Nov 9, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 4

Stacey Diane Arañez Litam, Christian D. Chan

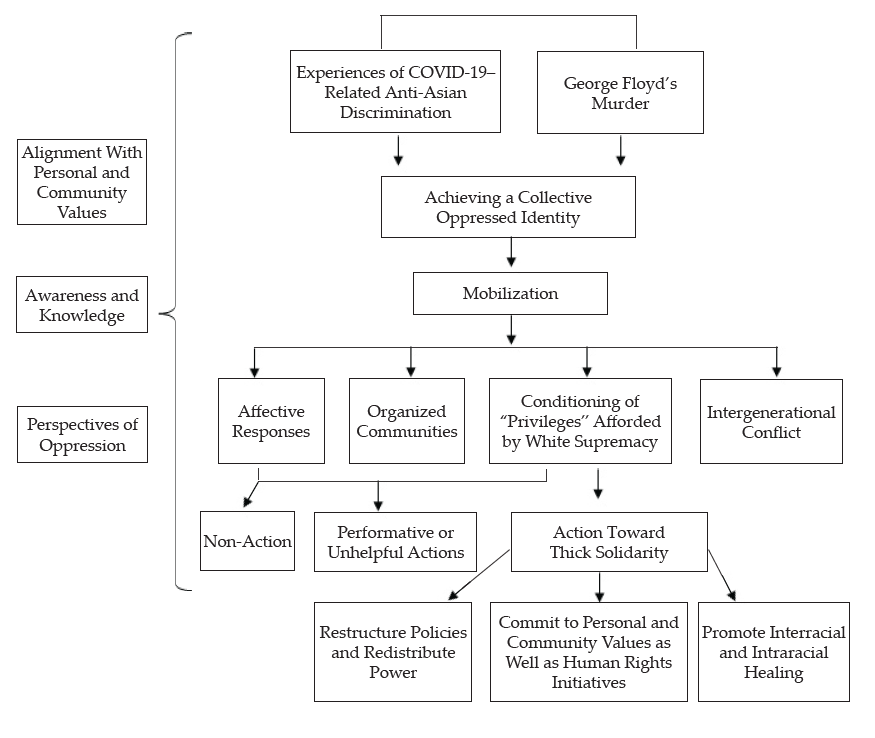

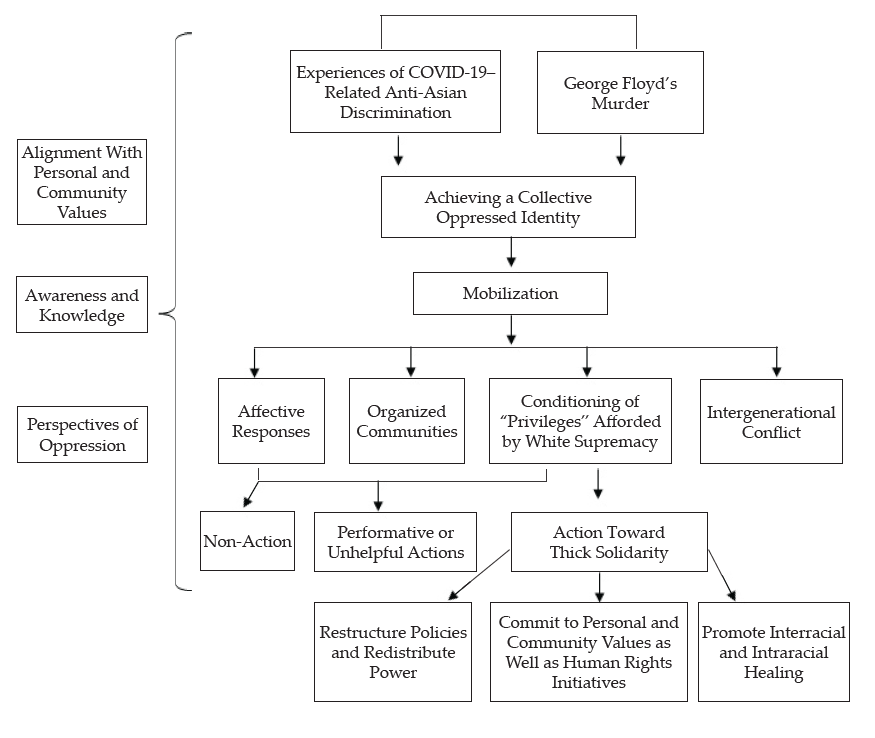

A grounded theory study was employed to identify the conditions contributing to the core phenomenon of Asian American activists (N = 25) mobilizing toward thick solidarity with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in 2020. The findings indicate achieving a collective oppressed identity was necessary to mobilize in thick solidarity with the BLM movement and occurred because of causal conditions: (a) experiences of COVID-19–related anti-Asian discrimination, and (b) George Floyd’s murder. Non-action, performative or unhelpful action, and action toward thick solidarity were influenced by contextual factors: (a) alignment with personal and community values, (b) awareness and knowledge, and (c) perspectives of oppression. Mobilization was also influenced by intervening factors, which included affective responses, intergenerational conflict, conditioning of “privileges” afforded by White supremacy, and the presence of organized communities. Mental health professionals and social justice advocates can apply these findings to promote engagement in the community organizing efforts of Asian American and Pacific Islander communities with the BLM movement, denounce anti-Blackness, and uphold a culpability toward supporting the Black community.

Keywords: Asian American, solidarity, social justice, Black Lives Matter, grounded theory

Trayvon Martin’s death in 2012 reignited conversations about the underlying sentiments of White supremacy that remain deeply entrenched in American society (Khan-Cullors & Bandele, 2017; Taylor, 2016). Shortly thereafter, the #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) movement was launched to address acts of police brutality on Black and Brown people and challenge the systemic oppression within the justice system (Lebron, 2017). Following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the role of silence in perpetuating complicity resurfaced, and the familiar narratives and gut-wrenching images of non-Black police officers harming Black bodies once again found a place in the limelight (Chang, 2020; Elias et al., 2021). However, this time there was something noticeably different; one of the non-Black officers was Asian American.

Tou Thao’s role in sanctioning George Floyd’s murder illuminated the complex history of anti-Blackness within Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities; created momentum for conversations about race, discrimination, and oppression; and echoed earlier support for the BLM movement among AAPIs (J. Ho, 2021; Merseth, 2018; Tran et al., 2018). These discussions may have been traditionally avoided, given the narrative invoked by racial and colonial notions that diminishes critical consciousness about racial histories and relations in AAPI communities (Chang, 2020; David et al., 2019). Because of the structural conditions of White supremacy and colonialism, AAPI communities have been forced to adopt Whiteness as a pathway to success, minimize salient cultural values, and trivialize manifestations of anti-Blackness (J. Ho, 2021; Poon et al., 2016). Erasing critical consciousness among AAPI communities has served as an insidious attempt to maintain a racial hierarchy that neither supports AAPI visibility nor eradicates racial tensions (Chou & Feagin, 2016; David et al., 2019). The invisibility of AAPI history absolves the United States from long-standing histories of anti-Asian racial violence (Li & Nicholson, 2021) and endorses complacency of White supremacy (Museus, 2021; Poon et al., 2019). Although this contention exists, a greater number of AAPI voices have begun to mobilize in solidarity with the BLM movement and the Black community in recent years (Anand & Hsu, 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Merseth, 2018; Tran et al., 2018).

Despite a complex racialized history of White supremacists weaponizing communities of color against each other (Nicholson et al., 2020; Poon et al., 2016), AAPI individuals have a long-standing history of pursuing thick solidarity and activism with the Black community and supporting Black civil rights (J. Ho, 2021). These racial coalitions have been evidenced through the Third World Liberation Front Strikes and the tireless efforts of activists like Grace Lee Boggs, Yuri Kochiyama, and Richard Aoki (W. Liu, 2018; Sharma, 2018). Thick solidarity is achieved when racial differences are acknowledged while emphasizing the specificity, irreducibility, and incommensurability of racialized experiences (W. Liu, 2018). Although understanding the factors that influence AAPIs to mobilize with the Black community represents a critical step toward thick solidarity (Tran et al., 2018), previous studies investigating the phenomenon have been limited to quantitative methods (Merseth, 2018; Yoo et al., 2021) or focused solely on Southeast Asian American populations (Lee et al., 2020).

