Angel Riddick Dowden, Jessica Decuir Gunby, Jeffrey M. Warren, Quintin Boston

This article reports the results of a phenomenological study of racial identity development that asked the following questions: How do African-American males cope with invisibility experiences? What role do counselors play in assisting African-American males cope with invisibility experiences? The study involved the use of semi-structured interviews to explore invisibility experiences among seven African-American males. Results identified four thematic codes: self-affirmation, self-awareness, coping strategies in overcoming invisibility, and providing effective counseling to African-American males.

Keywords: racial identity development, African-American males, counselors, self-affirmation, self-awareness

The classic novel Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (1952) explores the philosophical and psychological world of the main character, whose name is left unsaid in the novel to further perpetuate his invisibility. The metaphorical novel demonstrates how racism and racial epithets can harm the mind of the African-American man. Additionally, the novel reveals how the identity of the African-American man is often defined by social prejudice versus the individual self.

Consistent with the lives of many African-American men (Franklin, 1999), the nameless main character in Ellison’s novel spends his life searching for justice in the face of injustice. Ellison (1952) makes use of ambiguous struggles to represent the moral, mental and emotional frustration that results from the main character’s search for identity in a world that treats him as if he is invisible. The nameless main character represents the lives of many African-American men in American society whose daily struggles with invisibility contribute to feelings of anger, frustration, inferiority and alienation.

With the novel in mind, the authors of this article explore the concept of invisibility among African-American males in today’s society and demonstrate the impact that invisibility experiences have on racial identity. An initial discussion of the concept of invisibility is provided. Next, nigrescence theory is used as the theoretical underpinning of racial identity development.

Understanding Invisibility

Invisibility is defined as “an inner struggle with the feeling that one’s talents, abilities, personality, and worth are not valued or even recognized because of prejudice and racism” (Franklin, 1999, p. 761). This concept is often demonstrated through devaluing, demeaning, disadvantaging and the unfair regard that African-American males are subjected to on a daily basis (Franklin, 1999).

According to Franklin (1999), for some African-Americans, “being able to discern when behavior is racist, and then acting consistent with one’s sense of self, is the personal struggle for visibility” (p. 764). Racial experiences influence African-American males’ sense of self. Therefore, the negotiation of visibility that some African-American men encounter becomes a process of seeking validation, respect and dignity with or without compromising their identity. On the other hand, limited identity development or a lack of self-concept can result in identity erosion (e.g., alienation, invisibility, identity confusion; Cross & Vandiver, 2003). Moreover, racial identity development can act as a defense against the invisibility syndrome (Parham, 1999).

To that end, Parham (1999) warns that African-American people must be cautious where they seek validation, stating that it is damaging to seek validation from the oppressor, especially when that validation is “disaffirming and dehumanizing” (Parham, 1999, p. 800). In The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois (1903) expounds on this phenomenon by stating the following:

It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder (pp. 8–9).

Parham (1999) states that when personal affirmations and basic needs are not met as a result of racism, African-Americans may be prone to exhibit high-risk behaviors.

Nigrescence Theory: Correlations Between Racial Identity and Invisibility

Nigrescence theory has been revisited and revised over the course of 40 years to its current expanded version (Cross, 1991; Cross & Vandiver, 2003). Nigrescence theory expanded (the theory’s most current name and version) is utilized for the purpose of this study to provide a foundation for racial identity development and to validate the correlation between racial identity development and invisibility. While other theoretical underpinning could be employed as the foundation for racial identity development (e.g., critical race theory), expanded nigrescence theory was chosen because of its emphasis on psychological themes in the social history of Black/African-American people (Cross & Vandiver, 2003). As such, the first author provides a brief exploration of the experiences of Black people in the context of nigrescence theory in order to provide foundational information to support the correlation between invisibility and racial identity development, and this research.

The extant literature and empirical research relative to Cross’s nigrescence theory is immense (Cross, 1991; Cross & Vandiver, 2003). Inasmuch, this discussion moves beyond providing a review of the expanded theory itself. Instead emphasis is placed on central elements of nigrescence theory expanded that align with the goals of the present study.

The term nigrescence means “the process of becoming Black” (Cross, 1991). The theory’s theme revolves around the processes involved in developing Black racial and cultural identity (Cross, 2003). Core precepts of nigrescence theory expanded include the following: (a) Blackness is viewed as a social identity and not a personality variable; (b) various types of Black identity have resulted in the delineation of a range of identity exemplars; and (c) the best way to conceptualize Black identity variability is through the explications of ideological types (profiles); with the different types or interpretations of what it means to be Black at the heart of the theory (Cross & Vandiver, 2003).

