Feb 9, 2015 | Article, Volume 5 - Issue 1

Mary-Catherine McClain, Robert C. Reardon

In this article, the authors analyze ways of categorizing civilian occupations and employment data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau over 6 decades (1960–2010) with respect to six kinds of work (Holland’s RIASEC classification), occupational titles used, employment and income. O*NET provided data for the 2010 census regarding employment and income. The authors discuss the distribution of employment changes over time and the examination of findings in relation to science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields. The article concludes with practical implications for counseling and guidance practice.

Keywords: Holland, RIASEC, census, employment, occupations, income

Holland’s (1997) RIASEC theory is generally recognized as one of the most important and influential in the field of counseling and career development. Foutch, McHugh, Bertoch, and Reardon (2014) sought to verify such an observation by using bibliographic research tools and identified all publications based on this theory from 1953–2011. They found over 1,970 reference citations to Holland’s theory and applications, and categorized them in terms of practice, specific populations (e.g., K–12), instruments, diverse populations and theory. These citations appeared in 275 publications (e.g., books, journals, periodicals, reports) produced in varied professional fields and disciplines worldwide.

Many counselors know relatively more about Holland’s RIASEC personality typology than corresponding environmental models (Reardon & Lenz, 1998). From the outset, Holland believed that the environmental aspects of the typology needed further examination (Weinrach, 1980). Occupations, fields of study or academic disciplines, organizations, leisure activities, and jobs (positions) are aspects of the environment included in the theory. In this article, we address the interaction between RIASEC theory and the environment by examining 2010 census data and updating prior studies of occupational employment in 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990 and 2000 in relation to RIASEC codes and Holland’s theory (Reardon, Bullock, & Meyer, 2007).

Various people contemplating career decisions can benefit from understanding the scope and nature of the labor force and employment from this psychological, counseling-based point of view. Moreover, given characteristics of the contemporary U.S. economy, it is important to know how the distribution of jobs is changing over time. For example, the distribution of jobs across the RIASEC categories has changed from 1960–2010 in some ways, but not in others. An analysis of occupational employment, then, can be beneficial to counselors and career services providers assisting those who are unemployed, displaced or exploring the labor force. This work is important for both theoretical and practical reasons. For example, the number of annual job openings is strongly related to the number of people currently working in an occupation, so knowing the number employed is of practical importance in job hunting because of the need to replace workers.

Authors of recent literature have identified concerns about the use of outmoded concepts such as occupation in career/life counseling at a time of unprecedented socioeconomic change in the global economy. For example, Savickas et al. (2009) noted that new social arrangements for work and the digital revolution have led to unstable occupations and frequent job transitions for individuals: “Today, occupational prospects seem far less definable and predictable, with job transitions more frequent and difficult” (Savickas et al., 2009, p. 240). Sampson and Reardon (2011) summarized these ideas: “Occupations have changed in fundamental ways as technology and globalization have reshaped the workplace. Occupations have become fluid and organizations are evolving rapidly, adapting their workforce to respond to a rapidly evolving marketplace” (p. 41). We agree that some occupations are changing but conclude that the concept of an occupation remains common and useful in the social sciences as a way of categorizing work activities and employment.

In contrast to this view, Murray (2012) suggested that the workplace has not transformed for the 82% of American workers in occupations other than managerial professional positions. Teachers, police, plumbing contractors, insurance agents and carpenters have the same duties and routines that these occupations have always required, although some of the work tasks may have been affected by technology. Sampson and Reardon (2011) noted that the perception of massive occupational change has been exacerbated by inaccuracies in media presentations and the failure to use career theory to examine occupational changes.

In the present article, we examine occupational information using Holland’s (1997) RIASEC theory. This theory rests on four basic assumptions: (a) individuals can be categorized into Realistic (R), Investigative (I), Artistic (A), Social (S), Enterprising (E) and Conventional (C) types; (b) environments (i.e., occupations) also can be categorized into these same six types; (c) individuals tend to choose environments that fit their personality types; and (d) behavior is determined by the fit between an individual’s personality and environment. Examination of the occupational titles used to describe current work in the United States, including information about employment and income, can increase understanding of the workplace from this theoretical perspective.

Holland’s (1997) typological theory specifies a theoretical connection between vocational personalities and work environments that makes it possible to use the same RIASEC classification system for both persons and occupations. Many inventories and assessment tools also use the typology to enable individuals to categorize their interests and personal characteristics in terms of the six types and combinations of the types. These six types are briefly defined as follows:

- Realistic (R) types are found in occupations such as auto mechanic, surveyor, electrician and farmer. The R type usually has mechanical and athletic abilities, likes to work outdoors and with tools and machines, and might be described as conforming, hardheaded, honest, humble, materialistic, practical and thrifty.

- Investigative (I) types like occupations such as a biologist, chemist, geologist, anthropologist and medical technician. The I type usually has math and science abilities, and likes to work alone and to solve problems. The I type might be described as analytical, critical, curious, independent, intellectual, pessimistic and rational.

- Artistic (A) types are found in occupations such as musician, dancer, interior decorator, actor and writer. The A type usually has artistic skills, enjoys creating original work and has a good imagination. The A type may be described as disorderly, emotional, idealistic, imaginative, impulsive, independent, introspective and original.

- Social (S) types like occupations such as teacher, speech therapist, counselor, clinical psychologist and nurse. The S type generally likes to help, teach and counsel people, and may be described as friendly, generous, helpful, idealistic, kind, responsible, tactful, understanding and warm.

- Enterprising (E) types like occupations such as buyer, sports promoter, business executive, salesperson, supervisor and manager. The E type usually has leadership and public speaking abilities, is interested in money and politics, and likes to influence people. The E type is described as acquisitive, ambitious, domineering, extroverted, optimistic, self-confident and sociable.

- Conventional (C) types are found in occupations such as bookkeeper, financial analyst, banker and secretary. The C type has clerical and math abilities, likes to work indoors and to organize things. The C type is described as conforming, efficient, obedient, orderly, persistent, practical and unimaginative.

The six RIASEC types are optimally represented by a circular order, also commonly referred to as the hexagonal model. Holland’s (1997) structure of the six types as a hexagon is one of the most well-replicated findings in the history of vocational psychology (Rounds, 1995). The six domains are arranged according to their relative similarity in a hexagonal formation of R-I-A-S-E-C. For example, according to Holland’s theory, the Social and Enterprising types appear in adjacent positions on the hexagon because they are alike; in contrast, the Social and Realistic types are dissimilar and appear in opposite positions from one another on the hexagon.

Prior Studies

In the early 1970s, researchers began to examine the U.S. labor market using the RIASEC classification system (Reardon et al., 2007), and the present study is a continuation of that line of research. Using data provided by the decennial census in 1960, 1970 and 1980, researchers (G. D. Gottfredson & Daiger, 1977; G. D. Gottfredson & Holland, 1996; G. D. Gottfredson, Holland, & Gottfredson, 1975; L. S. Gottfredson, 1978; L. S. Gottfredson, 1980; L. S. Gottfredson & Brown, 1978) analyzed U.S. employment patterns using Holland’s theory. These studies examined a number of variables with respect to the Holland RIASEC classification, including the percentages of men and women working in hundreds of occupations, salaries earned during the preceding year by incumbents, educational and training levels associated with occupations, occupational prestige, and the education levels or cognitive complexity ratings for occupations. These studies provided practitioners and scholars with more theory-based, detailed information about work environments and the characteristics of workers.

After a 15-year hiatus in research on census employment and Holland codes, Reardon, Vernick, and Reed (2004) analyzed the 1990 census data in relation to data from 1960, 1970 and 1980. They considered the variables of gender, income and cognitive complexity and reported stability in the census data for occupational titles and six kinds of work from 1960–1990. For example, the Realistic area included many more named occupations in the census than the other five areas, averaging between 46% and 50% of all named occupations over the 40-year period.

Reardon et al. (2004) found that while employment declined by 18% in the Realistic area relative to other Holland types, it remained the largest area of employment and actually increased in real numbers through 1990. Only 1% of employment was in the Artistic area. Reardon et al. (2004) also reported marked differences in employment between men and women across the six areas from 1960–1990. Reardon et al. (2004) further examined income and gender by six kinds of work and found that the average income profile ranging from highest to lowest was IESARC. The discrepancy across the six areas was very large, with the average Investigative income being two times the average Conventional income.

In a later study, Reardon et al. (2007) examined trends in labor market characteristics using census data from 1960–2000. They found stability in occupational constructs for six kinds of work from 1960–2000; for instance, the Realistic area included many more named occupations in the census than the other five areas, ranging between 43% and 50% of all occupations included over the five census periods. Reardon et al. (2007) reported that although employment in the Realistic area declined by 25% from 1960–2000, this area remained the largest area of employment and actually increased in real numbers from 1960–2000. As before, only 1% of employment was in the Artistic area. Finally, Reardon et al. (2007) examined income and gender by kinds of work and found that the average income profile for six kinds of work ranging from highest to lowest was IESARC in 1990 and ISEARC in 2000. The discrepancy across the six areas was very large, with the average Investigative income about twice as large as the average Conventional income.

