Aug 10, 2022 | Author Videos, Volume 12 - Issue 2

Dan Li

Supervisee development is integral to counselor training. Despite the general acknowledgement that supervisors adopt different styles when supervising counselor trainees at varying levels, there is a paucity of studies that (a) measure supervisee levels using reliable and valid psychometric instruments, other than a broad categorization of supervisees based on their training progression (e.g., master’s level vs. doctoral level, practicum vs. internship, counselor trainee vs. postgraduate); and (b) empirically document how the matching of supervisory styles and supervisee levels relates to supervision processes and/or outcomes. The supervisory working alliance is key to the supervision process and outcome. To test the hypothesized moderation effects of supervisee levels on the relationship between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance, the author performed a series (n = 16) of moderation analyses with a sample (N = 113) of master’s- and doctoral-level counseling trainees and practitioners. Results suggested that supervisee levels and their three indicators (self and other awareness, motivation, and autonomy) were statistically significant moderators under different contexts. These findings (a) revealed extra intricacies of the relationships among the study variables, (b) shed light on future research directions concerning supervisee development, and (c) encouraged supervisors to adopt a composite of styles to varying degrees to better foster supervisee growth.

Keywords: supervisee development, supervisory styles, supervisory working alliance, supervisee levels, moderation analyses

Clinical supervision is integral to promoting counseling supervisees’ learning (Goodyear, 2014), safeguarding the quality of professional services offered to supervisees’ clients, and gatekeeping the counseling profession (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019). Because supervisors and supervisees are two parties of the tripartite entity of supervision, literature has extensively documented supervisor characteristics (e.g., supervisory styles, self-disclosure, cultural humility), supervisee characteristics (e.g., professional development levels), and the relationship between the two (e.g., supervisory working alliance) as related to supervision processes and outcomes (King et al., 2020; Ladany, Walker, & Melincoff, 2001; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010).

Of these relationships, research has consistently revealed a positive correlation between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance (Efstation et al., 1990; Heppner & Handley, 1981; Ladany & Lehrman-Waterman, 1999; Ladany, Walker, & Melincoff, 2001). Although such direct positive correlation is theoretically appealing and statistically compelling, there is limited research that further investigates the intricacy of this association, if at all (e.g., whether the direction or strength of this relationship may alter in different contexts). Particularly, abundant supervision literature (Friedlander & Ward, 1984; Li et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019; Li, Duys, & Granello, 2020; Li, Duys, & Vispoel, 2020; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010) suggested the adoption of different supervision approaches when working with supervisees at various levels of professional development. Therefore, supervisee levels present as a potential context to examine how supervisory styles relate to the supervisory working alliance.

However, supervisee levels are frequently conceptualized based on supervisees’ training progression (e.g., master’s level vs. doctoral level, practicum vs. internship, counselor trainee vs. postgraduate), which may not accurately approximate where supervisees are. As such, I adopted the Supervisee Levels Questionnaire-Revised (SLQ-R; McNeill et al., 1992), a reliable and valid psychometric instrument, to measure supervisee levels (collectively as an overall assessment and separately with their three indicators) in this study.

Supervisory Styles

Supervisory styles embody a constellation of behavior patterns that supervisors exhibit in establishing a working relationship with supervisees (Hunt, 1971) and are related to the interactional pattern that is fostered by supervisors in a direct or indirect manner (Munson, 1993). Specifically, supervisory styles encompass supervisors’ consistent focus in supervision, the manner in articulating their theoretical orientation, as well as the philosophy of practice and supervision and how it is communicated to supervisees (Munson, 1993). Friedlander and Ward (1984) identified three distinctive factors that correspond to three supervisory styles—attractive, interpersonally sensitive, and task-oriented—as measured by the Supervisory Styles Inventory (SSI) used in the present study. Attractive style supervisors appear to be warm, supportive, friendly, open, and flexible, denoting the collegial dimension of supervision; the interpersonally sensitive style is a relationship-oriented approach, and supervisors of this style tend to be invested, committed, therapeutic, and perceptive; and task-oriented supervisors are content-focused, goal-oriented, thorough, focused, practical, and structured (Friedlander & Ward, 1984). These styles resonate with the consultant, counselor, and teacher roles of the supervisor, respectively, in Bernard’s (1997) discrimination model.

Of the three styles, the interpersonally sensitive and task-oriented styles appear to be empirically distinct from one another and distinct from the attractive style (Shaffer & Friedlander, 2017). For instance, Li, Duys, and Vispoel (2020) studied 34 supervisory dyads and found the interpersonally sensitive style was the only discriminant variable, based on which supervisory dyads exhibited statistically different state-transitional patterns (i.e., movement patterns across six common supervision states). Earlier, Fernando and Hulse-Killacky (2005) also found this same style was the only predictor that uniquely and significantly explained supervisees’ satisfaction with supervision, but the task-oriented style was the only significant predictor in explaining supervisees’ perceived self-efficacy.

Supervisory Working Alliance

Park et al.’s (2019) meta-analysis indicated that the supervisory working alliance was positively related to supervision outcome variables. Bordin (1983) first coined the concept of the supervisory working alliance as a parallel concept to the therapeutic working alliance and introduced the three aspects of the therapeutic working alliance to the alliance in supervision—mutual agreements on the goals, tasks, and bond—which laid the foundation for the adapted Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Bahrick, 1989) for both supervisors and supervisees. Efstation et al. (1990) instead used three supervisor factors (client focus, rapport, and identification) and two supervisee factors (rapport and client focus) to conceptualize the supervisory working alliance in their Supervisory Working Alliance Inventory (SWAI). In view of the collinearity issue for the goal and task dimensions in the WAI (Hatcher et al., 2020), I adopted the SWAI in the present study.

The working alliance is one of the most robust predictors of outcome in psychotherapy (Norcross, 2011). Although such robust prediction cannot be directly replicated in supervision between the supervisory working alliance and supervision outcome (Goodyear, 2014), scholars (DePue et al., 2016; DePue et al., 2022) have found the supervisory working alliance to be related to the therapeutic working alliance. Specifically, supervisees’ perception of the supervisory working alliance was positively related to their perception of the therapeutic alliance (DePue et al., 2016). However, supervisees’ perception of the supervisory working alliance did not significantly contribute to clients’ perception of the therapeutic working alliance (DePue et al., 2016).

Supervisory Styles and the Supervisory Working Alliance

Extensive research has documented a close relationship between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance (Efstation et al., 1990; Heppner & Handley, 1981; Ladany, Walker, & Melincoff, 2001; Shaffer & Friedlander, 2017). Broadly, as supervisees perceived a greater mixture of supervisory styles in their supervisors (i.e., higher ratings on all three styles; Ladany, Marotta, & Muse-Burke, 2001), supervisees were more likely to report a stronger supervisory working alliance (Li et al., 2021). Despite this global positive correlation, when scholars examined each style independently in relation to each dimension of the supervisory working alliance, such statistical significance was not consistent (Ladany, Walker, & Melincoff, 2001). For instance, in Ladany, Walker, and Melincoff’s (2001) study, participants’ perceptions of an attractive style uniquely and significantly accounted for their perceptions of the bond dimension in alliance, whereas both the interpersonally sensitive and task-oriented styles had this unique and significant association with the task dimension in alliance.

The Moderating Role of Supervisee Levels

It is not uncommon for a counselor supervisor to start supervision with an expectation of a supervisory style to use (Hart & Nance, 2003). But supervisors have to decide what to address with the supervisee and adopt the most functional style (Bernard, 1997), which could be subject to a myriad of factors, such as contextual factors (Holloway, 1995), cultural considerations (Li et al., 2018), and supervisees’ developmental levels and needs (Friedlander & Ward, 1984; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010), among others. Particularly, in Friedlander and Ward’s (1984) study, supervisory styles were differentially related to supervisees’ experience levels. For example, supervisors reported that they were more task-oriented with practicum students but more attractive and interpersonally sensitive with internship students. This interaction effect was also echoed by practicum students’ higher ratings on the task-oriented style but lower ratings on the interpersonally sensitive style, compared to their internship counterparts (Friedlander & Ward, 1984). Similarly, in the study conducted by Li, Duys, and Granello (2020), supervisory dyads with less experienced supervisees tended to be more preoccupied with foundational competencies (e.g., counseling skills and theories, maintenance of standards of service) than dyads with more experienced supervisees. Consistently, more experienced supervisees in Li et al.’s (2019) study were more likely to display positive social emotional behaviors (e.g., self-disclosure, empathy, reflection of feelings, expanding on supervisors’ ideas, praise) in response to supervisors’ opinions, which in turn were more likely to elicit supervisors’ opinions that helped facilitate supervisees’ growth.

However, supervisees’ developmental levels were not always significantly associated with supervision processes or outcomes. For instance, in Bucky et al.’s (2010) study, doctoral-level supervisees did not rate their supervisor characteristics as related to the supervisory working alliance differently based on their developmental levels. Nevertheless, researchers in that study (Bucky et al., 2010) gauged supervisees’ developmental levels based on supervisees’ training progression (i.e., the current level or year level) as commonly practiced (e.g., practicum vs. internship), which may not accurately capture the actual developmental levels of supervisees. Or supervisee levels may not be strikingly distinct in doctoral programs, at least in that sample. In this study, supervisee levels were conceptualized not only as an overall assessment of where supervisees are but with three dimensions (self and other awareness, motivation, and autonomy) aligned with Stoltenberg and McNeill’s (2010) integrative developmental model (IDM) using the Supervisee Levels Questionnaire-Revised (SLQ-R; McNeill et al., 1992).

Statement of Purpose

Although literature evidenced the overall positive correlation between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance, the direction and strength of such a relationship in different contexts warrants additional attention. Particularly, supervisees’ developmental progression entails a flexible mixture of different supervisory styles as suggested theoretically and empirically, but whether and how the relationship between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance may vary across different supervisee levels calls for further investigation. To this end, the purpose of the current study was to test the potential moderation effects of supervisee levels on the relationship between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance.

