Leah Brew, Joseph M. Cervantes, David Shepard

The use of social networking sites (SNS), and Facebook in particular, seems to be on the rise (Salaway, Nelson, & Ellison, 2008). The majority of users tend to be from the millennial generation (Hazlett, 2008), as are the majority of graduate counseling students. This discussion explores several areas regarding the use of Facebook. First, we review the literature on why students from the millennial generation are such avid users of Facebook. Second, we explore privacy settings: how Millennials establish privacy settings and what demographic factors may be correlated with the level of privacy settings they establish. Results from an online descriptive survey of counseling students are compared with and found in many ways to be inconsistent with the literature on the risk factors associated with limited use of privacy settings. Implications of and recommendations for using Facebook for counselors and counselor educators are provided.

Keywords: millennial generation, Generation Y, social networking sites, Facebook, ethics, boundaries

The use of social networking sites (SNS) is increasing in popularity with college students (Hazlett, 2008), and Facebook is one of the most popular sites (Salaway, Nelson, & Ellison, 2008; Fogel & Nehmad, 2009; Hazlett, 2008; Lehavot, Barnett, & Powers, 2010; MacDonald, Sohn, & Ellis, 2010). As of March 2013, Facebook had over 1.11 billion users overall (Facebook, 2013), but the more relevant statistic for this article is the evidence of the site’s widespread use by college students. Data collected in 2006 and 2007 from several studies found that about 60–65% of college students were using Facebook (Fogel & Nehmad, 2009; Lehavot et al., 2010; MacDonald et al., 2010). Recent research conducted on college students found that more than 85% of students who responded to the survey use SNS, and 89% of those who used SNS had a Facebook page (Salaway et al., 2008). Thus, the use of SNS and Facebook is officially part of the college student culture. The fact that so many college students have incorporated Facebook into their lives is highly relevant to the field of counselor education. The majority of students in both masters and doctoral level training programs will have come from this culture, with a strong likelihood that they enter college programs with an existing Facebook page, and anticipate a continued interaction with friends, families and classmates via Facebook. Yet, the use of Facebook raises challenging ethical and clinical issues for both students and counselor educators. These include boundary issues: most importantly, the risks associated with a student’s private information being accessible to clients; issues related to enhancing the integrity of the profession; and the ethical responsibilities of counselor preparation programs in admitting and preparing students for counseling careers. The purpose of this article is to examine the relevant literature on Facebook as it pertains to counselor education, and specifically literature that deepens an understanding of both why students use Facebook and how they use Facebook. Additionally, we will describe the results of a survey of Facebook use at our own master’s in counseling program at California State University, Fullerton (CSUF), which has a large student body, most of whom are members of the millennial generation. The nature of this survey is purely exploratory, with the goal of assessing whether Facebook use in one program supports or challenges the findings in the extant literature. The degree to which those findings are challenged will help clarify the need for and direction of future research. Finally, we will discuss the ethical dilemmas posed by Facebook, make recommendations on how counselor educators can prepare students to use Facebook ethically, and ensure that programmatic use of Facebook maintains the highest ethical standards.

Privacy Settings on Facebook

Before examining the literature, it is important to review the concept of privacy and privacy settings in Facebook, since the way Facebook users deal with privacy is critical to ethically-sound counseling practice. Personal information can be displayed on Facebook including name, address, e-mail, phone number, alma mater (high school and college), current employer and marital status (Facebook, 2013). In addition, questions about spiritual and political beliefs, interests and hobbies can be shared. Finally, the wall, a kind of virtual poster board, offers an opportunity to display any comments one wants to make about a particular topic (such as current events and topics, or a personal story) and has a platform to upload pictures. With each of these primary areas, users can determine whether the public, friends-of-friends, or friends only can see the information. Establishing privacy is usually done at one of these three levels, and Facebook defaults to public; so if a user does not know how to set privacy, most everything will be available for the public to view. This last point is especially salient for counseling students, since their familiarity with the technology of privacy settings directly bears on protecting their boundaries of privacy and keeping clients from accessing personal information.

Why Counseling Students Use Facebook: The Millennial Generation

Within the business profession, the concept of each generation holding its own sets of values is well documented (see Bergman, Fearrington, Davenport, & Bergman, 2011; Howe & Strauss, 2003; Mehdizadeh, 2010; Reith, 2005; Sandfort & Haworth, 2002; Steward & Bernhardt, 2010; Twenge, 2010; Twenge, Campbell, Hoffman, & Lance, 2010). For instance, several comparisons are made between the Silent Generation, baby boomers, Generation Xers, and Millennials comparing work values, school values, and marketing strategies (Twenge, 2010).

