Sep 16, 2016 | Article, Volume 6 - Issue 3

Christopher A. Sink

With the advent of a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) in schools, counselor preparation programs are once again challenged to further extend the education and training of pre-service and in-service school counselors. To introduce and contextualize this special issue, an MTSS’s intent and foci, as well as its theoretical and research underpinnings, are elucidated. Next, this article aligns MTSS with current professional school counselor standards of the American School Counselor Association’s (ASCA) School Counselor Competencies, the 2016 Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) Standards for School Counselors and the ASCA National Model. Using Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and Response to Intervention (RTI) models as exemplars, recommendations for integrating MTSS into school counselor preparation curriculum and pedagogy are discussed.

Keywords:multi-tiered system of supports, school counselor, counselor education, American School Counselor Association, Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, Response to Intervention

When new educational models are introduced into the school system that affect school counseling practice, the training of pre-service and in-service school counselors needs to be updated. A multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) is one such innovation requiring school counselors to further refine their skill set. In fact, during the school counseling profession’s relatively short history, counselors have experienced several major shifts in foci and best practices (Gysbers & Henderson, 2012). The latest movement surfaced in the 1980s, when school counselors were encouraged to revisit their largely reactive, inefficient and ineffective practices. Specifically, rather than supporting a relatively small proportion of students with their vocational, educational and personal-social goals and concerns, pre-service and in-school practitioners, under the aegis of a comprehensive school counseling program (CSCP) orientation, were called to operate in a more proactive and preventative fashion.

Although there are complementary frameworks to choose from, the American School Counselor Association’s (ASCA; 2012a) National Model: A Framework for School Counseling Programs emerged as the standard for professional practice, offering K–12 counselors an operational scaffold to guide their activities, interventions and services. Preliminary survey research suggests that counselors are performing their duties in a more systemic and collaborative fashion to more effectively serve students and their families (Goodman-Scott, 2013, 2015). Other rigorous accountability research examining the efficacy of CSCP practices supports this transformation of counselors’ roles and functions (Martin & Carey, 2014; Sink, Cooney, & Adkins, in press; Wilkerson, Pérusse, & Hughes, 2013). As a consequence of the increased demand for retraining, university-level counselor preparation programs and professional counseling organizations (e.g., American Counseling Association, ASCA, National Board for Certified Counselors) have generally responded in kind. Over the last few decades, K–12 school counselors have been instructed to move from a positional approach to their professional work to one that is programmatic and systemic in nature.

As mentioned above, the implementation of MTSS (e.g., Positive Behavioral Supports and Responses [PBIS] and Response to Intervention [RTI] frameworks) in the nation’s schools requires in-service counselors to augment their collaboration and coordination skills (Shepard, Shahidullah, & Carlson, 2013). Essentially, MTSS programs are evidence-based, holistic, and systemic approaches to improve student learning and social-emotional-behavioral functioning. They are largely implemented in educational settings using three tiers or levels of intervention. In theory, all educators are involved at differing levels of intensity. For example, classroom teachers and teacher aides are the first line (Tier 1) of support for struggling students. As the need might arise, other more “specialized” staff (e.g., school psychologists, special education teachers, school counselors, addictions counselors) may be enlisted to provide additional and more targeted student interventions and support (Tiers 2 or 3). Even though ASCA (2014) released a position statement broadly addressing school counselors’ roles and functions within MTSS schools, research is equivocal as to whether these practitioners are implementing these directives with any depth and fidelity (Goodman-Scott, 2015; Goodman-Scott, Betters-Bubon, & Donahue, 2016; Ockerman, Mason, & Hollenbeck, 2012; Ockerman, Patrikakou, & Feiker Hollenbeck, 2015). Moreover, school counselor effectiveness with MTSS-related responsibilities is an open question.

To sufficiently answer these accountability questions, there is a pressing need for university preparation programs to better educate nascent school counselors on MTSS, particularly on the fundamentals and effective ways PBIS and RTI can be accommodated within the purposes and practices of CSCPs (Goodman-Scott et al., 2016). While educational resources and research are plentiful, they are chiefly aimed at pre-service and in-service teachers and support staff working closely with special education students, such as school psychologists (Forman & Crystal, 2015; Owen, 2012; Turnbull, Bohanon, Griggs, Wickham, & Salior, 2002). Albeit informative, nearly all school counselor MTSS research and application publications are focused on in-service practitioners (ASCA, 2014; de Barona & Barona, 2006; Donohue, 2014; Goodman-Scott, 2013; Martens & Andreen, 2013; Ockerman et al., 2012; Ryan, Kaffenberger, & Carroll, 2011; Shepard et al., 2013; Zambrano, Castro-Villarreal, & Sullivan, 2012). With perhaps the exception of Goodman-Scott et al. (2016), who provided a useful alignment of the ASCA National Model (2012a) with PBIS practices, there are few evidence-based resources for school counselor educators to draw upon in order to rework their pre-service courses to include MTSS curriculum and instruction. To successfully prepare counselors to work within PBIS or RTI schools, students must understand the ways MTSS foci are aligned with professional counseling standards for practice. Such a document is noticeably absent from the literature.

The primary intent of this article is to offer school counselor educators functional and literature-based recommendations to enhance their MTSS training of pre-service counselors. To do so, MTSS programs are first contextualized by summarizing their major foci, operationalization, theoretical underpinnings and research support. Next, the objectives of MTSS models are aligned with the ASCA (2012b) School Counselor Competencies and the 2016 CACREP Standards for School Counselors. Finally, using PBIS and RTI models as exemplars, recommendations for school counselor preparation curriculum and pedagogy are offered.

Foundational Considerations

Since MTSS programs are extensively described in numerous publications (e.g., Bradley, Danielson, & Doolittle, 2007; Carter & Van Norman, 2010; Forman & Crystal, 2015; R. Freeman, Miller, & Newcomer, 2015; Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006; Horner, Sugai, & Lewis, 2015; McIntosh, Filter, Bennett, Ryan, & Sugai, 2010; Sandomierski, Kincaid, & Algozzine, 2007; Sugai & Simonsen, 2012), including articles in this special issue, there is little need to reiterate the details here. However, for those school counselor educators and practitioners who are less conversant with MTSS’s theoretical grounding, research evidence and operational characteristics supporting implementation, these topics are overviewed.

MTSS programs by definition are comprehensive and schoolwide in design, accentuating the importance of graduated levels of student support. In other words, the amount of instructional and behavioral support gradually increases as the student’s assessed needs become more serious. Although the most prominent and well-researched MTSS approaches, PBIS and RTI, are considered disparate frameworks to address student deficits (Schulte, 2016), the extent of their overlap in theoretical principles, foci, processes and practices allows for an abbreviated synthesis (R. Freeman, et al., 2015; Sandomierski et al., 2007; Stoiber & Gettinger, 2016).

Initially, RTI and PBIS programming and services emerged from special education literature and best practices. Over time these evidence-based approaches extended their reach, and the entire student population is now served. Specifically, PBIS aims to increase students’ prosocial behaviors and decrease their problem behaviors as well as promote positive and safe school climates, benefitting all learners (Bradley et al., 2007; Carter & Van Norman, 2010; Klingner & Edwards, 2006). Although RTI programs also address students’ behavioral issues, they largely focus on improving the academic development and performance of all children and youth through high-quality instruction (Turse & Albrecht, 2015; Warren & Robinson, 2015). RTI staff are particularly concerned with those students who are academically underperforming (Greenwood et al., 2011; Johnsen, Parker, & Farah, 2015; Ockerman et al., 2015; Sprague et al., 2013). Curiously, the potential roles and functions of school counselors within these programs were not delineated until many years after they were first introduced (Warren & Robinson, 2015). Even at this juncture, often cited MTSS publications neglect discussing school counselors’ contributions to full and effective implementation (Carter & Van Norman, 2010). Instead they frequently refer to behavior specialists as key members of the MTSS team (Horner, Sugai, & Anderson, 2010).

