Sep 3, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 2

Rebecca A. Newgent, Kristin K. Higgins, Stephanie E. Belk, Bonni A. Nickens Behrend, Kelly A. Dunbar

Group counseling has been highlighted as one effective intervention for at-risk students, yet debate remains as to the comparable efficacy of traditional interventions versus thematic interventions. This study compared two psychosocial educational programs, the PEGS and ARK Programs, designed to help elementary school students with social skills development, problem behaviors, bullying, and self-esteem with 15 elementary-aged students. Results revealed no differences between the programs and improvement on many indicators. Implications for school counselors are presented.

Keywords: elementary students, psychosocial education, prevention programs, school counseling, traditional interventions, thematic interventions

Group work can be an effective means of counseling at-risk students. As such, the American School Counselors Association (ASCA) has endorsed group work as an important component of school counseling (ASCA, 2005). Groups can help students learn to solve problems in an efficient and effective manner and is an ideal method for meeting the needs of at-risk populations (Akos & Milsom, 2007). Group counseling allows students to develop connections while at the same time exploring factors that may affect their achievement (Kayler & Sherman, 2009). Groups are used to address such issues as social skills (Bostick & Anderson, 2009), bolstering students’ self-perceptions (Eppler, Olsen, & Hidano 2009), preventing problem behavior (Todd, Campbell, Meyer, & Horner, 2008), increasing academic success (Brigman, Webb, & Campbell, 2007), and reducing school-wide bullying (Allen, 2010). Further, Quinn, Kavale, Mathur, Rutherford, and Forness (1999) conducted a meta-analysis (35 studies) of social skills interventions used with children exhibiting problem or emotional behaviors. Results revealed several important issues. First, it appears that there is a wide range of presenting deficits in children’s social skills. Second, social skills training is widely used as a mechanism to address problem behavior in children; however, it may not be as effective at addressing problem behaviors when used in isolation. The purpose of this study is to compare the effectiveness of two psychosocial intervention programs, Psychosocial Educational Groups for Students (PEGS) and the At-Risk Kids Groups (ARK) and to assess the impact of each program. The PEGS and ARK Programs are designed to help elementary school students in the following areas: social skills development, problem behaviors, bullying, and self-esteem.

Issues Addressed in Groups

According to Berry and O’Conner (2010), social skills are a set of learned behaviors that allow for positive social interactions, such as sharing, helping, initiating and sustaining relationships. Children who enter the academic setting with problem behaviors are often the children who lack the social skills to create and maintain positive social interactions. In a recent study by Bostick and Anderson (2009), 49 third graders with social skill deficits participated in a 10-week social skills program aimed at reducing loneliness and anxiety in an academic setting. Findings revealed significant reductions in loneliness and anxiety as well as significant increases in reading scores.

Groups also can be an effective manner in addressing children with problem behavior. For example, Hudley, Graham, and Taylor (2007) studied the level of children’s aggression in relation to personal responsibility. After a series of 12 lessons related to detecting other’s intentions, externalization, and positive responses, students showed improvement in socially acceptable behavior along with a reduction in overall aggression. For additional examples also see Cotugno (2009), McCurdy, Lannie, and Barnabus (2009), and Todd, Campbell, Meyers, and Horner (2008).

Olweus (1997) defines bullying as purposeful behavior, repeated over time, including an imbalance of power. Several psychoeducational programs have been developed to address the issue of bullying in schools (Horne, Bartolomucci, & Newman-Carlson, 2003; Jenson & Dieterich, 2007; Olweus, 1991). At-risk students are at particular risk for bully-related behaviors, including both roles of victim and perpetrator (Allen, 2010). Therefore, group intervention in the schools may be a beneficial way of directly addressing bullying.

Self-esteem, also known as self-concept, is often defined as the way in which children think about themselves in relation to their attributes and abilities (Kenny & McEachern, 2009). “Part of preventing problem behaviors is increasing the self-esteem of those with problem behaviors” (Newgent, Behrend, Lounsbery, Higgins, & Lo, 2010, p. 82). There are relatively few empirical studies, however, on the effectiveness of groups and self-esteem (e.g., O’Moore & Kirkham, 2001; Whitney & Smith, 1993).

Prior Research

A paucity of research exists on addressing multiple presenting problems in children. A major implication of the Quinn et al. (1999) meta-analysis suggested that psychoeducational groups may need to address more than one problem. A study conducted by Newgent et al. (2010) examined the effectiveness of a 6-week psychosocial educational group for students that addressed social skills, problem behaviors, bullying, and self-esteem. Results showed that students with multiple presenting issues benefited from a group addressing multiple issues. Further, results showed that students with no clinically relevant presenting issues also benefited from the multi-issue group (Newgent et al., 2010). In addition, some research is suggesting that while traditional, process-oriented groups can be effective at addressing problems, thematic groups have become more prevalent, especially when there is a time constraint (Hartzler & Brownson, 2001). While the benefit of thematic groups is a more specific or more common goal it also can lack the breadth of more traditional groups.

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of two selective intervention programs (traditional vs. thematic) on measures of social skills, problem behaviors, teacher- and self-reports of peer relationships (bullying behaviors and peer victimization), self-esteem (self-worth, ability, self-satisfaction, and self-respect) and perception of self. Further, this study aimed to assess the impact of each of the intervention programs. The following research questions were tested: Is there a differential impact when comparing the PEGS Program to the ARK Program? Do the PEGS and ARK Programs have a positive impact on social skills, problem behaviors, peer relationships, and self-esteem?

Method

Participants

Eleven (n = 11) students were enrolled in the PEGS Program and four (n = 4) students were enrolled in the ARK Program. No attrition of program participants occurred. While participation was open to all students, teachers only recommended male students for both programs. Students in the PEGS Program were in the 4th grade and students in the ARK Program were in the 5th grade. In the PEGS Program five students (45%) identified as Caucasian/White, four (36%) identified as African American, one (9%) identified as Hispanic, and one (9%) identified as other. In the ARK Program one student (25%) identified as Caucasian, one student (25%) identified as African American, and two students (50%) identified as Hispanic. No students were identified as having some type of diagnosed learning, behavioral, or emotional disability.

Selective Intervention Program

One of the underlying tenants of the PEGS and ARK Programs is that students should not be labeled or stigmatized for having problems. Therefore, both programs utilized referrals that were based on underlying characteristics that lead to specific problems, not labels. Thus, students who are impulsive, depressed, dominant, lonely, easily frustrated, anxious, lack empathy, have low self-esteem, have difficulty following rules, are socially withdrawn, view violence in a positive way, have few friends, make negative attributions, have mood swings, instigate conflict, have difficulty handling conflict, or are aggressive or stressed were identified by their teachers and recommended for one of the two programs.

While both the PEGS and the ARK Program cover the same underlying psychosocial educational content, the primary difference is that the PEGS Program consists of traditional psychosocial education units while the ARK Program units are targeted toward peer victimization (i.e., bullying). Both PEGS and ARK provide a series of 6 one-half hour group sessions over the course of 6 weeks for elementary school students in grades 3–5. The six psychosocial education components of each of the intervention programs include: (a) improving social skills, (b) building and increasing self-esteem, (c) developing problem-solving skills, (d) assertiveness training, (e) enhancing stress/coping skills, and (f) prevention of mental health problems/problem behaviors. Lessons for the PEGS Program were adapted from Lively Lessons for Classroom Sessions (Sartori, 2000), More Lively Lessons for Classroom Sessions (Sartori, 2004), and the Missouri Comprehensive Guidance Programs (Frankenbert, Grandelious, Keller, & Schaaf, n.d.). These lessons focused on cooperation, encouraging students to be proud of who they are, breaking the chain of violence, handling anxiety and stress, and tolerance regarding differences. Lessons for the ARK Program were adapted from Bully Busters: A Teacher’s Manual for Helping Bullies, Victims, and Bystanders (Horne, Bartolomucci, & Newman-Carlson, 2003). These lessons focused on increasing awareness of bullying, building personal power, recognizing the bully and the victim, recommendations and interventions for helping victims, and relaxation and coping skills. Puppets were utilized in both programs to help model the lessons being taught. Worksheets related to the lessons also were utilized to help crystallize the concepts.

All recommended students participated in the one of the programs. Given class schedules, the school counselor recommended that students be assigned to one of the programs by grades. Therefore, all recommended 4th grade students were assigned to the PEGS Program and all recommended 5th grade students were assigned to the ARK Program. These assignments were done on a random basis. No control groups were utilized in this study at the school’s request. The same facilitators were used for both programs.

Instruments

Social Skills Improvement System – Teacher Form (SSiS–T). The Social Skills Improvement System – Teacher Form was developed by Gresham and Elliott (SSiS; 2008) and published by NCS Pearson, Inc. The SSiS–T is an 83-item rating scale designed specifically for teachers to use to assess children’s school-related problem behaviors and competencies. Scores reported for each of the three measurement areas are percentiles. Clinical levels for each of the three areas are as follows: social skills (≤ 16), problem behaviors (≥ 84), and academic competence (≤ 16). That is, lower scores on social skills and academic competence and higher scores on problem behaviors are considered clinically problematic. For the purposes of this study, only social skills and problem behaviors were evaluated. Cronbach alphas for social skills were .95 and .92 at pre- and post-test assessment, respectively. Cronbach alphas for problem behaviors were .86 and .89 at pre- and post-test follow-up assessment, respectively.

Social Skills Improvement System – Student Form (SSiS–S). The Social Skills Improvement System – Student Form was developed by Gresham and Elliott (SSiS; 2008) and published by NCS Pearson, Inc. The SSiS-S is a 75-item rating scale designed specifically for students aged 8–12 to use to assess their own school-related problem behaviors and competencies. Scores reported for each of the two measurement areas are percentiles. Clinical levels for each of the two areas are as follows: social skills (≤ 16) and problem behaviors (≥ 84). That is, lower scores on social skills and academic competence and higher scores on problem behaviors are considered clinically problematic. Cronbach alphas for social skills were .80 and .87 at pre- and post-test assessment, respectively. Cronbach alphas for problem behaviors were .74 and .70 at pre- and post-test assessment, respectively.

Peer Relationship Measure – Teacher Report. The Peer Relationship Measure – Teacher Report (Newgent, 2009a) was developed specifically for the PEGS and ARK Programs. It measures teachers’ perceptions about peer victimization. Nine items measure bullying behaviors and 9 items measure victimization. Items are scored as 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, and 2 = a lot, with scores ranging from 0 to 18 for each area. Scores reported for both of the measurement areas are totals. A high score indicates a high level of bullying behaviors and/or victimization; a low score indicates a low level of bully behaviors and/or victimization. Cronbach alphas for bullying behaviors were .89 and .90 at pre- and post-test assessment, respectively. Cronbach alphas for victimization were .78 and .90 at pre- and post-test assessment, respectively.