The following sections outline the histories of racialized oppression faced by Asian American and Black communities and provide a brief overview of the extant research linking Asian American solidarity with the BLM movement. A grounded theory that identifies the emergent process that contributed to Asian American activists mobilizing toward thick solidarity with the BLM movement in 2020 is additionally presented.

The Racialized Experiences of Asian Americans and Black Communities in America

Prior to engaging in a grounded theory, researchers must build upon preexisting processes, theories, and perspectives documented in extant research (Charmaz, 2017). Thus, one cannot explore the processes that contributed to Asian American activists mobilizing toward thick solidarity with the BLM movement in 2020 without first addressing the nuanced and racialized experiences of AAPI and Black communities in America. Tran et al. (2018) asserted that navigating an oppressive system embedded in White supremacy has forced communities of color to make historical adaptations that leave AAPI voices out of the BLM movement. The following section provides a brief description of the complexity in which AAPI and Black identities are juxtaposed and elaborates on the model minority myth, racial triangulation, and historical anti-Blackness in AAPI communities as processes that may complicate the process of achieving thick solidarity.

Racial Triangulation

According to Kim (1999), racial triangulation theory refers to a “field of racial positions” (p. 106) that was proposed to extend the conceptualization of racial discourse beyond the Black and White narrative. The field of racial positions is mapped onto two dimensions. The superior/inferior axis represents the process of relative valorization, whereby Whites valorize Asian Americans relative to Black Americans in ways that maintain White privilege and White supremacy (Kim, 1999). The second dimension, an insider/foreigner axis, refers to the process of civic ostracism, in which Whites position Asian Americans as foreign, unassimilable, and outsiders (Kim, 1999; Xu & Lee, 2013). Although Asian Americans may be afforded social and economic benefits due to their proximity to Whiteness, this social location functions as an incomplete portrayal that conceals inequities, treats Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners, and maintains the status of White supremacy over communities of color (Bonilla-Silva, 2004; Nicholson et al., 2020). As a result, members of Asian American communities may be racialized to be White-adjacent and create an illusion of success with a conditional set of privileges (Kim, 1999; Museus, 2021).

One example of racial triangulation is the model minority myth, which essentializes Asian Americans by portraying them as a monolithic group with universal educational and occupational success (Chou & Feagin, 2016; Yi et al., 2020). According to Poon et al. (2016), scholars must acknowledge the model minority myth’s history to challenge processes of racial triangulation and deficit thinking. The model minority myth creates barriers to social justice efforts and racial coalitions by pitting communities of color against one another (Chang, 2020), invalidating experiences of systemic oppression and discrimination (Nicholson et al., 2020; Pendakur & Pendakur, 2016), and maintaining “a global system of racial hierarchies and White supremacy” (Poon et al., 2016, p. 6). When contextualizing the model minority myth through the lens of critical race theory, Asian Americans may be conceptualized as a “middleman minority” (Poon et al., 2016, p. 5). Originally coined by Blalock (1967) and later expanded upon by Bonacich (1973), middleman minorities are foreigners who buffer the power struggles between two major groups in a host society. Similar to other historical middleman minority groups, the minority model myth exploits Asian Americans by granting economic privileges while denying political or social power (Poon et al., 2016). As a more egregious consequence, the model minority myth can lead communities of color to harbor feelings of resentment toward Asian American communities, especially Asian immigrants who may feel pressured to prove their loyalty to American values (J. Ho, 2021) and embrace the submissive, hardworking qualities espoused by the model minority myth (Poon et al., 2019).

The complex relationship between AAPI and Black communities becomes even more complex as communities of color, including Black Americans, continue to define the boundaries of inclusion about “who belongs in communities of Color” (Tran et al., 2018, p. 78). As a result, Asian Americans are rarely included in race dialogues; may not be identified as “of color” by other groups; and are forced to navigate their weaponized, conditional identities as racialized in some spaces and White-adjacent in others (C. D. Chan & Litam, 2021; Litam & Chan, 2021; Museus, 2021; Poon et al., 2016).

Understanding Anti-Blackness in Asian American Communities

The denigration of Black identities and the desire to be viewed as distinct from Black Americans are evidenced across the histories of several Asian American ethnic subgroups. For example, in the mid-20th century, access to U.S. citizenship was limited to free White persons and persons of African descent (Pavlenko, 2002). At the time, the system was not set up to accommodate Asian Americans or other racialized groups, as evidenced by the landmark cases of Takao Ozawa and Bhagat Singh Thind (Chou & Feagin, 2016; Haney López, 2006). After living in the United States for over 20 years and articulating his relationship to White racial groups because of his light skin, Takao Ozawa, a Japanese man, was judged to be a race other than those able to obtain citizenship and deemed ineligible for naturalization (S. Chan, 1991; Yamashita & Park, 1985). Bhagat Singh Thind, an Asian Indian man, attempted to align specifically with the use of “Caucasian” and White racial ideologies, but was also denied citizenship by the U.S. Supreme Court (Haney López, 2006). Following the United States v. Bagat Singh Thind ruling, nearly 50% of Asian Indian Americans had their U.S. citizenship revoked (Haney López, 2006). Despite attempts to prove their loyalty to Whiteness, both cases reified how Asian Americans are placed in a vexing situation that provides an illusion of privileges but excludes them from fully participating as U.S. citizens (Haney López, 2006; Nicholson et al., 2020). Both cases also exemplified early instances of Asian American individuals who were pressured by prevailing racial ideologies to eschew Blackness and assimilate into dominant norms of White supremacy.

Examples of anti-Black sentiments are deeply rooted in people of Filipino descent who may endorse colonial mentality, an internalized form of oppression characterized by a preference for Western attitudes and the denigration of Filipino culture following years of colonization by the United States (David & Okazaki, 2006a, 2006b). For example, internalized anti-Black sentiments in Filipino culture are evidenced by the systematic discrimination against the dark-skinned Ati people, who are indigenous to the Aklan region (Petrola et al., 2020). As a result of the mining, logging, and tourism industries, the Ati have been forced to relocate onto smaller plots of land, face physical violence, and are denied various human rights (Petrola et al., 2020). Other insidious anti-Black attitudes that permeate the Filipino worldview include White-centered beauty notions that venerate straight hair and light skin over textured locks and dark skin (Nadal, 2021; Rafael, 2000). Despite their documented toxic and dangerous consequences, skin whitening products in the Philippines are a billion-dollar industry (Mendoza, 2014). These examples relay cultural and economic implications that are predicated on histories of global imperialism and colonialism, which root out indigeneity in favor of Eurocentric values and White norms (Fanon, 1952). Examples of anti-Black sentiments in Filipino communities are a sample of the ways in which colonialist movements mapped anti-Blackness onto Filipino communities and culture by occupation of the land, terrorism, and brutality (David, 2013; Nadal, 2021).

History of anti-Black attitudes may also exist in Korean Americans following the 1992 Los Angeles riots. After White officers were exonerated in the beating of Rodney King and a Korean store owner fatally shot 15-year-old Latasha Harlins, tension erupted between the Black and Korean American communities due to the lack of accountability for the killing of a Black person. Media reports of widespread rioting, theft, injuries, and damage to businesses were attributed to poor race relations between African American and Korean communities and larger issues of systemic racism were disregarded (Oh, 2010; Sharma, 2018). Despite calls to law enforcement for help, Korean voices were overlooked by the police (Yoon, 1997), which potentially illustrates how the law enforcement system reacts in favor of White interests. Once again, White media highlighted the undercurrent of racial tension between ethnic and racial groups as noteworthy and masked preexisting racial coalitions between Black and Asian American communities. These news stories deterred Asian American and Black communities from looking outward and acknowledging the larger issues of ongoing police brutality and inequitable justice systems (F. Ho & Mullen, 2008).

