Aug 10, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 2

Sabina Remmers de Vries, Christine D. Gonzales-Wong

U.S. consumers are spending billions on complementary and alternative medicines, and nearly half of those consumers on psychiatric prescription drugs also use herbal remedies. Clients may take herbaceuticals, over-the-counter drugs, and dietary supplements instead of, or in combination with, prescription drugs. This frequently occurs without the input or knowledge of prescribers, which can create significant problems for clients. There is a growing need for counselors to be familiar with herbal remedies, over-the-counter drugs, and dietary supplements. It is vital that counselors understand the potential interaction of these substances with prescribed medications, as well as their impact on clients’ emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. This article reviews relevant research and professional publications in order to provide an overview of the most commonly used psychoactive non-prescription products, counselor roles, client concerns, associated counseling ethics, diversity and cultural considerations, and counselor supervision concerns.

Keywords: counseling ethics, herbaceuticals, over-the-counter drugs, dietary supplements, diversity

A recent survey by the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Survey Consortium reported inadequate treatment of mental health conditions, especially in disadvantaged populations (Borges et al., 2020). In 2019, an estimated 20.6% of adults in the United States (51.5 million adults) experienced some type of mental health problem (National Institute of Mental Health, 2019). In an attempt to address mental health concerns, clients may take a variety of drugs, which can range from prescribed psychotropic medications to self-administered herbal remedies, over-the-counter drugs (OTCs), and dietary supplements (Ravven et al., 2011). Researchers have found that older adults, particularly, use prescription drugs, herbal remedies, and dietary supplements concurrently (Agbabiaka et al., 2017; Kaufman et al., 2002). Herbal remedies and dietary supplements are part of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs), which consist of various products and practices (Nahin et al., 2009).

In terms of mental health diagnoses (e.g., major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety disorder), prescription medication noncompliance can range between 28%–72% (Julius et al., 2009). There are many reasons clients do not adhere to their psychotropic medication regimens, including client-specific factors (psychological factors, habits, and beliefs), drug-specific factors (side effects), social/environmental factors (support system issues), and financial considerations (cost of medications, copays, and deductibles; Freudenberg-Hua et al., 2019; Julius et al., 2009; Phillips et al., 2016). There are clients who want to take their medication as prescribed but may not be able to afford it (Wang et al. 2015). Researchers found that clients might be prone to reduce use of prescription medication or substitute with OTCs and CAMs when experiencing financial pressures (Agbabiaka et al., 2017; Gibson, 2005; Wang et al., 2015). Another concern is lack of client knowledge pertaining to medications and diagnoses. Makaryus and Friedman (2005) found that only 27.9% of surveyed patients knew the names of all of the medications they had been prescribed, only 37.2% knew the purpose of all of their prescribed drugs, and only 14% knew the most frequent side effects.

For a variety of reasons, a substantial number of clients do not readily disclose the use of CAMs and OTCs to physicians or therapists (Agbabiaka et al., 2017; Ravven et al., 2011). This is concerning, as clients may be unaware of the pharmacological properties and side effects of these products. Considering these factors, counselors have a professional and ethical obligation to possess a working knowledge of psychopharmacology (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2016; Murray & Murray, 2007). We assert that this knowledge should include herbal remedies, OTCs, and dietary supplements.

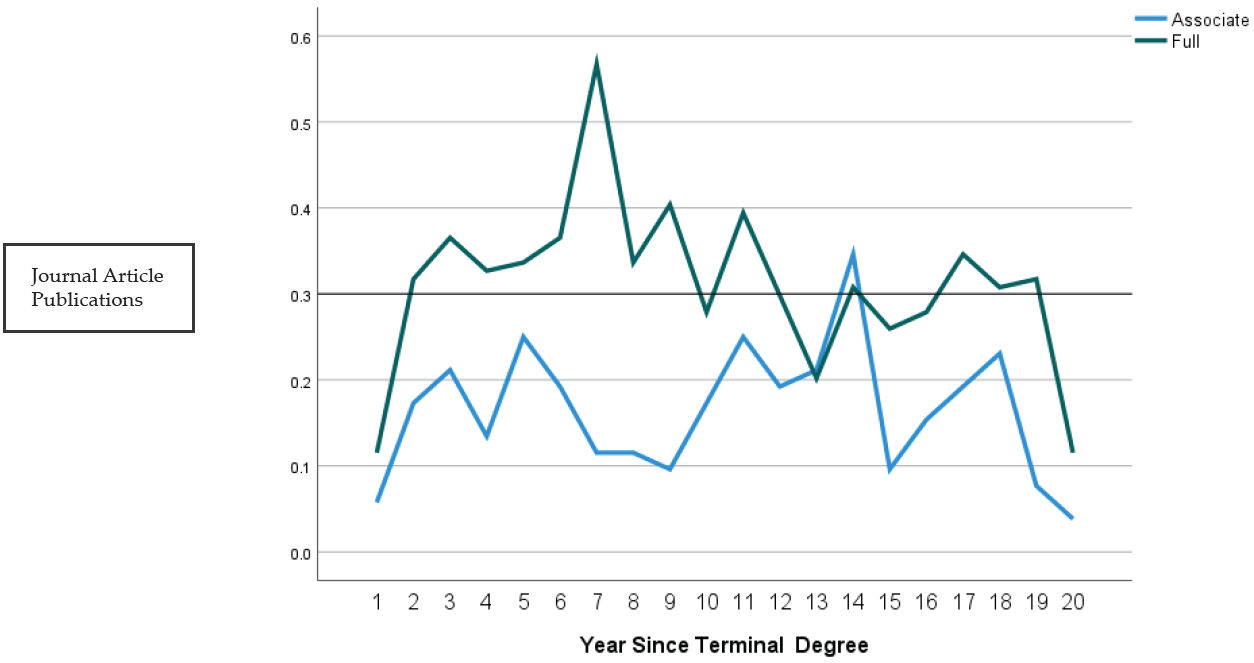

Despite the potential impact of psychoactive drugs on mental health, there is a paucity of research in the counseling literature that addresses psychopharmacology (Ingersoll, 2005; Sepulveda et al., 2016). There is even less counseling literature available that references herbal remedies, dietary supplements, and OTCs (Ingersoll, 2005; Kaut & Dickerson, 2007). A recent search of the ACA and ACA division journals returned very limited results on psychopharmacology, herbal remedies, OTCs, and dietary supplements. For example, the greatest number of articles pertaining to psychopharmacology was found in the Journal of Mental Health Counseling. The journal published five articles that ranged in year of publication from 2002 to 2011. The Journal of Counseling & Development published three articles that ranged in year of publication from 1985 to 2004. The only article related to herbaceuticals was published in the Journal of Counseling & Development in 2005. This article by Ingersoll (2005) discussed herbaceuticals in reference to the counseling profession. Although this review provided an overview of herbal remedies, it did not explore OTCs or dietary supplements. The counseling literature is in urgent need of expansion in this area because the scope of the counseling profession and mental health care are steadily evolving (Kaut, 2011; Sepulveda et al., 2016).

Given the lack of literature, counseling professionals providing services to clients may lack practical information pertaining to herbal remedies, OTCs, and dietary supplements. The goal of this primer is to provide counselors with an introduction to CAMs and OTCs that clients may be taking. It provides an overview of the most frequently used non-prescription psychoactive products, and addresses the actions of these products (pharmacodynamics) and how the body responds (pharmacokinetics) to these substances. The most significant effects as well as side effects are also discussed. In addition, effective communication with clients about prescription and non-prescription drugs is examined. It reviews ethical and cultural considerations pertaining to counseling clients who use psychoactive herbal remedies, OTCs, and dietary supplements. The herbal remedies, OTCs, and dietary supplements selected for this article were those that, based on the literature, appeared to be most commonly used.

Definition of Terms

For the purpose of this article, several terms are defined. For example, pharmacodynamics is the study of how the body responds to a drug. As such, it addresses therapeutic effects as well as side effects (Stahl, 2021). Pharmacokinetics describes how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes drugs and herbal remedies (He et al., 2011). Drugs and herbal remedies may affect organs, enzymes, and receptor sites. There are receptors located on neurons, which offer binding sites for neurotransmitters. These receptors are designed to respond to specific neurotransmitters. For example, dopamine will only bind to dopamine receptors and will not impact receptors designed for other neurotransmitters (Preston et al., 2021).

