Clark D. Ausloos, Madeline Clark, Hansori Jang, Tahani Dari, Stacey Diane Arañez Litam

Trans youth experience discrimination and marginalization in their homes, communities, and schools. Professional school counselors (PSCs) are positioned to support and advocate for trans youth as dictated by professional standards. However, an extensive review of literature revealed a lack of confidence and competence in counselors working with trans youth and their families. Further, there is a dearth of literature that addresses factors leading to increased school counselor competence with trans students. The current study uses a cross-sectional survey design to contribute to the extant literature and explore how PSCs in the United States work with students in the K–12 public school system. Results from multiple regression analyses indicate that PSCs who have had postgraduate training and report personal and professional experiences with trans students are more competent in working with trans students. Implications for PSCs and school counselor education programs are discussed.

Keywords: trans youth, school counselors, competence, counselor education, multiple regression analysis

Trans people experience an incongruence between their sex assigned at birth and their gender identity (GI; Ginicola et al., 2017; McBee, 2013). The term trans encompasses a wide range of gender-expansive identities, including trans (transgender), nonbinary (one who identifies outside the gender binary of male or female), genderqueer or gender-fluid (one who identifies with gender in a fluid, dynamic way) and agender (one who does not identify as having a gender). Trans people face pervasive discrimination and marginalization (Whitman & Han, 2017), leading to severe physical and mental health disparities, like depression, anxiety, and suicidality (James et al., 2016). In schools, trans students face 4 times higher rates of discrimination when compared with cisgender peers (Kosciw et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2021). Trans students are more vulnerable to mental health disorders, a lack of social support, and an increase in self-harm, suicidal ideations, and suicide attempts (Kosciw et al., 2020; Reisner et al., 2014), especially among transmale and nonbinary students (Toomey et al., 2018). These rates are increasing in national trends and are even higher among Black and Latinx trans students (Vance et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated barriers and inequities for trans students, with increasing health concerns, isolation, economic hardships, issues with housing, and limited access to essential clinical care (Burgess et al., 2021).

Increasingly, trans students face systemic legal barriers to their health and well-being (Wang et al., 2016). States including Arkansas, Idaho, Montana, South Dakota, and Tennessee have introduced bills that ban trans students from participating in sports that are congruent with their GI (Transgender Law Center, 2021). In April of 2021, Arkansas banned medical gender-affirming services to students under 18 years of age (American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU], 2021). New Hampshire’s House Bill 68 proposed adding gender-affirming treatments to the definition of child abuse (ACLU, 2021). Beyond political oppression, trans youth experience overt discrimination, verbal abuse, physical and sexual assault, and marginalization within their homes, schools, and places of employment (Human Rights Campaign [HRC], 2018; James et al., 2016). Trans youth additionally face disaffirming and incompetent teachers and medical professionals (Grant et al., 2011; James et al., 2016; Whitman & Han, 2017) and embedded systemic transmisia (the hatred of trans persons; Simmons University Library, 2019). Despite the pervasive mental health concerns faced by trans students (i.e., depression, anxiety, disordered eating, self-harm, suicide), professional school counselors (PSCs) continue to be ill equipped in supporting and advocating for this marginalized population within schools (Simons, 2021). Based upon an analysis of the extant body of research, we found that counselor education training programs lack rigor in working with trans students (O’Hara et al., 2013; Salpietro et al., 2019), counselor educators may hold biased views about trans students (Frank & Cannon, 2010), and there is an absence of quality professional development opportunities on trans issues (Salpietro et al., 2019; Shi & Doud, 2017). It is therefore of paramount importance for PSCs and counselor education programs to obtain a deeper understanding of how to better prepare for and support trans students in schools.

Professional School Counselors and Trans Students

PSCs focus on academic, career, and social-emotional growth and work as leaders alongside teachers, administration, families, and other stakeholders. PSCs are therefore well positioned to provide safety and support for trans students, promote change, and act as social justice advocates within schools (Bemak & Chung, 2008). The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) mandates that PSCs “promote affirmation, respect, and equal opportunity for all individuals regardless of . . . gender identity, or gender expression . . . and promote awareness of and education on issues related to LGBT students” (2016a, p. 37). PSCs who work with trans students may provide services through the Multitiered Systems of Support lens (MTSS; ASCA, 2019), through collaboration, by supporting school administration and staff (e.g., trainings, meetings, workshops), and through provision of direct student services (e.g., individual and group counseling, working with families). More specifically, PSCs advocate for and with students for name and pronoun changes within schools, trans-inclusive school policies, and increased visibility and normalization of trans people and issues.

ASCA (2016b) adopted a position that PSCs recognize that “the responsibility for determining a student’s gender identity rests with the student rather than outside confirmation from medical practitioners . . . or documentation of legal changes” (p. 64). It is clear that PSCs should possess knowledge and skills in working with and advocating for trans youth through a range of services at various levels and in coordination with other stakeholders in schools, all while respecting students’ autonomy and authenticity (ASCA, 2016a, 2016b, 2019; Bemak & Chung, 2008).

Counselor Education Programs

Although professional standards provide best practices (ALGBTIC LGBQQIA Competencies Taskforce, 2013; ASCA, 2016a), many PSCs never receive the training necessary to effectively serve trans students (Bidell, 2012; O’Hara et al., 2013; Salpietro et al., 2019). Salpietro and colleagues (2019) reported that counselor incompetence was related to a lack of rigorous training that attends to family systems, intersectionality, and medical issues through gender-affirming therapies (i.e., blockers, hormones, or surgeries). These researchers indicated a need for comprehensive, standardized, and thorough formal training (i.e., graduate school) and informal professional development opportunities. These findings are consistent with Shi and Doud (2017), who recommended PSCs specifically take advantage of conferences and workshops to supplement formal educational curricula. The Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) conducted a survey that reported about 81% of school mental health professionals received “little to no competency training in their graduate programs related to working with [trans] populations,” and about 74% of participants rated their graduate training programs as “fair or poor” in preparing them for work with trans students (GLSEN et al., 2019, p. xviii). GLSEN and other professional organizations additionally reported about two-thirds of school professionals do not feel prepared to work with trans students (GLSEN et al., 2019). Although there are some professional development opportunities, such as those offered through the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), the HRC, and the Society for Sexual, Affectional, Intersex, and Gender-Expansive Identities (SAIGE), there is still a lack of concrete training within graduate programs and through fieldwork experiences and an overall lack of accessible, professional trainings. There is a clear need for increased attention to trans issues in formal educational programs and professional development offerings.

