Susan A. Adams, Alice Vasquez, Mindy Prengler

Teaching basic skills to beginning counseling students can be an overwhelming experience. In each therapy session, students bring their own human qualities and life experiences that have shaped them as individuals. Trainees must understand that their needs, motivations, values and personality traits can either enhance or interfere with their counselor effectiveness. Cognitive mapping can help expand students’ awareness while building the foundation of their counseling skills because it involves practical integration of learning attributes and prior knowledge into a new situation. Through the use of simple graphic visual learning tools, students can successfully incorporate basic skills into their development as counselors in an attempt to enable a positive initial learning experience that does not overwhelm them with the nuances and complexities of advanced counselor development.

Keywords: counseling students, basic skills, counseling formula, cognitive mapping, graphic visual learning tools

Why does change occur in therapy? Theorists have attempted to answer this question over the decades. Certainly the starting place is to focus on the importance of the therapeutic relationship, which is “central and foundational to therapeutic growth” (Slattery & Park, 2011, p. 235). Specifically, the outcome of counseling involves a connection between the counselor and client that begins with warmth, empathy, respect and genuineness (Chang, Scott, & Decker, 2009; Flaskas, 2004; McClam & Woodside, 2010; Smith, Thomas, & Jackson, 2004).

Rogers (1951, 1957, 1958) discussed his ideas about unconditional positive regard, congruence and empathy as basic key factors in the development of a therapeutic relationship. Moursund and Kenny (2002) summarized Lazarus’ perspective and proposed that establishing the therapeutic relationship is the most important skill for clinicians, and involves a connection between the counselor and the client. Each influences the other by bringing individual strengths, knowledge of the situation, life experiences, as well as their own personal values and beliefs. “The therapeutic relationship is viewed as both a precondition of change and a process of change” (Prochaska & Norcross, 2003, p. 492). The purpose of this article is to explore one method of breaking down basic counseling skills into a manageable counseling formula in order to enable a positive initial learning experience for students without overwhelming them with the nuances and complexities of advanced counselor development.

Challenges of Mastering Basic Skills

Initially, when introduced to counseling basic skills from a written textbook, students can find acquiring this knowledge to be challenging. Without prior experience, the challenge may intensify and become daunting when successful academic progress becomes an expectation defined by mastery of clearly defined basic skills. Counseling students struggle to appropriately apply these skills, while linked with timing and delivery.

Counseling is a unique experience that is different from daily communications in social interactions. As counselors-in-training learn the art of counseling, they become aware of the necessity of using their skills to empower their clients to set appropriate goals. Often empowerment, a concept that focuses on clients’ ability to choose their own solutions in life situations and issues, is a lofty ideal that is difficult to define. Even the definition of empowerment is ever-evolving (Asimakopoulou, Gilbert, Newton, & Scrambler, 2012). Empowerment’s overarching theme further contributes to the complexities of the learning process for beginning students (Hill, 2005).

While no one would argue the importance of empowerment or the significance of the therapeutic relationship, it also is critical that beginning students master many interpersonal skills while learning to observe, effectively attend to, and play an interpersonal role in shaping and guiding the counseling session (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2001; Chang et al., 2009; Jacobs, 1994; Jacobs, Masson, Harvill, & Schimmel, 2012; Meier & Davis, 2011). In fact, the second belief of Jacob’s impact therapy is that “people don’t mind being led if they are led well” (1994, p. 8). Therefore, it becomes imperative that educators incorporate logical process teaching methods in order to simplify this initial learning process, and cognitive mapping pedagogy provides that logical process.

Cognitive Mapping Pedagogy

A concept map is “a schematic device for representing a set of concepts and meanings embedded in a framework of propositions” (Novak & Gowin, 1984, p. 15). According to Akinsanya & Williams (2004), cognitive mapping provides an interactive teaching environment incorporating communication, group dynamics and motivation. Concept maps promote awareness of the roles of relationships within the categories and are ideal for the measurement of students’ learning (Akinsanya & Williams, 2004). Nurses have been successful in the utilization of cognitive mapping in order to build upon new concepts and incorporate these new concepts into their working framework. The cognitive mapping strategy ensures that both the curriculum and learning processes align with the nurses’ practical application of patient care (Akinsanya & Williams, 2004).