There are several neurotransmitters that are considered important in terms of mental health. Neurotransmitters can be agonistic, which means they can activate specific receptors. Neurotransmitters can also exert antagonistic effects by blocking receptor sites and preventing the activation of receptors (Preston et al., 2021). The most important neurotransmitters in terms of mental health are serotonin, dopamine, GABA, norepinephrine, glutamate, and acetylcholine (Stahl, 2021). It is important to note that these neurotransmitters are involved in complex brain functions and often act in combination with other substances and neurotransmitters. Serotonin plays a role in anxiety disorders and depression. Dopamine has been implicated in psychotic disorders as well as bipolar disorder. GABA is considered to be inhibitory to the firing of neurons. Norepinephrine is involved in many functions including memory and mood. Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter. Too much glutamate can lead to cell death. It has been implicated in bipolar disorder and Alzheimer’s disease. Acetylcholine is involved in memory and it has also been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease (Ingersoll & Rak, 2016).

The therapeutic index or window describes the parameter between an effective dose and a toxic dose of a drug. Some drugs such as lithium (used for the treatment of bipolar disorder) have a narrow therapeutic window, meaning that the effective dose and the toxic dose are in close proximity to each other and care must be taken when prescribing these drugs (Preston et al., 2021).

Drugs and herbal remedies may be additive (or synergistic). Additive effects are those in which a drug or herbal remedy may increase or improve the action of another drug or herbal remedy. Drugs or herbal remedies may also act antagonistically, which means the drug/herbal remedy renders another drug/herbal remedy less effective (Sharma et al., 2021). Drug interaction refers to how two or more drugs impact each other in terms of changes in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (Preston et al., 2021). Half-life refers to the time it takes the body to decrease the blood level of a drug by 50%. The half-life of drugs and herbal remedies can vary greatly, ranging from hours to days (Ingersoll & Rak, 2016). Many herbal remedies and drugs are metabolized through the cytochrome P450 enzymatic system located primarily in the liver and the gastrointestinal system (Stahl, 2021).

Finally, serotonin syndrome can be a life-threatening, adverse reaction to the often unintentional overuse of drugs containing serotonin, or drugs that inhibit serotonin reuptake. Scotton et al. (2019) provided an overview of serotonin syndrome, noting that serotonin serves many functions in the brain and body, including regulating cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functions as well as regulating body temperature and digestion. Serotonin syndrome symptoms can range from mild to severe and can even lead to death. There are a host of symptoms caused by serotonin toxicity (too much serotonin) ranging from diarrhea, tachycardia, agitation, and experiencing tremors to life-threatening symptoms such as delirium, neuromuscular rigidity, hyperthermia, seizures, and coma. The main group of drugs implicated in serotonin syndrome are SSRIs in combination with other serotonergic substances, which also include herbal remedies and OTCs (Scotton et al., 2019). The following sections provide counselors with a detailed overview of herbal remedies and OTCs.

Herbal Remedies

It has been estimated that about 25%–35% of Americans use or have used herbal medicines (Rashrash et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2011). A National Institute of Health survey (Nahin et al., 2009) revealed that in the United States, consumers spent $33.9 billion on CAMs, with $14.8 billion going toward non-vitamin, non-mineral, and natural products (e.g., herbal remedies, melatonin, fish oil, glucosamine). This is roughly equivalent to one-third of the out-of-pocket expenditure for prescription drugs (Nahin et al., 2009). Ravven et al. (2011) found that 44.7% of those using psychiatric prescription drugs also used herbal remedies at the same time.

The WHO defines herbal medicines as consisting of “herbs, herbal materials, herbal preparations, and finished herbal products” (Disch et al. 2017, p. 7). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers herbal products to be botanicals, which include plant parts, fungi, and algae (FDA, 2015). Many herbal remedies contain compounds that are pharmaceutically active. These compounds can exert an effect on the body or the central nervous system (Sarris, 2018). It has been estimated that about 40% of modern pharmaceuticals originated from naturally occurring treatments (Balick & Cox, 2021). However, in accordance with U.S. laws, herbal remedies or herbaceuticals cannot be marketed as drugs. The FDA is only able to regulate herbaceuticals as dietary supplements. In general, oversight seems marginal in comparison to prescription drugs. For example, manufacturers do not have to seek FDA approval before selling herbal remedies as is required for prescription drugs, and claims made by manufacturers pertaining to dietary supplements are not evaluated by the FDA (A. C. Brown, 2017). Herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not undergo rigorous research and development in the same manner as pharmaceuticals. The FDA is currently only able to monitor those herbal remedies and dietary supplements (and their corresponding ingredients) after they are sold and adverse reactions have been reported, making possible adulteration one of the most worrisome safety concerns pertaining to herbal remedies and dietary supplements (A. C. Brown, 2017). Research has shown that many herbaceuticals are contaminated and are augmented with unlabeled fillers (Crighton et al., 2019; Newmaster et al., 2013). Herbaceuticals can be contaminated by dust and pollen; microbes; parasites; fungi; pesticides; and heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, mercury, and cadmium (de Sousa Lima et al., 2020; Posadzki et al., 2013,: P. Singh et al., 2008). Also, product substitution is a common problem; however, the lack of more effective FDA oversight does not limit herbaceutical popularity or use (Newmaster et al., 2013).

Ravven et al. (2011) estimated that one-quarter to one-third of all herbal remedies in the United States are purchased with the intent to treat mental health conditions, especially anxiety and depression. CAMs such as herbal remedies and dietary supplements can create problems when they interact with medication prescribed by a physician. It is also important to note that many herbal remedies are not harmless; some can cause significant toxic side effects. Counselors must be familiar with the benefits and risks of the more widely used remedies, including St. John’s wort, valerian, kava, ginkgo, and cannabidiol.

St. John’s Wort

St. John’s wort has been found to be effective in the treatment of mild to moderate depression (Apaydin et al., 2016). There are some indications that it is comparable in effectiveness to tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) while also offering greater tolerability (Zirak et al., 2019). A meta-analysis including 27 studies and 3,808 participants confirmed that St. John’s wort seems to be as effective as SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants when used in the treatment of depression (Q. X. Ng et al., 2017). St. John’s wort was found to be associated with significantly lower discontinuation rates when compared to prescribed antidepressants, may cause fewer side effects than prescription antidepressants, and might be beneficial for clients who struggle with tolerating the side effects of commonly prescribed antidepressants (Q. X. Ng et al., 2017; Zirak et al., 2019). St. John’s wort is also considered a low-cost alternative to prescription antidepressants (Zirak et al., 2019). It is most frequently taken orally as either a whole herb formulation or as an extract, and can also be prepared as an herbal tea (Kladar et al., 2020).

Despite all the benefits it offers, taking St. John’s wort is not without risks. It acts as an SSRI and can lead to serotonin syndrome if combined with other SSRIs (Apaydin et al., 2016). In addition to affecting serotonin levels, St. John’s wort also impacts the neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine, GABA, and glutamate (Brahmachari, 2018). A main side effect is photosensitivity. It is also possible for St. John’s wort to negatively interact with MAOIs (LaFrance et al., 2000; Sidhu & Marwaha, 2021). In addition, due to cytochrome P450 induction, it also impacts the effectiveness of commonly used medications such as warfarin (used to treat blood clots), ciclosporin (an immunosuppressant), digoxin (for arrythmias and heart failure), some anticonvulsants, oral contraceptives, and other drugs (Barnes et al., 2001; Chrubasik-Hausmann et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2021). It has been noted that consumers continue to take St. John’s wort in combination with other drugs despite warnings, and it is important that clients receive further education on this topic (Chrubasik-Hausmann et al., 2019).

Valerian

Valerian root has been used as a sedative and hypnotic since antiquity (Perry et al., 2006). In Europe, valerian is widely used for the treatment of anxiety and sleep disorders (Shinjyo et al., 2020). It is considered to be effective in the treatment of anxiety, certain sleep disorders, some seizure disorders, possibly OCD, cognitive problems, and menstrual and menopausal symptoms (LaFrance et al., 2000; Shinjyo et al., 2020). The medicinal parts of the plant consist of the underground segments and roots and can be ingested as a juice, tea, dried herb, extract, or tincture (Gruenwald et al. 2007). Valerian is thought to enhance GABA transmission and prevent enzymatic breakdown of GABA in the brain (Mulyawan et al., 2020; K. Savage et al., 2018).

No noteworthy adverse side effects seem to occur when it is taken at an appropriate dose (LaFrance et al., 2000; Shinjyo et al., 2020). Effective doses can range from 450mg–1410mg per day for whole herb preparations, and 300mg–600mg per day for valerian extract (Shinjyo et al., 2020). The non–habit-forming properties and limited potential for side effects may be beneficial for some clients (Al-Attraqchi et al., 2020). However, if valerian is combined with hepatoxic drugs, it may increase the risk of hepatoxicity and could lead to liver damage. Also, taking valerian in combination with other sedating drugs or alcohol may result in additive or synergistic effects, resulting in amplification of sedation or intoxication greater than their combined effect; when taken with loperamide (anti-diarrhea drug), it may also cause delirium (Gruenwald et al., 2007).