Chinese Americans may harbor anti-Black notions following the conviction of Peter Liang, who fatally shot Akai Gurley in New York City (W. Liu, 2018). Although he was the first officer indicted for killing an unarmed and innocent Black man, Liang’s conviction resulted in conflict between Chinese American and Black American communities (R. Liu & Shange, 2018; W. Liu, 2018). Many individuals within Asian American communities argued for the fair sentencing and punishment of Liang (Tran et al., 2018), but others protested the charge and believed the courts used him as a scapegoat to detract from BLM activists who called for police reform (R. Liu & Shange, 2018; W. Liu, 2018).

Challenging Historical Anti-Blackness in Asian American Communities

Challenging anti-Blackness in Asian American communities underscores a cultural paradox. On one hand, Asian American individuals, especially East Asian subgroups, benefit from social and economic privileges because of their proximity to Whiteness and identities as non-Black minorities (Bonilla-Silva, 2018; Poon et al., 2016). Thus, some Asian American individuals endorse aspects of the model minority myth because of the privilege it affords (Kim, 1999), even at the expense of maintaining a racially triangulated identity (Bonilla-Silva, 2004; Poon et al., 2019; Yi et al., 2020). Anti-Blackness therefore moves beyond prejudicial attitudes against Blacks and encompasses a performance of Whiteness (W. Liu, 2018).

Movements initiated by younger Asian American generations that challenge anti-Black sentiments (e.g., #Asians4BlackLives) are gaining traction (Anand & Hsu, 2020; Lee et al., 2020) and can help Asian immigrants move beyond their own unacknowledged pain and racial trauma to appreciate the challenges of other marginalized communities (David et al., 2019; Tran et al., 2018). For example, Letters for Black Lives is a crowdsourcing project that empowers communities of color to have conversations about anti-Blackness with older generations (R. Liu & Shange, 2018) who may endorse anti-Black attitudes following injustices against Asian people (e.g., Peter Liang) or anti-Asian historical events (e.g., the LA riots). These letters help younger Asian American communities describe ambiguous and complex issues related to social justice, racism, and systemic oppression with their families and have been helpful in promoting support for the BLM movement (Arora & Stout, 2019).

Extant Research on Racial Coalitions

Extant research posits how experiences of ingroup discrimination cultivate increased empathy, positive attitudes, and a collective sense of community (Craig & Richeson, 2012; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). As rates of anti-Asian discrimination have substantially increased following the COVID-19 pandemic and negatively affected the psychological well-being of Asian American communities (C. D. Chan & Litam, 2021; Jeung & Nham, 2020; Litam, 2020; Litam & Oh, 2020, 2021; Litam et al., 2021), the Common Ingroup Identity Model (CIIM; Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000) may help explain the increasing number of Asian American voices in support of BLM. According to the CIIM, experiences of racial discrimination toward one’s own racial group may lead to a shared disadvantaged racial minority identity that engenders positive attitudes and feelings of closeness toward other racial minorities. Compared to White, male, high-status groups, racialized minorities (e.g., Asian Americans) may be more likely to experience feelings of solidarity and affiliation with other communities of color believed to share experiences of racial discrimination (Brewer, 2000; Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000).

Preliminary support for the CIIM may be evidenced by a quantitative study conducted by Merseth (2018). Using a nationally representative sample of data, Merseth determined AAPIs who supported BLM were more likely to perceive anti-Black discrimination in the United States and identify race-based linked fates. A recent ethnography that examined AAPI support for the BLM movement identified the importance of community-based educational spaces as paramount to engaging in antiracist work and cultivating cross-racial coalitions among Southeast Asian Americans (Lee et al., 2020). Lee and colleagues’ (2020) results illuminated the importance of educational institutions that provide the foundation and language needed to challenge anti-Blackness among Southeast Asian communities. Combined with these studies, a more recent investigation by Yoo et al. (2021) involved a quantitative measurement of racial groups and their support for the BLM movement. Although this crucial study revealed the implications of solidarity among several racial groups with the BLM movement, the Yoo et al. study only involved a convenience sample of college students and did not necessarily account for the nuances within participants’ social identities, their motivations for support, or historical and political contexts. In the context of increased anti-Asian racial discrimination in the wake of COVID-19, shared experiences of anti-Asian discrimination may result in “a common ground of solidarity that Asian Americans and African Americans can forge against White supremacy” (Anand & Hsu, 2020, p. 194).

Purpose of the Present Study

The centralization of police brutality on Black and Brown people has reignited conversations about systemic oppression and has illuminated the need for civil rights, racial equity, and the dismantling of White supremacy (Elias et al., 2021; R. Liu & Shange, 2018; W. Liu, 2018; Tran et al., 2018). Although AAPIs may face discrimination in the wake of COVID-19 in ways that may result in solidarity with the BLM movement (Chang, 2020; J. Ho, 2021), a qualitative study that underscores this process with diverse Asian American voices can further contextualize meaningful opportunities for racial coalitions. Given the historical presence of anti-Blackness in Asian American communities (W. Liu, 2018; Tran et al., 2018), generating an emergent process that outlines the path of Asian American activists mobilizing toward thick solidarity with the BLM movement is of paramount importance to continue bolstering efforts toward racial coalitions (Lee et al., 2020; Merseth, 2018). To address the paucity of literature, a grounded theory was conducted to examine the following research question: What is the process that mobilizes Asian American activists to pursue thick solidarity with the BLM movement in 2020?

Method

Qualitative methods are appropriate when researchers seek to develop a complex or detailed understanding of an experience (Creswell & Poth, 2018). Specifically, grounded theory is a qualitative method used to generate a theory grounded in the data from participants who have experienced the process under inquiry and focuses on maximizing numerous perspectives constructed over phases of time (Charmaz, 2017). Given our desire to understand the process of action through which Asian American activists mobilize toward thick solidarity with the BLM movement, a grounded theory approach was deemed appropriate. To this end, the grounded theory focused on what participants experience and how the process of mobilizing in solidarity for BLM unfolds.

This study was implemented using a social constructionist paradigm to complement Charmaz’s (2014) constructivist grounded theory. Social constructionist researchers recognize the presence of multiple, processual, and constructed realities while acknowledging the role and importance of the researchers’ and participants’ positionality (Charmaz, 2014; Clarke, 2012). Social constructionism augments three overarching themes: (a) critiquing the neutrality of participants’ and researchers’ values by locating perspectives within social contexts (e.g., time, culture); (b) revealing language as a vehicle for shaping representation within particular communities; and (c) introducing different perspectives to unsettle social conditions and co-create new knowledge (K. J. Gergen, 2020; M. Gergen, 2020).

Procedure and Participants

Internal Review Board approval was obtained before beginning the study. Participants in this study were selected through the use of purposive and theoretical sampling (Timonen et al., 2018). The first and second authors, Stacey Diane Arañez Litam and Christian D. Chan, used purposive sampling to disseminate recruitment materials to key social media groups and community networks focused on AAPI community organizing. In the initial stages, Litam interviewed the first group of participants and ascertained their social identities. Next, theoretical sampling was employed. To introduce additional perspectives after the first group, Litam focused on soliciting more participants to expand the sample based on region, gender, and ethnic identities. Prospective participants could participate if they (a) self-identified as a member of the Asian American community and (b) identified as being engaged in ongoing support of the BLM movement. Prospective participants were recruited by posting on social media pages frequented by Asian American individuals actively involved in BLM activism. Prospective participants were asked to email Litam and were given more information describing the study’s purpose, design, and research questions. Eligible participants were informed that participation was voluntary, the research would not directly benefit them, and no compensation would be offered. A consent form was completed before participation occurred. Interviews were held on a HIPAA-compliant Zoom account.

This study consisted of interviews with 25 AAPI individuals who were actively engaged with the BLM movement. To protect confidentiality, participants were given pseudonyms. Participants reported a diversity of identities that increased the heterogeneity of the sample. Participants’ ages ranged from 25 to 73, and ethnic identities of participants included Filipino (n = 10), Korean (n = 5), Chinese (n = 2), Japanese (n = 1), Vietnamese (n = 1), Chamorro (n = 1), and multiracial (n = 5) descent. The gender identities of participants included women (n = 17), men (n = 5), and non-binary (n = 3). Most participants reported being a U.S. citizen and one participant identified as Canadian. Four participants identified as transracial adoptees.