Given that supervisees at earlier stages of professional development may need more guidance and support from supervisors, which necessitates a variety of supervision styles that are critical to their perception of the working alliance with their supervisors, I hypothesized that the positive relationship between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance would be more sensitive for supervisees at earlier stages of development, compared to their more experienced counterparts. In other words, the positive relationship would be stronger for supervisees at lower levels of professional development and weaker for supervisees at higher levels of professional development.

Method

Participants

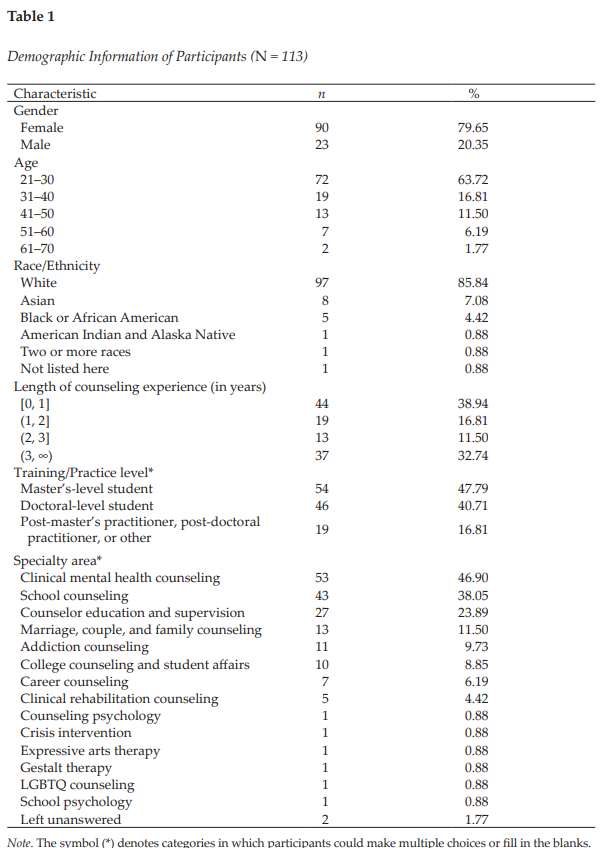

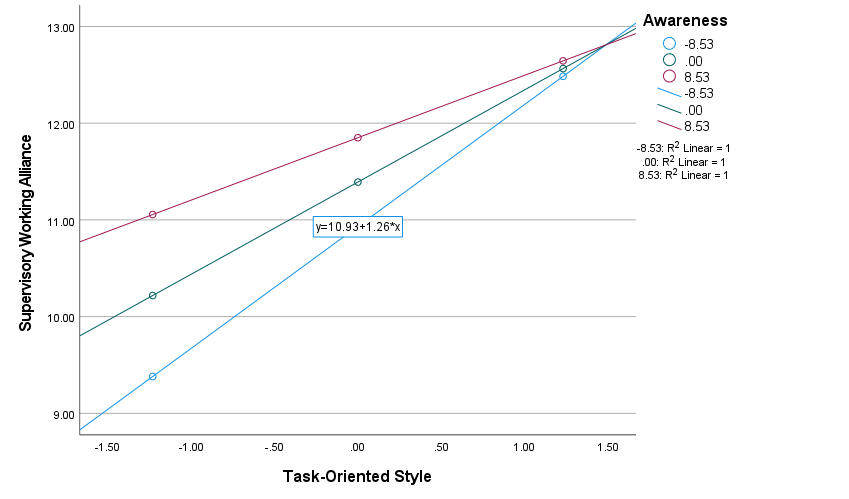

The data set of this study is part of a larger national quantitative study with a cross-sectional sample (Li et al., 2021). Yet, researchers have not examined supervisee levels that are crucial to measuring supervisee development using a robust psychometric instrument. The current sample comprised 113 participants (see Table 1), with the majority as master’s-level (n = 54, 47.79%) or doctoral-level students (n = 46, 40.71%). Approximately 17% of participants (n = 19) identified themselves as post-master’s or post-doctoral practitioners or other. Some participants reported both their training and practicing levels (e.g., both as a doctoral student and a post-master’s practitioner), which caused the sample size to be larger than 113 if simply adding the frequencies across the three categories together. Most participants reported their specialty areas in clinical mental health counseling (n = 53, 46.90%), school counseling (n = 43, 38.05%), and counselor education and supervision (n = 27, 23.89%). Because some participants indicated more than one specialty area, the total percentage did not add up to 100.

In this sample, approximately 80% were female (n = 90) and 23 were male (20.35%). At the time of filling out the questionnaire, most of them fell in the 21–30 age range (n = 72, 63.72%), with 19 in the 31–40 range (16.81%), 13 in the 41–50 range (11.50%), and nine beyond 50 years old (7.96%). Participants in this sample predominantly identified themselves as White (n = 97; 85.84%), with eight as Asian (7.08%), five as Black or African American (4.42%), one as American Indian and Alaska Native (0.88%), one as biracial or multiracial (0.88%), and one indicating other (0.88%). Most participants reported their counseling experience as 1 year or less (n = 44, 38.94%) or longer than 3 years (n = 37; 32.74%), with the rest reporting in between (n = 32, 28.31%). See Table 1 for more detailed demographic information.

Procedure

Upon receiving IRB approval, I started collecting data online through Qualtrics in 2017–2018. The recruitment criteria included (a) one is at least 18 years of age by the time of filling out the survey; and (b) one is a student or a practitioner who had supervision experience in the counseling field. I disseminated the recruitment post through several professional networks, including the Counselor Education and Supervision Network-Listserv (CESNET-L) and American Counseling Association (ACA) Connect. In addition to this convenience sampling, I also used snowball sampling because participants were encouraged to share the recruitment post with anyone who they thought might be eligible to participate in the study. The recruitment post contained a survey link that directed potential participants to the informed consent webpage and then a compiled questionnaire webpage.

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire

The purpose of including this self-constructed Demographic Questionnaire was to report the basic demographic information of participants. Specifically, the questionnaire included the gender, age, race/ethnicity, length of counseling-related work experience, training/practicing level, and training or specialty area of participants.

Supervisory Styles Inventory

The SSI (Friedlander & Ward, 1984) is a 33-item instrument used to measure the degree to which one endorses descriptors representative of each of the three dimensions of supervisory style: Attractive (7 items), Interpersonally Sensitive (8 items), and Task-Oriented (10 items), with the remainder as the filler items (8 items). Participants rate each item along a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (not very) to 7 (very). Higher scores in each dimension mean that one endorses descriptors of a certain supervisory style to a larger extent. Sample items for the Attractive, Interpersonally Sensitive, and Task-Oriented subscales are “supportive,” “perceptive,” and “didactic,” respectively.

Friedlander and Ward (1984) reported the Cronbach’s alphas of the three subscales separately and combined ranged from .76 to .93 (Ns ranging from 105 to 202). Additionally, the item–scale correlations ranged from .70 to .88 for the Attractive subscale, from .51 to .82 for the Interpersonally Sensitive style, and from .38 to .76 for the Task-Oriented scale (N1 = 202, N2 = 183; Friedlander & Ward, 1984). The test-retest reliability (N = 32) for the combined scale was .92; they were .94, .91, and .78 for the Attractive, Interpersonally Sensitive, and Task-Oriented subscales, respectively (Friedlander & Ward, 1984). They also reported the convergent validity based on moderate to high positive relationships (ps < .001) between the SSI and Stenack and Dye’s (1982) measure of supervisor roles (i.e., consultant, counselor, and teacher; N = 90). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was .96 for the Attractive style, .94 for the Interpersonally Sensitive style, .92 for the Task-Oriented style, and .96 for the entire measure.

Supervisory Working Alliance Inventory

The SWAI (Efstation et al., 1990) is used to measure the relationship in counselor supervision. It has both the supervisor and supervisee forms. The supervisee form applied to the current study includes two scales: Rapport (12 items) and Client Focus (7 items). Supervisees indicate the extent to which the behavior described in each item seems characteristic of their work with their supervisors on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 being almost never and 7 being almost always. Higher scores in the Rapport scale indicate a stronger perceived rapport with their supervisor, and higher scores in the Client Focus scale suggest more attention to issues related to the client in supervision. A sample item for the Rapport scale is “I feel free to mention to my supervisor any troublesome feelings I might have about him/her.” A sample item for the Client Focus scale is “I work with my supervisor on specific goals in the supervisory session.”

Efstation et al. (1990) reported that the alpha coefficient was .90 for Rapport and .77 for Client Focus (N = 178) for the supervisee form. Moreover, the item–scale correlations ranged from .44 to .77 for Rapport, and from .37 to .53 for Client Focus. They used the SSI to obtain initial estimates of convergent and divergent validity for the SWAI (Efstation et al., 1990). As expected, the Client Focus dimension of the SWAI showed moderate correlation (r = .52) with the Task-Oriented style in the SSI supervisee’s form, but low correlation (r = .04) with the Attractive style and low correlation (r = .21) with the Interpersonally Sensitive style. The Rapport dimension from the SWAI had low correlation (r < .00) with the Task-Oriented style of the SSI. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was .95 for Rapport, .90 for Client Focus, and .96 for the entire scale.