Peer Relationship Measure – Self Report. The Peer Relationship Measure – Self Report (Newgent, 2009b) was developed specifically for the PEGS and ARK Programs. It measures students’ perceptions about peer victimization. Nine items measure bullying behaviors and nine items measure victimization. Items are scored as 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, and 2 = a lot, with scores ranging from 0 to 18 for each area. Scores reported for both of the measurement areas are totals. A high score indicates a high level of bullying behaviors and/or victimization; a low score indicates a low level of bully behaviors and/or victimization. This measure is a parallel measure to the Peer Relationship Measure – Teacher Report. Cronbach alphas for bullying behaviors were .07 and .87 at pre- and post-test assessment, respectively. Cronbach alphas for victimization were .81 and .82 at pre- and post-test assessment, respectively.

Modified Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Inventory (a). The Modified Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Inventory (a) (Zimprich, Perren, & Hornung, 2005) measures an individual’s level of self-esteem (i.e., perception of self-worth, ability, self-satisfaction, and self-respect) and was completed by the students. The 10-item inventory uses a 4-point likert scale (strongly agree, agree somewhat, disagree somewhat, and strongly disagree). Five of the items are reverse coded and the score reported is the total, which ranges from 0–30. A high score indicates a high level of self-esteem; a low score indicates a low level of self-esteem. Cronbach alphas were .60 and .54 at pre- and post-test assessment, respectively.

Modified Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Inventory (b). The Modified Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Inventory (b) (Zimprich et al., 2005) measures an individual’s self-esteem (i.e., perception of self) and was completed by the students. The 4-item inventory uses a 5-point likert scale (never, seldom, sometimes, often, always). One of the items is reverse coded and the score reported is the total, which ranges from 4–20. A high score indicates a high level of self-esteem; a low score indicates a low level of self-esteem. Cronbach alphas were .59 and -1.56 at pre- and post-test assessment, respectively.

Procedure

Fifteen students were recommended by their teachers for the PEGS and ARK Programs and 15 parental consents/child assents were received. Recommending teachers completed the SSiS–T (Gresham & Elliott, 2008) and the Peer Relationship Measure – Teacher Report (Newgent, 2009a) at the start of the PEGS and ARK Programs and at two months after the conclusion of the PEGS and ARK Programs. Ideally, we would have liked an additional follow-up assessment; however, there was difficulty in securing a longer period of involvement in the assessments. Students completed the SSiS–S (Gresham & Elliott, 2008), the Peer Relationship Measure – Self Report (Newgent, 2009b), the Modified Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Inventory (a) (Zimprich et al., 2005), and the Modified Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Inventory (b) (Zimprich et al., 2005) at the start of the PEGS and ARK Programs and at two months after the conclusion of the PEGS and ARK Programs. All participating students received a certificate of completion at the conclusion of the last session.

Sessions for both programs were co-facilitated by two graduate students in the counseling and educational research programs. Both facilitators passed criminal background checks and had prior professional experience working with children who exhibit problematic behaviors. Supervision was provided to the facilitators by two counseling faculty members overseeing the programs.

Data Analytic Plan

Each student who participated in the PEGS or ARK Programs was assessed at two time points utilizing a variety of measurement instruments (see Instruments section). Pre-test scores on each of the instruments were initially analyzed using independent-samples t-tests to test the underlying assumption that participant scores between the groups were not significantly different. Next, scores were analyzed using independent-samples t-tests to assess for significant differences on the post-test assessment scores between the PEGS Program and the ARK Program participants. Finally, paired-samples t-tests, comparing pre-test to post-test assessment scores within each program, were used to assess the impact of each of the programs. Effect sizes are reported as small (d = .20), medium (d = .50), and large (d = .80) (Cohen, 1992; O’Rourke, Hatcher, & Stepanski, 2005).

Results

Between-Group Analysis

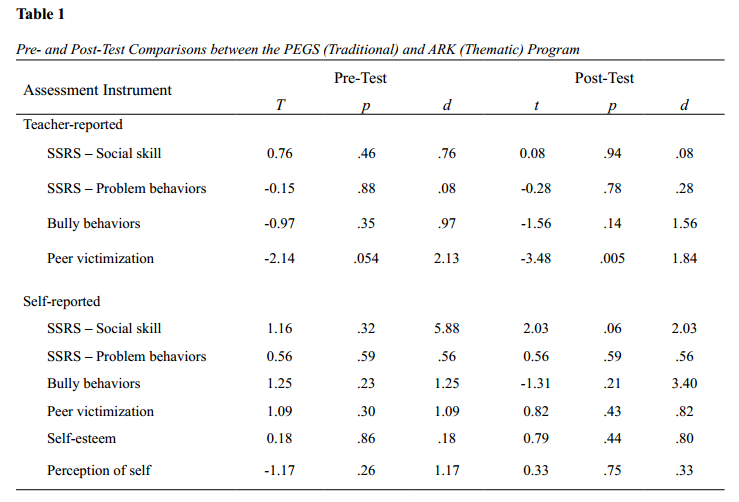

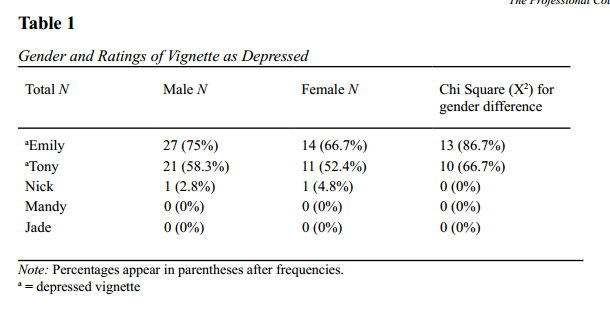

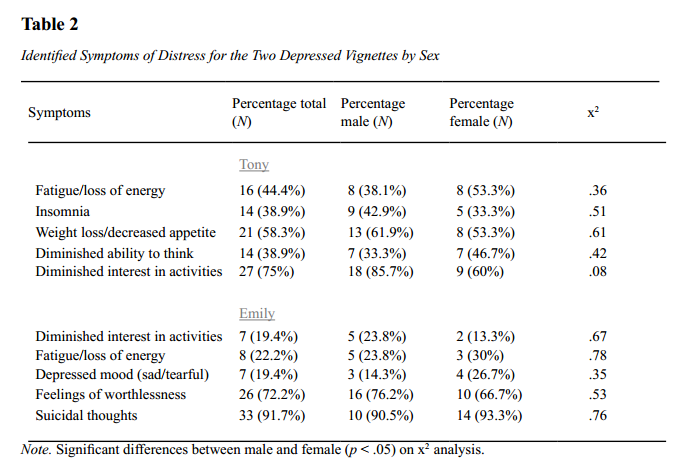

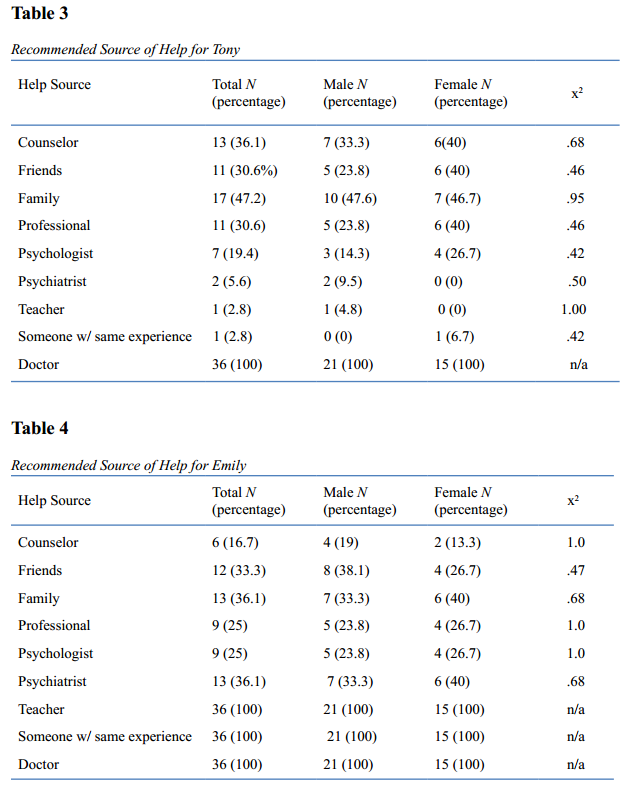

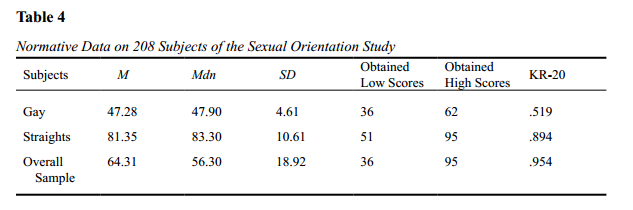

Teacher-reported measures. Results were initially analyzed using independent-samples t-tests comparing the pre-test assessment scores of the PEGS Program to the ARK Program. Statistical comparisons are displayed in Table 1. Analysis of teacher-reported social skills failed to reveal a significant difference between the two groups, t(12) = 0.76; p < .46. The effect size was computed as d = .76, which represents a large effect. Analysis of teacher-reported problem behaviors also failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(10.73) = -0.15; p < .88. The effect size was computed as d = .08, which represents a very small effect. Analysis of teacher-reported bullying behaviors failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(12) = -0.97; p < .35. The effect size was computed as d = .97, which represents a large effect. Analysis of teacher-reported peer victimization also failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(12) = -2.14; p < .054. The effect size was computed as d = 2.13, which represents a very large effect.

Results were then analyzed using independent-samples t-tests comparing the post-test assessment scores of the PEGS Program to the ARK Program. Statistical comparisons are displayed in Table 1. Analysis of teacher-reported social skills failed to reveal a significant difference between the two groups, t(12) = 0.08; p < .94. The effect size was computed as d = .08, which represents a very small effect. Analysis of teacher-reported problem behaviors also failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(12) = -0.28; p < .78. The effect size was computed as d = .28, which represents a small effect. Analysis of teacher-reported bullying behaviors failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(12) = -1.56; p < .14. The effect size was computed as d = 1.56, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of teacher-reported peer victimization revealed a significant difference between the groups, t(11.29) = -3.48; p < .005. The effect size was computed as d = 1.84, which represents a very large effect.

