Sep 12, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

Lynn K. Hall

Increasingly, mental health professionals are providing counseling services to military families. Military parents often struggle with child-rearing issues and experience difficulty meeting the fundamental needs for trust and safety among their children because they are consumed with stress and their own needs. Within this article, military family dynamics are discussed and parenting styles, namely coercive, pampering or permissive and respectful leadership, are explored. The authors conclude by highlighting counseling interventions that

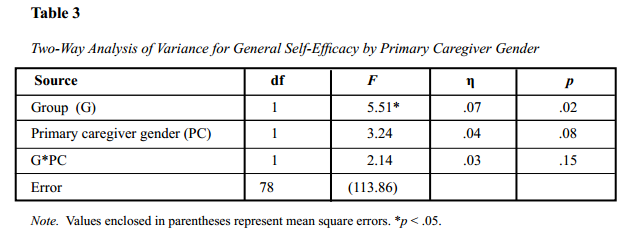

may be effective for working with military parents and families.

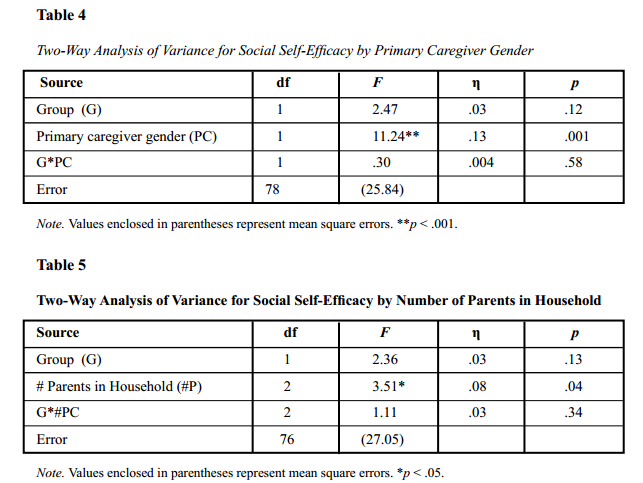

Keywords: military parents, family dynamics, child-rearing, safety, counseling interventions

In 1994, Donaldson-Pressman and Pressman began tracking families in their practice who had many of the dynamics of alcoholic or abusive families, but had no history of alcohol abuse, incest, physical abuse, emotional neglect or physical absence. The one consistent characteristic of those families was similar to many military families that I worked with, which was that “the needs of the parent system took precedence over the needs of the children” (Donaldson-Pressman & Pressman, 1994, p. 4). It is because of this dynamic that I chose to use the term “parent-focused families” when writing about parenting issues in the book, Counseling Military Families: What Mental Health Professionals Need to Know (Hall, 2008). Developmentally, many military parents who are struggling with child-rearing issues have difficulty meeting the fundamental needs for trust and safety for their children because they are consumed with their own needs (Hall, 2008). One of the major challenges of military families is learning how to operate within the larger external system of the military without complaint or unreasonable expectations.

Wertsch (1991) described this dynamic as the stoicism of the military, or the need to be ready, maintain the face of a healthy family, and do what is expected without showing discontent or dissatisfaction. A second important dynamic is secrecy, or not allowing what happens in the family to impact the military parent’s career. The third dynamic, denial, also is present in most military families as they make numerous transitions and experience issues like the deployment of the service member (Wertsch, 1991). In order to survive, the non-military parent and children often deny the emotional aspect of these transitions, as well as more “normal” developmental transitions. In many parent-focused military families, particularly when there is a child who is acting out or in other ways exhibiting behavior problems, these three dynamics often lead to other characteristics (Hall, 2008) such as:

1. The belief that the child is the problem, rather than the child may have a problem.

2. The child is given a label, such as lazy or stupid, rather than understanding that the behavior may be the result of a mental health, developmental or learning problem.

3. Children sometimes learn early that, if expressed, their feelings may make things worse so that detaching emotionally becomes quite functional.

4. Once they discover that their feelings will not be validated, they may learn to distrust their own judgments and feelings.

5. The child may take on the responsibility of meeting the emotional and sometimes physical needs of the parents.

6. If either parent is inconsistently emotionally available, children may have difficulty letting down the barriers required for intimacy later in life (Hall, 2008; Donaldson-Pressman & Pressman, 1994).

These characteristics, when played out in military families, are a reflection of the secrecy, stoicism and denial often demanded of these families. Instead of providing a supportive, nurturing, and reality-based mirror, the parents may present a mirror that only reflects their needs, resulting in children who grow up feeling defective (Hall, 2008). “When one is raised unable to trust in the stability, safety, and equity of one’s world, one is raised to distrust one’s own feelings, perceptions, and worth” (Donaldson-Pressman & Pressman, 1994, p.18).

When we look at the demographics of military families, we see that most military dependent children are born to very young couples who have been removed from their extended support system or other supportive older adults on whom they can rely. For almost all military children, their physical and psychological needs are indeed met during childhood; however, when children begin to assert themselves and/or make emotional demands, which often begins in early to middle adolescence, the parental system may be unable to tend to the children’s needs. Parents who are under a great deal of stress and perhaps faced with a high level of uncertainty around issues like multiple deployments may find themselves resentful or threatened by the needs of the children. The ability to understand how some families in the military are organized, not just because of who the parents are but, more importantly, who the parents are in the midst of the demands of the “warrior fortress” in which they live, is essential in working with these families (Hall, 2008).

Parenting in a Democratic Society

One counselor explained that military couples are often not faced with the typical life decisions or choices of civilian couples, such as buying a home or relocating because of an available career opportunity (Hall, 2008). At the same time, military couples and families are required to relate to and often spend a great many years living in our mostly democratic American world. This counselor often finds it necessary to point out to parents of adolescents that, while the parents may have adjusted well to living in the authoritarian military structure, rebellious teens often see the world in a different way. A typical military parental response to a rebelling teen is to tighten the rules, becoming more vigilant and rigid. This is often the result of the fear of losing control or their place as the head of the household. “Children of the military, whether they live on base or not, live, at least part of their life, in a democratic society; they go to democratic schools and their parents are serving the mission of defending a democratic nation. It is understandable, then, how those who face strictly authoritarian parenting or home life might be confused and perhaps become rebellious” (Hall, 2008, p. 119).

McKay and Maybell (2004) write about the democratic revolution which they define as an “upheaval in all of our social institutions: government, education, the workplace, race relationships, gender relationships and families” (p. 64). As these authors point out, during the last few decades most social institutions and relationships in the United States have operated from an equality identity that values attitudes of equal values and respect. These societal changes require new attitudes toward oneself and others, as well as a new set of knowledge and skills (Hall, 2008; McKay & Maybell, 2004). The military, on the other hand, has not changed to an egalitarian institution: it never will because it could not survive. But, regardless of how the military organizes itself and its members, the military family still lives, at least to some degree, in a democratic society. This means the individual members of the family will often struggle as they go back and forth between the authoritarian world of the military and the democratic world in which they both come from and continue to be a part (Hall, 2008).

While McKay and Maybell (2004) were addressing the conflict in the greater society over the last few decades, their description of the “tension, conflict, anger, and even violence . . . as we move from the old autocratic tradition to a new democratic one” (p. 65) clearly describes the ongoing challenge for military parents. These are valuable insights when understanding the children and the families of the military, many of whom may view the world outside of the military quite appealing and then begin to rebel against the rigid structure they are forced to live within. This theoretical framework can be a useful tool for counselors in helping families understand the need to move from the external often rigid superior/inferior military structure to a more egalitarian structure in the home that encourages and respects each individual in the family but still maintains the hierarchical need for parental control that is necessary for all functioning families (Hall, 2008).

Helping parents to assess their current parenting style, and then to consider how to modify their parenting practices from patterns that are discouraging for their children to those that are encouraging, can be extremely valuable for family growth and development. Whether this is done in a parent training environment or a family counseling setting, helping parents adjust their style will directly impact their children’s behavior. McKay and Maybell (2004) describe three of the most common parenting styles: the coercive parenting style, the pampering or permissive parenting style and the respectful leadership style. Because these authors have years of Adlerian training and writing experience, the reader will recognize that these parenting styles correspond to previous parenting literature written by Adlerian writers. The first two often discourage the healthy development of children; the third is not only respectful, but can be both encouraging and empowering (Hall, 2008).