Kava

Kava is a medicinal plant belonging to the pepper family with origins in the South Pacific. Traditionally, it has been used as a relaxant. Kava ingested in larger quantities can cause intoxication (Sarris, 2018). Kava is considered to be a hypnotic and a sedative, and it also has analgesic properties (Gruenwald et al., 2007). Hypnotics are drugs that tend to be sleep inducing, whereas sedatives tend to have calming, anxiety-reducing effects (Perry et al., 2006). The medicinally active part of the plant are the rhizomes or creeping rootstalks (Gruenwald et al., 2007). Traditionally, kava beverages were made from the rhizomes; however, in the United States it is mainly available as dry-filled capsule preparations and less commonly as a tincture (Liu et al., 2018). It acts on GABA and has been found to be effective in the treatment of anxiety and insomnia (Gruenwald et al., 2007; LaFrance et al., 2000; Perry et al., 2006; Sarris, 2018). It also has muscle-relaxing, anticonvulsive, and antispasmodic effects (Gruenwald et al., 2007). It is comparable to diazepam in its effectiveness when used to treat anxiety, but it can cause elevation of liver enzymes, which may be an indication of inflammation or even damage to liver cells (Gruenwald et al., 2007; Pantano et al., 2016). When combined with benzodiazepines, kava can cause disorientation and lethargy due to an additive effect in which both substances bind to similar neuron receptors (Surana et al., 2021; Tallarida, 2007).

It is important to note that in the 1990s, Germany approved the use of kava to treat anxiety-related disorders. In 2001, it was banned in Germany and across the European Union because of concerns over liver toxicity. The FDA issued a consumer advisory warning pertaining to the use of kava (Liu et al., 2018). Additional findings indicated only limited risk of liver toxicity when kava was used appropriately, and in 2015 the kava ban in Germany was lifted; however, kava products remain strictly regulated and monitored. In the United States, kava remains available over the counter (Liu et al., 2018).

Ginkgo

Ginkgo has been used in Chinese medicine for a millennium. The herbal remedy is derived from an ancient tree native to China, Japan, and Korea (Gruenwald et al., 2007; Ingersoll, 2005). Ginkgo biloba extract is made from the ginkgo tree leaves (S. K. Singh et al., 2019). It can be difficult to obtain a high-quality product because of poor oversight and regulation of herbal remedies (Booker et al., 2016); however, a standardized ginkgo biloba extract (EGb761) is available (Hashiguchi et al., 2015). Ginkgo shows some effectiveness in the treatment of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and other neurodegenerative disorders (S. K. Singh et al., 2019). Several meta-analyses have confirmed the effectiveness of ginkgo biloba. For example, a meta-analysis conducted by Liao et al. (2020) that included seven studies and 939 participants found that standardized gingko extract was effective in improving cognitive function in Alzheimer’s patients. It has been shown that ginkgo has anti-inflammatory, vascular, and cognition enhancing effects. Ginkgo is considered a GABA agonist as well as an antioxidant (S. K. Singh et al., 2019). In addition to improving cognitive function, it may also lessen oxidative damage, which has been implicated in the development of Alzheimer’s disease (S. K. Singh et al., 2019; Solas et al., 2015). Ginkgo appears to be effective in the treatment of mild to moderate memory loss in the elderly and it may slow the deterioration rate in severe dementia. In addition to neuroprotective properties, ginkgo also appears to be effective in the treatment of asthma, depression, and vascular deficiencies (S. K. Singh et al., 2019.) In terms of adverse effects, it may cause mild gastrointestinal upset, and it may also lower the seizure threshold in vulnerable individuals (Gruenwald et al., 2007).

Cannabidiol

Cannabidiol (CBD) is an active compound found in the cannabis plant (FDA, 2020a) and is most commonly promoted online as a remedy for anxiety and physical pain (Tran & Kavuluru, 2020). It also has promising potential for anti-inflammatory effects and has shown positive results in treating schizophrenia and social anxiety disorder (Burstein, 2015; Millar et al., 2019). CBD is a cannabinoid system modulator (Darkovska-Serafimovska et al., 2018) and differs from delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in that it does not produce intoxication (Burstein, 2015). The FDA has approved EpidiolexTM, a prescribed CBD-derived oral solution, for use with treating rare forms of epilepsy (FDA, 2020a).

Although under federal law it is currently illegal to add CBD to food or beverages, individual states have differing laws regarding the distribution of CBD, so the dosage of CBD products remains mostly unregulated (FDA, 2020b). Researchers examined 84 CBD products including vaporization liquids, oils, and tinctures and found that 69% of dosage labels were inaccurate (Bonn-Miller et al., 2017). Although unlikely, it is possible for consumers to test positive for THC in some drug screening tests because up to 0.3% THC may be allowed in CBD products in the United States (Gerace et al., 2021; Spindle et al., 2020). CBD taken in combination with other drugs can cause adverse drug reactions and drug–drug interactions (J. D. Brown & Winterstein, 2019). For example, when CBD is taken with a benzodiazepine (e.g., alprazolam for anxiety), it can increase the risk of side effects of alprazolam. It should be noted that researchers mainly examined EpidiolexTM in studies exploring drug–drug interactions and adverse side effects, as the CBD dosage is controlled in this formulation (J. D. Brown & Winterstein, 2019). Because of the wide dosage variance in unregulated CBD products, it is difficult to research and predict the effects. In a review of clinical studies, the therapeutic window appears to be wide, but phase III trials have not been conducted to provide conclusive evidence (Millar et al., 2019).

Over-the-Counter Medications

Globally, in 2017 the OTC market reached $80.2 billion in consumer spending (PR Newswire, n.d.) and research indicates that 81% of American adults reach for OTCs, or medicine that can be purchased without a prescription, as an initial treatment for minor medical conditions. The average American makes 26 trips to OTC outlets compared to three doctor’s visits annually, and there are around 54,000 pharmacies in the United States compared to over 750,000 retailers that sell OTCs (Consumer Healthcare Products Association, n.d.). Despite the popularity of OTCs, many clients lack the required health knowledge to safely self-medicate.

Acetaminophen

Many consumers do not know that an overly high dose of acetaminophen could be lethal, or that varying OTCs contain acetaminophen and taking more than one of these products simultaneously might lead to an unintentional overdose (Boudjemai et al., 2013; Wolf et al., 2012). There are a number of OTCs that have psychotropic properties. For example, Durso et al. (2015) found that acetaminophen blunts more than just pain—it seems that the OTC pain medication also diminishes emotional responses to both negative and positive events. Researchers went so far as to label acetaminophen as an “all-purpose emotional reliever” (Durso et al., 2015, p. 756). In addition, it is of interest to note that acetaminophen decreases a person’s ability to empathize with pain experienced by others (Durso et al., 2015). Roughly one-quarter of American adults are taking this drug on a weekly basis. It begs the question as to the societal implications or social cost of its frequent use (Mischkowski et al., 2016, 2019).

Sleep Aids

It is common for people to experience trouble with falling asleep or staying asleep. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) indicates that one-third of adults in the United States experience insomnia symptoms. This issue is evident in consumer spending: In 2018 Americans spent $410 million on OTC sleep aids (Consumer Healthcare Products Association, n.d.).

Diphenhydramine and doxylamine are OTC antihistamines with considerable sedative properties and are marketed as treatment options for sleep disturbances (Perry et al., 2006). It was found that doxylamine seems to be as effective as the barbiturate secobarbital; also, doxylamine is comparable to zolpidem, a frequently prescribed sleep aid. Diphenhydramine and doxylamine are considered to be non-selective histamine H1 receptor antagonists (antihistamines for the prevention of allergies) and they are also anticholinergic (causing dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, blurred vision, and sedation; Perry et al., 2006). Abraham et al. (2017) found that 58.6% of the elderly sample surveyed used at least one sleep aid containing diphenhydramine or doxylamine.

Chlorpheniramine is also an OTC antihistamine, and it can be found as the sole active compound in remedies such as Chlor-TrimetonTM and similar generic formulations (Hellbom, 2006), or in combination with other substances to treat cold and allergy symptoms. Popular cold remedy combinations of chlorpheniramine and dextromethorphan (a cough suppressant also available over the counter) can be problematic. Dextromethorphan is a moderate SSRI (Boyer & Shannon, 2005; Foong et al., 2018), which means it acts like an SSRI antidepressant. Furthermore, diphenhydramine and chlorpheniramine have also been found to block serotonin reuptake, making them some of the oldest SSRIs (Foong et al., 2018; Hellbom, 2006; Ravina, 2011). It is not commonly known that fluoxetine (Prozac®) was derived from diphenhydramine as a result of attempts to make this drug less sedating (Ravina, 2011).

