Unraveling Overcontrolled and Undercontrolled Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: A Grounded Theory

Sara E. Ellison, Jill M. Meyer, Julia Whisenhunt, Jessica Meléndez Tyler

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) has historically been associated with deficits in impulse control; however, evidence suggests that individuals high in self-control also self-injure. This constructivist grounded theory study aimed to explore the nature of undercontrolled and overcontrolled self-injury to fill gaps in the literature and to improve clinical understanding and treatment. The resulting Theory of Overcontrolled and Undercontrolled Self-Injury provides a preliminary understanding of the mechanisms that guide overcontrolled and undercontrolled NSSI, the processes that can facilitate individuals switching profiles, and the processes that lead to cessation of self-injurious behavior, thereby contributing to the development of more comprehensive theories of self-harm. Additionally, clinical implications for developing assessments and interventions aimed at preventing and treating NSSI are discussed.

Keywords: nonsuicidal self-injury, self-control, undercontrolled, overcontrolled, self-harm

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the act of intentional, self-inflicted damage of body tissue without the intent to end one’s life and for purposes not socially or culturally sanctioned (Klonsky et al., 2014). NSSI takes many forms including cutting, scratching, piercing, or burning the skin; preventing wounds from healing; and head banging (Favazza, 2011). The functions of NSSI vary considerably between individuals; however, commonly endorsed reasons are emotion regulation, self-punishment, relief from dissociation, and the communication of psychological pain (Doyle et al., 2017; Edmondson et al., 2016).

NSSI affects individuals across the lifespan, but onset frequently begins in adolescence (Brager-Larsen et al., 2022). Prevalence rates in community samples suggest that approximately one in five individuals report a history of self-injury (Andover, 2014; Giordano et al., 2023). Clinically, NSSI is a frequent presenting concern; 97.9% of licensed clinicians reported working with NSSI at some point during their careers (Giordano et al., 2020). Despite this, counselors often experience anxiety and self-doubt when working with clients who self-injure (Whisenhunt et al., 2014), perhaps in part because of the limited scholarly resources available to guide intervention.

NSSI has historically been linked with impulse control problems, largely because of its association with borderline personality disorder (BPD; Hamza et al., 2015). However, recent meta-analyses examining NSSI and impulsivity have produced mixed findings (Hamza et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). One study examined the degree of impulsivity and found that 77% of participants waited an average of 15 minutes or less between NSSI thought and action (Glenn & Klonsky, 2010). A positive relationship was also found between the frequency of NSSI and lack of premeditation and perseverance. However, no differences in inhibitory control function were found between individuals who self-injured and those who did not. Before its recent classification as a condition for further study in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013), NSSI appeared only once in the manual, as a symptom of BPD.

Undercontrol and Overcontrol

Self-control is a multidimensional construct that encompasses the ability to regulate behavior following social norms, moral standards, and long-term goals (Baumeister & Heatherton, 1996). Self-control has been linked to numerous positive outcomes, including superior academic performance, well-being, and relationships (Hofmann et al., 2014; Tangney et al., 2004). However, although many theorists (e.g., Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999; Tangney et al., 2004) posit that high levels of self-control are invariably advantageous, some have argued that the relationship between self-control and well-being is curvilinear, with both the highest and lowest levels of self-control capacity being maladaptive (Block & Block, 1980; Lynch et al., 2015).

Although research on overcontrol (OC; i.e., the excessive presence of self-control) is limited, maladaptive overcontrol is not new. Block and Block developed a theory that focused on individual differences in impulse control, which varies from undercontrol to overcontrol (Block, 2002; Block & Block, 1980). Undercontrolled (UC) individuals struggle with impulse and emotion regulation, exhibiting spontaneity, impulsivity, emotional variability, disregard for social norms, and indifference to ambiguity. In contrast, overcontrolled individuals excessively inhibit their impulses and expressions, which is characterized by emotional restraint, dependability, high organization, and an unnecessary delay of gratification or denial of pleasure. More recently, Lynch (2018) proposed a transdiagnostic model of disorders of overcontrol in conjunction with the development of Radically Open Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (RO DBT). This model suggests that although overcontrolled individuals often achieve measurable success, they frequently experience pervasive loneliness and psychological distress.

Undercontrolled and Overcontrolled NSSI

NSSI has historically been associated with deficits in impulse control (Glenn & Klonsky, 2010); however, evidence suggests that individuals high in self-control also self-injure (Claes et al., 2012; Hempel et al., 2018). Hempel et al. (2018) found that self-injurious behavior in undercontrolled individuals is typically impulsive, emotionally driven, and may involve others. In contrast, overcontrolled individuals tend to engage in planned, rule-governed, and secretive self-injury. Although this study offers compelling evidence of differing self-injurious behaviors based on undercontrol and overcontrol, further research is needed to fully understand these differences.

Purpose of the Study

Despite extensive research on NSSI, much remains to be understood about this behavior. The inclusion of NSSI as a condition for further study in the latest DSM revision (APA, 2022) underscores the need for more research to refine diagnostic criteria and clinical interventions. Significant research has yet to focus on NSSI within the frameworks of undercontrol and overcontrol. Thus, our study aimed to develop a theory about undercontrolled and overcontrolled self-injury in order to fill existing gaps in the literature and to enhance clinical understanding and treatment. Our research question was: What are the experiences, attitudes, and behaviors related to undercontrolled and overcontrolled self-injury?

Method

We selected a constructivist grounded theory approach, which seeks to offer explanations about a phenomenon from the perspective of those who experience it (Charmaz, 2014). This inductive approach facilitates the construction of a theoretical model that systematically describes processes associated with the phenomenon of interest (Charmaz, 2014) and, therefore, is well-suited to helping counselors understand their clients’ experiences and behaviors (Hays & Singh, 2023). Constructivist methodology holds the ontological position that our world is socially constructed through interactions over time; therefore, the researchers and participants are co-creators of knowledge (Charmaz, 2014).

