Charles F. Shepard, Darius A. Green, Karli M. Fleitas, Debbie C. Sturm

This qualitative grounded theory study is the first of its kind aimed at understanding the decision-making process of parents and guardians of transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) youth providing informed consent for their children to undergo gender-confirming endocrinological interventions (GCEI), such as hormone replacement therapy and puberty blockers. Using primarily intensive interviews supported by observational field notes and document review, this study examined the decision-making processes of a national sample of participants who identified as a parent or legal guardian of at least one TGD youth and who have given informed consent for the youth in their care to undergo GCEI. A variety of inhibiting and contributing factors were illuminated as well as a “dissonance-to-consonance” model that participants used to combine contributing factors to overcome inhibitors and grant informed consent. Implications for professional counseling practitioners are discussed, including guidance for direct services, gatekeeping, case management, and advocacy functions.

Keywords: transgender, gender-diverse, youth, decision-making, intervention

One of the more controversial topics currently addressed in professional counseling involves gender identity and access for gender-confirming interventions for transgender or otherwise gender-diverse (TGD) youth. Since academic journals began publishing studies of the experiences of people expressing what today could be considered gender expansiveness in the late 19th century (Drescher, 2010), there has been considerable struggle in Western culture to understand the constructs of gender identity and expression and the implications that these aspects of human development present for mental and physical health. In the United States, controversy around pathologizing TGD identity or normalizing and affirming it has influenced popular and professional opinions since the early 20th century (Drescher, 2010; Stryker, 2008). Within the past decade, TGD identity has been associated with pervasive patterns of mistreatment and discrimination across social, educational, occupational, legal, and health care experiences in the United States (James et al., 2016).

Transgender Health Care in the United States

TGD people have been shown to be overrepresented in populations associated with negative mental, physical, and social health outcomes, such as those suffering from suicidality and homelessness (James et al., 2016). Among transgender older adolescents and young adults, 25% to 32% have reported attempting suicide (Grossman & D’Augelli, 2007), while the national rate for attempted suicide is 4.6% (James et al., 2016). According to the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Homeless Youth Survey (Durso & Gates, 2012), LGBT youth comprised 40% of the populations served by 354 agencies serving homeless youth. Of the 381 youth that responded to the survey, 46% reported that they ran away from home because of family rejection of their affectional orientation or gender identity, and 43% reported that they were forced out by their parents because of their affectional orientation or gender identity.

According to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, TGD people have also had their access to health care limited by stigma and discrimination by health care providers (James et al., 2016). One-third (33%) of respondents reported experiencing at least one negative experience with a health care provider in relation to their gender identity, and nearly a quarter (23%) did not seek services for fear of being mistreated. One-third (33%) did not seek health care because of an inability to afford the cost of TGD-specific or other services. These disparities are among the many motivators of the current movement to make health care, and professional counseling in particular, more affirming of TGD people (Rose et al., 2019; Vincent, 2019).

Factors Influencing Rejection and Affirmation of TGD Identity

Factors that support the pathologization of TGD identity and behavior find their roots across a variety of intersecting segments of American society. One of the more prominent influencers of these practices in the United States has been religion (Drescher, 2010; Stryker, 2008; Vines, 2014). More than 70% of the U.S. population identifies as Christian, with more than half the population practicing Christianity as members of evangelical denominations, which have been associated with traditionally rejecting attitudes toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex, asexual, and pansexual (LGBTQ+) people and behavior (Pew Research Center, 2014; Vines, 2014). Chronic suicidal thinking among LGBT people ages 18 to 24 has been associated with parents’ rejecting religious beliefs, and fears about being forced to leave one’s religion have been associated with a suicide attempt within a 12-month period for the same population (Gibbs & Goldbach, 2015).

Religion has been closely associated with recent changes in state legislation and federal policy that suggest that disparities in the treatment of TGD people are socially and professionally acceptable. At least four states (Arkansas, Montana, Ohio, and South Dakota) have passed legislation that has included what is known as a conscience clause that could impede access to health care for LGBTQ+ people (Dailey, 2017; Goodkind, 2021; Rose et al., 2019). These health care–related laws have allowed legal protection for health care providers, sometimes specifically addressing professional counselors, who refuse services to clients who request help in ways that conflict with the provider’s particular religious beliefs (Dailey, 2017; Rose et al., 2019). In 2018, conscience clause–type considerations were expanded to the federal level when the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) created the Conscience and Religious Freedom Division (CRFD) in the DHHS Office for Civil Rights (DHHS, 2018a). At the time, CRFD policy explicitly cited protections for health care practitioners who declined to provide services related to abortion and assisted suicide (DHHS, 2018b); however, some noted that the division’s loose language could have left room for health care providers to deliver sub-standard care for LGBTQ+ clients as well (Gonzalez, 2018; Rose et al., 2019). In fact, a DHHS spokesperson stated at the time that the department would not interpret prohibitions on sex discrimination in health care to cover gender identity (Gonzalez, 2018). It should be noted that federal protections of TGD individuals in health care were restored in 2021 (Shabad, 2021).

Awareness of Gender Diversity

The general beginnings of the social consciousness of gender diversity in the United States can be traced to the attention that Christine Jorgensen commanded during her transition in the 1950s (Drescher, 2010; Stryker, 2008). Jorgensen was a U.S. Army veteran who served during World War II and travelled to Europe to undergo orchiectomy and penectomy procedures. Upon her return to the United States, she underwent vaginoplasty and became a preeminent advocate for LGBTQ+ rights (Drescher, 2010; Jorgensen, 1967; Stryker, 2008). About a decade later, physician Harry Benjamin pioneered gender-confirming endocrinological interventions (GCEI) aimed at medically supporting TGD patients who wished to feminize or masculinize their bodies to be more congruent with their gender identity without surgery (Drescher, 2010; Stryker, 2008). The most popular forms of GCEI—cross-sex hormone replacement therapy and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues or “puberty blockers”—have been associated with positive physical and mental health outcomes (Bränström & Pachankis, 2020; Couric, 2017; Drescher, 2010; Murad et al., 2010) and have been made available to people from pre-puberty through late adulthood (E. Coleman et al., 2012; Hembree et al., 2017).