Despite the fact that these products are readily available over the counter, drugs like diphenhydramine as well as doxylamine are not designed for the long-term treatment of sleep disorders (Abraham et al., 2017). There is a lack of supporting literature in terms of using these drugs for treatment of mental health concerns (Culpepper & Wingertzahn, 2015). It is important to note that if clients are prescribed an antidepressant, chlorpheniramine as well as diphenhydramine can increase the risk of serotonin syndrome (Abraham et al., 2017). It is also important to keep in mind that diphenhydramine can be found in combination with pain relievers/fever reducers such as acetaminophen. This may add to the risk of developing serotonin syndrome because clients may not be aware of the exact content of these formulations (Abraham et al., 2017). Diphenhydramine may also be a drug of abuse. When taken in high doses, it may create a buzz or high because of possible activation of the dopamine-related reward pathways of the brain, which may lead to drug-seeking behaviors (Saran et al., 2017). Finally, a lethal dose of doxylamine can range from 25mg–250mg per kg in body weight (Müller, 1992, as cited in Bockholdt et al., 2001). Doxylamine overdose symptoms include respiratory depression, sedation, and coma (Bockholdt et al., 2001).

Dietary Supplements

Dietary supplements are defined as dietary ingredients that include vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and herbs or botanicals, as well as other substances that can be used to supplement the diet (FDA, 2015). Much like herbal remedies, the FDA does not sufficiently regulate dietary supplements.

Melatonin

Melatonin is a naturally occurring substance that is synthesized from tryptophan. It is secreted by the pineal gland in order to regulate the circadian rhythm. Melatonin is effective in inducing sleep when taken orally as well. In the United States, synthesized melatonin is marketed as a dietary supplement and can be purchased over the counter in doses ranging from 0.3mg–10mg (Perry et al., 2006).

Because the FDA does not sufficiently regulate melatonin, it is important to note that specific dosing guidelines do not exist (R. A. Savage et al., 2020). However, studies have found that doses over 5mg are no more effective than lower doses. Side effects may include headache, fatigue, dizziness, irritability, abdominal cramps, itchiness, and elevated alkaline phosphatase in long-term use (Perry et al., 2006). Furthermore, it was found that the labeled concentration of melatonin content frequently does not match actual content. Erland and Saxena (2017) found variability of melatonin in various samples ranging between ˗83% (lesser dose) to +478% (higher dose). Erland and Saxena also found that eight of their 30 samples contained undisclosed/unlabeled serotonin in addition to melatonin, which may add to health concerns. The majority of supplements that were found to include serotonin also contained other additives such as passionflower, hops, and valerian root. Interestingly, serotonin is a precursor to melatonin (Erland & Saxena, 2017). Unlabeled serotonin content poses a significant problem because many clients self-prescribe melatonin supplements and, under the right circumstances, a relatively small dose can lead to serotonin syndrome (Erland & Saxena, 2017).

SAMe

SAMe (S-Adenosyl-L-methionine) is required for the brain to synthesize the neurotransmitters norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin. In the United States, SAMe has been widely available over the counter since the late 1990s (Mischoulon & Fava, 2002). The general consensus is that it is effective in treating depression (Sakurai et al., 2020). Also, SAMe can be utilized as an adjunct to antidepressant medications (Papakostas, 2009; Sakurai et al., 2020). It can be taken orally or be administered by intravenous infusion (Sakurai et al. 2020). A recommended dose of SAMe can range from 400mg–1600mg per day; however, some individuals may have to take a higher dose to achieve improvement of depressive symptoms (Mischoulon & Fava, 2002; Olsufka & Abraham, 2017; Sakurai et al., 2020). Overall, use of SAMe results in little to no side effects, although at higher doses SAMe may cause gastrointestinal discomfort (Sakurai et al., 2020). In clients diagnosed with bipolar disorder it may cause anxiety and mania (Mischoulon & Fava, 2002; Olsufka & Abraham, 2017).

Tryptophan

Tryptophan is an amino acid that the body requires to synthesize proteins (Modoux et al., 2020). Tryptophan is also needed to synthesize serotonin and melatonin (Modoux et al., 2020). Tryptophan was available in the United States in the 1990s. At that time, there was some evidence that it might be effective in treating depression (Perry et al., 2006). Tryptophan was taken off the market after there were concerns that it caused several deaths because of eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (EMS), an inflammatory disorder that affects multiple body parts and causes high white blood cell counts. There was some speculation that in these cases the ingested tryptophan may have been contaminated (Perry et al., 2006). Tryptophan can now be purchased over the counter again; however, Perry et al. (2006) suggested that because of EMS risks, clients should be encouraged to consult with their physician before taking this product.

The Role of the Counselor

Concerns regarding psychotropic medication can find their way into counseling settings. Clients may take any number of drugs, ranging from prescribed psychotropic medications to herbal remedies, OTCs, and dietary supplements. In order to be able to provide effective counseling services, counselors must attempt to understand the role these drugs play in clients’ lives. Areas to consider include education, assessment, diagnosis, case conceptualization, treatment planning, and client advocacy, such as referral and consultation with medical and psychiatric treatment providers.

Education

Clinicians should be knowledgeable about the intended use of prescribed psychoactive medications as well as herbal remedies, OTCs, and dietary supplements. It is also important to be familiar with route of administration, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, therapeutic effects, side effects, and contraindications. CAMs frequently fall in and out of favor because of marketing efforts and fads (Crawford & Leventis, 2005; Smith et al., 2017). Consequently, in order to stay abreast of current trends, it is prudent to pursue continuing education in this area. Counselors should be skilled in nonjudgmentally addressing CAMs and OTCs in a variety of areas, including assessment, education, and referrals.

CACREP’s 2016 standards require that counseling students receive education in the “classifications, indications, and contraindications of commonly prescribed psychopharmacological medications for appropriate medical referrals and consultation” (CACREP, 2015, Section 5.2.h., p. 18). Many states, including Texas (Professional Counselors, 2021), require psychopharmacology training for counselor licensure. It could be argued that this education should also extend to herbal remedies, OTCs, and dietary supplements.

Assessment

Counselors also have the option to be proactive and include questions inquiring about CAMs, OTCs, and prescription medication during the intake process, as well as intermittently throughout the counseling relationship with clients. Assessment may include questions about dosage, frequency, and reason for use. Because clients may not think to share CAM and OTC use with counselors, direct questions during the intake process can initiate conversations about psychoactive drugs. Counselors also have the opportunity to educate clients on the biopsychosocial impact of psychoactive drugs that may play a role in their presenting concerns (Kaut & Dickinson, 2007). Assessment also allows counselors to educate clients on the risks and benefits of CAM and OTC use.

Diagnosis

Knowledge about clients’ use of herbal supplements, OTCs, and dietary supplements is important, as clients may unknowingly experience substance-induced problems. For example, garcinia cambogia, a popular weight-loss herbal supplement, can induce mania (Hendrickson et al., 2016). Clients who have taken garcinia cambogia may present with manic symptoms such as grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, irritability, and hallucinations (Hendrickson et al., 2016). Psychosis has also been induced by L-dopa and dendrobium extract, found in OTC performance-enhancing supplements (Flynn et al., 2016), and by herb–herb interactions when taking multiple supplements simultaneously (Wong et al., 2016). Because of the potential for substance-induced problems, counselors should make differential diagnoses by discussing all potential conditions that may be causing the client’s symptoms, which includes ruling out substance etiology (First, 2013).

Case Conceptualization

To understand the nature, history, and context of clients’ presenting concerns, counselors should engage in a case conceptualization process. Macneil et al. (2012) recommended considering predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating, and protective/positive factors that may contribute to or alleviate the client’s presenting concerns. Counselors should consider how herbal supplements, OTCs, and dietary supplements may be a precipitating, perpetuating, and/or positive factor, as these substances may contribute to or alleviate clients’ symptoms.

Treatment Planning

Counselors consider a client’s diagnosis, presenting concerns, and case conceptualization information to make a personalized treatment plan (Macneil et al., 2012). If CAMs and OTCs are relevant to the client’s treatment, counselors may include the monitoring of such substances as an intervention. This would include assessing the client’s use and compliance with their medication regimen, inquiring about side effects, and evaluating how these factors relate to the client’s mental health. Counselors should only practice within the scope of their license, and clients must be referred to qualified medical providers for any medical or medicinal concerns. Counselor roles may include the referral of a client to a specialist such as a psychiatrist for medication evaluation as a component of the client’s treatment plan. Counselors should ensure that physicians they refer to provide quality care.