Purpose of the Study and Research Questions

This study examines factors that contribute to PSC competence in working with trans students in K–12 public schools. We highlight the need for PSCs and counselor education training programs to better focus on and support trans students. More specifically, we examine the following PSC factors: (a) the PSC’s GI, (b) whether the PSC has received postgraduate training on trans issues or populations, (c) whether the PSC has worked with self-identified trans students, and (d) whether the PSC knows someone who identifies as trans outside of the school setting.

PSC Gender Identity

Researchers recommend that special attention is given within a category of interest (i.e., gender identity) to historically marginalized groups, encouraging counselor-researchers to view all samples “in terms of their particularity and to attend to diversity within samples” (Cole, 2009, p. 176). We were intentional in using PSC GI demographic factors in data analysis, attending to diversity among PSC gender identities, as research indicates there may be relationships between counselor GI, privilege and oppression, and multicultural counselor competence (Cole, 2009). Culturally competent counselors engage in self-reflection, examine their own biases and stereotypes, consider how their positions of privilege or oppression impact the therapeutic alliance, and deliver culturally responsive counseling interventions.

Postgraduate Training Addressing Trans Issues

Researchers note that graduate programs in counselor education are not adequately preparing school counseling students to work with trans students (Bidell, 2012; Farmer et al., 2013; Frank & Cannon, 2010; GLSEN et al., 2019; O’Hara et al., 2013) and that much of the awareness, knowledge, and skills gained in working with this population are result of counselors’ self-seeking professional trainings, education, and workshops that are focused on trans issues and students (Salpietro et al., 2019; Shi & Doud, 2017).

Professional Experiences With Trans Students

O’Hara and colleagues (2013) reported no significance on scores of competence in working with trans clients between counseling students who completed practicum or internship and those who did not. In the present study, our variable relates to PSCs who have already graduated, reflecting on their professional tenure as PSCs, and if these experiences provided opportunities to work with trans students.

Personal Relationships With Trans People

O’Hara and colleagues (2013) reported that participants in their study identified informal sources as necessary for gaining trans-affirming knowledge and skills, such as “exposure to or personally knowing someone who [is trans]” (p. 246). Research supports the concept that increasing affirming attitudes and mitigating negative attitudes and beliefs toward trans individuals can be accomplished by exposure and intentional engagement in fostering personal and professional relationships with trans people (Salpietro et al., 2019; Simons, 2021). In forming relationships with trans people, we can listen to and learn from the lived experiences of this community, examine our own biases, and position ourselves as supportive allies, personally and professionally.

Research Questions

With these factors in mind, the following research questions were identified:

- What is the relationship between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personally knowing someone who is trans) and levels of PSC self-perceived competence in working with trans students in schools?

- What is the relationship between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personally knowing someone who is trans) and PSC awareness in working with trans students in schools?

- What is the relationship between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personally knowing someone who is trans) and PSC knowledge in working with trans students in schools?

- What is the relationship between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personally knowing someone who is trans) and PSC skills in working with trans students in schools?

We hypothesized there would be a statistically significance difference (p > .05) between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personally knowing someone who is trans) and levels of PSC self-perceived competence in working with trans students in schools. More specifically, we hypothesized that cisfemale PSCs who have had postgraduate training on trans issues, who have worked with trans students, and who personally know someone who is trans, would report higher scores in measures of awareness, knowledge, skills, and overall competence. Cisgender (cis) refers to someone who experiences congruence between their sex assigned at birth and their GI. Research demonstrates that cismales may express more negative attitudes and hold restrictive views toward queer and trans people when compared with cisfemales (Landén & Innala, 2000; Norton & Herek, 2012).

Method

Participants

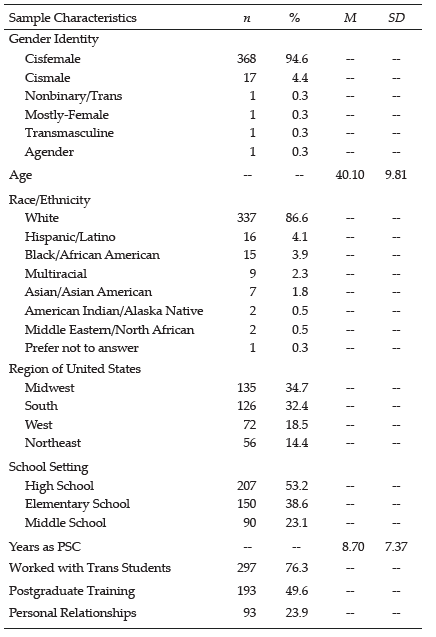

With an anticipated medium effect size of 0.15, a desired statistical power level of 0.95, and desired probability level of 0.05 (Israel, 2013), we determined an appropriate minimum sample size for the proposed study was 120 PSCs. Initially, 499 responses were recorded. Of those, 110 were incomplete or had missing data, yielding a total of 389 fully completed surveys. Participants in this study (N = 389) were PSCs with a valid school counseling license working in a public school setting, from kindergarten through 12th grade, in the United States. Participant demographic information can be found in Table 1.

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of Professional School Counselors (PSCs)

Procedures

For ease of use and accuracy of representation, we used probability sampling, more specifically, a simple random sample selection process (Creswell, 2013). Upon approval by the IRB, we posted a series of three recruitment letters (with 2 weeks between each posting) to PSCs through an online professional forum, ASCA Scene. We also posted our recruitment letter on ASCA Aspects, a monthly e-newsletter. Data were collected over a period of 6 weeks. PSCs who elected to participate were directed to the electronic informed consent document and the survey.