Self-reported measures. Results were initially analyzed using independent-samples t tests comparing the pre-test assessment scores of the PEGS Program to the ARK Program. Mean scores, significance, and effect size are displayed in Table 1. Analysis of self-reported social skills failed to reveal a significant difference between the two groups, t(3.25) = 1.16; p < .32. The effect size was computed as d = 5.88, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of self-reported problem behaviors also failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(13) = 0.56; p < .59. The effect size was computed as d = .56, which represents a medium effect. Analysis of self-reported bullying behaviors failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(13) = 1.25; p < .23. The effect size was computed as d = 1.25, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of self-reported peer victimization also failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(13) = 1.09; p < .30. The effect size was computed as d = 1.09, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of self-reported self-esteem failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(13) = 0.18; p < .86. The effect size was computed as d = .18, which represents a small effect. Analysis of self-reported perception of self also failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(13) = -1.17; p < .26. The effect size was computed as d = 1.17, which represents a very large effect.

Results were then analyzed using independent-samples t-tests comparing the post-test assessment scores of the PEGS Program to the ARK Program. Mean scores, significance, and effect size are displayed in Table 1. Analysis of self-reported social skills failed to reveal a significant difference between the two groups, t(13) = 2.03; p < .06. The effect size was computed as d = 2.03, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of self-reported problem behaviors also failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(13) = 0.56; p < .59. The effect size was computed as d = .56, which represents a medium effect. Analysis of self-reported bullying behaviors failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(13) = -1.31; p < .21. The effect size was computed as d = 3.40, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of self-reported peer victimization also failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(13) = 0.82; p < .43. The effect size was computed as d = .82, which represents a large effect. Analysis of self-reported self-esteem failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(13) = 0.79; p < .44. The effect size was computed as d = .80, which represents a large effect. Analysis of self-reported perception of self also failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(13) = 0.33; p < .75. The effect size was computed as d = .33, which represents a small to medium effect.

Within Group Analysis – PEGS

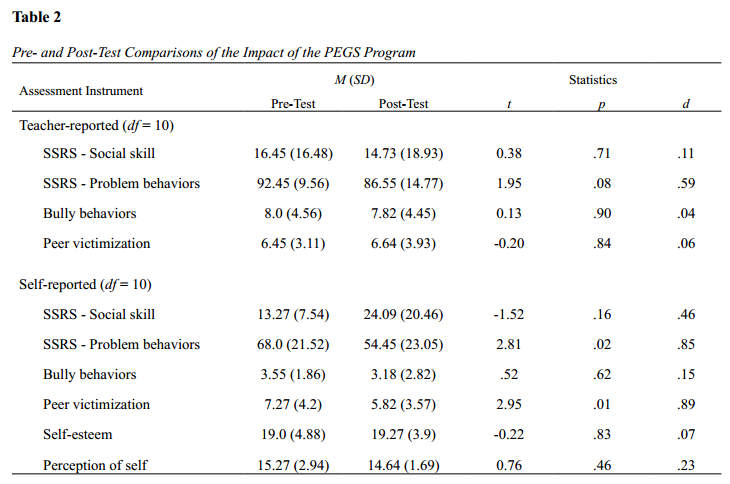

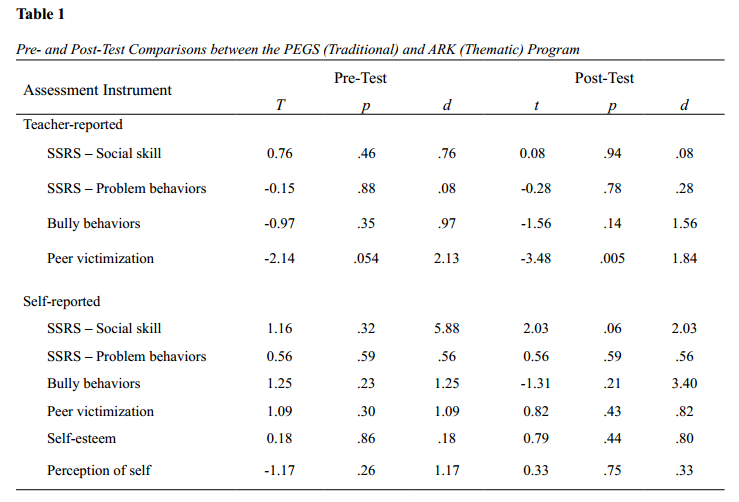

Teacher-reported measures. Results were analyzed using paired-samples t-tests comparing the pre-test assessment scores of the PEGS Program to the post-test assessment scores of the PEGS Program. Mean scores, significance, and effect size are displayed in Table 2. Analysis of teacher-reported social skills failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(10) = 0.38; p < .71. The effect size was computed as d = .11, which represents a very small effect. Analysis of teacher-reported problem behaviors also failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(10) = 1.95; p < .08. The effect size was computed as d = .59, which represents a medium effect. Analysis of teacher-reported bullying behaviors failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(10) = 0.13; p < .90. The effect size was computed as d = .04, which represents a very small effect. Analysis of teacher-reported peer victimization also failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(10) = -0.20; p < .84. The effect size was computed as d = .06, which represents a very small effect.

Self-reported measures. Results were analyzed using paired-samples t tests comparing the pre-test assessment scores of the PEGS Program to the post-test assessment scores of the PEGS Program. Mean scores, significance, and effect size are displayed in Table 2. Analysis of self-reported social skills failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and the post-test assessments, t(10) = -1.52; p < .16. The effect size was computed as d = .46, which represents a medium effect. Analysis of self-reported problem behaviors revealed a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(10) = 2.81; p < .02. The effect size was computed as d = .85, which represents a large effect. Analysis of self-reported bullying behaviors failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(10) = 0.52; p < .62. The effect size was computed as d = .15, which represents a small effect. Analysis of self-reported peer victimization revealed a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(10) = 2.95; p < .01. The effect size was computed as d = .89, which represents a large effect. Analysis of self-reported self-esteem failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(10) = -0.22; p < .83. The effect size was computed as d = .07, which represents a very small effect. Analysis of self-reported perception of self also failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(10) = 0.76; p < .46. The effect size was computed as d = .23, which represents a small effect.

Within Group Analysis – ARK

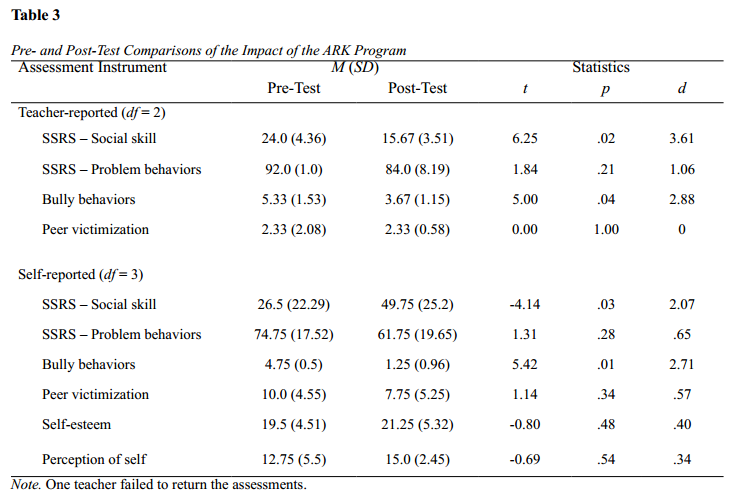

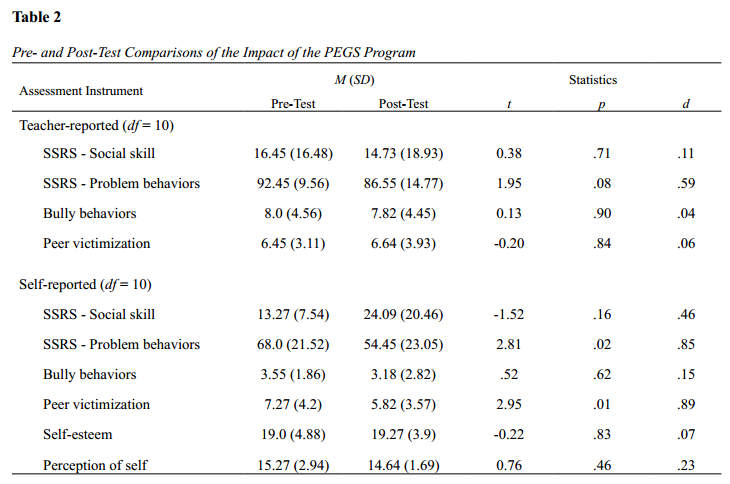

Teacher-reported measures. Results were analyzed using paired-samples t-tests comparing the pre-test assessment scores of the ARK Program to the post-test assessment scores of the ARK Program. Mean scores, significance, and effect size are displayed in Table 3. Analysis of teacher-reported social skills revealed a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(2) = 6.25; p < .02. The effect size was computed as d = 3.61, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of teacher-reported problem behaviors failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre-and post-test assessments, t(2) = 1.84; p < .21. The effect size was computed as d = 1.06, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of teacher-reported bullying behaviors revealed a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(2) = 5.00; p < .04. The effect size was computed as d = 2.88, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of teacher-reported peer victimization failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(2) = 0.00; p < 1.00. The effect size was computed as d = 0, which represents no effect.

Self-reported measures. Results were analyzed using paired-samples t-tests comparing the pre-test assessment scores of the ARK Program to the post-test assessment scores of the ARK Program. Mean scores, significance, and effect size are displayed in Table 3. Analysis of self-reported social skills revealed a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(3) = -4.14; p < .03. The effect size was computed as d = 2.07, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of self-reported problem behaviors failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(3) = 1.31; p < .28. The effect size was computed as d = .65, which represents a medium effect. Analysis of self-reported bullying behaviors revealed a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(3) = 5.42; p < .01. The effect size was computed as d = 2.71, which represents a very large effect. Analysis of self-reported peer victimization failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(3) = 1.14; p < .34. The effect size was computed as d = .57, which represents a medium effect. Analysis of self-reported self-esteem also failed to reveal a significant difference between the pre- and post-test assessments, t(3) = -0.80; p < .48. The effect size was computed as d = .40, which represents a small to medium effect. Analysis of self-reported perception of self failed to reveal a significant difference between the groups, t(3) = -0.69; p < .54. The effect size was computed as d = .34, which represents a small effect.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to compare and assess the impact of two selective intervention psychosocial education programs (traditional vs. thematic) on measures of social skills, problem behaviors, teacher- and self-reports of peer relationships (bullying behaviors and peer victimization), self-esteem (self-worth, ability, self-satisfaction, and self-respect) and perception of self in a small number of elementary school students. The PEGS and ARK Programs were designed to be short-term, non-stigmatizing programs that can easily augment current school counselor or school-based counseling services. Two groups of students were assigned to one of two programs. A discussion of the comparison between the programs and impact of each program follows.