Client Advocacy

Counselors may advocate for their clients and consult with prescribers on clients’ behalf (Bentley & Walsh, 2013). Again, a significant concern is that clients frequently do not discuss the use of alternative treatments with their physician (Abraham et al., 2017; Agbabiaka et al., 2017). Direct inquiry into the use of CAMs and OTCs and client education can bring about greater clarity and the opportunity to ask clients to discuss these with their medical providers (Agbabiaka et al., 2017). Counselors can encourage and educate clients on how to discuss CAMs and OTCs with their physician or psychiatrist. When assessing, educating, referring, and advocating, counselors must abide by ethical and legal standards.

Ethical Considerations

It is important to note that counselors should under no circumstances recommend herbal remedies, OTCs, or dietary supplements to clients because doing so would be outside of the scope of their practice (ACA, 2014; Ingersoll & Rak, 2016). The ACA (2014) Code of Ethics specifies that “counselors practice only within the boundaries of their competence, based on their education, training, supervised experience, state and national professional credentials, and appropriate professional experience” (Section C.2.a, p. 8). Despite this, professional role boundaries related to psychopharmacology between prescribing physicians and counselors can be unclear at times (Ingersoll & Rak, 2016). For example, clients may ask counselors for advice on medication. So, in addition to keeping abreast of trends in the use of CAMs and OTCs and attending to this during intake and work with clients, developing consultation and referral resources in this area is an important consideration for counselors (Preston et al., 2021). Resources may vary from state to state given differences in licensing and certification of health professionals and general prescribing privileges for psychotropic medications.

There are wide-ranging opinions among counselors pertaining to prescribing psychotropic medications to clients (Ingersoll & Rak, 2016). These opinions cannot dictate whether a client is referred to the medical community for medication evaluation. Counselors are ethically obligated to refer clients to a medical professional when necessary, including referrals related to pharmacotherapy as well as non-prescription drugs, herbal remedies, or dietary supplements. Withholding such a referral may constitute malpractice. The ACA (2014) Code of Ethics states that “counselors act to avoid harming their clients, trainees, and research participants and to minimize or to remedy unavoidable or unanticipated harm” (ACA, 2014, Section A.4.a., p. 4) and also specifies that “counselors are aware of—and avoid imposing—their own values, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors” (ACA, 2014, Section A.4.b., p. 8).

Diversity and Cultural Considerations

It is important that counselors are able to discuss racial and cultural considerations with clients to ensure competence and to promote the welfare of clients (ACA, 2014). Our commitment to diversity and inclusion must also be extended to clients who are taking psychoactive substances and herbal remedies. It should be noted that genetic research has found that there are a number of significant differences in terms of drug metabolism, effectiveness, and side effects among ethnic groups (Burroughs et al., 2002). At the same time, race, age, and gender can be crude or flawed yardsticks for predicting responsiveness to drugs; however, counselors do need to be aware that there are significant variations in response to drugs based on multiple factors, and that these variations are more the norm than the exception (Bhugra & Bhui, 2018; Burroughs et al., 2002).

Further, racial and ethnic disparities persist in health care, and this may contribute to clients’ decisions to take CAMs and OTCs (Gureje et al., 2015). Less than 6% of active physicians are Hispanic and less than 5% are Black (American Association of Medical Colleges, 2019), even though 40% of Americans are non-White or Hispanic (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). This can create barriers to obtaining and providing appropriate care, as it has been found that racial or ethnic minority clients are less likely than their White counterparts to receive prescriptions to treat their mental health conditions (Coleman et al., 2016). This inequality may lead clients to seek CAMs or OTCs to treat mental health issues (Coleman et al., 2016; Gureje et al., 2015).

Counselors should consider cultural factors such as a preference for herbal remedies, immigration status and language use, socioeconomic status, and availability of insurance coverage. Traditional medicine often involves the use of herbal remedies and is closely connected to one’s culture, so counselors should be mindful to discuss CAMs with clients in a nonjudgmental and empathetic manner. Traditional forms of medicine have a long history, having evolved over thousands of years (Gureje et al., 2015). Depending on historical or cultural background, there are numerous ways in which these healing methods are being implemented (Gureje et al., 2015).

It is also important for counselors to recognize that traditional medicine is commonly used in middle- and low-income countries and that transplants from these cultural groups in the United States may use or even prefer these types of healing approaches (Gureje et al., 2015). Poverty also plays a role in the use of traditional medicine versus conventional medicine. For many, traditional medicine may be the only affordable or accessible health care option (Gureje et al., 2015). In Mexican culture, individuals may seek assistance from curandera/os for physical or psychological issues (Hoskins & Padrón, 2018). Traditional medicine may be used to treat nervios, depression, and anxiety (Guzmán Gutierrez et al., 2014). For example, an infusion of the yoloxchitl (magnolia) plant may be used to treat nervios, a culture-specific syndrome that can share symptoms of depression and anxiety (Guzmán Gutierrez et al., 2014). Because curanderismo is also a spiritual practice, counselors should be sensitive to the values that may be tied to the use of herbs for mental health concerns.

In addition, some clients prefer to use traditional medicine as well as conventional medicine (Gureje et al., 2015). Although countries such as China and India are formally supporting the integration of traditional and conventional medicine (Gureje et al., 2015), Western medicine and traditional herbal medicine use are not always compatible (C. H. Ng & Bousman, 2018). Because traditional medicine practices are culture-specific, asking clients if they utilize traditional medicine can be an invitation to share about their practices and allow counselors to approach their clients holistically.

Conclusion

There is a growing need for counselors to possess a working knowledge not only of prescribed psychotropic medications, but also of herbal remedies, OTCs, and dietary supplements. As more training programs and licensure boards require psychopharmacology education, counselors should be invested in learning about other psychoactive products clients may be taking. Counselors have the opportunity to assess clients’ use of CAMs and OTCs and consider how they may be relevant to diagnosis, case conceptualization, and treatment planning. In addition, counselors can educate clients about psychoactive products and their impact on mental health. Counselors can also provide referrals and serve as advocates for their clients when working with prescribing providers. From an ethical perspective, psychopharmacology knowledge is increasingly required in order to provide adequate client care. Although this may appear to move counseling practices more toward the medical model, in reality it means the profession is responding to current trends in counseling and client needs. Understanding the potential impact of herbal remedies, OTCs, and dietary supplements on clients’ mood, thinking, and behavior is imperative to understand the whole person and to maintain a holistic counseling approach.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Abraham, O., Schleiden, L., & Albert, S. M. (2017). Over-the-counter medications containing diphenhydramine and doxylamine used by older adults to improve sleep. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 39(4), 808–817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-017-0467-x

Agbabiaka, T. B., Wider, B., Watson, L. K., & Goodman, C. (2017). Concurrent use of prescription drugs and herbal medicinal products in older adults: A systematic review. Drugs & Aging, 34(12), 891–905.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0501-7

Al-Attraqchi, O. H. A., Deb, P. K., & Al-Attraqchi, N. H. A. (2020). Review of the phytochemistry and pharmacological properties of valeriana officinalis. Current Traditional Medicine, 6(4), 260–277.

https://doi.org/10.2174/2215083805666190314112755

American Association of Medical Colleges. (2019). Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018 [Figure]. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/Resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Apaydin, E. A., Maher, A. R., Shanman, R., Booth, M. S., Miles, J. N. V., Sorbero, M. E., & Hempel, S. (2016). A systematic review of St. John’s wort for major depressive disorder. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), Article 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0325-2

Balick, M. J., & Cox, P. A. (2021). Plants, people, and culture: The science of ethnobotany (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

Barnes, J., Anderson, L. A., & Phillipson, J. D. (2001). St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum L.): A review of its chemistry, pharmacology and clinical properties. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 53(5), 583–600. https://doi.org/10.1211/0022357011775910

Bentley, K. J., & Walsh, J. (2013). The social worker and psychotropic medication: Toward effective collaboration with mental health clients, families, and providers (4th ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Bhugra, D., & Bhui, K. (Eds.). (2018). Textbook of cultural psychiatry (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bockholdt, B., Klug, E., & Schneider, V. (2001). Suicide through doxylamine poisoning. Forensic Science International, 119(1), 138–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0379-0738(00)00393-5