Coercive Parenting

The coercive parenting style is often the style used to control children for their own good and is often the style of parenting used in parent-focused families, as well as the families of very young parents who have little family support (McKay & Maybell, 2004). It is often the style we find in military parents with children who are rebelling or acting out. The parents maintain control by giving orders, setting rules, making demands, rewarding obedient behavior, and punishing bad deeds (Hall, 2008). McKay and Maybell call this model limits without freedom. These parents almost always have good intentions and want to make sure their children avoid many of life’s mistakes; their goal is simply to teach their children the right way before they get hurt. The need for children to accommodate a subordinate identity may work for a while, at least when the children are young. However, when children want to be acknowledged for their individuality or want to be respected as an individual, this style can result in conflict and power struggles (Hall, 2008). “Kids tend to become experts at not doing what their parents want them to do and doing exactly what their parents don’t want” (McKay & Maybell, 2004, p.71). The results of coercive parenting are often kids who either need to get even, resulting in a constant war of revenge, or kids who submit to the coercion and learn to rely only on those in power to make their decisions (Hall, 2008), either of which can be destructive to the healthy development of children.

Pampering or Permissive Parenting

The permissive parenting style (McKay & Maybell, 2004) is used by parents whose goal is to produce children who are always comfortable and happy, by either letting them do whatever they please or by doing everything for them. This parenting style is referred to as freedom without limits and is often the style that current popular literature calls helicopter parenting. These children often end up considering themselves to be the prince or princess and their parents their servants. They can develop a “strong sense of ego-esteem with little true self- or people-esteem” (McKay & Maybell, 2004, p.72). Often they have under-developed social skills and can become too dependent on others. Parents eventually, however, may resent how much they are doing for their children, leading to conflict and power struggles. With so few limits, children believe they not only can do anything they want, but believe they should be allowed to do anything they want, leading to a sense of entitlement along with a lack of internal self-discipline or self-responsibility (Hall, 2008).

These first two parenting styles can even exist in the same family, where one parent is the authoritarian (in a military family, usually the military parent) and the other is the permissive parent who lessens the rules of the authoritarian parent, particularly when that parent is absent. School behavior often worsens upon the return of the military parent from deployment. If asked, young people will say that everything was fine at home while the service member parent was gone, but now that the parent has returned and started cracking the whip, the teens often turn to rebellion or other inappropriate behaviors (Hall, 2008).

Respectful Leadership

The third parenting style is the only encouraging style for children; it is the style of respectful leadership (McKay & Maybell, 2004), or freedom within limits. The parents value the child as an individual and value themselves as leaders of the family through the guiding principle of mutual respect in all parent-child interaction. Giving choices is the main discipline approach with the goal of building on individual strengths, accentuating the positive, promoting responsibility, and instilling confidence in the children (Hall, 2008). This parenting style, in both the civilian and military worlds, can help build respectful, responsible children. Emphasizing that parents are not giving up their leadership role in order to parent their children is especially important in military families. Combining that with the concept of “respect” makes sense within the military culture.

A counselor told of an Army officer who brought his 16-year-old daughter to counseling because she was acting out. He insisted that she come home at her curfew time and she quit hanging out with the boys he disapproved. She responded with a typical angry look that caused Dad to come unglued. The counselor asked Dad what his biggest fear was for his daughter, thinking that he would be worried about her becoming pregnant, not finishing school, or any of a number of other possible responses. After thinking and, for the first time, with tears in his eyes, Dad said that she might leave him like her mother did. The spirit of counseling changed at that point. With a look of complete astonishment on the daughter’s face, she started crying and told her dad that she thought he wanted her to leave because he couldn’t face her after her mom left. The counselor was able to help Dad see that setting rigid rules that had to be tightened up every time they were broken, might not work as the two of them forged a new relationship and he allowed her to mature into a responsible young woman. Helping him find ways to include her in setting limits and in household decisions, as it was now just the two of them, went a long way in repairing their relationship, as well as in empowering her to make healthy decisions in other parts of her life.

Working with Parents

Helping parents understand how their parenting style impacts child development can often be a counselor’s most valuable teaching tool. While it sounds easy, it is not; parents need guidance and direction on how to give choices, when to give choices, and how to be creative in choosing appropriate consequences. Parents have to learn to start small, start young (when possible), and be willing to make mistakes. The Adlerian principle of the courage to be imperfect also must be a part of parent education. Parents all want the best for their children; helping them promote responsibility and confidence by making adjustments in their parenting style can help them reach these goals. As early as 1984, Rodriguez wrote that in a rank-privileged and -oriented social system like the military, this mix of caste formation and egalitarianism may create a difficult dichotomy, particularly for children and adolescents struggling for their identity. This dichotomy can be exacerbated by the parent-focused nature of the military when parents are concerned about how their child’s misbehavior might affect the parent’s status in the military. Children become sensitive to this parental anxiety and the anger that follows when they break community rules or military social norms. In some military communities, particularly those that are isolated and where rules are strongly enforced, children have little room to make mistakes or test the limits of authority in a normal, developmental manner, without impacting the family status or the military parent’s career (Hall, 2008).

It is important to point out that not all military families struggle with these issues; the great majority carry out their parenting duties extremely well and raise healthy children, often in the midst of difficult situations. Jeffreys and Leitzel’s (2000) study noted that a caring relationship and low family stress is associated with resiliency. If children have an emotionally supportive relationship with their parents, they are more likely to demonstrate high levels of self-esteem and healthy psychological development. Their study (Jeffreys & Leitzel, 2000) of military families suggests that family climate promotes the participation in family decision-making and is positive for adolescent identity development. Effective communication patterns facilitate family interaction and are associated with social competence. This finding is reflected in McKay & Maybell’s (2004) respectful leadership style of parenting and can help mental health counselors focus their work on helping military parents learn the parenting skills necessary to reach their goals of having competent, healthy and responsible children, as well as coping with the sometimes overwhelming challenges they face while serving in the military.

References

Donaldson-Pressman, S., & Pressman, R. M. (1994). The narcissistic family: Diagnosis and treatment. San Francisco,

CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hall, L. K. (2008). Counseling military families: What mental health professionals need to know. New York, NY:

Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group.

Jeffreys, D. J., & Leitzel, J. D. (2000). The strengths and vulnerabilities of adolescents in military families. In J. A. Martin, L. N. Rosen, & L. R. Sparacino, (Eds.). The military family: A practice guide for human service providers (pp. 225–240). Westport, CT: Praeger.

McKay, G. D., & Maybell, S. A. (2004). Calming the family story: Anger management for Moms, Dads, and all the kids. Atascadero, CA: Impact.

Rodriguez, A. R. (1984). Special treatment needs of children of military families. In F. W. Kaslow & R. I. Ridenour (Eds.) The military family: Dynamics and treatment (pp. 46–72). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Wertsch, M. E. (1991). Military brats: Legacies of childhood inside the fortress. New York, NY: Harmony Books.

Lynn K. Hall, NCC is Dean of the School of Social Sciences at the University of Phoenix. Correspondence can be addressed to Lynn K. Hall, College of Social Sciences, University of Phoenix, 4605 E. Elwood St., Phoenix, AZ 85040, lynn.hall@phoenix.edu.

Sep 11, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

George Davy Vera

In the worldwide community it is not well known that counseling and guidance professional practices have a long tradition in Venezuela. Therefore, this contribution’s main purpose is to inform the international audience about past and contemporary counseling in Venezuela. Geographic, demographic, and cultural facts about Venezuela are provided. How counseling began, its early development, and pioneer counselors are discussed. The evolution of counseling from an education-based activity to counseling as a technique-driven intervention is given in an historical account. How a vision of counselors as technicians moved to the notion of counseling as a profession is explained by describing turning points, events, and governmental decisions. Current trends on Venezuelan state policy regarding counselor training, services, and professional status are specified by briefly describing the National Counseling System Project and the National Flag Counseling Training Project. Finally, acknowledgement of Venezuela’s counseling pioneers and one of the oldest counseling training programs in Venezuela is described.

Keywords: Venezuela, history of counseling, clinical interventions, policy, training programs

Venezuela is located on the northern coast of South America, covering almost 566,694 square kilometers (km; 352,144 square miles). It is bordered by the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, Guyana, Brazil, and Colombia, with a total land boundary of 4,993 km (3,103 miles) and a coastline of 2,800 km (1,740 miles). Its population is approximately 29 million and mostly Catholic. Some aboriginal groups practice their own traditional magical-religious beliefs. Since its independence, emigrants from different parts of the world have helped build the country’s culture and economy. Diverse populations of Arab, Dutch, Chinese, and Japanese, among others, live in Venezuela.