In summary, the data included in these studies (Reardon et al., 2007; Reardon et al., 2004) were unique in several ways and have special implications for counselors. First, as an independent branch of the federal government, the U.S. Census Bureau reported actual numbers of people working in different occupations based on an accounting of persons in households. Second, these data provided a retrospective look at the labor markets, and by examining them over time it was possible to view changes in the economic lives of persons in the United States. Third, the occupational titles included in the census have remained constant over the years, reinforcing the use of the occupational schema in matching persons and environments. Fourth, these studies were conducted by researchers in the counseling field rather than economists or sociologists, which helps counselors use occupational data organized by Holland codes to illustrate and explain where jobs exist in relation to their clients’ interests. For example, a client may have a strong interest in Artistic occupations, and census data may help a counselor explain the relatively small number of persons working in Artistic fields.

The Present Study

We examined the employment trends reported in earlier research and added a new analysis based on the 2010 census and O*NET data. Research questions included the following:

- What were the numbers of occupational titles reported in the census from 1960–2010 relative to the six areas of work?

- What were the numbers and percentages of occupational employment in 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2010 in relation to six kinds of work?

- What were the mean incomes for six different kinds of work in 1990, 2000 and 2010?

Methods

Procedures and Research Tools

Varied procedures have been used to collect occupational data for the decennial census over the past 6 decades.

1960, 1970, 1980 census. In the 1960 census, the sampling unit was the housing unit, or the person in the case of group housing. This method provided information about 297 detailed occupational categories. L. S. Gottfredson and Brown (1978) described the methods they used to derive Holland codes for the 1960 census data using 1970 census data as a point of reference. In the 1970 census, the sampling unit again was the housing unit, and 440 detailed occupational titles were included in these data, 143 more than in 1960. As with the 1960 census, the data included only employed persons and excluded members of the armed forces. G. D. Gottfredson, Holland, and Gottfredson (1975) analyzed data from the 1970 census involving 424 occupations, and excluded men (5.6%) and women (6.6%) not classified according to one of the detailed occupations. Information about the 1980 census was taken primarily from G. D. Gottfredson and Holland (1989) and G. D. Gottfredson (1984). The 1980 analysis was based on 503 selected occupations.

1990 census. Comprehensive information about the 1990 census was provided by the U.S. Census Bureau (1992a, 1992b), and was based on 500 selected occupations. G. D. Gottfredson and Holland (1996) indicated that this classification was most closely related to the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC; U.S. Department of Commerce, 1980). The U.S. population count in 1990 was 283,928,233 (U.S. Census Bureau, 1992b). Four new categories of work were added to the 1990 census while six from the 1980 census were eliminated.

2000 census. The 2000 census counted 281,421,906 people in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. As in the past, short and long forms were used with about 17% (1 in 6 households) receiving the latter (U.S. Census Bureau, 2002). The 2000 census included 471 occupations classified using the SOC (U.S. Department of Labor, 2000).

2010 census. The 2010 census counted 308,745,538 people in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. This census included 539 occupations, including those with “all other” titles representing occupations with a wide range of characteristics not fitting into one of the O*NET detailed occupations. However, as in prior studies, the focus was on the detailed occupations in the 2010 census (N = 494) and excluded military-based occupations.

The information collected in the 2010 census was based on the short form rather than the long form, which means that demographic information about gender, salary and age was not collected relative to occupations. Lowe (2010) noted that the introduction of the American Community Survey by the U.S. Census Bureau provided the most sweeping change in census data collection in 60 years. The American Community Survey is a nationwide, continuous survey designed to provide reliable and timely demographic housing, social and economic data every year, in contrast to the long form, which provided data only at the beginning of each decade.

After locating the 2010 census data from the U.S. Census Bureau with lists of occupations categorized with census and SOC codes, we organized the information into a spreadsheet using the following headings: Occupation 2010 category description (e.g., management occupations), Occupation (e.g., chief executive), 2010 Census Code (e.g., 0010) and 2010 SOC Code (e.g., 11-1011). Additional columns were created to incorporate Holland code information for 2010 employment data and mean annual wages. The SOC (U.S. Department of Labor, 2010) was used to collect employment and salary information from the O*NET system (http://online.onetcenter.org/). O*NET is a comprehensive database that provides information on 780 occupations, worker skills and job training requirements. O*NET is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Employment and Training Administration. The Self-Directed Search Occupations Finder—Revised Edition (OF; Holland & PAR Staff, 2010) and the Dictionary of Holland Occupational Codes (DHOC; G. D. Gottfredson & Holland, 1996) also were used to obtain the first-letter Holland code for each specific occupation. Employment data and mean annual wages for census occupations were found in O*NET.

A Note about Data Analysis

Previous studies of employment using census data and Holland codes have reported frequency and percentage distributions, and this study continued that approach. As earlier researchers have noted (G. D. Gottfredson & Daiger, 1977), the sample sizes are so large that the magnitude of observed differences is more important than statistical differences. Rounded numbers are used in this report to the nearest percent or thousand in order to avoid communicating a misplaced sense of precision in the findings.