Instrumentation

Demographic Questionnaire

Participants completed a questionnaire with write-in options for both age and gender and forced-choice responses to gather racial-ethnic identity, years working as a licensed school counselor, the region in which they practiced, and grade levels in which the participants worked. Our four independent variables were collected through the demographic questionnaire. Participants indicated their experiences, if any, with trans students, experiences with postgraduate training on trans issues, and personal relationships with trans people.

Gender Identity Counselor Competency Scale

The Gender Identity Counselor Competency Scale (GICCS), a revised version of the Sexual Orientation Counselor Competency Scale (Bidell, 2005), was used to assess PSC competence, the dependent variable in the study. This is the instrument best suited for intended measurement of self-perceived competence (Bidell, 2012; O’Hara et al., 2013). Bidell (2005) developed the instrument based on Sue and colleagues’ (1992) research of multicultural counseling competencies, with the domains of attitudinal awareness, knowledge, and skills. Bidell (2005) reported the Cronbach’s alpha of .90, with subscale scores for internal consistency of .88 for the Awareness subscale, .71 for the Knowledge subscale, and .91 for the Skills subscale (Bidell, 2005, 2012). Test-retest reliability for the overall instrument was found to be .84, with .85 for the Awareness subscale, .84 for the Knowledge subscale, and .83 for the Skills subscale (Bidell, 2005). The GICCS is a 29-item self-report assessment on a 7-point Likert scale (where 1 is not at all true and 7 is totally true). Examples of questions include: “I have received adequate clinical training and supervision to counsel transgender clients” and “The lifestyle of a transgender client is unnatural or immoral” (O’Hara et al., 2013, p. 242). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .70, adequate for our analysis.

Awareness Subscale. The Awareness subscale consists of 10 items focused on counselors’ attitudinal awareness and prejudice about trans clients, including statements like “It would be best if my clients viewed a [cisgender] lifestyle as ideal” and “I think that my clients should accept some degree of conformity to traditional [gender] values” (Bidell, 2005, p. 273). Cronbach’s alpha for the Awareness subscale has been reported as .88 (Bidell, 2005) and was .89 in the present sample. Self-awareness and reflection are critical skills for counselors in examining deeply held biases and beliefs and in asking culturally responsive questions to strengthen the therapeutic alliance.

Knowledge Subscale. This subscale of the GICCS consists of eight items focused on counselors’ experiences and skills with trans clients, including statements like “I am aware that counselors frequently impose their values concerning [gender] upon [trans] clients” and “I am aware of institutional barriers that may inhibit [trans] clients from using mental health services” (Bidell, 2005, p. 273). Cronbach’s alpha for the Knowledge subscale was reported as .76 (Bidell, 2005), and was .73 in the present sample. Counselors who impose their own values on a client may cause rifts in the therapeutic alliance and could potentially even harm clients.

Skills Subscale. This subscale of the GICCS consists of 11 items focused on counselors’ experiences and skills with trans clients, including statements like “I have experience counseling [trans male] clients” and “I have received adequate clinical training and supervision to counsel [trans] clients” (Bidell, 2005, p. 273). Cronbach’s alpha for the Skills subscale was reported as .91 (Bidell, 2005) but was .75 in the present sample. Counselors working with trans students need to understand the importance of evolving language and terminologies; utilize affirmative, celebratory, and liberating counseling; and have knowledge of and connection to medical providers who support gender-affirming interventions.

Data Analysis Procedures

Data Cleaning

We first screened the data to ensure it was usable, reliable, and valid to proceed with statistical analyses. We continued data cleaning by coding the demographic variable of GI 1 through 4: cisfemale (1); cismale (2); nonbinary, trans, and/or genderqueer (3); and agender (4). Racial-ethnic identities were coded 1 through 10: American Indian or Alaska Native (1); Asian or Asian American (2); Black or African American (3); Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin (4); Middle Eastern or North African (5); Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (6); White (7); Some Other Race, Ethnicity, or Origin (8); Prefer Not to Answer (9); and Multiracial Identity (10). PSC location was also coded 1 through 6: Midwest (1), Northeast (2), South (3), West (4), Puerto Rico or other U.S. Territories (5), and Other (6). Last of the demographic variables, we coded PSC School Level 1 through 4: Elementary (1), Middle School (2), High School (3), and Other (4). In addition, we cleaned variables highlighting PSC professional and personal training and experiences with trans persons. The first variable was dummy coded to reflect participants who had worked with trans students (1; n = 297, 76.3%) and participants who indicated not working with trans students (0; n = 92, 23.7%). The next variable, PSC postgraduate training, was dummy coded for use in data analyses, reflecting those who indicated they engaged in postgraduate training (1; n = 193, 49.6%) and participants who indicated they did not engage in postgraduate training (0; n = 196, 50.4%). The final variable was dummy coded to reflect participants who know someone who is trans outside of the school setting (1; n = 93, 23.9%) and those participants who do not know someone who is trans outside of the school setting (0; n = 296, 76.1%). Per Bidell (2005), we started by reverse scoring coded GICCS items and created new variables for the GICCS total mean score, attitudinal Awareness, Skills, and Knowledge subscales.

Data Analysis

Post–data cleaning, we entered all the data from the demographic questionnaire and the GICCS into SPSS 26. To best answer the research questions, we used a series of standard multiple regression analyses to determine “the existence of a relationship and the extent to which variables are related, including statistical significance” (Sheperis et al., 2017, p. 131). Although multiple regression analysis can be used in prediction studies, it can also be used to determine how much of the variation in a dependent variable is explained by the independent variables, which is what we intended to measure (Johnson, 2001). Our independent variables were four categorical variables measured by our demographic questionnaire: PSC GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personal relationships with someone who is trans. Our dependent variable was school counselor competence in working with trans students, as measured by the GICCS (Bidell, 2005).