Even though several ethnic groups prevail in the country today, three groups are clearly distinct from its origin: European white, African black and Native aborigines. After five hundred years of blending, three different culturally and ethnically groups have emerged: Mulato (white and black), Zambo (black and aborigine), and Mestizo (white and aborigine). Although Venezuela has ethnic compositions and mixtures, all Venezuelans have the same rights and duties under the Bolivarian Constitution of 1999. More Venezuelan differences and prejudices are related to social, educational, economic, and political status.

Economically, Venezuela has one of the largest economies in South America due to its oil production; however, a large number of its population remains in poverty. Today, the current administration has created different popular programs, called missions, to deal with most Venezuelans’ needs including lack of education, employment, health care, and public safety, among others. So far, according to the United Nations (UN) and UNESCO’s official reports, Venezuela has reached most of its millennium goals established by the UN. Politically, after several years of turmoil, Venezuelan society reached a normal democratic institutional peace in 2004.

Early Developments of Counseling in Venezuela

During the 1930s, counseling in Venezuela began as a form of educational guidance and counseling concerned with academic and vocational issues using mainly psychometric approaches. Some Venezuelan counseling pioneers were European emigrants. In fact, during the 1940s, some school counseling services were created by Dr. Jose Ortega Duran, an educator; Professor Miguel Aguirre, a counselor; Professor Vicente Constanzo, teacher and philosopher; and Professor Antonio Escalona, a career counselor and professor (Benavent, 1996; Calogne, 1988; Vera, 2009). Because of the education and training of these early pioneers, counseling in Venezuela was conceived as an educational, vocational, and career-oriented service.

A formal definition of the counseling and training of professional counselors has slowly evolved from the 1960s to today. Because of the oil industry development, Venezuela moved from an agricultural to an industrial economic base. Because of this, the Venezuelan population grew rapidly and rural farmers moved to the major cities, which were demanding more workers, specialized employees, and technicians. Therefore the demand for better education to satisfy new jobs related to industrial demands and pressured the government to create new policies concerning education. One of the new policies regarded counseling and guidance services. Therefore, in the early 1960s the government created the first counselor education training program (Calogne, 1988; Moreno, 2009; Vera, 2009).

By an agreement between the Ministry of Education and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), counseling professors from the U.S. were hired to train school teachers in counseling and guidance. The training focused on personal counseling techniques and strategies, counseling theory and methods, and educational counseling. Because the training emphasized basic counseling knowledge and techniques for school teachers, a vision of counseling and guidance as educational activities within the scope of the school teacher role emerged. Accordingly, counseling and guidance was understood as a technique-based activity oriented to help students with academic, vocational, career, and personal issues. Later, the Ministry of Education requested that the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas create a formal, three-semester educational training program in counseling and guidance.

As a result, in 1962 the Ministry of Education requested that the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas house the first formal counselor education program in Venezuela. Counseling and guidance was conceived as knowledge and intervention techniques to help with students’ personal growth and academic performance. The term Orientación was chosen to better signify counseling and guidance in Venezuela’s Spanish language. Graduates from this program received a college diploma as orientador. Both terms, orientación and orientador, were thus used in the country for the first time.

Another consequence of the counselor education program at the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas was its contributions to a new vision of counseling as a technique-oriented educational program. Therefore, counseling was conceived as a technical occupation that emerged within the scope of education. By this time, counseling had achieved official and public recognition as a social occupation that required proper education and a set of formal conditions for practice. The Ministry of Education used this new vision of counseling to create the first jobs defined as counselor positions within Venezuela’s educational system (Vera, 2009).

From Counselors as Technicians to the Counseling Profession

Shortly after the first graduates in counseling started their practice, the Ministry of Education understood that the practice of counseling and guidance was more complex than originally perceived and realized that the high demand for counseling services was calling for rapid institutional answers to counseling-related questions. As a result, the National Counseling System, known as the Counseling Division of the Ministry of Education, was developed. This organizational structure was responsible for all counseling matters countrywide, including hiring conditions, developing counseling services, supervising, and training requirements. From this Division, counseling as a profession was envisioned as a human development model (Aquacviva, 1985; Calogne, 1988).

Because counselor employment was now available within the Ministry of Education, several universities established guidance and counseling training options as a five-year bachelor’s degree. Consequently, the first bachelors’ degrees in education majoring in guidance and counseling (mención orientación) were granted in the early 1970s. Master’s level degrees in guidance and counseling granted by the Pedagogic Institute of Caracas were also awarded during this time.

Some of the early graduates from these programs went abroad, mainly to the U.S., to obtain advanced counseling and guidance education and training at the master’s and doctoral levels. Upon returning to Venezuela, they engaged in teaching and training in counseling and guidance at different colleges and some were hired by the Ministry of Education. Other graduates concentrated their energy on organizing counseling professional associations. As a result, American theories, models, and views of the counseling profession in the 1970s and 1980s were fused with Venezuela’s view of counseling and guidance (Vera, 2009).

Because most Venezuelan counselors had been educated abroad, a number of trends in counselor education were adopted. For instance, some bachelors’ level counseling education programs were based on a vision of guidance and vocational education (e.g., Venezuela Central University and the University of Carabobo), while other programs assumed a vocational and academic perspective (e.g., Liberator Pedagogical University), and yet others implemented individual, lifelong approaches (e.g., The University of Zulia and the University Simon Rodriguez). Finally, the Center for Psychological, Psychiatric, and Sexual Studies of Venezuela clearly embraced an educational and mental health counseling standpoint in masters’ level training. (However, for political and governmental reasons, some of these early programs no longer exist.)

Between the 1970s and 1980s professionalism in counseling was embraced because counseling- and guidance-related organizational movements emerged. Counseling associations were organized and began to promote a vision of counseling as an independent profession from education, psychology, and social work. One of these associations was the Zulia College of Professional Counselors (ZCPC), which was responsible for raising the visibility of professional counseling in Venezuela by creating the first Counseling Code of Ethics, advocating for counseling jobs, and becoming a valid interlocutor between professional counselors and the government.

The ZCPC was established by a group of counseling professors and early graduates from the bachelors’ degree of education in counseling and guidance. During the 1970s and 1980s, counselors in this organization started developing a cultural base for counseling knowledge. In particular, ZCPC established professional meetings for discussing counseling profession matters such as advanced education, professional identity, and social responsibility.

By this time, counseling master’s programs were available in several parts of Venezuela. Hence, professionalism came to light and important matters for counseling’s future development were assumed by counselor educators, practitioners, and associations.

Current Trends: Contemporary Concerns for Professional Practice and Education

Currently, several professional matters regarding counseling are taking place in Venezuela, one being the status of counseling as an independent profession. The Venezuela Counseling Associations Federation (FAVO) will soon introduce a legislative proposal concerning professional counseling practice. If it is passed, Venezuelan counselors will have their first counseling practice law granting counselors’ independent professional practice based on research, knowledge, specified training, and educational requirements.

Another important matter is the creation of the Venezuela Counseling System. This system will organize and provide counseling to the population by a diverse delivery of services and programs based on a vision of counseling for personal, social, cultural, and economical enhancement within the context of a humanistic, democratic, participatory, and collective society. The system is designed and based on the Venezuela Bolivarian Constitution, which guarantees human rights related to social inclusion and justice, freedom, education, mental health, vocational needs, employment, lifelong support, and opportunities for individual development and family prosperity. The system is organized into four areas: education, higher education, community, and the workplace or economic sector. The system is already approved by the Ministry of Higher Education and the formal government resolution and implementation process is pending.

The system embraces advanced concepts and new trends related to professionalism, practice, and the social responsibility of counseling professionals. This includes certification for counseling practitioners, supervision, and credentialing via continuing education for professionals in order to ensure quality. Structurally, the system will be connected to all Venezuelan Ministries for functions and planning purposes, but will be independently managed by a national committee appointed by the Ministry of Higher Education, holding advanced degrees in counseling and appropriate counseling credentials.

