Apr 29, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 2

Daniel Gutierrez, Allison Crowe, Patrick R. Mullen, Laura Pignato, Shuhui Fan

Researchers used path analysis to examine self-stigma, help seeking, and alcohol and other drug (AOD) use in a community sample of individuals (N = 406) recruited through the crowdsourcing platform MTurk. Self-stigma of help seeking contributed to AOD use and was mediated by help-seeking attitudes. We discuss the implications for advocacy and stigma reduction in substance use treatment. Counselors and counselor educators can implement and advocate for interventions and training that increase positive attitudes toward seeking help, such as providing appropriate training with supervisees and counselors-in-training, providing clients and the community with mental health literacy, and engaging in more advocacy. Moreover, they can challenge thoughts of seeking help as weakness, normalize seeking psychological help, and discuss the benefits of counseling and therapy to address the development and effects of self-stigma of help seeking for individuals with substance use issues.

Keywords: alcohol and drug use, self-stigma, help seeking, help-seeking attitudes, stigma reduction

In 2015, approximately 20.1 million people over the age of 12 suffered from an alcohol or substance use disorder (SUD) in the United States (Bose et al., 2016). However, only 3.8 million people (1 in 5) who needed treatment received any substance use counseling (Bose et al., 2016). Barriers to receiving substance use treatment include the location of the program, legal fears, peer pressure, family impact, concerns about loss of respect, and stigma (Masson et al., 2013; Stringer & Baker, 2018; Winstanley et al., 2016). Of these concerns, stigma is arguably the most complex and the least understood. In response, substance use prevention and mental health care researchers have begun to turn their attention to stigma and how it influences counseling treatment and recovery (Livingston et al., 2012; Mullen & Crowe, 2017; Stringer & Baker, 2018). Researchers have found that individuals with SUDs experience higher levels of stigma than individuals with any other health concern (Livingston et al., 2012). However, more research on the intersection of stigma, help seeking, and alcohol and other drug (AOD) use is still warranted. Thus, this article delves further into these concepts and describes a study that examined the relationships between these variables.

Stigma and Substance Use

Individuals with substance use concerns report high levels of public stigma in the form of negative labeling, discrimination, and prejudice by others (Crapanzano et al., 2019; Goffman, 1963). Prejudice against people with substance use problems is common and widespread on individual, interpersonal, and institutional levels (Barry et al., 2014). There remains a substantial public belief that those using illicit substances simply need to take responsibility for their choices (Barry et al., 2014). As a result, individuals with SUDs report experiencing judgment, mockery, inappropriate comments, overprotection, and hostility from the public (Mora-Ríos et al., 2017). Even health professionals hold negative perceptions toward patients using substances, believing them to be dangerous, violent, manipulative, irresponsible, aggressive, rude, and lazy (Ford, 2011).

People who perceive this stigma from their health or mental health professionals show a higher treatment attrition rate, less treatment satisfaction, and less perceived access to care (Barry et al., 2014). People with substance use concerns may also experience perceived stigma from the impressions they receive from society and through their own and others’ past experiences (Smith et al., 2016). Perceived stigma is also related to low self-esteem, high levels of depression and anxiety, and sleep issues (Birtel et al., 2017). Individuals who experience public stigma can develop self-stigma (i.e., stigma that is internalized), which impacts help-seeking attitudes (Vogel et al., 2007). For example, an individual could see a person struggling with alcohol use disorder portrayed in the media as being malicious, selfish, and incompetent and begin to believe those stereotypes about themselves.

Additionally, researchers have demonstrated that public stigma is a predictor of self-stigma over time (Vogel et al., 2013). Self-stigma initially develops from stereotype awareness, resulting in stereotype agreement and self-concurrence, which lead to self-esteem decrement (Schomerus et al., 2011). Self-stigma can increase maladaptive coping strategies such as avoidance that can deter seeking treatment, applying for jobs, and interacting with others in social settings (da Silveira et al., 2018). Luoma et al. (2014) also suggested that people with a higher level of self-stigma have lower levels of self-efficacy and tend to remain longer in residential substance abuse treatment.

Role of Stigma and Help Seeking in Relationship to SUDs

The role of public stigma on seeking and receiving psychological help for substance use treatment has been well established by researchers (Birtel et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2016), but the influence of negative perceptions remains less understood (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018). Researchers have asserted the importance of examining negative public attitudes toward seeking psychological help; such attitudes act as a catalyst for the development of self-stigma incurred by individuals struggling with SUDs (Vogel et al., 2013). Also, recent reports indicate that the self-stigma of seeking psychological help may be a major contributor to the treatment utilization gap (i.e., the dearth of individuals receiving substance use treatment despite substance misuse and use disorders becoming a public health crisis). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General (2018) reported that ingrained public attitudes have hindered the delivery of medications used to treat SUDs, such as methadone and buprenorphine, because of misconceptions and prejudices surrounding these medications. Other factors they found contributing to the treatment gap include the view of substance use as a moral failing rather than a disease and the belief that the person simply has a “character flaw” (p. 12). Consequently, policymakers and researchers have emphasized the importance of understanding the effect of negative public attitudes on the delivery of substance use treatment and the decision to seek psychological help for mental health concerns involving AOD (Bose et al., 2018; Corrigan, 2011).

To illustrate, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA; Bose et al., 2018) recently stated that 1.0 million (5.7%) of the 18.2 million individuals aged 12 years or older who reported experiencing an SUD perceived a need for treatment for their illicit drug or alcohol use. However, these respondents reported not seeking specialty substance use treatment because they believed getting treatment would have a negative impact on their job (20.5%) and cause their neighbors or community to have a negative opinion of them (17.2%). Additionally, out of the 4.9 million adults aged 18 or older that reported an unmet mental health service need for a serious mental illness, over a third had not received any mental health services in the previous year. Respondents gave the following reasons for avoiding seeking help: concern about being committed or having to take medicine (20.6%); the risk of it having a negative effect on their jobs (16.4%); the belief that treatment would not help (16.1%); the possibility that their neighbors or community would have negative opinions (15.7%); concern about confidentiality (15.3%); and not wanting others to find out (12.6%).

Given these responses and statistics, it is logical to infer that the commonly held public perception of seeking help for mental health concerns and substance use is still very negative and that many still experience significant fear of discrimination from others (e.g., loss of job or a negative impact on social opportunities) as a result of seeking help for AOD issues. The responses also indicate the harmful influence this public stigma has on individuals’ decisions regarding whether to seek psychological treatment for substance use. Furthermore, these findings suggest that respondents possibly internalized negative public attitudes toward seeking professional help for both mental health and substance use concerns, resulting in self-stigma. The respondents’ decision not to receive needed substance use treatment in the previous year in order to avoid negative reactions from others and their lack of belief in the utility of treatment indicate self-stigma surrounding help seeking. This corresponds to previous literature reporting the effects of self-stigma on help-seeking behaviors and attitudes (Vogel & Wade, 2009).

