Apr 5, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 1

Melodie H. Frick, Harriet L. Glosoff

Counselor education doctoral students are influenced by many factors as they train to become supervisors. One of these factors, self-efficacy beliefs, plays an important role in supervisor development. In this phenomenological, qualitative research, 16 counselor education doctoral students participated in focus groups and discussed their experiences and perceptions of self-efficacy as supervisors. Data analyses revealed four themes associated with self-efficacy beliefs: ambivalence in the middle tier of supervision, influential people, receiving performance feedback, and conducting evaluations. Recommendations for counselor education and supervision, as well as future research, are provided.

Keywords: supervision, doctoral students, counselor education, self-efficacy, phenomenological, focus groups

Counselor education programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) require doctoral students to learn supervision theories and practices (CACREP, 2009). Professional literature highlights information on supervision theories (e.g., Bernard & Goodyear, 2009), supervising counselors-in-training (e.g., Woodside, Oberman, Cole, & Carruth, 2007), and effective supervision interventions and styles (e.g., Fernando & Hulse-Killacky, 2005) that assist with supervisor training and development. Until recently, however, few researchers have studied the experiences of counselor education doctoral students as they prepare to become supervisors (Hughes & Kleist, 2005; Limberg et al., 2013; Protivnak & Foss, 2011) or “the transition from supervisee to supervisor” (Rapisarda, Desmond, & Nelson, 2011, p. 121). Specifically, an exploration of factors associated with the self-efficacy beliefs of counselor education doctoral student supervisors is warranted to expand this topic and enhance counselor education training of supervisor development.

Bernard and Goodyear (2009) described supervisor development as a process shaped by changes in self-perceptions and roles, much like counselors-in-training experience in their developmental stages. Researchers have examined factors that may influence supervisors’ development (e.g., experiential learning and the influence of feedback). For example, Nelson, Oliver, and Capps (2006) explored the training experiences of 21 doctoral students in two cohorts of the same counseling program and reported that experiential learning, the use of role-plays, and receiving feedback from both professors and peers were equally as helpful in learning supervision skills as the actual practice of supervising counselors-in-training. Conversely, a supervisor’s development may be negatively influenced by unclear expectations of the supervision process or dual relationships with supervisees, which may lead to role ambiguity (Bernard & Goodyear, 2009). For example, Nilsson and Duan (2007) examined the relationship between role ambiguity and self-efficacy with 69 psychology doctoral student supervisors and found that when participants received clear supervision expectations, they reported higher rates of self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy is one of the self-regulation functions in Bandura’s social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and is a factor in Larson’s (1998) social cognitive model of counselor training (SCMCT). Self-efficacy, the differentiated beliefs held by individuals about their capabilities to perform (Bandura, 2006), plays an important role in counselor and supervisor development (Barnes, 2004; Cashwell & Dooley, 2001) and is influenced by many factors (Schunk, 2004). Along with the counselor’s training environment, self-efficacy beliefs may influence a counselor’s learning process and resulting counseling performance (Larson, 1998). Daniels and Larson (2001) conducted a quantitative study with 45 counseling graduate students and found that performance feedback influenced counselors’ self-efficacy beliefs; self-efficacy increased with positive feedback and decreased with negative feedback. Steward (1998), however, identified missing components in the SCMCT, such as the role and level of self-efficacy of the supervisor, the possible influence of a faculty supervisor, and doctoral students giving and receiving feedback to supervisees and members of their cohort. For example, results of both quantitative studies (e.g., Hollingsworth & Fassinger, 2002) and qualitative studies (e.g., Majcher & Daniluk, 2009; Nelson et al., 2006) indicate the importance of mentoring experiences and relationships with faculty supervisors to the development of doctoral students and self-efficacy in their supervisory skills.

During their supervision training, doctoral students are in a unique position of supervising counselors-in-training while also being supervised by faculty. For the purpose of this study, the term middle tier will be used to describe this position. This term is not often used in the counseling literature, but may be compared to the position of middle managers in the business field—people who are subordinate to upper managers while having the responsibility of managing subordinates (Agnes, 2003). Similar to middle managers, doctoral student supervisors tend to have increased responsibility for supervising future counselors, albeit with limited authority in supervisory decisions, and may have experiences similar to middle managers in other disciplines. For example, performance-related feedback as perceived by middle managers appears to influence their role satisfaction and self-efficacy (Reynolds, 2006). In Reynolds’s (2006) study, 353 participants who represented four levels of management in a company in the United States reported that receiving positive feedback from supervisors had an affirming or encouraging effect on their self-efficacy, and that their self-efficacy was reduced after they received negative supervisory feedback. Translated to the field of counselor supervision, these findings suggest that doctoral students who participate in tiered supervision and receive positive performance feedback may have higher self-efficacy.

Findings to date illuminate factors that influence self-efficacy beliefs, such as performance feedback, clear supervisor expectations and mentoring relations. There is a need, however, to examine what other factors enhance or detract from the self-efficacy beliefs of counselor education doctoral student supervisors to ensure effective supervisor development and training. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to build on previous research and further examine the experiences of doctoral students as they train to become supervisors in a tiered supervision model. The overarching research questions that guided this study included: (a) What are the experiences of counselor education doctoral students who work within a tiered supervision training model as they train to become supervisors? and (b) What experiences influenced their sense of self-efficacy as supervisors?

Method

Design

A phenomenological research approach was selected to explore how counselor education doctoral students experience and make meaning of their reality (Merriam, 2009), and to provide richer descriptions of the experiences of doctoral student supervisors-in-training, which a quantitative study may not afford. A qualitative design using a constructivist-interpretivist method provided the opportunity to interact with doctoral students via focus groups and follow-up questionnaires to explore their self-constructed realities as counselor supervisors-in-training, and the meaning they placed on their experiences as they supervised master’s-level students while being supervised by faculty supervisors. Focus groups were chosen as part of the design, as they are often used in qualitative research (Kress & Shoffner, 2007; Limberg et al., 2013), and multiple-case sampling increases confidence and robustness in findings (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Participants

Sixteen doctoral students from three CACREP-accredited counselor education programs in the southeastern United States volunteered to participate in this study. These programs were selected due to similarity in supervision training among participants (e.g., all were CACREP-accredited, required students to take at least one supervision course, utilized a full-time cohort design), and were in close proximity to the principal investigator. None of the participants attended the first author’s university or had any relationships with the authors. Criterion sampling was used to select participants that met the criteria of providing supervision to master’s-level counselors-in-training and receiving supervision by faculty supervisors at the time of their participation. The ages of the participants ranged from 27–61 years with a mean age of 36 years (SD = 1.56). Fourteen of the participants were women and two were men; two participants described their race as African-American (12.5%), one participant as Asian-American (6.25%), 12 participants as Caucasian (75%), and one participant as “more than one ethnicity” (6.25%). Seven of the 16 participants reported having 4 months to 12 years of work experience as counselor supervisors (M = 2.5 years, SD = 3.9 years) before beginning their doctoral studies. At the time of this study, all participants had completed a supervision course as part of their doctoral program, were supervising two to six master’s students in the same program (M = 4, SD = 1.2), and received weekly supervision with faculty supervisors in their respective programs.

Researcher Positionality

In presenting results of phenomenological research, it is critical to discuss the authors’ characteristics as researchers, as such characteristics influence data collection and analysis. The authors have experience as counselors, counselor educators, and clinical supervisors. Both authors share an interest in understanding how doctoral students move from the role of student to the role of supervisor, especially when providing supervision to master’s students who may experience critical incidents (with their clients or in their own development). The first author became engaged when she saw the different emotional reactions of her cohort when faced with the gatekeeping process, whether the reactions were based on personality, prior supervision experience, or stressors from inside and outside of the counselor education program. She wondered how doctoral students in other programs experienced the aforementioned situations, what kind of structure other programs used to work with critical incidents that involve remediation plans, and if there were ways to improve supervision training. It was critical to account for personal and professional biases throughout the research process to minimize biases in the collection or interpretation of data. Bracketing, therefore, was an important step during analysis (Moustakas, 1994) to reduce researcher biases. The first author accomplished this by meeting with her dissertation committee and with the second author throughout the study, as well as using peer reviewers to assess researcher bias in the design of the study, research questions, and theme development.