Results

Occupational Titles in the Census for Six Kinds of Work, 1960–2010

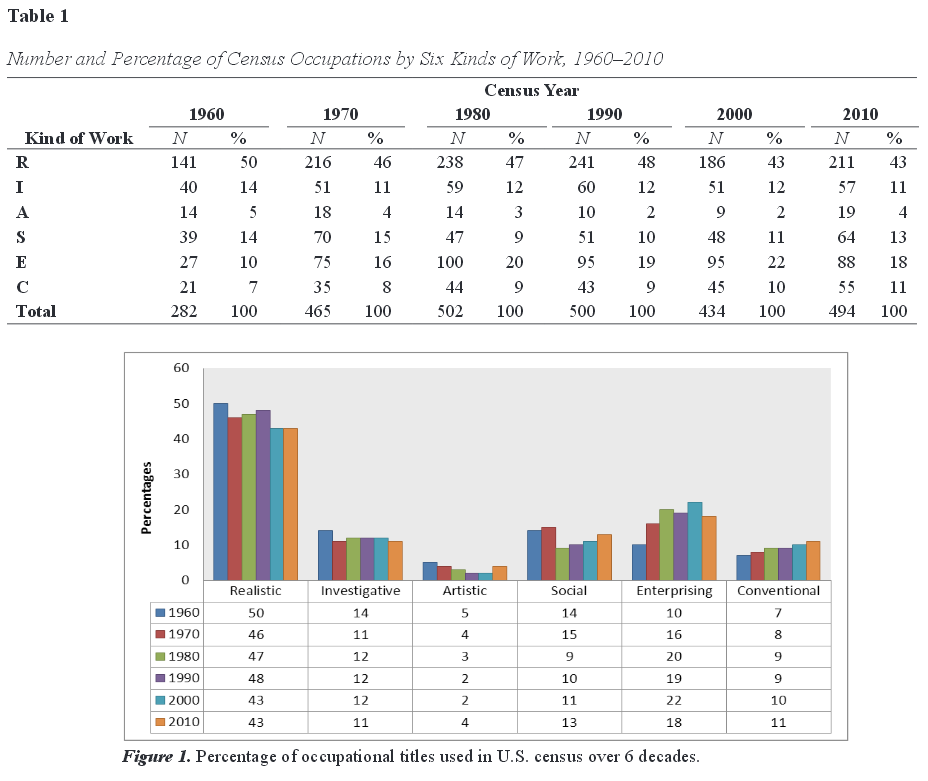

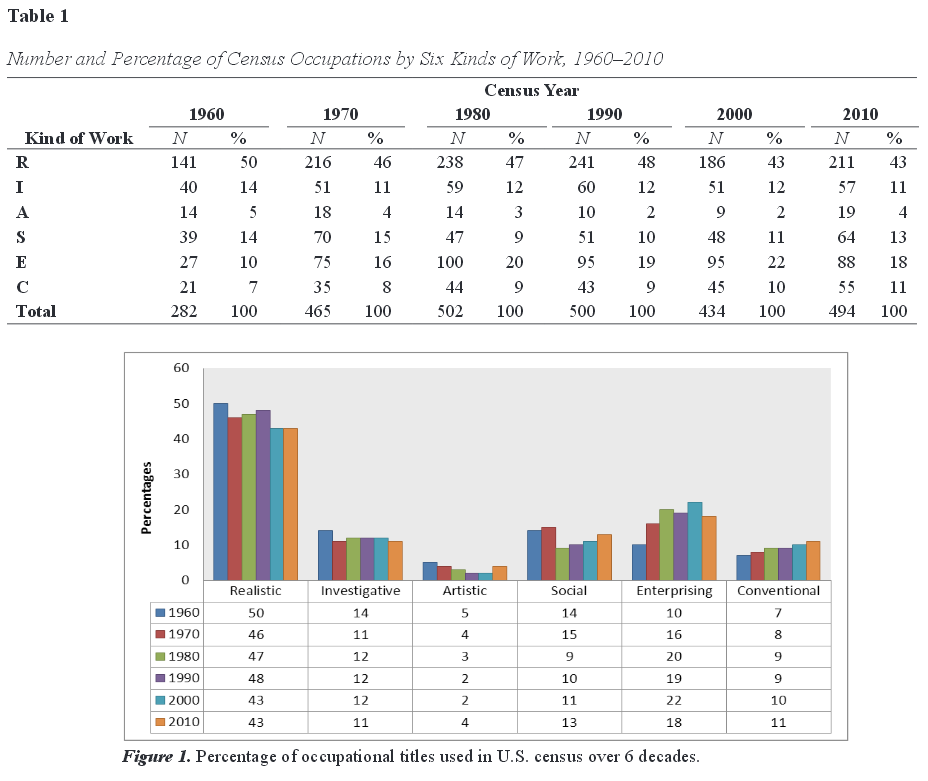

For the first question, we examined the number of occupational titles used in the census and O*NET, and categorized these in relation to the six areas of work. Occupational titles provide schemas for career exploration using Holland’s (1997) RIASEC codes—tools for the exploration and examination of occupational information. As in previous studies (Reardon et al., 2007), the Realistic area included many more named occupations in the census than the other five areas (see Table 1, updated with 2010 data). For example, the 2010 census specified 211 occupations in the Realistic area and 283 occupations in the other five areas combined. Only 19 occupations were identified in the Artistic area. Overall, occupations in the Enterprising area increased from 27 in 1960 to 88 in 2010. Finally, 282 occupations were included in the 1960 analysis, which increased to 465 in 1970, 502 in 1980 and 500 in 1990, dropped to 434 in 2000, and increased again to 494 in 2010.

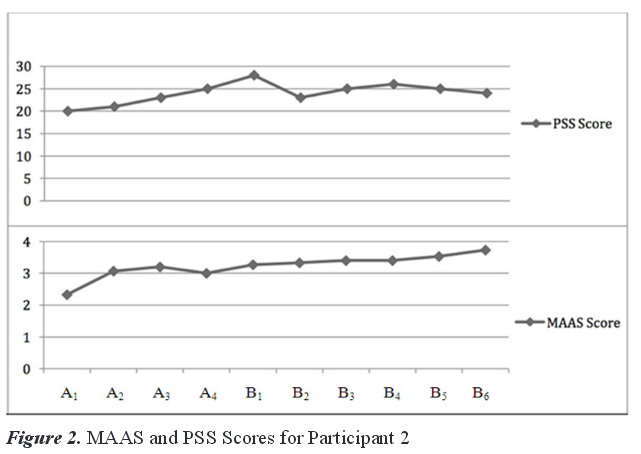

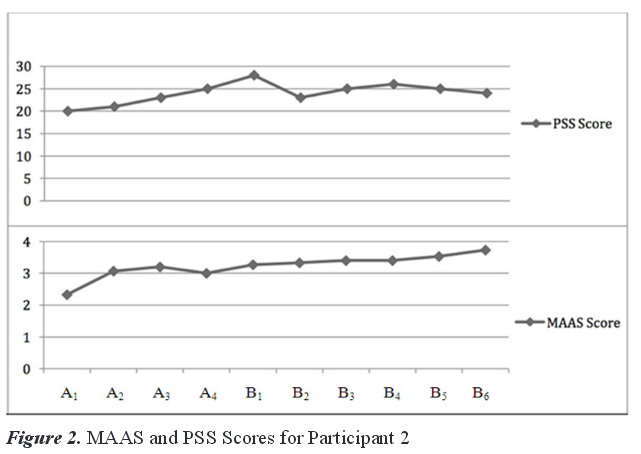

Table 1 also shows that occupational titles were not equally distributed across the six areas of work over the past six decades and have changed very little during this period. For example, the Realistic area consistently has the most occupational titles and the Artistic area the fewest. Figure 1 shows the average percentages of occupational titles in the census across six decades, as follows: Realistic 46%, Investigative 12%, Artistic 3%, Social 12%, Enterprising 18% and Conventional 9%. This distribution is similar to what was found in 2010: Realistic 43%, Investigative 11%, Artistic 4%, Social 13%, Enterprising 18% and Conventional 11%. Figure 1 shows in graphic form that the schemas used to describe work activities in the U.S. economy have remained relatively stable over 6 decades.

Employment in Six Kinds of Work, 1960–2010

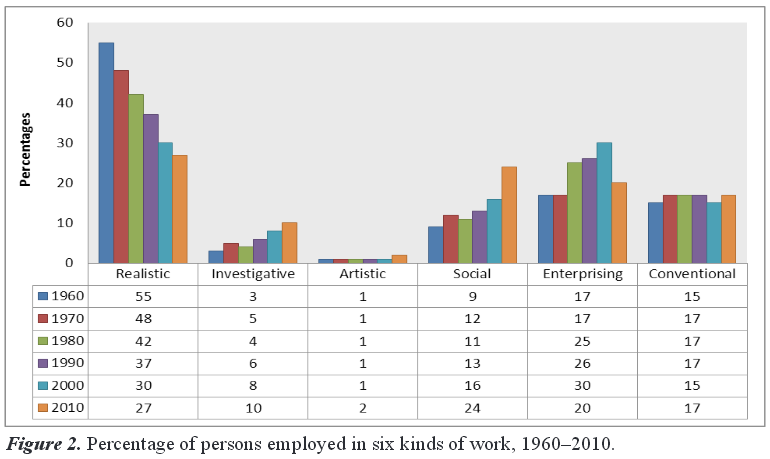

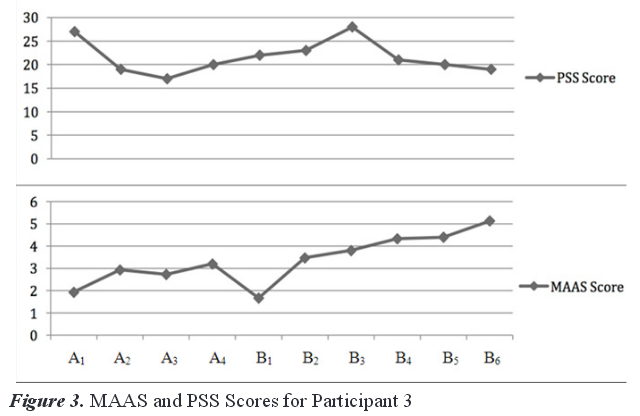

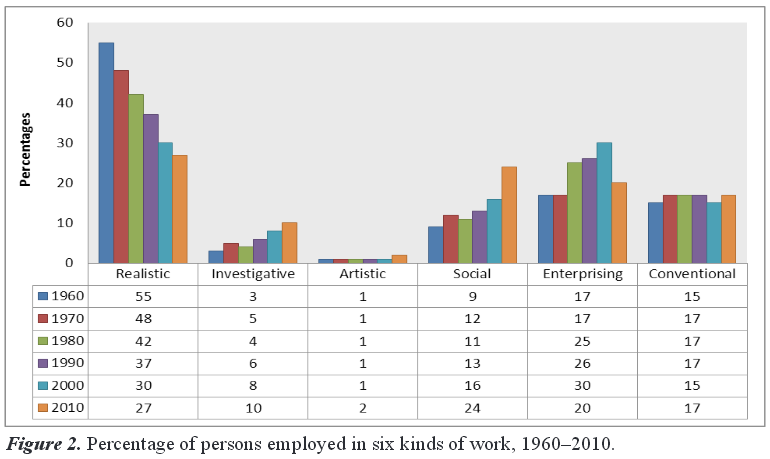

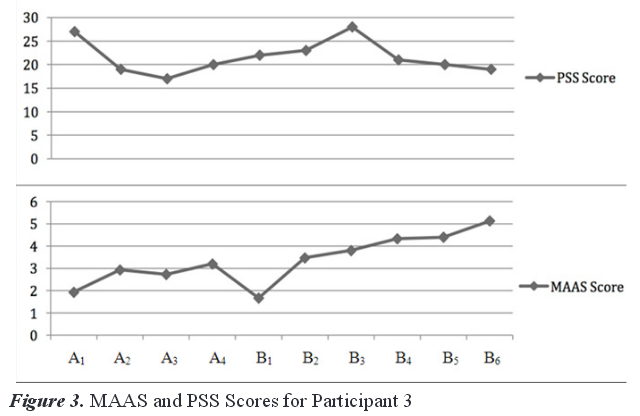

In analyzing U.S. employment data over 6 decades, we focused on the detailed occupations as in previous census studies (Reardon et al., 2007). Table 2 indicates that the total estimated employment increased over the 6 decades from 64.1 million in 1960 to 119.8 million in 2010. Table 2 and Figure 2 reveal that the percentage of Realistic employment declined 28% from 1960–2010, an average of about 4.7% for each decade. However, and in spite of this decline, the Realistic area showed that 31.9 million persons were employed in 2010, and the Realistic area had the highest level of employment across the six RIASEC areas in each census period. The Artistic area had the fewest number employed in 2010 with 2.0 million. Table 2 and Figure 2 show that the percentage of employment in the Social area increased from 9% in 1960 to 24% in 2010, or 5.6 million to 29.6 million persons. During the same period, employment in the Investigative area increased from 3% in 1960 to 10% in 2010, or 2.0 million to 11.5 million persons. Employment in the other four areas remained more stable. Figure 2 graphically shows that the RIASEC employment profile for highest to lowest areas was RSECIA in 1960 compared to RECSIA in 2010. The Realistic, Investigative, and Artistic areas maintained their positions over this time period.

