Ashley Ascherl Pechek, Kristin A. Vincenzes, Kellie Forziat-Pytel, Stephen Nowakowski, Leandrea Romero-Lucero

In counselor education programs, students acquire clinical experience through both practicum and internship; this time frequently marks students’ first counseling experiences working with suicide in a clinical context. Often, students in practicum or internship working with clients who may be experiencing suicidal ideations do not feel properly equipped to deal with suicide. This study aimed to develop a practice model for online counselor education programs that increases counseling students’ self-efficacy to work with clients who may present with suicidal ideations. Sixty online graduate-level clinical mental health counseling students completed a pre- and posttest self-efficacy assessment. Findings showed that students’ self-efficacy increased due to taking the online basic counseling skills class that included teaching activities related to suicide screening, assessment, and intervention.

Keywords: self-efficacy, suicide, assessment and intervention, online counselor education, practice model

Despite a growing body of research and evidence-based interventions, suicide remains the 11th leading cause of death in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021). A 2014 World Health Organization report (WHO; 2014) estimated that more lives were lost to suicide than to war, conflict, and natural disasters combined. More recently, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP; 2023) estimated that in 2021 there were 1.7 million suicide attempts; more than 48,000 Americans died by suicide. In 2023, trends showed about 130 suicides per day (AFSP, 2023).

To address the ongoing concern of suicide risk, counselor education programs are expected to prepare students for work with diverse clients who experience suicidal ideations (Wachter Morris & Barrio Minton, 2012). Specifically, the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2023) requires counseling programs to provide counselors-in-training (CITs) with skills in crisis intervention, suicide prevention, and response models and strategies, as well as proper assessment and management of suicidal ideations. There are no consistent suicide prevention or intervention training standards or models among counselor education programs. Organizations such as the American Association of Suicidology have recommended that suicide knowledge and assessment be at the forefront of health care by having (a) graduate programs require suicide knowledge and skills acquisition in their curriculum, (b) state licensure boards require suicide-specific education for renewal of licenses, (c) government-funded health care systems and hospitals require staff training in suicide assessment and management, and (d) staff appropriately trained to assess, manage, or treat patients who experience suicidal thoughts (Schmitz et al., 2012).

The current study aimed to determine if a practice model used in an online basic counseling skills course was effective at increasing counseling students’ self-efficacy when working with clients who present with suicidal ideations. Results from the study were used to determine if the skills-based online course effectively taught suicide assessment and intervention skills to graduate students. Discussion and implications regarding the need to establish best practices in prevention and intervention training for CITs are included. Additional considerations are given for both online and brick-and-mortar counseling programs.

Competencies and Principles

To assist counselor educators with how to best address the ongoing concern of suicide risk in clients, the Suicide Prevention Resource Center (2006) identified several core competencies and skills needed to assess and manage individuals at risk for suicide. These competencies can be used as a framework for extensive suicide training (Granello, 2010). Other models, such as a core competency–based training workshop in suicide screening, assessment, and management, have been developed to assess the effectiveness of suicide training, including pre- and post-workshop self-assessments, evidence-based instruction, role-playing, expert demonstration, group discussions, and video-recorded risk assessments of trainees intended to provide feedback (Cramer et al., 2017). Together, these competencies and principles can be used to develop a practice model in graduate counselor education programs and to better assist CITs in preparing to work with a client experiencing suicidal thoughts.

Despite the Suicide Prevention Resource Center (2006) identifying core competencies and skills needed to properly assess and manage individuals for risk of suicide, the research from counseling graduate programs on the implementation of suicide training remains sparse (Wasylko & Stickley, 2007). Therefore, we looked at other graduate programs of similar disciplines (e.g., social work, school psychology, and school counseling) to gain a better idea of best practices in related fields. Unfortunately, literature related to best practices within graduate programs of similar disciplines also demonstrates a lack of training in suicide risk assessment and intervention (Becnel et al., 2021; LeCloux, 2021; Liebling-Boccio & Jennings, 2013). This expanded look into other mental health professions further supports the notion that limited research exists regarding training in suicide screening, assessment, and intervention at the graduate level; thus, more attention is needed in these areas.

Suicide Training in Graduate Programs

Graduates of other counseling programs have indicated that there were limitations in the suicide prevention training that they received (Wakai et al., 2020). In a national sample of American School Counselor Association members, Becnel et al. (2021) found that 38% of school counselors (N = 226) did not receive suicide prevention training during their graduate programs and 37% received no training in crisis intervention. Similar results were found in a study of 193 professional counselors; over a third reported no classroom training in crisis preparation, and 30% reported no or minimal preparation in suicide assessment (Wachter Morris & Barrio Minton, 2012).