There are many assumptions to consider when conducting a multiple regression analysis, including (a) two or more continuous or categorical independent variables, (b) a continuous dependent variable, (c) independence of residuals (or observations), (d) linearity (both between dependent variable and each of the independent variables, and between the dependent variable and the independent variables as a whole), (e) homoscedasticity, (f) absence of multicollinearity, (g) no significant outliers, and (h) normally distributed residuals (Flatt & Jacobs, 2019). The research variables met assumptions (a) and (b) in conducting multiple regressions. In analyzing data in SPSS, independence of residuals was determined by using the Durbin-Watson statistic, which ranges in value from 0 to 4, with a value near 2 indicating no correlation between residuals. Assumption (c) was met, as the Durbin-Watson value found was 1.46 (Savin & White, 1977). Additionally, we plotted a scatterplot using variables, as well as a partial regression with each of the independent variables and the dependent variable, and observed linear relationships, attending to the assumptions of linearity (d; i.e., a linear relationship between dependent and independent variables) and homoscedasticity (e; i.e., residuals are equal for all values of the predicted dependent variable). Homoscedasticity was also assessed by visual inspection of a plot of studentized residuals versus unstandardized predicted values. To assess the absence of multicollinearity (f), we considered the variance inflation factors (VIF) indicated in the coefficients table (Flatt & Jacobs, 2019). We found VIF values ranging from 1.01 to 1.05, indicating an absence of multicollinearity (f). VIF is a measure of the amount of multicollinearity in a set of multiple regression variables (Flatt & Jacobs, 2019). We checked for unusual points (g): outliers, high leverage points, and highly influential points. We did identify a significant outlier (−3.10) in case number 133 by examining the range of standardized residuals ([−3.10 to 2.34]), which is outside the common cut-off range of three standard deviations (SD). We then inspected the studentized deleted residual values and found a value in case number 133 (−3.15), which falls outside the common cut-off range of 3 SD.

Additionally, we determined two cases of problematic leverage values that were greater than the safe value of 0.2 (0.36 and 0.23). The cases that violated assumptions were filtered out and the standard multiple regression analysis was run again. This time, the data did not violate assumptions (a) through (g). Last, we observed normally distributed standardized residuals (h). To determine if any cases were influential in the data, we examined the Cook’s Distance values, which ranged from .000 to .090. As there were no values above 1, there were no highly influential points. To answer the first research question (the relationship between PSC factors and levels of PSC self-perceived competence in working with trans students in schools as measured by total scores on the GICCS), we used a standard multiple regression analysis (Sheperis et al., 2017). To answer research questions 2 through 4, we conducted standard multiple regression analyses using the Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills subscales as the dependent variables, respectively.

Results

Correlations Between Variables of Interest

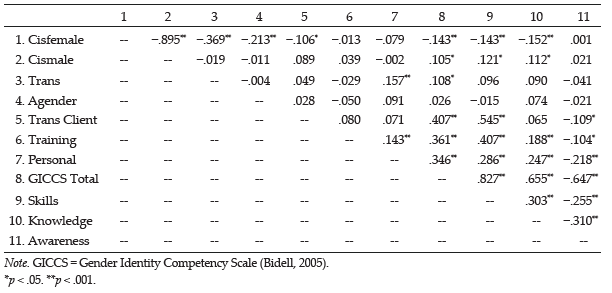

Prior to the regression analysis, we examined correlations between the variables: PSC GI (cisfemale, cismale, trans, agender), having worked with trans students, postgraduate training experiences, personally knowing someone who is trans, the GICCS Awareness subscale, the GICCS Skills subscale, the GICCS Knowledge subscale, and the GICCS total score. Correlations of variables of interest are found in Table 2. There were multiple significant correlations as determined by Pearson product moment correlations (r). The GICCS total score was significantly correlated with the Awareness subscale (r = −.65, p < .001), the Skills subscale (r = .83, p < .001), and the Knowledge subscale (r = .66, p < .001). The Awareness subscale was significantly correlated with the Skills subscale (r = −.26, p < .001) and the Knowledge subscale (r = .30, p < .001). The Knowledge subscale was also significantly correlated with the Skills subscale (r = .30, p < .001). In examining demographic factors, cisfemale GI was significantly correlated with cismale GI (r = −.90, p < .001), trans GI (r = −.37, p < .001), and agender GI (r = −.21, p < .001). Additionally, cisfemale GI was significantly correlated with having worked with trans students (r = −.12, p = .036), as well as the GICCS total score (r = −.14, p = .005), the Skills subscale (r = −.14, p = .005), and the Knowledge subscale (r = −.15, p = .003). Cismale GI was significantly correlated with the GICCS total score (r = .11, p = .038), the Skills subscale (r = .12, p = .017), and the Knowledge subscale (r = .11, p = .003). Trans GI was significantly correlated with personally knowing someone who is trans (r = .12, p = .002), as well as with the GICCS total score (r = .12, p = .034). Having worked with trans students was significantly correlated with the GICCS total score (r = .41, p <.001), the Skills subscale (r = .55, p < .001), and the Awareness subscale (r = −.11,

p = .032). Postgraduate training was significantly correlated with many variables, including personally knowing someone who is trans (r = .14, p = .005), and with the GICCS total scores (r = .36, p < .001), the Skills subscale (r = .41, p < .001), the Knowledge subscale (r = .19, p < .001), and the Awareness subscale (r = −.10, p = .040). Last, personally knowing someone who is trans was significantly correlated with the GICCS total score (r = .35, p < .001), the Skills subscale (r = .29, p < .001), the Knowledge subscale

(r = .25, p < .001), and the Awareness subscale (r = −.22, p < .001).