Researcher Reflexivity

Reflexivity is essential if researchers’ experiences and interpretations influence the grounded theories they construct (Charmaz, 2014). Sara E. Ellison is a White cisgender woman, a doctoral student, and a licensed professional counselor (LPC). She has experience working with clients who self-injure in residential and outpatient settings, which sparked her interest in the differences in undercontrolled and overcontrolled NSSI. This clinical experience and her training in dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and RO DBT influenced the expectation that UC NSSI would align with characteristics such as impulsivity, emotionality, and openness, and that OC NSSI would align with planning, inhibited emotion, and secretiveness. Jill M. Meyer is a White cisgender woman, a professor and Director of Counselor Education at a CACREP-accredited R1 university, and an LCPC. Her education, training, and clinical experiences are outside of this topic area, positioning her to be objective in the study of NSSI. She approached this research with curiosity about whether OC and UC NSSI would reflect characteristics previously described in the literature on OC and UC.

Julia Whisenhunt is a White, cisgender woman and a professor at a regional comprehensive university with a CACREP-accredited program. She is an LPC and a certified professional counselor supervisor who specializes in crisis intervention and has studied NSSI for approximately 15 years. Based on her work with clients who self-injure and her prior research and scholarship on the topic, she entered with core assumptions about NSSI that may have contributed to her conceptualization of the data. Whisenhunt believes that NSSI most often serves as a coping skill for intense intrapersonal experiences (e.g., self-loathing, despair, anger, fear, shame, anxiety, dissociation) and is best treated through a person-centered approach. Jessica Meléndez Tyler is a Latina cisgender woman and a faculty member at a CACREP-accredited R1 institution. She is a licensed counseling supervisor with 15 years of experience working with at-risk adults in outpatient settings. Tyler’s clinical experiences have deepened her understanding of the complexities of NSSI, driving her commitment to advancing knowledge and interventions in this area. She approached this research with the assumption that UC and OC play a significant role in NSSI and that effective and humanistic therapeutic interventions can improve the quality of life for affected individuals. Our values of empathy, compassion, and a nonjudgmental approach to behaviors that have often been misunderstood by the public guided our interpretation of the data, aiming to view NSSI through a lens of human complexity rather than pathology.

This research was completed as a dissertation study with Ellison receiving support and guidance from the other authors throughout the research process. Ellison conducted intensive interviews and coding, with Meyer and Whisenhunt advising and supporting the consideration of multiple perspectives. We met eight times during data collection and analysis, during which we reviewed emerging codes, participant narratives, and developing theory. We also engaged in reflexivity exercises and triangulated the findings with existing NSSI scholarship. Tyler assisted with study conceptualization and manuscript development.

Participants and Procedures

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we used purposeful criterion sampling and theoretical sampling to recruit participants (Timonen et al., 2018). Selection criteria included adults who had self-injured five or more times in their lifetime and self-identified as undercontrolled or overcontrolled. Although qualitative research on NSSI often includes individuals with any NSSI experience (e.g., Hambleton et al., 2022), we chose to recruit those with significant NSSI histories to better understand their behavioral, emotional, and cognitive patterns. This is consistent with previous qualitative research including those who have self-injured five to six times in their lifetime (da Cunha Lewin et al., 2024; Kruzan & Whitlock, 2019).

It is recommended that researchers screen participants for vulnerabilities and balance the need for rich data with potential harm when asking sensitive questions (Hays & Singh, 2023); therefore, we conducted a literature review to assess the potential iatrogenic effects and benefits related to participating in interviews broaching NSSI. Researchers have viewed self-injury in the context of the transtheoretical stages of change model and suggested that individuals enter the termination stage after 3 years of abstinence from NSSI behavior (Kruzan et al., 2020). Previous studies (Muehlenkamp et al., 2015; Whitlock et al., 2013) have indicated that participating in detailed NSSI research did not have significant adverse effects; however, to minimize risk, participant eligibility for the study was based on the absence of any current suicidal ideation and no self-injury in the past 3 years.

In order to reach individuals with meaningful self-injury experience, we posted a recruitment flyer in four Facebook and Reddit support groups related to self-injury. We also emailed calls for participation to experts in the field and shared them on listservs, including Counselor Education and Supervision Network, Georgia Therapist Network, and Radically Open DBT Listserv. Participants received a $25 e-gift card as compensation for their time and contributions.

The 20 study participants all self-identified as undercontrolled (UC; n = 10, 50%) or overcontrolled (OC; n = 10; 50%) as described by Block and Block (1980). Most participants identified as White or Caucasian (n = 14, 70%), with three identifying as Multi-Racial (15%), two identifying as African American and/or Black (10%), and one identifying as Hispanic or Latino/a/x (5%). Likewise, most participants identified as women (n = 18, 90%), with one identifying as a nonbinary woman (5%) and one identifying as a man (5%). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 43, with the mean age being 29.4. The participants lived in various geographic regions, with the most common region being the South (n = 12, 60%), followed by the Midwest (n = 4, 20%), Northeast (n = 2, 10%), and West (n = 2, 10%). We ceased recruiting participants once we achieved comprehensive coverage of emerging categories and new data no longer provided theoretical insights (Charmaz, 2014).

Data Collection

After identifying eligible participants via a screening and demographic questionnaire, Ellison conducted intensive, semi-structured Zoom interviews, each lasting about 60 minutes. The researchers developed the interview protocol after reviewing current qualitative literature and assessment measures on NSSI and consulting with two NSSI subject matter experts with significant qualitative research experience (see Appendix for complete interview protocol). Intensive interviewing relies on the practice of following up on unanticipated areas of inquiry prompted by emerging data (Timonen et al., 2018); therefore, after several participants mentioned their reactions to NSSI in peers or media representations, a question related to perception of others’ NSSI was integrated into subsequent interviews. Participants chose pseudonyms in order to protect their identities; all interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Participants were then invited to review their transcripts and make any revisions, redactions, or additions to ensure the accuracy of their voices and experiences.

Data Analysis

Ellison conducted initial coding by labeling data segments to summarize and categorize them. Transcripts were repeatedly read and analyzed as new data were collected to identify similarities and differences in participant narratives. Focused coding then aimed to refine the most salient codes into categories and themes in order to develop a larger theory (Charmaz, 2014). During this phase, Ellison condensed the 38 initial codes into concise descriptions encapsulating participants’ narratives, resulting in 15 themes that explained the relationships between findings. This process moved the analysis from descriptive to conceptual, guiding theory development (Charmaz, 2014). Ellison, Meyer, and Whisenhunt met multiple times to review the developing codebook, connect data, and clarify theory development.

Constant comparative methods (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) were used throughout coding to identify patterns and to ground the theory in participant narratives. Memo writing recorded analytic ideas for later follow-up. Data and codes were organized using Dedoose, a HIPAA-compliant, password-protected online qualitative software. After reaching theoretical saturation we conducted member checks by emailing participants a summary of themes and categories to solicit feedback. All 20 participants confirmed that the emerging theory aligned with their experiences.