Schmidt (2016) evaluated the confidence and preparedness of 339 mental health practitioners (i.e., professional counselors, school counselors, social workers, psychologists). Results indicated that 52% of participants had graduate course work in suicide intervention and assessment, but 19% reported feeling not very confident in working with clients who had suicidal ideations. Conversely, Binkley and Leibert (2015) found that students who received training before their practicum working with clients who experience suicidal thoughts had lower anxiety and a greater level of confidence in addressing those issues compared to those who did not receive training.

The results of these studies look at counselor training and confidence or preparedness, to support the need for additional training in this area and research on best practices in preparing CITs to work with clients who present with suicidal ideation. Studies report training levels associated with practice outcomes (e.g., confidence), but there is a lack of literature explaining how suicide assessment and intervention training occurs in counselor education programs. Although there is literature that demonstrates that self-efficacy directly influences a counselor’s development (Barbee et al., 2003; Barnes, 2004; Kozina et al., 2010; Lent et al., 2003; Pechek, 2018; Vincenzes et al., 2023), literature that specifically addresses self-efficacy as it relates to working with a client who experiences suicidal ideation is sparse. However, the literature supports that additional training is needed on this topic and that self-efficacy is an important concept to consider when developing training protocols for CITs.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is dynamic and plays a significant role in counselor training and skill development. Bandura (1986) first introduced self-efficacy as an individual’s judgment on their capabilities to execute an action to achieve a certain performance or goal. Later the term was linked to behavioral motivation in the academic setting and was defined as a student’s belief in their ability to accomplish and succeed on an academic-related task (Bandura, 1989). Bandura (1997) also found that self-efficacy beliefs can be altered through four primary sources: (a) personal performance accomplishments, (b) vicarious learning, (c) social persuasion, and (d) physiological and affective states. While self-efficacy is dynamic (Lent, 2020) and can be impacted by personal interpretation of these primary sources (Lent & Brown, 2006), research has found that self-efficacy is an important factor in counselor competency (Barbee et al., 2003; Barnes, 2004; Kozina et al., 2010; Pechek, 2018; Vincenzes et al., 2023). More specifically, Lent et al. (2003) found that CITs’ initial clinical work and experience with more difficult skills (e.g., managing a session, handling the role of the counselor) increased counselor self-efficacy (Kozina et al., 2010).

Self-Efficacy in Suicide Training

Counselors who lack self-efficacy in their ability to work with a client who is experiencing suicidal thoughts may conduct suicide screening, assessments, and interventions ineffectively (Douglas & Wachter Morris, 2015; Jahn et al., 2016). In addition, counselors with low self-efficacy are more likely to subconsciously choose not to see suicide warning signs (Douglas & Wachter Morris, 2015) or avoid the topic of suicide altogether (Jahn et al., 2016). It is important that CITs are exposed to the topic of suicide and that they gain more counseling experience involving this issue during their training so that they will feel more confident working with a client experiencing suicidal thoughts. More exposure to this topic leaves CITs feeling better equipped to address suicide in sessions and is also likely to increase their self-efficacy (Elliott & Henninger, 2020; Pechek, 2018; Sawyer et al., 2013; Shea & Barney, 2015).

Clear evidence of the positive effects of including training on suicide within counselor education programs has been documented, demonstrating a reduction of fear and more success in helping clients manage suicide-related issues (Jahn et al., 2016). CITs who had prior training in suicide experienced lower levels of anxiety and higher levels of confidence in working with a client with suicidal thoughts (Binkley & Leibert, 2015). Similarly, professional counselors who expressed confidence in their academic training on suicide experienced lower levels of fear related to negative client outcomes and had higher levels of confidence in their skills and abilities (Jahn et al., 2016).

Self-Efficacy in Suicide Training for Online Learning. Although the topic of self-efficacy in counselor education has been studied (Barbee et al., 2003; Barnes, 2004; Conteh et al., 2018; Fakhro et al., 2023; Kozina et al., 2010; Pechek, 2018; Suh et al., 2018; Vincenzes et al., 2023), the literature does not focus on how best to teach for improved self-efficacy related to suicide assessment and intervention in the online setting. Specifically, it is not clear how counselor educators can best teach suicide screening, assessment, or intervention skills online. Two recent studies in counselor education programs have tried to better explain self-efficacy in suicide training during online learning (Elliott & Henninger, 2020; Gallo et al., 2019).

Elliott and Henninger (2020) showed that different online teaching strategies (e.g., a combination of a written module, role-plays/observations, and a facilitated discussion) in an online counselor education program showed no between-group differences, while all teaching strategies showed significant improvements in self-efficacy of CITs. Another study found that a 15-hour youth suicide prevention course that included didactic and experiential activities in a master’s counseling program increased participants’ knowledge and perceived ability to help clients who experienced suicidal ideations, as well as increased their self-efficacy in screening, assessment, and intervention (Gallo et al., 2019).

