Dec 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 5

Kelly Duncan, Kathleen Brown-Rice, Gerta Bardhoshi

This study explored rural school counselors’ perceptions of clinical supervision. School counselors working in rural communities commonly encounter issues that challenge their ability to provide competent counseling services to the students they serve. School counselors serving in these areas are often the only rural mental health provider in their community, and they may lack access to other professionals to meet supervision needs. Participants’ (n = 118) current experiences and future needs were investigated concurrently with supervision training and delivery methods most desired. The majority of school counselors in the study reported that they perceive clinical supervision as an important element in their continued personal and professional growth. However, these school counselors reported not receiving supervision at an individual, group or peer level. The need for the supervision is apparent; however, access to supervision in rural areas is limited. Implications for school counselors and recommendations for future research are discussed.

Keywords: rural school counselors, clinical supervision, supervision training, personal and professional growth, rural mental health

With increasing regularity, school counselors are finding themselves on the front lines of using clinical counseling skills to address issues their students bring to school (Teich, Robinson, & Weist, 2007; Walley, Grothaus, & Craigen, 2009). Despite an increase in the mental health needs of school-aged children (Perfect & Morris, 2011), limited mental health services are a reality in rural areas (Bain, Rueda, Mata-Villarreal, & Mundy, 2011). Although there is not a clear definition of the term rural, the U.S. Census Bureau (2010) has characterized urban areas as those with 50,000 or more people, and urban clusters as those communities with a population of 2,500–49,999. School counselors working in rural communities commonly encounter issues that challenge their ability to provide competent counseling services to students (Cates, Gunderson, & Keim, 2012). In fact, school counselors serving in rural areas are often the only mental health provider in their community, and they may lack access to other professionals to meet supervision needs (Bardhoshi & Duncan, 2009).With mental health needs in rural areas being greater than the resources available, and rural school counselors indicating a need for more mental health training and resources to close this gap (Bain et al., 2011), meeting the professional needs of rural school counselors becomes imperative.

Bradley and Ladany (2010) described the competent school counselor as a skilled clinician able to identify and meet the unique needs of the students he or she serves. They further asserted that rural areas provide unique demands for the school counselor, who is often expected to provide a wide range of services to a diverse population. Despite recommendations that professional counselors obtain supervision throughout their careers, traditional face-to-face supervision meetings are not always feasible and rural counselors may not have direct access to a supervisor, even though they have a desire for one (Luke, Ellis, & Bernard, 2011;Tyson, Pérusse, & Stone, 2008). Although there is a need for trained professional supervisors, supervision in rural areas is difficult to obtain for many counselors because of the distance between professionals, which creates geographic isolation (Wood, Miller, & Hargrove, 2005).

There are a number of challenges to receiving quality supervision. Rural school counselors encounter isolation, lack of time and money, a lack of specialists, and decreased personal interaction (McMahon & Simons, 2004). All of these characteristics of working in a rural setting make supervision and consultation, which are essential in the development of a professional identity, difficult to obtain (McMahon & Simons, 2004).

Clinical supervision is designed to aid the professional counselor in enhancing professional skill and ethical competency (Bradley & Ladany, 2010). A clinical supervisor in the schools must be a professional who is not only competent in the realm of school counseling functions, but also in supervision practices (Gysbers & Henderson, 2000). The supervision element of school counseling is further complicated as there often is a need for different types of supervision. There is need for both administrative and clinical supervision for practicing school counselors (Bradley & Ladany, 2010), and at times these different types of supervision may conflict with one another. Administrative supervision focuses on policies and procedures governing the school community, and this form of supervision in a school setting is most often performed by a school administrator who may not have a counseling background (Henderson & Gysbers, 1998). In comparison, clinical supervision is an intervention that a senior member of the profession delivers to a junior member in order to enhance professional abilities and monitor the counseling services offered (Bernard & Goodyear, 2009). This reality of school counseling supervision would suggest that those providing clinical supervision need to not only be certified as school counselors in order to qualify as senior members of the profession, but also have supervision training in order to effectively carry out supervision interventions.

For school counselors, supervision is a direct venue for providing or receiving support and feedback (Lambie, 2007). Both peer consultation and supervision are related to lower levels of stress in school counselors (Culbreth, Scarborough, Banks-Johnson, & Solomon, 2005). There is evidence that obtaining clinical supervision is indeed beneficial to school counselors, with research pointing to professional and personal gains, including enhanced counseling skills, sense of professionalism, support and job comfort (Agnew, Vaught, Getz, & Fortune, 2000). There also are a number of studies examining the protective utility of clinical supervision regarding school counselor burnout. Prevention of burnout is an important issue for rural school counselors who report feelings of frustration as they struggle to provide as much counseling as possible to their students (Bain et al., 2011).

When assessing the effect of clinical supervision on burnout, Feldstein (2000) reported that clinical supervision had a positive effect on reducing levels of emotional exhaustion and burnout in school counselors. In a recent study, Moyer (2011) reported that the amount of clinical supervision received was a significant predictor of overall burnout in school counselors (as well as the dimensions of incompetence, negative work environment and devaluing clients). These findings support the notion that clinical supervision may serve as an important protective factor against burnout for school counselors, and even ameliorate burnout levels once manifested. A similar recommendation was provided by Lambie (2007), who identified clinical supervision as an essential resource that can be utilized to overcome school counselor burnout.

Even though administrative supervision generally is available to school counselors, clinical supervision usually is not (Herlihy, Gray, & McCollum, 2002). Page, Pietrzak, and Sutton (2001) reported in their national survey (n = 267) that only 13% of school counselors were receiving individual clinical supervision and only 10% were receiving group clinical supervision, despite a desire to obtain supervision. A study examining rural school principals’ perceptions of school counselors’ role noted that approximately 12% of all respondents deemed professional development of little importance for school counselors (Bardhoshi & Duncan, 2009). Consequently, clinical supervision may not be supported in rural settings, as time spent in supervision may be seen as time taken away from understaffed schools.

Clinical supervision is best delivered by a counselor who is not only trained in supervision but who is also familiar with K–12 school settings (Bradley & Ladany, 2010). Despite school counselors’ desire to obtain more clinical supervision once working in a school setting, many face a challenge in obtaining such supervision. Peterson and Deuschle (2006) also discussed hesitation from school counselors to be supervisors, which could result from discomfort with the requirements of site supervision, or a feeling of being poorly trained in supervision. Supervision is, however, an important part of developing the professional and ethical decision-making skills that benefit clients and their stakeholders (Lambie, Ieva, Mullen, & Hayes, 2011). Due to these needs, developing trained school counselor supervisors is a vigorous step in meeting the supervision needs of school counselor trainees and practicing professionals (Page et al., 2001).

The purpose of the current study was twofold. The first purpose was to assess the current perceptions of certified school counselors serving in rural settings (RCSCs) regarding their clinical supervision experience and needs. The second purpose was to compare and contrast the current data with empirical data obtained 9 years ago in this same state from RCSCs, in order to examine whether the supervision needs of counselors in rural settings has changed. Specifically, the study was designed to answer the following research questions: (a) What are RCSC perceptions of the importance of individual, group and peer supervision? (b) What are participants’ current experiences with individual, group and peer supervision? (c) What are participants’ perceptions of their future need for clinical supervision? (d) If the training were available to equip a participant with the theory and skills to provide clinical supervision, how would respondents rate the importance of this training and by what means would participants prefer to receive this training? (e) How do current RCSC experiences and perceptions of individual, group and peer clinical supervision compare to the findings in a 2003 study of RCSCs?

