Oct 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 4

Laura Shannonhouse, Jane E. Myers

As the world grows more connected, the counseling profession has developed a significant focus on multicultural concerns and internationalization (the incorporation of international perspectives), but the extent of this phenomenon is currently unknown. The current pilot study established baseline data concerning how counselor education programs encouraged and supported international opportunities for students and faculty. Representatives from 62 of the 215 (as of spring 2011) programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs completed a survey describing their institutions’ and departments’ commitment to incorporating student and faculty international activities into their counselor preparation programs, and the nature of such activities in faculty involvement and counselor training. Two primary themes emerged from the data: (1) a disconnect between commitment to and execution of international activities, and (2) a one-sided approach to internationalization and cultural exchanges. Implications for research and counselor preparation are considered.

Keywords: internationalization, counselor preparation, cultural exchanges, baseline data, international activities

Heppner, Leong, and Chiao (2008), writing from the perspective of counseling psychology, observed that increased global dialogue and the incorporation of international perspectives has resulted in a shift toward viewing the counseling profession as part of a larger global movement. In the introduction to a special issue of the Journal of Counseling & Development focused on counseling around the world, Hohenshil (2010) asserted that the growth of this movement is “one of the major and most exciting emerging trends in the counseling profession” (p. 3). The importance of this trend was underscored by Leung et al. (2009), who provided an extensive rationale for and discussion of internationalization in counseling. However, Leung et al. (2009), along with other authors, notably Pedersen (2003), Leong and Ponterotto (2003), and Heppner (2006), noted that internationalization is still a fresh concept and that understanding and implementing it is a work in progress.

Ng and Noonan (2012) asserted that internationalization is “a multidimensional movement in which professionals across nations collaborate through equal partnerships to advance the practice of counseling as a worldwide profession” (p.11). These collaborations will likely include many who identify as professional counselors, but must be inclusive so as to encourage contributions from those of other identities and traditions who promote mental health, wellness and development from different, though compatible, perspectives. In order to foster such collaborations, Leung et al. (2009) have advocated for “the nurturance of a global perspective in counseling scholarship, through our teaching, research, and service” (p. 112). Numerous authors have promoted such a perspective through articles that focus on the nature of counseling in various countries (e.g., Remley, Bacchini, & Krieg, 2010; See & Ng, 2010; Stockton, Nitza, & Bhusumane, 2010), those that explore counseling-oriented topics across borders (e.g., Chung, 2005; Furbish, 2007) and several that describe the challenges that international students face in Euro-American counseling training and supervision (e.g., Crockett & Hays, 2011; Yakunina, Weigold, & McCarthy, 2010).

The global aspects of counseling, teaching and service also are central to research that explains and analyzes the involvement of extended cultural immersion experiences in counselor education programs (e.g., Alexander, Kruzek, & Ponterotto, 2005; Canfield, Low, & Hovestadt, 2009; Ishii, Gilbride, & Stensrud, 2009; Shannonhouse & West-Olatunji, 2013; Tomlinson-Clarke & Clarke, 2010). Throughout this cultural immersion literature, a primary emphasis is the use of cultural exchanges as an avenue toward increasing multicultural counseling competence. If it is true that international experiences promote multicultural counseling competence, as suggested by Alexander et al. (2005), Shannonhouse and West-Olatunji (2013) and Tomlinson-Clarke and Clarke (2010), inclusion of such experiences as part of counselor training seems important. Though Shannonhouse (2013) provided a current review of the literature regarding the relationship of cultural immersion to multicultural counseling competence, a solid understanding of the extent of international cultural immersion across programs is not currently available. Although several authors have described the nature and measure of international involvement among counseling psychology faculty and students (see Gerstein, Heppner, Ægisdóttir, Leung & Norsworthy, 2009), the literature lacks information concerning the involvement of counselor educators and counselor education programs with the international counseling community.

The present pilot study was undertaken to obtain baseline data on the amount of counselor preparation program involvement beyond U.S. borders. The authors’ intent was to determine the extent to which counselor education programs incorporate (and are committed to) international and cultural immersion activities as part of faculty involvement and counselor training. The authors proposed the following research questions: How many counselor education programs have a departmental commitment to international activities? To what extent do faculty and students participate in international activities? What kinds of activities are included?

Method

Through a multi-step revision process, the authors drafted a survey to examine the nature of international activities in faculty involvement and counselor training. First, two counselor educators not involved with the study who had expertise in international activities reviewed an outline of the study design, research questions and draft survey questions. The authors then revised the survey per the feedback they received, and subsequently field-tested it with one counselor educator and two doctoral students with prior counseling experience outside the United States. Based upon their feedback, the draft survey underwent wording, content and structural changes, which resulted in the final instrument used in this study. The authors presented the final version of the survey to an Institutional Review Board and it received approval for use as intended.

Eight quantitative survey items assessed demographic characteristics of each respondent (e.g., gender, ethnicity) and his or her counselor education program (e.g., Association for Counselor Education and Supervision [ACES] region, program tracks). Twenty additional questions assessed the nature of international experiences for both faculty (Table 2) and students (Table 3), and the extent of program and institutional support (incorporated throughout Tables 2 and 3). Participants provided comments in relation to several questions to expand upon their initial responses.

The authors sent a link to the online Qualtrics survey along with information about the study via e-mail to the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) coordinators of all (as of spring 2011) 215 CACREP-accredited programs. The e-mail included a request to forward the link to another faculty member if the coordinator thought that person would be better suited to complete the survey. It is unknown how many program coordinators or other faculty completed the survey; however, 66 counselor educators initiated responses, with 62 completing the full survey. While the initial response rate was 31%, the survey completion rate was 29%. The number of responses to individual items varied from 59–62. The sample size was insufficient to make valid within- and between-groups comparisons.

Participants and Program Information

The counselor educators who completed the survey included 24 males (41%) and 35 females (59%). Most were Caucasian (n = 55, 90%). Two were African American (3%), one each identified as Asian American or Latino (2%), and two indicated “other.” The authors asked participants how many study-abroad, immersion or international travel experiences they had taken part in as either a participant or facilitator. Equal numbers of respondents reported either none or more than four (n = 13, 21% in each group), and one participant noted having more than 25 such experiences. Slightly fewer respondents reported one international experience (n = 11, 18%), and six (10%) reported two such experiences.

Program-level information that the respondents provided is included in Table 1. As one can see from this table, more than one-third of the respondents were from the Southern Region (37.7%), slightly more than one-quarter were from the North Central Region (27.9%), and substantially fewer were from the North Atlantic, Rocky Mountain or Western Regions. This distribution of respondents approximates the ACES regional membership, which includes regional percentages of 41.3% Southern, 26.4% North Central, 17.3% North Atlantic, 8.7% Western and 6.3% Rocky Mountain. All the programs that the respondents represented offered a master’s degree and 34% offered a doctoral degree. Accredited program tracks varied, with most programs offering clinical mental health or community counseling tracks (90.3%) and school counseling tracks (74.1%). Though there was no place for respondents to indicate the student enrollment of their programs, the average full-time equivalent (FTE) faculty size was 7.2 persons, with only 12% of programs having 12 or more faculty.

Table 1

Program-Level Information on Respondents

|

Program Information

|

N

|

%

|

| ACES region |

|

|

|

Southern |

23

|

37.7

|

|

North Central |

17

|

27.9

|

|

North Atlantic |

14

|

23.0

|

|

Rocky Mountain |

2

|

3.3

|

|

Western |

5

|

8.2

|

|

|

|

|

| Degree programs offered |

|

|

|

Master’s |

62

|

100.0

|

|

Specialist |

15

|

24.0

|

|

Doctorate |

21

|

34.0

|

|

|

|

|

| Accredited program tracks offered |

|

|

|

Addiction counseling |

0

|

0.0

|

|

Career counseling |

3

|

4.8

|

|

Clinical mental health counseling/community counseling |

56

|

90.3

|

|

Marriage, couple and family counseling |

7

|

11.3

|

|

School counseling |

46

|

74.1

|

|

Student affairs and college counseling |

10

|

16.1

|

|

Other |

13

|

21.0

|

|

|

|

|

Results

Responses to the core survey items offered insight into the specific nature of international activities in counselor preparation programs and how much support and structure the programs devoted to these activities. The authors examined these activities separately for both counselor educators and counselor trainees, with a majority of the responses summarized for each individual question in Table 2 (faculty activities) and Table 3 (student activities). For each of these two populations, the results characterized the nature and type of the international activities, how they were incorporated into expected practices, how they were financially supported, and what role international partners had in those activities.

Faculty Involvement in International Activities

The authors asked several questions to determine the level and type of program support for international activities of faculty. Responses are summarized in Table 2. Among the counselor education programs that the respondents represented, most (87.1%) did not incorporate international activities as a regular and expected endeavor for faculty. However, in most programs (82.2%), the institutional mission statement or philosophy supported or advocated for such involvement. The authors consistently found that a structured international component was lacking in over three-fourths of programs (77.4%).

