Feb 9, 2015 | Article, Volume 5 - Issue 1

Mark J. Schwarze, Edwin R. Gerler, Jr.

The purpose of this exploratory study was to investigate the effectiveness of a modified mindfulness-based cognitive therapy intervention using individual counseling sessions to reduce stress and increase levels of mindfulness among nursing students. An AB single-subject experimental design replicated three times was implemented. Results indicated reduced stress in two out of three participants and increased mindfulness levels in all participants. Implications for college counselors and counselors working with clients in high-stress occupations are provided. Additionally, the results show promise for the use of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in individual counseling.

Keywords: mindfulness, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, stress, college counselors, nursing, single-subject experimental design

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) has been described as part of a third generation of cognitive therapies (Harrington & Pickles, 2009). Along with dialectical behavioral therapy and others like it, MBCT has integrated the construct of mindfulness with standard cognitive-behavioral paradigms. MBCT found its origins in the work of Kabat-Zinn’s (1990) mindfulness-based stress reduction program. This 8-week group-based program consisted of Buddhist mindfulness mediation practices to help chronic pain sufferers reduce their stress associated with illness. MBCT has incorporated elements of mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive-behavioral therapy to help individuals become more aware of thoughts and feelings and put them into context as mental events rather than self-defining constructs (Teasdale et al., 2000).

Seeing a need for an intervention to help patients who had repeatedly relapsed into depression, Segal, Williams, and Teasdale (2002) formalized MBCT as a standardized program of therapy. Designed as an 8-week program with specific guidelines for each session, MBCT was originally conceived as a group modality. Clients are placed in classes to learn the mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) skills needed to regulate emotions and thoughts. MBCT involves training the mind to avoid judgmental reactions to events, thoughts, feelings and body sensations and to practice nonjudgmental awareness and acceptance (Ma & Teasdale, 2004). The key component of MBCT is mindfulness.

Mindfulness, once an abstract concept in the counseling field, is reaching mainstream awareness and gaining more attention in the literature (Brown, Marquis, & Guiffrida, 2013). Derived from Zen Buddhism, mindfulness has been described as a commitment to bringing awareness back to the present moment (Harrington & Pickles, 2009). Brown and Ryan (2003) defined mindfulness as “the state of being attentive to and aware of what is taking place in the present” (p. 822). Despite a growing research base, mindfulness as a testable and operationally defined variable is still being shaped.

Bishop et al. (2004) proposed an operational definition of mindfulness as a two-component skill-building approach for responding to emotional and cognitive distress. The first component involves the self-regulation of attention. Measurable skills must be obtained to reach a successful level of self-regulation of attention, including sustained attention; switching, or bringing the attention back to a focal point; and inhibition of elaborative processing, which involves the ability to maintain a state of flexible and nonjudgmental focus and awareness over a period of time. The second component includes developing an orientation to experience. In this, all thoughts, feelings and sensations are acknowledged.

Mindfulness training works well in counseling in that it is a simple idea: staying focused on momentary experience (Grabovac, Lau, & Willett, 2011). The core strategy to teach clients is mindfulness meditation. Meditation has many forms but is ultimately the practiced skill of quieting the mind (Wright, 2007). Counselors trained in meditation can teach clients to sit quietly and observe thoughts and feelings without reaction or judgment (Brown et al., 2013). A version of this meditation is the 3-minute breathing space (Segal et al., 2002). This meditation approach is a core skill learned in MBCT. It utilizes the breathing techniques of meditation while attempting to bring awareness to present experience, focusing on breath as a mediator and expanding to other bodily sensations.

Because mindfulness is rooted in Buddhist philosophy and belief, its inclusion in Western counseling paradigms has been slow. Most interventions and models consisting of mindfulness-based ideas have been stripped of the Eastern religious and philosophical foundations and presented as skill-based acquisitions (Baer, 2003). This change has increased acceptance of mindfulness-based approaches in mainstream treatment and educational venues. Specifically, using mindfulness to mitigate stress has been a benefit of this practice. One particular population that has historically reported high levels of stress is nursing students (Beddoe & Murphy, 2004).

Nursing Students and Stress

The Spring 2013 American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment (American College Health Association, 2013) listed stress as the number-one impediment to academic success for college students. Specifically, college students training to be nurses at the university level are subjected to high levels of stress (Gibbons, Dempster, & Moutray, 2011). Pulido-Martos, Augusto-Landa, and Lopez-Zafra’s (2012) review of the literature on the nursing student experience found several factors leading to stress, including balancing home and academic demands, experiencing time management pressures and financial problems, lacking meaningful connections with the nursing faculty, and feeling unprepared and incompetent in clinical practice.

In addition, stress, combined with other issues, has led to significant attrition rates in nursing programs (Harris, Rosenberg, & O’Rourke, 2014). Stickney (2008) found that the number of new students in nursing programs is too low to ensure an adequate number of nurses to meet the future needs of health care agencies. Students in nursing programs experience significant amounts of stress from trying to balance their lives at home with academic responsibilities. It is imperative that counselors, especially those in college settings, are aware of effective and innovative interventions to help nursing students, as well as other students, reduce stress and be successful. MBCT has shown promise in helping people reduce negative emotions such as stress (Collard, Avny, & Boniwell, 2008; Teasdale et al., 2000).

This study utilized a modified version of MBCT in individual counseling sessions to teach and process MBCT core skills of mindfulness meditation and cognitive decentering. While MBCT has mostly been utilized in group formats, there is some argument that group counseling is not always the best approach. Kuyken et al. (2008) found that 5% of an eligible sample for their MBCT study declined participation because they did not like the group aspect of the intervention. Lau and Yu (2009) suggested that offering mindfulness-based treatments in an individual format might increase participation for those who are reluctant to be involved in group settings.

The purpose of this exploratory single-subject experimental study was to evaluate the effectiveness of using MBCT to help reduce stress among university nursing students. Nursing students were used because of their documented high levels of stress. The questions explored included whether using MBCT in individual sessions increases self-reported levels of mindfulness and decreases self-reported levels of stress.

Method

Research Design

Single-subject design has a long history in psychological and counseling research (Heppner, Wampold, & Kivlighan, 2008). Barlow and Hersen’s (1984) exposition on the chronology of single-subject design reveals that psychology’s early research development was steeped in the use of this type of experiment. Lundervold and Belwood (2000) called single-subject experimental design “the best kept secret in counseling” (p. 92). This design can provide counselors with scientific methods of research that produce practical and useful clinical information that can be applied to practice settings.

There are several advantages of using a single-subject experimental design. It allows the researcher to narrow causes of behavior change and determine which treatment approaches are most effective. Group designs often can obscure change in individuals, thereby not allowing flexibility in modifying treatment protocols to isolate examples of cause and effect (Barlow & Hersen, 1984). Morgan and Morgan (2003) posited single-subject design as the best option when trying to explain individual differences. Another advantage of single-subject experimental design is that because the researcher collects data using a baseline and intervention phase, the subject acts as his or her own control group, thereby increasing internal validity (Sharpley, 2007). Additionally, single-subject design can allow for scrutiny of new and innovative approaches (Chapman, Baker, Nassar-McMillan, & Gerler, 2011). Specifically, this study utilized a basic single-subject experimental AB design that allows for a maximum clinical utility.

Participants

Participants in this study were all senior-level students enrolled in a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) program at a small rural Southeastern university. Four of the participants were female and one was male. Participant ages ranged from 21–30 years old (mean age 25.6 years). Three of the participants were Caucasian, one was Hispanic American and one was Native American.

The sample was recruited from students enrolled in the upper division pre-licensure BSN program and fully engaged in all activities and requirements of the program, including clinical work at local hospitals in order to develop basic and advanced nursing skills. Recruitment involved presenting the study and requirements for participation to a class for senior nursing students and sending an e-mail to all junior and senior students, yielding five volunteers. Two of the participants dropped out of the study after intervention sessions two and three, respectively. (More discussion and analysis about participant attrition is presented in the results section.)

