Melissa Ng Lee Yen Abdullah, See Ching Mey

This study identified the fundamental lifestyles adopted by a university community in Malaysia. Rapid growth and expansion of higher education in Malaysia is inevitable as the country moves from a production-based economy to one that is innovative and knowledge-based, requiring the development of a highly skilled and knowledgeable workforce. Research universities in Malaysia are leading the way in the generation of intellectual property and wealth for the country, as well as enhancing the quality of life of its people. A case study approach found that the university community’s lifestyle is focused on recognitions. Implications for university personnel are discussed.

Keywords: Malaysia, higher education, university community, lifestyle, transformation, BeMIS

Higher education is one of the most dynamic and rapidly growing service sectors in many parts of the world

(Kapur & Crowley, 2011 Lee, 2004; Ministry of Higher Education, 2011a; “Transform Higher Education,”

2011 UNESCO, 2005; Varghese, 2009). In fact, the rapid growth and expansion of the higher education sector in Malaysia is inevitable, as the country is currently moving from a production-based economy to one that is innovative and knowledge-based and requires the development of a highly skilled and knowledgeable workforce (Arokiasamy, 2012). The shift toward a knowledge-based economy in the era of globalization also has contributed to the increasing demand for more and better quality graduates (Lee 2004; Varghese 2009). In order for higher education in Malaysia to remain relevant locally and competitive globally, it must undergo transformation (Levin 2001; “Transform Higher Education,” 2011). The push for excellence in research, innovation and commercial activities is particularly crucial to achieve the national agenda in Malaysia. As

a matter of fact, research universities in Malaysia are now leading the way to generate intellectual property and wealth for the country and to enhance the quality of life of the people (Ismail, 2007). With the changing landscape of higher education in Malaysia, local universities have imposed stricter key performance indicators (KPI) targets on the staff (Azizan, Lim, & Loh, 2012). KPI measures the performance of academic and

non-academic staff and also gauges their eligibility for promotion. The pressure to publish research papers, particularly in top-ranked journals, is an important facet of KPIs as it reflects recognition received by academics in local and international arenas. In addition, academic staff are encouraged to work together with industry and the community to leapfrog multidisciplinary knowledge creation to address social, economic, environmental

and health challenges of the nation or region (Gill, 2012). At the same time, student and staff mobility can be promoted via exchange programs and collaboration with international institutions, which is in line with the internationalization policy outlined by the National Higher Education Strategic Plan (PSPTN) in Malaysia

(Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia, 2011b). This implies that engagement with the local and international community through mobility, research and outreach activities are crucial.

Fundamental Lifestyle

Fundamental lifestyle is a way to segment people into groups based on three things: opinions, attitudes and activities (Harcar, Kaynak, & Kucukemiroglu 2004). As such, it measures peoples’ activities in terms of how they spend their time, interests, where they place importance in their immediate surroundings, and their views of themselves and the world which may differ according to socio-demographic factors (Plummer, 1974). According to Khan (2006), there are four main characteristic lifestyles:

• a group phenomenon that influences society

• influence on all life activities

• implies a central life interest

• affected by social changes in society

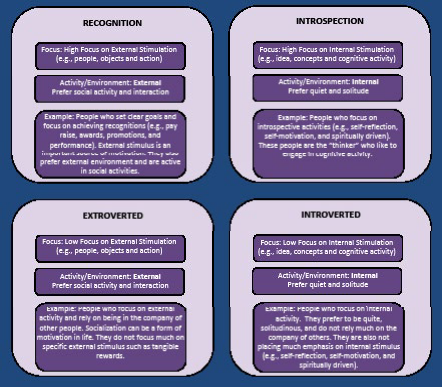

Studies have shown that lifestyle affects the performance of over 80% of employees in organizations (Robertson, 2012) and is a factor that should not be overlooked. Lifestyle can be divided into specific dimensions based on recognizable behaviors (Wells & Tigert, 1971). According to the Center for Credentialing and Education (2009), there are four types of fundamental lifestyles, namely (1) recognition, (2) introspection, (3) extroversion, and (4) introversion (see Figure 1). These lifestyles can be identified through one’s focus and preferred internal/external activities.