Comparison

Findings indicated that there were no significant differences between the pre-test assessment measures when comparing the PEGS and ARK Program participants. That is, the participants in each group were comparable prior to their participation in their respective programs. Therefore, should we find significant differences between the two programs at post-test assessment, we may attribute those differences to the impact of the program. Further, there were no significant differences between the post-test assessment measures when comparing the two programs’ participants, with the exception of teacher-reported peer victimization. In other words, participants in each group were comparable after their participation in the respective programs with the exception of participants in the ARK Program having significantly lower levels of teacher-reported victimization than those in the PEGS Program. Note however that there was no difference between the pre- and the post-test assessment for ARK participants on this measure and only a non-significant increase for PEGS participants.

While these results indicate that the implementation of thematic programming directed at peer harassment does not have a significantly greater positive impact on students than traditional programming directed at students who show more generalized problems, there were some large effects (d ≥ .80) between the groups. This may indicate that there may have been some differences between the participants of the two programs, although not statistically significant.

PEGS

Findings indicated that there was significant improvement on self-reported problem behaviors and peer victimization when comparing the pre- and post-test assessments for the PEGS Program participants. In other words, students reported fewer problem behaviors and a decrease in victimization by their peers. While not significant, improvement also was found for teacher-reported problem behaviors and bully behaviors and self-reported social skills, bully behaviors, and self-esteem.

ARK

Findings indicated that there was significant improvement on teacher-reported bully behavior and on self-reported social skills and bully behaviors. In other words, students reported increased social skills and both teachers and students reported a decrease in victimization. Additionally, meaningful improvements (d ≥ .80) were found on teacher-reported problem behaviors. That is, teachers noted fewer problem behaviors in students after their participation in the ARK Program.

Conclusions

Finding effective programming that can positively impact at-risk students can be difficult. Further complicating the issue is the onslaught of thematic programming targeting specific groups of at-risk students (Hartzler & Brownson, 2001). While targeted programming can be beneficial to a select group of students it may exclude other students who can benefit but may not have the same “label.” This study showed that the more traditional group (i.e., PEGS) was equally effective as the more thematic group (i.e, ARK).

Limitations and Future Directions

There were several limitations to this study. First, we were limited to working within the parameters the school established. That is, we were limited to 4th and 5th grade males only and we were limited to providing services during their respective lunch periods. It may have been beneficial to have both genders in each group as well as a mix of grades. Second, group sizes were small. While larger group sizes would result in a greater ability to detect a statistically significant difference if one exists, larger group sizes also can result in reduced effectiveness. Third, we were unable to have a no-treatment group. The use of a control group may have resulted in a more robust study. Finally, the unequal group sizes may have impacted the comparison of the two groups. We attempted to adjust for this by using the Satterthwaite method when the equality of variances was significantly different (O’Rourke et al., 2005).

Implications

There are several implications for school and school-based counselors. First, it would be important in program management if school and school-based counselors are made aware that traditional psychoeducational groups are similarly effective to thematic psychoeducational groups. With this information they can make more informed decisions about the type of groups they implement as well as the type of intervention programs they offer and purchase. If the results of this study hold true for other groups of students and other schools, school and school-based counselors who choose to utilize more traditional programming would be able to provide these services to a broader range of students, consistent with the ASCA Model (ASCA, 2005), and not limit it to a select group of students targeted for a specific issue. Additionally, the purchase of thematic intervention programs can be costly given that the use is limited to a smaller number of students and several different types of programs are needed to address students with differing issues.

Second, the PEGS Program is an empirically supported program (see Newgent et al., 2010). It is a short-term, inexpensive, and non-intrusive program that can positively impact students with a variety of underlying issues. School and school-based counselors can easily augment their services with the implementation of this program. School administrators may be more supportive of a program that is both cost effective and would not hinder counselors from fulfilling other duties. The ever changing demands on school and school-based counselors will most likely continue. Counselors need effective tools that they can use to help students address problems, increase self-esteem, improve social skills, and decrease peer victimization.

References

Akos, P., & Milsom, A. (2007). Introduction to special issue: Group work in K-12 schools. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 32, 5–8. doi:10.1080/01933920600977440

Allen, K. P. (2010). A bullying intervention system: Reducing risk and creating support for aggressive students. Preventing School Failure, 54, 199–209.doi:10.1080/10459880903496289

American School Counselor Association. (2005). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Berry, D., & O’Conner, E. (2010). Behavioral risk, teacher-child relationships, and social skill development across middle childhood: A child-by-environment analysis of change. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2009.05.001

Bostick, D., & Anderson, R. (2009). Evaluating a small-group counseling program-A model for program planning and improvement in the elementary setting. Professional School Counseling, 12, 428–433.

Brigman, G. A., Webb, L. D., & Campbell, C. (2007). Building skills for school success: Improving the academic and social competence of students. Professional School Counselor, 10, 279–288.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Cotugno, A. J. (2009). Social competence and social skills training and intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1268–1277. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0741-4

Eppler, C., Olsen, J. A., & Hidano, L. (2009). Using stories in elementary school counseling: Brief, narrative techniques. Professional School Counseling, 12, 387–391.

Frankenbert, J., Grandelious, M., Keller, K., & Schaaf, P. (n.d.). STAR problem solving model. Missouri Comprehensive Guidance Programs. Retrieved from http://missouricareereducation.org

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (2008). Social Skills Improvement System. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson.

Hartzler, B., & Brownson, C. (2001). The utility of change models in the design and delivery of thematic group interventions: Applications to a self-defeating behaviors group. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5(3), 191–199. doi:10.1037/1089-2699.5.3.191

Horne, A. M., Bartolomucci, C. L., & Newman-Carlson, D. (2003). Bully busters: A teacher’s manual for helping bullies, victims, and bystanders. Champaign, IL: McNaughton & Gunn.

Hudley, C., Graham, S., & Taylor, A. (2007). Reducing aggressive behavior and increasing motivation in school: The evolution of an intervention to strengthen school adjustment. Educational Psychologist, 42, 251–260. doi:10.1080/00461520701621095

Jenson, J. M., & Dieterich, W. A. (2007). Effects of a skills-based prevention program on bullying and bully victimization among elementary school children. Prevention Science, 8, 285–296. doi:10.1007/s11121-007-0076-3

Kayler, H., & Sherman, J. (2009). At-risk ninth-grade students: A psychoeducational group approach to increase study skills and grade point averages. Professional School Counseling, 12, 434–439.

Kenny, M. C., & McEachern, A. (2009). Children’s self concept: A multicultural comparison. Professional School Counseling, 12(3), 207–212.

McCurdy, B. L, Lannie, A. L., & Barnabas, E. (2009). Reducing disruptive behavior in an urban school cafeteria: An extension of the Good Behavior Game. Journal of School Psychology, 47, 39–54. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2008.09.003

Newgent, R. A. (2009a). The Peer Relationship Measure – Teacher Report. Unpublished Assessment, University of Arkansas at Fayetteville.

Newgent, R. A. (2009b). The Peer Relationship Measure – Self Report. Unpublished Assessment, University of Arkansas at Fayetteville.

Newgent, R. A., Behrend, B. A., Lounsbery, K. L., Higgins, K. K., & Lo, W. J. (2010). Psychosocial educational groups for students (PEGS): An evaluation of the treatment effectiveness of a school-based behavioral intervention program. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 1, 80–84. doi:10.1177/215037810373919

Olweus, D. (1991). Bully/victim problems among school children: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. In D. Pepler & K. Rubin (Eds.), The development and treatment of childhood aggression (pp. 411–448). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. doi:10.01111/j.1467-9507.1995.tb00066.x

Olweus, D. (1997). Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and interventions. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 12, 495–510. Retrieved from http://ispa.pt/ejpe/

O’Moore, M., & Kirkham, C. (2001). Self-esteem and its relationship to bullying behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 27, 269–283. doi:10.1002/ab.1010

O’Rourke, N., Hatcher, L., & Stepanski, E. J. (2005). A step-by-step approach to using SAS for univariate & multivariate statistics (2nd ed.). Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Quinn, M. M., Kavale, K. A., Mathur, S. R., Rutherford, R. B., Jr., & Forness, S. R. (1999). A meta-analysis of social skills interventions for students with emotional or behavioral disorders. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders, 7(1), 54.

Sartori, R. S. (2000). Lively lessons for classroom sessions. Warminster, PA: MAR-CO Products.

Sartori, R. S. (2004). More lively lessons for classroom sessions. Warminster, PA: MAR-CO Products.

Todd, A. W., Campbell, A. L., Meyer, G. G., & Horner, R. H. (2008). The effects of a targeted intervention to reduce problem behaviors. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 10, 46–55. doi:10.1177/10983007073113639

Whitney, I., & Smith, P. K. (1993). A survey of the nature and extent of bullying in junior/middle and secondary schools. Education Resources, 35, 3–25.

Zimprich, D., Perren, S., & Hornung, R. (2005). A two-level confirmatory factor analysis of a modified Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65, 465–481. doi:10.1177/00131644042724

Rebecca A. Newgent, NCC, is a Licensed Professional Clinical Counselor with Supervision Designation in Ohio, a Licensed Professional Counselor with Supervision Specialization in Arkansas, and Professor and Chairperson of the Department of Counselor Education at Western Illinois University – Quad Cities. Kristin K. Higgins is a Licensed Professional Counselor with Supervision Specialization in Arkansas and an Assistant Professor of School Counseling in the Counselor Education Program at the University of Arkansas. Stephanie E. Belk is a certified school counselor in the state of Arkansas and a doctoral student in the Counselor Education Program at the University of Arkansas. Kelly A. Dunbar, NCC, is a Licensed Professional Counselor in Oklahoma, a doctoral candidate in the Counselor Education Program at the University of Arkansas, and is an Assistant Professor of Counseling and Psychology at Northeastern State University. Bonni A. Nickens Behrend has a Master of Science degree in Education Statistics and Research Methods and is currently a master’s student in the Counselor Education Program and a Senior Graduate Research Assistant at the National Office for Research on Measurement and Evaluation Systems at the University of Arkansas. This research was supported in part by a grant from Mental Health America in Northwest Arkansas. Correspondence can be addressed to Rebecca A. Newgent, Department of Counselor Education, 3561 60th Street, Moline, IL, 61265, ra-newgent@wiu.edu.

Sep 3, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

Chiharu Hensley

Raising a child with special needs exacerbates the inherent challenges of parenting. Although the needs of children with special needs are addressed frequently in the literature, the needs of the parents of children with special needs are often neglected. In order to offer effective and useful services for parents of children with special needs, this article examines the types and nature of support services used by the parents of children with special needs and the effectiveness of those support services in reducing the parents’ stress levels and/or increasing their coping skills. Seventy-four parents of special needs children were assessed and results revealed that low-cost services, particularly those that resulted in mutual support, were a significant priority among parents. The article concludes with a discussion of clinical implications and needed directions for future research.