Purpose of the Present Study

The existing research is clear that stigma has some influence on substance use and recovery. However, there is a lack of research explicating the causal pathways that shape this influence. Another area that is unexplored is the relationship between self-stigma and AOD use, and there is no research that we know of that explores the relationship between help-seeking attitudes and AOD use. Given that self-stigma for mental illness and self-stigma for help seeking are often related in the literature (Mullen & Crowe, 2017), and that a large portion of individuals with SUDs have a co-occurring mental illness (39.1%; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015), it is reasonable to suspect that the stigma of mental illness influences help seeking in AOD users. A greater understanding of the relationships between these constructs will allow counselors and other helping professionals to develop better strategies for combatting substance abuse by addressing issues related to stigma and attitudes toward help seeking. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the relationships between self-stigma of mental health concerns, attitudes toward help seeking, and AOD use. Specifically, we tested the following research hypotheses: Hypothesis 1—Self-stigma toward mental health concerns will have a negative direct effect on attitudes toward help seeking and a positive indirect effect on drug and alcohol use as mediated by attitudes toward help seeking; Hypothesis 2—Self-stigma of help seeking will have a negative direct effect on attitudes toward help seeking and a positive indirect effect on drug and alcohol use as mediated by attitudes toward help seeking; and Hypothesis 3—Attitudes toward help seeking will have a negative direct effect on drug and alcohol use.

Method

Participants

We acquired 406 participants using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Most of the participants were male (n = 213; 52.5%) followed by female (n = 191; 47.0%) and transgender/gender nonconforming (n = 2; 0.5%). The mean age of the participants was 34.39 years (SD = 10.02, range = 20 to 67). In addition, most participants indicated they lived in the United States at the time of the study (n = 349, 86%) with 57 (14%) participants who lived internationally. As for ethnicity, participants included American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 12; 3%), Asian (n = 79; 19.5%), Black or African American (n = 24; 5.9%), Hispanic or Latino (n = 20; 4.9%), Multiracial (n = 5; 1.2%), Other (n = 2; 0.5%), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (n = 1; 0.2%), and White (n = 263; 64.8%). Table 1 displays additional demographic information.

Table 1

Participant Characteristics

| Demographic Characteristics |

n (%) |

| Clinical cutoff for alcohol use |

|

| Met criteria for problematic drinking |

203 (50.0%) |

| Did not meet criteria for problematic drinking |

203 (50.0%) |

| Clinical cutoff for drug use |

|

| Did not meet criteria for problematic drug use |

281 (69.2%) |

| Met criteria for problematic drug use |

125 (30.8%) |

| Individual yearly income |

|

| Less than $30,000 |

173(42.6%) |

| Between $30,000 and $50,000 |

124 (30.8%) |

| More than $50,000 |

108 (26.6%) |

| Education level |

|

| Bachelor’s degree |

169 (41.6%) |

| Some college (no degree) |

82 (20.2%) |

| Master’s degree |

59 (14.5%) |

| Associate degree |

49 (12.1%) |

| High school diploma |

34 (8.4%) |

| Doctoral degree |

8 (2.0%) |

| Some high school (no degree) |

3 (0.7%) |

| Other |

2 (0.5%) |

| Marital status |

|

| Married |

201 (49.5%) |

| Single |

139 (34.2%) |

| Cohabitation |

45 (11.1%) |

| Divorced |

17 (4.2%) |

| Widowed |

2 (0.5%) |

| Separated |

2 (0.5%) |

| Employment status |

|

| Full-time |

290 (71.4%) |

| Part-time |

53 (13.1%) |

| Unemployed (looking for work) |

18 (4.4%) |

| Full-time caregiver |

14 (3.4%) |

| Unemployed (disabled) |

10 (2.5%) |

| Student |

6 (1.5%) |

| Other |

6 (1.5%) |

| Unemployed (not looking for work) |

3 (0.7%) |

| Unemployed (volunteer work) |

1 (0.2%) |

| Note. N = 406 |

|

Procedures

Prior to starting this research investigation, approval from our Institutional Review Board was received. To collect data for a community sample, we employed the use of MTurk, which is an online crowdsourcing platform used for survey research (Follmer et al., 2017). Researchers have found evidence that supports the data quality of MTurk for studies trying to sample diverse community populations that include individuals with substance abuse concerns (Al-Khouja & Corrigan, 2017; Kim & Hodgins, 2017). We placed the consent form, measures, and demographic questions for this study in a Qualtrics survey management site. Then, we created an MTurk portfolio that linked to the Qualtrics survey. The study was advertised to all MTurk participants, and we offered a 50-cent incentive for participation. Participants were screened to allow only individuals who actively engage in the recreational use of drugs and/or alcohol. A total of 406 participants completed the study before it was closed. Participants who took the survey spent an average of 18 minutes completing it.

Measures

Self-Stigma of Mental Illness

Researchers used the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness scale (SSOMI; Tucker et al., 2013) to measure participants’ self-stigma of mental illness. The SSOMI is a self-reported, unidimensional measure consisting of 10 items on a 5-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample items include “If I had a mental illness, I would be less satisfied with myself.” We summed the items and calculated a mean score after accounting for the reverse-scored items, with higher scores indicating greater self-stigma of mental illness. Prior research has shown strong reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of .93 on participants’ SSOMI scores collected through an online survey (Mullen & Crowe, 2017). In our study, we found good internal consistency reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .91 for participants’ scores on the SSOMI.

Self-Stigma of Help Seeking

Researchers used the Self-Stigma of Help Seeking scale (SSOHS; Vogel et al., 2006) to measure participants’ self-stigma of seeking psychological help. The SSOHS is a self-reported, unidimensional measure that contains 10 items on a 5-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample items include “I would feel inadequate if I went to a therapist for psychological help.” After reverse scoring items, we summed and averaged the scores, with higher values indicating greater self-stigma of seeking psychological help. Scores on the SSOHS have indicated good internal reliability, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .89 to .92 in prior research (Tucker et al., 2013; Vogel et al., 2006). In our study, we found good internal consistency reliability for scores on the SSOHS, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .86.

Attitudes Toward Help Seeking

To measure attitudes toward help-seeking, researchers used the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help–Short Form scale (ATSPPH-SF; Fischer & Farina, 1995). The ATSPPH is a self-reported, unidimensional measure that contains 10 items scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 0 (disagree) to 3 (agree). Sample items include “I might want to have psychological counseling in the future.” Participants’ total scores were calculated by summing all items together after reverse scoring items. We averaged the scores on the ATSPPH-SF to help in interpretation, with higher total scores indicating that a participant had a more positive attitude toward psychological treatment. Higher scores on the ATSPPH-SF have been associated with decreased treatment-related stigma and a higher likelihood of future help seeking (Elhai et al., 2008). Prior research has shown good internal consistency reliability for scores on the ATSPPH-SF, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .84 to .86 (Fischer & Farina, 1995; Karaffa & Koch, 2016). In the current study, the scores on the ATSPPH-SF provided good internal consistency reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .84.

Alcohol Use

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993) was used to measure respondents’ alcohol use and screen for problematic drinking behaviors. The AUDIT is a 10-item, self-reported measure that gathers information on an individual’s alcohol use and provides a clinical cutoff score for harmful drinking. Participants rated their alcohol consumption and related experiences over the past year in response to a series of 3- or 5-point Likert-type scale questions. Sample items include “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?” with a 5-point scale from 0 (never) to 4 (four or more times a week). Total scores were calculated by summing the items with scores ranging from 0 to 40. We used a total score of 8 or higher as a clinical cutoff point to identify problematic drinking (see Table 1). Prior research has reported good internal consistency reliability of the AUDIT scores with a Cronbach’s alpha value of .88 (Kim & Hodgins, 2017). For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was .89, indicating good internal consistency reliability.