Trustworthiness Strategies

Several strategies were employed to enhance rigor and mitigate methodological limitations in this qualitative study. Participant perspectives and the investigated phenomenon’s authenticity are crucial for the study’s validity (Denzin et al., 2023). Member checking was consistently used during data collection and analysis, enabling participants to confirm the relevance of findings to their experiences. Follow-up questions were integrated into interviews to clarify participant responses (Hays & Singh, 2023) and participants reviewed their interview transcripts and initial findings to provide feedback (Charmaz, 2014). Five participants contributed additional insights, enriching the theoretical framework with their unique perspectives. Researcher reflexivity was employed to acknowledge personal beliefs, values, and biases that might influence data interpretation (Hays & Singh, 2023), addressing reactions to participants, insights into potential findings, and adjustments made to the research process.

Findings

The findings of this grounded theory analysis describe the experiences, attitudes, and behaviors related to OC and UC NSSI, including the processes that can facilitate individuals switching profiles and the processes that lead to the cessation of self-injurious behavior.

OC NSSI

Restrained

OC NSSI was associated with high levels of restraint, which allowed participants to mask negative emotions, delay self-injury, and moderate how deeply they cut. Motivated by the highly private nature of OC NSSI, participants often postponed their self-injury for several hours or more to keep it hidden. This time was frequently used to plan when, where, and how self-injury might occur. Emma described this:

There were definitely times where maybe something would happen like at school. Or somewhere out in public or something like that. Where I knew that . . . because I was extremely secretive about what I was doing, that I maybe thought, “well, later I might go home and do that.” I can’t remember ever thinking to myself, “well, I need to go home right now and cut,” you know? That was never crossing my mind.

Participants also used restraint during the behavior, cutting deeply enough to feel relief but not so severely that it resulted in medical attention or attention from others. Jenny shared:

When I was cutting . . . I had to really pay attention. Really focus, laser focus, to not do something wrong or not cause more grievous harm or also to sort of maintain some pain, but maybe not too much pain, not go too deep.

Participants expressed a sense of pride in their ability to utilize restraint related to OC NSSI, which contributed to their sense of identity and differentiated their behavior from impulsive conceptualizations of self-injury.

Highly Private

Participants were highly private about their OC NSSI, prompting them to avoid disclosure experiences, take great care to hide injuries and scars, and avoid medical attention. This desire to conceal their self-injury was often motivated by maintaining a specific image or not burdening others. Emma shared, “I didn’t want to be a burden to anyone or my pain to be a burden to anyone. And so that was my worst nightmare, for someone to know what was going on.” OC NSSI was seen as deeply personal and carried out solely for the benefit of participants. The highly private nature of OC NSSI influenced the location of participants’ self-injury as well as rules that would support keeping it hidden, as Madeline described:

I never . . . very rarely cut on my arms or like even my legs because I [was] training for triathlons and was swimming. And so a lot of it was like on my breasts, on like my pelvic area where it would never be seen.

The avoidance of medical care meant that some participants took responsibility for caring for severe wounds independently. Phoenix described learning to suture her wounds on YouTube. Rex instituted a disinfecting process after a cut on her leg became severely infected: “I didn’t want to end up in the hospital having to have somebody ask a question about [self-injury].” Even after the cessation of NSSI, participants were often reluctant to discuss the behavior. Jenny disclosed that her participation in this study represented more discussion about her self-injury than all her other disclosures combined. The private nature of participants’ OC NSSI made them less likely to seek help, including mental health care.

Guided by Rules and Ritual

Participants describing OC NSSI spoke of rules that dictated their use of specific tools, number of cuts, and locations on the body. Often, these rules were based on a compensatory approach to self-injury in which participants responded to specific wrongdoings or perceived failures with distinct approaches to self-punishment. These rules provided the scaffolding for behavior that became ritualistic. Participants described a structured, disciplined approach to self-injury that was often motivated by upholding established routines rather than emotional dysregulation or NSSI urges. Katie shared that her self-injury occurred nightly around the same time and in the same location: “There were nights where I didn’t really feel like I had like a lot of emotions. And it was more of that secret part of it, where I was keeping a routine. Like, ‘Well, time to go do this.’” Madeline adhered rigidly to the rules and ritual she had established for herself: “I’m not gonna stop. If I’ve decided this is gonna happen 113 times, I’m doing 113. Like, regardless of if I decide halfway through, I don’t wanna keep doing this.”

Participants also described ritualized aftercare, often involving an organized medical supply kit, which became a meaningful part of the self-injury process. In some cases this also involved photographing, writing about, or otherwise documenting their wounds. Phoenix shared that she “always stitched it up, or whatever. In the moment, it was something that was very destructive. But afterwards, it was always taken care of . . . maybe in a way, that was a way of kind of taking care of myself.” The rules and rituals associated with participants’ OC NSSI created order and structure in their lives. They imbued the behavior with meaning that elevated it beyond a simple emotion regulation tool.

Perception of Others’ NSSI as Inferior

Participants describing OC NSSI often expressed feeling as though their self-injury was superior to others’ and were highly judgmental of NSSI that they viewed as impulsive or not intentionally hidden. They eschewed the idea of their own NSSI as attention-seeking and felt a sense of pride in their ability to control their impulses and affect and meticulously hide their behavior. Katie shared, “I think I felt very judgmental of [others who self-injured], like, ‘How come you’re doing this to yourself and then sharing it to everybody?’ Like, ‘I can’t believe you’re using this to get attention and stuff like that.’”

These participants used words such as “correct,” “pious,” “better,” and “right” to describe the way they self-injured, positioning themselves as morally superior and intrinsically dissimilar from others who approached the behavior differently. Emma described this:

Pride is a strange word to describe it, but it was almost sort of like being more pious. It was like . . . I’m holding this big secret. I’m doing this thing, and that’s the way it should be. So I felt like I was doing it correctly.

Participants viewed their OC NSSI as different from what they saw around them, which contributed to both a sense of isolation and a feeling of pride.