Measures

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was developed by Cohen, Kamarck, and Mermelstein (1983) to measure the degree to which one evaluates situations and events in his or her life as stressful. Specifically, the 10-item version of the PSS (PSS-10; Cohen & Williamson, 1988) measures the degree to which one perceives life as uncontrollable, unpredictable and overloading. The PSS-10 typically requires participants to answer questions based on their experiences in the past 30 days. A modification for this study was asking participants to answer the questions based on their experiences and thoughts in the past 7 days, as the study was focused on weekly variability. The PSS-10 has a Likert-type rating scale and is widely used as a measure of perceived stress. It is shown to have internal reliability (coefficient alpha of .78) with established construct validity, as the PSS-10 scores have shown moderate relation to other measures of appraised stress. Scores can range from 0–40, with higher scores indicating greater stress. Roberti, Harrington, and Storch (2006) found the PSS-10 reliable and valid with a non-clinical sample of college students. Mean scores for males were 17.4 (SD = 6.1); mean female scores were 18.4 (SD = 6.5).

Also used in the study was the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), a 15-item scale designed to measure characteristics of openness or receptiveness to what is taking place in the present (Brown & Ryan, 2003). The MAAS aims to assess the level at which one is able to observe what is happening without judgment. The MAAS assesses the absence or presence of mindful mental states over time. For this study, participants were asked to form their answers based on experiences and thoughts over the past 7 days. Normative information is available for college populations (14 independent samples: N = 2,277; M = 3.83, SD = .70). Cronbach’s alphas range from .80–.90. The MAAS also has shown high test-retest reliability, discriminant and convergent validity, and criterion validity (Brown & Ryan, 2003). MacKillop and Anderson (2007) confirmed validity and reliability of the MAAS with internal reliability scores of .89.

Procedure

Participants volunteering for the study were scheduled individually for an appointment to meet with the researcher to complete a study orientation and start baseline measurements. This 30-minute meeting consisted of an introduction to the study and the researcher, obtaining a brief background of the participant, a definition of mindfulness, completion of the informed consent paperwork, and completion of a short participant demographic form. Additionally, the first baseline measurements with the PSS-10 and MAAS were collected at the end of this meeting, and the final three baseline measurements were scheduled. Each baseline meeting consisted of an informal discussion about academic and personal stress levels and completion of the dependent measures. In total, four baseline measurements were collected over 5 weeks.

The intervention phase (B) consisted of six 1-hour sessions conducted over 5.5 weeks starting at the conclusion of the baseline phase (A). Session one began on the first week of classes in a spring semester, and sessions two through five occurred during each subsequent week. The final session, a wrap-up and review, was scheduled for the beginning of week six of the intervention. Each session consisted of 50 minutes focusing on MBCT skills, concepts and homework assignments, and 10 minutes at the end of the session to administer the dependent measures. At the final session, the researcher explained procedures and options for counseling if the participant desired to continue exploring MBCT or other issues that may have come up during the study period. Additionally, all participants received mindfulness resources such as book and Web site lists in order to continue learning and practicing mindfulness exercises.

MBCT Intervention

MBCT is traditionally an 8-week intervention conducted in group or class settings (Teasdale et al., 2000). Because this study utilized individual counseling, the intervention was reduced to six sessions, and session length was reduced to 1 hour. The individual counseling modality allowed for more focused attention to participants, and exercises could be consolidated. Also, MBCT was originally used to treat clients with chronic relapsing depressive disorders, while stress was the target symptom in this study. Due to this shift in focus, some of the exercises and homework assignments relevant to those who might have depression were not included in the intervention. Another modification included the use of prerecorded guided meditations for body scans and breathing instead of researcher-led meditations. During sections of the intervention when a meditation was introduced and practiced, the researcher started a prerecorded meditation and left the room while the participant experienced the meditation. The prerecorded breathing and body scan meditations used for this study were from the Maddux and Maddux podcast (2006).

The modified intervention still utilized the core MBCT exercises and philosophy. The next section includes a description of the major techniques used and what modifications were made to accommodate the study goals. Also included is an outline of the six session themes. Theme 1: Using Mindfulness to Break Out of Automatic Pilot focuses on an orientation to mindfulness and techniques to develop a heightened awareness of the present moment. Theme 2: Focus on the Body Enhances Clarity of the Mind, and Theme 3: Mindfulness of the Breath introduce the exercises of the body scan and breathing mediation. Theme 4: Acceptance promotes nonjudgmental acceptance of events, cognitions and emotions. Theme 5: Thoughts Are Not Facts is an educational session about cognitive-behavioral philosophies and their impact on moderating emotions. Theme 6: Putting It All Together provides a summary of the ideas and techniques of MBCT, with suggestions on how to integrate the concepts daily. The modified structure and content used is unique to this study; however, the specific components, homework and exercises are taken from Segal et al. (2002). Table 1 describes the schedule and order of session content, including session themes and agendas.

MBCT Techniques and Exercises Used in the Study

Raisin exercise. Used as an introduction to mindfulness, this exercise asks participants to take a raisin offered by the researcher and examine all aspects of its shape, texture and external characteristics. Open-ended questions are asked to help participants explore their experience.

Body scan meditation. The exercise brings a detailed awareness and focus to specific areas of the body. A modification in this study included using a shorter meditation (8 minutes; Maddux & Maddux, 2006).

Be mindful during a routine activity. Participants are asked to choose a routine activity (e.g., brushing teeth, vacuuming, washing dishes) and to complete it mindfully per the study’s training.

Homework record forms. Used in all sessions, these forms allow participants to document the frequency of practice of mindfulness activities.

Thoughts and feelings exercise (professor sends an e-mail). In this exercise, the researcher presents a scenario to elicit participant reaction.

Pleasant and unpleasant events calendars. Participants receive forms (Segal et al., 2002) that help them identify one pleasant event per day in week two and one unpleasant event per day in week three.

Five-minute hearing exercise. Participants are asked to sit for 5 minutes with eyes closed and center all of their focus on hearing. When intrusive thoughts enter, participants are instructed to acknowledge them, but then return their focus to only hearing.

Three-minute breathing space. A core skill in MBCT, this exercise acts as a mindfulness timeout.

Twenty-minute sitting meditation. This meditation is a combination of all the skills participants have learned, including the body scan, breathing meditations and the hearing exercise.

Moods, thoughts and alternative viewpoints discussion. This exercise involves a short overview of how thoughts can influence mood, and techniques and suggestions for viewing intrusive thoughts in a different way. Handouts titled Ways You Can See Your Thoughts Differently and When You Become Aware of Negative Thoughts are provided (see Segal et al., 2002).

Breathing meditation. This exercise brings a detailed awareness and focus to the breath. A modification in this study included using a shorter (9 minutes) recorded breathing meditation (Maddux & Maddux, 2006).

Mindfulness resources handout. Researchers generate a list of books, Web sites and podcasts that describe mindfulness and the techniques associated with the study. The participants receive this at the last session with encouragement to continue to seeking information on mindfulness practice if they have found it helpful.

Table 1

Schedule and Order of Session Content

|

Session Number

|

Theme

|

Agenda

|

| 1 |

Using mindfulness to break out of automatic pilot |

Orientation to mindfulness and MBCT, raisin exercise, body scan introduction and practice, assign homework: use body scan tape six times before next session, be mindful during a routine activity. Provide handouts: Definition of Mindfulness, Summary of Session 1, homework record forms (Segal et al., 2002). Administer PSS-10 and MAAS. |

| 2 |

Focus on the body enhances clarity of the mind |

Body scan practice and review, homework review, thoughts and feelings exercise (professor sends an e-mail), introduction of pleasant events calendar assignment, 10-minute breathing meditation introduction and practice. Assign homework: use body scan tape six times before next session, use breathing meditation tape six times before next session, complete pleasant events calendar once a day. Provide handouts: Tips for Body Scan, Summary of Session 2, homework record forms, Mindfulness of the Breath, The Breath, Pleasant Events Calendar (Segal et al., 2002). Administer PSS-10 and MAAS. |

| 3 |

Mindfulness of the breath |

Five-minute hearing exercise, 10-minute breathing meditation practice and review, homework review, introduction of unpleasant events calendar assignment, 3-minute breathing space explanation. Assign homework: use breathing meditation tape six times before next session, unpleasant calendar (daily) completed once a day, 3-minute breathing space three times a day. Provide handouts: 3-Minute Breathing Space Instructions, Summary of Session 3, homework record forms, Mindfulness of the Breath, Unpleasant Events Calendar (Segal et al., 2002). Administer PSS-10 and MAAS. |

| 4 |

Acceptance |

Five-minute hearing exercise, 10-minute breathing meditation practice and review, body scan meditation practice and review, homework review, 20-minute sitting meditation introduction and practice. Assign homework: 20-minute sitting meditation six times before next session, 3-minute breathing space three times a day and as needed. Provide handouts: Sitting Meditation Extended Instructions (Segal et al., 2002), Summary of Session 4, homework record forms. Administer PSS-10 and MAAS. |

| 5 |

Thoughts are not facts |

20-minute sitting meditation practice and review; homework review; moods, thoughts and alternative viewpoints discussion; 3-minute breathing space. Assign homework: 30-minute breathing meditation (three times a week), 3-minute breathing space (three times a day). Provide handouts: Ways You Can See Your Thoughts Differently, When You Become Aware of Negative Thoughts (Segal et al., 2002), Summary of Session 5, homework record forms. Administer PSS-10 and MAAS. |

| 6 |

Putting it all together |

Body scan practice and review, breathing meditation practice and review, sitting meditation practice and review (10 minutes), homework review, review of all techniques used in study. Provide handouts: Daily Mindfulness (Segal et al., 2002), mindfulness resources (researcher generated), Summary of Session 6, Daily Mindfulness, Mindfulness Resources. Administer PSS-10 and MAAS. |