Drug Use

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-20; Skinner & Goldberg, 1986) assessed participants’ degree of drug use and potential drug abuse over the past year. The DAST-20 is a 20-item, self-reported measure that provides a total score used to calculate the severity of drug use. The DAST-20 includes 20 nominal items in which participants select Yes or No (with values of 1 and 0, respectively) to a series of questions. Sample questions include, “Can you get through the week without using drugs?” (reverse scored). Total scores were calculated by summing the participants’ item responses after reverse scoring items 4 and 5 with a range from 0 to 20. We used a cutoff score of 6 or higher to indicate problematic drug use (see Table 1). Scores on the DAST-20 have demonstrated good internal consistency reliability with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .74 to .95 (Yudko et al., 2007). In the current study, we identified a Cronbach’s alpha of .92 for DAST-20 scores, indicating good internal consistency reliability.

Data Analysis

To address the questions in this study, we facilitated a path analysis with the data to test the a priori model with a community sample acquired through MTurk. The recommended fit indexes (Kline, 2005) used in this study included the chi-square statistics (p-value, > .05 indicates fit), comparative fit index (CFI, ≥ .90 indicates fit), standardized root mean square residual (SRMSR, ≤ .08 indicates fit), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, ≤ .08 indicates fit). In addition, the Bollen-Stine bootstrapping procedure was used with 5,000 samples as an additional assessment of model fit. The path analysis was performed in AMOS (Version 24; Arbuckle, 2012) using a maximum likelihood estimation approach. The direct effects are displayed as standardized regression weights (β).

Results

Preliminary Analysis

We examined and screened the data prior to analysis. No outliers were identified, and the data met statistical assumptions associated with path analysis (e.g., multivariate normality, low multicollinearity, and linearity; Hair et al., 2006; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). The correlation coefficients between the variables in this path model (see Table 2) were lower than .8, meaning there was a low chance of collinearity problems. We identified no issues of multicollinearity, as the variance inflation factors for the constructs in the path model were lower than 10 (Hair et al., 2006; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Table 2 also includes the means and standard deviations for the variables in this model. Various guidelines were reviewed as a means for determining the appropriate sample size for this investigation. Jackson (2003) and Kline (2005) stated that a 20:1 ratio of sample size to parameters is preferable, and our current study exceeded this recommendation.

Table 2

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for the Variables in the Path Analysis

| Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| Self-Stigma of Mental Illness |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

| Self-Stigma of Help Seeking |

.54** |

– |

|

|

|

|

| Attitudes Toward Help Seeking |

-.28** |

-.62 |

– |

|

|

|

| Drug Use |

-.02 |

.11 |

-.16* |

– |

|

|

| Alcohol Use |

-.01 |

.12 |

-.14* |

.68** |

– |

|

| Age |

.08 |

-.01 |

.05 |

-.27 |

-.26** |

– |

| M(SD) |

3.23(.89) |

2.74(.81) |

1.71(.61) |

4.31(5.07) |

9.79(8.01) |

34.39(9.99) |

Note. Measures used in this study include the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (SSOMI; Tucker et al., 2013), the Self-Stigma of Help Seeking Scale (SSOHS; Vogel et al., 2006), Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help – Short Form (ATSPPH-SF; Fischer & Farina, 1995), the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993), and Drug Abuse Screening Test-20 (DAST-20; Skinner & Goldberg, 1986).

* = p < .01, ** = p < .001.

We examined the variables in this study (i.e., self-stigma of mental illness and help-seeking, attitudes toward help-seeking, and drug and alcohol use) to evaluate for potential control variables. Specifically, we conducted several correlations comparing the variables in this study with demographic characteristics. For dichotomous variables, we utilized point-biserial correlations. These analyses indicated that age had significant relationships with both drug and alcohol use; thus, we included age in the path analysis as a control variable.

Model Specifications

The a priori hypothesized model tested in this path analysis included a total of six observed variables that were placed in a causal directional structure that we developed from our understanding of the literature. The exogenous variables included self-stigma of mental illness (as measured by the SSOMI; Tucker et al., 2013) and self-stigma of help seeking (as measured by the SSOHS; Vogel et al., 2006). In addition, attitude toward help-seeking (as measured by the ATSPPH-SF; Fischer & Farina, 1995) was both an exogenous and endogenous variable. Lastly, alcohol use (as measured by the AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993) and drug use (as measured by the DAST-20; Skinner & Goldberg, 1986) and were endogenous. We correlated self-stigma of mental illness and self-stigma of help seeking along with the error terms for alcohol and drug use. In the model, we examined the direct effect of self-stigma of mental illness and self-stigma of help seeking on attitudes toward help-seeking. Furthermore, we examined the direct effect of attitudes toward help seeking on drug and alcohol use. We included age in this model as a control variable as we examined its direct effect on attitudes toward help seeking, drug use, and alcohol use. A total of 5,000 bias-corrected bootstrapped samples were created (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007) to examine the indirect effect of self-stigma of mental illness and self-stigma of help seeking on drug use and alcohol use, with attitudes toward help seeking as the mediator.

Path Analysis

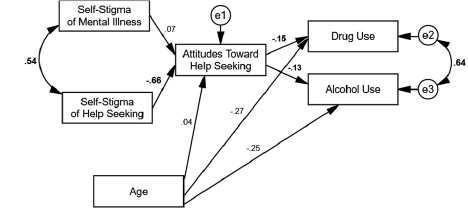

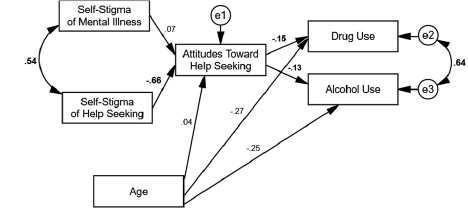

The model (see Figure 1) produced excellent fit: χ2(6, N = 406) = 6.85, p = .34; χ2/df = 1.14; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .02; SRMSR = .01, Bollen-Stine bootstrap, p = .21. Self-stigma of mental illness did not have a direct effect on attitudes toward help seeking (β = .07, SE = .03, p > .05) whereas self-stigma of help seeking did have a negative direct effect on attitudes toward help seeking (β = -.66, SE = .04, p < .001). Attitudes toward help seeking had a negative direct effect on both drug use (β = -.15, SE = .02, p < .01)

and alcohol use (β = -.13, SE = .06, p < .01). The control variable of age had a negative direct effect on drug use (β = -.27, SE = .00, p < .001) and alcohol use (β = -.25, SE = .00, p < .001) but not attitudes toward help seeking (β = .04, SE = .00, p > .05). The residuals of self-stigma of mental illness and self-stigma of help seeking had a positive correlation (r = .54, SE = .04, p < .001) along with drug and alcohol use (r = .64, SE = .01, p < .001). These findings indicated that higher self-stigma of help seeking was associated with a more negative attitude toward help seeking, and more positive attitudes toward help seeking were associated with lower drug and alcohol use. It is also important to note that the effect sizes in the model ranged from small to large (Sink & Stroh, 2006).

Figure 1

Path Model With Age as a Control Variable

The mediated path analysis results indicated that self-stigma of mental illness did not have an indirect effect on drug use (β = -.01, SE = .05, p = .14, 95% BC [-.03, .00]) nor alcohol use (β = -.01, SE = .01, p = .14, 95% BC [.-03, .00]) through attitudes toward help seeking. The mediated path analysis results also indicated that self-stigma of help seeking had an indirect effect on drug use (β = .10, SE = .03, p < .001, 95% BC [.05, .15]) and alcohol use (β = .08, SE = .03, p < .001, 95% BC [.03, .14]) through attitudes toward help seeking.

