Michael D. Hannon, LaShawn M. Adams, Natalie Nieves, Estefanie Ceballo, David Julius Ford, Jr., Linwood G. Vereen

Drawing from the concepts of Critical Race Theory and the Theory of Nigrescence, we report the results of a grounded theory study to explain why a sample of 28 Black counselors chose their profession. Findings suggest that the contributors to this study were motivated to become counselors because of their inspiration to challenge cultural mandates (i.e., grounding motivator), to disrupt Black underrepresentation (i.e., secondary motivator), and to live out their personal and professional convictions (i.e., secondary motivator). Recommendations for counselor education, counseling practice, and counseling research are included.

Keywords: Black counselors, Black underrepresentation, grounded theory, Theory of Nigrescence, Critical Race Theory

Accredited counseling programs enroll White students and hire White faculty at significantly higher rates than they enroll Black students and hire Black faculty (Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2022). Black students and faculty in counseling programs have described their program climates as unsupportive and hostile (Bradley & Holcomb-McCoy, 2004; Brooks & Steen, 2010; Haskins et al., 2013). Given the overwhelming representation of White counselors (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023), this perception has a bearing on Black participation in the professional counseling workforce. To date, the counseling knowledge base offers little on the factors, motivators, and/or reasons that inspire people to become counselors, regardless of their racial and/or ethnic identities. These motivators, factors, and reasons are important, given the value professional counseling places on understanding individuals’ career development and trajectory.

Exploring constructs associated with the choices that Black counselors make about becoming counselors is uniquely important given the historical exclusion of Black counselors from the profession (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2021; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). Simultaneously, Black clients are seeking mental health support in record numbers and actively indicating that they want treatment from Black counselors (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018). The goal of this study was to develop a grounded theory of what motivates Black people to become professional counselors.

Review of the Literature and Theoretical Framework

Developing a theory that explains the reasons why Black people become counselors can benefit the counseling profession in at least three ways. First, it centers the voices, experiences, and insights of Black counselors. Centering them and their experiences is a critical and disruptive act that provides direct and unfiltered insights about factors that have contributed to their engagement and factors that inhibit that engagement, given how their specific experiences and insights are not significantly reflected in counseling research. Second, the results can provide counselors at all levels (e.g., counselor education program faculty and staff, counseling leaders, practicing counselors, and counseling students) an introductory evidence base that can inform more innovative ways to both recruit Black counselors and make counselor preparation programs more inclusive, supportive, and affirming. Third, the findings also provide counselor preparation programs and the agencies and institutions that employ graduates with an introductory evidence base that contributes to increasing the number of Black counselors, which has been documented to encourage more Black and other marginalized people to seek mental health support (Cook et al., 2017; Moreno et al., 2020; Noonan et al., 2016; Primm et al., 2010).

The reasons for the historical exclusion and ongoing underrepresentation of Black counselors are simple. We assert that Black counselors’ exclusion and underrepresentation are a direct consequence of systemic racism. Different forms of systemic racism are evidenced in at least two specific contexts: 1) systemic racism in counseling programs evidenced by limited enrollment of Black counseling students and hiring of Black faculty and 2) systemic racism in counseling journals evidenced by underreported research about career development for Black counselors.

Systemic Racism in Counseling Programs

In its most recent report on counseling program racial demographics, CACREP (2022) noted that approximately 55% of all students in counseling programs were White, while just over 16% were Black. In 2017 CACREP reported approximately 60% of students in counseling programs were White, while less than 20% were Black. So, while there is more representation of other students of color in accredited counseling programs, the number of Black students has decreased. These trends continue in graduate education at institutions across the United States with respect to Black student enrollment. The NCES (2023) reported that Black students comprised 14% of the approximately 3 million students enrolled in U.S. postbaccalaureate programs, as compared to 62% of White students enrolled in 2019. Likewise, the NCES (2021) reported that of the approximately 810,000 full-time faculty at degree-granting institutions in 2018, 75% were White and 6% were Black. The recent Supreme Court ruling striking down race-based affirmative action in college admissions (Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2023), along with assessments found to be culturally biased and inconsistent in predicting students’ success (e.g., Graduate Record Examination; Sullivan et al., 2022) have the potential to be barriers to Black student enrollment. These factors have clear implications for the counseling workforce, evidenced by White counselors comprising anywhere between 70% and 76% of the counseling workforce (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). Unfortunately, Black counseling students and faculty have reported counseling program climates to be isolating, hostile, and tokenizing (Bradley & Holcomb-McCoy, 2004; Brooks & Steen, 2010; Haskins et al., 2013).

Career Development Among Black People in Helping Professions

The research on the impact of race and racial identity on career development among Black people is consistent, indicating Black people consider their race in their career choices (Bell, 2018; Byars-Winston, 2010; Byars-Winston & Fouad, 2006; Chung, 2002; Fouad & Byars-Winston, 2005; Hackett & Byers, 1996; Rollins & Valdez, 2006). Unfortunately, very little research explicitly reports on Black people’s motivation to join helping professions, including counseling. June and Pringle (1977) offered a constructive critique of career theorists (i.e., Roe, Super, and Holland) whose research anchors career development theory in many counselor preparation programs, writing that “None of the three writers incorporated the influence of race in any significant manner in their theories” (June & Pringle, 1977, pp. 22–23). June and Pringle’s insights from more than 35 years ago are telling, given the absence of research that attempts to acknowledge the ways race and racism influence career choices among people who are not White. What follows is a review of the research reporting on influencing factors of Black people who choose to enter helping professions such as social work, family and consumer sciences, and nursing, which can potentially offer insights about why some Black people might choose to become professional counselors. Also included is research about how race influences the career counseling process for Black students and new professionals as they seek to identify viable career options.