Data Collection

Data collection occurred between June and July 2020. Semi-structured interviews lasted an average of 90 minutes. Participants responded to the following questions: (a) What are your experiences regarding how Asian Americans have historically supported, or are currently supporting, the Black Lives Matter movement? (b) Which contexts or situations have influenced your desire to support the Black Lives Matter movement? and (c) Which contributing factors influenced your development toward a social justice–oriented mindset? Follow-up questions developed organically. Participants provided consent for the interview to be recorded and were informed they could end the recording or the interview at any time. Only the audio file of the interview was saved, and the file was not uploaded to any cloud-based servers so as to promote participant confidentiality. Litam transcribed all interviews. Following the interview, participants completed two 15-minute member-check meetings—first to confirm the accuracy of researchers’ themes, and second to reflect on the final grounded theory.

Throughout the interview, Litam restated the major points after each response. Clarification was obtained through follow-up questions when participants described new concepts that had not been described by previous participants. Litam did not move onto the next question until each of the major points described by the participant were accurately identified and reflected. At the end of the interview, Litam summarized the conversation and restated the major points to confirm understanding of the participants’ statements. Follow-up questions, member checks, restatements, analytic memo writing, and constant comparative method were used to analyze the data.

Data Analysis

The data collection and analysis process reflected a concurrent process and a recursive process, which informed one another and led to the development of an emerging grounded theory (Charmaz, 2017). Throughout the data analysis process, concurrent analytic techniques of induction, deduction, and verification were used to develop an emergent theory (Charmaz, 2014). Litam immersed herself in the raw data by transcribing, reading, and listening to the audio transcripts. Transcription was completed within 24 hours of the interview, and member checks with participants to confirm themes were completed within 72 hours of the interview. New data were compared to existing data following the completion of each transcribed interview. Initial codes and analytic memos were used throughout the process to create an audit trail. Data were closely examined for disconfirming evidence, and two external auditors were used throughout the data analysis process to understand how our assumptions could influence the coding and findings.

Two external auditors were used between open and focused coding to confirm emergent findings, discuss the accuracy of emerging themes, and triangulate across perspectives (Saldaña, 2021). Both external auditors identified as members of the AAPI community and endorsed a strong commitment to AAPI concerns, research, and mental health. The second external auditor also carried in-depth training in qualitative methodologies. Data were coded with labels that categorized, summarized, or accounted for each piece of data (Charmaz, 2014; Saldaña, 2021) and analytic memos were used to help scrutinize the data (Miles et al., 2020). Each participant confirmed the accuracy of themes and reported feeling energized by the theory, a phenomenon known as catalytic validity (Guba & Lincoln, 1989).

We engaged in reflective commentary throughout the interview and data analysis process by using bracketing and ongoing evaluation. Peer scrutiny was employed by inviting three AAPI colleagues who were familiar with the phenomenon to offer feedback and fresh perspectives on the findings as they continued to emerge and become saturated. The first colleague identifies as a transnational Chinese woman and is an associate professor. The second colleague identifies as a Chinese woman who specializes in counseling AAPI communities. The third colleague identifies as a Filipino, Chinese, and Malaysian man and works as a counselor educator. Interviews were conducted until saturation occurred and fresh data no longer sparked new theoretical insights or properties of the generated grounded theory, its categories, or its concepts.

Researcher Reflexivity

A researcher’s social location, biases, theoretical lens, and epistemological beliefs must be established to increase the trustworthiness of results (Saldaña, 2021). Litam identifies as a foreign-born Filipina and Chinese American woman. She is a counselor educator, an assistant professor, and a licensed professional clinical counselor and a supervisor. She conducts research on topics related to human sexuality, human trafficking, trauma, race, diversity, and AAPI issues. Litam has overcome her own internalized colonial mentality as a Filipina American woman and endorses a strong commitment toward issues of social justice and racial equity. She is dedicated to engaging in work that dismantles the forces of White supremacy that oppress all racialized groups.

Chan is a queer person of color and a second-generation Asian American of Filipino, Chinese, and Malaysian heritage. As an assistant professor, he invests primarily in scholarship on intersectionality, social justice, activism, multiculturalism, career development, and communication of culture and socialization in couple, family, and group modalities. He actively works toward racial coalitions that interrogate structures of White supremacy and organizes intentional community initiatives for solidarity. Many of his perspectives, especially toward the inquiry at hand, attend to social structures and histories that underpin ideologies of White supremacy.

Trustworthiness

Grounded theory requires standards of quality and trustworthiness, including credibility, originality, resonance, and usefulness (Charmaz, 2014; Creswell & Poth, 2018). To promote trustworthiness, constant comparison was employed by using open codes, a codebook, and data to inform, analyze, and compare new data sources (Charmaz, 2014). Any new data were consistently checked and compared to the emerging theory. Member checks were completed twice by connecting with participants over Zoom for approximately 15 minutes each. We also used peer scrutiny with three AAPI colleagues and two AAPI external auditors to challenge assumptions and biases, triangulate findings, and engage in dialogue about clusters of meaning and themes as they emerged. These strategies were used to ensure the theory was data-driven rather than reflective of our own beliefs, values, and assumptions (Hays & Singh, 2012). Analytic memos were written after each round of coding, which elaborated emotions, thoughts, and personal reactions to the data. This information strengthened the tracking of the data and our influence as we shared the audit trail with both external auditors. Thus, multiple measures of trustworthiness were used to account for positionality that could influence the data and theory development.

Findings

We sought to examine the following research question: What is the process that mobilizes Asian American activists to pursue thick solidarity with the BLM movement in 2020? The results of the grounded theory analysis describe the process through which causal conditions, contextual factors, and intervening conditions affect actions and foster pathways to consequences following the core category of the phenomena of interest (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Grounded Theory Outlining AAPI Process of Mobilizing in Thick Solidarity With BLM in 2020

Causal Conditions

Based on perspectives from participants, two causal conditions led participants to mobilize toward solidarity for BLM in 2020.

George Floyd’s Murder

Exposure to George Floyd’s murder through social media and news outlets was the first causal condition. For each of the participants, this event represented the “breaking point,” “threshold,” “spark,” or “tipping point” that illuminated the need to “act,” “pursue justice,” “make change,” and “fight back.” As stated by Gemma, a Filipina woman in her mid-30s:

When George Floyd died . . . I just refused to be silent about what happened to him. I just kept thinking, well, what the hell have I been doing that it didn’t impact enough change [so] that this man could have lived? This man died because we have not done enough. He died calling out for his mom. What I could not handle was if I had been born with a particular fear, and I died that way. This man was born and lived knowing that he could be murdered by the police. And that’s how he died. I refuse that. And I am personally responsible that the narrative has not changed in this country. I am responsible and I hold my communities responsible. We have not done enough so that man could have lived.

Experiences of COVID-19–Related Anti-Asian Discrimination

The second causal condition was identified as experiences of COVID-19–related anti-Asian discrimination. This condition was characterized by witnessing or experiencing broad anti-Asian discrimination and exposure to “Trump’s Anti-Chinese,” “xenophobic,” and “racist messages.” Participants described how anti-Asian rhetoric touted by political leaders and experiences of anti-Asian discrimination served as “tinder” that “incited,” “enraged,” and “irritated” AAPIs in ways that “primed” them to act.

For each of the participants, witnessing and/or experiencing COVID-19–related racism was an event that led to action. Each of the 25 participants stated that exposure to anti-Asian discrimination cultivated empathy for Black Americans and illuminated how their shared experiences of racial discrimination “opened their eyes,” “woke them up,” or “pulled off the blindfold” of their racialized identity as Asian Americans. Yuri, a Chinese and Vietnamese woman in her early 30s, explained:

We have this fresh memory of discrimination in the back of our heads, and you know, it reaches a boiling point. You have the intersection of your own experiences and somebody else’s experiences and you start to connect the dots that we are not so different. And we are not so safe. We have more in common with Black lives than we do with White ones.

These sentiments were echoed by Hunter, a Korean man in his early 50s:

The pandemic created this anti-Asian reality. It really brought attention to the average Asian American [about] how much anti-Asian sentiment is still out there. You know, we all live in our little bubbles in life. And we don’t really see what’s going on. But I think, you know, seeing all these news stories about anti-Asian violence, whether we are members of the older generation reading our ethnic papers or just, you know, a member of the younger generation watching television, we see this stuff on the news and it has kind of served as the kindling to the fire to act and do more.