MTSS Theory and Research

PBIS and RTI model authors and scholars consistently implicate a range of conceptual orientations, including behaviorism, organizational behavior management, scientific problem-solving, systems thinking and implementation science (Eber, Weist, & Barrett, n.d.; Forman & Crystal, 2015; Horner et al., 2010; Kozleski & Huber, 2010; Sugai & Simonsen, 2012; Sugai et al., 2000; Turnbull et al., 2002). It appears, however, that behavioral principles and systems theory are most often credited as MTSS cornerstones (Reschly & Cooloong-Chaffin, 2016). Since PBIS and RTI are essentially special education frameworks, it is not surprising that behaviorist constructs and applications (e.g., reinforcement, applied experimental behavior analysis, behavior management and planning, progress monitoring) are regularly cited (Stoiber & Gettinger, 2016). Furthermore, MTSS frameworks are in concept and practice system-wide structures (i.e., student-centered services, processes and procedures that are instituted across a school or district), and as such, holistic terminology consistent with Bronfrenbrenner’s bioecological systems theory and other related systems orientations (e.g., Bertalanffy general systems theory and Henggeler and colleagues’ multi-systemic treatment approach) are commonly cited (see Reschly & Cooloong-Chaffin, 2016, and Shepard et al., 2013, for examples of extensive discussions).

MTSS research largely demonstrates the efficacy of PBIS and RTI models. For instance, Horner et al. (2015) conducted an extensive analysis of numerous K–12 PBIS studies, concluding that this systems approach is evidence-based. Other related literature reviews indicated that PBIS frameworks are at least modestly serviceable in preschools (Carter & Van Norman, 2010), K–12 schools (Horner et al., 2010; Molloy, Moore, Trail, Van Epps, & Hopfer, 2013), and juvenile justice settings (Jolivette & Nelson, 2010; Sprague et al., 2013). Across most studies, PBIS programming yields weak to moderately positive outcomes for PK–12 students from diverse backgrounds (e.g., African American and Latino) and varying social and academic skill levels (Childs, Kincaid, George, & Gage, 2015; J. Freeman et al., 2015, 2016). Similarly, evaluations of RTI interventions are promising for underachieving learners (Bradley et al., 2007; Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006; Greenwood et al., 2011; Proctor, Graves, & Esch, 2012; Ryan et al., 2011). Students tend to especially benefit from Tier 2 and 3 interventions. In their entirety, PBIS and RTI models are modestly successful frameworks to identify students at risk for school-related problems and ameliorate social-behavioral and academic deficiencies. It should be noted, however, that the long-term impact of MTSS on students’ social-emotional outcomes remains equivocal (Saeki et al., 2011). As mentioned previously, there is a paucity of evidence demonstrating that school counselors indirectly or directly contribute to positive MTSS outcomes. As with any relatively new educational innovation, research is needed to further clarify the specific impacts of MTSS on student, family, classroom and school outcome variables. The next section summarizes the ways MTSS frameworks are viewed and instituted in school settings.

Operational Features

For school counselors to be effective MTSS leaders and educational partners, they must understand the conceptual underpinnings and operational components and functions of PBIS and RTI frameworks. Given the introductory nature of this article, we limit our discussion to essential characteristics of these frameworks. Extensive practical explanations of MTSS models abound in the education (R. Freeman et al. 2015; Preston, Wood, & Stecker, 2016; Turse & Albrecht 2015) and school counseling literature (Goodman-Scott et al., 2016; Ockerman et al., 2012, 2015). To reiterate, MTSS frameworks are designed to be systems or ecological approaches to assisting students with their educational development and improving academic and behavioral outcomes. As described below, they attempt to serve all students through graduated layers of more intensive interventions. School counselors deliver, for example, evidence-based services to students, ranging from classroom and large group interventions to those provided to individual students in the counseling office (Forman & Crystal, 2015). By utilizing systematic problem-solving strategies and behavioral analysis tools to guide effective practice (Sandomierski et al., 2007), students who are most at risk for school failure and behavioral challenges are provided with more individualized interventions (Horner et al., 2015).

Practically speaking, MTSS processes and procedures vary from school to school, district to district. To understand how these frameworks are operationalized, there are numerous online school-based case studies to review. For instance, at the PBIS.org Web site, Ross (n.d.), the principal at McNabb Elementary (KY), overviewed the ways a PBIS framework was effectively implemented at his school. Most importantly, the reach of PBIS programming was expanded to all students, requiring a higher level of educator collaboration and “buy in.” Other pivotal changes were made, including (a) faculty and staff visits to students’ homes (i.e., making closer “positive connections”); (b) the implementation of summer programs for student behavioral and academic skill enrichment; (c) additional school community engagement activities (e.g., movie nights, Black History Month Extravaganza); and, (d) further PBIS training to improve school discipline and classroom management strategies. Other MTSS schools stress the importance of carefully identifying students in need of supplemental services and interventions using research-based assessment procedures (e.g., functional behavioral analysis or functional behavioral assessment [FBA]). Most schools emphasize these key elements to successful schoolwide PBIS implementation: (a) data-based decision making, (b) a clear and measurable set of behavioral expectations for students, (c) ongoing instruction on behavioral expectations, and (d) consistent reinforcement of appropriate behavior (PBIS.org, 2016).

Furthermore, MTSS frameworks, such as PBIS and RTI, have two main functions. First, they offer an array of activities and services (prevention- and intervention-oriented) that are systematically introduced to students based on an established level of need. Second, educators carefully consider the learning milieu, particularly as it may influence the development and improvement of student behavior (social and emotional learning [SEL] and academic performances). MTSS staff must be well educated on the signs of student distress, including those indicators that suggest students are at risk for school-related difficulties (e.g., below grade level academic achievement, social and emotional challenges, mental health disorders, long-term school failure). Moreover, educators should be provided appropriate training on various assessment tools to determine which set of students require more intensive care.

Within a triadic support system, all students (Tier 1: primary or universal prevention) are at least monitored and assisted by classroom staff. Teachers are encouraged to document student progress (or lack thereof) toward academic and behavioral goals. At the first level, school counselors partner with other building educators to conduct classroom activities and guidance to promote academic success, SEL (e.g., prosocial behaviors), and appropriate school behavior (Donohue, 2014). Counselors also may assist with setting behavioral expectations for students, suggest differentiated instruction for academic issues, collect data for program decision making, and conduct universal screening of students in need of additional behavior support (Horner et al., 2015). In short, the aim of Tier 1 is to (a) support all student learning and (b) proactively recognize individuals displaying the warning signs of learning or social and behavioral challenges.

Once the signals of educational or behavioral distress become more pronounced, relevant staff may initiate a formal MTSS process. For example, in many states and school districts, within the context of an MTSS, the struggling learner becomes a “focus of concern” and a multidisciplinary or school support team is convened (Kansas MTSS, 2011). Panel members are generally comprised of the school psychologist, administrator, counselor and relevant teachers. Counselors may be asked to collaborate with other educators to appraise the student’s learning environments. If potential hindrances are detected, these must be sufficiently attended to before further educational intervention is provided. Once the determination is made that the “targeted” learner received high-quality academic and behavioral instruction, and yet continues to exhibit deficiencies, the student is considered for Tier 2 services (Horner et al., 2015). School counselor tasks at this level may include providing evidence-based classroom interventions, short-term individual or group counseling, progress monitoring and regular school–home communication. Other sample interventions might involve the application of a behavior modification plan, the assignment of a peer mentor and tutoring system, and the utilization of “Check and Connect” (Maynard, Kjellstrand, & Thompson, 2013) or Student Success Skills (Lemberger, Selig, Bowers & Rogers, 2015) programs.

In most cases, identified students make at least modest progress at Tier 2 and do not require tertiary intervention. Even so, a small percentage of students receive Tier 3 services involving, for example, a comprehensive FBA, additional linking of academic and behavioral supports, and more specialized attention (Horner et al., 2015). School counselor support at this level commonly incorporates and extends beyond Tier 2 services. Ongoing consultation with and referrals to community-based professionals (e.g., learning experts, marriage and family counselors, child psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists) and out- or in-patient treatment facilities may be necessary.