Creative Nursing published an article in 2008 (Anonymous, 2008) that provided readers with firsthand accounts of why a group of over 20 nurses chose to enter that profession. They overwhelmingly cited being called to the profession, suggesting that their career choice went beyond typical considerations such as financial stability or convenience. Social work researchers have similarly investigated this topic and have reported that Black social workers most frequently chose the profession because they wanted opportunities to work with people (Gockel, 1966) or had the desire to open a private practice (Butler & Butler, 1990). In their study of 120 social workers, Bowie and Hancock (2000) reported that the social workers chose gaining more social work education in order to advance their careers and learning new social work skills as among the most important reasons to enroll in graduate-level social work courses. Similarly, Burdette-Williamson and O’Neal (1998) reported undergraduates who chose family and consumer sciences as a major were most motivated by influential people, including but not limited to college advisors, parents, and/or college friends. These motivating factors to join helping professions align with Branch’s (2018) dissertation that reported on Black men’s reasons for becoming counselors. Branch cited prior experiences with therapy and Black male counseling mentors as reasons why Black men chose their career path leading to counseling.

Other researchers have centered Black people in the context of career development. The cultural formulation approach with Black clients (Byars-Winston, 2010; Byars-Winston & Fouad, 2006; Fouad & Byars-Winston, 2005) focuses on racial differences in variables related to career choice. Fouad and Byars-Winston (2005) reported differences among racial/ethnic groups in perceptions of career opportunities and barriers to those opportunities; they concluded that the career aspirations of Black and other people of color are similar, but their dreams differ by racial groups. Byars-Winston (2010) recommended the cultural formulation approach in career counseling with Black clients as a descriptive guide to inform counselors’ consideration, documentation, and influence of culture in the counseling relationship by integrating four cultural formulation dimensions (i.e., self and cultural identity, self and cultural conceptions of career problems, self in context, and cultural dynamics in counseling relationships) with the three functions of Black cultural identity (i.e., bonding, buffering, and bridging).

Research about career development among Black students in educational settings (pre-K through higher education) and interventions support using the cultural formulation approach. Rollins and Valdez (2006) sampled 85 Black high school students and found that students who experienced a higher degree of racism reported significantly higher career decision-making self-efficacy (i.e., belief in one’s ability to make a good career decision) but not career task self-efficacy (i.e., belief in one’s ability to successfully complete a career-related task). Rollins and Valdez found that higher ethnic identity achievement, parental socioeconomic status, and being female were related to higher levels of career self-efficacy. Similarly, Duffy and Klingamen (2009) reported in a study of 2,300 racially diverse first-year college students a series of statistically significant, positive correlations between higher levels of ethnic identity achievement and career decidedness. Ethnic identity was found to play little, if any, role in the career development progress of White students. However, for Black and Asian American students, after controlling for race, ethnic identity was found to significantly moderate the relationship between ethnic identity achievement and career decidedness. Duffy and Klingamen (2009) urged counselors to be cognizant of the role ethnic identity plays in students’ career development. The literature reminds us that there are unique considerations for the career development of Black people that explicitly focus on racial identities in general. The research also suggests that there is useful information to be gleaned from how Black people in other helping professions make their career choices, but comparatively little exists about Black counselors.

The literature reviewed here elucidates the challenges Black people confront as counseling clients, counseling students, counseling professionals, and counseling faculty. Researchers continue to document the ways that Black clients experience negative outcomes in counseling, as well as their desires to have counselors who share their racial identity. Barriers exist that exclude Black people from graduate programs, thus creating a shortage of counseling professionals. Similarly, Black faculty are also underrepresented in counseling programs. Still, the importance and value of more Black counselors exist, and the goal of this study was to provide a theoretical grounding to explain Black counselors’ motivation to join the profession.

Integrated Theoretical Framework

Our research team drew on Critical Race Theory (CRT) and the Theory of Nigrescence for an integrated theoretical framework. CRT posits that racism and White supremacy is embedded in everyday structures and systems and impacts the lived experiences of people of color (Garcia & Romero, 2022). Delgado and Stefancic (2001) articulated that race is a socially constructed concept and there is no biological superiority of one racial group over another. Secondarily, several groups are vested in maintaining the current racial hierarchy that esteems Whiteness as superior. Finally, racism is ordinary, common, and an intrusive force in and on Black and other people of color (McGee & Stovall, 2015). For these reasons, CRT provides an appropriate lens for investigation.

Cross et al.’s Theory of Nigrescence (1991) posits that a healthy racial identity is the result of a developmental process during the life span. During this process (i.e., pre-encounter, encounter, immersion/emersion, internalization, and internalization/commitment), Black people transition from not understanding how race affects their experiences to experiencing agency in their own understanding of racial identity of self and others. We believe that race is inextricably tied to Black people deciding to become counselors as they are aware of the deleterious effect of racism on their lives. We further contend that Black people who choose to become professional counselors are further along in their racial identity development, per Nigrescence Theory. These two theories provided us with a fitting and culturally relevant framework with which to administer this study. Our focus on the intersections of race and racism, racial identity development, and career development are congruent with the aims of CRT (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001) and Cross and colleagues’ (1991) Theory of Nigrescence.

Methods

Our goal with this study was to develop an introductory evidence base that identifies what motivates Black counselors to join the counseling profession. There has been a limited amount of research on the intersection of Black peoples’ racial identity and their career motivations. There has also been little research that reports on what motivates Black people to become counselors or how their experiences influence their decision to join the profession. Consequently, we chose a grounded theory design for this study because it is used to help answer complex research questions wherein data are collected and extensively analyzed to create a theory (Mills & Gay, 2019; Singh et al., 2010). To generate a grounded theory, we endeavored to collect data and identify patterns therein to learn what motivated a specific sample of Black people to become counselors (Corbin & Strauss, 1990; Creswell & Poth, 2016) by drawing on the causal conditions, the context(s), and the intervening variables that influence the phenomenon being studied (Vollstedt & Rezat, 2019). Our central research question for the study was: What motivates Black people to become professional counselors?