Quality and Trustworthiness

To strengthen the rigor of this study, the authors addressed credibility, dependability, transferability and confirmability (Merriam, 2009). One way to reinforce credibility is to have prolonged and persistent contact with participants (Hunt, 2011). The first author contacted participants before each focus group to convey the nature, scope and reasons for the study. She facilitated 90-minute focus group discussions and allowed participants to add or change the summary provided at the end of each focus group. Further, information was gathered from each participant through a follow-up questionnaire and afforded the opportunity for participants to contact her through e-mail with additional questions or thoughts.

By keeping an ongoing reflexive journal and analytical memos, the first author addressed dependability by keeping a detailed account throughout the research study, indicating how data were collected and analyzed and how decisions were made (Merriam, 2009). The first author included information on how data were reduced and themes and displays were constructed, and the second author conducted an audit trail on items such as transcripts, analytic memos, reflection notes, and process notes connecting findings to existing literature.

Through the use of rich, thick description of the information provided by participants, the authors made efforts to increase transferability. In addition, they offered a clear account of each stage of the process as well as the demographics of the participants (Hunt, 2011) to promote transferability.

Finally, the first author strengthened confirmability by examining her role as a research instrument. Selected colleagues chosen as peer reviewers (Kline, 2008), along with the first author’s dissertation committee members, had access to the audit trail and discussed and questioned the authors’ decisions, further increasing the integrity of the design. Two doctoral students who had provided supervision and had completed courses in qualitative research, but who had no connection to the research study, volunteered to serve as peer reviewers. They reviewed the focus group protocol for researcher bias, read the focus group transcripts (with pseudonyms inserted) and questionnaires, and the emergent themes, to confirm or contest the interpretation of the data. Further, they reviewed the quotes chosen to support themes for richness of description and provided feedback regarding the textural-structural descriptions as they were being developed. Their recommendations, such as not having emotional reactions to participants’ comments, guided the authors in data collection and analysis.

Data Collection

Upon receiving approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board, the first author contacted the directors of three CACREP-accredited counselor education programs and discussed the purpose of the study, participants’ rights, and logistical needs. Program directors disseminated an e-mail about this study to their doctoral students, instructing volunteer participants to contact the first author about participating in the focus groups.

Within a two-week period, she conducted three focus groups—one at each counselor education program site. Each focus group included five to six participants and lasted approximately 90 minutes. She employed a semi-structured interview protocol consisting of 17 questions (see Appendix). The questions were based on an extensive literature review on counselor and supervisor self-efficacy studies (e.g., Bandura, 2006; Cashwell & Dooley, 2001; Corrigan & Schmidt, 1983; Fernando & Hulse-Killacky, 2005; Gore, 2006; Israelashvili & Socher, 2007; Steward, 1998; Tang et al., 2004). The initial questions were open and general at first, so as to not lead or bias the participants in their responses. As the focus groups continued, the first author explored more specific information about participants’ experiences as doctoral student supervisors, focusing questions around their responses (Kline, 2008). Conducting a semi-structured interview with participants ensured that she asked specific questions and addressed predetermined topics related to the focus of the study, while also allowing for freedom to follow up on relevant information provided by participants during the focus groups.

Approximately six to eight weeks after each focus group, participants received a follow-up questionnaire consisting of four questions: (a) What factors (inside and outside of the program) influence your perceptions of your abilities as a supervisor? (b) How do you feel about working in the middle tier of supervision (i.e., working between a faculty supervisor and the counselors-in-training that you supervise)? (c) What, if anything, could help you feel more competent as a supervisor? (d) How can your supervision training be improved? The purpose of the follow-up questions was to explore participants’ responses after they gained more experiences as supervisors and to provide a means for them to respond to questions about their supervisory experiences privately, without concern of peer judgment.

Data Analysis

Data analysis began during the transcription process, with analysis occurring simultaneously with the collection of the data. The first author transcribed, verbatim, the recording of each focus group and changed participant names to protect their anonymity. Data analysis was then conducted in three stages: first, data were analyzed to identify significant issues within each focus group; second, data were cross-analyzed to identify common themes across all three focus groups; and third, follow-up questionnaires were analyzed to corroborate established themes and to identify additional, or different themes.

During data analysis, a Miles and Huberman (1994) approach was employed by using initial codes from focus-group question themes. Inductive analysis occurred with immersion in the data by reading and rereading focus group transcripts. It was during this immersion process that the first author began to identify core ideas and differentiate meanings and emergent themes for each focus group. She accomplished data reduction by identifying themes in participants’ answers to the interview protocol and focus group discussions until saturation was reached, and displayed narrative data in a figure to organize and compare developed themes. Finally, she used deductive verification of findings with previous research literature. During within-group analysis, she identified themes if more than half (i.e., more than three participants) of a focus group reported similar experiences, feelings or beliefs. Likewise, in across-group analyses, she confirmed themes if statements made by more than half (more than eight) of the participants matched. There were three cases in which the peer reviewers and the first author had differences of opinion on theme development. In those cases, she made changes guided by the suggestions of the peer reviewers. In addition, she sent the final list of themes related to the research questions to the second author and other members of the dissertation committee for purposes of confirmability.

Results

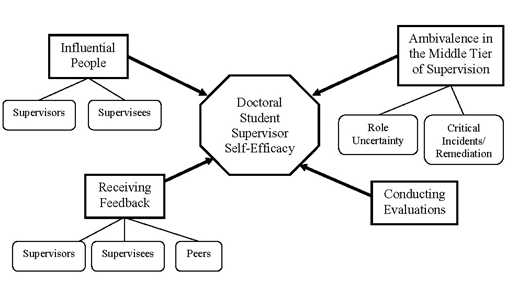

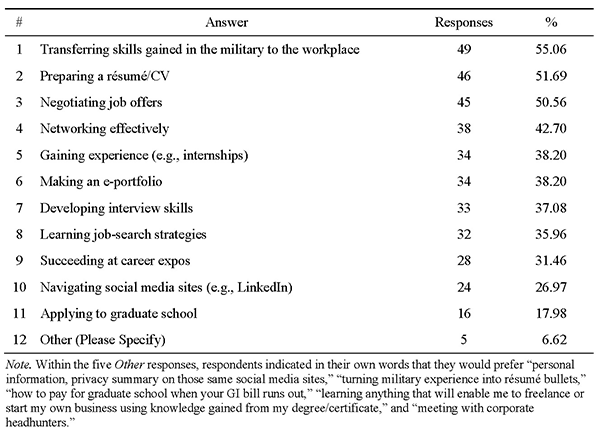

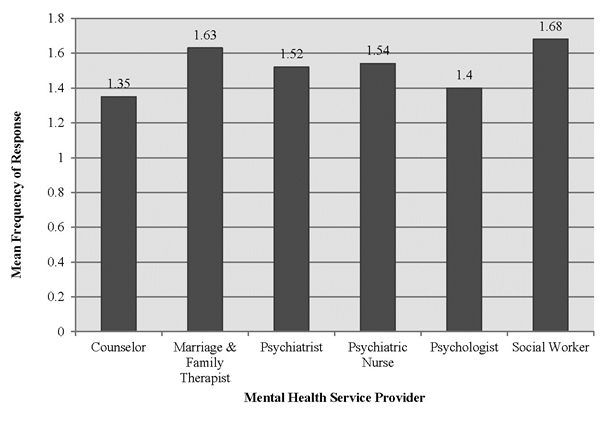

Results of this phenomenological study revealed several themes associated with doctoral students’ perceptions of self-efficacy as supervisors (see Figure 1). Cross-group analyses are provided with participant quotes that are most relevant to each theme being discussed. Considerable overlap of four themes emerged across groups: ambivalence in the middle tier of supervision, influential people, receiving feedback, and conducting evaluations.