In summary, the essential focus of collaborative MTSS programming is to improve student performance by first carefully assessing student strengths and weaknesses. Once these characteristics are identified, the MTSS team, with input from the school counseling staff, develops learning outcomes and, as required, may institute whole-school, classroom, or individual activities and services to best address lingering student deficiencies. As such, counselors should be significant partners with other appropriate staff to deliver the needed assistance and support (e.g., assign a peer mentor, provide individual or group counseling, institute a behavior management plan) to address students’ underdeveloped academic or social-emotional and behavioral skills. To close the MTSS loop, follow-up assessment of student progress toward designated learning and behavioral targets is regularly conducted by teachers with assistance from counselors and other related specialists. Based on the evaluation results, further interventions may be prescribed. School counselors therefore contribute essential MTSS services at each tier, promoting through their classroom work, group counseling and individualized services a higher level of student functioning. Regrettably, anecdotal evidence and survey research suggest that many are ill-equipped to conduct the requisite prevention and intervention activities (Ockerman et al., 2015). The following sections attempt, in part, to rectify this situation.

Alignment of MTSS With Professional School Counselor Standards and Practice

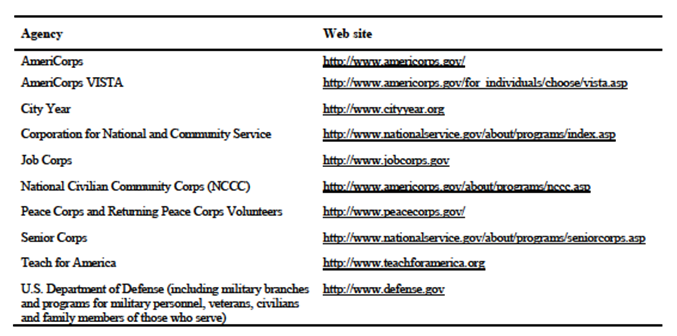

Before considering the implications for pre-service school counselor preparation, school counselors and university-level counselor educators should benefit from understanding the ways in which MTSS school counselor-related roles and functions are consistent with the preponderance of the ASCA (2012b) School Counselor Competencies and CACREP (2016) School Counseling Standards. Because there are so few publications documenting school counselor roles and functions within MTSS frameworks, a standards crosswalk, or matrix, was developed to fill this need (see Table 1). It should be noted that the ASCA standards and CACREP competencies are largely consistent with the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards’ (National Board; 2012) School Counseling Standards for School Counselors of Students Ages 3–18+. As such, they were not included in the table.

Table 1

Crosswalk of Sample School Counselor MTSS Roles and Functions, ASCA (2012b) School Counselor Competencies, and CACREP (2016) School Counseling Standards

| MTSS School Counselor Roles and Functions* |

ASCA School Counselor

Competencies

|

CACREP Section 5: Entry-Level Specialty Areas – School Counseling

|

|

I. School Counseling Programs

B: Abilities & Skills

|

1. Foundations 2. Contextual Dimensions

3. Practice

|

Shows strong school

leadership |

I-B-1c. Applies the school counseling themes of leadership, advocacy, collaboration and systemic change, which are critical to a successful school counseling program |

2.d. school counselor roles in school leadership and multidisciplinary teams |

|

I-B-2. Serves as a leader in the school and community to promote and support student success |

|

| Collaborates and consults with relevant stakeholders |

I-B-4. Collaborates with parents, teachers, administrators, community leaders and other stakeholders to promote and support student success |

3.l. techniques to foster collaboration and teamwork within schools |

Collaborates as needed to provide integration of

services |

I-B-4b. Identifies and applies models of collaboration for effective use in a school counseling program and understands the similarities and differences between consultation, collaboration and counseling and coordination strategies |

1.d. models of school-based collaboration and consultation |

|

I-B-4d. Understands and knows how to apply a consensus-building process to foster agreement in a group |

Provides staff development related to positive

discipline, behavior and mental health |

I-B-4e. Understands how to facilitate group meetings to effectively and efficiently meet group goals |

| Leads with systems change to provide safe school |

I-B-5. Acts as a systems change agent to create an environment promoting and supporting student success |

2.a. school counselor roles as leaders, advocates and systems change agents in PK–12 schools |

Intervention planning for SEL and academic skill

improvementProvides risk and threat

assessments |

I-B-5b. Develops a plan to deal with personal (emotional and cognitive) and institutional resistance impeding the change process |

2.g. characteristics, risk factors, and warning signs of students at risk for mental health and behavioral disorders;2.h. common medications that affect learning, behavior and mood in children and adolescents;2.i. signs and symptoms of substance abuse in children and adolescents as well as the signs and symptoms of living in a home where substance use occurs;3.h. skills to critically examine the connections between social, familial, emotional and behavior problems and academic achievement |

|

II. Foundations B: Abilities and Skills |

|

II-B-4. Applies the ethical standards and principles of the school counseling profession and adheres to the legal aspects of the role of the school counselor |

2.n. legal and ethical considerations specific to school counseling |

|

II-B-4c. Understands and practices in accordance with school district policy and local, state and federal statutory requirements |

2.m. legislation and government policy relevant to school counseling |

|

III. Management B: Abilities and Skills |

| Effective collection, evaluation, interpretation and use of data to improve availability of services |

III-B-3. Accesses or collects relevant data, including process, perception and outcome data, to monitor and improve student behavior and achievement |

1.e. assessments specific to PK–12 education |

| Assists with schoolwide data management for documentation and decision making |

III-B-3a. Reviews and disaggregates student achievement, attendance and behavior data to identify and implement interventions as needed |

| Collects needs assessment data to better inform culturally relevant practices |

III-B-3b. Uses data to identify policies, practices and procedures leading to successes, systemic barriers and areas of weakness |

|

III-B-3c. Uses student data to demonstrate a need for systemic change in areas such as course enrollment patterns; equity and access; and achievement, opportunity and/or information gaps |

3.k. strategies to promote equity in student achievement and college access |

|

III-B-3d. Understands and uses data to establish goals and activities to close the achievement, opportunity and/or information gap |

|

III-B-3e. Knows how to use data to identify gaps between and among different groups of students |

| Measures student progress of schoolwide interventions with pre/post testing |

III-B-3f. Uses school data to identify and assist individual students who do not perform at grade level and do not have opportunities and resources to be successful in school |

|

Promotes early intervention Designs and implements

interventions to meet the behavioral and mental health needs of students |

III-B-6a. Uses appropriate academic and behavioral data to develop school counseling core curriculum, small-group and closing-the-gap action plans and determines appropriate students for the target group or interventions |

3.c. core curriculum design, lesson plan development, classroom management strategies and differentiated instructional strategies |

|

III-B-6c. Creates lesson plans related to the school counseling core curriculum identifying what will be delivered, to whom it will be delivered, how it will be delivered and how student attainment of competencies will be evaluated |

Provides academic

interventions directly to students |

III-B-6d. Determines the intended impact on academics, attendance and behavior |

3.d. interventions to promote academic development |

|

III-B-6g. Identifies data collection strategies to gather process, perception and outcome data |

|

| Coordinates efforts and ensures proper communication between MTSS staff, students and family members |

III-B-6h. Shares results of action plans with staff, parents and community |

|

|

III-B-7b. Coordinates activities that establish, maintain and enhance the school counseling program as well as other educational programs |

|

|

IV. Delivery B: Abilities and Skills |

|

Provides specialized

instructional support |

IV-B-1d. Develops materials and instructional strategies to meet student needs and school goals |

3.c. core curriculum design, lesson plan development, classroom management strategies and differentiated instructional strategies |

|

IV-B-1g. Understands multicultural and pluralistic trends when developing and choosing school counseling core curriculum |

|

IV-B-1h. Understands and is able to build effective, high-quality peer helper programs |

3.m. strategies for implementing and coordinating peer intervention programs |

| Engages in case management to assist with social-emotional and academic concerns |

IV-B-2b. Develops strategies to implement individual student planning, such as strategies for appraisal, advisement, goal-setting, decision making, social skills, transition or post-secondary planning |

3.g. strategies to facilitate school and postsecondary transitions |

| Understands social skills development |

IV-B-2g. Understands methods for helping students monitor and direct their own learning and personal/social and career development |