Researchers’ Positionality Statement

Our research team consisted of six members at varying points in our counseling and counselor education careers. We all share a commitment to resisting and disrupting all forms of oppression. Michael D. Hannon is a Black, male, cisgender counselor educator and counselor whose clinical and research interests are Black men’s mental health and confronting anti-Black racism in professional counseling. LaShawn M. Adams is a Black, cisgender woman whose research focuses on Black women in higher education and feminist ideology. Natalie Nieves and Estefanie Ceballo are Latine cisgender women whose research interests focus on Latine culture from a relational–cultural theory perspective. Adams, Nieves, and Ceballo are doctoral candidates. David Julius Ford, Jr. is a Black, male, queer counselor educator and counselor whose research and clinical interests include Black men in higher education; career counseling; queer and trans Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC); and persons living with HIV/AIDS. Linwood G. Vereen is a Black, male, cisgender counselor educator and counselor whose research and clinical interests include Black people’s mental health, humanistic existentialism, Black existentialism, and humor in counseling. We affirm and celebrate our diverse range of salient and intersectional identities. Our diverse identities also informed the choice of our integrated theoretical framework, given we are all people of color at various points in our racial identity development and who have a shared professional identity.

Contributor Recruitment and Profile

We used two sampling methods, criterion and snowball sampling (Mills & Gay, 2019; Patton, 2014), to recruit potential contributors. Criterion sampling (Patton, 2014) requires that contributors to a study meet a very prominent criteria for eligibility. Mills and Gay (2019) described snowball sampling as the process when researchers invite contributors to recommend additional eligible contributors. All contributors (i.e., participants) were required to meet the following four inclusion criteria: 1) identify as Black (i.e., continental African, Black American, Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Latine, and/or a member of the African Diaspora); 2) be a member of the counseling profession, evidenced by being a counseling student (i.e., enrolled in a counseling master’s, post-master’s, and/or doctoral program), a practicing counselor, and/or being a counselor educator/supervisor; 3) speak and understand American English; and 4) be at least 18 years old. All 28 contributors received $40 gift cards for their participation.

Upon receiving IRB approval, our research team began recruiting by inviting potential contributors with flyers and descriptions via counseling and counselor education email distribution lists and various social media platforms (e.g., X/Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn). Our recruitment efforts yielded over 51 responses from diverse Black counselors, and our final sample included 28 contributors. Twenty-three potential contributors were excluded due to either not fully meeting eligibility criteria and/or interview scheduling conflicts. Each contributor chose their own alias to protect their identity. Basic demographic data about the contributors is listed in Table 1.

Table 1

Contributor Demographics

| Alias | Age | Yrs. of Counseling Exp. | Gender Identity | Ethnicity | Professional Role |

| Ada | 28 | 0–5 years | Cisgender woman | Black American | Doctoral student; practicing counselor |

| Aisha S. | 46 | 15+ years | Female | Afro-Caribbean | Practicing counselor |

| Andrea | 24 | 0–5 years | Female | Afro-Caribbean | Practicing counselor |

| Bianca | 25 | 0–5 years | Female | Mixed race (Black/Hispanic) |

Practicing counselor |

| Capt. Ingenuity | 37 | 0–5 years | Male | Black American | Practicing counselor |

| Carlos | 41 | 11–15 years | Male | Black American | Doctoral student |

| Cheeta | 39 | 0–5 years | Female | Black American | Master’s student |

| Denise | 42 | 15+ years | Female | Black American | Doctoral student; practicing counselor |

| Destiny | 33 | 11–15 years | Female | Black American | Counselor educator/supervisor; practicing counselor |

| Dorothy | 45 | 6–10 years | Female | Mixed race (Black American & White American) | Practicing counselor |

| Erykah | 28 | 0–5 years | Female | Afro-Caribbean | Doctoral student; practicing counselor |

| Franchon | 38 | 11–15 years | Female | Mixed race (Native and African American) | Retired/former counselor |

| Grayson | 45 | 0–5 years | Female | Black American | Practicing counselor |

| Jacques | 68 | 15+ years | Male | Mixed race (Creole Chamorro) | Practicing counselor |

| Jalen | 40 | 15+ years | Male | Black American | Practicing counselor |

| Jena Six | 55 | 0–5 years | Female | Did not reply | Practicing counselor |

| Jesika | 41 | 6–10 years | Female | Afro-Caribbean | Master’s student; school counselor |

| Jo | 63 | 0–5 years | Female | Black American | Practicing counselor |

| Marie J. | 31 | 0–5 years | Female | Black American | Doctoral student |

| Matt | 60 | 15+ years | Male | Black American | Doctoral student |

| Michelle | 26 | 0–5 years | Female | Black American | Master’s student |

| Mildred P. | 51 | 0–5 years | Female | Black American | Master’s student |

| Morris | 22 | 0–5 years | Female | Black American | Master’s student |

| Rene | 29 | 6–10 years | Female | Black American | Practicing resident in counseling |

| Sasha | 41 | 0–5 years | Female | Black American | Doctoral student |

| Serena | 26 | 0–5 years | Female | Black American | Academic advisor |

| Trey | 32 | 6–10 years | Male | Black American | Doctoral student |

| Victor | 33 | 0–5 years | Male | Black American | Practicing counselor |

Data Collection and Analysis

Our sole data collection method was one-time, individual, semi-structured interviews with 28 contributors. We all participated in the data collection process, conducting individual interviews lasting on average 45 minutes each. Each interview was conducted using web conferencing technology (i.e., Zoom), was audio recorded, and was professionally transcribed. We developed an interview protocol to address our overall research question, informed by our review of the literature and specifically inquiring about the reasons contributors chose to become professional counselors. The interview protocol can be found in the Appendix.