A starting point for understanding why the millennial generation of counseling students would be frequent users of Facebook is the role technology has played throughout these students’ development. As Reith (2005) has observed, the millennial generation is more technologically savvy than previous generations. The term researchers used to describe a generation born into the world of current technology is digital natives, as opposed to previous generations, termed digital immigrants, because they developed familiarity with technology as the technology emerged (Prensky, 2001). Additionally, the millennial generation came of age at a time when digital communication was crucial to maintain ties. Reith (2005) observed that many Millennials had parents who involved them in a variety of organized activities, which required highly structured schedules. He proposed that because of limited free time to socialize with friends, perhaps using technology such as texting and social networking provided them with an avenue to informally connect with others in their otherwise busy schedules. Ultimately, the use of SNS and especially Facebook became an integral part of millennial culture (Hazlett, 2008; Salaway et al., 2008).

Howe and Strauss (2003) and Reith (2005) reported that the millennial generation is more conventional than previous generations. They tend to have positive experiences with their parents who enforce rules and, consequently, seem to be trusting of authority and institutions. Perhaps this perception of trusting institutions such as Facebook increases the perception of Millennials that their information is private and safe.

Another possible cultural characteristic is related to the frequent description of Millennials as being narcissistic. One study, using a national sample of 15,000 high school seniors, was able to link narcissism with this generation (Twenge, 2010). Twenge deduced that the experiences of being wanted and therefore feeling special, and of being overprotected and given less responsibility, all may contribute to the higher scores on narcissism by Millennials (Twenge, 2010). Stewart and Bernhardt (2010), after administering the California Psychological Inventories (CPI) to 588 undergraduate students, also found that Millennials scored high on narcissism compared to students from previous generations. They suspected that one possible explanation for these results might be that Millennials are launched into adulthood much later as compared to previous generations. Mehdizadeh (2010) used the Narcissism Personality Inventory (NPI)-16 to assess the level of narcissism of 100 students who were Facebook users at York University. Strong correlations were found between higher scores on narcissism and self-promotional information displayed on the wall. The author asserted that the venue used to post one’s status on Facebook established an acceptable culture of boasting in this forum, which was a criterion used to establish the level of self-promotion.

Thus, the research suggests that Millennials may use Facebook more than previous generations (Hazlett, 2008; Salaway et al., 2008) because of several factors such as the experience of being digital natives; the convenience of connecting with friends through SNS to compensate for busy schedules; trust in institutions; and the correlations found between Millennials and higher scores on narcissism. At the same time, the research is limited, and it would be prudent not to stereotype a generation as narcissistic without more compelling evidence. It also is important to note that the measures used in the above-cited students did not ascribe pathological value to the construct of narcissism, as opposed to how clinicians tend to use the term.

How Millennials use Facebook: The Issue of Privacy Settings

While there is no literature on privacy settings and counseling students or novice counselors, a number of studies have looked at how the millennial generation tends to use privacy settings on Facebook. For the purpose of this article, the most important research involves Millennials involved in health care of some form. MacDonald et al. (2010) looked at the Facebook pages of young doctors in Australia and found that just over a third did not use any privacy options at all. Most of the doctors’ Facebook pages revealed personal information like spiritual or political beliefs, but withheld information such as home address and phone number. Very few of these pages demonstrated inappropriate behaviors such as drinking or using foul language when posting on the wall. However, many doctors had photos that were revealing and perhaps inappropriate for patients to view.

Lehavot et al. (2010) surveyed psychology students and found that about 60% allowed only friends to view their page, while 34% allowed the public to have full access to their Facebook page. The remaining 6% were unsure about privacy settings. Despite the high percentage of users who limited access to friends, they still posted questionable information or photos. When asked, about 3% of respondents had photos and 6% had information that they would not want classmates to see. Those percentages increased when asked about information or photos they did not want faculty (11%) and clients (29%) to see. Taylor, McMinn, Bufford, and Chang (2010) surveyed psychology students and psychologists and found that 85% of those with a Facebook page used at least some level of privacy. However, it is possible that this figure is so high because the sample included licensed psychologists, who may be older than Millennials and more conscientious of potentially crossing boundaries with clients who might gain access.