3.f. techniques of personal/social counseling in school settings |

| Provides interventions at three levels |

IV-B-3. Provides responsive services |

|

IV-B-3c. Demonstrates an ability to provide counseling for students during times of transition, separation, heightened stress and critical change |

| Coordinating with community service providers and integrating intensive interventions into the schooling process |

IV-B-4a. Understands how to make referrals to appropriate professionals when necessary |

2.k. community resources and referral sources |

Train/present information to school staff on data

collection and analysis |

IV-B-5a. Shares strategies that support student achievement with parents, teachers, other educators and community organizations |

2.b. school counselor roles in consultation with families, PK–12 and postsecondary school personnel, and community agencies |

Implements appropriate

interventions at each tier |

IV-B-5b. Applies appropriate counseling approaches to promoting change among consultees within a consultation approach |

|

|

V. Accountability B: Abilities and Skills |

| Collects, analyzes, and interprets school-level data to improve availability and effectiveness of services and interventions Uses progress monitoring data to inform counseling interventions |

V-B-1g. Analyzes and interprets process, perception and outcome data |

3.n. use of accountability data to inform decision making3.o. use of data to advocate for programs and students |

| Understands history, rationale, and benefits of MTSS |

|

|

Note. *Primary sources: ASCA (2012b, 2014); CACREP (2016); Cowan, Vaillancourt, Rossen, & Pollitt, (2013);

Ockerman et al. (2015).

The MTSS School Counselor Roles and Functions column was generated from several sources, including a recent study examining school counselors’ RTI perspectives (Ockerman et al., 2015), ASCA’s (2014) RTI position statement, and a lengthy school psychology publication that specifically addresses school counselor roles in creating safe MTSS schools (Cowan, Vaillancourt, Rossen, & Pollitt, 2013). Essentially, the crosswalk reveals that K–12 school counselor MTSS roles and functions correspond substantially with the ASCA (2012b) School Counselor Competencies and CACREP (2016) Standards. Similarly, MTSS school counselor tasks fit well within the broad and longstanding role categories traditionally associated with counseling services: (a) coordination of CSCP services, interventions and activities; (b) collaboration with school staff and other stakeholders; (c) provision of responsive services (e.g., individual and group counseling, classroom interventions, peer helper and support services, crisis intervention); (d) consultation within school constituencies and external resource personnel; and (e) classroom lessons (i.e., MTSS Tier 1 services; Burnham & Jackson, 2000; Goodman-Scott et al., 2016; Gysbers & Henderson, 2012; Schmidt, 2014; Sink, 2005). Since the ASCA (2012a) National Model also is a systemic and structural model aimed at whole-school prevention and intervention of student issues, school counselor MTSS roles (direct and indirect services) also align reasonably well with the model’s components (e.g., foundation, management, delivery and accountability; Goodman-Scott et al., 2016). In short, including MTSS into the pre-service training of school counselors is professionally defensible as well as best practice.

Implications for School Counselor Preparation

PBIS and RTI frameworks are now firmly established in a majority of U.S. schools. As documented above, research, particularly within the context of special education, largely demonstrates their positive impact on student academic achievement and SEL skill development, as well as on school climate (Horner et al., 2010, 2015; McDaniel, Albritton, & Roach, 2013). However, school counselors in the field report a lack of MTSS knowledge and their roles and functions within at least RTI schools are somewhat inconsistently and ambiguously defined (Ockerman et al., 2015). In some circumstances, school counselors’ MTSS duties may not fully complement their CSCP responsibilities (Goodman-Scott et al., 2016). Given these realities, many school counselor preparation programs need to be revised to effectively account for these limitations. To accomplish this end, the following literature-based action steps are offered. First, counselor educators should conduct a program audit, looking for MTSS curricular and instructional gaps in their school counseling preparation courses. Curriculum mapping (Jacobs, 1997) is a useful tool to recognize program content deficiencies (Howard, 2007). Essentially, the process involves

the identification of the content and skills taught in each course at each level. A calendar-based chart, or “map,” is created for each course so that it is easy to see not only what is taught in a course, but when it is taught. Examination of these maps can reveal both gaps in what is taught and repetition among courses, but its value lies in identifying areas for integration and concepts for spiraling. (Howard, 2007, p. 7)

Second, the various options for program revision should be weighed. The two most obvious alternatives are to either add a separate school counseling-based MTSS course or to augment existing courses and their content. Classes already focusing on topics associated with MTSS theory, research and practice (e.g., special education, at-risk children and adolescents, comprehensive school counseling, strengths-based counseling and advocacy) are perhaps the easiest to modify. Certainly, accreditation standards and requirements, funding implications, and logistical concerns must be considered.

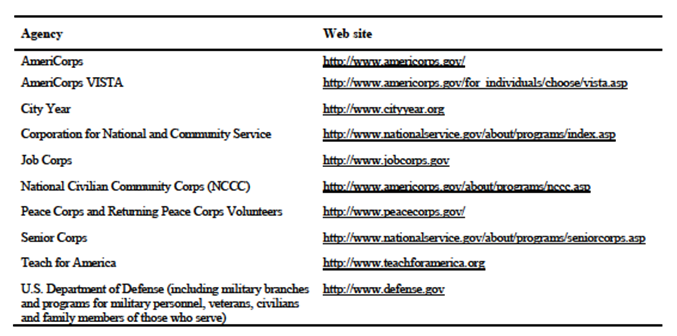

Third, specific MTSS content and related skills should be reviewed and syllabi revised accordingly. To inform decision making and planning, Table 2 provides sample core MTSS content areas associated with school counselor roles and functions. Curriculum changes might involve strengthening these four broad areas: (a) assessment, data usage and research, (b) general knowledge and practices, (c) specific interventions, and (d) systems work. To alleviate potential redundancies in pre-service education, it is imperative that any proposed modifications be aligned with current CSCP training (e.g., ASCA’s [2012a] National Model; see Goodman-Scott et al., 2016 for details). Consult the crosswalk provided in Table 1 to ensure that any course changes are consonant with ASCA’s (2012b) School Counselor Competencies and CACREP (2016) standards.

Table 2

Core MTSS Content Areas Aligned With School Counselor Roles and Functions

|

Content Areas

|

| Assessment, Data Usage and ResearchAcademic and SEL skill assessment and progress monitoringApplied experimental analysis of behavior/functional behavior analysis (FBA)Behavioral consultation assessmentEvidence-based (data-based) decision making and intervention planning (academic and social-behavioral issues)Research methods (e.g., survey, pre/posttest comparison, single subject designs)Student and classroom assessment/testingUse of student assessment and schoolwide data to improve MTSS services and interventions |

| General Knowledge and PracticesBest practices in support of academic and social-behavioral developmentIntegration with comprehensive school counseling programs (e.g., ASCA National Model)Ethical and legal issuesEducational, developmental and psychological theories (e.g., behaviorism, social learning theory, ecological systems theory, cognitive, psychosocial, identity)Effective communicationStudents at risk and resiliency issues (i.e., knowledge of early warning signs of school and social-behavioral problems)Leadership and advocacyMental health issues and associated community servicesModels of consultation

Multicultural/diversity (student, family, school, community) and social justice issues

Referral

Special education (e.g., relevant policies, identification procedures, categories of disability) |

| Specific InterventionsCheck and Connect (Check In, Check Out)Individualized positive behavior support (e.g., behavior change plans, individualized education plans)Peer mentoring/tutoringSchoolwide classroom guidance (academic and SEL skill related)Short-term goal-oriented individual and group counseling |

| Systems WorkCollaboration and coordination of services with counseling staff, MTSS constituents, external resources and familiesConsultation with caregivers, educational staff and external resourcesStaff coaching/liaison work (e.g., conducting workshops and training events to improve conceptual knowledge and understanding as well as skill development)MTSS (PBIS & RTI) structure and components and associated practicesResource providers (in-school and out-of-school options)Policy development addressing improved school environments and barriers to learning for all studentsSystems/interdisciplinary collaboration and leadership within context of comprehensive school counseling programs |

Note. Primary sources: Cowan et al. (2013); Forman & Crystal (2015); R. Freeman et al. (2015); Gibbons & Coulter

(2016); Goodman-Scott et al. (2016); Horner et al. (2015); Ockerman et al. (2015); Reschly & Coolong-Chaffin (2016).