Our data analysis process was consistent with general grounded theory analysis methods (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Vollstedt & Rezat, 2019) and those identified by counseling researchers who have conducted and published grounded theory research studies (Hannon & Hannon, 2017; Singh et al., 2010), which included an interactive, three-step process of open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. Our open coding process began after the completion of the fifth interview, wherein members of our team conducted a detailed review of the interviews to find discrete ideas, events, or experiences (i.e., codes) that communicated the reasons why the contributors decided to become professional counselors (Corbin & Strauss, 1990; Singh et al., 2010). Open codes from the first five interviews helped us to develop a codebook as a basis for comparison for the remaining 23 interviews. Our team reached consensus on a list of open codes present in the 28 interviews and then began the axial coding process. Axial coding is a process in which “categories are related to their sub-categories, and the relationships tested against the data” (Corbin & Strauss, 1990, p. 13). In essence, our research team worked together to categorize the open codes, describing them more summatively as we considered the causal conditions, contexts, and intervening variables that explained why these contributors chose to become counselors (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). Finally, we engaged in selective coding of the interview data, which required us to identify a core category that described the central phenomenon (i.e., decision to become counselors) around which all other categories are integrated (Vollstedt & Rezat, 2019).

Trustworthiness

To validate our discoveries, our research team employed a number of trustworthiness strategies. One strategy was member checking (Hannon & Hannon, 2017; Lincoln, 1995) at three different times: 1) during interviews (i.e., asking clarifying questions of contributors during interviews); 2) after interviews (i.e., forwarding transcribed interviews to contributors for additional information and/or corrections); and 3) after our agreement of findings (i.e., providing an executive summary of findings to contributors). No contributors requested content changes. A second trustworthiness strategy we leveraged was investigator triangulation (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000), or when a study includes multiple researchers to assist with accuracy and confirmability of analysis. The investigator triangulation was facilitated through activities such as team meetings to discuss our relationship to the research topic, our individual interpretations of the data, and the subsequent consensus coding that allowed us to intentionally monitor and address the influences of any potential biases. This investigator triangulation provided our team the opportunity to bracket any potential biases we had in our analysis process. A third strategy we used was individual journaling (Giorgi, 1985) to help inform our analysis meetings and determine the ways in which contributors’ accounts affected us emotionally and/or intellectually.

Findings

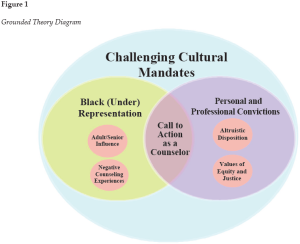

We endeavored to learn, and develop a grounded theory about, why a group of Black people decided to become counselors through this study. What we identified, grounded in the contributors’ responses, was a set of interacting and influencing factors that inspired them to become counselors. These Black counselors were motivated to join the profession based on their inspiration to challenge cultural mandates (i.e., grounding motivator), to disrupt Black underrepresentation (i.e., secondary motivator), and to live out their personal and professional convictions (i.e., secondary motivator). A visual representation of our grounded theory can be found in Figure 1. What follows is a description of our grounded theory.

Figure 1

Grounded Theory Diagram

Challenging Cultural Mandates (Grounding Motivator)

Contributors’ responses indicated they were all motivated to join the profession, in part, to challenge cultural mandates imposed on them by both Black people and people from other racial and/or ethnic groups. These mandates were articulated by implying specific societal and/or career expectations for Black people and communicated ideas and stereotypes like, “Black people don’t do counseling” or professional counseling is not a financially viable career. There was variance in contributors’ answers about this, potentially influenced by their role and years in the profession (e.g., master’s student, practicing counselor, counselor educator/supervisor). The data suggested that the more years in the profession, the more explicit, unapologetic, and clear their rationale was to challenge these cultural mandates. For example, Sasha, a 41-year-old counseling doctoral student, discussed challenging stereotypes about the benefit of counseling for Black people: “In the Black community, they’re like, ‘Oh, I don’t need help, I don’t have mental issues.’ And that was part of my motivation to let them know it’s okay to get counseling.” Ada, a 28-year-old counselor and counseling doctoral student, described her experience receiving mixed messages about working in mental health from people with whom she attended her Black church, saying, “I remember expressing that interest . . . and most people were like, ‘That’s, like really needed, especially in our community.’ But this one older woman was just like, ‘You want to work with people who are like, messed up in the mind?’” Jalen, a 40-year-old counselor, spoke about the strategies he used to make his counseling career financially viable, noting, “In-home counseling led me into . . . people talking about how you can make more money by getting more credentials.”

Black (Under)Representation (Secondary Motivator)

All of the contributors to this study explicitly spoke about being motivated to become counselors for more representation in the profession. We learned from the contributors that this motivator was influenced by two variables: 1) having an adult/senior influence, and 2) having negative personal counseling experiences. Many shared compelling stories of an adult/senior influence (e.g., a family member, a professor) who encouraged them to consider professional counseling as a career option. Additionally, many shared negative experiences as clients. Mildred P., a 51-year-old professional counselor, shared the importance of having a counselor that has a shared racial and/or ethnic identity, noting, “I’ve not seen counselors that look like me. And I feel like . . . if you can relate on the surface, then there’s a level of comfort.” Jo, a 63-year-old counselor who works with college students, addressed the need for more Black counselors who work with college students to increase representation and to amend negative counseling experiences she and Black student clients have had:

There was only one Black counselor there, and she can’t see everybody in the 48,000 population at [redacted university]. She can’t see everyone. And so, they [Black students] didn’t want to go. Or, they’ve gone before and their experiences weren’t the best. And they don’t go back. We know that that happens all the time. It’s even happened to myself. So, when I was thinking about what I can do, because I can complain, you know, and say, ‘Oh, we don’t have counselors, we don’t have counselors,’ or I can do something about it in my little area of the world.