Results

All five participants completed the baseline phase (A) of four weekly meetings to complete the dependent measures. A1–A4 represent weeks one through four of the baseline phase. Out of five participants, three participants completed the full intervention phase (B) of six weekly 1-hour sessions. B1–B6 represent weeks one through six of the intervention phase. The phases ran consecutively. One participant completed only two of the intervention sessions before withdrawing from the study. This participant cited a variety of issues including unexpected sickness and time constraints as deciding factors for withdrawal. Another participant completed three intervention sessions before withdrawing, citing time constraints and academic demands as reasons for withdrawal. The researchers have included the results for only the three participants who completed the full intervention, due to the importance in single-subject designs of multiple measurements of the dependent variable occurring over the complete span of the study in order to determine changes in self-reports of mindfulness and perceived stress. It is the comparison of the two full phases that allows interpretation of whether the intervention was the cause of the change.

Participant 1

Participant 1 reported no previous experience with mindfulness activities. The baseline mean score on the PSS-10 for Participant 1 was 21.75. This baseline mean score is higher than that of the normative sample and indicates some experience of perceived stress. The baseline mean score on the MAAS was 3.07. This baseline mean score is lower than that of the normative sample and indicates less self-report of mindfulness as measured by the MAAS. The individual scores over the baseline period for the PSS-10 fluctuated, which may be related to the time of administration. The A1 and A4 scores were both 22, and both measurements were taken at high-stress academic times. However, Participant 1 earned the highest score in the baseline phase (25) at A3, on Christmas Eve. These scores support the literature that found several factors leading to nursing student stress, including home and academic demands (Magnussen & Amundson, 2003). Alternately, the individual scores over the baseline period for the MAAS were mostly stable with a significant drop in A4, which was collected on the last Friday before the spring semester started. With the focus that mindfulness places on staying in the present moment, as measured by the MAAS, the anticipation of the new semester may have taken precedence. Essentially, baseline scores on the PSS-10 were variable, as were the academic and home stressors, and MAAS scores were relatively stable, but below normative scores for college populations.

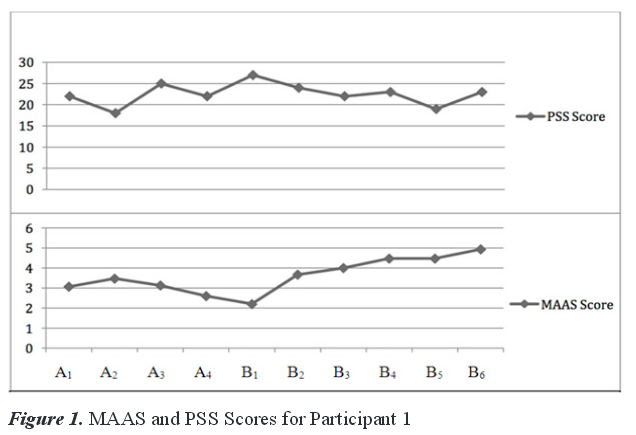

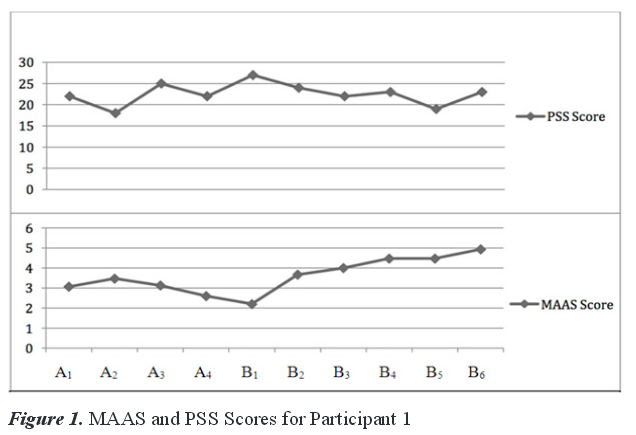

The intervention mean score on the PSS-10 was 23. This score was 1.25 points higher than the baseline mean of overall self-reported stress as measured by the PSS-10. The individual scores of the intervention phase showed decreasing PSS-10 scores from B1–B3 while showing increasing MAAS scores at the same time for Participant 1 (see Figure 1). B4 showed a 1-point increase from B3 in PSS-10 scores, which coincided with Participant 1 experiencing a medical emergency. Despite this crisis, stress scores increased only minimally while mindfulness scores increased by .47 from B3–B4.

MAAS scores continued to increase throughout the intervention phase, with the highest score of 4.93 reported at the final session. This finding indicated that increased exposure to and practice of mindfulness activities correlated with higher self-report of mindfulness scores. This result was confirmed by an increase of 0.88 in the mean scores on the MAAS from baseline to intervention and a gain of 2.73 from B1–B6 (see Figure 1). Table 2 provides the dependent measure scores for Participant 1.

Participant 2

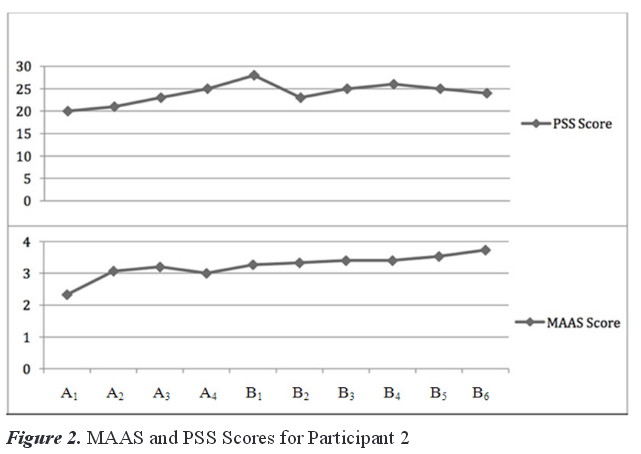

Participant 2 reported no previous experience with mindfulness activities. The baseline mean score on the PSS-10 for Participant 2 was 22.25. This baseline mean score is higher than that of the normative sample and indicates some experience of perceived stress as measured by the PSS-10. The baseline mean score on the

Table 2

Dependent Measure Scores for Participant 1

|

|

PSS-10

|

|

MAAS

|

| Session |

|

Score

|

M

|

SD

|

|

Score |

M

|

SD

|

| A1 |

|

22

|

|

|

|

3.07 |

|

|

| A2 |

|

18

|

|

|

|

3.47 |

|

|

| A3 |

|

25

|

|

|

|

3.13 |

|

|

| A4 |

|

22

|

21.75

|

2.87

|

|

2.6 |

3.07

|

0.36

|

| B1 |

|

27

|

|

|

|

2.2 |

|

|

| B2 |

|

24

|

|

|

|

3.67 |

|

|

| B3 |

|

22

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

| B4 |

|

23

|

|

|

|

4.47 |

|

|

| B5 |

|

19

|

|

|

|

4.47 |

|

|

| B6 |

|

23

|

23

|

2.61

|

|

4.93 |

3.96

|

0.96

|

Note. Sessions A1–A4 were baseline sessions; sessions B1–B6 were intervention sessions.