Table 2

Number and Percentage of Persons Employed in Six Kinds of Work, 1960–2010

|

Census Year (Detailed Occupations)

|

|

| Kind of Work |

1960a |

1970a |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

35,029

|

34,342

|

42,253

|

42,711

|

36,700

|

31,868

|

|

55%

|

48%

|

42%

|

37%

|

30%

|

27%

|

| I |

1,986

|

3,690

|

4,169

|

6,738

|

9,315

|

11,457

|

|

3%

|

5%

|

4%

|

6%

|

8%

|

10%

|

| A |

756

|

975

|

1,277

|

1,552

|

1,622

|

2,027

|

|

1%

|

1%

|

1%

|

1%

|

1%

|

2%

|

| S |

5,611

|

8,390

|

10,815

|

14,983

|

18,821

|

29,563

|

|

9%

|

12%

|

11%

|

13%

|

16%

|

24%

|

| E |

11,106

|

12,153

|

25,920

|

29,668

|

35,946

|

23,991

|

|

17%

|

17%

|

25%

|

26%

|

30%

|

20%

|

| C |

9,569

|

12,658

|

17,540

|

20,086

|

18,574

|

20,878

|

|

15%

|

17%

|

17%

|

17%

|

15%

|

17%

|

| Total |

64,057

|

72,208

|

101,974

|

115,738

|

120,978

|

119,784

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. Employment numbers are in millions rounded to the nearest thousand.

aUsed by permission of Academic Press Inc., Journal of Vocational Behavior, 10, p. 131. Copyright 1977 Academic Press Inc.

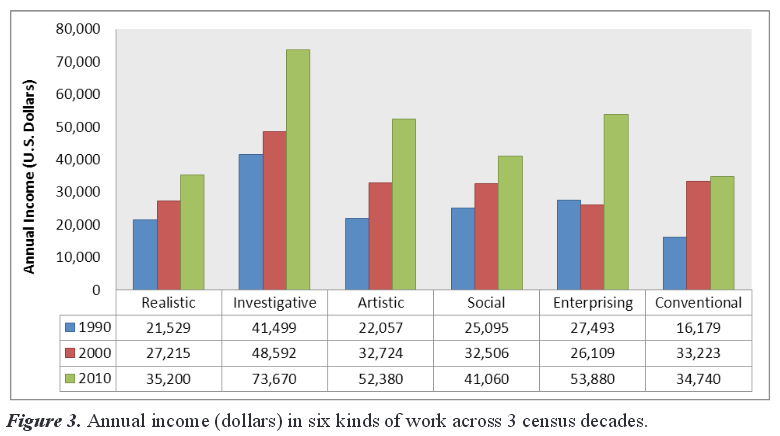

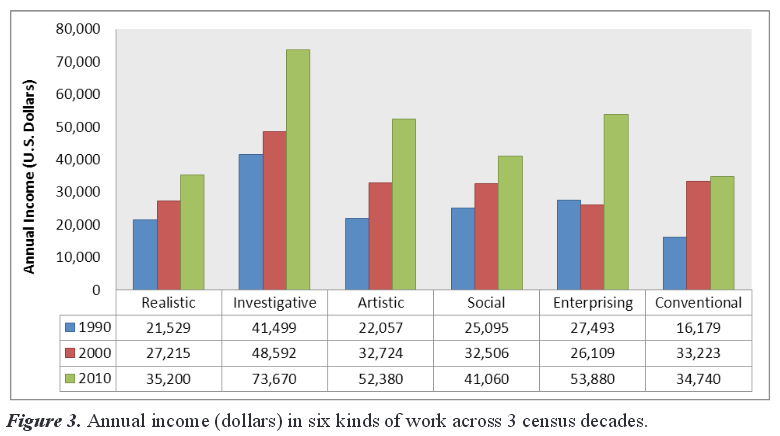

Income and Kinds of Work, 1990–2010

For the third question, we focused on mean income levels for persons employed in six kinds of work in 1990, 2000 and 2010. Inspection of Figure 3 shows the results of this analysis. These data reveal the continued discrepancy with regard to income among the Holland types across the three most recent census periods. The RIASEC profiles for highest to lowest income were IESARC, ISEARC and IEASRC in 1990, 2000 and 2010, respectively. The Investigative area consistently showed the highest income levels over the 3 decades, while the Conventional and Realistic areas tended to show the lowest. The average income over the 3 decades for the Investigative area was $54,587, compared to Conventional, $28,047 and Realistic, $27,981. Data in Figure 3 continue to show wide variations in income levels among the six RIASEC groups. For example, in 2010 the income in the Investigative area was almost double that of the Conventional area.

Discussion

The principal findings of this study are examined in terms of the three questions that guided the research, followed by a discussion of the study’s limitations and implications for counseling practice.

Occupational Titles by RIASEC Code

Information about jobs and employment used in counseling may be affected by the uneven distribution of occupational titles describing work across RIASEC areas. Over 60% of the titles used in 2010 were in the Realistic and Enterprising areas, and this distribution has been consistent over the past 6 decades. It is noteworthy that the percentages of occupational titles in the Investigative and Conventional areas in 2010 were the same, but the income reported across the six areas was the most discrepant between these two areas. Labor market information across the six areas is not always equivalent.

G. D. Gottfredson and Holland (1989) reported that the Dictionary of Occupational Titles also showed variations in the distribution of RIASEC codes for occupational titles. They were interested in the number of times each RIASEC letter appeared somewhere in the three-letter code for each occupation in the Dictionary of Occupational Titles and reported the following: Realistic, 10,708 times; Investigative, 2,551; Artistic, 570; Social, 6,606; Enterprising, 10,405; and Conventional, 5,999. These data reveal that upon examining the world of work from a RIASEC perspective, counselors can obtain a theory-based view of work environments that is not equitable across the six areas. Counselors can use RIASEC codes to inform clients about work and to increase their understanding of occupations and employment.

Information about jobs and employing organizations changes more frequently than information about occupations (e.g., typical work duties, training requirements, working conditions; Reardon, Lenz, Sampson, & Peterson, 2012). Perhaps lessons from the field of general semantics (Johnson, 1946) can be useful here. For example, the word chair can communicate information about the arrangement of furniture in a room, but this word does not communicate everything known about chairs, which in reality may take many different forms and be built of varied kinds of materials. The same is true for occupational terms. There are many different carpenters working in varied job positions and for varied employers, but the term carpenter still has meaning in communications because it is generally understood that not all carpenters are the same.

Over the 6 decades of this analysis, the number of census occupations in each RIASEC area has been relatively static. This stability indicates that there is considerable permanence in the array of the named occupations in the census reports about the workforce. This finding is contrary to the observations by Savickas (2012) and Savickas et al. (2009) regarding instability of the concept of an occupation in the contemporary global economy.

Employment in Six Areas of Work

The findings of this study report both the numbers of persons employed and the percentages of employment across RIASEC areas for six census periods. We believe that information about employment in the past can be instructive for future career planning. Table 2 reports the numeric and percentage changes in employment over 6 decades. The table shows the actual number of persons employed according to the decennial censuses over the 60-year period. This table and Figure 2 show the percentage changes—the distribution of the workforce within the RIASEC categories. Occupations that employ the largest numbers of people are in the Realistic, Social and Enterprising areas, with less employment in the Investigative and Artistic areas. The latter two areas report both the fewest numbers employed and the smallest percentages of employment across the six RIASEC areas.

The current emphasis on preparation for careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields involves occupations that do not employ large numbers of people. These occupations, often found in the Investigative and Artistic areas, employed relatively small numbers of people in 2010 compared to the other four areas: 12% versus 88%. The STEM fields are not big-growth occupational areas that employ many hundreds of thousands or millions of people (e.g., nurses, retail salespersons, office clerks, teachers). However, the STEM fields are generally characterized by fast growth that involves a few thousand or more persons (e.g., biomedical engineers, veterinary technicians, glaziers, physical therapists). Persons in these occupations typically have higher salaries and better employment opportunities (Horrigan, 2003–2004).

The findings of the present study indicate that most people are employed in Realistic, Enterprising and Conventional (REC) occupations. Public attention to employment and career preparation often is directed at occupations with code combinations in the Investigative, Artistic and Social (IAS) areas because the percentage rate of employment growth is often greater there than in the REC areas (Reardon et al., 2012). The IAS areas provide higher levels of prestige and income, but employ fewer people (Reardon et al., 2004). One must remember that these are projected new jobs, which seem to capture more public attention and interest than the census data regarding actual employment.

A large number of jobs actually involve replacement of older workers, perhaps as much as one-third of employment (Mittelhauser, 1998). The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS; 2012) used data from the Current Population Survey and found that the replacements provide many more job openings in most occupations than straight employment growth does.

