person’s vision versus expanding it would have been helpful.

This comment demonstrates the student’s ownership of their ideas. The instructors found it an imperative challenge to remain true to the core of students’ ideas and ask critical guiding questions while minimizing the instructor’s own contributions. The instructors had to constantly remind themselves; while they may have many years of experience, it does not always translate into expert knowledge in the areas of students’ passions.

The answer isn’t in the book. Students struggled to accept that ultimately their practice vision was not found in any of the materials they read; they had to find it in themselves. Needless to say, this was harder for some students than for others. Like many courses within counselor preparation programs, this course required students to engage in an internal process of self-examination and introspection. Students were given the additional challenge of educating themselves about business aspects of clinical practice through reading, interviews with private practitioners in their communities of interest, market research and seeking feedback. The level of self-examination required was more difficult for some as the business plans were a documentation of crystallized ideas about their hopes for entering the field. Confronting the reality of an actual plan for their future livelihood, as opposed to simply hoping to help others was not always easy. Well-considered plans to make a counseling practice successful are often difficult to come by.

Regardless of their prior counseling or business experience, all students indicated that they benefited from the course and envisioned themselves implementing their business plans. A concern the instructors initially had in developing the course was whether entry-level graduate students or those several years away from developing a counseling practice could fully benefit from such a course. Some students shared these same concerns in their interviews. One master’s student had her doubts initially, but ended up feeling accomplished at the end of the course. Another entry-level graduate student nearing the end of her program of study shared confidently that she had gained tremendously from taking the course and that it had helped her clarify the populations she would like to serve. She stated that, “Other [counseling] classes prepare you to be a generalist…this class really helped me to get the specificity and the passion that I needed behind what I wanted.” Students emphasized that the course helped them clarify their goals not just for establishing a clinical practice, but also in regards to who they wanted to be as practitioners. One student said, “Once you are clear, then you know what to ask for and when you can ask for it; then you are open to getting that.” In a similar way, another student noted, “Because of the course I was able to strip away all the extraneous things and focus on kind of the core of what I want my business to be.” This course impacted students’ level of confidence and clarity in not only the kinds of practices they wanted to develop, but also what they wanted their identities to be as professional counselors. Students at all levels of counseling and business-related experience reported gaining professionally from taking the course. Students indicated that they appreciated and were challenged by the seminar style that provided a process for facilitated student and instructor feedback. Even though at times they wanted more guidance on assignments, students gained clarity about the types of clients they intended to work with, the practices they hoped to develop and the professionals they aspired to be.

Discussion

Both student and instructor reflections identified the strengths as well as the challenges of implementing the course, Entrepreneurship in Clinical Settings. Students reported benefiting from their experience as the development of the business plan forced them to narrow their focus and develop a feasible strategy for implementing their small business ideas. Students went from having broad and poorly formed ideas to a tangible focus for their practice that allowed them to explore the feasibility of their business model. Although some students were several years away from developing a clinical practice, at the conclusion of the course all reported clarity about their proposed business ideas and a sense of confidence in both themselves and the plans they believed would help shape a more specific counselor identity.

The idea of teaching business concepts may be intimidating to some counselor educators, especially those lacking experience running a counseling practice. While counselor educators with experience running a clinical practice are likely more prepared to instruct this course, this may not always be a possibility. Subsequently, for counselor educators who lack experience with a private clinical practice, consider recruiting a co-instructor with practice experience to assist with discussions of business-related concepts and the structuring of a practice. Another option is to consult closely with local counselors who run clinical practices and who can serve as guest speakers to provide students with the foundation needed to integrate business concepts into their practice plans.

One approach that could prove fruitful to teach foundational business concepts is to analyze an existing clinical practice as a case study to examine how networking, marketing, budgeting, operations, risk management, accounting and training are implemented. Analyzing a counseling practice with objectivity early in the course might enhance student relationship building and allow time to transition into a more highly interactive approach in the course’s remaining activities. The instructors learned from conversations with students that including a practice case study in the first portion of the course could be beneficial. Future iterations of the course will include a case study assignment to help students’ transition into developing their own business plans in the latter part of the course.

