Oct 31, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 3

Alexander M. Fields, Cara M. Thompson, Kara M. Schneider, Lucas M. Perez, Kaitlyn Reaves, Kathryn Linich, Dodie Limberg

The integration of behavioral health care within primary care settings, otherwise known as integrated care, has emerged as a treatment modality for counselors to reach a wide range of clients. However, previous counseling scholars have noted the lack of integrated care representation in counseling journals. In this scoping review, we identified 27 articles within counseling journals that provide integrated care implications. These articles appeared in 10 unique counseling journals, and the publication years ranged from 2004–2023. Articles were classified as: (a) conceptual, (b) empirical, or (c) meta-analyses and systematic reviews. The data extracted from the articles focused on the implications for integrated care training and practice for the next generation of counselors, evidence-based treatment approaches, and future research directions.

Keywords: integrated care, counseling journals, scoping review, implications, research

One in five U.S. adults are living with a mental illness or substance use disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol use disorder, nicotine use disorder) and individuals with a mental illness or substance use disorder are more likely to have a chronic health condition (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2021). Integrated primary and behavioral health, also termed integrated care (IC), has emerged as a noted treatment strategy to meet the holistic needs of individuals with comorbid mental and physical health symptoms. Although IC has been operationalized inconsistently by scholars, most definitions describe the integration and coordination of behavioral health services within primary care settings (Giese & Waugh, 2017). The SAMHSA-HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration) Center for Integrated Health Solutions expanded upon this definition to outline IC on a continuum of health care service delivery (Heath et al., 2013). Heath and colleagues described the progressive movement toward IC as (a) collaborative care: providers from multiple health care professions collaborating on holistic health care treatment planning at a distance;

(b) co-located care: providers from multiple health care professions sharing basic system integration, such as sharing physical proximity and more frequent collaboration; and (c) IC: providers from multiple health care professions having systematic integration (i.e., sharing electronic medical records and office space) and a high level of collaboration resulting in a unified treatment approach. Thus, health care consumers are able to receive care for their behavioral and physical health at the same time and location when an IC approach is applied, which may reduce barriers (e.g., transportation, child care, time off work) and increase access to behavioral health care (Vogel et al., 2014).

Beyond support from SAMHSA and HRSA, the IC movement has been endorsed through government legislation. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010) paved the way for agencies and health care systems demonstrating an IC approach to receive additional funding for health care providers, as well as increased reimbursements for the services they deliver. Furthermore, the federal government has recently pledged to double the funding support for IC to be more accessible in hospitals, substance abuse treatment facilities, family care practices, school systems, and other health care settings (The White House, 2022). This may be the result of IC showing efficacy in reducing mental health symptoms (Lenz et al., 2018), saving health care expenditures (Basu et al., 2017), and promoting overall life satisfaction (Gerrity, 2016). Compared to traditional (i.e., siloed) care, IC involves simultaneous treatment from physical and mental health providers, thus providing additional access to mental health screenings and services. For example, McCall et al. (2022) concluded that a mental health counselor in an IC setting may support treatment engagement and reduce health care costs for an individual with a substance use disorder when utilizing the screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) model. However, the IC paradigm is not a novel concept; Aitken and Curtis (2004) introduced IC to counseling journals by providing emerging evidence of IC support and advocating for health care settings to recognize counselors as an asset to IC teams and for counselors to be trained in IC.

Brubaker and La Guardia (2020) noted that the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (Section 5, Standard C.3.d; CACREP; 2015) required IC education in counselor-in-training (CIT) development. Additionally, the 2024 CACREP Task Force has also included these standards for its proposed revisions (CACREP, 2022). HRSA has funded counselor education programs to train CITs during practicum and internship experiences, funding over 4,000 new school, addiction, or mental health counselors during 2014–2022 through the Behavioral Health Workforce and Education Training (BHWET) Program (HRSA, 2022). Although IC training, education, and practice is occurring within counselor education, IC literature remains scarce in counseling journals (Fields et al., 2023). The lack of representation presents an issue for appropriate training for CITs and future research directions, which leads to sustainability concerns. Specifically, Fields et al. (2023) reported that a lack of IC literature in counseling journals creates a weak foundation to advocate for counselors to be included in the IC movement. With the understanding that nearly half of U.S. adults with poor mental health receive their mental health care in a primary care setting (Petterson et al., 2014), counselors may increase their access to additional clients when they are invited to IC settings. Furthermore, it weakens counselors’ professional identity if counselors are not trained in a standardized approach. As such, this scoping review aims to amalgamate current IC literature within counseling journals and provide CITs, counselors, and counselor educators from diverse backgrounds with a resource to inform their education, practice, and scholarship. The guiding research question for this review is: What are the publication trends (i.e., publication years and journals), study characteristics and outcomes, implications, and recommendations for future research from IC literature within counseling journals?