Supervisee Levels Questionnaire-Revised

The Supervisee Levels Questionnaire-Revised (SLQ-R; McNeill et al., 1992) is used to measure supervisees’ developmental levels (Stoltenberg & Delworth, 1987). It has 30 items developed around three dimensions: Self and Other Awareness (12 items), Motivation (8 items), and Dependency-Autonomy (10 items). Supervisees can indicate their current behavior along a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 representing never, 2 rarely, 3 sometimes, 4 half the time, 5 often, 6 most of the time, and 7 always. Higher scores (after reverse-scoring for some of the items) in these dimensions reflect higher levels of supervisee development in Self and Other Awareness, Motivation, and Autonomy, respectively. A sample item for the Self and Other Awareness dimension is “I feel genuinely relaxed and comfortable in my counseling/therapy sessions”; a sample item (reverse-scoring) for the Motivation dimension is “The overall quality of my work fluctuates; on some days I do well, on other days, I do poorly”; and a sample item for the Dependency-Autonomy dimension is “I am able to critique counseling tapes and gain insights with minimum help from my supervisor.”

McNeill et al. (1992) reported that the Cronbach alpha coefficients of the SLQ-R (N = 105) were .83, .74, and .64 for the three subscales, respectively, and .88 for the total scores. To assess the construct validity of the SLQ-R, they examined the differences in subscale and total scores across the beginning, intermediate, and advanced groups. Hotelling’s test of significance indicated that the three groups differed significantly both on the total SLQ-R scores, F(2, 102) = 7.37, p < .001, and on a linear combination of SLQ-R subscale scores, F(6, 198) = 2.45, p < .026. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was .89 for Self and Other Awareness, .85 for Motivation, .57 for Autonomy, and .91 for the entire measure.

Data Analysis

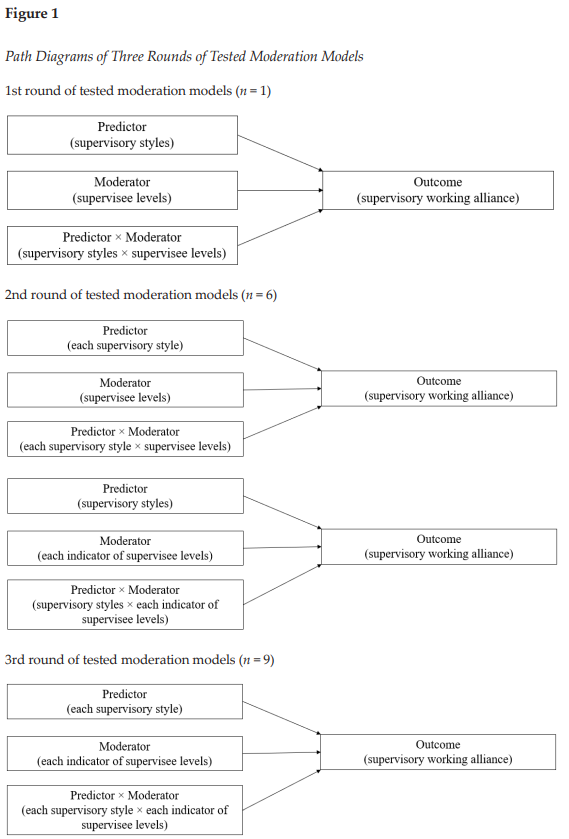

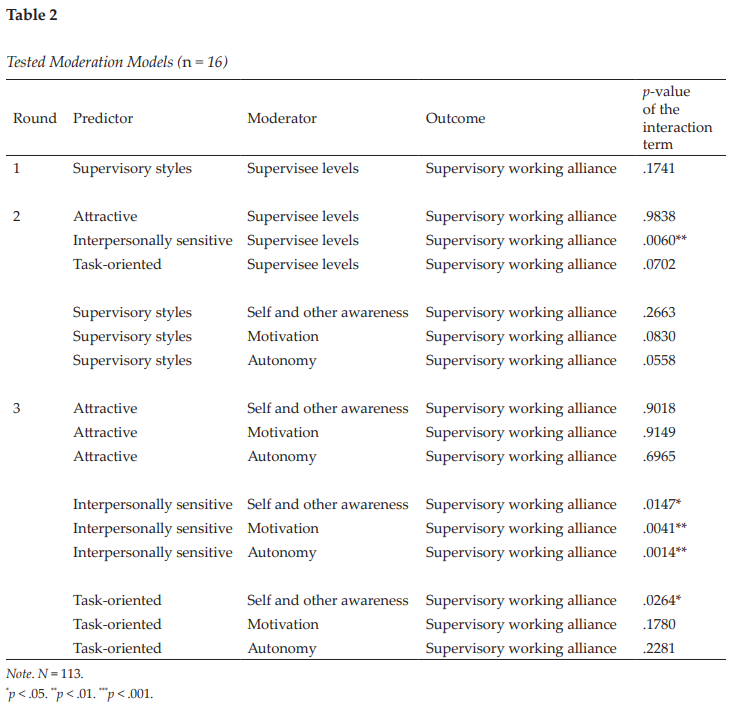

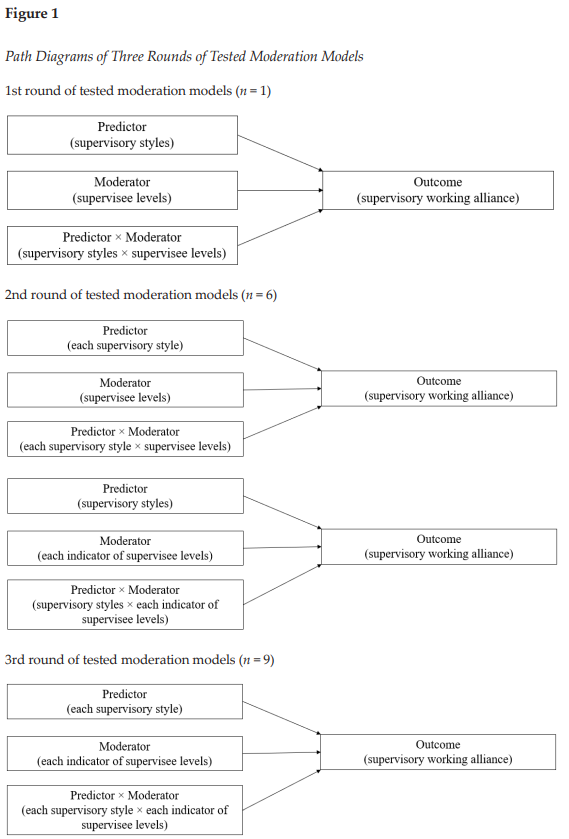

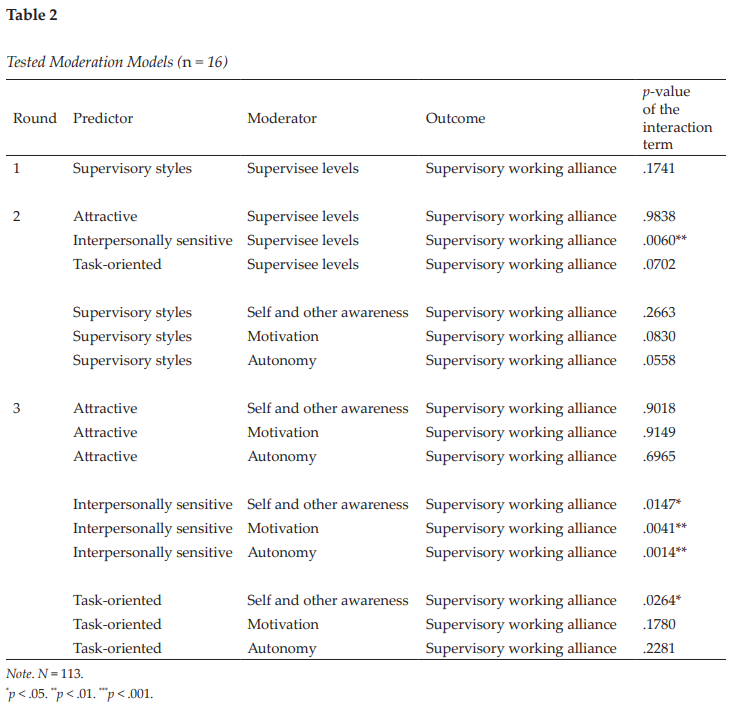

To thoroughly test the potential moderation effects of supervisee levels on the relationship between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance, I carried out three rounds of moderation analysis in which the supervisory working alliance was always the outcome variable. In the first round (n = 1), supervisory styles as a whole were the predictor, and supervisee levels as a whole were the moderator. The second round (n = 6) involved two series of analyses. In the first series (n = 3), each supervisory style was the predictor, and supervisee levels as a whole were the moderator. In the second series (n = 3), supervisory styles as a whole were the predictor, and each indicator of supervisee levels was the moderator. In the third round (n = 9), each supervisory style was the predictor, and each indicator of supervisee levels was the moderator. Figure 1 presents path diagrams of three rounds of tests and Table 2 lists all tested models (n = 16).

I followed up each significant moderation effect (n = 5) with a simple slopes analysis (Aiken & West, 1991) to interpret the nature of the interaction effect. The PROCESS v4.0 tool in SPSS was employed to perform all these analyses. A total of 166 potential participants accessed the survey, but only 113 of them completed all the study instruments (SSI, SWAI, and SLQ-R) in the present study. To alleviate the impact of significantly incomplete responses, I removed the 53 respondents who left at least one instrument unanswered. The a priori power analysis via G*Power 3.1.9.7 indicated that the minimum sample size would be 55 to detect an interaction effect with a medium effect size (f 2 = .15), given the desired statistical power level of .80 and type I error rate of .05. As such, the ultimate sample size of 113 meets this requirement.

I made the linearity and homoscedasticity assumptions using the zpred vs. zresid plot, which did not show a systematic relationship between the predicted values and the errors in the model (Field, 2017). Provided that participants independently filled out the study survey, I held the assumption of independence that the errors in the model were not dependent on each other. Further screening detected 12 missing values scattered across the three scales, which accounted for 0.13% of the entire 9,266 possible values. To determine the nature of these missing values, I performed the Little’s test (1988), and the results signified that these values were missing completely at random (MCAR; χ2 = 884.185, df = 890, p = .549). Because multiple imputation (MI; Schafer, 1999) can provide unbiased and valid estimates of associations based on information from the available data and can handle MCAR (Pedersen et al., 2017), I adopted MI to replace the missing values before performing further analyses in this study.