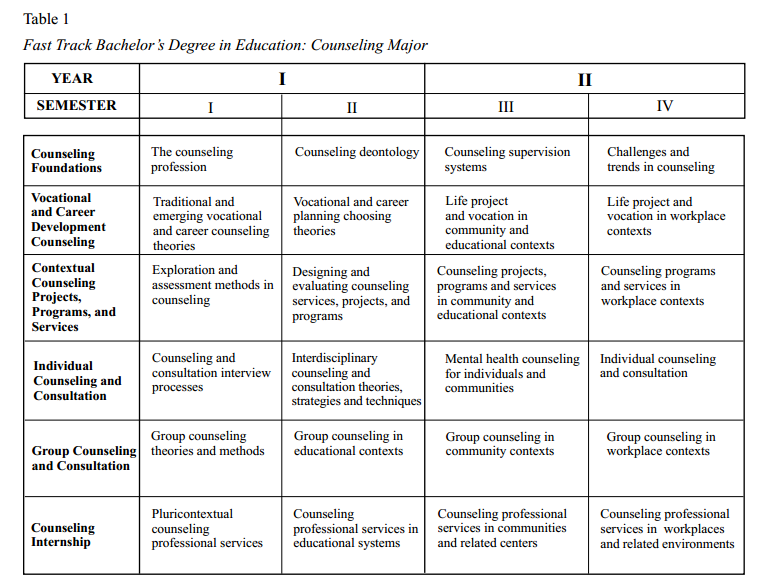

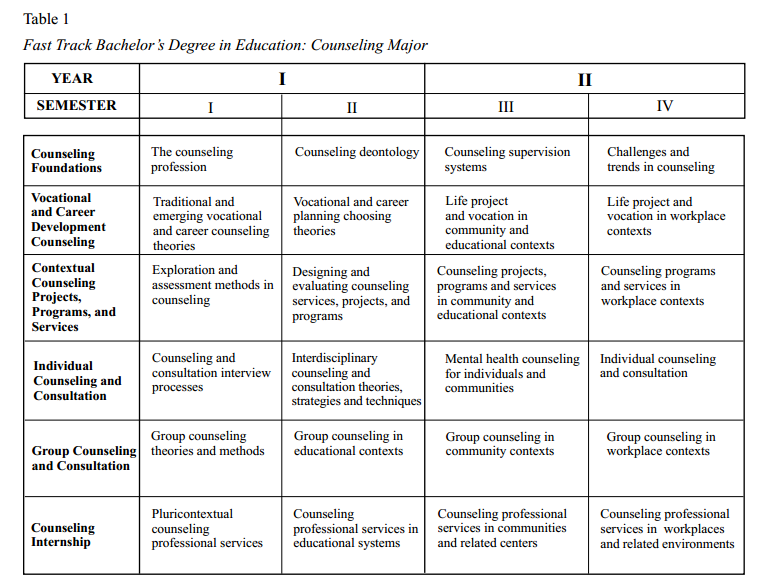

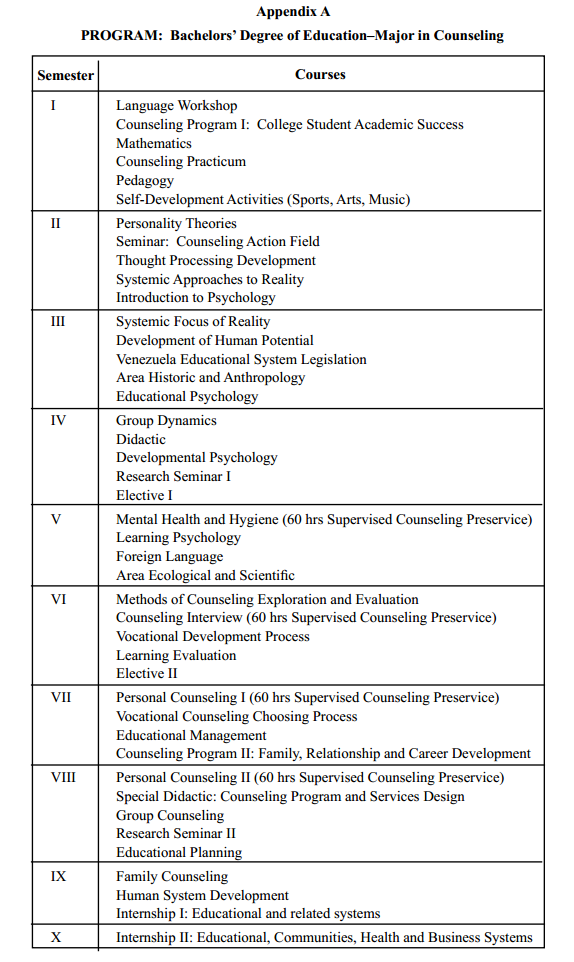

A third matter is related to counseling training programs. Because the Counseling National System will require a large number of trained counselors in the next ten years, new counseling training programs will be created by public and private universities to ensure the quality of counselor training and to satisfy system requirements. Consequently, the government has requested that counseling experts propose a unique counseling training program based on core counseling knowledge, techniques, supervision, and other key features. For details on the proposed counseling program coursework, see Table 1.

The proposed National Counseling Professional Program (NCPP) will be at the bachelor’s level and four semesters long. A unique prerequisite of this program is that applicants must already hold one of these bachelors’ degrees: education, psychology, social work, sociology, industrial engineering, philosophy, pedagogy, or physician.

The proposed NCPP will be organized into core areas and will educate counseling professionals according to the following general objectives:

1. Educate professional counselors to satisfy the needs of the Counseling National System, its subsystems, and any other professional counseling contexts.

2. Develop critical, reflective, dialectical and dialogical counseling professionals. Understand theoretical and conceptual information related to the counseling field and its interdisciplinary sources.

3. Acquire the theory based and applied competencies of the counseling profession in diverse contexts.

4. Understand Venezuelan counseling’s historical roots and its international origins.

5. Understand the ethical dimensions of the counseling profession and the legal characteristics of counseling practice.

6. Actively participate in the development of solidarity, participatory and responsible collectivist citizenship.

7. Articulate counseling professional actions with Venezuela’s social, cultural, and economic development.

8. Use the cultural and social bases of the counseling profession in creating lifelong counseling services.

9. Bond the training and practices of professional counselors with plans and guidelines for Venezuela’s cultural, social, and economic development.

10. Train professional counselors needed for the Venezuelan police.

Other counseling training programs will be developed according to the official training program. Institutions may develop their own specific program, but must include the official requirements.

A last concern is professional counselor certification, supervision, and continuing education. FAVO has worked on these matters since 2004 in collaboration with the NBCC International. FAVO is developing Venezuela’s first National Counselor Certification System as well as conceptualizing a national supervision model and continuing education. FAVO granted the first group of national certified counselors in 2010 and is planning for the first group of trained and certified counselor supervisors in 2011.

Final Thoughts

After years of counselor education evolution and counseling services growth, the professionalization of counseling in Venezuela is now happening, but it depends on Venezuelan counseling leaders to develop a strong advocacy movement. Accordingly, Venezuela’s current political climate has the extraordinary opportunity to pass the Venezuela Counseling Law Proposal in the National Assembly. This may be possible if FAVO has successes in the implementation of the Venezuela National Counseling Certification System because this can help in the task of alerting Venezuela’s professional counselors. Accordingly, counselors’ sense of professionalism might spark the enthusiasm needed for involvement in a strong advocacy movement.

Finally, according to experiences in different parts of the world, it can be concluded that not only in Venezuela, but worldwide, the profession of counseling is an emerging phenomenon; therefore, international counseling institutions and organizations need to begin acting on how to face the worldwide challenges for professional counselors.

References

Benavent, J. (1996). La orientación psicopedagógica en España. Desde sus orígenes hasta 1939. Valencia, VZ: Promolibro.

Calogne, S. (1988). Tendencias de la Orientación en Venezuela. Cuadernos de Educación 135. Caracas, VZ: Cooperativa Laboratorio Educativo.

Moreno, A. (2009). La orientación como problema. Centro de investigaciones populares. Caracas, Venezuela: Colección Convevium.

Vera, G. D. (2009). La profesión de orientación en Venezuela. Evolución y desafíos contemporáneos. Revista de Pedagogia, Universidad Central de Venezuela.

George Davy Vera teaches in the Counselor Education Program, Universidad de Zulia, Maracaibo, Venezuela. Dr. Vera expresses appreciation to Dr. J. Scott Hinkle for editorial comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Correspondence should be directed to George Davy Vera, avenida 16 (Guajira). Ciudad Universitaria, Núcleo Humanístico, Facultad de Humanidades y Educación. Edificio de Investigación y Postgrado. Maracaibo, Venezuela, gdavyvera@gmail.com.

Sep 10, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

George Davy Vera

A personal description of the international counselor education program at the University of Zulia in Venezuela is presented including educational objectives of the counseling degree, various services counselors are trained to provide, and a sample curriculum. This description serves as an example of one international counselor education program that can be used as a model for burgeoning programs in other countries.