Bonn-Miller, M. O., Loflin, M. J. E., Thomas, B. F., Marcu, J. P., Hyke, T., & Vandrey, R. (2017). Labeling accuracy of cannabidiol extracts sold online. JAMA, 318(17), 1708–1709. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.11909

Booker, A., Frommenwiler, D., Reich, E., Horsfield, S., & Heinrich, M. (2016). Adulteration and poor quality of Ginkgo biloba supplements. Journal of Herbal Medicine, 6(2), 79–87.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hermed.2016.04.003

Borges, G., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Andrade, L., Benjet, C., Cia, A., Kessler, R. C., Orozco, R., Sampson, N., Stagnaro, J. C., Torres, Y., Viana, M. C., & Medina-Mora, M. E. (2020). Twelve-month mental health service use in six countries of the Americas: A regional report from the World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000477

Boudjemai, Y., Mbida, P., Potinet-Pagliaroli, V., Géffard, F., Leboucher, G., Brazier, J.-L., Allenet, B., & Charpiat, B. (2013). Patients’ knowledge about paracetamol (acetaminophen): A study in a French hospital emergency department. Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises, 71(4), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharma.2013.03.001

Boyer, E. W., & Shannon, M. (2005). The serotonin syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352(11), 1112–1120. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra041867

Brahmachari, G. (Ed.). (2018). Discovery and development of neuroprotective agents from natural products. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809593-5.12001-4

Brown, A. C. (2017). An overview of herb and dietary supplement efficacy, safety and government regulations in the United States with suggested improvements. Part 1 of 5 series. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 107 (Part A), 449–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2016.11.001

Brown, J. D., & Winterstein, A. G. (2019). Potential adverse drug events and drug–drug interactions with medical and consumer cannabidiol (CBD) use. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(7), 989.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8070989

Burroughs, V. J., Maxey, R. W., Crawley, L. M., & Levy, R. A. (2002). Cultural and genetic diversity in America: The need for individualized pharmaceutical treatment. National Medical Association and National Pharmaceutical Council. https://www.nccdp.org/resources/CulturalandGeneticDiversity.pdf

Burstein, S. (2015). Cannabidiol (CBD) and its analogs: A review of their effects on inflammation. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry, 23(7), 1377–1385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2015.01.059

Chrubasik-Hausmann, S., Vlachojannis, J., & McLachlan, A. J. (2019). Understanding drug interactions with St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum L.): Impact of hyperforin content. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 71(1), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphp.12858

Coleman, K. J., Stewart, C., Waitzfelder, B. E., Zeber, J. E., Morales, L. S., Ahmed, A. T., Ahmedani, B. K., Beck, A., Copeland, L. A., Cummings, J. R., Hunkeler, E. M., Lindberg, N. M., Lynch, F., Lu, C. Y., Owen-Smith, A. A., Trinacty, C. M., Whitebird, R. R., & Simon, G. E. (2016). Racial-ethnic differences in psychiatric diagnoses and treatment across 11 health care systems in the Mental Health Research Network. Psychiatric Services, 67(7), 749–757. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500217

Consumer Healthcare Products Association. (n.d.). OTC sales statistics. https://chpa.org/about-consumer-healthcare/research-data/otc-use-statistics

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2016-Standards-with-citations.pdf

Crawford, S. Y., & Leventis, C. (2005). Herbal product claims: Boundaries of marketing and science. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(7), 432–436. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760510631183

Crighton, E., Coghlan, M. L., Farrington, R., Hoban, C. L., Power, M. W. P., Nash, C., Mullaney, I., Byard, R. W., Trengove, R., Musgrave, I. F., Bunce, M., & Maker, G. (2019). Toxicological screening and DNA sequencing detects contamination and adulteration in regulated herbal medicines and supplements for diet, weight loss and cardiovascular health. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 176, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2019.112834

Culpepper, L., & Wingertzahn, M. A. (2015). Over-the-counter agents for the treatment of occasional disturbed sleep or transient insomnia: A systematic review of efficacy and safety. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 17(6). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.15r01798

Darkovska-Serafimovska, M., Serafimovska, T., Arsova-Sarafinovska, Z., Stefanoski, S., Keskovski, Z., & Balkanov, T. (2018). Pharmacotherapeutic considerations for use of cannabinoids to relieve pain in patients with malignant diseases. Journal of Pain Research, 11, 837–842. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S160556

de Sousa Lima, C. M., Fujishima, M. A. T., de Paula Lima, B., Mastroianni, P. C., de Sousa, F. F. O., & da Silva, J. O. (2020). Microbial contamination in herbal medicines: A serious health hazard to elderly consumers. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies, 20(1), 17.

Disch, L., Drewe, J., & Fricker, G. (2017). Dissolution testing of herbal medicines: Challenges and regulatory standards in Europe, the United States, Canada, and Asia. Dissolution Technologies, 24, 6–12.

https://doi.org/10.14227/DT240217P6

Durso, G. R. O., Luttrell, A., & Way, B. M. (2015). Over-the-counter relief from pains and pleasures alike: Acetaminophen blunts evaluation sensitivity to both negative and positive stimuli. Psychological Science, 26(6), 750–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615570366

Erland, L. A. E., & Saxena, P. K. (2017). Melatonin natural health products and supplements: Presence of serotonin and significant variability of melatonin content. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(2), 275–281. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6462

First, M. B. (2013). DSM-5® handbook of differential diagnosis. American Psychiatric Association.

Flynn, A., Lincoln, J., & Burke, M. (2016). Homicidality and psychosis caused by an over-the-counter performance-enhancing supplement containing dendrobium extract and L-dopa. Pharmacy & Therapeutics, 41(6), 381–384.

Foong, A.-L., Patel, T., Kellar, J., & Grindrod, K. A. (2018). The scoop on serotonin syndrome. Canadian Pharmacists Journal/Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada, 151(4), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1715163518779096

Freudenberg-Hua, Y., Kaufman, R., Alafris, A., Mittal, S., Kremen, N., & Jakobson, E. (2019). Medication nonadherence in the geriatric psychiatric population: Do seniors take their pills? In V. Fornari & I. Dancyger (Eds.), Psychiatric nonadherence: A solutions-based approach (pp. 81–99). Springer.

Gerace, E., Bakanova, S. P., Di Corcia, D., Salomone, A., & Vincenti, M. (2021). Determination of cannabinoids in urine, oral fluid and hair samples after repeated intake of CBD-rich cannabis by smoking. Forensic Science International, 318, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110561

Gibson, T. B., Ozminkowski, R. J., & Goetzel, R. Z. (2005). The effects of prescription drug cost sharing: A review of the evidence. The American Journal of Managed Care, 11(11), 730–740.

Gruenwald, J., Brendler, T., & Jaenicke, C. (2007). PDR for herbal medicines (4th ed.). Thomson Healthcare.

Gureje, O., Nortje, G., Makanjuola, V., Oladeji, B. D., Seedat, S., & Jenkins, R. (2015). The role of global traditional and complementary systems of medicine in the treatment of mental health disorders. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(2), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00013-9

Guzmán Gutierrez, S. L., Reyes Chilpa, R., & Bonilla Jaime, H. (2014). Medicinal plants for the treatment of “nervios”, anxiety, and depression in Mexican traditional medicine. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia, 24(5), 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjp.2014.10.007

Hashiguchi, M., Ohta, Y., Shimizu, M., Maruyama, J., & Mochizuki, M. (2015). Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of Ginkgo biloba extract for the treatment of dementia. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Care and Sciences, 1(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40780-015-0014-7

He, S.-M., Chan, E., & Zhou, S.-F. (2011). ADME properties of herbal medicines in humans: Evidence, challenges and strategies. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 17(4), 357–407. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161211795164194

Hellbom, E. (2006). Chlorpheniramine, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and over-the-counter (OTC) treatment. Medical Hypotheses, 66(4), 689–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2005.12.006

Hendrickson, B. P., Shaikh, N., Occhiogrosso, M., & Penzner, J. B. (2016). Mania induced by Garcinia cambogia: A case series. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 18(2). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.15l01890

Hoskins, D., & Padrón, E. (2018). The practice of Curanderismo: A qualititative study from the perspectives of Curandera/os. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 6(2), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000081

Ingersoll, R. E. (2005). Herbaceuticals: An overview for counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83(4), 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00365.x

Ingersoll, R. E., & Rak, C. F. (2016). Psychopharmacology for mental health professionals: An integrative approach (2nd ed.). Cengage.