Recognition Lifestyle

People with a recognition lifestyle set clear goals, focus on achieving targeted recognition, and prefer external activity. They place importance on external stimulus and believe that recognition will follow suit when performance expectations are met. The recognition may come in the form of a pay raise, awards, promotion, and performance opportunities. These people also prefer external environments such as social activities with a high profile.

Introspection Lifestyle

People with an introspection lifestyle focus on internal activities such as clarifying personal goals and roles, self-reflection, motivation, and spiritual drive. They tend to look inward and constantly think about personal thoughts and feelings (Sedikides, Horton, & Gregg, 2007). They are capable of working independently and engage in high-level cognitive activities and are easily recognized as thinkers.

Extroverted Lifestyle

People with an extroverted lifestyle focus on external activities and rely on being in the company of other people. Extroverted individuals tend to be active, gregarious, impulsive and fond of excitement. They like socialization and perceive it as a source of motivation. As such, a small social network may lead to psychological problems (Grainge, Brugha, & Spiers, 2000). People with such lifestyles also do not often focus on specific external stimuli such as tangible rewards.

Introverted Lifestyle

People with an introverted lifestyle focus on internal activities and prefer to work on their own without relying on the company of others. Hence, a lack of large social networks may be of less concern (Grainge et al.,

2000). People with such a lifestyle also do not often depend on internal processes such as clarifying personal

goals and roles, self-reflection, motivation and spiritual matters.

Figure 1. Descriptors of Lifestyles (Source: Adapted from the Center for Credentialing and Education, 2009).

Lifestyles in University Communities

Currently there is a lack of literature on the fundamental lifestyles of university communities during institutional transformations. Transformation measures undertaken in higher education in Malaysia aim to foster the development of academic and institutional excellence so that higher education institutions (HEIs) can fulfill their roles in meeting the nation’s developmental needs and build its stature both at home and

internationally (Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia, 2011b). Stricter KPIs are being imposed on university staff (Azizan, et al., 2012). The pressure to publish research papers, particularly in top-ranked journals, is an important facet of KPIs as it reflects recognition received by academics in local and international arenas. It is, however, unclear to what extent recognition (such as the push for publication and emphasis on KPIs) plays a role in shaping the lifestyle of the university community in Malaysia. Literature reviews show that emphasis

on external stimuli may create an unhealthy culture as “everyone is rushing to publish papers to meet the KPI… they want to be recognized internationally” and published in top-ranked journals (Azizan, et al., 2012, p.1). For this reason, empirical studies are needed to explore the types of lifestyles adopted by university communities. Investigations also need to examine the variation that may exist among the different categories of university

communities, namely higher administrators, academics, administrative officers, support staff, postgraduates and undergraduates. Such data are vital in helping HEIs keep track of staff and students’ development during higher education transformation. Based on the findings, strategic planning at the institutional level can be implemented accordingly. To fill in the literature gap, this study aims to identify the lifestyle of the university community

as a whole and also describe the lifestyle adopted by the different categories of the community. The research objectives were (1) to identify the lifestyle of the university community, and to (2) describe the lifestyle of administrators, academics, administrative officers, support staff, postgraduates and undergraduates.

Methodology

An exploratory case study method was used to conduct the investigation at a research-intensive university in Malaysia. Based on a list of staff and students at this institution, 520 targeted participants were randomly chosen as shown in Table 1. Official invitation letters, general information about the research and consent forms were sent out to all targeted participants.

Table 1

Participants in the Study

| Participants | ||||

| Categories | Targeted |

F |

% | |

| Higher Administrators |

40 |

39 |

11.27 | |

| Academic Staff |

100 |

59 |

17.05 | |

| Administrative Officers |

100 |

38 |

10.98 | |

| Support Staff |

100 |

68 |

19.65 | |

| Postgraduate Students |

100 |

80 |

23.12 | |

| Undergraduate Students |

100 |

62 |

17.91 | |

| Total |

520 |

346 | 100.00 | |

A total of 346 respondents voluntarily agreed to participate in this study; 39 higher administrators, 59 academic staff, 38 administrative officers, 68 support staff, 80 postgraduate students and 62 undergraduate students.