Method

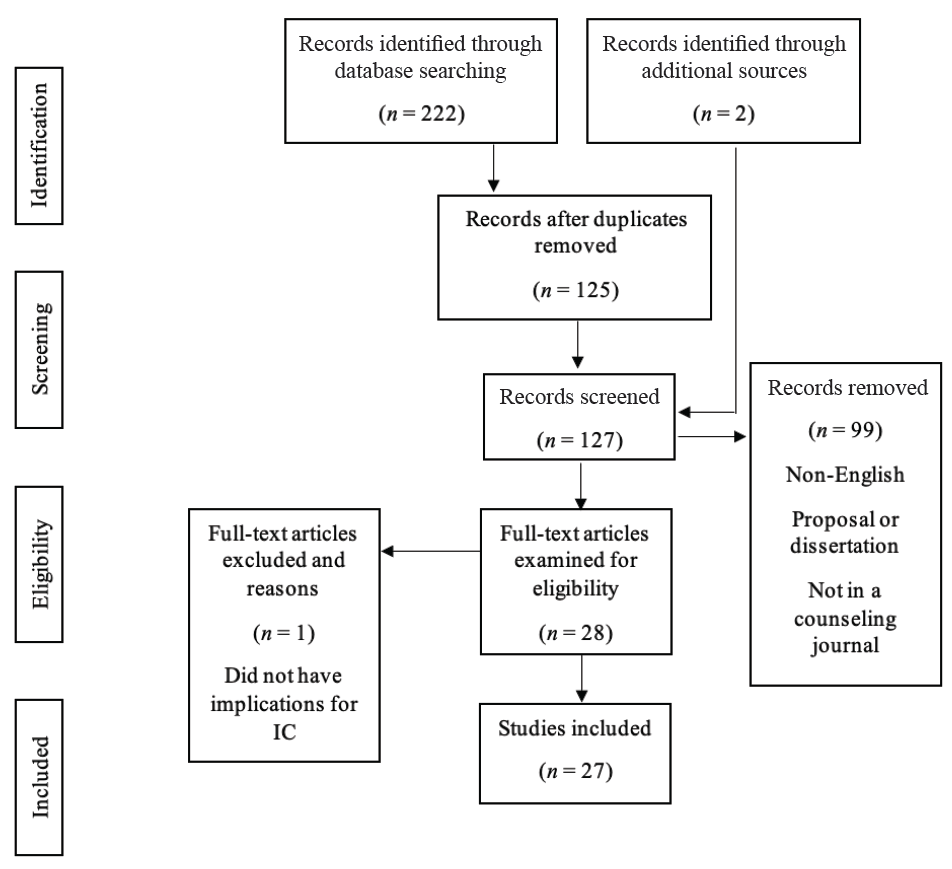

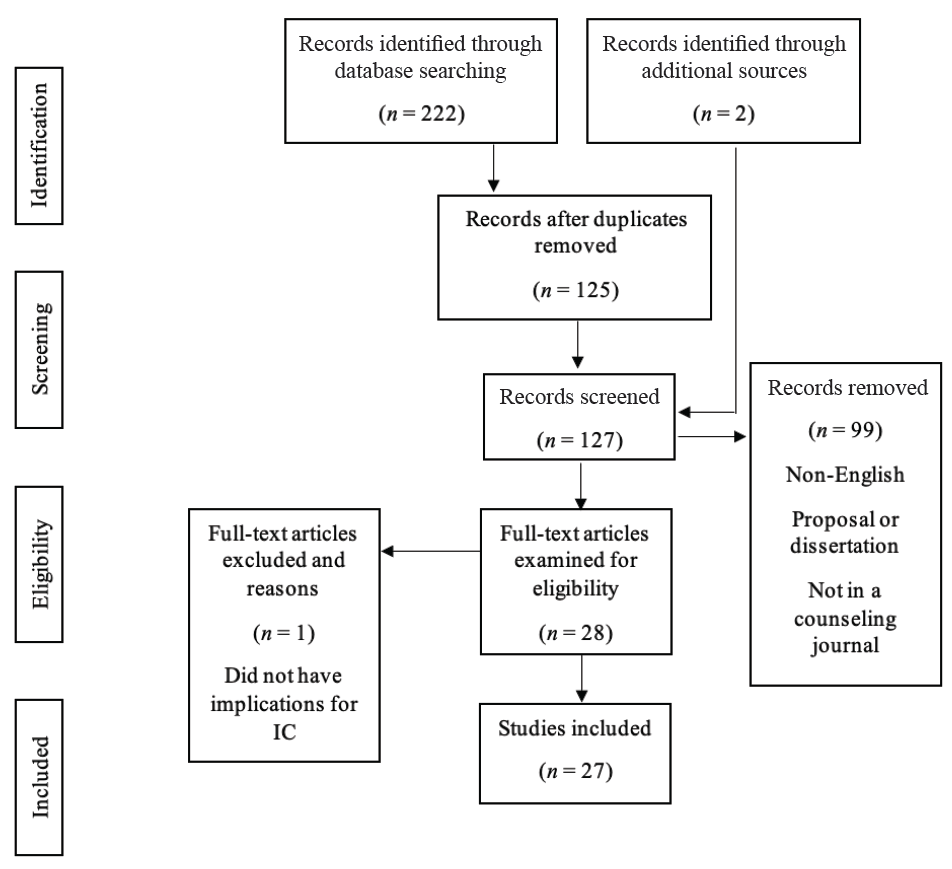

We conducted a scoping review to identify the publication trends, key characteristics of IC studies (i.e., type of article and study outcomes), and implications for future research of IC literature published in counseling journals (Munn et al., 2018). Our methodology followed the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews; Tricco et al., 2018) checklist to 1) establish eligibility, 2) identify sources of information, 3) conduct a screening process to select included articles, 4) identify and chart data items, 5) conduct a critical appraisal of included articles, and 6) synthesize results. We searched the following databases for eligible literature: (a) Alt HealthWatch, (b) APA PsycArticles, (c) APA PsycInfo, (d) Education Source, (e) EBSCOHost, (f) Health Source: Consumer Edition, (g) Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, (h) MEDLINE with Full Text, (i) Science Reference Center, (j) Social Sciences Full Text (H.W. Wilson), and (k) Social Work Abstracts. We used the search terms: “Integrat* care” OR “integrat* primary and behavioral healthcare” OR “integrat* primary and behavioral care” AND “counsel* education” OR “counsel*.” Additional criteria for this search were full-text, peer-reviewed journal articles, and an English translation.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria for articles included in this review are publication in a counseling journal, presentation of implications (i.e., recommendations for training and evidence-based counseling models or approaches) of IC practice for CITs and counselors through research methodology or conceptual themes, and discussion of future research on IC for counselor educators and counseling scholars through research methodology or conceptual themes. Eligible counseling journals included those published by divisions of the American Counseling Association (ACA), the American Mental Health Counselors Association (AMHCA), the American School Counselor Association (ASCA), the National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC), and Chi Sigma Iota. Journals connected to international and regional divisions were also included. The initial database search resulted in 222 articles, which we reduced to 125 articles after removing duplicates. Another two articles were identified through additional sources. These additional sources included references identified through a review of an article and a social media post advertising an IC article. We reviewed titles and abstracts for inclusion criteria. This resulted in 28 articles that were fully reviewed. Research team members independently examined articles to summarize information relevant to the research question. During this process, articles were excluded if they did not provide future implications for IC in counseling or counselor education. Following this process, 27 articles were included. A visual representation of the eligibility and inclusion process can be found in Figure 1.

Data Extraction

After consensus was reached on the final 27 articles, our research team assessed the available evidence and synthesized the results. The seven-member research team comprised four doctoral students in counselor education, an undergraduate student minoring in counselor education, a clinical assistant professor in a counselor education program, and an associate professor in a counselor education program. The initial data extraction process began with identifying journal representation and organizing articles based on similar characteristics. This resulted in classifying articles as either (a) conceptual, (b) empirical, or (c) meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Conceptual articles provided an overview of available literature and identified a current gap in IC understanding for counseling or counselor education. Articles classified as conceptual did not present original data or follow research methodology. Moreover, the conceptual models typically advocated for increased counseling representation in IC settings to reach traditionally underserved groups (e.g., LGBTQ+ clients, individuals from rural communities) or a replicable model of training grounded in empirical support to prepare CITs to work in IC settings. Data from these articles were presented in accordance with the authors’ population(s) of interest, the identified research gap, implications gathered from existing literature, and recommendations for future research. Empirical articles introduced a novel research question and presented results to address that question. Data from these articles were presented in accordance with the authors’ study classification (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), research methodology, the number and profile of participants, research of interest, and results from their analyses. Lastly, meta-analyses and systematic reviews organized previous empirical studies and presented big picture results across multiple studies. Data from these articles were presented in accordance with the authors’ article classification (i.e., meta-analysis or systematic review), population of interest, number of included studies and number of total participants (if applicable), results, and implications for future research. Because of the broad scope and exploratory nature of this review, a quality assessment was not performed.

Figure 1

Integrated Care Literature in Counseling and Counselor Education Flow Chart

Note. This flow chart outlines the PRISMA-ScR (Tricco et al., 2018) search process.

Results

This scoping review resulted in a wide variety of articles in counseling journals that may inform the future of IC research in counseling and counselor education. Additionally, articles included in our review have ranging implications at the CIT, counselor, and client levels. The results section will begin with an overview of IC publication trends within counseling journals, detailing the publication range and specific journals. Next, results for this review were organized based on study outcomes and the classification of the article. The study outcomes sections will further detail included articles that are conceptual, empirical, or meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

Publication Trends

Articles included in this review range in publication year from 2004–2023. Articles are represented in 10 unique journals. Specifically, the following journals are represented in this review: (a) Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation (n = 2); (b) International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling (n = 2); (c) Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling (n = 2); (d) Journal of College Counseling (n = 1); (e) Journal of Counseling & Development (n = 7); (f) Journal of Creativity in Mental Health (n = 1); (g) Journal of LGBTQ Issues in Counseling (n = 1); (h) Journal of Mental Health Counseling (n = 9); (i) The Family Journal (n = 1); and (j) The Professional Counselor (n = 1).

Study Outcomes

Conceptual Articles

Our review included 11 conceptual articles (see Appendix A). Of these studies, five described IC as a treatment approach for underserved populations. In each of these articles, the authors described how IC provided a “one-stop-shop” treatment approach that provided increased access to a mental health provider in a traditional primary care setting, which reduced barriers to transportation, cost per service, and provider shortages. Six studies focused on current licensed counselors in primary care settings, counselor educators, CITs in a CACREP-accredited program, and counselors interested in IC. Common implications of these articles included advocacy, education, communication, networking, and teamwork.