Cessation—Loss of Utility and Defined Decision to Stop

Cessation of OC NSSI often occurred when the behavior lost its utility and followed a defined decision to stop. This pragmatic approach meant that once the benefits of self-injury waned, participants saw no reason to continue to engage with it, as Katie described:

I feel like I achieved what I wanted to achieve and now I don’t feel like doing it anymore . . . I remember going into therapy afterwards and thinking, “I don’t know why I’m here because like I don’t even feel these urges anymore. So . . . there’s no point.”

Although cessation experiences sometimes included counseling or other interventions, they often occurred independently, consistent with the highly private nature of OC NSSI.

Scaffolded by their ability to exercise restraint, participants rarely went back on their decision or experienced a lengthy cessation process. Katie stated, “I think that was another part of the control. Like I get to decide when I do this and how I do this and when I stop and stuff like that.” Lauri also identified a defined ending of her self-injurious behavior:

I actually got to a point where I was like, “Okay, I’m in my 30s now. This has like, you know, got to stop. Like, this is not okay.” But I actually went and got a tattoo as a marker that I’m not doing this anymore, and I haven’t.

The resoluteness with which they committed to their decision to stop often felt more salient than any distress they experienced because of cessation.

UC NSSI

Impulsive

UC NSSI was described as occurring in an impulsive and unplanned manner. Participants described an urgency to their self-injurious thoughts that motivated them to seek immediate relief, often within minutes of the decision to self-injure. Lauri stated that when she had an urge to self-injure, “It was kind of like a panic, like trying to get to it as soon as possible to get relief.” To facilitate this, some participants always carried self-injury tools with them. Others used whatever they could find nearby, even it was not their preferred instrument. If these participants delayed their self-injury, it was due to seeking favorable circumstances rather than planning or premeditation. Amy shared: “There wasn’t a premeditated like separate razor blade or anything. It was just, I knew where and when I could do it. And so if I got overwhelmed, I might go take a shower or something.” This impulsiveness sometimes contributed to disclosure experiences because participants could not inhibit their self-injury urges until they reached a private space, or their hastiness contributed to others’ suspicions.

Disclosed Despite Secrecy

UC NSSI was often disclosed despite participants’ desire for secrecy. Participants’ inability to delay their NSSI behavior or mask their emotions sometimes contributed to self-injuring with others present or in manners that were more likely to be discovered. Additionally, participants described conflicting feelings related to disclosure in which they often desired for others to know about their NSSI while simultaneously experiencing shame or embarrassment about the behavior. Rose described wanting to cut in places that could be covered, but also shared that she didn’t hide her self-injury from her friends:

I had a couple of really close friends at college, and I told one of them pretty early on, and that was voluntary . . . I don’t remember how I told the others or if I just said, “it’s okay if you tell the others.” But eventually, my friend group knew.

Lola described hiding her self-injury, but not so deliberately that it didn’t raise people’s suspicions: “I always wore long sleeves, which definitely I guess I could say my parents felt a little bit suspicious of when it was summertime and stuff.” Eventually, Lola’s mom became so suspicious that “she asked to look, and so I showed her, and she found out, and we had a conversation about it and everything.” Jane also shared conflicting thoughts related to disclosure. On one hand, she shared, “I would cut my arms mostly. And that was like a, ‘hey, I’m doing this,’ kind of thing.” At the same time, she remembered thinking:

This is embarrassing. I don’t really want people to know or ask me about it. But it was also like, in a place where like, sometimes I’d be in a t-shirt. So sometimes you would see it. Or sometimes people would notice.

Participants’ ambivalence about disclosure often resulted in inconsistent or disorganized concealment behaviors, making the discovery of their NSSI by others more likely.

Guided by Emotion

Emotion influenced when, where, and how UC NSSI occurred. Participants reported being highly responsive to their mood states and experiencing self-injury as a potent strategy to cope with dysregulation. Because they were typically unable or unwilling to inhibit their impulses, self-injurious behavior often occurred at the peak of emotional distress. Rose reported that “any negative feeling, but especially like guilt or regret [or] shame” might trigger an episode of self-injury, “so it was very much an emotional regulator.”

Pacey described the emotional intensity when he would self-injure: “Definitely [self-injury would occur] at the top. Sometimes I remember crying really hard when it was happening, or feeling so anxious that I was lightheaded. And the cutting would help bring that emotion down.” This connection between emotionality and UC NSSI meant that participants more frequently conceptualized their triggers as interpersonal, resulting from interactions that precipitated emotional distress.

Perception of Others’ NSSI as Superior or Relatable

If participants encountered peers that self-injured or media representations of NSSI, their view was often that others’ NSSI was superior or relatable. Participants sometimes described feeling that others’ self-injury was “cooler,” “better,” “brave,” or more “impactful” than their own and endorsed a desire to emulate this. Jane shared:

There was definitely a period of time where I would see people who maybe were self-injuring in a way that was more aggressive than I was doing it and definitely had some inferiority complex going on like, oh . . . mine’s not impactful . . . I felt like an imposter.

When Pacey joined online support groups, he “felt a lot of similarities to their stories . . . And it was nice to know that I wasn’t alone.” Even when participants identified a misalignment between others’ self-injurious behaviors and their own, they typically remained nonjudgmental and assumed that others were doing the best they could. Rose shared:

In the books I read, it was portrayed really sympathetically. Like, they’re struggling, and so are the friends [I knew that self-injured]. But somehow still, I got that idea of people do it for attention. But my personal experience from books and friends was just like, they’re having a hard time, and that’s the only way they can figure it out.

Participants’ view of others’ NSSI as superior or relatable influenced their willingness to engage in conversations with others who self-injured, further supporting their capacity to seek and receive help.

Cessation—Interpersonal Influence and Protracted Process of Stopping

Interpersonal influence (e.g., therapy or pressure from peers or family) contributed to the cessation of UC NSSI. Jasmine described the support from her inner circle as essential to her self-injury cessation. “They would encourage me to call one of them and just have them come over or have me go to the restroom or outside near a tree and just talk through what my emotions were telling me.” Amy also leaned on support from friends:

Having that friend that knew about it from freshman year that I lived with was also a help in not doing it again because I could go literally right next door to her room and kind of talk about how I was feeling for a second and sit on her floor and just let that feeling pass.

Rose shared that seeing a counselor twice weekly supported her in decreasing and ultimately stopping NSSI. Because participants frequently had already disclosed their UC NSSI, interpersonal support was more likely to be available and, therefore, influential to cessation.