The Behavioral Management Information System (BeMIS), an online assessment and reporting tool, was used as the instrument to identify the lifestyle of the university community. The underlying instrument includes the Adjective Check List (ACL), which comprises of 300 adjectives commonly used to describe

traits that a person subscribed to and these traits can be grouped into four major lifestyles, namely recognition, introspection, introverted or extroverted (Gough & Heirbrum; 1980, 1983, 2010; Measurement and Planned Development, 2010).The validity of the instrument is well established in the literature and has been adopted

in nearly 1,000 research reports (Essentials, 2010). The reliability of the instrument was pilot tested and

established before the study began. Results showed that the satisfactory reliability with Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.74 to 0.97. The BeMIS system is capable of plotting lifestyle into a four-quadrant graph (Center for Credentialing and Education, 2009). The report presents the participants’ real- and preferred-self lifestyle. Real-self refers to one’s current lifestyle while the preferred-self indicates the person’s desired lifestyle.

The data collection was completed via an online system. Each participant was provided with a password to access the BeMIS website. As such, the participants could provide responses and submit them online. The data were analyzed using BeMIS proprietary software and the results are presented as standard scores. The acceptable ranges of scores range from 40 to 60. Any score that exceeds 70 or is less than 30 is considered too extreme and reflects dissatisfaction with life (Gough & Heilbrun, 2010).

Results and Discussion

The results of this study are presented and discussed according to the two main objectives of the study, which were to identify the lifestyle of the university community as a whole and to describe the lifestyle adopted by the different subgroups of the university community.

Lifestyle of the University Community

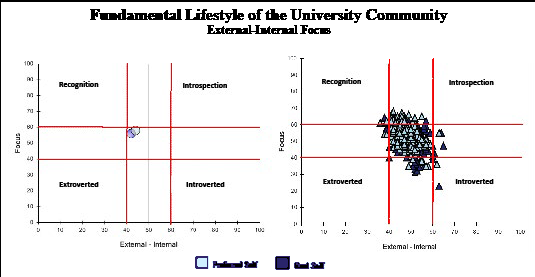

The four-quadrant graph reveals that the university community’s lifestyle (real-self) is at the recognition quadrant whereby recognitions such as pay raises, awards, promotions and performance opportunities are very much the focus of life. The university community’s preferred lifestyle indicates that they seek higher recognition. There are indications that the community’s focus may be moving towards the introspection

quadrant (see Figure 2). As a whole, the university community is likely to set clear goals and focus on achieving targeted recognitions. Their external lifestyle also suggests that the community is currently active in social and community activities.

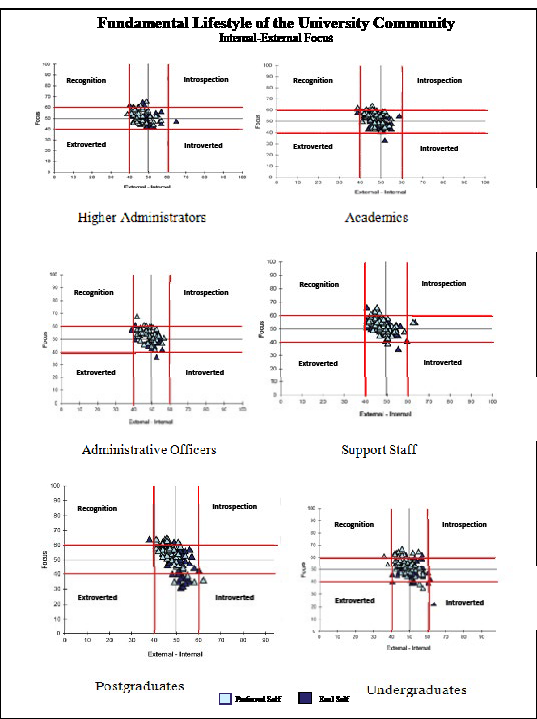

The scatter plot in Figure 2 demonstrates that there are variations in lifestyle adopted by the university community. Most of the respondents’ scores are within the acceptable range of 40–60, with a few notable outliers. To further examine the findings, there are needs to examine the lifestyles of the university community according to the six subgroups of participants; higher administrator, academics, administrative officers, support staff, postgraduates and undergraduates.

