Lorraine J. Guth, Garrett McAuliffe, Megan Michalak

As the counseling profession continues to build an international community, the need to examine cultural competence training also increases. This quantitative study examined the impact of the Diversity and Counseling Institute in Ireland (DCII) on participants’ multicultural counseling competencies. Two instruments were utilized to examine participants’ cross-cultural competence before and after the study abroad institute. Results indicated that after the institute experience, participants perceived themselves to be more culturally competent, knowledgeable about the Irish culture, skilled in working with clients from Ireland, and aware of cultural similarities and differences. Implications for counselor education and supervision, and future research also are outlined.

Keywords: study abroad, multicultural competencies, cross-cultural competence, international, counselor education and supervision, Ireland

The standards set by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2009) require programs to provide curricular and experiential opportunities in social and cultural diversity. Specifically, CACREP requires counseling curricula to incorporate diversity training that includes “multicultural and pluralistic trends, including characteristics and concerns within and among diverse groups nationally and internationally” (CACREP, 2009, Section II, Code G2a; p. 10). Endorsement of diversity training by the counselor education accrediting body underscores its importance in counselor training; therefore, counselors-in-training must be provided opportunities to be culturally responsive in their work with clients (McAuliffe & Associates, 2013; Sue & Sue, 2012).

This cultural responsiveness is particularly important given the globalization of the counseling movement and the need for counselors to become globally literate (Hohenshil, Amundson, & Niles, 2013; Lee, 2012). However, counselor education training programs have fostered this multicultural competence with students in myriad ways (Lee, Blando, Mizelle, & Orozco, 2007). For example, multicultural courses have often focused on developing trainees’ cross-cultural competencies in the three broad areas of awareness of their own cultural values and biases; knowledge of others’ customs, expectations, and worldviews; and culturally appropriate intervention skills and strategies (Sue, Arredondo, & McDavis, 1992).

A body of literature has examined the progress of educational programs in incorporating these aspects of diversity into the curricula. For example, Díaz-Lázaro and Cohen (2001) conducted a study that explored the impact of one specific course in multicultural counseling. They found that cross-cultural contact, such as with guest speakers, helped students develop multicultural knowledge and skills; however, they found no indication that the course impacted students’ self-awareness. Guth and McDonnell (2006) examined counseling students’ perceptions of multicultural and diversity training. Courses were found to contribute somewhat to students’ knowledge, but the study found that students gained greater knowledge from personal interactions among peers, interactions with faculty, and other experiential activities outside of coursework. Additional research has shown that multicultural training is significantly related to multicultural competence (Castillo, Brossart, Reyes, Conoley, & Phoummarath, 2007; D’Andrea, Daniels, & Heck, 1991; Dickson, Argus-Calvo, & Tafoya, 2010). A clear message from the literature highlights the importance of personal cross-cultural contact in culturally responsive counseling.

This previous research was limited in that the authors examined only the impact of training offered in the United States, leaving out the potential added value of personal cross-cultural experiences in an international context. Given the impact of direct cross-cultural experiences, a study abroad experience for counselor trainees might be a powerful way to deepen cultural understanding and responsiveness. This quantitative study was designed to examine the outcomes of this counselor trainee study abroad institute on participants’ perceptions of their multicultural competence.

Research on Study Abroad Experiences

Study abroad programs are not commonly rigorously researched because “program evaluation is an afterthought to an ongoing program undertaken by extremely busy program administrators” (Hadis, 2005, p. 5). Although data regarding study abroad experiences are primarily anecdotal, the literature does suggest several positive outcomes of a study abroad institute including personal development, intellectual growth and increased global-mindedness (Carlson, Burn, Useem, & Yachimowicz, 1991). Short-term study abroad experiences also were found to produce positive changes in cultural adaptability in students (Mapp, 2012). However, most of the study abroad research has been conducted in disciplines other than counseling, such as business (Black & Duhon, 2006), nursing (Inglis, Rolls, & Kristy, 1998), and language acquisition (Davidson, 2007). Furthermore, the research has mainly focused on the experiences of undergraduate university students and has not examined the experiences of graduate trainees (Drews & Meyer, 1996).

Several studies have been conducted that are relevant to the counseling profession. Kim (2012) surveyed undergraduate and graduate social work students and found that study abroad experiences are a significant predictor of multicultural counseling competency. Jurgens and McAuliffe (2004) also conducted a study that explored the impact of a short-term study abroad experience in Ireland on graduate counseling student participants. The results indicated that this program was helpful in increasing students’ knowledge of Ireland’s culture, largely due to experiential learning and personal interactions. The current study expands on Jurgens and McAuliffe’s research (2004) by further examining the impact of a counseling and diversity institute that was offered in Ireland. The primary research questions for this quantitative study were as follows: (1) Did the study institute have an impact on participants’ multicultural counseling competencies? (2) Did this study institute have an impact on participants’ multicultural counseling competencies in working with individuals who are Irish?