Participants also highlighted the lengthy process of stopping their self-injury. Tricia recalled gradually working on controlling her emotions in other ways:

It wasn’t something that I stopped immediately because, like I said, I tried to work on my emotions. I tried to control my anger. I went back to it and almost went back to it a lot of times. I tried to distract myself from the cause of the pain. . . . It wasn’t a fast process. It was a gradual process.

Participants experiencing a protracted cessation process did not typically memorialize it or assign specific meaning to the final experience.

Processes Supporting Participants Switching Profiles

UC to OC NSSI: Aging and Feedback

Participants reported that getting older and receiving negative feedback influenced their transition from UC NSSI to OC NSSI. Jane shared her feeling that “when you’re in your teens, a lot of people are doing weird self-harm shit. . . . by the time you’re in your 20s, if people see something on your arm, they’re like, ‘what the fuck is wrong with you?’” Shane echoed this: “It was easier to hide when I got older because I understood—cognitively, I was like, ‘well, this isn’t really healthy or appropriate.’ But I still did it.” As participants encountered criticism or judgment related to self-injury, they often became more secretive, restrained, or ritualistic in their behaviors. Roxanne shared how feedback influenced the way she engaged with self-injury:

I had a friend notice, and she told the teacher and I was really embarrassed. And then my grandmother found out and she was really mad. And so I realized that I needed to do a better job hiding it. And so that’s why I moved locations, because I really didn’t want anybody to know. I was embarrassed by it. But it did make me feel a lot better. And so I wanted to keep doing it.

When participants transitioned from a UC NSSI profile to an OC NSSI profile, they typically continued to self-injure in this manner until cessation.

OC to UC NSSI: Intense Interpersonal Distress, Fear, and Shame

Participants described experiences of intense interpersonal distress as a salient factor in their transition from OC NSSI to UC NSSI. During relational conflict that resulted in extreme dysregulation, participants reported losing the ability to moderate their emotions or how severely or impulsively they self-injured. Rex shared an experience of UC NSSI that occurred in the context of an abusive relationship, describing it as a departure from her previous self-injury, which was private, superficial, and very controlled:

and she kept on yelling and yelling and then I did it in front of her and the fat started bleeding out of my arm. . . . It was like scarier and felt way more out of control than anything like I had ever experienced as far as self-harm.

Participants’ impulsivity and emotionality in these moments meant that they might self-injure in the presence of others or reach for tools they didn’t normally use, resulting in wounds that were more severe than they normally experienced.

When participants who typically self-injured in a restrained, private manner experienced UC NSSI, the result was acute feelings of fear and shame. Perhaps because they had previously held judgment of self-injury that occurred impulsively and publicly, self-judgment often occurred in the wake of a transition to UC NSSI. Olive described the fear they felt after the last time they self-injured, which resulted in 17 stitches:

I was having nightmares and flashbacks for three months afterwards. So it was traumatic for me to experience, and I scared myself. I didn’t know that I could do that to myself. I didn’t know that I was capable of causing that kind of harm, and I guess it made me realize how dangerous it was for me to be doing what I was doing because when I actually did it I had a total loss of control in that moment.

These feelings of fear and shame felt by participants, coupled with the loss of equilibrium related to their NSSI identity, prompted them to reconsider the role of NSSI in their lives. Often, this episode of UC NSSI represented the last time they self-injured.

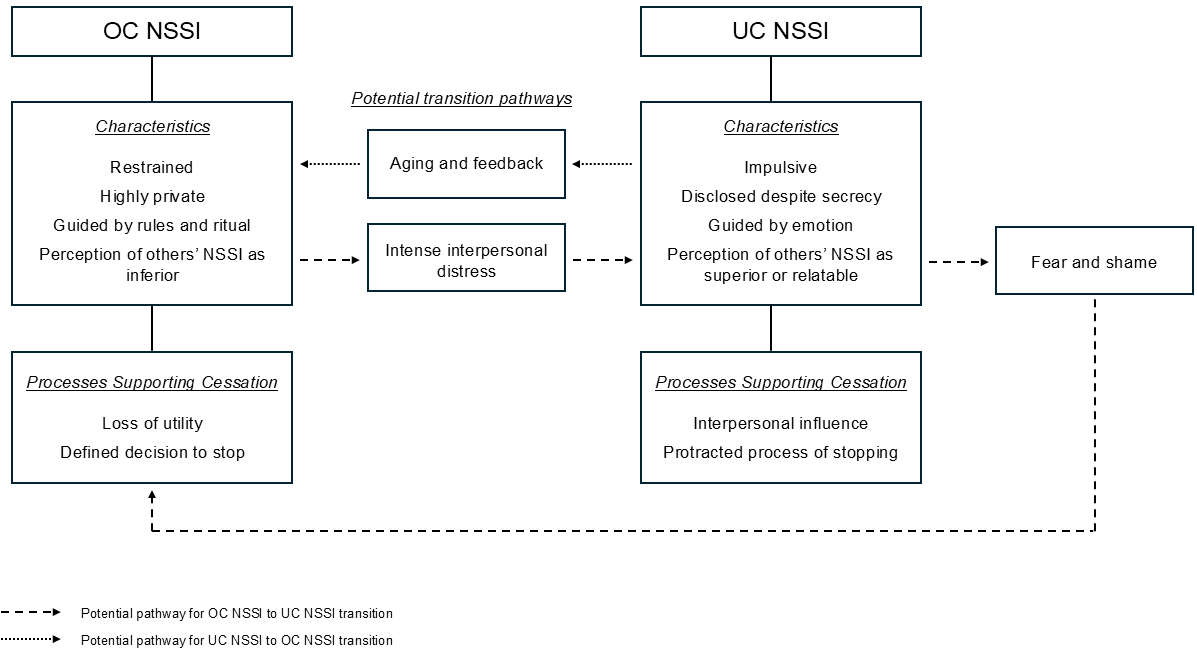

The Theory of Overcontrolled and Undercontrolled Self-Injury, illustrated in Figure 1, was developed based on participant narratives and feedback to represent the experiences, attitudes, and behaviors associated with OC and UC NSSI. Participants were asked to self-identify as UC or OC; however, this classification did not consistently align with their profile of self-injury. For example, three participants identified that their NSSI behavior was markedly different than their behavior in the rest of their lives. Additionally, several participants described transitioning from one profile to another at some point during their self-injury. As a result of this unexpected finding, we categorized participant NSSI based on their descriptions of their self-injurious experiences, attitudes, and behaviors rather than their self-identified personality typology.