Table 2

Correlation Table for Variables of Interest

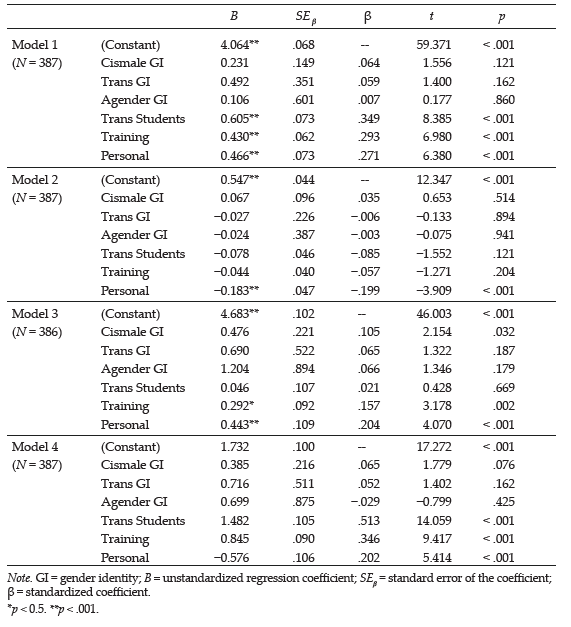

Model 1: PSC Competency

R² for the overall model was 35.2%, with an adjusted R² of 34.1%, a small to moderate size according to Cohen (1988). PSC factors significantly predicted levels of PSC self-perceived competence in working with trans students in schools, F(6, 381) = 34.430, p < .001. In examining beta weights (β), having worked with trans students received the strongest weight in the model (β = .35), followed by postgraduate training (β = .29) and personally knowing someone who is trans (β = .27). The variable with the most weight, having worked with trans students, had a structure coefficient (rs) of .67, and rs2 was 45.2%, meaning that of the 35.2% effect (R2), this variable accounts for 45.2% of the explained variance by itself. This shows that PSCs’ competence is increased by experiences with trans students, engaging in postgraduate trainings, and personally knowing someone who is trans. A summary of regression coefficients and standard errors can be found in Table 3.

Table 3

Multiple Linear Regression Analyses Exploring Professional School Counselor Competence

Model 2: PSC Awareness

R² for the overall model was 5.8%, with an adjusted R² of 6.2%, a very small effect size (Cohen, 1988). PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personal relationship with someone who is trans) significantly predicted awareness of PSC self-perceived competence in working with trans students in schools, F(6, 380) = 3.873, p = .001. Personally knowing someone who is trans was the only significant predictor in this model. We examined the regression coefficients and corresponding data (β = −.20, rs = −0.90, rs2 = 80%). Of the 5.8% effect (R²), personally knowing someone who is trans accounted for 80% of the explained variance by itself.

Model 3: PSC Knowledge

R² for the overall model was 10.3%, with an adjusted R² of 8.9%, a small effect size (Cohen, 1988). PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personal relationship with someone who is trans) significantly predicted knowledge of PSC self-perceived competence in working with trans students in schools, F(6, 379) = 7.257, p < .001. Personally knowing someone who is trans, postgraduate training, and cismale GI were all significant in this model. Personally knowing someone who is trans received the strongest weight in the model (β = .20, rs = .76), followed by postgraduate training (β = .16, rs = .58) and cismale GI (β = .12, rs = .35). After examining regression coefficients and corresponding data, we determined that of the 10.3% effect (R2), personally knowing someone who is trans accounted for 58.3% of the explained variance by itself. These findings demonstrate that PSC knowledge is strongly supported through fostering personal relationships with trans people.

Model 4: PSC Skills

R² for the overall model was 50.2%, with an adjusted R² of 49.5%, a medium effect size according to Cohen (1988). PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personal relationship with someone who is trans) significantly predicted self-perceived PSC skills in working with trans students in schools, F(6, 380) = 63.945, p < .001. Having worked with trans students, postgraduate training, and personally knowing someone who is trans were all significant in this model. Having worked with trans students received the strongest weight in the model (β = .51), followed by postgraduate training (β = .35) and personally knowing someone who is trans (β = .20). After examining regression coefficients and corresponding data, we determined that of the 50.2% effect (R2), having worked with trans students accounted for 79% of the explained variance by itself. Counselors can augment their skills by staying updated on appropriate language and terminologies and by fostering relationships with affirming providers and medical professionals in the community.

Discussion

The most salient finding in this model is that PSCs who worked with trans students were strongly positively correlated with GICCS total scores (r = .61, p < .001). This finding may indicate that increased exposure to trans students may subsequently increase competency in working with trans populations. Our research findings supplement existing studies that reported a relationship between affirming attitudes toward trans students and professional exposure to trans people (Salpietro et al., 2019; Simons, 2021). Avoidance of counseling trans students because of discomfort is not only unethical (ASCA, 2016b) but inhibits a PSC’s ability to develop their GI competence (Henry & Grubbs, 2017). Thus, it is imperative that PSCs receive opportunities to work with trans students (through practicum or internship experiences); consult with experienced, gender-affirming PSCs who have worked with trans students; and “expose themselves to published texts . . . films . . . [and] service-learning activities . . . to gain a better understanding of the experiences of [trans] persons” (O’Hara et al., 2013, p. 251). Additionally, PSCs must engage in constant self-reflection, introspection, and processing of biases and worldviews to provide culturally competent care to trans students.

Counseling Competence

Postgraduate training was moderately positively correlated with GICCS total score (r = .43, p < .001), indicating that additional postgraduate training in trans issues increased competence in the present sample (Model 1). This is consistent with extant literature, which demonstrated that PSCs who received postgraduate training were more competent in providing affirming services to trans students compared to PSCs who had not received the training (Salpietro et al., 2019; Shi & Doud, 2017). Finally, the presence of personal relationships with trans people was moderately positively correlated with GICCS total scores (r = .47, p < .001). These results support current literature in that PSCs who currently have or have had personal relationships with trans people were more competent in providing affirming services to trans students (GLSEN et al., 2019; O’Hara et al., 2013; Salpietro et al., 2019; Simons, 2021).