The experience of having an adult/senior influence on these contributors’ motivation to become professional counselors and increase Black representation was salient. Denise, a 42-year-old counselor educator, shared the profound impact of having a Black mentor who was a professional counselor. She shared, “What really was beneficial was seeing . . . a Black man willing to show someone the ropes. . . . I emailed that person, and they responded the same day. That just spoke so much to me of their integrity.” Serena, a 26-year-old Black counselor, recalled the importance of adult/senior influences in her desire to join the profession, noting,

ACA did a mentoring program and . . . I kind of forgotten I’d signed up. And then I got an email saying you’re connected to a mentor and it was great. She had two mentees and she was a counselor of color from [university redacted] and very passionate about empowering people of color, and she was the one, she was the first person to ask me, ‘Why do you want a doctorate?’ In all my—since undergrad—no one asked me that. . . . She was awesome. She introduced me to one of her doctoral students, another Black woman. We met a couple times over Zoom as well.

Finally, Rene and Dorothy provided examples of the ways that negative counseling experiences inspired them to become counselors to increase Black representation in the field. Rene, a 29-year-old female counselor, shared, “In my own journey, I saw how difficult it is to find counselors who had similar identities. And that furthered my already very strong desire to be in the helping profession . . . be a part of that as well.” Dorothy, a 45-year-old counselor, offered a similar sentiment:

I had experiences growing up that led me to therapy personally. And it was really difficult to find a therapist who I could identify with, who I didn’t have to explain in detail about why something was upsetting to me. And I had some experiences that were so difficult that I didn’t return to counseling for several years. And so that was a real driving force in me deciding to enter this profession a little bit later in my life. Because I wanted to be able to offer that to people in similar situations.

Personal and Professional Convictions (Secondary Motivator)

The responses from the contributors in our study indicated that they had personal and professional convictions that motivated them to become professional counselors. Throughout their stories, it was clear to our team that the contributors possessed personal and professional values that inspired them to take action (i.e., become counselors) which allowed them to experience personal and professional congruence. We interpreted the contributors’ personal and professional convictions as a consequence of two factors: 1) they all possessed altruistic dispositions, and 2) they all possessed values of justice and equity.

Evidence of the influence of altruistic dispositions on the contributors’ convictions and ultimate choice to become counselors were present in the following ways. Michelle, a 26-year-old counseling student, simply stated, “You know . . . it’s also just wanting to help people and wanting to show people compassion. And teach them that compassion for themselves. That’s big for me.” Likewise, Morris, a 22-year-old master’s student, shared,

Most of the time, my friends didn’t want to go to the counselors either. So we ended up just being there for each other and just trying to solve each other’s problems or give each other advice. So I just realized maybe I should seek this in a professional way.

Destiny, a 33-year-old counselor educator, supervisor, and clinician, reiterated this point, noting that she had “this compulsion to kind of really help people, to really just talk, and recognizing that . . . my empathy was so innate, and just other effective qualities that you would consider to be associated with a counselor.”

The contributors to this study also clearly valued equity and justice for individuals and communities, which guided their personal and professional convictions and ultimate decisions to become counselors. One example of this is from Aisha S., a 36-year-old counselor educator and supervisor. She described her motivation to be a counselor as being connected to a greater purpose, sharing, “What else stood out for me from those experiences that made me consider professional counseling . . . was being able to . . . think about how I can engage in advocacy efforts at the local level, at the grassroots level.”

Ada, a 28-year-old counselor and counseling doctoral student, shared a similar narrative that centered justice and equity as salient forces among her personal and professional convictions:

I think because I’ve been in that situation where . . . I’ve had to deal with microaggressions or . . . just flat out . . . ignorance, I think that those experiences, along with my own personal therapy, have helped me to pause and think about areas that I am privileged. . . . I don’t have to worry about being deported. I don’t have any disabilities. So, like, I don’t have to constantly think about things like, does this place have an elevator? Or, does this place, like, have a ramp or something like that?

This presentation of a grounded theory explaining why a sample of Black people chose to become professional counselors illustrates the complex and interacting variables that influenced their career choice. It provides our profession insight into how we might continue to attract, retain, and support more diverse people entering the profession and hopefully experiencing career satisfaction.

Discussion

Our study sought to answer a critical question: What motivates Black people to become professional counselors? The findings of the study suggest a confluence of experiences, influences, and variables that led this group of Black people to ultimately join the profession. By leveraging concepts from two theories (i.e., CRT and Theory of Nigrescence), we discovered the salient reasons for 28 Black people to become professional counselors. Three explicit factors lent themselves to the development of a grounded theory that will hopefully engender further study. We offer an account of the ways the findings complement and/or challenge past findings on this issue, and present potentially new insights.

The challenging cultural mandates and Black (under)representation factors specifically address how our research base has informed counselors about Black people’s experiences with counseling and allied mental health professions. The contributors shared the ways systemic, individual, and/or internalized racism has influenced their experiences in and with counseling. Their responses explicitly align with tenets of CRT (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001). The contributors’ various accounts of experiences with racism in several forms (e.g., microaggressions, being tokenized, being excluded) reiterate all the ways in which racism is an intrusive force in the lives of Black and other people of color in the United States (McGee & Stovall, 2015). The counseling profession is at a crossroads with determining training standards and the ways that those training standards will prepare counseling students to meet the needs of diverse clients (CACREP, 2023; Hannon et al., 2023). The sociopolitical climate in the United States continues to be tenuous given anti-Black legislation in states like Florida and North Carolina that is outlawing teaching courses about Black people’s history and diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging for university faculty and staff.