Being Black/African-American is not just about skin color or the origin of descendants; it is equally related to how Black people define themselves in a society that perpetuates prejudice, racism, microaggression, separation and exclusion (Gibson & Obgu, 1991). According to Cross & Vandiver (2003), the core of nigrescence theory expanded focuses on various ways Black people make sense of themselves as social beings rather than a collection of personality traits.

Both past and present racism may impede African-American males’ ability to form an identity that includes “independence, success and achievement” (Oyserman, Gant, & Ager, 1995, p. 1219). However, identity development is essential in the promotion of well-being over the lifespan (Oyserman et al., 1995). Additionally, a well-established sense of self improves the ability to organize and interpret social experiences, regulate affect, control behavior, and develop healthy cognition (Cross & Vandiver, 2003; Oyserman et al., 1995). Without it, African-American males experience misinterpreted social experiences, self-blame, and guilt, which over time can limit education attainment, occupation attainment, and personal fulfillment (Gibson & Ogbu, 1991). It is the correlation between racial identity and invisibility, and the resulting issues, that are at the root of this study.

Research Rationale

The purpose of this phenomenological study is to answer the following research questions: How do African-American men cope with invisibility experiences? What role might counselors play in assisting African-American males cope with invisibility experiences? To answer these questions, the authors explored the lived invisibility experiences of seven African-American males.

Philosophical and Theoretical Underpinning

At the core of the study’s purpose is a humanistic and multicultural perspective. Tenets consistent with both humanistic (Scholl, 2008) and multicultural (Sue, Ivey, & Pedersen, 1996) theories are interwoven throughout the study. Specifically, emphasis is placed on empathy, self-awareness, and understanding and valuing all human beings.

With humanism and multiculturalism in mind, a phenomenological approach was utilized in the study to gather the firsthand accounts of the invisibility experiences of African-American males when encountering macro and micro forms of racism. Additionally, a constructivist approach was activated with the purpose of understanding the human experience through narrative conceptions of the phenomena (Hays & Wood, 2011). By utilizing a constructivist perspective, additional attention was placed on putting forth the participants’ perspective and ensuring contextual relevance (Hays & Wood, 2011).

Phenomenological research captures the lived experiences of people (Levers et al., 2008). Phenomenological researchers study the essence of a phenomenon and explore how individuals situate themselves in the world based on how they make meaning of their experiences (Levers et al., 2008). Utilizing a phenomenological approach in this study helps professional counselors better understand African-American male invisibility experiences. The data gathered during the study were thematically categorized and used to provide specific recommendations for counselors working with African-American males of all ages in diverse clinical settings.

Primary Researcher Bias and Influence on the Study

As an African-American female who has heard a lifetime of stories about invisibility incidents from African-American males, read about invisibility syndrome (Ellison, 1952; Franklin, 1999), as well as experienced personal feelings of invisibility, the first author decided to make a conscious effort to suspend self-knowledge about invisibility in order to entirely engage in the experiences of the participants. While bracketing personal experiences was challenging, it was an important step in ensuring that as the researcher, the author (a) treated the participants with empathy, (b) put forward the lived experience of the participants and not personal experience, and (c) maintained the trustworthiness needed to support the essence of the study, while also reporting the findings.

To avoid inferring assumptions or biases related to the topic, the first author used reflexive journaling throughout the data collection, data analysis and reporting of findings. Journaling allowed the author to maintain the trustworthiness, or the ability to ensure that the voices of the participants, and not the author’s own, were present in the study (Hunt, 2011). During reflexive journaling, the author wrote about experiences as the primary researcher, including experiences during the interviews, about feelings, thoughts, and reactions to newly discovered information, as well as emerging awareness of the phenomenon. The author often referred back to personal writing with the goal of separating perceptions from the actual information relayed by participants. Reflexive journaling increased the level of self-awareness and allowed the author to maintain trustworthiness throughout the study.

Method

Participants

Purposeful sampling was used in qualitative research to select participants who could provide a description of the phenomenon being studied (Creswell, 2007). A snowball sampling process was used to select participants for the study. That is, initial participants were identified, interviewed, and then asked to provide the names of other individuals who might be interested in participating in the study. Individuals selected as participants had to be willing to recall and describe their experiences related to the phenomenon.