Finally, course syllabi need to be updated to integrate desired curricular changes and appropriate instructional techniques instituted. It is recommended that counselor educators design the MTSS course using a spiral curriculum (Bruner, 1960; Howard, 2007). This theory- and research-based strategy rearranges the course material curriculum and content in such a way that knowledge and skill development and content build upon each another while gradually increasing in complexity and depth. Research informed pedagogy suggests that MTSS course content be taught using a variety of methods, including direct instruction for learning foundational materials and student-centered approaches, such as case studies and problem-based learning (PBL), for the application component (Dumbrigue, Moxley, & Najor-Durack, 2013; Ramsden, 2003; Savery, 2006). Specifically, given that scientific (systematic problem-solving) and data-driven decision making are indispensable educator practices within MTSS frameworks, these skills should be nurtured through “hands on” and highly engaging didactic methods rather than relying on conventional college-level teaching strategies (e.g., recitation, questioning and lecture; Stanford University Center for Teaching and Learning, 2001). Specific activities could be readily implemented during practicum and internship. PBL invites students to tackle complex and authentic (real world) issues that promote understanding of content knowledge as well as interpretation, analytical reasoning, interpersonal communication and self-assessment skills (Amador, Miles, & Peters, 2006; Loyens, Jones, Mikkers, & van Gog, 2015). Problems can take the form of genuine case studies (e.g., a sixth-grader at risk for severe depression), encouraging pre-service counselors to reflect on issues they will face in MTSS schools. Succinctly stated, when developing a new course or refining existing courses to include MTSS elements, counselor educators are encouraged to use research-based methods of curriculum design and student-centered pedagogy.

Conclusion

School counselor roles and functions must be responsive to societal changes and educational reforms. These shifts require university-level counselor preparation programs to be adaptable and open to new practices. K–12 schools around the nation are committed to instituting MTSS (PBIS and RTI) to better educate all students as well as to reduce the number of learners at risk for academic and social and emotional problems. School counselors largely indicate that they require further training on these MTSS frameworks and best practice (Goodman-Scott et al., 2016; Ockerman et al., 2015). It is therefore incumbent upon counselor education programs to revise their curriculum and instruction to meet this growing need. This article provides a clear rationale for instituting pre-service program changes, as well as summarizes MTSS’s theoretical and research foundation. Literature-based recommendations for pre-service course and curricular modifications have been offered. Preparation courses are encouraged to align their MTSS curriculum and content with ASCA’s (2012b) and CACREP’s (2016) school counseling standards, and the role requirements of comprehensive school counseling programs. Subsequent research is needed to determine whether this added level of pre-service education support actually impacts school counselor MTSS competency perceptions, and more importantly, whether schoolchildren and youth are positively impacted by better trained professional school counselors.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interestor funding contributions for the development of this manuscript.

References

Amador, J. A., Miles, L., & Peters, C. B. (2006). The practice of problem-based learning: A guide to implementing PBL in the college classroom. Boston, MA: Anker Publishing.

American School Counselor Association. (2012a). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

American School Counselor Association. (2012b). ASCA school counselor competencies. Retrieved from

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/home/SCCompetencies.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2014). The school counselor and multitiered system of supports. American School Counselor Association Position Statement. Retrieved from http://schoolcounselor.org/asca/

media/asca/PositionStatements/PS_MultitieredSupportSystem.pdf

Bradley, R., Danielson, L., & Doolittle, J. (2007). Responsiveness to intervention: 1997 to 2007. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39(5), 8–12. doi:10.1177/004005990703900502

Bruner, J. (1960). The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burnham, J. J., & Jackson, C. M. (2000). School counselor roles: Discrepancies between actual practice and exist-

ing models. Professional School Counseling, 4, 41–49.

Carter, D. R., & Van Norman, R. K. (2010). Class-wide positive behavior support in preschool: Improving teacher implementation through consultation. Early Childhood Education Journal, 38, 279–288.

Childs, K. E., Kincaid, D., George, H. P., & Gage, N. A. (2015). The relationship between school-wide imple- mentation of positive behavior intervention and supports and student discipline outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(2), 89–99. doi:10.1177/1098300715590398

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2016). 2016 CACREP standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Cowan, K. C., Vaillancourt, K., Rossen, E., & Pollitt, K. (2013). A framework for safe and successful schools [Brief]. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Retrieved from https://www.nasponline.

org/Documents/Research%20and%20Policy/Advocacy%20Resources/Framework_for_Safe_and_Suc

cessful_School_Environments.pdf

Donohue, M. D. (2014). Implementing positive behavioral interventions and supports: School counselors’ perceptions of student outcomes, school climate and professional effectiveness. Retrieved from http://works.bepress.com/ margaret_donohue/1

Dumbrigue, C., Moxley, D., & Najor-Durack, A. (2013). Keeping students in higher education: Successful practices and strategies for retention. New York, NY: Routledge.

Eber, L., Weist, M., & Barrett, S. (n.d.). An introduction to the interconnected systems framework. In S. Barrett, L. Eber, & M. West (Eds.), Advancing education effectiveness: Interconnecting school mental health and school-wide positive behavior support (pp. 3–17). [Monograph]. Retrieved from https://www.pbis.org/common/cms/files/Current%20Topics/Final-Monograph.pdf

Forman, S. G., & Crystal, C. D. (2015). Systems consultation for multitiered systems of supports (MTSS): Imple- mentation issues. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 25, 276–285.

doi:10.1080/10474412.2014.963226

Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., McCoach, D. B., Sugai, G. M., Lombardi, A., & Horner, R. (2015). An analysis of the relationship between implementation of school-wide positive behavior interventions and support and high school dropout rates. High School Journal, 98, 290–315.

Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., McCoach, D. B., Sugai, G. M., Lombardi, A., & Horner, R. (2016). Relationship

between school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports and academic, attendance, and

behavior outcomes in high schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18, 41–51.

Freeman, R., Miller, D., & Newcomer, L. (2015). Integration of academic and behavioral MTSS at the district level using implementation science. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 13, 59–72.

Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it?

Reading Research Quarterly, 41, 93–99. doi:10.1598/RRQ.41.1.4

Gibbons, K., & Coulter, W. (2016). Making response to intervention stick: Sustaining implementation past your retirement. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of response to inter-

vention: The science and practice of multi-tiered systems of support (2nd ed.; pp. 641–660). New York, NY: Springer.

Goodman-Scott, E. (2013). Maximizing school counselors’ efforts by implementing school-wide positive

behavioral interventions and supports: A case study from the field. Professional School Counseling, 17, 111–119.

Goodman-Scott, E. (2015). School counselors’ perceptions of their academic preparedness and job activities. Counselor Education and Supervision, 54, 57–67.

Goodman-Scott, E., Betters-Bubon, J., & Donohue, P. (2016). Aligning comprehensive school counseling pro-

grams and positive behavioral interventions and supports to maximize school counselors’ efforts.

Professional School Counseling, 19, 57–67.

Greenwood, C. R., Bradfield, T., Kaminski, R. A., Linas, M., Carta, J. J., & Nylander, D. (2011). The response to intervention (RTI) approach in early childhood. Focus on Exceptional Children, 43(9), 1–22.

Gysbers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2012). Developing & managing your school guidance & counseling programs (5th ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Horner, R. H., Sugai, G. M., & Anderson, C. M. (2010). Examining the evidence base for school-wide positive behavior support. Focus on Exceptional Children, 42(8), 1–14.

Horner, R. H., Sugai, G. M., & Lewis, T. (2015). Is school-wide positive behavior support an evidence-based practice? Retrieved from http://www.pbis.org/research

Howard, J. (2007). Curriculum development. Retrieved from http://www.pdx.edu/sites/www.pdx.edu.cae/files/

media_assets/Howard.pdf

Jacobs, H. H. (1997). Mapping the big picture: Integrating curriculum and assessment K-12. Alexandria, VA:

Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Johnsen, S. K., Parker, S. L., & Farah, Y. N. (2015). Providing services for students with gifts and talents within a Response-to-Intervention framework. Teaching Exceptional Children, 47, 226–233.