While the census data provide information about past employment that can inform career planning, the U.S. BLS provides additional labor market forecast information based on occupational projections. Lockard and Wolf (2012) identified the 20 occupations expected to have the most job openings each year through 2020 (big-growth occupations). Four of these occupations—registered nurses, retail salespeople, home health aides and personal care aides—will add more than half a million jobs each through 2020. These occupations are not new, different or unique, and they are unrelated to STEM fields. Reardon et al. (2012) noted that the Holland summary code order for these 20 big-growth occupations was SREICA. In the current study, the profile for employment in the 2010 census was RECSIA. It is not surprising that the Realistic area is prominent in both of these projections, because according to the census, it is the area of largest employment in the economy.

Given the overall increase in actual employment from 64.1 million in 1960 to 119.8 million in 2010, there has been a corresponding increase in employment across the six areas of work. For example, the number of persons employed in the Investigative area has grown from over 1.9 million in 1960 to 11.5 million in 2010, and in the Social area from 5.6 million in 1960 to 29.6 million in 2010. Employment growth has been less dramatic in the Artistic, Enterprising and Conventional areas, and growth has declined slightly in the Realistic area from 35.0 million in 1960 to 31.9 million in 2010.

In addition, the percentages of the U.S. population employed in the six areas of work also have changed from 1960–2010, but in a less dramatic way (see Figure 2). For example, the employment percent profile from highest to lowest employment in 1960 was RECSIA, and in 2010 it was RSECIA, with only the ECS areas alternating in order. However, the percentage difference between the Realistic and Artistic areas was greater in 1960 (54%) than in 2010 (25%). This may be evidence of a decline in manufacturing.

Income Across Six Areas of Work

Our findings indicate that income is not equitable across the six RIASEC areas, with the Investigative area consistently having the highest income and the Realistic and Conventional areas the lowest. Research using census data by Huang and Pearce (2013), Reardon et al. (2004), and Reardon et al. (2007) revealed similar findings. We find that although the RIASEC schema is familiar to counselors using the Self-Directed Search, the Strong Interest Inventory and many other career assessments, the idea of using this schema to analyze occupational information is more novel. For example, thinking of income levels in terms of the RIASEC schema means using an order of IEASRC per the 2010 census data when discussing occupational information with clients.

Reardon et al. (2007) reported that examining levels of cognitive complexity associated with occupations may provide an explanation for the income disparity among the six RIASEC areas. G. D. Gottfredson and Holland (1996) created the Complexity Rating (Cx) to estimate the cognitive skill and ability associated with an occupation. In developing the Cx, the authors wanted to make greater use of job analysis ratings obtained by the U.S. BLS and also create a single measure of cognitive or substantive complexity associated with an occupation. They noted that cognitive complexity of work demands (G. D. Gottfredson & Holland, 1996) might be an appropriate term for the Cx. A Cx rating of 65 or higher could be associated with an occupation requiring a college degree and possibly postgraduate work and on-the-job training of 4–10 years, while a Cx level of 50 might characterize an occupation requiring a high school diploma and a year or more of on-the-job training. Reardon et al. (2007) found that Cx levels were highest in the Investigative and Artistic areas and that the Conventional area was associated with the lowest ratings. They found that employment in the Investigative area occurred only at the highest two levels of Cx (i.e., baccalaureate or higher) while the other four areas—Realistic, Social, Enterprising and Conventional—showed employment at all six levels of Cx.

Huang and Pearce (2013) reported that higher annual incomes in 2010 were found in occupations associated with greater Investigative and Enterprising traits. In addition, they found that the differentiation of an occupational interest profile positively predicted median annual income and moderated the effect across each of the six RIASEC areas. In other words, the more the occupation was characterized by a single, robust RIASEC code letter, the greater the income level for the occupation.

Reardon et al. (2007) examined income by kinds of work and found that the average income profile for six kinds of work ranging from highest to lowest was IESARC. In the current study, the income profile was almost identical—IEASRC. These findings are very similar to those reported by Huang and Pearce (2013). Given that the Investigative area of work requires more education and training than the other five areas, these findings from census data provide evidence that education pays. Reardon et al. (2012) reported that the unemployment rate is clearly related to educational attainment. Those with more education are less frequently unemployed and have higher weekly earnings—more education is connected to more income.

Limitations

As with earlier studies (Reardon et al., 2007; Reardon et al., 2004), several limitations in the present study should be noted. First, the occupational titles included in the census have changed only slightly over the years. The U.S. BLS conducts extensive research to determine whether a new occupation should be added to its list of detailed occupations. A new occupation is one that includes duties not previously identified, one that has been recognized in small numbers and continues to grow (e.g., now has its own professional association or trade group), or one that is evolving and whose tasks have changed significantly. These new occupations arise from technological advances, new laws or regulations, or changing demographics. However, we believe that this issue has minimal impact on the findings of the present study because changes in occupational codes are unlikely to affect the first letter of a code. First-letter codes of occupations are much more stable over time and across industries than second or third letters.

A second limitation of this study is related to the classification of hundreds of thousands of jobs into 350–500 occupational categories, which requires considerable judgment and skill by occupational analysts. These specialists base their judgments on the application of classification criteria, and there is the possibility of error in the use of this system of analysis. Third, we used the first letter in each Holland code in our analysis in order to simplify reporting. While this decision reduced some of the precision inherent in the Holland classification when three-letter codes are used, it increased the accuracy of occupational classification.

Fourth, our analysis was based on a sampling procedure used by the U.S. Census Bureau over 6 decades, and we generalized from this sample to the entire U.S. population. We assumed that the sampling procedure used by the U.S. Census Bureau was appropriate for this study. Fifth, the method for calculating the income levels reported in this study differed across the 3 decades, and comparisons should be made with caution. We used mean levels rather than median levels, and information about the skew of the distribution is not provided in this study. For example, Lowe (2010) noted that while the American Community Survey data are more current, they are not as precise (margins of error are generally higher) as data obtained in the long form used by the U.S. Census Bureau previously. Finally, it is possible that occupations may be shifting within or among industry groups, which would mask some of the findings regarding income reported in the present analysis.

Implications for Counseling Practice

Limitations notwithstanding, the results of this analysis of six kinds of work and employment over 6 decades have implications for counselors. Holland (1997) noted several rules to use in interpreting the Self-Directed Search interest inventory, such as the Rule of Asymmetrical Distribution of Types and Subtypes. This rule reminds both counselor and client that the distribution of types across the six RIASEC areas is very uneven and unequal; moreover, the distribution of jobs across the six types is not symmetrical or equal. Codes associated with small employment numbers may have fewer positions and fewer openings. The research in the present article underscores the validity of this rule. In each census period, the Artistic area was the smallest area of employment at 1% or 2%. At the other extreme, the Realistic area was the largest area of employment, ranging from 55% in 1960 to 27% in 2010. Career counselors should be cautious in advising workers to look for employment outside the Realistic area, because it has been the largest area of employment for the past 6 decades, with ongoing replacement needs (Reardon et al., 2007).

We can add that even the numbers of named census occupations are extremely uneven across six kinds of work. For example, the schema based on RIASEC types used in 2010 to examine occupations was heavily skewed in the direction of the Realistic area (N = 211), with very few occupational titles associated with the Artistic area (N = 19). We surmise that these findings reveal little evidence of instability and change in the use of the occupational schema by the U.S. Census Bureau, at least from a RIASEC perspective.

Some of these findings may be interpreted in different ways. For example, the Realistic area employed the most persons in 2010, but employment in that area has dropped 28% over the 6 decades. The loss of jobs in the Realistic area is greater than the changes in any other area, decreasing from 42.7 million in 1990 to 31.8 million in 2010. The Investigative area almost tripled in employment from 1960–2010, from 3% to 10%, but fewer than 10% of total U.S. jobs are in the Investigative area (11.5 million). These findings seem related to the issue of big-growth and fast-growth jobs described by Horrigan (2003–2004), in which very few occupations appear at the top of both lists. For example, only home health aides and personal care aides are included in both the top 20 big-growth and fast-growth employment areas. This information underscores the importance of understanding demography and an aging population in using labor market information. The information used in career guidance programs often touts the rapid growth in information and technology jobs; however, this information must be balanced with the understanding that only 8% of U.S. employment is in the Investigative area.

The findings of the current study can update and enhance a counselor’s view of labor market information based on Holland’s career theory. We suggest that a RIASEC perspective on jobs in the labor market indicates that things are not really changing as much as others sometimes discuss. U.S. census data compiled over 6 decades (1960–2010) can inform counseling practice and career interventions for students and others exploring occupational changes. These findings can assist counselors and their clients in better matching personal characteristics with occupational and work environments.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

Foutch, H., McHugh, E. R., Bertoch, S. C., & Reardon, R. C. (2014). Creating and using a database on Holland’s theory and practical tools. Journal of Career Assessment, 22, 188–202. doi:10.1177/1069072713492947

Gottfredson, G. D. (1984, August). An empirical classification of occupations based on job analysis data: Development and applications. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada.

Gottfredson, G. D., & Daiger, D. C. (1977). Using a classification of occupations to describe age, sex, and time differences in employment patterns. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 10, 121–138.