Seven African-American males, ages 34–47, participated in the study. All participants identified as middle class, and five had an educational level beyond high school graduation (four master’s level and one doctorate level). Five of the participants were born in the southeast US and two were born in the northeast US. The participants also reported their familial status: one participant was single, five were married with children, and one participant was in a committed live-in relationship.

Data Collection Procedures

The participants’ subjective, personal perspective and interpretation of the phenomenon was explored. The participants engaged in semi-structured interviews by responding to interview questions and engaging in discussion related to the phenomenon. The semi-structured interview questions used in this study derived from reviewed literature on invisibility and racial identity development (Cross, 1991; Cross & Vandiver, 2003; Dubois, 1903; Parham, 1999). Interview questions focused on the derivation of the participants’ identity development, invisibility experiences (i.e., have you ever felt invisible?), ability to cope with invisibility, overall behaviors resulting from invisibility syndrome, and potential counseling to improve and/or nurture identity development.

Participants signed Institutional Review Board-approved documents prior to participating in interviews for the study. Participants agreed to allow direct information from the interviews to be utilized within the study. Data was collected in April and May 2011. Interviews were held either face-to-face or through telephone conference. Face-to-face interviews took place at various locations (e.g., library, office). Interviews and discussion lasted approximately 1–1.5 hours. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

A phenomenological model outlined by Wertz (2005) that synthesizes Giorgi’s (1985) description-reduction-interpretation model was used for the data analysis of this study. From this well-established philosophy for analyzing phenomenological data, three essential steps became capstones for the data analysis of this study. Those steps were as follows: (a) providing an exhaustive description of the phenomenon, (b) reducing and categorizing the data, and (c) interpretation.

Step 1 was important in that a clear understanding of the phenomenon was presented from the participants’ perspective. For example, participants were asked if they had ever felt invisible. This question became the catalyst of the analysis and shaped the foundation of the exploration of the phenomenon. The exhaustive description provides readers an understanding of the essence of the lived experiences and represents a unifying structure of the phenomenon (Wang, 2008).

In step 2, information was categorized and coded, themes were developed and defined, and rich descriptions of the themes based on information gathered from parts of the interviews were constructed. Themes were developed and defined by transcribing the audiotapes, and then participating in rote review and reading of the material. This process led to the delineation of significant information within the interviews, the cross-verification of information gathered among interviews, and the charting of information. From this process, information was reviewed as parts of a whole in order to develop main themes.

For example, during the transcription and review of the data, it became evident that participants relied on self-affirmation to maintain or improve racial identity development. Participants continuously spoke about affirming who they are or having to strongly defend or uphold who they are in public. It was evident that this affirmation was essential to the participants. During cross-verification, it became clear that all participants utilized self-affirmation and believed it to be essential to racial identity development. As a result, self-affirmation became an essential theme when coping with invisibility experiences.

In step 3, data was interpreted in the context of invisibility and racial identity development. During this process themes were consistently revisited with the goal of determining how they related to invisibility and racial identity development. Participants were able to review the codes and themes for clarity after data was analyzed. The interpretation of data provided probable meanings and was utilized in the development of the implications section. Reflexive journaling was an especially important aspect of step 3 as it assisted in the maintenance of trustworthiness.

Results

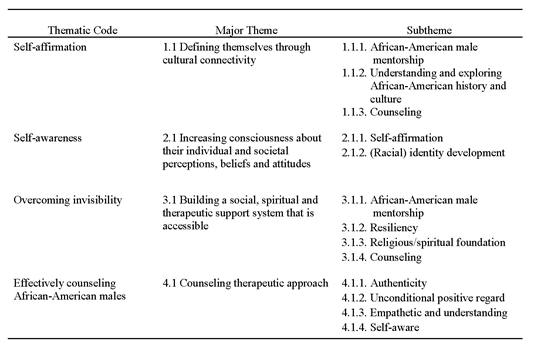

The data analysis resulted in an exhaustive description of the phenomenon and the emergence of four interconnected themes: self-affirmations, self-awareness, coping with invisibility, and providing effective counseling to African-American males. A personal account of invisibility is provided through the lens of each participant. This is followed by coded descriptions of each thematic code, major and subtheme. The thematic codes, majors and subthemes have been coded and identified below and summarized in Table 1. The findings highlight this thematic information.