Figure 1

Theory of Overcontrolled and Undercontrolled Self-Injury

Discussion

This study provides insight into how self-control influences individuals’ experiences of NSSI. The data identified two distinct profiles, which is consistent with prior research indicating the ability to differentiate NSSI behavior based on its occurrence in OC or UC contexts (Hempel et al., 2018). OC NSSI was characterized as restrained, private, and rule-guided, aligning with previous conceptualizations of OC linked to impulse inhibition, high distress tolerance, and rigid behavioral patterns (Block, 2022; Block & Block, 1980; Lynch et al., 2015). Similarly, UC NSSI was described as impulsive, disclosed despite secrecy, and emotion-driven, consistent with literature highlighting heightened emotional fluctuations, low distress tolerance (Block, 2002), and higher levels of openness and expressiveness (Gilmartin, 2024).

Although a desire for secrecy was reported in both OC and UC NSSI, the commitment and dedication to maintaining this privacy varied between groups. This study’s findings differ slightly from those of Hempel et al. (2018), who described UC NSSI as public, lacking nuance regarding participants’ internal conflicts. Participants’ dissonance regarding disclosure may be viewed through a lens of dialectics. Linehan (1993) described BPD, a disorder of UC, as a “dialectical failure” in which individuals vacillate between contradictory viewpoints, rendering their behavior inconsistent and confusing. OC, on the other hand, has been associated with maladaptive perfectionism (Lynch et al., 2015), in which individuals avoid vulnerability to maintain an image of flawless performance (Dunkley et al., 2003). Those striving to appear problem-free may perceive their self-injury as a sign that they are flawed or weak and thus go to great lengths to conceal it. Because both groups describe their NSSI as secretive, further exploration of disclosure patterns is essential to facilitate deeper understanding.

An unexpected finding was that participants’ perceptions of others’ NSSI differed based on whether they engaged in UC or OC NSSI. One explanation for the association between OC NSSI and a perception of others as inferior may lie in a phenomenon described by Lynch (2018) as “the enigma predicament.” The enigma predicament is a self-protective stance in which OC individuals believe they are fundamentally different or more complex than others. This attitude maintains social isolation, aloofness, and a feeling of being misunderstood. Cultural emphasis on self-control may bolster beliefs of superiority among these individuals, fostering a secret sense of pride.

No existing literature was found that explored the judgments of individuals who self-injure related to others’ NSSI; however, viewing these findings through the lens of social norms offers context. OC individuals are sensitive to social pressures and conformity, whereas UC individuals are less concerned with societal norms (Block, 2002). Individuals experiencing UC NSSI may be more likely to disregard prescriptive norms for self-presentation, facilitating empathy or admiration for those openly displaying their NSSI. Those experiencing OC NSSI, which is typically a well-kept secret, may be unlikely to encounter others engaging in NSSI in a like manner.

Another novel finding lies in the shifts participants described in their self-injury profile as a direct result of specific experiences, such as aging and feedback. Although no existing literature was found that examined this phenomenon, UC typically peaks in early to middle adolescence (Hasking & Claes, 2020), suggesting that aging may influence a transition from impulsive to more restrained NSSI for some individuals. It is also plausible that individuals whose self-injury was disclosed (i.e., UC NSSI) would receive more negative feedback than those whose self-injury remained concealed (i.e., OC NSSI). Participants who reported switching from OC to UC NSSI attributed this change to experiences of intense interpersonal distress that appeared to eclipse their high capacity for restraint and control. Lynch (2018) described this phenomenon as “emotional leakage,” in which OC individuals temporarily lose the ability to inhibit their impulses, leading to intense emotional outbursts followed by feelings of shame and self-criticism.

Implications for Counselors

The emergent theory in this study creates a new theoretical model that may provide valuable implications for clinical practice. The identification of two distinct profiles of NSSI supports previous research indicating that individuals with both low and high levels of self-control may engage in self-injurious behavior (Hempel et al., 2018). The current proposed criteria for NSSI disorder, listed in Section III of the DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022) as a condition for further study, would identify both OC and UC NSSI as conceptualized in this study. For instance, criterion C specifies that self-injury may involve “a period of preoccupation with the intended behavior that is difficult to control” or “frequent thoughts about self-injury, even if not acted upon” (p. 923). This expands previous views of NSSI by recognizing behaviors that involve greater restraint alongside those driven by impulse inhibition failures.

Knowing this, counselors may benefit from conducting thorough assessments to accurately diagnose and differentiate between OC and UC NSSI. This can involve using clinical interviews, standardized assessments, and behavioral observations to evaluate clients’ impulse control and emotional regulation abilities. Recommended measures include the Assessing Styles of Coping: Word-Pair Checklist (Lynch, 2018) for adults and the Youth Over- and Under-Control Screening Measure (Lenz et al., 2021) for children and adolescents. To assess OC and UC self-injury specifically, including questions in clinical interviews that evaluate the dimensions explored in this study may be helpful. Clinicians can also inquire specifically about clients’ NSSI impulsivity and emotionality levels, disclosure and aftercare behaviors, and whether any rules or rituals inform the behavior. Questions such as, “When you self-injure, do you tell anyone about it before or afterward?” and “Do you have any rules about when, where, or how you self-injure?” may assist clinicians in developing a deeper understanding of the processes driving the behavior, thereby informing the use of congruent therapeutic interventions.

Participants in this study highlighted distinct processes influencing their NSSI behaviors and cessation, emphasizing the need for tailored treatment approaches based on whether NSSI occurs in an OC or UC context. Traditional therapeutic approaches to treating self-injury, such as DBT (Linehan, 1993) and emotional regulation group therapy (Andover & Morris, 2014), which focus on improving emotional regulation and distress tolerance, may need to be adapted or supplemented to address specific vulnerabilities and underlying mechanisms related to OC NSSI. Interventions targeting UC NSSI should emphasize enhancing inhibitory control and distress tolerance while reducing emotional reactivity. Conversely, interventions treating OC NSSI should aim to relax excessive inhibitory control and rigidity while increasing emotional expressiveness and openness. RO DBT, which was developed specifically to treat disorders of OC by targeting deficits related to excessive inhibitory control (Lynch et al., 2015), represents a promising approach for these clients.