Table 2

Program Support for and Faculty Involvement in International Activities

|

Item

|

Response

|

N

|

%

|

| Does your program incorporate international activities as a regular and expected activity for faculty? |

Yes |

8

|

12.9

|

| No |

54

|

87.1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Does the philosophy of your institution (mission statement) support/advocate for international programs and activities? |

Yes |

51

|

82.2

|

| No |

10

|

16.1

|

| Missing |

1

|

1.6

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Does your program have a structured (organized) international component? |

Yes |

14

|

22.6

|

| No |

8

|

77.4

|

| Missing |

1

|

1.6

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Is there departmental support for this international component? |

Yes |

13

|

21.0

|

| No |

1

|

1.6

|

| Missing |

48

|

77.4

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Does your program have partner schools outside the United States? |

Yes |

17

|

27.4

|

| No |

45

|

73.6

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Do faculty regularly visit partner schools/agencies? |

Yes |

15

|

24.1

|

| No |

2

|

3.2

|

|

|

Missing |

45

|

73.6

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Is there faculty exchange with partner schools/agencies? |

Yes |

9

|

14.5

|

| No |

8

|

12.9

|

|

|

Missing |

45

|

73.6

|

|

|

|

|

|

| During the past 3 years, have any of your program faculty participated in international activities? |

Yes |

52

|

83.9

|

| No |

10

|

16.1

|

| During the past 3 years, in which of the following international activities have your faculty participated (check all that apply)? |

Attendance at conferences outside the United States |

35

|

56.5

|

| Presentations at conferences outside the United States |

35

|

56.5

|

| Joint research with faculty outside the United States |

23

|

37.1

|

| Study-abroad tours conducted individually or through American Counseling Association (ACA), Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development (AMCD) or other organizations |

19

|

30.1

|

|

Worked as a counselor or counselor educator outside the United States |

18

|

29.0

|

|

International faculty exchange |

6

|

9.7

|

|

Fulbright Scholar |

8

|

12.9

|

|

Other |

9

|

14.5

|

|

|

|

|

|

Item

|

Response

|

M

|

SD

|

| The financial contributions toward faculty participation in international activities include the following (scale of 0–100%): |

Faculty member |

30.75

|

38.38

|

| Department |

24.88

|

34.99

|

| University |

36.75

|

37.55

|

|

Professional organizations |

7.63

|

21.57

|

Most respondents (83.9%) reported that faculty had participated in international activities within the past 3 years. International activities of faculty included attendance and presentations at conferences outside the United States (56.5% each), joint research with faculty outside the United States (37.1%), and study-abroad tours (30.1%). Relatively few respondents reported international faculty exchange (9.7%) and Fulbright Scholars (12.9%).

Financial support for faculty international activities was reported to come from the faculty member or university in almost equal proportions, with a lower level of financial support from departments and extremely little from professional associations. The authors asked respondents to report relative percentage contributions from each of those four sources. As shown in Table 2, the standard deviations of responses to all four categories were relatively large, in all cases exceeding the absolute value of the mean. In short, there was a significant amount of variability in response to the question concerning sources of financial support for international activities of faculty.

Not shown in Table 2 are responses concerning departmental support for international programs, as most counselor educators who completed the survey did not respond to this question. Among the 14 who did respond, 13 (93% of those responding) indicated that there was departmental support for international activities, through either curricular focus or financial commitments. Over one-quarter of respondents (27.4%) reported that their program had a partner school outside the United States, and nearly all (88.2%) of those respondents reported that faculty regularly visited the partner school. Roughly one-half (52.9%) of respondents from programs with such international partnerships noted that they had reciprocal faculty exchanges with their partners.

Student Involvement in International Activities

Survey responses to questions concerning student involvement in international activities are summarized in Table 3. Slightly over one-fourth of the programs that respondents represented (29%) incorporated international activities as part of counselor training. Responses were split 50/50 on the question of whether students were actively encouraged to be involved in international activities outside the counselor education program. Respondents from only two programs (3.2%) noted that participation in international activities was required for graduation. Almost one-quarter of respondents represented programs (24.1%) that provided academic credit to students for participating in international activities. When programs did offer academic credit, it was more often for an elective course than a required one, though five respondents (8.1%) did note that their programs required the international course.

Table 3

Program Support for Student Involvement in International Activities

|

Item

|

Response

|

N

|

%

|

|

|

|

|

| Does your program incorporate international activities as part of counselor training for students? |

Yes |

18

|

29.0

|

| No |

44

|

71.0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Do students regularly visit partner schools/agencies? |

Yes |

9

|

14.5

|

| No |

8

|

12.9

|

| Missing |

45

|

73.6

|

|

|

|

|

| Is there student exchange with partner schools/agencies? |

Yes |

6

|

9.6

|

| No |

1

|

17.7

|

| Missing |

45

|

73.6

|

|

|

|

|

| Are students actively encouraged to be involved in international activities outside your program (e.g., international activities sponsored by other schools/organizations like AMCD or Association for Counselor Education and Supervision [ACES])? |

Yes |

31

|

50.0

|

| No |

31

|

50.0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Is participation in these international activities required for students to graduate? |

Yes |

2

|

3.2

|

| No |

16

|

25.8

|

| Missing |

44

|

71.0

|

|

|

|

|

| Can students receive academic credit for participating in these international activities? |

Yes |

15

|

24.1

|

| No |

3

|

4.8

|

| Missing |

44

|

71.0

|

|

|

|

|

| The academic credit offered for international activities is best described as: |

A required course |

5

|

8.1

|

| An elective course |

7

|

11.2

|

| A required or elective course |

1

|

1.6

|

|

Other |

1

|

1.6

|

|

Missing |

48

|

77.4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

M

|

SD

|

| The financial contributions toward student participation in international activities include the following (scale of 0 to 100%): |

Student |

73.41

|

28.91

|

| Department |

14.12

|

25.07

|

|

University |

11.35

|

18.13

|

|

Professional organizations |

1.12

|

3.16

|

Financial support for student participation in international activities was apparently limited. Again, participants responded to this question based on the percentage of funding provided by each of the four sources. Three-quarters of funding came directly from students themselves. Departments provided some support (M = 14.12, SD = 25.07), with some coming from the universities (M = 11.35, SD = 18.13), while support from professional associations was almost nonexistent (M = 1.12, SD = 3.16). As was true of faculty financial support, there was significant variability in responses to this question except in regard to support provided by professional associations.

Not shown in Table 3 are responses from the 17 respondents who reported their programs having partner schools. Among those respondents, 53% reported that students regularly visited the partner programs. Only 35% engaged in reciprocal student exchange with partner schools.

Discussion

Despite the respondents’ reports of strong departmental and institutional commitments to internationalization from CACREP-accredited counselor education programs, the responses of 62 faculty members suggest that these programs have a relatively low level of actual involvement in international activities. However, over the past 3 years a significant number of individual faculty members have participated in international activities of their own accord. Attending and presenting at international conferences have been the primary faculty activities, with few engaging in faculty exchange or Fulbright scholarships. This finding contrasts with reports from counseling psychologists, for whom Fulbrights and faculty exchanges have been more frequent (Heppner et al., 2008).

Funding for international involvement differs considerably for faculty and students. Although faculty contribute more than one-third of the costs for their international involvement, they are much more likely than students to obtain support from their department and university. Professional associations are also slightly more likely to provide financial support for faculty than for students. If students are to engage in international activities, some consideration of financial support seems imperative.

Among programs that have partner schools, faculty and to a lesser extent students regularly visit their partners. However, faculty and student exchanges from international partners to American CACREP programs are not nearly as prevalent. From the current findings, it appears that internationalization occurs primarily in one direction, which validates several conclusions from Gerstein and Ægisdóttir’s (2007) comprehensive review of the literature. The reasons for such a one-sided approach to internationalization are likely complex, and at this stage are still unknown. It could be that U.S. counselor education programs either do not encourage or may actually discourage international visitors or enrollment of international students. If that is the case, determining and addressing underlying reasons, such as language or logistical barriers, is an important next step. If other factors are involved, learning what those are could be a step toward reducing barriers and increasing more equal international exchanges.

Though structured (and reciprocal) international activities are not the norm across programs represented in this survey, two stand out as particularly interesting examples with regard to the effects of internationalization on counselor trainee development and on the logistical realities of implementing two-way internationalization. While at the University of Florida, Dr. Cirecie A. West-Olatunji organized two month-long immersions to South Africa and Botswana (see Shannonhouse & West-Olatunji, 2009, for a program summary). These events were optional for participating students, who received no course credit and some financial support for participation. However, they were effective at enhancing multicultural awareness (Shannonhouse & West-Olatunji, 2013; West-Olatunji, Templeton, Goodman, & Mehta, 2011), and were structured in such a way as to validate and allow the students to learn from the natural helpers and para-professionals in southern Africa. Meanwhile, Dr. Suhyun Suh at Auburn University has developed an ongoing reciprocal international exchange between Auburn and Korean counseling students (for more information, see http://education.auburn.edu/academic_departments/serc/outreach/south-korea.html). This activity is provided at reduced cost to students by leveraging university funds (Auburn students pay the equivalent of 5 credit hours for 3 hours of credit plus a week of immersion), and it involves exchanging students and faculty from both institutions for coursework in addition to cultural immersion (Suh, Hansing, Booker, & Radomski, 2013).

While the results of this study were designed to serve as a baseline of internationalization in counselor education and not a compendium of current activities, the authors choose to showcase the initiatives of these two programs in order to facilitate dialogue. The first provides a peer-reviewed look at the benefits of internationalization and serves as a reminder of why the counseling profession has joined other disciplines in welcoming globalization: much can be learned from those who help in different places and different ways. The second serves as a model for how a counseling program can implement a reciprocal exchange that is structured into the curriculum and financially supported by funding sources invested in diversity. Both programs are built upon the premise that internationalization is multidirectional, in that all those working toward wellness across the globe have valuable perspectives from which others may learn, in an effort to better advance human dignity.

Implications

The current findings raise a number of questions concerning student and faculty participation in international counseling activities. For example, what are the reasons underlying faculty choices for international involvement? What inhibits involvement? Are language barriers or a lack of contacts, resources or finances the strongest deterrents? Though financial realities may prevent many international faculty and students from visiting U.S. counseling programs and thereby encourage one-way internationalization, is the exchange between U.S. counseling programs and their counterparts in wealthier nations also one-sided? How can reciprocal international cooperation and involvement increase? Larger systemic issues such as political pressures or economic strain may have an important effect on some of these unanswered questions, and future researchers should consider them.