Gottfredson, G. D., & Holland, J. L. (1989). Dictionary of Holland occupational codes (2nd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Gottfredson, G. D., & Holland, J. L. (1996). Dictionary of Holland occupational codes (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Gottfredson, G. D., Holland, J. L., & Gottfredson, L. S. (1975). The relation of vocational aspirations and assessments to employment reality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 7, 135–148. doi:10.1016/0001-8791(75)90040-8

Gottfredson, L. S. (1978). An analytical description of employment according to race, sex, prestige, and Holland type of work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 13, 210–221. doi:10.1016/0001-8791(78)90046-5

Gottfredson, L. S. (1980). Construct validity of Holland’s occupational typology in terms of prestige, census, Department of Labor, and other classification systems. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 697–714. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.65.6.697

Gottfredson, L. S., & Brown, V. C. (1978). Holland codes for the 1960 and 1970 census detailed occupational titles. Journal Supplement Abstract Service Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 8, 22. (MS. No. 1660)

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J. L., & PAR Staff. (2010). The self-directed search occupations finder—revised edition. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Horrigan, M. W. (2003–2004). Introduction to the projections. Occupational Outlook Quarterly, 47, 1–4.

Huang, J. L., & Pearce, M. (2013). The other side of the coin: Vocational interests, interest differentiation and annual income at the occupation level of analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83, 315–326. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2013.06.003

Johnson, W. (1946). People in quandaries: The semantics of personal adjustment. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Lockard, C. B., & Wolf, M. (2012). Occupational employment projections to 2020. Monthly Labor Review, 84, 84–108.

Lowe, S. (2010). How the American community survey will improve census statistics. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/pdf/09ACS_improve.pdf .

Mittelhauser, M. (1998). The outlook for college graduates, 1996–2006: Prepare yourself. Occupational Outlook Quarterly, 42, 2–9.

Murray, C. (2012). Coming apart: The state of white America, 1960–2010. New York, NY: Crown Forum.

Reardon, R. C., Bullock, E. E., & Meyer, K. E. (2007). A Holland perspective on the U.S. workforce from 1960 to 2000. Career Development Quarterly, 55, 262–274. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2007.tb00082.x

Reardon, R. C., & Lenz, J. G. (1998). The self-directed search and related Holland career materials: A practitioner’s guide. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Reardon, R. C., Lenz, J. G., Sampson, J. P., Jr., & Peterson, G. W. (2012). Career development and planning: A comprehensive approach (4th ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt.

Reardon, R. C., Vernick, S. H., & Reed, C. A. (2004). A Holland perspective on the U.S. workforce from 1960 to 1990. Journal of Career Assessment, 12, 99–112.

Rounds, J. (1995). Vocational interests: Evaluating structural hypotheses. In D. J. Lubinski & R. V. Dawis (Eds.), Assessing individual differences in human behavior: New concepts, methods, and findings (pp. 177–232). Palo Alto, CA: Davies-Black.

Sampson, J. P., Jr., & Reardon, R. C. (2011). Changes in occupations? A commentary and implications for practice. The Professional Counselor, 1, 41–45.

Savickas, M. L. (2012). Life design: A paradigm for career intervention in the 21st century. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90, 13–19. doi:10.1111/j.1556-6676.2012.00002.x

Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J.-P., Duarte, M. E., Guicharad, J., . . . van Vianen, A. E. M. (2009). Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75, 239–250. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2009.04.004

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2012, February). Estimating occupational replacement needs. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_replacements.htm

U.S. Census Bureau. (1992a). 1990 census of population alphabetical index of industries and occupations. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Census Bureau. (1992b). Census of population and housing, 1990: Summary Tape File 3 on CD-ROM. [Machine-readable data file]. Washington, DC: Author.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2002). Census 2000 basics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Department of Commerce. (1980). Standard occupational classification manual. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Department of Labor. (2010). Standard occupational classification (SOC) system manual. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Weinrach, S. G. (1980). Have hexagon will travel: An interview with John Holland. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 58, 406–414. doi:10.1002/j.2164-4918.1980.tb00420.x

Mary-Catherine McClain is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Georgia. Robert C. Reardon is a professor emeritus at Florida State University. Correspondence can be addressed to Robert C. Reardon, FSU Career Center, PO Box 3064162, 100 South Woodward Avenue, Tallahassee, FL 32306-4162, rreardon@admin.fsu.edu.

Feb 9, 2015 | Article, Volume 5 - Issue 1

Joel A. Lane

Today’s emerging adults (i.e., individuals between the ages of 18 and 29) in industrialized nations navigate multiple significant life transitions (e.g., entering career life), and do so in a rapidly changing society. While these transitions pose psychological difficulties, a growing body of research has identified attachment and social support as two notably salient protective factors in emerging adulthood. The purpose of the present article is to explore the counseling of emerging adult clients, particularly those in the midst of one or more transitions. The concept of emerging adulthood represents a relatively recent phenomenon that the counseling community has been slow to acknowledge. Specifically, this author reviews literature pertaining to emerging adulthood, attachment and social support, and uses this literature to provide clinicians with practical recommendations for counseling emerging adults.

Keywords: emerging adulthood, life transitions, attachment, social support, counseling

Emerging adulthood is a stage of life resulting from recent societal trends in industrialized nations, occurring between the ages of 18 and 29 (Arnett, 2000, 2004, 2007). These trends include the proliferation of college enrollment, significant delays in settling down and high unemployment compared to prior generations of young adults (Furstenberg, Rumbaut, & Settersten, 2005). Corresponding with these changes is an evolution of the psychosocial development of current emerging adults, who engage in extended identity exploration and report subjectively feeling in between adolescence and adulthood (Arnett, 2001). While the benefits and drawbacks of these changes are a source of frequent and intense debate (Arnett, 2013; Twenge, 2013), few would disagree that being twenty-something today is a drastically different experience than it was several decades ago.

Emerging adulthood presents many life transitions and significant mental health risk. In the midst of prolonged identity experimentation and subjectivity, emerging adults navigate a multitude of major life and role changes, such as leaving home, entering and leaving educational settings, and starting a career. The convergence of these factors—the subjective feeling of not being an adult and near-constant life changes propelling one toward adulthood—seems to contribute to critical periods of identity crisis and various psychological difficulties (Lane, 2013b; Lee & Gramotnev, 2007; Weiss, Freund, & Wiese, 2012). Though not all emerging adults experience difficulties during these transitions (Buhl, 2007; Galambos, Barker, & Krahn, 2006), some respond with significant distress (Murphy, Blustein, Bohlig, & Platt, 2010; Perrone & Vickers, 2003; Polach, 2004), which is problematic given that the emerging adult years are considered a critical juncture in the development of mental illness (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; Ingram & Gallagher, 2010) and substance abuse (APA, 2013; Chassin, Pitts, & Prost, 2002; Ingram & Gallagher, 2010). Elevated distress also has been shown to increase impulsivity and risk-taking behaviors in emerging adulthood (Scott-Parker, Watson, King, & Hyde, 2011). The distress accompanying these transitions, therefore, poses a considerable threat to emerging adult well-being.

Despite these changes and risk factors, the counseling community has been slow to acknowledge the evolving landscapes of the late teens and twenties. Counselor training programs continue to prominently feature theories of development contending that identity development is a task completed by the end of the teenage years (i.e., Erikson, 1959/1994). It seems likely that many counselors face the challenge of using outdated developmental models to conceptualize their emerging adult clients. For counselors to work effectively with the many challenges and risks that emerging adults face, they must have an increased awareness of emerging adulthood and better understand factors that predict well-being and stability during the numerous transitions commonly experienced. To address this concern, the author provides an overview of emerging adult theory and research describing the significance of emerging adult life transitions; reviews literature examining the importance of attachment and social relationships in emerging adulthood, which appear to especially salient sources of risk resilience during this period of life; and considers implications for counseling professionals to utilize when working with emerging adults.

Emerging Adulthood

Current societal expectations regarding normative life trajectories in the early-to-mid 20s—being finished with education, marrying, acclimating to a professional setting and adjusting to life as a parent—do not seem fully applicable to today’s emerging adults in most industrialized nations. Arnett (2000) described emerging adulthood as a period of feeling “in between” (p. 471), during which individuals are no longer adolescents, but do not yet identify as adults. Thus, the normative developmental tasks for individuals in their 20s seem to have shifted from objective tasks like attaining work, settling down and becoming financially independent, to more subjective tasks like considering the question, Who am I and what do I want my life to look like? This shift is reflected in several factors that distinguish emerging adulthood from other life stages and from prior young adult generations. Of these distinctions, the three most prominent pertain to demographic instability, changes in subjective self-perceptions and extended periods of identity testing (Arnett, 2000).

Characteristics of Emerging Adulthood

One way that emerging adulthood is distinct from other life stages is with regard to demographics. The past several decades correspond with higher proportions of 18- to 25-year-olds leaving home and periodically moving back home several times (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999), attending college immediately after high school (Arnett, 2004), delaying marriage and childbirth (Arnett, 2000), spending more time in college (Arnett, 2004; Mortimer, Zimmer-Gembeck, Holmes, & Shanahan, 2002) and changing careers (Wendlandt & Rochlen, 2008). In comparison to other age groups, the demographic statuses of emerging adults today vary with little predictability (Arnett, 2000; Cohen, Kasen, Chen, Hartmark, & Gordon, 2003); however, the demographic factor that is most predictable is frequent residential change (Arnett, 2000, 2007; Shulman & Nurmi, 2010). All of these trends indicate the changing demographic landscapes of today’s late teens and early 20s compared to those of prior generations.