Understanding participants’ perceptions of others’ NSSI behaviors also holds implications for social contagion (Conigliaro & Ward-Ciesielski, 2023). Previous research has implicated identifying or relating with others who self-injure (Whitlock et al., 2009) and a higher need to belong (Conigliaro & Ward-Ciesielski, 2023) as factors increasing vulnerability to social contagion. Because UC NSSI was associated with a perception of others’ NSSI as superior or relatable, individuals exhibiting this self-injury profile may be more vulnerable to the effects of social contagion. Counselors should be aware of these dynamics when formulating interventions.

Lastly, counselors can benefit from considering how the enigma predicament may negatively impact the therapeutic relationship with OC clients who may believe that they are so complex or unique that they will invariably be misunderstood (Lynch, 2018). This may explain why study participants experiencing OC NSSI sometimes found therapy unrewarding or unhelpful, particularly if counselors generalized about self-injury in a way that felt incongruous with their experiences. Knowing this, counselors should aim to set aside their assumptions about self-injury and allow the client to educate them on their experience.

Care should also be taken when asserting that OC NSSI behavior is normal, common, or understandable. Although this might typically be viewed as a positive intervention (i.e., normalizing the behavior), such expressions may cause alliance ruptures in this population (Lynch, 2018). Acknowledging these unique perspectives and avoiding assumptions about the normalcy or commonality of NSSI behaviors can help maintain therapeutic rapport and prevent alliance ruptures. By integrating these implications into clinical practice, counselors can enhance their ability to effectively assess, conceptualize, and intervene with UC and OC NSSI, ultimately promoting resilience and improved psychological well-being.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Several limitations must be acknowledged in order to interpret this study’s findings. First, because of the absence of validated measures of UC and OC, participants self-identified based on Block and Block’s (1980) conceptualization of these terms. Knowing the challenges associated with the clinical assessment of OC (Hempel et al., 2018) and the subjective nature of self-assessment, it is reasonable to assume that some participants may have self-identified in ways that are incongruent with established criteria for UC and OC. Future studies aimed at the development of instruments capable of effectively measuring and differentiating between OC and UC NSSI would aid mental health and medical professionals in congruent conceptualization and intervention for NSSI. They would also pave the way for quantitative exploration of UC and OC NSSI, potentially fostering greater knowledge, understanding, and generalizability.

The sample in this study was composed predominantly of White women, limiting its ability to encompass a diversity of experiences. It is possible that a more diverse sample would have generated different results. Future studies should intentionally strive to incorporate more diverse samples, specifically focusing on amplifying the voices and experiences of gender-diverse individuals, people of color, and men. Care should be taken in generalizing the results of this analysis, especially in groups underrepresented in sampling. Additionally, participants in this study had not self-injured in the last 3 years, which may have allowed for a greater degree of cognitive processing related to their experiences. Future studies focusing on current self-injurious experiences are needed to support the development of effective interventions in this population.

Finally, this study’s qualitative design has inherent limitations despite efforts to ensure credibility and trustworthiness. The semi-structured interview method used may influence participant responses through question framing, wording, and presentation. Additionally, the research team’s perspective inevitably influences the interpretation of findings, allowing for alternative interpretations by different research teams.

Conclusion

The constructivist grounded theory findings enrich our initial grasp of how self-control influences NSSI experiences, attitudes, and behaviors, offering significant implications for mental health research and clinical practice. Future efforts should focus on translating these insights into evidence-based assessments and interventions that acknowledge individuals’ attitudes, motivations, and vulnerabilities associated with NSSI, aiming to effectively enhance resilience and well-being.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.).

Andover, M. S. (2014). Non-suicidal self-injury disorder in a community sample of adults. Psychiatry Research, 219(2), 305–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.06.001

Andover, M. S., & Morris, B. W. (2014). Expanding and clarifying the role of emotion regulation in nonsuicidal self-injury. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(11), 569–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405901102

Baumeister, R. F., & Heatherton, T. F. (1996). Self-regulation failure: An overview. Psychological Inquiry, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0701_1

Block, J. (2002). Personality as an affect-processing system: Toward an integrative theory. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Block, J. H., & Block, J. (1980). The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior. In W. A. Collins (Ed.), Development of cognition, affect, and social relations: The Minnesota symposia on child psychology (Vol. 13, pp. 39–101). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Brager-Larsen, A., Zeiner, P., Klungsøyr, O., & Mehlum, L. (2022). Is age of self-harm onset associated with increased frequency of non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in adolescent outpatients? BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03712-w

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Claes, L., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Vandereycken, W. (2012). The scars of the inner critic: Perfectionism and nonsuicidal self-injury in eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 20(3), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1158

Conigliaro, A., & Ward-Ciesielski, E. (2023). Associations between social contagion, group conformity characteristics, and non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of American College Health, 71(5), 1427–1435. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1928141

da Cunha Lewin, C., Leamy, M., & Palmer, L. (2024). How do people conceptualize self-harm recovery and what helps in adolescence, young and middle adulthood? A qualitative meta-synthesis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 80(1), 39–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23588

Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S., Giardina, M. D., & Cannella, G. S. (2023). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (6th ed.). SAGE.

Doyle, L., Sheridan, A., & Treacy, M. P. (2017). Motivations for adolescent self-harm and the implications for mental health nurses. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(2–3), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12360

Dunkley, D. M., Zuroff, D. C., & Blankstein, K. R. (2003). Self-critical perfectionism and daily affect: Dispositional and situational influences on stress and coping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.234

Edmondson, A. J., Brennan, C. A., & House, A. O. (2016). Non-suicidal reasons for self-harm: A systematic review of self-reported accounts. Journal of Affective Disorders, 191(1), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.043

Favazza, A. R. (2011). Bodies under siege: Self-mutilation, nonsuicidal self-injury, and body modification in culture and psychiatry (3rd ed.). John Hopkins University Press.