Invisibility Experiences

Participant #1. I’ve felt invisible in the sense that if you don’t engage yourself in their [White people’s] beliefs, have things in common or join the social crowd you are treated invisible. For me my cultural differences have caused me to be treated invisible. For example, I’ve been in situations where I felt like White people did not really want to interact with me if they didn’t have to. I can tell this because of there is a level of avoidance even when they are, to some degree, forced into communicating. There’s a barrier there. Oftentimes there’s a lack of eye contact. Their avoidance makes me feel invisible because at the same time you see how they interact with their own [other White people]. When you do talk with them, they are very diplomatic, very politically correct, very careful. At times, I think this is how they communicate with anyone they don’t know, but for me I know it’s associated with race. I mean this is something that as an African-American male you deal with pretty regularly.

Table 1

Thematic Overview of Phenomenological Analysis of Invisibility

Participant #2. I probably feel invisible the majority of the time. I’ve learned to cope with it. It’s just a part of my reality, but at times it’s stressful. Sometimes it’s hard for me to assess some of this stuff because it’s so normal for me. I’m a faculty member at this university and certain people know me in classes and in my college, but as soon as I walk out of the building I don’t perceive that people see me as a professor. Not that people have to recognize that I’m a professor, but I don’t think that I’m viewed with the respect that any professional should have in any public space. Going into department stores I feel special when a sales person acknowledges me…I’m grateful and I want to do business with them because they’ve demonstrated to me that they are culturally competent, kind, a decent person because most times I’m looked over. I prepare myself for what I have to deal with. I’m very capable and competent…negotiating these things [race, invisibility] because I’ve had to do it. I’ve even watched my mother do it when I was a child.

Participant #3. I’ve been ignored at times; times when I felt like my opinion didn’t matter. When I was in undergrad at [name of university removed] I was meeting with my advisor. I was sharing with him my concern about pursuing my bachelor’s degree in physics and when I was telling him about my experience and how I felt about it, he expressed to me that I may have some type of learning disability. At that point, I felt like okay, in other words he was ignoring the fact that maybe I learned differently or ignoring the fact that there may be other factors and just saying that your main problem is that you have a learning disability. That experience made me think of who I was as a person.

Participant #4. I worked at several predominately White schools and had the certification and licensure to do the job. At the same time, I had White colleagues who hadn’t gotten certified at the time. But I felt like a lot of times, I was there and had the credentials to prove my worth, but sometimes I felt like I had to always go that extra mile to prove my skill set. I had to go that extra mile and pander from time to time to prove that I was worth enough or acceptable to be in the circle. For example, one time I was in a situation at a middle school. I had proven that I had done my job to the best of my ability. I had shown more than enough evidence to prove that I could do the job. But after dialoging and debating over and over again, I felt like the person in charge never heard my case, never understood my experience and because of that it made me feel invisible and powerless. Those with privilege a lot time can state a case and they will get exonerated, whereas in my case I felt invisible and powerless because in my case regardless of whatever I did I always felt like I was public enemy number one.

Participant #5. One situation happened when I got busted for drugs. When I got busted I felt like the gentlemen that arrested me made fun of me and they were Caucasian males. They said, “We gotcha now, you will never see the streets again;” they said, “that’s what happens to all of y’all; y’all put yourself into a bunch!” They laughed and in so many words told me my life was over.

Participant #6. One time me and my mom went to shop on 34th Street in Manhattan. My mother was hungry so we went inside to eat. So we went inside and set at the counter. The White lady looked at us and she kept on doing what she was doing; she never one time acknowledged us. Eventually, my mom got up. I could see tears in her eyes and we just walked out.

Participant #7. My first experiences with invisibility occurred when I was a small kid, say age 7. I use to go to North Carolina. During that time I would see how proud and bold my grandfather was when he spoke with Black people, but when he spoke with White men he would “cow down” [assume on a more inferiority/invisible position] as I call it. You know he would speak soft, bow his head, not make eye contact. He was expected by them to be this way—invisible. Another example when I was in middle school I remember White boys would look at me and call me and other Black kids names. I mean, we were all different complexions, different heights, 4-inch differences, extreme differences. They would call me Kenny when I was [name removed]. I soon realized that they didn’t see me. We [all the Black boys] were the same. They looked through us and simply saw our skin color. It was amazing to me because when I saw them, I could clearly see that they were different: different hair styles, different complexions, different hair colors…. But for them they didn’t see any of that. So they really didn’t see the person that they were talking to that they respected, they just looked over us and assumed that because we were Black we must all be like the same person. It was an incredible experience.