Figure 1. Emergent themes of doctoral student supervisors’ self-efficacy beliefs. Factors identified by doctoral student as affecting their self-efficacy as supervisors are represented with directional, bold-case arrows from each theme toward supervisor self-efficacy; below themes are sub-themes in each group connected with non-directional lines.

Ambivalence in the Middle Tier of Supervision

All participants noted how working in the middle tier of supervision brought up issues about their roles and perceptions about their capabilities as supervisors. All 16 participants reported feeling ambivalent about working in the middle tier, especially in relation to their role as supervisors and about dealing with critical incidents with supervisees involving the need for remediation. What follows is a presentation of representative quotations from one or two participants in the emergent sub-themes of role uncertainty and critical incidents/remediation.

Role Uncertainty. Participants raised the issue of role uncertainty in all three focus groups. For example, one participant described how it felt to be in the middle tier by stating the following:

I think that’s exactly how it feels [to be in the middle] sometimes….not really knowing how much you know, what does my voice really mean? How much of a say do we have if we have big concerns? And is what I recognize really a big concern? So I think kind of knowing that we have this piece of responsibility but then not really knowing how much authority or how much say-so we have in things, or even do I have the knowledge and experience to have much say-so?

Further, another participant expressed uncertainty regarding her middle-tier supervisory role as follows:

[I feel a] lack of power, not having real and true authority over what is happening or if something does happen, being able to make those concrete decisions…Where do I really fit in here? What am I really able to do with this supervisee?…kind of a little middle child, you know really not knowing where your identity really and truly is. You’re trying to figure out who you really are.

Participants also indicated difficulty discerning their role when supervising counselors-in-training who were from different specialty areas such as college counseling, mental health counseling, and school counseling. All participants stated that they had not had any specific counseling or supervision training in different tracks, which was bothersome for nine participants who supervised students in specialties other than their own. For example, one participant stated the following:

I’m a mental health counselor and worked in the community and I have two school counselor interns, and so it was one of my very first questions was like, what do I do with these people? ’Cause I’m not aware of the differences and what I should be guiding them on anything.

Another participant noted how having more information on the different counseling tracks (e.g., mental health, school, college) would be helpful:

We’re going to be counselor educators. We may find ourselves having to supervise people in various tracks and I could see how it would be helpful for us to all have a little bit more information on a variety of tracks so that we could know what to offer, or how things are a little bit different.

Working in the middle tier of supervision appeared to be vexing for focus group participants. They expressed feelings of uncertainty, especially in dealing with critical incidents or remediation of supervisees. In addition to defining their roles as supervisors in the middle tier, another sub-theme emerged in which participants identified how they wanted to have a better understanding of how remediation plans work and have the opportunity to collaborate with faculty supervisors in addressing critical incidents with supervisees.

Critical Incidents/Remediation. Part of the focus group discussion centered on what critical incidents participants had with their supervisees and how comfortable they were, or would be, in implementing remediation plans with their supervisees. All participants expressed concerns about their roles as supervisors when remediation plans were required for master’s students in their respective programs and were uncertain of how the remediation process worked in their programs. Thirteen of the 16 participants expressed a desire to be a part of the remediation process of their supervisees in collaboration with faculty supervisors. They discussed seeing this as an important way to learn from the process, assuming that as future supervisors and counselor educators they will need to be the ones to implement such remediation plans. For example, one participant explained the following:

If we are in the position to provide supervision and we’re doing this to enhance our professional development so in the hopes that one day we’re going to be in the position of counselor educators, let’s say faculty supervisors, my concern with that is how are we going to know what to do unless we are involved [in the remediation process] now? And so I feel like that should be something that we’re provided that opportunity to do it.

Another participant indicated that she felt not being part of the remediation process took away the doctoral student supervisors’ credibility:

I don’t have my license yet, and I’m not sure how that plays into when there is an issue with a supervisee, but I know when there is an issue, there is something we have to do if you have a supervisee who is not performing as well, then that’s kind of taken out of your hands and given to a faculty. So they’re like, ‘Yeah you are capable of providing supervision,’ but when there’s an issue it seems like you’re no longer capable.

Another participant noted wanting “to see us do more of the cases where we need to do remediation” in order to be better prepared in identifying critical incidents, thus feeling more capable in the role as supervisor. Discussion on the middle tier proved to be a topic participants both related to and had concerns about. In addition to talking about critical incidents and the remediation process, another emergent theme included people within the participants’ training programs who were influential to their self-efficacy beliefs as supervisors.

Influential People

When asked about influences they had from inside and outside of their training programs, all participants identified people and things (e.g., previous work experience, support of significant others, conferences, spiritual meditation, supervision literature) as factors that affected their perceived abilities as supervisors. The specific factors most often identified by more than half of the participants, however, were the influence of supervisors and supervisees in their training programs.

Supervisors. All participants indicated that interactions with current and previous supervisors influenced their self-efficacy as supervisors. Ten participants reported supervisors modeling their supervision style and techniques as influential. For example, in regard to watching supervision tapes of the faculty supervisors, one participant stated that it has “been helpful for me to see the stance that they [faculty supervisors] take and the model that they use” when developing her own supervision skills. Seven participants also indicated having the space to grow as supervisors as a positive influence on their self-efficacy. One participant explained as follows:

I know people at other universities and it’s like boot camp, they [faculty supervisors] break them down and build them up in their own image like they’re gods. And I don’t feel that here. I feel like I’m able to be who I am and they’re supportive and helping me develop who I am.

In addition to the information provided during the focus groups, 11 focus group participants reiterated on their follow-up questionnaires that faculty supervisors had a positive influence on the development of their self-efficacy. For example, for one participant, “a lot of support from faculty supervisors in terms of their accessibility and willingness to answer questions” was a factor in strengthening her perception of her abilities as a counselor supervisor. Participants also noted the importance of working with their supervisees as beneficial and influential to their perceptions of self-efficacy as supervisors.

Supervisees. All participants in the focus groups discussed supervising counselors-in-training as having both direct and vicarious influences on their self-efficacy. One participant stated that having the direct experience of supervising counselors-in-training at different levels of training (e.g., pre-practicum, practicum, internship) was something that “really helped me to develop my ability as a supervisor.” In addition, one participant described a supervision session that influenced him as a supervisor: “When there are those ‘aha’ moments that either you both experience or they experience. That usually feels pretty good. So that’s when I feel the most competent, I think as a supervisor.” Further, another participant described a time when she felt competent as a supervisor: “When [the supervisees] reflect that they have taken what we’ve talked about and actually tried to implement it or it’s influenced their work, that’s when I have felt closest to competence.” In addition to working relations with supervisors and supervisees, receiving feedback was noted as an emergent theme and influential to the growth of the doctoral student supervisors.

Receiving Feedback

Of all of the emergent themes, performance feedback appeared to have the most overlap across focus groups. The authors asked participants how they felt about receiving feedback on their supervisory skills. Sub-themes emerged when participants identified receiving feedback from their supervisors, supervisees and peers as shaping to their self-efficacy beliefs as supervisors.