Keywords: Venezuela, University of Zulia, international counseling, counselor education, counseling services, curriculum

Venezuela’s early counseling pioneers at the University of Zulia, some of whom were trained in the United States (e.g., Dr. E. Acquaviva, Dr. C. Guanipa, A. Busot, M. Ed.; A. Quintero, M.Ed., M. Socorro, M.Ed., D. Campo, M.Ed.), were pioneers responsible for influencing and crafting the counseling and guidance culture at the University of Zulia. Accordingly, I would like to describe one of the oldest and most well known counseling training programs in Venezuela. This program is chosen because many past and present counseling leaders in Venezuela were educated at the University of Zulia.

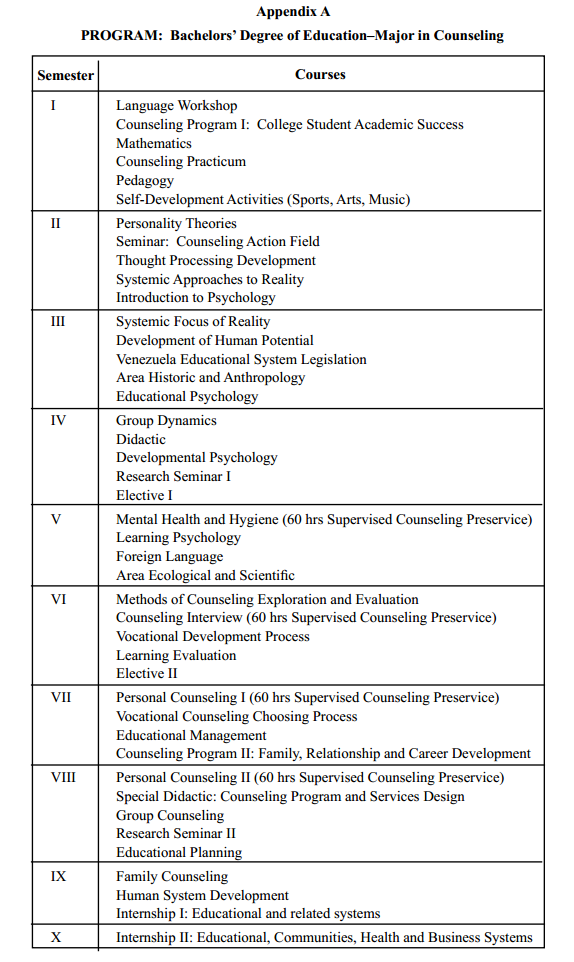

Initially in the early 1970s, this bachelor’s level counseling program was conceived as educational counseling (asesoramiento) and vocational guidance (orientación vocacional) as a specialization track within the major of Pedagogical Science. Graduates from this program received a Licentiate in Education, Major in Pedagogical Sciences in the area of counseling (Licenciatura en Educación, Mención Ciencias Pedagógicas, Area de Orientación). According to the University of Zulia’s official archive (1970-2010) on counseling academic and curriculum development, professional services related to individual, vocational or educational counseling and guidance were understood as orientación. Therefore, the Spanish word was implemented to better communicate the meaning of professional counseling and guidance. Historically, the academic choice of using this term at the time was congruent with the Ministry of Education’s decision in 1962, when the terms orientación and orientador were officially adopted to describe guidance professionals and counseling practitioners, respectively. The current bachelors’ degree is five years long (10 academic semesters, for details see Appendix A).

According to the Academic Updated Curriculum Design (Curriculum Commission of Psychology Department, 1995), the education of professional counselors is conceived upon several key concepts:

• Professional identity reflects that graduates are trained to perform counseling and guidance tasks within the educational system and other professional and organizational agencies.

• Counseling professionals help people develop within the social environment, assist with the processes of psychosocial functioning, and effectively deal with developmental changes and stressful life events.

• Professional counselors trained at the University of Zulia are competent in performing counseling tasks such as:

o designing, implementing, and evaluating counseling services.

o developing prevention or remediation programs emphasizing personal, social, academic, vocational, work, recreational, and community needs at any developmental phase using individual or group strategies.

The main educational objectives of the counseling major are:

1. Diagnosing human system characteristics within the educational, organizational, assistance, judicial, and community contexts.

2. Performing counseling and consultation.

3. Designing, implementing, and evaluating services.

4. Generating research in counseling.

Graduates provide counseling services in different areas of human services:

A. Personal-social counselors help clients deal with issues related to social roles and gain more understanding of themselves within their sociocultural context. The main purpose of the personal-social intervention area is to help clients deal with mental health and personal growth issues and to reach psychological stability. In this area, some helping processes are related to:

• psychological development: self-esteem, decision-making, emotional stability, psychosexual maturity, and intellectual potential.

• social development: interpersonal relationships, work and academic motivation, social adjustment, and ethical values.

• family development: prevention, couples relationships, parents and children, family crisis intervention including divorce, terminal and lifelong sickness, bereavement, and human sexuality.

B. Academic counselors help clients deal with issues related to learning and the role of the learner. Helping processes are related to educational adjustment, academic attitudes, cognitive development, academic performance, and consultation with school teachers, families, and communities.

C. Vocational counselors focus on individual talents, vocational potential and tendencies, as well as roles within the workplace. Vocational counselors’ tasks are mainly focused on several facets, including assessment, decision-making, work development, academic needs, workplace readiness, and positive work attitudes.

D. Work counselors provide counseling services to help individuals and organizations with shared objectives to reach mutual satisfaction and development. This area includes process management, career planning and development, work motivation and communication, work-related decision-making, evaluation, conflict resolution, work-service quality, leadership, performance, and teamwork.

E. Community and recreational counselors provide counseling services for community life enhancement. Counseling processes in this area include community resources and needs, civic practices, positive utilization of recreation and free time, community creativity, organization and planning, cultural and artistic manifestations, and social transformation.

Graduates are trained in three core counseling professional competencies:

• Human system diagnostics: use of diverse tools for diagnosing human systems and individual psychological, educational, social and developmental characteristics.

• Program and service design: conceptualize and evaluate human processes in order to design and administer counseling services for individuals, groups, communities, and organizations.

• Counseling and consultation: provide professional services concerning human potential development and to meet psychological, emotional, behavioral, educational, social, organizational, and community needs.

References

Curriculum Commission of Psychology Department. (1995). Counseling education program. Maracaibo, VZ: University of Zulia.

George Davy Vera teaches in the Counselor Education Program, Universidad de Zulia, Maracaibo, Venezuela. Dr. Vera expresses appreciation to Dr. J. Scott Hinkle for editorial comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Correspondence should be directed to George Davy Vera, avenida 16 (Guajira). Ciudad Universitaria, Núcleo Humanístico, Facultad de Humanidades y Educación. Edificio de Investigación y Postgrado. Maracaibo, Venezuela, gdavyvera@gmail.com.

Sep 9, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

Allison L. Smith, Craig S. Cashwell

Social distance towards adults with mental illness was explored among mental health and non-mental health trainees and professionals. Results suggested mental health trainees and professionals desired less social distance than non-mental health trainees and professionals, and that women desired less social distance than men, with male non-professionals demonstrating the greatest desire for social distance to individuals diagnosed with mental illness. Social distance also is related to attitudes towards adults with mental illness. Implications of such findings are presented.

Keywords: social distance, adult mental illness, mental health professionals, stigma, discriminatory behavior

Stigma has been defined as a product of disgrace that sets a person apart from others (Byrne, 2000). Stigma towards adults with mental illness, defined here as a serious medical condition such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression that disrupts a person’s thinking, feeling, mood, ability to relate to others, and daily functioning (National Alliance on Mental Illness [NAMI], 2009), is both a longstanding and widespread phenomenon (Byrne, 2000; Crisp, Gelder, Rix, Meltzer, & Rowlands, 2000). Researchers seem clear that stigma still exists as a detrimental occurrence in the lives of those diagnosed with a mental illness (Link, Struening, Neese-Todd, Asmussen, & Phelan, 2001; Link, Yang, Phelan, & Collins, 2004; Perlick et al., 2001). In fact, some have argued that the impact of mental illness stigma is so immense that the stigma can be as damaging as the symptoms (Feldman & Crandall, 2007). In the last decade, there have been attempts to highlight to the general population the topic of stigma towards adults with mental illness. For instance, Surgeon General David Satcher spoke in a recent report of the need to recognize stigma as a barrier within the field of mental health. He suggested that mental health care could not be improved without the eradication of mental health stigma (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999).

In the mental illness stigma literature, authors have used the construct of social distance (the proximity one desires between oneself and another person in a social situation) to assess expected discriminatory behavior towards adults with mental illness (Baumann, 2007; Link & Phelan, 2001; Marie & Miles, 2008). Scholars have described low social distance as characterized by a feeling of commonality, or belonging to a group, based on the idea of shared experiences. In contrast, high social distance implies that the person is separate, a stranger, or an outsider (Baumann, 2007). It has been suggested that social distance research can provide valuable insight into factors that influence mental illness stigma (Marie & Miles, 2008).