Limitations

Whether the respondents adequately represented all accredited programs is impossible to determine. It is likely that some CACREP liaisons were faculty with international experiences while others were not. Though the authors asked that those in the latter group forward the survey link to a faculty member with more relevant experience, the number of participants who did so is unknown. In each case, the respondent provided program-level information rather than reporting as an individual. It is probable that even in the programs for which respondents reported high levels of international involvement, the respondents simply may not have known about some relevant faculty activities. It is also likely that respondents representing programs with international involvement were among those most inclined to respond to the survey. Overall, the results were limited by the response rate and respondents’ knowledge of program faculty activities. While one must interpret the results with caution due to these limitations, these findings did provide the beginnings of a baseline to determine counselor education program involvement in international activities, which offers an important first step for future systematic efforts (e.g., Shannonhouse, 2013) to contextualize the internationalization of the counseling profession.

Conclusion

As the counseling profession continues to internationalize, it will be necessary for counselor education programs to provide training for both students and faculty to increase cross-cultural awareness and sensitivity. Institutional support will be essential in terms of both mission and financial resources for both students and faculty. Beyond the institution, faculty may require training and encouragement to undertake international activities beyond conference attendance. While international presentations and partner school visits are impressive for faculty vitae and university reports, true internationalization is a two-way process. The authors challenge counselor educators to find ways to extend a welcome to international visitors, which will result in increasing numbers of faculty and student exchanges, and equalize the balance of trade relative to the internationalization of the counseling profession.

References

Alexander, C. M., Kruzek, T., & Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Building multicultural competencies in school counselor trainees: An international immersion experience. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44, 255–266. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb01754.x

Canfield, B. S., Low, L., & Hovestadt, A. (2009). Cultural immersion as a learning method for expanding intercultural competencies. The Family Journal, 17, 318–322. doi:10.1177/1066480709347359

Chung, R. C. Y. (2005). Women, human rights, and counseling: Crossing international boundaries. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83, 262–268. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00341.x

Crockett, S. A., & Hays, D. G. (2011). Understanding and responding to the career counseling needs of international college students on U.S. campuses. Journal of College Counseling, 14, 65–79. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1882.2011.tb00064.x

Furbish, D. S. (2007). Career counseling in New Zealand. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85, 115–119. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00453.x

Gerstein, L. H., & Ægisdóttir, S. (2007). Training international social change agents: Transcending a U.S. counseling paradigm. Counselor Education and Supervision, 47, 123–139. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2007.tb00043.x

Gerstein, L. H., Heppner, P. P., Ægisdóttir, S., Leung, S.-M. A., & Norsworthy, K. L. (Eds.). (2009). International handbook of cross-cultural counseling: Cultural assumptions and practices worldwide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Heppner, P. P. (2006). The benefits and challenges of becoming cross-culturally competent counseling psychologists. The Counseling Psychologist, 34, 147–172. doi:10.1177/0011000005282832

Heppner, P. P., Leong, F. T. L., & Chiao, H. (2008). A growing internationalization of counseling psychology. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of counseling psychology (4th ed., pp. 68–85). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

Hohenshil, T. H. (2010). International counseling introduction. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 3. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00140.x

Ishii, H., Gilbride, D. D., & Stensrud, R. (2009). Students’ internal reactions to a one-week cultural immersion trip: A qualitative analysis of student journals. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 37, 15–27. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2009.tb00088.x

Leung, S.-M. A., Clawson, T., Norsworthy, K. L., Tena, A., Szilagyi, A., & Rogers, J. (2009). Internationalization of the counseling profession: An indigenous perspective. In L. H. Gerstein, P. P. Heppner, S.-M. A. Leung, & K. L. Norsworthy (Eds.), International handbook of cross-cultural counseling (pp. 111–124). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Leong, F. T. L., & Ponterotto, J. G. (2003). A proposal for internationalizing counseling psychology in the United States: Rationale, recommendations, and challenges. The Counseling Psychologist, 31, 381–395. doi:10.1177/0011000003031004001

Ng, K.-M., & Noonan, B. M. (2012). Internationalization of the counseling profession: Meaning, scope, and concerns. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling, 34, 5–18. doi:10.1007/s10447-011-9144-2

Pedersen, P. B. (2003). Culturally biased assumptions in counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 31, 396–403. doi:10.1177/0011000003031004002

Remley, T. P., Jr., Bacchini, E., & Krieg, P. (2010). Counseling in Italy. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 28–32. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00146.x

See, C. M. & Ng, K.-M. (2010). Counseling in Malaysia: History, current status, and future trends. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 18–22. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00144.x

Shannonhouse, L. (2013). The relationships between multicultural counseling competence, cultural immersion, & cognitive/emotional developmental styles: Implications for multicultural counseling training (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/listing.aspx?styp=ti&id=10151

Shannonhouse, L. R., & West-Olatunji, C. A. (2009, December). AMCD, ACES outreach tour a success. Counseling Today, 52(6), 100–101.

Shannonhouse, L., & West-Olatunji, C. (2013, Winter). One counselor-trainee’s journey toward multicultural counseling competence: The role of mentoring in executing intentional cultural immersion Professional Issues in Counseling. Retrieved from http://www.shsu.edu/~piic/documents/OneCounselorTrainee%E2%80%99sJourneyTowardMulticulturalCounselingCompetence.pdf

Suh, S., Hansing, K., Booker, S., & Radomski, J. (2013, October). Experiential learning abroad: Process and outcomes. Poster session presented at the meeting of the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision, Denver, CO.

Stockton, R., Nitza, A., & Bhusumane, D.-B. (2010). The development of professional counseling in Botswana. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 9–12. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00142.x

Tomlinson-Clarke, S. M., & Clarke, D. (2010). Culturally focused community-centered service learning: An international cultural immersion experience. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 38, 166–175. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2010.tb00124.x

West-Olatunji, C., Templeton, L., Goodman, R. D., & Mehta, S. (2011). Creating cultural competence: An outreach immersion experience in southern Africa. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 33, 335–346. doi:10.1007/s10447-011-9138-0

Yakunina, E. S., Weigold, I. K., & McCarthy, A. S. (2010). Group counseling with international students: Practical, ethical, and cultural considerations. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 25, 67–78. doi:10.1080/87568225.2011.532672

Laura Shannonhouse, NCC, is an assistant professor at the University of Maine. Jane E. Myers, NCC, NCGC, is a professor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Correspondence can be addressed to Laura Shannonhouse, 5766 Shibles Hall, Orono, ME 04469, laura.shannonhouse@maine.edu.

Oct 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 4

See Ching Mey, Melissa Ng Lee Yen Abdullah, Chuah Joe Yin

Research universities in Malaysia are striving to transform into world-class institutions. These universities have the capacity to attract the best students to achieve excellence in education and research. It is important to monitor the psychological well-being of students during the transformation process so that proactive intervention can help students cope with the learning and research demands. This study profiled and monitored the personality traits of postgraduate and undergraduate students in a selected Malaysian research university using a quantitative research method. The researchers profiled personality traits using an online assessment, the Behavioral Management Information System (BeMIS), and tracked real and preferred personality traits and positive changes during rapid institutional transition.

Keywords: personality traits, BeMIS, undergraduate students, research universities, psychological well-being

Malaysia is advancing toward a knowledge-based economy and relies heavily on its universities to educate and train the much-needed human capital for the country (Fernandez, 2010). Research universities have the capacity to attract the best students and have the autonomy to select students who excel in education and research. Various measures are being implemented to transform universities into world-class institutions (Wan, 2008). The institutional transformation at Malaysian universities focuses on critical areas such as governance, leadership, academia, teaching and learning, as well as research and development (Ministry of Higher Education, 2011). Educational institutions must monitor the psychological profile and well-being of their students, especially those who are potentially at risk of mental health issues such as anxiety and depression, as well as substance abuse, in order to promote optimum human capital development (Wynaden, Wichmann, & Murray, 2013). Moreover, during the institutional transformation process, all levels of the university community, including students, may experience changes driven by higher standards and demands in teaching and learning as well as research performance (Schraeder, Swamidass, & Morrison, 2006) that might result in stress (Becker et al., 2004; Gladstone & Reynolds, 1997; Smollan & Sayers, 2009). Certain personality traits may build the community’s resilience in coping with psychological stress (Lievens, Ones, & Dilchert, 2009; Nelson, Cooper, & Jackson, 1995). A detailed personality profile of university students can help research institutions put in place necessary support systems to strengthen students’ well-being during institutional transformation.

The Impact of Institutional Transformation

Institutional transformation at research universities in Malaysia can result in stress, anxiety and uncertainty for students at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Successful coping with new demands is integral to the process of transformation. Failure to cope with stressors may lead to fatigue and depressive mood. Such physical and psychological symptoms may impair daily living, work and school performance, and learning ability (Goretti, Portaccio, Zipoli, Razzolini, & Amato, 2010; See, Abdullah, Teoh, & Yaacob, 2011). Organizational change may affect personality changes in students and impact academic performance (Horng, Hu, Hong, & Lin, 2011; Nelson et al., 1995; Oreg & Sverdlik, 2011; See et al., 2011). Ongoing research including profiling and monitoring the personality traits and psychosocial behavior of students can assist students in adapting successfully (Marshall, 2010). Counselors and psychologists at the university can help students develop positive coping strategies during stressful transitional periods.