Purpose of the Study

With the influx of online counselor education programs, it is essential to determine how to improve suicide training and intervention skills (Allen & Seaman, 2014) so that CITs are better prepared to address the topic of suicide. The current quantitative study examined the influence of an online counseling practice model on CITs’ self-efficacy when it came to the utilization of suicide assessment and intervention with clients. The research question was: Do CITs’ perceived levels of self-efficacy in suicide assessment and intervention change because of practicing these skills through role-plays in an online counseling course? By better understanding these findings, implications can be made for how counselor educators can teach suicide screening, assessment, and intervention skills online.

Method

Procedures

Prior to beginning this study, our research team received full approval from the IRB. Participants were then recruited from an online clinical mental health counseling program. Only students enrolled in the online basic counseling skills course were recruited to ensure that all participants were at the same place in the program regarding knowledge and skills learned. An electronic announcement was posted in the 10 online basic skill course shells. The announcement included a hyperlink directing participants to an informed consent document, which detailed their requirements and rights and allowed them to indicate their consent to participate. Before completing any survey questions, the participants created a username for data comparison in the pre- and posttests, which was also an avenue for dropping participants if they requested to leave the study. After providing their username, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire and the Counselor Suicide Assessment Efficacy Survey (CSAES; Douglas & Wachter Morris, 2015). To protect participant anonymity, no additional identifying information was collected.

Structure of the Basic Skills Class

Once students completed the pretest consent form, demographic questionnaire, and assessment, the counselor educators (i.e., faculty) started the class by providing participants with a variety of technology-assisted counseling experiences and activities (e.g., role-play demonstrations, best practices in telemental health counseling, lecture videos on specific counseling skills, guidelines for a preferred topic for the role-plays). To ensure consistency of content across courses, the faculty made sure to include the same teaching resources in each section of the class and continuously consulted each other to make sure that the classes were taught as similarly as possible. In addition, they decided that all students should receive the same training and teaching activities, ensuring that they were equally prepared to address the topic of suicide during their clinical courses and after graduation.

The topic of self-care was addressed with participants, as this was the first opportunity students had to practice counseling skills within the program. This focus on self-care was an important step toward decreasing the potential of significant deep-rooted issues surfacing without sufficient time or training to properly address them. Students would learn about a new basic counseling skill each week and were instructed to incorporate that skill into the week’s role-play. In addition to reading about the skill in the course textbook, students were required to view weekly lecture videos and role-plays that specifically explained and demonstrated the skill that the students would be practicing that week during their role-play. For role-plays, participants were randomly paired with other participants within the same basic counseling skills course to practice basic foundational counseling skills. Each pair of students participated in five weekly role-plays as both the counselor and the client. Two of these role-plays occurred during class and three occurred outside of class. Each role-play occurred via Zoom and lasted approximately 10–15 minutes during class or 30 minutes when completed outside of class. For in-class role-plays, participants utilized breakout rooms in Zoom. Faculty provided each participant in the counselor role with feedback at the end of each role-play. Role-plays outside of the class required participants to send their partner a Zoom link and password. The role-plays were recorded in Zoom. Participants identified one role-play to submit to the instructor for formal assessment of their basic counseling skills and to provide formative feedback to each participant when acting in the counselor role.

Preparation for Suicidal Ideation Role-Plays

After the initial five role-plays were completed, participants prepared for role-plays that focused on crisis counseling. They read a chapter from their textbook on crisis counseling and various supplemental articles on working with a client with suicidal ideations. In addition, they viewed pre-recorded role-plays on suicide assessment created by faculty in the program. Participants remained in the same randomly assigned pairs from earlier in the semester and then completed an additional five role-plays (one weekly), which allowed for them to gain experience working with a client with suicidal ideations.

Suicidal Ideation Role-Plays

Prior to beginning the role-plays, participants were provided with a brief synopsis for the topic of suicide and were also given the instructor’s phone number in case they needed immediate support or guidance. Like the previous role-plays, each of these lasted approximately 10–15 minutes during online classes or 30 minutes outside of class. Again, role-plays completed outside of class were recorded so that faculty could provide detailed feedback to students. The first in-class role-play was completed in a fishbowl format, allowing students in the class to observe. Instead of utilizing multiple breakout rooms, students remained in one room and observed one role-play at a time. This allowed students to learn vicariously from one another and to observe the ways that suicide screening, assessment, and intervention skills were demonstrated. The initial role-play also served as a way for participants in the counselor role to gain experience completing a suicide assessment while practicing other basic counseling skills. Four additional role-plays occurred and offered an opportunity for participants to continually reassess the risk of suicide of their partners, develop a safety plan, establish treatment goals, and practice other basic counseling skills. During the last role-play, participants in the counselor role conducted a termination session in which the counselor reviewed the client’s safety and treatment plans. Additionally, they reviewed the client’s goals and objectives and provided time for the client to reflect on the counseling experience.