Eight studies described how additional research could empirically investigate their IC model. The authors of these conceptual articles recommended continued investigation of the current medical model and national recognition of gaps of care for both the chronic pain and substance abuse population; integrating the interprofessional education collaborative (IPEC) into the curriculum of mental health counselors; interprofessional telehealth collaboration (IPTC) through cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for rural communities; treatments aligned with cultural tailoring; implementation of IC for those in the LGBTQ+ community; trauma-informed IC; and the role of counselors in an IC team treating obesity. The conceptual models reported in Table 1 highlight evidence-based approaches a counselor can apply in IC settings to assess for substance abuse and mental health disorders, brief interventions (e.g., CBT technique of challenging automatic thoughts, motivational interviewing) to encourage engagement in preventative health care, and trauma-informed practices (e.g., psychoeducation on trauma somatization). Moreover, counselors trained in the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC; Ratts et al., 2016) can advocate for culturally tailored interventions to respect a client’s cultural identity.

Two studies highlighted different approaches to IC. Johnson and Mahan (2020) identified the IPTC model, which allows health professionals to use technology to increase access to services for rural communities. The IPTC model provides telehealth services to rural communities through an IC model to reduce negative social determinants of health, such as distance from a mental health provider. Specifically, Johnson and Mahan (2020) detailed their approach to working alongside primary care providers to deliver family counseling services and coordinate health care services to promote overall health and wellness for family systems. Goals of their family counseling sessions included increasing health literacy, enhancing a family’s coping strategies for medical conditions, and reducing family conflicts. The Chronic Care Model has been shown to improve the quality of care for clients with chronic medical conditions by increasing communication between health care professionals (Sheesley, 2016). Two articles also focused on the impact of two identified training programs. Johnson and Freeman (2014) identified the IPEC Expert Panel and their efforts to effectively train health professionals to collaborate. Lloyd-Hazlett et al. (2020) focused on the Program for the Integrated Training of Counselors in Behavioral Health (PITCH), which is a training program for master’s-level counseling students in a CACREP-accredited program aimed at training students to supply IC to rural, vulnerable, and underserved communities. These results are represented in Appendix A.

Empirical Articles

Our review resulted in 13 empirical studies using the following designs: three mixed-methods designs, three quasi-experimental designs, two cross-sectional surveys, two pre-post designs, three phenomenological studies, and one exploratory cross-case synthesis. The studies were completed in a variety of settings, such as university clinics, trauma centers, and hospitals. Participant profiles varied across studies, with nine representing CITs or practicing counselors, three representing clients, and one representing both. In addition to counselors, studies with client-level data included service providers and undergraduate students from social work, speech–language pathology, dental hygiene, nursing, and physical therapy programs. Articles that reported client-level data tested an intervention (e.g., motivational interviewing in an IC setting for a substance use disorder), compared an IC approach to treatment as usual (TAU) in silos, or explored relationships between health care indicators and client engagement in a setting applying an IC modality. Furthermore, three studies in this article used Heath et al.’s (2013) conceptualization of IC, which was the most common model cited.

Most study outcomes were reported as positive benefits for IC. For CIT and counselor-level studies, six described a theme of increased ability and desirability to work with a collaborative approach on IC teams. Participants also commonly reported an increase in professional identity and self-efficacy. Participants in studies by Agaskar et al. (2021), Alvarez et al. (2014), and Lenz and Watson (2023) further demonstrated that working with underserved populations in IC settings increased their multicultural competence, specifically around areas of acceptance, advocacy, and awareness. A gap in IC awareness among service providers and organizational constraints were noted as potential barriers to IC care. Johnson et al. (2021) found interprofessional supervision as a potential barrier to remaining within a provider’s scope of practice, because a supervisor providing supervision to a supervisee from a different professional identity may not appropriately understand roles and responsibilities. Because of this, Johnson and colleagues noted implications for future research and graduate-level training in the classroom and field experience. All four of the studies completed with client-level data were quantitative, accounting for 2,378 client participants. Results of these studies suggested improvement in holistic client functioning (i.e., reduction in pathological symptoms and increase in preventative behaviors; Ulupinar et al., 2021), a decrease in crisis events (Schmit et al., 2018), and decrease in risky drinking behaviors for individuals receiving IC trauma care (Veach et al., 2018). The self-stigma of mental illness and of seeking help had an inverse relationship with mental health literacy among patients who received treatment in an IC setting (Crowe et al., 2017). These results are represented in Appendix B.

Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews

Three articles in this review were meta-analyses or systematic reviews. Specifically, two articles were meta-analyses and one was a systematic review. Participants within these studies included adults with substance use disorders, mental health professionals receiving training to practice within IC, and individuals receiving mental health care in traditional primary care settings. All three articles described benefits of IC. Additionally, the authors differed on the number of studies and participants included in their analyses. Fields et al. (2023) completed a review of 18 articles that studied training interventions for mental health professionals to work on IC teams and concluded that training in IC promotes aspects of interprofessional collaboration, professional identity development, and self-efficacy. Balkin et al. (2019) concluded no statistical significance between IC treatment and TAU to decrease frequency of substance use. Balkin et al. also remarked that their study, including 1,545 participants, did not reach statistical power and results should be considered preliminary. Lenz et al. (2018) reported a decrease in mental health symptoms with a greater effect when a larger treatment team and number of behavioral health sessions are increased, compared to TAU. Lenz and colleagues generated their results from 14,764 participants. Lastly, Fields et al. (2023) and Lenz et al. (2018) both used Heath et al.’s (2013) model of IC for conceptualization. For all three of these studies, additional research is needed to understand IC at the client or consumer level, as well as how different variables affect the treatment process. These results are represented in Appendix C.

Discussion

Implications for Counseling Practice

The results of this scoping review have implications that may inform clinical practice for counselors and CITs. Most results suggested clinical benefits for individuals receiving counseling services through an IC setting. Clients or consumers that received IC treatment reported a reduction of mental health symptoms (Lenz et al., 2018; Ulupinar et al., 2021), mental health stigma (Crowe et al., 2018), and crisis events (Schmit et al., 2018). As almost half of individuals with poor mental health receive treatment in primary care settings (Petterson et al., 2014), integrating a counselor into a traditional primary care setting (e.g., hospital, community health care clinic) provides an additional treatment team member with specialized training to treat mental health concerns. Because of the potentially fast nature of IC settings, interested counselors are encouraged to review SAMHSA applications of SBIRT to facilitate brief meetings until more long-term services are provided. Furthermore, counselors may consider reviewing resources on evidence-based approaches, such as Ultra-Brief Cognitive Behavioral Interventions: A New Practice Model for Mental Health and Integrated Care (Sperry and Binensztok, 2019), and understanding common medical terminology, such as A Therapist’s Guide to Understanding Common Medical Conditions (Kolbasovsky, 2008).

Articles that were classified as conceptual also suggested that IC treatment has the potential to enhance service delivery for clients from diverse populations, such as LGBTQ+ and medically underserved communities (Kohn-Wood & Hooper, 2014; Moe et al., 2018). The primary rationale described by scholars is that an IC approach advocates for diverse populations to reduce social determinants of health, such as proximity barriers, communications barriers, and availability of culturally appropriate interventions. Counselors interested in working in an IC setting are strongly encouraged to review the MSJCC (Ratts et al., 2016) and be prepared to serve as an advocate for their client as they navigate the health care system. The Hays (1996) ADDRESSING model also provides counselors a conceptualization model for understanding power and privileges associated with cultural differences. Information drawn from an understanding of power and privileges may further assist the interdisciplinary team with delivering culturally appropriate care. However, Balkin et al. (2019) concluded that IC may not result in a decrease in frequency of substance misuse. As IC may not be the most ideal approach depending on the client’s presenting concern and therapeutic goals, counselors are ethically bound to continue ongoing assessments to collaborate with their client to determine the most appropriate treatment setting.