Discussion

Research has indicated the importance of decreasing stigma surrounding substance use treatment in order to address the public health issue of so many individuals lacking treatment in the United States (Bose et al., 2016; Clement et al., 2015). Although the effects of self-stigma on help-seeking behaviors (Crowe et al., 2016; Mullen & Crowe, 2017), attitudes toward seeking psychological help (Cheng et al., 2018), and AOD use (Luoma et al., 2008) have been well documented, there remains a gap in the counseling literature explicating the relationship between the above constructs. In this study, the proposed theoretical causal model (see Figure 1) suggested that self-stigma of mental illness and self-stigma of help seeking would have a direct effect on attitudes toward help seeking and a positive indirect effect on drug and alcohol use mediated by attitudes toward help seeking; moreover, it suggested that attitudes toward help seeking would have a negative direct effect on AOD use.

By using the online platform MTurk for a community sample of 406 participants, the results from a path analysis indicated an excellent fit model with significant standardized regression coefficients that revealed a complex relationship between self-stigma of mental illness, self-stigma of help-seeking, attitudes toward psychological help seeking, AOD use, and age. Although the results of the present study did not support all three initial hypotheses, the findings did show a statistically significant indirect relationship among the six variables.

The first hypothesis was not supported by data because self-stigma of mental illness did not have a direct effect on attitudes toward help seeking or an indirect effect on AOD use. However, self-stigma of mental illness did correlate with self-stigma of help seeking, which included a large effect size that indicated a strong relationship between these variables. The lack of direct effect between self-stigma of mental illness and attitudes toward help seeking may have resulted from a moderating influence caused by the direct effect of self-stigma of help seeking on attitudes toward help seeking. Based on these findings, we concluded that self-stigma of help seeking is a stronger predictor of attitudes toward help seeking when paired with self-stigma of mental illness. However, more research is needed to replicate these findings, and specifically the potential moderating effect of self-stigma of help seeking on self-stigma of mental illness.

In contrast, the results from the path analysis provided evidence for our second hypothesis. Specifically, participants who reported high levels of self-stigma of help seeking had less positive attitudes toward seeking psychological help as well as higher alcohol use or drug use. This finding is consistent with findings from prior research that revealed participants who reported high levels of stigma had decreased adaptive coping skills such as help-seeking behaviors (Crowe et al., 2016) and increased maladaptive coping skills such as drug use (Etesam et al., 2014). It is possible that participants turned to drinking or drug use as a method of coping rather than seeking formal support. However, we cannot determine if that is the case from the current study. The direct relationship of an individual’s reported stigma of help seeking with less positive attitudes toward seeking psychological help also confirms previous theoretical descriptions of the relationship between self-stigma of help seeking and attitudes toward help seeking (Tucker et al., 2013; Vogel et al., 2007; Wade et al., 2011).

Lastly, participants who reported more positive attitudes toward help seeking had significantly lower AOD use, which provided support for our third hypothesis. These findings suggest that regardless of age, participants who had a positive attitude toward seeking help reported significantly lower AOD use. In addition to the unique findings uncovered through mediation analysis, this study further supports the argument that self-stigma of mental illness and self-stigma of help seeking are two theoretically and empirically distinct constructs (Tucker et al., 2013). Moreover, the significantly direct effect of an individual’s self-stigma of help seeking on attitudes toward seeking psychological help confirms the need that treatments must address more than one component of self-stigma and that addressing self-stigma of mental illness alone may not improve attitudes toward help seeking (Tucker et al., 2013; Wade et al., 2011). The findings may also suggest the benefit of increased advocacy and health promotion as it relates to help-seeking and combatting stigma.

Implications for Counselor Education and Counselors

Given that we found an individual’s attitudes toward seeking psychological help negatively relate to AOD use, it behooves counselors to address factors that impede help seeking. Equally important, the present findings and prior evidence reporting public stigma as a predictor of the development of self-stigma over time (Vogel et al., 2013) have important implications for the advocacy work needed by counselors and counselor educators on both an individual level and a systemic level to fully address the development of self-stigma of help seeking that subsequently affects an individual’s attitudes toward seeking psychological help. On an individual level, counselors can implement and advocate for interventions that increase an individual’s positive attitudes toward seeking help that may lower the individual’s substance use through mental health literacy (Cheng et al., 2018). Moreover, they can challenge thoughts of seeking help as weakness (Wade et al., 2011), normalize seeking psychological help, and discuss the benefits of therapy to address the development and effects of self-stigma of help seeking for individuals with substance use issues. Counselors can also empower clients by cultivating awareness and reflection of internalized negative beliefs developed from experiences of discrimination and prejudice that contribute to the self-stigma of help seeking. Moreover, efforts to deliver healthier messages about help seeking for mental health concerns from the media or faith-based organizations can assist with decreasing self-stigma that still exists.

In adherence to advocacy competency standards set forth by the American Counseling Association (Lewis et al., 2003), counselors should also consider using their position of power to address, on a systemic level, the enacted and perceived stigma experienced by individuals with substance use issues as well as the detrimental impact on attitudes toward seeking psychological help. For example, counselors can disseminate information that dispels myths surrounding help seeking and substance use to the public or create multimedia materials such as public service announcements that explain the impact of stigma on those with SUDs in the United States, making sure to include affirmative language about seeking psychological help and individuals reporting AOD use (Corrigan, 2011). Counselors also can lobby to make changes to workplace policies and practices to increase mental health support for those with AOD concerns, as supportive policies and practices can also decrease the stigmas associated with AOD concerns.

Additionally, counselors and counselor educators can improve attitudes toward help seeking as well as decrease the stigma of individuals with substance use issues by intentionally using person-first language on administered surveys, academic scholarship, and provided resources to clients and the community (Tucker et al., 2013). For example, Granello and Gibbs (2016) found that participants reported higher tolerance and less stigmatized attitudes when the language on surveys was changed from “mentally ill” to “people with mental illness.” In the current study, we used person-first language in order to model correct terminology and would suggest that future researchers do the same. By disseminating knowledge and material to the public in less stigmatizing language, counselors and counselor educators can counter negative group stereotypes that lead to self-stigma of individuals with substance use issues (Al-Khouja & Corrigan, 2017; Rao et al., 2009).

For counselor educators and supervisors training beginning counselors, this study suggests the importance of increased awareness of their own attitudes toward individuals reporting AOD use because of the effects of internalized public stigma, which increases maladaptive coping skills such as treatment avoidance (Crowe et al., 2016) and AOD use (Etesam et al., 2014). To illustrate, counselor educators and supervisors may ask beginning counselors to reflect on their personal beliefs regarding seeking psychological help and individuals with substance use issues, as well as how these beliefs may have been learned based on public perceptions or knowledge of information regarding substance use. Classroom strategies that encourage reflection and increase an ethic of care may address previous findings of implicit bias, internalized negative public attitudes, or stigmatizing behaviors by health professionals that lower positive attitudes toward psychological help seeking for individuals with substance use issues (Ford, 2011). Lastly, counselor educators can further promote beginning counselors’ advocacy competencies through creative and engaging assignments that challenge students to develop ways of encouraging help seeking in the general public and dispel public myths about substance use or the stigma of seeking psychological help—for instance, the creation of fact and resource brochures distributed within the community.