MAAS was 2.9. This baseline mean score is lower than that of the normative sample and indicates less self-report of mindfulness as measured by the MAAS. The individual scores over the baseline period for the PSS-10

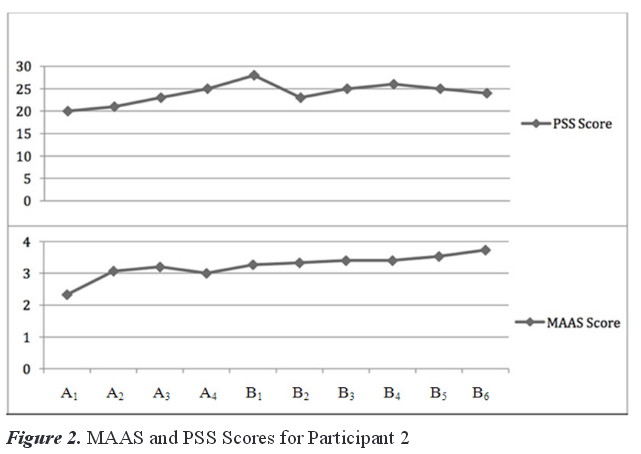

showed an increase in stress scores, with the highest baseline score (25) coming at A4. The individual scores over the baseline period for the MAAS were stable with the lowest score (2.33) reported at A1. Baseline scores on the PSS-10 increased and MAAS scores were stable once past the initial baseline meeting, but still remained below the normative scores (see Figure 2).

The intervention mean score on the PSS-10 was 25.17. This score represents a 2.92-point gain from the baseline mean in overall self-reported stress as measured by the PSS-10. However, there was a drop of five points on the PSS-10 from B1–B2. MAAS scores continued to increase throughout the intervention phase with highest score of 3.73 coming at the final session. There was an increase of 0.54 in the mean scores on the MAAS from baseline to intervention and a gain of 0.46 from B1–B6. Table 3 lists the dependent measure scores for Participant 2.

Table 3

Dependent Measure Scores for Participant 2

|

|

PSS-10

|

|

MAAS

|

| Session |

|

Score

|

M

|

SD

|

|

Score |

M

|

SD

|

| A1 |

|

20

|

|

|

|

2.33 |

|

|

| A2 |

|

21

|

|

|

|

3.07 |

|

|

| A3 |

|

23

|

|

|

|

3.2 |

|

|

| A4 |

|

25

|

22.25

|

2.22

|

|

3 |

2.9

|

0.39

|

| B1 |

|

28

|

|

|

|

3.27 |

|

|

| B2 |

|

23

|

|

|

|

3.33 |

|

|

| B3 |

|

25

|

|

|

|

3.4 |

|

|

| B4 |

|

26

|

|

|

|

3.4 |

|

|

| B5 |

|

25

|

|

|

|

3.53 |

|

|

| B6 |

|

24

|

25.17

|

1.72

|

|

3.73 |

3.44

|

0.17

|

Note. Sessions A1–A4 were baseline sessions; sessions B1–B6 were intervention sessions.

Participant 3

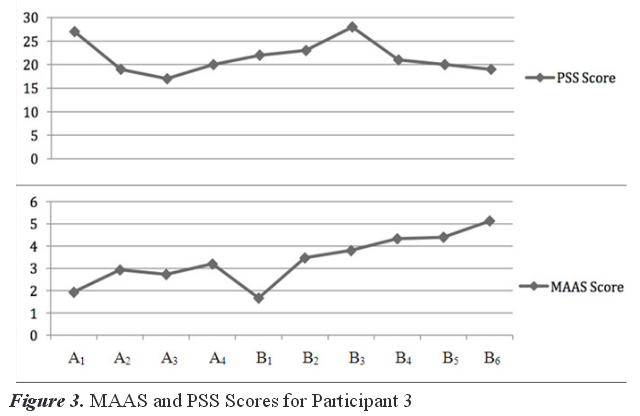

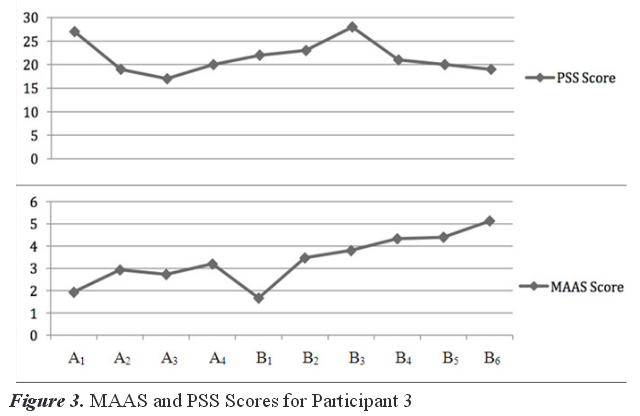

Participant 3 reported no previous experience with mindfulness activities. The baseline mean score on the PSS-10 for Participant 3 was 20.75. This baseline mean score is higher than that of the normative sample. The baseline mean score on the MAAS was 2.7. This baseline mean score is lower than that of the normative sample. The individual scores over the baseline period for the PSS-10 showed a baseline high of 27 at A1. PSS-10 scores dropped eight points from A1–A2.

The individual scores over the baseline period for the MAAS were stable from A2–A 4 with the lowest score (1.93) coming at A1. Participant 3 posted stable baseline scores on both the PSS-10 and the MAAS except for at the first baseline meeting. At this meeting, the stress score was high and the mindfulness score was low.

The intervention mean score on the PSS-10 was 22.17. This score is a 1.42-point gain from the baseline mean in overall self-reported stress as measured by the PSS-10. There was a significant drop of seven points on the PSS-10 from B3–B4, and drops in stress score continued throughout the rest of the intervention phase.

MAAS scores continued to increase throughout the intervention phase with highest score of 5.13 coming at the final session. This is an increase of 1.1 in the mean scores on the MAAS from baseline to intervention and a gain of 3.46 from B1–B6 (see Figure 3). Table 4 lists the dependent measure scores for Participant 3.

Table 4

Dependent Measure Scores for Participant 3

|

|

|

PSS-10

|

|

|

|

MAAS

|

|

|

Session

|

|

Score

|

M

|

SD

|

|

Score

|

M

|

SD

|

| A1 |

|

27

|

|

|

|

1.93

|

|

|

| A2 |

|

19

|

|

|

|

2.93

|

|

|

| A3 |

|

17

|

|

|

|

2.73

|

|

|

| A4 |

|

20

|

20.75

|

4.35

|

|

3.20

|

2.6975

|

0.55

|

| B1 |

|

22

|

|

|

|

1.67

|

|

|

| B2 |

|

23

|

|

|

|

3.47

|

|

|

| B3 |

|

28

|

|

|

|

3.8

|

|

|

| B4 |

|

21

|

|

|

|

4.33

|

|

|

| B5 |

|

20

|

|

|

|

4.40

|

|

|

| B6 |

|

19

|

22.17

|

3.19

|

|

5.13

|

3.8

|

1.19

|

Note. Sessions A1–A4 were baseline sessions; sessions B1–B6 were intervention sessions.

Discussion

The results indicate that exposure to an MBCT intervention can positively impact self-reported stress scores as measured by the PSS-10 and increase self-reported mindfulness scores as measured by the MAAS. All participants in this exploratory study showed gains in mindfulness levels as measured by the MAAS. These results likely occurred due to the fact that most participants began the study with no knowledge of or experience with mindfulness. Once exposed to the practice of meditation and other mindfulness exercises, the participants’ use of mindfulness processes increased steadily.

PSS-10 scores fluctuated during the baseline phase, and that variability could be explained by academic events, evaluative and anticipatory, occurring at the time of administration of the dependent measures. Specifically, the A1 and A4 scores for Participant 1 were both 22. Both of these measurements were taken at high-stress academic times. However, Participant 1’s highest score in the baseline phase (25) came at A3, on Christmas Eve. These scores support the literature that found several factors leading to nursing student stress, including home and academic demands (Magnussen & Amundson, 2003; Pulido-Martos et al., 2012). Consequently, all three participants posted their lowest mindfulness scores on days that coincided with a high-stress academic event such as final exam week, or the day before the first week of classes. However, once the MBCT intervention phase began, two of the participants (1 and 3) showed steady drops in PSS-10 scores, and the third (2) showed conservative reductions, suggesting that the intervention was a likely factor in decreasing perceived stress among the three participants. However, Participant 3’s PSS-10 scores revealed a 1.42-point gain from the baseline to intervention mean. The overall gain in the intervention mean score can be attributed to an unusually high score of 28 on B3. Participant 3 did report increased personal and academic distress at this time in the study. This result also could indicate that the benefits of mindfulness practice can be preempted by reactive stress to specific events. More long-term practice of mindful activities might have mitigated the stress of these events.