Supervisors. Fifteen participants discussed the process of receiving performance feedback from faculty as an important factor in their self-efficacy. Overall, participants reported receiving constructive feedback as critical to their learning, albeit with mixed reactions. One participant noted that “at the time it feels kind of crappy, but you learn something from it and you’re a better supervisor.” Some participants indicated how they valued their supervisors’ feedback and they preferred specific feedback over vague feedback. For example, as one participant explained, “I kind of just hang on her every word….it is important. I anticipate and look forward to that and am even somewhat disappointed if she kind of dances around an issue.” Constructive feedback was most preferred across all participants. In addition to the impact of receiving feedback from supervisors, participants commented on being influenced by the feedback they received from their supervisees.

Supervisees. Thirteen focus group participants reported that receiving performance evaluations from supervisees affected their sense of self-efficacy as supervisors and appeared to be beneficial to all participants. Participants indicated that they were more influenced by specific rather than general feedback, and they preferred receiving written feedback from their supervisees rather than having supervisees subjectively rate their performance with a number. One participant commented that “it’s more helpful for me when [supervisees] include written feedback versus just doing the number [rating]…something that’s more constructive.” Further, a participant described how receiving constructive feedback from supervisees influenced his self-efficacy as a supervisor:

I’d say it affects me a little bit. I’m thinking of some evaluations that I have received and some of them make me feel like I have that self-efficacy that I can do this. And then the other side, there have been some constructive comments as well, and some of those I think do influence me and help me develop.

Similar to feedback received from supervisors and supervisees, participants reiterated their preference in receiving clear and constructive feedback. Focus group participants also described receiving feedback from their peers as being influential in the development of their supervision skills.

Peers. Eleven participants shared that feedback received from peers was influential in shaping the perception of their skills and how they conducted supervision sessions. Participants described viewing videotapes of supervision sessions in group supervision and receiving feedback from peers on their taped supervision sessions as positive influences. For example, one participant stated that “there was one point in one of our classes when I’d shown a tape and I got some very… specific positive feedback [from peers] that made me feel really good, like made me feel more competent.” Another participant noted how much peers had helped her increase her comfort level in evaluating her supervisees: “I had a huge problem with evaluation when we started out….in supervision, my group really worked on that issue with me and I feel like I’m in a much better place.”

Performance feedback from faculty supervisors, supervisees, and peers was a common theme in all three focus groups and instrumental in the development of supervisory style and self-efficacy as supervisors. Constructive and specific feedback appeared to more positively influence participants’ self-efficacy than vague or unclear subjective rating scales. In addition to receiving performance feedback, another theme emerged when participants identified issues with providing supervisees’ performance evaluations.

Conducting Evaluations

Participants viewed evaluating supervisees with mixed emotions and believed that this process affected their self-efficacy beliefs as supervisors. Thirteen participants reported having difficulty providing supervisees with evaluative feedback. For example, one participant stated the following:

I had a huge problem with evaluation when we started out. It’s something I don’t like. I feel like I’m judging someone….And after, I guess, my fifth semester….I don’t feel like I’m judging them so much as it is a necessity of what we have to do, and as a gatekeeper we have to do this. And I see it more as a way of helping them grow now.

Conversely, one participant, who had experience as a supervisor before starting the doctoral counselor education program stated, “I didn’t really have too much discomfort with evaluating supervisees because of the fact that I was a previous supervisor before I got into this program.” Other participants, who either had previous experience with supervisory positions or who had been in the program for a longer period of time, confirmed this sentiment—that with more experience the anxiety-provoking feelings subsided.

All focus group participants, however, reported a lack of adequate instruction on how to conduct evaluations of supervisee performance. For example, participants indicated a lack of training on evaluating supervisees’ tapes of counseling sessions and in providing formal summative evaluations. One participant addressed how receiving more specific training in evaluating supervisees would have helped her feel more competent as a supervisor:

I felt like I had different experiences with different supervisors of how supervision was given, but I still felt like I didn’t know how to give the feedback or what all my options were, it would have just helped my confidence… to get that sort of encouragement that I’m on the right track or, so maybe more modeling specifically of how to do an evaluation and how to do a tape review.

All focus group participants raised the issue of using Likert-type questions as part of the evaluation process, specifically the subjectivity of interpretation of the scales in relation to supervisee performance and how supervisors used them differently. For example, a participant stated, “I wish there had been a little bit more concrete training in how to do an evaluation.” A second participant expanded this notion:

I would say about that scale it’s not only subjective but then our students, I think, talk to each other and then we’ve all evaluated them sometimes using the same form and given them a different number ’cause we interpret it differently…. It seems like another thing that sets us up for this weird ‘in the middle’ relationship because we’re not faculty.

Discussions about providing performance evaluations seemed to be one of the most vibrant parts of focus group discussions. Thus, it appears that having the support of influential people (e.g., supervisors and supervisees) and feedback from supervisors, supervisees and peers was helpful. Having more instruction on conducting evaluations and clarifying their role identity and expectations, however, would increase their sense of self as supervisors in the middle tier of supervision.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore what counselor education doctoral students experienced working in the middle tier of supervision and how their experiences related to their sense of self-efficacy as beginning supervisors. Data analysis revealed alignment with previous research that self-efficacy of an individual or group is influenced by extrinsic and intrinsic factors, direct and vicarious experiences, incentives, performance achievements, and verbal persuasion (Bandura, 1986), and that a person’s self-efficacy may increase from four experiential sources: mastery, modeling, social persuasion, and affective arousal (Larson, 1998). For example, participants identified factors that influence their self-efficacy as supervisors such as the direct experience of supervising counselors-in-training (mastery) as “shaping,” and how they learned vicariously from others in supervision classes. Participants also noted the positive influence of observing faculty supervision sessions (modeling) and receiving constructive feedback by supervisors, supervisees, and peers (verbal persuasion). In addition, participants described competent moments with their supervisees as empowering performance achievements, especially when they observed growth of their supervisees resulting from exchanges in their supervision sessions. Further, participants indicated social persuasion via support from their peers and future careers as counselor supervisors and counselor educators were incentives that influenced their learning experiences. Finally, participants discussed how feelings of anxiety and self-doubt (affective arousal) when giving performance evaluations to supervisees influenced their self-efficacy as supervisors.

Results from this study also support previous research on receiving constructive feedback, structural support, role ambiguity, and clear supervision goals from supervisors as influential factors on self-efficacy beliefs (Bernard & Goodyear, 2009; Nilsson & Duan, 2007; Reynolds, 2006). In addition, participants’ difficulty in conducting evaluations due to feeling judgmental and having a lack of clear instructions on evaluation methods are congruent with supervision literature (e.g., Corey, Haynes, Moulton, & Muratori, 2010; Falender & Shafranske, 2004). Finally, participants’ responses bolster previous research findings that receiving support from mentoring relationships and having trusting relationships with peers positively influence self-efficacy (Hollingsworth & Fassinger, 2002; Wong-Wylie, 2007).

Implications for Practice

The comments from participants across the three focus groups underscore the importance of receiving constructive and specific feedback from their faculty supervisors. Providing specific feedback requires that faculty supervisors employ methods of direct observation of the doctoral student’s work with supervisees (e.g., live observation, recorded sessions) rather than relying solely on self-report. Participants also wanted more information on how to effectively and consistently evaluate supervisee performance, especially those involving Likert-type questions, and how to effectively supervise master’s students who are studying in different areas of concentration (e.g., mental health, school counseling, and college counseling). Counselor educators could include modules addressing these topics before or during the time that doctoral supervisors work with master’s students, providing both information and opportunities to practice or role-play specific scenarios.