Social Distance and Non-Mental Health Professionals

Factors that are associated with social distance in the general population towards adults with mental illness have been discussed in the literature (Corrigan, Backs, Edwards, Green, Diwan, & Penn, 2001; Feldmann & Crandall, 2007; Hinkelman & Haag, 2003; Marie & Miles, 2008; Penn, Kohlmaier, & Corrigan, 2000; Phelan & Basow, 2007; Shumaker, Corrigan, & Dejong, 2003). One such factor that has been studied as it relates to social distance is gender, both of the target (person with the mental illness) (Phelan & Basow, 2007) and perceiver (person who desires social distance) (Hinkelman & Haag, 2003; Marie & Miles, 2008; Phelan & Basow, 2007).

Researchers (Marie & Miles, 2008; Phelan & Basow, 2007) have found that women tend to be more willing than men to engage in a relationship with someone diagnosed with depression. Marie and Miles (2008) investigated familiarity of the perceiver with various mental illnesses. A significant main effect was found for gender, with women perceivers rating the characters in vignettes as more dangerous than men participants (Marie & Miles, 2008). Phelan and Basow (2007) found that gender of the target character was a significant predictor of social distance, with female targets being more socially tolerated than male targets. This may be due to the fact that participants perceive male characters in vignettes as more dangerous than female characters. Hinkelman and Haag (2003) also have assessed how gender and adherence to strict gender roles impact attitudes toward mental illness. Interestingly, adherence to strict gender roles rather than gender was related to attitudes about mental illness. Those with strict gender roles were less likely to have positive attitudes. Thus, gender alone did not account for differences in attitudes; instead it was gender roles that related to attitudes towards mental illness.

Social Distance and Mental Health Professionals

Researchers have suggested that stigma also exists among mental health professionals (Lauber, Anthony, Ajdacic-Gross, & Rossler, 2004; Nordt, Rossler, & Lauber, 2006). Lauber et al. (2004) found no significant differences between psychiatrists and the general population on their preferred social distance from people with a mental illness. Both psychiatrists and the general population indicated that the closer the psychological proximity (e.g., allowing the person with mental illness to marry into their family compared to working with someone with a mental illness), the more social distance they desired. Similar results were found when comparing mental health professionals (i.e., psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers, and vocational workers) and the general population regarding social distance attitudes (Nordt et al., 2006). Both professionals and the general public reported many stereotypes about mental illness, and wanted an equal amount of social distance towards a mentally ill character in a vignette. Professionals, however, endorsed to a much lesser degree that adults with mental illness should have restrictions to rights such as voting or marriage. The public significantly accepted the restriction of the right to vote more than each professional group.

Professional Counselors and Social Distance

Although professional counselors might work in the same settings as other mental health professionals, the training background of this subgroup includes some noteworthy differences. Relative to other mental health disciplines, counselor training programs are largely, but not exclusively, grounded in developmental perspectives and strength-based orientations (Ivey & Ivey, 1998; Ivey, Ivey, Myers, & Sweeney, 2005; Ivey & Van Hesteren, 1990) as well as humanistic values and assumptions (Hansen 1999, 2000b, 2003), with a primary focus on the counseling relationship. Given these substantial differences as well as authors’ (Lauber et al. 2004; Nordt et al., 2006) suggestions that it is idealistic to assume that stigma does not exist among mental health professionals, it is important to consider counselors in comparison to other mental health professions and the general public. Further, particular types of counseling programs (clinical mental health counseling or school counseling) might differ when compared to each other on stigma towards adults with mental illness, given the variations of curriculum and clinical training associated with each.

Previous researchers have examined psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, but not professional counselors. Professional counselors should be included in this type of empirical examination, as professional counselors have reported that they are seeing more clients in severe distress (Ivey et al., 2005). Additionally, although attitudes towards mental illness and social distance have been examined in the literature, the relationship between these constructs has not been examined using the current study’s instruments. Further, researchers have not examined simultaneously the attitudes and desired social distance of students. Thus, the purpose of this study was to gain a more comprehensive understanding of social distance by including counselors and counseling students in addition to other mental health professionals and students, non-mental health professionals, and students outside of a mental health discipline.

The following research questions (RQ) were developed to organize this study:

(RQ1) What differences exist in social distance toward adults with mental illness between mental health professionals in-training, non-mental health professionals in-training, mental health professionals, and non- mental health professionals?

(RQ2) What differences exist in social distance toward adults with mental illness between mental health trainees and professionals based on professional orientation (i.e., counseling, social work, or psychology)?

(RQ3) What differences exist in social distance towards adults with mental illness between mental health trainees and professionals based on gender?

(RQ4) What is the relationship between social distance and other attitudes toward adults with mental illness?

Method

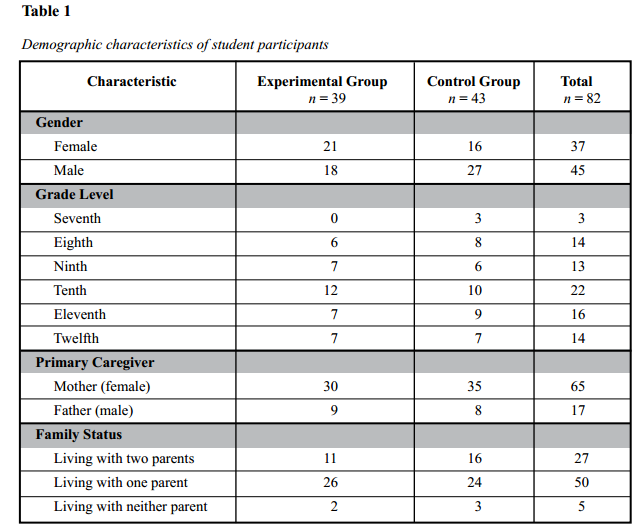

Participants: The total sample included 188 participants. Of these, 62.8% (n = 118) were female and 37.2% (n = 70) were male. The majority of respondents described themselves as Caucasian (89.4%, n = 168) with other participants identifying as African American (4.2%, n = 8), Asian Pacific Islander (2.1%, n = 4), Hispanic (2.1%, n = 4), Multiracial (1.1%, n = 2), and other (1.1%, n = 2). Age of participants ranged from 21 years to 65 years (M = 39.63, SD = 13.23). Response rate of the participants could not be determined, since participants responded to the survey online via a link provided in an email.

The total sample was divided into four subgroups. The first group, the non-mental health student group, included a sample of students (n = 20) who were enrolled in graduate programs in business administration at a mid-sized university in the southeast United States. Business students ranged from 21 to 53 years of age (M = 36.05, SD = 9.19).

A second subgroup included counseling students (n = 17), social work students (n = 20), and psychology students (n = 21). These students were enrolled in master’s level graduate training programs and were in at least their second year of graduate study. Counseling students ranged in age from 21 to 48 (M = 27.94, SD = 5.97). Social work students ranged in age from 22 to 31 (M = 30.45, SD = 8.56). Psychology students ranged in age from 21 to 32 (M = 24.29, SD = 2.72). Three programs of each discipline (counseling, social work, and psychology) at midsized universities in the Southeast United States were used to recruit volunteers. These students comprised the mental health student group.

The third subgroup included 76 mental health professionals who self-identified as counselors (n = 24), social workers (n = 20), or psychologists (n = 32) who were working in the mental health field and had been employed as such for a minimum of one year. Professional counselors ranged in age from 27 to 61 (M = 45.42, SD = 10.79), professional social workers ranged in age from 28 to 64 (M = 53.30, SD = 9.45), and professional psychologists ranged in age from 28 to 65 (M = 47.16, SD = 12.25). Mental health professionals ranged in years of mental health experience from one to 20 years (M = 14.32, SD = 6.25).

The fourth subgroup of interest included 34 non-mental health professionals. These were professionals who were working in a non-mental health field (business) in the southeast United States. Only professional level participants were included in this group to provide some control for education level as a potential confounding influence. Non-mental health professionals ranged in age from 25 to 64 (M = 43.76, SD = 10.62).