Nearly all the research regarding GCEI has been conducted on adults (Couric, 2017), and the experiences of parents of TGD youth are not well represented in the literature (Hill & Menvielle, 2009), despite the growing popularity of GCEI among TGD minors (Couric, 2017; Drescher, 2010; Pew Research Center, 2013; Rosin, 2008). In the United States, minors are almost always dependent on their parents or legal guardians to provide informed consent for GCEI (Burt, 2016; D. L. Coleman, 2019; D. L. Coleman & Rosoff, 2013) even though they are likely to be considered by the medical profession to be cognitively capable of making an informed choice to undergo hormone-related treatments (E. Coleman et al., 2012; Hembree et al., 2017). At least one study that intends to contribute to the literature on the long-term risks and benefits of GCEI on minors is ongoing but not complete as of this publication (Bunim, 2015; S. Rosenthal, personal communication, November 7, 2019). This leaves both TGD youth and their parents—who are unlikely to share their child’s gender identity—in the precarious position of making meaningful decisions about the youth’s mental and physical health in a climate dominated by legal, political, religious, and social trends and without a body of rigorous research to instill confidence in giving or denying consent for GCEI.

Role of Professional Counselors

Partially for the reasons stated above, professional counselors who work with TGD youth and their families have unique opportunities to serve their clients at the micro-, meso-, and macrolevels. With professional emphases on human development, the helping relationship, and social justice (Lawson, 2016), counselors have an ethical obligation to develop competencies related to addressing issues concerned with gender identity, spirituality, and social systems to enable the empowerment of clients through individual, group, and family counseling in addition to interprofessional consultation and advocacy (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; Burnes et al., 2010; Cashwell & Watts, 2010; Ratts et al., 2015; Toporek & Daniels, 2018). ACA’s stance that TGD identity is a normal part of human development and should be affirmed (Burnes et al., 2010) aligns with the positions of every major health care professional organization globally (Drescher, 2010). Professional counselors are likely to be presented with opportunities to provide psychoeducation about gender identity development and best practices regarding the affirmative care of TGD clients as well as opportunities to advocate for their clients through the writing of referral letters for GCEI (E. Coleman et al., 2012). It is not uncommon, however, for professional counselors to challenge this obligation, especially when they feel compelled to prioritize religious teachings that pathologize LGBTQ+ identity (Kaplan, 2018; Rose et al., 2019).

The Purpose of the Present Study

The purpose of this research was to explore the process by which parents or legal guardians of TGD youth develop affirmative understandings and approaches to their children’s gender identity, affirm their related transition needs, and grant informed consent for the TGD youth in their care to undergo GCEI. With that in mind, the primary research question of this grounded theory study was, How did the parents of TGD youth who have undergone GCEI decide to give informed consent? Secondarily, are there specific themes that emerge for Christian, heterosexual, cisgender parents who go through this process? Finally, what part, if any, did a professional counselor play in the process?

Method

A qualitative grounded theory method was employed because this method is used to understand how participants go about resolving a particular concern or dilemma (Charmaz, 2014; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Unlike other forms of qualitative research, grounded theory guides the researcher with a set of general principles, guidelines, strategies, and heuristic devices rather than formulaic prescriptions to help the researcher direct, manage, and streamline data collection so that analyses and emerging theory are well grounded in the collected data (Charmaz, 2014). For the purposes of this study, we followed prescribed grounded theory protocols for data collection, analysis, and trustworthiness (Charmaz, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2015; Creswell, 2013; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Participants

Following IRB approval, a snowball sampling method (Creswell, 2013; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016) was employed to recruit a purposive sample of adult participants who (a) self-identified as a parent and/or legal guardian of a person who self-identifies as TGD and (b) have given informed consent for their TGD child to receive GCEI. Study information and a request for assistance with identifying participants was disseminated to national organizations that advocate for TGD rights such as the Society for Affectional, Intersex, and Gender Expansive Identities (SAIGE), Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG), and Transparent USA. Prospective participants were asked to contact the researcher and forward the information to others that they believed met the study criteria. Participant screening consisted of an online Qualtrics survey that included confidentiality and informed consent information, inclusion criteria, and demographic items. Once identified, participants were asked to participate in initial intensive interviews.

Theoretical sampling (Charmaz, 2014) is the preferred strategy for grounded theory because it allows emerging themes to direct simple decisions until saturation is met (i.e., no new information is being detected). In this study, saturation was met at the 16th interview and confirmed in the 17th. Table 1 details the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, the majority of which identified as cisgender women (n = 13), White (n = 16), married (n = 14), college educated (n = 17), and employed full-time (n = 12). Participants’ ages ranged between 32 and 61 years with a mean age of 49 (see Table 2). The participants made up a national sample (see Table 3), both in regard to region of birth and region of residence. As Table 4 shows, a near majority identified as mainline Protestant Christian (n = 8). The majority had one TGD child (n = 13), and the children’s ages at which the participants gave consent for GCEI ranged from 10 to 18 years (M = 13.93; see Table 2).

Instrumentation and Data Collection

Because the main emphasis of this study was to understand parents’ decision-making processes, intensive interviews were the main instrument of data collection. Environmental observation and document reviews were conducted when they were accessible. To protect the participants’ confidentiality, each was randomly assigned a pseudonym. Additionally, interviews—which lasted between 30 and 75 minutes—were facilitated through telehealth video conferencing software that complied with the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Electronic recordings of interviews were stored on a HIPAA-compliant version of an internet-based file hosting service, and transcription was provided by a company that provides confidential transcription services.