In this study, RCSC refers to an individual certified by a state department of education working in a school in a state where the majority of school districts have fewer than 1,000 students. The terms certified and licensed are interchangeable. Clinical supervision is defined as an intensive, interpersonal focused relationship, usually performed one-to-one or in a small group, in which the supervisor facilitates the counselor(s) learning to apply a wider variety of assessment and counseling methods to increasingly complex cases (Bradley & Ladany, 2010). A clinical supervisor refers to a certified school counselor, licensed mental health professional counselor, social worker or psychologist who has at least 5 years’ experience in the field. Administrative supervision is defined as an ongoing process in which the supervisor oversees staff as well as the planning, implementation and evaluation of individuals and programs (Henderson & Gysbers, 1998).

Method

Participants

The target population for this study included all certified school counselors (CSCs) in a Midwestern state who were employed in a public or private school setting during the school year 2011–2012. Recruitment of participants was conducted by obtaining a list of all CSCs from the state’s Department of Education. All individuals who were identified as meeting these criteria received an e-mail. The e-mail directed participants to an online survey titled The 2012 School Counselor Survey. The number of CSCs provided by the Department of Education was 476. A total of 127 CSCs responded to the invitation to take part in this study, all of whom met the criteria for employment in a rural setting, resulting in a response rate of 27%. Respondents with missing or invalid data (n = 9, less than 7%) were eliminated via listwise deletion, leaving a total number of 118 participants in this study. Listwise deletion entails eliminating participants with missing data on any of the variables and is the appropriate method for removal of missing data due to this study’s sufficient sample size (Sterner, 2011).

Of the 118 participants (91 women, 27 men), 110 identified their cultural/racial background as Caucasian, five identified as Native American and three identified as Multiracial. Thirty-four participants stated their age as 25–35 years, 31 as 36–45 years, 30 as 46–55 years and 23 as 56 years or older. The majority of the respondents identified as married (n = 96), 15 as single and seven as having a life partner or being in a committed relationship. Twelve of the participants stated that they had 2 or fewer years of experience as school counselors, 18 had 3–5 years, 25 had 6–10 years, 42 had 11–20 years, 19 had 21–30 years and two stated that they had 40 or more years of experience. Regarding licenses and certifications held, 109 of the participants stated that they were South Dakota CSCs, 36 were National Certified Counselors, 12 were Licensed Professional Counselors, two held the Licensed Professional Counselor–Mental Health designation and one participant identified as a National Certified School Counselor.

Regarding the number of schools under participants’ direct responsibility, 86 indicated that they had one school, 21 had two schools, five had three schools, four had four schools and two had five schools. Five participants stated that they were responsible for direct counseling services for 100 or fewer students, 14 for 101–200 students, 22 for 201–300 students, 29 for 301–400 students, 18 for 401–500 students, 14 for 501–600 students, 10 for 601–700 students and six for 701 or more students. Twenty-one stated that there were no other school counselors in their school district, 15 stated that there was one other school counselor, 17 stated that there were two others, 13 stated that there were three to five, 29 stated that there were six to 11, seven stated that there were 12–18, six stated that there were 20–25, four stated that there were 45–50, five stated that there were 52–56 and one stated that there were 60 other school counselors in the participant’s district. Regarding the number of other school counselors working with them in the same building, 58 respondents stated that there were no other counselors, five stated that there was another part-time counselor, 29 stated that there was one other full-time counselor, 11 stated that there were two, four stated that there were three, five stated that there were four and six participants stated that there were five other counselors in their building.

Instrumentation

Participants completed a modified version of the school counselor survey used by Page et al. (2001) in their national survey of school counselor supervision. The modifications included additional questions related to participants’ perceptions of the usefulness of receiving supervision and supervision training via distance methods. Distance methods included the statewide video conferencing system, teleconference and e-mail. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 19.0) was utilized to screen the data, gather descriptive data and analyze the data, as well as to determine frequencies and percentages for the demographic variables. To answer the research questions, data were analyzed by creating tables using SPSS to determine frequencies, averages and percentages. For research questions 1, 2 and 3, a Fisher’s Exact Test (a variant of the chi-square test for independence for small sample sizes) with an alpha level of .05 was used to determine whether there was a relationship between a participant’s age, years of experience, number of schools under the participant’s direct responsibility, number of students for whom the participant had to provide counseling services, the presence of other CSCs in the building and district, and the participant’s responses.

Results

Importance of Supervision

Participants ranked the importance of individual clinical supervision based on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = not important to 6 = extremely important). When the participants’ indications of the top three options were combined, 79% (n = 93) rated the importance of obtaining clinical supervision as important, very important or extremely important, leaving 21% (n = 25) of participants who reported it being somewhat important, minimally important or not important. When asked about the importance of obtaining administrative supervision, 72% (n = 85) rated it as important, very important or extremely important, leaving 28% (n = 33) who reported it being somewhat important, minimally important or not important.

Cross-tabulation tables were conducted for each of the following variables: (a) age, (b) years of experience as a school counselor, (c) number of schools for which the counselor is responsible, (d) number of students for whom the counselor is responsible, (e) other school counselors in the district and (f) other school counselors in the building. A Fisher’s Exact Test with an alpha level of .05 was used to determine whether there was a relationship between these variables and participants’ perceptions of the importance of individual clinical and administrative supervision. These analyses determined that there was no significant relationship between these variables (age, p = .641; years of experience, p = .597; number of schools for which counselor is responsible, p = .516; number of students for whom counselor is responsible, p = .228; other school counselors in district, p = .319; other school counselors in building, p = .382).

Current Experiences with Supervision

When participants described the current supervision they were receiving, 94% (n = 111) stated that they were receiving no individual clinical supervision, and 6% (n = 7) stated that they were receiving individual clinical supervision. Of the participants receiving this type of supervision, one received supervision once a week, three received supervision once a month and three received supervision less than once a month. Ninety-one percent (n = 108) stated that they were not engaging in group supervision and 8% (n = 10) stated that they were, with seven of these respondents stating that they participated in group supervision once a month and three stating that they participated less than once a month. When asked to describe their clinical supervisor, seven stated that the supervisor was a guidance director, two stated that he or she was another school counselor and one stated that he or she was a psychologist.

Of the 14% (n = 17) of respondents who stated that they were receiving individual and/or group supervision, 11 reported that their school system was incurring the cost for supervision, four stated that they were shouldering all the cost themselves and two stated that they and their school system were paying the cost together. Eighty-eight percent (n = 104) indicated that their school district did not provide release time for them to attend supervision; the remaining 12% (n = 14) did receive release time. Eighty-two percent (n = 97) reported that they were not engaging in peer supervision, and 18% (n = 21) were obtaining peer supervision. Of the respondents receiving peer supervision, ten stated that it occurred once a week, one stated that it was every other week, eight stated that it was once a month, and two stated that it was less than once a month. Regarding administrative supervision, 81% (n = 97) stated that they were engaging in it; 19% (n = 21) were not. Sixty-four participants stated that their administrative supervision was conducted by a principal, seven stated that it was a vice principal, seven stated that it was another school counselor, five reported that it was a superintendent, five stated that it was a guidance director, five that stated it was a director of a specific program area (e.g., special education, student services) and three stated that their administrative supervision was conducted by a vice superintendent.