Faculty Supervision and Learning Activities

During the semester, faculty supervision was an essential component of the process. If additional support or guidance was needed for participants, faculty were available via phone between 8 am–8 pm, Monday through Friday. Faculty were available to all role-play participants regardless of their role (i.e., counselor, client, or observer). While supervision can look different for each instructor, the counselor educators in this study regularly consulted with one another to ensure that they were conveying the same expectations to the students enrolled in the courses. This extended to making sure they discussed similar topics at the same time during the course; included the same teaching activities, readings, and assignments; and consulted with one another when a concern arose that may have changed course plans.

In addition to completing the virtual role-plays during the semester, participants completed a variety of activities and assignments that were intended to prepare them for realistic experiences needed upon graduation. For example, participants completed components of a treatment plan after each counseling session which were submitted to the instructor immediately following the role-play. Additionally, they submitted video tapes of role-plays for faculty feedback. Finally, participants transcribed one 30-minute role-play. This assignment allowed them to identify and reflect on specific foundational skills that they used when working with a client reporting suicidal ideations. At the conclusion of the semester, participants were asked to complete the posttest using the same username they created at the beginning of the semester. The posttest included the same assessment as the pretest (CSAES).

Participants

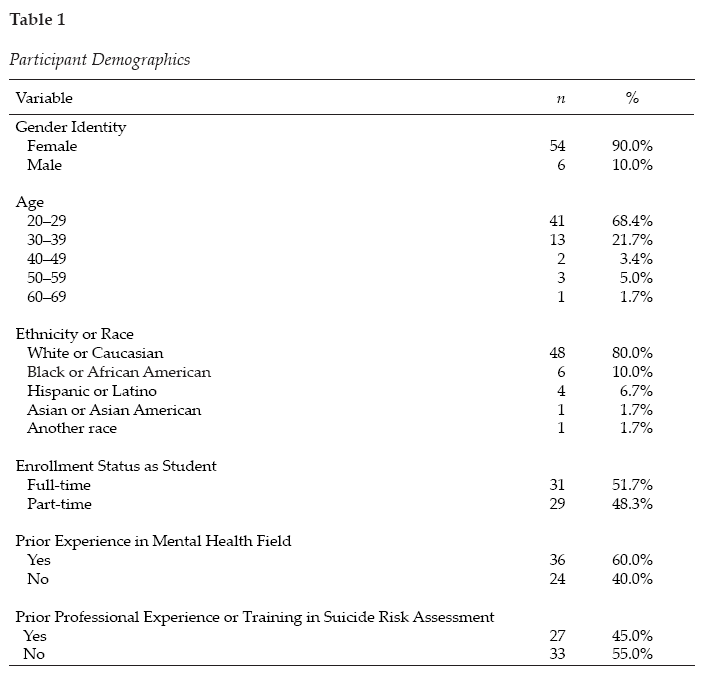

A convenience sample was used for this study. Master’s-level counseling students enrolled in the spring 2021 and spring 2022 counseling skills courses (10 sections total) in an online clinical mental health counseling graduate program were recruited via news announcements and emails to participate in this study. A total of 120 students were invited to participate in the study; however, only 60 were included because they completed both the pretest and posttest self-efficacy assessment. Included students’ ages ranged from 21–61 years old. The average age of participants was 29.03 (SD = 8.49). The sample consisted of the following racial identities: 80.0% White or Caucasian (n = 48), 10.0% Black or African American (n = 6), 6.7% Hispanic or Latino (n = 4), 1.7% Asian or Asian American (n = 1), and 1.7% did not indicate their racial identities (n = 1). Most participants identified as female (90%, n = 54) and were enrolled in the mental health counseling program full-time (51.7%, n = 31). When asked about prior experience in the mental health field, 60% (n = 36) had this experience; however, only 45% (n = 27) had prior professional experience or training in suicide risk assessment. Table 1 contains all participant demographics.

Measure

The study participants completed the CSAES (Douglas & Wachter Morris, 2015). The CSAES measures self-efficacy in suicide assessment and intervention. According to the developers (Douglas & Wachter Morris, 2015), the CSAES is comprised of 25 items that may make suicide assessment or intervention difficult for a counselor. These items are rated on a confidence scale that ranges from 1 (not confident) to 5 (highly confident). The confidence items are organized into four subscales:

- General Suicide Assessment, which has seven items and a maximum score of 35

- Assessment of Personal Characteristics, which has 10 items and a maximum score of 50

- Assessment of Suicide History, which has three items and a maximum score of 15

- Suicide Intervention, which has five items and a maximum score of 25

Sample items include the following: Q1 “I can effectively inquire if a student has had thoughts of killing oneself” (General Suicide Assessment); Q11 “I can effectively ask a student about his or her history of mental illness” (Assessment of Personal Characteristics); Q18 “I can effectively ask a student about his or her previous suicide attempts” (Assessment of Suicide History); and Q25 “I can appropriately intervene if a student is at imminent risk for suicide” (Suicide Intervention).