This study also further supported the use of MTurk for reliable and valid data in an accessible community sample (Kim & Hodgins, 2017). The anonymity, convenience, and incentive offered to participants via MTurk while reporting behaviors stigmatized by the general public may contribute to the gathering of reliable and valid data (Kim & Hodgins, 2017). Additionally, this study supports MTurk as a tool to identify clinical populations with alcohol use problems (Al-Khouja & Corrigan, 2017). The use of MTurk as a sampling method is currently limited in counselor education literature and may lead to more representative samples that resemble targeted community populations beyond the commonly accessed university samples by researchers.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although the study used a community sample, the sample included only individuals accessible through MTurk, and research on the representativeness of samples drawn from MTurk is limited (Al-Khouja & Corrigan, 2017; Kim & Hodgins, 2017). The sample employed through MTurk was gathered widely from the community and previous studies have shown evidence of validity and reliability of MTurk as a recruiting tool with substance-using populations (Kim & Hodgins, 2017). However, because MTurk uses an online platform, it is subject to the same classic limitations associated with online data collection, such as representativeness and technical difficulties (Granello & Wheaton, 2004). Therefore, the current sample showed diversity among participants, but researchers could not confirm whether MTurk samples were representative of the populations from which they were drawn. Specifically, the sample consisted primarily of White and Asian participants, thereby limiting generalizability to people of other race/ethnicity classifications. Another limitation of this study is the absence of inattentive screening items. Additionally, this investigation used correlational data analysis methods to examine the proposed model; therefore, the findings could not indicate causality among the variables (Gall et al., 2007). Finally, although we wanted to know about stigma related to SUDs, we used scales that were designed to measure stigma in general. Although all instruments demonstrated strong psychometric properties in the current study, it is worth noting that stigma of SUDs may be different from stigma related to mental health concerns with no substance use.

Future Research

Considering the limitations, these findings provide significant implications for future research. We suggest replication of the present findings on future groups through the MTurk platform and other sampling methods (Al-Khouja & Corrigan, 2017). Additionally, researchers are encouraged to conduct experimental studies implementing potential substance use treatments that disrupt and measure the internalized negative group stereotypes that individuals with substance use issues may incorporate into their identity, substance usage, and treatment efficacy or length (Luoma et al., 2014; Tucker et al., 2013). Researchers have emphasized identity as a diagnostic moderator of self-stigma incurred by individuals with mental illness and substance use issues (Al-Khouja & Corrigan, 2017; Yanos et al., 2010), which suggests the importance of countering negative group stereotypes and public stigma for vulnerable groups such as individuals with substance use issues who report high levels of self-stigma. Further, counselor educators are encouraged to explore the relationship between identity, self-stigma of help seeking, and attitudes toward seeking psychological help with individuals reporting substance use issues as well. Lastly, counselor educators may examine the use of MTurk to gather a community sample, explore behaviors and attitudes considered socially unacceptable by the general public, and recruit individuals meeting the clinical criteria for substance use, who are often a hidden population because of enacted and perceived stigma.

Conclusion

The current study examined the complex and understudied relationship between AOD use, self-stigma of help seeking, self-stigma of mental illness, and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. The findings suggest the unique, indirect relationship between self-stigma of help seeking, a positive attitude toward seeking psychological help, and AOD use, regardless of participant age ranges. Previous conceptualization of the interdependence between self-stigma and group stereotypes (Al-Khouja & Corrigan, 2017) as well as the unique findings of the current study suggest that counselors and substance use interventions need to counter group stereotypes that individuals with substance use internalize, which decrease positive attitudes toward seeking psychological help and help-seeking behaviors for mental illness (Crowe et al., 2016; Tucker et al., 2013; Wade et al., 2011). By countering group stereotypes through methods targeting attitudes toward help seeking and the self-stigma of help seeking, counselors and counselor educators can potentially combat the negative attitudes toward seeking psychological help that become internalized treatment barriers for individuals with substance use issues (Luoma et al., 2008) and help lower AOD use.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Al-Khouja, M. A., & Corrigan, P. W. (2017). Self-stigma, identity, and co-occurring disorders. The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 54(1), 56–61.

Arbuckle, J. R. (2012). AMOS users guide version 24.0 [User manual]. IBM Corp.

Barry, C. L., McGinty, E. E., Pescosolido, B. A., & Goldman, H. H. (2014). Stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy: Public views about drug addiction and mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 65(10), 1269–1272. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400140

Birtel, M. D., Wood, L., & Kempa, N. J. (2017). Stigma and social support in substance abuse: Implications for mental health and well-being. Psychiatry Research, 252, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/jpsychres.2017.01.097

Bose, J., Hedden, S. L., Lipari, R. N., & Park-Lee, E. (2018). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 18-5068, NSUDH Series H-53). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.pdf

Bose, J., Hedden, S. L., Lipari, R. N., Park-Lee, E., Porter, J. D., & Pemberton, M. R. (2016). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 16-4984, NSDUH Series H-51). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015.pdf

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2015). Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018). 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2017-methodological-summary-and-definitions

Cheng, H.-L., Wang, C., McDermott, R. C., Kridel, M., & Rislin, J. L. (2018). Self-stigma, mental health literacy, and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12178

Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., Maggioni, F., Evans-Lacko, S., Bezborodovs, N., Morgan, C., Rüsch, N.,

Brown, J. S. L., & Thornicroft, G. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000129

Corrigan, P. W. (2011). Strategic stigma change (SSC): Five principles for social marketing campaigns to reduce stigma. Psychiatric Services, 62(8), 824–826. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.62.8.pss6208_0824

Crapanzano, K. A., Hammarlund, R., Ahmad, B., Hunsinger, N., & Kullar, R. (2019). The association between perceived stigma and substance use disorder treatment outcomes: A review. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 10, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S183252

Crowe, A., Averett, P., & Glass, J. S. (2016). Mental illness stigma, psychological resilience, and help seeking: What are the relationships? Mental Health & Prevention, 4(2), 63–68. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mhp.2015.12.001

da Silveira, P. S., Casela, A. L. M., Monteiro, É. P., Ferreira, G. C. L., de Freitas, J. V. T., Machado, N. M., Noto, A. R., & Ronzani, T. M. (2018). Psychosocial understanding of self-stigma among people who seek treatment for drug addiction. Stigma and Health, 3(1), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000069

Elhai, J. D., Schweinle, W., & Anderson, S. M. (2008). Reliability and validity of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form. Psychiatry Research, 159(3), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.020

Etesam, F., Assarian, F., Hosseini, H., & Ghoreishi, F. S. (2014). Stigma and its determinants among male drug dependents receiving methadone maintenance treatment. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 17(2), 108–114.

Fischer, E. H., & Farina, A. (1995). Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: A shortened form and considerations for research. Journal of College Student Development, 36(4), 368–373.

Follmer, D. J., Sperling, R. A., & Suen, H. K. (2017). The role of MTurk in education research: Advantages, issues, and future directions. Educational Researcher, 46(6), 329–334. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17725519

Ford, R. (2011). Interpersonal challenges as a constraint on care: The experience of nurses’ care of patients who use illicit drugs. Contemporary Nurse, 37(2), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2011.37.2.241

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2007). Education research: An introduction (8th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall.

Granello, D. H., & Gibbs, T. A. (2016). The power of language and labels: “The mentally ill” versus “people with mental illnesses.” Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12059

Granello, D. H., & Wheaton, J. E. (2004). Online data collection: Strategies for research. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82(4), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00325.x

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson.

Jackson, D. L. (2003). Revisiting sample size and number of parameter estimates: Some support for the N:q hypothesis. Structural Equation Modeling, 10(1), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1001_6

Karaffa, K. M., & Koch, J. M. (2016). Stigma, pluralistic ignorance, and attitudes toward seeking mental health services among police officers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(6), 759–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854815613103

Kim, H. S., & Hodgins, D. C. (2017). Reliability and validity of data obtained from alcohol, cannabis, and gambling populations on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000219

Kline, R. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. (2nd ed.). Guilford.