Counselor educators, in an initial basic skills course, focus on improving how students understand their basic counseling skills and navigate their individual learning styles. The counselor educator’s goal is for students to become successful counselors. Creating a classroom of trust filled with simplistic, graphic learning tools can generate a safe learning environment and reduce anxiety. “The reduction of anxiety removes unnecessary barriers to learning and to performing complex, multidimensional, and multisensory tasks, of which counseling is a prime example” (McAuliffe & Eriksen, 2002, p. 50).

Furthermore, by using graphic learning tools, the counselor educator links what is in his or her mind with what is in the student counselor’s mind in order to enable the student counselor to effectively utilize past experiences with new knowledge. In other words, cognitive mapping helps graphically relate a foreign concept to prior learning experience by using experiential links between old knowledge and new learning. These experiential links create a deeper level of learning (Akinsanya & Williams, 2004). By using cognitive mapping in this research, the counselor educator forms a visual representation of the links of communication between student counselor and client. The cognitive mapping visual representation can track student counselor awareness with the communication of the client.

Cognitive mapping helps the student understand the structure of knowledge by providing a process for acquiring, storing and using information. This process helps students think more effectively by creating a pictorial view of their ideas and concepts and how these are interrelated (Kostovich, Poradzisz, Wood, & O’Brien, 2007). Svinicki and McKeachie (2011) explained that visual cues serve as points of reference. Using a diagram or other graphic representative, in addition to an oral presentation, serves as a point of reference for visual cues to enhance learning opportunities within cognitive mapping, which in turn gives the students a visual representation that supports learning. According to Veletsianos (2010), students have learning expectations before the learning process begins. Both learning preferences and personality style are incorporated into the students’ learning process. As Veletsianos discovered, when given a graphic such as a cognitive map, the material is organized in a way that influences students’ “expectations, impressions, and learning” (2010, p. 583). The combination of human interaction with a visual graphic as part of the classroom experience allows the student to expect that learning is about to occur.

Concept mapping helps the counselor educator track the progress of student learning by allowing the professor to track what the student does not understand. The role that the common language plays in concept mapping allows the counselor educator to correct the links that might confuse the student. Cognitive mapping is not only a visual tool, but also adds verbal and kinesthetic tools to role playing in initial counselor training courses.

According to Henriksen and Trusty (2005), development of specific counselor education pedagogy also must incorporate diversity. Cognitive mapping is a schematic tool that appeals to the diverse learner since it provides a progressive visual that counseling students can follow and understand (Hill, 2005). Cognitive mapping is diverse in itself, as it appeals to a variety of learning styles, culturally diverse students and adult learners. Students have consistently given feedback that this method of teaching has simplified both learning and understanding how the map fits together within the therapeutic process. The following examples provide a reflection of students’ perspective.

Student Feedback

Example 1. Typical students learn systematically as they acquire practice and understand how to apply the counseling formula to what is happening in their sessions. One of the current authors was taught the counseling formula during her first clinical graduate course and describes her experience this way:

For me, I could plug in where my parts were and back off on parts where the client needs to do his or her work. It made me feel more confident as I entered my second tape recording and verbatim assignment because I knew that my basic skills of reflection of content, feelings, and meaning would get me where I needed to go with my client. This is where he or she could begin to gain insight into their experience, and begin to have the option to make optimal changes in life.

Example 2. Struggling students are those trying to connect the dots until they apply the cognitive mapping formula to what is happening when working through their second tape. This student defines his experience and the insights he gained as follows:

When I was introduced to the counseling formula, I thought it was definitely something useful, but not something I fully grasped at the time. Before that point, everything I had learned had been more complex, and the formula seemed almost too simple. How could reflection of feeling and content lead to reflection of meaning? Also, how is the client able to know or receive the response the way the counselor wants him or her to? I was confused because the formula seemed so black and white—or at least that is how I made it out to be.