Table 1

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants

| Demographic characteristic* n % |

| Gender |

| Cisgender Women 13 76.5 |

| Cisgender Men 4 23.5 |

| Ethnicity

White 16 94.1 Mixed-race 1 0.1 |

| Marital Status |

| Married 14 82.4 |

| Divorced 2 11.8 |

| Separated 1 5.8 |

| Highest level of education |

| Some college 3 17.6 |

| Associates degree 2 11.8 |

| Bachelor’s degree 5 29.4 |

| Master’s degree 3 17.6 |

| Doctoral degree 4 23.5 |

| Employment status |

| Employed full-time 12 70.6 |

| Employed part-time 5 29.4 |

| Professional identity |

| Office/clerical 1 5.8 |

| Sales/marketing 2 11.8 |

| Professional 9 52.9 |

| Mid-level management 2 11.8 |

| Upper-level management/ 1 5.8 |

| business owner |

| Other 2 11.8

Household annual income More than $90,000 9 52.9 $60,001 to $90,000 6 35.3 $35,000 to $60,000 2 11.8 |

| Note. N = 17. *Participants were asked to identify across a variety of different gender identities, relationship statuses, educational statuses, employment statuses, professional identities, and income statuses. Only the identities or statuses selected by participants are shown. |

Table 2

Relevant Ages

| M | Range | |

| Current age of parents | 49 | 32–61 |

| Current age of TGD child | 15.78 | 10–26 |

| Age of TGD child at time of consent | 13.93 | 10–18 |

Table 3

Participant Regions of Birth/Residence

| Region | Place of birth | % | Place of residence | % |

| Northeast | 1 | 5.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 6 | 35.3 | 12 | 70.6 |

| Midwest | 3 | 17.6 | 2 | 11.8 |

| Southeast | 4 | 23.5 | 1 | 5.8 |

| Southwest | 1 | 5.8 | 1 | 5.8 |

| Mountain West | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.8 |

| Outside U.S. | 2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0 |

Note. N = 17

Table 4

Participant Religious Affiliation

| Affiliation | n | % |

| Christian (mainline Protestant) | 8 | 47.1 |

| Christian (Catholic) | 0 | 0 |

| Christian (Evangelical Protestant) | 0 | 0 |

| Muslim | 0 | 0 |

| Jewish | 1 | 5.8 |

| Agnostic | 2 | 11.8 |

| Atheist | 2 | 11.8 |

| Other/unaffiliated | 4 | 23.5 |

Based on Charmaz’s (2014) recommendations, the researchers developed an interview protocol (see Appendix) that was examined and confirmed for (a) its sensitivity to the experience of participants and (b) its capability for addressing the research questions at hand with two individuals who meet criteria for participation. One of the individuals was the executive director of a small, rural LGBTQ+ advocacy organization. The second was a professional counselor who works with TGD clients. Both were parents of at least one TGD child.

Analysis

The researchers used line-by-line coding of interview data and continuously compared new codes with those of previous interviews. Microsoft Excel software (version 16.44) was used for keeping track of the coding matrix. The coding matrix was reworked until a core theoretical category emerged that explained the underlying concepts inherent in the process under examination.

Trustworthiness

In qualitative research, a study’s rigor is typically measured by trustworthiness, or the consistency of the results with the data collected (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). To support this process, we used a variety of strategies, including triangulation, member checks, and reflexivity (Corbin & Strauss, 2015; Creswell, 2013; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Triangulation was accomplished by the recruitment of two study auditors who conducted blind coding of data samples and reviewed the study design, procedures, and process of theory integration for accuracy (Creswell, 2013). Reflexivity involves the “critical self-reflection of the researcher regarding assumptions, worldview, biases, theoretical orientation and relationship to the study that may affect the investigation” (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016, p. 256). The first author and lead researcher, Charles F. Shepard, identifies as a White, cisgender, straight, middle-aged man who has lived his entire life in the Southeastern United States. He has been married for more than 14 years, and he is the father of two young children who were assigned female at birth. Shepard’s interest in the present topic is rooted in personal, academic, and professional experiences with conscience conflicts during the past three decades. The second author, Darius A. Green, served as an auditor and identifies as a Black, cisgender, straight, young adult man who has lived predominantly in the Southeastern United States. Green is a doctoral-level counselor educator who has conducted research and provided counseling with underrepresented populations. The third author, Karli M. Fleitas, served as the second auditor and identifies as a Japanese American, cisgender, straight, young adult woman who has lived predominantly in the Southeastern United States. Fleitas is a doctoral student in a counselor education program accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs who has clinical experience working with LGBTQ+ clients as well as certification with respect to diversity, equity, and inclusion practices. The fourth author, Debbie C. Sturm, served as the chairperson of Shepard’s dissertation committee and provided guidance to the research and reporting processes. Sturm identifies as a White, cisgender, straight, middle-aged woman who has lived between the Northeastern and Southeastern regions of the United States. She has conducted and supervised previous research relevant to LGBTQ+ concerns. We considered our identities and backgrounds throughout for their potential effect on the data collection and analysis processes.

Results

The major findings of this study included inhibitors and contributors to consent as well as a central theme, specifically how participants combined contributing factors to overcome inhibiting factors of the consent-giving process.

Inhibitors to Consent

Participants identified five major inhibitors to giving consent: (a) lack of knowledge and awareness of issues and concerns related to TGD identity, (b) fear, (c) doubt, (d) grief over a lost parenting narrative, and (e) rejection from healthcare providers (or payors) and parenting partners. To a lesser degree, lack of access to affirming care due to residential location and the cost of treatments were cited as notable experiences of participants.

Lack of Knowledge and Awareness

Of the participants, all but one (n = 16) reported that they lacked knowledge or awareness of the issues that TGD youth face when their children either came out to them, asked to participate in GCEI, or both. When asked what she knew about gender identity and/or gender expression prior to her child coming out, Jaylene (51), a White, cisgender woman divorced from her parenting partner, but remarried and living in the Southeast, stated:

Really not a lot, because I think that transgender people in the past were really colored as men who were sick and dressed like women. . . . I was kind of ignorant to it all, but I didn’t know I was ignorant is the thing.

Participants often cited their lack of knowledge as a key component of their fear over giving informed consent for their TGD child’s GCEI.

Fear

Participants reported experiencing fear on multiple levels in response to their child’s request to begin GCEI, including fear of negative future social experiences for their child, fear of the side effects of the treatments, and political fears. Of the 17 participants, 13 reported fears over negative future experiences. Hilda (50), a White, cisgender woman married to her parenting partner and residing in the Mid-Atlantic region, said, “It’s scary as hell. It’s terrifying. . . . It’s not that I’m fearful of who she is, I’m fearful of what the world is going to do to her.”