Other studies, not with health providers, but with Millennials in general, seem to indicate who among this generation would be most likely to disclose personal information; these findings may be relevant to counselor educators if they help identify which students are most likely to need instruction on protecting their Facebook privacy. What the literature suggests is that those individuals who are most likely to allow personal information to be seen are male and people not involved in romantic relationships (Fogel & Nehmad, 2009; Mehdizadeh, 2010; Nosko, Wood, & Molema, 2010; Salaway et al., 2008). The fact that young men tend to use Facebook for self-disclosure may relate to findings in other studies that Facebook disclosure is associated with the trait of risk-taking (Fogel & Nehmad, 2009). The one exception to the finding that men tend to disclose more than women relate to the display of photos, which appears to be a behavior associated with female Millennials (Mehdizadeh, 2010; Salaway et al., 2008).

Consequently, since the research found that about 15%–30% of users in the health professions do not use any privacy settings at all in Facebook, counselors-in-training also may be at risk (Lehavot et al., 2010; MacDonald et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2010). For individuals who did establish some level of privacy, many men posted information and women posted photos that they would not want clients, professors, or supervisors to see (Fogel & Nehmad, 2009; Lehavot et al., 2010; Mehdizadeh, 2010; Nosko et al., 2010; Salaway et al., 2008). In addition, individuals who posted their relationship status as single seemed to reveal more information, and many Millennials in counseling programs are likely to be single (Nosko et al., 2010). However, no research has been conducted to determine if these results resonate with the counseling profession.

Graduate Student Assessment of Facebook Use

Given the growing awareness of the graduate counseling student population at CSUF and the characteristically large number of students classified as Millennials, we, the authors, wanted to evaluate the level of disclosure with our own sample of students. The purpose of this survey was to evaluate whether millennial students in our graduate program used Facebook more than older generations. Secondly, we wanted to explore the risk factors associated with decreased use of privacy settings, such as being male, single and from the millennial generation as the literature seemed to indicate. Finally, we wanted to assess the impact of discussing the ethical challenges and uses of Facebook in each section of our law and ethics classes on privacy settings given the results obtained from the survey. This survey was meant to provide a descriptive understanding of our students to compare with the extant research.

Social Networking Survey

A brief survey was created based upon questions that arose from the literature regarding usage and privacy settings. The survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board at our university and was organized into four distinct areas that could be easily completed online. These areas included student consent to complete the survey, demographic information, social networking information and Facebook questions. The social networking information dimension asked questions about student involvement in SNS and knowledge about privacy settings. The Facebook questions addressed issues related to one’s profile and the public or private display of personal information.

The online survey was completed at two time intervals: late January 2012 (admin. 1) and early November 2012 (admin. 2). Prior to disseminating the survey in January 2012, the faculty had not yet incorporated any discussion about social networking or Facebook with students. During spring, summer and fall all sections of the law and ethics class included at least some discussion about social networking, using Facebook as an example. Each faculty member presented the information informally and without uniformity. Despite the differences in addressing this area in class with each of the instructors, who also are authors of this paper, the possibility of clients making friend requests on Facebook was presented, and students were encouraged to brainstorm ways in which they might handle this situation.

Participants

Students for this online survey were recruited from approximately 220 current matriculating students in the graduate program in counseling at a public university on the West Coast. They were invited via e-mail to participate, were guaranteed confidentiality, and had no negative consequences for refusing to participate. However, in both administrations they were provided with an incentive in a random drawing to win a $25 gift card from iTunes.

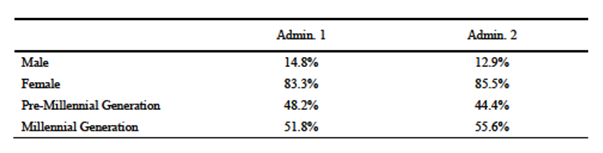

In late January 2012, we obtained 56 responses, and in early November 2012, we received 63 responses (24% and 29% of the students, respectively). In the initial administration, 92.9% of respondents reported using SNS, and 100% of those who used sites participated on Facebook. The second administration indicated that 90.3% of the respondents used SNS with 98.2% of this group participating on Facebook. These results are consistent with the literature about the popularity of Facebook among SNS (Salaway et al., 2008). Primary demographic information on each respective survey is found in Table 1. Note that slightly more than half of the respondents in both administrations were from the millennial generation.

Table 1

Demographic Information

Results

First Administration

The first set of results extrapolated from the survey included a review of risk factors for using few or no privacy settings on Facebook including being male (Fogel & Nehmad, 2009), having a relationship status of single (Nosko et al., 2010), and being from the millennial generation (Nosko et al., 2010). The first survey supported the literature with regard to gender. In our initial survey, 50% of the male students (4 of 8 men) used privacy settings for less than half of their information whereas only 14.6% of the female students (6 of 41 women) used privacy settings for less than half of their information. Regarding photos or videos that students would not want clients to see, 50% of men and women surveyed had such photos or videos. However, nearly all male students (6 out of 7) had information they would not want clients to see; the eighth male student did not specify. In contrast, 50% of female students had information they would not want a client to see.