The personal and professional convictions factor offers potentially new insight about how salient the contributors’ values are for deciding to become counselors. The contributors’ decision to become counselors was a result of their altruistic dispositions and their commitment to justice and equity, factors that may assist professional counselors to inspire others to envision counseling as a catalyst for justice for Black people and people from other marginalized groups. These values are congruent with our various codes of ethics (American Counseling Association, 2014; National Board for Certified Counselors, 2023) and the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (Ratts et al., 2016). These specific motivations align closely with what has been reported about why some Black people chose to become nurses, citing a calling (Anonymous, 2008). Further, we tentatively assert the connection of this finding with Cross and colleagues’ (1991) Theory of Nigrescence. We believe that there may be a connection between what stage of racial identity development Black people are functioning from (i.e., pre-encounter, encounter, immersion/emersion, internalization) and their willingness to make choices that reflect their altruistic dispositions and justice values. There are two points of inference worth raising here. First, the contributors to this study explicitly and implicitly made mention of their own racial identity development being closer to the internalization stage when deciding to become a counselor, and we associate that with their inclination to advocate for and pursue justice for themselves and their communities. We wonder if a more mature racial identity development is a predictor of choosing to become a counselor among Black people. Second, the contributors discussed various forms of racism that they experienced in their preparation programs and how, at times, it prompted them to assess where they were in their racial identity development (e.g., operating from an internalization paradigm and moving to an immersion/emersion paradigm depending on the type or form of racism experienced).

The findings also complement prior studies about the career development of Black people in general (Bell, 2018; Byars-Winston, 2010; Byars-Winston & Fouad, 2006), and specifically about counselors (Branch, 2018). It also aligns with the salience of race in career choice and decision-making. The contributors to this study explicitly mentioned that race was an influence (e.g., Black [under]representation) and that their experiences in and with counseling were influenced by their racial identity, illuminating the relevance of CRT (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001; McGee & Stovall, 2015) and Cross et al.’s (1991) Theory of Nigrescence. Branch (2018) indicated that the most salient reason why a sample of Black men became counselors was because of prior positive experiences with Black male counselors (e.g., informal relationships, mentoring relationships, treatment). The study contributors’ negative counseling experiences and their relationships with their adult senior influencer demonstrated how their racial identity significantly impacted their career choices and overall professional development.

Implications

We believe the results from our study can inform the ways that our profession engages with, attracts, supports, retains, and invests in Black counselors. What follows is a presentation of the implications of these findings within two specific contexts: 1) counselor education programs and 2) counseling practice. Counselor education programs must commit to increasing Black representation in their programs by taking explicit steps to challenge admission requirements found to be culturally biased and engage in bolder and more innovative recruitment and retention/support efforts (e.g., agreements with historically Black colleges and universities, predominantly Black colleges and universities, and/or minority-serving institutions) for Black students enrolled in their programs. Counselor education programs can intentionally engage with undergraduate student organizations to further orient potential Black applicants to the counseling profession at large. This research indicates that Black representation is essential in encouraging and promoting mental health services and wellness for Black people. Black representation also encourages Black people to join the profession, a factor that counseling institutions should acknowledge and utilize. An increase in Black representation in counseling programs provides the rationale to engage counseling students in the reflective work that helps them become clearer about their own racial identity development, their own assertions about the influence of race and racism on their own and clients’ lives, and their own career development trajectory. This can be exceptionally helpful in didactic instruction and individual and group supervision.

Finally, the results of our study affirm the need for the counseling profession to continue acknowledging the importance of collaboration between counseling organizations that have different but complementary roles. For example, professional counseling organizations composed of primarily White members should prioritize endorsing and collaborating with professional counseling organizations whose missions and membership are primarily Black (e.g., National Association of Black Counselors, African American Counseling Association, Black Mental Health Symposium). These demonstrations of solidarity, partnership, and membership communicate clear support for such organizations and reiterates the importance of Black counselors identifying pathways for Black clients to culturally affirming and culturally relevant mental health care. Further, the relationships between counselor preparation programs and professional counselors must continue to be mutually beneficial. Practicing counselors are best positioned to inform and advise on community and client needs, given their important role in rendering services. Leveraging the insights of professional counselors to inform counselor education and research is paramount to treating clients in culturally relevant and responsive ways.

Limitations

We acknowledge the privilege that we have in conducting this study and the responsibility of sharing the results for the professional counseling readership. Likewise, we assume responsibility for sharing how the study is limited. One way is in the homogeneity of the sample. We recruited professional counselors who were Black, and the overwhelming majority of them were Black American, female, monolingual counselors. Although our contributors’ voices and experiences are critical for this discourse, a more diverse sample of Black counselors (e.g., Afro-Latine, continental African, Afro-Caribbean, bilingual and/or multilingual Black counselors) could possibly enrich the findings. This translates into another study limitation, which is the limited extent to which findings are transferable, given both the sample size and lack of ethnic diversity (Creswell & Poth, 2016). A third potential limitation is researcher bias. Although we attended to potential bias through trustworthiness strategies such as member checking, investigator triangulation, consensus coding, and research team debriefs, we acknowledge the intimate relationship we all have with this topic and the potential for our biases to influence our interpretations.