Results

Results of this study in part supported my broad hypothesis that the positive relationship between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance would be more sensitive for supervisees at earlier stages of development, compared to their more experienced counterparts. Examining each supervisory style and each indicator of supervisee levels independently revealed the intricacy of the relationship between the two constructs.

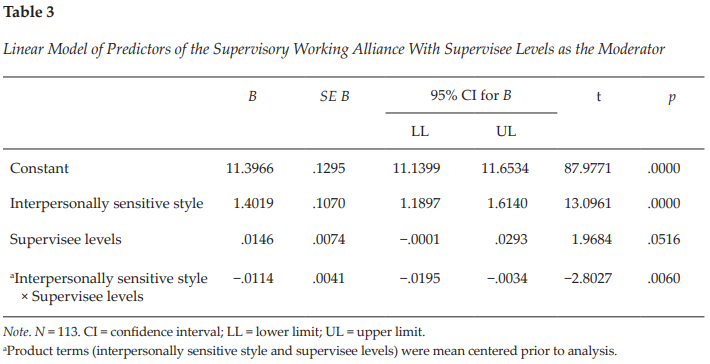

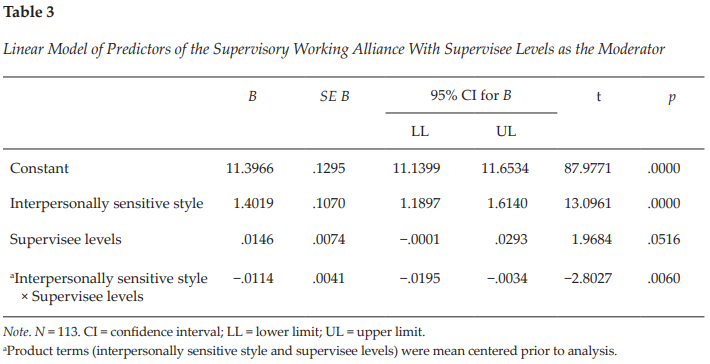

There were two groups of major findings. First, supervisee levels as a whole were a significant moderator between the interpersonally sensitive style and the supervisory working alliance according to supervisees’ perceptions, ΔR2 = .0272, F(1, 109) = 7.8551, p = .006, with a small to medium effect size

(f 2 = .07; Lorah & Wong, 2018). Specifically, the strength of the relationship between the interpersonally sensitive style and the supervisory working alliance differed based on supervisee levels (see Table 3).

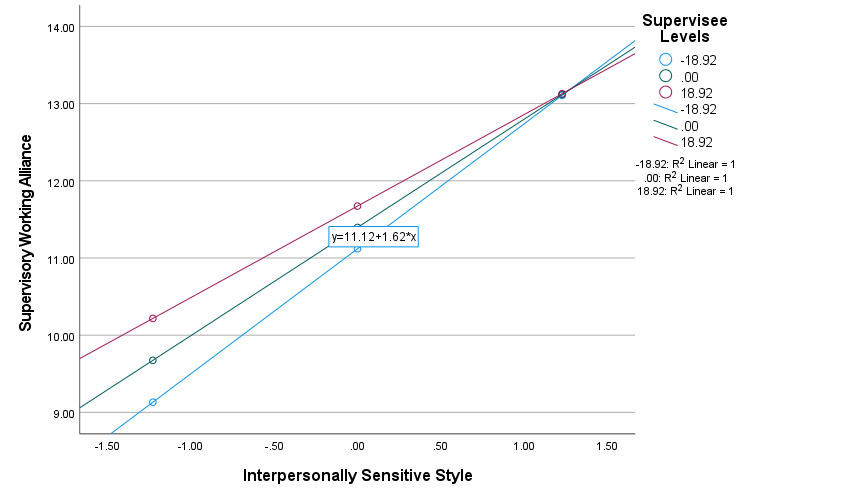

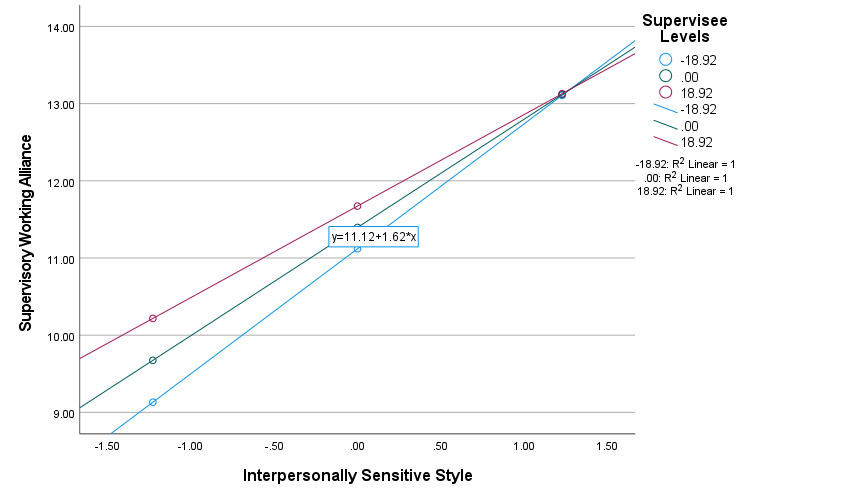

In view of this significant moderation effect, I conducted a simple slopes analysis as a follow-up, which indicated that the simple slopes for 1 standard deviation (SD) below the mean, at the mean, and 1 SD above the mean of supervisee levels were 1.6185, 1.4019, and 1.1853, respectively (see Figure 2). In other words, the interpersonally sensitive style and the supervisory working alliance were positively associated (B = 1.4019, p < .001), but the strength of this correlation decreased as supervisees reported higher levels of professional development. It is worth noting that supervisees at higher developmental levels tended to report a stronger supervisory working alliance in general, compared to those at lower levels. The linear model of the interpersonally sensitive style, supervisee levels, and the product of the two (interpersonally sensitive style × supervisee levels) explained 62.31% (p < .001) of the variance in the supervisory working alliance. A further look into the moderation effect of supervisee levels indicated that statistical significance consistently persisted as each indicator of supervisee levels (self and other awareness, motivation, and autonomy) was independently tested as a moderator between the interpersonally sensitive style and the supervisory working alliance (see Round 3 in Table 2).

Figure 2

Moderation Effect of Supervisee Levels With the Interpersonally Sensitive Style on the Supervisory Working Alliance

Note. N = 113. Predictor = Interpersonally Sensitive Style; Moderator = Supervisee Levels; Outcome = Supervisory Working Alliance. The three lines of color represent three regressions with the interpersonally sensitive style as predictor and the supervisory working alliance as outcome at different supervisee levels. The blue regression line denotes the group in which supervisee levels were one standard deviation (SD) below the mean, the green denotes the group in which supervisee levels were at the mean, and the pink denotes the group in which supervisee levels were one SD above the mean.

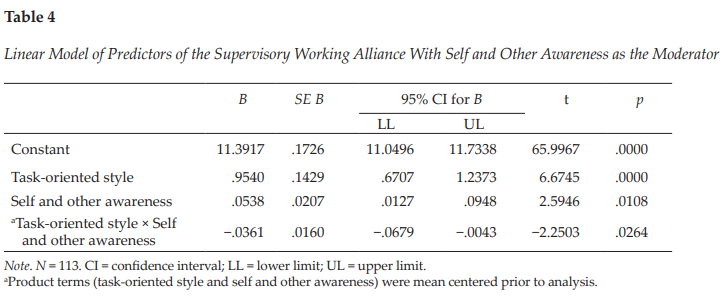

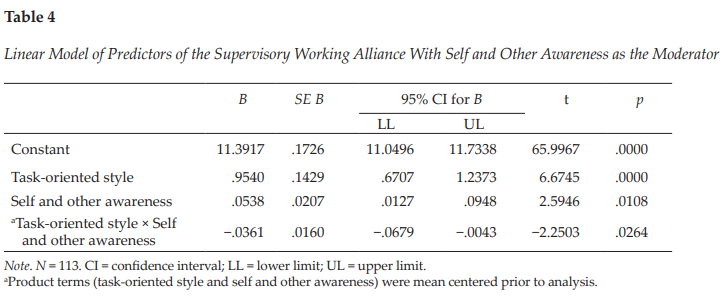

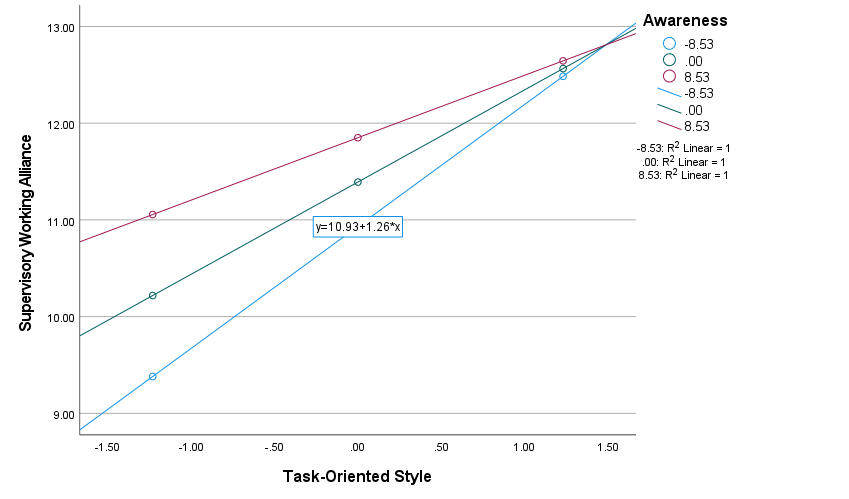

The second major finding was about the task-oriented supervisory style. When the three indicators of supervisee levels were independently examined as moderators, it was found that self and other awareness moderated the relationship between the task-oriented style and the supervisory working alliance, ΔR2 = .0311, F(1, 109) = 5.0639, p = .0264, with a small to medium effect size (f 2 = .05; Lorah & Wong, 2018). Similar to the first group of findings, the strength of the relationship between the task-oriented style and the supervisory working alliance varied based on the level of supervisee self and other awareness (one indicator of supervisee levels; see Table 4). A simple slopes analysis signified a consistent pattern—the task-oriented style and the supervisory working alliance were positively correlated, but the strength of this relationship decreased as supervisees rated higher on self and other awareness (see Figure 3). Specifically, the simple slopes for one SD below the mean, at the mean, and one SD above the mean of supervisee self and other awareness were 1.2620, 0.9540, and 0.6460, respectively. The area below the moderator (self and other awareness) value of 13.3857 constituted a region of significance in which the relationship between the task-oriented style and the supervisory working alliance was significant (p < .05; Johnson & Neyman, 1936). The linear model of the task-oriented style, supervisee self and other awareness, and the product of the two (task-oriented style × self and other awareness) accounted for 33.13% (p < .001) of the variance in the supervisory working alliance.