Method

Participants

Twenty (87%) graduate counseling students and three (13%) professional counselors voluntarily participated in this research study while attending the DCII in Ireland. The sample consisted of 83% women and 17% men; 82% identified themselves as Caucasian/European American, 9% as African American, and 9% did not identify their race. The mean age for the sample was 32 (range: 22–60 years). Regarding sexual orientation, 91% of the participants indicated they were heterosexual; 4% indicated they were gay; and 4% indicated they were bisexual. Regarding disability status, 87% of the participants reported not having a disability, 9% indicated they had a disability, and 4% did not answer the question.

Instruments

The study assessed participants’ cross-cultural counseling competence with the Cross-Cultural Counseling Inventory-Revised (CCCI-R, LaFromboise, Coleman, & Hernandez, 1991). The CCCI-R is a 20-item instrument initially created so that supervisors could evaluate their supervisees’ cross-cultural counseling competence. Questions on this instrument are rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 6 = strongly agree). The scale has been found to have high internal consistency and reliability, and high content validity (LaFromboise et al., 1991). Another “recommended use of the CCCI-R is as a tool for self-evaluation” (LaFromboise et al., 1991, p. 387). Therefore, the CCCI-R was slightly modified so that participants could rate themselves to understand perceptions of their own cultural competence, rather than rate other counselors on their cultural competence. Higher scores on this instrument indicate an individual’s belief that he or she has greater cultural competence. Sample prompts include the following: “I am aware of my own cultural heritage,” “I demonstrate knowledge about clients’ cultures,” and “I send messages that are appropriate to the communication of clients.” In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the CCCI-R and it was reliable at both times of measurement (pretest = .91; posttest = .93).

Four additional Likert-type items were added to the pretest and posttest questionnaires, which asked participants to rate their multicultural awareness, knowledge, and skills related to the Irish culture. The items included were as follows: (1) I am knowledgeable of the culture of Ireland; (2) I possess the skills in working with a client from Ireland; (3) I am aware of the differences between the Irish culture and my own culture; and (4) I am aware of the similarities within the Irish culture and my own culture. Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each item from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Because of the significant (p < .01) correlation among these four items, a single variable was established called Ireland Multicultural Counseling Competencies Scale (IMCCS). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the IMCCS, which was reliable at both times of measurement (pretest = .88; posttest = .90).

Procedure

At the beginning of the study abroad institute, participants completed a pretest questionnaire that contained a demographic information form, the CCCI-R, and the IMCCS. Participants then participated in the two-week study abroad institute. At the conclusion of the institute, participants completed a posttest questionnaire that contained the CCCI-R and the IMCCS.

Diversity and Counseling Institute in Ireland. Study abroad institutes offered in the counseling profession can further counselors’ multicultural competence by immersing trainees in a non-American culture for a period of time. With that intent, the two-week DCII was created to increase participants’ cultural awareness, knowledge and responsiveness. The goals of the DCII were to increase participants’ (1) awareness of their own cultural background and values; (2) knowledge of the American, Irish, and British cultural perspectives; and (3) knowledge of culturally appropriate counseling strategies. Participants learned about the counseling profession in Ireland from leaders in the Irish mental health field; studied core multicultural issues with nationally known U.S. counseling faculty; were immersed in the Irish culture through tours, lectures, and informal experiences; and visited Irish counseling agencies and social programs.

Results

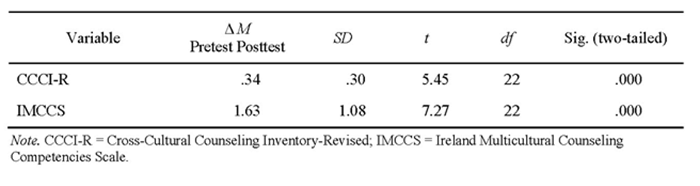

A t-test was performed to examine differences between participants’ CCCI-R mean score across time from pretest to posttest (see Table 1 for mean differences and standard deviations). There were significant differences (p < .0001) in participants’ overall scores on the CCCI-R after they attended the DCII in Ireland, indicating that participants perceived themselves to be more culturally competent by the end of the study abroad experience.

A t-test also was utilized to examine differences between participants’ IMCCS mean score across time (see Table 1 for the mean difference and standard deviations). There were significant differences (p < .0001) in participants’ overall scores on the IMCCS after attending the DCII in Ireland. Thus, participants thought they were more knowledgeable about the culture of Ireland, possessed more skills in working with clients from Ireland, had an increased awareness of differences between the Irish culture and their own, and had an increased awareness of similarities between the Irish culture and their own.