Future Research

Counseling researchers should invest more time in learning and sharing about why people choose counseling as a profession, particularly those people who have been historically excluded from the profession for a variety of reasons. Additional studies about why a wider range of people with intersecting and/or other marginalized identities choose to become counselors can enrich our literature and counseling profession at all levels (e.g., students, practicing counselors, counselor educators). For example, Black counselors who are multiracial, are immigrants, and/or speak multiple languages might have very different reasons for joining the profession than Black American counselors. The results from such studies will assist the profession to work from an evidence base to develop programs, interventions, and other forms of support to attract a more racially diverse workforce. Results from these types of studies will allow our profession to develop applicable career development theories that specifically study the lived experiences of Black people and people from other marginalized groups and address their career needs.

Conclusion

This study and its results can continue to assist our profession to exist as the just, inclusive, and affirming profession we aspire for it to be. Actualizing the courage to empirically investigate the reasons Black and other socially, economically, and linguistically diverse people choose to become professional counselors can only benefit our preparation programs, our practicing counselors, and our ever-evolving research base. We maintain hope for the profession’s future to live out our code of ethics (ACA, 2014) in this regard. This is just one step in our effort to sound the clarion call for professional counseling to understand the impact of Black counselors in the field and the importance of institutions (e.g., colleges, universities, professional organizations) having social, cultural, economic, linguistic, and gender diversity among their staff. We trust this contribution moves us to even more action.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest.

This study was funded by an Association for

Counselor Education and Supervision Research

Grant and Montclair State University.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/ethics/2014-aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Anonymous. (2008). Nurses talk about their calling: Experiencing the nursing role. Creative Nursing, 14(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1891/1078-4535.14.1.26

Bell, T. J. (2018). Career counseling with Black men: Applying principles of existential psychotherapy. The Career Development Quarterly, 66(2), 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12130

Bowie, S. L., & Hancock, H. (2000). African Americans and graduate social work education: A study of career choice influences and strategies to reverse enrollment decline. Journal of Social Work Education, 36(3), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2000.10779020

Bradley, C., & Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2004). African American counselor educators: Their experiences, challenges, and recommendations. Counselor Education and Supervision, 43(4), 258–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2004.tb01851.x

Branch, C. J. (2018). The lived experiences of African American males in becoming counselors and counselor educators (Doctoral dissertation, Auburn University).

Brooks, M., & Steen, S. (2010). “Brother where art thou?” African American male instructors’ perceptions of the counselor education profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 38(3), 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2010.tb00122.x

Burdette-Williamson, P., & O’Neal, G. S. (1998). Why African Americans choose a family and consumer sciences major. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 90(2), 60–64. https://www.proquest.com/openview/13aa15e276509e208dd38e0040d1e807/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=41036

Butler, A. S., & Butler, A. C. (1990). A reevaluation of social work students’ career interests. Journal of Social Work Education, 26(1), 45–56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23043209

Byars-Winston, A. M. (2010). The vocational significance of Black identity: Cultural formulation approach to career assessment and career counseling. Journal of Career Development, 37(1), 441–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845309345847

Byars-Winston, A. M., & Fouad, N. A. (2006). Metacognition and multicultural competence: Expanding the culturally appropriate career counseling model. The Career Development Quarterly, 54(3), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2006.tb00151.x

Chung, Y. B. (2002). Career decision-making self-efficacy and career commitment: Gender and ethnic differences among college students. Journal of Career Development, 28(4), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015146122546

Cook, B. L., Trinh, N.-H., Li, Z., Hou, S. S.-Y., & Progovac, A. M. (2017). Trends in racial-ethnic disparities in access to mental health care, 2004–2012. Psychiatric Services, 68(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500453

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2022). Annual report FY 2022.

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2023). 2024 CACREP standards.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

Cross, W. E., Jr., Parham, T. A., & Helms, J. E. (1991). The stages of Black identity development: Nigrescence models. In R. L. Jones (Ed.), Black psychology (3rd ed., pp. 319–338). Cobb & Henry.

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical race theory: An introduction. New York University Press.

Denzin, N. K. (2000). Aesthetics and the practices of qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 6(2), 256–265.

https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040000600208

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.; pp. 1–28). SAGE.

Duffy, R. D., & Klingaman, E. A. (2009). Ethnic identity and career development among first-year college students. Journal of Career Assessment, 17(3), 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072708330504

Fouad, N. A., & Byars-Winston, A. M. (2005). Cultural context of career choice: Meta-analysis of race/ethnicity differences. The Career Development Quarterly, 53(3), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2005.tb00992.x

Giorgi, A. (1985). Phenomenology and psychological research. Duquesne University Press.

Gockel, G. L. (1966). Social work as a career choice. In E. E. Schwartz (Ed.), Manpower in social welfare: Research perspectives (pp. 89–98). National Association of Social Workers.

Hackett, G., & Byars, A. M. (1996). Social cognitive theory and the career development of African American women. The Career Development Quarterly, 44(4), 322–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00449.x

Hannon, M. D., & Hannon, L. V. (2017). Fathers’ orientation to their children’s autism diagnosis: A grounded theory study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 2265–2274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3149-6d

Hannon, M. D., White, E. E., & Fleming, H. (2023). Ambivalence to action: Addressing systemic racism in counselor education. Counselor Education and Supervision, 62(2), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12264

Haskins, N., Whitfield-Williams, M., Shillingford, M. A., Singh, A., Moxley, R., & Ofauni, C. (2013). The experiences of Black master’s counseling students: A phenomenological inquiry. Counselor Education and Supervision, 52(3), 162–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2013.00035.x

June, L. N., & Pringle, G. D. (1977). The concept of race in the career-development theories of Roe, Super, and Holland. Journal of Non-White Concerns in Personnel & Guidance, 6(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-4950.1977.tb00070.x

Lincoln, Y. S. (1995). Emerging criteria for quality in qualitative and interpretive research. Qualitative Inquiry, 1(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049500100301

McGee, E. O., & Stovall, D. (2015). Reimagining critical race theory in education: Mental health, healing, and the pathway to liberatory praxis. Educational Theory, 65(5), 491–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12129

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Mills, G. E., & Gay, L. R. (2016). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and applications. Pearson.