The trends Nosko et al. (2010) found regarding the relationship between being single and using lower privacy settings did not hold true in our first sample of students. Of the fifteen students who identified as being single on the first survey, only one student did not have the highest levels of privacy established. In contrast, 9 of the 38 students who reported being in a relationship had set less than 50% of their information with some level of privacy. Therefore, in our graduate counseling student population, being single did not seem to correlate with lower levels of established privacy.

Finally, Nosko et al. (2010) found that younger individuals tended to have more information displayed on their Facebook page. When evaluating the reported levels of privacy established by our students in the first survey, this trend did not hold. The majority (86%) of students from the millennial generation reported establishing privacy settings for at least 50% of their information. Students from older generations were slightly less likely to establish privacy for at least 50% of their information. In our sample, 71% reported establishing this level of privacy. Therefore, our data did not support the trends found in the literature for establishing levels of privacy relating to age or relationship status, but we did find that male students seemed to display more information.

Differences Between Administrations

Next, we had a comparison made between the first and second administrations of the survey to determine if teaching about the ethical challenges of using Facebook would impact privacy settings. In the first administration, about 48% reported establishing the maximum privacy allowed, and another 30.8% reported that more than half their information was private. The second administration showed an increase in the maximum privacy allowed at 63.2%. Another 26.3% of students reported having over half their information private. These results indicated an increase in privacy settings from the first to the second administration.

We wanted to explore some possible explanations for this change. First, we had a third party compare the two lists of names and found that 11 students completed the survey a second time: seven already had the highest level of privacy set in the first survey and did not change their settings; three increased their level of privacy; and one did not have the highest level and did not increase the level of privacy. Some students made comments in the first survey stating that participating in the survey made them more aware of privacy settings, and consequently they wanted to establish more rigorous privacy settings; it appears that three students did, in fact, make this change. These results imply that at least part of the increase may have simply been due to completing the initial survey. Next, we had a third party review the names of all students who were currently in or had taken the ethics course between the two administration times. The results indicated that 10 students who took the second survey had completed an ethics course between administrations, and we know that during this time all instructors who taught ethics discussed the ethical challenges of using Facebook. In reviewing the results of the second administration, we found six had established the highest level of privacy; two had 50% or more of their information set as private; and two had less than 50% of their information set as private despite having been exposed to the risks associated with limited privacy. We hope that these students are simply less active users of Facebook and therefore do not feel the need to establish more rigorous settings, but we do not know for certain.

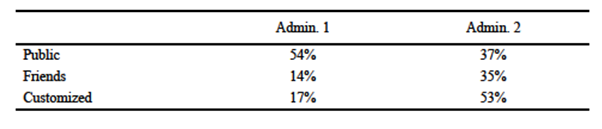

Several articles noted that a few individuals seem to establish some privacy settings, but still had photos that can be seen by the public (Lehavot et al., 2010; MacDonald et al., 2010; Salaway et al., 2008). Much like the rigor of privacy settings, the results of photos displayed to the public shifted between each administration (see Table 2).

Table 2

Photo Visibility Privacy Level on Facebook

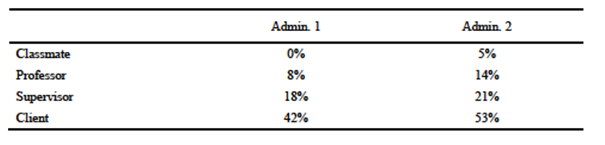

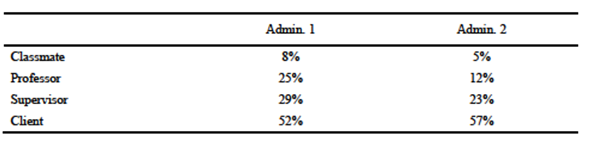

Lehavot et al. (2010) found that 3% of respondents had photos and 6% had information they would not want their classmates to see. These numbers increased when asked about faculty (11%) and clients (29%). Our results showed this same trend with both administrations of the survey. Table 3 shows the trend for pictures or videos that students would not want classmates, professors, supervisors or clients to see. Table 4 reveals a similar trend about information posted that students would not want others to see. These trends did not change substantially between administrations as we had hoped. We suspect that even though some students increased their levels of privacy, they did not remove information or photos assuming that the improved privacy settings would protect them. This may be explained by the assertion from Howe and Strauss (2003) and Reith (2005), who believe the millennial generation is more trusting of institutions since they had positive experiences with their parents.