In response to questions about dealing with critical incidents in supervision, participants across groups discussed the importance of being prepared in handling remediation issues and wanting specific examples of remediation cases as well as clarity regarding their role in remediation processes. Previous research findings indicate teaching about critical incidents prior to engaging in job requirements as effective (Collins & Pieterse, 2007; Halpern, Gurevich, Schwartz, & Brazeau, 2009). As such, faculty supervisors may consider providing opportunities to role-play and share tapes of supervision sessions with master’s students in which faculty (or other doctoral students) effectively address critical incidents. In addition, faculty could share strategies with doctoral student supervisors on the design and implementation of remediation plans, responsibilities of faculty and school administrators, the extent to which doctoral student supervisors may be involved in the remediation process (e.g., no involvement, co-supervise with faculty, or full responsibility), and the ethical and legal factors that may impact the supervisors’ involvement. Participants viewed being included in the development and implementation of remediation plans for master’s supervisees as important for their development even though some participants experienced initial discomfort in evaluating supervisees. This further indicates the importance of fostering supportive working relationships that promote students’ growth and satisfaction in supervision training.

Limitations

Findings from this study are beneficial to counselor doctoral students, counselor supervisors, and supervisors in various fields. Limitations, however, exist in this study. The first is researcher perspective. The authors’ collective experiences influenced the inclusion of questions related to critical incidents and working in the middle tier of supervision. However, the first author made efforts to discern researcher bias by first examining her role as a research instrument before and throughout conducting this study, by triangulating sources, and by processing the interview protocol and analysis with peer reviewers and dissertation committee members. A second limitation is participant bias. Participants’ responses were based on their perceptions of events and recall. Situations participants experienced could have been colored or exaggerated and participants may have chosen safe responses in order to save face in front of their peers or in fear that faculty would be privy to their responses—an occurrence that may happen when using focus groups. The first author addressed this limitation by using follow-up questionnaires to provide participants an opportunity to express their views without their peers’ knowledge, and she reinforced confidentiality at the beginning of each focus group.

Recommendations for Future Research

Findings from this study suggest possible directions for future research. The first recommendation is to expand to a more diverse sample. The participants in this study were predominantly White (75%) and female (87.5%) from one region in the United States. As with all qualitative research, the findings from this study are not meant to be generalized to a wider group, and increasing the number of focus groups may offer a greater understanding as to the applicability of the current findings to doctoral student supervisors not represented in the current study. A second recommendation is to conduct a longitudinal study by following one or more cohorts of doctoral student supervisors throughout their supervision training to identify stages of growth and transition as supervisors, focusing on those factors that influence participants’ self-efficacy and supervisor development.

Conclusion

The purpose of this phenomenological study was to expand previous research on counselor supervision and to provide a view of doctoral student supervisors’ experiences as they train in a tiered supervision model. Findings revealed factors that may be associated with self-efficacy beliefs of doctoral students as they prepare to become counseling supervisors. Recommendations may assist faculty supervisors when considering training protocols and doctoral students as they develop their identities as supervisors.

References

Agnes, M. (Ed.). (2003). Webster’s new world dictionary (4th ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for creating self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. C. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 307–337). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Barnes, K. L. (2004). Applying self-efficacy theory to counselor training and supervision: A comparison of two approaches. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44, 56–69. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2004.tb01860.x

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2009). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Pearson.

Cashwell, T. H., & Dooley, K. (2001). The impact of supervision on counselor self-efficacy. The Clinical Supervisor, 20(1), 39–47. doi:10.1300/J001v20n01_03

Collins, N. M., & Pieterse, A. L. (2007). Critical incident analysis based training: An approach for developing active racial/cultural awareness. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85, 14–23. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00439.x

Corey, G., Haynes, R., Moulton, P., & Muratori, M. (2010). Clinical supervision in the helping professions: A practical guide (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Corrigan, J. D., & Schmidt, L. D. (1983). Development and validation of revisions in the

counselor rating form. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30, 64–75. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.30.1.64

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2009). 2009 CACREP accreditation manual. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Daniels, J. A., & Larson, L. M. (2001). The impact of performance feedback on counseling self-efficacy and counseling anxiety. Counselor Education and Supervision, 41, 120–130. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2001.tb01276.x

Falender, C. A., & Shafranske, E. P. (2004). Clinical supervision: A competency-based approach. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Fernando, D. M., & Hulse-Killacky, D. (2005). The relationship of supervisory styles to satisfaction with supervision and the perceived self-efficacy of master’s-level counseling students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44, 293–304. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb01757.x

Gore, P. A., Jr. (2006). Academic self-efficacy as a predictor of college outcomes: Two incremental validity studies. Journal of Career Assessment, 14(1), 92–115. doi:10.1177/ 1069072705281367

Halpern, J., Gurevich, M., Schwartz, B., & Brazeau, P. (2009). What makes an incident critical for ambulance workers? Emotional outcomes and implications for intervention. Work & Stress, 23(2), 173–189. doi:10.1080/02678370903057317

Hollingsworth, M. A., & Fassinger, R. E. (2002). The role of faculty mentors in the research

training of counseling psychology doctoral students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49, 324–330. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.49.3.324

Hughes, F. R., & Kleist, D. M. (2005). First-semester experiences of counselor education

doctoral students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 45, 97–108. doi:10.1002/ j.1556-6978.2005.tb00133.x

Hunt, B. (2011). Publishing qualitative research in counseling journals. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 296–300. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00092.x

Israelashvili, M., & Socher, P. (2007). An examination of a counselor self-efficacy scale (COSE) using an Israeli sample. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 29, 1–9. doi:10.1007/s10447-006-9019-0

Kline, W. B. (2008). Developing and submitting credible qualitative manuscripts. Counselor Education and Supervision, 47, 210–217. doi:10.1002/j.1556 6978.2008.tb00052.x

Kress, V. E., & Shoffner, M. F. (2007). Focus groups: A practical and applied research approach for counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85(2), 189–195. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00462.x

Larson, L. M. (1998). The social cognitive model of counselor training. The Counseling Psychologist, 26(2), 219–273. doi:10.1177/0011000098262002

Limberg, D., Bell, H., Super, J. T., Jacobson, L., Fox, J., DePue, M. K, . . . Lambie, G. W. (2013). Professional identity development of counselor education doctoral students: A qualitative investigation. The Professional Counselor, 3(1), 40–53.

Majcher, J., & Daniluk, J. C. (2009). The process of becoming a supervisor for students in a doctoral supervision training course. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 3, 63–71. doi:10.1037/a0014470

Merriam, S. B. (Ed.). (2002). Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Moustakas, C. E. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nilsson, J. E., & Duan, C. (2007). Experiences of prejudice, role difficulties, and counseling self-efficacy among U.S. racial and ethnic minority supervisees working with white supervisors. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 35(4), 219–229. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2007.tb00062.x

Nelson, K. W., Oliver, M., & Capps, F. (2006). Becoming a supervisor: Doctoral student perceptions of the training experience. Counselor Education and Supervision, 46, 17–31. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2006.tb00009.x

Protivnak, J. J., & Foss, L. L. (2009). An exploration of themes that influence the counselor education doctoral student experience. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48(4), 239–256. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00078.x

Rapisarda, C. A., Desmond, K. J., & Nelson, J. R. (2011). Student reflections on the journey to being a supervisor. The Clinical Supervisor, 30, 109–113. doi:10.1080/07325223.2011.564958

Reynolds, D. (2006). To what extent does performance-related feedback affect managers’ self-efficacy? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 25, 54–68. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2004.12.007

Schunk, D. H. (2004). Learning theories: An educational perspective (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Steward, R. J. (1998). Connecting counselor self-efficacy and supervisor self-efficacy: The continued search for counseling competence. The Counseling Psychologist, 26, 285–294. doi:10.1177/0011000098262004

Tang, M., Addison, K. D., LaSure-Bryant, D., Norman, R., O’Connell, W., & Stewart-Sicking, J. A. (2004). Factors that influence self-efficacy of counseling students: An exploratory study. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44, 70–80. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2004.tb01861.x

Wong-Wylie, G. (2007). Barriers and facilitators of reflective practice in counsellor education: Critical incidents from doctoral graduates. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 41(2), 59–76.