Thematic Code 1: Self-Affirmation

All seven study participants discussed the process of routinely affirming themselves as African-American males. For them, this process is important in understanding and staying true to who they are as African-American men in a society that often perceives them as less. Self-affirmation theory refers to the process of responding to threats to an individual’s self-worth or self-image with affirming strategies to maintain positive self-image (Lannin, Guyll, Vogel, & Madon, 2013).

Cultural connectivity (1.1). For the participants, three key objectives are essential in affirming who they are as African-American males. Those objectives include (a) contact and communication with other African-American males (1.1.1), (b) understanding and exploring the historical context from which they came (1.1.2), and participating in counseling (1.1.3).

Having contact and communication with other African-American males was clearly articulated by all participants as key in self-affirmation (1.1.1). Being able to communicate and come in contact with other African-American males further affirmed their Blackness and brought about a sense of kindred spirit in a struggle for equity and equality. For the participants, this relationship was often with friends, their father, father figures, and mentors (people they respected, trusted, and often aspired to be). These relationships assisted in preventing societal standards, perceptions and beliefs that are based on White culture to cause identity confusion. Participant #1 stated, “I use other African-American male friends as sounding boards for invisibility experiences. They usually have had the same experience or something similar. They validate my experience and we are able to discuss how we handled it, how/what to think about it—how to handle it in the future.”

All seven participants referenced understanding and exploring the historical context from which they came as an important aspect in identity development and self-affirmation (1.1.2). Participant #4 stated, “I am very aware of my Blackness. I affirm it every day…by constantly reflecting on the greatness of my ancestors, on the path that we’ve trotted and reflecting on the fact that we have an African-American president.” All spoke about engaging in culturally relevant events and reading relevant books. All spoke about prominent historical and cultural African-American figures that assisted them in affirming who they are as African-American males. A few reoccurring names include Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., Marcus Garvey and President Barack Obama. Participants 4 and 5 expressed feelings that they were “standing on the shoulders of African-American men who came before them.”

Participants 1–3 referenced counseling as beneficial in affirming who they are as African-American males, while participants 4 and 6 alluded to this (1.1.3). Participant 3 stated, “…I went through his (African-American counselor at the university counseling center) [counseling] program…it led to my metamorphosis. All three participants who articulated counseling as beneficial in the self-affirmation process discussed their strong desire to see an African-American male counselor—if not male, then an African-American female counselor.

Thematic Code 2: Self-Awareness

The self-awareness theme is evident throughout all aspects of the interviews. All seven participants discussed the ongoing process of becoming self-aware as essential in self-affirming and developing a strong identity. Self-awareness occurs when an individual acknowledges biases and understands the impact that they may have on perceptions, beliefs and attitudes (Suthakaran, 2011). Participants discussed how the process of becoming more self-aware assists them in moving from being very defensive when they feel they are being treated as invisible, to becoming more conscious of invisibility treatment in order to appropriately prepare for and deal with it.

Increase consciousness about individual and societal perceptions, beliefs and attitudes (2.1). For participants, self-affirmation (2.1.1) and identity development (2.1.2) are essential to the self-awareness process. All seven participants discussed reading and understanding African-American culture, history and experiences as important to the self-affirmation (2.1.1) and self-awareness process. Participant 6 stated that “learning the truth about Black history, it just builds a confidence in you; knowing the truth helps put things in perspective.” All seven participants discussed thinking differently about and reflecting on past experiences in order to learn, grow, and negotiate invisibility experiences. Additionally, all participants discussed how that process has assisted them in changing who they are emotionally, mentally and spiritually.

Participants acknowledged the process that identity development (2.1.2) plays in achieving self-awareness. According to Franklin (1999), “identity is achieved by successfully resolving the crises inherent in life choices and making purposeful decisions and stable commitments” (p. 772). Participants described racial identity development as the impact the negotiation of racial experiences has on the individual. Participants 4 and 5 stated, “as an African-American male you have to work twice as hard [to be acknowledged and respected],” while participant 7 stated, “you always have to be better than the best [to be acknowledged and respected].” Understanding their role in society and making decision and life choices as a result informs the identity development process.