Lifestyle of Higher Administrators

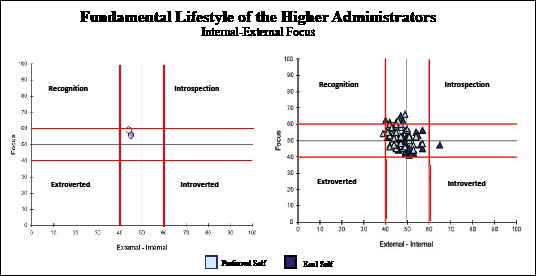

The four-quadrant graph shows that as a whole the higher administrators’ real-self lifestyle is within the recognition quadrant (see Figure 3). Their focus on recognition is slightly above the score of 60, indicating an emphasis on recognition. Recognition may come in the form of pay raises, awards, promotions and performance opportunities. Nevertheless, the higher administrators are sociable and likely to have high profiles among the university community. Higher administrators’ focus on recognition seems to be lower in the preferred lifestyle which indicates they prefer to lower their focus on recognitions.

The scatter plot in Figure 3 demonstrates that even though there are variations in the lifestyle of higher administrators, their scores are still within the acceptable range of 40–60, except for a few outliers located at the recognition and introversion quadrants. These outliers indicate that a small number of the higher

administrators may be focusing too much on recognition. This could potentially cause dissatisfaction in life if their expectations are not met (Gough & Heilbrun, 2010). One of the higher administrator’s scores is considered extreme in introverted behavior, implying that this individual prefers to work alone, does not often self-reflect or self-motivate, and is not keen on social activities.

Figure 2. Fundamental Lifestyle of the University Community

Figure 3. Lifestyle of Higher Administrators

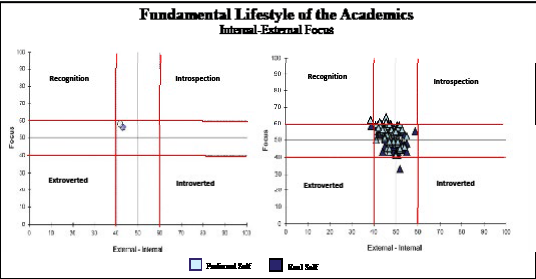

Lifestyle of Academics

The four-quadrant graph shows that as a whole, the academics’ lifestyles, both real and preferred-self, are located at the recognition quadrant (see Figure 4). They are likely to set clear goals and focus on achieving recognitions like pay raises, awards, promotions and performance opportunities. Their emphasis on recognitions is still within the acceptable range of 40–60 and is unlikely to cause any negative impact on psychosocial wellbeing (Gough & Heilbrun, 2010). In addition, academics’ focus on an external lifestyle suggests they are active in social and community activities.

Figure 4. Lifestyle of Academics

The scatter plot in Figure 4 further demonstrates that even though academics may adopt different lifestyles, their scores are within the acceptable range of 40–60 (except for a few notable outliers).

Their extreme scores are found in the recognition and introverted quadrants. These outliers indicate that a small number of academics are focusing too much on recognition, which could potentially cause dissatisfaction in life if their expectations are not met (Gough & Heilbrun, 2010). One of the academic staff is extreme in introverted behavior suggesting that this professor prefers to work by himself, is not keen on social and community activities, and is often not engaging in introspective activities such as self-reflection, self- motivation and spirituality.

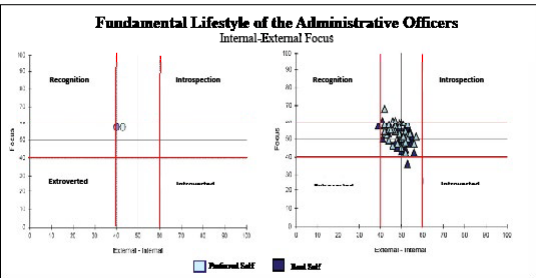

Lifestyles of Administrative Officers

The four-quadrant graph shows that as a whole the administrative officers’ real and preferred lifestyle is located at the recognition quadrant (Figure 5). Their focus on external stimuli suggests that recognitions such as pay raises, awards, promotions and performance opportunities are important sources of motivation. Their emphasis on recognitions is still within the acceptable range of 40–60, thus it is unlikely to cause negative impact (Gough & Heilbrun, 2010). Figure 5 also reveals that the officers’ lifestyle is rather external in nature.

In other words, they engage more in external activities and rely on being in the company of other people. Nevertheless, their preferred lifestyle indicates that they wish for lesser external activity.