Participant 2 posted an overall 2.92-point gain from the PSS-10 baseline mean score to the intervention mean score. This increase may be attributed to an unusually high score of 28 on B1, perhaps because the first session of the intervention fell on the first week of classes for the spring semester. Additionally, Participant 2 had only 50 minutes of exposure to mindfulness activities at this time. However, there was a drop of five points on the PSS-10 from B1–B2. This decrease might be attributed to some type of novelty effect from being introduced to a new treatment (MBCT). This argument is strengthened by the fact that Participant 2 posted stable stress scores throughout the rest of the intervention. It should be noted that Participant 2 informed the researchers after B4 of the need to withdraw from the study due to time constraints and academic demands, but eventually decided to finish the study. This participant acknowledged feeling some personal distress throughout the next two sessions but did not report the need for any additional intervention. For Participant 2, it appears that MBCT was successful overall in increasing self-reported mindfulness levels as measured by the MAAS. Based on the small decreases in PSS-10 scores over time, and the continued self-report of personal distress through the final session, the MBCT intervention was only minimally successful in stress reduction for Participant 2.

Homework assignments and additional meditation practice were highly encouraged in this study, but not required. All participants chose to complete some homework and practice meditations outside the study sessions; however, the reported time spent on meditation practice varied significantly. Ancillary findings from Collard et al. (2008) found a correlation between longer practice times of mindfulness and higher levels of mindfulness. An analysis of the data surrounding participant practice time and levels of obtainment of mindfulness would have been an interesting component to include in this study.

Limitations

One disadvantage of this study is the inherent limitation of single-subject design—specifically, external validity. Because this study included separate experiments with data on only three cases, it is difficult to make generalizations. However, external validity can be enhanced by replicating the design multiple times, thus strengthening possibilities for generalizations (Heppner et al., 2008; Hinkle, 1992). Additionally, Hinkle (1992) discussed issues related to the AB design, specifically stating that “cause and effect cannot be explicitly determined” (p. 392).

The sample was motivated enough to volunteer for the study, which may mean that participants were more stressed than other nursing students and more motivated to seek solutions for stress. Alternatively, the willingness to volunteer for the study may have meant that these participants were less stressed and had more free time to participate in a weekly intervention. Another limitation was the modifications made to the MBCT intervention to accommodate the individual counseling modality. However, because of the exploratory nature of the study, modifications in future studies are warranted.

The use of only one dependent measure for each dependent variable also presents limitations. The PSS-10 and the MAAS measure self-reported stress and mindfulness. The use of other instruments or data to measure the two dependent variables might have strengthened the study. Specifically, a mixed-methods design could have focused on the provided quantitative measures as well as qualitatively analyzing the homework forms and the participant’s verbal session content. Potentially, because of the timing of the study, and because stress is often linked with college student academic failure (American College Health Association, 2013), final exam grades and midterm grades could have been compared to assess for academic changes based on the introduction of the intervention.

Implications for Counseling

This study strengthens the growing research base on the use of MBCT. Specifically, it adds to the literature supporting the efficacy of MBCT in reducing stress. A unique contribution is the use of MBCT in a single-subject experimental design. Typically, MBCT is used in a class format; this study supports the potential efficacy of MBCT in individual sessions.

Based on the above implications, this study also has implications for college counselors and counselors who work with those in stressful professions. Due to high attrition, academic distress and high-stakes testing, colleges are struggling to help their students succeed. College counselors provide services that address the academic and personal well-being of students. This study indicates that the use of MBCT in individual counseling to mitigate stress can yield promising results.

College counselors and faculty members can work together to provide mindfulness-based workshops or other activities that promote a meditative approach. Developing effective partnerships should begin with an assessment of available mindfulness resources. Program administrators want their students to be successful and may be willing to integrate resources from outside the program. Many colleges and universities might have trained counselors on staff who can provide these services. If not, negotiations with certified off-campus meditation or yoga centers could provide reduced rates for students. More importantly, counselors can train faculty members in mindfulness exercises that they can integrate into the fabric of their programs. Embedding mindfulness into academic programs could be more effective and efficient if students perceive it as part of their education instead of an add-on.

College counselors will do well to learn the language and culture of the academic programs on their campus. Crafting mindfulness interventions to correspond directly with the stressors of a certain program might help develop rapport with students. This process could be collaborative, involving college counselors, educators and students. Also, sharing data gathered from program evaluations or studies with administrators can strengthen relationships by assisting with long-term programmatic goals.

Future Areas of Research

Future areas of research should include the use of MBCT and other mindfulness-based interventions in order to replicate these results. More research is needed on delivering MBCT in an individual format. Another component of this study that needs more exploration is whether a longer amount of time spent practicing mindfulness activities provides greater relief from self-reported stress symptoms. The next logical step is to complete a study using a larger sample. Experimental studies comparing the effects of MBCT with more traditional counseling approaches aimed at reducing stress and improving performance could prove useful. How, for example, might MBCT compare to rational-emotive or rational-behavior approaches to reducing stress? Additionally, given the evolving nature of technology-based counseling interventions, future research on MBCT also might explore the value and usefulness of online MBCT interventions. Examining and comparing the effectiveness of synchronous versus asynchronous MBCT interventions would be especially valuable.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

American College Health Association. (2013). American college health association national college health assessment II: Reference group executive summary spring 2013. Hanover, MD: Author.

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review.

Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 125–143. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg015

Barlow, D. H., & Hersen, M. (1984). Single-case experimental designs: Strategies for studying behavior change. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Beddoe, A. E., & Murphy, S. O. (2004). Does mindfulness decrease stress and foster empathy among nursing students? Journal of Nursing Education, 43, 305–312.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., . . . Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230–241.

Brown, A. P., Marquis, A., & Guiffrida, D. A. (2013). Mindfulness-based interventions in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91, 96–104. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00077.x

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Chapman, R. A., Baker, S. B., Nassar-McMillan, S. C., & Gerler, E. R. (2011). Cybersupervision: Further examination of synchronous and asynchronous modalities in counseling practicum supervision. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50, 298–313.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health: Claremont symposium on applied social psychology (pp. 31–67). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Collard, P., Avny, N., & Boniwell, I. (2008). Teaching mindfulness based cognitive therapy (MBCT) to students: The effects of MBCT on the levels of mindfulness and subjective well-being. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 21, 323–336. doi:10.1080/09515070802602112

Gibbons, C., Dempster, M., & Moutray, M. (2011). Stress, coping and satisfaction in nursing students. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67, 621–632. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05495.x

Grabovac, A. D., Lau, M. A., & Willett, B. R. (2011). Mechanisms of mindfulness: A Buddhist psychological model. Mindfulness, 2, 154–166. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0054-5

Harrington, N., & Pickles, C. (2009). Mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral therapy: Are they compatible concepts? Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23, 315–323.

Harris, R. C., Rosenberg, L., & O’Rourke, G. (2014). Addressing the challenges of nursing student attrition. Journal of Nursing Education, 53, 31–37. doi:10.3928/01484834-20131218-03.

Heppner, P. P., Wampold, B. E., & Kivlighan, D. M. (2008). Research design in counseling (3rd. ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson-Brooks/Cole.

Hinkle, J. S. (1992). Computer-assisted career guidance and single-subject research: A scientist-practitioner approach to accountability. Journal of Counseling and Development, 70, 391–395.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Bantam Dell.

Kuyken, W. R., Byford, S., Taylor, R. S., Watkins, E., Holden, E., White, K., . . . Teasdale, J. D. (2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to prevent relapse in recurrent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 966–978. doi:10.1037/a0013786.

Lau, M. A., & Yu, A. R. (2009). New developments in research on mindfulness-based treatments: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23, 179–184.

Lundervold, D. A., & Belwood, M. F. (2000). The best kept secret in counseling: Single-case (N = 1) experimental designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78, 92–102. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb02565.x

Ma, S. H., & Teasdale, J. D. (2004). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: Replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 31–40.

MacKillop, J., & Anderson, E. J. (2007). Further psychometric validation of the mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29, 289–293. doi:10.1007/s10862-007-9045-1

Maddux, M., & Maddux, R. (Producer). (2006, December 5). Breath awareness meditation. [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/meditation-oasis/id204570355?mt=2

Magnussen, L., & Amundson, M. J. (2003). Undergraduate nursing student experience. Nursing and Health Sciences, 5, 261–267.