Implications for Counselor Education

In addition to counseling practice, the results of our scoping review provide implications for counselor education and ongoing counselor development. First, counselors or CITs that have received training in IC have commonly reported an increase in their professional identity development, as practicing in IC settings creates an opportunity for counselors and CITs to differentiate counseling responsibilities from related health care professionals (Brubaker & La Guardia, 2020; Johnson et al., 2015). Counselor educators and supervisors are encouraged to consider how they can create opportunities to challenge their students or supervisees to understand their role in the health care landscape. For example, Johnson and Freeman (2014) described an interdisciplinary health care delivery course to train counselors alongside students from other disciplines (e.g., nursing, physical therapy), and counselor educators may consider how they can form partnerships across departments to provide these opportunities. Counselor or CIT participants also expressed an enhanced self-efficacy for clinical practice (Brubaker & La Guardia, 2020; Lenz & Watson, 2023). As trainings and field experience for IC practice typically involve experiential components, counselors and CITs are provided additional opportunities to practice their previous clinical trainings in IC settings. Farrell et al. (2009) provided an example of how counselor educators can use standardized patients (i.e., paid actors simulating a presenting concern) to role-play a client in a primary setting. In such situations, the CIT can practice a variety of brief assessments (e.g., substance abuse, suicide, depression screenings) and interventions (e.g., motivational interviewing techniques, such as building ambivalence) in an IC setting.

With the counseling profession’s emphasis on aspects of valuing cultural differences and social justice, counselor educators and supervisors may consider how they can train counselors and CITs to reduce social determinants of health through integrated and collaborative practices that promote affirmative and proximal care. Counselors or CITs that received training to work in IC settings often reported higher understanding of multicultural counseling (Agaskar et al., 2021; Lenz et al., 2018). Thus, counselor educators and supervisors can provide their counselors and CITs with challenges to incorporate aspects of the MSJCC (Ratts et al., 2016) when delivering interdisciplinary care. All trainings in our review were administered across multiple modalities (e.g., face-to-face, hybrid, virtual, asynchronous), which gives counselor educators flexibility in how they train counselors or CITs. The variety in training administration is a promising result, as the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for flexible training options for counselors and CITs. In addition, counselors and CITs in rural communities often have infrequent access to training as compared to their non-rural colleagues, and thus flexibility may enhance the accessibility of IC training (Alvarez et al., 2014). Lastly, counselors and CITs being trained in IC modalities do not need to work in IC settings to use interprofessional skills developed through trainings. Heath et al. (2013) remarked that IC is not always a feasible option, but helping professionals can still apply collaborative approaches to enhance their client’s holistic outcomes. In other words, counselors or CITs may apply IC principles of preventative health care and interdisciplinary treatment plans by collaborating with other health care professionals at a distance. Glueck (2015) corroborated this notion and described a theme that counselors who have previously worked in IC settings believe they are able to provide more holistic care because they are better equipped to collaborate with health care professionals from multiple disciplines. However, these counselors also reported that they would have been more prepared to work in IC if they received training at some point in their career.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The methodology of a scoping review has noted limitations. Because of the nature of a scoping review, the data extraction process and results section are broad (Munn et al., 2018). Articles were not systematically evaluated to assess study quality, and the reader is encouraged to review a specific study before interpreting the results. In addition to study quality, scoping reviews include articles from a variety of article classifications, so the results and implications should be considered exploratory. Thus, we caution how readers draw conclusions from results presented in the included articles. Second, the search terms and inclusion criteria may have resulted in limitations. This search focused on IC; therefore, concepts such as interprofessional collaboration and interprofessional education may have been excluded. These concepts are discussed in the Heath et al. (2013) model, but they do not directly result in IC practice. Counseling and counselor education were also search terms, which may have excluded articles written by counseling scholars in journals outside of counseling and counselor education journals. Third, this review resulted in four studies that empirically investigated IC at the client level. With limited data at the client level, there are funding and advocacy sustainability concerns for IC within counseling and counselor education. Lastly, nine studies specifically provided implications for marginalized populations and multicultural competency development through an IC lens. Although Kohn-Wood and Hooper (2014) and Vogel et al. (2014) concluded that IC is a modality that advocates for the treatment of marginalized populations that have traditionally received services at unequal rates to their White, cisgender counterparts, this topic has limited representation in counseling IC literature. As discussed by Fields et al. (2023), this review demonstrates the need for understanding how the counseling professional identity rooted in social justice and advocacy may contribute to the advancement of IC services.

In light of our limitations, this review resulted in recommendations for future research directions. Conceptual articles included in this review synthesized literature on the importance of CITs and counselors understanding applications of IC, as well as potential treatment approaches to treat a variety of marginalized communities and clinical practices. Our research team recommends that counseling scholars reviewing the included conceptual articles consider how they can use the implications and future research directions to inform future research studies. These articles can also serve as support for counseling scholars who are applying for internal and external funding. Furthermore, the empirical studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses included in our review present data that can inform future research. For example, Balkin et al. (2019) and Veach et al. (2018) concluded contrasting results about IC in reducing substance abuse behaviors. Future research studies can continue researching substance misuse within IC settings to better understand evidence-based approaches to treat these populations. Twenty-one articles included recommendations for continued research at the client or consumer level, specifically for clients from marginalized communities. Counseling scholars are encouraged to stay up to date with program evaluation scholarship and implement a variety of methodical procedures to document the impact of IC on clients. Lastly, counseling scholars must advocate for continued IC literature publication within counseling and counselor education journals.

Conclusion

Our scoping review identified IC literature within counseling journals. Specifically, this review followed PRISMA-ScR protocols (Tricco et al., 2018) and identified 27 articles across 10 unique counseling journals. Most articles were within national flagship journals (such as those of ACA and AMHCA) and publication years ranged from 2004–2023. The articles in this review were organized according to their classification, and were described as either conceptual, empirical, or meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Implications for CITs, counselors, and clients were represented across each classification. Overall, IC implications from each article were positive for training and practice perceptions for CITs and counselors, as well as clinical outcomes for clients. Moving forward, authors unanimously encouraged counselor educators and counseling scholars to continue studying IC. Future scholarship would benefit from a deeper understanding of client-level implications, with an emphasis on how IC can benefit marginalized communities.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Note. Studies with an asterisk (*) are included in the scoping review.

*Agaskar, V. R., Lin, Y.-W. D., & Wambu, G. W. (2021). Outcomes of “integrated behavioral health” training: A pilot study. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 43, 386–405.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-021-09435-z

*Aitken, J. B., & Curtis, R. (2004). Integrated health care: Improving client care while providing opportunities for mental health counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 26(4), 321–331.

https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.26.4.tp35axhd0q07r3jk

*Alvarez, K., Marroquin, Y., Sandoval, L., & Carlson, C. (2014). Integrated health care best practices and culturally and linguistically competent care: Practitioner perspectives. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36(2), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.36.2.480168pxn63g8vkg

*Balkin, R. S., Lenz, A. S., Dell’Aquila, J., Gregory, H. M., Rines, M. N., & Swinford, K. E. (2019). Meta-analysis of integrated primary and behavioral health care interventions for treating substance use among adults. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 40(2), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaoc.12067

Basu, S., Landon, B. E., Williams, J. W., Jr., Bitton, A., Song, Z., & Phillips, R. S. (2017). Behavioral health integration into primary care: A microsimulation of financial implications for practices. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(12), 1330–1341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4177-9

*Brubaker, M. D., & La Guardia, A. C. (2020). Mixed-design training outcomes for fellows serving at-risk youth within integrated care settings. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(4), 446–457.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12346

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2016-Standards-with-Glossary-5.3.2018.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2022). 2024 CACREP standards, draft three. https://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Draft-3-2024-CACREP-Standards.pdf

*Crowe, A., Mullen, P. R., & Littlewood, K. (2018). Self-stigma, mental health literacy, and health outcomes in integrated care. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12201

Farrell, M. H., Kuruvilla, P., Eskra, K. L., Christopher, S. A., & Brienza, R. S. (2009). A method to quantify and compare clinicians’ assessments of patient understanding during counseling of standardized patients. Patient Education and Counseling, 77(1), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.013

Fields, A. M., Linich, K., Thompson, C. M., Saunders, M., Gonzales, S. K., & Limberg, D. (2023). A systematic review of training strategies to prepare counselors for integrated primary and behavioral healthcare. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 14(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2022.2069555

Gerrity, M. (2016). Evolving models of behavioral health integration: Evidence update 2010–2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf

Giese, A. A., & Waugh, M. (2017). Conceptual framework for integrated care: Multiple models to achieve integrated aims. In R. E. Feinstein, J. V. Connelly, & M. S. Feinstein (Eds.), Integrating behavioral health and primary care (pp. 3–16). Oxford University Press.