Figure 5 shows that the administrative officers’ lifestyle distribution scattered in four different lifestyle categories. Generally, the scores for all four different lifestyles are within the acceptable range of 40–60, except for a few outliers found in the recognition and introversion quadrants. These outliers indicate that a small number of administrative staff are focusing too much on recognition which could potentially cause dissatisfaction in life if their expectations are not met (Gough & Heilbrun, 2010). One of the administrative

officers is extremely introverted in his or her lifestyle, suggesting that the officer likes to work by himself, is not keen on social or community activities, and is not much involved in self-reflection or self-motivation.

Figure 5. Lifestyle of Administrative Officers

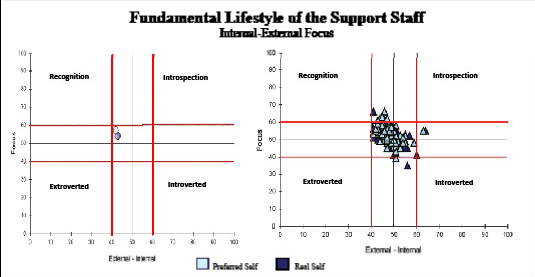

Lifestyles of Support Staff

The four-quadrant graph shows that as a whole, the support staff’s real and preferred lifestyle is within the recognition quadrant (Figure 6). Nevertheless, the support staff appear to be active in social activities and seem to prefer higher level recognition.

The scatter plot in Figure 6 reveals that most of the support staff’s scores are within the acceptable range of 40–60, except for a few outliers located at the recognition, introspection and introverted quadrants. These outliers indicate that a small number of support staff are focusing too much on recognition which could potentially cause dissatisfaction in life if their expectations are not met (Gough & Heilbrun, 2010). Support staff with rather extreme introversion and introspection behaviors are those who prefer to work by themselves and do not like to socialize or engage in introspective activities (e.g., self-reflect).

Figure 6. Lifestyle of Support Staff

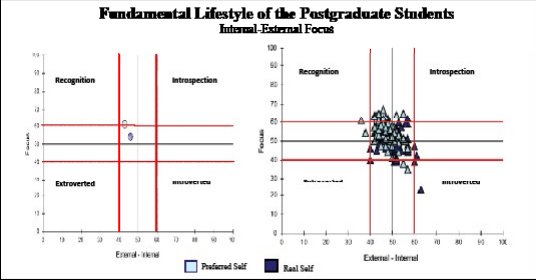

Lifestyles of Postgraduate Students

The four-quadrant graph shows that as a whole the fundamental lifestyle of the postgraduate students falls into the recognition quadrant (Figure 7). The findings suggest that academic achievement, awards and recognition are important sources of motivation for the majority of students at the postgraduate level. In fact, they prefer higher recognition, as indicated by their preferred self-scores.

Figure 7 also reveals that the score distributions recorded by the postgraduate students clustered around the acceptable range of 40–60 with a slight tilt toward the introverted quadrant. A high number of postgraduate students with introverted behavior may suggest that the students tend to work in silos when seeking recognition, and students with extreme scores are not actively socializing with others. In fact, they also do not engage

much in introspective activities (e.g., self-reflection). Such a scenario may not be considered as positive in that

postgraduate students are expected to be learners who engage actively in thinking and research activities.

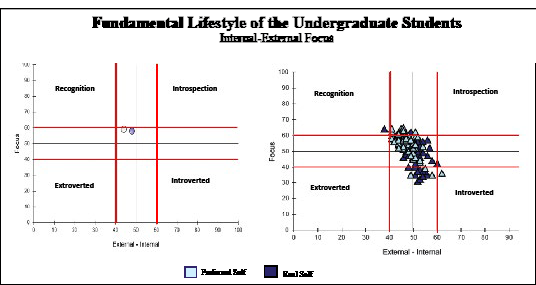

Lifestyles of Undergraduate Students

The four-quadrant graph shows that as a whole the undergraduate students’ lifestyle (both real- and preferred-self) is within the recognition quadrant (Figure 8).The findings suggest that academic achievement, awards and other forms of recognition are very important for the majority of undergraduate students.