Cross-tabulation tables were conducted for each of the following variables: (a) age, (b) years of experience as a school counselor, (c) number of schools for which the counselor is responsible, (d) number of students for whom the counselor is responsible, (e) other school counselors in the district and (f) other school counselors in the building. A Fisher’s Exact Test with an alpha level of .05 was used to determine whether there was a relationship between these variables and participants’ current experiences with individual and/or group clinical supervision and/or peer supervision. The results indicated that there was a relationship between receiving group supervision and the number of other school counselors in participants’ district (p = .010), and a relationship between participants’ age and current participation in peer supervision (p = .017). All other analyses for these variables determined no significant relationship.

Future Need for Clinical Supervision

Participants ranked their need for future clinical supervision based on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = not important to 6 = extremely important). When the participants’ indications of the top three options were combined, 54% (n = 64) rated the importance of receiving clinical supervision in the future as important, very important or extremely important, leaving 46% (n = 54) who reported it being somewhat important, minimally important or not important. When respondents were asked whom they considered the most desirable person to be their clinical supervisor, 64% (n = 75) indicated another school counselor with specific training in supervision. Eighteen percent stated that the best supervisor would be a professor in counselor education, 6% indicated a mental health counselor, 6% specified a school psychologist, 5% indicated a psychologist, 2% identified a psychiatrist and 1% specified a social worker with a master’s degree.

Cross-tabulation tables were created for each of the independent variables: (a) cultural/racial background, (b) age, (c) years of experience as a school counselor, d) licensure/certification status, e) number of schools for which the counselor is responsible, f) number of students for whom the counselor is responsible, g) other school counselors in the district and h) other school counselors in the building. A Fisher’s Exact Test with an alpha level of .05 was used to determine whether there was a relationship between these variables and participants’ perceptions of their future need for clinical supervision. The results indicated that there was a relationship between participants’ age and their perception of their need for future clinical supervision (p = .016). All other analyses for these variables determined no significant relationship.

Future Training and Education Needs

When asked about the level of perceived importance of training and education regarding supervision theory and clinical supervision skills, when those were provided, participants ranked importance on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = not important to 6 = extremely important). After the participants’ indications of the top three options were combined, 67% (n = 79) rated the importance of receiving future clinical supervision training as important, very important or extremely important, leaving 33% (n = 39) who reported it being somewhat important, minimally important or not important. Of the 118 participants, the majority (n = 90) had access to the state’s video conferencing system. Fifty-three of the participants stated that they had access to Skype or another real-time communication system; therefore, over half of the participants (n = 65) stated that they did not have access. Fifty-three percent (n = 62) of the participants rated receiving supervision training via face-to-face workshop or conference as either very important or extremely important, whereas 32% (n = 27) rated receiving future clinical supervision training via video conferencing or teleconference as very important or extremely important.

Regarding the type of supervision training they wished to receive, 81% (n = 96) of the participants characterized training on developing specific supervision skills and techniques as important, very important or extremely important. When asked about wanting training to be able to assist supervisees in developing a respectful outlook on individual differences, 71% (n = 84) of the participants noted this type of training as either important, very important or extremely important. Regarding developing supervisees’ clinical skill set for counseling others of a different age, ethnicity, race, religion or sexual orientation, 75% (n = 89) of the participants ranked this type of training as either important, very important or extremely important. Seventy-seven percent (n = 91) of the participants ranked the development of supervision skills to assist supervisees in developing independence and self-directedness as important, very important or extremely important.

Comparing 2012 and 2003 Findings

In 2003 the first author completed a study of 267 RCSCs who took the 2003 School Counselor Survey (Duncan, 2003). Nearly 67% of the 2003 participants rated individual clinical supervision as important, very or extremely important; however, 91% stated that they were not receiving individual clinical supervision, and 92% stated they were not receiving group clinical supervision. In the current study, conducted 9 years later, we note an increase in the importance that school counselors place on receiving clinical supervision, but similar low rates of actually receiving clinical supervision. Specifically, in the current study, 79% of participants rated receiving clinical supervision as important, very important or extremely important; however, 94% stated that they were not receiving individual clinical supervision, and 91% stated they were not receiving group clinical supervision. Those receiving group supervision appear to work in settings where they are not the only counselor in their school.

Limitations

This study has three main limitations. First, the sample was obtained from an e-mail list of certified school counselors in one Midwestern state. The ability to generalize the findings to other states may be limited—especially to states that do not have a similar rural nature. Future research that examines all RCSCs would be beneficial. The second limitation of this study is that those who chose to participate may have answered the survey questions differently than members of the population who did not agree to participate might have answered them. The third limitation is due to the survey being a self-report measure, as the participants may have given answers that they believed to be socially desirable. In spite of being informed in advance that their responses would remain anonymous, the participants still may have answered in a way that did not portray their true feelings or knowledge.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the large majority of school counselors surveyed (79%) perceive clinical supervision as important. This number is in stark contrast to the actual number of school counselors receiving supervision, with the overwhelming majority of the participants stating that they are not receiving any individual or group supervision (94% and 91%, respectively). Although these findings confirm the results of previous studies conducted with school counselors that point to a clinical supervision deficit (Borders & Usher, 1992; Page et al., 2001; Roberts & Borders, 1994; Shanks-Pruett, 1991), the extremely low clinical supervision rates from the current study also may be tapping into challenges specific to rural school counselors. It is possible that many practicing rural school counselors have not engaged in supervision since their university training program and feel unequipped to answer questions about its nature or importance, which could potentially have larger implications regarding these counselors’ clinical skill application. Similarly, Spence, Wilson, Kavanagh, Strong, and Worrall (2001) noted that lack of skill application contributed to counselors’ difficulty in obtaining supervision. Compared to results obtained from a 2003 study with this population, although school counselors increasingly perceive clinical supervision as important (79% vs. 67% in the 2003 study), rates of obtaining clinical supervision have not changed substantially in almost 10 years. This may indicate that challenges for rural school counselors persist and that they may be at a disadvantage regarding their clinical skills and professional development.

Even for those few school counselors who reported receiving individual or group clinical supervision, current supervision practices are far from ideal. Of the seven participants who reported currently receiving supervision, four reported receiving it only once a month or less, and over 88% of participants shared that their school will not provide release time for them to pursue supervision. This may imply that school administrators do not understand the importance of clinical supervision. Herlihy et al. (2002) pointed out the erroneous perception that school counselors do not have the same need for clinical supervision as their mental health counterparts as a factor that impedes clinical supervision for school counselors. The possibility also exists that even though school counselors in this study see the need for clinical supervision, they may not be advocating for it. Rural school counselors may have to consider ways to receive clinical supervision in a manner that does not take time away from their duties or occurs outside school time. Although this may place additional strain on school counselors, forgoing clinical supervision altogether may have negative implications for their personal and professional well-being. Crutchfield and Borders (1997) warned that school counselors who do not receive supervisory support may find themselves dealing with increased stress and may feel overworked, burned out and isolated; and the literature clearly points out the benefits of clinical supervision for school counselors, including increased feelings of support, job satisfaction, enhanced skill development and competencies, and greater accountability (Herlihy et al., 2002; Lambie, 2007).