Morgan, D. L., & Morgan, R. K. (2003). Single-participant research design: Bringing science to managed care. In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research (3rd ed., pp. 635–654). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pulido-Martos, M., Augusto-Landa, J. M., & Lopez-Zafra, E. (2012). Sources of stress in nursing students: A systematic review of quantitative studies. International Nursing Review, 59, 15–25.

Roberti, J. W., Harrington, L. N., & Storch, E. A. (2006). Further psychometric support for the 10-item version of the perceived stress scale. Journal of College Counseling, 9, 135–147.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Sharpley, C. F. (2007). So why aren’t counselors reporting n = 1 research designs? Journal of Counseling & Development, 85, 349–356. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00483.x

Stickney, M. C. (2008). Factors affecting practical nursing student attrition. Journal of Nursing Education, 47, 422–425.

Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M., Ridgeway, V. A., Soulsby, J. M., & Lau, M. A. (2000). Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 615–623.

Wright, S. (2007). Meditation matters. Nursing Standard, 21, 18–19.

Mark J. Schwarze, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at Appalachian State University. Edwin R. Gerler, Jr. is a Professor at North Carolina State University. Correspondence can be addressed to Mark J. Schwarze, Reich College of Education, Department of Human Development and Psychological Counseling, 151 College Street, Appalachian State University, Box 32075, Boone, NC 28608-2075, schwarzem@appstate.edu.

Feb 9, 2015 | Article, Volume 5 - Issue 1

Heather Barto, Simone Lambert, Pamelia Brott

Career adaptability, resiliency and perceived obstacles to career development of adolescent mothers were examined using a proposed conceptual framework that combined resiliency and career adaptability. The goals of this study were to gauge the current state of the career development and resiliency of adolescent mothers, including areas of strength and weakness, and to better understand the interactions between the three components of career adaptability (i.e., planfulness, exploration, decision-making), resiliency and perceived obstacles. Adolescent mothers were similar to nonparenting peers on the planfulness and decision-making dimensions of career adaptability, yet lower on career exploration. While adolescent mothers’ traits of personal resiliency and emotional reactivity were comparable to those of their peers, their relational resiliency was lower. Based on the findings of the study, proposed strategies to further the three components of career adaptability and the resiliency of adolescent mothers are suggested.

Keywords: adolescent mothers, career development, career adaptability, resiliency, decision-making

In the United States, becoming a parent during adolescence has been described as a premature and nonnormative life event that can present lifelong challenges and growth opportunities in the career development of adolescent mothers (Gruber, 2012; Zachry, 2005). Taylor (2009) reported the most prevalent negative outcomes associated with adolescent parenthood as lowered high school graduation rates, limited educational opportunities after high school, and difficulty achieving stable work and financial independence. These are important career development considerations for this population given the national statistics on adolescent motherhood, previous research findings on the impact of parenting programs on the long-term career outcomes for adolescent mothers, and the viability of the proposed theoretical framework of the integration of career adaptability and resiliency (Barto, Lambert, & Brott, in press).

The national statistics on adolescent mothers indicate a disparity between racial groups with 8.3% of Latina, 6.5% of African American and 2.7% of Caucasian (non-Hispanic) adolescent females becoming mothers (Guttmacher Institute, 2010). Race and ethnicity may influence how an adolescent pregnancy is perceived by the adolescent mother and those around her, further contributing to the mother’s obstacles to and opportunities for career development (McAdoo, 2007; Santiago-Rivera, Arredondo, & Gallardo-Cooper, 2002). Support from families has been shown to be a positive factor in furthering the career development of adolescent mothers (Brosh, Weigel, & Evans, 2009). Although both African American and Latino families may be disappointed by adolescent pregnancies, these families tend to discourage pregnancy termination or adoption, instead offering assistance to adolescent mothers (McAdoo, 2007; Santiago-Rivera et al., 2002). Conversely, Caucasian adolescent mothers have the highest rates of formal adoptions outside the family; thus, family support for attempting to combine motherhood and career development may be lower for Caucasian adolescent mothers than for adolescent mothers in other racial or ethnic groups (Low, Moely, & Willis, 1989).

Adolescent mothers typically report more challenges with life planning when compared to nonparenting peers (Spear, 2004). Related issues can be viewed through the lens of obstacles to and opportunities for career development for adolescent mothers. These obstacles may include completing an education, finding employment and experiencing increased financial strain. Conversely, becoming a mother during adolescence may stimulate resiliency and growth opportunities in the working role (Zachry, 2005). These opportunities could foster the desire to provide financially for self and child, positive attitudes toward the future after becoming a mother (Brubaker & Wright, 2006), and a greater sense of maturity and purpose about the future (Rosengard, Pollock, Weitzen, Meers, & Phipps, 2006). Therefore, adolescent parenting can be simultaneously stressful and meaningful (Perrin & Dorman, 2003) while impacting all areas of life, particularly the working role.

Career development can be viewed as a holistic, dynamic and lifelong process, whereby individuals construct meaning and determine the most appropriate expression of their life roles (Savickas et al., 2009). Life roles are conceptualized as a constellation of interacting enactments that have relative importance to the individual within the context that these roles occur (Brown & Associates, 2002). For adolescent mothers, the addition of the parenting role can influence the dynamics between life roles and affect the perceived importance of the working role (Savickas, 1997).

In both school (Kaplan, Blinn-Pike, Wittstruck, Berger, & Leigh, 2002) and community settings (Gruber, 2012; Sarri & Phillips, 2004), programs and services are designed to meet the unique needs of adolescent mothers. Adolescent mothers have reported that parenting programs are moderately helpful in providing information relevant to their parenting role, such as medically related advice to improve the health of child and mother (Sarri & Phillips, 2004). However, these programs typically do not address finding employment and educational training opportunities (Kaplan et al., 2002, Sarri & Phillips, 2004).

Longitudinal studies investigating the career outcomes (i.e., being employed and self-supporting adults) for adolescent mothers participating in parenting programs have produced mixed results. Horwitz, Klerman, Kuo, and Jekel (1991) reported that 82% of the mothers who participated in an adolescent parenting program were financially self-supporting 20 years later. However, Taylor (2009) reported that when compared with nonparenting peers, adolescent parents had lower incomes and less prestigious occupations 20 years later. Neither Horwitz et al. (1991) nor Taylor (2009) indicated which program components helped or hindered participants’ career outcomes. Research is needed to derive evidenced-based intervention strategies and programs for improving career development outcomes of adolescent mothers (Brindis & Philliber, 2003). In the current study, career adaptability and resiliency were used to better understand career development of adolescent mothers as they adjust to their new role as a parent in relation to other life roles, especially the role of worker. Career adaptability includes the dimensions of planning, exploring and decision-making about one’s future (Savickas, 1997). Resiliency includes the attributes to develop personal and relational strengths in the process of overcoming adversity (Prince-Embury, 2006). In the current study, attention was given to the unique obstacles in the adolescent mother’s career development, as she constructs meaningful expression of her working role (Klaw, 2008; Savickas et al., 2009). The goals of this study were to gauge the current state of the career development and resiliency of adolescent mothers, including areas of strength and weakness; and to better understand the interactions between the components of career adaptability, resiliency and perceived obstacles.

Conceptual Framework

Limited research has focused specifically on the career development and adaptability of adolescent mothers (e.g., Brosh et al., 2009). From a review of the literature, the current authors (in press) found the following impediments to career development of adolescent mothers: pressing immediate needs (e.g., housing, transportation, childcare), limited career development skills (e.g., decision-making skills) and lack of career-related knowledge (e.g., occupational information). Based on the existing literature, a career resiliency model has been suggested to promote career adaptability among high-risk individuals who are experiencing a dramatic life event, such as adolescent mothers (Rickwood, 2002; Rickwood, Roberts, Batten, Marshall, & Massie, 2004). The proposed conceptual framework for the career development of adolescent mothers combines resiliency and career adaptability and (a) addresses challenges (e.g., obstacles), (b) capitalizes on opportunities and strengths (e.g., increased sense of maturity/responsibility), and (c) develops positive intervention strategies and programs to better the long-term outcomes of adolescent mothers. Constructs that support this framework are career adaptability and resiliency, as previously combined by Rickwood (2002) and Rickwood et al. (2004).