Woodside, M., Oberman, A. H., Cole, K. G., & Carruth, E. K. (2007). Learning to be a

counselor: A prepracticum point of view. Counselor Education and Supervision, 47, 14–28. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2007.tb00035.x

Appendix

Focus Group Protocol

-

- How is your program designed to provide supervision training?

- What factors influence your perceptions of your abilities as supervisors?

Prompt: colleagues, professors, equipment, schedules, age, cultural factors such as gender, ethnicity, social class, whether you have had prior or no prior experience as supervisors.

-

- How does it feel to evaluate the supervisees’ performance?

- How, if at all, do your supervisees provide you with feedback about your performance?

- How do you feel about evaluations from your supervisees?

Prompt: How, if at all, do you think or feel supervisees’ evaluations influence how you perceive your skills as a supervisor?

-

- How, if at all, do your supervisors provide you with feedback about your performance?

- How do you feel about evaluations from your faculty supervisor?

Prompt: In what ways, if any, do evaluations from your faculty supervisor influence how you perceive your skills as a supervisor?

-

- What strengths or supports do you have in your program that guide you as a supervisor?

- What barriers or obstacles do you experience as a supervisor?

- What influences do you have from outside of the program that affect how you feel in your role as a supervisor?

- How does it feel to be in the middle tier of supervision: working between a faculty supervisor and master’s-level supervisee?

Prompt: Empowered, stuck in the middle, neutral, powerless.

-

- What, if any, critical incidents have you encountered in supervision?

Prompt: Supervisee that has a client who was suicidal or it becomes clear to you that a supervisee has not developed basic skills needed to work with current clients.

- If a critical incident occurred, or would occur in the future, what procedures did you or would you follow? How comfortable do you feel in having the responsibility of dealing with critical incidents?

- If not already mentioned by participants, ask if they have been faced with a situation in which their supervisee was not performing adequately/up to program expectations. If yes, ask them to describe their role in any remediation plan that was developed. If no, ask what concerns come to mind when they think about the possibility of dealing with such a situation.

- Describe a time when you felt least competent as a supervisor.

- Describe a time when you felt the most competent as a supervisor.

- How could supervision training be improved, especially in terms of anything that could help you feel more competent as a supervisor?

Melodie H. Frick, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at Western Carolina University. Harriett L. Glosoff, NCC, is a Professor at Montclair State University. Correspondence can be addressed to Melodie H. Frick, 91 Killian Building Lane, Room 204, Cullowhee, NC, 28723, mhfrick@email.wcu.edu.

Apr 5, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 2

Mary Alice Fernandez, Melissa Short

This article offers mental health counselors a compilation of best practices and technology in the treatment of combat veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The goal is to increase counselors’ awareness of the resources available to enhance their repertoire of tools and techniques to assess, diagnose, case-conceptualize and treat the growing population of combat veterans with PTSD. The National Center for PTSD provides guidelines for diagnosing PTSD using the DSM-5. PTSD is now recognized as a trauma disorder related to an external event rather than an anxiety disorder associated with mental illness. The authors describe assessment tools and treatment strategies for PTSD validated on veteran populations. The paper also highlights new technology and mobile apps designed to assist in the treatment of combat PTSD.

Keywords: combat PTSD, trauma disorder, treatment of combat veterans, National Center for PTSD, mobile apps

Volunteering to serve one’s country during wartime is an act of heroism, and counselors working with combat veterans are in a unique position to honor these heroes. Combat veterans have offered the supreme sacrifice and some are paying a price by suffering from combat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The task of providing mental health services to a growing veteran population and their immediate family members is complicated by the lack of accessible services and the complexities of the disorder. To begin to address this challenge, Senator Jon Tester (D-MT) recently introduced legislation focused on improving access to mental health counselors by tasking the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) with recruiting more licensed professional mental health counselors (Tester, 2013).

This article offers an overview of resources available to mental health counselors to assess, case-conceptualize, diagnose and treat a growing population of combat veterans with PTSD. The goal is to increase the awareness of both beginning counselors and more experienced counselors of new therapies as well as best practices in treating combat PTSD. The compilation of resources begins with diagnostic criteria, assessment tools, and evidence-based practices, including new technologies for treating PTSD, and culminates with a list of resources available to counselors and veterans.

Diagnosing PTSD

Changes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) place PTSD under a new heading, Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders, and remove it from the DSM-4 anxiety category. This new DSM-5 categorization de-stigmatizes PTSD because it recognizes PTSD as a trauma disorder related to an external event rather than an anxiety related to mental illness (Staggs, 2014). The DSM-5 provides eight clear criteria for diagnosing PTSD, beginning with identifying a traumatic event (criterion A) and then noting behavioral symptoms related to PTSD. It organizes symptoms into four clusters: intrusions (criterion B), avoidance (criterion C), negative symptoms (criterion D), and arousal (criterion E) (American Psychological Association, 2013). In order for a client to meet the full criteria for a PTSD diagnosis, his or her symptoms must last longer than a month (criterion F), must prevent him or her from functioning well in significant area(s) of life (criterion G), and cannot be due to physical factors such as a medical condition or substance use (criterion H).

The National Center for PTSD (2014a) provides guidelines for diagnosing PTSD using the DSM-5. Criterion A (stressor) indicates that the person was exposed to at least one of the following: death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence. The person must persistently re-experience at least one of the intrusion symptoms (criterion B) of the traumatic event and one of the avoidance efforts (criterion C) of distressing trauma-related stimuli. Two negative symptoms or alterations in cognition or mood (criterion D) and two alterations in arousal and reactivity (criterion E) that began or worsened after the traumatic event must be present for a diagnosis of PTSD. Although symptoms may occur soon after the event, a person does not qualify for a PTSD diagnosis until at least six months after the traumatic event. An individual with PTSD will experience high levels of either depersonalization or derealization (National Center for PTSD, 2014a).

Nussbaum’s (2013) brief version for diagnosing PTSD begins by asking the following:

What is the worst thing that has ever happened to you? Have you ever experienced or witnessed an event in which you were seriously injured or your life was in danger, or you thought you were going to be seriously injured or endangered? (p. 90)

If the client answers in the affirmative, the counselor is to ask these questions: “Do you think about or re-experience these events? Does thinking about these experiences ever cause significant trouble with your friends or family, at work, or in another setting?” (Nussbaum, 2013, p. 90). Nussbaum (2013) provides a set of questions for each cluster and its associated symptoms to guide the process of diagnosis.

Assessment Tools

Ottati and Ferraro (2009) describe three assessment tools, validated on veteran populations, to screen for combat-related PTSD: the 17-item self-report PTSD Checklist (PCL), the 35-item self-report Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD), and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS). The PCL was recently updated to 20 items to reflect the changes in DSM-5. PCL-5 is a self-report measure that takes 5–10 minutes to complete and may be used to screen, diagnose and monitor changes during and after treatment of PTSD (Weathers et al., 2013). The M-PTSD uses a 5-point Likert scale to rate PTSD symptoms and related symptoms of substance abuse, suicidal ideation, and depression. It provides a PTSD symptom severity index with scores ranging from 35–175. The M-PTSD has not been revised since DSM-3, but may still be useful since it was normed with veteran populations (National Center for PTSD, 2014b). CAPS is a diagnostic structured interview that also measures the severity of symptoms and was recently revised to assess the DSM-5 PTSD symptoms. CAPS-5 is a 30-item questionnaire that takes 45–60 minutes to administer and yields a single score of PTSD severity (Weathers et al., 2013).