Although the majority of participants (81%) reported receiving administrative supervision, this form of supervision is conducted by noncounselors. This result supports other literature indicating that school counselors typically receive administrative supervision (Herlihy et al., 2002; Page et al., 2001). However, administrative supervision conducted by school personnel who are not trained in counselor supervision or the professional school counselor’s role does not assist school counselors in enhancing clinical skills and does not meet their professional development needs.

More than half of the participants (54%) said that they can see a need for clinical supervision in their future, an increase from 47% in 2003, and the majority of participants would want to receive this clinical supervision from another school counselor. Of extreme importance, is the fact that there is no supervision training in most master’s-level school counseling preparation programs. The majority of school counseling practitioners who might be asked to supervise others (colleagues or counselors-in-training) do not have specialized training to provide this service. Even though 45% of respondents had supervised interns, 85% shared that they had no formal training. Over 67% of school counselors surveyed reported that they desired supervision training, with over half (53%) stating that they would prefer a face-to-face approach. Participants identified the following areas as ones in which they wanted training: gaining specific supervision skills (81%), acquiring skills to assist supervisees in developing individual skills and self-direction (77%), learning how to develop their supervisees’ skills (75%) and developing respect for individual differences (71%).

Implications for School Counselors

Use of technology for supervision delivery is still a relatively new concept for some professionals. Even though the American Counseling Association clearly states in its Code of Ethics (American Counseling Association, 2014) that reviewing supervisee practice, in addition to live observation, can occur through the use of technology, most school counselors have not had an opportunity to utilize technology as an avenue to gain supervision. Technological advances have made supervision delivery more available, and the use of these technologies may ultimately save individuals travel time and money. While the majority of respondents share a preference for supervision in a face-to-face format, school counselors may become more comfortable with electronic formats as they utilize them more often or with further training.

Counselor educators and supervision trainers will need to use creative methods when scheduling supervision training for professional school counselors. Weekend workshops, intensive summer courses and cooperative in-service programs might be used to provide supervision training. Collaborative efforts between university counselor training programs and state school counselor professional organizations could further orchestrate these opportunities. Counselor educators also might advocate to the Counsel for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Education Programs that supervision training be required in master’s-level school counselor training programs. School counselors desiring supervision may need assistance in advocating for these services. Research indicates that engaging school principals in counseling education can result in a deeper understanding and collaboration between the school counselor and the principal (Shoffner & Williamson, 2000). It is essential to help administrators understand the benefits of clinical supervision and make a case for the provision of opportunities for professional development and clinical supervision for rural school counselors, especially as these opportunities may positively impact burnout incidence.

Recommendations for Future Research

The results of this study provide potential directions for future research. Given the limited literature on clinical supervision for rural school counselors, it is important to fully examine any potential factors that may help conceptualize this phenomenon. Following up with a qualitative study would expand on the quantitative findings and provide a richer context for some of the results discussed. This might help identify additional factors of importance specific to rural school counselors.

Replicating the results of the current study with a random sample of rural school counselors who are practicing nationwide might increase the representativeness of the sample. Utilizing a sampling of rural school counselors who are practicing in only one state presents inherent limitations, as the results discussed may be specific to geographic location and may not apply to rural school counselors in other states.

Conclusion

The majority of school counselors in both the 2003 and 2012 studies reported that they perceive clinical supervision as an important element in their continued personal and professional growth. However, these same groups reported that they are not receiving supervision at an individual, group or peer level. The need for the supervision is apparent, but the access to supervision is limited.

This situation calls for collaborative and coordinated action from counselor educators and leaders in the field. Creation of supervision training opportunities for practicing school counselors is warranted. Methods such as the utilization of technology to allow access to supervision for school counselors, especially for those in remote rural areas, are also important elements in the creation of an effective and efficient statewide supervision plan.

Buy-in from school administrators, school officials at the state level, school boards and counselor educators will be an important aspect of the origination of a statewide system. The need for supervision for rural school counselors is supported through these survey results. It will be imperative to create methods for continued evaluation of a statewide supervision plan to show how the ultimate consumers—the students—are benefitting from school counselors who are receiving supervision.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

Agnew, T., Vaught, C. C., Getz, H. G., & Fortune, J. (2000). Peer group clinical supervision program fosters confidence and professionalism. Professional School Counseling, 4, 6–12.

American Counseling Association. (2014). 2014 code of ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Bain, S. F., Rueda, B., Mata-Villarreal, J., & Mundy, M.-A. (2011). Assessing mental health needs of rural schools in South Texas: Counselors’ perspectives. Research in Higher Education Journal, 14, 1–11.

Bardhoshi, G., & Duncan, K. (2009). Rural school principals’ perceptions of the school counselor’s role. The Rural Educator, 30(3), 16–24.

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2009). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Borders, L. D., & Usher, C. H. (1992). Post-degree supervision: Existing and preferred practices. Journal of Counseling & Development, 70, 594–599. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb01667.x

Bradley, L. J., & Ladany, N. (Eds.). (2010). Counselor supervision (4th ed.) Philadelphia, PA: Brunner-Routledge.

Cates, K. A., Gunderson, C., & Keim, M. A. (2012). The ethical frontier: Ethical considerations for frontier counselors. The Professional Counselor, 2, 22–32.

Crutchfield, L. B., & Borders, L. D. (1997). Impact of two clinical peer supervision models on practicing school counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 75, 219–230. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1997.tb02336.x

Culbreth, J. R., Scarborough, J. L., Banks-Johnson, A., & Solomon, S. (2005). Role stress among practicing school counselors. Counselor Education and Supervision, 45, 58–71. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb00130.x

Duncan, K. (2003). Perceptions of the importance and utilization of clinical supervision among certified South Dakota school counselors (Doctoral dissertation). Available from Dissertation Abstracts International. (UMI No. 3100582)

Feldstein, S. B. (2000). The relationship between supervision and burnout in school counselors (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA.

Gysbers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2000). Developing and managing your school guidance program (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Henderson, P., & Gysbers, N. C. (1998). Leading and managing your school guidance program staff: A manual for school administrators and directors of guidance. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Herlihy, B., Gray, N., & McCollum, V. (2002). Legal and ethical issues in school counselor supervision. Professional School Counseling, 6, 55–60.

Lambie, G. W. (2007). The contribution of ego development level to burnout in school counselors: Implications for professional school counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85, 82–88. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00447.x

Lambie, G. W., Ieva, K. P., Mullen, P. R., & Hayes, B. G. (2011). Ego development, ethical decision-making, and ethical and legal knowledge in school counselors. Journal of Adult Development, 18, 50–59. doi:10.1007/s10804-010-9105-8

Luke, M., Ellis, M. V., & Bernard, J. M. (2011). School counselor supervisors’ perceptions of the discrimination model of supervision. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50, 328–343. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2011.tb01919.x

McMahon, M., & Simons, R. (2004). Supervision training for professional counselors: An exploratory study. Counselor Education and Supervision, 43, 301–309. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2004.tb01854.x

Moyer, M. (2011). Effects of non-guidance activities, supervision, and student-to-counselor ratios on school counselor burnout. Journal of School Counseling, 9(5), 1–31.