Instrumentation

Social Distance Scale. Social distance was measured by a modified version of a Social Distance Scale developed from the World Psychiatric Association Programme to Reduce Stigma and Discrimination Because of Schizophrenia (2001). Gureje, Lasebikan, Ephraim-Oluwanuga, Olley, and Kola (2005) modified this scale to assess social distance regarding attitudes toward mental illness, as the original scale was designed to measure social distance specifically towards adults with schizophrenia. Gureje et al.’s modified version was used in the current study. Six statements assess various levels of intimacy. For example, the first question asks, “Would you feel afraid to have a conversation with someone who has a mental illness?” Answers are given on a 4-point likert-type scale ranging from definitely (1) to definitely not (4). Item scores are added together to get a total social distance score, with high scores indicating less social distance and lower scores indicating more social distance. The Social Distance Scale had sufficient evidence of internal consistency (α= .81) with the current sample.

Community Attitudes Toward the Mentally Ill. The Community Attitudes Toward the Mentally Ill (CAMI; Taylor & Dear, 1981) was used to assess attitudes towards adults with mental illness. The CAMI was developed from the Opinions of Mental Illness Scale (OMI; Cohen & Struening, 1962) and is a 40-item self-report survey that uses a 5-point likert-type scale (5 = “Strongly agree” to 1 = “Strongly disagree”). Four scales are included on the CAMI: Authoritarianism, Benevolence, Social Restrictiveness, and Community Mental Health Ideology. Authoritarianism is defined by the belief that obedience to authority is necessary and people with mental illness are inferior and demand coercive handling by others. Benevolence is defined as being kind and sympathetic, supported by humanism rather than science. Social Restrictiveness involves beliefs about limiting activities and behaviors such as marriage, having children, and voting among people with a mental illness. Community Mental Health Ideology is defined as a “not in my backyard” attitude toward adults with mental illness, or the belief that adults with mental illness should get treatment, but not in close proximity to me (Taylor & Dear, 1981).

Evidence for internal consistency of the CAMI was clear for three of the four scales with the current sample: Community Mental Health Ideology (α= .86), Social Restrictiveness (α= .80), and Benevolence (α= .81). Only the Authoritarianism subscale (α= .62) was problematic in this research.

Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSDS; Crowne & Marlowe, 1960) was included in order to assess the extent to which participants were answering in a socially desirable manner to further validate the attitudes captured by the CAMI and the Social Distance Scale. The MCSDS is the most commonly used social desirability assessment (Leite & Beretvas, 2005) and has demonstrated strong reliability. The original authors obtained a Kuder-Richardson reliability coefficient estimate of .88 (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960). A Cronbach’s alpha of .85 with the current sample provides evidence of reliability with this sample.

Procedure

Potential participants were invited to respond to the survey via electronic email. Email addresses of potential mental health professional participants were obtained from comprehensive statewide lists of the various subgroups of interest. To collect the sample of students, graduate students were contacted via various departmental listservs. Non-mental health professionals were reached through an alumni listserv obtained from a non-mental health training program. Participants were told that the following survey was designed to investigate attitudes towards adults with mental illness. Included in the email was a link to the survey, which was housed at a commercial online site for electronic survey research.

Results

As a preliminary analysis, scores on the Social Distance Scale and the CAMI were correlated with scores on the MCSDS to investigate whether participants were answering in a socially desirable manner. It has been suggested by authors (Leite & Beretvas, 2005) that a low correlation between the Marlowe-Crowne Desirability scale and the scale of interest indicates honest responses. No scores of interest correlated significantly at a .05 level with scores on the MCSDS. This provides evidence that social desirability did not have a substantive role in participant responses and that participants answered questions on the Social Distance Scale and the CAMI with a reasonable level of honesty.

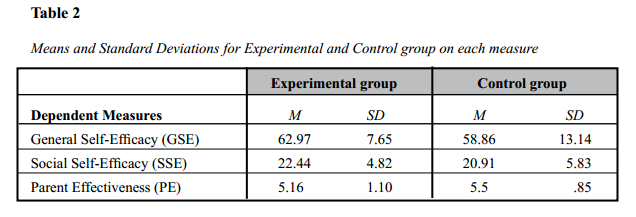

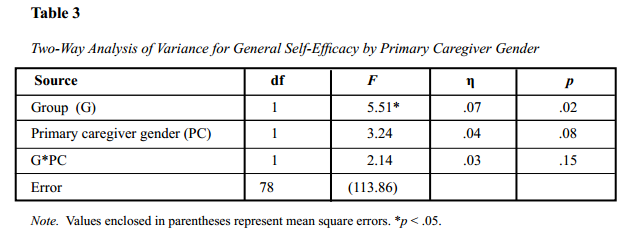

To answer RQ1 and RQ3, a 2 X 2 X 2 ANOVA (professional level [trainee vs. professional] X status [mental health vs. non-mental health] X gender [female vs. male] X Social Distance) was used to investigate the desired social distance toward people with a mental illness. This analysis assessed for main effects based on professional level (trainee vs. professional), main effects based on status (mental health vs. non-mental health), main effects based on gender (female vs. male), and possible interaction effects between professional level, status, and gender. There was a significant main effect found for status F (1, 184) = 16.44, p < .05, η² = .08. Mental health trainees and professionals had higher mean scores on the Social Distance Scale (M = 3.4, SD = .38) than non-mental health trainees and professionals (M = 3.0, SD = .54). Results indicated a main effect for gender F (1, 184) = 6.63, p < .05, η²=.04. Women desired less social distance than men (M = 3.38, SD = .39 vs. M = 3.13, SD = .54) and an interaction effect for gender X mental health status F (1, 184) = 12.17, p < .05, η²=.07. Marginal means revealed that the non-mental health male sub-group was most important in separating the groups. There were no other significant main or interactive effects.

A 2 X 3 ANOVA (professional level [trainee or professional] X professional orientation [counseling, social work, psychology] X Social Distance) was used to investigate the differences in desired social distance. Results indicated that there was a main effect for professional orientation F (2, 184) = 17.67, p < .05, η² =.16. Univariate follow-up analyses indicated that participants with the professional orientation of counselor and psychologist desired significantly less social distance (M = 3.40, SD = .34; M = 3.40, SD = .4, respectively), than those who identified as social worker and non-mental health professional (M = 2.89, SD = .62; M = 3.06, SD = .49).

Finally, although attitudes towards mental illness and social distance have been discussed in the literature (Gureje et al., 2005; Taylor & Dear, 1981), the relationship between attitudes towards mental illness and social distance towards mental illness had not been explored using the CAMI and the Social Distance Scale. Therefore, bivariate correlations were calculated. Because multiple bivariate correlations were being conducted, a more stringent alpha level of .01 was used. There was a significant negative relationship between social distance and Authoritarianism (r (186) = -.52, p < .01) and social distance and Social Restrictiveness (r (186) = -.64, p < .01). There was a significant positive relationship between social distance and Benevolence (r (186) = .51, p < .01) and social distance and Community Mental Health Ideology (r (186) = .60, p < .01).

Discussion

Previous researchers have examined social distance attitudes of mental health professionals and trainees with samples of psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, but not professional counselors. In addition, researchers had not examined simultaneously the attitudes and desired social distance of students. Both the mental health professional group and the mental health trainee group included professional counselors, a group previously excluded from this research.

Authors had suggested that those associated with the mental health field hold the same social distance attitudes towards adults with mental illness as the general population (Lauber et al., 2004; Nordt et al., 2006). Results of the present study suggested that non-mental health trainees and professionals desired more social distance than those associated with the mental health field. This implies that members of the general population hold more negative attitudes toward those with mental illness than mental health professionals and trainees. These results are encouraging and imply that training programs and experience might have a positive effect on reducing social distance towards adults with mental illness. Regarding gender and social distance, a consistent finding in previous research (Marie & Miles, 2008; Phelan & Basow, 2007) suggested that women desired less social distance than men from those diagnosed with mental illness. Results from this study are consistent with those findings.

Since mental illness stigma can be as damaging as the symptoms (Feldman & Crandall, 2007), professional counselors can advocate for adults with mental illness in order to lessen stigma. These messages can be shared with the general population through national groups such as the National Alliance for the Mentally IlI and the National Mental Health Association, as well as through international programs such as the World Health Organization and NBCC International’s Mental Health Facilitator Program. Further, professional counselors might broach the topic of social distance with their clients, as sharing thoughts and feelings related to discrimination as a result of stigma might be therapeutic for those who are dealing with the phenomenon.

Professional orientation was of particular interest in this study. As counselors come from distinct training programs that largely, but not exclusively emphasize developmental perspectives and strength-based orientations (Ivey & Ivey, 1998; Ivey et al., 2005; Ivey & Van Hesteren, 1990), how this subgroup compared to other disciplines was of interest. If there were noteworthy differences in the ways in which professional counselors viewed adults with mental illness, for example, results could serve as an indication that counselor training is indeed unique in the way that professional counselors view clients, as the aforementioned literature has suggested.