Another changing landscape of emerging adulthood is a trend toward increasingly vague and subjective self-perceptions (Arnett, 2000; Fussell & Furstenberg, 2005). Emerging adults view their progression into adulthood as long and gradual. When a sample of emerging adults were asked if they felt they had reached adulthood, over 50% selected the answer choice “in some respects yes, in some respects no,” and fewer than 5% selected “yes” (Arnett, 2001, p. 140). Moreover, emerging adults seem to consider individual character qualities (e.g., accepting responsibility) to be more salient indicators of having reached adulthood than objective milestones, such as completing education or becoming a parent (Lopez, Chervinko, Strom, Kinney, & Bradley, 2005). In short, emerging adults perceive themselves as no longer adolescents, but also not quite adults, and report vague perceptions of what it will take to feel more like adults.

A third distinction of emerging adulthood is a prolonged period of identity exploration (Arnett, 2000; Gerstacker, 2010). Given the relative freedom from life obligations, in tandem with the long-term implications of many of the decisions that will be made during emerging adulthood, this stage of life represents an opportunity for significant identity development to occur (Gerstacker, 2010). The freedom to engage in identity exploration results in the delay of firm decisions regarding adult roles (Schulenberg, Bryant, & O’Malley, 2004). These factors also contribute to an increased self-focus during emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2004). While some researchers have interpreted these features as resulting from increased narcissism among emerging adults (e.g., Twenge, 2013), Arnett (2004) conceptualized them as temporary and developmentally normative qualities.

The three most common areas of emerging adult identity exploration are love, work and worldviews (Arnett, 2000). First, emerging adults use their freedom to explore varying levels of commitment with regard to sexual and romantic relationships (Arnett, 2004), and do so in a time period with unprecedented societal acceptance of differing sexual and romantic preferences (Garcia, Reiber, Massey, & Merriwether, 2012). Second, significant identity exploration occurs with regard to professional identity, for which evidence can be found in several college trends. Emerging adults are increasingly likely to change their majors more than once (Arnett, 2000), report negative attitudes toward graduation (Lane, 2013a, in press-a; Yazedjian, Kielaszek, & Toews, 2010), spend more time in college (Arnett, 2004) and experience more career turnover (Wendlandt & Rochlen, 2008) than prior generations. Finally, worldviews represent a third area of identity exploration. With today’s unprecedented higher education enrollment (National Center for Education Statistics, 2014; Weber, 2012), a growing number of emerging adults are gaining a more complex understanding of the world around them via higher education experiences. The impact of the college environment on moral reasoning and cross-cultural experiences is well documented (e.g., Bowman, 2010). These trends may explain the observations of several scholars that today’s emerging adults share an unprecedented passion for social justice and community well-being (e.g., Arnett, 2007), especially in urban areas.

Emerging Adult Transitions

A central feature of emerging adulthood is the frequent occurrence of significant life transitions. Each of these transitions initiates significant role changes that impact social networks, familial support and autonomy. The influence of life transition on well-being has been well documented and frequently results in periods of self-doubt, immobilization and denial (Brammer & Abrego, 1981). In contrast to common assumptions that the transitions associated with emerging adulthood (e.g., college graduation, obtaining employment) are positive life events, these transitions represent periods of loss (Vickio, 1990) that consist of considerable psychological distress for some individuals (Lane, in press-a, in press-b; Lee & Gramotnev, 2007). The proceeding section reviews a growing body of recent research suggesting that the characteristic delay in adult identity formation in emerging adulthood may increase the degree of loss and difficulty experienced during several normative transitions.

High school graduation. Conclusions are mixed regarding the assertion that high school graduation is a critical emerging adult transition. Though some have reported that graduation is associated with increased quality of parental relationships and decreased depressed mood and delinquent behaviors (Aseltine & Gore, 1993), others have reported significant differences in these trajectories as a function of race and college attendance (Gore & Aseltine, 2003). Similarly, social and institutional support predicts whether deviant behaviors increase or decrease after high school (Sampson & Laub, 1990). These findings suggest that the transition of high school graduation is a positive experience for some emerging adults, but a psychologically distressing experience for others, especially those who lack social support, do not attend college, or identify as African American or Latino.

The transition to professional life among non-college attendees. After high school, the two most common trajectories are to enter either postsecondary education or the workforce (Arnett, 2004). The transition to work can be particularly difficult for those who forgo college. These emerging adults attempt to transition into professional life without the advantage of higher education—a psychologically beneficial resource that provides important institutional and social support (Raymore, Barber, & Eccles, 2001). Among individuals with high school diplomas, unemployment rates are highest between the ages of 18 and 19, approaching 20% in 2014 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). Those who do find work are unlikely to receive a sustainable income, as mean incomes among emerging adults are drastically lower than for other adult age groups (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Such difficulties are particularly problematic given that unemployment and economically inadequate employment have been implicated as mental health risks (Dooley, Prause, & Ham-Rowbottom, 2000).

The freshman transition. For those emerging adults who decide to attend college, their adjustment to college life also represents a significant life transition. In particular, the first year of college is a risk factor for psychological distress. Bowman (2010) found that among first-generation college freshmen, psychological well-being significantly decreased throughout the course of the freshman academic year. Similarly, Sharma (2012) demonstrated that first-year undergraduates experienced significantly greater emotional and social difficulties than other college students. A prominent focus of first-year transition literature is the important role of attachment relationships, a construct that will be discussed in greater depth later in this article. In short, the attachment security of incoming freshmen predicts their overall well-being, as well as their social and academic adjustment (Kenny & Donaldson, 1991; Larose & Boivin, 1998).

The senior year experience. A small but growing body of recent research has identified potential difficulties for college seniors preparing to transition out of school (Lane, 2013a, in press-a). The college experience represents a period of moratorium from many adult responsibilities (Fasick, 1988) and is associated with increased leisure behaviors compared to individuals who do not attend college (Raymore, Barber, Eccles, & Godbey, 1999). Given the subjective experience among emerging adults that they have not yet reached adulthood (Arnett, 2001) and the prevailing societal expectation that college graduation is associated with adult roles (e.g., entering the workforce, settling down), it is likely that emerging adults increasingly view graduation as an important signifier of impending life changes for which they do not feel ready (Lane, 2013a). For example, ambivalence about graduating was one of the primary themes to emerge from a qualitative study of college seniors (Yazedjian et al., 2010). Other qualitative studies of college seniors have found that students are frequently anxious about graduating due to the impending changes they will experience in priorities (Overton-Healy, 2010) and the sense that they lack direction regarding the next phase of life (Allen & Taylor, 2006). Factor analyses of surveys given to college seniors uncovered domains of concern about graduation, including leaving behind the student lifestyle, the impending loss of friendships and support, the process of obtaining employment, and the process of applying to graduate school (Pistilli, Taub, & Bennett, 2003). A recent path analysis revealed significant relationships between these domains of concern and factors such as life satisfaction, psychological health and attachment security (Lane, in press-a).

Life after college. Given the psychological implications of preparing to leave the college environment, it is not surprising that the time immediately following college life often presents psychological difficulties as well. A sample of Australian college graduates voiced concerns about adjusting to life after college and to work life, referring to this period as a low point of their lives (Perrone & Vickers, 2003). Chickering and Schlossberg (1998) found that well-being suffered when emerging adult graduates encountered difficulties obtaining employment. Such findings are especially significant since they contrast overall trends toward increased well-being throughout emerging adulthood (Galambos et al., 2006). That is, while emerging adulthood is associated with upward trends in well-being, the time immediately following graduation can alter this trajectory, especially when emerging adults experience difficulties obtaining employment.

However, emerging adults who do secure postcollege employment are not exempt from transition-related distress. This transition involves significant changes in attitudes, expectations and levels of preparedness compared to college life (Polach, 2004; Wendlandt & Rochlen, 2008). Transitioning to the world of work can be particularly difficult since emerging adults are typically leaving an environment in which they felt experienced (e.g., high school, college) and becoming inexperienced professionals (Lane, in press-b). More than half of all college graduates leave their initial place of postcollege employment within two years of graduating (Wendlandt & Rochlen, 2008), and there is evidence suggesting that this turnover is due to difficulties in adjusting to professional life for the first time (Sturges & Guest, 2001). Such difficulties seem to frequently result in experiences of imposter syndrome (i.e., perceiving oneself as incompetent despite evidence of competence) among emerging adults entering professional life (Lane, in press-b). Other related difficulties include significant learning curves, less feedback and structure than afforded by the college environment, guilt about initial levels of work production, and difficulties forming new social networks (Polach, 2004). Similarly, the results of a survey conducted by Sleap and Reed (2006) suggested that most graduates possess limited awareness of the impending culture changes they will experience as a result of leaving higher education and entering the workplace. The importance of this awareness was demonstrated in a longitudinal study in which emerging adults were tested as college seniors regarding their knowledge about workplace culture, and then were subsequently tested both six months and one year after entering professional life (Gardner & Lambert, 1993). Those who had more accurate information as seniors were more likely to report job satisfaction at both subsequent intervals. Buhl (2007) conducted a similar longitudinal study, finding that the subjective quality of participant parental relationships predicted well-being trajectories during the initial three years of professional life.