Jolivette, K., & Nelson, C. M. (2010). Adapting positive behavioral interventions and supports for secure juve- nile justice settings: Improving facility-wide behavior. Behavioral Disorders, 36, 28–42.

Kansas MTSS. (2011). Kansas multi-tier system of supports student improvement teams and the multi-tier system of supports. Retrieved from http://www.kansasmtss.org/pdf/briefs/SIT_and_MTSS.pdf

Klingner, J. K., & Edwards, P. A. (2006). Cultural considerations with response to intervention models. Reading Research Quarterly, 41, 108–117.

Kozleski, E. B., & Huber, J. J. (2010). Systemic change for RTI: Key shifts for practice. Theory Into Practice, 49, 258–264. doi:10.1080/00405841.2010.510696

Lemberger, M. E., Selig, J. P., Bowers, H., & Rogers, J. E. (2015). Effects of the Student Success Skills Program on

executive functioning skills, feelings of connectedness, and academic achievement in a predominantly Hispanic, low-income middle school district. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93, 25–37. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00178.x

Loyens, S. M. M., Jones, S. H., Mikkers, J., & van Gog, T. (2015). Problem-based learning as a facilitator of

conceptual change. Learning and Instruction, 38, 34–42.

Martens, K., & Andreen, K. (2013). School counselors’ involvement with a school-wide positive behavior support system: Addressing student behavior issues in a proactive and positive manner. Professional School Counseling, 16, 313–322. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2013-16.313

Martin, I., & Carey, J. C. (2014). Key findings and international implications of policy research on school coun-

seling models in the United States. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 4, 87–102.

Maynard, B. R., Kjellstrand, E. K., & Thompson, A. M. (2013). Effects of Check and Connect on attendance, behavior, and academics: A randomized effectiveness trial. Research on Social Work Practice, 24, 296–309. doi:10.1177/1049731513497804

McDaniel, S., Albritton, K., & Roach, A. (2013). Highlighting the need for further response to intervention research in general education. Research in Higher Education Journal, 20, 1–14. Retrieved from http:// jupapadoc.startlogic.com/manuscripts/131467.pdf

McIntosh, K., Filter, K. J., Bennett, J. L., Ryan, C., & Sugai, G. (2010). Principles of sustainable prevention: Designing scale-up of school-wide positive behavior support to promote durable systems. Psychology in the

Schools, 47, 5–21. doi:10.1002/pits.20448

Molloy, L. E., Moore, J. E., Trail, J., Van Epps, J. J., & Hopfer, S. (2013). Understanding real-world implementa-

tion quality and “active ingredients” of PBIS. Prevention Science, 14, 593–605.

National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. (2012). School counseling standards for school counselors of students ages 3–18+. Retrieved from http://boardcertifiedteachers.org/sites/default/files/ECYA-SC.pdf

Ockerman, M. S., Mason, E. C. M., & Hollenbeck, A. F. (2012). Integrating RTI with school counseling programs: Being a proactive professional school counselor. Journal of School Counseling, 10(15), 1–37. Retrieved from http://jsc.montana.edu/articles/v10n15.pdf

Ockerman, M. S., Patrikakou, E., & Feiker Hollenbeck, A. (2015). Preparation of school counselors and

response to intervention: A profession at the crossroads. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 7, 161–184. doi:10.7729/73.1106

Owen, J. (2012). The educational efficiency of employing a three-tier model of academic supports: Providing early, effective assistance to students who struggle. The International Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Change Management, 11(6), 95–106.

PBIS.org. (2016). Tier 1 case examples. Retrieved from https://www.pbis.org/school/primary-level/case-examples

Preston A. I., Wood, C. L, & Stecker, P. M. (2016). Response to intervention: Where it came from and where it’s going. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 60, 173–182.

Proctor, S. L., Graves, S. L., Jr., & Esch, R. C. (2012). Assessing African American students for specific learning disabilities: The promises and perils of Response to Intervention. Journal of Negro Education, 81, 268–282.

Ramsden, P. (2003). Learning to teach in higher education (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Reschly, A. L., & Cooloong-Chaffin, M. (2016). Contextual influences and response to intervention. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of multi-tiered systems of support (2nd ed.; pp. 441–453). New York, NY: Springer.

Ross, G. (n.d.). The community is McNabb Elementary. Retrieved from http://www.pbis.org/common/cms

/files/pbisresources/201_08_03_McNabbPBIS.pdf

Ryan, T., Kaffenberger, C. J, & Carroll, A. G. (2011). Response to intervention: An opportunity for school counselor leadership. Professional School Counseling, 14, 211–221.

Saeki, E., Jimerson, S. R., Earhart, J., Hart, S. R., Renshaw, T., Singh, R. D., & Stewart, K. (2011). Response to intervention (RTI) in the social, emotional, and behavioral domains: Current challenges and emerging possibilities. Contemporary School Psychology, 15, 43–52.

Sandomierski, T., Kincaid, D., & Algozzine, B. (2007). Response to Intervention and Positive Behavior Support: Broth- ers from different mothers or sisters with different misters? Retrieved from http://www.pbis.org/common/cms/ files/Newsletter/Volume4%20Issue2.pdf

Santos de Barona, M., & Barona, A. (2006). School counselors and school psychologists: Collaborating to ensure minority students receive appropriate consideration for special educational programs. Professional School Counseling, 10, 3–13.

Savery, J. R. (2006). Overview of problem-based learning: Definitions and distinctions. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 1. doi:10.7771/1541-5015.1002

Schmidt, J. J. (2014). Counseling in schools: Comprehensive programs of responsive services for all students (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Higher Education.

Schulte, A. C. (2016). Prevention and response to intervention: Past, present, and future. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of multi-tiered systems of support (2nd ed.; pp. 59–71). New York, NY: Springer.

Shepard, J. M., Shahidullah, J. D., & Carlson, J. S. (2013). Counseling students in levels 2 and 3: A PBIS/RTI guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin/Sage.

Sink, C. A. (2005). Contemporary school counseling: Theory, research, and practice. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin/ Cengage

Sink, C. A., Cooney, M., & Adkins, C. (in press). Conducting large-scale evaluation studies to identify charac- teristics of effective comprehensive school counseling programs. In J. C. Carey, B. Harris, S. M. Lee, & J. Mushaandja (Eds.), International handbook for policy research on school-based counseling. New York, NY: Springer.

Sprague, J. R., Scheuermann, B., Wang, E. W., Nelson, C. M., Jolivette, K., & Vincent, C. (2013). Adopting and adapting PBIS for secure juvenile justice settings: Lessons learned. Education and Treatment of Children, 36, 121–134.

Stanford University Center for Teaching and Learning. (2001). Problem-based learning. Speaking of Teaching, 11, 1–7.

Stoiber, K. C., & Gettinger, M. (2016). Multi-tiered systems of support and evidence-based practices. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of multi-tiered systems of support (2nd ed.; pp. 121–141). New York, NY: Springer.

Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Lewis, T. J., Nelsen C. M., . . . Turnbull, R. H. (2000). Applying positive behavior support and functional behavioral assessments in schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2(3), 131–143. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1031&context=gse_fac

Sugai, G., & Simonsen, B. (2012). Positive behavioral interventions and supports: History, defining features, and misconceptions. Center for PBIS & Center for Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, 1–8. Retrieved from http://idahotc.com/Portals/6/Docs/2015/Tier_1/articles/PBIS_history.features.miscon

ceptions.pdf

Turnbull, A., Bohanon, H., Griggs, P., Wickham, D., Salior, W., Freeman, R., . . . Warren, J. (2002). A blueprint for schoolwide positive behavior support: Implementation of three components. Exceptional Children, 68, 377–402. Retrieved from http://ecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1023&context=

education_facpubs

Turse, K. A., & Albrecht, S. F. (2015). The ABCs of RTI: An introduction to the building blocks of Response to Intervention. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 59(2), 83–89.