Table 1

Participant Demographics

The total score for the scale is 125, with higher scores representing higher levels of self-efficacy associated with suicide assessment and intervention (Douglas & Wachter Morris, 2015). The CSAES can be scored two ways. First, the assessment can be scored individually for a more detailed understanding of what differences, if any, in self-efficacy exist between differing aspects of suicide assessment. The second way is to calculate the total sum of the assessment-related subscales and the intervention subscale. In doing so, each subscale would have a mean for the individual scale (Douglas & Wachter Morris, 2015).

The assessment developers have reported internal reliability for the CSAES as a calculation for each of the four subscales and the second-order factor of Suicide Assessment using Cronbach’s α: General Suicide Assessment α = .882, Assessment of Personal Characteristics α = .88, Assessment of Suicide History α = .81, Suicide Intervention α = .83, and Suicide Assessment α = .93 (Douglas & Wachter Morris, 2015).

The CSAES was noted for showing “structural aspects of validity and sensitivity to detect differing levels of self-efficacy” (Douglas & Wachter Morris, 2015) based on the utilization of a four-factor model that was cross-validated. The scale was validated with a total of 324 participants. Of the participants, 258 (79.63%) were female. Unfortunately, a limitation of the instrument is that the diversity of participants was unknown due to ethnicity inadvertently being left off the demographic questionnaire while it was being developed (Douglas & Wachter Morris, 2015).

The current study assessed the internal reliability of the CSAES using Cronbach’s α and omega (ω) using test-retest reliability because the measure of consistency was between two measurements of the same construct to the same group at two different times. The overall CSAES has strong reliability (α = .978; ω = .978), and each subscale had the following reliability scores: General Suicide Assessment (α = .943; ω = .946); Assessment of Personal Characteristics (α = .947; ω = .947); Assessment of Suicide History (α = .896; ω = .890); and Suicide Intervention (α = .920; ω = .915). All subscale reliability coefficients were high when looking at both α and ω, meaning that good internal consistency was found among items of the scale (Green & Salkind, 2014).

Data Analysis

Before running any analyses, we screened the data using SPSS version 26.0.0.1 software to check for (a) missing data, (b) average expected scores per the outcome variables, (c) standard deviations within range, and (d) normality of data (Green & Salkind, 2014). The initial sample included 108 surveys; however, only 60 of these could be paired with posttest data, using the username data point. Therefore, individuals with their missing pair were deleted along with any others that included missing data (i.e., listwise deletion). The final sample included 60 respondents. A power analysis using a statistical power analysis program (G*Power 3.1) for paired t-test showed an N of 54 was needed for 95% power with an alpha level of .05 and a moderate effect size of .5. Next, scales were computed, and univariate testing occurred. Data met all assumptions for conducting a paired t-test (i.e., dependent variable was continuous, normally distributed, and without outliers and the observations were independent of one another). The paired t-test was used to test the effectiveness of training for suicide assessment and intervention in a basic skills class using a single-group (pretest/posttest) design, including demographics and the CSAES. To ensure that all students received the same teaching activities and assignments, we decided not to utilize a control group. We wanted to ensure that all students were equally prepared and trained to address the topic of suicide upon entering their clinical courses and upon graduation.

Results

The purpose of the study was to compare counseling students’ pretest and posttest self-efficacy assessments when taking a basic skills course that highly emphasized skills related to suicide training and assessment. The results of a paired-samples t-test on the General Suicide Assessment subscale indicate that on average, students scored significantly higher (Mpost = 28.57, SD = 4.80) after taking the basic skills class (Mpre = 21.20, SD = 7.80), t(59) = −9.15, p < .001. A large effect was found (d = 1.182, 95% CI [−1.51, −.85]). The results of a paired-samples t-test on the Assessment of Personal Characteristics subscale indicate that on average, students scored significantly higher (Mpost = 41.17, SD = 6.59) after taking the basic skills class (Mpre = 33.80, SD = 8.75), t(59) = −8.77, p < .001. A large effect was found (d = 1.133, 95% CI [−1.46, −.81]). The results of a paired-samples t-test on the Suicide History Assessment subscale indicate that on average, students scored significantly higher (Mpost = 13.07, SD = 2.22) after taking the basic skills class (Mpre = 9.95, SD = 3.33), t(59) = −8.38, p < .001. A large effect was found (d = 1.081, 95% CI [−1.40, −.76]). The results of a paired-samples t-test on the Suicide Intervention subscale indicate that on average, students scored significantly higher (Mpost = 19.00, SD = 4.32) after taking the basic skills class (Mpre = 14.63, SD = 5.46), t(59) = −7.21, p < .001. A large effect was found (d = .931, 95% CI [−1.23, −.63]). In summary, students’ level of self-efficacy related to suicide assessment and intervention increased in all areas as a result of taking the basic counseling skills class.