Table 3

Picture and Video Visibility Privacy Level

Table 4

Information Posted Privacy Level

We wanted to examine the implications for the current generation of counseling students, as well as for counselor educators on the use of SNS, and specifically Facebook. The potential ethical minefields Facebook presents for students at every level of counselor development persuaded us that both a perusal of the literature and a survey of our own students’ Facebook use would yield important information. In particular, we looked at the prevalence of Facebook use, its possible roots in the culture of Millennials, and the extent to which Millennials expose their private lives on this particular SNS. The results of our two surveys helped us understand Facebook use in our own program, informing us as faculty about retooling ethics education for our students. The surveys also lent support to previous research findings in some areas and raised questions regarding the generalizability of others. However, our survey results are only descriptive and may not be representative of all of our students or of counseling students across the country.

Facebook Risks for Counselors-in-Training

Millennials are the most prolific generation of users of social networking sites (Hazlett, 2008) and therefore, compared to previous generations, have been found in the literature to be more likely to have posted personal information on a SNS. Our data did not support this assertion; the reasons for this phenomenon remain unclear and require further research. It has been suggested that this generation is particularly self-absorbed, and there is some empirical evidence supporting this notion (Mehdizadeh, 2010; Steward & Bernhardt, 2010; and Twenge, 2010), but a less pathologically-tinged explanation may be that self-disclosure on Facebook and other SNS is a cultural norm for them. Regardless, the critical issue is the extent to which counseling students are employing Facebook privacy settings. If, indeed, Millennials tend to use fewer privacy options and are likely to post more information on the wall as compared to other generations (Nosko et al., 2010), their increased use of SNS places this group at a higher risk for crossing boundaries between their personal and professional lives as they enter the counseling profession (Allen & Roberts, 2011). Our survey of students supported the concern that counseling students had created boundary issues for themselves with Facebook use previous to entering the program, and continued to place themselves at risk for further crossings while in the program. Over 90% of our students who responded to our survey used Facebook, and over half had posted information they would not want clients to see. It should be noted that almost half of the students in our first sample and a somewhat higher percentage in the second survey had established maximum levels of Facebook privacy. But that still meant a significant number of our counseling students had recently posted photos, videos and personal information that might compromise a professional relationship if clients were to discover them, and many of these students were using less than maximum privacy settings. Even those using maximum settings continued to post revealing personal information, but with the expectation that no client could access it.

In fact, even with the use of privacy options, counseling students may not be aware of the challenges of controlling access to their Facebook content. Privacy settings do not guarantee that information will remain private. For instance, when using the friend-of-a-friend level of privacy, it is possible that students have unknown common acquaintances with professors or clients; this might inadvertently give a client or faculty access to their information. Consequently, the unintentional dissemination of information remains a possibility and an ethical dilemma. Furthermore, Facebook friends may not use privacy settings, and they may pull an inappropriate picture from a user’s wall and “tag” it, making it available for clients or faculty to view. Consequently, the unintentional dissemination of information remains both a possibility and an ethical dilemma, and requires further study to have a clearer understanding of these risks.

What are the actual ethical consequences raised by Facebook use? Initially, potential damage to clients if they discover revealing information about their counselors could be a serious risk. The credibility of the counselor can be impaired, clients may become tantalized by the counselors’ personal life, and the counselor’s often challenging efforts to maintain clinically helpful boundaries in sessions may be compromised. For psychologically fragile clients who need to temporarily perceive their counselors as authority figures while they recover and develop new coping skills, the discovery of their counselors’ private life might undermine their recovery.

A related issue, as described in The American Counseling Association’s code of ethics, is the counselor’s ethical role in making a distinction between one’s roles personally and professionally (ACA, 2005). Using SNS is where the line between one’s professional world and private world could mingle (Birky & Collins, 2011). Judd and Johnston (2012), addressing related issues for social work training programs, make observations that seem equally relevant to the counseling profession. For example, they note the importance of impression management and the development of an identity that reflects a level of professional dignity consonant with the mission and ethics codes of the particular mental health discipline. When personal information such as a student’s romantic life or photographs of a student in informal situations becomes available, dignity can be compromised, affecting not only the student-counselor, but the profession itself. If that material is seen by a client, the counseling relationship may be damaged, and if seen by a fieldwork agency clinical director or potential employer, the student risks losing a work opportunity.