Keywords: parenting, children, special needs, support services, counseling

Parenting involves much effort and countless responsibilities. Child rearing can be one of the most challenging tasks with which a person is confronted. Raising a child with special needs intensifies the challenge significantly. However, although the needs of children with special needs are addressed frequently in professional literature and in the media, the needs of parents of children with special needs are addressed far less often. In order to offer effective and useful services for parents of children with special needs, their experiences with common issues and concerns and how their needs can be met must be investigated and understood because such information is essential to enable parents to feel empowered in raising their children with special needs.

Parents of children with special needs often experience high levels of stress from both internal and external factors. For example, a study conducted by Heiman (2002) revealed that 84.4% of the participants who had children with various special needs experienced feelings including “depression, anger, shock, denial, fear, self-blame, guilt, sorrow, grief, confusion, despair, [and/or] hostility” at the time of their children’s first diagnoses. Barnett, Kaplan-Estrin, and Fialka (2003) reported a study of parents of children who were mildly or moderately impaired that showed about half of the parents were still experiencing negative responses to their children’s diagnoses two or more years after the initial diagnosis.

In addition, parents of children with special needs may suffer being stereotyped by others. For example, Goddard, Lehr, and Lapadat (2000) used focus groups to collect individual narratives from parents of children with special needs. They found that, more than the parents’ guilt or the condition of the child, being perceived as a victim of a tragedy and the sole advocate for the child as well as a lack of understanding from others, including professionals, contributes to parental stress. Financial concern is another external factor which contributes to high stress levels in parents raising children with special needs. Looman, O’Conner-Von, Ferski, and Hildenbrand (2009) found that the severity of a child’s special needs increased the odds of financial burden experienced by the family. Clearly, there are a variety of both internal and external stressors, and accompanying emotional reactions, with which parents of children with special needs are confronted. Therefore, providing services to reduce the stress and negative feelings to minimum levels would lead to better quality of life for the parents of children with special needs.

Given the relative lack of attention to the support service needs of parents raising children with special needs, the purpose of this study was to conduct an exploratory investigation of the types of services used by parents of children with special needs and the effectiveness of those services for reducing parents’ stress levels and increasing their coping skills.

Four primary research questions were addressed in this study:

1. What are the types of services used by parents of children with special needs?

2. How effective are services in reducing stress levels of such parents?

3. How effective are services in increasing the coping skills of parents?

4. What are some of the needs of parents which may be met by counseling services?

Method

There were two major parts to this research. The first involved distribution of a survey to parents of children with special needs and the second involved an extensive interview with a representative parent of a child with special needs. In the first part of the study a survey was used to collect data for approximately one year. Potential respondents included parents and/or primary caregivers of preschool or school-age children with special needs who resided in a Midwestern state. No restriction was placed on the potential respondents based on the type or number of special needs their child had. Participants were recruited through contact with organizations for families of children with special needs (e.g., local associations for learning disabilities, pervasive developmental disabilities, and physical disabilities) and snowball sampling with assistance of professionals at local public schools who work with children with special needs and their parents. An online survey, the primary means of data collection, was created using a commercial website (www.surveymonkey.com), and potential respondents were directed to the survey webpage from either the websites of the organizations or by typing in the website address found on a distributed survey invitation flyer. A paper version of the survey was prepared for participants from a university clinic for speech and hearing.

The second part of the study involved an individual follow-up interview. Initially, the intent was to garner enough participants for a focus group activity. Unfortunately, however, of all the survey respondents, only one expressed interest in participating in a focus group. Therefore, this respondent was selected and interviewed in order to explore the stressors, challenges, and supports available for the parents in greater depth. The interview was audio-taped and transcribed by the investigator.

Results

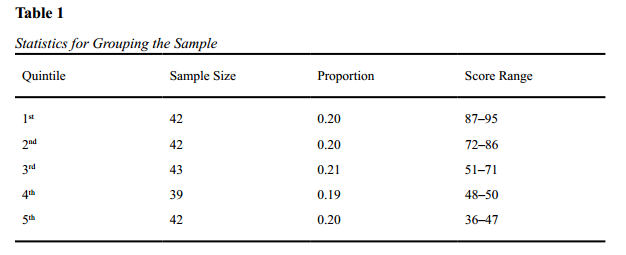

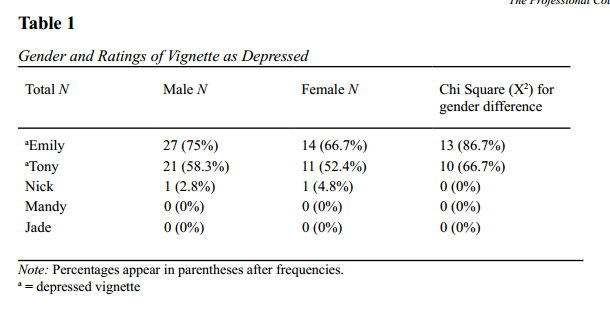

There were a total of 74 respondents. Among the respondents, 70 (94.6%) completed the survey online and 4 (5.4%) completed the paper form of the survey. Selected survey items and the resultant data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Selected Survey Items and the Resultant Data

Survey Items No. of Responses % Responses

Items for all the respondents (N = 74)

How would you rate your degree of stress on the following scale?

In the last month?

Very low 0 0.0

Low 8 10.8

Moderate 22 29.7

High 33 44.6

Very High 9 12.2

In the last year?

Very low 0 0.0

Low 5 6.8

Moderate 23 31.1

High 24 32.4

Very High 21 28.4

What would be the ratio of each factor that might be contributing to your stress level?

Raising a child(ren) with special needs

About 1–25% 9 12.2

About 26–40% 15 20.3

About 41–60% 15 20.3

About 61–80% 23 31.1

About 81–100% 11 14.9

Financial concerns

About 1–25% 15 20.3

About 26–40% 20 27.0

About 41–60% 12 16.2

About 61–80% 7 9.5

About 81–100% 15 20.3

Have you sought professional services (i.e., therapies) in dealing with your stress of raising a child(ren) with special needs?

Yes 30 40.5

No 43 58.1

If you answered No to the previous question, what was (were) your reason(s) for not seeking professional services (i.e., therapies)? (n = 43)

Unable to afford the service 5 11.6

Schedule conflict 7 16.3

Did not know about any service available 7 16.3

Unable to find a service that seemed

helpful for your needs 12 27.9

Counseling as a category of received service (n=30)

Type of service you have received:

Individual counseling 22 73.3

Couples counseling 3 10.0

Family counseling 7 23.3

How helpful was the service for dealing with your stress?

Very helpful 7 23.3

Somewhat helpful 12 40.0

Neutral 2 6.7

Somewhat unhelpful 2 6.7

Very unhelpful 3 10.0

Compared with your stress level before receiving service, how much has it changed after

receiving service?

Not changed at all 2 6.7

Greatly reduced 12 40.0

Somewhat reduced 7 23.3

Unsure 2 6.7

Somewhat increased 2 6.7

Greatly increased 2 6.7

Compared with your outlook on raising your child(ren) with special needs before receiving service, how much has it changed after receiving service?

Not changed at all 3 10.0

Greatly more optimistic 12 40.0

Somewhat more optimistic 4 13.3

Unsure 6 20.0

Somewhat more pessimistic 1 3.3

Greatly pessimistic 0 0.0

Group as a category of received service (n=16)

Group counseling 2 12.5

Support group 14 87.5

How helpful was the service for dealing with your stress?

Very helpful 6 37.5

Somewhat helpful 8 50.0

Neutral 1 6.3

Somewhat unhelpful 0 0.0

Very unhelpful 1 6.3

Compared with your stress level before receiving service, how much has it changed after receiving service?

Not changed at all 0 0.0

Greatly reduced 10 62.5

Somewhat reduced 3 18.8

Unsure 1 6.3

Somewhat increased 2 12.5

Greatly increased 0 0.0

Compared with your outlook on raising your child(ren) with special needs before receiving service, how much has it changed after receiving service?

Not changed at all 1 6.3

Greatly more optimistic 8 50.0

Somewhat more optimistic 2 12.5

Unsure 3 18.8

Somewhat more pessimistic 1 6.3

Greatly more pessimistic 0 0.0

Items for the respondents who sought a professional service(s) in the past for dealing

with their stress of raising their children with special needs (n=30)

What have you gained from receiving service(s)?

Peer support 8 26.7

Professional support 7 23.3

Network 10 33.3

Specific knowledge about the

child(ren)’s disability(ies) 14 46.7

Specific skills for dealing with

the child(ren)’s needs 13 43.3

What are some of the factors that you consider when choosing a service?

Cost (including transportation

and session fees) 20 66.7

Schedule/frequency 21 70.0

Format (e.g., individual vs. group vs.

psychoeducational vs. counseling) 16 53.3

How likely are you to seek an additional service(s) in the future?

Very likely 9 30.0

Likely 8 26.7

Unsure 6 20.0

Unlikely 1 3.3

Very unlikely 0 0.0

If you were to receive an additional service(s), what would be the most likely format/venue?

Individual counseling 15 50.0

Couples counseling 4 13.3

Family counseling 8 26.7

Group counseling 1 3.3

Support group 13 43.3

Parenting training individual sessions 4 13.3

Parenting training group sessions 6 20.0

Individual psychoeducational sessions 0 0.0

Psychoeducational group sessions 3 10.0

Coping skills—individual sessions 5 16.7

Coping skills—group sessions 3 10.0

Stress management—individual sessions 8 26.7

Stress management—group sessions 4 13.3

Note. Some of the items allowed multiple answers by a single respondent. Percentage of respondents for each item was measured based on the number of respondents corresponding to specific items.

Some of the 74 respondents did not provide responses for all items. The respondent group included 67 females (90.5%) and 63 (85.1%) participants who identified themselves as Caucasian/White. Thirty-five respondents (47.3%) were between ages 31 and 40, and 58 (78.4%) were married. Fifty-nine of the respondents (79.7%) had one child with special needs and 31 (41.9 %) reported the child’s disability as moderate.

In regard to stress levels, 33 respondents (44.6%) indicated that they had experienced a high degree of stress in the past month, and 45 (60.8%) indicated that they had experienced either a high or very high degree of stress in the past year. Twenty-three respondents (31.1%) indicated that raising their child with special needs contributed to about 61–80% of their total stress level, and 20 (27.0%) indicated that their financial concerns contributed to about 26–40% of their total stress level. In regard to help seeking, 45 (60.8%) indicated that they had never sought professional services (e.g., various possible therapies) to cope with the stress of raising a child with special needs. The most frequently cited (n = 12, 27.9%) reason for not seeking support services was that they were unable to find services that they perceived to be helpful for their needs.