Table 1

Mean Difference between Participants’ Pre- and Post-Institute Multicultural Competence Scores

Discussion

Regarding the under-researched topic of intentional study abroad counselor education experiences, this study indicated that such an experience can have a positive impact on counselors’ multicultural competency. Previous research on non-counseling study abroad opportunities found that participants experienced personal development, intellectual growth and increased global-mindedness (Carlson et al., 1991). This study begins to address whether a counseling international experience has an effect on counselor multicultural competency.

International study abroad experiences can affect individuals’ perspectives on other cultures, as well as on their own. In the case of this research, participants reported an increase in their cultural competence after the intentional study abroad counselor education experience. These results confirm previous social work research that found a positive relationship between studying abroad and multicultural competencies (Kim, 2012). Further research should explore what components of this institute in particular influenced participants’ multicultural awareness, knowledge and skills.

The overall multicultural counseling competency improvement demonstrated in this study is encouraging. It is important to note that the institute included both experiences and conceptual material. The learning was perhaps enhanced by the experiential learning theory model used to design the institute (Kolb & Kolb, 2009). In this study abroad institute, experiences included visits to specific counseling and educational programs. Participants then reflected on those experiences through journaling and large group processing. Counselor educators might pursue such international initiatives to trigger counselor cultural self-awareness, increase knowledge of other cultures, and build culturally responsive counseling skills.

Study abroad for counselors might be seen as a “value-added” learning opportunity. While at-home multicultural counselor education has been studied (Cates, Schaefle, Smaby, Maddux, & LeBeauf, 2007; Zalaquett, Foley, Tillotson, Dinsmore, & Hof, 2008), such learning may be enhanced by the experience of being immersed in a foreign culture (Kim, 2012). Prolonged immersion in another culture allows counselors-in-training to gain a more nuanced understanding of the differences and similarities among cultures. Participants reported being more aware than before of differences and similarities between the Irish culture and their own culture. Although not all immersion opportunities happen internationally, the degree to which these participants were immersed was novel and led to a significant increase in culturally relevant knowledge, skills and awareness. The degree to which immersion experiences are effective should continue to be explored within the counseling profession.

Transferability of the learning from study abroad is of course crucial, as it would be insufficient to merely learn the particulars of another counseling culture. In that sense, the overall dislocation of being in a foreign culture may transfer to an increase in trainees’ empathy for members of non-dominant cultures in their homelands. It would be difficult to simulate such experiences in the domestic environment. Thus, when designing training experiences, educators could consider the impact of experiential training experiences outside of the home country. While planning these experiences are logistically challenging, the payoff can be impactful (Shupe, 2013).

International study abroad institutes have implications for the counseling community at large. As the profession continues to construct a professional identity and establish its role in the mental health community, counselors must consider the counseling profession as a whole, not solely the parts of the profession within the cultural worldview. Incorporating international experiences into the training practice allows more counselors to communicate and connect as a whole, in order to best develop and advocate for the counseling profession. Furthermore, collaborating with counselors internationally provides counselors-in-training the opportunity to increase their cultural self-awareness, as well as allows counselor educators to examine current training practices and their effectiveness. This assessment may take place through direct observation of international training practices, or more covertly in reflecting on the components of the institute that appeared to impact students.

The results of this study need to be examined in light of several limitations. First, this pre-post design only examined the impact of this study abroad institute. Future research could compare study abroad experiences to other training methods. Future research also could disaggregate the factors that actually contributed to positive outcomes, by investigating the relative contribution of informal encounters, lectures on Irish counseling and social issues, general seminars on culturally alert counseling, and other experiences in the study abroad program. Second, participants volunteered to be part of this study and were predominantly Caucasian/European American and heterosexual women. Future research could seek to replicate these results, using a control group and a more diverse, randomly selected group of participants. Finally, the focus of this research was the impact of a DCII in Ireland. Future research could explore the impact of counseling study abroad programs in other countries. Long term follow-up measures also could be utilized to see if the positive changes in multicultural counseling competencies remain stable over time.

Conclusion

This study was designed to examine the impact of the diversity and counseling study abroad program in Ireland on participants’ multicultural competencies. The results indicate that the study abroad experience in Ireland enhanced participants’ multicultural counseling competencies. These results provide beginning data regarding the benefits of this type of study abroad diversity training and encourage counselor educators to pursue and evaluate such experiences.