*Glueck, B. P. (2015). Roles, attitudes, and training needs of behavioral health clinicians in integrated primary care. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 37(2), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.37.2.p84818638n07447r

Hays, P. A. (1996). Addressing the complexities of culture and gender in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(4), 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1996.tb01876.x

Health Resources and Services Administration. (2022). Health professions training programs. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/training-programs

Heath, B., Wise-Romero, P., & Reynolds, K. A. (2013). Standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/CIHS_Framework_Final_charts.pdf?daf=375ateTbd56

*Jacobson, T., & Hatchett, G. (2014). Counseling chemically dependent chronic pain patients in an integrated care setting. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 35(1), 57–61.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1874.2014.00024.x

*Johnson, K. F., Blake, J., & Ramsey, H. E. (2021). Professional counselors’ experiences on interprofessional teams in hospital settings. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(4), 406–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12393

*Johnson, K. F., & Freeman, K. L. (2014). Integrating interprofessional education and collaboration competencies (IPEC) into mental health counselor education. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36(4), 328–344.

https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.36.4.g47567602327j510

*Johnson, K. F., Haney, T., & Rutledge, C. (2015). Educating counselors to practice interprofessionally through creative classroom experiences. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 10(4), 488–506.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2015.1044683

*Johnson, K. F., & Mahan, L. B. (2020). Interprofessional collaboration and telehealth: Useful strategies for family counselors in rural and underserved areas. The Family Journal, 28(3), 215–224.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480720934378

*Kohn-Wood, L., & Hooper, L. (2014). Cultural competency, culturally tailored care, and the primary care setting: Possible solutions to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in mental health care. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.36.2.d73h217l81tg6uv3

Kolbasovsky, A. (2008). A therapist’s guide to understanding common medical conditions: Addressing a client’s mental and physical health. W. W. Norton.

*Lenz, A. S., Dell’Aquila, J., & Balkin, R. S. (2018). Effectiveness of integrated primary and behavioral healthcare. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 40(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.40.3.06

*Lenz, A. S., & Watson, J. C. (2023). A mixed methods evaluation of an integrated primary and behavioral health training program for counseling students. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 14(1), 28–42.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2022.2063713

*Lloyd-Hazlett, J., Knight, C., Ogbeide, S., Trepal, H., & Blessing, N. (2020). Strengthening the behavioral health workforce: Spotlight on PITCH. The Professional Counselor, 10(3), 306–317.

https://doi.org/10.15241/jlh.10.3.306

McCall, M. H., Wester, K. L., Bray, J. W., Hanchate, A. D., Veach, L. J., Smart, B. D., & Wachter Morris, C. (2022). SBIRT administered by mental health counselors for hospitalized adults with substance misuse or disordered use: Evaluating hospital utilization and costs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 132, 108510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108510

*Moe, J., Johnson, K., Park, K., & Finnerty, P. (2018). Integrated behavioral health and counseling gender and sexual minority populations. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 12(4), 215–229.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2018.1526156

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119 (2010).

https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ148/PLAW-111publ148.pdf

Petterson, S., Miller, B. F., Payne-Murphy, J. C., & Phillips, R. L., Jr. (2014). Mental health treatment in the primary care setting: Patterns and pathways. Families, Systems, & Health, 32(2), 157–166.

https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000036

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

*Regal, R. A., Wheeler, N. J., Daire, A. P., & Spears, N. (2020). Childhood sexual abuse survivors undergoing cancer treatment: A case for trauma-informed integrated care. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 42(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.42.1.02

*Schmit, M. K., Watson, J. C., & Fernandez, M. A. (2018). Examining the effectiveness of integrated behavioral and primary health care treatment. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(1), 3–14.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12173

*Sheesley, A. P. (2016). Counselors within the chronic care model: Supporting weight management. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(2), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12079

Sperry, L., & Binensztok, V. (2019). Ultra-brief cognitive behavioral interventions: A new practice model for mental health and integrated care. Routledge.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf

The White House. (2022, March 1). Fact sheet: President Biden to announce strategy to address our national mental health crisis, as part of unity agenda in his first State of the Union. [Press release]. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/03/01/fact-sheet-president-biden-to-announce-strategy-to-address-our-national-mental-health-crisis-as-part-of-unity-agenda-in-his-first-state-of-the-union

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., . . . Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

*Tucker, C., Sloan, S. K., Vance, M., & Brownson, C. (2008). Integrated care in college health: A case study. Journal of College Counseling, 11(2), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2008.tb00033.x

*Ulupinar, D., Zalaquett, C., Kim, S. R., & Kulikowich, J. M. (2021). Performance of mental health counselors in integrated primary and behavioral health care. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(1), 37–46.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12352

*Veach, L. J., Moro, R. R., Miller, P., Reboussin, B. A., Ivers, N. N., Rogers, J. L., & O’Brien, M. C. (2018). Alcohol counseling in hospital trauma: Examining two brief interventions. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(3), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12199

*Vereen, L. G., Yates, C., Hudock, D., Hill, N. R., Jemmett, M., O’Donnell, J., & Knudson, S. (2018). The phenomena of collaborative practice: The impact of interprofessional education. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 40(4), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-018-9335-1

*Vogel, M., Malcore, S., Illes, R., & Kirkpatrick, H. (2014). Integrated primary care: Why you should care and how to get started. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36(2), 130–144.

https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.36.2.5312041n10767k51

*Wood, A. W., Zeligman, M., Collins, B., Foulk, M., & Gonzalez-Voller, J. (2020). Health orientation and fear of cancer: Implications for counseling and integrated care. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 42(3), 265–279. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.42.3.06

Appendix A

Conceptual Articles

| Author(s) |

Population(s) of Interest |

Research Gap Identified |

Implications and Future Directions |

| Aitken & Curtis, 2004 |

Counselor educators

and counselors |

Lack of IC literature in counselor education journals |

Increased training for counselors to work competently in IC. Increased advocacy efforts to be on insurance panels. Build relationships with other health care professionals. More literature is needed in counselor education journals. |

| Jacobson & Hatchett, 2014 |

Clients who are chemically dependent with chronic pain |

Lack of literature for clients who are chemically dependent with chronic pain |

Clients that have co-occurring chemical dependence and chronic pain have reported benefits when their symptoms are treated by mental and physical health providers. Additional research is needed to understand treatment strategy effectiveness. |

| Johnson & Freeman, 2014 |

Health care undergraduate and graduate students (including CITs)

learning IC strategies |

Lack of literature documenting IC training across multiple disciplines, specifically including CITs |

Provides a framework for IC training across multiple disciplines in accordance with SAMHSA IC competency standards. Additional research is needed to understand the effectiveness for each discipline and as a whole. |

| Johnson & Mahan, 2020 |

Family counselors

in rural and

underserved areas |

Family counselors leading connection between rural families and other providers

of health care services |

Emphasis on interprofessional collaboration (IPC) and use of telehealth options where family counselors use systemic training to advocate for rural, marginalized families, as well as network and connect families to health care providers when family members have unmet medical health needs or need specialized mental health care treatment. Additional research is needed to understand this phenomenon. |

| Kohn-Wood & Hooper, 2014 |

Mental health professionals working

in primary care settings |

How culturally tailoring evidence-based treatment models can reduce mental health disparities |