Gilmartin, T., Dipnall, J. F., Gurvich, C., & Sharp, G. (2024). Identifying overcontrol and undercontrol personality types among young people using the five factor model, and the relationship with disordered eating behaviour, anxiety and depression. Journal of Eating Disorders, 12, Article 16.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-024-00967-4

Giordano, A., Lundeen, L. A., Scoffone, C. M., Kilpatrick, E. P., & Gorritz, F. B. (2020). Clinical work with clients who self-injure: A descriptive study. The Professional Counselor, 10(2), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.15241/ag.10.2.181

Giordano, A. L., Prosek, E. A., Schmit, E. L., & Schmit, M. K. (2023). Examining coping and nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents: A profile analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development, 101(2), 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12459

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

Glenn, C. R., & Klonsky, E. D. (2010). A multimethod analysis of impulsivity in nonsuicidal self-injury. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 1(1), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017427

Hambleton, A. L., Hanstock, T. L., Halpin, S., & Dempsey, C. (2022). Initiation, meaning and cessation of self-harm: Australian adults’ retrospective reflections and advice to adolescents who currently self-harm. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 35(2), 260–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1737509

Hamza, C. A., Willoughby, T., & Heffer, T. (2015). Impulsivity and nonsuicidal self-injury: A review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 38(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.010

Hasking, P., & Claes, L. (2020). Transdiagnostic mechanisms involved in nonsuicidal self-injury, risky drinking, and disordered eating: Impulsivity, emotion regulation, and alexithymia. Journal of American College Health, 68(6), 603–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2019.1583661

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2023). Qualitative research in education and social sciences (2nd ed). Cognella.

Hempel, R. J., Rushbrook, S., O’Mahen, H. A., & Lynch, T. R. (2018). How to differentiate overcontrol from undercontrol: Findings from the RefraMED study and guidelines from clinical practice. The Behavior Therapist, 41(3), 132–142.

Hofmann, W., Luhmann, M., Fisher, R. R., Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2014). Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well-being and life satisfaction. Journal of Personality, 82(4), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12050

Klonsky, E. D., Victor, S. E., & Saffer, B. Y. (2014). Nonsuicial self-injury: What we know, and what we need to know. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(11), 565–568. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F070674371405901101

Kruzan, K. P., & Whitlock, J. (2019). Processes of change and nonsuicidal self-injury: A qualitative interview study with individuals at various stages of change. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 6, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393619852935

Kruzan, K. P., Whitlock, J., & Hasking, P. (2020). Development and initial validation of scales to assess decisional balance (NSSI-DB), processes of change (NSSI-POC), and self-efficacy (NSSI-SE) in a population of young adults engaging in nonsuicidal self-injury. Psychological Assessment, 32(7), 635–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000821

Lenz, A. S., James, P., Stewart, C., Simic, M., Hempel, R., & Carr, S. (2021). A preliminary validation of the Youth Over- and Under-Control (YOU-C) screening measure with a community sample. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 43(4), 489–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-021-09439-9

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford.

Liu, R. T., Trout, Z. M., Hernandez, E. M., Cheek, S. M., & Gerlus, N. (2017). A behavioral and cognitive neuroscience perspective on impulsivity, suicide, and non-suicidal self-injury: Meta-analysis and recommendations for future research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 83, 440–450.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.09.019

Lynch, T. R. (2018). Radically open dialectical behavior therapy: Theory and practice for treating disorders of overcontrol. Context Press.

Lynch, T. R., Hempel, R. J., & Dunkley, C. (2015). Radically open-dialectical behavioral therapy for over-control: Signaling matters. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 69(2), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.2.41

Metcalfe, J., & Mischel, W. (1999). A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychological Review, 106(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.1.3

Muehlenkamp, J. J., Swenson, L. P., Batejan, K. L., & Jarvi, S. M. (2015). Emotional and behavioral effects of participating in an online study of nonsuicidal self-injury: An experimental analysis. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614531579

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x

Timonen, V., Foley, G., & Conlon, C. (2018). Challenges when using grounded theory: A pragmatic introduction to doing GT research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918758086

Whisenhunt, J. L., Chang, C. Y., Flowers, L. R., Brack, G. L., O’Hara, C., & Raines, T. C. (2014). Working with clients who self-injure: A grounded theory approach. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(4), 387–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00165.x

Whitlock, J., Pietrusza, C., & Purington, A. (2013). Young adult respondent experiences of disclosing self-injury, suicide-related behavior, and psychological distress in a web-based survey. Archives of Suicide Research, 17(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.748405

Whitlock, J., Purington, A., & Gershkovich, M. (2009). Media, the internet, and nonsuicidal self-injury. In M. K. Nock (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp. 139–155). American Psychological Association.

Appendix

Interview Protocol

- Please give me a brief timeline of your experiences with self-injury over the course of your lifetime.

Alternate wording:

I’d like to ask you to think back to the first time you self-injured. Could I ask you to describe what led to that moment? - Where on your body did you typically self-injure?

- Have you ever hurt yourself during self-injury to the extent that you needed medical assistance, even if you did not receive it?

Follow-up questions:

a. What was the experience of seeking medical help like for you?

b. How did you manage treating the injury without medical professionals? - What has your experience been with disclosing your self-injury to others?

Follow-up questions:

a. Who are the people in your life that are aware that you have self-injured?

b. Did you choose to tell those people about your self-injury or did they find out in some other way?

c. What were people’s responses when they found out that you had self-injured?

d. What influenced your decision to disclose or not disclose your self-injury? - Please describe the purpose of your self-injury?

Alternate wording:

How did your self-injury influence your mental health? Relationships?

What did self-injury offer you? - When you self-injured, to what extent did you plan how, when, or where you were going to do it in advance?

Follow-up questions:

a. How would you describe the period of time between thinking about how or when you were going to self-injure and the self-injurious behavior itself?

b. How long was the period of time, generally, between the thought and the behavior?

- Did you have any rules about when, where, or how you self-injured? If so, could I ask you to describe them to me?

- If you think about your level of distress or emotionality as a wave with a peak where the emotion is most intense, when did your self-injury typically occur along that continuum?

- If a close friend or family member had seen you in the moments before you self-injured, to what extent would they have suspected that you were in distress?

Follow-up question:

What factors would have influenced their idea that you were/were not in distress? - How would you describe the experiences that led you to stop self-injuring?

Is there anything else you would like to add about your experiences that we haven’t touched on?

Sara E. Ellison, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC, is adjunct faculty at Auburn University and the University of West Georgia. Jill M. Meyer, PhD, LPCP, CRC, is a professor and Director of Counselor Education at Auburn University. Julia Whisenhunt, PhD, NCC, LPC, CPCS, is a professor, assistant chair, and program director at the University of West Georgia. Jessica Meléndez Tyler, PhD, NCC, BC-TMH, LPC-S, is an associate professor at Vanderbilt University. Correspondence may be addressed to Sara E. Ellison, 3084 Haley Center, Auburn, AL 36849, szm0194@auburn.edu.