After our second counseling tape was recorded, our transcription was scored. To my surprise, I did not do well. I met with my professor who had taught me the formula at the beginning of the semester. Instead of her telling me exactly where in the formula I had gone wrong, we discussed what elements I was missing during the session and what I focused on too much. As we discussed my struggles, I kept the formula in mind. As we talked, I realized I had forgotten one of my key formula elements; I was stricken by the realization that I did not understand how to make meaning of this seemingly simplified equation. In no way is the equation simple as it is up to the counselor to do his or her part so the client can do theirs. This light bulb moment was a key part of my learning experience during my first basic clinical course.

Counselor Educators

A counselor educator developing a counselor training program that is culturally diverse can use cognitive mapping as a teaching tool to meet the needs of culturally diverse learners. Cognitive mapping provides counselor educators with a multicultural pedagogy which incorporates the race and ethnicity of their students during counselor training (Henriksen & Trusty, 2005). As a multicultural pedagogy, it further reduces cultural clashing by providing common, visual language (Dansereau & Dees, 2002). The cognitive map becomes the students’ tool for spoken language, as it parallels verbal thought and expression by breaking down complex thoughts into visual expression. Cognitive mapping, although an effective tool, is more likely to be effective with African Americans and Mexican Americans than Caucasians (Van Velsor & Cox, 2000). The cognitive map represents knowledge graphically; therefore, students whose initial language is not English can pictorially grasp the concepts with more ease.

Just as culturally diverse students can learn using cognitive mapping, adult learners also can benefit from using this schematic tool. According to Hill (2005), cognitive mapping or concept mapping (as she refers to it) is a learning tool that is well suited to the adult learner due to greater accumulation of experiences. Adult students find cognitive mapping useful in organizing their ideas, retaining information and relating content material to other knowledge. When processing content material using cognitive mapping, meaningful learning occurs; the adult student learner engages complex cognitive structures within the brain integrating it with existing knowledge.

Student Feedback

Example 3. A student who is a mature adult learner and whose second language is English shared that she learns better visually and that cognitive mapping helped her comprehend the content as she followed graphically what the counselor educator was explaining. She stated the following:

I am an older Hispanic student and English is my second language. Although I have excellent command of the English language, I still find myself translating from English to Spanish to better understand what the professor is saying. When the professor taught us the counseling formula in class, the methodology of how the counseling process works made sense to me. I was able to visualize in my head how the counseling process functions. From that point on, I was able to grasp the concept of what I need to do as a counselor to get clients to move toward change.

Theory & Basic Skills

The counseling process influences the outcome of counseling. This simple statement can easily lead to a developmental crisis as counseling students struggle with skill acquisition. According to Meier and Davis (2011), “To master process, beginning counselors must develop a repertoire of helping skills as well as a theory of counseling that directs their application” (p. 1). Most counseling programs separate acquisition of basic skills from theoretical knowledge. Gaining these skills can be like learning a foreign language—learned patterns of human interaction change as students assume their counselor identity and acquire new counseling skills.

Certain critical skills are absent from this formula because, due to prior knowledge and experience, students easily understand them. For example, when given the opportunity to talk about attending skills, most students can easily identify basic posture, facial expressions and space limitations with reasonable accuracy. Minimal encouragers and questioning are both necessary skills that have a useful purpose in the counseling session; nevertheless, students usually have mastered these in normal daily conversation. Therefore, both minimal encouragers and questioning must receive great attention in order to substantially reduce and manage their utilization and avoid hindering or distracting from the effectiveness of a counseling session.