Personality Characteristics

Connor-Smith and Flachsbart (2007) have defined personality as characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings and behaviors over time and across situations. Some theorists have described coping as a process of the personality responding to stress (Connor-Smith & Flachsbart, 2007). For example, individuals with the personality trait of extraversion may seek social support during life crisis, while someone with the trait of neuroticism may respond with avoidance or denial. Thus, personality traits may influence university students’ responses and coping skills in stressful situations. Individuals with an extraverted personality tend toward optimistic assessment of accessible coping resources and react less intensely to stress, while those with a neurotic personality often experience high rates of stress and intense emotional and physiological reactivity to stress (Connor-Smith & Flachsbart, 2007). Personality predispositions can predict an individual’s ability to adapt to change. Resilient traits enable stress management in reaction to institutional transformation (Nelson et al., 1995; Oreg, Vakola, & Armenakis, 2011; See et al., 2011). The goal of this study was to analyze the personality profile of undergraduate and postgraduate students at a research university in Malaysia during institutional transformation, and to propose proactive interventions to help the student community cope with change.

Overview of the Study

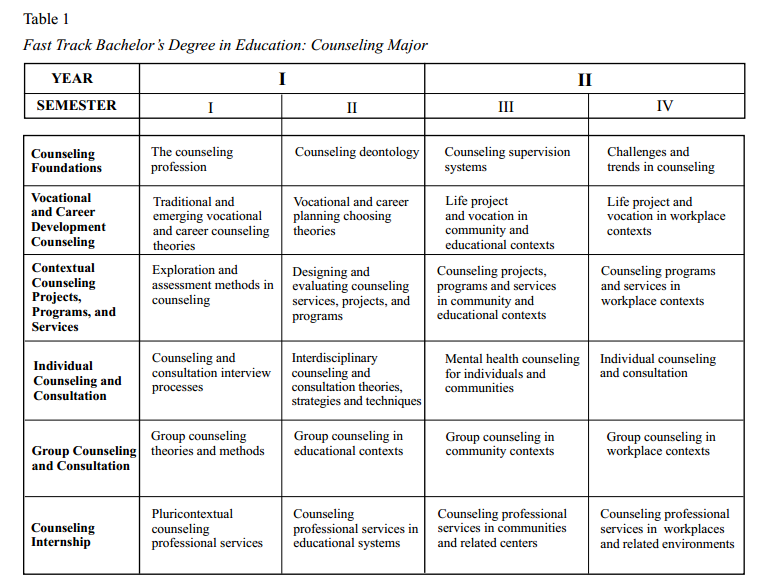

The selected research university in this study was awarded the status of Accelerated Program for Excellence (APEX) in 2008, making it the first and only APEX university in Malaysia. APEX is a fast-track development program that aims to enable a selected university to transform and seek world-class status (Razak, 2009). The APEX program has been identified as a critical initiative to increase the level of excellence of higher education in Malaysia (Razak, 2009). An APEX university has the autonomy to select students based on academic merit and other criteria that the university deems essential. For this study, the researchers randomly selected from among postgraduate and undergraduate students who had volunteered to participate, and used the Behavioral Management Information System (BeMIS) to investigate the students’ personality profile and well-being. The research objectives included the following: (a) profile the real and preferred personality traits of the university students during institutional transformation, and (b) explore personality changes over different phases during the university’s transitional period.

Participants and Design

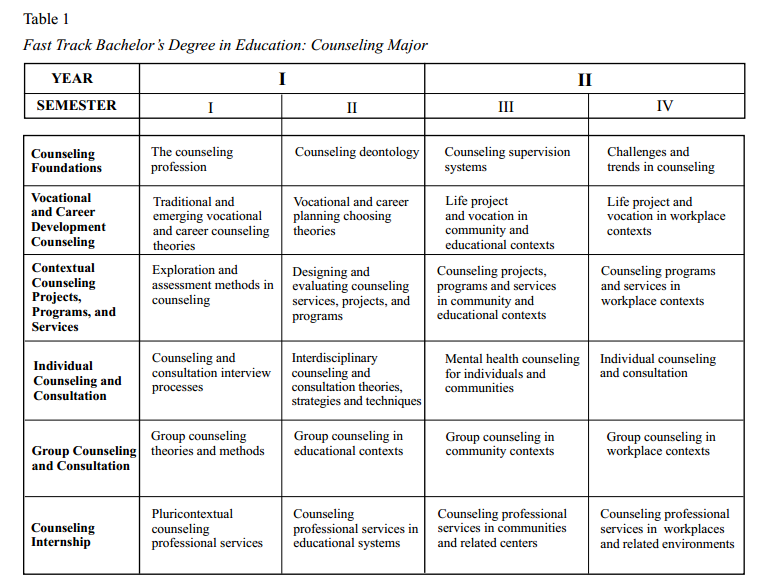

This longitudinal study gathered data relating to personality traits and psychosocial behaviors of postgraduate and undergraduate students over three phases. Seventy-eight students (34 undergraduate students and 44 postgraduate students) participated in phase 1; 142 students (80 undergraduate students and 62 postgraduate students) participated in phase 2; and 169 students (72 undergraduate students and 97 postgraduate students) participated in phase 3.

Instrument

The BeMIS is an online assessment and reporting tool used to measure personality. The BeMIS was developed using the Adjective Check List (ACL), a standardized personality trait measure comprised of 300 adjectives commonly used to describe personality traits (Gough & Heilbrun, 1983). The ACL is capable of effectively measuring 37 personality traits under five main categories of traits: (a) responsiveness, (b) psychological needs, (c) specific responses, (d) interpersonal behavior and (e) cognitive orientation (Gough & Heilbrun, n.d.; Center for Credentialing and Education, 2009). The 37 personality traits are enthusiasm, optimism, negativity, communality, achievement, dominance, endurance, order, exhibition, psychologically perceptive, nurturance, affiliation, social energy, autonomy, aggression, change, support seeking, self-blaming, deference, counseling readiness, self-control, self-confidence, personal adjustment, self-satisfaction, creativity, structure valuing, masculinity, femininity, fault finding, respectful, work centered, playful, security seeking, affected, intellectualistic, pragmatic and scientific. The behavior for each scale is presented in percentile ranks, and grouped into real and preferred personality traits. The real-self personality traits are the existing traits, and the preferred-self traits are the desired traits. The mean for each measured behavior is 50, with a standard deviation of 10. On average, scores range between 40 and 60. A score of 60 is considered high and indicates a strong expression of the trait. A score of less than 40 is considered low and suggests suppression of the trait. Any extreme score (exceeding 70 or less than 30) may reveal stress and dissatisfaction with life (Gough & Heilbrun, n.d.). The BeMIS was translated into Bahasa Malaysia and the reliability of the Bahasa Malaysia version was tested (See et al., 2011). The reliability and validity of the BeMIS and ACL have been adequately substantiated (See et al., 2011; Center for Credentialing and Education, 2009; Gough & Heilbrun, n.d.).

Procedure

The researchers conducted the first phase of the study 1 year after the start of the university transformation process. They carried out phase 2 of the study 18 months after the university embarked on the transformation agenda, and carried out the third phase two and a half years after the start of the transformation process. The researchers sent questionnaires to all 26 schools in the university, requesting for each school to randomly select five postgraduate students and five undergraduate students to participate in the study. Participants were required to respond to BeMIS twice during each phase. The first time participants chose adjectives that they thought described them as they really were, while the second time they chose adjectives that they would prefer to describe them. In addition to the questionnaire, participants received a participant information and consent form that served to protect the confidentiality of student information.