Similar to fear of future experiences for their children, 12 participants cited fear of the side effects of their child’s requested GCEI. Camilla (46), a White, cisgender woman separated from her partner and living in the Mid-Atlantic region, had similar concerns, stating that she “didn’t have a whole lot of information on how testosterone, for instance, would affect [my child] . . . . It was a concern of, ‘How does that affect the long-term health of my child?’ That’s actually a question that I still have.”

Finally, at least six participants communicated that fear related to the political climate inhibited their decision-making process. Honour (43), a White, cisgender woman divorced from her parenting partner and residing in the Mid-Atlantic region, recounted that political fears affected her and her child’s decision to request a subcutaneous implant, saying:

The physician seemed surprised and said, “Tell me more about why that’s your first choice.” And (child) says, “We have a presidential election coming up, and I don’t want to be in a situation where I start monthly or quarterly shot treatments only to have that right taken away from me. If they put a 2-year implant in my arm, they’re not going to come rip it out.”

Doubt

Although fewer than half of participants (n = 6) expressed doubt in the genuineness of their youth’s TGD identity, doubt was still considered a main inhibitor because each participant who described their doubt gave vivid descriptions thereof. Berta (48), a White, cisgender woman married to her parenting partner and living in the Mid-Atlantic region, provided the following example that was indicative of the sample’s experiences:

It was scary at first because everybody goes to the same place, which is scared for your child. And then, you know, maybe this is a phase? Maybe he’s confused? Maybe—you know? And so, you go through all those things.

Grief Over a Lost Parenting Narrative

The most prominent inhibiting factor not directly related to lack of knowledge leading to fear or doubt was participants’ description of grief over their lost parenting narrative. A majority of participants (n = 9) reported that the change in their expected future with their child came as a result of learning that their child identified as TGD. Adele (32), a White, cisgender woman married to her child’s father and living in the Mountain West region, described an internal conflict consistent with her peers:

There’s this creeping in of grief. . . . Even if you should be able to adapt, it’s still there. When we make these choices for hormone therapy, it’s kind of a step further in the direction of whatever could have been will definitely never be.

Rejection

A substantial subset of participants (n = 8) reported experiencing what could be considered some form of rejection, either from a parenting partner or a health care provider or payor. Of the six participants who reported that their parenting partner demonstrated signs of rejection, all were cisgender women; however, only two reported that their parenting partner maintained their rejecting stance in a way that ultimately put informed consent at risk (for legal reasons). Mellony (49), a White, cisgender woman married to her child’s father and living in the Mid-Atlantic region, recounted an experience that was more typical in the sample:

My husband was a little slower, in the beginning, to get on board. I just think he had a harder time—you know, “Is this really real? Is this a phase? Did she learn it on the internet? What’s really going on?”

Three participants described what they considered to be rejecting messages and/or behavior from health care providers. In response to a question about how a mental health professional was involved in her decision-making process, Journey (51), a White, cisgender woman married to her parenting partner and living in the Mid-Atlantic region, said that meeting with a counselor was one of the worst parts of the process, and they walked out of the session early:

One of the things that was concerning me at the time was, “How do I tell my younger children.” And she said, “Oh, I wouldn’t do that. He’s probably going to change his mind.” And so we said, “Well, OK, there’s a lot we don’t know, but that’s not the right answer.”

Adele described denials of reimbursement from her child’s insurance company as well as unwelcoming responses from front-desk workers at the clinic at which they were seeking treatment: “They seemed incredibly—I don’t know how to word it—off-putting in that, we were like, ‘one of those.’”

Lack of Access

A subset of participants reported a lack of access to affirming treatment. Five participants reported a lack of access due to their residential location; three reported it was due to insurmountable financial cost. Some drove several hours away and across state lines so that their child could receive treatment. Sharyn (47), a White, cisgender woman divorced from her child’s father and living in the Mid-Atlantic region, recounted that her ex-partner’s reluctance to give consent affected the cost of treatment, stating, “All we could do was a prescription to stop periods, which [was] about three or four times more expensive than hormones.”

Contributors to Consent

Participants identified four factors that contributed to giving consent: (a) parental attunement to the experiences and emotions of the youth in their care, (b) parental autonomy from their family of origin and religious communities, (c) access to affirming education about TGD issues and GCEI, (d) the presence and/or development of affirming relationships and community, and (e) affirming religious beliefs and/or community.

Parental Attunement to Youth’s Experience

The construct of parental attunement has been defined as a relational dynamic between parent and child that surpasses what is typically included in the construct of empathy. Erskine (1998) posited that attunement is a two-part process that includes (a) the ability to sense and to identify with another person’s sensations, needs, and feelings: and (b) communicating that sensitivity to the other person. A parent’s ability to attune to their child’s experience and emotional world has been prominently associated with the fostering of secure attachment and personality development (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991; Bowlby, 1988; Siegel, 2013; Wallin, 2007). Participants in the present study conveyed their ability to demonstrate parental attunement by describing their wishes for their TGD youth’s social and emotional well-being as a primary motivator for granting informed consent for them to undergo GCEI. Furthermore, participants implied respect for their youth’s autonomy, their recognition of their youth’s gender non-conformity, and their recognition of their youth’s mental health symptoms. Participants also recognized their own position of privilege that facilitated granting consent and a sense of their own autonomy from their families of origin or religious backgrounds.

One of the more striking examples of parental attunement in this sample was provided by Tony (61), a White, cisgender man married to his child’s mother and living in the Mid-Atlantic region, who tearfully recounted a conversation with his then–16-year-old child following a support group meeting:

I said, “You know, what would really help me is, could you write down your goals, what you want, and be honest with everything. We want to support you.” So, after we got home, within about two hours, [child] brought me something that I still have. . . . It says “Trans with the Plans.” And that was when I knew that this kid I love so much knew what they wanted, and I had to support them.