Lewis, J. A., Arnold, M. S., House, R., & Toporek, R. L. (2003). ACA advocacy competencies. https://www.counseling.org/knowledge-center/competencies

Livingston, J. D., Milne, T., Fang, M. L., & Amari, E. (2012). The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: A systematic review. Addiction, 107(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03601.x

Luoma, J. B., Kohlenberg, B. S., Hayes, S. C., Bunting, K., & Rye, A. K. (2008). Reducing self-stigma in substance abuse through acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, manual development, and pilot outcomes. Addiction Research & Theory, 16(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350701850295

Luoma, J. B., Kulesza, M., Hayes, S. C., Kohlenberg, B., & Larimer, M. (2014). Stigma predicts residential treatment length for substance use disorder. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(3), 206–212. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2014.901337

Masson, C. L., Shopshire, M. S., Sen, S., Hoffman, K. A., Hengl, N. S., Bartolome, J., McCarty, D., Sorensen, J. L.,

& Iguchi, M. Y. (2013). Possible barriers to enrollment in substance abuse treatment among a diverse sample of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: Opinions of treatment clients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(3), 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.08.005

Mora-Ríos, J., Ortega-Ortega, M., & Medina-Mora, M. E. (2017). Addiction-related stigma and discrimination: A qualitative study in treatment centers in Mexico City. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(5), 594–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2016.1245744

Mullen, P. R., & Crowe, A. (2017). Self-stigma of mental illness and help seeking among school counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 95(4), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12155

Rao, H., Mahadevappa, H., Pillay, P., Sessay, M., Abraham, A., & Luty, J. (2009). A study of stigmatized attitudes towards people with mental health problems among health professionals. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(3), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01369.x

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

Schomerus, G., Corrigan, P. W., Klauer, T., Kuwert, P., Freyberger, H. J., & Lucht, M. (2011). Self-stigma in alcohol dependence: Consequences for drinking-refusal self-efficacy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 114(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.013

Sink, C. A., & Stroh, H. R. (2006). Practical significance: The use of effect sizes in school counseling research.

Professional School Counseling, 9(4), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0500900406

Skinner, H. A., & Goldberg, A. E. (1986). Evidence for a drug dependence syndrome among narcotic users. British Journal of Addiction, 81(4), 479–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00359.x

Smith, L. R., Earnshaw, V. A., Copenhaver, M. M., & Cunningham, C. O. (2016). Substance use stigma: Reliability and validity of a theory-based scale for substance-using populations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.019

Stringer, K. L., & Baker, E. H. (2018). Stigma as a barrier to substance abuse treatment among those with unmet need: An analysis of parenthood and marital status. Journal of Family Issues, 39(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513×15581659

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Tucker, J. R., Hammer, J. H., Vogel, D. L., Bitman, R. L., Wade, N. G., & Maier, E. J. (2013). Disentangling self-stigma: Are mental illness and help-seeking self-stigmas different? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 520–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033555

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. (2018). Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s spotlight on opioids. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/Spotlight-on-Opioids_09192018.pdf

Vogel, D. L., Bitman, R. L., Hammer, J. H., & Wade, N. G. (2013). Is stigma internalized? The longitudinal impact of public stigma on self-stigma. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(2), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031889

Vogel, D. L., & Wade, N. G. (2009). Stigma and help-seeking. The Psychologist, 22, 20–23. https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-22/edition-1/stigma-and-help-seeking

Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Haake, S. (2006). Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.325

Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Hackler, A. H. (2007). Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.40

Wade, N. G., Post, B. C., Cornish, M. A., Vogel, D. L., & Tucker, J. R.. (2011). Predictors of the change in self-stigma following a single session of group counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(2), 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022630

Winstanley, E. L., Clark, A., Feinberg, J., & Wilder, C. M. (2016). Barriers to implementation of opioid overdose prevention programs in Ohio. Substance Abuse, 37(1), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2015.1132294

Yanos, P. T., Roe, D., & Lysaker, P. H. (2010). The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 13(2), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487761003756860

Yudko, E., Lozhkina, O., & Fouts, A. (2007). A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32(2), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002

Daniel Gutierrez, PhD, NCC, LPC, CSAC, is an assistant professor at the College of William & Mary. Allison Crowe, PhD, NCC, LPCS, is an associate professor at East Carolina University. Patrick R. Mullen, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at the College of William & Mary. Laura Pignato is a doctoral student at the College of William & Mary. Shuhui Fan, NCC, is a doctoral student at the College of William & Mary. Correspondence may be addressed to William & Mary, Daniel Gutierrez, School of Education, P.O. Box 8795, Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795, dgutierrez@wm.edu.

Apr 29, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 2

Heather J. Fye, Ryan M. Cook, Eric R. Baltrinic, Andrea Baylin

Burnout is a statistically significant phenomenon for school counselors, correlated with various individual and organizational factors, which have been studied independently. Therefore, we investigated both individual and organizational factors of burnout conceptualized as a multidimensional phenomenon with 227 school counselors. Multidimensional burnout was measured by the five subscales of the Counselor Burnout Inventory, which included Exhaustion, Incompetence, Negative Work Environment, Devaluing Clients, and Deterioration in Personal Life. Using hierarchal regression analyses, we found individual and organizational factors accounted for 66.6% of the variance explained in Negative Work Environment, 38.3% of the variance explained in Deterioration in Personal Life, 36.7% of the variance explained in Incompetence, 35.1% of the variance explained in Exhaustion, and 14.0% of the variance explained in Devaluing Clients. We discuss implications of the findings for school counselors and supervisors. Identifying the multidimensions of burnout and its correlates, addressing self-care and professional vitality goals, communicating defined school counselor roles, providing mentoring opportunities, and increasing advocacy skills may help alleviate burnout.

Keywords: stress, burnout, job satisfaction, coping processes, school counselors

In addition to providing counseling services, school counselors are charged with performing multiple non-counseling duties in their schools (Bardhoshi et al., 2014). These multiple and competing demands place them at risk for experiencing burnout (Mullen et al., 2018). Accordingly, it is important to identify factors that contribute to burnout to promote school counselors’ psychological well-being (Kim & Lambie, 2018), which in turn reinforces school counselors’ ability to support students’ well-being (Holman et al., 2019).

Burnout is a workplace-specific complex construct characterized by feelings of exhaustion, cynicism, and detachment, and a lack of accomplishment and effectiveness (Maslach & Leiter, 2017). Others have conceptualized counselor burnout as a multidimensional construct, featuring the interaction between the individual and work environment (Lee et al., 2007). Given the complex, multidimensional, and interactional nature of burnout, the Counselor Burnout Inventory (CBI) was developed to measure the construct with five subscales: Exhaustion, Incompetence, Negative Work Environment, Devaluing Clients, and Deterioration in Personal Life (Lee et al., 2007). Specific to school counselors, Kim and Lambie (2018) suggested that burnout occurs to varying degrees across individual and organizational factors. Individual factors include perceived stress (Fye et al., 2018; Mullen et al., 2018; Mullen & Gutierrez, 2016; Wilkerson, 2009; Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006) and coping processes (Fye et al., 2018; Wilkerson, 2009; Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006). Organizational factors include perceived job satisfaction (Baggerly & Osborn, 2006; Bryant & Constantine, 2006; Mullen et al., 2018) and role stress (Bardhoshi et al., 2014; Coll & Freeman, 1997; Culbreth et al., 2005).