Myers, Endres, Ruddy, and Zelikovsky (2012) noted an additional concern when they raised the issue of what happens when a client may want to befriend the counselor on Facebook. Agreeing to the request may expose the counselor’s private life, while refusing the request risks wounding the client. In either case, handling the issue requires careful ethical decision-making and skilled intervention with the client. Perhaps one of the most troubling risks associated with self-disclosure on Facebook or other SNS is the increased risk of counselors-in-training being stalked by psychologically disturbed clients (MacDonald et al., 2010). These potential boundary consequences are assertions, though, and merit the need for further research.

Some have argued that Facebook boundary crossings could be therapeutic and appropriate under the right circumstances. Taylor et al. (2010) asserted that younger clients and professional counselors may believe that the use of SNS is an appropriate method of communication or even a therapeutic tool. The millennial generation and perhaps even the current zeitgeist values transparency more than ever before (as seen on television shows such as Oprah or Dr. Phil), which intentionally blurs the boundaries between personal and professional roles in the interest of a more authentic relationship (Zur, Williams, Lehavot, & Knapp, 2009). Birky and Collins (2011) considered context when using SNS between counselor and client. They suggested that the use of SNS might be appropriate under certain circumstances such as theoretical orientation, length of relationship, and both the client’s and counselor’s culture. Nevertheless, while there might be therapeutically valuable uses of SNS in some cases, the risks of Facebook exposure resulting in negative consequences for both counseling students and clients may be high.

Facebook Risks with Admissions and Advising

Prospective and current counseling students may not realize their risks of participating on SNS (Harris & Younggren, 2011) with regard to their education and training. Lehavot (2009) published an article exploring the ethical use of doing Internet searches by faculty members in admissions and advising capacities. Many individuals reported a belief that their blogs or what they posted on SNS was private (Lehavot, 2009). However, Lehavot (2009) argued that in some ways, the Internet is seen as a public domain; therefore, providing an informed consent to prospective students or students entering into a counseling program may be a way to ameliorate the perception by students that this information is private. Even with informed consent, there may be complications. Faculty members may risk discovering information that negatively biases them if they conducted Internet searches on problem students. Students may feel betrayed by this course of action, and documentation could be complicated if they would need to be counseled out of the program. Finally, Lehavot (2009) asserted that completing Internet searches may inadvertently be discriminatory because not all students have equal access. In the admissions process, for instance, one student may have significant positive information on the Internet, while another does not because of lack of resources, despite having similar accomplishments. In contrast, one student may have made a poor judgment in which a photo was taken and subsequently posted online unbeknownst to him or her, while another student may not have had the misfortune of a photo being posted despite making the same poor decisions. Prospective and current students may not consider how much information could be available to faculty or others when using SNS, which could be problematic. More research is needed to assess the desire of counselor education programs seeking to utilize Internet searches for admissions and advising and how this might impact the admissions and advising process.

Recommendations

To recommend that one avoid the use of Facebook or SNS in general would certainly eliminate any ethical hazards of boundary crossings in counseling, supervision and counselor education. However, this solution is unrealistic, if not impossible. SNS are increasingly becoming embedded in the culture as a way to connect with others, both near and far (Reith, 2005). Therefore, the counseling field should aspire to identify methods to reduce rather than eliminate risks associated with using Facebook. Since the Internet is an integral part of students’ and faculty members’ lives, discussing the impact of using Facebook or other SNS is imperative (Lehavot, 2009). Students should be informed as soon as they begin the program about how social networking culture tends to blur personal, social and professional boundaries. Consequently, counseling students should be made aware of the impact that using Facebook could have on socializing with each other and on the development of professional behavior, especially as they begin seeing clients. Students also can be advised to do an Internet search on their own name to discover what personal information is available online to clients (Zur et al., 2009).

Counselor educators can encourage students to make better decisions about their use of Facebook. For instance, privacy settings on Facebook are dynamic and have become increasingly complex. Students should become educated about this complexity and the risks associated with each level. Students should be aware of risky behavior online, such as publishing photos of themselves in compromising situations. In addition, students should refrain from making inappropriate YouTube videos or communicating in ways that display unprofessional behavior. Counseling students should be advised to maintain all client discussions or references of client information within a context of face-to-face clinical supervision meetings, meetings with peer counselors, or prescribed dialogues with faculty members, and should not reference anything related to clients on Facebook. Furthermore, communicating with clients on Facebook, or any other social media outlet, should be discouraged in most cases; professional boundaries can be too easily crossed.