A notable subset of participants (n = 16) reported that they recognized their child’s rejection of binary gender norms prior to their child coming out to them. This recognition often came during early childhood. Hilda remembered noticing her child’s “Sunday best”:

I had [child] in her little dress shirt and tie and dress pants, and I told her to go get her dress shoes, and her little face lit up. She ran down the hall and came back in those little Cinderella shoes—so, [child] was always [child]. It just took us awhile to catch on.

Every participant recounted a recognition of and concern for their child’s mental health. Prudence (46), a mixed-race, cisgender woman married to her child’s father and living in the Southwest region, said that her child “came to us in the middle of the night, and I said, ‘Are you feeling suicidal?’ He didn’t respond verbally, but he just started crying. So I just pulled him in bed with me and I snuggled him.”

Parental Autonomy From Their Family of Origin or Religious Communities

A less frequent, but nonetheless notable, sign of parental attunement to the experience and emotions of their child was participants’ descriptions of how they prioritized the wishes and needs of their child and demonstrated autonomy from their families of origin (n = 10) or religious backgrounds (n = 4). Berta recounted planning with her partner how to break the news of their consent to extended family members:

[When] we told extended family, I was making the phone calls, but [my partner] reminded me, he said, “Remember, this is not a terminal illness.” It could be, right, if you don’t do it right, but just say, “We’re not asking permission, and we are not apologizing.” So, he kind of like, you know, held me up when we made those calls.

Brenda (48), a White, cisgender woman married to her parenting partner and living in the Mid-Atlantic region, described her experience within a religious community that had members that were reluctant to openly lend support and others who wanted to offer support but lacked the necessary knowledge and skill to do so. In recounting what led her and her family to leave their congregation at the time, she stated:

I did chat about it to anyone who asked and had hoped to educate and affect some positive change from within, but lots of folks just weren’t ready or willing to have these conversations. Which was interesting because this was all during the time when the [denomination] was making high-level decisions about whether or not to affirm LGBTQ folks.

Access to Affirming Community, Education, Health Care, and Parenting Partnership

All participants made at least some reference to having access to affirming (a) community of parents, professionals, colleagues, and/or friends; (b) education; (c) health care; and (d) parenting partnership. A key element of access to an affirming community was participants’ acknowledgement of possibility models. This term, which participants credited to prominent transgender actor Laverne Cox, refers to a person who identifies as TGD and has successfully gone through a medical transition, or a parent who has successfully supported their child through a medical transition. Possibility models were referenced when participants spoke about their experiences with family friends, support group members, professionals, and members of the mass media.

Participants were all members of affirming communities, and they reported that they received affirming education from group members and health care providers, including professional counselors. Adele reported the following about the support her child received from an affirming professional counselor during the process toward GCEI:

This counselor met her where she was and was using interventions geared toward just expressing herself. And I think it helped her to externalize what was happening, and then also, she was able to talk about the things that she was going through . . . because it was a space where there was no pressure.

Several participants reported that the counselors or mental health providers who wrote referral letters for their youth to begin GCEI were often closely associated with support groups they attended, completed gatekeeping procedures efficiently and without unexpected fees, had TGD-affirming staff and office procedures in place, and did not necessarily focus exclusively on gender identity.

Affirming Religious Beliefs and/or Community

Nearly half the participants (n = 8) identified as mainline Protestant Christians (i.e., members of denominations that have historically rejected fundamentalist practices) and reported that affirming religious beliefs contributed to their decision-making process. Emma (56), a White, cisgender woman married to her child’s father and living in the Midwest region, provided a response typical of the sample regarding the role of religion in her decision-making process:

Jesus said we are children of God, and he did not define what a child of God looks like. God created this world to be diverse. Look outside, and you’re going to see it. We’re just living in that reality of being children of God.

Central Theme: From Dissonance to Consonance

Each participant described an initial expectation that their youth would identify, like them, as cisgender. When they recognized that their child’s gender expression did not align with those social expectations, each participant described experiencing some level of intra- and interpersonal tension. This phenomenon may also be understood by what is commonly known as cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957; Myers & DeWall, 2019). Like the construct of parental attunement described previously, the construct of cognitive dissonance borrows from the physics of music, in which the term dissonance is used to describe a lack of harmony. On the other hand, consonance is the term used to describe a combination of one or more tones of different frequencies that combine and result in a musically pleasing (i.e., harmonious) sound (Errede, 2017). Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory (1957) suggests that when faced with this type of mental tension, humans often bring their attitudes and beliefs into alignment with their actions (Myers & DeWall, 2019). The responses of the participants of this study suggest that this is an apt metaphor for their decision-making process.