Researchers of school counselor burnout have studied individual and organizational factors of this phenomenon using a unidimensional structure such as the CBI scale score (Mullen et al., 2018). Other researchers (e.g., Bardhoshi et al., 2014; Moyer, 2011) studied organizational factors, including caseload and administrative (non-counseling) duties, within the multidimensional structure of the CBI (Lee et al., 2007). However, researchers have not yet comprehensively studied these known individual and organizational factors within the context of a multidimensional structure of school counselor burnout. For example, Mullen et al. (2018) investigated the relationships between perceived stress, perceived job satisfaction, and school counselor burnout. However, they did not examine organizational factors such as role stress (e.g., clerical duties), which are also significant to understanding school counselor burnout (Bardhoshi et al., 2014). Thus, we sought to extend the research findings by examining several individual factors (i.e., perceived stress, coping processes) and organizational factors (i.e., perceived job satisfaction, role stress) within a multidimensional structure of school counselor burnout.

Individual Factors

Individual factors related to school counselor burnout include psychological constructs and demographic factors (Kim & Lambie, 2018). The two psychological constructs included in the current study were perceived stress (Mullen et al., 2018) and coping processes (Fye et al., 2018). Researchers have previously found contradictory results for the relationship between years of experience and school counselor burnout (Mullen et al., 2018; Wilkerson, 2009). Therefore, the factor of years of experience was included in the current study.

Perceived Stress

Perceived stress is theorized as an individual’s ability to appraise a threatening or challenging event in relation to the availability of coping resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). To that end, a transactional model of stress and coping suggests that stress is a response that occurs when perceived demands exceed one’s coping abilities. For school counselors, perceived stress may occur regularly because of various factors, including non-counseling duties, excessive paperwork and administrative duties, and work overload (Bardhoshi et al., 2014).

Researchers have described a positive relationship between stress and burnout among school counselors (Mullen et al., 2018; Mullen & Gutierrez, 2016). Specifically, higher levels of stress and burnout were related to lower levels of job satisfaction and delivery of direct student services (Mullen et al., 2018; Mullen & Gutierrez, 2016). Others have reported increased emotional responses alongside increased burnout (Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006). For example, school counselors who attempted to deal with stress emotionally may be at greater risk for developing symptoms of burnout including emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lower levels of personal accomplishment (Wilkerson, 2009). Additionally, school counselors reported higher levels of emotional exhaustion than other mental health professionals, which can negatively impact their delivery of school counseling services (Bardhoshi et al., 2014). The correlation between stress and burnout further highlights the importance of assessing the components of stress and the ways school counselors are coping with these factors.

Coping Processes

Coping processes are defined as the cognitive and behavioral processes used to manage stressful situations (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). There are several coping processes, including problem-focused coping, active-emotional coping, and avoidant-emotional coping (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985). For example, problem-focused coping is defined as an action-oriented approach to stress in which one believes the stressors are controllable by personal action (Lazarus, 1993). Active-emotional coping is an adaptive response to unmanageable stressors and avoidant-emotional coping is described as a maladaptive response to those stressors (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985).

Among school counselors, Fye et al. (2018) studied the relationship between perfectionism, burnout, stress, and coping. These authors found that maladaptive perfectionists engaged more frequently in avoidant-emotional coping and relatedly experienced higher levels of burnout. Moreover, adaptive perfectionists experienced less stress and burnout and reported higher levels of problem-focused coping. Overall, for school counseling professionals, emotional-focused coping is positively related to burnout (Wilkerson, 2009). Given these findings, it is imperative for school counselors to be aware of their coping processes, including the degree to which they are affecting their levels of stress and burnout (Wilkerson, 2009).

Organizational Factors

In addition to individual factors such as stress and coping (Fye et al., 2018; Mullen et al., 2018; Wilkerson, 2009), school counseling researchers noted several organizational factors as contributing to school counselor burnout (Holman et al., 2019; Kim & Lambie, 2018). Accordingly, researchers in the current study examined organizational factors, including perceived job satisfaction and role stress (i.e., role ambiguity, role incongruity, and role conflict; Culbreth et al., 2005). Additionally, because previous researchers found a relationship between the organizational factor of school district (e.g., urban setting) and burnout (Butler & Constantine, 2005), this variable was included in the present study.

Perceived Job Satisfaction

Perceived job satisfaction refers to the degree of affective or attitudinal reactions one experiences relative to their job (Spector, 1985). Understanding the extent of school counselors’ perceived job satisfaction may be one way to buffer the effects of stress and burnout. This is because, according to Bryant and Constantine (2006), job satisfaction predicted life satisfaction for school counselors.

Perceived job satisfaction and its relationship with stress and burnout have received increased attention in the school counseling literature (Mullen et al., 2018). Among the contributing factors, higher levels of role balance and increased perceived job satisfaction resulted in greater overall life satisfaction (Bryant & Constantine, 2006). Higher perceived job satisfaction has been aligned with school counselors engaging in appropriate roles. For example, Baggerly and Osborn (2006) found that school counselors who frequently performed roles aligned with comprehensive school counseling programs were more satisfied and more committed to their careers. Similarly, higher perceived job satisfaction was directly related to the school counselor’s ability to provide direct student services within their schools (Kolodinsky et al., 2009). Conversely, school counselors who did not intend to return to their jobs the following year reported higher levels of demand and stress because of non-counseling duties, such as excessive paperwork and administrative disruptions (McCarthy et al., 2010). As a result, those who are not satisfied are at risk for disengagement (Mullen et al., 2018), while school counselors who are satisfied with their jobs may have increased student connections (Kolodinsky et al., 2009).

Role Stress

Role stress refers to the levels of role incongruity, role conflict, and role ambiguity experienced by school counselors (Culbreth et al., 2005; Freeman & Coll, 1997). Role incongruity may occur when there are structural conflicts, including inadequate resources for school counselors and engagement in ineffective tasks (Freeman & Coll, 1997). Several authors noted that inappropriate or non-counseling duties contributed to burnout, including excessive paperwork, administrative duties, and testing coordinator roles (Bardhoshi et al., 2014; Moyer, 2011, Wilkerson, 2009). Moyer (2011) found that school counselors who engaged in increased non-counseling duties also had increased feelings of exhaustion and incompetence, had decreased feelings toward work environment, and were less likely to show empathy toward students. Furthermore, school counselors who were assigned inappropriate roles reported higher levels of frustration and resentment toward the school system. Overall, authors emphasized the importance of educating administrators on the appropriate and inappropriate roles for school counselors to decrease burnout (Bardhoshi et al, 2014; Cervoni & DeLucia-Waack, 2011; Moyer, 2011).

Role conflict occurs when school counselors experience multiple external demands from different stakeholders (Holman et al., 2019). Role conflict examples for school counselors include: (a) whether school counselors should focus on the education goals or mental health needs of students first (Paisley & McMahon, 2001) and (b) whether a school counselor should engage in an actual role given by an administration or supervisor (e.g., testing coordinator) or preferred role (e.g., classroom guidance activity; Wilkerson, 2009). As such, school counselors can feel overwhelmed and often engage in inappropriate duties, according to the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) National Model (2019). In turn, school counselors experience stress and burnout (Mullen et al., 2018).

Role ambiguity is the discrepancy between actual and preferred counseling duties (Scarborough & Culbreth, 2008). Role ambiguity has been linked to burnout because of school counselors’ stress from lacking an understanding of their professional roles and being misinformed about the realities of the job (Culbreth et al., 2005). For example, school counselors face challenges of navigating mixed messages about role expectations across stakeholders (Coll & Freeman, 1997). This confusion may lead to school counselors experiencing role ambiguity (Scarborough & Culbreth, 2008). When school counselors interact with stakeholders who have conflicting ideas about their roles, it creates stress. It is especially difficult for school counselors when stakeholders’ conceptualization of their roles clashes with what school counselors learned during graduate training (Culbreth et al., 2005). When school counselors are assigned duties that conflict with their own understandings of their roles, they are not able to operate in alignment with their professional mandates (Holman et al., 2019). Overall, school counselors experiencing role ambiguity also report higher levels of stress, both of which have been linked to burnout (Kim & Lambie, 2018).