Other instruments are available to counselors for consideration. The PTSD Symptom Scale, Interview Version (PSS-I) with 17 items is a shorter clinical interview comparable to CAPS (Peterson, Luethcke, Borah, Borah, & Young-McCaughan, 2011). The PSS-I can be administered in about 20 minutes by a trained lay interviewer, and each item consists of a brief question so that an initial assessment can be made in shorter time (Peterson et al., 2011).The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) assesses differences between expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal during treatment intake and discharge (Boden et al., 2013). The ERQ assessment assists the counselor in targeting and reducing maladaptive regulation strategies within the context of PTSD treatment in order to help the veteran develop alternative coping skills (Boden et al., 2013). The Quick Test for PTSD (Q-PTSD) is useful for identifying individuals with a true disability (Morel, 2008). Q-PTSD is a time-efficient method of detecting malingering in veterans applying for disability; it may be used by the counselor as an initial assessment of the disorder (Morel, 2008).

Other useful instruments can be incorporated into a treatment plan, such as a strengths-based assessment, depression inventory, substance abuse assessment, and insomnia inventory. Seligman (2011) also recommends the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) for use with veterans. The 21-item PTGI “measures the extent to which survivors of traumatic events perceive personal benefits, including changes in perceptions of self, relationships with others, and philosophy of life accruing with their attempt to cope with trauma and its aftermath” (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996, p. 458). Seligman (2011) suggests that trauma often sets the stage for growth; a counselor may use the PTGI to facilitate veterans’ understanding of the conditions under which growth can happen.

Making a diagnosis of PTSD requires assessing symptoms and also gathering data from multiple assessments, a structured interview, and other knowledge of the client in order to make an evaluative judgment that leads to the development of a sound treatment plan (Ottati & Ferraro, 2009).

PTSD Treatment

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is unanimously endorsed as the best-practice treatment for PTSD by the VA and the Department of Defense (DOD; U.S. VA & U.S. DOD, 2010), the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (Foa, Keane, & Friedman, 2000), and the American Psychiatric Association (Ursano et al., 2010). Tramontin (2010) specifically states that the VA supports Prolonged Exposure (PE) therapy and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT).

In CPT and CBT, counselors challenge clients’ automatic thoughts connected with trauma. Through the use of written narratives in CPT, counselors target issues of safety, trust, power, control and self-esteem. Counselors also work with veterans to identify and label feelings as they work through impasses in their stories (Moran, Schmidt, & Burker, 2013). Exposure therapy is an evidence-based practice for many types of trauma including PTSD. According to Rauch, Eftekhari, and Ruzek (2012), PE therapy reduces PTSD symptoms and aids in treating comorbid issues. Rauch et al. (2012) explain that PE therapy consists of four components: psychoeducation, in vivo exposure, imaginal exposure, and emotional processing. Psychoeducation can help those suffering from trauma to understand their PTSD (Rauch et al., 2012). In vivo exposure consists of literally confronting the variables associated with the trauma (i.e., people, places and things; Rauch et al., 2012). Imaginal exposure involves reliving the memories associated with the trauma and engaging the accompanying emotions (Rauch et al., 2012). Emotional processing involves the counselor posing open-ended questions to the client in order to elicit both the emotions the client felt associated with the trauma and present emotions (Rauch et al., 2012).

Virtual reality exposure. In recent years, a new development of a virtual reality exposure therapy has surfaced. Albert “Skip” Rizzo developed a program titled “Virtual Iraq,” a virtual reality simulation designed to assist in the treatment of PTSD (Virtually Better, Inc., 2013). Rizzo developed the program after stumbling upon a video game called “Full Spectrum Warrior” that was originally created to train military service men and women. According to Rothbaum, Rizzo and Difede (2010), the current generation of military service members may be more comfortable participating in virtual reality treatment than conventional talk therapy, due to its similarity to gaming. After viewing several videos that demonstrate the Virtual Iraq system, the authors understand the connection between the exposure to trauma variables in PE and the exposure to trauma variables in virtual reality programs. Sharpless and Barber (2011) found several studies demonstrating the efficacy of virtual reality in treating veterans.

The protocol for virtual reality treatment involves veterans selecting a traumatic combat experience that relates closely to their most severe PTSD symptoms (McLay et al., 2012). Counselors create a realistic experience for the veteran by utilizing various sensory components of the virtual reality environment. Clients then use their senses and are immersed into the virtual reality world where they relive their trauma. Following the treatment, the counselor and the veteran process the material that surfaced in the exposure (McLay et al., 2012). In a study using virtual reality exposure therapy, McLay et al. (2012) found that “75% of participants experienced at least a 50% reduction in PTSD symptoms” (p. 635).

In addition to Virtual Iraq, Virtually Better, Inc. (2013) has developed other programs, including Virtual Vietnam, Afghanistan, Airports, and the World Trade Center. During a phone interview with Emilio Coirini, Director and Business Developer at Virtually Better, Inc., the interviewee stated that a soldier who suffers PTSD costs the government about $50,000 a year to treat, with the average treatment lasting 20 years. In contrast, the virtual reality system costs only about $30,000 with clinical training (E. Coirini, personal communication, November 16, 2012). At the time of the interview, there were about 70 systems installed throughout the United States, and Coirini explained that it is possible to receive grants for the cost of the system.

Animal-assisted treatment. In contrast to the relatively new use of virtual reality technology, animals have been assisting persons with disabilities for many years; there are a growing number of organizations that provide trained animals, specifically canines, to veterans who suffer from PTSD. According to Thompson (2010), in order to qualify as a service animal, the animal must undergo training to do work or perform helpful tasks. McConnell (2011) conducted a study that found that having a pet can provide meaningful social support that improves lives. One organization, Pets for Vets, provides animal companions to veterans with PTSD who are capable of caring for a pet. Pets for Vets states the following (2014):

Our goal is to help heal the emotional wounds of military veterans by pairing them with a shelter animal that is specially selected to match his or her personality. Professional animal trainers rehabilitate the animals and teach them good manners to fit into the veteran’s lifestyle. Training can also include desensitization to wheel chairs or crutches as well as recognizing panic or anxiety disorder behaviors. (para. 2)

Animals have been therapeutic partners to persons with disabilities for generations, and they are now serving wounded warriors.

Utilization of mobile phone applications. While researching other tools to help in treating PTSD, the authors discovered a few mobile applications available for both the iPhone and the Android that are well-developed, user-friendly and comprehensive. The first application, PTSD Coach (U.S. VA, 2014b), is elaborate in design, taking into account potential areas of concern for those who suffer from PTSD. The four main divisions of the application include Learn, Self-Assessment, Manage Symptoms and Find Support. The learning division of the application provides a comprehensive base and answers questions such as What is PTSD? and Who develops PTSD? In addition, the learning division includes answers regarding who should seek professional assistance and possible treatment protocols. The questions in the professional care subsection include Will it really work? and What if I am embarrassed about seeking help? The self-assessment section gives a person insight into the possibility of having PTSD. An example of an evaluative question is, “In the past month how often have you been bothered by disturbing memories, thoughts or images of the traumatic experience?” Users can track the history of their symptoms and schedule assessments to take periodically to provide a comparison of improvement or decline. When utilizing the manage symptoms option, users can select a mental state such as sadness or hopelessness, and the application will provide a suggestion to improve mood, depending on mood severity. Finally, users can set up their own support network, get support immediately or find professional care by choosing the finding support option. (The Apple phone app version may be found at https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/ptsd-coach/id430646302?mt=8, and the Android version may be found at https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=gov.va.ptsd.ptsdcoach.)