The scatter plot in Figure 8 reveals that most undergraduate students’ scores clustered around the acceptable range of 40–60; however, a number of the students’ scores tilted toward the introverted quadrant. This

result shows that some undergraduate students are introverted in their lifestyle and do not engage much in

introspective activities (e.g., self-reflection).

Figure 7. Lifestyle of Postgraduate Students

Figure 8. Lifestyle of Undergraduate Students

Summary and Conclusion

The lifestyles of the university subgroups are summarized in Figure 9. The findings reveal that the distribution of scores for three groups of participants, namely support staff, postgraduate students and undergraduate students, tilt more toward the introverted quadrant. Their inclination toward introverted behaviors seems to be higher than those holding administrative and academic positions such as administrative officers, academics and higher administrators.

In conclusion, recognitions such as pay raises, awards and promotion are very much the focus of

the university community. Past studies have indicated that recognition has a significant impact on one’s performance. It is an external stimulus to achieve a targeted goal (Ali & Ahmad, 2009; Deci, 1971; Gomez- Mejia & Balkin, 1992). Therefore, the pay system can be utilized as a mechanism to direct employees toward achieving the organization’s strategic objectives (Gomez-Mejia & Balkin, 1992). In fact, employees’ job satisfaction is significantly related to recognitions like pay raise and promotion (Ali & Ahmed, 2009). Ch’ng, Chong, and Nakesvari (2010) found that the job satisfaction of lecturers in Malaysia is related to salary and promotion opportunities. Since the appraisal and promotions system at local HEIs are based on KPIs (Azizan et al., 2012), the university staff can strategically align their goals toward achieving the institution’s targets. The implementation of KPIs can indeed create a new mindset among academic and non-academic staff (Kaur,

2012), particularly when the focus of the university community is on recognitions. In other words, it is possible to move the university community as a concerted force to attain the institution’s KPIs.

Even though recognitions can be a positive external stimulus to directly enhance the job performance of members of the university community, overemphasis on recognitions can result in dissatisfaction among staff and students if expectations regarding recognitions are not met (Gough & Heilbrun, 2010). In fact, the pressure to publish research papers, particularly in top-ranked journals, and the push to place Malaysian universities among the top 100 worldwide have caused concerns among academia (Lim & Kulasagaran, 2012). However, academia is more than publishing in journals; teaching and learning are equally crucial. Academics play

a central role in stimulating intellectual discussions and mentoring students. They must have passion and genuine interest in teaching as well as conducting research activities, and not just be driven by KPIs to achieve recognition. In order to do so, academic staff must possess internal motivation such as interests and the passion to teach, conduct research, disseminate knowledge and create innovations.

In addition, this study found that the university community prefers an external lifestyle. They are active in social and community activities, which is in line with the institution’s move toward industry and community engagement. For instance, research and consultation projects aim to fulfill societal needs. The external lifestyle also contributes to collaborative research and industrial and community engagement. Even so, there are still members of the university who are extremely introverted in their lifestyles. They prefer to work and study in silos, not becoming active in social and community activities, apart from not looking much into their inner-

self in order to self-reflect, self-motivate and self-improve. This situation is more pertinent among support staff, postgraduate and undergraduate students. These findings are not encouraging, particularly among the postgraduate students, as they are expected to be active and engaging learners.

Finally, the university should take measures to address the development of its staff. Support services need to be made available for those who feel isolated and have more introverted behaviors. Mental health support systems and counseling services also are crucial to sustain the well-being of the university community during institutional transformations.

Figure 9. Lifestyles across the Subgroups of the University Community

References

Ali, R., & Ahmad, M. S. (2009). The impact of reward and recognition programs on employee’s motivation and satisfaction a co-relational study. International Review of Business Research, 5, 270–279.

Arokiasamy, A. R. (2012, June 4). The impact of globalisation on higher education in Malaysia. Retrieved from http://www.nyu.edu/classes/keefer/waoe/aroka.pdf

Azizan, H., Lim, R., & Loh, J. (2012, November 30). The KPI dilemma, The Star Online. Retrieved from

http://thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?sec=focus&file=/2010/9/26/focus/7105830

Center for Credentialing and Education. (2009). The BeMIS Personality Report for Sample Client. Greensboro, NC: Author.

Ch’ng, H. K., Chong, W. K., & Nakesvari. (2010). The satisfaction level of Penang private college lecturers.

International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, 1, 168–172.

Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 18, 105–115.

onesourcehealthcareers.com/1/122/files/TheAdjectiveChecklist.pdf

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Balkin, D. B. (1992). Determinants of faculty pay: An agency theory perspective.

Academy of Management Journal, 35, 921–955.

Gough, H. G., & Heibrum, A. B. (2010, February 28). Assess psychological traits with a full sphere of

descriptive. Retrieved fromhttp://www.mindgarden.com/products/figures/aclresearch.htmphy

Gough, H. G., & Heilbrun, A. B. (1983). The adjective check list manual: 1983 Edition. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Gough, H. G., & Heilbrun, A. B. (1980). The adjective Check list manual: 1980 Edition. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Grainge, M. J., Brugha, T. S., & Spiers, N. (2000). Social support, personality and depressive symptoms over

7 years: The health and lifestyle cohort. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 35, 366–374. Gill, S. K. (2012, June 5). Transforming higher education through social responsibility and sustainability

across the Asian Region. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/56/36/47123532.pdf

Harcar, T., Kaynak, E., & Kucukemiroglu, O. (2004). Life style orientation of us and Canadian consumers: Are region-centric standardized marketing strategies feasible. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistic, 20, 433–454.

Ismail, A. (2007, December). Malaysia issues on research, development, and commercialization. Paper presentation at the Regional Higher Education Conference: Strategic Choices for Higher Education Reform, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Kapur, D., & Crowley, M. (2011, August 12). Beyond the ABCs: Higher education and developing countries.

Center for Global Development. Retrieved from http://www.scribd.com/doc/23944913/Higher- Education-and-Developing-Countries

Khan, M. (2006). Consumer behaviour and advertising management. New Delhi, India: New Age

International.

Kaur, S. (2012, November 30). Playing a numbers game. Retrieved from http://thestar.com.my/education/

story.asp?file=/2009/9/6/education/4643997

Lee, J. K. (2004, August 17). Globalization and Higher Education: A South Korean Perspective. Retrieved from http://globalization.icaap.org/content/v4.1/lee.html

Levin, J. S. (2001). Public Policy, Community Colleges, and the Path to Globalization, Higher Education, 42

(2), 237–261.

Lim, R., & Kulasagaran, P. (2012, November 30). Push for rankings stirs trouble. The Star, Retrieved from

http://thestar.com.my/education/story.asp?file=/2011/8/28 /education/9383292&sec=education

Measurement and Planned Development. (2010, 19 April). Fundamental Lifestyles. Retrieved from http://www.personalitycheckup.com/html/example.html

Ministry of Higher Education. (2011a). The national higher education strategic plan: Beyond 2020. Putrajaya, Malaysia: Author.

Ministry of Higher Education. (2011b). Internationalisation policy for higher education Malaysia 2011.

Putrajaya, Malaysia: Author.

Plummer, J. T. (1974). The concept and application of life style segmentation. Journal of Marketing, 38, 33–37. Robertson, P. (2012, May 16). Lifestyle affects work for over 80% of employees. Retrieved from

www.covermagazine.co.uk/…/lifestyle-affects-80-employees

Sedikides, C., Horton, R. S., & Gregg, A. P. (2007). The why’s the limit: curtailing self-enhancement with explanatory introspection. Journal of Personality, 7, 783–824. (doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00457.x).

Transform Higher Education to Produce Globally Competitive Workforce. (2011, August 15). Retrieved from http://www.bernama.com/bernama/v3/news_lite.php?id=513166

UNESCO. (2005). Towards knowledge societies. Paris, France: Author.

Varghese, N. V. (2009) (Ed.). Higher education reforms: Institutional restructuring in Asia. Paris, France: International Institute for Educational Planning.

Wells, W. D., & Tigert, D. J. (1971). Activities, interests and opinions. Journal of Advertising Research, 11,

27–35.

Melissa Ng Lee Yen Abdullah is a Senior Lecturer and See Ching Mey is Deputy Vice-Chancellor at the Universiti Sains Malaysia. Correspondence can be addressed to 1180 USM, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, melissa@usm.my. Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from RU Grant (1001/PGURU/816144) and also the assistance received from Dr. Daniel R. Collins and Dr. J. Scott Hinkle, as well as the contribution of all the AURA team members, in conducting this study.