Warren, J. M., & Robinson, G. (2015). Addressing barriers to effective RTI through school counselor consulta- tion: A social justice approach. Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, 3(4), 1–27. Retrieved from http:// libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncp/f/Addressing%20Barriers%20to%20Effective%20RTI%20

through%20School%20Counselor%20Consultation.pdf

Wilkerson, K. A., Pérusse, R., & Hughes, A. (2013). Comprehensive school counseling programs and student achievement outcomes: A comparative analysis of RAMP versus non-RAMP schools. Professional School Counseling, 16, 172–184.

Zambrano, E., Castro-Villarreal, F., & Sullivan, J. (2012). School counselors and school psychologists: Partners in collaboration for student success within RTI and CDCGP frameworks. Journal of School Counseling, 10(24). Retrieved from http://jsc.montana.edu/articles/v10n24.pdf

Christopher A. Sink, NCC, is a Professor at Old Dominion University. Correspondence can be addressed to Christopher Sink, Darden College of Education, 5115 Hampton Blvd, Norfolk, VA 23529, csink@odu.edu.

Mar 24, 2016 | Article, Volume 6 - Issue 1

Chad M. Yates, Courtney M. Holmes, Jane C. Coe Smith, Tiffany Nielson

Implementing continuous feedback loops between clients and counselors has been found to have significant impact on the effectiveness of counseling (Shimokawa, Lambert, & Smart, 2010). Feedback informed treatment (FIT) systems are beneficial to counselors and clients as they provide clinicians with a wide array of client information such as which clients are plateauing in treatment, deteriorating or at risk for dropping out (Lambert, 2010; Lambert, Hansen, & Finch, 2001). Access to this type of information is imperative because counselors have been shown to have poor predictive validity in determining if clients are deteriorating during the counseling process (Hannan et al., 2005). Furthermore, recent efforts by researchers show that FIT systems based inside university counseling centers have beneficial training features that positively impact the professional development of counseling students (Reese, Norsworthy, & Rowlands, 2009; Yates, 2012). To date, however, few resources exist on how to infuse FIT systems into counselor education curriculum and training programs.

This article addresses the current lack of information regarding the implementation of a FIT system within counselor education curricula by discussing: (1) an overview and implementation of a FIT system; (2) a comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of three main FIT systems; (3) benefits that the use of FIT systems hold for counselors-in-training; and (4) how the infusion of FIT systems within a counseling curriculum can help assess student learning outcomes.

Overview and Implementation of a FIT System

FIT systems are continual assessment procedures that include weekly feedback about a client’s current symptomology and perceptions of the therapeutic process in relation to previous counseling session scores. These systems also can include other information such as self-reported suicidal ideation, reported substance use, or other specific responses (e.g., current rating of depressive symptomology). FIT systems compare clients’ current session scores to previous session scores and provide a recovery trajectory, often graphed, that can help counselors track the progress made through the course of treatment (Lambert, 2010). Some examples of a FIT system include the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2; Lambert et al., 1996), Session Rating Scale (SRS; Miller, Duncan, & Johnson, 2000), Outcome Rating Scale (ORS; Miller & Duncan, 2000), and the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS; Locke et al., 2011), all of which are described in this article.

Variety exists regarding how FIT systems are used within the counseling field. These variations include the selected measure or test, frequency of measurement, type of feedback given to counselors and whether or not feedback is shared with clients on a routine basis. Although some deviations exist, all feedback systems contain consistent procedures that are commonly employed when utilizing a system during practice (Lambert, Hansen, & Harmon, 2010). The first procedure in a FIT system includes the routine measurement of a client’s symptomology or distress during each session. This frequency of once-per-session is important as it allows counselors to receive direct, continuous feedback on how the client is progressing or regressing throughout treatment. Research has demonstrated that counselors who receive regular client feedback have clients that stay in treatment longer (Shimokawa et al., 2010); thus, the feedback loop provided by a FIT system is crucial in supporting clients through the therapeutic process.

The second procedure of a FIT system includes showcasing the results of the client’s symptomology or distress level in a concise and usable way. Counselors who treat several clients benefit from accessible and comprehensive feedback forms. This ease of access is important because counselors may be more likely to buy in to the use of feedback systems if they can use them in a time-effective manner.

The last procedure of FIT systems includes the adjustment of counseling approaches based upon the results of the feedback. Although research in this area is limited, some studies have observed that feedback systems do alter the progression of treatment. Lambert (2010) suggested that receiving feedback on what is working is apt to positively influence a counselor to continue these behaviors. Yates (2012) found that continuous feedback sets benchmarks of performance for both the client and the counselor, which slowly alters treatment approaches. If the goal of counseling is to decrease symptomology or increase functioning, frequently observing objective progress toward these goals using a FIT system can help increase the potential for clients to achieve these goals through targeted intervention.

Description of Three FIT Systems

Several well-validated, reliable, repeated feedback instruments exist. These instruments vary by length and scope of assessment, but all are engineered to deliver routine feedback to counselors regarding client progress. Below is a review of three of the most common FIT systems utilized in clinical practice.

The OQ Measures System

The OQ Measures System uses the Outcome Questionnaire 45.2 (OQ-45.2; Lambert et al., 1996), a popular symptomology measure that gauges a client’s current distress levels over three domains: symptomatic distress, interpersonal relations and social roles. Hatfield and Ogles (2004) listed the OQ 45.2 as the third most frequently used self-report outcome measure for adults in the United States. The OQ 45.2 has 45 items and is rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores range between 0 and 180; higher scores suggest higher rates of disturbance. The OQ 45.2 takes approximately 5–6 minutes to complete and the results are analyzed using the OQ Analyst software provided by the test developers. The OQ 45.2 can be delivered by paper and pencil versions or computer assisted administration via laptop, kiosk, or personal digital assistant (PDA). Electronic administration of the OQ 45.2 allows for seamless administration, scoring and feedback to both counselor and client.

Internal consistency for the OQ 45.2 is α = 0.93 and test-retest reliability is r = 0.84. The OQ 45.2 demonstrated convergent validity with the General Severity Index (GSI) of the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 1983; r = .78, n = 115). The Outcome Questionnaire System has five additional outcome measures: (1) the Outcome Questionnaire 30 (OQ-30); (2) the Severe Outcome Questionnaire (SOQ), which captures outcome data for more severe presenting concerns, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia; (3) the Youth Outcome Questionnaire (YOQ), which assesses outcomes in children between 13 and 18 years of age; (4) the Youth Outcome Questionnaire 30, which is a brief version of the full YOQ; and (5) the Outcome Questionnaire 10 (OQ-10), which is used as a brief screening instrument for psychological symptoms (Lambert et al., 2010).

The Partners for Change Outcome Management System (PCOMS)

The Partners for Change Outcome Management System (PCOMS) uses two instruments, the Outcome Rating Scale (ORS; Miller & Duncan, 2000) that measures the client’s session outcome, and the Session Rating Scale (SRS; Miller et al., 2000) that measures the client’s perception of the therapeutic alliance. The ORS and SRS were designed to be brief in response to the heavy time demands placed upon counselors. Administration of the ORS includes handing the client a copy of the ORS on a sheet of letter sized paper; the client then draws a hash mark on four distinct 10-centimeter lines that indicate how he or she felt over the last week on the following scales: individually (personal well-being), interpersonally (family and close relationships), socially (work, school and friendships), and overall (general sense of well-being).

The administration of the SRS includes four similar 10-centimeter lines that evaluate the relationship between the client and counselor. The four lines represent relationship, goals and topics, approach or methods, and overall (the sense that the session went all right for me today; Miller et al., 2000). Scoring of both instruments includes measuring the location of the client’s hash mark and assigning a numerical value based on its location along the 10-centimeter line. Measurement flows from left to right, indicating higher-level responses the further right the hash mark is placed. A total score is computed by adding each subscale together. Total scores are graphed along a line plot. Miller and Duncan (2000) used the reliable change index formula (RCI) to establish a clinical cut-off score of 25 and a reliable change index score of 5 points for the ORS. The SRS has a cut-off score of 36, which suggests that total scores below 36 indicate ruptures in the working alliance.