Another application, T2 Mood Tracker (The National Center for Telehealth and Technology, 2014), aids individuals in keeping track of their moods, which they can then report to their medical or mental health professional(s). The application can be used as a daily tool to track a client’s mood, keep notes regarding stressors, and chart a graph of the information provided. The initial screen asks whether the user would like to rate anxiety, depression, general well-being, head injury, post-traumatic stress, or general stress. The user selects one of the previously stated fields and is then required to rate several factors associated with the chosen field. The user can then graph results, create reports, save reports, or view notes. The application is user-friendly and simple in design, yet intricate enough to help the user and counselor in developing treatment protocols. (The Apple phone app version may be found at https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/t2-mood-tracker/id428373825?mt=8, and the Android version may be found at https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.t2.vas.)

A third application worthy of acknowledgement is the PE Coach, developed by the VA (2014a). The PE Coach requires a counselor trained in PE therapy. According to the National Center for PTSD (2014c), the PE Coach is a treatment companion that helps the client and counselor work through the PE treatment manual. The features of this application include the following: learning about PE therapy and the most common reactions to trauma, recording therapy sessions for personal use, setting reminders for homework and future therapy appointments, tracking tasks between sessions, practicing breathing exercises, and tracking PTSD symptoms. Currently, anecdotal accounts from veterans indicate that the mobile applications are helpful (U.S. DOD, American Forces Press Service, 2012). (The Apple phone app version may be found at https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/pe-coach/id507357193?mt=8, and the Android version may be found at https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=org.t2health.pe.)

Conclusion

Wendling (2008) reported results from an online survey administered to mental health practitioners after they had attended a conference called “Healing the Scars of War.” She found that most counselors did not understand military culture or appear to follow best-practice guidelines. The authors hope this paper serves to increase understanding of this critical area.

Technology makes it possible to access information about military families and resources to serve this special population. The VA has PTSD videos, training courses, and other materials available to inform counselors of the needs and unique cultural experiences of a diverse veteran population experiencing PTSD.

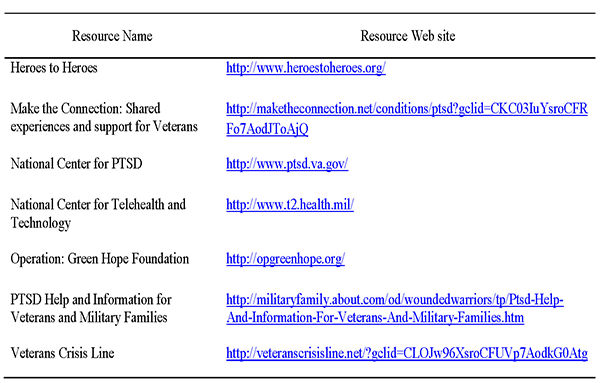

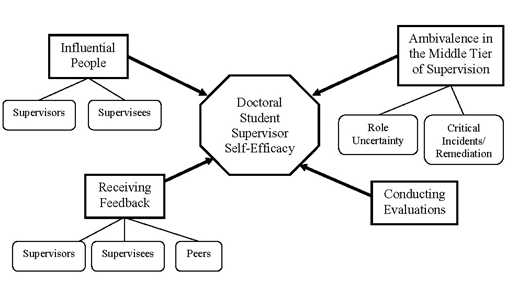

The resources identified (see Table 1) can be readily accessed by counselors and veterans to begin the therapeutic journey. We, the authors, salute the wounded warriors and continue to fight for their healing as they have fought for freedom.

Table 1

Informative Resources about Veterans and PTSD

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Boden, M. T., Westermann, S., McRae, K., Kuo, J., Alvarez, J., Kulkarni, M. R., … Bonn-Miller, M. O. (2013). Emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress disorder: A prospective investigation. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 32(3), 296–314. doi:10.1521/jscp.2013.32.3.296

Foa, E. B., Keane, T. M., & Friedman, M. J. (Eds.). (2000). Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

McConnell, A. R. (2011, July 11). Friends with benefits: Pets make us happier, healthier. Psychology Today. Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-social-self/201107/friends-benefits-pets-make-us-happier-healthier

McLay, R. N., Graap, K., Spira, J., Perlman, K., Johnston, S., Rothbaum, B. O., … Rizzo, A. (2012). Development and testing of virtual reality exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in active duty service members who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Military Medicine, 177(6), 635–642.

Moran, S., Schmidt, J., & Burker, E. J. (2013). Posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans. Journal of Rehabilitation, 79(2), 34–43.

Morel, K. R. (2008). Development of a validity scale for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence from simulated malingerers and actual disability claimants. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 19(1), 52–63. doi:10.1080/14789940701594645

National Center for PTSD. (2014a, January 3). DSM-5 criteria for PTSD. Retrieved from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/dsm5_criteria_ptsd.asp

National Center for PTSD. (2014b, January 3). Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD). Retrieved from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/mississippi-scale-m-ptsd.asp

National Center for PTSD. (2014c, January 28). Mobile app: PE coach. Retrieved from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/materials/apps/pecoach_mobileapp-public.asp

The National Center for Telehealth and Technology. (2014). T2 Mood Tracker [Mobile application software]. Available from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/t2-mood-tracker/id428373825?mt=8 or https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.t2.vas

Nussbaum, A.M. (2013). The Pocket Guide to the DSM-5 Diagnostic Exam. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Ottati, A., & Ferraro, F. R. (2009). Combat-related PTSD treatment: Indications for exercise therapy. Psychology Journal, 6(4), 184–196.

Peterson, A. L., Luethcke, C. A., Borah, E. V., Borah, A. M., & Young-McCaughan, S. (2011). Assessment and treatment of combat-related PTSD in returning war veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 18(2), 164–175. doi:10.1007/s10880-011-9238-3

Pets for Vets. (2014). Healing vets and saving pets. Retrieved from http://pets-for-vets.com

Rauch, S. A. M., Eftekhari, A., & Ruzek, J. I. (2012). Review of exposure therapy: A gold standard for PTSD treatment. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 49(6), 679–687.

Rothbaum, B. O., Rizzo, A., & Difede, J. (2010). Virtual reality exposure therapy for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1208, 126–132. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05691.x

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Free Press.

Sharpless, B. A., & Barber, J. P. (2011). A clinician’s guide to PTSD treatment for returning veterans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(1), 8–15. doi:10.1037/a0022351

Staggs, S. (2014). Symptoms & diagnosis of PTSD. Retrieved from http://psychcentral.com/lib/symptoms-and-diagnosis-of-ptsd/000158

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. doi:10.1002/jts.2490090305

Tester, J. (2013, June 13). Tester introduces comprehensive veterans’ health care legislation [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.tester.senate.gov/?p=press_release&id=2965

Thompson, M. (2010, November 22). Bringing dogs to heal. Time, 176(21), 54–57. Retrieved from http://p2v.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/p2v-time-web.pdf

Tramontin, M. (2010). Exit wounds: current issues pertaining to combat-related PTSD of relevance to the legal system. Developments in Mental Health Law, 29, 23–47.

U.S. Department of Defense, American Forces Press Service. (2012, July 31). DOD, VA release mobile app targeting post-traumatic stress [News release]. Retrieved from http://www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=117339

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2014a). PE coach [Mobile application software]. Available from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/pe-coach/id507357193?mt=8 or https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=org.t2health.pe

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2014b). PTSD coach [Mobile application software]. Available from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/ptsd-coach/id430646302?mt=8 or https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=gov.va.ptsd.ptsdcoach

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, & U.S. Department of Defense. (2010). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of post-traumatic stress. Washington, DC: Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Working Group. Retrieved from http://www.healthquality.va.gov/ptsd/cpg_PTSD-FULL-201011612.pdf

Ursano, R. J., Bell, C., Eth, S., Friedman, M., Norwood, A., Pfefferbaum, B., … Benedek, D. M. (2010). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved from http://psychiatryonline.org/pdfaccess.ashx?ResourceID=243186&PDFSource=6

Virtually Better, Inc. (2013). Virtual Iraq. Retrieved from http://www.virtuallybetter.com/virtual-iraq/