One encouraging implication that emerged from the administration of both surveys in our graduate counseling program was that it might be fairly easy to change students’ attitudes about Facebook privacy. Discussion of Facebook issues in an ethics class that occurred between the two surveys may explain why more students were using maximum privacy settings in the second administration sample. It also is possible that some students increased their privacy as a result of having participated in the first administration, suggesting that just making students aware of these issues impacts their Facebook practices. Students in the second administration increased privacy levels for photos, videos and information. Moreover, their primary goal was in preventing access by clients, suggesting their chief concern was in accordance of the ethical principle of “do no harm.” Further research is needed to determine how much exposure to Facebook issues, both ethical and technological, is necessary to help students ensure maximum privacy protection. Introducing discussion into a program’s ethics class and, as noted above, addressing the issue at the beginning of the program, would seem to be natural methods for achieving this goal. However, graduate counseling program leaders may choose a variety of learning experiences to help students deal with the Facebook privacy dilemmas, including ethics classes, introductory courses, practicums or special workshops, or they may infuse options throughout the curriculum.

One way to start enhancing student self-awareness is by exploring the meaning of transparency and how this language may be interpreted among the millennial generation as compared with other generations. Dialogues about the levels of self-disclosure revealed on Facebook as compared with face-to-face interactions could enhance students’ awareness. Students can brainstorm potential dilemmas that may emerge when participating on Facebook that may cross boundaries with other students, faculty or clients. Developing a proactive strategy when private information becomes unfortunately disclosed is another important topic to discuss with counseling students to enhance awareness. As Levahot (2009) has noted, the discovery by a student trainee that a client has accessed the trainee’s personal information can lead to a therapeutically valuable conversation with the client during treatment.

Counseling program leaders should carefully evaluate and establish a policy about investigating clients on Facebook without their informed consent. Viewing this information can place counseling students in very difficult dilemmas about appropriate professional behavior, particularly if a search reveals the potential or expectation of clients to cause harm to self or others. Students should be advised to remain up-to-date with emerging technologies their clients may use.

Counselor educators should be literate about Facebook and other technological advances that students may be using. Students are often more competent in these areas, and learning about how students engage on Facebook may open more productive communication about how to maintain appropriate professional boundaries. Counselor education program leaders have an additional responsibility of training agency supervisors on the potential benefits and risks of using SNS. Lehavot et al. (2010) and Taylor et al. (2010) noted that if supervisors seem dated and technologically challenged to supervisees, then supervisees will be less inclined to bring up the conversation when challenges arise. Consequently, supervisees may make poor decisions leading to unintentional boundary crossings with clients. Therefore, it is critical for supervisors to also be prepared to initiate a conversation about the use of Facebook.

Finally, counselor educator program leaders should develop policies regarding investigation of students’ Facebook pages by instructors, supervisors and admissions committees. Instructors and supervisors should initiate conversations with students about mutually participating on SNS such as Facebook. SNS sharing may lead to inappropriate disclosures of personal information that could compromise the faculty-student or supervisor-supervisee relationship. If admission committees intend to look at applicants’ Facebook pages, this policy must be included in departmental Web pages and printed materials describing admissions criteria. The most desirable approach is probably that admissions committees should refrain from using the Internet in general to examine a student’s fitness for a program.

The use of SNS has increased in the last three years, even among the baby-boom generation and Generation X (Hazlett, 2008). Counselor educators have an opportunity and responsibility to become familiar with this technology to protect counselors-in-training and the clients they serve. Additional research should be conducted on the current use of both SNS and privacy settings by counseling students. Our survey suggested that most of our millennial generation counseling students used Facebook; posted photos, videos and information they would not want clients to see; used various levels of privacy settings; and readily increased their privacy settings once exposed to information about Facebook risks. However, this was preliminary information with two small samples; more thorough research is needed in assessing the extent of Facebook use among counseling students, their familiarity and use of privacy settings, and best practices for teaching appropriate use of Facebook for counselors. In addition, determining the types of students who are less likely to establish appropriate privacy settings could be evaluated in order to target those students and reduce negative outcomes. Research could be conducted to evaluate the efficacy and inherent risks of using SNS in counselor education programs and in counseling as well.

Though the basic foundation of counseling has not changed drastically in recent years, current technologies have the potential to enhance or diminish therapy. The setting of counselor education programs is an excellent environment to explore benefits and risks associated with integrating new technologies. By doing so, counselors can remain informed about evolving technology to enhance their work with clients.