Page, B. J., Pietrzak, D. R., & Sutton, J. M., Jr. (2001). National survey of school counselor supervision. Counselor Education and Supervision, 41, 142–150. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2001.tb01278.x

Perfect, M. M., & Morris, R. J. (2011). Delivering school-based mental health services by school psychologists: Education, training, and ethical issues. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 1049–1063. doi:10.1002/pits.20612

Peterson, J. S., & Deuschle, C. (2006). A model for supervising school counseling students without teaching experience. Counselor Education and Supervision, 45, 267–281. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2006.tb00003.x

Roberts, E. B., & Borders, L. D. (1994). Supervision of school counselors: Administrative, program and counseling. The School Counselor, 41, 149–157.

Shanks-Pruett, K. (1991). A study of Tennessee public school counselors’ perceptions about school counseling supervision. Dissertation Abstracts International, 53(03), 683A.

Shoffner, M. F., & Williamson, R. D. (2000). Engaging preservice school counselors and principals in dialogue and collaboration. Counselor Education and Supervision, 40, 128–140. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2000.tb01244.x

Spence, S. H., Wilson, J., Kavanagh, D. J., Strong, J., & Worrall, L. (2001). Clinical supervision in four mental health professions: A review of the evidence. Behavior Change, 18, 135–155. doi:10.1375/bech.18.3.135

Sterner, W. R. (2011). What is missing in counseling research? Reporting missing data. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 56–62. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00060.x

Teich, J. L., Robinson, G., & Weist, M. D. (2007). What kinds of mental health services do public schools in the United States provide? Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, Inaugural Issue, 13–22.

Tyson, L. E., Pérusse, R., & Stone, C. B. (2008). Providing culturally responsive supervision. In L. E. Tyson, J. R. Culbreth, & J. A. Harrington (Eds.), Critical incidents in clinical supervision: Addictions, community, and school counseling (pp. 191–197). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). 2010 Census urban and rural classification and urban area criteria. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/geo/reference/ua/urban-rural-2010.html

Walley, C., Grothaus, T., & Craigen, L. (2009). Confusion, crisis, and opportunity: Professional school counselors’ role in responding to student mental health issues. Journal of School Counseling, 7(36), 1–25.

Wood, J. A. V., Miller, T. W., & Hargrove, D. S. (2005). Clinical supervision in rural settings: A telehealth model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36, 173–179. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.36.2.173

Kelly Duncan, NCC, is an associate professor at the University of South Dakota. Kathleen Brown-Rice, NCC, and Gerta Bardhoshi, NCC, are assistant professors at the University of South Dakota. Correspondence can be addressed to Kelly Duncan, Division of Counseling and Psychology in Education, The University of South Dakota, 414 E. Clark Street, Vermillion, SD 57069, Kelly.Duncan@usd.edu.

Dec 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 5

Ian Martin, John Carey

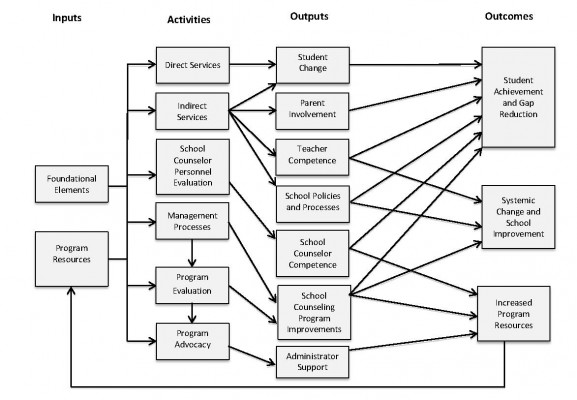

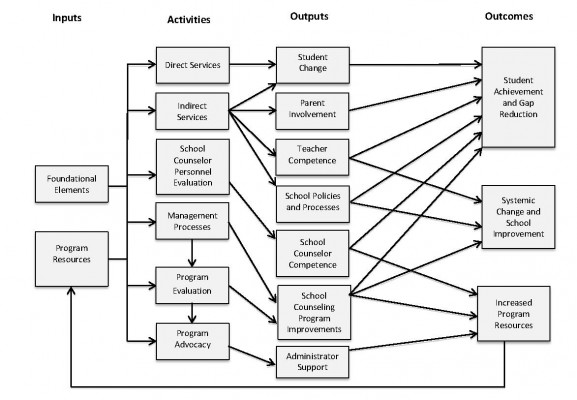

A logic model was developed based on an analysis of the 2012 American School Counselor Association (ASCA) National Model in order to provide direction for program evaluation initiatives. The logic model identified three outcomes (increased student achievement/gap reduction, increased school counseling program resources, and systemic change and school improvement), seven outputs (student change, parent involvement, teacher competence, school policies and processes, competence of the school counselors, improvements in the school counseling program, and administrator support), six major clusters of activities (direct services, indirect services, school counselor personnel evaluation, program management processes, program evaluation processes and program advocacy) and two inputs (foundational elements and program resources). The identification of these logic model components and linkages among these components was used to identify a number of necessary and important evaluation studies of the ASCA National Model.

Keywords: ASCA National Model, school counseling, logic model, program evaluation, evaluation studies

Since its initial publication in 2003, The ASCA National Model: A Framework for School Counseling Programs has had a dramatic impact on the practice of school counseling (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2003). Many states have revised their model of school counseling to make it consistent with this model (Martin, Carey, & DeCoster, 2009), and many schools across the country have implemented 3the ASCA National Model. The ASCA Web site, for example, currently lists over 400 schools from 33 states that have won a Recognized ASCA Model Program (RAMP) award since 2003 as recognition for exemplary implementation of the model (ASCA, 2013).

While the ASCA National Model has had a profound impact on the practice of school counseling, very few studies have been published that evaluate the model itself. Evaluation is necessary to determine if the implementation of the model results in the model’s anticipated benefits and to determine how the model can be improved. The key studies typically cited (see ASCA, 2005) as supporting the effectiveness of the ASCA National Model (e.g., Lapan, Gysbers, & Petroski, 2001; Lapan, Gysbers, & Sun, 1997) were actually conducted before the model was developed and were designed as evaluations of Comprehensive Developmental Guidance, which is an important precursor and component of the ASCA National Model, but not the model itself.

Two recent statewide evaluations of school counseling programs focused on the relationships between the level of implementation of the ASCA National Model and student outcomes. In a statewide evaluation of school counseling programs in Nebraska, Carey, Harrington, Martin, and Hoffman (2012) found that the extent to which a school counseling program had a well-implemented, differentiated delivery system consistent with practices advocated by the ASCA National Model was associated with lower suspension rates, lower discipline incident rates, higher attendance rates, higher math proficiency and higher reading proficiency. These results suggest that model implementation is associated with increased student engagement, fewer disciplinary problems and higher student achievement. In a similar statewide evaluation study in Utah, Carey, Harrington, Martin, and Stevens (2012) found that the extent to which the school counseling program had a programmatic orientation, similar to that advocated in the ASCA National Model, was associated with both higher average ACT scores and a higher number of students taking the ACT. This suggests that model implementation is associated with both increased achievement and a broadening of student interest in college. While these studies suggest that benefits to students are associated with the implementation of the ASCA National Model, additional evaluations are necessary that use stronger (e.g., quasi-experimental and longitudinal) designs and investigate specific components of the model in order to determine their effectiveness or how they can be improved.