Cultural tailoring of treatments should be a primary factor that is evaluated in future research studies. Future researchers should consult existing literature on culturally tailoring treatment to increase engagement and improve outcomes for diverse groups. |

|

|

|

|

| Lloyd-Hazlett et al., 2020 |

CITs |

Need for a replicable model

to train CITs in IC |

The Program for the Integrated Training of Counselors in Behavioral Health (PITCH) model creates community partnerships, introduces CITs to applications of IC, and awards CITs a graduate certificate. Additional research is needed to demonstrate sustainability. |

| Moe et al., 2018 |

LGBTQ+ clients |

Lack of LGBTQ+ literature pertaining to IC |

CITs, counselors, and other health care professionals working with LGBTQ clients may benefit from additional training and supervision in collaborative care and IC. Additional research is needed to understand the impact IC has with the LGBTQ+ population. |

| Regal et al., 2020 |

Clients with cancer who are survivors of childhood sexual abuse |

Lack of trauma-informed

care literature pertaining

to IC, specifically for individuals with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) |

IC offers opportunities for appropriate assessments to identify ACEs for holistic care, as represented in the case study. Additional research is needed to understand universal screening for ACEs and the integration of trauma-informed practices within traditional primary care settings. |

| Sheesley, 2016 |

Counselor educators, counselors, and primary care settings |

Elaborate on the role of mental health counselors within the Chronic Care Model (CCM) |

Counselors influencing the future of obesity treatment within the CCM. Additional research is needed to understand evidence-based practices for counselors within the CCM for the treatment of obesity. |

| Tucker et al., 2008 |

An international student’s experience receiving IC on a college campus |

The effect of an IC program and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MCBT) approach |

As reported by the multidisciplinary team, clients using medication and individual and group therapy improved from the first time they had met. The authors emphasized the use of MCBT in treatment. Additional research is needed for IC on college campuses. |

| Vogel et al., 2014 |

Counselors considering IPC |

Access issues, adherence, and the effectiveness of IPC with particular attention to culturally diverse groups |

Increased training in evidence-based culturally tailored practices. Increased education for counselors regarding IPC to help determine if primary care is a good fit. Additional research is needed on various aspects of successful IPC execution. |

Appendix B

Empirical Articles

| Author(s) |

Methodology |

N and

Participant

Profile |

Research of Interest |

Results |

Agaskar

et al., 2021 |

Mixed methods; quantitative: single-group design; qualitative: thematic analysis |

12 CITs |

The effect of an IPC and evidence-based practices curriculum to enhance students’ ability to work with at-risk youth in IC settings |

CITs reported an increase in multicultural competence and ability to work on IC teams, utilize evidence-based practices, and implement suicide interventions. |

Alvarez

et al., 2014 |

Qualitative; exploratory

cross-case synthesis |

8 service providers in an IC setting |

The experiences of IC service providers working with culturally and linguistically diverse populations |

Three themes emerged: (a) patient-centered care benefits underserved populations, (b) desirability of a multidisciplinary team, and

(c) importance of the organization to change with circumstances. |

| Brubaker & La Guardia, 2020 |

Quantitative;

single case and quasi-experimental |

11 CITs |

The effect of an IC training intervention, Serving At-Risk Youth Fellowship Experience for Counselors (SAFE-C) |

CITs reported an increase in understanding professional identity, self-efficacy, and interprofessional socialization. |

Crowe

et al., 2017 |

Quantitative;

Cross-sectional survey design |

102 clients from an IC medical facility |

To examine the relationship between mental health self-stigmas, mental health literacy, and health care outcomes |

Self-stigma of mental illness and self-stigma of seeking help had an inverse relationship with mental health literacy. |

| Glueck 2015 |

Qualitative; phenomenological |

10 mental health professionals working in IC settings |

Roles and attitudes of mental health professionals working in IC and perceived training needs |

Mental health professionals reported that they were involved in brief interventions and assessments, administrative work, and consultation and that additional graduate training is needed in classroom and field experiences. |

Johnson

et al., 2015 |

Mixed methods; qualitative: the pre- and post-survey design; qualitative: thematic analysis |

22 CITs, as well as dental hygiene, nursing, and

physical therapy students |

CITs’ attitudes toward interprofessional learning and collaboration following an interdisciplinary course on IPC |

Perceptions about learning together and collaboration improved, negative professional identity scores decreased, and higher reports of positive professional identity. |

Johnson

et al., 2021 |

Qualitative; phenomenology |

11 counselors in hospital setting |

Experiences of counselors working on interprofessional teams (IPTs) in a hospital setting |

Four themes emerged:

(a) counselors rely on common factors and foundational principles; (b) counselors must have interprofessional supervision; (c) counselors must remember their scope of practice; and (d) counselors must adhere to ethical codes and advocacy standards. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Lenz & Watson, 2023 |

Mixed-methods; quantitative: non-experimental pre- and post-test; qualitative: thematic analysis |

45 CITs |

The impact an IC training program has on CITs’ self-efficacy, interprofessional socialization, and multicultural competence, as well as barriers to student growth |

Increase in self-efficacy, interprofessional socialization, and aspects of multicultural competence. Most reported barriers were IC awareness and organizational constraints. |

Schmit

et al., 2018 |

Quantitative;

quasi-experimental |

196 clients; 98 received IC and 98 received treatment as usual (TAU) |

The effect of IC for individuals with severe mental illness compared

to TAU |

Group that received the IC intervention demonstrated an improvement in overall functioning, including a

decrease in crisis events. |

| Ulupinar et al., 2021 |

Quantitative;

quasi-experimental |

1,747 clients and 10 counselors |

To examine the therapeutic outcomes and client dropout rates of adults experiencing mental disorders in an IC center |

The addition of counselors resulted in a decrease in client symptom reports. |

Veach

et al., 2018 |

Quantitative; pre- and post-test survey |

333 clients in a trauma-based IC center |

A brief IC counseling intervention for risky alcohol behavior |

The IC counseling intervention resulted in reduced risky alcohol behaviors. |

Vereen

et al., 2018 |

Qualitative; phenomenological inquiry |

13 graduate students; five CITs and eight speech– language pathologists |

The effect of interprofessional education (IPE) on the development of collaborative practice for both CITs and speech– language pathologists-in-training |

Five themes emerged:

(a) benefits of IPE,

(b) expectations of collaborative practice, (c) benefits of experienced IC providers,

(d) challenges of IC practice, and

(e) optimization of IC practice. |

Wood

et al., 2020 |

Quantitative;

cross-sectional survey design |

155 undergraduate students studying psychology and aspects of counseling |

How factors related to prevention and wellness relate to topics that counselors are adept at addressing, such as optimism, social support, and resilience |

Results indicated that health anxiety was positively correlated with fear of cancer, but that psychosocial variables either had no relationship or were not significant moderators between health anxiety and fear of cancer. |

Appendix C

Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews

| Author(s) |

Article Classification |

Population of Interest |

Number

of Included Studies and Participants |

Results and Implications |

Balkin

et al., 2019 |

Meta-analysis |

Adults with substance use disorders |

8 studies with 1,545 participants;

722 received IC and 823

received alternative |

Effects of IC were small with this sample (i.e., small effect in decrease in substance use).

Authors recommended additional research to understand substance use disorders within an IC context and variables beyond use of substances. |

Fields

et al., 2023 |

Systematic review |

Mental health professionals and mental health professionals-in-training receiving education on IC |

18 studies |

Four themes emerged:

(a) HRSA-funded studies,

(b) trainee skill development, (c) enhancement of

self-efficacy, and

(d) increased understanding of interprofessional collaboration. Authors recommended more studies focusing on client-level data and more multicultural competencies. |

|

|

|

|

|

Lenz

et al., 2018 |

Meta-analysis |

Individuals receiving mental health care in traditional primary care settings |

36 studies with 14,764 participants |

Effects of IC, as compared to alternative treatments, resulted in a decrease in mental health symptoms. A greater effect is shown with a larger treatment team and number of behavioral health sessions. |

Alexander M. Fields, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Cara M. Thompson, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Kara M. Schneider, MS, is a doctoral candidate at the University of South Carolina. Lucas M. Perez, MA, is a doctoral candidate at the University of South Carolina. Kaitlyn Reaves, BS, is a doctoral student at Adler University. Kathryn Linich, PhD, is a clinical assistant professor at Duquesne University. Dodie Limberg, PhD, is an associate professor at the University of South Carolina. Correspondence may be addressed to Alexander M. Fields, University of Nebraska at Omaha, College of Education, Health, and Human Services, Department of Counseling, Omaha, NE 68182, alexanderfields@unomaha.edu.