References

Allen, J. V., & Roberts, M. C. (2011). Critical incidents in the marriage of psychology and technology: A discussion of potential ethical issues in practice, education, and policy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(6), 433–439. doi:10.1037/a0025278

American Counseling Association (2005). ACA code of ethics. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/knowledge-center/ethics

Bergman, S. M., Fearrington, M. E., Davenport, S. W., & Bergman, J. Z. (2011). Millennials, narcissism, and social networking: What narcissists do on social networking sites and why. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(5) 706–711. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.022

Birky, I., & Collins, W. (2011). Facebook: Maintaining ethical practice in the cyberspace age. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 25(3), 193–203. doi:10.1080/87568225.2011.581922

Facebook (2013, July 16). Key facts [Newsroom]. Retrieved from http://www.facebook.com/press/info.php?statistics

Fogel, J., & Nehmad, E. (2009). Internet social network communities: Risk taking, trust, and privacy concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(1), 153–160. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2008.08.006

Harris, E., & Younggren, J. N. (2011). Risk management in the digital world. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(6), 412–418. doi:10.1037/a0025139.

Hazlett, B. (2008, June). Social networking statistics & trends [Slidshare]. Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/onehalfamazing/social-networking-statistics-and-trends-presentation

Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (2003). Millennials go to college [Executive Summary]. Retrieved from American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admission Offices and Life Course Associates website: http://eubie.com/millennials.pdf

Judd, R. G., & Johnston, L. B. (2012). Ethical consequences of using social network sites for students in professional social work programs. Journal of Social Work Values & Ethics, 9, 5–12.

Lehavot, K. (2009). “MySpace” or yours? The ethical dilemma of graduate students’ personal lives on the Internet. Ethics & Behavior, 19(2), 129–141. doi:10.1080/10508420902772728

Lehavot, K., Barnett, J. E., & Powers, D. (2010). Psychotherapy, professional relationships, and ethical considerations in the MySpace generation. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 41(2), 160–166. doi: 10.1037/a0018709

MacDonald, J., Sohn, S., & Ellis, P. (2010). Privacy, professionalism and Facebook: A dilemma for young doctors. Medical Education, 44(8), 805–813. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03720.x

Mehdizadeh, S. (2010). Self-presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(4), 357–364. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0257

Myers, S., Endres, M., Ruddy, M., & Zelikovsky, N. (2012). Psychology graduate training in the era of online social networking. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 6(1), 28–36. doi:10.1037/a0026388

Nosko, A., Wood, E., & Molema, S. (2010). All about me: Disclosure in online social networking profiles: The case of Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.012

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6. Retrieved from http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Reith, J. (2005). Understanding and appreciating the communication styles of the millennial generation. In Compelling Perspectives on Counseling: Vistas (pp. 321–324). Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/knowledge-center/vistas/vistas-2005

Salaway, G., Nelson, M. R., & Ellison, N. (2008). Social networking sites. In The ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2008. EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research, 8, 81–98. Retrieved from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ers0808/rs/ers0808w.pdf

Sandfort, M. H., & Haworth, J. G. (2002). Whassup? A glimpse into the attitudes and beliefs of the millennial generation. Journal of College and Character, 3(3). Retrieved from http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/jcc

Stewart, K. D., & Bernhardt, P. C. (2010). Comparing millennials to pre-1987 students and with one another. North American Journal of Psychology, 12, 579–602.

Taylor, L., McMinn, M. R., Bufford, R. K., & Chang, K. B. T. (2010). Psychologists’ attitudes and ethical concerns regarding the use of social networking web sites. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 41(2), 153–159. doi:10.1037/a0017996

Twenge, J. M. (2010). A review of empirical evidence on generational differences in work attitudes. Journal of Business Psychology, 25(2), 201–210. doi:10.1007/s10869-010-9165-6

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, S. M., Hoffman, B. J., & Lance, C. E. (2010). Generational differences in work values: Leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. Journal of Management, 36(5), 1117–1142. doi: 10.1177/0149206309352246

Zur, O., Williams, M. H., Lehavot, K., & Knapp, S. (2009). Psychotherapist self-disclosure and transparency in the Internet age. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 40(1), 22–30. doi:10.1037/a0014745

Leah Brew, NCC, is Chair and Associate Professor in the Department of Counseling at California State University, Fullerton (CSUF). Joseph M. Cervantes is a Professor and David Shepard is an Associate Professor, both in the Department of Counseling at CSUF. Correspondence can be addressed to Leah Brew, Department of Counseling, P.O. Box 6868, Fullerton, CA 92834-6868, lbrew@fullerton.edu.