Career Adaptability

Career adaptability is a central construct in adolescent career development (Hirschi, 2009) and is defined as the ability to adjust oneself to fit new and changed circumstances in one’s career by planning, exploring and making decisions about one’s future (Brown & Associates, 2002; Savickas, 1997). Planfulness is a learned skill that allows individuals to develop a future orientation to increase adaptability (Savickas, 1997). Exploration encompasses the understanding of relationships between individual differences and contextual factors that influence career development (Blustein, 1997). In the current conceptual framework, decision-making is expanded beyond the traditional models of career development to consider the multiple alternatives and objectives that are present in the career decision-making process (Phillips, 1997).

Career adaptability is currently used as a theoretical basis for both (a) the assessment of career-related skills and knowledge, and (b) the development and implementation of intervention strategies for adolescents (Creed, Fallon, & Hood, 2009; Hirschi, 2009). The concept of career adaptability is applicable to adolescent mothers, as it focuses on developing skills to address the individual and contextual factors associated with career development (Savickas et al., 2009). These career adaptability skills (i.e., planning, exploring, decision-making) are most relevant to the working role, but can be generalized and utilized easily in considering other life roles (e.g., parenting).

Resiliency

Resiliency has been defined as one’s ability to overcome adversity and be successful (Greene, Galambos, & Lee, 2004). This concept represents a paradigm shift from looking at risk factors associated with problematic situations to searching for more strengths-based personal attributes that help individuals overcome adverse or stressful situations (Richardson, 2002). Some researchers believe that resiliency is a combination of protective factors (i.e., personal characteristics and relationships) and areas of vulnerability (i.e., ability to self-regulate through adversity; Prince-Embury, 2006; Richardson, 2002; Zachry, 2005). In the current study, mastery (i.e., internalized personal characteristics of optimism, self-efficacy and adaptability) is referred to as personal resiliency. Relatedness (i.e., social and relational experience concerning trust, support, comfort and tolerance) is referred to as relational resiliency, and emotional reactivity (i.e., level of sensitivity, recovery and impairment to self-regulation in response to adverse events or circumstances) is referred to as emotional vulnerability (Prince-Embury, 2006; Richardson, 2002). These three resiliency constructs are helpful in understanding the attributes that are displayed by resilient individuals who are able to adapt to difficult or stressful situations (Prince-Embury, 2006; Richardson, 2002).

Researchers have measured the resiliency of adolescent mothers in various ways. For example, resiliency has been paired with the assessment of risks to better understand both the risks and protective factors that promote resiliency, thus moderating the negative effect of adolescent motherhood (Kennedy, 2005). Black and Ford-Gilboe (2004) used resiliency to validate and predict theoretical relationships among variables associated with creating a healthy family environment for adolescent mothers. Furstenberg, Brooks-Gunn, and Morgan (1987) found that a substantial portion of adolescent mothers demonstrated resiliency by overcoming the challenges of adolescent parenthood through maintaining regular employment and establishing financial stability without the need for public assistance (as cited in Kennedy, 2005). In summary, resiliency is thought to be one of the factors influencing the degree of success that adolescent mothers experience as adults (e.g., Schilling, 2008).

Career Adaptability and Resiliency

Linking career adaptability to resiliency may be more favorable to adolescent mothers than approaches that focus on risk factors, problems associated with adolescent motherhood, and career-related skill deficiencies (Perrin & Dorman, 2003). However, even resilient mothers can find the day-to-day demands of motherhood overwhelming. Without attention to the obstacles they may encounter, adolescent mothers may be unable to attend to career adaptability skill development (Klaw, 2008). Recognizing and addressing these pressing immediate needs helps adolescent mothers gain the ability to focus attention and effort on developing their personal career adaptability (Klaw, 2008).

Furthermore, adolescent mothers need to cultivate their own personal and relational attributes in order to foster and encourage resiliency (Zippay, 1995). Personal characteristics (i.e., optimism, self-efficacy, adaptability) can influence levels of resiliency (Prince-Embury, 2006). Socially supportive relationships based on trust, support, comfort and tolerance with family members and mentors have been effective in helping further the career adaptability of adolescent mothers by providing them with career-related information and aiding them in developing career-related skills (Klaw, Rhodes, & Fitzgerald, 2003; Prince-Embury, 2006). Both career adaptability skills and higher levels of personal and relational resiliency may be helpful in overcoming the obstacles experienced by adolescent mothers.

The Current Study

In the present study, the current state of career adaptability, resiliency and potential obstacles to career development among adolescent mothers from one state in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States was examined. Data were gathered using the career planning (CP) scale from the Career Development Inventory-School Form (CDI-S; Super, Thompson, Lindeman, Jordaan, & Myers, 1979), the self-exploration and environmental exploration scales from the Career Exploration Survey (CES; Stumpf, Colarelli, & Hartman, 1983), the Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (CDSE-SF; Betz, Klein, & Taylor, 1996), the Resiliency Scales for Children and Adolescents (RSCA; Prince-Embury, 2006), and the Obstacle Survey (Klaw, 2008). The participants also received a demographic questionnaire. The research questions that guided the study included the following: (1) What are the relationships between the dimensions of career adaptability (i.e., planfulness, exploration, decision-making) and resiliency? (2) What are the reported obstacles to the career development of adolescent mothers? (3) Can measures of resiliency predict career adaptability in adolescent mothers?

Method

Participants

Participants in community- and school-based parenting programs were solicited for the study. The community-based parenting program is a support and self-help organization for assisting members in becoming more self-sufficient, but no specific career development component exists. The school-based parenting program addresses the unique academic, career and personal issues of parenting students, allowing attainment of a high school diploma in an alternative school setting. Study participants (N = 101) ranged in age from 15–18 years old (65%) and 19–21 years old (35%). Participants’ racial backgrounds included Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin (74%); African American (22%); Caucasian (2%); Asian American (1%); and bi-racial (1%). Roughly half (52%) indicated that English was not the primary language used in their home. All participants had at least one child; some participants had multiple children (one mother had three children, 12 mothers had two children and 14 were currently pregnant with their second child).

Their current living situations included residing with parent or grandparent (57%), with their child(ren)’s father (20%), in foster care with their child(ren) (9%), with family of their child(ren)’s father (8%) or on their own with their child(ren) (6%). Their primary source of income support was from parents and family (38%), their child(ren)’s father or his family (32%), self (20%) or assistance programs (10%). While most participants (63%) reported not being currently employed, 53 participants indicated that they were actively looking for a job; 31 participants worked part-time and six worked full-time. Only seven participants had graduated high school and were not currently enrolled in school. The remaining participants included ninth graders (11%), tenth graders (16%), eleventh graders (26%), twelfth graders (31%) and college students (9%). Participants indicated that their educational plans included pursuing a college degree (65%), only graduating from high school (23%), unsure (7%) and at risk for not graduating from high school (4%).

Instruments

Career Development Inventory-School Form. The CDI-S has been utilized to assess the career development and adaptability of adolescents (Super et al., 1979; Thompson & Lindeman, 1981). For this study, the CDI-S’s CP scale was used, with 12 items for career-planning engagement and eight items for career knowledge. Items are rated on a five-point Likert-type scale: career-planning engagement ranges from 1 (I have not yet given thought to this) to 5 (I have made definite plans and know what to do to carry them out); career knowledge ranges from 1 (hardly any knowledge) to 5 (a great deal of information). For female students in grades 9–12 for the CP scale, CDI-S reliability alphas range from .87–.90 (Betz, 1988; Thompson & Lindeman, 1981). The reliabilities for the current study were .89 for both CP subscales and .90 for the total scale. The content validity has been demonstrated on all scales and subgroups; the factor structure was validated as the scale items appropriately loaded on the subscales (Thompson & Lindeman, 1981). Both content and construct validity have been supported (Savickas & Hartung, 1996).

Career Exploration Survey. The CES (Stumpf et al., 1983) was developed to measure aspects of the career exploration process, including reactions and beliefs (Stumpf et al., 1983). The following two subscales were used in the current study to measure career exploration behaviors: the six-item subscale on environmental exploration (e.g., learning about specific jobs and careers) and the five-item subscale on self-exploration (e.g., reflecting on future career choice based on past experiences). Frequency of career exploration behaviors are self-rated on a five-point Likert scale. The reliabilities reported for the self-exploration and environmental exploration subscales are .87 and .88, respectively (Stumpf et al., 1983). Acceptable content and construct validity have been established (Creed et al., 2009; Stumpf et al., 1983).

Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form. The CDSE-SF (Betz et al., 1996) measures one’s confidence in making career-related decisions. The 25-item instrument measures self-reported career decision-making behaviors on five subscales: self-appraisal, occupational information, goal selection, planning and problem solving. Reported reliabilities for the subscales range from .73–.83, and reliability for the total scale is .94 (Taylor & Betz, 1983). Content, concurrent and construct validity of the CDSE-SF have been established (Betz, Klein, & Taylor, 1996; Taylor & Betz, 1983).

Resiliency Scales for Children and Adolescents. The RSCA identifies resiliency attributes in children and adolescents (Prince-Embury, 2006) using three scales: Sense of Mastery (MAS), Sense of Relatedness (REL) and Emotional Reactivity (REA). The MAS, which assesses personal resiliency, includes 20 items in three subscales (optimism, self-efficacy and adaptability). The REL assesses relational resiliency and has 24 items in four subscales (sense of trust, support, comfort and tolerance). Emotional vulnerability is measured by the REA, which includes 20 items in three subscales (sensitivity, recovery and impairment). The sum of the subscale scores became the raw score for the respective scale (MAS, REL, REA), which converts to a T score. Higher T scores on the MAS and REL scales and lower scores on the REA indicate more resiliency resources.

The RSCA reliability alphas range from .79–.90 for 15- to 18-year-old females and are considered acceptable (Prince-Embury, 2006). Convergent and divergent validity have been correlated with those of conceptually similar instruments that measure resiliency (e.g., Reynolds Bully Victimization Scale); the criterion validity was established by comparing groups of clinical samples to matched groups of nonclinical samples of children and adolescents (Prince-Embury, 2006).

Obstacle Survey. The OS (Klaw, 2008) was designed to determine the specific obstacles that adolescent mothers encounter in daily life that could potentially impede their career adaptability, such as needing childcare and facing discrimination because of race. The survey consists of 26 items that could potentially impact participants’ career adaptability. The OS is a relatively new instrument designed for use with adolescent mothers; therefore, there is little information available about psychometric properties. However, the information provided by the OS was expected to be helpful in developing a better understanding of the perceived obstacles to the career adaptability of adolescent mothers.

Demographic Questions. The demographic items were 12 questions designed to gather the following information about the participants: age, racial/ethnic identity, language used in the home, number and age(s) of children, living situation, socioeconomic status, current school status, and employment status.

Procedure

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board, the first author developed relationships with the directors of one community-based and one school-based parenting program in order to recruit study participants. All adolescent mothers in both programs who met the study criteria received the opportunity to participate in the study. Given the unstructured nature of both programs, it is unclear what exact percentage of study-eligible adolescent mothers elected not to participate in the study, but informal observations from the first author suggest that almost all the study-eligible adolescent mothers completed the survey. Attendance was voluntary in the community-based program, so the number of adolescent mothers present varied from week to week, but the first author was present at a total of four meetings. For the school-based program, the first author made two scheduled visits to the school, during which she invited adolescent mothers who were present in classes specifically provided for them (e.g., life skills, support group) to participate in the study. Participants under age 18 received parental permission forms and older participants received informed consent forms. Participants completed all instruments via the computer using an online questionnaire created in Survey Monkey, with the exception of the RSCA (Prince-Embury, 2006), which they completed using a paper-and-pencil version as the publisher required. Survey completion was untimed. Participants who completed all aspects of the study received $10.00 in compensation to encourage completion. Three incomplete surveys were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Results

Career adaptability, resiliency and perceived obstacles were measured using a number of established instruments in order to generate descriptive statistics to better understand the current state of adolescent mothers’ career development. Career adaptability and resiliency were correlated to look for relationships between the two and entered into a multiple regression to determine the predictive power. Career adaptability was defined as and measured by the participants’ process of planfulness, exploration and decision-making. In the area of career planfulness, participants’ scores were slightly higher than the average score for the norm sample of female adolescents (Thompson & Lindeman, 1981): CP (M = 3.34, SD = 0.78), career-planning engagement (M = 3.15, SD = 0.93) and career knowledge (M = 3.61, SD = 0.88). This finding suggests that adolescent mothers in this study were similar to their peers in terms of career planfulness. For career exploration (M = 2.73, SD = 0.99), participants reported a moderate amount of career exploration behaviors with slightly higher self-exploration (M = 3.16, SD = 1.12) involving reflection on one’s future career and past experiences, than environmental exploration (M = 2.34, SD = 1.08) that involves investigating career possibilities. The reliabilities for the current study were .89 for both CP subscales and .90 for the total scale. In terms of career decision-making, there was little variation between the total score (M = 3.26, SD = 0.95) and each of the subscale scores, which ranged from 3.12–3.37. The subscale reliabilities ranged from .87–.90, and reliability for the total scale was .90. Thus, participants were neither strong nor weak in terms of decision-making skills related to selecting a college major, determining one’s ideal job, deciding on values related to occupations and preparing for a job search.

Regarding resiliency, participant T scores for the three scales and scaled scores for the subscales were compared to those of the female adolescent norm group (Prince-Embury, 2006). T scores over 60 are considered high, 50–59 are above average, 46–49 are average, 41–45 are below average, and below 40 are low. The reported T scores for participants were average for both the MAS (M = 48.29, SD = 7.93) and the REA (M = 49.44, SD =10.58) and below average for the REL (M = 44.47, SD = 10.11). The manual reports that scaled scores for the subscales over 16 are considered high, 13–15 are above average, 8–12 are average, 5–7 are below average, and below 5 are low. The related subscale scores for the MAS were average (M = 9.45–9.75); subscales for the REL were average (M = 8.12–8.75); and subscales for the REA were average (M = 9.80–10.39). The subscale reliabilities ranged from .57–.87 and the scale reliabilities ranged from .84–.93.

The participants rated 25 perceived obstacles using the OS (Klaw, 2008). The obstacles were organized into seven categories plus other to capture themes that have been reflected in the literature (e.g., pressing immediate needs, work-related concerns, education-related concerns). Ratings of 2 (somewhat of a concern) and 3 (a large concern) were combined and categorized for descriptive and contextual purposes. The most frequent obstacles for adolescent mothers were related to pressing immediate needs (childcare [73%] and transportation [72%]), work-related concerns (need for more job training [72%] and not many jobs available in my area [72%]), and education-related concerns (need more preparation to continue my education [71%] and need money to continue my education [68%]). Another identified obstacle was health-related concerns for mother or child (68%). Of lesser concern for these adolescent mothers was discrimination (facing discrimination because I am a woman [26%] and facing discrimination because of where I live [20%]) and relationship concerns (parents wanting me to work full-time [27%] and my baby’s father doesn’t want me to work [19%]). Deviant behaviors do not appear to be obstacles for most adolescent mothers surveyed; these behaviors include education-related concerns such as suspended/expelled from school (14%) and community concerns such as fear of community violence (21%), being in jail or in trouble with the police (14%), and being part of a gang (5%).

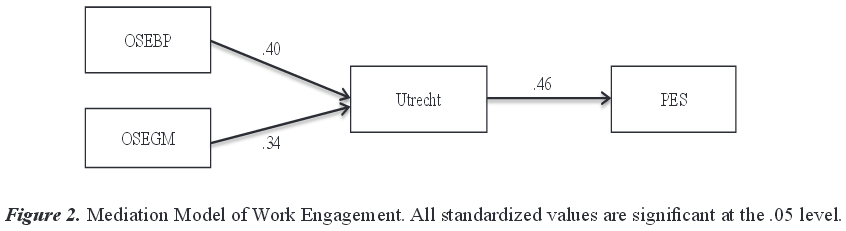

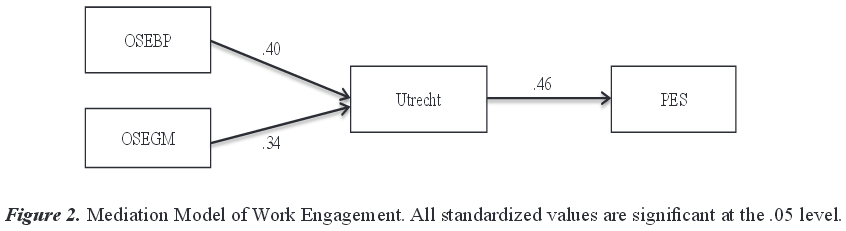

Relationships Between Career Adaptability and Resiliency