Purpose of the Present Study

Despite prevalence in the school counseling burnout literature regarding individual and organizational factors of burnout, we were unable to locate a study that holistically researched these variables. To align our findings with a theoretical understanding of school counselor burnout, we examined these phenomena as a multidimensional construct. Additionally, we controlled for years of experience (Mullen et al., 2018; Wilkerson, 2009; Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006) and school district (Butler & Constantine, 2005). Therefore, we answered the research question: What is the relationship between individual (i.e., perceived job stress, problem-focused coping, avoidant-emotional coping, and active-emotional coping) and organizational (i.e., perceived job satisfaction, role incongruity, role conflict, and role ambiguity) factors after controlling for years of experience and school district, with the subscales of school counselor burnout: (1) Exhaustion, (2) Incompetence, (3) Negative Work Environment, (4) Devaluing Clients, and (5) Deterioration in Personal Life?

Method

Sample

A total of 227 school counselors participated in the study. Ages ranged from 26 to 69 (M = 46.21; SD = 10.26; four declined to answer). The sex of participants included females (n = 166, 73.1%) and males (n = 61, 26.9%). The race and ethnicity of participants included White (n = 185, 81.5%), African American/Black (n = 20, 8.8%), Hispanic (n = 7, 3.1%), Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 3, 1.3%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (n = 1, 0.4%), and Biracial/Multiracial (n = 9, 4.0%), and two participants (0.9%) declined to answer. Participants held a master’s degree in school counseling (n = 175, 77.1%), a PhD or EdD (n = 33, 14.5%), or a master’s degree in another counseling or mental health specialty area (n = 19, 8.4%). The years of experience ranged from 2 to 41 years (M = 13.68, SD = 7.49). Participants reported working in suburban (n = 97, 42.7%), rural (n = 76, 33.5%), and urban (n = 54, 23.8%) settings. Regarding level of practice, participants worked in an elementary school (i.e., grades K–6; n = 80, 35.2%), middle school (i.e., grades 7–8; n = 14, 6.2%), high school (i.e., grades 9–12; n = 59, 26.0%), or multiple grade levels (e.g., K–8, K–12, etc.; n = 74, 32.6%). A power analysis was completed in G*Power 3.1 before beginning the study (Faul et al., 2009). The necessary sample size was determined to be at least 200, with a power of .80, assuming a moderate effect size of .15 in the multiple regression analyses, and with an error probability or alpha of .05 (J. Cohen, 1992).

Procedures

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to beginning the study. The first author sent recruitment emails to 4,000 school counselors who were professional members of the ASCA online membership directory. Specifically, approximately 20% of school counselors in each of the 50 states and District of Columbia were chosen from the membership directory to receive the recruitment emails. The emails included a brief introduction to the study and an anonymous link that took potential participants to the online survey portal in Qualtrics. Potential participants first reviewed the informed consent. Once they consented to the survey, participants completed the demographics questionnaire and instruments. A convenience sample was obtained based upon voluntary responses to the survey (Dimitrov, 2009).

Instruments

The first author constructed a brief demographics survey to gather information about the participants (e.g., age, sex, race and ethnicity, degree, and years of experience) and their work environment (e.g., school district, grade level). The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; S. Cohen et al., 1983) and Brief COPE (Carver, 1997) were used to measure individual factors. The Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS; Spector, 1985) and Role Questionnaire (RQ; Rizzo et al., 1970) were used to measure organizational factors. The CBI (Lee et al., 2007) was used to measure the dimensions of school counselor burnout.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

The PSS (S. Cohen et al., 1983) is a 14-item inventory designed to measure an individual’s perceived stress within the past month. In the present study, we used the PSS-4, which is a subset of items from the original 14-item scale. The PSS was normed on a large sample of individuals from across the United States (S. Cohen et al., 1983). Participants responded to a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Scores on the PSS-4 ranged from 0 to 20. An example question of the PSS-4 is: “In the past month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?” The PSS-4 was determined to be a suitable brief measure of stress perceptions, based upon adequate factor structure and predictive validity (S. Cohen & Williamson, 1988). Reliability has been upheld (e.g., S. Cohen & Williamson, 1988) with test-retest reliability at .85 after 2 days (S. Cohen et al., 1983). For the present study, the internal consistency reliability was calculated at α = .76. Correlations between the perceived stress total score and CBI subscales ranged from r = .19 to .55.

Brief COPE

The Brief COPE (Carver, 1997) is a 28-item inventory designed to measure coping responses or processes and includes 14 subscales. We followed previous researchers’ (e.g., Deatherage et al., 2014) grouping of the 14 subscales into three coping processes (i.e., problem-focused, active-emotional, and avoidant-emotional). Therefore, problem-focused coping contained the Active Coping, Planning, Instrumental Support, and Religion subscales. Active-emotional coping contained the Venting, Positive Reframing, Humor, Acceptance, and Emotional Support subscales. Avoidant-emotional coping contained the Self-Distraction, Denial, Behavioral Disengagement, and Self-Blame subscales. For the present study, the items pertaining to participants’ alcohol and illegal drug use as coping responses were omitted because of their sensitive nature. Therefore, 26 items were included in the present study. The inventory uses a 4-point Likert-type scale with scores ranging from 0 (I haven’t been doing this at all) to 3 (I’ve been doing this a lot). A sample item on the Brief COPE is “I’ve been turning to work or other activities to take my mind off things.” Construct validity has been upheld with the three coping processes (e.g., Deatherage et al., 2014). Test-retest reliability for the three subscale groups has been upheld over a year timespan (Cooper et al., 2008). For the present study, the internal consistency reliability was calculated for problem-focused coping at α = .84, avoidant-emotional coping at α = .70, and active-emotional coping at α = .81. Correlations between problem-focused coping and the CBI subscales ranged from r = .00 to .13, correlations between avoidant-emotional coping and CBI subscales ranged from r = .20 to .48, and correlations between active-emotional coping and CBI subscales ranged from r = .01 to .16.

Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS)

The JSS (Spector, 1985) is a 36-item inventory intended to measure an individual’s perceived job satisfaction or attitudes and aspects of the job. The JSS contains nine subscales: Pay, Promotion, Supervision, Fringe Benefits, Contingent Rewards, Operating Procedures, Coworkers, Nature of Work, and Communication. The inventory uses a 6-point Likert-type scale with scores ranging from 1 (disagree very much) to 6 (agree very much). Total scores range from 36 to 216 with the higher the score, the higher job satisfaction experienced. An example item on the JSS is “My job is enjoyable” (Spector, 1985, p. 711). The JSS was constructed for, and normed on, social service, education, and mental health professionals (Spector, 1985, 2011). Spector (1985) established convergent validity with the Job Descriptive Index (Smith et al., 1969), and produced scores ranging from .61 to .80. Strong reliability has been established for the JSS, including a Cronbach coefficient alpha of .91 for all factors combined, and at 18 months, the test-retest reliability score was .71 (Spector, 1985). For the present study, the internal consistency reliability was calculated for the total scores at α = .91. Correlations between the perceived job satisfaction total score and CBI subscales ranged from r = -.13 to -.75.

Role Questionnaire (RQ)