Among the 30 respondents who had sought professional services, 22 (73.3%) indicated that they had sought individual counseling (which also was the most used type of service). The second most used type of service was support groups, in which 14 respondents (46.7%) indicated that they had joined or were current members of a support group. Among those who had received individual, couple, family, or any combination of counseling, 19 (73.1%) indicated that their stress levels were reduced to some or a great extent after receiving such service(s) and 16 (61.6%) responded that their outlook on raising their child with special needs became somewhat or greatly more optimistic.

Specifically, among the 16 (53.3%) who had received either group counseling, participated in support groups, or both, 13 (81.3%) indicated that their stress levels were somewhat or greatly reduced and 10 (62.5%) indicated that their outlook on raising their child) with special needs became somewhat or greatly more optimistic. Finally, 14 (46.7%) responded that they had gained specific knowledge about the child’s disability from receiving the services and 13 (43.3%) responded that they had gained specific skills for coping with the child’s needs.

Although the respondents in this latter subgroup had participated in a wide variety of support services, it appears that most were psychoeducational in nature. Seventeen respondents (56.7%) also reported that they were either likely or very likely to seek additional services in the future. The three most selected types of services that these respondents would most likely seek were individual counseling (n=15, 50.0%), support groups (n=13, 43.3%), and family counseling (n=8, 26.7%). Session schedule and frequency, cost (including transportation and session fees), and format of the service were all important factors considered in use of support services.

The second part of the study was an interview with the mother of a son with cerebral palsy in order to gather information about personal experiences, particularly those contributing to her level of stress. The interview was conducted at a house close to the hospital to which she periodically brought her son for treatment. At the time of the interview, Amy (a pseudonym), the mother, was 39 years old, and Michael (a pseudonym), her son, was two years old. Amy was Caucasian, between 31 and 40 years old, married, and had one child with special needs; therefore, she was “typical” of the majority of the respondents to the survey. Specific interview questions were not prepared in advance. Rather, Amy was asked to convey her most important and/or strongest experiences and emotions as a mother of a child with special needs.

A wide variety of issues were discussed during the interview, but the most pressing issue mentioned by Amy was the lack of available resources for parents of children with special needs. Amy related that large cities might have many resources available, “but especially not my little small town—the resources are so limited.” She talked about how in attempting to acquire information and resources to aid in Michael’s care, she had asked many different people. Importantly, she did considerable research on her own, primarily using the Internet. She felt that many, or perhaps most professionals did not know more than she did, regardless of their formal education and training. She gave the example of having told one of Michael’s doctors about Euro-Pēds, a facility specializing in physical therapy for children with cerebral palsy and other neuromuscular disorders. The doctor did not know about this resource. Amy also related how shocked she was when a receptionist at a local mental health facility was not aware of a “respite” fund provided by the facility. She expressed that it was “disheartening that these people are supposed to guide me, and they just couldn’t.” Then she went on to describe a situation in which parents of children with special needs could not obtain the service they wanted because they did not use the technical term:

I was told that there were even situations where people who aren’t articulate would call and say, ‘I need a

babysitter.’ And they say, ‘We don’t do babysitting services.’ Click. Because they didn’t say ‘respite,’ they were turned away…. It’s their job to be in tune with, maybe there’s something I’m not getting here. Let me figure out what’s wrong with this person that’s calling my mental health facility.

Amy was often disappointed in seeking resources and help, probably because of the lack of understanding and education among professionals.

Amy lamented that resources external to the family should not cause more stress because parents of children with special needs already are overwhelmed by feelings of guilt, helplessness and stress. She believed that Michael was not the cause of her issues, but rather that the actual problems were the by-products of his having a disability:

It’s not always directly related to the child, but all the side effects that how they affect you… A lot of it is just the overwhelming feeling that sometimes you wake up in the morning and say, ‘I can’t believe that he has so many problems.’ And you feel sorry for him, and you feel stressed out about it.

Amy also felt guilty about not being able to spend as much time as she would have liked with her other two children; the demands of Michael’s situation dominated all her plans. Amy had tried to be with her other children whenever she could, but still felt that she was not doing enough for them. Thus, she believed that Michael’s disability affected not only her, but also everyone else in the family. Amy also felt tremendous pressure when talking to Michael’s doctors:

Michael’s doctors say, ‘We don’t know if he can ever walk. But we don’t know if he won’t. It’s gonna be up to you, Mom. It’s gonna be, if he’s got the potential to do it. You’re the one that’s gonna push him…’It’s a lot of pressure and I don’t think that these doctors meant to give me that unneeded pressure… But I work very hard to push Michael, you know, everyday. But it scares me. It scares me that, ‘Am I pushing him enough? Am I pushing him too hard?’

Obviously Amy (and other parents of children with special needs like her) suffers from high levels of stress from both internal and external factors. To Amy, taking care of Michael was like “not knowing how to swim and you get thrown into a pool with another person who doesn’t know how to swim.” When Michael was born, Amy had to teach herself how to raise a child with special needs because “these children don’t come with an instruction manual…or a book of resources.” She believed that knowledge about Michael’s disability would be particularly important in order for her to take care of him properly and effectively. She also was aware that the process of accepting her son’s disability and learning how to take care of a child with special needs could be “a nightmare for some people,” because “even someone with formal medical training struggles with these children.” Amy related that she thought a support group to provide opportunities for the parents of children with special needs to discuss and share experiences and feelings would be beneficial. She also believed that inviting a professional such as a social worker to the group who could help the parents fill out paperwork for requesting funds and other assistance would be beneficial because many parents of children with special needs struggle with understanding and completing formal documents properly. At the end of the interview, Amy indicated that she felt like she was contributing at least in a small way to improving the lives of parents of children with special needs by participating in the research and that the interview was helpful in reducing her stress.

Discussion

This preliminary research was conducted to gather data, collect descriptive personal information, and, from the data, suggest future practices for gaining understanding of the unique needs of parents of children with special needs. Suggested in the results of this exploratory study, is that counseling services for parents of children with special needs are both warranted and needed. The format of such services likely should be group counseling because of lower cost and potential for mutual support among group members. Such group counseling sessions should be in part psychoeducational and in part intended to foster support to meet the goals of knowledge and skill acquisition for parenting children with special needs and sharing personal experiences with others. Individual and/or family counseling might be used as a follow-up service, especially for parents or families of children with special needs who appear to need intensive care. Finally, parents of children with special needs should be able to choose how they would like to interact, such as by phone, home visit, or face-to-face because they often struggle with finding child care for when they are away from home. Having support group meetings at each other’s homes also can be an option so that parents can take turns watching children during meetings.

Limitations of this study included a small number of male participants. Whether more responses from fathers would have changed the results is only a matter of speculation. Thus, future research that includes significantly more input from fathers of children with special needs is needed. Also, to be noted is that some participants reported confusion about terms such as psychoeducation, which may have influenced their responses. Therefore, future research should identify specific services rather than the categories of services. Any online survey is limited to those who have access to the Internet and are comfortable using computers. Future studies can overcome this limitation to a great extent by incorporating multiple methods involving several types of data collection. Finally, the case interview was perhaps the most valuable part of the study in terms of revealing the reality and challenges faced by parents of children with special needs. Thus, qualitative, phenomenological research also would be beneficial, especially for understanding the unique and complex concerns of parents of children with special needs.

References

Barnett, D., Clements, M., Kaplan-Estrin, M., & Fialka, J. (2003). Building new dreams: Supporting parents’ adaptation to their child with special needs. Infants and Young Children, 16, 184–200.

Ergüner-Tekinalp, B., & Akkök, F. (2004). The effects of a coping skills training program on the coping skills, hopelessness, and stress levels of mothers of children with autism. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 26, 257–269.

Goddard, J. A., Lehr, R., & Lapadat, J. C. (2000). Parents of children with disabilities: Telling a different story. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 34, 273–289.

Heiman, T. (2002). Parents of children with disabilities: Resilience, coping, and future expectations. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 14, 159–171.

Looman, W. S., O’Conner-Von, S. K., Ferski, G. J., & Hildenbrand, D. A. (2009). Financial and employment problems in families of children with special health care needs: Implications for research and practice. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 23, 117–125.

Chiharu Hensley, NCC, is a professional counselor in Nagasaki, Japan. The author thanks Dr. Devika Dibya Choudhuri for generously and patiently guiding me through the entire process of the current study while I was a Master’s counseling student at Eastern Michigan University, and those who willingly participated in the study. Correspondence can be addressed to Chiharu Hensley, 9-1-403 Manabino 2-chome, Nagayo-cho, Nishisonogi County, Nagasaki, Japan, 851-2130, chiharu.hensley@gmail.com.

Sep 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 3

Sachin Jain, Santiago Silva

One of the major flaws in current psychological tests is the belief that a prediction/diagnosis can be made that would tell an individual whether he is heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual. What is needed within the profession, however, is an assessment that has the sensitivity to help clients explore their sexual orientation. A pilot 100-item Sexual Orientation Scale was developed after interviewing 30 self-identified gay men who considered themselves happy/satisfied. The items summarized the thoughts and feelings of these 30 men during the discovery process and ultimate acceptance of their sexual orientation. The scale was then completed by 208 male participants. The Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient was calculated for the initial 100-item version of the Sexual Orientation Scale along with item analysis and factor analysis. These statistical manipulations were computed to help eliminate items that did not discriminate well. The final version of the Sexual Orientation contains 43 items. Implications for the use of this scale and future directions in research are further explored.

Keywords: sexual orientation, scale development, males, assessment, exploration

As children grow up in our society, they are introduced to a wide range of knowledge about sexual behavior by their parents, siblings, and peers. Part of their education addresses the ideas of sexual orientation and/or preference. The inherent messages in this education are that a person is either heterosexual (sexually attracted to members of the opposite sex), homosexual (sexually attracted to members of the same sex), or bisexual (sexually attracted to members of both sexes).