Dec 16, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 4

Gideon Litherland, Gretchen Schulthes

The aim of this study was to develop an understanding of the research scholarship focused on doctoral-level counselor education. Using the 2016 Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) doctoral standards as a frame to understand coverage of the research, we employed a scoping review methodology across four databases: ERIC, GaleOneFile, PsycINFO, and PubMed. Research between 2005 and 2019 was examined which resulted in identification of 39 articles covering at least one of the 2016 CACREP doctoral core areas. Implications for counseling researchers and counselor educators are discussed. This scoping research demonstrates the limited corpus of research on doctoral-level counselor education and highlights the need for future, organized scholarship.

Keywords: scoping review, doctoral-level counselor education, 2016 CACREP doctoral standards, counseling researchers, counselor educators

Counselor educators are positioned to be at the vanguard of research, teaching, and practice within the counseling profession (Okech & Rubel, 2018; Sears & Davis, 2003). The training of counselor educators is concentrated in the pursuit of doctoral degrees (e.g., PhD, EdD) in counselor education and supervision. Doctoral-level education of counselor educators is thus critical to the development of future leaders for the counseling profession (Goodrich et al., 2011). Counselor education doctoral students (CEDS) enrolled within programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) engage in advanced training in leadership, supervision, research, counseling, and teaching (CACREP, 2009, 2015; Del Rio & Mieling, 2012). CEDS complete academic coursework, participate in practicum and internship fieldwork, and deepen their professional counselor identity (Calley & Hawley, 2008; Limberg et al., 2013). Upon graduation, it is expected that CEDS are prepared to competently assume the responsibilities of a counselor educator. Counselor educators go on to work in any myriad of roles—professional and business leadership positions, academia, clinical and community settings, and consultation practices across the country (Bernard, 2006; Curtis & Sherlock, 2006; Gibson et al., 2015). It is imperative, then, for doctoral-level education to prepare and deliberately challenge these future counselor educators (Protivnak & Foss, 2009).

Historically, there have been concerns regarding the level of sustainability within the profession and the need for more qualified counselor educators (Isaacs & Sabella, 2013; Maples, 1989; Maples et al., 1993; Woo, Lu, Henfield, & Bang, 2017). Holding the terminal degree for the profession (Adkison-Bradley, 2013; CACREP, 2009; Goodrich et al., 2011), graduating CEDS meet the increasing demands across the country for trainers of a qualified workforce of school, college, rehabilitation, clinical mental health, addictions, and family counselors who can meet the psychosocial well-being needs of a diverse global population. There is an increasing need for counselors in all specialty areas, given recent projections of the next decade from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019). The needs of communities (e.g., criminalization of mental illness; Bernstein & Seltzer, 2003; Dvoskin et al., 2020), training programs (e.g., multicultural counseling preparedness; Celinska & Swazo, 2016; Zalaquett et al., 2008), and public mental health issues (e.g., suicide; Gordon et al., 2020) reflect the urgency for a qualified workforce that can serve clients, students, and a global economy (Lloyd et al., 2010; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d.-a, n.d.-b). Because of the demand for such a workforce, the counseling profession and its institutions must be prepared to educate counselor educators who, in turn, lead, teach, supervise, and mentor future generations of helping professionals. Given these market demands, it is important to consider: To what degree are CEDS being prepared to meet these demands in their post-graduation roles? How are CEDS being prepared to meet such demands? What evidence exists to guide the training and development of CEDS?

Based on available data from official CACREP annual reports, from 2012 to 2018, the number of CACREP-accredited counselor education doctoral programs increased from 60 to 85 (CACREP, 2013, 2019). In the same time period, the number of enrolled CEDS grew from 2,028 to 2,917. The number of doctoral program graduates similarly increased from 323 to 479. This interest and investment in accredited doctoral programs at universities across the country warrants greater research attention to better understand, focus on, and shape the doctoral-level education of future counselor educators. A great deal rests on preparation of future counselor educators as they maintain the primary responsibility for leading the profession as standard-bearers and gatekeepers.

Research on counselor education doctoral study is essential for improving and maintaining the efficacy of doctoral training because CEDS are the future leaders, faculty members, supervisors, and advocates of the profession. A critical step toward facilitating research on counselor education doctoral study is a scoping review (Tricco et al., 2018). Scoping review methodology has previously been used within counseling and mental health research (e.g., Harms et al., 2020; Meekums et al., 2016). Such a review can assist in constructing a snapshot of the breadth and focus of the extant research.

CACREP Core Areas as a Useful Framework for Analysis

The 2016 CACREP Standards (CACREP, 2015) delineate core areas of doctoral education and provide a meaningful and accessible framework appropriate to assess the state of doctoral-level education and training of CEDS. CACREP develops accreditation standards through an iterative research process that capitalizes on counseling program survey feedback, professional conference feedback sessions, and research within the counseling profession (Bobby, 2013; Bobby & Urofsky, 2008; Leahy et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2012). CACREP publishes updated accreditation standards that are publicly available online, on average, every 7 years (Perkins, 2017). The 2016 CACREP Standards (2015) articulate core areas of doctoral-level education and training in counselor education that align with professional expectations of performance upon graduation. These areas include leadership/advocacy, counseling, professional identity, teaching, supervision, and research. These core areas aim to guide faculty in fostering the development of counselor educator identity and professional competence.

The 2016 CACREP (2015) doctoral-level core areas serve as a professionally relevant framework to examine the extant research addressing doctoral-level education and training of CEDS. Previous research has utilized CACREP master’s-level core areas for content analysis (Diambra et al., 2011). Although much research within the field of counseling and other helping professions addresses the experiences and training needs of master’s-level practitioners, there is seemingly scant published research addressing the education and training of CEDS. To arrive at a clearer understanding of this gap, a framework of analysis (e.g., the 2016 CACREP doctoral-level core domains) is necessary in order to furnish a status report of the current research addressing doctoral-level education and training of CEDS.

Employing the 2016 CACREP (2015) doctoral standards core areas as a frame through which to view the research emphasizes the importance of accreditation and professional counselor identity. Doctoral core areas directly relate to the domain-driven framework employed in this study. In order to achieve a focused understanding of coverage of the CACREP core areas, the framework employed within this study conceptualizes each core area as a domain with two distinct differences: (a) distinguishing between leadership and advocacy in separate domains and (b) inclusion of professional identity as its own domain. The domains of our framework included Professional Identity, Supervision, Counseling, Teaching, Research, Leadership, and Advocacy. By systematically mapping the research conducted in each area of counselor education, we aimed to identify existing gaps in knowledge as a means to focus future research efforts. In this scoping review, the primary research question was “What is the coverage of the 2016 CACREP doctoral standards within the research over the past 15 years?” Research subquestions included (a) How many studies “fit” into each of the doctoral standard domains? (b) What frequency trends were present within the data related to type of research (qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods)? (c) What publication trends were present within the data related to (i) year of publication, (ii) profession-based affiliation of the publishing journal, and (iii) the publishing journal? and (d) What other foci emerged that were not addressed by the CACREP 2016 doctoral program standards?

Methods

In order to address the primary research question and related subquestions in a systematic way, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocol (PRISMA-P; Moher et al., 2015) was considered. The PRISMA-P articulates critical components of a systematic review and aims to “reduce arbitrariness in decision-making” (Moher et al., 2015, p. 1) by facilitating a priori guidelines—with a goal of replicability. However, given the general-focus nature of the research question, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018) was more appropriate.