Results

Postgraduate Students’ Personality Profile

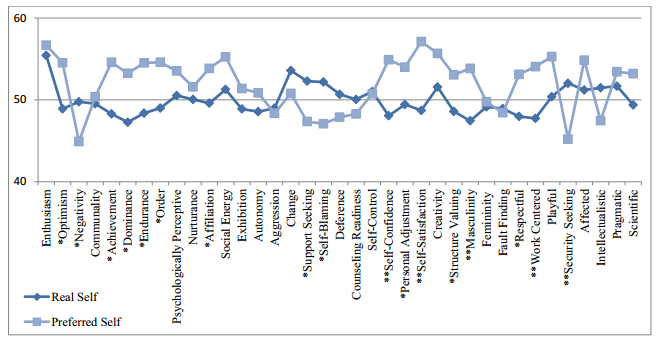

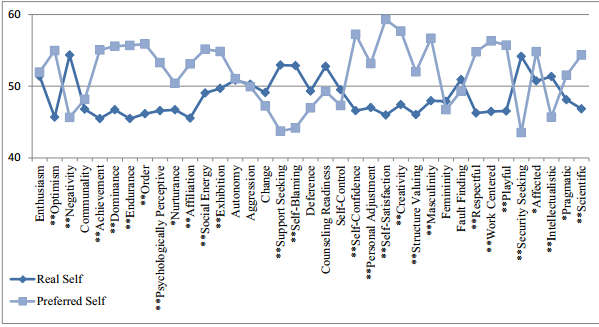

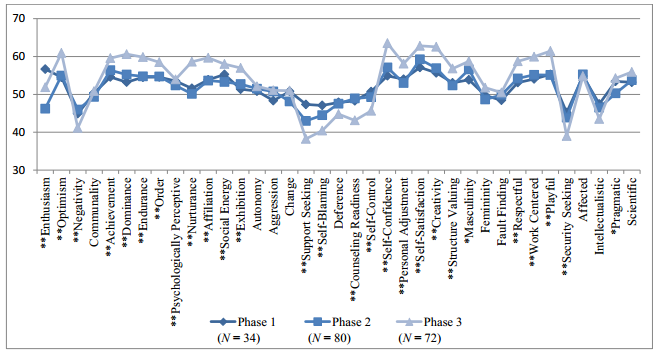

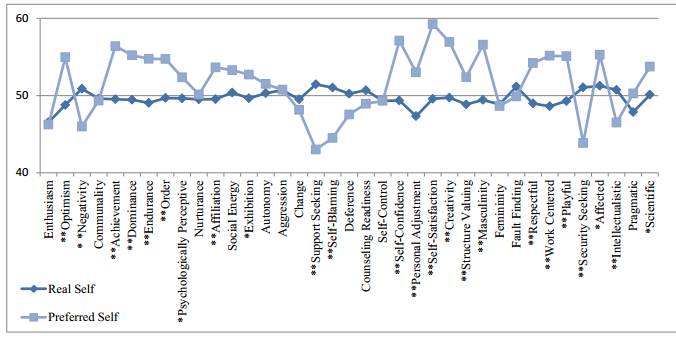

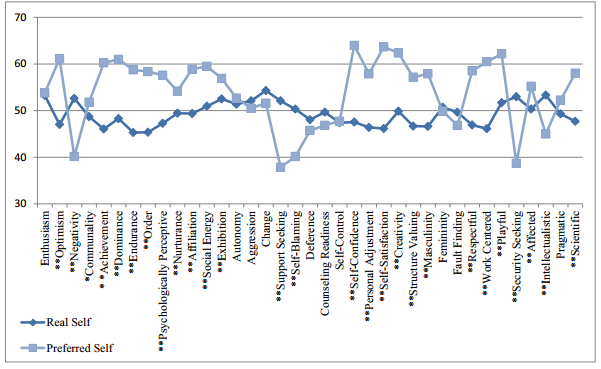

Figure 1 shows the real-self and the preferred-self traits of the postgraduate students in phase 1 of the study. The postgraduate students did not indicate any extreme low scores (less than 30) or extreme high scores (more than 70) during this phase of the study. The researchers performed a t test, and found significant differences (p < 0.05) in 17 of the 37 traits between the real self and the preferred self of postgraduate students. Among these 17 traits, four traits were significantly higher in the real self, compared to the preferred self: negativity, support seeking, self-blaming and security seeking. In contrast, 13 traits were significantly higher in the preferred self than the real self (optimism, achievement, dominance, endurance, order, affiliation, self-confidence, personal adjustment, self-satisfaction, structure valuing, masculinity, respectful and work centered), indicating that the postgraduate students desired to be stronger in these traits.

Figure 1. Postgraduate students’ personality traits (real/preferred) in phase 1.* p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

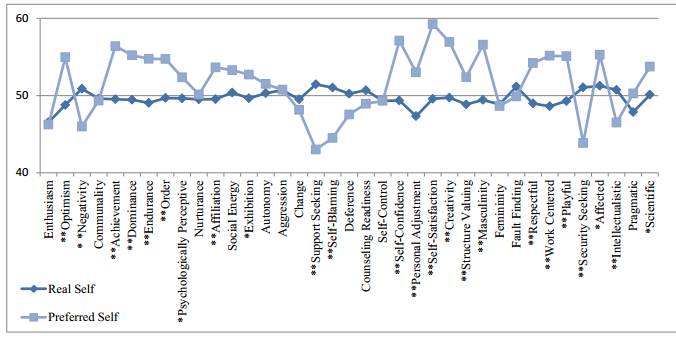

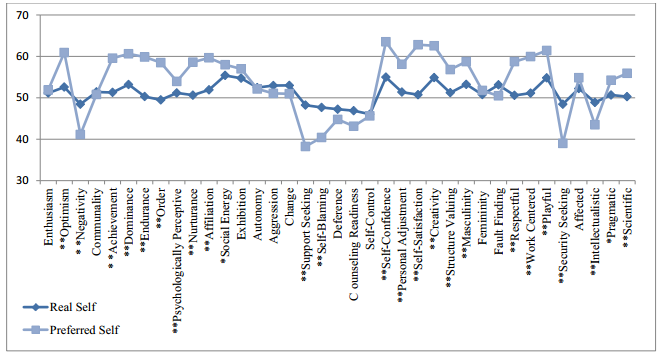

The real-self and the preferred-self traits of the postgraduate students in phase 2 of the study appear in Figure 2. The postgraduate students did not indicate any extreme low scores (less than 30) or extreme high scores (more than 70) during this phase of the study. The researchers found 24 traits to be significantly different (p < 0.05) between the real self and the preferred self of postgraduate students. Among the 24 traits, the researchers found five traits to be significantly higher in the real self than the preferred self: negativity, support seeking, self-blaming, security seeking and intellectualistic. The researchers found 19 of the 24 traits to be significantly higher in the preferred self than the real self (optimistic, achievement, dominance, endurance, order, psychologically perceptive, affiliation, exhibition, self-confidence, personal adjustment, self-satisfaction, creativity, structure valuing, masculinity, respectful, work centered, playful, affected, and scientific), indicating that the postgraduate students desired to be stronger in these traits.

Figure 2. Postgraduate students’ personality traits (real/preferred) in phase 2. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

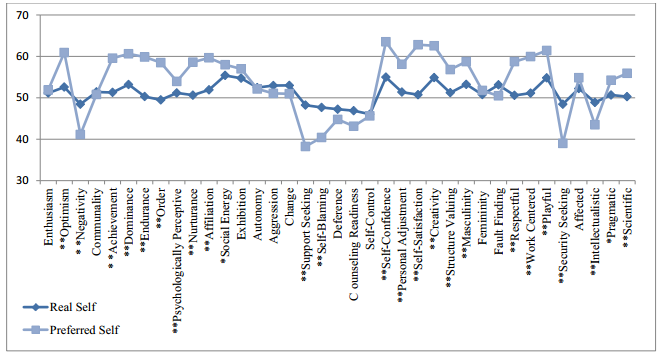

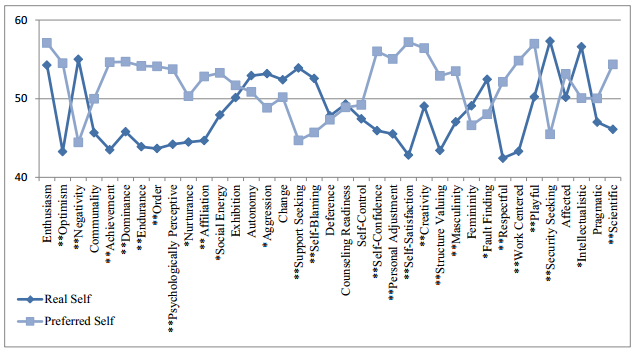

In phase 3, as revealed in Figure 3, the institutional transformation produced strong preferred-self traits (scores of more than 60), including optimism, self-satisfaction, creativity, playful, self-confidence and dominance. The postgraduate students indicated scores below 40 for two preferred-self traits—support seeking and security seeking—indicating a suppression of the traits. The postgraduate students did not indicate any extreme low scores (less than 30) or extreme high scores (more than 70) for either the real-self or the preferred-self traits in phase 3. The incongruence between the real-self and the preferred-self traits was most exaggerated in phase 3 (Figure 3), in which the researchers found 25 traits to be significantly different (p < 0.05). The five traits found to be significantly higher in the real self were the same as in phase 2 (negativity, support seeking, self-blaming, security seeking and intellectualistic). The 20 traits found to be significantly higher in the preferred self were similar to the ones in phase 2 (optimistic, achievement, dominance, endurance, order, psychologically perceptive, affiliation, exhibition, self-confidence, personal adjustment, self-satisfaction, creativity, structure valuing, masculinity, respectful, work centered, playful, affected and scientific), with the addition of the nurturance trait.

Figure 3. Postgraduate students’ personality traits (real/preferred) in phase 3. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