Historical Overview of Sexual Orientation

A number of theories on the origin of homosexuality have attempted to define homosexuality. A number of these theories (c.f. Drescher, 2008; Ellis, 1936; Freud, 1922/2010; Krafft-Ebing, 1887/1965; Nuttbrock et al., 2009) place sexual orientation within the context of an individual’s overall sex role identity. These individuals link sexual attraction for men toward women with a masculine sex role orientation and sexual orientation toward men with a feminine sex role orientation (Axam & Zalesne, 1999; Mata, Ghavami & Wittig, 2010; Storms, 1980). Sexual orientation refers to a particular lifestyle (behavior) that an individual displays. Storms (1980) and Moradi, Mohr, Worthington, & Fassinger (2009) found most theories about the nature of sexual orientation emphasize either the person’s sex role orientation or erotic orientation. Although these assumptions have had a major impact on the development of theories, research, clinical practice, and even popular stereotypes, neither assumption has been adequately tested in past research. A homosexual person is one defined as having preferential erotic attraction to members of the same sex and usually (but not necessarily) engaging in overt sexual relations with them (Crooks & Baur, 2008; Marmor, 1980).

Cass (1984) and Harper & Harris (2010) identified four steps in the discovery process that people experience as they begin to identify their sexual orientation:

1. Individuals come to perceive themselves as a homosexual by adopting a self-image of what it means to be homosexual.

2. Individuals take this self-image a step further and allow it, through interaction with others, to become a homosexual identity.

3. Individuals assume the necessary affective, cognitive, and behavioral strategies in order to effectively manage this identity in everyday life.

4. Individuals find a way with which to incorporate the new identity into an overall sense of self.

Assessment of Sexual Orientation

Fergusson & Horwood (2005) wrote a review of the multitude of methods that have been used to assess sexual orientation. Conceptualization of sexual orientation as dichotomous (i.e., heterosexual and homosexual) was overturned over 60 years ago by Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin (1948) and by Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin, and Gebhard (1953). These studies resulted in the development of a 7-point scale in which 0 represented exclusive heterosexuality and 6 represented exclusive homosexuality. Three on the scale indicated equal homosexual and heterosexual responsiveness. Individuals were rated on this continuum based upon their sexual behavior and physical reactions (i.e., physical attraction to desired partners) (Coleman, 1987; Fergusson & Horwood, 2005).

Although this notion that people fall in a continuum better represented the realities of the world (Bagley & Tremblay, 1997; Silenzio, Pena, Duberstein, Cerel, & Knox, 2007), the Kinsey Scale has many limitations for accurately describing an individual’s sexual orientation. The scale assumes that sexual behavior and erotic responsiveness are the same within individuals. In response to this criticism, Bell and Weinberg (1978) used two scales in their extensive study of homosexuality. They examined two scales: one for sexual behavior, and one for erotic fantasies. Bell & Weinberg (1978) found discrepancies between the two ratings. Paul (1984) and Garnets & Kimmel (2003) also reported discrepancies in approximately one-third of their homosexual samples. It was reported that most men saw their behavior as more exclusively homosexual than their erotic feelings (Coleman, 1987; Fergusson & Horwood, 2005; Schwartz, Kim, Kolundzija, Rieger & Sanders, 2008).

Coleman (1987) and Fergusson & Horwood (2005) suggested that while this dichotomous and continuous view of sexual orientation represented an improvement in assessment of sexual orientation, several clinicians and researchers have recommended additional dimensions (Fox, 2003). These dimensions are those based upon both the biological sex of the partner and the biological dichotomous sex of the individual.

As the literature on psychological testing and homosexuality unfolded, it became clear that tests were not very effective in creating special scales, signs or scoring patterns that could differentiate homosexuals from heterosexuals (Garnets & Kimmel, 2003; Paul, Weinrich, Gonsiorek, & Hotvedt, 1982). Homosexuality was no longer being studied as an illness. Contrastingly, literature has brought forth strong data that dismiss the notion that homosexuality is a disorder (Cass, 1984; Coleman, 1982; Harper & Harris, 2010; Henchen & O’Dowd, 1977; Morin & Miller, 1974; Tripp, 1975; Troiden, 1977; Weinberg, 1978).

One of the major flaws in current psychological tests is that there is a belief that a prediction/diagnosis can be made that would tell an individual whether he is heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual. It is the authors’ belief that it is inappropriate to predict what kind of lifestyle an individual will/should follow. What is more feasible is to assist an individual as he or she explores the experience of uncertainty. Therefore, an instrument is needed that has the sensitivity to help clients explore their sexual orientation, not one that identifies levels of disturbance.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study was to construct an instrument that would help counselors in assisting clients who wish to explore sexual orientation. The instrument was to:

• Identify issues that need to be addressed by the client during the discovery of sexual orientation.

• Focus on issues such as self-definition, self-acceptance, fears, sexual fantasies, and understanding of lifestyle.

• Provide an information base for counselors as they help their clients unfold significant characteristics of their personality.

• Provide counselors a tool for helping clients meet the challenges they face now and will face in the future.

Method

Participants

The volunteer population of this study consisted of males who were either a) receiving personal counseling at a university counseling service, community mental health agency, and/or private practice; b) enrolled in introductory psychology classes at universities or community colleges; or c) participating in local men’s groups (i.e., Jaycees, Lions Clubs, support groups, etc.).

Two universities in California, eight universities in Texas, and one university in Wisconsin assisted in the collection of data. Three mental health agencies and four private counseling centers also were recruited for assistance in data collection. The private counseling centers served primarily gay and lesbian clients from the Dallas/Ft. Worth area.

Directors and/or counselors at the mental health sites mentioned above were visited. The purpose of the study was explained and they were asked if they would approach their clients (straight and gay) to determine their willingness to participate in the study. If the counselors were willing to speak to their clients, they were given instructions to share with clients who agreed to participate. They were instructed to give the client the research packet and return the completed information in the enclosed addressed/stamped envelope. Seventy-five agreed and completed packets from this group of mental health agencies were obtained.

Permission from psychology professors at the universities and/or colleges to address their introductory psychology classes was obtained for recruiting more subjects. The purpose of the study was shared with the class, willing participants were moved to another classroom, and they completed the research packet. One hundred and six packets were completed through this procedure.

Men’s groups were approached to obtain additional participants. Groups such as Jaycees, Lions Clubs, and Gay Men’s Support Groups were contacted and visited. A presentation was made that addressed the purpose of the study. Willing participants were provided with information packets, which they returned in enclosed envelopes. Thirty-three completed packets from representatives of the men’s groups were received. Twenty-eight of the 33 came from gay men’s support groups.