References

Black, H. T. & Duhon, D. L. (2006). Assessing the impact of business study abroad programs on cultural awareness and personal development. Journal of Education for Business, 81, 140–144. doi:10.3200/JOEB.81.3.140-144

Carlson, J. S., Burn, B. B., Useem, J., & Yachimowicz, D. (1991). Study abroad: The experience of American undergraduates in Western Europe and the United States. New York, NY: Center for International Education Exchange. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 340 322)

Castillo, L. G., Brossart, D. F., Reyes, C. J., Conoley, C. W., & Phoummarath, M. J. (2007). The influence of multicultural training on perceived multicultural counseling competencies and implicit racial prejudice. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 35, 243–254. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2007.tb00064.x

Cates, J. T., Schaefle, S. E., Smaby, M. H., Maddux, C. D., & LeBeauf, I. (2007). Comparing multicultural with general counseling knowledge and skill competency for students who completed counselor training. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 35, 26–39. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2007.tb00047.x

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2009). 2009 CACREP Standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org

D’Andrea, M., Daniels, J., & Heck, R. (1991). Evaluating the impact of multicultural counseling training. Journal of Counseling & Development, 70, 143–150. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1991.tb01576.x

Davidson, D. E. (2007). Study abroad and outcomes measurements: The case of Russian. The Modern Language Journal, 91, 276–280.

Díaz-Lázaro, C. M., & Cohen, B. B. (2001). Cross-cultural contact in counseling training. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 29, 41–56. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2001.tb00502.x

Dickson, G. L., Argus-Calvo, B., & Tafoya, N. G. (2010). Multicultural counselor training experiences: Training effects and perceptions of training among a sample of predominately Hispanic students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 49, 247–265. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2010.tb00101.x

Drews, D. R., & Meyer, L. L. (1996). Effects of study abroad on conceptualizations of national groups. College Student Journal, 30, 452–461.

Guth, L. J., & McDonnell, K.A. (2006, April). Counselor education students’ perspectives on multicultural and diversity training. Poster session presented at the American Counseling Association Convention, Montréal, Quebec, Canada.

Hadis, B. F. (2005). Gauging the impact of study abroad: How to overcome the limitations of a single-cell design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30, 3–19. doi:10.1080/0260293042003243869

Hohenshil, T. H., Amundson, N. E., & Niles, S. G. (2013). Introduction to global counseling. In T. H. Hohenshil, N. E. Amundson, & S. G. Niles (Eds.), Counseling around the world: An international handbook (pp. 3–8). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Inglis, A., Rolls, C., & Kristy, S. (1998). The impact of participation in a study abroad programme on students’ conceptual understanding of community healthy nursing in a developing country. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28, 911–917. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00732.x

Jurgens, J. C., & McAuliffe, G. (2004). Short-term study-abroad experience in Ireland: An exercise in cross-cultural counseling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 26, 147–161.

Kim, W.-J. (2012). Enhancing social work students’ multicultural counseling competency: Can travel abroad substitute for study abroad? International Social Work, Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/0020872812454313

Kolb, A. Y. & Kolb, D. A. (2009). Experiential learning theory: A dynamic, holistic approach to management learning, education, and development. In S. J. Armstrong and C. V. Fukami (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of management learning, education, and development (pp. 42–68). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

LaFromboise, T. D., Coleman, H. L. K., & Hernandez, A. (1991). Development and factor structure of the Cross-Cultural Counseling Inventory-Revised. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 22(5), 380–388. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.22.5.380

Lee, C. C. (2012, September). The promise of counsel(l)ing’s globalization. Counseling Today, 14–15.

Lee, W. M. L., Blando, J. A., Mizelle, N. D., & Orozco, G. L. (2007). Introduction to multicultural counseling for helping professionals (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Mapp, S. C. (2012). Effect of short-term study abroad programs on students’ cultural adaptability. Journal of Social Work Education, 48, 727–737. doi:10.5175/JSWE.2012.201100103

McAuliffe, G. J., & Associates (2013). Culturally alert counseling: A comprehensive introduction (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shupe, E. I. (2013). The development of an undergraduate study abroad program: Nicaragua and the psychology of social inequality. Teaching of Psychology, 40, 124–129. doi:10.1177/0098628312475032

Sue, D. W., Arredondo, P., & McDavis, R. J. (1992). Multicultural counseling competencies and standards: A call to the profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 20, 64–88. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.1992.tb00563.x

Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2012). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Zalaquett, C. P., Foley, P. F., Tillotson, K., Dinsmore, J. A., & Hof, D. (2008). Multicultural and social justice training for counselor education programs and colleges of education: Rewards and challenges. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86, 323–329.

Lorraine J. Guth, NCC, is a Professor and Clinical Coordinator at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Garrett McAuliffe is a Professor at Old Dominion University. Megan Michalak, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at Antioch University New England. Correspondence can be addressed to Lorraine J. Guth, IUP Department of Counseling, 206 Stouffer Hall, Indiana, PA 15705, lguth@iup.edu.