Discussion

Findings of the present study corroborated the positive correlation between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance that has been consistently identified in the existing literature (Efstation et al., 1990; Heppner & Handley, 1981; Ladany & Lehrman-Waterman, 1999; Ladany, Walker, & Melincoff, 2001). The intricacy of this relationship was further explored, and the current study confirmed that the strength of such correlation varied across different contexts. Supervisee levels and their three indicators turned out to be significant moderators in five models out of the 16 tested. Explicitly, the positive correlation between the interpersonally sensitive style and the supervisory working alliance was stronger for supervisees at lower levels of professional development but weaker for supervisees at higher levels. Furthermore, this significant moderation effect existed not only when supervisee levels were viewed as an overarching construct but when each indicator of supervisee levels was independently examined. Moreover, this moderation pattern was echoed by the positive association between the task-oriented style and the supervisory working alliance, wherein the correlation was stronger for supervisees at lower levels of self and other awareness (one indicator of supervisee levels) but weaker for those at higher levels of self and other awareness. Notably, supervisees at higher developmental levels (including indicators of supervisee levels) in all models with significant moderation effects reported a stronger supervisory working alliance than did their counterparts at lower levels.

According to developmental theories of supervision, supervisees broadly progress through a series of qualitatively different levels in the process of becoming effective counselors, despite myriad individual idiosyncrasies (Chagnon & Russell, 1995; Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). Entry-level supervisees typically focus on their own anxiety, their lack of skills and knowledge, and the likelihood that they are being regularly evaluated (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). Accordingly, beginning supervisees identified supervisor care and concern as one of the most important supervisor variables to allow supervisees to take risks and grow (Jordan, 2007). As such, interpersonally sensitive supervisors who are invested, committed, therapeutic, and perceptive (Friedlander & Ward, 1984) would be easily perceived as relationship-oriented and helpful in rapport building (one indicator of the supervisory working alliance) for supervisees early on in their training. Similarly, task-oriented supervisors are content-focused, goal-oriented, thorough, focused, practical, and structured (Friedlander & Ward, 1984).

Figure 3

Moderation Effect of Self and Other Awareness With the Task-Oriented Style on the Supervisory Working Alliance

Note. N = 113. Predictor = Task-Oriented Style; Moderator = Self and Other Awareness; Outcome = Supervisory Working Alliance. The three lines of color represent three regressions with the task-oriented style as predictor and the supervisory working alliance as outcome at different levels of self and other awareness (one indicator of supervisee levels). The blue regression line denotes the group in which supervisee self and other awareness was one standard deviation (SD) below the mean, the green denotes the group in which supervisee self and other awareness was at the mean, and the pink denotes the group in which supervisee self and other awareness was one SD above the mean.

Task-oriented supervisors can be perceived as particularly helpful and informative with client focus (a second indicator of the supervisory working alliance) for beginning supervisees (as indicated by their lower self and other awareness) who commonly experience substantial anxiety or fear pertaining to their lack of confidence in knowing what to do, being able to do it, and being evaluated by their clients or supervisors (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010).

Therefore, supervisees at lower levels of professional development were more likely to report a stronger supervisory working alliance as they perceived more interpersonally sensitive or task-oriented supervisor characteristics. As they progress to higher levels of development with accumulated knowledge, skills, and competencies, supervisees become more aware of clients and themselves, intrinsically and consistently motivated, and autonomous as practitioners (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010), which may in part explain why their ratings of the supervisory working alliance were less related to their perceptions of supervisor characteristics but generally higher than supervisees at lower levels of development.

In the present study, the moderator of supervisee levels as a composite score was only significant when the interpersonally sensitive style was the predictor; the moderator of self and other awareness (one indicator of supervisee levels) was also significant when the task-oriented style was the predictor. These findings resonated with the existing literature in that compared to the attractive style, the interpersonally sensitive and task-oriented styles tend to have stronger discriminating effects (Friedlander & Ward, 1984). For instance, practicum and internship students differed significantly in rating the task-oriented and interpersonally sensitive styles of their supervisors, but their perceptions about the attractive style were similar at both levels (Friedlander & Ward, 1984). Li, Duys, and Vispoel (2020) also found that supervisory state–transitional patterns differed significantly only based on the interpersonally sensitive style but not the other two styles.

Implications for Clinical Supervision

The supervisory working alliance is inextricably intertwined with supervisees’ willingness to disclose (Ladany et al., 1996), supervisee satisfaction with clinical supervision (Cheon et al., 2009; Ladany, Ellis, & Friedlander, 1999), supervisee work satisfaction and work-related stress (Sterner, 2009), and therapeutic working alliance (DePue et al., 2016; DePue et al., 2022), among others. Nelson et al. (2001) proposed that a key task in early supervision is to build a strong supervisory working alliance that serves as a foundation to manage future potential dilemmas in supervision, and the ongoing maintenance of this working alliance should be the supervisor’s responsibility throughout the supervisory relationship. Although the three supervisory styles appear to be clear-cut with distinguishable characteristics and roles (Friedlander & Ward, 1984), supervisors are encouraged to adopt a composite of different styles to varying degrees to better serve supervisees’ needs. As revealed by the present study, and also the extant literature (Efstation et al., 1990; Ladany, Walker, & Melincoff, 2001; Li et al., 2021), supervisees were more likely to report a stronger supervisory working alliance as they perceived their supervisors to adopt a mixture of three supervisory styles (i.e., higher overall ratings of supervisory styles).

Particularly, beginning supervisees are characteristic of a strong focus on self, extrinsic motivation, and high dependency on supervisors (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). Supervisors’ emphases on relationship-building (interpersonally sensitive style) and task focus (task-oriented style) would help build a safe, predictable supervision environment and enhance the working alliance with supervisees. Notably, although the strengths of the correlation between the interpersonally sensitive or task-oriented style and the supervisory working alliance were stronger for beginning supervisees, they did not suggest that these styles would not be effective in augmenting the alliance for supervisees at higher levels of professional development. The positive correlations still existed, albeit smoother, for more advanced supervisees, and they reported higher levels of supervisory working alliance in general, which may imply that these styles help maintain the working alliance that has been established early on in supervision.

Another point that is worth noting is that although no significant moderator was detected between the attractive style and the supervisory working alliance in the present study, the attractive style explained the most variance (68.1%, p < .001) in the supervisory working alliance, compared to the interpersonally sensitive (55.9%, p < .001) and task-oriented styles (24.1%, p < .001). This finding made it clear that the warm, supportive, friendly, open, and flexible features of attractive style supervisors are foundational to building and maintaining the supervisory working alliance, which does not differentiate across different levels of supervisees. As such, supervisors are encouraged to bring these qualities to their supervision and make them perceived by supervisees.

Limitations and Future Research

This study is not exempt from limitations that may be addressed in future research. Although two moderators (supervisee levels, self and other awareness) were found to be significant in the present study, the effect sizes of both were small to medium (f 21 = .07 and f 22 = .05), which were lower than the speculated medium effect size (f 2 = .15) during the a priori power analysis. Provided the effect sizes of .07 and .05 for the moderation effect, to achieve the statistical power of .80 with the α error probability of .05, the required sample size would be 115 and 159, respectively. Researchers need to be more mindful when recruiting participants to ensure the sufficient sample size. Additionally, although supervisees were asked to respond to the questionnaires consistently based on their perceptions of one supervisor, a constellation of factors could have affected their perceptions—for example, the timing of a participant’s supervisee status (e.g., currently receiving supervision vs. received supervision in the past), the potential dual role that a participant may be in (e.g., a doctoral student who is both a supervisee and a supervisor), the level of supervision (e.g., practicum, internship), and the length of the supervisory relationship (e.g., 2 months vs. 2 years). Researchers in future studies could also collect more information about participants (e.g., geographic distribution) to help readers better contextualize study results. Also, the current data set was collected in 2017–2018, which would not be able to capture more recent societal, cultural, political, and economic changes (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) that could have affected supervisee perceptions.

In the present study, the association between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance was examined in the context of different supervisee levels. Indeed, this alliance could be subject to many other factors, such as discussions of cultural variables in supervision (Gatmon et al., 2001), supervisor adherence to ethical guidelines (Ladany & Lehrman-Waterman, 1999), and relational supervision strategies (Shaffer & Friedlander, 2017), among others. Scholars may include more related variables to expand the current model so as to further disentangle the complex relationships among predictors of the supervisory working alliance.