There are several possible reasons why the ASCA National Model has not been evaluated extensively. The school counseling field as a whole has struggled with general evaluation issues. For example, questions have been raised regarding the effectiveness of practitioner training in evaluation (Astramovich, Coker, & Hoskins, 2005; Heppner, Kivlighan, & Wampold, 1999; Sexton, Whiston, Bleuer, & Walz, 1997; Trevisan, 2000); practitioners have cited lack of time, evaluation resources and administrative support as major barriers to evaluation (Loesch, 2001; Lusky & Hayes, 2001); and some practitioners have feared that poor evaluation results may negatively impact their program credibility (Isaacs, 2003; Schmidt, 1995). Another contributing factor is that while the importance of evaluation is stressed in the literature, few actual examples of program evaluations and program evaluation results have been published (Astramovich & Coker, 2007; Martin & Carey, 2012; Martin et al., 2009; Trevisan, 2002).

In addition, there are several features of the ASCA National Model that make evaluations difficult. First, the model is complex, containing many components grouped into four interrelated, functional subsystems referred to as the foundation, delivery system, management system and accountability system. Second, ASCA created the National Model by combining elements of existing models that were developed by different individuals and groups. For example, the principle influences of the model (ASCA, 2012) are cited as Gysbers and Henderson (2000), Johnson and Johnson (2001) and Myrick (2003). Furthermore, principles and concepts derived from important movements such as the Transforming School Counseling Initiative (Martin, 2002) and evidence-based school counseling (Dimmitt, Carey, & Hatch, 2007) also were incorporated into the model during its development. While these preexisting models and movements share some common features, they differ in important ways. Elements of these approaches were combined and incorporated into the ASCA National Model without a full integration of their philosophical and theoretical perspectives and principles. Consequently, the ASCA National Model does not reflect a single cohesive approach to program organization and management. Instead, it reflects a collection of presumably effective principles and practices that have been applied in school counseling programs. Third, instruments for measuring important aspects of model implementation are lacking (Clemens, Carey, & Harrington, 2010). Fourth, the theory of action of the ASCA National Model has not been fully explicated, so it is difficult to determine what specific benefits are intended to result from the implementation of specific elements of the model. For example, it is not entirely clear how changing the performance evaluation of counselors is related to the desired benefits of the model.

In this article, the authors present the results of their work in developing a logic model for the ASCA National Model. Logic modeling is a systematic approach to enabling high-quality program evaluation through processes designed to result in pictorial representations of the theory of action of a program (Frechtling, 2007). Logic modeling surfaces and summarizes the explicit and implicit logic of how a program operates to produce its desired benefits and results. By applying logic modeling to an analysis of the ASCA National Model, the authors intended to fully explicate the relationships between structures and activities advocated by the model and their anticipated benefits so that these relationships can be tested in future evaluations of the model.

The purpose of this study, therefore, was to develop a useful logic model that describes the workings of the ASCA National Model in order to promote its evaluation. More specifically, the purpose was to mine the logic elements, program outcomes and implicit (unstated) assumptions about the relationships between program elements and outcomes. In developing this logic model, the authors followed the processes suggested by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation (2004) and Frechtling (2007). Several different frameworks exist for logic models, but the authors elected to use Frechtling’s framework because it focuses specifically on promoting evaluation of an existing program (as opposed to other possible uses such as program planning). This framework identifies the relationships among program inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes. Inputs refer to the resources needed to deliver the program as intended. Activities refer to the actual program components that are expected to be related to a desired outcome. Outputs refer to the immediate products or results of activities that can be observed as evidence that the activity was actually completed. Outcomes refer to the desired benefits of the program that are expected to occur as a consequence of program activities. The authors’ logic model development was guided by four questions:

What are the essential desired outcomes of the ASCA National Model?

What are the essential activities of the ASCA National Model and how do these activities relate to its outputs?

What are the essential outputs of the ASCA National Model and how do these outputs relate to its desired outcomes?

What are the essential inputs of the ASCA National Model and how do these inputs relate to its activities?

Methods

All analyses in this study were based on the latest edition of the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2012). In these analyses, every attempt was made to base inferences on the actual language of the model. In some instances (for example, when it was unclear which outputs were expected to be related to a given activity) the professional literature about the ASCA National Model was consulted.

Because the authors intended to develop a logic model from an existing program blueprint (rather than designing a new program), they began, according to recommended procedures (W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004), by first identifying outcomes and then working backward to identify activities, then outputs associated with activities and finally, inputs.

Identification of Outcomes

The authors independently reviewed the ASCA National Model (2012) and identified all elements in the model. The two authors’ lists of elements (e.g., vision statement, annual agreement with school leaders, indirect service delivery and curriculum results reports) were merged to create a common list of elements. The authors then independently created a series of if, then statements for each element of the model that traced the logical connections explicitly stated in the model (or in rare instances, stated in the professional literature about the model) between the element and a program outcome. In this way, both the desired outcomes of the ASCA National Model and the desired logical linkages between elements and outcomes were identified.

During this process, some ASCA National Model elements were included in the same logic sequence because they were causally related to each other. For example, both the vision statement and the mission statement were included in the same logic sequence because a strong vision statement was described as a necessary prerequisite for the development of a strong mission statement. Some ASCA National Model elements also were included in more than one logical sequence when it was clear that two different outcomes were intended to occur related to the same element. For example, it was evident that closing-the-gap reports were intended to result in intervention improvements, leading to better student outcomes and also to apprising key stakeholders of school counseling program results, in order to increase support and resources for the program.

Identification of Activities

Frechtling (2007) noted that the choice of the right amount of complexity in portraying the activities in a logic model is a critically important factor in a model’s utility. If activities are portrayed in their most differentiated form, the model can be too complex to be useful. If activities are portrayed in their most compact form, the model can lack enough detail to guide evaluation. Therefore, in the present study, the authors decided to construct several different logic models with different sets of activities that ranged from including all the previously identified ASCA National Model elements as activities to including only the four sections of the ASCA National Model (i.e., foundation, management system, delivery system and accountability system) as activities. As neither of the two extreme options proved to be feasible, the authors began clustering ASCA National Model elements and developed six activities, each of which represented a cluster of program elements.

Identification of Outputs Related to Activities

Outputs are the observable immediate products or deliverables of the logic model’s inputs and activities (Frechtling, 2007). After the authors identified an appropriate level for representing model activities, they generated the same level of program outputs. Reexamining the logic sequences, clustering products of identified activities and then creating general output categories from the clustered products accomplished this task. For example, the activity known as direct services contained several ASCA National Model products, such as the curriculum results report, the small-group results report and the closing-the-gap results report (among others), and the resulting output was finally categorized as student change. Ultimately, seven logic model outputs were identified through this process to help describe the outputs created by ASCA National Model activities.