Julius, R. J., Novitsky, M. A., Jr., & Dubin, W. R. (2009). Medication adherence: A review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 15(1), 34–44.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000344917.43780.77

Kaufman, D. W., Kelly, J. P., Rosenberg, L., Anderson, T. E., & Mitchell, A. A. (2002). Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States: The Slone survey. JAMA, 287(3), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.3.337

Kaut, K. (2011). Psychopharmacology and mental health practice: An important alliance. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 33(3), 196–222. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.33.3.u357803u508r4070

Kaut, K. P., & Dickinson, J. A. (2007). The mental health practitioner and psychopharmacology. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 29(3), 204–225. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.29.3.t670636302771120

Kladar, N., Anačkov, G., Srđenović, B., Gavarić, N., Hitl, M., Salaj, N., Jeremić, K., Babović, S., & Božin, B. (2020). St. John’s wort herbal teas – Biological potential and chemometric approach to quality control. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 75, 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-020-00823-1

LaFrance, W. C., Lauterbach, E. C., Coffey, C. E., Salloway, S. P., Kaufer, D. I., Reeve, A., Royall, D. R., Aylward, E., Rummans, T. A., & Lovell, M. R. (2000). The use of herbal alternative medicines in neuropsychiatry: A report of the ANPA Committee on Research. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 12(2), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12.2.177

Liao, Z., Cheng, L., Li, X., Zhang, M., Wang, S., & Huo, R. (2020). Meta-analysis of Ginkgo biloba preparation for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical Neuropharmacology, 43(4), 93–99.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01605.x

Liu, Y., Lund, J. A., Murch, S. J., & Brown, P. N. (2018). Single-lab validation for determination of kavalactones and flavokavains in Piper methysticum (Kava). Planta Medica, 84(16), 1213–1218.

https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0637-2400

Macneil, C. A., Hasty, M. K., Conus, P., & Berk, M. (2012). Is diagnosis enough to guide interventions in mental health? Using case formulation in clinical practice. BMC Medicine, 10, Article 111.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-10-111

Makaryus, A. N., & Friedman, E. A. (2005). Patients’ understanding of their treatment plans and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 80(8), 991–994. https://doi.org/10.4065/80.8.991

Millar, S. A., Stone, N. L., Bellman, Z. D., Yates, A. S., England, T. J., & O’Sullivan, S. E. (2019). A systematic review of cannabidiol dosing in clinical populations. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 85(9), 1888–1900. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14038

Mischkowski, D., Crocker, J., & Way, B. M. (2016). From painkiller to empathy killer: Acetaminophen (paracetamol) reduces empathy for pain. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(9), 1345–1353. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsw057

Mischkowski, D., Crocker, J., & Way, B. M. (2019). A social analgesic? Acetaminophen (paracetamol) reduces positive empathy. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 538. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00538

Mischoulon, D., & Fava, M. (2002). Role of S-adenosyl-L-methionine in the treatment of depression: A review of the evidence. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76(5), 1158–1161. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/76.5.1158S

Modoux, M., Rolhion, N., Mani, S., & Sokol, H. (2020). Tryptophan metabolism as a pharmacological target. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 42(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2020.11.006

Mulyawan, E., Ahmad, M. R., Islam, A. A., Massi, M. N., Hatta, M., & Arif, S. K. (2020). Analysis of GABRB3 protein level after administration of valerian extract (Valeriana officinalis) in BALB/c mice. Pharmacognosy Journal, 12(4), 821–827. https://doi.org/10.5530/pj.2020.12.118

Murray, C. E., & Murray, T. L., Jr. (2007). The family pharm: An ethical consideration of psychopharmacology in couple and family counseling. The Family Journal, 15(1), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480706294123

Nahin, R. L., Barnes, P. M., Stussman, B. J., & Bloom, B. (2009). Costs of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and frequency of visits to CAM practitioners: United States, 2007. National Health Statistics Reports, 18, 1–14. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11548

National Institute of Mental Health. (2019). Prevalence of any mental illness (AMI). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml

Newmaster, S. G., Grguric, M., Shanmughanandhan, D., Ramalingam, S., & Ragupathy, S. (2013). DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products. BMC Medicine, 11(1), 222. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-222

Ng, C. H., & Bousman, C. A. (2018). Cross-cultural psychopharmacotherapy. In D. Bhugra & K. Bhui (Eds.), Textbook of cultural psychiatry (2nd ed., pp. 432–441). Cambridge University Press.

Ng, Q. X., Venkatanarayanan, N., & Ho, C. Y. X. (2017). Clinical use of Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) in depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 211–221.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.048

Olsufka, W., & Abraham, M.-A. (2017). Treatment-emergent hypomania possibly associated with over-the-counter supplements. Mental Health Clinician, 7(4), 160–163. https://doi.org/10.9740/mhc.2017.07.160

Pantano, F., Tittarelli, R., Mannocchi, G., Zaami, S., Ricci, S., Giorgetti, R., Terranova, D., Busardò, F. P., & Marinelli, E. (2016). Hepatotoxicity induced by “the 3Ks”: Kava, kratom and khat. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17(4), 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17040580

Papakostas, G. I. (2009). Evidence for S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM-e) for the treatment of major depressive disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70(Suppl. 5), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.8157su1c.04

Perry, P. J., Alexander, B., Liskow, B. I., & DeVane, C. L. (2006). Psychotropic drug handbook (8th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Phillips, L. A., Cohen, J., Burns, E., Abrams, J., & Renninger, S. (2016). Self-management of chronic illness: The role of ‘habit’ versus reflective factors in exercise and medication adherence. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(6), 1076–1091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9732-z

Posadzki, P., Watson, L., & Ernst, E. (2013). Contamination and adulteration of herbal medicinal products (HMPs): An overview of systematic reviews. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 69(3), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-012-1353-z

Preston, J. D., O’Neal, J. H., Talaga, M. C., & Moore, B. A. (2021). Handbook of clinical psychopharmacology for therapists (9th ed.). New Harbinger.

PR Newswire. (n.d.). Global over-the-counter drug markets hit $80.2 billion in 2017: Report. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-over-the-counter-drug-markets-hit-802-billion-in-2017-report-300588867.html

Professional Counselors, 22 Texas Administrative Code § 681.83 (2021). https://texreg.sos.state.tx.us/public/readtac$ext.ViewTAC?tac_view=5&ti=22&pt=30&ch=681&sch=C&rl=Y

Rashrash, M., Schommer, J. C., & Brown, L. M. (2017). Prevalence and predictors of herbal medicine use among adults in the United States. Journal of Patient Experience, 4(3), 108–113.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373517706612

Ravina, E. (2011). The evolution of drug discovery: From traditional medicines to modern drugs. Wiley.

Ravven, S. E., Zimmerman, M. B., Schultz, S. K., & Wallace, R. B. (2011). 12-month herbal medicine use for mental health from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 23(2), 83–94.

Sakurai, H., Carpenter, L. L., Tyrka, A. R., Price, L. H., Papakostas, G. I., Dording, C. M., Yeung, A. S., Cusin, C., Ludington, E., Bernard-Negron, R., Fava, M., & Mischoulon, D. (2020). Dose increase of S-adenosyl-methionine and escitalopram in a randomized clinical trial for major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 262, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.040

Saran, J. S., Barbano, R. L., Schult, R., Wiegand, T. J., & Selioutski, O. (2017). Chronic diphenhydramine abuse and withdrawal: A diagnostic challenge. Neurology: Clinical Practice, 7(5), 439–441.

https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000304

Sarris, J. (2007). Herbal medicines in the treatment of psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. Phytotherapy Research, 21(8), 703–716. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.2187

Sarris, J. (2018). Herbal medicines in the treatment of psychiatric disorders: 10-year updated review. Phytotherapy Research, 32(7), 1147–1162. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6055

Savage, K., Firth, J., Stough, C., & Sarris, J. (2018). GABA-modulating phytomedicines for anxiety: A systematic review of preclinical and clinical evidence. Phytotherapy Research, 32(1), 3–18.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5940

Savage, R. A., Basnet, S., & Miller, J. M. (2020). Melatonin. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534823

Scotton, W. J., Hill, L. J., Williams, A. C., & Barnes, N. M. (2019). Serotonin syndrome: Pathophysiology, clinical features, management, and potential future directions. International Journal of Tryptophan Research, 12, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178646919873925

Sepulveda, V. I., Piazza, N. J., Devlin, M., Ritchie, M. H., Salyers, K., & Tucker-Gail, K. (2016). Psychopharmacology in counseling, psychology, and social work education: An interdisciplinary history and implications for professional counselors. Wisconsin Counseling Association Journal, 29, 35–48.