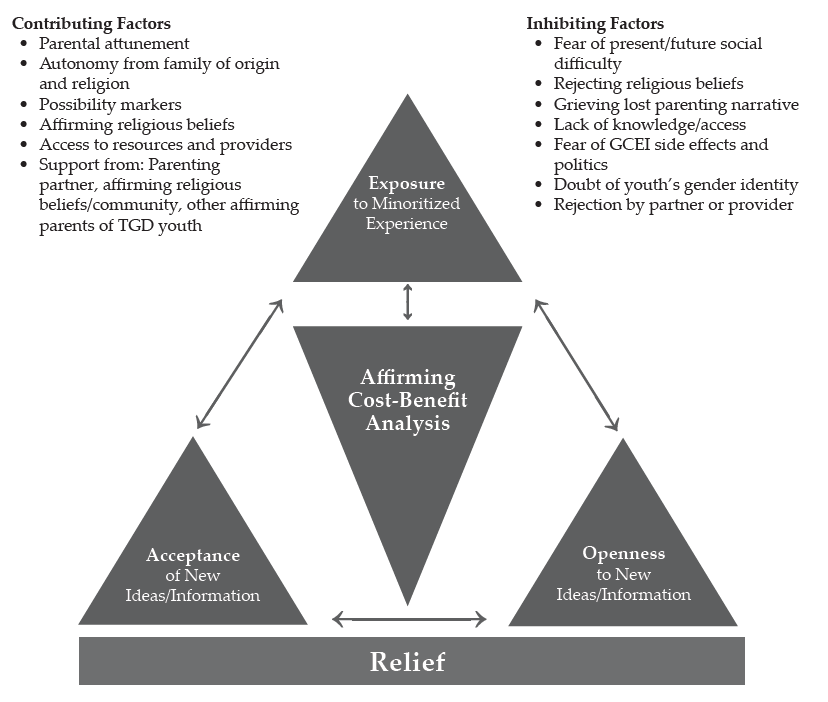

Each participant described 1) an experience of exposure to some form of human diversity prior to their youth confirming a TGD identity, 2) cognitive-emotional openness to new and TGD-affirming information, and 3) acceptance of the new and affirming information presented to them, followed by the participant 4) using the affirming information available to them to make an affirming cost-benefit analysis that led to the granting of informed consent and finally 5) feeling a sense of relief that they gave informed consent for their youth to undergo GCEI. Figure 1 shows a dissonance-to-consonance model of these mutually influencing central factors.

Exposure to Historically Minoritized Experiences

Each participant described previous exposure to some type of historically minoritized experience, whether it was as personal as identifying as a woman (as in Journey’s case), a professional experience, or knowing someone within their children’s social networks. Mellony reported personal and professional exposure, stating that a former colleague had come out as trans, “so I did know someone. I also knew another mom whose child had come out a couple years earlier, so it was not completely foreign to me.”

Openness

Each participant described generally open attitudes that led to parenting decisions ranging from the toys they gave to their child to seeking education. Adele recounted that her family “did a lot of research on our own. We had other parents and kiddos that [we] were able to talk to about what they were experiencing, and we heard from families about what the process looked like for them.”

Figure 1

A Dissonance-to-Consonance Model

Acceptance

Prudence provided an example of acceptance typical of the sample in that she not only accepted that the GCEI and other affirming practices would be beneficial, but she also arrived at a place where she wished she had started them earlier:

I often say [child’s given name at birth] was the vessel, [child’s name] is the soul. If I had known that, and understood it wasn’t a phase, I probably would have pushed to start so he didn’t go through puberty as a female.

Affirming Cost-Benefit Analysis

Berta provided a description typical of the sample regarding her and her partner’s affirming cost-benefit analysis that led to granting informed consent. She highlighted her access to a supportive community as well as her recognition of the mental health implications of a non-affirmed TGD identity for her child:

A parent who had come before me said there’s really nothing that you can’t reverse. You can wear a wig if your hair falls out. . . . If you start growing facial hair and then you decide you don’t want to, you can get electrolysis. . . . If you get your breasts removed, you can get implants. But what it really comes down to is do you want a dead kid, or do you want a kid that might be slightly altered? We looked at [our child] and thought, “You’re miserable, and if this will help you not be miserable, then we will go for it.”

Relief

Each participant expressed a sense of relief that they had granted informed consent, usually because they noticed improvements in their child’s moods and general sense of happiness. Lennon (55), a White, cisgender man married to his parenting partner and living in the Midwest region, provided a statement that was typical in the sample: “His mood changed. That was the key. I think the fact that we saw [child] become happier with it, that’s the key. That’s all that really mattered.”

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to explore the process by which 17 parents of TGD youth developed affirmative understandings and approaches to their children’s gender identity, affirmed their related transition needs, and granted informed consent for the TGD youth in their care to undergo GCEI. Based upon our review of the literature, there are no studies related to the process that the parents and guardians of TGD minors go through to give informed consent for GCEI. This research appears likely to inform best practice for professional counselors and other helping professionals serving TGD youth who wish to have an endocrinologically supported transition and those charged with giving informed consent for these interventions.

Implications for Professional Counselors

First, this research provides a plausible model for practitioners to follow when presented with the challenge of supporting parents of TGD youth as they work to develop affirming attitudes and support their respective children’s medical transition. Though the dissonance-to-consonance model as presented still needs to be tested by more objective means, the interplay of exposure, openness, and acceptance as contributing factors to parents’ TGD-affirming cost-benefit analyses toward the experience of relief for themselves and their children appears to be consistent with attachment and family counseling best practices (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991; Bowlby, 1988; Gladding, 2019; Minuchin, 1974; Siegel, 2013; Siegel & Bryson, 2011; Wallin, 2007). The combination of these factors, especially as they relate to parents’ fears about the side effects of GCEI and doubts about the genuineness of their child’s gender identity, appeared particularly relevant to this study given the previously cited paucity of research examining the long-term effects of GCEI on developing pre-adolescent and adolescent bodies and that the consistency between gender-expansive identity development and cisgender identity development has only been published recently (Drescher, 2010; Gülgöz et al., 2019). The challenges, however, for adolescents regarding decision-making, impulse control, and executive functioning are well-documented (Siegel, 2013).

Participants in this study praised the work of the professional counselors and other mental health professionals in their life when they (a) provided credible and affirming education about gender identity development; (b) worked in connection with support groups with which participants were involved; (c) recognized that the presenting concerns for the child and/or family may not necessarily be related to gender identity; and (d) completed gatekeeping responsibilities and tasks succinctly, efficiently, and without unexpected financial costs. These factors appear to be consistent with competencies for working with transgender clients developed by SAIGE (Burnes et al., 2010). Participants lamented their experiences with professional counselors and other health care professionals when (a) the above tasks were not completed within these guidelines, (b) the professionals were dismissive of the child’s gender identity or unwilling to provide care, and (c) clinic staff gave participants an unwelcoming or non-affirming impression.

The present study suggests that when presented with the opportunity to serve TGD adults, youth, and their families, professional counselors should familiarize themselves with and develop both the SAIGE competencies and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care (E. Coleman et al., 2012). Furthermore, professional counselors should follow established informed consent guidelines and be upfront and clear about fees for services when it comes to more specialized tasks like writing a GCEI referral letter. A growing body of resources also exists for developing TGD-affirming and inclusive cultures among non-clinical staff employed by counseling practices. For example, the guidelines developed by Morenz and colleagues (2020) for developing and implementing a transgender health program include suggestions for gaining buy-in from and training for reception and administrative staff.