Because this study had a small sample size, the risk increases that at least one test is statistically significant just by chance. Therefore, a Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust the significance levels: Bonferroni correction = .05/4 = .0125 (.05 = acceptable significance level; 4 = number of subscales of CSAES). Therefore, the familywise error value is .0125. Because the above results are looking at significance at the p <.001 value, all results remain significant.

Discussion

The initial research question was: Do CITs’ perceived levels of self-efficacy in suicide assessment and intervention change because of practicing these skills through role-plays in an online counseling course? According to the results of the current study, on average, students felt significantly more prepared and confident in their ability to counsel someone experiencing suicidal ideations after practicing the skills in their basic counseling skills online course. Prior research indicated that many students were either not taught these skills (Becnel et al., 2021) or did not feel prepared to address these issues in counseling (Schmidt, 2016). The current study points to the vitality of both teaching students about suicide screening and assessment, as well as providing them with a safe space to practice the skills. By offering students opportunities to practice suicide screening, assessment, and intervention skills, instructors could help reduce their students’ anxiety in addressing the topic during their clinical courses, which Binkley and Leibert (2015) found to be a significant student concern.

Furthermore, it is important for counselor educators to observe and provide students with feedback regarding these essential skills. Past research points to the concern that students are not adequately conducting suicide screening, assessments, and interventions (Jahn et al., 2016); therefore, it would behoove counselor educators to infuse various opportunities throughout the curriculum to strengthen these skills. In turn, feedback and practice opportunities combined may help to enhance students’ levels of self-efficacy (Elliott & Henninger, 2020; Gallo et al., 2019), thus helping them to address the issues with clients in a timely and direct manner.

Implications for Training

While CACREP (2023) requires counselor educators to prepare students to work with clients who present with suicidal ideations, there is no clear criteria as to the best way of preparing students to work with these clients. Research on the topic is limited; however, the results of this study can provide a framework for helping to inform key training areas in counselor education and future research.

As counselor educators continue to expand on the didactic knowledge of suicide screening, assessment, and intervention, more intentional efforts need to be embedded throughout the curriculum to continuously expose students to experiential opportunities for practicing these skills. This idea coincides with the recommendation from the American Association of Suicidology that proposes suicide knowledge and assessment be at the forefront of graduate program curricula (Schmitz et al., 2012). First, in foundational courses, students could become more comfortable with the topic of suicide. These courses could help break down barriers and possibly calm nerves that tend to surround the topic of suicide. In assessment courses, students could role-play giving a partner various suicide screenings and assessments and gain experience interpreting the results. These role-plays could occur during class or be recorded for faculty feedback. In skills courses, students could practice suicide intervention by broaching the topic with their classmate-clients to help them feel more comfortable with directly asking clients if they are experiencing suicidal ideations. In addition, it may be helpful if a trauma and crisis counseling course was required within the core curriculum. This course could have content devoted to suicide screening, assessment, and intervention, including both didactic and experiential opportunities. By offering these opportunities throughout the curriculum, similar to ethical and cultural considerations, students may feel more comfortable and confident as they enter their clinicals (Binkley & Leibert, 2015; Guillot Miller et al., 2013). This intentional, consistent exposure to practicing these skills could help more students gain foundational knowledge and experience with this topic. In turn, as their self-efficacy and comfort levels increase, they may be more confident addressing this topic with clients. Ultimately, this may increase client welfare by ensuring effective assessment and treatment of client needs.

Implications for Counselor Education Training Research

The topic of suicide screening, assessment, and intervention in counselor education and supervision could benefit significantly from continued outcome-based research. For example, longitudinal studies could track students’ perceived levels of self-efficacy on suicide screening, assessment, and intervention as they go through a counseling program. This may help educators become more intentional about when and how the topic is infused within the curriculum. In addition, research could compare different types of teaching methods (e.g., role-play versus lecture) that expose students to the topic and assess which methods are more influential in building students’ skills and self-efficacy. Finally, researchers could interview current mental health therapists to identify knowledge and skill gaps to help educators teach students about crisis counseling more intentionally.

Limitations

There are a few limitations to the current study that are important to discuss. First is the variability in teaching and supervision styles across different instructors, which may impact the students’ overall feelings of self-efficacy. Although the same procedures were followed, educators inevitably have different styles of giving feedback. How the feedback is perceived by the student may impact their confidence in using the acquired skills.