A Cognitive Mapping Formula

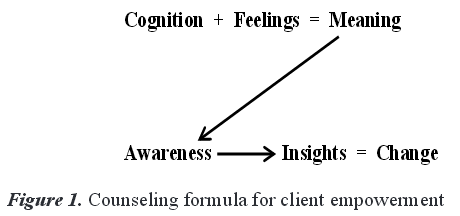

The creation of a cognitive mapping formula for counseling was designed to graphically depict the counseling process utilized in the therapeutic process. The formula and the inclusion of certain basic skills illustrate the concept of client empowerment so that clients can take personal responsibility for their actions and make desired changes. The counseling formula works as follows: Cognition (C) plus feelings (F) equals meaning (M), which leads to awareness (A), which promotes insights (I), which facilitates change (see Figure 1).

Through reflections of cognition, feeling and meaning, counselors help clients explore their world and determine what will be effective and ineffective. These reflections encourage exploration on multiple levels. Deeper levels of exploration are achieved through reflection of feeling and meaning so that clients connect what is happening in their heads (cognitions) and what is happening emotionally (feelings), therefore ultimately understanding their experience (meaning). Through counselors’ proper application of the top line of the cognitive mapping equation, clients begin to understand that their situation is solvable if they are willing to take personal responsibility for the change, as reflected in the bottom line of the equation. In other words, change occurs as a result of clients’ personal commitment. The concept of universality and the inclusion of all basic skills are part of all theoretical applications.

The didactic application of the cognitive mapping, as seen in Figure 1, tracks how the counselor shapes the session in classroom role plays. The equation shows how the session crosslinks and builds. The counselor influences the session through the choices the counselor makes to reflect feeling, meaning or cognition. Each counseling session looks different, but all sessions need balance in order for sessions to flow.

Subsumed within this simplistic graphic are additional important counseling skills. Paraphrasing and summarization contain elements of cognition, feeling and meaning, and tend to center the client in the content of these elements. While using content elements is not negative, doing so sparingly prevents clients from intellectualizing their issues and avoiding taking responsibility for their desired change. Silence is located between the elements of cognition, feeling and meaning on the first line of the formula as a counseling skill, but is not represented in the graphic because of the invisible nature of this skill. The absence of spoken words can have a significant impact on the session if used appropriately, allowing clients the opportunity to think about, process and often discover insight related to their personal struggle.

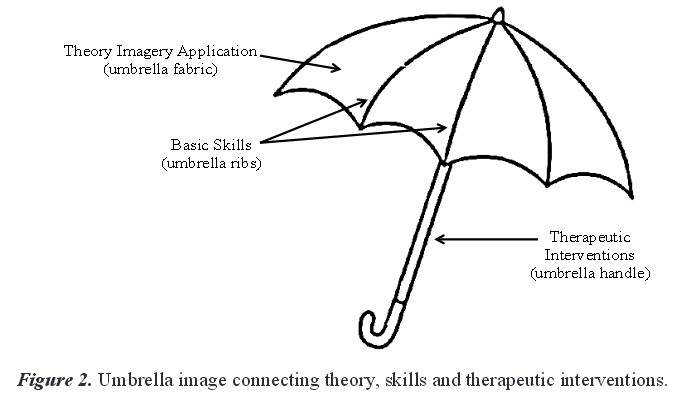

A concept map can be applied to learning basic skills; it also can be applied to connect theory application and theoretical interventions with basic skills. An open umbrella is an excellent graphic that unites these disjointed pieces and crystallizes them into a working concept. The metal ribs of the umbrella are basic skills. The ribs provide the structure of the session and are the tools counselors use to work with their clients. The fabric of the umbrella is the theory imagery application. Theory and basic skills work together to determine how counselors do their job, just as the metal frame and umbrella fabric work together to do their job, which is to keep the user protected from the elements. Umbrella fabric comes in different colors and patterns, and so do counseling theories. Each counselor must find one that fits his or her style, personality, and perspective or viewpoint on how clients are best helped (Evans, Hearn, Uhlemann, & Ivey, 2011; MacCluskie, 2010).