Thematic Code 3: Coping with Invisibility

According to Franklin (1999), coping with invisibility involves “being able to discern when behavior is racist, and then acting consistent with one’s sense of self” (p. 764). This personal struggle for visibility can be challenging and often overwhelming.

Building a social, spiritual and therapeutic support system that is accessible (3.1). For participants, coping with invisibility included (a) African-American male mentorship (3.1.1), (b) resiliency (3.1.2.), (c) establishing and maintaining a strong religious and spiritual foundation (3.1.3), and (d) counseling (3.1.4.).

All seven participants discussed the need to communicate overwhelming feelings of anger and frustration that result from feelings of invisibility to other Black men that they trust and value their opinions of (3.1.1). Communicating with another African-American male is central to coping with feeling of invisibility. Being understood in a world where you are often misunderstood and being able to relate to one another was powerful to all participants and assisted in coping with invisibility.

None of the participants perceived racism and invisibility as something that would soon dissipate. As a result, participants felt that being resilient was essential in coping with invisibility (3.1.2.). One participant discussed how he remained resilient by constantly reminding himself of how his ancestors overcame far worse, while also reflecting on how far this country (the United States) has come since slavery and remaining hopeful that the United States will continue to grow in the years to come. Participant 2 remained resilient by constantly reminding himself that we have a Black president, understanding his struggle as president, and using him as a model for the opportunities that lie before other Black men if they continue to work hard. Participant 2 stated, “when I am feeling low about the state of society I hold on to the fact that President Obama was able to be elected. That’s like the miracle that I hold on to.” Participant 2 stated, “Being invisible is normal for me. I expect it. I know where I’m going to be visible and where I’m not going to be visible.”

Five participants discussed having strong spiritual or religious beliefs (3.1.3). Participant 4 stated “at times I need to pray and ask God for insight on racism and how incidents I experience affect me.” Others were hopeful that the future would be brighter than the past for African-American males. Participant 4 alluded to this when he stated, “I know that things will be different when I join God in Heaven.” Participant 3 discussed abandoning Christianity for African Islamic religious beliefs. Participant 3 explained that this process has assisted him in connecting with his African culture, and participant 6 discussed his transition from Islamic faith to Catholicism to Protestantism in search of his spiritual calling.

Lastly, all participants acknowledged the process of thinking differently as fundamental in coping with invisibility. All participants acknowledged that by thinking differently African-American males can overcome pitfalls such as socially unacceptable emotions and behaviors, as well as responding defensively to feelings of invisibility. Furthermore, participants acknowledged how counseling (3.1.4) could assist in this area.

Thematic Code 4: Effectively Counseling African-American Males

The counseling theme is evident throughout all aspects of the interviews. All participants discussed counseling approaches that would be effective in working with African-American males who experience invisibility. The approaches outlined by the participants were humanistic in nature and included (a) authenticity (4.1.1), (b) unconditional positive regard (4.1.2), (c) empathetic understanding (4.1.3), and (d) self-awareness (4.1.4).

All seven participants discussed the need for counselors to be authentic (4.1.1). For participant 4, being authentic meant “avoiding politically correct statements and hiding behind real feeling and thoughts.” They discussed the need to feel like the counselor demonstrated unconditional positive regard (4.1.2). The inherent need for acceptance is ignored when African-American males are invisible. When counselors are able to demonstrate unconditional positive regard, it fosters acceptance. Participant 2 stated, “Counselors should support my experience in spite of myself…”

All seven participants discussed the need to feel visible to the counselor. Participants discussed achieving visibility by acknowledging race, culture, ethnicity and other individual and collective attributes, while also validating the experiences of the client. Participants indicated that validation is achieved by being empathetic and understanding toward the client’s experience (4.1.3). All participants discussed the need for the counselor to demonstrate empathy. Participant 7 stated, “Listening and being open to the experiences of African-American males and moving beyond book information about African-American males, but instead seeking contact with the group, is important in broadening counselor empathy and understanding.” None of the participants sought sympathy, as they all demonstrated strong feelings of pride in themselves and their culture. Instead, the need for empathy and subjective understanding of their experience was essential.