The PRISMA-ScR is an extension of the PRISMA-P with a broader focus on mapping “evidence on a topic and identify[ing] main concepts, theories, sources, and knowledge gaps” (Tricco et al., 2018, p. 467). The following steps, or items, of the PRISMA-ScR are described further in subsequent sections, including: primary and sub-research questions (Item 4), eligibility criteria (Item 5), exclusion criteria (Item 6), database sources (Item 7), search strategy (Item 8), data charting process (Item 10), data items (Item 11), and synthesis of results (Item 14). Items of the protocol not specifically listed here are satisfied by structural elements of this article (e.g., title [Item 1] and rationale [Item 3]).

Eligibility Criteria

For the present study, articles were only considered eligible for inclusion if they had been published in a peer-reviewed journal between 2005–2019. To be included in the study, articles were required to be research-based with an identified methodology (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods), primarily focused on some aspect of counselor education doctoral study (e.g., program, student, faculty, outcomes, process), and published in the English language. Articles were considered primarily focused on counselor education doctoral study if their research questions, study design, and implications directly bore relevance to the scholarship of doctoral counselor education. Excluded from the study were published dissertation work, magazines, conference proceedings, and other non–peer-reviewed publications. Position, policy, or practice pieces; case studies; conceptual articles; and theoretical articles also were excluded. The primary focus of the study could not be outside of counselor education doctoral study.

Information Sources

To identify articles for inclusion, the following databases were searched: PubMed, ERIC, GaleOneFile, and PsycINFO. We also utilized reference review (backward snowballing) as an additional information source (Jalali & Wohlin, 2012; Skoglund & Runeson, 2009).

Search

Each database was searched with a specific keyword, “counselor education doc*,” followed by a topical search term. The asterisk (*) was deliberate in the search term to inclusively capture all permutations of “doc,” such as doctoral or doctorate. Search terms were derived from the rationale for the present study and CACREP doctoral core areas. The search terms were: “research,” “empirical,” “counseling,” “doctoral program standards,” “peer-reviewed research,” “CACREP,” “doctorate,” “quantitative,” “program,” “student,” “faculty,” “outcomes,” “process,” “professional identity,” “counseling,” “supervision,” “teaching,” “leadership,” and “advocacy.” Researchers divided the search terms, while maintaining the keyword “counselor education doc*,” and independently ran systematic searches using any eligibility criteria (e.g., inclusive years) that the database could sort. Inclusion criteria, including search terms and keyword, were entered into the search query tool and the results exported. Results from each database search were delineated on a yield list for later screening.

In order to increase methodological consistency among researchers, each utilized a search yield matrix (Goldman & Schmalz, 2004). Results from each researcher’s yield list were organized within the search yield matrix using three fields: article title, authors, and year of publication. This allowed for cleaner comparison of articles and continued identification of duplicates throughout the screening processes. Duplicate entries were collapsed to one citation so that only one entry per article remained, regardless of database origin. Each researcher conducted a preliminary screening of article titles with the inclusion criteria.

Selection of Sources of Evidence

In order to systematically screen articles and produce a final list for data collection, three levels of screening were conducted for the entire yield. Level 1, 2, and 3 screenings are described in detail below.

Level 1 Screening

Each researcher scanned their own yield list (duplicates removed). Every citation’s title was examined for preliminary eligibility. Researchers agreed to engage in an inclusive scan of titles and pass articles on to Level 2 screening if they seemed at all relevant to doctoral counselor education. Researchers indicated an article’s fitness for inclusion by a simple “yes” or “no” note on the Level 1 screening instrument. The yield from Level 1 screening was considered adequate for further review and moved on to Level 2 screening.

Level 2 Screening

Using the results from the Level 1 screening, each researcher scanned the other’s “for inclusion” list. Each citation’s abstract was examined for eligibility. Researchers indicated an article’s fitness for inclusion by a simple “yes” or “no” note on the Level 2 screening instrument. The yield from Level 2 screening was considered adequate for further review and moved on to Level 3 screening.

Level 3 Screening

Using the results from the Level 2 screening, researchers combined their lists and consolidated duplicates. Each article’s full text was examined for eligibility by each researcher. Researchers indicated an article’s fitness for inclusion by a simple “yes” or “no” note on the Level 3 screening instrument. In order to avoid bias or influence, each researcher conducted their screening work on a separate document. In reviewing eligibility indicators, researchers sought resolution through discussion, review of eligibility criteria, and assessment of an article’s scholarly focus. This process of Level 1, 2, and 3 screening resulted in a unified list.

Reference Review

In order to identify potential articles for inclusion that were missed or unintentionally excluded from the search process, researchers conducted a reference review strategy (Jalali & Wohlin, 2012; Skoglund & Runeson, 2009) on the unified list. The reference review consisted of examining the reference section of every article that was selected for inclusion in the unified list. Researchers examined the reference section for relevant titles (Level 1 screening) and endorsed each article according to “yes” or “no” for inclusion. If an article was determined possibly eligible for inclusion, a full-text examination (Level 3 screening) was conducted to determine further eligibility. Any articles determined to be eligible for inclusion were then added to the unified list.

Data Charting Process and Data Items

In the data charting process, we employed a matrix strategy (Goldman & Schmalz, 2004). Data was collected and organized within a data collection matrix instrument. We created the data collection matrix instrument to organize and focus data collection.

Data items included: year of publication, publishing journal, professional affiliation of publishing journal, type of methodology (e.g., qualitative, quantitative), and domain fitness (i.e., Counseling, Supervision, Teaching, Professional Identity, Research, Leadership, or Advocacy). If other themes were identified that did not fit within the domains, those were noted for later review.

To collect data, we divided the unified list into two halves and then independently charted the data for each citation in the data collection matrix instrument. To determine the professional affiliation of the publishing journal, we reviewed the public-facing website of each journal and reviewed the information available. To determine domain coverage, we reviewed the aim, research question(s), and discussion section of each article and compared the focus of the article to the 2016 CACREP doctoral core area descriptions. For example, if a study focused on the experience of CEDS becoming supervisors, this was coded as “Supervision.” If, however, a study’s aim and research question focused on an area of counselor education doctoral study that was not covered by a domain, then it was coded as “Other Focus.” Researchers discussed articles coded as “Other Focus” and worked to collapse similar foci under broad categories for ease of reporting.

Of note, researchers did not consider articles that utilized CEDS within a sample or participant pool as automatically eligible for inclusion. Studies were only included if doctoral-level counselor education was a key component or focal point of the research inquiry. Every effort was made to ensure study appropriateness for review based on these criteria.

Synthesis of Results

We analyzed the results after data collection through descriptive statistics and basic data visualization of trends (e.g., frequency, type). We discussed each research subquestion, considered what data best addressed the question, and reviewed data for any trends. Having described the process of the scoping review, the results of the study are presented next according to the preferred reporting items for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., 2018).

Results

Selection of Sources

A total of 9,798 citations were initially retrieved from the ERIC (n = 1,012), GaleOneFile (n = 327), PsycINFO (n = 1,298) and PubMed (n = 7,161) databases. After an initial review of citation type (e.g., book, white paper) and removal of duplicates, 3,076 articles remained. The Level 1 screening captured 2,599 ineligible articles not meeting the inclusion criteria. Therefore, at the end of the Level 1 screening, 477 citations remained. The Level 2 screening captured 292 ineligible articles that did not meet inclusion criteria, resulting in 185 articles. As researchers combined lists for Level 3 screening and identified duplicates, 185 articles reduced to 123. The Level 3 screening captured 52 ineligible articles that did not meet inclusion criteria, resulting in 71 articles for the unified list. Articles from the reference review yield (n = 9) were screened and added to the unified list. The unified list initially consisted of 80 citations. However, three articles were removed as a result of data cleaning (e.g., text-based differences not previously captured by sorting tool) and/or not meeting inclusion criteria (e.g., inaccuracies in published article’s references). Therefore, 77 articles were selected for inclusion within the present scoping review.

Coverage of CACREP Doctoral Domains