The handle of the umbrella is important since it provides something to hold on to, and comes in various shapes and sizes. Some handles collapse so that the umbrella will fold up and can be carried easily in a briefcase or purse. Some handles are rigid, and can serve another purpose such as providing walking assistance. Counseling techniques, or therapeutic interventions, are the equivalent of the umbrella handle, since it is possible to utilize a variety of techniques with more than one theoretical orientation. Techniques are versatile and can be a significant part of the session, just as the handle is a significant part of the umbrella. However, students must understand the importance of establishing the framework structure first (basic skills illustrated in the counseling formula) before they can move toward conceptualizing a client with their theory of choice (see Figure 2). After counseling students have mastered basic skills, they can move to more advanced intervention techniques (e.g., empty chair, genogram). Mastery allows students to develop a new understanding through building upon different concepts to fit with the open umbrella graphic; this strategy also is known as concept management (Akinsanya & Williams, 2004).

The counselor’s job is not to make clients change; that is the client’s responsibility. Clients are the experts of their situations or issues, and it is up to them to determine what they are willing and capable to change. Before they can make decisions about change (Chg), they must first have insight (I) to understand that they have choices (see Figure 1). Before they develop insight (I), they initially must have an awareness (A) of what is creating their struggle. The counselor’s timing with active listening skills, appropriate confrontation and silence facilitates client awareness (A) and insight (I).

Clients work on the second line (A à I = Change), but the second line is ultimately facilitated by the first line (C + F = M), which is similar to the five stages of change presented by Evans et al. (2011, p. 292). Therefore, this formula indicates that the counselor’s work focuses on the first line and the client’s work focuses on the second.

The second line of the concept map formula also serves as a crosslink in one’s development from student to counselor. In making this transition in the professor–student relationship, the professor explores the student’s understanding by focusing on the first line of the formula, and the student struggles with personal and professional change in the second line of the formula. As student counselors map out their progress in a counseling session, they are simultaneously developing awareness (A) through the growth and practice of basic skills, which leads to insight (I) related to development of professional effectiveness in shaping the session. This process gives beginning counselors a sense of professional identity development and the ability to track progression at the top of the equation. Just as clients are ready for change when they develop awareness and insight, student counselors cannot include their theoretical orientation and techniques until they develop their own awareness in the therapy room and grasp the application of skills employed in the therapeutic session. Therefore, the client’s role in counseling also is the student’s role in professional development; and caution must be exercised not to initiate change too quickly with either the student or client, depending on how the formula is applied.

Counseling students often have heard from family and friends that they are great listeners; however, their sense of homeostasis is challenged when they sit across from clients while trying to master basic skills. They are anxious to jump ahead and learn to use techniques that are appropriate for their counseling theory of choice. Because counseling students jump ahead, they tend to overlook the importance of mastering fundamental skills. Since students have not mastered basic skills, they struggle to understand how theory and techniques work together to help clients. This situation can lead to ineffective use of both theories and techniques.

When the counselor moves too quickly, the client’s sense of balance is thrown off and resistance may occur because of low commitment or discomfort with change (Reiter, 2008; Wachtel, 1999). Resistance is the client’s attempt to return to a sense of homeostasis, even if homeostasis is not effectively meeting the client’s needs. MacCluskie (2010) posited that “the concept of homeostasis, borrowed from physiology, refers to the process by which an organism regulates its internal environment to maintain a stable, constant condition” (p. 212).

According to the formula, when the counseling process focuses on the cognitive content, resistance surfaces through the initial “storytelling” that clients offer. Beginning counselors often jump from hearing clients’ stories (cognition) to problem solving or advice giving (change) and encounter polarity or the yes, but type of resistance. Clients may agree with their counselors’ reflections, but respond with multiple excuses for why the suggestions or advice will not work (MacCluskie, 2010; Reiter, 2008; Wachtel, 1999). However, resistance or excuse making is the clients’ means of protection or attempt to return to a state of homeostasis when the counseling process threatens to push them to abandon their familiar life patterns or concepts of themselves, or push them too quickly to embrace change (Omer, 2000; Patterson & Welfel, 2000).

Basically, counselors forget to take their clients with them through the therapeutic process and must return to the beginning of the first line of the equation (C + F = M). As counselors work here, they must learn to trust the therapeutic process enough to allow clients to do their work on the second line (A promotes I, which facilitates Chg). Through clients’ responses and explorations, their awareness is raised, they gain insight and they are then empowered to make choices related to their personal change comfort level.