Last, although multiple moderation effects identified in the present study were statistically significant and theoretically coherent, exactly how supervisees experience the supervisory working alliance in relation to different supervisory styles as they proceed along the professional development is less known. A longitudinal track of the same sample using repeated measures or a qualitative inquiry into participants’ lived experiences of the targeted phenomenon could enrich our understanding of the study variables in this research.

Conclusion

Although the positive correlation between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance is well documented in the existing literature, the present study examined such relationships specifically in the context of supervisee levels. Both supervisee levels (as a whole) and self and other awareness (one indicator of supervisee levels) appeared to be significant moderators under different contexts. These findings further revealed the intricacies embedded in the broad relationship between supervisory styles and the supervisory working alliance, pointed out future research directions concerning supervisee development, and encouraged supervisors to adopt a composite of styles to varying degrees to better support supervisee growth.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. SAGE.

Bahrick, A. S. (1989). Role induction for counselor trainees: Effects on the supervisory working alliance (Order No. 9014392) [Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Bernard, J. M. (1997). The discrimination model. In C. E. Watkins, Jr. (Ed.), Handbook of psychotherapy supervision (pp. 310–327). Wiley.

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2019). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (6th ed.). Pearson.

Bordin, E. S. (1983). A working alliance based model of supervision. The Counseling Psychologist, 11(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000083111007

Bucky, S. F., Marques, S., Daly, J., Alley, J., & Karp, A. (2010). Supervision characteristics related to the supervisory working alliance as rated by doctoral-level supervisees. The Clinical Supervisor, 29(2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2010.519270

Chagnon, J., & Russell, R. K. (1995). Assessment of supervisee developmental level and supervision environment across supervisor experience. Journal of Counseling & Development, 73(5), 553–558.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1995.tb01793.x

Cheon, H.-S., Blumer, M. L. C., Shih, A.-T., Murphy, M. J., & Sato, M. (2009). The influence of supervisor and supervisee matching, role conflict, and supervisory relationship on supervisee satisfaction. Contemporary Family Therapy, 31(1), 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-008-9078-y

DePue, M. K., Lambie, G. W., Liu, R., & Gonzalez, J. (2016). Investigating supervisory relationships and therapeutic alliances using structural equation modeling. Counselor Education and Supervision, 55(4), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12053

DePue, M. K., Liu, R., Lambie, G. W., & Gonzalez, J. (2022). Examining the effects of the supervisory relationship and therapeutic alliance on client outcomes in novice therapists. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 16(3), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000320

Efstation, J. F., Patton, M. J., & Kardash, C. M. (1990). Measuring the working alliance in counselor supervision. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 37(3), 322–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.37.3.322

Fernando, D. M., & Hulse-Killacky, D. (2005). The relationship of supervisory styles to satisfaction with supervision and the perceived self-efficacy of master’s-level counseling students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44(4), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb01757.x

Field, A. (2017). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). SAGE.

Friedlander, M. L., & Ward, L. G. (1984). Development and validation of the Supervisory Styles Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31(4), 541–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.31.4.541

Gatmon, D., Jackson, D., Koshkarian, L., Martos-Perry, N., Molina, A., Patel, N., & Rodolfa, E. (2001). Exploring ethnic, gender, and sexual orientation variables in supervision: Do they really matter? Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 29(2), 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2001.tb00508.x

Goodyear, R. K. (2014). Supervision as pedagogy: Attending to its essential instructional and learning processes. The Clinical Supervisor, 33(1), 82–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2014.918914

Hart, G. M., & Nance, D. (2003). Styles of counselor supervision as perceived by supervisors and supervisees. Counselor Education and Supervision, 43(2), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01838.x

Hatcher, R. L., Lindqvist, K., & Falkenström, F. (2020). Psychometric evaluation of the Working Alliance Inventory—Therapist version: Current and new short forms. Psychotherapy Research, 30(6), 706–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1677964

Heppner, P. P., & Handley, P. G. (1981). A study of the interpersonal influence process in supervision. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28(5), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.28.5.437

Holloway, E. (1995). Clinical supervision: A systems approach. SAGE.

Hunt, D. E. (1971). Matching models in education: The coordination of teaching methods with student characteristics. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, Monograph, 10, 87.

Johnson, P. O., & Neyman, J. (1936). Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs, 1, 57–93.

Jordan, K. (2007). Beginning supervisees’ identity: The importance of relationship variables and experience versus gender matches in the supervisee/supervisor interplay. The Clinical Supervisor, 25(1–2), 43–51.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v25n01_04

King, K. M., Borders, L. D., & Jones, C. T. (2020). Multicultural orientation in clinical supervision: Examining impact through dyadic data. The Clinical Supervisor, 39(2), 248–271.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2020.1763223

Ladany, N., Ellis, M. V., & Friedlander, M. L. (1999). The supervisory working alliance, trainee self-efficacy, and satisfaction. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77(4), 447–455.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02472.x

Ladany, N., Hill, C. E., Corbett, M. M., & Nutt, E. A. (1996). Nature, extent, and importance of what psychotherapy trainees do not disclose to their supervisors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(1), 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.43.1.10

Ladany, N., & Lehrman-Waterman, D. E. (1999). The content and frequency of supervisor self-disclosures and their relationship to supervisor style and the supervisory working alliance. Counselor Education and Supervision, 38(3), 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.1999.tb00567.x

Ladany, N., Marotta, S., & Muse-Burke, J. L. (2001). Counselor experience related to complexity of case conceptualization and supervision preference. Counselor Education and Supervision, 40(3), 203–219.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2001.tb01253.x

Ladany, N., Walker, J. A., & Melincoff, D. S. (2001). Supervisory style: Its relation to the supervisory working alliance and supervisor self-disclosure. Counselor Education and Supervision, 40(4), 263–275.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2001.tb01259.x

Li, D., Duys, D. K., & Granello, D. H. (2019). Interactional patterns of clinical supervision: Using sequential analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 10(1), 70–92.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21507686.2018.1553791

Li, D., Duys, D. K., & Granello, D. H. (2020). Applying Markov chain analysis to supervisory interactions. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 13(1), Article 6. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1325&context=jcps

Li, D., Duys, D. K., & Liu, Y. (2021). Working alliance as a mediator between supervisory styles and supervisee satisfaction. Teaching and Supervision in Counseling, 3(3), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.7290/tsc030305

Li, D., Duys, D. K., & Vispoel, W. P. (2020). Transitional dynamics of three supervisory styles using Markov chain analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(4), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12339

Li, D., Liu, Y., & Lee, I. (2018). Supervising Asian international counseling students: Using the integrative developmental model. Journal of International Students, 8(2), 1129–1151. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v8i2.137

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

Lorah, J. A., & Wong, Y. J. (2018). Contemporary applications of moderation analysis in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(5), 629–640. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000290

McNeill, B. W., Stoltenberg, C. D., & Romans, J. S. (1992). The Integrated Developmental Model of supervision: Scale development and validation procedures. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 23(6), 504–508. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.23.6.504

Munson, C. E. (1993). Clinical social work supervision (2nd ed.). Haworth Press.

Nelson, M. L., Gray, L. A., Friedlander, M. L., Ladany, N., & Walker, J. A. (2001). Toward relationship-centered supervision: Reply to Veach (2001) and Ellis (2001). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(4), 407–409.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.48.4.407

Norcross, J. C. (Ed.). (2011). Psychotherapy relationships that work: Evidence-based responsiveness (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Park, E. H., Ha, G., Lee, S., Lee, Y. Y., & Lee, S. M. (2019). Relationship between the supervisory working alliance and outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development, 97(4), 437–446.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12292

Pedersen, A. B., Mikkelsen, E. M., Cronin-Fenton, D., Kristensen, N. R., Pham, T. M., Pedersen, L., & Petersen, I. (2017). Missing data and multiple imputation in clinical epidemiological research. Clinical Epidemiology, 9, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S129785

Schafer, J. L. (1999). Multiple imputation: A primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 8(1), 3–15.

https://doi.org/10.1177/096228029900800102

Shaffer, K. S., & Friedlander, M. L. (2017). What do “interpersonally sensitive” supervisors do and how do supervisees experience a relational approach to supervision? Psychotherapy Research, 27(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1080877

Stenack, R. J., & Dye, H. A. (1982). Behavioral descriptions of counseling supervision roles. Counselor Education and Supervision, 21(4), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.1982.tb01692.x

Sterner, W. (2009). Influence of the supervisory working alliance on supervisee work satisfaction and work-related stress. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 31(3), 249–263.

https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.31.3.f3544l502401831g

Stoltenberg, C. D., & Delworth, U. (1987). Supervising counselors and therapists: A developmental approach. Jossey-Bass.

Stoltenberg, C. D., & McNeill, B. W. (2010). IDM supervision: An integrative developmental model for supervising counselors and therapists (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Dan Li, PhD, NCC, LSC (NC, K–12), is an assistant professor of counseling at the University of North Texas. Correspondence may be addressed to Dan Li, Welch Street Complex 2-112, 425 S. Welch St., Denton, TX 76201, Dan.Li@unt.edu.

Aug 20, 2021 | Author Videos, Volume 11 - Issue 3

Warren N. Ponder, Elizabeth A. Prosek, Tempa Sherrill

First responders are continually exposed to trauma-related events. Resilience is evidenced as a protective factor for mental health among first responders. However, there is a lack of assessments that measure the construct of resilience from a strength-based perspective. The present study used archival data from a treatment-seeking sample of 238 first responders to validate the 22-item Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-22) and its abbreviated version, the RSES-4, with two confirmatory factor analyses. Using a subsample of 190 first responders, correlational analyses were conducted of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 with measures of depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and suicidality confirming convergent and criterion validity. The two confirmatory analyses revealed a poor model fit for the RSES-22; however, the RSES-4 demonstrated an acceptable model fit. Overall, the RSES-4 may be a reliable and valid measure of resilience for treatment-seeking first responder populations.