Evelyn, a Filipina woman in her early 40s, also described how exposure to anti-Asian rhetoric touted by political leaders primed her to act:

This particular president [Trump] is stoking the flames [and] it’s re-energizing a particular base of people who are emboldened to say and do things that are hate-centered, that are violent, that are wrong. And I think that it also touched on a particular powerlessness that Asian Americans have felt. And when you couple that within a global pandemic you are hyper aware of your mortality. You could die from this virus that’s going around, [and] we are all wearing masks. You couldn’t get more on edge, you know? We were primed to act. We were ready.

Josie, a multiracial woman in her mid-30s, explained:

Yes, we’re being harassed. We’re being called names. We’re experiencing another wave of xenophobia and racism, being told to go back to our countries, being told that we are not welcome here. I believe that Asians are saying, “Okay, yeah, we’re being threatened, but we’re not being held to the ground and choked out to the point that we’re being killed on TV.” I believe it’s awakened a lot of levels of pain and solidarity because you can’t imagine it. People can’t imagine that the world is this bad until someone’s last breaths are on TV. I think it mobilized people to become more involved because injustice does not have a place among any minority group. Injustice resonates with the Brown community, the Latinx community, the Asian community, and I believe it empowered us to move toward human empathy. Asians are realizing that if we don’t stand together, we stand alone, and nothing in this world will change.

Contextual Factors

Contextual factors were the individual traits and characteristics that affected the actions taken by participants to pursue mobilization in solidarity with BLM. Participants described three contextual factors: (a) alignment with personal and community values, (b) awareness and knowledge, and (c) perspectives of oppression.

Alignment With Personal and Community Values

The first contextual factor was defined as alignment with personal and community values. Notions of values alignment were identified in interviews when participants described how supporting the BLM movement was not a choice; rather, “protesting,” “supporting,” “fighting,” and “engaging in human rights activism” represented “values,” “moral imperatives,” and “needs.” Each of the participants described how mobilizing toward thick solidarity with the Black community reflected the direct consequence of one’s own set of values. Hunter shared the following: “Regardless of how it benefits the Asian American community, for me, it’s my sense of value. This is my own value system. I don’t feel comfortable having groups that are continuing to be oppressed.”

For some participants, notions of values alignment and the need to act had been socialized and were shared by their families of origin. José, a Filipino man in his early 30s, indicated:

I needed to act, there was no other choice. My parents taught me years ago how this whole [BLM] movement creates an obligation to speak up when injustice occurs. Our [Filipino] history has led us to learn that we always have been stronger when we all unite together because there is so much divisiveness in our society.

Evelyn described how values alignment represented a moral imperative:

For about 17 years, I have been an activist. I have always known at a very deep, personal, soul level, that issues of race are the knife on the throat of this country. This country has not resolved or has even come close to reconciling its history. And I don’t think that it [supporting BLM] was something that I decided. It wasn’t a neuron movement. It wasn’t a shift; it wasn’t something that physiologically or intellectually or cognitively shifted. It was like something else just shed, like a skin was pulled off me. It was just so plainly obvious that it was more than overdue for people to say something. We needed to act. There was no other option. It was just this plain, visceral refusal to be silent.

Participants described how alignment with personal and community values emerged because other Asian countries have been historically oppressed. Specifically, Hong Kong, Vietnam, and the Philippines were identified as countries that “silenced Asian voices” in ways that amplified participants’ desire to underscore their values in the United States. Byron, a Vietnamese and Chinese man in his late 30s, identified the following perspective on contextual factors:

I think it’s very important for us, as Asian Americans or even Asians across the world, to really be vocal on this [BLM movement]. Because, dude, America is a crazy place. It’s a beautiful country, but at the same time, the system is kind of jacked, right? And, you know, my parents being from Vietnam and really trying to get away from communists and stuff, I see what the Hong Kong people are going through right now. That to me is like a sign. Like, their battle is different from ours, but it’s still the same. We need to fight for what’s right.

Awareness and Knowledge

The second contextual factor was identified as awareness of one’s identity as a person of color and knowledge of how all communities of color are affected by systemic racism and White supremacy. Participants described how learning about Asian American history and the impact of racial triangulation, how AAPI liberation is directly tied to Black liberation, and the weaponization of the model minority myth were critical factors that contributed to their BLM activism. Rufio, a Filipino man in his late 20s, recalled the following memory:

Peter Liang, I think, was the first person that got convicted of anything. I clearly remember a street. On one side of it were Black protesters and on the other side were Asian American protesters. One side was saying, “Peter was innocent!” and the other side was like, “He deserves more of a sentence!” African American and Asian American protesters were pointing at each other when really they should have been looking outside [of] the situation and being like, the people in power set this game up so we didn’t look at them. They were making us look at each other, but we shouldn’t be looking at each other. We should be looking at them.

Participants identified the importance of achieving multiracial unity and described how the fates of communities of color are inextricably linked. Jay, a non-binary Filipinx person in their early 20s, asserted the following about multiracial unity:

When we center the most vulnerable or the most marginalized, then we are able to lift up everyone. And I think that’s why a lot of people are focusing on the term BIPOC and [are] like, trying to center Black people and Indigenous people, because Black people have been enslaved and Indigenous people [have] had so many atrocities committed to them on stolen land. Ultimately, we are all in this together and what we do for one affects us all.

Similarly, Dante, a transracially adopted Taiwanese man in his mid-20s, observed the political implications surrounding race relations in the United States:

Honestly, I think that four years of the Trump presidency is probably a big mobilizing factor. His policy towards China has been just straight-up racist on his best days and, you know, far worse on his bad days. And so one of the concerns that I had is like, he has no problem locking up kids and immigrants in detention centers. At what point is that going to start being directed at Asian people? If we don’t fight for other people of color, who’s going to fight for us when it is our turn?

Jubilee, a Chinese woman in her early 30s, described the recent AAPI support of BLM and emphasized the importance of cultivating awareness and knowledge with her community and family of origin:

I feel like this is the first time I’ve seen such solidarity from Asians to the Black community. It happened back in the 60s during the civil rights movement so like, we are not the first, but like, in my generation and in my lifetime, this is the first time I am seeing that from us as an Asian community. There are finally conversations coming up about anti-Blackness in Asian communities, you know? It has also allowed me and my brother to bring up these conversations and issues with our friends and parents. For the first time in our lives, we are having conversations about anti-Blackness and systemic racism, and they are not brushing it off. They [my friends and parents] actually take a pause and listen, and this was the first time seeing them do that. And that’s pretty cool. There’s still a long way to go, but there is definitely some change happening. I see it and I feel it around me.

Perspectives of Oppression

Participants conceptualized their experiences from two distinct perspectives of oppression that uniquely influenced the strategies used to mobilize in thick solidarity toward the BLM movement: (a) as a member of the AAPI community or (b) as a member of a greater community of minoritized groups. Participants who limited their perspective of oppression to the AAPI community tended to center Asian voices in support of the BLM movement (i.e., “Yellow Peril for BLM”). Participants in the first category tended to limit their focus to how supporting the BLM movement would benefit the Asian community. Byron explained how supporting the BLM movement better positions the greater Asian American community to engage in advocacy:

I think us mobilizing together and supporting the Black Lives movement would really help us out as a community. Not only as just Chinese, Vietnamese, and Filipino and all that, but literally, as one Asian community. I think we are learning from the Black Lives movement. Not only are we participating with them, but it’s almost like training wheels for our community to be like, we need to be louder about certain rights that we want or certain things that we want to talk about. The United States has created the perfect platform for us to express that, and we have not utilized that.

Conversely, participants who endorsed a wider perspective that recognized Asian Americans as members of one oppressed minoritized group centered the Black community and amplified Black voices. Participants in the second category were more likely to recognize how mobilizing in thick solidarity with the BLM movement would benefit the larger constellation of communities of color. June, a Korean, non-binary, transracially adopted person in their late 20s, highlighted this connection across social movements:

So many Asian people don’t want to post about anti-Asian oppression alongside Black Lives Matter. They are like, “Oh I don’t want to take away from the Black Lives Matter movement by posting about the racism that I experienced or by posting about immigration.” But I kind of see them as being connected because we all face the same oppressor. We are all dealing with White supremacy, so we need to realize all of our movements are interconnected. We need to be in solidarity with each other.