In sum, it is clear that the common transitions experienced during emerging adulthood pose threats to well-being due to role confusion and psychological distress. Given the risks associated with psychological distress, it is paramount to better understand factors that might promote the maintenance of well-being during periods of transition in emerging adulthood. Accordingly, a focus of emerging adult research has been examining constructs that predict positive developmental progressions through these periods of transition. Two such constructs that have received considerable attention are attachment (e.g., Kenny & Sirin, 2006) and social support (e.g., Murphy et al., 2010). It seems that emerging adults who feel secure in their relational attachments and supported by social networks are able to face the developmental challenges of emerging adulthood with greater confidence and well-being than those who lack support and secure attachments. To better explain the impact of these constructs on emerging adult development and well-being, the proceeding sections of this article examine attachment and social support literature pertaining to emerging adulthood.

Attachment

Attachment theory contends that the early relationships people develop with their caregivers inform attitudes toward help seeking and new learning in times of distress across the lifespan (Bowlby, 1969/1982). Attachment is defined as the emotional bonds that develop between children and their caregivers beginning in infancy. Based on repeated experiences of caregiver responsiveness, infants begin to develop beliefs and expectations regarding the degree to which their physical and emotional needs will be satisfied. According to attachment theory, these beliefs become internalized as subconscious representations of self and other, which continue to increase in complexity and broadly inform social interactions throughout the lifespan. Those whose representations are based on consistent and sufficient caregiver responsiveness are considered securely attached and are likely to trust their ability to resolve future needs, either by themselves or by relying on caregivers. Insecurely attached children, on the other hand, develop expectations that their caregivers cannot be adequately relied upon in times of need; these children are likely to react to perceived threats with inappropriate levels of affect (i.e., overactivation or deactivation). These reactions interfere with the children’s development of effective emotional regulation and with the successful resolution of stressful situations, thereby continuing to reinforce such responses to future stressful situations (Guttmann-Steinmetz & Crowell, 2006).

This idea positions early attachment relationships as a likely influence on psychological health in emerging adulthood. The years of later adolescence and early emerging adulthood are a time in which attachment needs are increasingly fulfilled by peers and romantic partners, as opposed to caregivers (Fraley & Davis, 1997). Thus, the relative security of parental attachment representations is likely to inform interpersonal trust and intimacy, as well as the ability to seek the meeting of attachment needs from others (Schnyders & Lane, 2014). In fact, frequency of contact with parents during emerging adulthood is negatively associated with subjective closeness to parents (Hiester, Nordstrom, & Swenson, 2009), while geographical distance from parents is positively associated with psychological adjustment (Dubas & Petersen, 1996). Younger emerging adults are likely to begin experimenting with independence, though they often still use parents or caregivers as attachment figures in times of distress (Fraley & Davis, 1997; Kenny, 1987).

Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) conducted what was perhaps the first study to consider the relevance of attachment to the unique needs of young adult populations. They demonstrated several trajectories in interpersonal functioning on the basis of attachment functioning. In the study, attachment was conceptualized as occurring across dimensions of self and other: secure (positive representations of self and other), anxious (negative representations of self, positive representations of other), dismissive-avoidant (positive representations of self, negative representations of other), and fearful-avoidant (negative representations of self and other). Such a conceptualization has become a standard for contemporary adult attachment research (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). Fearful-avoidant participants seemed to struggle with interpersonal passivity. Dismissive-avoidance was “related to a lack of warmth in social interactions” (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991, p. 234). The interpersonal problems of anxious participants suggested control seeking or overinvolvement in the affairs of their peers. These findings corroborate more recent conceptualizations of insecure attachments in adulthood (Brennan et al., 1998; Mallinckrodt, 2000). Specifically, individuals with elevated attachment anxiety are likely to respond to distress with a hyperactivated strategy, heightening awareness of their distress and causing them to seek inappropriate levels of interpersonal dependence. Conversely, individuals with elevated attachment avoidance are likely to respond to distress with a deactivated strategy, inhibiting awareness of negative affect and preventing them from seeking support from others.

A growing body of emerging adult research supports the importance of healthy attachment functioning for various psychological outcomes during emerging adulthood. Attachment is a crucial predictor of well-being trajectories at many key emerging adult transition points (Lane, 2014), including the first year of college (Kenny & Donaldson, 1991), the last year of college (Lane, in press-a) and the postcollege years (Kenny & Sirin, 2006). For example, one study tracked Israeli males from their final year of high school through their third year away from home for compulsory military service (Scharf, Mayseless, & Kivenson-Baron, 2004). Securely attached individuals demonstrated better coping strategies and higher capacity for intimacy during their military service than those with insecure attachments. More generally, attachment security in emerging adulthood also influences self-reinforcement capacity and reassurance needs (Wei, Mallinckrodt, Larson, & Zakalik, 2005), affect regulation and resilience (Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012), perceived self-worth (Kenny & Sirin, 2006), dysfunctional attitudes and self-esteem (Roberts, Gotlib, & Kassel, 1996), self-compassion and empathy toward others (Wei, Liao, Ku, & Shaffer, 2011), self-organization strategies (Lopez, Mitchell, & Gormley, 2002), and identification with emerging adulthood (Schnyders, 2014; Schnyders & Lane, 2014). Many of these factors illustrate the importance of attachment functioning in developing healthy and supportive interpersonal social networks.

Social Support

The construct of social support refers to social relationships or interactions that provide individuals with actual or perceived assistance (Sarason et al., 1991). Social support is psychologically beneficial in its capacity to mitigate stress during stressful situations (e.g., Ditzen et al., 2008), an idea commonly referred to as the stress buffering hypothesis (Cohen & McKay, 1984). A wealth of recent research has strongly suggested that social support is particularly salient during emerging adulthood, as this is a life period marked with numerous transitions and opportunities to experience distress. In a qualitative study of emerging adults who had recently transitioned into professional life, social support was the most prominent theme related to adjustment (Murphy et al., 2010); those who reported relational isolation also struggled with unpreparedness for new financial obligations and feeling that their expectations about life after college were left unfulfilled. Mortimer et al. (2002) reported similar findings. Wendlandt and Rochlen (2008), noting that social support is often lacking in the transition out of college and into the work force, urged college counselors to develop interventions aimed at increasing perceived support. This idea was supported in a study of college graduates who had recently relocated to a metropolitan area and were adjusting to their first year of professional life (Polach, 2004). Participants reported frustration and difficulties trying to establish new peer groups outside the college environment. They also cited the importance of a sense of belonging as the primary reason for moving to a city after graduating. Clearly, ample evidence supports the protective qualities of social support for emerging adults transitioning into professional life.

Moreover, social support also seems to be important during other emerging adult transitions. In one qualitative study, emerging adult participants described the ability to understand friendship dynamics as an important component in the subjective experience of reaching adulthood (Lopez et al., 2005). Examples of understanding friendship dynamics included the maintenance of preexisting friendships, changes in friendships based on varying maturation rates, and understanding the importance of the social network. In another study, first-year college students seemed to adjust more effectively to college life when the support they received from family members shifted from actions consistent with parental attachment to actions consistent with social support (Kenny, 1987). In a multiethnic sample of urban high school students, perceived social support predicted aspirations for career success, positive beliefs pertaining to achieving career goals and the importance of work in the future (Kenny, Blustein, Chaves, Grossman, & Gallagher, 2003).

Several longitudinal studies also have demonstrated relationships between aspects of social support and various elements of positive adjustment in emerging adulthood. A large study that tracked individuals for nearly 30 years beginning at age 7 (Masten et al., 2004) found that social quality was an aspect of resilience and predicted success in various emerging adult developmental tasks (e.g., academic attainment). Moreover, success with these tasks predicted success in postemerging adult developmental tasks (e.g., parenting quality, romantic success, work success). O’Connor et al. (2011) found perceived quality of peer relationships to predict positive development in emerging adulthood, which they conceptualized to include life satisfaction, trust and civic engagement. Galambos et al. (2006), in a longitudinal study tracking nearly 1,000 Canadian participants throughout the course of emerging adulthood, found that increases in social support were significantly correlated with increases in well-being.

These findings suggest that the degree to which emerging adults are able to develop and rely upon support networks directly impacts their ability to adapt to various normative experiences and transitions. Given the aforementioned discussion regarding emerging adult attachment, it is likely that these two constructs (attachment and social support) are of shared importance during such transitions. That is, attachment representations inform one’s capacity for positive interpersonal interactions (Mallinckrodt & Wei, 2005), and in this way, attachment and social support collectively facilitate transition processes in emerging adulthood (Lane, 2014; Larose & Boivin, 1998).

Implications for Counseling Emerging Adults