Keywords: first responders, resilience, assessment, mental health, confirmatory factor analysis

First responder populations (i.e., law enforcement, emergency medical technicians, and fire rescue) are often repeatedly exposed to traumatic and life-threatening conditions (Greinacher et al., 2019). Researchers have concluded that such critical incidents could have a deleterious impact on first responders’ mental health, including the development of symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, or other diagnosable mental health disorders (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014; Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2010). In a systematic review, Wild et al. (2020) suggested the promise of resilience-based interventions to relieve trauma-related psychological disorders among first responders. However, they noted the operationalization and measure of resilience as limitations to their intervention research. Indeed, researchers have conflicting viewpoints on how to define and assess resilience. For example, White et al. (2010) purported popular measures of resilience rely on a deficit-based approach. Counselors operate from a strength-based lens (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014) and may prefer measures with a similar perspective. Additionally, counselors are mandated to administer assessments with acceptable psychometric properties that are normed on populations representative of the client (ACA, 2014, E.6.a., E.7.d.). For counselors working with first responder populations, resilience may be a factor of importance; however, appropriately measuring the construct warrants exploration. Therefore, the focus of this study was to validate a measure of resilience with strength-based principles among a sample of first responders.

Risk and Resilience Among First Responders

In a systematic review of the literature, Greinacher et al. (2019) described the incidents that first responders may experience as traumatic, including first-hand life-threatening events; secondary exposure and interaction with survivors of trauma; and frequent exposure to death, dead bodies, and injury. Law enforcement officers (LEOs) reported that the most severe critical incidents they encounter are making a mistake that injures or kills a colleague; having a colleague intentionally killed; and making a mistake that injures or kills a bystander (Weiss et al., 2010). Among emergency medical technicians (EMTs), critical incidents that evoked the most self-reported stress included responding to a scene involving family, friends, or others to the crew and seeing someone dying (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014). Exposure to these critical incidents may have consequences for first responders. For example, researchers concluded first responders may experience mental health symptoms as a result of the stress-related, repeated exposure (Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2010). Moreover, considering the cumulative nature of exposure (Donnelly & Bennett, 2014), researchers concluded first responders are at increased risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and generalized anxiety symptoms (Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2010). Symptoms commonly experienced among first responders include those associated with post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression.

In a collective review of first responders, Kleim and Westphal (2011) determined a prevalence rate for PTSD of 8%–32%, which is higher than the general population lifetime rate of 6.8–7.8 % (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2017). Some researchers have explored rates of PTSD by specific first responder population. For example, Klimley et al. (2018) concluded that 7%–19% of LEOs and 17%–22% of firefighters experience PTSD. Similarly, in a sample of LEOs, Jetelina and colleagues (2020) reported 20% of their participants met criteria for PTSD.

Generalized anxiety and depression are also prevalent mental health symptoms for first responders. Among a sample of firefighters and EMTs, 28% disclosed anxiety at moderate–severe and several levels (Jones et al., 2018). Furthermore, 17% of patrol LEOs reported an overall prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder (Jetelina et al., 2020). Additionally, first responders may be at higher risk for depression (Klimley et al., 2018), with estimated prevalence rates of 16%–26% (Kleim & Westphal, 2011). Comparatively, the past 12-month rate of major depressive disorder among the general population is 7% (APA, 2013). In a recent study, 16% of LEOs met criteria for major depressive disorder (Jetelina et al., 2020). Moreover, in a sample of firefighters and EMTs, 14% reported moderate–severe and severe depressive symptoms (Jones et al., 2018). Given these higher rates of distressful mental health symptoms, including post-traumatic stress, generalized anxiety, and depression, protective factors to reduce negative impacts are warranted.

Resilience

Broadly defined, resilience is “the ability to adopt to and rebound from change (whether it is from stress or adversity) in a healthy, positive and growth-oriented manner” (Burnett, 2017, p. 2). White and colleagues (2010) promoted a positive psychology approach to researching resilience, relying on strength-based characteristics of individuals who adapt after a stressor event. Similarly, other researchers explored how individuals’ cognitive flexibility, meaning-making, and restoration offer protection that may be collectively defined as resilience (Johnson et al., 2011).

A key element among definitions of resilience is one’s exposure to stress. Given their exposure to trauma-related incidents, first responders require the ability to cope or adapt in stressful situations (Greinacher et al., 2019). Some researchers have defined resilience as a strength-based response to stressful events (Burnett, 2017), in which healthy coping behaviors and cognitions allow individuals to overcome adverse experiences (Johnson et al., 2011; White et al., 2010). When surveyed about positive coping strategies, first responders most frequently reported resilience as important to their well-being (Crowe et al., 2017).

Researchers corroborated the potential impact of resilience for the population. For example, in samples of LEOs, researchers confirmed resilience served as a protective factor for PTSD (Klimley et al., 2018) and as a mediator between social support and PTSD symptoms (McCanlies et al., 2017). In a sample of firefighters, individual resilience mediated the indirect path between traumatic events and global perceived stress of PTSD, along with the direct path between traumatic events and PTSD symptoms (Lee et al., 2014). Their model demonstrated that those with higher levels of resilience were more protected from traumatic stress. Similarly, among emergency dispatchers, resilience was positively correlated with positive affect and post-traumatic growth, and negatively correlated with job stress (Steinkopf et al., 2018). The replete associations of resilience as a protective factor led researchers to develop resilience-based interventions. For example, researchers surmised promising results from mindfulness-based resilience interventions for firefighters (Joyce et al., 2019) and LEOs (Christopher et al., 2018). Moreover, Antony and colleagues (2020) concluded that resilience training programs demonstrated potential to reduce occupational stress among first responders.

Assessment of Resilience

Recognizing the significance of resilience as a mediating factor in PTSD among first responders and as a promising basis for interventions when working with LEOs, a reliable means to measure it among first responder clients is warranted. In a methodological review of resilience assessments, Windle and colleagues (2011) identified 19 different measures of resilience. They found 15 assessments were from original development and validation studies with four subsequent validation manuscripts from their original assessment, of which none were developed with military or first responder samples.

Subsequently, Johnson et al. (2011) developed the Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-22) to assess resilience among military populations. Unlike deficit-based assessments of resilience, they proposed a multidimensional construct representing how individuals respond to stressful experiences in adaptive or healthy ways. Cognitive flexibility, meaning-making, and restoration were identified as key elements when assessing for individuals’ characteristics connected to resilience when overcoming hardships. Initially they validated a five-factor structure for the RSES-22 with military active-duty and reserve components. Later, De La Rosa et al. (2016) re-examined the RSES-22. De La Rosa and colleagues discovered a unidimensional factor structure of the RSES-22 and validated a shorter 4-item subset of the instrument, the RSES-4, again among military populations.

It is currently unknown if the performance of the RSES-4 can be generalized to first responder populations. While there are some overlapping experiences between military populations and first responders in terms of exposure to trauma and high-risk occupations, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA; 2018) suggested differences in training and types of risk. In the counseling profession, these populations are categorized together, as evidenced by the Military and Government Counseling Association ACA division. Additionally, there may also be dual identities within the populations. For example, Lewis and Pathak (2014) found that 22% of LEOs and 15% of firefighters identified as veterans. Although the similarities of the populations may be enough to theorize the use of the same resilience measure, validation of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 among first responders remains unexamined.

Purpose of the Study

First responders are repeatedly exposed to traumatic and stressful events (Greinacher et al., 2019) and this exposure may impact their mental health, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and suicidality (Jetelina et al., 2020; Klimley et al., 2018). Though most measures of resilience are grounded in a deficit-based approach, researchers using a strength-based approach proposed resilience may be a protective factor for this population (Crowe et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020). Consequently, counselors need a means to assess resilience in their clinical practice from a strength-based conceptualization of clients.

Johnson et al. (2011) offered a non-deficit approach to measuring resilience in response to stressful events associated with military service. Thus far, researchers have conducted analyses of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 with military populations (De La Rosa et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2011; Prosek & Ponder, 2021), but not yet with first responders. While there are some overlapping characteristics between the populations, there are also unique differences that warrant research with discrete sampling (SAMHSA, 2018). In light of the importance of resilience as a protective factor for mental health among first responders, the purpose of the current study was to confirm the reliability and validity of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 when utilized with this population. In the current study, we hypothesized the measures would perform similarly among first responders and if so, the RSES-4 would offer counselors a brief assessment option in clinical practice that is both reliable and valid.

Method

Participants

Participants in the current non-probability, purposive sample study were first responders (N = 238) seeking clinical treatment at an outpatient, mental health nonprofit organization in the Southwestern United States. Participants’ mean age was 37.53 years (SD = 10.66). The majority of participants identified as men (75.2%; n = 179), with women representing 24.8% (n = 59) of the sample. In terms of race and ethnicity, participants identified as White (78.6%; n = 187), Latino/a (11.8%; n = 28), African American or Black (5.5%; n = 13), Native American (1.7%; n = 4), Asian American (1.3%; n = 3), and multiple ethnicities (1.3%; n = 3). The participants identified as first responders in three main categories: LEO (34.9%; n = 83), EMT (28.2%; n = 67), and fire rescue (25.2%; n = 60). Among the first responders, 26.9% reported previous military affiliation. As part of the secondary analysis, we utilized a subsample (n = 190) that was reflective of the larger sample (see Table 1).

Procedure

The data for this study were collected between 2015–2020 as part of the routine clinical assessment procedures at a nonprofit organization serving military service members, first responders, frontline health care workers, and their families. The agency representatives conduct clinical assessments with clients at intake, Session 6, Session 12, and Session 18 or when clinical services are concluded. We consulted with the second author’s Institutional Review Board, which determined the research as exempt, given the de-identified, archival nature of the data. For inclusion in this analysis, data needed to represent first responders, ages 18 or older, with a completed RSES-22 at intake. The RSES-4 are four questions within the RSES-22 measure; therefore, the participants did not have to complete an additional measure. For the secondary analysis, data from participants who also completed other mental health measures at intake were also included (see Measures).