Mia, a Korean woman in her early 30s, similarly explained this relationship:

Just like how we wonder, How is discrimination affecting the greater Asian community?, I think you have to extend that exercise to, How is it affecting the Black community? Where is it [discrimination] starting from? Whose lives are affected? Instead of just being like, “These are the discrimination experiences I face in my life,” it becomes a bigger conversation about what our greater community of minorities faces.

Intervening Conditions

Intervening conditions represent the broad and general factors that influence strategies based upon action or inaction and may include time, space, culture, history, emotions, and institutions. In this study, Asian American participants described four intervening conditions that either facilitated or created barriers to mobilizing toward thick solidarity with the BLM movement. Intervening conditions were described as having a bidirectional nature with the contextual conditions and action strategies used by participants.

Affective Responses

Participants described how feelings of “fear,” “anger,” “helplessness,” “empathy,” and “compassion” intersected with George Floyd’s murder, experiences of COVID-19–related anti-Asian discrimination, alignment with personal and community values, awareness and knowledge, and perspectives of oppression. Nearly every participant identified how they had “struggled” with, “overcome,” or “witnessed” how Asian Americans become paralyzed by fears of “taking up space,” “being too privileged,” or “not sharing the same intensity of oppression as Black Americans.” June described how some AAPIs become too overwhelmed by their privilege to engage in activism:

I so often hear them [AAPIs] say, “I want to help, but I can’t do anything. I can’t, I can’t. I don’t feel it’s in my place because I’m not Black. I feel like my voice doesn’t matter in this situation because I don’t suffer in the way that they [Black Americans] do.” I’ve seen so many excuses about how their voices are too privileged to matter, and it’s not true.

Annie, a Vietnamese woman in her early 30s, explained how fear can limit action:

They [AAPIs] fear that if they stand with the Black community, they will be ousted, attacked, treated differently, and looked down upon. I’ve seen a lot of fears that family would disown them if they become more vocal about Black Lives Matter because the older generation is very stuck in their own mindset of teaching the younger generations, you know, “You keep your head down, you go to school, you make a life for yourself, you don’t make waves, because it will only ruin your life.” I’ve seen a lot of people say that they can’t be as vocal because they are only one person.

Intergenerational Conflict

Participants identified intergenerational conflict as the second intervening condition that influenced Asian American action or inaction. Each participant described how Asian Americans and Asian immigrants (especially older individuals) lacked social justice–oriented language and stressed the importance of assimilation, and how those influences affected the shifting realities between first-generation Asian Americans and subsequent generations in their support of the BLM movement. Conversely, Asian Americans who were willing to engage in discussions about racial discrimination and cultivate cross-racial relationships were more likely to mobilize toward thick solidarity with the BLM movement. Participants also described how older Asian Americans and Asian immigrants struggled to grasp the “cultural nuances” that contextualize the history of systemic oppression and police brutality on Black and Brown individuals in America. The cultural barriers for many older Asian immigrants were described by Lin, a transracially adopted Korean woman in her early 30s:

The social justice language that we use when it comes to Black Lives Matter is difficult enough for a White person who is unfamiliar with this terminology. [It’s hard] to try and communicate that across generational lines, especially because a lot of us don’t have the strength in language skills to be able to translate. From what I’ve observed in my parents, they’ve kind of just kept their head down. They stressed assimilation very strongly for their children. It’s that old-school, “don’t rock the boat” mentality. Don’t give them a reason to look at us. Don’t give them a reason to hate us, you know? Don’t do anything to jeopardize this freedom that they worked so hard to achieve [and] that we’re so lucky to have.

Participants also described how first-generation Asian American and Asian immigrants were more likely to be “encapsulated,” “avoid other racial groups,” and “keep to themselves” in ways that prevented the cultivation of meaningful cross-racial relationships and kept them from challenging historical anti-Black sentiments. The importance of connecting with other communities of color to foster empathy and challenge historical anti-Blackness among Asian Americans and Asian immigrants was described by Ira, a multiracial woman in her early 70s:

I think that when older Asians are exposed in even a small way to the African American community, they can understand. But many Asian people stay within people of their own color, and they stay within their own ethnicity and they stay within their own groups. If you stay in your own community and you never see an African American person except [for] what you see on TV, it’s hard to see the similarities and realize that we are not so different.

To complement this notion, Jenny, a multiracial woman in her early 40s, discussed this perspective:

I feel like it’s really common for Asian immigrants not to connect with these situations [of discrimination] that are happening to them, either in individual instances or in bigger systems. They’re not tying them back to racism. I think that for so long, you know, immigrants were just trying to survive. First-generation folks were just trying to keep their head down, stay out of trouble, and survive, and they couldn’t get distracted by thinking about what else was happening around them.

Conditioning of “Privileges” Afforded by White Supremacy

The third intervening condition was coded when participants described how being Asian American represented “conditional,” “unsafe,” and “hyphenated” identities and when proximity to Whiteness elicited confusion about their role in activism. For some participants, the conditioning of “privileges” afforded by White supremacy contributed to action. As described by Evelyn, Whiteness elucidated a system of different racialized experiences:

I begin to wonder how powerful is Whiteness, you know? If I’m not the one being killed in the street, but I’m also experiencing racism, where do I fit into all of this? You begin to question how Asian Americans have been inserted into this narrative. And for me, you begin to wonder like, am I a pawn in this? What is my level of responsibility here? Is there a shared oppression? Yes. Are we all tethered the same way? No.

Participants who struggled to overcome the conditioning of privileges afforded by White supremacy were more likely to vacillate between action and inaction. Monica, a transracially adopted Korean woman in her early 30s, stated the following:

I do feel like for Asians, you’re in this really interesting space. I do actually think I have a lot of privilege. And with that, potentially, some responsibility as a person that essentially has a long-standing visa or passport into Whiteness. I know the language. I know how White people think and act. I feel like I can talk to White people about racism in a way that other people don’t necessarily have access to. But also, I experience racism and I’m also really tired.

Organized Communities

The presence of social media groups; local, regional, national, and international groups; participants’ own Asian American communities; and other communities with shared group identities (e.g., the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender [LGBT] community) were identified by participants as the fourth intervening condition. When organized communities were present, they either hindered or fostered mobilization. Participants who had communities that hindered mobilization described how their families and Asian American communities socialized them “not to rock the boat,” raised them to “keep their head down,” and discouraged “making waves.” Participants who lacked the presence of organized communities described feeling “burned out,” “alone,” and “unsupported.” As reported by Andi, a non-binary Korean person in their late 20s:

I have been fighting alone for years and it’s exhausting. I carry on because our activism is important, but it would be so nice to be able to meet up with other groups, share our experiences, and fill our validation cups, you know? It’s like, there is only so much I can do alone, and I don’t have the support I need to really keep going.

Participants described how communities fostered mobilization by providing the language, structure, resources, validation, and space necessary to begin talking about race and understanding the plight of other communities of color. Communities that fostered mobilization were most frequently described as college and university settings. Jackie, a Chinese and Japanese student in her mid-20s, described how her Asian American community on the university campus fosters action:

I just didn’t want to be by myself and protest alone. It feels good to learn more about why we are doing this and why it is important. Now, I felt like I have learned why it was so important that we as a group are able to rally behind the Black Lives Matter movement. I think community plays a huge part in supporting the BLM movement. It’s not just enough for us as individuals to be moving forward, it’s important that we have an Asian community presence in this battle.

The fostering role of communities in promoting thick solidarity was further described by Trichelle, a Chamorro woman in her late 50s:

I think the college and university experience has helped facilitate an understanding about race, generally, and experiences as Asian Americans or Pacific Islanders, secondarily. They facilitated an ability to see the connections, both the differences and the similarities of how racism has impacted AAPI communities but also how it is linked to the experiences of Black folks. The ability to have the language and to have some kind of infrastructure is critical to mobilize. Mobilization does not happen in the absence of some kind of organizational infrastructure.