Awareness

We explored the relationship between PSC factors on the Awareness subscale of the GICCS in the second research question (Model 2). In examining coefficients for the model, having personal relationships with trans people is associated with a decrease in GICCS Awareness subscale scores, a weak, negative correlation (r = −.19, p = .001). This finding may indicate that people who did not know someone personally who is trans would score slightly higher on the Awareness subscale. These unexpected findings are contrary to existing research, which reported that engaging in personal relationships with trans people increased affirming attitudes and mitigated negative attitudes (Henry & Grubbs, 2017; Salpietro et al., 2019). Because of the lack of practical significance of PSC factors (i.e., GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personal relationship with someone who is trans) on the Awareness subscale, these results should be considered with caution.

Knowledge

In the third research question, we explored the relationship between PSC factors on the Knowledge subscale of the GICCS (Model 3). In examining coefficients for the model, PSC cisgender male GI was moderately positively correlated with the Knowledge subscale scores (r = .476, p = .032), indicating that cismale PSCs scored moderately higher on the Knowledge subscale when compared with other PSC gender identities in the present sample. One possible explanation is the present study’s sample of cisfemales (N = 368, 94.6%) and cismales (N = 17, 4.4%). Within this sample, the ages of the cismale PSCs could reflect a time in which counselor education programs increased attention to diversity, whereas this was not always a main tenet in training among older PSCs (who may be more represented by cisfemale PSCs in this sample [Bemak & Chung, 2008]). Presently, the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2015) requires accredited counselor education programs to deliver a counseling curriculum that includes specific attention to social and cultural diversity, an essential foundation of competent counselors. Additionally, PSC postgraduate training was weakly positively correlated with Knowledge subscale scores (r = .292, p = .002), which supports the literature that PSCs who engage in professional training opportunities outside of graduate school increase their knowledge of trans students and trans issues (Salpietro et al., 2019; Shi & Doud, 2017). Having personal experiences with trans people was moderately positively correlated with Knowledge subscale scores (r = .434, p < .001), indicating that those PSCs who personally knew a trans person felt more confident and competent in their knowledge about trans students and issues. This supports current literature (GLSEN et al., 2019; Henry & Grubbs, 2017; O’Hara et al., 2013; Salpietro et al., 2019) showing that PSCs who intentionally engaged in and fostered personal relationships with trans people reported greater competence.

Skills

Finally, we explored the relationship between PSC factors (GI, postgraduate training, PSC work with trans students, and PSC personal relationship with someone who is trans) on the Skills subscale of the GICCS in research question 4 (Model 4). In examining coefficients for the model, having worked with trans students was moderately positively correlated with Skills subscale scores (r = .545, p < .001), which may indicate that PSCs who work with trans students will be more likely to employ the necessary supports to ensure growth in “academic, career and social/emotional development” (ASCA, 2016a, para. 1). This is supported by literature in which researchers reported number of students worked with and “interpersonal contact” (personal exposure) as positive predictors of affirmative counselor competence (Bidell, 2012; Farmer et al., 2013). PSCs play an essential role in advocating for and removing barriers for trans students, which improves trans students’ well-being, academic success, and interpersonal growth. PSC postgraduate training was strongly positively correlated with Skills subscale scores (r = .845, p < .001), which may indicate that PSCs who engage in professional development opportunities and trainings gain essential skills for working with trans students. This finding is consistent with extant research that reported the importance of postgraduate training and professional development opportunities on trans topics (Bidell, 2012; Frank & Cannon, 2010; GLSEN et al., 2019; O’Hara et al., 2013). Finally, knowing someone personally who is trans was moderately positively correlated with Skills subscale scores (r = .576, p < .000), which may mean that having familiarity and exposure to trans folks increases PSC’s self-perceived skills.

Implications

Professional School Counselors

Based on the results of our study, PSCs who worked with trans students reported significantly higher scores of overall self-perceived competence compared to PSCs who had not worked with trans students. Specifically, our results indicate a link between PSCs having worked with trans students and higher scores on the Knowledge subscale. The GICCS Knowledge subscale addresses PSC knowledge of trans psychosocial issues (Bidell, 2005). This supports the idea that PSCs who work with self-identified trans students have a deeper understanding of the social and psychological challenges faced by trans people, and these experiences increase their comfort in working with trans students. All PSCs are required to protect and support the well-being of queer and trans youth and must have foundational knowledge and familiarity with trans students and issues (ASCA, 2016b). PSCs must attend professional development offerings on trans issues, and counselor education programs must provide increased time and attention to discussing trans issues, clients, and students.

PSC postgraduate training experiences are significantly linked to an overall increase in scores on the GICCS, indicating that PSC postgraduate experiences contribute to PSCs feeling more confident and competent in working with trans students. We conceptualized postgraduate training experiences as any training or education focused on trans persons or issues that a PSC received after their graduate program education. These results indicate that to increase competence and provide affirming, ethical care to trans students, PSCs should engage in some type of postgraduate training on trans issues and students, especially if they are unfamiliar with trans issues. These results are congruent with other studies, which found no significance in the relationship between groups on the Awareness subscale, but significant relationships on both the Knowledge and Skills subscales, with professional training experiences (Bidell, 2005; Rutter et al., 2008). PSCs are therefore encouraged to join professional organizations that promote best practices in working with trans students, like WPATH, the HRC, and SAIGE, as these organizations often offer professional development opportunities. It is essential that PSCs seek out trainings that are specific to trans students and issues, attend to unique psychosocial barriers, outline best practices, describe social/medical affirming care, and provide an overview of ethical and legal issues.