Table 1

Demographics of Sample

| Characteristic |

Sample 1

(N = 238) |

Sample 2

(n = 190) |

| Age (Years) |

|

|

| Mean |

37.53 |

37.12 |

| Median |

35.50 |

35.00 |

| SD |

10.66 |

10.30 |

| Range |

46 |

45 |

| Time in Service (Years) |

|

|

| Mean |

11.62 |

11.65 |

| Median |

10.00 |

10.00 |

| SD |

9.33 |

9.37 |

| Range |

41 |

39 |

|

n (%) |

| First Responder Type |

|

|

Emergency Medical

Technicians |

67 (28.2%) |

54 (28.4%) |

| Fire Rescue |

60 (25.2%) |

45 (23.7%) |

| Law Enforcement |

83 (34.9%) |

72 (37.9%) |

| Other |

9 (3.8%) |

5 (2.6%) |

| Two or more |

10 (4.2%) |

6 (3.2%) |

| Not reported |

9 (3.8%) |

8 (4.2%) |

| Gender |

|

|

| Women |

59 (24.8%) |

47 (24.7%) |

| Men |

179 (75.2%) |

143 (75.3%) |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

| African American/Black |

13 (5.5%) |

8 (4.2%) |

| Asian American |

3 (1.3%) |

3 (1.6%) |

| Latino(a)/Hispanic |

28 (11.8%) |

24 (12.6%) |

| Multiple Ethnicities |

3 (1.3%) |

3 (1.6%) |

| Native American |

4 (1.7%) |

3 (1.6%) |

| White |

187 (78.6%) |

149 (78.4%) |

Note. Sample 2 is a subset of Sample 1. Time in service for Sample 1, n = 225;

time in service for Sample 2, n = 190.

Measures

Response to Stressful Experiences Scale

The Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-22) is a 22-item measure to assess dimensions of resilience, including meaning-making, active coping, cognitive flexibility, spirituality, and self-efficacy (Johnson et al., 2011). Participants respond to the prompt “During and after life’s most stressful events, I tend to” on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all like me) to 4 (exactly like me). Total scores range from 0 to 88 in which higher scores represent greater resilience. Example items include see it as a challenge that will make me better, pray or meditate, and find strength in the meaning, purpose, or mission of my life. Johnson et al. (2011) reported the RSES-22 demonstrates good internal consistency (α = .92) and test-retest reliability (α = .87) among samples from military populations. Further, the developers confirmed convergent, discriminant, concurrent, and incremental criterion validity (see Johnson et al., 2011). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .93.

Adapted Response to Stressful Experiences Scale

The adapted Response to Stressful Experiences Scale (RSES-4) is a 4-item measure to assess resilience as a unidimensional construct (De La Rosa et al., 2016). The prompt and Likert scale are consistent with the original RSES-22; however, it only includes four items: find a way to do what’s necessary to carry on, know I will bounce back, learn important and useful life lessons, and practice ways to handle it better next time. Total scores range from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. De La Rosa et al. (2016) reported acceptable internal consistency (α = .76–.78), test-retest reliability, and demonstrated criterion validity among multiple military samples. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .74.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a 9-item measure to assess depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks (Kroenke et al., 2001). Respondents rate the frequency of their symptoms on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Total scores range from 0 to 27, in which higher scores indicate increased severity of depressive symptoms. Example items include little interest or pleasure in doing things and feeling tired or having little energy. Kroenke et al. (2001) reported good internal consistency (α = .89) and established criterion and construct validity. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .88.

PTSD Checklist-5

The PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) is a 20-item measure for the presence of PTSD symptoms in the past month (Blevins et al., 2015). Participants respond on a 5-point Likert scale indicating frequency of PTSD-related symptoms from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Total scores range from 0 to 80, in which higher scores indicate more severity of PTSD-related symptoms. Example items include repeated, disturbing dreams of the stressful experience and trouble remembering important parts of the stressful experience. Blevins et al. (2015) reported good internal consistency (α = .94) and determined convergent and discriminant validity. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .93.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) is a 7-item measure to assess for anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks (Spitzer et al., 2006). Participants rate the frequency of the symptoms on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Total scores range from 0 to 21 with higher scores indicating greater severity of anxiety symptoms. Example items include not being able to stop or control worrying and becoming easily annoyed or irritable. Among patients from primary care settings, Spitzer et al. (2006) determined good internal consistency (α = .92) and established criterion, construct, and factorial validity. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .91.

Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised

The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R) is a 4-item measure to assess suicidality (Osman et al., 2001). Each item assesses a different dimension of suicidality: lifetime ideation and attempts, frequency of ideation in the past 12 months, threat of suicidal behaviors, and likelihood of suicidal behaviors (Gutierrez et al., 2001). Total scores range from 3 to 18, with higher scores indicating more risk of suicide. Example items include How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year? and How likely is it that you will attempt suicide someday? In a clinical sample, Osman et al. (2001) reported good internal consistency (α = .87) and established criterion validity. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha of the total score was .85.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 and SPSS Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) version 26.0. We examined the dataset for missing values, replacing 0.25% (32 of 12,836 values) of data with series means. We reviewed descriptive statistics of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 scales. We determined multivariate normality as evidenced by skewness less than 2.0 and kurtosis less than 7.0 (Dimitrov, 2012). We assessed reliability for the scales by interpreting Cronbach’s alphas and inter-item correlations to confirm internal consistency.

We conducted two separate confirmatory factor analyses to determine the model fit and factorial validity of the 22-item measure and adapted 4-item measure. We used several indices to conclude model fit: minimum discrepancy per degree of freedom (CMIN/DF) and p-values, root mean residual (RMR), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). According to Dimitrov (2012), values for the CMIN/DF < 2.0,p > .05, RMR < .08, GFI > .90, CFI > .90, TLI > .90, and RMSEA < .10 provide evidence of a strong model fit. To determine criterion validity, we assessed a subsample of participants (n = 190) who had completed the RSES-22, RSES-4, and four other psychological measures (i.e., PHQ-9, PCL-5, GAD-7, and SBQ-R). We determined convergent validity by conducting bivariate correlations between the RSES-22 and RSES-4.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

We computed means, standard deviations, 95% confidence interval (CI), and score ranges for the RSES-22 and RSES-4 (Table 2). Scores on the RSES-22 ranged from 19–88. Scores on the RSES-4 ranged from 3–16. Previous researchers using the RSES-22 on military samples reported mean scores of 57.64–70.74 with standard deviations between 8.15–15.42 (Johnson et al., 2011; Prosek & Ponder, 2021). In previous research of the RSES-4 with military samples, mean scores were 9.95–11.20 with standard deviations between 3.02–3.53(De La Rosa et al., 2016; Prosek & Ponder, 2021).

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics for RSES-22 and RSES-4

| Variable |

M |

SD |

95% CI |

Score Range |

| RSES-22 scores |

60.12 |

13.76 |

58.52, 61.86 |

19–88 |

| RSES-4 scores |

11.66 |

2.62 |

11.33, 11.99 |

3–16 |

Note. N = 238. RSES-22 = Response to Stressful Experiences Scale 22-item; RSES-4 = Response

to Stressful Experiences Scale 4-item adaptation.

Reliability Analyses

To determine the internal consistency of the resiliency measures, we computed Cronbach’s alphas. For the RSES-22, we found strong evidence of inter-item reliability (α = .93), which was consistent with the developers’ estimates (α = .93; Johnson et al., 2011). For the RSES-4, we assessed acceptable inter-item reliability (α = .74), which was slightly lower than previous estimates (α = .76–.78; De La Rosa et al., 2016). We calculated the correlation between items and computed the average of all the coefficients. The average inter-item correlation for the RSES-22 was .38, which falls within the acceptable range (.15–.50). The average inter-item correlation for the RSES-4 was .51, slightly above the acceptable range. Overall, evidence of internal consistency was confirmed for each scale.

Factorial Validity Analyses

We conducted two confirmatory factor analyses to assess the factor structure of the RSES-22 and RSES-4 for our sample of first responders receiving mental health services at a community clinic (Table 3). For the RSES-22, a proper solution converged in 10 iterations. Item loadings ranged between .31–.79, with 15 of 22 items loading significantly ( > .6) on the latent variable. It did not meet statistical criteria for good model fit: χ2 (209) = 825.17, p = .000, 90% CI [0.104, 0.120]. For the RSES-4, a proper solution converged in eight iterations. Item loadings ranged between .47–.80, with three of four items loading significantly ( > .6) on the latent variable. It met statistical criteria for good model fit: χ2 (2) = 5.89, p = .053, 90% CI [0.000, 0.179]. The CMIN/DF was above the suggested < 2.0 benchmark; however, the other fit indices indicated a model fit.

Table 3

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Fit Indices for RSES-22 and RSES-4

| Variable |

df |

χ2 |

CMIN/DF |

RMR |

GFI |

CFI |

TLI |

RMSEA |

90% CI |

| RSES-22 |

209 |

825.17/.000 |

3.95 |

.093 |

.749 |

.771 |

0.747 |

.112 |

0.104, 0.120 |

| RSES-4 |

2 |

5.89/.053 |

2.94 |

.020 |

.988 |

.981 |

0.944 |

.091 |

0.000, 0.179 |

Note. N = 238. RSES-22 = Response to Stressful Experiences Scale 22-item; RSES-4 = Response to Stressful Experiences Scale 4-item adaptation; CMIN/DF = Minimum Discrepancy per Degree of Freedom; RMR = Root Mean Square Residual;