Actions

To understand this larger process of action, participants in this study described non-action, performative action, or action toward thick solidarity. Participants additionally described how contextual factors, causal conditions, and intervening conditions interacted to influence the type of actions that occurred.

Non-Action

Non-action occurred when Asian American individuals were unable to challenge collectivistic notions of “not rocking the boat,” “not making waves,” and “not causing trouble.” Non-action was also more likely to occur when Asian Americans became overwhelmed by the economic and social privilege afforded to them because of their proximity to Whiteness. Upon considering the distinctness of Black oppression, participants described recognition of how Asian Americans may feel “unable,” “unsupported,” “guilty,” or “ineffective” to engage in action because of burnout; lack of community, validation, support, or resources; or feelings of “privilege guilt.” Participants also described how non-action may occur in older generations and Asian immigrants who may have internalized model minority traits, emphasized the importance of assimilation, remained encapsulated within the Asian American community, or lacked an understanding of systemic racism and social justice language.

Performative or Unhelpful Action

Performative or unhelpful action occurred when Asian American individuals either felt compelled to act to avoid being perceived as anti-Black or because supporting the BLM movement was “trending.” Unhelpful action occurred when Asian American individuals centered their issues in ways that disenfranchised Black issues or centered AAPI voices over Black voices (i.e., Asians4BlackLives). June described an example of how Asian American individuals may engage in performative action: “They’ll say one or two things online, and they’ll be like, ‛Oh, I did my part. I posted #BlackLivesMatter. Look at my profile picture. Look at my Instagram. Look, I posted a couple links for donations.’”

They also explained how centering AAPI voices constituted unhelpful action:

When someone posts “Yellow Peril Stands for Black Lives,” you’re actually overshadowing Black Lives Matter. Taking our title, our movement, and placing it in front of BLM says, “Hey, we’re here. We’re standing with you. Look at us.” That’s not acting in solidarity. It becomes one group saying, “I AM HERE. Here’s my voice for your voice.” We need to make our voices strong for theirs. We are the chorus and they are the lead singers.

Action Toward Thick Solidarity

Action toward thick solidarity occurred when Asian American individuals were able to support the BLM movement without centering AAPI issues or focusing on their own racial trauma histories. Demonstrating a willingness to learn how to be an ally and cultivating cultural humility were effective strategies in transcending action from performative or unhelpful to action toward thick solidarity. Sari, a Chinese and Lebanese woman in her early 30s, described the process of acting toward solidarity and the importance of communities that foster mobilization:

Solidarity to me is not a noun. It is a process that you continue to refine and reflect on and add or subtract things to, and it has a lot to do with your perspective and your approach. And I think a lot of solidarity with others comes from a genuine dedication to building your own community. I think a really important piece of solidarity is that introspection and community building with your own ingroup.

José explained how acting toward thick solidarity requires Asian Americans to follow the lead of Black activists. He tells the following story of how he explained allyship to a friend:

Remember two summers ago when you asked me to help you fix your deck, and I never knew how to work with power tools? The weekend before, I went on the internet and learned basic skills like how to hold a tool and how to be safe. And then when I went to your house, I wore a hard hat. I had everything ready, and I followed your lead and your leadership. That’s how you become an ally. You educate yourself. And when you go to situations you don’t center yourself. You follow the person who has the most experience.

Phenomenon, Consequences, and Core Category

Participants in the study described the process of feeling “primed” to act because of the combined causal conditions of George Floyd’s murder and experiences of COVID-19–related anti-Asian discrimination. Participants were able to mobilize because of the contextual factors of alignment with personal and community values, awareness and knowledge, and perspectives of oppression. The phenomenon of Asian American activists mobilizing in thick solidarity with the BLM movement were influenced by intervening conditions, which included affective responses, intergenerational conflict, conditioning of “privileges” afforded by White supremacy, and organized communities. Each of these conditions and factors interacted to influence non-action, performative or unhelpful action, and action toward thick solidarity.

Participants identified the consequences of pursuing thick solidarity with the Black community as resulting in pathways that facilitate three domains: (a) to promote intraracial and interracial healing, (b) to commit to personal and community values as well as human rights initiatives, and (c) to restructure policies and redistribute power. Within this study, “achieving a collective oppressed identity” occurred most frequently in participant narratives, experiences, and practices and was identified as absolutely critical for mobilization to occur. The core category of achieving a collective oppressed identity arose as a result of George Floyd’s murder, because of experiences of COVID-19–related anti-Asian discrimination, and in the light of awareness and knowledge.

Discussion

A grounded theory analysis with 25 diverse individuals outlined an emergent process describing how contributing factors mobilized Asian American activists toward thick solidarity with the BLM movement in June and July 2020. Understanding and abstracting this theoretical process is important to embolden other Asian American individuals to engage in collective social action. Components of the emergent process are consistent with the CIIM (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000) and supplement additional studies that explored AAPI support for the BLM movement (Lee et al., 2020; Merseth, 2018; Yoo et al., 2021). Specifically, the theoretical process that emerged from this study illuminates new findings that indicate how achieving a collective oppressed identity and contextualizing the historical relationship between the Asian American and Black communities are critical to empowering AAPI communities to form racial coalitions (Chang, 2020; J. Ho, 2021). For many participants, understanding this history and becoming more racially conscious propelled their motivations for achieving solidarity and dismantling the forces of White supremacy that oppress all racialized groups. This finding reveals numerous perspectives that value historical context and knowledge as a central factor for AAPI activism, especially in tandem with other communities of color (Museus, 2021; Nicholson et al., 2020).

Participants in the study identified how George Floyd’s murder and their experiences of anti-Asian discrimination resulted in an achieved collective oppressed identity that contributed to their mobilization toward thick solidarity with the BLM movement. This finding is consistent with extant research that hypothesized how ingroup discrimination may cultivate increased empathy, positive attitudes, and a collective sense of greater community (Craig & Richeson, 2012; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). The ways that causal conditions identified in this study led to a collective oppressed identity may further be explained through the lens of the CIIM model (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000), which posits that experiences of racial discrimination can engender positive attitudes and feelings of closeness to other racial minorities. The findings of the study additionally complement earlier studies on AAPI support for BLM that identified race-based linked fate beliefs among Asian Americans as a predictor of BLM support (Merseth, 2018), and an ethnography that identified the importance of organized educational communities for Southeast Asian Americans engaging in activism (Lee et al., 2020). Another possibility may be that participants in the study achieved a dual identity. As explained by Gaertner and colleagues (1994), dual identity occurs when individuals perceive themselves as members of different ethnic or racial groups “playing on the same team” (p. 227)—in this case, to dismantle the forces of White supremacy that continue to oppress all communities of color. The findings from the present study further elaborate on processes that may outline how anti-Asian discrimination can create the impetus for mobilizing in thick solidarity with the Black community (Anand & Hsu, 2020; Li & Nicholson, 2021; R. Liu & Shange, 2018; W. Liu, 2018).

Implications From the Study

The findings from this study can be used by mental health professionals and counselor educators to engage in meaningful racial dialogues and foster interracial coalitions. Specifically, professional counselors can employ this grounded theory to help Asian Americans heal from their own racial and intergenerational trauma by supporting other communities of color. The process of action outlined in our study illuminates the importance of promoting awareness and knowledge about the history of Black and AAPI oppression (Chang, 2020; J. Ho, 2021), connecting AAPI individuals to supportive communities (C. D. Chan & Litam, 2021; Yi et al., 2020), and providing helpful resources (e.g., Letters for Black Lives) and strategies (e.g., exposure and connection with other communities of color) to navigate cultural barriers (Arora & Stout, 2019).