Of all the variables in the present study, PSCs knowing someone who identifies as trans was significantly linked to an increase in overall confidence and competence, as well as a significant increase in both Knowledge and Skills. Surprisingly, PSCs who indicated they did not know someone who identified as trans scored slightly higher on the Awareness subscale scores when compared with PSCs who did. The Awareness subscale of the GICCS examines a PSC’s self-awareness of anti-trans biases and stigmatization (Bidell, 2005). This result is contrary to existing research, which reported that engaging in personal relationships with trans folks increased affirming attitudes and mitigated negative attitudes (Henry & Grubbs, 2017; Salpietro et al., 2019). The link between a PSC personally knowing someone who is trans and a counselor’s competence in knowledge and skills supports extant literature that speaks to the importance of non–work-related experiences with trans people (e.g., personal, familial, social) and an increase in counselors’ competence in working with trans students (Whitman & Han, 2017). It is important that PSCs continue to monitor and increase their personal engagement with trans communities, as this significantly links to PSCs feeling more comfortable and more competent in working with trans students. Personal experiences may include fostering connections to trans family members, friends, and trans people through community organizations (GLSEN et al., 2019; Henry & Grubbs, 2017; Salpietro et al., 2019). Given the findings of our study, it is important for PSCs to connect to affirming resources in their communities. PSCs may consider exploring the multitude of resources offered by GLAAD (glaad.org), the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE; transequality.org), and PFLAG (pflag.org).

Counselor Education Programs

Our results indicate that those PSCs who engage in professional development are more competent than those who do not. Professional counseling organizations (i.e., ASCA) and accrediting bodies (i.e., CACREP) mandate that school counselors-in-training receive formal training in social and cultural diversity (F.2; CACREP, 2015), including multicultural counseling competencies (F.2.c.; CACREP, 2015), and deliver a comprehensive “counseling program that advocates for and affirms all students . . . including . . . gender, gender identity and expression” (ASCA, 2016a, para. 3). Although current standards call for the inclusion of LGBTQIA+ issues within counselor education curricula, the reality is that counselors-in-training receive minimal training in working with trans and gender-expansive students (Frank & Cannon, 2010; O’Hara et al., 2013). It is imperative that CE programs and counselor educators broaden the scope of learning about trans issues, going beyond the minimal requirements (CACREP, 2015) and providing depth and rigor in gender-related coursework in diversity courses. This research supports other emergent literature which recommends that counselor education programs offer additional, specific courses related to affectional and sexual identities (LGBQ+), and gender-expansive identities (trans, nonbinary), as covering specific issues and populations increases counselor competency (Bidell, 2012; Henry & Grubbs, 2017; O’Hara et al., 2013, Salpietro et al., 2019).

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Limitations of the study include potential social desirability factors and inattentive responding, which may influence the quality of the data, as the study relied on self-report. Particularly, we note that the findings of higher self-awareness for PSCs who did not know someone who identified as trans could be a potential result of social desirability factors. Although the present study confirms that certain professional and personal factors contribute to PSCs increased competence in working with trans students in the present sample, additional research should be conducted. Also, much of our sample consisted of White ciswomen and, therefore, we caution readers about generalizing these findings to school counselors outside of those identities. The revised GICCS has not been used in many studies focusing on trans populations and additional research is needed to assess its validity with PSCs and trans youth (Bidell, 2005, 2012). Future researchers should consider additive studies that more deeply examine the types of professional development opportunities that promote PSC competency, including length, location, modality, themes, and expertise of presenter(s). Knowing these factors is important for crafting and delivering meaningful and competence-fostering professional development opportunities for PSCs. Also, future studies should examine unique nuances within trans groups, such as nonbinary and gender-fluid students (Toomey et al., 2018), and highlight the voices of trans students of color (Vance et al., 2021). Finally, future studies should also include demographic factors like religiosity and spirituality and their correlation to PSC GI competence, building on the work of Farmer and colleagues (2013).

Conclusion

This study highlights the need for increased attention to trans issues in many domains: among PSCs, within school counseling training programs, and in existing professional development offerings. ASCA mandates that PSCs be advocates for trans students, but there is a lack of attention to trans issues in school counseling training programs, leading PSCs to feel unprepared and to seek outside professional development offerings. The study also highlights the importance of building community and connections with trans people in and outside of professional settings, leading to increased PSC competence in professional settings. PSCs should continue to learn about the evolving language, trends, and needs of the trans community, ideally from those who are part of that community. Additionally, PSCs should engage with and use resources from professional trans-affirming organizations, such as WPATH, HRC, SAIGE, GLAAD, NCTE, and PFLAG.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

ALGBTIC LGBQQIA Competencies Taskforce. (2013). Association for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues in counseling competencies for counseling with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Queer, Questioning, Intersex, and Ally individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 7(1), 2–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2013.755444

American Civil Liberties Union. (2021). Legislation affecting LGBTQ rights across the country 2021.

https://www.aclu.org/legislation-affecting-lgbt-rights-across-country

American School Counselor Association. (2016a). ASCA ethical standards for school counselors. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/f041cbd0-7004-47a5-ba01-3a5d657c6743/Ethical-Standards.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2016b). The school counselor and transgender/gender-nonconforming youth. https://schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-Transgender-Gender-noncon

American School Counselor Association. (2019). ASCA school counselor professional standards & competencies.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/a8d59c2c-51de-4ec3-a565-a3235f3b93c3/SC-Competencies.pdf

Bemak, F., & Chung, R. C.-Y. (2008). New professional roles and advocacy strategies for school counselors: A multicultural/social justice perspective to move beyond the nice counselor syndrome. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(3), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00522.x

Bidell, M. P. (2005). The Sexual Orientation Counselor Competency Scale: Assessing attitudes, skills, and knowledge of counselors working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Journal of Counselor Education and Supervision, 44(4), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb01755.x

Bidell, M. P. (2012). Examining school counseling students’ multicultural and sexual orientation competencies through a cross-specialization comparison. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90(2), 200–207.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-6676.2012.00025.x

Burgess, C. M., Batchelder, A. W., Sloan, C. A., Ieong, M., & Streed, C. G., Jr. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on transgender and gender diverse health care. The Lancet, 9(11), 729–731.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00266-7

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed). Routledge.