Lastly, four participants discussed the need for both the counselor and client to be self-aware (4.1.4). For these participants, the counselors’ self-awareness meant being open about their bia; exploring ways to be change agents (advocates), whether individually or collectively; and being able to openly express emotions in a way that encouraged growth. Participant 4 spoke to all the competencies presented in thematic code four by stating the following:

Therapists that [have] an Afrocentric worldview or actually went through the struggle themselves [are needed]. You can have what I call an external concept of racism, but until you actually experience it or live it there is no dialogue. So, I would need a therapist, preferably a Black male or Black female, but more or less a male, who has gone through the same struggles…of being a Black male in America. Then I think we can have an open dialogue and try to reach some resolve… [If the counselor were White] it is somewhat possible [for them to provide the same support as a Black counselor] if they have a sense of empathy, a sense of positive regard, they are very objective…they can live through my experience vicariously [congruently] so that they can be understanding…and have an Afrocentric perspective.

Implications

Clinical Practice and Client Retention

This phenomenological study explored the lived invisibility experiences of seven African-American males. The four thematic codes that were extracted from the rich data gathered during the study were used to provide potential implications for clinical practice.

Findings showed that these African-American males encounter varying experiences and levels of invisibility on a daily basis. African-American males’ strong sense of self and ability to affirm who they are as individuals and as African-Americans were core conditions of living in a world where they often feel invisible. Additional findings showed that for these participants, coping with invisibility included having a relationship with something or someone higher than themselves (religious or spiritual connection), embracing African-American history and culture, being resilient, connecting with the African-American community, and communicating with and observing other African-American men. Based on the findings, specific counseling theories and techniques as well as additional approaches were outlined as strategies for working with African-American males in clinical practice, and for retaining this population after initial visits.

Conclusions from the findings purported that counselors working with African-American males experiencing invisibility could encompass two fundamental approaches to counseling at the core of their clinical practice: multicultural and person-centered approaches. Encompassing these approaches provides the stability needed to encourage African-American males to participate in counseling, while also encouraging these clients to return to counseling. Building on these approaches, counselors should utilize additional humanistic-existential therapies, such as Adlerian and existentialism.

Specifically, the use of encouragement—fundamental in Adlerian counseling—and the promotion of social connections to foster a sense of belonging produces a stronger sense of self. Existentialism can assist in the quest for meaning and life purpose (Corey, 2001). Findings indicate that African-American males’ social connection with other African-American males is pertinent in developing self-awareness, while also learning how to strive in society. Exploring self-awareness, goals, and the process it takes to reach goals during counseling sessions with African-American males can dually assist the client and counselor to better understand the clients’ perspectives and life purpose. Additionally, assisting African-American male clients by encouraging relationships with other African-American males can assist with their quest for meaning and value.

Based on the findings, it appears that African-American males would benefit from social learning theoretical perspectives during counseling. Considering Bandura’s social learning theory (1997), specific theoretical approaches include observational learning, nurturing intrinsic and extrinsic reinforcers (e.g. pride, the environment), and motivated modeling. Again, this could be encouraged through mentoring, social connections within the African-American community (e.g. volunteerism), and exposure and knowledge about the African-American experience.

Admittedly, many of these theories fall short when considered from a multicultural perspective. However, the additional use of specific techniques, applied appropriately, can become building blocks in working with African-American males. Moreover, counselors should promote resiliency as a means of coping with invisibility. To do this, counselors should consider connecting clients with or encouraging clients to garner an African-American male mentor. African-American males’ connection with positive African-American male mentors is highly regarded by all participants in the study and key in coping with invisibility experiences. Additionally, the use of both psychoeducation and bibliotherapy groups geared toward African-American males encourages kinship, skill development, as well as cultural and historical understanding.

Furthermore, when considering the theoretical underpinnings of the study (Nigrescence, humanism and multiculturalism), three premises are put forward for counselors working with this populations: (a) collaborate with the individual as he works to make sense of himself as a social being (Cross, 1991; Cross & Vandiver, 2003); (b) understand and value the individual’s subjective experience (e.g., feelings, opinions, values; Scholl, 2008), and (c) work to become more aware of both one’s own culture (as the counselor) and the culture of the client in order to remove barriers, build rapport and overcome social stereotypes and bias.

Research

Based on the findings, future research might consider the impact that mentoring, religion and spirituality, cultural belonging, and resiliency have on African-American male racial identity development and African-American males’ ability to cope with racial experiences. Potential research questions could include the following: How effective is mentoring in helping African-American males to cope with issues related to racial identity development? How do religion and spirituality assist African-American males in coping with issues related to racial identity development? Is resiliency a learned behavior for African-American males? Investigations in these areas have the potential to yield useful findings.