Finally, it appears that collegial support of counselors knowledgeable about the roles of clinicians in working with TGD individuals and families to develop competence among a wider network of providers may be necessary. This support is warranted, given the lack of access to TGD-affirming health care due to residential location, including counseling, cited as an inhibiting factor by this sample. This may support the reduction of referrals of TGD clients between counselors, a practice allowed by the ACA’s (2014) Code of Ethics in matters of limited competency but, as Kaplan (2018) has stated, is also a practice the clients may interpret as rejecting.

Limitations and Future Directions

As with all qualitative research, the results of this grounded theory study, despite the efforts made to maximize trustworthiness, need further testing using quantitative methodology to strengthen their applicability across a broader range of samples (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). By its design, this was a study about how participants resolved their dilemma in an affirming way and therefore may not be as valuable for responding to research questions regarding dilemmas resolved in pathologizing or rejecting ways. This study was also limited demographically, with a sample heavily weighted toward the experiences of White (n = 16), cisgender women (n = 13), and married participants (n = 14). The majority of participants reported household incomes of more than $90,000, doubtlessly improving the odds that they could overcome some inhibiting factors because of greater financial ability. Finally, this research may have been limited by a sample that was heavily weighted toward participants who reside in the Mid-Atlantic region (n = 12); a sample that was more balanced across the United States may have produced different findings.

These findings lend themselves to testing with quantitative methods such as pre-test/post-test program evaluation or randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Both methods have the potential to draw larger, more representative sample sizes, thus enhancing external validity to make greater contributions to the literature. The dissonance-to-consonance model presented here could be used as a program theory for evaluation. RCTs in the vein of what has been used to test the effectiveness of specific counseling modalities, using an approach influenced by the dissonance-to-consonance model compared to a control sample using “therapy as usual” (Ramsauer et al., 2014), may also be valuable for informing best practice while avoiding the ethical dilemma presented by denying treatment. Quantitative investigation may also benefit from further qualitative exploration of the present research questions in a way that addresses the demographic limitations of this study. For example, a grounded theory study of parents who identify as Black may produce different results (Armstrong et al., 2013; Gibbons, 2019; Zheng, 2015).

Conclusion

The present study examined, for the first time, the experiences of parents of TGD youth as they decided to give informed consent for their child to undergo GCEI. They named a variety of inhibitors and contributors to this process, and a “dissonance-to-consonance” model for using contributing factors to overcome inhibitors to the process was illuminated. We found the research process to be emotionally moving and rich with guidance for both parents of TGD youth who are making decisions of considerable consequence for their children and the professional counselors working with them in supportive roles. The model appears to provide fertile ground for further study to support services that affirm and support TGD youth and their families. We relish the opportunity to continue this work and look forward to the contributions of others who advance this topic in service of TGD well-being throughout the life span.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bowlby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. American Psychologist, 46(4), 333–341.

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://bit.ly/ACAcodeofethics

Armstrong, K., Putt, M., Halbert, C. H., Grande, D., Schwartz, J. S., Liao, K., Marcus, N., Demeter, M. B., & Shea, J. A. (2013). Prior experiences of racial discrimination and racial differences in health care system distrust. Medical Care, 51(2), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827310a1

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

Bränström, R., & Pachankis, J. E. (2020). Reduction in mental health treatment utilization among transgender individuals after gender-affirming surgeries: A total population study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(8), 727–734. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010080

Bunim, J. (2015, August 17). First U.S. study of transgender youth funded by NIH: Four sites with dedicated transgender youth clinics to examine long-term treatment effects. UCSF News & Media. https://bit.ly/UCSFstudy

Burnes, T. R., Singh, A. A., Harper, A. J., Harper, B., Maxon-Kann, W., Pickering, D. L., Moundas, S., Scofield, T. R., Roan, A., & Hosea, J. (2010). American Counseling Association competencies for counseling with transgender clients. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 4(3–4), 135–159.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2010.524839

Burt, N. (2016). When girls play with G.I. Joes and boys play with Barbies: The path to gender reassignment in minors. Florida Law Review, 68(6), 1883–1913. https://bit.ly/3GkpSPK

Cashwell, C. S., & Watts, R. E. (2010). The new ASERVIC competencies for addressing spiritual and religious issues in counseling. Counseling and Values, 55(1), 2–5.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.2010.tb00018.x

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Coleman, D. L. (2019). Transgender children, puberty blockers, and the law: Solutions to the problem of dissenting parents. The American Journal of Bioethics, 19(2), 82–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2018.1557297

Coleman, D. L., & Rosoff, P. M. (2013). The legal authority of mature minors to consent to general medical treatment. Pediatrics, 131(4), 786–793. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2470

Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., Monstrey, S., Adler, R. K., Brown, G. R., Devor, A. H., Ehrbar, R., Ettner, R., Eyler, E., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H. . . . Zucker, K. (2012). Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2011.700873

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). SAGE.

Couric, K. (Director, Producer). (2017). Gender revolution [Documentary]. National Geographic.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Dailey, S. F. (2017, June). Ethical & legal considerations: Complicated issues in challenging times. Presentation given at the 2017 Illuminate Symposium, Washington, D.C.

Drescher, J. (2010). Queer diagnoses: Parallels and contrasts in the history of homosexuality, gender variance, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 427–460.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9531-5

Durso, L. E., & Gates, G. J. (2012). Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of services providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless. The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund and The Palette Fund.

Errede, S. (2017). [Lecture notes on acoustical physics of music]. Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne, IL. https://bit.ly/3p8gh7z

Erskine, R. G. (1998). Attunement and involvement: Therapeutic responses to relational needs. International Journal of Psychotherapy, 3(3), 235–244.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Gibbons, J. (2019). The effect of segregated cities on ethnoracial minority healthcare system distrust. City & Community, 18(1), 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12370

Gibbs, J. J., & Goldbach, J. (2015). Religious conflict, sexual identity, and suicidal behaviors among LGBT young adults. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(4), 472–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2015.1004476

Gladding, S. T. (2019). Family therapy: History, theory, and practice (7th ed.). Pearson.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing.