Undergraduate Students’ Personality Profile

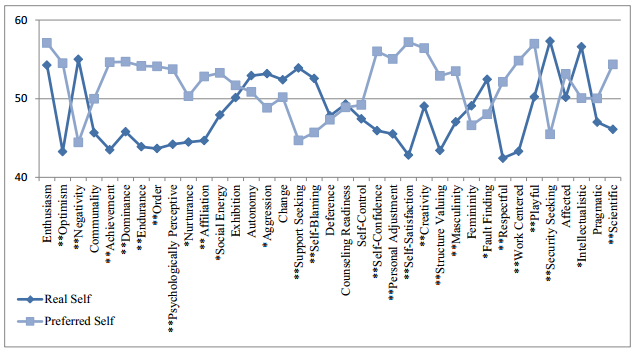

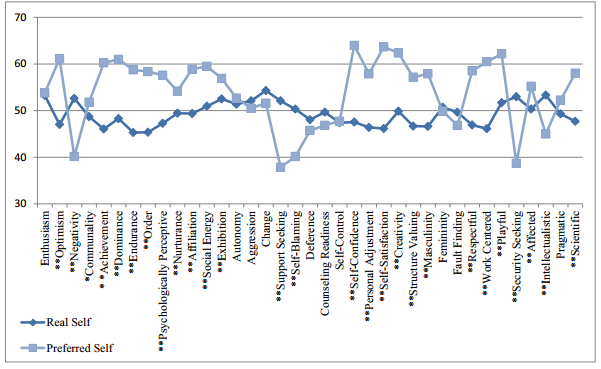

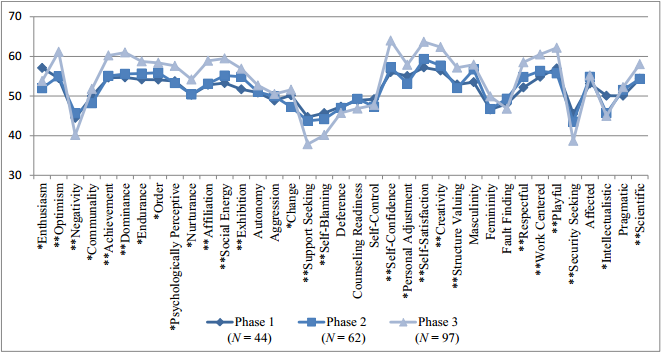

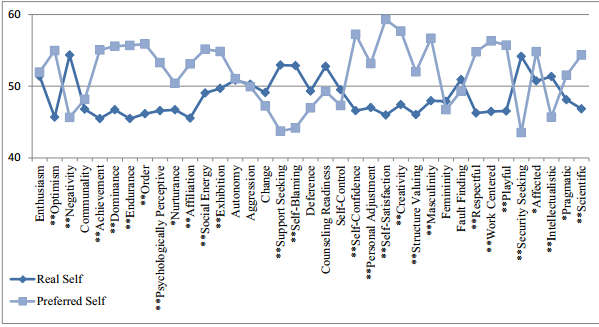

The real-self and the preferred-self traits of undergraduate students in phase 1 of the study appear in Figure 4. The undergraduate students did not indicate any extreme low scores (less than 30) or extreme high scores (more than 70) during the first phase of the study. The researchers performed a t test on the real-self and the preferred-self traits of the undergraduate students and found significant differences (p < 0.05). In phase 1, 26 traits of the real self and the preferred self of the undergraduate students had significant differences. Six traits—negativity, support seeking, self-blaming, fault finding, security seeking and intellectualistic—were found to be significantly higher in the real self compared to the preferred self. The other 20 traits were significantly higher in the preferred self than the real self, indicating that the undergraduate students desired to be stronger in the following 20 traits: optimistic, achievement, dominance, endurance, order, psychologically perceptive, nurturance, affiliation, social energy, aggression, self-confidence, personal adjustment, self-satisfaction, creativity, structure valuing, masculinity, respectful, work centered, playful and scientific.

Figure 4. Undergraduate students’ personality traits (real/preferred) in phase 1. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

Figure 5 shows the real-self and the preferred-self personality traits of the undergraduate students in phase 2. The undergraduate students did not indicate any extreme low scores (less than 30) or extreme high scores (more than 70) in phase 2. In this phase, the researchers found 27 traits to be significantly different (p < 0.05) between the real self and the preferred self. Five of the 27 traits (negativity, support seeking, self-blaming, security seeking and intellectualistic) were found to be significantly higher in the real self than the preferred self. The following 22 of the 27 traits were found to be significantly higher in the preferred self than the real self: optimistic, achievement, dominance, endurance, order, psychologically perceptive, nurturance, affiliation, social energy, exhibition, self-confidence, personal adjustment, self-satisfaction, creativity, structure valuing, masculinity, respectful, work centered, playful, affected, pragmatic and scientific.

Figure 5. Undergraduate students’ personality traits (real/preferred) in phase 2. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

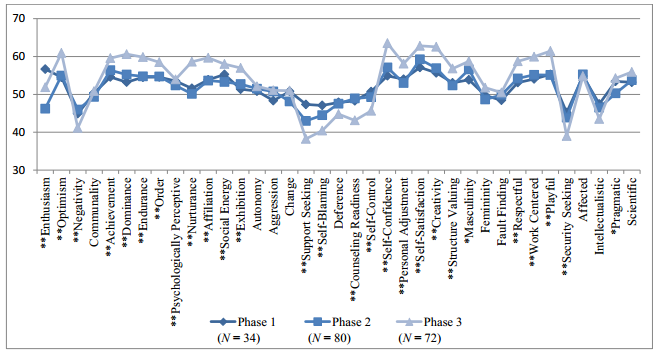

As found in the real self and the preferred self of the postgraduate students, the incongruence in personality traits of the undergraduate students was most obvious in phase 3. Figure 6 exhibits eight strong preferred-self traits (scores of more than 60) including optimism, achievement, dominance, self-confidence, self-satisfaction, creativity, work centered and playful. In contrast, the undergraduate students indicated scores below 40 for two preferred-self traits—support seeking and security seeking—indicating a suppression of the traits. The undergraduate students did not indicate any extreme low scores (less than 30) or extreme high scores (more than 70) in either the real-self or the preferred-self traits in phase 3. The researchers found 26 traits to be significantly different (p < 0.05). The five traits that were found to be significantly higher in the real self were the same as in phase 2 (negativity, support seeking, self-blaming, security seeking and intellectualistic). Twenty-one traits were found to be significantly higher in the preferred self: optimistic, achievement, dominance, endurance, order, psychologically perceptive, nurturance, affiliation, social energy, exhibition, self-confidence, personal adjustment, self-satisfaction, creativity, structure valuing, masculinity, respectful, work centered, playful, affected and scientific.

Figure 6. Undergraduate students’ personality traits (real/preferred) in phase 3. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

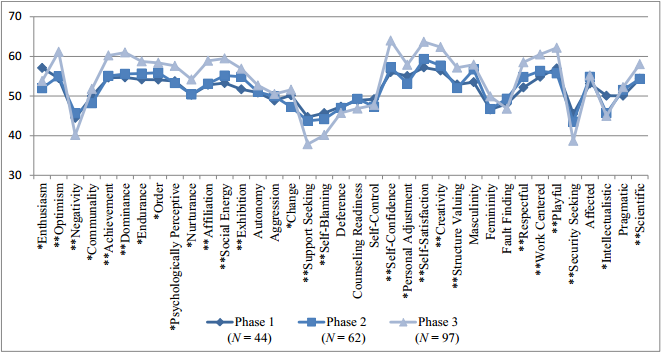

Personality Changes over Phases of the Transitional Period

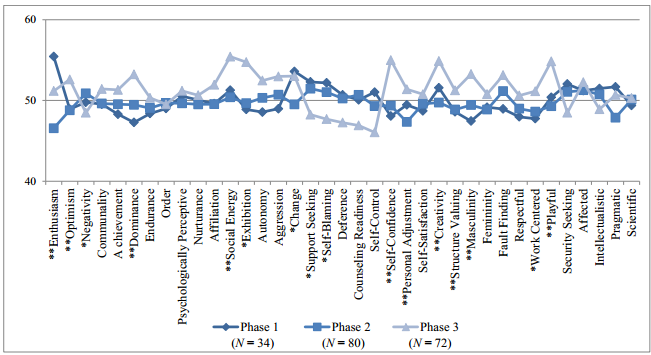

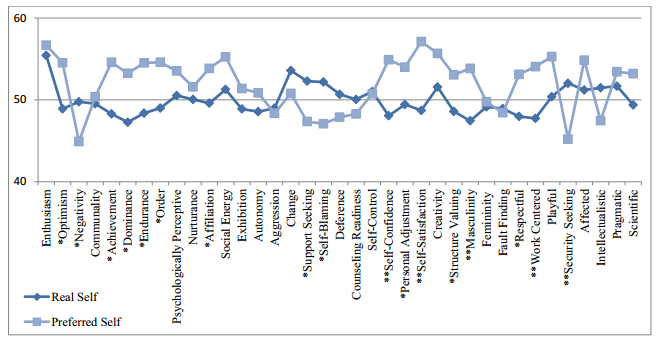

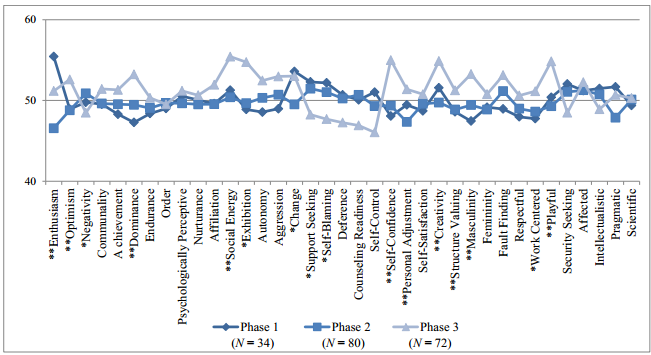

Real-self personality traits. Postgraduate and undergraduate students did not exhibit extreme real-self personality traits (scores of less than 30 or more than 70) throughout the process of the university’s transformation. The researchers performed nonparametric tests to examine changes within the real-self traits of the postgraduate and undergraduate students throughout the three phases of the study (see Figures 8 and 9). As shown in Figures 7 and 8, the researchers found more significant changes within the real-self traits of the postgraduate students compared to those of the undergraduate students. Sixteen real-self traits of the postgraduate students experienced significant changes over the three phases. Among the 16 real-self traits, eight traits (optimism, dominance, social energy, exhibition, self-confidence, structure valuing, masculinity and work centered) increased significantly over the three phases, while two traits (support seeking and self-blaming) decreased significantly over the three phases. Five traits decreased in phase 2, but increased significantly again in phase 3: enthusiasm, change, personal adjustment, creativity and playful. The negativity trait increased during phase 2 but decreased in phase 3. Despite the significant fluctuation of the postgraduate students’ traits, in general, positive traits increased while negative traits decreased. Conversely, the real-self traits of undergraduate students appeared more stable compared to the real-self traits of the postgraduate students (Figure 8). Four real-self traits of undergraduate students experienced significant changes: nurturance, affiliation, playful and intellectualistic. The nurturance and affiliation traits increased significantly over the three phases, whereas the playful and intellectualistic traits decreased significantly during phase 2, but increased again in phase 3.