The ORS demonstrated strong internal reliability estimates (α = 0.87-.096), a test-retest score of r = 0.60, and moderate convergent validity with measures like the OQ 45.2 (r = 0.59), which it was created to resemble (Miller & Duncan, 2000; Miller, Duncan, Brown, Sparks, & Claud, 2003). The SRS had an internal reliability estimate of α = 0.88, test-retest reliability of r = 0.74, and showed convergent validity when correlated with similar measures of the working alliance such as the Helping Alliance Questionnaire–II (HAQ–II; Duncan et al., 2003; Luborsky et al., 1996). The developers of the ORS and SRS have also created Web-based administration features that allow clients to use both instruments online using a pointer instead of a pencil or pen. The Web-based administration also calculates the totals for the instruments and graphs them.

The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS)

The CCAPS was designed as a semi-brief continuous measure that assesses symptomology unique to college-aged adults (Locke et al., 2011). When developed, the CCAPS was designed to be effective in assessing college students’ concerns across a diverse range of college campuses. The CCAPS has two separate versions, the CCAPS-62 and a shorter version, the CCAPS-34. The CCAPS-62 has 62 test items across eight subscales that measure: depression, generalized anxiety, social anxiety, academic distress, eating concerns, family distress, hostility and substance abuse. The CCAPS-34 has 34 test items across seven of the scales found on the CCAPS-62, excluding family distress. Additionally, the substance use scale on the CCAPS-62 is renamed the Alcohol Use Scale on the CCAPS-32 (Locke et al., 2011). Clients respond on a 5-point Likert scale with responses that range from not at all like me to extremely like me. On both measures clients are instructed to answer each question based upon their functioning over the last 2 weeks. The CCAPS measures include a total score scale titled the Distress Index that measures the amount of general distress experienced over the previous 2 weeks (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2012). The measures were designed so that repeated administration would allow counselors to compare each session’s scores to previous scores, and to a large norm group (N = 59,606) of clients completing the CCAPS at university counseling centers across the United States (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2012).

The CCAPS norming works by comparing clients’ scores to a percentile score of other clients who have taken the measure. For instance, a client’s score of 80 on the depressive symptoms scale indicates that he or she falls within the 80th percentile of the norm population’s depressive symptoms score range. Because the CCAPS measures utilize such a large norm base, the developers have integrated the instruments into the Titanium Schedule ™, an Electronic Medical Records (EMR) system. The developers also offer the instruments for use in an Excel scoring format, along with other counseling scheduling software programs. The developers of the CCAPS use RCI formulas to provide upward and downward arrows next to the reported score on each scale. Downward arrows indicate the client’s current score is significantly different than previous sessions’ scores and suggests progress during counseling. An upward arrow would suggest a worsening of symptomology. Cut-off scores vary across scales and can be referenced in the CCAPS 2012 Technical Manual (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2012).

Test-retest estimates at 2 weeks for the CCAPS-62 and CCAPS-34 scales range between r = 0.75–0.91 (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2012). The CCAPS-34 also demonstrated a good internal consistency that ranged between α = 0.76–0.89 (Locke et al., 2012). The measures also demonstrated adequate convergent validity compared to similar measures. A full illustration of the measures’ convergent validity can be found in the CCAPS 2012 Technical Manual (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2012).

Benefits for Counselors-in-Training

The benefits of FIT systems are multifaceted and can positively impact the growth and development of student counselors (Reese, Norsworthy, et al., 2009; Schmidt, 2014; Yates, 2012). Within counselor training laboratories, feedback systems have shown promise in facilitating the growth and development of beginning counselors (Reese, Usher, et al., 2009), and the incorporation of FIT systems into supervision and training experiences has been widely supported (Schmidt, 2014; Worthen & Lambert, 2007; Yates, 2012).

One such benefit is that counseling students’ self-efficacy improved when they saw evidence of their clients’ improvement (Reese, Usher, et al., 2009). A FIT system allows for the documentation of a client’s progress and when counseling students observed their clients making such progress, their self-efficacy improved regarding their skill and ability as counselors. Additionally, the FIT system allowed the counselor trainees to observe their effectiveness during session, and more importantly, helped them alter their interventions when clients deteriorated or plateaued during treatment. Counselor education practicum students who implemented a FIT system through client treatment reported that having weekly observations of their client’s progress helped them to isolate effective and non-effective techniques they had used during session (Yates, 2012). Additionally, practicum counseling students have indicated several components of FIT feedback forms were useful, including the visual orientation (e.g., graphs) to clients’ shifts in symptomology. This visual attenuation to client change allowed counselors-in-training to be more alert to how clients are actually faring in between sessions and how they could tailor their approach, particularly regarding crisis situations (Yates, 2012).

Another benefit discovered from the above study was that counseling students felt as if consistent use of a FIT system lowered their anxiety and relieved some uncertainty regarding their work with clients (Yates, 2012). It is developmentally appropriate for beginning counselors to struggle with low tolerance for ambiguity and the need for a highly structured learning environment when they begin their experiential practicums and internships (Bernard & Goodyear, 2013). The FIT system allows for a structured format to use within the counseling session that helps to ease new counselors’ anxiety and discomfort with ambiguity.

Additionally, by bringing the weekly feedback into counseling sessions, practicum students were able to clarify instances when the feedback was discrepant from how the client presented during session (Yates, 2012). This discrepancy between what the client reported on the measure and how they presented in session was often fertile ground for discussion. Counseling students believed bringing these discrepancies to a client’s attention deepened the therapeutic alliance because the counselor was taking time to fully understand the client (Yates, 2012).

Several positive benefits are added to the clinical supervision of counseling students. One such benefit is that clinical supervisors found weekly objective reports of their supervisees helpful in providing evidence of a client’s progress during session that was not solely based upon their supervisees’ self-report. This is crucial because relying on self-report as a sole method of supervision can be an insufficient way to gain information about the complexities of the therapeutic process (Bernard & Goodyear, 2013). Supervisors and practicum students both reported that the FIT system frequently brought to their attention potential concerns with clients that they had missed (Yates, 2012). A final benefit is that supervisees who utilized a FIT system during supervision had significantly higher satisfaction levels of supervision and stronger supervisory alliances than students who did not utilize a FIT system (Grossl, Reese, Norsworthy, & Hopkins, 2014; Reese, Usher, et al., 2009).

Benefits for Clients

Several benefits exist for counseling clients when FIT systems are utilized in the therapeutic process. The sharing of objective progress information with clients has been found to be perceived as helpful and a generally positive experience by clients (Martin, Hess, Ain, Nelson, & Locke, 2012). Surveying clients using a FIT system, Martin et al. (2012) found that 74.5% of clients found it “convenient” to complete the instrument during each session. Approximately 46% of the clients endorsed that they had a “somewhat positive” experience using the feedback system, while 20% of clients reported a “very positive” experience. Hawkins, Lambert, Vermeersch, Slade, and Tuttle (2004) found that providing feedback to both clients and counselors significantly increased the clients’ therapeutic improvement in the counseling process when compared to counselors who received feedback independently. A meta-analysis of several research studies, including Hawkins et al. (2004), found effect sizes of clinical efficacy related to providing per-session feedback ranged from 0.34 to 0.92 (Shimokawa et al., 2010). These investigations found more substantial improvement in clients whose counselors received consistent client feedback when compared with counselors who received no client feedback regarding the therapeutic process and symptomology. These data also showed that consistent feedback provision to clients resulted in an overall prevention of premature treatment termination (Lambert, 2010).

Utilization of FIT Systems for Counseling Curriculum and Student Learning Outcome Assessment

The formal assessment of graduate counseling student learning has increased over the past decade. The most recent update of the national standards from the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) included the requirement for all accredited programs to systematically track students at multiple points with multiple measures of student learning (CACREP, 2015, Section 4, A, B, C, D, E). Specifically, “counselor education programs conduct formative and summative evaluations of the student’s counseling performance and ability to integrate and apply knowledge throughout the practicum and internship” (CACREP, 2015, Section 4.E). The use of continuous client feedback within counselor education is one way to address such assessment requirements (Schmidt, 2014).