Moreno, C., Wykes, T., Galderisi, S., Nordentoft, M., Crossley, N., Jones, N., Cannon, M., Correll, C. U., Byrne, L., Carr, S., Chen, E. Y. H., Gorwood, P., Johnson, S., Kärkkäinen, H., Krystal, J. H., Lee, J., Lieberman, J., López-Jaramillo, C., Männikkö, M., . . . Arango, C. (2020). How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(9), 813–824.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2

National Board for Certified Counselors. (2023). NBCC code of ethics. https://nbcc.org/Assets/Ethics/NBCCCodeofEthics.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). Digest of education statistics 2021. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/index.asp

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). Postbaccalaureate enrollment. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/chb

Noonan, A. S., Velasco-Mondragon, H. E., & Wagner, F. A. (2016). Improving the health of African Americans in the USA: An overdue opportunity for social justice. Public Health Reviews, 37, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-016-0025-4

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE.

Primm, A. B., Vasquez, M. J., Mays, R. A., Sammons-Posey, D., McKnight-Eily, L. R., Presley-Cantrell, L. R., McGuire, L. C., Chapman, D. P., & Perry, G. S. (2010). The role of public health in addressing racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental illness. Preventing Chronic Disease, 7(1). https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jan/09_0125.htm

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Rollins, V. B., & Valdez, J. N. (2006). Perceived racism and career self-efficacy in African American adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology, 32(2), 176–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798406287109

Singh, A. A., Urbano, A., Haston, M., & McMahon, E. (2010). School counselors’ strategies for social justice change: A grounded theory of what works in the real world. Professional School Counseling, 13(3), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.5330/PSC.n.2010-13.135

Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College. 600 U. S. (2023). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: African Americans. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt23247/2_AfricanAmerican_2020_01_14_508.pdf

Sullivan, L. M., Velez, A. A., Longe, N., Larese, A. M., & Galea, S. (2022). Removing the Graduate Record Examination as an admissions requirement does not impact student success. Public Health Reviews, 43, https://doi.org/10.3389/phrs.2022.1605023.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023). Labor force statistics from the Current Population Survey. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

Vollstedt, M., & Rezat, S. (2019). An introduction to grounded theory with a special focus on axial coding and the coding paradigm. In G. Kaiser & N. Presmeg (Eds.), Compendium for early career researchers in mathematics education (pp. 81–100). Springer.

Appendix

Interview Protocol

Individual Interview Questions/Script

Thank you for agreeing to participate in this important study. If you remember, this study is designed to begin providing an empirical base for what factors motivate Black people to become professional counselors. Please note these interviews will be audio recorded. Do you have any questions before we begin? Please take your time in answering the following questions and please be reminded that you can skip any question and withdraw at any time.

All participants should be asked these questions:

Would you share with me what motivated you to become a counselor?

What about those experiences convinced you that professional counseling was a good fit for your career?

What did/do you find most helpful in your counselor training?

What did/do you find most challenging in your counselor training?

Are/were you one of few Black students in your counselor training program?

If so, what is/was that experience like for you?

If not, what is/was that experience like for you?

Do you believe you experienced/are experiencing anti-Black racism in your counselor training program?

If so, in what ways is this happening/did this happen?

If participant is/was a practicing counselor, please ask:

What is most rewarding for you as a Black practicing counselor?

What role, if any, do Black counselors have in helping increase Black representation in counseling?

Do you believe anti-Black racism exists in professional counseling? If so, in what ways?

Are you one of few Black counselors where you practice?

If so, what is that experience like for you?

If not, what is that experience like for you?

If participant is a counselor educator, please ask:

How long have you been a counselor educator?

What motivated you to become a counselor educator?

What role, if any, do Black counselor educators have in helping increase Black representation in counseling?

Do you believe anti-Black racism exists in counselor education? If so, in what ways?

Are you one of few Black counselor educators where you teach?

If so, what is that experience like for you?

If not, what is that experience like for you?

Please conclude all individual interviews with this question and information:

Is there anything else you’d like to share about your motivations to become a professional counselor that we haven’t discussed to this point?

Thank you for participating in this interview. Your insights are valuable. What you can expect now is for our research team to transcribe this interview, de-identify it, and send it to you for your review to confirm its accuracy. Our team will then begin our analysis and send you updates on our interpretations of what participants have shared. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to be in touch with Dr. Hannon at hannonmi@montclair.edu.

Michael D. Hannon, PhD, NCC, BC-TMH, LAC (NJ), is an associate professor at Montclair State University. LaShawn M. Adams, MA, NCC, LPC (NJ), is a doctoral candidate at Montclair State University. Natalie Nieves, MA, NCC, LPC (NJ), is an instructor at Molloy University. Estefanie Ceballo, MSED, NCC, CCMHC, ACS, LMHC (NY), LPC (NJ), C-TFCBT, CCTP, is a doctoral candidate at Montclair State University. David Julius Ford, Jr., PhD, NCC, ACS, LCMHC (NC), LPC (NJ, VA), is an associate professor at Monmouth University. Linwood G. Vereen, PhD, LPC, is a clinical associate professor at Oregon State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Michael D. Hannon, 2114 University Hall, Department of Counseling, College for Community Health, Montclair State University, 1 Normal Avenue, Montclair, NJ 07043, hannonmi@montclair.edu.