Figure 7. Changes in postgraduate students’ real-self personality traits across phases 1, 2 and 3.* p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

Figure 8. Changes in undergraduate students’ real-self personality traits across phases 1, 2 and 3.* p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

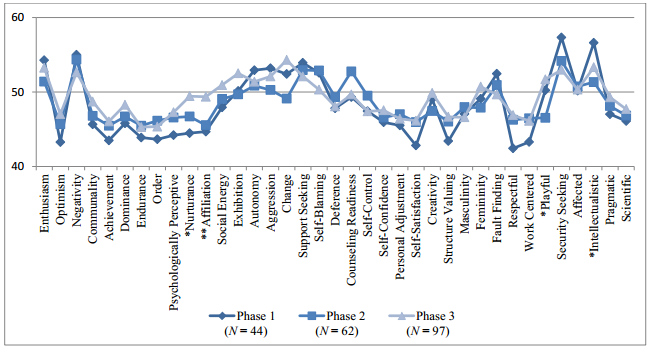

Preferred-self personality traits. As seen in Figures 9 and 10, the preferred-self personality traits of postgraduate and undergraduate students did not fluctuate radically throughout the three phases of the study. However, a greater number of the preferred-self traits of the postgraduate and undergraduate students experienced significant changes than the number of their real-self traits. Figure 9 depicts the comparison of the postgraduate students’ preferred-self traits across the three phases. The result of the nonparametric test showed that 27 of the preferred-self traits of the postgraduate students experienced significant changes over the three phases. Among the 27 traits, 13 traits significantly increased over the three phases (optimism, achievement, dominance, endurance, order, social energy, exhibition, self-confidence, self-satisfaction, creativity, masculinity, respectful and work centered), indicating students’ desire to be stronger in these traits. Four preferred traits (support seeking, self-blaming, self-control and security seeking) decreased significantly over the three phases. The constant decreases in support seeking and self-control indicate that postgraduate students prefer not to seek advice and emotional support and prefer to be less self-controlled and restrained, and the university ought to pay attention to this finding. In addition, eight preferred-self traits (enthusiasm, psychologically perceptive, nurturance, affiliation, personal adjustment, structure valuing, playful and pragmatic) decreased during phase 2, but increased again in phase 3; two preferred-self traits (negativity and counseling readiness) increased during phase 2, but dropped significantly in phase 3. The drop in counseling readiness in phase 3, which is congruent with the constant decrease in support seeking, requires attention from the university, because this finding indicates that the postgraduate students prefer not to accept counseling or professional advice to help them cope with their personal problems and psychological difficulties.

Figure 9. Changes in postgraduate students’ preferred-self personality traits across phases 1, 2 and 3.

* p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

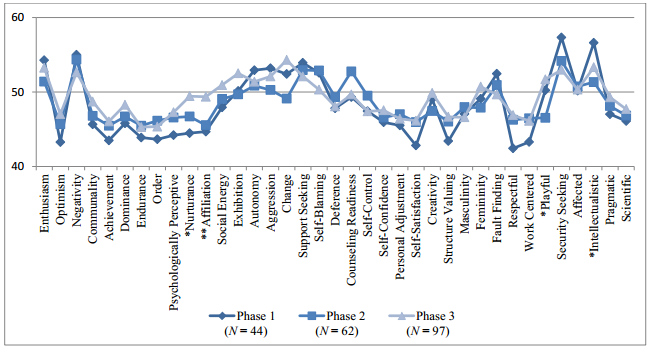

As for undergraduate students, 27 preferred-self traits experienced significant changes over the three phases of the study. Fourteen preferred-self traits increased significantly over the three phases of the study: optimism, achievement, dominance, endurance, order, nurturance, affiliation, social energy, exhibition, self-confidence, self-satisfaction, creativity, respectful and work centered, indicating that undergraduate students had a constant desire to be stronger in these traits. On the other hand, four preferred-self traits decreased over the three phases: support seeking, self-blaming, security seeking and intellectualistic. As mentioned before, the constant decrease in support seeking is concerning because it indicates that students prefer not to seek support and advice when they encounter problems or issues. Undergraduate students showed less desire to be more intellectualistic, suggesting that they prefer not to emphasize versatility, unconventionality and individuality. In addition, eight preferred-self traits decreased during phase 2, but increased again in phase 3 (enthusiasm, communality, psychologically perceptive, change, personal adjustment, structure valuing, playful and scientific), while the negativity trait increased during phase 2 but decreased again in phase 3.

Figure 10. Changes in undergraduate students’ preferred-self personality traits across phases 1, 2 and 3.

* p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

Clearly, postgraduate and undergraduate students shared similar trends in their preferred-self traits (Figures 9 and 10). Both the postgraduate and undergraduate students recorded constant increases in the same 12 preferred traits (optimism, achievement, dominance, endurance, order, social energy, exhibition, self-confidence, self-satisfaction, creativity, respectful and work centered) and constant decreases in three of the preferred-self traits (support seeking, self-blaming and security seeking).

Discussion

Findings on the personality profile of undergraduate and postgraduate students at this research university in Malaysia are promising. The results suggest that students are coping well with the institutional transformation. In fact, personality traits such as optimism, endurance, dominance, order, exhibition, self-confidence and creativity were highly expressed and developed, as profiled in phase 3 of the study. These highly expressed and developed traits indicate that students are dignified, flexible, hopeful and unyielding in their desire to excel. They also value cognitive activity and insight. However, their profile shows some concerns in traits such as support seeking and security seeking, which dropped continuously during the study. Such findings suggest that students may not be ready for counseling and prefer not to seek help and support when they encounter problems.

Because change in an organization may cause strain and uncertainty (Nelson et al., 1995), Marshall (2010) proposed that early assessment and intervention be implemented accordingly. Assessment of students’ perceptions of the transformation initiatives, particularly on teaching, learning and research activities, would help to evaluate the impact of institutional transformation on the psychological well-being of the students (Loretto, Platt, & Popham, 2010). Preparing and guiding students through the transformation process helps them to adapt and thrive (Marshall, 2010; Tosevski, Milovancevic, & Gajic, 2010). Loretto et al. (2010) found that preparation for change and timely training with open communication may build trust and minimize uncertainty by increasing control.

Gradual and orderly structural policy changes may facilitate adjustment and minimize needless stressors. Secrecy and poor communication may result in poor morale and low self-satisfaction (Becker et al., 2004; Nelson et al., 1995; Smollan & Sayers, 2009). In contrast, promoting transparency and coordination in the learning environment may encourage attitudes of independence, objectivity, industriousness, respectfulness, confidence, assertiveness, initiative and enthusiasm. These interventions may help ensure the mental well-being of students, which in turn affects their academic achievement positively and contributes toward the success of the university transformation process. Tosevski et al. (2010) have suggested building trust in instructor-student relationships to promote autonomy and clarify role expectations. Practicing a student-driven learning approach may inspire creativity and leadership, bringing forth greater self-satisfaction among students.

As the university moves toward becoming a world-class institution, students fit themselves into the vision and mission of the university. In this study, the differences between the real-self and the preferred-self traits were most exaggerated in the third phase. When the preferred-self traits are much higher than the real-self traits, students may feel frustrated. According to Rogers (2007), incongruence between real and preferred value in personality traits may increase one’s vulnerability to stress or anxiety. Mild anxiety brings forth self-awareness in response to the incongruence in personality and may result in therapeutic change and the learning of new coping skills (Rogers, 2007). The university can provide counseling services to assist those students who need help.

Conclusion

The APEX initiative is transforming the selected research university to embrace excellence, innovation and dynamism in moving toward the goal of becoming a world-class institution. The results of this study suggest that university students are coping well with the institutional transformation. In fact, many desired personality traits became more strongly expressed and developed during the transformation phases. It is crucial to continually monitor the personality profile and psychological well-being of students. The institution also can implement proactive interventions to support the mental health and development of human capital in all students.

References

Becker, L. R., Beukes, L. D., Botha, A., Botha, A. C., Botha, J. J., Botha, M., . . .Vorster, A. (2004). The impact of university incorporation on college lecturers. Higher Education, 48, 153–172.

Center for Credentialing and Education. (2009). The BeMIS Personality Report for Sample Client. Greensboro, NC: Author.

Connor-Smith, J. K., & Flachsbart, C. (2007). Relations between personality and coping: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 1080–1107. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080

Fernandez, J. L. (2010). An exploratory study of factors influencing the decision of students to study at Universiti Sains Malaysia. Kajian Malaysia, 28(2), 107–136.

Gladstone, J., & Reynolds, T. (1997). Single session group work intervention in response to employee stress during workforce transformation. Social Work With Groups, 20, 33–49. doi:10.1300/J009v20n01_04

Goretti, B., Portaccio, E., Zipoli, V., Razzolini, L., & Amato, M. P. (2010). Coping strategies, cognitive impairment, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurological Sciences, 31(Suppl. 2), S227–S230.

Gough, H. G., & Heilbrun, A. B., Jr. (n.d.). Assess psychological traits with a full sphere of descriptive adjectives. Retrieved from http://www.mindgarden.com/products/figures/aclresearch.htm

Gough, H. G., & Heilbrun, A. B., Jr. (1983). The Adjective Check List manual (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Horng, J., Hu, M., Hong, J., & Lin, Y. (2011). Innovation strategies for organizational change in a tea restaurant culture: A social behavior perspective. Social Behavior and Personality, 39, 265–273. doi:10.2224/sbp.2011.39.2.265

Lievens, F., Ones, D. S., & Dilchert, S. (2009). Personality scale validities increase throughout medical school. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1514–1535. doi:10.1037/a0016137

Loretto, W., Platt, S., & Popham, F. (2010). Workplace change and employee mental health: Results from a longitudinal study. British Journal of Management, 21, 526–540. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2009.00658.x

Marshall, S. (2010). Change, technology and higher education: Are universities capable of organisational change? ALT-J, Research in Learning Technology, 18, 179–192. doi:10.1080/09687769.2010.529107

Ministry of Higher Education. (2011). The National Higher Education Action Plan, Phase 2 (2011–2015). Retrieved from http://www.mohe.gov.my/transformasi/fasa2/psptn2-eng.pdf

Nelson, A., Cooper, C. L., & Jackson, P. R. (1995). Uncertainty amidst change: The impact of privatization on employee job satisfaction and well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 68, 57–71. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1995.tb00688.x

Oreg, S., & Sverdlik, N. (2011). Ambivalence toward imposed change: The conflict between dispositional resistance to change and the orientation toward the change agent. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 337–349. doi:10.1037/a0021100

Oreg, S., Vakola, M., & Armenakis, A. (2011). Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47, 461–524. doi:10.1177/0021886310396550

Razak, D. A. (2009). In search of a world-class university of tomorrow: The importance of the APEX initiative. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Oxford Fajar.