Another limitation involves the notion of social desirability bias. The participants in the current study were students in the program; therefore, they may have felt pressured to identify increases in their self-efficacy around suicide assessment and intervention. This pressure may have been experienced because some of their current professors also served as researchers in the study and the students may have wanted to gain favor with them.

With regard to external validity, there are a few limitations. First, our research team did not account for prior experience in suicide screening, assessment, or intervention; thus, the results could have been impacted by external experiences versus the sole experience of the course activities. Additionally, there was a large portion of the data that could not be used because the pre- and post- surveys could not be aligned. Although the current study had 60 viable pre- and post- surveys, the data could have been more reliable and generalizable with a larger dataset. Furthermore, there was a lack of diversity in the research sample. Because the participants were primarily White females, the results may be limited in its generalizability to other cultures and genders.

Future studies should attempt to better isolate these variables (i.e., teaching styles, feedback, participant recruitment, prior experience in suicide training, cultural background) and find ways to improve response rates. In addition, it would be beneficial to have a comparison course or data from other counseling programs’ basic skills classes to further determine if this practice-based model was effective. Results could be linked to more general self-efficacy increases because of growing more comfortable with learning and using interviewing skills (Holladay & Quiñones, 2003).

One final limitation worth noting is the effect size estimates of the pre- and posttest scores. All effect sizes are large. Some reasons why the effect sizes may be large in the paired-samples t-tests include: (a) large differences between paired observations (the mean scores between the pre- and posttest scores were extremely different), and (b) small within-group variability (if the within-group variability is small, then even small differences between the paired observations could result in a large effect size).

Conclusion

As counselor educators prepare students for the profession, intentional inclusion of suicide screening, assessment, and intervention skills is vital to increasing students’ confidence and preparation to address this topic with their future clients. But it is not enough for students to learn about screening, assessment, and interventions; they need experiential opportunities to practice and develop these skills. In turn, feedback and practice will increase their comfort levels to directly and adequately support their clients’ needs.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2014). Grade change: Tracking online education in the United States. The Sloan Consortium. Sloan-C. http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradechange.pdf

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. (2023). Suicide statistics. https://afsp.org/suicide-statistics

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

Barbee, P. W., Scherer, D., & Combs, D. C. (2003). Prepracticum service-learning: Examining the relationship with counselor self-efficacy and anxiety. Counselor Education and Supervision, 43(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01835.x

Barnes, K. L. (2004). Applying self-efficacy theory to counselor training and supervision: A comparison of two approaches. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44(1), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2004.tb01860.x

Becnel, A. T., Range, L., & Remley, T. P., Jr. (2021). School counselors’ exposure to student suicide, suicide assessment self-efficacy, and workplace anxiety: Implications for training, practice, and research. The Professional Counselor, 11(3), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.15241/atb.11.3.327

Binkley, E. E., & Leibert, T. W. (2015). Prepracticum counseling students’ perceived preparedness for suicide response. Counselor Education and Supervision, 54(2), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12007

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, February 20). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS) fatal injury reports. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/fatal-leading

Conteh, J. A., Mariska, M. A., & Huber, M. J. (2018). An examination and validation of personal counseling and its impact on self-efficacy for counselors-in-training. Journal of Counselor Practice, 9(2), 109–138.

https://www.journalofcounselorpractice.com/uploads/6/8/9/4/68949193/jac902111_jcp_vol_9_issue_2.pdf

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2023). 2024 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/2024-Standards-Combined-Version-6.27.23.pdf

Cramer, R. J., Bryson, C. N., Eichorst, M. K., Keyes, L. N., & Ridge, B. E. (2017). Conceptualization and pilot testing of a core competency-based training workshop in suicide risk assessment and management: Notes from the field. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 233–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22329

Douglas, K. A., & Wachter Morris, C. A. (2015). Assessing counselors’ self-efficacy in suicide assessment and intervention. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 6(1), 58–69.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2150137814567471

Elliott, G. M., & Henninger, J. (2020). Online teaching and self-efficacy to work with suicidal clients. Counselor Education and Supervision, 59(4), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12189

Fakhro, D., Rujimora, J., Zeligman, M., & Mendoza, S. (2023). Counselor self-efficacy, multicultural competency, and perceived wellness among counselors in training during COVID-19: A pre- and peri-analysis. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 10(2), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2023.2229323

Gallo, L. L., Doumas, D. M., Moro, R., Midgett, A., & Porchia, S. (2019). Evaluation of a youth suicide prevention course: Increasing counseling students’ knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 12(3), 1–23. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol12/iss3/9

Granello, D. H. (2010). The process of suicide risk assessment: Twelve core principles. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88(3), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00034.x

Green, S. B., & Salkind, N. J. (2014). Using SPSS for Windows and Macintosh: Analyzing and understanding data (7th ed.). Pearson.