Limitations of the Study

Caution should be exercised when generalizing the study’s findings to all African-American males. First, the study included only seven African-American males. While these seven participants garnered a rich amount of data to support the study, the qualitative nature of the study made generalizing this information across an entire group of people difficult. Quantitatively exploring the same research questions could provide more generalizable data. Second, the majority of the participants were educated, middle-class African-American males. A diverse group of African-American males was not considered in this study; a more diverse participant sample could enhance future research on this topic.

Conclusion

Throughout the study, participants clearly articulated that they did not think the process of feeling invisible would soon dissipate. Therefore, all participants encouraged learning how to cope with invisibility. Counselors can encourage African-American males to cope with invisibility by advocating resiliency, promoting self-awareness and identity development, affirming African-American identity both individually and collectively, fostering African-American male mentorships, teaching African-American males how to negotiate race, and encouraging historical and cultural knowledge and understanding. At the same time, African-American males cannot be taught to cope or change their cognition, behavior, or emotions without counselors advocating and working to change individual, systemic and institutional barriers that lead to feelings of invisibility.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

Corey, G. (2001). Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cross, W. E., Jr. (1991). Shades of black: Diversity in African-American identity. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Cross, W. E., Jr. (2003). Encountering nigrescence. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (2nd ed., pp. 30–44). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cross, W. E., & Vandiver, B. J. (2003). Nigrescence theory and measurement: Introducing the Cross Racial Identity Scale (CRIS). In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (2nd ed., pp. 371–393). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The souls of Black folk. New York, NY: Library of America.

Ellison, R. (1952). Invisible man. New York, NY: Random House.

Franklin, A. J. (1999). Invisibility syndrome and racial identity development in psychotherapy and counseling African American men. The Counseling Psychologist, 27, 761–793. doi:10.1177/0011000099276002

Gibson, M. A., & Ogbu, J. U. (1991). Minority status and schooling: A comparative study of immigrant and involuntary minorities. New York, NY: Garland.

Giorgi, A. (1985). Sketch of a psychological phenomenological method. In A. Giorgi (Ed.), Phenomenology and psychological research (pp. 8–22). Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Hays, D. G., & Wood, C. (2011). Infusing qualitative traditions in counseling research designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(3), 288–295. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00091.x

Hunt, B. (2011). Publishing qualitative research in counseling journals. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(3), 296–300. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00092.x

Lannin, D. G., Guyll, M., Vogel, D. L., & Madon, S. (2013). Reducing the stigma associated with seeking psychotherapy through self-affirmation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 508–519. doi:10.1037/a0033789

Levers, L. L., Anderson, R. I., Boone, A. M., Cebula, J. V., Edger, K., Kuhn, L., . . . Sindlinger, J. (2008, March). Qualitative research in counseling. Applying robust methods and illuminating human context. Program presented at the annual conference of the American Counseling Association, Honolulu, HI. Retrieved from http://counselingoutfitters.com/vistas/vistas08/Levers.htm

Oyserman, D., Gant, L., & Ager, J. (1995). A socially contextualized model of African American identity: Possible selves and school persistence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(6), 1216–1232. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.6.1216

Parham, T. A. (1999). Invisibility syndrome in African descent people: Understanding the cultural manifestations of the struggle for self-affirmation. The Counseling Psychologist, 27, 794–801. doi:10.1177/0011000099276003

Scholl, M. B. (2008). Preparing manuscripts with central and salient humanistic content. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 47, 3–8. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2008.tb00043.x

Sue, D. W., Ivey, A. E., & Pedersen, P. B. (1996). A theory of multicultural counseling & therapy. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Suthakaran, V. (2011). Using analogies to enhance self-awareness and cultural empathy: Implications for supervision. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 39, 206–217.

Wang, Y.-W. (2008). Qualitative research. In P. P. Heppner, D. M. Kivlighan, & B. E. Wampold. (Eds.), Research design in counseling (3rd ed., pp. 256–295). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Wertz, F. J. (2005). Phenomenological research methods for counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 167–177. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.167

Angel Riddick Dowden, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at North Carolina A&T State University. Jessica Decuir Gunby is an Associate Professor at North Carolina State University. Jeffrey M. Warren, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Quintin Boston is an Assistant Professor at North Carolina A&T State University. Correspondence can be addressed to Angel Riddick Dowden, North Carolina A&T State University, 1601 E. Market Street, Proctor Hall-325, Greensboro, NC 27411, adowden@hotmail.com.