Rogers, C. R. (2007). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 44, 240–248. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.44.3.240

Schraeder, M., Swamidass, P. M., & Morrison, R. (2006). Employee involvement, attitudes and reactions to technology changes. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 12, 85–100. doi:10.1177/107179190601200306

See, C. M., Abdullah, M. N. L. Y., Teoh, B. S. G., & Yaacob, N. R. N. (2011). Profiles of an Accelerated Programme for Excellence (APEX) university community: Personality traits and psychosocial behavior. Monograph Series of USM, 14, 1–88.

Smollan, R. K., & Sayers, J. G. (2009). Organizational culture, change and emotions: A qualitative study. Journal of Change Management, 9, 435–457. doi:10.1080/14697010903360632

Tosevski, D. L., Milovancevic, M. P., & Gajic, S. D. (2010). Personality and psychopathology of university students. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 23, 48–52. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328333d625

Wan, A. M. W. M. (2008). The Malaysian National Higher Education Action Plan: Redefining autonomy and academic freedom under the APEX experiment. Paper presented at the Asaihl Conference, University Autonomy: Interpretation and Variation, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia.

Wynaden, D., Wichmann, H., & Murray, S. (2013). A synopsis of the mental health concerns of university students: Results of a text-based online survey from one Australian university. Higher Education Research & Development, 32, 840–860. doi:10.1080/07294360.2013.777032

See Ching Mey is Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the Division of Industry and Community Network at the Universiti Sains Malaysia. Melissa Ng Lee Yen Abdullah is a senior lecturer in the School of Educational Studies at the Universiti Sains Malaysia. Chuah Joe Yin is the assistant registrar in the Division of Industry and Community Network at the Universiti Sains Malaysia. Correspondence can be addressed to See Ching Mey, Division of Industry and Community Network, 6th Floor, Chancellory Building, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800, Penang, Malaysia, cmsee@usm.my.

Oct 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 4

Lisa D. Hawley, Todd W. Leibert, Joel A. Lane

In this study, we examined the relationship between various indices of socioeconomic status (SES) and counseling outcomes among clients at a university counseling center. We also explored links between SES and three factors that are generally regarded as facilitative of client change in counseling: motivation, treatment expectancy and social support. Regression analyses showed that, overall, SES predicted positive changes in symptom checklists over the course of treatment. Individual SES variables predicting positive change were educational attainment and whether the client had health insurance. SES was not associated with motivation, treatment expectancy or social support. Implications for SES research and counseling are discussed.

Keywords: socioeconomic status, counseling outcomes, social support, motivation, treatment expectancy, university counseling center

There is a robust relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and mental health (Goodman & Huang, 2001; Strohschein, 2005), a finding that researchers have consistently replicated (Adler, Epel, Castellazzo, & Ickovics, 2000; Kraus, Adler, & Chen, 2012; Muntaner, Eaton, Miech, & O’Campo, 2004; von Soest, Bramness, Pedersen, & Wichstrøm, 2012). Furthermore, researchers have linked SES to important outcomes in a number of domains, including academic achievement and employability (Blustein et al., 2002) and health service utilization (Goodman & Huang, 2001). Pope-Davis and Coleman (2001) argued that SES is an important cultural variable that is closely aligned with race and gender. Despite the risk factor that SES poses for mental health and well-being, the current literature does not empirically represent SES as much as other cultural variables, especially with regard to counseling outcome research (Falconnier, 2009; Liu, 2011). To respond to this shortcoming, we investigated potential links between SES and counseling outcome.

SES and Mental Health

SES as a Variable of Study

In the last 20 years, two content analyses have reviewed cultural variables and SES within counseling (Liu, Soleck, Hopps, Dunston, & Pickett, 2004; Pope-Davis, Ligiero, Liang, & Codrington, 2001). Liu et al. (2004) reviewed three journals from 1981–2000 and concluded that SES was mainly studied post hoc, and used primarily to account for unexplained variance. Similarly, focusing on the Journal of Multicultural Counseling between the years of 1985 and 1999, Pope-Davis et al. (2001) analyzed the content of articles for prominent multicultural variables and found that SES was underexamined as a primary variable of study. Taken together, both content analyses pointed to an overall lack of attention to SES in mental health counseling literature.

There is agreement regarding the multicultural and social justice relevance of economic empowerment and SES in the field of counseling (Ratts, Toporek, & Lewis, 2010); however, available SES counseling literature is predominantly conceptual and not empirical. There are several possibilities for the overall lack of empirical investigations into SES and counseling outcomes. First, only recently have mental health counselors made a concerted effort to empirically demonstrate counseling outcomes (Hays, 2010). In addition, Smith, Chambers, and Bratini (2009) opined that, while research on the pathogenic impact of poverty on emotional well-being is robust and logical, the development of practitioner-based interventions has been limited. The counseling profession has not been a leader in empirically studying this complex variable, which further limits the profession’s contributions to research-based interventions. Moreover, SES is complex (Liu et al., 2004); its etiology is often interconnected with mental health risk factors. One challenge of SES research, then, is effectively conceptualizing which aspect of the variable to address first. This challenge is best expressed in the old adage “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?” In other words, do lower SES levels lead to higher rates of mental health disorders or do higher rates of mental health disorders lead to lower SES levels? Eaton, Muntaner, Bovasso, and Smith (2001) identified four possible answers: (a) Lower SES raises the risk of developing a mental health disorder, (b) lower SES prolongs the duration of a mental health disorder episode, (c) mental health disorders lead to downward social mobility or (d) mental health disorders hinder attainment of upward SES status. It also is plausible that these answers are not mutually exclusive, further complicating the role of SES in mental health.

Objective Versus Subjective Indicators of SES

Another possible reason for the limited pursuit of SES research is the difficulty in operationalizing SES. As a construct, SES is multifaceted, impeding the use of discrete variables (Liu et al., 2004). Frequently it is measured using objective, actuarial data such as household income, occupation, zip code and healthcare coverage. However, Braveman et al. (2005) demonstrated that objective indicators of SES, such as education and income, are inadequate because they are not interchangeable with other SES indicators of wealth, education and neighborhood (e.g., zip code clusters). Braveman et al. (2005) concluded that better measures were needed, especially subjective SES measures, such as perceptions of financial security and broad, culturally driven definitions such as lower-, middle- and upper-class SES levels (Adler et al., 2000; Dennis et al., 2012). Other researchers have reached similar conclusions after using both subjective and objective markers of SES (Adler et al., 2000; Hillerbrand, 1988). Even formal measures of SES, including the Hollingshead’s SES indicator (Hollingshead, 2011) and the Duncan Socioeconomic Index (Duncan, 1961), make limited use of subjective measurement strategies. Liu, a leading advocate for the study of SES in counseling, emphasized the need for a multidimensional approach for data collection to best capture contemporary client experiences (Liu, 2011; Liu et al., 2004). In this article, we integrate subjective and objective variables and examine their impact on clinical outcomes.

SES and Clinical Outcomes

In general, psychotherapy reviews show that higher SES is associated with greater therapy retention (Clarkin & Levy, 2004; Petry, Tennen, & Affleck, 2000). However, SES is not consistently related to symptom reduction (Petry et al., 2000). On the other hand, SES does relate to counselor perceptions of the client. For example, in one study at a university counseling center, 163 case files were randomly selected to evaluate the association between the Hollingshead SES rating scale and therapy outcome (Hillerbrand, 1988). According to the results, counselors rated clients with lower SES levels as having greater dysfunction, greater goal disagreement about treatment and less successful counseling outcomes. Mental health practitioners have perceived clients as less motivated when they have lower SES levels (Leeder, 1996) and lack similar social support (Beatty, Kamarck, Matthews, & Shiffman, 2011). In another study, counselors and counselor trainees rated case vignettes and videos of presenting problems featuring clients from either lower or higher SES (Dougall & Schwartz, 2011). Again, counselors rated lower-SES clients as having more severe problems than higher-SES clients. These results reflect other research investigating perceptions and attitudes about lower-SES populations. Historically, clinicians have tended to view poorer clients as lacking in effort (Feagin, 1975; Kluegel & Smith, 1986) and motivation (Seccombe, James, & Walters, 1998), and as being apathetic and passive (Leeder, 1996). Although these studies provide some useful information regarding the present line of inquiry, studies related to clinical outcome and SES as a main variable of study are sparse (Liu, 2011). There is a need to better refine and understand the relationship between SES and mental health.

Present Study

To address the dearth of counseling outcome studies examining SES, the primary purpose of the present study was to prospectively explore the relationship between SES indicators and counseling outcome. In light of the aforementioned SES literature (e.g., Braveman et al., 2005; Adler et al., 2000), we conceptualized SES as including a combination of objective data and subjective self-perceptions regarding class. Thus, in operationalizing SES as a variable of study, we collected commonly researched objective indices—namely educational attainment, household income and health insurance status, as well as subjective data including client perceptions of financial security and class level.