Guillot Miller, L., McGlothlin, J. M., & West, J. D. (2013). Taking the fear out of suicide assessment and intervention: A pedagogical and humanistic practice. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 52(1), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2013.00036.x

Holladay, C. L., & Quiñones, M. A. (2003). Practice variability and transfer of training: The role of self-efficacy generality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(6), 1094–1103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1094

Jahn, D. R., Quinnett, P., & Ries, R. (2016). The influence of training and experience on mental health practitioners’ comfort working with suicidal individuals. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 47(2), 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000070

Kozina, K., Grabovari, N., De Stefano, J., & Drapeau, M. (2010). Measuring changes in counselor self-efficacy: Further validation and implications for training and supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 29(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2010.517483

LeCloux, M. (2021). Efficient, yet effective: Improvements in suicide-related knowledge, confidence, and preparedness after the deployment of a brief online module on suicide in a required MSW course. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 41(4), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2021.1954577

Lent, R. W. (2020). Career development and counseling: A social cognitive framework. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (3rd ed., pp. 129–164). Wiley.

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2006). Integrating person and situation perspectives on work satisfaction: A social-cognitive view. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(2), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.02.006

Lent, R. W., Hill, C. E., & Hoffman, M. A. (2003). Development and validation of the Counselor Activity Self-Efficacy Scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(1), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.1.97

Liebling-Boccio, D. E., & Jennings, H. R. (2013). The current status of graduate training in suicide risk assessment. Psychology in the Schools, 50(1), 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21661

Pechek, A. A. (2018). Counselor education learning modalities: Do they predict counseling self-efficacy in students? (Publication No. 10785997) [Doctoral dissertation, Adams State University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Sawyer, C., Peters, M. L., & Willis, J. (2013). Self-efficacy of beginning counselors to counsel clients in crisis. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 5(2), 30–43. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol5/iss2/3/

Schmidt, R. C. (2016). Mental health practitioners’ perceived levels of preparedness, levels of confidence and methods used in the assessment of youth suicide risk. The Professional Counselor, 6(1), 76–88.

https://doi.org/10.15241/rs.6.1.76

Schmitz, W. M., Jr., Allen, M. H., Feldman, B. N., Gutin, N. J., Jahn, D. R., Kleespies, P. M., Quinnett, P., & Simpson, S. (2012). Preventing suicide through improved training in suicide risk assessment and care: An American Association of Suicidology Task Force report addressing serious gaps in U.S. mental health training. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(3), 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00090.x

Shea, S. C., & Barney, C. (2015). Teaching clinical interviewing skills using role-playing: Conveying empathy to performing a suicide assessment: A primer for individual role-playing and scripted group role-playing. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 38(1), 147–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2014.10.001

Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2006). Core competencies in the assessment and management of suicide risk.

Suh, S., Crawford, C. V., Hansing, K. K., Fox, S., Cho, M., Chang, E., Lee, S., & Lee, S. M. (2018). A cross-cultural study of the self-confidence of counselors-in-training. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 40(3), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-018-9324-4

Vincenzes, K., Pechek, A., & Sprong, M. (2023). Counselor trainees’ development of self-efficacy in an online skills course. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 17(1). https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol17/iss1/1

Wachter Morris, C. A., & Barrio Minton, C. A. (2012). Crisis in the curriculum? New counselors’ crisis preparation, experiences, and self-efficacy. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51(4), 256–269.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00019.x

Wakai, S., Schilling, E. A., Aseltine, R. H., Blair, E. W., Bourbeau, J., Duarte, A., Durst, L. S., Graham, P., Hubbard, N., Hughey, K., Weidner, D., & Welsh, A. (2020). Suicide prevention skills, confidence, and training: Results from the Zero Suicide Workforce Survey of behavioral health care professionals. SAGE Open Medicine, 8, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312120933152

Wasylko, Y., & Stickley, T. (2007). Promoting emotional development through using drama in mental health education. In T. Stickley & T. Basset (Eds.), Teaching mental health (pp. 297–309). Wiley.

https://doi.org/10.1002/97804470713617.ch25

World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564779

Ashley Ascherl Pechek, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC, is an associate professor at Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania. Kristin A. Vincenzes, PhD, NCC, ACS, BC-TMH, LPC, is a professor at Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania. Kellie Forziat-Pytel, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC, is an assistant professor at Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania. Stephen Nowakowski is a graduate student at Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania. Leandrea Romero-Lucero, PhD, ACS, LPCC, CSOTS, is an associate professor and Clinical Mental Health Counseling Program Director at Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania. Correspondence may be addressed to Ashley Ascherl Pechek, 401 N. Fairview Street, Lock Haven, PA 17745, aap402@commonwealthu.edu.