Two skills not included as part of the formula are confrontation and immediacy, because these advanced skills come later in the training process. Beginning counselors must first develop mastery of initial skills before they are ready to tackle confrontation and immediacy. While confrontation and immediacy may be powerful methods of intensifying emotions, they also may result in significant disengagement of the client if misused or if the timing is inappropriate (Cormier & Hackney, 2012; Evans et al., 2011; Smaby & Maddux, 2011).

Implications for Future Research

This counseling formula study supports the conclusion that a complex learning strategy, such as cognitive mapping, can be effective for counseling students of varied learning styles and cultures. In addition, evidence suggests that forcing students to use strategies that challenge their learning style preferences can be a beneficial attempt to increase their problem-solving skills (Kostovich et al., 2007). Further investigation of the influence of the counseling formula with beginning counseling students could provide counselor educators insight as to how their students are learning the counseling process using cognitive mapping. It is an organized method of teaching basic skills so that students do not find themselves overwhelmed with too much new learning to master at one time. Future research would be helpful to validate the general application of this formula and the umbrella concept when introducing beginning students to the basic tools of their future profession.

Conclusion

The simple images of a counseling formula and a symbolic umbrella help beginning counselors initially understand the interconnectedness of the different counseling skills of their new profession. However, this article is not suggesting that counseling is simplistic or that it does not utilize higher order skills and concepts. Counselor educators can use these symbolic representations as cognitive schemas to build upon students’ knowledge as they integrate practical application into their counseling sessions. Cognitive maps provide a way for counselor educators to see where students get stuck in the beginning counselor process, and provide a tool that allows a way of learning that is visual and communicative. This visual representation outlines and crosslinks the critical roles of the therapy process by connecting the communication and experiences of the student counselor to those of the client.

The student counselor stays at the top of the equation, while the client remains at the bottom. As student counselors become more seasoned, they also begin to experience personal and professional growth that results in their own awareness, insight and change; therefore, they experience crosslinking at the bottom of the equation that is similar to how clients begin to change. As clinicians gain experience, they move to a deeper understanding of how to use basic skills with theory, incorporated with existing intentional therapeutic interventions and techniques, in order to facilitate change for their clients. Through this process, clinicians come to fully appreciate both the therapeutic relationship and the counseling process.

Initial learning experiences in kindergarten are designed to help beginning students master simple, repetitive writing tasks. This initial learning experience can be compared to beginning experiences for master’s-level counselors through the effective utilization of initial basic skills linked in the counseling session. The formula and umbrella graphics can provide valuable visual tools to lay a solid foundation for the beginning counselor.

Utilizing the formula and umbrella graphics to gain an understanding of the application of basic skills is a valuable tool on the clinician’s lifelong learning journey to become a more effective counselor. When clinicians are “stuck” with a client, what better tools are within our grasp than to return to basic skills and use the formula? Basic skills are an integral part of the clinician’s toolbox, regardless of theoretical orientation or therapeutic interventions. These tools open clients’ awareness (A), promote insight (I), and unlock a myriad of options for clients to embrace (Chg) change (Asimakopoulou et al., 2012; Jacobs, 1994; Jacobs et al., 2012; Meier & Davis, 2011).

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

Ackerman, A. J., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (2001). A review of therapist characteristics and techniques negatively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Psychotherapy, 38, 171–185. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.38.2.171

Akinsanya, C., & Williams, M. (2004). Concept mapping for meaningful learning. Nurse Education Today, 24, 41–46. doi:10.1016/S0260-6917(03)00120-5

Asimakopoulou, K., Gilbert, D., Newton, P., & Scrambler, S. (2012). Back to basics: Re-examining the role of patient empowerment in diabetes. Patient Education and Counseling, 86, 281–283. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.03.017