Sharma, V., Madaan, R., Bala, R., Goyal, A., & Sindhu, R. K. (2021). Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions of herbs with prescribed drugs: A review. Plant Archives, 21(1), 185–198.

https://doi.org/10.51470/PLANTARCHIVES.2021.v21.S1.033

Shinjyo, N., Waddell, G., & Green, J. (2020). Valerian root in treating sleep problems and associated disorders—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine, 25, 1–31.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2515690X20967323

Sidhu, G., & Marwaha, R. (2021). Phenelzine. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554508

Singh, P., Srivastava, B., Kumar, A., & Dubey, N. K. (2008). Fungal contamination of raw materials of some herbal drugs and recommendation of Cinnamomum camphora oil as herbal fungitoxicant. Microbial Ecology, 56(3), 555–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-008-9375-x

Singh, S. K., Srivastav, S., Castellani, R. J., Plascencia-Villa, G., & Perry, G. (2019). Neuroprotective and antioxidant effect of Ginkgo biloba extract against AD and other neurological disorders. Neurotherapeutics, 16(3), 666–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-019-00767-8

Smith, T., Kawa, K., Eckl, V., Morton, C., & Stredney, R. (2017). Herbal supplement sales in US increase 7.7% in 2016: Consumer preferences shifting toward ingredients with general wellness benefits, driving growth of adaptogens and digestive health products. HerbalGram, 115, 56–65. https://www.herbalgram.org/media/15603/hg115-mktrpt.pdf

Solas, M., Puerta, E., & Ramirez, M. J. (2015). Treatment options in Alzheimer’s disease: The GABA story. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 21(34), 4960–4971. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612821666150914121149

Spindle, T. R., Cone, E. J., Kuntz, D., Mitchell, J. M., Bigelow, G. E., Flegel, R., & Vandrey, R. (2020). Urinary pharmacokinetic profile of cannabinoids following administration of vaporized and oral cannabidiol and vaporized CBD-dominant cannabis. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 44(2), 109–125.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkz080

Stahl, S. M. (2021). Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific basis and practical applications (5th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Surana, A. R., Agrawal, S. P., Kumbhare, M. R., & Gaikwad, S. B. (2021). Current perspectives in herbal and conventional drug interactions based on clinical manifestations. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 7(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43094-021-00256-w

Tallarida, R. J. (2007). Interactions between drugs and occupied receptors. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 113(1), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.08.002

Tran, T., & Kavuluru, R. (2020). Social media surveillance for perceived therapeutic effects of cannabidiol (CBD) products. International Journal of Drug Policy, 77, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102688

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Quick facts [Table]. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2015). FDA 101: Dietary supplements. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/fda-101-dietary-supplements

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2020a). FDA approves new indication for drug containing an active ingredient derived from cannabis to treat seizures in rare genetic disease. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-indication-drug-containing-active-ingredient-derived-cannabis-treat-seizures-rare

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2020b). What you need to know (and what we’re working to find out) about products containing cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds, including CBD. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/what-you-need-know-and-what-were-working-find-out-about-products-containing-cannabis-or-cannabis

Wang, C.-C., Kennedy, J., & Wu, C.-H. (2015). Alternative therapies as a substitute for costly prescription medications: Results from the 2011 National Health Interview Survey. Clinical Therapeutics, 37(5), 1022–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.01.014

Wolf, M. S., King, J., Jacobson, K., Di Francesco, L., Bailey, S. C., Mullen, R., McCarthy, D., Serper, M., Davis, T. C., & Parker, R. M. (2012). Risk of unintentional overdose with non-prescription acetaminophen products. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(12), 1587–1593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2096-3

Wong, M. K., Darvishzadeh, A., Maler, N. A., & Bota, R. G. (2016). Five supplements and multiple psychotic symptoms: A case report. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 18(1).

https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.15br01856

Wu, C.-H., Wang, C.-C., & Kennedy, J. (2011). Changes in herb and dietary supplement use in the US adult population: A comparison of the 2002 and 2007 National Health Interview Surveys. Clinical Therapeutics, 33(11), 1749–1758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.09.024

Zirak, N., Shafiee, M., Soltani, G., Mirzaei, M., & Sahebkar, A. (2019). Hypericum perforatum in the treatment of psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders: Current evidence and potential mechanisms of action. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 234(6), 8496–8508. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.27781

Sabina Remmers de Vries, PhD, NCC, LPC-S, is an associate professor at Texas A&M University–San Antonio. Christine D. Gonzales-Wong, PhD, NCC, LPC, is an assistant professor at Texas A&M University–San Antonio. Correspondence may be addressed to Sabina de Vries, One University Way, San Antonio, TX 78224, sabina.devries@tamusa.edu.

Aug 10, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 2

Phillip L. Waalkes, Daniel A. DeCino, Maribeth F. Jorgensen, Tiffany Somerville

Supportive relationships with counselor educators as dissertation chairs are valuable to doctoral students overcoming barriers to successful completion of their dissertations. Yet, few have examined the complex and mutually influenced dissertation-chairing relationships from the perspective of dissertation chairs. Using hermeneutic phenomenology, we interviewed counselor educators (N = 15) to identify how they experienced dissertation-chairing relationship dynamics with doctoral students. Counselor educators experienced relationships characterized by expansive connections, growth in student autonomy, authenticity, safety and trust, and adaptation to student needs. They viewed chairing relationships as fluid and non-compartmentalized, which cultivated mutual learning and existential fulfillment. Our findings provide counselor educators with examples of how empathy and encouragement may help doctoral students overcome insecurities and how authentic and honest conversations may help doctoral students overcome roadblocks. Counselor education programs can apply these findings by building structures to help facilitate safe and trusting relationships between doctoral students and counselor educators.

Keywords: dissertation-chairing relationships, hermeneutic phenomenology, counselor education, doctoral students, relationship dynamics

According to the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2015), doctoral students must develop research skills and complete counseling-focused dissertation research. Research mentorship is often important to counselor education doctoral students’ development as researchers (Flynn et al., 2012; Lamar & Helm, 2017; Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015). One of the central research mentoring relationships in doctoral programs is the dissertation-chairing relationship. Supportive research mentoring relationships in counselor education are invaluable to students (Lamar & Helm, 2017), are necessary to successful dissertation chairing (Ghoston et al., 2020; Jorgensen & Wester, 2020), and are a central factor in high-quality doctoral programs (Preston et al., 2020). In fact, a meaningful connection between students and their dissertation chairperson predicts students’ successful completion of their dissertations (Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015; Rigler et al., 2017) and positive dissertation experiences (Burkard et al., 2014). Therefore, to help promote intentional and supportive dissertation-chairing relationships, we examined counselor educators’ experiences of relationship dynamics with doctoral students.

Challenges in Dissertation Completion

Across disciplines, doctoral students can struggle with isolation, motivation, time management, self-regulation, and self-efficacy (Pyhältö et al., 2012). In their development as researchers, doctoral students in counselor education can experience intense emotions, including excitement, exhaustion, frustration, distrust, confusion, disconnection, and pride (Lamar & Helm, 2017). Negative relationships with dissertation chairs can exacerbate challenges to dissertation completion. In one meta-analysis study examining doctoral student attrition across disciplines, doctoral students identified a problematic relationship with their dissertation chairperson as the most significant barrier to their completion of their degrees (Rigler et al., 2017). Doctoral students in counselor education have reported negative experiences when their dissertation chairs were unenthusiastic, unsupportive, and unavailable, and when their guidance was not concrete (Flynn et al., 2012; Lamar & Helm, 2017). In addition, counselor education doctoral students involved in negative dissertation-chairing relationships can feel like they are on their own in their dissertation journeys (Protivnak & Foss, 2009). This feeling of isolation can intensify existing barriers in completing dissertations, including struggles with motivation, self-regulation, self-criticism, and self-efficacy (Burkard et al., 2014; Pyhältö et al., 2012).

Power differentials between doctoral students and dissertation chairs also can serve as a barrier to supportive dissertation-chairing relationships and dissertation completion (Burkard et al., 2014). For example, doctoral students are likely to remain silent in difficult relationships with dissertation chairs unless students perceive there to be a strong relationship built on respect and open communication (Schlosser et al., 2003). Cultural differences and systemic oppression may also impact dissertation-chairing relationships. According to Brown and Grothaus (2019), Black counselor education students can experience overt racism, tokenism, isolation, and internalized racism, which can foster mistrust in cross-racial mentoring relationships. Numerous researchers in counselor education (Borders et al., 2012; Ghoston et al., 2020; Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015; Purgason et al., 2018) have recommended mentors use transparent and honest dialogue with explicit attention to expectations, power dynamics, cultural differences, and potential conflicts.

Supportive Dissertation-Chairing Relationships