Cole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64(3), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014564

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

Farmer, L. B., Welfare, L. E., & Burge, P. L. (2013). Counselor competence with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients: Differences among practice settings. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 41(4), 194–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2013.00036.x

Flatt, C., & Jacobs, R. L. (2019). Principle assumptions of regression analysis: Testing, techniques, and statistical reporting of imperfect data sets. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 21(4), 484–502.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422319869915

Frank, D. A., II, & Cannon, E. P. (2010). Queer theory as pedagogy in counselor education: A framework for diversity training. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 4(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538600903552731

Ginicola, M. M., Smith, C., & Filmore, J. M. (2017). Affirmative counseling with LGBTQI+ people. American Counseling Association.

Gay, Lesbian, & Straight Education Network, American School Counselor Association, American Council for School Social Work, & School Social Work Association of America. (2019). Supporting safe and healthy schools for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer students: A national survey of school counselors, social workers, and psychologists. GLSEN. https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/Supporting_Saf

e_and_Healthy_Schools_%20Mental_Health_Professionals_2019.pdf

Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J. L., & Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf

Henry, H. L., & Grubbs, L. (2017). Best practices for school counselors working with transgender students. In G. R. Walz & J. C. Bleuer (Eds), Ideas and research you can use: VISTAS 2016. https://bit.ly/HenryTrans2017

Human Rights Campaign. (2018). 2018 LGBTQ Youth Report. https://bit.ly/HRCLGBTQReport

Israel, G. D. (2013). Determining sample size. Agricultural Education and Communication Department, UF/IFAS Extension. https://bit.ly/Israel2013SampleSize

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/sites/default/file

s/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

Johnson, B. (2001). Toward a new classification of nonexperimental quantitative research. Educational Researcher, 30(2), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X030002003

Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., Truong, N. L., & Zongrone, A. D. (2020). The 2019 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN. https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/NSCS-2019-Full-Report_0.pdf

Landén, M., & Innala, S. (2000). Attitudes toward transsexualism in a Swedish national survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29(4), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1001970521182

McBee, C. (2013). Towards a more affirming perspective: Contemporary psychodynamic practice with trans* and gender non-conforming individuals. The University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration (Org.) Advocates’ Forum: The University of Chicago, 37–52. The University of Chicago. https://crownschool.uchicago.edu/contemporary-psychodynamic-trans-and-gender-non-conforming-individuals

Norton, A. T., & Herek, G. M. (2012). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward transgender people: Findings from a national probability sample of U.S. adults. Sex Roles, 68, 738–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0110-6

O’Hara, C., Dispenza, F., Brack, G., & Blood, R. A. C. (2013). The preparedness of counselors in training to work with transgender clients: A mixed methods investigation. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 7(3), 236–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2013.812929

Reisner, S. L., White, J. M., Dunham, E. E., Heflin, K., Begenyi, J., Cahill, S., & Project VOICE Team. (2014). Discrimination and health in Massachusetts: A statewide survey of transgender and gender nonconforming adults. The Fenway Institute. http://fenwayfocus.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/The-Fenway-Institut

e-MTPC-Project-VOICE-Report-July-2014.pdf

Rutter, P. A., Estrada, D., Ferguson, L. K., & Diggs, G. A. (2008). Sexual orientation and counselor competency: The impact of training on enhancing awareness, knowledge and skills. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 2(2), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538600802125472

Salpietro, L., Ausloos, C., & Clark, M. (2019). Cisgender professional counselors’ experiences with trans* clients. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 13(3), 198–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2019.1627975

Savin, N. E., & White, K. J. (1977). The Durbin-Watson Test for serial correlation with extreme sample sizes or many regressors. Econometrica, 45(8), 1989–1996. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914122

Sheperis, C. J., Young, J. S., & Daniels, M. H. (2017). Counseling research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Shi, Q., & Doud, S. (2017). An examination of school counselors’ competency working with lesbian, gay and bisexual and transgender (LGBT) Students. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 11(1), 2–17.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2017.1273165

Simmons University Library. (2019). Anti-Oppression: Anti-Transmisia. https://simmons.libguides.com/anti-opp

ression/anti-transmisia

Simons, J. D. (2021). School counselor advocacy for gender minority students. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0248022. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248022

Sue, D. W., Arredondo, P., & McDavis, R. J. (1992). Multicultural counseling competencies and standards: A call to the profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 70(4), 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb01642.x

Toomey, R. B., Syvertsen, A. K., & Shramko, M. (2018). Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics, 142(4), e20174218. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4218

Transgender Law Center. (2021). National equality map. https://transgenderlawcenter.org/equalitymap

Vance, S. R., Jr., Boyer, C. B., Glidden, D. V., & Sevelius, J. (2021). Mental health and psychosocial risk and protective factors among Black and Latinx transgender youth compared with peers. JAMA Network Open, 4(3), e213256. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3256

Wang, T., Solomon, D., Durso, L. E., McBride, S., & Cahill, S. (2016). State anti-transgender bathroom bills threaten transgender people’s health and participation in public life: Policy brief. The Fenway Institute and Center for American Progress. https://fenwayhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/COM-2485-Transgender-Bathroom-Bill-Brief_v8-pages.pdf

Whitman, C. N., & Han, H. (2017). Clinician competencies: Strengths and limitations for work with transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) clients. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(2), 154–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1249818

Williams, A. J., Jones, C., Arcelus, J., Townsend, E., Lazaridou, A., & Michail, M. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of victimisation and mental health prevalence among LGBTQ+ young people with experiences of self-harm and suicide. PLoS ONE, 16(1), e0245268.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245268

Clark D. Ausloos, PhD, NCC, LPC, LPSC, is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Denver. Madeline Clark, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC (VA), LPCC (OH), is an associate professor at the University of Toledo. Hansori Jang, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. Tahani Dari, PhD, NCC, LPC (MI), LPSC, is an assistant professor at the University of Toledo. Stacey Diane Arañez Litam, PhD, NCC, CCMHC, LPCC-S, is an assistant professor at Cleveland State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Clark D. Ausloos, 15578 John F. McCarthy Way, Perrysburg, OH 43551, clark.ausloos@du.edu.