Chang, V. N., Scott, S. T., & Decker, C. L. (2009). Developing helping skills: A step-by-step approach. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Cormier, S., & Hackney, H. (2012). Counseling strategies and interventions (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Dansereau, D. F., & Dees, S. M. (2002). Mapping training: The transfer of a cognitive technology for improving counseling. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 22, 219–230. doi:10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00235-0

Evans, D. R., Hearn, M. T., Uhlemann, M. R., & Ivey, A. E. (2011). Essential interviewing: A programmed approach to effective communication (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Flaskas, C. (2004). Thinking about the therapeutic relationship: Emerging themes in family therapy. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 25, 13–20. doi:10.1002/j.1467-8438.2004.tb00574.x

Henriksen, R. C., Jr., & Trusty, J. (2005). Ethics and values as major factors related to multicultural aspects of counselor preparation. Counseling & Values, 49, 180–192. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007X.2005.tb01021.x

Hill, L. H. (2005). Concept mapping to encourage meaningful student learning. Adult Learning, 16 (3/4), 7–13.

Jacobs, E. (1994). Impact therapy. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Jacobs, E. E., Masson, R. L, Harvill, R. L., & Schimmel, C. J. (2012). Group counseling: Strategies and skills (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Kostovich, C. T., Poradzisz, M., Wood, K., & O’Brien, K. L. (2007). Learning style preference and student aptitude for concept maps. Journal of Nursing Education, 46, 225–231.

MacCluskie, K. (2010). Acquiring counseling skills: Integrating theory, multiculturalism, and self-awareness. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill.

McAuliffe, G., & Eriksen, K. (2002). Teaching strategies for constructivist and developmental counselor education. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

McClam, T., & Woodside, M. (2010). Initial interviewing: What students want to know. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Meier, S. T., & Davis, S. R. (2011). The elements of counseling (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Moursund, J., & Kenny, M. C. (2002). The process of counseling and therapy (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Novak, J. D., & Gowin, D. B. (1984). Learning how to learn. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Omer, H. (2000). Troubles in the therapeutic relationship: A pluralistic perspective. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 201–210.

Patterson, L. E., & Welfel, E. R. (2000). The counseling process (5th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2003). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis (5th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Reiter, M. D. (2008). Therapeutic interviewing: Essential skills and contexts of counseling. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, theory, and implications. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95–103. doi:10.1037/h0045357

Rogers, C. R. (1958). The characteristics of a helping relationship. Personnel and Guidance Journal, 37, 6–16. doi:10.1002/j.2164-4918.1958.tb01147.x

Slattery, J. M., & Park, C. L. (2011). Empathic counseling: Meaning, context, ethics, and skill. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Smaby, M., & Maddux, C. D. (2011). Basic and advanced counseling skills: The skilled counselor training model. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Smith, S. A., Thomas, S. A., & Jackson, A. C. (2004). An exploration of the therapeutic relationship and counselling outcomes in a problem gambling counselling service. Journal of Social Work Practice, 18, 99–112. doi:10.1080/0265053042000180581

Svinicki, M., & McKeachie, W. J. (2011). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers (13th ed). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Van Velsor, P. R., & Cox, D. L. (2000). Use of the collaborative drawing technique in school counseling practicum: An illustration of family systems. Counselor Education and Supervision, 40, 141–52. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2000.tb01245.x

Veletsianos, G. (2010). Contextually relevant pedagogical agents: Visual appearance, stereotypes, and first impressions and their impact on learning. Computers & Education, 55, 576–585. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.019

Wachtel, P. L. (1999). Resistance as a problem for practice and theory. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 9, 103–117. doi:10.1023/A:1023262928748

Susan A. Adams, NCC, is a private practice counselor and supervisor in Denton, TX. Alice Vasquez, NCC, is a doctoral student at Texas A&M – Commerce. Mindy Prengler, NCC, is a counseling intern at Fine Marriage & Family Therapy, Plano, TX. Correspondence can be addressed to Susan A. Adams, 225 West Hickory Street, Suite C, Denton, TX 76201, drsadams@centurylink.net.