Gonzalez, R. (2018, January 23). How the ‘Religious Freedom Division’ threatens LGBT health—and science. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/how-the-religious-freedom-division-threatens-lgbt-healthand-science

Goodkind, N. (2021, July 9). Ohio law allows doctors to deny health care and birth control to LGBTQ patients. Fortune. https://bit.ly/FortuneLGBTQ

Grossman, A. H., & D’Augelli, A. R. (2007). Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(5), 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527

Gülgöz, S., Glazier, J. J., Enright, E. A., Alonso, D. J., Durwood, L. J., Fast, A. A., Lowe, R., Chonghui, J., Heer, J., Martin, C. L., & Olson, K. R. (2019). Similarity in transgender and cisgender children’s gender development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(49), 24480–24485. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1909367116

Hembree, W. C., Cohen-Kettinis, P. T., Gooren, L., Hannema, S. E., Meyer, W. J., Murad, M. H., Rosenthal, S. M., Safer, J. D., Tangpricha, V., & T’Sjoen, G. G. (2017). Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 102(11), 3869–3903. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-01658

Hill, D. B., & Menvielle, E. (2009). “You have to give them a place where they feel protected and safe and loved”: The views of parents who have gender-variant children and adolescents. Journal of LGBT Youth, 6(2–3), 243–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361650903013527

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

Jorgensen, C. (1967). Christine Jorgensen: A personal autobiography. Bantam.

Kaplan, D. M. (2018, April). Train the trainer: Delivering presentations on the 2014 ACA Code of Ethics. Presentation at the ACA 2018 Conference & Expo Pre-conference Learning Institutes, Atlanta, GA.

Lawson, G. (2016). On being a profession: A historical perspective on counselor licensure and accreditation. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 3(2), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2016.1169955

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families & family therapy (1st ed.). Harvard University Press.

Morenz, A. M., Goldhammer, H., Lambert, C. A., Hopwood, R., & Keuroghlian, A. S. (2020). A blueprint for planning and implementing a transgender health program. Annals of Family Medicine, 18(1), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2473

Murad, M. H., Elamin, M. B., Garcia, M. Z., Mullan, R. J., Murad, A., Erwin, P. J., & Montori, V. M. (2010). Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes. Clinical Endocrinology, 72(2), 214–231.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03625.x

Myers, D. G., & DeWall, C. N. (2019). Exploring psychology in modules (11th ed.). Worth Publishers.

Pew Research Center. (2014). Religious landscape study. http://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study

Ramsauer, B., Lotzin, A., Mühlhan, C., Romer, G., Nolte, T., Fonagy, P., & Powell, B. (2014). A randomized controlled trial comparing Circle of Security Intervention and treatment as usual as interventions to increase attachment security in infants of mentally ill mothers: Study protocol. BMC Psychiatry, 14(24). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-24

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies. American Counseling Association. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf?sfvrsn=20

Rose, J. S., Kocet, M. M., Thompson, I. A., Flores, M., McKinney, R., & Suprina, J. S. (2019). Association for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues in Counseling best practices in addressing conscience clause legislation in counselor education and supervision. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 13(1), 2–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2019.1565800

Rosin, H. (2008, November). A boy’s life. The Atlantic. https://bit.ly/3lIxOCF

Shabad, R. (2021). Biden administration announces reversal of Trump-era limits on protections for transgender people in health care. NBC News. https://nbcnews.to/3drlWAr

Siegel, D. J. (2013). Brainstorm: The power and purpose of the teenage brain. Penguin.

Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2011). The whole-brain child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurture your child’s developing mind. Delacorte Press.

Stryker, S. (2008). Transgender history. Seal Press.

Toporek, R. L., & Daniels, J. (2018). American Counseling Association advocacy competencies: Updated. American Counseling Association https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/aca-advocacy-competencies-updated-may-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=f410212c_4

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018a). HHS announces new Conscience and Religious Freedom Division. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2018/01/18/hhs-ocr-announces-new-conscience-and-religious-freedom-division.html

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018b). Conscience and religious freedom. https://bit.ly/3oz6p7G

Vincent, B. (2019). Breaking down barriers and binaries in trans healthcare: The validation of non-binary people. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1534075

Vines, M. (2014). God and the gay Christian: The biblical case in support of same-sex relationships. Convergent Books.

Wallin, D. J. (2007). Attachment in psychotherapy. Guilford.

Zheng, H. (2015). Losing confidence in medicine in an era of medical expansion? Social Science Research, 52, 701–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.10.009

APPENDIX A

Interview Protocol

Beginning Questions:

- Tell me about how you came to grant informed consent for your child to receive puberty blockers or hormone replacement therapy?

- When did you first notice/realize that your child identified as transgender or gender-diverse (TGD)?

- What was that like?

Intermediate Questions:

- What, if anything, did you know about gender identity and gender expression prior to learning your child identified as TGD?

- What, if anything, did you know about gender-confirming endocrinological interventions (GCEI) prior to giving informed consent for your child to participate in them?

- How, if at all, have your thoughts and feelings changed about gender variance since learning that your child identified as TGD?

- How, if at all, have your thoughts and feelings changed about gender-confirming hormone treatments since your child indicated they wanted to receive them?

- What, if anything, inhibited your change process?

- Who, if anyone, helped you in this change process?

- How, if at all, was a professional counselor or other mental health professional involved?

- What would you say were the most helpful aspects that you experienced during your process toward giving informed consent for GCEI?

Closing Questions:

- Is there something that you might not have thought about before that occurred to you during this interview?

- Is there something else you think I should know to understand your process or experience better?

Charles F. Shepard, PhD, NCC, LPC, is a visiting faculty member at James Madison University. Darius A. Green, PhD, NCC, is the PASS Program Assistant Coordinator at James Madison University. Karli M. Fleitas, MA, is a doctoral student at James Madison University. Debbie C. Sturm, PhD, LPC, is a professor at James Madison University. Correspondence may be addressed to Charles F. Shepard, MSC 7704, James Madison University, 91 E. Grace Street, Harrisonburg, VA 22807, sheparcf@jmu.edu.