Identifying the Connections Between Outputs and Outcomes

Creating connections between model outputs and outcomes was accomplished by linking the original logic sequences to determine how the ASCA National Model would conceive of outputs as being linked to outcomes. Returning to the above example, the output known as student change, which included such products as results reports, was connected to the outcome known as student achievement and gap reduction in several logic sequences. At the conclusion of this process, each output had straightforward links to one or multiple proposed model outcomes. Not only was this process useful in identifying links between outputs and outcomes, but it also functioned as an opportunity to test the output categories for conceptual clarity.

Identification of Inputs and Connections Between Inputs and Activities

The authors reviewed the ASCA National Model to determine which inputs were necessary to include in the logic model. They identified two essential types of inputs: foundational elements (conceptual underpinnings described in the foundation section of the ASCA National Model) and program resources (described throughout the ASCA National Model). The authors determined that these two types of inputs were necessary for the effective operation of all six activities.

Identifying Other Connections Within the Logic Model

After the inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and the connections between these levels were mapped, the authors again reviewed the logic sequences and the ASCA National Model to determine if any additional linkages needed to be included in the logic model (see Frechtling, 2007). They evaluated the need for within-level linkages (e.g., between two activities) and feedback loops (i.e., where a subsequent component influences the nature of preceding components). The authors determined that two within-level and one recursive linkage were needed.

Results

Outcomes

A total of 65 logic sequences were identified for the ASCA National Model sections: foundation (n = 7), management system (n = 30), delivery system (n = 7) and accountability system (n = 21). Table 1 contains sample logic sequences.

Table 1

Examples of Logic Sequences Relating ASCA National Model Elements to Outcomes

|

National Model

Section

|

Logic Sequence

|

|

|

|

|

| Foundation |

a. If counselors go through the process of creating a set of shared beliefs, then they will establish a level of mutual understanding.b. If counselors establish a level of mutual understanding, then they will be more successful in developing a shared vision for the program.c. If counselors develop a shared vision for the program, then they can develop an effective vision statement.d. If counselors create a vision statement, then they will have the clarity of purpose that is needed to develop a mission statement.e. If counselors create a mission statement, then the program will be more focused.f. If the program is better focused, counselors will create a set of program goals, which will enable counselors to specify how the attainment of the goals should be measured.

g. If counselors specify how the attainment of goals should be measured, then effective program evaluation will be conducted.

h. If effective program evaluation is conducted, then the program will be continuously improved.

i. If the program will be continuously improved, then improved student achievement will result. |

| Management System |

a. If school counselors create annual agreements with the leader in charge of the school, then the goals and activities of the counseling program will be more aligned with the goals of the school.b. If the goals and activities of the counseling program are more aligned with the goals of the school, then school leaders will recognize the value of the school counseling program.c. If school leaders recognize the value of the school counseling program, then they will commit resources to support the program. |

| Delivery System |

a. If school counselors engage in indirect services (e.g., consultation and advocacy), then school policies and processes will improve.b. If school policies and processes improve, then teachers will develop more competency, and systemic change and school improvement will occur. |

| Accountability System |

a. If counselors complete curriculum results reports, then they will have the information they need to demonstrate the effectiveness of developmental and preventative curricular activities.b. If counselors have the information they need to demonstrate the effectiveness of developmental and preventative curricular activities, then they can communicate their impact to school leaders.c. If school leaders are aware of the impact of developmental and preventative curricular activities, then they will recognize their value.d. If school leaders recognize the value of developmental and preventative curricular activities, then they will commit resources to support them. |

Forty of these logic sequences terminated with an outcome related to increased student achievement or (relatedly) to a reduction in the achievement gap. Twenty-two sequences terminated with an outcome related to an increase in program resources. Only three sequences terminated with an outcome related to systemic change in the school. From this analysis, the authors concluded that the primary desired outcomes of the ASCA National Model are increased student achievement/gap reduction and increased school counseling program resources. They also concluded that systemic change and school improvement is another desired outcome of the ASCA National Model.

Activities

Based on a clustering of ASCA National Model elements identified previously, six activities were developed for the logic model. These activities included the following: direct services, indirect services, school counselor personnel evaluation, program management processes, program evaluation processes and program advocacy processes. Each of these activities represents a cluster of elements within the ASCA National Model. For example, the activity known as direct services includes the school counseling core curriculum, individual student planning and responsive services. Consequently, the direct services activity represents the spectrum of services that would be delivered to students in an ASCA National Model school counseling program.

Activities Related to Outputs

Based on the clustering of the ASCA National Model products or deliverables around the related logic model activities, seven outputs were identified. These outputs included the following: student change, parent involvement, teacher competence, school policies and processes, school counselor competence, school counseling program improvements, and administrator support. The outputs represent all of the ASCA National Model products generated by model activities and help to collect evidence and determine to what degree an activity was successfully accomplished. In essence, for evaluation purposes, these outputs represent the intermediate outcomes (Dimmitt et al., 2007) of an ASCA National Model program. Activities should result in measurable changes in outputs, which in turn should result in measurable changes in outcomes. For example, the output known as student change reflects student changes such as increased academic motivation, increased problem-solving skills, enhanced emotional regulation and better interpersonal problem-solving skills; these changes lead to the longer-term outcome of student achievement and gap reduction.

Connections Between Outputs and Outcomes

Connecting the seven ASCA National Model outputs to its outcomes strengthens the logic model by identifying the hypothesized relationships between the more immediate changes that result from school counseling program activities (i.e., outputs) and the more distal changes that result from the operation of the program (i.e., outcomes). As described earlier, two primary outcomes (student achievement and gap reduction and increased program resources) and one secondary outcome (systemic change and school improvement) were identified within the ASCA National Model. Three of the seven outputs (student change, parent involvement and administrator support) were connected to only one outcome. Three other outputs (teacher competence, school policies and processes, and school counselor competence) were connected to two outcomes. One output (administrator support) was connected to all three outcomes. Interpreting these linkages is useful in understanding the implicit theory of change of the ASCA National Model and consequently in designing appropriate evaluation studies. The authors’ logic model, for example, indicates that student changes (related to both direct and indirect services of an ASCA National Model program) are expected to result in measurable increases in student achievement and a reduction in the achievement gap.

It also is helpful to scan backward in the logic model to identify how changes in outcomes are expected to occur. For example, student achievement and gap reduction is linked to six model outputs (student change, parent involvement, teacher competence, school policies and processes, school counselor competence, and school counseling program improvements). Student achievement and gap reduction is multiply determined and is the major focus of the ASCA National Model. Increased program resources are connected to three model outputs (school counselor competence, school counseling program improvements and administrator support). Systemic change and school improvement also can be connected to three outputs (teacher competence, school policies and processes, and school counseling program improvements).

Inputs and Connections Between Inputs and Activities

Based on an analysis of the ASCA National Model, two inputs were identified for inclusion in the logic model: foundational elements (which include the elements in the ASCA National Model’s foundation section considered important for program planning and operation) and program resources (which include elements essential for effective program implementation such as counselor caseload, counselor expertise, counselor professional development support, counselor time-use and program budget). Both of these inputs were identified as being important in the delivery of all six activities.