Mental health professionals and social justice advocates can apply these findings to promote engagement in community organizing efforts of AAPI communities with the BLM movement, denounce anti-Blackness, and uphold culpability in supporting the Black community. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, AAPI individuals may experience greater rates of racial discrimination and anti-Asian rhetoric in ways that negatively impact their well-being (C. D. Chan & Litam, 2021; Jeung & Nham, 2020; Litam, 2020; Litam & Oh, 2020, 2021; Litam et al., 2021). Mental health professionals can validate these experiences of oppression and help clients redirect affective experiences in ways that promote awareness and knowledge (David et al., 2019; Museus, 2021), challenge proximity to Whiteness (Poon et al., 2016; Yi et al., 2020), and cultivate meaningful action in racial solidarity movements (Chang, 2020; Litam, 2021; Yoo et al., 2021). Helping Asian American individuals find communities that foster action toward thick solidarity with BLM and exploring how affective experiences influence accountability may be helpful in garnering support. For example, mental health professionals can explore whether limited perspectives of oppression and assimilation strategies may result in inaction or performative action, especially in directly challenging Whiteness (Chang, 2020; Yoon et al., 2016) or intentionally taking accountability for harboring anti-Black sentiments (Museus, 2021). This consideration is especially crucial as AAPIs build long-term solidarity as a proactive approach to Black solidarity rather than a temporary measure. Finally, mental health professionals may encourage AAPI individuals to expand their perspectives to include dual identities as AAPI people and as members of a greater group of oppressed minoritized individuals to foster racial coalitions.

Limitations

First, participants self-selected into the study with a strong working knowledge of their activist and AAPI identities. Readers must therefore be judicious about transferring these findings to AAPI individuals whose activist and/or racial identities may not be fully developed. Second, participants represented a small sample of a larger Asian American community that endorses varying views about activism, anti-Blackness, and other human rights issues. Notably, the sample only included one person with Pacific Islander heritage. Although the importance of thick solidarity continues to gain traction, readers must caution themselves against interpreting these perspectives as a monolithic viewpoint held by all AAPI individuals.

Recommendations for Future Research

The limitations of the study yield additional opportunities to build upon empirical research that illuminates racial coalitions, particularly among communities of color. With the findings of this study, it would be helpful to elucidate critical developmental points that shift AAPI communities into racial consciousness of White supremacy. This developmental point may be complex, given different histories of regions within the United States, migration histories, acculturation rates, and racial socialization within families. Similarly, White supremacy seeks to homogenize AAPI communities as a single racial group solely characterized by educational and economic success (Museus, 2021).

Built upon the premise of this study, it behooves researchers to address how anti-Blackness persists within AAPI communities (Yi et al., 2020; Yoo et al., 2021). Because only one participant had Pacific Islander heritage in the current study, researchers can further explore how Pacific Islanders may (a) endorse anti-Blackness, (b) experience the nexus of racism and colonialism, and (c) shape their commitments to solidarity with Black communities. Based on the themes underpinning the process toward thick solidarity in the study, it may be beneficial for researchers to consider the institutional conditions of their neighborhoods, communities, schools, and workplaces in promoting racial coalitions. Given that the study’s findings emphasized the importance of awareness and knowledge, it would be helpful to engage in qualitative research that further explores how educators in the P–16 system (i.e., preschool to college) map their curriculum of Asian history to include knowledge of racial coalitions, White supremacy, imperialism, and colonialism. Further research may also examine how counselor educators address the complex and racialized experiences of Asian American and Black communities within graduate coursework. Additionally, it is imperative to expand on research that illuminates Black organizers, activists, and communities in racial solidarity movements and Black-Asian racial coalitions.

Conclusion

The results of a grounded theory with diverse Asian American voices illuminated how causal conditions, contextual factors, intervening conditions, actions, and outcomes mobilized Asian Americans toward solidarity with the BLM movement in 2020. Understanding these conditions are of paramount importance to overcoming anti-Black notions embedded within AAPI ethnic subgroups and challenging systemic forms of racial oppression that impact all communities of color.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Anand, D., & Hsu, L. (2020). COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter: Examining anti-Asian racism and anti-Blackness in US education. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Perspectives in Higher Education, 5(1), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.32674/jimphe.v5i1.2656

Arora, M., & Stout, C. T. (2019). Letters for Black Lives: Co-ethnic mobilization and support for the Black Lives Matter movement. Political Research Quarterly, 72(2), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912918793222

Blalock, H. M., Jr. (1967). Toward a theory of minority-group relations. Wiley.

Bonacich, E. (1973). A theory of middleman minorities. American Sociological Review, 38(5), 583–594. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094409

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2004). From bi-racial to tri-racial: Towards a new system of racial stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27(6), 931–950. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000268530

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2018). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America (5th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Brewer, M. B. (2000). Reducing prejudice through cross-categorization: Effects of multiple social identities. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 165–183). Erlbaum.

Chan, C. D., & Litam, S. D. A. (2021). Mental health equity of Filipino communities in COVID-19: A framework for practice and advocacy. The Professional Counselor, 11(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.15241/cdc.11.1.73

Chan, S. (1991). Asian Americans: An interpretive history. Twayne.

Chang, B. (2020). From ‘illmatic’ to ‘kung flu’: Black and Asian solidarity, activism, and pedagogies in the COVID-19 era. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(3), 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00183-8

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Charmaz, K. (2017). Special invited paper: Continuities, contradictions, and critical inquiry in grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917719350

Chou, R. S., & Feagin, J. R. (2016). The myth of the model minority: Asian Americans facing racism. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315636313

Clarke, A. E. (2012). Feminism, grounded theory, and situational analysis revisited. In S. N. Hesse-Biber (Ed.), Handbook of feminist research: Theory and praxis (2nd ed., pp. 388–412). SAGE.

Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2012). Coalition or derogation? How perceived discrimination influences intraminority intergroup relations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(4), 759–777. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026481

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

David, E. J. R. (2013). Brown skin, White minds: Filipino-/American postcolonial psychology. Information Age Publishing.

David, E. J. R., & Okazaki, S. (2006a). Colonial mentality: A review and recommendation for Filipino American psychology. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12(1), 1–16.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.12.1.1

David, E. J. R., & Okazaki, S. (2006b). The Colonial Mentality Scale (CMS) for Filipino Americans: Scale construction and psychological implications. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(2), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.2.241

David, E. J. R., Schroeder, T. M., & Fernandez, J. (2019). Internalized racism: A systematic review of the psychological literature on racism’s most insidious consequence. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), 1057–1086. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12350

Elias, A., Ben, J., Mansouri, F., & Paradies, Y. (2021). Racism and nationalism during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(5), 783–793. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1851382

Fanon, F. (1952). Black skin, White masks. Grove Press.

Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (2000). Reducing intergroup bias: The common ingroup identity model. Psychology Press.

Gaertner, S. L., Rust, M. C., Dovidio, J. F., Bachman, B. A., & Anastasio, P. A. (1994). The contact hypothesis: The role of a common ingroup identity on reducing intergroup bias. Small Group Research, 25(2), 224–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496494252005

Gergen, K. J. (2020). Constructionist theory and the blossoming of practice. In S. McNamee, M. M. Gergen, C. Camargo-Borges, & E. F. Rasera (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social constructionist practice (pp. 3–14). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529714326.n1

Gergen, M. (2020). Practices of inquiry: Invitation to innovation. In S. McNamee, M. M. Gergen, C. Camargo-Borges, & E. F. Rasera (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social constructionist practice (pp. 17–23). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529714326.n2

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. SAGE.

Haney López, I. (2006). White by law: The legal construction of race (10th ed.). New York University Press.

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings. Guilford.

Ho, F., & Mullen, B. V. (Eds.). (2008). Afro Asian: Revolutionary political and cultural connections between African Americans and Asian Americans. Duke University Press.

Ho, J. (2021). Anti-Asian racism, Black Lives Matter, and COVID-19. Japan Forum, 33(1), 148–159.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2020.1821749

Jeung, R., & Nham, K. (2020). Incidents of coronavirus-related discrimination. Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council. https://bit.ly/3bITRDE

Khan-Cullors, P., & Bandele, A. (2017). When they call you a terrorist: A Black Lives Matter memoir. St. Martin’s Publishing Company.

Kim, C. J. (1999). The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics Society, 27(1), 105–138.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329299027001005

Lebron, C. J. (2017). The making of Black Lives Matter: A brief history of an idea. Oxford University Press.

Lee, S. J., Xiong, C. P., Pheng, L. M., & Vang, M. N. (2020). “Asians for Black Lives, not Asians for Asians”: Building Southeast Asian American and Black solidarity. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 51(4), 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/aeq.12354