The class assignments and activities described help students think through and solve the problem of developing their own business plan. However, delaying the start of the PBL approach until after the initial concept-building stage may be a wise consideration. With the increased comfort caused by greater familiarity and higher competence in speaking the language of business with the knowledge accrued in the first segment of the course, students could better engage in lively and productive discussions as “roundtable advisors” about others’ clinical practice ideas and businesses. Students will have a greater ownership of the outcome of the course, if they see a strong link between course-content and outcomes that benefit them directly.

Overall, students enjoyed the seminar structure of the course and PBL pedagogy. They found the classroom environment to be a comfortable, conversational process as opposed to a top-down lecture-based method. Through this structure and the PBL pedagogy, equal responsibility was placed on all classroom participants to facilitate the learning process rather than relying on the instructors to provide information. Despite this freedom and overall satisfaction, students wanted to know in greater detail what the instructors expected from each assignment. When PowerPoint mini-lectures were included, students reported feeling better able to predict the knowledge and skills the instructors expected them to obtain.

Following the completion of the course an unsolicited email was received that described the impact of the course for a particular student. Although the statement’s generalizability is limited, it captures the instructors’ intention of teaching the course:

I cannot express to you how valuable and impactful your course has already been on me in my professional journey as a counselor, but I want to try. Throughout the course of graduate school, I was on the very necessary track of opening my understanding and competence in new areas. Every time I took a class, I could envision myself doing that kind of work: children, families, assessments, adults, adolescents, career, substance abuse, you get the idea. What that gave me in the end was the feeling that I could do anything – I could accept any entry-level counseling job and be successful. What I was lacking, however, was direction. What was my passion in all of this – beyond my desire to be a helper, to be a counselor? Through the progression of Entrepreneurship in Clinical Settings, I was forced to think about not just what I could do, but what I wanted to do and that idea kept refining itself until I became very clear about the fact that I want to work with pregnant women and women parenting young children. Getting clear about this gave me energy and purpose in my job search. Instead of looking on job boards for what was being advertised, I was able to look for agencies that offered the services I wanted to provide. I was able to put out the message into the universe that this was the type of job I wanted. Three days after graduation I was offered a job as an in-home therapist. I am working with pregnant women and women who are parenting children under the age of five who are working with a caseworker on child development issues, but have also requested a therapist to work on their own mental health issues. Not only do I have a job, I can honestly say I have my dream job, and I credit your class. I still plan to start a counseling practice after licensure, but until then I am getting invaluable experience and training working with my ‘ideal clients.’

References

Albanese, M. A., & Mitchell, S. (1993). Problem-based learning: A review of literature on its outcomes and implementation issues. Academic Medicine, 68, 52–81. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/pages/default.aspx.

Bouhuijs, P. A. J., & Gijselaers, W. H. (1993). Course construction in problem-based learning. In P. A. J. Bouhuijs, H. G. Schmidt & H. J. M. van Berkel (Eds.), Problem-based learning as an educational strategy (pp. 79–90). Maastricht: Network Publications.

Brocato, K. (2009). Studio based learning: Proposing, critiquing, iterating our way to person-centeredness for better classroom management. Theory Into Practice, 48, 138–146. doi:10.1080/00405840902776459

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2009). 2009 CACREP Standards. Retrieved from http://www. cacrep.org.

Cummings, N. A., Cummings, J. L., & O’Donohue, W. (2009). We are not a healthcare business: Our inadvertent vow of poverty. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 39, 7–15.

Gegax, T. (2007). The big book of small business: You don’t have to run your business by the seat of your pants. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Green, R. G., Baskind, F. R., Mustian, B. E., Reed, L. N., & Taylor, H. R. (2007). Professional education and private practice: Is there a disconnect? Social Work, 52, 151–159.

Grodzki, L. (2000). Building your ideal private practice. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Katz, J. A., & Green II, R. P. (2011). Entrepreneurial small business (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Knaup, A., & Piazza, M. (2007). Business employment dynamics data: Survival and longevity, II. Monthly Labor Review, 130, 3–10. Retrieved from http://stats.bls.gov/opub/mlr/mlrhome.htm.

Norman, N. R., & Schmidt, H. G., (1992). The psychological basis of problem-based learning: A review of the evidence. Academic Medicine, 67, 557–565. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/pages/default.aspx.

Reynolds, G. P. (2010). Private practice: Business considerations. Retrieved from http://counselingoutfitters.com/vistas/vistas10 Article_36.pdf.