Additional Connections Within the Logic Model

Based on a final review of the logical sequences and another review of the ASCA National Model, three additional linkages were added to the authors’ logic model. The first linkage was a unidirectional arrow leading from management processes to program evaluation in the activities column. This arrow was intended to represent the tight connection between management processes and evaluation activities that is evident in the ASCA National Model. Relatedly, a unidirectional arrow leading from the school counseling program evaluation activity to the program advocacy activity was added. This arrow was intended to represent the many instances of the ASCA National Model suggesting that program evaluation activities should be used to generate essential information for program advocacy. The final additional link was a recursive arrow leading from the increased program resources outcome to the program resources input. This linkage was intended to represent the ASCA National Model’s concept that investment of additional resources resulting from successful implementation and operation of an ASCA National Model program will result in even higher levels of program effectiveness and eventually even better outcomes.

The Logic Model

Figure 1 contains the final logic model for the ASCA National Model for School Counseling Programs. Logic models portray the implicit theory of change underlying a program and consequently facilitate the evaluation of the program (Frechtling, 2007). Overall, the theory of change for an ASCA national program could be described as follows: If school counselors use the foundational elements of the ASCA National Model and have sufficient program resources, they will be able to develop and implement a comprehensive program characterized by activities related to direct services, indirect services, school counselor personnel evaluation, management processes, program evaluation and (relatedly) program advocacy. If these activities are put in place, several outputs will be observed, including the following: student changes in academic behavior, increased parent involvement, increases in teacher competence in working with students, better school policies and processes, increased competence of the school counselors themselves, demonstrable improvements in the school counseling program, and increased administrator support for the school counseling program. If these outputs occur, then the following outcomes should result: increased student achievement and a related reduction in the achievement gap, notable systemic improvement in the school in which the program is being implemented, and increased program support and resources. If these additional resources are reinvested in the school counseling program, the effectiveness of the program will increase.

Figure 1. Logic Model for ASCA National Model for School Counseling Programs

Discussion

Logic models can be used for a number of purposes including the following: enhancing communication among program team members, managing the program, documenting how the program is intended to operate and developing an approach to evaluation and related evaluation questions (Frechtling, 2007). The present study was conducted in order to develop a logic model for ASCA National Model programs so that these programs could be more readily evaluated, and based on the results of these evaluations, the ASCA National Model could then be improved.

Evaluations can focus on the question of whether or not a program or components of a program actually result in intended changes. At the most global level, an evaluation can focus on discovering the extent to which the program as a whole achieves its desired outcomes. At a more detailed level, an evaluation can focus on discovering the extent to which the components (i.e., activities) of the program achieve their desired outputs (with the assumption that achievement of the outputs is a necessary precursor to achievement of the outcomes).

In both types of evaluations, it is important to use a design that allows some form of comparison. In the simplest case, it would be possible to compare outputs and outcomes before and after implementation of the ASCA National Model. In more complex cases, it would be possible to compare outputs and outcomes of programs that have implemented the ASCA National Model with programs that have not. In these cases, it is essential to control for the confounding effects of extraneous variables (e.g., the affluence of students in the school) by the use of matching or covariates. If the level of implementation of the ASCA National Model program as a whole can be measured, it is even possible to use multivariate correlation approaches to examine whether the level of implementation of the program is related to desired outcomes while simultaneously controlling statistically for potential confounding variables. These same correlational procedures can be used to examine the relationships between the more discrete activities of the program and their corresponding outputs.

At the most global level, it is important to evaluate the extent to which the implementation of the ASCA National Model results in the following: increases in student achievement (and associated reductions in the achievement gap), measurable systemic change and school improvements, and increases in resources for the school counseling program. At present, there is some evidence that implementation of the ASCA National Model is related to achievement gains (Carey, Harrington, Martin, & Hoffman, 2012; Carey, Harrington, Martin, & Stevens, 2012). No evaluations to date have examined whether ASCA National Model implementation results in systemic change and school improvement or in an increase in program resources.

It also is important to evaluate the extent to which specific program activities achieve their desired outputs. Table 2 contains a list of sample evaluation questions for each activity. Within these questions, evaluation is focused on whether or not components of the program result in overall benefits. No evaluation study to date has evaluated the impact of ASCA National Model implementation on these factors.

Table 2

Sample Evaluation Questions for ASCA National Model Activities

|

Activities

|

Evaluation Questions

|

|

|

|

|

| Direct Services |

Does organizing and delivering school counseling direct services in accordance with ASCA National Model principles result in an increase in important aspects of students’ school behavior that are related to academic achievement? |

| Indirect Services |

Does organizing and delivering school counseling indirect services in accordance with ASCA National Model principles result in an increase in parent involvement? |

| Does organizing and delivering school counseling indirect services in accordance with ASCA National Model principles result in an increase in teachers’ abilities to work effectively with students? |

| Does organizing and delivering school counseling indirect services in accordance with ASCA National Model principles result in improvements in school policies and procedures that support student achievement? |

| School Counselor Personnel Evaluation |

Does the implementation of personnel and processes recommended by the ASCA National Model result in increases in the professional competence of school counselors? |

| Management Processes |

Does the implementation of the management processes recommended by the ASCA National Model result in demonstrable improvements in the school counseling program? |

| Program Evaluation |

Does the implementation of program evaluation processes recommended by the ASCA National Model result in demonstrable improvements in the school counseling program? |

| Program Advocacy |

Does the implementation of the program advocacy practices recommended by the ASCA National Model result in increases in administrator support for the program? |

In addition to examining program-related change, it is important to evaluate whether a basic assumption of the ASCA National Model bears out in reality. The major assumption is that school counselors who use the foundational elements of the ASCA National Model (e.g., vision statement, mission statement) and have access to typical levels of program resources can develop and implement all the activities associated with an ASCA National Model program (e.g., direct services, indirect services, school counselor personnel evaluation, management processes, program evaluation and program advocacy). Qualitative evaluations of the relationships between inputs and quality of the activities are necessary to determine what levels of inputs are necessary for full implementation. While full evaluation studies of this type have yet to be undertaken, Martin and Carey (2012) have recently reported the results of a two-state qualitative comparison of how statewide capacity-building activities to promote school counselors’ competence in evaluation were used to promote the widespread implementation of ASCA National Model school counseling programs. More studies of this type that focus on the relationships between a broader range of program inputs and school counselors’ ability to fully implement ASCA National Model program activities are needed.

Limitations and Future Directions

Constructing a logic model retrospectively is inherently challenging and complex. This is especially true when the program for which the logic model is being created was not initially developed with reference to an explicit, coherent theory of action. In the present study, the authors approached the work systematically and are confident that others following similar procedures would generate similar results. With that said, a limitation of this work is that the logic model was created based on the authors’ analyses of the written description of the ASCA National Model (2012) and literature surrounding the ASCA National Model. Engaging individuals who were involved in the development and implementation of the ASCA National Model in dialogue might have resulted in a richer logic model with even more utility in directing evaluation of the ASCA National Model. As a follow-up to the present study, the authors intend to continue this inquiry by asking key individuals involved with the ASCA National Model to evaluate the present logic model and to suggest revisions and extensions. Even given this limitation, the current study has potential immediate implications for improving practice that go beyond its role in providing focus and direction for ASCA National Model evaluation.