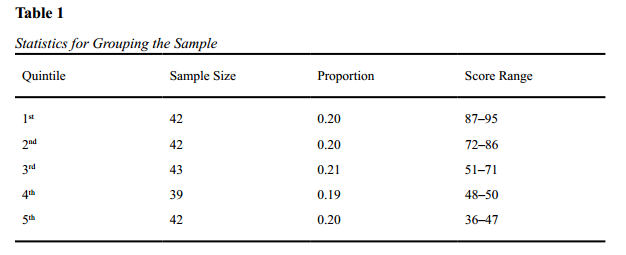

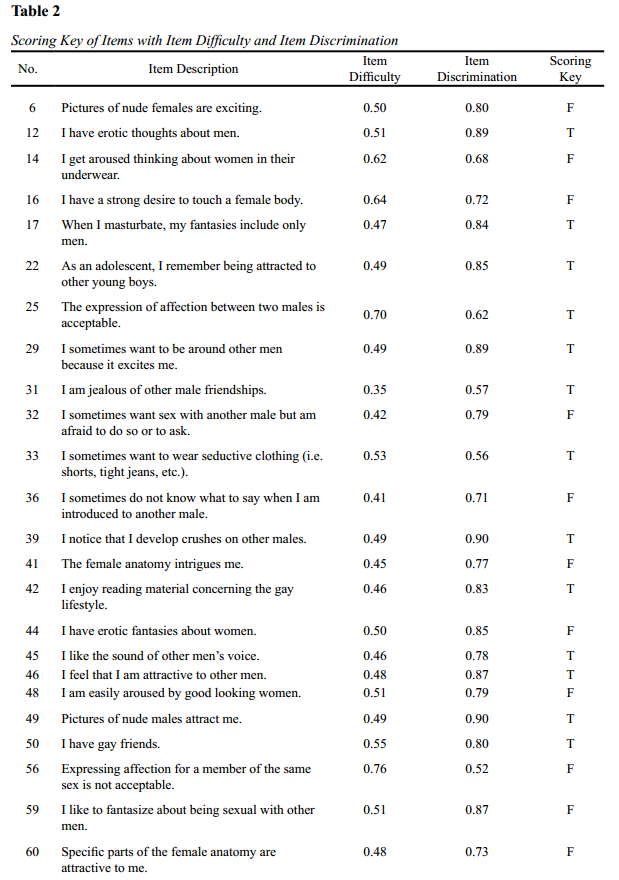

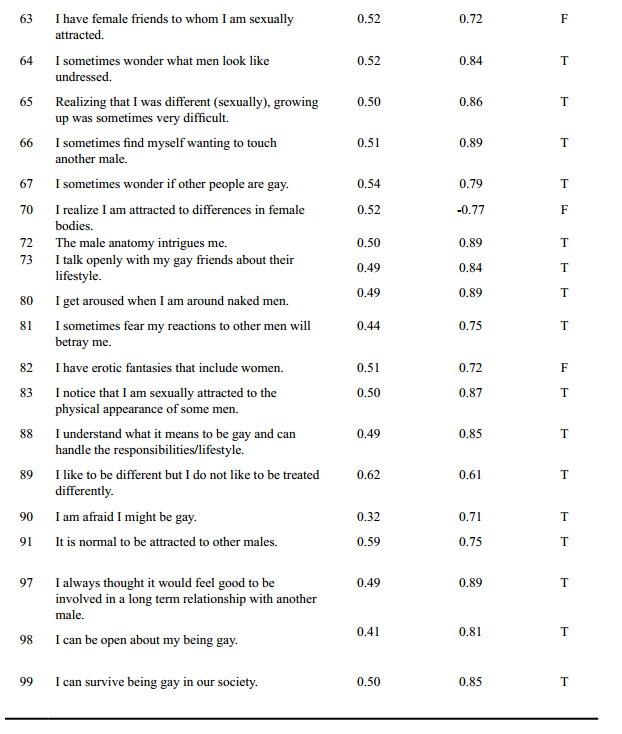

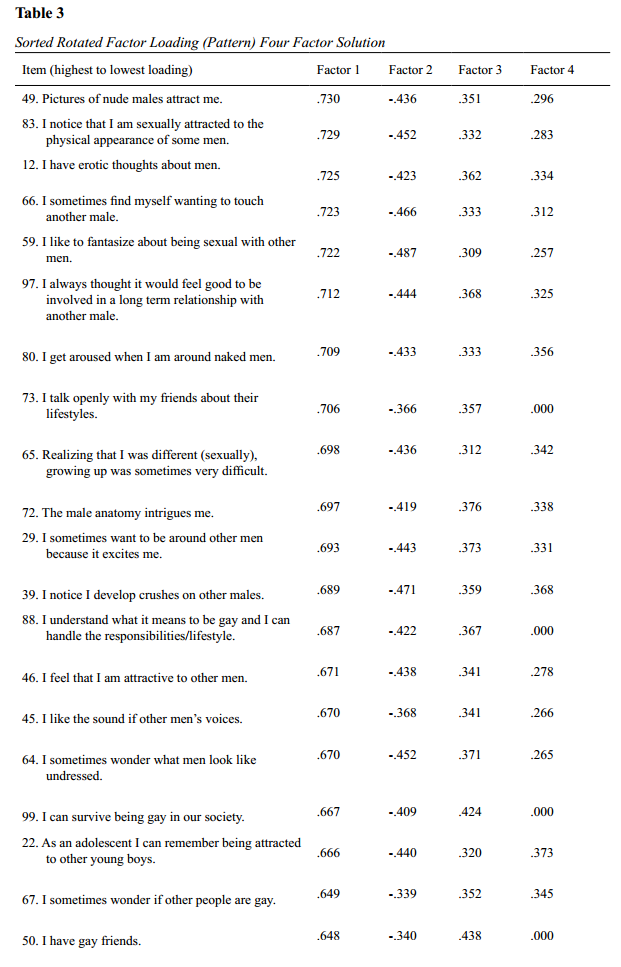

Demographic information from the personal data form was summarized and examined across the variable of sexual orientation on the following factors: educational level, socio-economic status, age, ethnicity, self-rating on the Kinsey Sexuality Scale and whether or not the participant was currently in counseling or psychotherapy. The males in the sample identified themselves as being either homosexual (gay) or heterosexual (straight). The males self-identified as gay or straight by rating themselves on the seven-point Kinsey Sexuality Scale (0=exclusively heterosexual to 6=exclusively homosexual). Straight responses were identified as those of which the men rated themselves as zero (0) or one (1) and gay responses were identified as those in which the men rated themselves as five (5) or six (6) on the Kinsey scale. Only six subjects rated themselves as 2, 3 and 4. The scales completed by these 6 subjects were not used in this study.

The sample consisted of a total of 208 men from cities in Texas, Wisconsin, and California: 132 were between the ages of 18–25 (63.5%); 52 were between the ages of 26–33 (25.0%); and 24 were between the ages of 34–40 (11.5%). According to the Kinsey Scale Rating, 104 were straight (50%) and 104 were gay (50%). Of the men who participated in the sample, 85 (40.9%) had received counseling and 123 (59.1%) had not.

Procedure

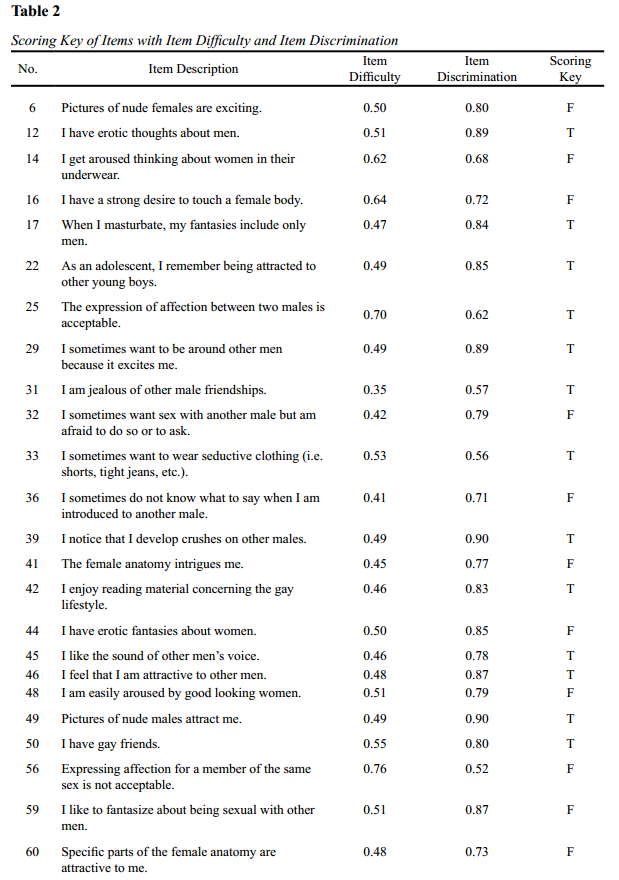

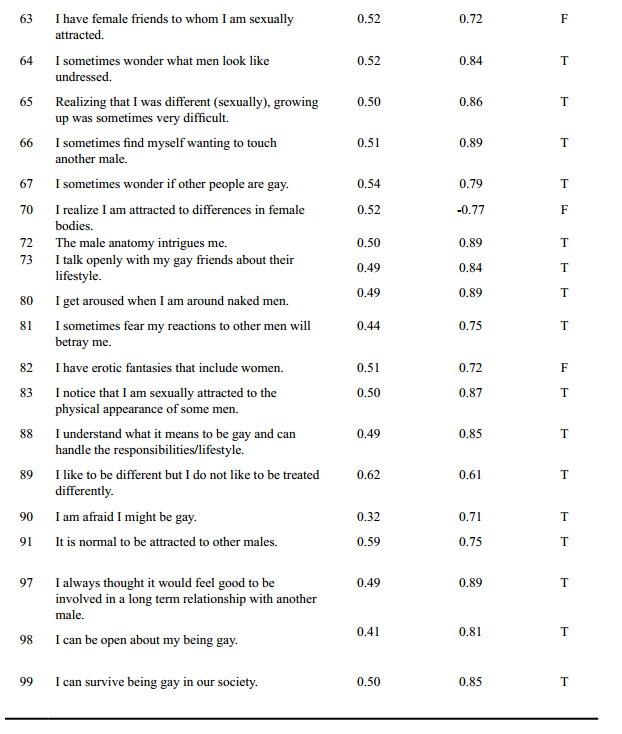

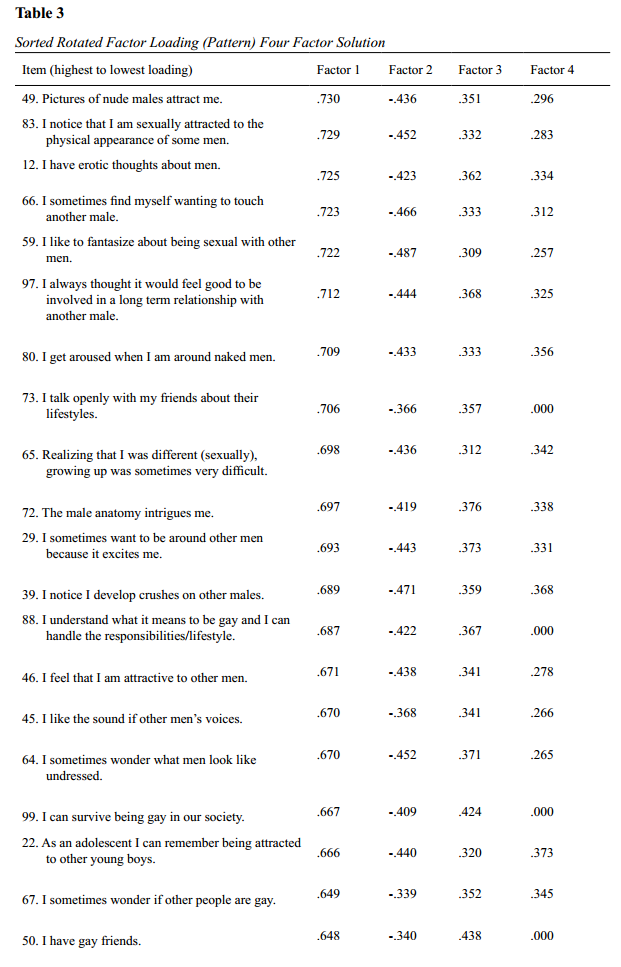

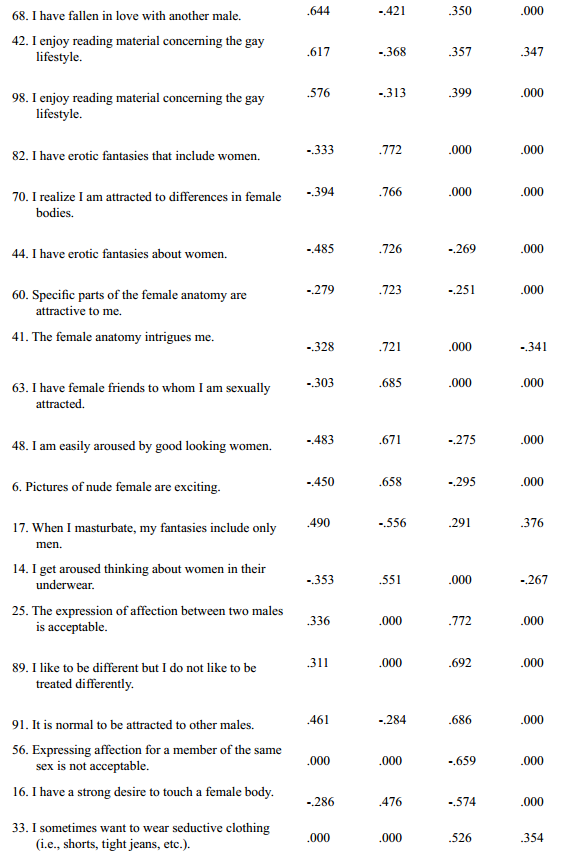

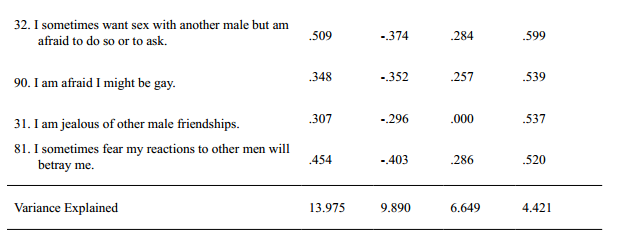

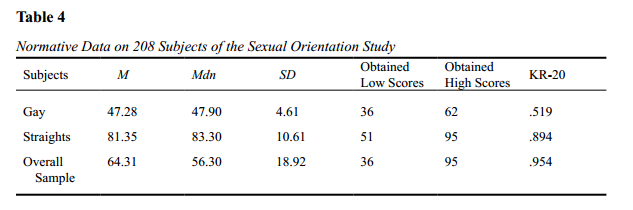

The first procedure consisted of the development of the items for the Sexual Orientation Scale. In order to achieve this task, thirty gay men who described themselves as being happy/satisfied with the gay lifestyle were interviewed. The men were identified via personal contacts and gay organizations. Their input was used to develop items for the Sexual Orientation Scale.