Findings suggested that professional counselors and psychologists desired less social distance than both social workers and non-mental health professionals. Despite distinguishing aspects of counselor training (i.e., developmental, strength-based orientation), however, there were no significant differences in attitudes of professional counselors and counselor trainees when compared to those in the psychology field. The lack of difference between counselors and psychologists may be attributed to similarities in training. Alternatively, though, it may be that the types of people drawn to counseling and psychology programs are more similar than different, and that the similarities might not be based on training.

Social work trainees and professionals and non-mental health professionals desired significantly more social distance. This might imply that there are some fundamental differences in the training and coursework of social workers as compared to other professional orientations. For example, it is possible that the focus on macrosystems, more uniquely the purview of social work, leads to an external orientation to change relative to an individual or microsystem approach more common to counseling and psychology. Thus, this focus on larger systems might be a differentiating factor related to proximity to persons with mental illness. Conversely, training and coursework might not be differentiating factors related to social distance. Perhaps students already possess social distance preferences when they enter into mental health training programs.

Of particular interest was how the gender of mental health professionals impacted desired social distance towards adults with mental illness. There was a significant main effect found for status as well as for gender. This finding is consistent with previous literature (Marie & Miles, 2008; Phelan & Basow, 2007) that suggested that women desired less social distance than men from those diagnosed with mental illness. In addition, there was an interaction between the two variables. The social distance scores of women were highly similar between mental health professionals and non-mental health professionals. For men, however, there was a substantive gap based on status. Men who were not mental health professionals desired the highest level of social distance. Although there is a within-group difference, this suggests that targeted advocacy efforts might be tailored to men in the general population who seem to desire a greater social distance from people diagnosed with mental illness.

This study looked at social distance attitudes of participants as one group in order to explore the relationship social distance had with other attitudes towards mental illness. It seems that social distance and other attitudes towards mental illness are related. All correlations were in the hypothesized direction. There was a significant negative relationship between social distance and both Authoritarianism and Social Restrictiveness. There was a significant positive relationship between social distance and both Benevolence and Community Mental Health Ideology. This is because higher social distance scores indicate less social distance while higher mean scores on the CAMI indicate more of each attitude. Scores on the more negative attitude subscale of the CAMI, such as Authoritarianism and Social Restrictiveness were related to more social distance, while more positive attitudes on the CAMI such as Benevolence and Community Mental Health Ideology were related to less social distance.

This implies that social distance, or proximity to adults with mental illness, can be related to attitudes. People who hold more negative attitudes towards mental illness, such as Authoritarianism (belief that people with mental illness are inferior) and Social Restrictiveness (limiting the rights for people with mental illness) might manifest this in behavior such as the desire for more social distance. More positive attitudes towards mental illness such as Benevolence (a kindly or sympathetic attitude towards mental illness) and Mental Health Ideology (the belief that mental illness deserves treatment but “not in my back yard”) are related to the desire for less social distance. Those who hold a more positive attitude towards adults with mental illness will tend to be more comfortable with situations such as working at the same place of employment or maintaining a friendship with someone with a mental illness. Since the two constructs are related, perhaps advocacy efforts need to be geared towards both attitudes and social distance in order to combat mental illness stigma. For example, only focusing on attitudes might miss the proximity associated with stigma toward an adult with mental illness. These efforts might especially be geared towards those in the general population, since this study suggested that non-mental health professionals and students desired the most social distance.

Mental health professionals of any type can begin to consider social distance as it relates to attitudes towards adults with mental illness, since the construct of social distance can be used to assess expected discriminatory behavior towards adults with mental illness (Baumann, 2007; Link & Phelan, 2001; Marie & Miles, 2008). As well, professional counselors might begin to explore their own comfort level with proximity and closeness to adults with mental illness, since it relates to attitudes. Counselor educators might consider including people with mental illness as a marginalized group in multicultural training and challenging students to examine their knowledge and self-awareness related to mental illness. Although results of this study suggested that mental health professionals desired less social distance than those in the general population, other recent research has suggested that it would be too simplistic to assume that mental health professionals do not indeed hold stigmatizing attitudes (Nordt et al., 2006).

Limitations and Future Directions

As with all research, the current study has limitations that both contextualize the findings and provide direction for future research efforts. First, replication with larger and more diverse samples is warranted. It is unknown the extent to which respondents in this study differ from non-respondents. In particular, it is possible that there is a systematic bias (either positive or negative) among those who chose to respond to the study request. Future researchers should include a more racially diverse sample, as these findings are based on the responses of participants who largely identified as Caucasian.

Additionally, replication and extension efforts are warranted that use alternative methods of measuring social distance, which is important for at least two reasons. First, the current study relied solely on self-report and, although responses were not overly influenced by social desirability, it is unknown to what extent a mono-method bias exists. Future researchers could use other methods of assessing social distance to account for this potential bias. Furthermore, the present study is limited because of the cross-section scope of the data. Scholars interested in social distance might longitudinally examine mental health trainees before and after training to better understand the developmental nature of social distance and stigma towards adults with mental illness. Specifically, it would be useful to know what types of experiences impact one’s desired social distance and stigma. Such a longitudinal study also would provide information about whether mental health trainees enter their training program already desiring less social distance than the general population. While previous researchers explored attitudes towards mental illness before and after a single course during mental health training, thus assuming attitude changes were a result of the course, future research might survey students at the beginning of the training program, before starting any coursework, and at the end of training in order to investigate social distance over time. If desired proximity remains the same, this might imply that mental health students naturally possess less stigmatizing attitudes and are drawn to helping professions rather than assuming that low levels of desired social distance are an artifact of training. Further, future research could examine different types of counseling students, so that any differences related to particular types of counseling programs (i.e., clinical mental health counseling or school counseling) would be revealed. Given the variations of curriculum and clinical training associated with each, differences in attitudes might suggest attitude changes as a result of curriculum and training.

The topic of gender and social distance may be an area for continued study. Qualitative designs might assist researchers in gaining a deeper understanding of desired social distance of men and women, and whether gender is most important in understanding desired social distance with adults with mental illness. Depending on themes that might arise related to social distance, counselors can aim advocacy efforts and anti-stigma campaigns to assist with this.

Conclusion

Many people have attempted to highlight to the public that stigma towards adults with mental illness is as damaging to those diagnosed as the illness itself. Missing, however, is a comprehensive understanding of the stigma process. In this study, the focus was on social distance as it relates to stigma towards adults with mental illness. Factors such as mental health training, professional orientation, and gender seem to result in differences related to social distance. Individuals not associated with the mental health field continue to have mental illness stigma, as previous research suggested. Results of the current research can assist in a deeper understanding of the factors involved in the phenomenon. With a deeper understanding of social distance and stigma, practitioners can create advocacy efforts and targeted interventions with the overall goal of eradicating mental illness stigma.

References

Baumann, A. E. (2007). Stigmatization, social distance and exclusion because of mental illness: The individual with mental illness as a ‘stranger.’ International Review of Psychiatry, 19, 131–135.

Byrne, P. (2000). Stigma of mental illness and ways of diminishing it. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 6, 65–72.

Cohen, J., & Struening, E. L. (1962). Opinions about mental illness in the personnel of two large mental hospitals. Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology, 64, 349–360.

Corrigan, P. W., Backs Edwards, A., Green, A., Lickey Diwan, S., & Penn, D. L. (2001). Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 27, 219–225.

Crisp, A., Gelder, M., Rix, S., Meltzer, H., & Rowlands, O. (2000). Stigmatisation of people with mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 4–7.

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24, 349–354.

Feldman, D. B., & Crandall, C. S. (2007). Dimensions of mental illness stigma: What about mental illness causes social rejection? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 137–154.

Gureje, O., Lasebikan, V., Ephraim-Oluwanuga, O., Olley, B., & Kola, L. (2005). Community study of knowledge of and attitude to mental illness in Nigeria. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 436–441.

Hansen, J. (1999). A review and critical analysis of humanistic approaches to treating disturbed clients. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education, and Development, 38, 29–38.

Hansen, J. (2000a). Mental health counseling: Comments on the emerging identity of an adolescent profession. Journal for the Professional Counselor, 15, 39–51.

Hansen, J. (2000b). Psychoanalysis and humanism: A review and critical examination of integrationist with some proposed resolutions. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78, 21–28.

Hansen, J. (2003). Including diagnostic training in counseling curricula: Implications for professional identity development. Counselor Education & Supervision, 43, 96–107.